Abstract

Defects in apartment buildings significantly impact the convenience and safety of residents, and their prevalence has been steadily increasing. This study prioritizes the key defects in apartment buildings to enhance quality management. The primary causes of defects were identified by focusing on frequently occurring issues such as tile installation, flooring, wallpaper, PL windows, and kitchen furniture. A literature review was conducted to analyze the main types of defects, and expert focus group interviews were held to investigate the causes of defects and potential countermeasures. Following this, the analytic hierarchy process was employed to assess the relative importance of these defects and establish their prioritization. The findings indicated that structural issues and material-related factors, particularly flooring and window installation, were the primary causes. Based on these insights, this study proposes a strategic approach to improving quality management in apartment buildings. This research serves as a valuable reference for developers, contractors, and policymakers in defect prevention and management.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Purpose of the Study

The proportion of individuals residing in multifamily housing is increasing globally, reflecting a growing demand for these dwellings. In the United States, 529,000 new multifamily housing units were initiated in 2022, representing a 14% increase from 2021. Additionally, 55% of renters resided in multifamily buildings comprising two or more units [1,2,3]. In Europe, multifamily housing has become the primary living space for the majority of populations, with occupancy rates of 65%, 62%, 59%, 56%, and 53% in Spain, Switzerland, Greece, Germany, and Italy, respectively [4,5]. Notably, in South Korea, multifamily housing accounts for 78% of the total housing stock, the highest proportion globally.

As the occupancy rates and supply of multifamily housing continue to rise, defect issues arising during the construction, sale, and rental processes have also increased. A study by Deakin and Griffith Universities in 2019 [6] revealed that 74% of apartments completed between 2008 and 2017 in Victoria, Canada, exhibited defects. In Australia, 53% of apartments completed between 2016 and 2022 experienced at least one major defect [7]. In 2018, 69% of newly constructed homes in the United Kingdom had five or more defects [8]. In South Korea, 824,198 defects were reported across 207,765 housing units, with an average of four defects per unit [9]. Recently, collective complaints related to housing quality and defects, such as elevator malfunctions, water leakage, condensation issues, and shoe cabinet tipping accidents, have been filed, reflecting growing dissatisfaction among residents toward multifamily housing [10,11] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Multifamily housing occupancy rates calculated in various countries [1,2,3,4,5].

Defects in multifamily housing impose both psychological and physical distress on residents, while also leading to financial losses and a decline in the credibility of construction companies. Despite advancements in construction technology, defects continue to increase due to the lack of prioritized management for major defect types. Instead, the focus has generally been limited to analyzing causes within the broader construction and design processes, resulting in inadequate quality control [12].

Previous studies on the analysis and management of defects in multifamily housing have primarily analyzed defect types in specific regions or limited complexes, without considering their relative importance. These studies have focused on identifying improvement factors for each defect type during the design or construction phases, but this approach lacks prioritization in terms of quality control, making it difficult to achieve effective defect reduction [13,14].

Moreover, defects occurring during the design and construction phases of multifamily housing often serve as the primary causes of secondary defects, compounding their negative impacts. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and prevent potential defect factors during these phases [15].

In fact, the number of secondary defects caused by the six major common defect categories, as recorded during the construction completion phase and pre-occupancy inspections for 10 LH multifamily housing complexes (totaling 6846 units) completed between 2015 and 2018, is shown in Table 2. Among the common defect categories, wallpaper installation accounted for the highest number of secondary defects (8141 cases), with the defect types primarily classified as dents, scratches, breakages, stains, and scuffs [16].

Table 2.

Secondary defect counts and rates in six major common defect categories, modified by [16].

Therefore, analyzing and categorizing major defects to establish quality management priorities is essential in reducing defects in multifamily housing, improving the overall housing quality, and preventing secondary defects.

The global rise in multi-unit residential construction has led to the increasing prevalence of defects, which impose significant economic, functional, and psychological burdens on stakeholders. This research addresses these challenges by providing a systematic framework for the prioritization of defects, enabling stakeholders to allocate resources efficiently and focus on high-priority issues. For instance, addressing critical defects, such as PL window malfunctions, can substantially improve resident satisfaction while reducing maintenance costs. Furthermore, the findings of this research serve as a valuable reference for policymakers and construction firms to develop targeted strategies and regulations for defect prevention and quality control, ultimately enhancing the overall sustainability of residential construction projects.

This research aims to identify priority levels for defect management based on the perceived importance of major defect types as identified by construction field experts and researchers. The study focuses on windows, kitchen furniture, wallpaper, paint, flooring, and tiling, with the goal of devising effective and efficient defect mitigation measures. To achieve this, the research identifies six major common defect categories with high importance among various defect types, subdivides and classifies the analysis items, and proposes quality management strategies for each project phase through the development of a systematic quality management framework and checklists.

1.2. Research Methods and Procedures

This research determined the priority levels for defect management in multifamily housing by categorizing defect types and evaluating their perceived importance through an analytic hierarchy process (AHP) survey conducted with construction industry professionals. The research focused on critical defect types. Accordingly, it was conducted using the methods and procedures outlined below.

First, based on audit reports from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT) and data from South Korean public institutions such as the Korea Land and Housing Corporation (LH), this research compiled the occurrence statuses and types of defects reported up to 2018 within various categories of multifamily housing, including economy class housing, special-purpose housing, and comfort class housing. Additionally, corporation and quality standards and specifications from the United States were reviewed to select six major defect-prone categories in multifamily housing and examine the causes and current statuses of defects. Second, a comprehensive review of the existing literature was conducted to identify the limitations in previous research and the current defect management practices. This step helped to highlight the research gaps and limitations in defect management, thereby justifying the necessity of this study.

Third, a focus group interview (FGI) survey was conducted with construction field professionals and researchers, such as the technical managers of construction companies, site managers, and supervisors from the Korea Land and Housing Corporation, to evaluate defect causes, countermeasures, and the appropriateness of the defect analysis items. Fourth, an AHP survey was conducted with participants and experts involved in each project phase, including design, construction, maintenance, and management, to identify and prioritize the major defects that may occur in multifamily housing. This survey aimed to provide insights into key areas of defect management and strategies to advance quality control in multifamily housing. Fifth, we employed a combination of the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) and clustering techniques to evaluate and group the defect types based on their relative priorities. First, the weights for defect causes were derived using the analytic hierarchy process (AHP), reflecting the relative importance of each cause. These weights were applied in the TOPSIS framework to quantitatively assess the relative significance of each defect type. In the TOPSIS process, a normalized decision matrix was constructed by integrating the weights, followed by calculating the distances from the ideal solution (maximum values) and the negative ideal solution (minimum values) for each defect type. TOPSIS scores were then computed to rank the defect types. Subsequently, K-means clustering was applied to the TOPSIS scores to group defect types with similar priority levels. The optimal number of clusters was determined to be three using the elbow method. The resulting clusters were labeled as the “low-priority group”, “moderate-priority group”, and “high-priority group”, and the characteristics of each cluster were analyzed. Finally, quality management strategies for each project phase were developed based on the evaluation and grouping results of the identified priorities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Building Defects and Effects

In the construction field, defects are typically defined as flaws that compromise the safety, functionality, or esthetics of buildings or facilities due to errors and mistakes during the construction process [17]. Furthermore, the meaning of defects in multifamily housing varies depending on the historical context, the economic conditions, and the individual circumstances of the residents [18]. Building defects can have numerous effects, including economic consequences, structural integrity issues, and decreased user satisfaction [19,20,21,22,23].

Shinde and Meshram [24] identified and classified the factors contributing to building defects and failures, proposing strategies to minimize the time and costs in construction projects. Their study emphasizes the severity of defects and their impacts across warranty periods, highlighting the role of the design, materials, and construction quality. Although limited to existing case studies, this research highlights how building defects can lead to unnecessary expenses and project delays, ultimately affecting the feasibility of a project. Additionally, Kim et al. [25] analyzed 16,108 defects across 133 buildings in South Korea in 2019, examining factors such as maintenance, the construction quality, and design flaws. The study found that, when defects occur, substantial repair costs arise, particularly in the reinforced concrete and waterproofing processes, and these costs can increase if timely action is not taken. Although limited to defects observed in residential buildings in South Korea between 2008 and 2018, this study is significant in analyzing defect patterns during the warranty period and providing strategies to minimize losses. In a related study, Milion [26] explored the relationship between defects and user satisfaction in Brazilian residential units by combining data from a 2016 user satisfaction survey with information from the Technical Assistance Department. The findings indicate that users who experienced efficient and prompt defect management reported higher satisfaction and a more positive overall perception of the project. Moreover, major defects, as opposed to minor ones, have a lasting negative impact on user satisfaction, even after repairs. These findings underscore the importance of prioritizing and categorizing defect management.

2.2. Causes of Defects

Ifran Che-Ani et al. [27] reported that building defects arise from various factors, including building materials, design processes, and management practices. They assessed building conditions using a Condition Survey Protocol 1 matrix to study the frequency and severity of defects. Their study concluded that defect occurrences are not attributed to a single cause but stem from numerous underlying issues. However, the new matrix system may require further validation and broader acceptance within the industry. Similarly, Gatlin [28] investigated factors such as design inadequacies, poor workmanship, and material misuse through case studies, forensic analysis, and visual inspections, identifying the primary causes of building defects, such as deficiencies in design, issues in the construction process, inappropriate use contrary to the design, and the mismanagement of maintenance. The study also noted that the defects observed in existing public housing were primarily caused by wear and damage resulting from inadequate maintenance.

According to Pereira et al. [29], inadequate or low-quality materials can lead to defects. This study, which considered 12 building elements or materials, integrated defect causes within a global inspection system and analyzed the relationship between the defect frequency and causes, primarily reviewed by professionals, such as supervising engineers, site engineers, and site managers. However, the 12 elements/materials considered may not encompass all potential defect causes. In a study by Muhwezi et al. [30], surveys and interviews were conducted with 210 respondents, including supervising engineers, site managers, and clients, to evaluate the causes and impacts of building defects. A quantitative analysis of the collected data using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and Microsoft Excel indicated that inadequate supervision during the construction phase, insufficient inspections, and a lack of qualified personnel contributed to the occurrence of defects. However, this study was limited by its focus on a specific geographic area and reliance on self-reported data. Additionally, various factors, such as external environmental influences (e.g., moisture and wind loads), design stage errors, human errors resulting from a lack of experience and inadequate skills, financial constraints, and inefficient communication among stakeholders, can contribute to building defects [31,32,33,34,35].

2.3. Classification of Defects

The study by Alomari [36], which categorized 57 building defect factors into five major groups—design, construction, materials, human factors, and external factors—demonstrated that classifying building defects is crucial in identifying general contributing factors, thereby aiding participants in developing strategies for efficient defect reduction. Furthermore, Macarulla et al. [37], who focused on construction practices in Spain, noted that, although several structured classification systems for building defects already exist, they often fail to account for regional and national characteristics, making it challenging to apply these systems effectively onsite. Therefore, developing a defect classification system that incorporates regional characteristics, is validated by experts, and is grounded in previous studies and project outcomes could improve the construction quality and lead to significant economic and time-saving benefits in projects.

2.4. Evaluating Building Defect Importance

S. Shooshtarian et al. [38] identified materials, fabrication techniques, and designs as key factors contributing to building defects, and they utilized the DEMATEL approach, along with expert reviews, to determine the importance and prioritization of these defects. While this approach provides a detailed understanding of the interactions among various causes and facilitates the efficient classification of defects, the study’s results exhibit inconsistencies, as they vary depending on the specific circumstances under which the research was conducted. F. Faqih and T. Zayed [39] identified and classified defects based on condition ratings through visual inspections by experts, as well as technologies such as drones and imaging systems. This approach enabled smooth data collection and analysis, allowing for immediate defect repair and management. However, a limitation is that the classification of the defect importance can be subjective, as the opinions on defect prioritization may vary among experts. S. Zuraidi et al. [40] used the AHP to determine criteria and priority rankings related to defects in Malaysia’s national heritage buildings. A survey of 20 experts was conducted, with a sensitivity analysis performed through pairwise comparisons. This method allowed for a systematic evaluation of the complex criteria and attributes associated with defects in national heritage buildings, although the limited sample size of 20 experts poses a challenge for generalization. Y. Juan et al. [41] applied a 10-level Risk Priority Number (RPN) ranking within the FMEA framework, specifically targeting construction projects. Through RPN rankings, project managers can effectively identify and manage critical defect factors, enhancing quality control in construction projects. However, if the data values are inaccurate or erroneous, RPN calculations may be compromised. Additionally, implementing this method requires the further training and development of experts, which is a noted limitation.

2.5. Review of Limitations in Previous Studies

The existing studies on defects in multifamily housing exhibit the following limitations.

First, while many studies have focused on identifying defect types and analyzing their causes, they often adopt short-term, case-based approaches, which makes it challenging to generalize the findings across various regions or contexts. Notably, these studies frequently fail to adequately account for regional characteristics and differences in construction environments, resulting in proposed management strategies that may conflict with the local construction practices in specific countries or regions. This underscores the difficulty in developing a globally applicable and integrated defect management framework.

Second, the existing research lacks systematic methodologies for the evaluation of the relative importance of defect types, often relying primarily on the defect occurrence frequency as the key metric. This approach fails to adequately incorporate the perspectives of diverse professionals, leading to a disconnect between the identification of major defects and their relative importance across different phases of construction. As a result, this weakens the integration of management strategies across project phases and undermines the effectiveness of quality control and defect reduction efforts.

Third, the research scope is frequently limited to the design and construction stages, with insufficient consideration given to the post-construction maintenance phase. Consequently, challenges arise in establishing effective defect prevention strategies during the design and construction phases. As outlined above, the current defect management framework for multifamily housing struggles to effectively prioritize key defect types and lacks robust integration across the design, construction, and maintenance phases. Defect management often relies heavily on reactive measures rather than proactive prevention, which leads to increased resident dissatisfaction and a decline in construction quality.

Table 3 summarizes the objectives, research targets, factors, research methods, results, and limitations of the studies mentioned in the literature review.

Table 3.

Literature review table.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. FGI Survey

The FGI survey is a qualitative research method used to gather insights from a group of professionals within a specific field regarding their experiences and perceptions of a particular topic. This method is effective in understanding and analyzing complex phenomena and factors, and it is widely used across various fields, including healthcare, engineering, and architecture [42,43]. The validity of the research findings improves with a larger participant pool in FGI surveys, allowing for a more effective and multidimensional approach [44]. In particular, FGI surveys allow for simultaneous data collection from multiple participants, which saves time and costs and provides an advantage in gaining insights into less understood areas [45,46].

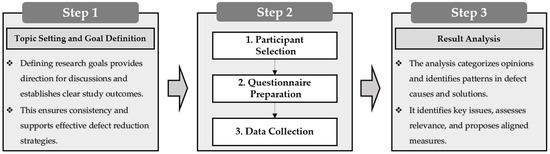

The FGI survey process includes (1) topic selection and goal definition, (2) participant selection, (3) questionnaire preparation, (4) data collection, and (5) result analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Procedure of FGI.

3.2. AHP Analysis

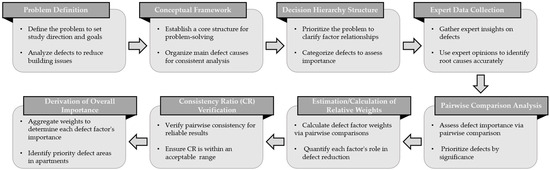

The AHP method, developed by Saaty in the early 1970s, is a multicriteria decision-making technique that hierarchically structures and resolves complex decision-making problems. The AHP organizes a given problem into multiple criteria and alternatives within a hierarchical framework, making it well suited for the determination of priorities by assessing the relative importance of each element [47,48,49]. This method assigns weights through pairwise comparisons of attributes using a basic scale to help respondents to focus on evaluating attributes at each level, typically conducted via surveys or interviews [50]. The AHP method generally proceeds in four stages: (1) the definition of the problem and establishment of a hierarchical structure, (2) the construction of pairwise comparison matrices, (3) the calculation of weights and verification of consistency, and (4) the derivation and application of the results. A detailed illustration of the analytical procedure for the AHP is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Procedure of AHP analysis.

The first step in the AHP method is defining the problem and establishing a hierarchical structure to resolve it. Typically, this involves setting the goal at the highest level, followed by the main criteria at subsequent levels that are necessary to achieve the goal. Additional sublevels can be established by subdividing the main criteria. Specific alternatives aimed at achieving this goal are assigned to the lowest priority level. Pairwise comparisons are then performed. The pairwise comparison matrix, developed based on expert opinions, quantifies subjective judgments, enabling the objective evaluation of outcomes [51,52]. Additionally, this matrix facilitates objective and reliable decision-making among diverse expert opinions on defects in multifamily housing [18].

When multiple pairwise comparisons are conducted, consistency issues may arise in the evaluation scores. Therefore, before integrating the weights of the values assessed by the experts, the consistency ratio (CR) is verified, and the analysis is conducted only for responses that meet a certain threshold. Generally, if the CR value is 0.1 or lower, the evaluation is considered consistent and deemed reliable. Finally, the geometric mean is applied to aggregate the relative weights of each criterion obtained from the pairwise comparisons.

3.3. TOPSIS Analysis and Clustering

To further enhance the prioritization of defect management items, this study incorporated the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), a well-established multicriteria decision-making methodology [53]. TOPSIS was chosen for its ability to rank alternatives by comparing each to an ideal solution, which aligned with this study’s objective of systematically addressing defect management priorities. The procedure involved the following steps: (1) constructing a decision matrix to evaluate defect-related criteria, (2) normalizing the matrix, (3) determining the positive and negative ideal solutions, (4) calculating the separation measures from the ideal solutions, and (5) computing the relative closeness to the ideal solution to rank the defect types. By integrating TOPSIS, this study identified the most critical defects requiring immediate attention, ensuring balanced and objective prioritization.

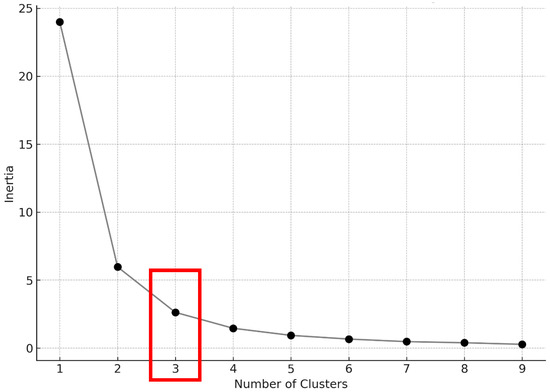

Building upon the results of the TOPSIS analysis, clustering techniques were applied to group defect items with similar characteristics, enabling a refined understanding of the defect patterns. Specifically, the K-means clustering algorithm was employed due to its simplicity and effectiveness in categorizing multi-dimensional data. The number of clusters was determined using the elbow method, which evaluates the variance explained by each cluster count to identify the optimal clustering point. This combined approach of TOPSIS and clustering not only corroborated the prioritization results but also aided in visualizing and addressing patterns that may not be apparent through standalone prioritization. Consequently, this dual methodology provides a comprehensive foundation for the development of targeted quality management strategies that address both critical defects and recurring trends effectively.

4. Model Framework Development

4.1. Framework Model

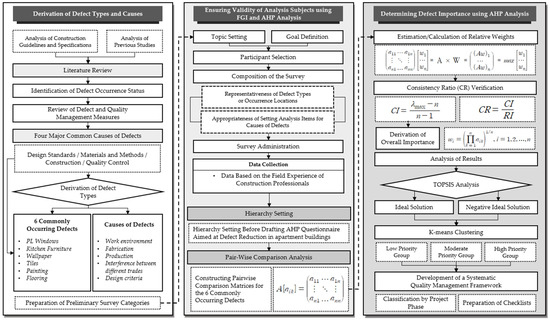

This section outlines a three-step framework designed to identify and prioritize defect risk factors in various types of multifamily housing buildings, with the goal of establishing quality management strategies across project phases. The first step involved identifying key factors related to defects in multifamily housing structures based on the literature review and previous studies. These factors formed the foundation for the final risk assessment model, which was further refined through an FGI survey in the next step. The second step involved executing the FGI survey, based on the risk factors identified in the literature review. This survey gathered expert insights from a group of industry practitioners, academic researchers, and defect management specialists, who assessed the real-world importance of the risk factors based on actual defect cases encountered in the field. The third and final step applied the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) method to assess the relative importance of each risk factor based on the expert opinions collected during the FGI survey. The results of the AHP analysis were then integrated into the TOPSIS method to quantitatively evaluate the priorities of the identified risk factors. Furthermore, based on the TOPSIS scores, K-means clustering was conducted to group the defect types according to their shared characteristics. Based on these insights, quality management strategies for each project phase were then developed. Figure 3 illustrates these three steps.

Figure 3.

Assessment framework development.

4.2. Derivation of Defect Types and Causes

To ensure the reliability of this research, data were collected from authoritative sources that serve as benchmarks for quality certification and technical standards in Korea’s architectural planning, design, construction, and management fields. These sources included the Architectural Technical Guidelines I and II, published and reviewed by the Architectural Institute of Korea, which assess standards across various architectural fields; the LH Construction Specification, a codified system that aligns with the Korean National Construction Standards (KCS) and provides up-to-date construction standards; and the LH Smart Construction Handbook, a comprehensive guide covering construction-related laws, standards, materials, and methods. Based on data on the occurrence and types of defects in Korean multifamily housing up to 2018, a comprehensive analysis was conducted, encompassing various types of residential buildings. Specifically, the analyzed housing categories included special-purpose housing designed for vulnerable groups, such as individuals with disabilities and the elderly; economy class housing aimed at addressing the challenges of urban overpopulation and providing affordable solutions for residents displaced from substandard or emergency housing; and comfort housing such as private apartments for middle-class residents. Using these sources, the types and current statuses of defects in Korea were identified. Additionally, the causes of these defects were systematically analyzed, and quality management measures were examined based on MasterSpec, the standard specifications issued by the American Institute of Architects for the establishment of comprehensive quality standards in architectural projects. The International Organiztion for Standardization (ISO) 9001 [54] quality management systems and international standards for quality management systems were also referenced. Furthermore, the International Building Code, widely used in the United States and developed by the International Code Council as a standard for building safety and regulatory compliance, was analyzed to assess the defect causes and quality standards by defect type in the U.S.

Through the aforementioned literature sources, six major defect-prone categories were identified: PL windows, kitchen cabinetry, wallpaper, tiles, painting, and flooring. The primary causes of the major defects were categorized into design standards, materials and methods, construction, and quality management. Based on this categorization, the specific causes of each defect type within the six major defect-prone categories were detailed, and subjects for the FGI survey were selected accordingly.

4.3. Ensuring Validity of Analysis Subjects Using FGI

In this research, the FGI survey began by establishing topics and objectives, which included the causes and countermeasures for each defect type within the six major defect-prone categories, the appropriateness of the defect analysis items, and quality management considerations. Participants were selected from public institution employees directly or indirectly involved in multifamily housing construction, including site managers from construction companies, supervisors, and lead engineers. Eighteen experts, each with over 20 years of experience in the construction industry, were invited to conduct an in-depth review of the identified defect issues and propose improvement strategies. The breakdown of the FGI survey participants is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Focus group interview survey participant count.

The questionnaire for the FGI survey was designed to assess the appropriateness of the contents on the “causes and countermeasures for each defect type”, the “representativeness of defect types or occurrence locations”, the “suitability of the defect cause analysis items”, and the “key quality management factors”. Additionally, it included items on the “defect reduction and quality management criteria” for the six major defect-prone categories. The questionnaire was structured for use as AHP survey data, enabling the determination of the importance and prioritization of defects in multifamily housing. The preparation of the FGI questionnaire is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Sample questionnaire with defect cause analysis items.

Expert consultation was sought to validate the appropriateness of the items related to the selection of defect factors and the identification of causes in multifamily housing structures to incorporate the AHP survey. Each defect was thoroughly reviewed to verify specific items for defect prevention and key management targets, enabling an in-depth analysis of the major and frequently occurring defects in multifamily housing structures.

Based on the results of the FGI survey, expert validation was performed to ensure the relevance of the analyzed items. The identified defect types and detailed causal analysis items for the six major defect-prone categories are presented in Table 6 and Appendix A.

Table 6.

Subjects of the AHP analysis.

Before the FGI, the validity and appropriateness of the survey items were confirmed. The detailed structuring of the survey items enabled the collection of expert opinions on the specific types and causes of defects in multifamily housing, which were subsequently used as the AHP survey data.

4.4. Determining Defect Importance Using AHP Analysis

This research applied AHP analysis to overcome the limitations of traditional FGI survey results, which often rely on subjective expert opinions. This approach addresses these limitations by objectively quantifying the survey results and ensuring reliability through consistency verification [55].

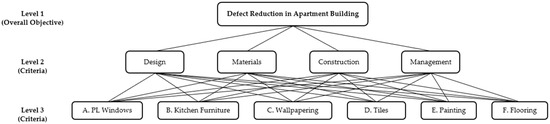

The AHP provides a methodology for the objective quantification of the importance assessments of field experts regarding defects, which is essential in conducting an importance analysis focused on defect reduction in multifamily housing structures. Additionally, the process of synthesizing weights through consistency verification and geometric mean calculations enhanced both the reliability and validity of the results. In the first step of the AHP method, the problem is defined, and a hierarchical structure is established to address it. Defects in multifamily housing buildings require the hierarchical structuring of complex factors, as they involve multiple considerations, including economic costs, the frequency of occurrence, and the severity of defects. Therefore, the top level was set with the ultimate goal of defect reduction in multifamily housing. Based on the defect factors identified in the in-depth analysis of the literature and the FGI survey results, the first level was categorized into four main criteria: design, construction, materials, and management. The second level was structured with six specific subcriteria: (a) PL windows, (b) kitchen furniture, (c) wallpaper, (d) tiles, (e) paint, and (f) flooring. This hierarchical structure allowed for a systematic analysis of the importance and frequency of each defect by logically decomposing the complex factors associated with multifamily housing defects, which are intertwined with various defect types and causes. The hierarchical structure established for multifamily housing defects is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Hierarchy setting for AHP analysis.

The process of deriving importance and priority in the AHP method involved AHP calculations based on surveys completed by experts on defects in multifamily housing. In this study, expert surveys were administered to professionals across various construction-related institutions, including supervision agencies, construction companies, and public organizations, to assess the importance of defects in multifamily housing using a field-focused approach. To address the limitations of data relying on subjective expert evaluations, pairwise comparisons and consistency checks were conducted using the AHP method. Based on these, the importance of the major and most frequently occurring defect categories in multifamily housing was calculated. A total of 163 experts participated in the survey. After excluding the responses of 93 experts with CR values greater than 0.1, the final analysis included the responses of 70 experts (as listed in Table 7) to derive the importance and priority rankings.

Table 7.

Summary of survey respondents.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Importance Analysis of Defects in the Six Major Defect-Prone Categories

The results of the AHP analysis for defects in the six major defect-prone categories revealed their importance rankings, as shown in Table 8. Specifically, these rankings are as follows: (1) PL windows (0.381), (2) kitchen cabinets (0.239), (3) tiles (0.124), (4) wallpaper (0.105), (5) flooring (0.102), and (6) paint (0.049).

Table 8.

Importance analysis of defects in the six major defect-prone categories.

The category “PL windows” (0.381) was identified as the highest-priority category and recognized as the most influential factor among the defects in the six major defect-prone categories. This is likely because defects in PL windows can lead to major functional issues, such as insulation failures, noise, condensation, and water leakage. Additionally, defects in PL windows, a frequently used component, can cause substantial inconvenience in daily life.

5.2. Cause Importance Analysis of Defects in the Six Major Defect-Prone Categories

5.2.1. Importance Analysis of Defects in PL Windows

The PL window defects were categorized into four items for the importance analysis: (A-1) frame/sash damage, (A-2) sash operation failure, (A-3) automatic handle malfunction, and (A-4) excessive gaps in the frame/sash. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Results of importance analysis for PL window defects.

The top-ranked item, (“A-1”) frame/sash damage, was identified as the most important, as damage to the frame or sash of a PL window can result in significant functional issues, such as insulation failure, noise infiltration, condensation, and water leakage.

5.2.2. Importance Analysis of Defects in Kitchen Furniture

Defects in kitchen furniture were classified into four categories for the importance analysis: (B-1) door/sink countertop damage, detachment, dents, and discoloration; (B-2) door misalignment; (B-3) poor door finish; and (B-4) drawer operation failure. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Results of importance analysis for kitchen furniture defects.

The top-ranked item, “(B-1) door/sink countertop damage, detachment, dents, discoloration”, was found to have the highest importance weight. This is attributed to frequent damage incurred during transport or handling due to negligence, as well as damage from insufficient protection management after installation, often caused by interference from other trades. Additionally, from the perspective of primary users, such as homemakers who frequently use kitchen furniture, defects in this category are highly visible and occur with a relatively high frequency, resulting in a considerably higher importance weight compared to the items ranked second to fourth.

5.2.3. Importance Analysis of Wallpaper Defects

Wallpaper defects were classified into four categories for the importance analysis: (C-1) stains, damage, dents, and discoloration; (C-2) uneven surface and peeling; (C-3) wallpaper tearing; and (C-4) spots and mold. The results of this analysis are listed in Table 11.

Table 11.

Results of importance analysis for wallpaper defects.

The causes for the top-ranked item, “(C-4) spots and mold”, were primarily attributed to condensation and humidity resulting from inadequate temperature and humidity control during installation or unfavorable living conditions. This defect received the highest importance weighting because it directly affected the health of the residents.

5.2.4. Importance Analysis of Tile Defects

Tile defects were classified into four categories for the importance analysis: (D-1) insufficient grout filling and stains; (D-2) damage and cracks; (D-3) peeling and detachment; and (D-4) esthetic deterioration due to excessive drilling. Table 12 presents the results of this analysis.

Table 12.

Results of importance analysis for tile defects.

The causes for the top-ranked item, “(D-2) damage and cracks”, were primarily attributed to inadequate crack treatment on the substrate, the absence of expansion joints, or the strength of the grout exceeding that of the tile material. This defect received the highest importance weight due to its potential to cause functional inconvenience and the risk of further damage.

5.2.5. Importance Analysis of Paint Defects

Paint defects were classified into four categories for the importance analysis: (E-1) discoloration and stains; (E-2) peeling; (E-3) efflorescence; and (E-4) pinholes. Table 13 presents the results of this analysis.

Table 13.

Results of importance analysis for paint defects.

The causes for the top-ranked item, “(E-1) discoloration and stains”, were primarily attributed to poor construction practices, the use of substandard materials, the inadequate solvent power of thinner paints, the mixing of differently colored paints during tinting, damage from other trades, and insufficient protection management after work completion. This defect was identified as having the highest importance weight due to its high frequency among paint defects.

5.2.6. Importance Analysis of Flooring Defects

The flooring defects were classified into four categories for the importance analysis: (F-1) dents, stains, and edge chipping; (F-2) peeling and delamination; (F-3) discoloration and fading; and (F-4) level differences. Table 14 presents the results of this analysis.

Table 14.

Results of importance analysis for flooring defects.

The causes for the top-ranked item, “(F-2) peeling and delamination”, were primarily attributed to the poor cleaning and leveling of the substrate, as well as uneven adhesive applications. This defect received the highest importance weighting due to its tendency to cause noise and inconvenience in daily life and the need for repair.

5.3. Importance Analysis of Causes for Defects in the Six Major Defect-Prone Categories

5.3.1. Results of Relative Importance of Cause Items for PL Window Defects

The cause items for PL window defects were classified into seven categories for the importance analysis: (A-1) design quality standards; (A-2) appropriate materials, manufacturing/production; (A-3) compliance with the working environment (temperature/humidity); (A-4) surface preparation; (A-5) construction quality control; (A-6) skilled labor; and (A-7) storage/protection management and interference from other trades. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 15.

Table 15.

Importance analysis results for causes of PL window defects.

The top-ranked item, “(A-5) construction quality control”, was identified as the most important because the main defect types in PL windows, such as frame/sash damage, sash operation failure, automatic handle malfunction, and excessive gaps in the frame/sash, are primarily caused by inadequate construction quality control, including installation negligence, poor construction precision, improper sealing around the frame, and substandard fixing hardware.

5.3.2. Relative Importance Results of Cause Items for Kitchen Furniture Defects

The cause items for kitchen furniture defects were classified into seven categories for the importance analysis: (B-1) design quality standards; (B-2) appropriate materials, manufacturing/production; (B-3) compliance with the working environment (temperature/humidity); (B-4) surface preparation; (B-5) construction quality control; (B-6) skilled labor; and (B-7) storage/protection management and interference from other trades. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 16.

Table 16.

Importance analysis results for causes of kitchen furniture defects.

The top-ranked item, “(B-5) construction quality control”, was identified as the most important as the primary causes of key defect types in kitchen cabinetry, such as damage, dents, door misalignment, poor finishing, and drawer operation failures, are largely due to inadequate quality control, including installation negligence and a lack of precision. Therefore, this factor was rated the highest in importance.

5.3.3. Relative Importance Results of Cause Items for Wallpaper Defects

The cause items for wallpaper defects were classified into seven categories for the importance analysis: (C-1) design quality standards; (C-2) appropriate materials, manufacturing/production; (C-3) compliance with the working environment (temperature/humidity); (C-4) surface preparation; (C-5) construction quality control; (C-6) skilled labor; and (C-7) storage/protection management and interference from other traders. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 17.

Table 17.

Importance analysis results for causes of wallpaper defects.

The top-ranked item, “(C-6) skilled labor”, was identified as the most important as the primary causes of key wallpaper defects, such as stains, damage, dents, and discoloration, are largely due to installation negligence and insufficient skill levels. Ensuring the availability of skilled wallpaper installers was thus selected as the most crucial factor for defect reduction and quality management.

5.3.4. Results of Relative Importance of Cause Items for Tile Defects

The cause items for tile defects were classified into seven categories for the importance analysis: (D-1) design quality standards; (D-2) appropriate materials, manufacturing/production; (D-3) compliance with the working environment (temperature/humidity); (D-4) surface preparation; (D-5) construction quality control; (D-6) skilled labor; and (D-7) storage/protection management and interference from other traders The results of this analysis are presented in Table 18.

Table 18.

Importance analysis results for causes of tile defects.

The top-ranked item, “(D-5) construction quality control”, was found to be the most important factor as the major types of tile defects, such as insufficient grout filling and staining, damage, cracks, peeling, detachment, and esthetic deterioration due to excessive drilling, are largely influenced by factors such as installation negligence, a lack of precision, non-compliance with mortar mix ratios, the absence of expansion joints, insufficient backfilling, and an inadequate mortar thickness. These issues were deemed to have a major impact due to insufficient construction quality control.

5.3.5. Relative Importance Results of Cause Items for Paint Defects

The cause items for paint defects were classified into seven categories for the importance analysis: (E-1) design quality standards; (E-2) appropriate materials, manufacturing/production; (E-3) compliance with the working environment (temperature/humidity); (E-4) surface preparation; (E-5) construction quality control; (E-6) skilled labor; and (E-7) storage/protection management and interference from other traders. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 19.

Table 19.

Importance analysis results for causes of paint defects.

The top-ranked item, “(E-6) skilled labor”, was identified as the most important as the primary causes of major paint defect types, such as discoloration, staining, peeling, delamination, cracks, efflorescence, and pinholes, are largely attributed to insufficient skill levels, installation negligence, and a lack of precision in application. Therefore, painting performed by highly skilled professionals was determined to be the most critical factor.

5.3.6. Relative Importance Results of Cause Items for Flooring Defects

The cause items for flooring defects were classified into seven categories for the importance analysis: (F-1) design quality standards; (F-2) appropriate materials and manufacturing/production; (F-3) compliance with the working environment (temperature/humidity); (F-4) surface preparation; (F-5) construction quality control; (F-6) skilled labor; and (F-7) storage/protection management and interference from other traders. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 20.

Table 20.

Importance analysis results for causes of flooring defects.

The top-ranked item, “(F-6) skilled labor”, was identified as the most important factor as the primary flooring defect types, such as dents, stains, edge chipping, peeling, delamination, discoloration, and level differences, are largely attributed to installation negligence and insufficient skill levels. Therefore, flooring installation by experienced, skilled workers was selected as the most crucial factor for defect reduction and quality management.

Based on the compiled AHP analysis results, the importance rankings of the defects in the six major defect-prone categories were identified as follows: (1) PL windows (0.381), (2) kitchen furniture (0.239), (3) tiles (0.124), (4) wallpapers (0.105), (5) flooring (0.102), and (6) paint (0.049). Additionally, the cause items for the defect types in the six major defect-prone categories comprised 168 items (six categories × four defect types × seven defect cause analysis items). Based on the AHP survey results, the highest importance weight was assigned to “PL windows—frame/sash damage—construction quality control” (2.908), while the lowest was for “paint—pinholes—design quality standards” (0.044). The importance analysis results for the defect causes based on the type within the six major defect-prone categories are presented in Table 21. In the AHP analysis process for the defect types and causes, only data with a consistency index (CI) value below 0.1, indicating an appropriate level of consistency, were utilized. These findings provide insights into the importance of defects by type and cause, thereby supporting the planning of quality management priorities and strategies.

Table 21.

Comprehensive importance analysis by defect type for the six major defect-prone categories.

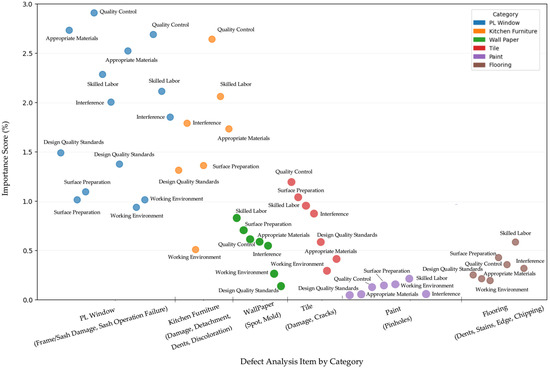

Figure 5 compares the importance scores by selecting one representative defect type from each of the six categories. For PL windows, which have a large distribution of high importance scores, two defect types are shown in the graph. As illustrated, high-scoring items are predominantly associated with defects in PL windows and kitchen furniture, while lower-scoring items mainly pertain to defects in paint and flooring. This enables the prioritization and selection of key management items for each category when planning quality control measures for defect management in multifamily housing.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of importance scores by defect type.

The results of this research emphasize the importance of adopting a prioritized approach to defect management to enhance the quality in multifamily housing. By evaluating the defect significance across six primary defect-prone categories, we identified critical areas, such as PL windows and kitchen cabinetry, that require focused quality management efforts. Implementing a quality management improvement plan will enable construction companies to allocate resources more effectively to high-priority defect areas, potentially decreasing the defect frequency and enhancing resident satisfaction. Integrating AHP-derived defect importance ratings into quality control protocols allows companies to set systematic priorities across project phases, from the initial design to construction and maintenance.

Moreover, these prioritized areas provide a foundation for the strengthening of onsite inspection and maintenance standards. Specific guidelines tailored to high-importance defects can increase the responsiveness among construction teams and quality assurance managers, facilitating defect reduction through preventive measures. In summary, the results of this analysis support the selection of quality management priority items based on identified priorities, thereby preventing the inefficient allocation of human and material resources. This approach underpins economically efficient quality management strategies, aligns quality management efforts with resident needs, and optimizes defect management resources across multifamily housing projects.

5.3.7. Clustering Grouping Based on TOPSIS Analysis

Based on the results of the AHP analysis, the relative priorities among the defect types were quantitatively evaluated, and the TOPSIS and K-means clustering techniques were combined to group the defect types. The analysis classified the defect types into three main clusters according to their TOPSIS scores. The first cluster, referred to as the “low-priority group”, included defect types with relatively low TOPSIS scores, which do not require immediate corrective actions. The second cluster, the “medium-priority group”, comprised defect types with moderate TOPSIS scores, requiring periodic monitoring and limited resource allocation. Lastly, the third cluster, the “high-priority management group”, included defect types with high TOPSIS scores, designated as critical priorities for quality improvement, necessitating immediate action and focused resource investment.

The classification of each group reflects the primary causes and relative importance of the defect types, providing essential insights for the prioritization of resource allocation and improvement efforts. Through this approach, this study offers data-driven insights that contribute to the efficient management of defect types and the development of quality improvement strategies. Figure 6 and Table 22 illustrate the clustering results based on the TOPSIS scores, with the elbow method determining that the optimal number of clusters is three.

Figure 6.

Elbow method for TOPSIS-based clustering.

Table 22.

High-priority group.

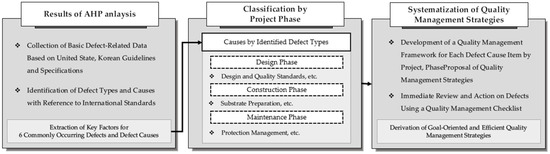

5.3.8. Strategies for Systematization of Quality Management by Project Phase

Defects in buildings are challenging to accurately identify and address due to the complex nature of construction projects, which involve the integration of various trades. However, when the defect cause items are derived from international standards and the specifications of Korea and the United States, they can be classified according to the general phases of design, construction, and maintenance. The design phase includes factors such as appropriate materials and manufacturing, as well as design and quality standards. In the construction phase, the items include construction quality control, skilled labor proficiency, substrate preparation, and compliance with work environment conditions. Lastly, the maintenance phase comprises protection management and the impact of interference between trades.

Table 23 summarizes the defect types and their causes by project phase based on the AHP analysis results. It includes the prioritization of the defect types and the ranking of the cause items, providing a comprehensive overview of the defect causes and classifications across the design, construction, and maintenance stages.

Table 23.

Defect cause analysis items for the six most common defect categories classified by project phase.

Table 24 presents a quality management checklist and key quality management measures for each defect cause analysis item classified by project phase. This research offers a comprehensive set of quality management strategies based on the defect types and causes, with a focus on the priority items identified through the AHP analysis results. These strategies enable the development of systematic and goal-oriented quality management approaches that maximize cost efficiency by allocating resources to high-priority defect types and causes. Furthermore, this research designs a quality management framework that leverages international standards, ensuring flexible applicability across diverse regional characteristics and construction practices. This framework references construction standards from South Korea and the United States, allowing quality management strategies to be adapted to various construction environments. By concentrating management resources on high-priority defects and their causes, this approach effectively and economically reduces significant defects that inconvenience residents. It benefits both construction professionals and occupants by preventing inefficient resource allocation and prioritizing actions for critical management items, thereby improving the overall quality of multifamily housing while achieving cost savings. Additionally, the introduction of a quality management checklist facilitates a more systematic and streamlined defect management process. The checklist subdivides the management items by defect type and cause, enabling immediate onsite review and action to enhance the efficiency of quality management efforts. Through this approach, managers can clearly identify priority items, continuously evaluate the achievement of management objectives, and maximize the tangible outcomes of defect reduction initiatives. The process of developing systematic quality management strategies by project phase, based on the defect types selected in consideration of various national construction standards and the AHP results, is illustrated in Figure 7.

Table 24.

Quality management framework and key quality management items for the six most common defect categories.

Figure 7.

Process of developing systematic quality management strategies by project phase.

6. Conclusions

Although multifamily housing is becoming increasingly common worldwide, the number of defects associated with these structures is rising, highlighting the importance of effective defect management and prevention. Defects in multifamily housing impact various aspects, including economic, structural, and environmental factors. The complexity of the defect types and their causes makes defect management a challenging task.

Furthermore, major defects in multifamily housing can lead to secondary defects, further complicating defect management and potentially compromising the convenience and safety of residents’ living environments.

This research aimed to identify the types, current statuses, and causes of defects in multifamily housing, prioritized each factor, and developed quality management strategies for each project phase based on these findings. By analyzing various data related to defects and insights from construction industry experts, an FGI survey was conducted to select systematic, field-oriented analysis items. The AHP analysis categorized the factors not only by defect category but also by item, focusing on defect types and causes. This allowed for the assignment of weights to each item and the calculation of overall importance scores, resulting in a more effective and detailed field-oriented analysis. The 10 most influential factors were identified as key items for defect management, including PL windows, kitchen furniture, wallpaper, and paint. These ten items derived from the AHP analysis serve as focal points for defect management, supporting defect reduction and quality control in the six major defect categories.

The TOPSIS method was employed to quantitatively evaluate the results of the AHP analysis, and K-means clustering was applied based on the TOPSIS scores to visually identify the key focus areas for quality management. This process further enhanced the insights derived from the AHP analysis, making them more intuitive and actionable.

Additionally, based on the six primary defect categories, the importance of the defect cause analysis items for each defect type was evaluated according to their significance. As presented in Table 24, the identified priorities were used to classify the causes of each defect into project phases—design, construction, and maintenance—and corresponding quality management strategies were developed. Furthermore, during the process of selecting the analysis items and systematizing quality management for each defect type, quality management strategies and checklists applicable across various countries were proposed. These strategies reference international standards, as well as specifications from the United States and Korea (e.g., KCS, IBC), ensuring broader applicability. These efforts are expected to contribute to reducing defects in multifamily housing and improving long-term quality management practices. Proper quality management at each project phase can effectively manage and reduce defects, preventing the occurrence of secondary defects. Although this research conducted extensive literature reviews, FGI surveys, and AHP analyses to derive efficient priority items for defect management with the maximum objectivity, it was limited by the inherent subjectivity of the expert opinions.

This research employed the AHP to systematically analyze and prioritize major defect types in multifamily residential buildings. By deriving defect management priorities, it formulated actionable strategies for quality management and provides practical guidance for policymakers and industry participants. The use of historical data ensured an objective and comprehensive analysis, free from biases associated with specific timeframes while enabling the identification of recurring defect patterns for long-term quality control improvements.

Furthermore, this research differentiates itself through its combination of expert-driven insights from FGI with the AHP. This approach ensured both scholarly robustness and practical applicability, offering enhanced guidance for the optimization of resource allocation and defect prevention strategies. Future research could explore the integration of AI-driven defect prediction models with the proposed framework. Such advancements could facilitate real-time monitoring and predictive analytics, revolutionizing quality management processes in the construction industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.K. and N.K.; Formal analysis: D.K. and E.L.; Investigation: D.K. and Y.A.; Methodology: E.L. and N.K.; Supervision: Y.A.; Visualization: D.K. and E.L.; Writing—original draft: D.K. and N.K.; Writing—review and editing: D.K., E.L., Y.A. and N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korean government (MOTIE) (20227200000010, Building Crucial Infrastructure for Demonstration Complex Regarding Distributed Renewable Energy System).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00344868) and the research fund of Hanyang University (HY-2024-3734).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

FGI survey result analysis.

Table A1.

FGI survey result analysis.

| Expert | Summary of Consultation Content |

|---|---|

| A | · Issues such as facade window operation failure and loose fixation of extended double windows require review from the design stage · Adjustment of defect cause analysis items (appropriate materials and factory inspection—preceding and subsequent trade management—sealing and fastening) |

| B | · An I-beam support is required to prevent sagging when the window height exceeds 1.8 M · To prevent sagging of the bedroom sliding door frame, ensure support wood installation at the base during flooring work |

| C | · For precise work around drilled areas, thoroughly clean the backs of drilled sections after waterproofing · Apply mortar adhesion enhancer to structural surfaces before tiling to prevent peeling and delamination defects |

| D | · Ensure strict management to avoid contamination and damage caused by subsequent trades after painting is completed · Painting should be conducted only after the surface is thoroughly dried and cleaned |

| E | · Poor door finish quality often arises from color discrepancies between manufacturers; standardize products from the same manufacturer and thoroughly inspect color before installation · Adjust defect cause analysis items (design completion—factory inspection—appropriate construction period—interference from other trades) |

| F | · Tearing of wallpaper is common around electrical outlets, during removal of protective sheets, or with rapid ventilation inside units |

| G | · When cracks occur in floor mortar, it can lead to flooring delamination; ensure mortar surface crack repair and thorough cleaning before flooring installation |

| H | · To prevent cracking, it is essential to maintain rebar spacing and cover thickness, ensure quality control of ready-mix concrete, and conduct thorough vibration compaction. To reduce finish work defects, securing sufficient time for finish construction is crucial |

| I | · To prevent and manage water leakages, it is advisable to ensure proper roof slope installation and install drainage boards on the interiors of the external walls of underground parking areas |

| J | · Selecting key quality control items for each construction phase and managing them through checklists is required, along with identifying high-frequency defect items and verifying their implementation |

| K | · Strengthen measures at the design stage by supplementing defect cause analysis and preventive measures during design · Efforts to proactively prevent defects should include discovering and utilizing smart inspection equipment |

| L | · Crack occurrence is often due to improper rebar placement, drying shrinkage, lack of props, poor curing, or exceeding design loads (e.g., placing heavy equipment), requiring diligent management |

| M | · To prevent recurring defects, thorough management of frequently occurring defect records, procurement of supply materials, fostering specialized construction companies, and establishing cooperative systems are important |

| N | · For water leakage prevention, ensure proper slope installation, apply hydrophilic sealing materials at jointed areas, and install drainage boards on the exterior walls of underground parking areas to facilitate guided drainage |

| O | · Classify defect causes into criteria, materials, construction, and quality management aspects and present these as quantitative data to set and manage defect and quality management priorities |

| P | · Consider establishing major defect prioritization based on the level of inconvenience or frequency of complaints from consumers · A comprehensive analysis of defect causes, corrective actions, duration of corrective actions, and post-correction satisfaction is necessary |

| Q | · Classify inter-floor noise into light- and heavy-impact sounds and establish causes and countermeasures accordingly · Separate cracking causes into those related to joint areas and those due to work loads and establish countermeasures for each |

Table A2.

Partial example of AHP survey.

Table A2.

Partial example of AHP survey.

| Item A | Very Important | Equal | Very Important | Item B | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design, quality standards | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Suitable materials and production |

| Design, quality standards | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Working conditions (temperature and humidity) |

| Design, quality standards | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Substrate preparation |

| Design, quality standards | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Construction quality control |

| Design, quality standards | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Worker skill level |

| Design, quality standards | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Interference between trades |

| Suitable materials and production | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Working conditions (temperature and humidity) |

| Suitable materials and production | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Substrate preparation |

| Suitable materials and production | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Construction quality control |

| Suitable materials and production | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Worker skill level |

| Suitable materials and production | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Interference between trades |

| Working conditions (temperature and humidity) | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Substrate preparation |

| Working conditions (temperature and humidity) | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Construction quality control |

| Working conditions (temperature and humidity) | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Worker skill level |

| Working conditions (temperature and humidity) | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Interference between trades |

| Substrate preparation | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Construction quality control |

| Substrate preparation | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Worker skill level |

| Substrate preparation | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Interference between trades |

| Construction quality control | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Worker skill level |

| Construction quality control | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Interference between trades |

| Worker skill level | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | Interference between trades |

Table A3.

Quality management checklist.

Table A3.

Quality management checklist.

| Category | Defect Reduction and Quality Management Checklist | Inspection Phase | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Construction | |||

| Design Quality Standards Management | Verify the appropriate use and storage of painting materials onsite according to LH standards. | |||

| Is the quality of the urethane sealing and the substrate, which are concealed by painting, appropriate? | ||||

| Confirm the procedure for front door frames, including galvanizing → epoxy primer application. | ||||

| Verify the proper quality application of elastic putty for external floor joint areas. | ||||

| Check whether painting has been completed on concealed areas beneath kitchen furniture during painting works. | ||||

| Substrate Preparation | Verify whether progressive structural cracks in the painting substrate have been appropriately addressed. | |||

| Assess the condition of the painting substrate (e.g., removal of foreign materials, surface irregularities, and damaged areas). | ||||

| Evaluate the quality or omissions of preceding work on substrates for balconies and interior painting. | ||||

| Verify the quality of the substrate and check for lifting or detachment of CRC board PVC joints in balconies and utility rooms. | ||||

| Compliance with Work Environment(Temperature and Humidity) | Confirm weather conditions (humidity ≤ 85%, temperature ≥ 5 °C). | |||

| Identify potential quality degradation factors due to contamination, damage, excessive humidity, or low temperatures on painted surfaces. | ||||

| Check for quality degradation issues, such as peeling, caused by low temperatures during winter exterior painting. | ||||

| Ensure construction management to prevent condensation and moisture damage during the rainy season. | ||||

| Construction Quality Control | Verify the proper quality application of elastic putty for external floor joint areas. | |||

| Assess for potential quality degradation factors in external water-based primer paint. | ||||

| Check for quality degradation issues such as cracks or discoloration following the application of the external water-based topcoat. | ||||

| Evaluate the suitability of materials and quality of anti-graffiti primer and topcoat. | ||||

| Protection Management | Inspect the protective measures taken before painting. | |||

| Confirm the implementation of appropriate management plans to prevent damage after the completion of painting works. | ||||

| Check the protection status after painting, particularly for landscaping trees and facilities. | ||||

| Ensure there is no contamination or damage caused by soil or traffic after painting works. | ||||

References

- Household Characteristics|National Multifamily Housing Council. Available online: https://www.nmhc.org/research-insight/quick-facts-figures/quick-facts-resident-demographics/household-characteristics/ (accessed on 13 July 2019).

- America’s Rental Housing 2022|Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. Available online: www.jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Characteristics of Apartment Stock|National Multifamily Housing Council. Available online: https://www.nmhc.org/research-insight/quick-facts-figures/quick-facts-apartment-stock/characteristics-of-apartment-stock/ (accessed on 24 July 2019).

- People Living in Apartments|Landgeist. Available online: https://landgeist.com/2021/08/20/people-living-in-apartments/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Most Common Type of Home in Europe|Landgeist. Available online: https://landgeist.com/2023/07/01/most-common-type-of-home-in-europe/ (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Jonhston, N.; Reid, S. An Examination of Building Defects in Residential Multi-Owned Properties; DEAKIN University: Waurn Ponds, VIC, Australia; Griffith University: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://www.bellsbic.com.au/building-defects-the-extent/ (accessed on 30 June 2019).

- NSW Government Survey Finds More than Half of Newly Registered Apartments Have Had at Least One Serious Defect|NSW. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-01-24/more-than-half-newly-registered-apartments-defects-nsw/103379978 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- New Home Review. Annual Report on Defects in New-Build Homes: Findings from 2017–2018 Survey. 2018. Available online: https://phpdonline.co.uk/news/9-10-new-build-homes-defects-according-new-home-reviews-annual-report/ (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- National Assembly Land, Infrastructure and Transport Committee. 2016 National Audit Report; National Assembly Land, Infrastructure and Transport Committee: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016.

- Kim, J.H.; Go, S.S. Evaluation of defective risk for the finishing work of apartment house. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 13, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.J.; Shin, M.J. Improvement Measures for the Defect Determination and the Application of Repair Method for Interlayer Cracks in Apartment Houses. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 23, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, M.H. A Method for Selecting Principal Items of Quality Management through the Defect Analysis in the Construction Process. J. Korean Inst. Archit. 1996, 12, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Mésároš, P.; Chellappa, V.; Spišáková, M.; Kaleja, P.; Špak, M. Factors infuencing defects in residential buildings. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2024, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Son, K.Y. An Examination of a Risk Assessment Method and Analysis of Defect Types of Apartment Finishing Works. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2024, 24, 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, Y.C.; Bang, H.S.; Kim, O.K. Analysis of the Major Works Causing Secondary Defects in Apartment Building Construction. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2021, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.S. Defect Reduction Method of Apartment Housing Accord to Change of Defect Management Process by Each Work Process. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gyeonggi, Suwon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, D.S. Building Pathology: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Min, Y.G.; Park, I.S.; Cho, H.H. Analysis of Importance by Defect Type in Apartment Construction. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2020, 20, 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, N.H.; Song, K.S.; Ahn, Y.H.; Park, M.S.; Jang, Y.J. Maintenance cost prediction for aging residential buildings based on case-based reasoning and genetic algorithm. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 28, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Ji, S.H.; Ahn, S.J.; Park, M.S.; Lee, H.S.; Kwon, N.H.; Kim, Y. Performance evaluation of normalization-based CBR models for improving construction cost estimation. Autom. Constr. 2020, 119, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, N.H.; Ahn, Y.H.; Son, B.S.; Moon, H.S. Developing a machine learning-based building repair time estimation model considering weight assigning methods. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 43, 102627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, N.H.; Song, K.S.; Park, M.S.; Jang, Y.J.; Yoon, I.S.; Ahn, Y.H. Preliminary service life estimation model for MEP components using case-based reasoning and genetic algorithm. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.S.; Ahn, J.; Ahn, Y.H.; Park, M.S.; Kwon, N.H. Reduction and transformation of energy use data for end-user group categorization in dormitory buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, R.; Meshram, K. Investigation of Building Failure Using Structural Forensic Engineering. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 1876–1878. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Ahn, Y.H.; Lee, S.H. LDA-Based Model for Defect Management in Residential Buildings. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milion, R.N.; Alves, T.C.L.; Paliari, J.C. Impacts of defects on customer satisfaction in residential buildings. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Boston, MA, USA, 20–22 July 2016; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ifran Che-Ani, A.; Samsul Mohd Tazilan, A.; Afizi Kosman, K. The development of a condition survey protocol matrix. Struct. Surv. 2011, 29, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatlin, F. Identifying and managing design and construction defects. Constr. Insight Hindsight 2013, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, C.; de Brito, J.; Silvestre, J.D. Harmonised classification of the causes of defects in a global inspection system: Proposed methodology and analysis of fieldwork data. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhwezi, L.; Twinamatsiko, D.; Acai, J. Mitigation of Building Failures in Uganda’s Construction Industry: A Case Study of Greater Bushenyi District. Int. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 9, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.S.; Wen, K.H. Building defects: Possible solution for poor construction workmanship. J. Build. Perform. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Shittu, A.; Adamu, A.; Mohammed, A.; Suleiman, B.; Isa, R.; Ibrahim, K.; Shehu, M. Appraisal of Building Defects Due To Poor Workmanship in Public Building Projects in Minna, Nigeria. IOSR J. Eng. 2013, 3, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, N.A.; Mydin, M.A. Poor Workmanship in Construction of Low Cost Housing. Analele Univ. ‘Eftimie Murgu’ 2014, 21, 300. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bossche, N.; Blommaert, A.; Daniotti, B. The impact of demographical, geographical and climatological factors on building defects in Belgium. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2023, 41, 549–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.E. Assessment of Causes of Construction Building Defects in Debre Birhan University, North Showa, Amhara, Ethiopia. Am. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2019, 7, 152–156. [Google Scholar]