Abstract

The dynamics of pedestrian behavior within the built environment represent a multifaceted and evolving field of study, profoundly influenced by shifts in industrial and commercial paradigms. This systematic literature review (SLR) is motivated by the imperative to comprehensively investigate and assess the built environment through the lens of pedestrian modeling, employing advanced modeling tools. While previous scholarship has explored the interplay between the built environment and pedestrian dynamics (PD), there remains a conspicuous gap in research addressing the utilization of agent-based modeling (ABM) tools for a nuanced evaluation of PD within these contexts. The SLR highlights the essential and practical benefits of using ABM to study PD in built environments and combine related theories and practical projects. Beyond theoretical discussions, it emphasizes the real-world contributions of ABM in understanding and visualizing how people behave in urban spaces. It aims to provide deep insights for both researchers and urban planners. By thoroughly examining recent research, it not only explores the practical uses of ABM but also reveals its broad implications for various aspects of pedestrian behavior in built environments. As a result, this SLR becomes a key resource for understanding the crucial role of ABM in studying the complexities of our surroundings. The findings and discussion here highlight ABM’s vital role in bridging the gap between theory and practice, improving our understanding of pedestrian behavior in urban settings. Furthermore, this study outlines promising avenues for future research, thereby fostering continued exploration and innovation in the dynamic realm of pedestrian behavior within built environments.

1. Introduction

Understanding PD [1,2] in walking-predominant transportation cities is crucial for effective urban planning, infrastructure optimization, and urban design [3]. The movements and interactions of pedestrians significantly influence the functionality and safety of urban spaces. Traditional modeling approaches, such as macroscopic and microscopic models, have provided valuable insights into pedestrian behavior. However, these methods often fall short in capturing the complexity and variability of real-world pedestrian interactions.

ABM emerges as a powerful computational tool to address these limitations as a key computer-based simulation [3]. ABM simulates the actions and interactions of autonomous agents, offering a natural and adaptable approach to model PD. By mimicking individual behaviors and their responses to environmental cues, ABM provides a nuanced and detailed understanding of pedestrian movements in urban settings as a developed interface [4].

PD encompasses the study of how individuals navigate through urban spaces, responding to environmental cues, social interactions, and personal goals. These dynamics are profoundly influenced by shifts in industrial and commercial paradigms, leading to changes in urban structure, transportation systems, and land use [5]. As cities continue to grow and evolve, understanding pedestrian behavior becomes pivotal in promoting sustainable urban planning paradigms, optimizing infrastructural elements, and resolving intricate problem scenarios.

ABM is becoming well known and used in many fields because it mimics the behavior of a complex system where agents interact with each other and their surroundings using straightforward local rules [6]. The effectiveness of this technique in forecasting pedestrian movement in urban areas, the spread of infectious diseases, forecasting traffic movement, and the behavior of economic systems has increased attention paid to the effectiveness of the technology. Four key points that were summarized by Ali Bazghandi [3] focus on the superiority of ABM compared to other modeling techniques: (i) it captures emergent events; (ii) it gives a natural description of a system; (iii) it is adaptable; and (iv) it is time- and cost-efficient.

In this context, ABM has emerged as a potent computational paradigm for simulating PD within the built environment [7]. ABM stands out as a modeling approach capable of capturing emergent phenomena, offering naturalistic depictions of intricate systems and exhibiting temporal and resource efficiency [7]. The flexibility of ABM to handle diverse tasks, its bottom-up approach, and its ability to use random elements make it a great tool for improving models of pedestrian behavior. However, using ABM to study pedestrian dynamics has many challenges. One major issue is the need for well-defined models, as ABM’s success depends heavily on how well the model is designed. Also, performance can be a problem when dealing with a large number of agents.

This area of research has employed various modeling methods to understand and simulate how people move in urban settings. These methods can generally be divided into three categories: macroscopic, microscopic, and mesoscopic models [8].

Macroscopic Models: These models offer a broad view of pedestrian flows, treating crowds like a continuous fluid. They are useful for understanding overall movement patterns and flow characteristics in detail, but neglect individual movements [9]. The Lighthill–Whitham–Richards (LWR) model falls in this category.

Microscopic Models: These models focus on individual pedestrian behaviors and interactions. They model each pedestrian as an individual entity, allowing for a detailed analysis of interactions and decision-making processes. The social force model and CA are examples that have been widely used in PD research [10].

Mesoscopic Models: These models bridge the gap between macroscopic and microscopic approaches by incorporating elements of both. They consider group-level behaviors while still accounting for some individual interactions. They are useful when computational efficiency is crucial and detailed individual behaviors are less critical [11].

Comparison with ABM: ABM stands out from traditional modeling approaches by simulating the actions and interactions of autonomous agents. This method provides a more nuanced and adaptable approach to modeling pedestrian dynamics, capturing emergent behaviors resulting from individual interactions. ABM’s flexibility makes it especially suitable for complex urban environments where pedestrian behaviors are influenced by various factors [12].

The stages of development of ABM in PD are as follows.

- Early Development: The initial ABM focused on modeling simple behaviors and interactions of agents. These models demonstrated ABM’s potential to capture complex dynamics that were challenging to model using traditional methods [13].

- Advancements in Computational Power: More sophisticated ABM models were created when computational power improved. These models included higher levels of detail and more complex interaction rules, leading to more accurate simulations of PD in urban settings [14].

- Integration with Urban Planning: Recently, ABM has been integrated with urban planning tools. This integration provides urban design with more efficient and safer urban spaces [15].

While traditional models have provided valuable insights into pedestrian dynamics, ABM excels by capturing individual interactions’ complexity and variability. This review highlights ABM’s practical applications and limitations, offering a comprehensive understanding of its role in urban planning and design. The evolution from cellular automata CA to ABM marks a significant milestone, enabling the introduction of diverse agents and the exploration of nonlinear dynamics, allowing researchers to model pedestrians as intelligent, autonomous agents interacting with their environment and each other [16].

In the macroscopic approach, every individual and their interactions are modeled. In this approach, the averages can be used without losing information, as all possible sources of heterogeneity can be incorporated into the studies. Contrarily, the microscopic approach does not explicitly mention any micro-level property or system. The underlying assumption in these models is that aggregation of results can be used without losing any information. These models are applied successfully in the prediction of certain traffic situations, while the mesoscopic approach tries to make the most of the computational power by incorporating as many individuals as possible without deteriorating the quality of results. Although each individual cannot be tracked down, the models allow individual properties [3,4].

In the literature, John von Neumann and Stanislaw Ulam began exploring microsimulation using CA at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico [3] (Cohen, 2018) [17]. They reproduced patterns and behaviors with significant accuracy using simple rules. The next step in the simulations was the development of ABM, which allowed the introduction of multi-heterogeneous agents. Nonlinear dynamics were approached from a different angle by studying the local interactions between agents. Each individual in the pedestrian stream is modeled as an intelligent and autonomous agent. Pedestrians (agents) move and interact with other agents independently through a set of decision rules.

Recently, several studies [17,18,19] have supported ABM as an effective method for simulating pedestrian systems via computer. ABM, a modeling technique gaining popularity across various fields such as economics, biology, ecology, and social science, involves portraying the entities of study as agents within a specific environment. These agents engage with one another and with their surrounding environment according to a series of established decision-making rules.

Despite the growing use of ABM in various fields, there is a notable research gap in comprehensively understanding its practical applications and limitations specifically in pedestrian dynamics. This review seeks to bridge this gap by synthesizing existing studies to provide a clearer picture of how ABM can be effectively utilized in urban planning contexts. The novelty of this study lies in its focused examination of ABM within the built environment, which has not been extensively covered in previous literature.

This systematic literature review aims to be a valuable resource by highlighting the benefits of ABM in studying pedestrian dynamics within built environments. By combining theoretical foundations with practical insights from significant projects, the review bridges the gap between theory and practice. Pedestrian behavior in urban settings is a complex field influenced by industrial and commercial changes. ABM can provide crucial insights into this domain. This review evaluates ABM’s effectiveness, addressing its practical applications and limitations. By synthesizing theoretical and practical aspects, it underscores ABM’s contributions to urban planning and design, enhancing our understanding of pedestrian behavior and guiding future research.

Agent:

According to agency theory, an agent is a piece of software that acts independently and interacts with its environment to achieve its goals. Agents are ideal for understanding human actions due to their proactive character and autonomy (physical situations or mental states) (Martinez-Gil et al., 2017) [18]. According to Ronald et al. [19], an agent is described as “a software component that is embedded in its environment, autonomous, and not under external control, adaptive to changes in its surroundings and proactive in consistently pursuing goals, communication capacities of obtaining goals, flexibility, resilience, and social interaction with other actors.”

Built environment:

A built environment holds a vital role in urban areas or public spaces. The area can be considered an entity that can be understood based on its dynamics or the complexity of understanding pedestrian movement in place [19]. Furthermore, the built environment can be interpreted as being built for a particular event or an activity (sports, pilgrimage, or any event).

Built environment categorization:

The built environment significantly affects pedestrians’ behaviors in various environments. Study [19] proposed categorizing the qualities of settings, walking behaviors, map representation, and projected pedestrian traffic. This “physical” method of categorization simplifies the modeling process. For instance, psychologists believe that instead of the number of individuals present, our feelings are affected by how comfortable we feel about being in a crowded area. Based on this concept, the built environment was further classified into small, large, mixed-mode, open, and hybrid spaces.

Small-scale enclosed spaces: These are made up of little rooms linked with hallways and doors. For instance, buildings frequently feature a lot of confined environments (e.g., offices and meeting rooms).

Large-scale enclosed spaces: These are often more substantial structures with broad layouts. For instance, a sports stadium has a space with seats, aisles, and exits.

Mixed-mode spaces: These comprise spaces connecting pedestrians to building entrances and other streets that may be shared with vehicles or public transportation. The pedestrian must navigate past static items, such as benches, trash cans, and garden areas. A line, which may be an organized line of individuals waiting to enter a popular store or an unorganized line of people waiting to cross the street or wait for a bus, is yet another component of this ecosystem.

Open spaces: These are made up of open spaces that may have specific paths set aside for them. Behaviors include drifting, repeated pauses, and potentially longer stays for picnics or sightseeing because the aim is most likely to relax.

Hybrid spaces: These often contain pedestrian-friendly or low-traffic locations with several attractions, including sports stadiums or universities. They incorporate actions from enclosed, mixed-mode, and open-space environments. Examples of behaviors in an open-space environment include wandering and afternoons on the lawn (e.g., moving around lecture theaters).

Pedestrian Dynamics:

Pedestrians are the most complex agents of the model. Since pedestrians cannot acquire a complete information set at a given moment, the technique of satisficing optimization is used, whereby pedestrians will try to get to their destination by minimizing the cost of their movement. Several pedestrian behaviors can occur in this environment and influence the model type. Purposeful and familiar, purposeful and unfamiliar, purposeless, required behavior (panic situation, evacuation behavior), forced waiting, and temporal constraints are some of the common pedestrian behavior types.

For pedestrians, these are the randomly generated parameters adopted [17]:

- The distance of vision: How far the pedestrian can see.

- The angle of vision: Determines the angle of vision.

- Noise: Determines the random angle to turn when facing an obstacle.

- Efficiency: Defines a threshold of acceptance between the shortest path and a more indirect alternative.

- Patience: Defines the threshold for waiting.

- Risk-taker: Defines how much utility difference s/he will accept.

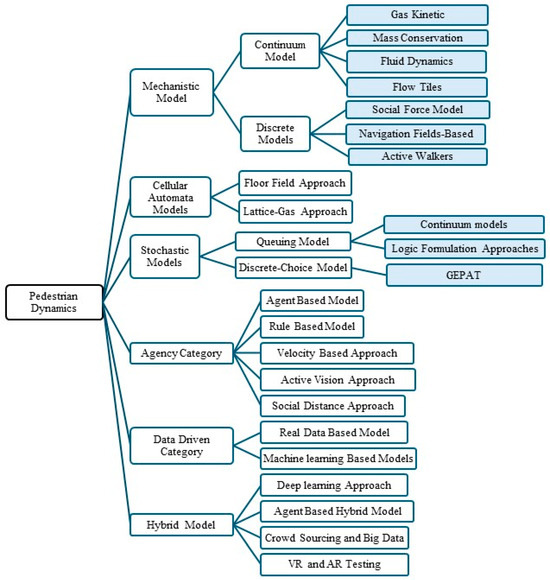

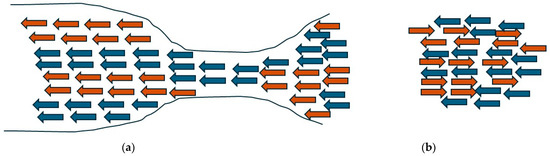

With the advancement of tools and technology, PD in built environments can also be classified into different pedestrian modeling categories [20,21,22,23], illustrated in Figure 1 (Martinez-Gil et al., 2017) [18]. Figure 2 depicts the schematic diagram of pedestrian flows with intersecting flows, bottlenecks, and lane formation of pedestrians.

Figure 1.

Pedestrian modeling classification (source: authors).

Figure 2.

Pedestrian flows: (a) lane formation and bottleneck, and (b) pedestrian flow (source: authors).

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM):

Based on the aforementioned information, ABM is one of the approaches to represent this kind of model for visualization and implementation. The behaviors of cars, pedestrians, traffic, the environment, and how they interact will be explicitly described from a theoretical perspective. In practice, the behavioral characteristics will be modeled, and the resulting dynamics will be explored by running several simulations. Executing the model several times under identical initial conditions, a specific emergent, an emerging behavior of the system is expected. Cohen (2018) [17] mentioned that the models constructed would be provided with an overview, design concept, and detail (ODD) protocol to enable comparison with other ABMs. Based on the computing capacity, the algorithm employs the idea of ODD to facilitate unambiguous communication between the environment and agents, allowing the latter to perceive and respond appropriately.

Finally, particular attention will be devoted to communicating and visualizing the model as efficiently as possible. The design principles of (i) simplify, (ii) emphasize, and (iii) explain will be used as a guideline to orientate the efforts of this work. Then, the models use the ABMs to resolve complicated issues, where CA is a suitable example of ABM. Table 1 describes the advantages and disadvantages of this modeling technique.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of ABMs.

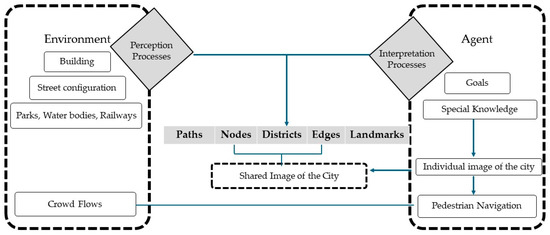

Figure 3 depicts the importance of an environment for an agent, crowd flows, and pedestrian navigation within the environment. Developing a model between the agent and the environment is essential for simulation-based PD.

Figure 3.

Agent and environment relationship [36].

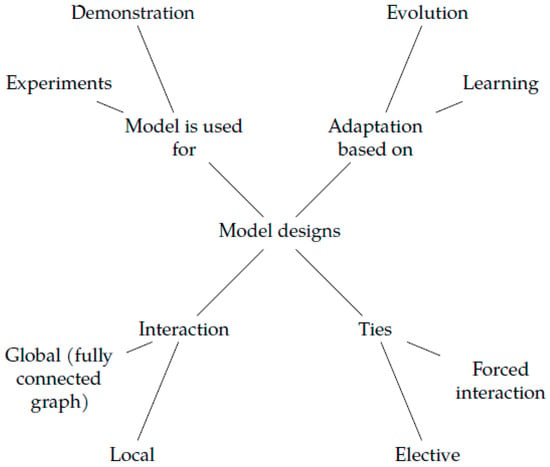

Figure 4 displays three layers of the model design concept, namely, emphasizing model design, adaptation, and interaction.

Figure 4.

First, second, and third levels of conceptualization.

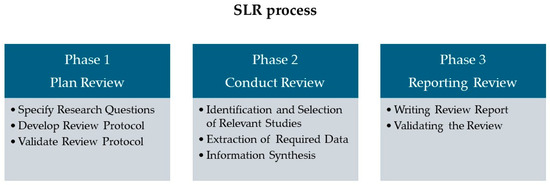

The structure of this SLR consists of three phases as Figure 5 planning, conducting, and reporting reviews. Section 2 explains the research technique. The findings of several studies, study topics, common procedures, data formats, and performance approaches are presented in Section 3. In Section 4, current solutions are discussed with their contributions, management and academic consequences, limits, future research directions, and the scientific value of this study.

Figure 5.

SLR process.

2. Research Methodology

The philosophy for developing this SLR was adopted from a previous study (Kitchenham et al., 2002) [37]. There are three phases to the research process. The initial planning phase addresses defining research topics, designing, and verifying review methods. The discovery and selection of relevant research, data extraction, and the information synthesis process are addressed in the second step. Writing and validating the SLR falls in the third phase. The flow of the three stages is depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Study selection (Source: Author).

2.1. Plan Review

The development of review protocols and the key research questions are described together with the relevant search technique in the initial stage of the research process.

Research Questions

The following research questions were established in this SLR, where potentially all of them can be addressed with appropriate solutions.

RQ 1: To what extent can ABM accurately simulate pedestrian dynamics in urban environments, considering the impact of different modeling parameters and software platforms?

RQ 2: What are the key challenges and limitations of ABM in modeling pedestrian behavior in complex built environments, and how can these challenges be addressed to improve modeling accuracy?

RQ 3: How can ABM simulations of pedestrian dynamics provide valuable insights for enhancing urban planning, design, and policy decisions, particularly in optimizing transportation hubs and public spaces for pedestrian safety and accessibility?

2.2. Review Protocols

This review follows a structured protocol to ensure a comprehensive and unbiased synthesis of the existing literature on ABM in pedestrian dynamics. The review protocol outlines the objectives, scope, and procedures for conducting the literature review.

2.3. Search Strategy

The search strategy involves systematically searching multiple academic databases, including but not limited to PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. Keywords such as “agent-based modeling,” “pedestrian dynamics,” “urban planning,” and “simulation models” were used to identify relevant studies. Boolean operators and filters were applied to refine the search results and ensure the inclusion of pertinent articles.

2.3.1. Searching Keywords

To ensure that the evaluation closely covered the built environment and technologies used for the microscopic environment using ABM, we focused our search on the most pertinent terms. Hence, we searched for phrases before performing the following steps:

- Extracting the significant distinct terms based on our research questions.

- We used different terms as keywords, such as PD, ABM.

- Updating our search terms with keywords from relevant papers.

We used the main alternatives and added “OR operator” and “AND operator” to obtain the maximum number of relevant articles, as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3.2. Literature Resources

The foundational review studies sourced their pertinent literature from databases including Web of Science, Scopus, ACM Digital Library, Springer, Science Direct, and IEEE Explorer. Such repositories, encompassing ISI and Scopus-indexed articles as well as selected papers from significant conferences, offer the broadest array of high-quality research on the topic. The search phrase was created using sophisticated search options provided by these databases. Our search included articles published from 2011 through 2023.

By focusing on articles published from 2011 onwards, the authors aimed to include the most recent and relevant research in the field of PD and ABM. This ensures that the SLR encompasses the latest developments, methodologies, and findings, which is essential for providing up-to-date insights.

Research in fields like computational modeling can evolve rapidly. By focusing on a narrower timeframe, the authors can conduct a more thorough and detailed review of the selected articles.

2.4. Conduct Review

According to the research questions, keywords, and protocols as a reference in this stage, this phase mainly deals with article inclusion and exclusion, as mentioned in Table 3.

Table 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria according to the RQ, keywords and protocol.

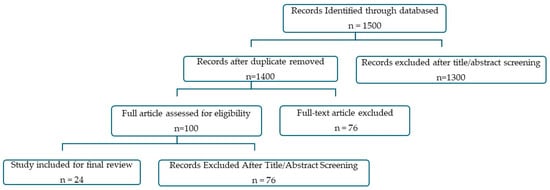

2.4.1. Study Selection

Figure 7 depicts the entire study selection procedure. A total of 1500 items were found through online search. Following filtration utilizing title, keyword, inclusion, and exclusion criteria, 300 articles remained. There were 96 articles on various concepts, such as visualization of civil engineering designs, maps, and model implementation using BIM, and 124 articles from other fields like economics and health were removed. Fifty articles are removed from the list after reading the entire article based on the RQ and information synthesis.

Figure 7.

Studies selected per year.

The methodology for choosing pertinent articles through keyword searches and article selection is detailed in Figure 7. Articles that were duplicates or did not cover all the research questions were excluded. The criteria for assessing the quality of studies are presented in Table 4, which primarily facilitated the identification of relevant, detailed, and exhaustive studies.

Table 4.

Quality checklist.

2.4.2. Data Extraction

Table 5 shows the data extraction process in systematically collecting relevant information from each included study. Key data points extracted included study objectives, methodology, key findings, limitations, and implications for urban planning. A standardized data extraction form was used to ensure consistency and accuracy in data collection. Table 6 gives a summary of the selection process.

Table 5.

Data extraction.

Table 6.

Summary of the selection process.

2.5. Analysis

The analysis involved synthesizing the extracted data to identify common themes, trends, and gaps in the literature. A narrative synthesis approach was used to provide a comprehensive overview of the state of research on ABM in pedestrian dynamics. The findings were organized to highlight the practical applications and limitations of ABM, with a focus on its relevance to urban planning and design.

2.5.1. Information Synthesis

At this stage, the gathered data were amalgamated to address the questions posed by our study, for which we utilized a narrative synthesis method. Results are discussed below.

2.5.2. Report Review

Data extracted from the primary studies were used to answer the three research questions. The guidelines [37] were closely followed in the reporting of results.

3. Results

Approximately 30 studies were included in this review. All studies were relevant to dynamic pedestrian types, the need for analysis thereof in the built environment, and to address the categories of PD using ABM to shortlist the number of studies focusing on the built environments used (Table 7).

Table 7.

RQ Studies.

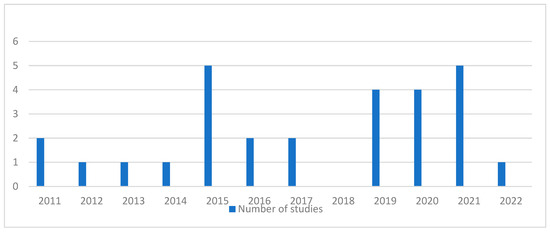

Table 8 displays the number of studies on PD conducted in built environments per year. As clearly shown in the figure, there is an increment in studies carried out in this domain.

Table 8.

Main categories of the research papers.

The research analysis organizes the studies into clear categories, emphasizing their contributions to understanding and modeling pedestrian dynamics in different contexts Table 8. Additionally, the analysis of these research papers is summarized in a tabulated format below to facilitate comprehension of their complexities Table 9.

Table 9.

Summary of results.

Each paper is meticulously reviewed under the framework of three distinct research questions. The summaries of these reviews are presented in Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12 to address the research questions comprehensively.

Table 10.

RQ 1: accuracy of ABM in simulating PD.

Table 11.

RQ 2: challenges and limitations of ABM.

Table 12.

RQ 3: insights from ABM simulations for urban planning.

4. Discussion

This discussion shed lights on the effective utilization of ABM in the urban panning spectrum with its pros and cons, including methodologies, limitations, and future research possibilities. Simulation capacities basically lie in the pedestrian dynamics-related context in an urban context, where the most advanced technology has influenced robust interventions in fields such as transportation hubs, emergency evacuation, public spaces, pedestrian behavior under panic situations, and various corridor configurations.

ABM is capable of handling agents with clear rules, and their interaction has proven very effective in capturing pedestrian movements in urban environments. López Baeza et al. (2021) [41], Gabriele F et al. (2019) [58], and Kostas Cheliotis (2020) [14] ascertained precise real-world results in pedestrian flaws related to pedestrian activity and safety. Moreover, highly accurate urban planning decisions have been made by integrating sophisticated algorithms with route choice-based landmarks.

This study analyzed the number of innovative methods that led the advancement of ABM with better applicability and capability. Ref. [41] simulated the pedestrian behavior in an urban environment and proposed required modifications to increase the activity levels in the same environment. This was enhanced to simulations of real-world scenarios by facilitating urban planning options. Therefore, it is clearly proven that the various space configurations can lead designers to identify flows and make decisions accordingly. When it comes to the pedestrian flow in transportation hubs, ABM has been used to identify demand estimates and traffic assignment models related to pedestrian dynamics in train stations, giving more priority to understanding pedestrian flow-based designing and planning [49]. Moreover, it is very interesting to note the integration of ML and ABM to simulate pedestrian flow in evacuation planning. Visual information and environmental cues in identifying evacuation patterns have become instrumental in saving lives in these scenarios [65].

The empirical basis of ABM has been truly enhanced by the use of spatiotemporal trajectory data and pedestrian volume measurements. Furthermore, the importance of various other environmental factors, including individual behaviors and demographic attributes, have taken pedestrian dynamics to the next level.

Researchers have identified key practical implications related to the urban planning and designing perspective, as follows.

Efficient and sustainable public space: Planners receive better insight on pedestrian behavior, which can practically support creating better spaces to improve overall user experience and accessibility, while maintaining security aspects, improving the flow with efficient pedestrian pathways to reduce congestion and to maintain the smooth functioning of enhanced public areas [67].

Crowd Management: Planning of large events with ABM is commendable from individual and group perspectives. Hence, urban planners and urban managers utilize the simulations to control the overall city management with crowd control and also emergency evacuation-related planning [68].

Policy Development: During policy formulation, it is very important to understand the walkability, traffic conditions, and overall urban mobility to formulate necessary policies such as use of public transportation, promoting walkability, or promoting cycling, etc., based on ABM simulations [69].

Sustainable Urban Planning: ABM mostly enables trial and error without any cost or risk in different scenarios. Therefore, modeling and implementing concepts in real situations with environment-friendly and sustainable options have become possible [70].

4.1. Limitations

While ABM demonstrates substantial potential, certain limitations and challenges remain. These include the calibration and validation of models, the computational intensity of simulating large populations, and the need for accurate and comprehensive datasets for model parameterization. Moreover, as highlighted by studies such as those by Zi-Xuan Zhou et al. (2021) [65] and Mohamed Hussein and Tarek Sayed (2019) [64], the variability in human behavior and the dynamic nature of pedestrian flows in complex environments pose ongoing challenges to ABM’s predictive accuracy. Further, J Zhang et al. (2015) [53] highlighted the challenges of model scalability.

The availability of data related to targeted journals and databases is the most significant limitation of this SLR due to diverse built environment implementations in constructions and human psychology, which necessitated some rules in selecting related articles. Another disadvantage is the bias in selecting articles, SLRs, and surveys. However, the selection of studies published in English was a minor constraint.

4.2. Future Recommendations

This section outlines several key future research directions aiming to enhance the scope of ABM in the field of PD. The researchers’ understanding about urban environment and PD explored in this paper showcases significant potential in practical urban planning decisions. As cities continue to evolve, it is imperative to explore new research avenues that can further harness the capabilities of ABM.

Proposed future research directions suggested by the researchers include integrating advanced data analytics and real-time data, comprehensive calibration and validation techniques, exploring human-centric urban design, incorporating cognitive and behavioral modeling, leveraging machine learning for enhanced predictive capabilities, addressing the impacts of micro-mobility and pandemics, and developing real-time decision support systems, explained in separate sections.

In addition, the researchers also identified some emerging possibilities to integrate ABM in the fields of urban digital twins, application of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technologies, exploring social and ethical implications of ABM in PD, environmental impact modeling, and traffic management systems, and adopting of cross-disciplinary approaches concerning ABM and PD.

The following Table 13 provides a comprehensive overview of these future research directions, including the current focus, expanded suggestions, practical examples, and suggested tools or processes to explore these avenues. This comprehensive guide aims to inspire and direct future studies, encouraging the continued advancement of ABM in creating safer, more efficient, and more inclusive urban environments.

Table 13.

Summary of Future Recommendation.

5. Conclusions

The advancement of technology and the evolution of human psychology and behaviors significantly influence industrial and commercial projects, underscoring the need for dynamic and nuanced approaches to urban planning and PD analysis. This study embarked on a comprehensive SLR with the primary objective of examining pedestrian dynamics within the built environment, focusing on pedestrian modeling, computational techniques, and the tools utilized in model development. The investigation into ABM revealed its profound efficacy in understanding and simulating PD, marking a significant contribution to the field by offering insights into pedestrian behavior in microscopic environments and demonstrating the potential for achieving optimal outcomes from the datasets used for model development.

Contrary to previous studies that explored PD and the built environment using alternative modeling approaches, this SLR uniquely underscores the utility of ABM in developing detailed pedestrian dynamics simulations. It brings to light the adaptability of ABM in calibrating, validating, and verifying models to meet high accuracy levels, a critical aspect in modeling pedestrian behaviors in various urban settings. This study thus stands out for providing an extensive insight into the application of ABM, showcasing its unparalleled ability to model complex pedestrian interactions and movements with precision.

For researchers and practitioners engaged in a wide array of industrial and commercial projects, this SLR offers invaluable guidance on the latest tools and computational techniques best suited for different environments, scales, and observation contexts using ABM. It acknowledges, however, the challenges associated with employing specific modeling tools across varied instances of the built environment. For example, while NetLogo presents difficulties in micro-level application, CA models show limitations in accommodating multi-agent pedestrian simulations, and Unity 3D may hinder the data fetching process due to its computational intensity.

Despite these challenges, the rigorous process and broad scope of this SLR emphasizes the value of ABM in studying, designing, implementing, and visualizing pedestrian dynamics across any built condition or place. It highlights the necessity of continuing to refine and adapt ABM techniques to overcome existing limitations and fully harness the potential of this modeling approach in contributing to more informed, effective, and human-centric urban planning and design. The integration of ABM into the analysis of pedestrian dynamics within the built environment promises to enrich understanding and management of urban spaces, ensuring environments better tailored to the evolving needs and behaviors of their inhabitants. Despite its challenges, the continued evolution of ABM methodologies holds the promise of even more sophisticated and accurate simulations, guiding the future of urban design towards more human-centric environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.N.L. and A.A.B.D.P.A.; methodology, R.G.N.L.; software, R.G.N.L.; validation, R.G.N.L.; formal analysis, R.G.N.L. and A.A.B.D.P.A.; investigation, R.G.N.L. and A.A.B.D.P.A.; resources, R.G.N.L. and A.A.B.D.P.A.; data curation, R.G.N.L. and A.A.B.D.P.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.N.L. and A.A.B.D.P.A.; writing—review and editing, R.G.N.L., P.V.G. and A.A.B.D.P.A.; visualization, R.G.N.L., P.V.G. and A.A.B.D.P.A.; supervision, P.V.G.; project administration, R.G.N.L. and P.V.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acronym

| ABM | agent-based modeling | |

| AI | artificial intelligence | |

| SLR | systematic literature review | |

| CA | cellular automata | |

| PD | pedestrian dynamics | |

| BE | built environment | |

| ML | machine learning | |

| AutoCAD | auto computer-aided design | |

| GA | genetic algorithm | |

| ORCA | optimal reciprocal collision avoidance | |

| AR | augmented reality | |

| VR | virtual reality |

References

- Ton, D.; Duives, D.C.; Cats, O.; Hoogendoorn-Lanser, S.; Hoogendoorn, S.P. Cycling or walking? Determinants of mode choice in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 123, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibian, M.; Hosseinzadeh, A. Walkability index across trip purposes. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazghandi, A. Techniques, Advantages and Problems of Agent Based Modeling for Traffic Simulation. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Issues 2012, 9, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, M.; Sayed, T.; Eng, P. A Methodology for the Microscopic Calibration of Agent-Based Pedestrian Simulation Models. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 3773–3778. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M.; Longley, P. Fractal Cities: A Geometry of Form and Function; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780124555709. [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak, M. From dawn to dusk: Daily fluctuations in pedestrian traffic in the city center. Simulation 2024, 100, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Nordfjaern, T.; Klöckner, C.A. A systematic review of the agent-based modelling/simulation paradigm in mobility transition. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 184, 122011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, A.; Castle, C.; Batty, M. Key Challenges in Agent-Based Modelling for Geo-Spatial Simulation 2. The Development of Agent-Based Models. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2008, 32, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Q.; Guo, R.Y.; Tian, F.B.; Zhou, S.G. Macroscopic modeling of pedestrian flow based on a second-order predictive dynamic model. Appl. Math. Model. 2016, 40, 9806–9820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.L.; Lo, S.M.; Liu, S.B.; Kuang, H. Microscopic modeling of pedestrian movement behavior: Interacting with visual attractors in the environment. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2014, 44, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordeux, A.; Lämmel, G.; Hänseler, F.S.; Steffen, B. A mesoscopic model for large-scale simulation of pedestrian dynamics. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 93, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, B. Agent-based modeling: Methods and techniques for simulating human systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 7280–7287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Agent-based modeling in urban and architectural research: A brief literature review. Front. Archit. Res. 2012, 1, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheliotis, K. An agent-based model of public space use. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 81, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Méndez, M.; Olaya, C.; Fasolino, I.; Grimaldi, M.; Obregón, N. Agent-Based Modeling for Urban Development Planning based on Human Needs. Conceptual Basis and Model Formulation. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.; Rao, S. Agent-Based Modeling of Emergency Evacuations Considering Human Panic Behavior. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2018, 5, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Microscopic Pedestrian Simulation: An Exploratory Application of Agent-Based Modelling. Ph.D. Thesis, University College of London, London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gil, F.; Lozano, M.; Fernández, F.; García-fernández, I.; Fernández, F.; València, U. De Emergent behaviors and scalability for multi-agent reinforcement learning-based pedestrian models. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2017, 74, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, N.; Sterling, L.; Kirley, M. Evaluating JACK sim for agent-based modelling of pedestrians. In Proceedings of the Proceedings—2006 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Intelligent Agent Technology (IAT 2006 Main Conference Proceedings), IAT’06, Hong Kong, China, 18–22 December 2006; pp. 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Li, T.; Gong, X.; Peng, B.; Hu, J. A review on crowd simulation and modeling. Graph. Models 2020, 111, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, C.; Branki, C.; Unland, R. A Framework for Agent-Based Simulations of Hybrid Energy Infrastructures. In Proceedings of the 2012 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), Wroclaw, Poland, 9–12 September 2012; pp. 1293–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Niemann, J.H.; Winkelmann, S.; Wolf, S.; Schütte, C. Agent-based modeling: Population limits and large timescales. Chaos 2021, 31, e0031373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAl, C.M.; North, M.J. Tutorial on agent-based modelling and simulation. J. Simul. 2010, 4, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, G. Potentialities and Limitations of Agent-Based Simulations: An Introduction; Revue Française de Sociologie: Paris, France, 2014; Volume 55, ISBN 9782724633771. [Google Scholar]

- Richetin, J.; Sengupta, A.; Perugini, M.; Adjali, I.; Hurling, R.; Greetham, D.; Spence, M. A micro-level simulation for the prediction of intention and behavior. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2010, 11, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.J.; Koehler, M.; Lynch, C.J. Methods That Support the Validation of Agent-Based Models: An Overview and Discussion. JASSS 2024, 27, 5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviero, R.; Hellton, K.H.; Haug, O.; Engø-Monsen, K.; Rognebakke, H.; Canright, G.; Frigessi, A.; Scheel, I. An agent-based model with social interactions for scalable probabilistic prediction of performance of a new product. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Coll Besa, M.; Forrester, J. Agent-Based Modelling: A Tool for Addressing the Complexity of Environment and Development Policy Issues; Working Paper 2016-12; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fabris, B. The User Needs of Agent-Based Modelling Experts: What Information Architecture Reveals about ABM Frameworks 2023. pp. 1–32. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1766061&dswid=3564 (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Axtell, R.L.; Doyne Farmer, J. Agent-Based Modeling in Economics and Finance: Past, Present, and Future; American Economic Association: Nashville TN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Antelmi, A.; Caramante, P.; Cordasco, G.; D’Ambrosio, G.; De Vinco, D.; Foglia, F.; Postiglione, L.; Spagnuolo, C. Reliable and Efficient Agent-Based Modeling and Simulation. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2024, 27, 5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Lorscheid, I.; Millington, J.D.; Lauf, S.; Magliocca, N.R.; Groeneveld, J.; Balbi, S.; Nolzen, H.; Müller, B.; Schulze, J.; et al. Simple or complicated agent-based models? A complicated issue. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 86, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikrishnan, V.; Keller, K. Small increases in agent-based model complexity can result in large increases in required calibration data. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 138, 104978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovo, E.; Pangallo, M.; Rivkin, J.; Rizzo, L.; Siggelkow, N. Sensitivity analysis of agent-based models: A new protocol. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory 2022, 28, 52–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.; Kelleher, J.D. A framework for validating and testing agent-based models: A case study from infectious diseases modelling. In Proceedings of the Modelling and Simulation 2020—The European Simulation and Modelling Conference, Toulouse, France, 21–23 October 2020; pp. 318–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hassannayebi, E.; Memarpour, M.; Mardani, S.; Shakibayifar, M.; Bakhshayeshi, I.; Espahbod, S. A hybrid simulation model of passenger emergency evacuation under disruption scenarios: A case study of a large transfer railway station. J. Simul. 2020, 14, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.A.; Pfleeger, S.L.; Pickard, L.M.; Jones, P.W.; Hoaglin, D.C.; El Emam, K.; Rosenberg, J. Preliminary guidelines for empirical research in software engineering. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2002, 28, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, A.; Croitoru, A.; Lu, X.; Wise, S.; Irvine, J.M.; Stefanidis, A. Walk this way: Improving pedestrian agent-based models through scene activity analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2015, 4, 1627–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asriana, N. Pedestrian Behavior for Developing Strategy in Tourism Area; Agent-Based Simulation. Dimens. J. Archit. Built Environ. 2021, 48, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomena, G.; Manley, E.; Verstegen, J.A. Perception of urban subdivisions in pedestrian movement simulation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, J.L.; Carpio-Pinedo, J.; Sievert, J.; Landwehr, A.; Preuner, P.; Borgmann, K.; Avakumović, M.; Weissbach, A.; Bruns-Berentelg, J.; Noennig, J.R. Modeling pedestrian flows: Agent-based simulations of pedestrian activity for land use distributions in urban developments. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.X.; Nakanishi, W.; Asakura, Y. Route choice in the pedestrian evacuation: Microscopic formulation based on visual information. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 562, 125313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.Y.; Huang, H.J.; Wong, S.C. Route choice in pedestrian evacuation under conditions of good and zero visibility: Experimental and simulation results. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2012, 46, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovreglio, R.; Borri, D.; Dell’Olio, L.; Ibeas, A. A discrete choice model based on random utilities for exit choice in emergency evacuations. Saf. Sci. 2014, 62, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwakoti, N.; Sarvi, M.; Rose, G.; Burd, M. Animal dynamics based approach for modeling pedestrian crowd egress under panic conditions. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2011, 45, 1433–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloma, C.; Perez, G.J.; Gavile, C.A.; Ick-Joson, J.J.; Palmes-Saloma, C. Prior individual training and self-organized queuing during group emergency escape of mice from water pool. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, D.R.; Soria, S.A.; Josens, R. Faster-is-slower effect in escaping ants revisited: Ants do not behave like humans. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. An Agent-based Evacuation Modeling of Underground Fire Emergency. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hänseler, F.S.; Bierlaire, M.; Scarinci, R. Assessing the usage and level-of-service of pedestrian facilities in train stations: A Swiss case study. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 89, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.; Ali, N.; Rajasekar, E. Evaluating the dynamics of occupancy heat gains in a mid-sized airport terminal through agent-based modelling. Build. Environ. 2021, 204, 108147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, X. Simulation of passenger motion in metro stations during rush hours based on video analysis. Autom. Constr. 2019, 107, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Li, H.; Tian, J. Research on the Effects of Heterogeneity on Pedestrian Dynamics in Walkway of Subway Station. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2016, 2016, 4961681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Klingsch, W.; Schadschneider, A.; Seyfried, A. Transitions in pedestrian fundamental diagrams of straight corridors and T-junctions. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2011, 2011, P06004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, J.; Hope, M.; Ley, H.; Sokolov, V.; Xu, B.; Zhang, K. POLARIS: Agent-based modeling framework development and implementation for integrated travel demand and network and operations simulations. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 64, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Sayed, T. A unidirectional agent based pedestrian microscopic model. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 42, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaziyeva, D.; Stutz, P.; Wallentin, G.; Loidl, M. Large-scale agent-based simulation model of pedestrian traffic flows. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2023, 105, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Kim, K.-J.J.; Maglio, P.P. Smart cities with big data: Reference models, challenges, and considerations. Cities 2018, 82, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomena, G.; Manley, E.; Verstegen, J.A. Route choice through regions by pedestrian agents. In Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, LIPIcs, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Spatial Information Theory, Regensburg, Germany, 9–13 September 2019; Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fur Informatik GmbH, Dagstuhl Publishing: Wadern, Germany, 2019; Volume 142. [Google Scholar]

- Filomena, G.; Verstegen, J.A. Modelling the effect of landmarks on pedestrian dynamics in urban environments. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 86, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcimartín, A.; Pastor, J.M.; Ferrer, L.M.; Ramos, J.J.; Martín-Gómez, C.; Zuriguel, I. Flow and clogging of a sheep herd passing through a bottleneck. Phys. Rev. E-Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2015, 91, e022808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, M.; Sayed, T. A bi-directional agent-based pedestrian microscopic model. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2017, 13, 326–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidich, M.; Geiss, F.; Mayer, H.G.; Pfaffinger, A.; Royer, C. Waiting zones for realistic modelling of pedestrian dynamics: A case study using two major German railway stations as examples. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2013, 37, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gil, F.; Lozano, M.; García-fernández, I.; Fernández, F.; València, U. De Modeling, evaluation, and scale on artificial pedestrians: A literature review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2017, 50, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Sayed, T. Validation of an agent-based microscopic pedestrian simulation model in a crowded pedestrian walking environment. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2019, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.X.; Nakanishi, W.; Asakura, Y. Data-driven framework for the adaptive exit selection problem in pedestrian flow: Visual information based heuristics approach. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 583, 126289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Brandt, S.A.; Seipel, S.; Ma, D. Simple agents—Complex emergent path systems: Agent-based modelling of pedestrian movement. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2023, 51, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezbradica, M.; Ruskin, H.J. Understanding Urban Mobility and Pedestrian Movement. In Smart Urban Development; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-1-78985-042-0. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, J.; Kim, N.; Wysk, R.A.; Rothrock, L.; Son, Y.; Oh, Y.; Lee, S. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory Agent-based simulation of affordance-based human behaviors in emergency evacuation. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2013, 32, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, P.; Leao, S.; Gudes, O.; Pettit, C. A simple agent-based model for planning for bicycling: Simulation of bicyclists’ movements in urban environments. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2024, 108, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wey, W. Sustainable Urban Transportation Planning Strategies for Improving Quality of Life under Growth Management Principles. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 44, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).