Abstract

In this study, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) was substituted for 10%, 20%, and 30% of the sand volume in concrete. Compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strength tests were applied to the concrete samples and stress–strain graphs were obtained. It was observed that PET substitution caused a decrease in the mechanical properties of the concrete. For this reason, the concrete with the best PET substitution rate (10%) was reinforced by wrapping it with carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) and glass fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP), and the same experiments were repeated. It was observed that a 10% PET substitution reduced the strength of the reference concrete by about 6%. However, wrapping the PET-substituted concrete with CFRP and GFRP increased the strength by about 1.9 and 1.5 times, respectively, surpassing that of the reference sample. In addition, this study provides a comprehensive database by bringing together experimental data from studies in which PET was used as a substitute by volume or weight instead of fine aggregate in concrete. The models proposed in this study, along with previous models, were tested for applicability. Similarly, the model suggestions in the literature for fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP)-confined concrete were tested with the experimental data in this study, and their suitability for PET-substituted concrete was discussed.

1. Introduction

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is a polymer of great importance among the world’s plastics. Its thermoplastic recyclability makes it the first choice for various applications [1,2]. PET, a polyester plastic, is one of the most used packaging materials for beverages. Due to its excellent transparency, light weight, gas and water barrier properties, impact resistance, UV resistance, and unbreakability, the production and use of PET bottles for beverage packaging has continuously increased worldwide [3]. With this increase in production and use, recycling solutions for PET began to be produced. PET is seen as one of the plastic types with the highest recycling rate today [4,5,6,7,8].

PET can be recycled in the construction industry as well as in the plastics industry. Using recycled plastics such as PET instead of aggregates in concrete is seen as being able to contribute to environmental protection and sustainable development [9]. It is thought that the use of PET in concrete as a partial or complete replacement for natural aggregates can protect natural aggregate resources [10]. For this purpose, there are many studies that have examined various properties of concrete by using PET as a fine aggregate replacement in concrete [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

In another study [30], an experimental investigation was conducted in which crushed PET bottles were used as both fine and coarse aggregates in concrete at replacement levels of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% by weight. The study examined various properties of the concrete containing PET waste, including compressive strength, impact resistance, and energy absorption capacity. Additionally, the behavior of PET-substituted concrete under high temperatures of 300 °C and 600 °C was also evaluated. The results indicated that concrete with PET aggregates exhibited lower compressive strength. However, it was noted that PET-substituted concrete demonstrated improved resistance to impact loading compared to the control concrete.

In a study [31], polyethylene terephthalate (PET) was utilized as a partial replacement by weight for sand at substitution levels of 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50%. The concrete was cast to evaluate the behavior of both the fresh and hardened states. The experimental results indicated a reduction in unit weight and deterioration in the mechanical properties of the concrete. Furthermore, PET waste was shown to be suitable for disposal at specific replacement rates, suggesting its potential for effective application in industrial contexts.

Some previous studies [15,17,19,31,32,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] on PET substitution in concrete have suggested models to predict the mechanical properties of concrete. In one study [32], researchers proposed a model showing that the percentage of PET replacement influences the compressive and tensile strengths of concrete. The compressive strength model suggested by ref. [32] is given in Equation (1), and the tensile strength model is given in Equation (2). In Equations (1) and (2), represents the compressive strength of the PET-substituted samples, represents the tensile strength of the PET-substituted samples, and represents the PET substitution percentage.

Some researchers [17,32] reported that the tensile and flexural strengths of PET-substituted concrete depend on the compressive strength. The tensile strength model proposed in ref. [32] is given in Equation (3) and the flexural strength model proposed in another study [17] is given in Equation (4). In Equations (3) and (4), represents the compressive strength of the PET-substituted samples, represents the tensile strength of the PET-substituted samples, and represents the flexural strength of the PET-substituted samples.

When the study results in the literature were examined, it was seen that the use of PET generally causes a decrease in the mechanical properties of concrete. It is thought that strengthening methods can be used to compensate for the possible decrease in mechanical properties due to the use of PET. In a study [43], it was stated that wrapping PET-substituted concrete with carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) could be one of these methods.

A frequently used technique to strengthen existing reinforced concrete structures is the use of fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) systems. It is clearly understood that lateral confinement of concrete can significantly increase its strength and ductility. With the introduction of FRP composites into the construction industry, the use of FRP as a wrapping material has attracted great attention [44]. The main advantage of FRP systems is that FRP materials have low mass and high tensile capacity and can provide greater durability when installed properly [45,46]. FRP is widely used in the construction of new structures and rehabilitation of old structures due to its non-corrosive properties and high strength/weight ratios [47,48]. The majority of studies on FRP wrapping of concrete to date have used CFRP and GFRP [49].

In many studies [50,51,52,53] involving FRP wrapping in concrete, the positive effect of FRP on the concrete behavior has been highlighted, and various model suggestions have been proposed. Details of the previous model suggestions regarding FRP wrapping are provided in Section 3.2.

In this study, sand in concrete was partially replaced with PET in order to protect natural resources and recycle PET. The results and models of similar studies in the literature were brought together and the connections between the experimental results were interpreted. We tried to increase the mechanical properties of concrete by using CFRP and GFRP. Similarly, an evaluation was made with studies in the literature.

2. Experimental Study

2.1. Materials

CEM I 42.5 R Portland cement (Marmara Cimento, Duzce, Turkey), produced in accordance with the EN 197-1 [54] standard, was used in the concrete production. The chemical and physical properties of the cement are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cement properties.

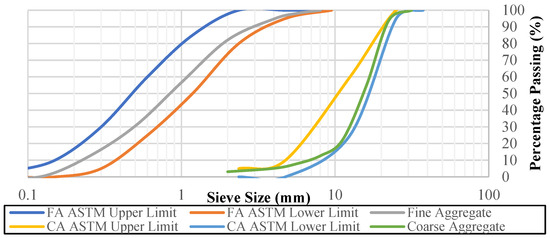

A sieve analysis was carried out separately for the coarse aggregate (gravel) and fine aggregate (sand) in accordance with the EN 933-1 [55] standard. The grading curves obtained from the sieve analysis are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Grading curves of aggregates.

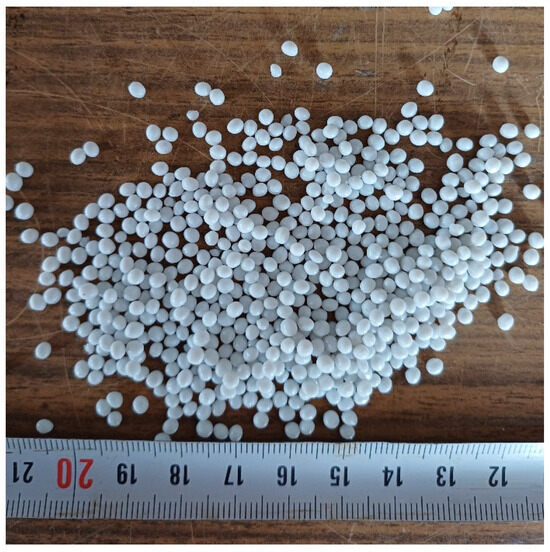

The PET granules used in the study were supplied by a plastic recycling company in Turkey during the recycling process. An image of the PET granules is given in Figure 2. The properties of the PET granules and aggregates are given in Table 2.

Figure 2.

PET granules.

Table 2.

Properties of aggregates and PET granules.

CFRP and GFRP were supplied for wrapping around the concrete samples. The FRP properties are given in Table 3 and visuals are given in Figure 3.

Table 3.

CFRP and GFRP properties.

Figure 3.

FRP types: (a) CFRP, (b) GFRP.

Epoxy was used to bond the FRP and concrete together and was maintained for 7 days to reach full strength. The epoxy’s properties are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Epoxy properties.

2.2. Concrete Sample Mix Design and Naming

Concrete production was carried out with the help of a concrete mixing machine. In all samples, the amounts of water, cement, and coarse aggregate were kept constant. The water/cement ratio was determined as 0.5. In samples using PET material, the substitution process was carried out as 10%, 20%, and 30% of the sand by volume. In the samples with FRP wrapping, after the 28-day curing pool process, epoxy was applied around the concrete and the FRP-wrapping process was carried out.

The sample names for the tests followed specific conventions: “CS” for compressive strength, “STS” for splitting tensile, and “FS” for flexural strength. The samples containing PET granules had “PET” in their names, while reference samples without PET were labeled with “R”. The substitution percentages were also included. Samples wrapped in carbon FRP were named with “CFRP”, and those with glass FRP were labeled “GFRP”. Table 5 lists the characteristics and naming details of the samples.

Table 5.

Concrete samples.

2.3. Methods

The concrete was mixed in a concrete mixing machine, then transferred to the test funnel for a slump test. The concrete was transferred in two stages. After filling half of the funnel, the filling process was paused, and the test rod was dipped into the concrete 25 times. After this, the funnel was completely filled with concrete. After filling was completed, the test rod was dipped into the concrete 25 more times. The upper level of the funnel was leveled off, and the funnel was lifted to release the concrete. The released concrete collapsed at varying heights. The difference between the upper level of the funnel and the upper level of the concrete determined the slump value.

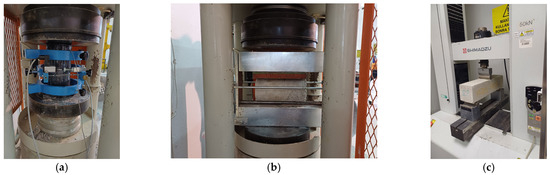

Cylindrical samples, each 10 cm in diameter and 20 cm in height, were created for the compressive strength and splitting tensile tests. Samples with 10 × 10 cm cross-sectional dimensions and 40 cm in length were produced for the flexural strength tests. While creating the reference concrete samples, 25 MPa was determined as the target strength. All samples were kept in the curing pool for 28 days after they were produced. The samples coming out of the curing pool were dried and weighed and their densities were found. The compressive strength and splitting tensile strength tests were carried out using the laboratory facilities of Sakarya University, while the flexural strength tests were carried out using the laboratory facilities of Sakarya University of Applied Sciences.

In the compressive strength test, cylindrical samples were placed in compressometers with potentiometers that can measure displacement in the axial and horizontal directions. Strain gauges were placed on the samples in the axial and horizontal directions. The displacement values were found by taking the average of the values in the strain gauges and potentiometers. The samples were taken to the hydraulic pressure machine with the compressometers and loaded in the axial direction at a speed of 0.5 MPa. Using the result of the compressive strength test, the stress values were calculated by dividing the load values by the cross-sectional area of the cylindrical sample. The axial strain values were obtained by dividing the average displacement values from the strain gauges and potentiometers placed in the axial direction by the length of the sample. The lateral strain values were similarly calculated by dividing the average lateral displacement values by the width of the sample.

In the splitting tensile test, a cage mechanism was created so that the cylindrical samples would be subjected to tensile force. The samples were placed horizontally in the pressure machine and loaded at a speed of 0.5 MPa. The results of the splitting tensile test were maximum load values, taken from the pressure machine.

In the flexural strength test, prismatic samples with dimensions of 100×100×400 mm were subjected to a 3-point bending test and the loading speed was determined as 5 mm/min. The distance between the supports in the bending test was determined as 300 mm. The formula for flexural stress used in the bending test is given in Equation (5) and the formula for flexural strain is given in Equation (6).

In Equations (5) and (6), represents the flexural strength of the samples, represents the load, represents the distance between the supports, represents the width of the samples, represents the depth of the samples, represents the flexural strain of the samples, and represents the deflection of the samples.

Photos of the experimental setups are given in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Experimental setups: (a) compressive, (b) splitting tensile, (c) flexural.

2.4. Experimental Results

The experimental results are presented collectively in Table 6.

Table 6.

Experimental results.

In the rest of this section, the results obtained from the experiments are given in more detail.

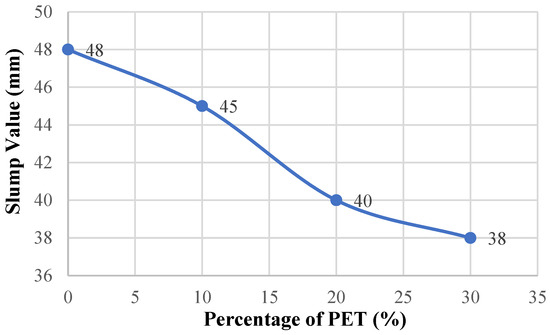

2.4.1. Slump

The results of the slump tests are given in Figure 5. The slump value was measured as 48 mm in the reference concrete. Gradual decreases were observed in the slump value as the PET substitution rate increased. The slump value decreased by 6.25% to 45 mm in the case of 10% PET substitution, by 16.67% to 40 mm in the case of 20% PET substitution, and by 20.83% to 38 mm in the case of 30% PET substitution.

Figure 5.

Slump–percentage of PET graph.

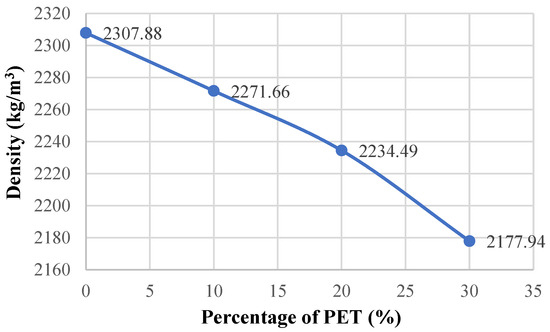

2.4.2. Density

The results of the density tests are given in Figure 6. The density value in the reference concrete was measured as 2307.88 kg/m3. As the PET substitution rate increased, gradual decreases were observed in the density value. The density value decreased by 1.57% to 2271.66 kg/m3 in the case of 10% PET substitution, decreased by 3.18% to 2234.49 kg/m3 in the case of 20% PET substitution, and decreased by 5.63% to 2177.94 kg/m3 in the case of 30% PET substitution.

Figure 6.

Density–percentage of PET graph.

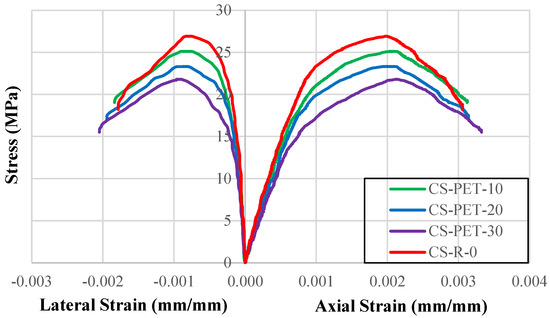

2.4.3. Compressive Strength

The stress–strain graphs obtained as a result of the compressive strength tests performed on samples without FRP are given in Figure 7. The maximum compressive strengths of the samples (), and axial strain () and lateral strain () values at maximum compressive strength, are given in Table 7. The compressive strength in the reference concrete was measured as 26.91 MPa. As the PET substitution ratio increased, the compressive strength decreased. The compressive strength decreased by 6.68% to 25.11 MPa in case of 10% PET substitution, by 13.36% to 23.31 MPa in case of 20% PET substitution, and by 18.99% to 21.80 MPa in case of 30% PET substitution. Axial and lateral strain values increased with increases in the PET substitution ratio, contrary to the trend in the compressive strength. The axial strain values increased by 2.83%, 7.58%, and 7.92% for 10%, 20%, and 30% substitution, respectively. These increases were 2.95%, 14.71%, and 21.50% for the lateral strain values.

Figure 7.

Stress–strain graphs of samples without FRP.

Table 7.

Compressive strength test results of samples without FRP.

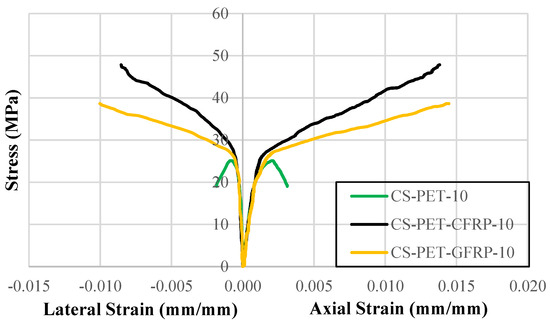

Stress–strain graphs of the samples using FRP and the sample with 10% PET substitution are given in Figure 8. The maximum compressive strengths (), and axial strain () and lateral strain () values at maximum compressive strength, of the samples using FRP are given in Table 8. The FRP wrapped around the 10% PET-substituted sample had a significant effect on the compressive strength and strain values. Although the strength value of the 10% PET-substituted sample was lower than the reference sample, it exceeded the strength value of the reference sample thanks to the CFRP and GFRP wrapped around it. The strength value of the 10% PET-substituted sample increased by 1.91 times, from 25.11 to 47.86, when it was wrapped with CFRP. It increased by 1.54 times to 38.66 when it was wrapped with GFRP. The axial strain values increased by 6.83 times in the CFRP-wrapping case and 7.15 times in the GFRP-wrapping case. The lateral strain values increased by 11.10 and 13.04 times for CFRP and GFRP, respectively.

Figure 8.

Stress–strain graphs of samples with FRP.

Table 8.

Compressive strength test results of samples with FRP.

2.4.4. Splitting Tensile Strength

The results of the splitting tensile strength test are given in Table 9. The splitting tensile strength of the reference concrete was found to be 2.46 MPa. Increases in the PET substitution rate caused decreases in the splitting tensile strength values. The splitting tensile strength decreased by 4.47% to 2.35 MPa in the case of 10% PET substitution, by 8.93% to 2.24 MPa in the case of 20% PET substitution, and by 12.11% to 2.16 MPa in the case of 30% PET substitution. The positive effect of FRP was observed in the splitting tensile strength tests as well as in the compressive strength tests. The splitting tensile strengths of the samples with 10% PET substitution reached 3.45 MPa when using CFRP and 3.04 MPa when using GFRP.

Table 9.

Splitting tensile strength test results.

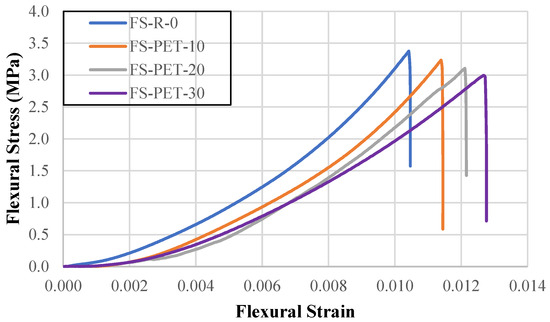

2.4.5. Flexural Strength

Figure 9 shows the graphs obtained as a result of the flexural strength tests of samples without FRP. Table 10 shows the flexural strength and maximum strain values of the samples. The flexural strength of the reference concrete was measured as 3.37 MPa. As the PET substitution rate increased, there were decreases in the flexural strength. The flexural strength decreased by 4.18% to 3.23 MPa in the case of 10% PET substitution, by 7.98% to 3.10 MPa in the case of 20% PET substitution, and by 11.17% to 3.00 MPa in the case of 30% PET substitution. The maximum strain values increased with increases in the PET substitution rate. The maximum strain increased by 9.36%, 16.16%, and 21.90% for the 10%, 20%, and 30% substitution cases, respectively.

Figure 9.

Flexural stress–flexural strain graph of samples without FRP.

Table 10.

Flexural strength test results of samples without FRP.

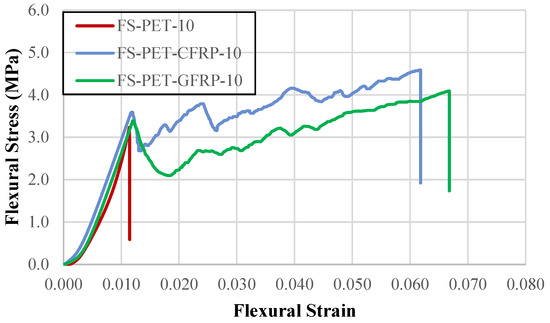

In Figure 10, the flexural stress–flexural strain curves of samples using FRP and the 10% PET-substituted sample are given. Table 11 shows the maximum flexural strengths and maximum strain values of samples using FRP. The 10% PET-substituted sample managed to exceed the reference sample in terms of compressive and splitting tensile strength as well as flexural strength due to the CFRP and GFRP wrapped around it. The flexural strength value of the 10% PET-substituted sample increased by 1.42 times when CFRP was wrapped around it, reaching 4.59 MPa. In the case of GFRP wrapping, it increased by 1.27 times and reached 4.09 MPa. The maximum strain value increased by 5.40 times when CFRP was wrapped, and by 5.84 times when GFRP was wrapped.

Figure 10.

Flexural stress–flexural strain graphs of samples with FRP.

Table 11.

Flexural strength test results of samples with FRP.

2.4.6. Modulus of Elasticity

Table 12 shows the elasticity modulus of the samples obtained from the graphs of the compressive strength test. The elasticity modulus of the reference concrete was found to be 30,574.17 MPa. Increasing the PET substitution rate decreased the elasticity modulus. The elasticity modulus decreased by 10.96% to 27,221.85 MPa in the case of 10% PET substitution, decreased by 18.03% to 25,061.49 MPa in the case of 20% PET substitution, and decreased by 30.27% to 21,320.87 MPa in the case of 30% PET substitution. The use of FRP increased the elasticity modulus of the 10% PET substitution sample very little, but the value of the reference sample could not be achieved. The elasticity modulus of the 10% PET substitution sample reached 27,512.26 MPa with the use of CFRP and 27,465.83 MPa with the use of GFRP. The slopes in the second part of the graph were 1704.56 in the case of using CFRP and 988.90 in the case of using GFRP.

Table 12.

Elasticity modules of the samples.

3. Experimental Database and Model Development

In this section, experimental databases were collected separately for PET-substituted concrete and FRP-confined concrete from the literature, and the results of this study were added to these databases. Model proposals were made for various properties of PET-substituted concrete based on the collected databases. The applicability of the proposed models and previously proposed models was checked.

Table 13 provides statistical metrics and their explanations for calculating how the results suggested by the models align with the experimental results. In Table 13, for calculating the R2 (coefficient of determination), MABE (mean absolute bias error), and MAPE (mean absolute percentage error) values, represents the experimental results, represents the model prediction, represents the average of the experimental results, and represents the average of the model predictions.

Table 13.

Statistical metrics.

3.1. PET-Substituted Concrete

The results obtained for PET-substituted concrete in the study were combined with previous experimental data in the literature and are given in Table 14. While creating Table 14, the following details were considered:

Table 14.

PET-substituted concrete experimental database.

- Only studies in which fine aggregate substitution was performed were considered; coarse aggregate substitution was not considered;

- Only granular substitution was used; fiber substitution was not used;

- Only concrete samples were added to the table; mortar samples and self-compacting concrete samples were not added;

- Only PET-substituted samples were used and no other type of plastic was used;

- For the compressive strength (CS), tensile strength (TS), and flexural strength (FS) tests, only 28-day data were collected and added to the table;

- If cube samples were used for the compressive and tensile strengths, the cylinder strengths were found by multiplying by 0.8 and written in a separate column in the table;

- Modulus of elasticity (MoE) values of the samples are in the table;

- Substitutions made were divided into two as volume (Vol) and weight (Wei);

- The sample dimensions used during the experiments are given in the table. If sample dimensions are not mentioned and the standard complied with is mentioned, the standard complied with is added to the table;

- The specific gravity and bulk density of PET material are given in the table;

- The sizes of PET material are added to the table;

- The PET substitution percentage is given in the table;

- Concrete density values are given in the table. If fresh and dry densities are given together in the study, only dry density is taken;

- The water/cement (W/C) ratio used in the formation of the concrete is given in the table;

- The slump test results are in the table.

In the literature, some previous studies on PET substitution in concrete have proposed models for the mechanical properties of concrete. The values in the experimental database have been transformed into graphs based on the models proposed for various properties of concrete. Various equations have been obtained from the graphs through trendlines, and newly developed models have been proposed. The proposed models have been analyzed alongside those in the literature, and their applicability has been assessed.

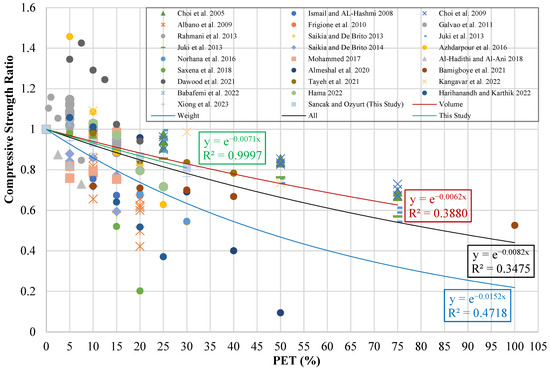

3.1.1. Compressive Strength Model Development

Table 14 shows the compressive strength values obtained from experimental studies in the literature. To better illustrate the effect of PET substitution on compressive strength, the compressive strengths of PET-substituted samples were divided by the compressive strength of the reference sample. The compressive strength graph was created by using the compressive strength ratio () as the vertical axis and the PET substitution percentage () as the horizontal axis. In this way, if the value on the vertical axis of the graph is greater than 1, it indicates that PET substitution has a positive effect on compressive strength. If the value is less than 1, it indicates that PET substitution has a negative effect. This graph is shown in Figure 11. With the help of trendlines fitted to the graph, model suggestions were made for volume substitution, weight substitution, the experimental data from this study, and all data. It was found that more accurate results could be obtained if the trendlines were drawn exponentially. In the models proposed in previous studies, linear equations were mostly used. Given this, all results were calculated both linearly and exponentially, and the developed models were proposed. The equations obtained and the developed models are presented in Table 15. In Table 15, represents the compressive strength of PET-substituted concrete, represents the compressive strength of unsubstituted concrete, and represents the PET substitution percentage.

Figure 11.

Compressive strength ratio–PET (%) graph [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Table 15.

Derived equations for compressive strength and proposed developed models.

The proposed improved models were subjected to applicability control, along with other models suggested in the literature for estimating the compressive strength of PET-substituted concrete. The control was carried out using statistical metrics with the data from the experimental database. The calculated values and models are provided in Table 16. In Table 16, represents the density of PET-substituted concrete.

Table 16.

Suggested models and performances for compressive strength.

In some models proposed in the literature, PET substitution was carried out in fiber form instead of granules. In other models, coarse aggregate was substituted instead of fine aggregate. These models are marked and shown in Table 16. Some models used the density value of PET-substituted concrete in their estimations. Since some studies in the dataset did not specify the value, the numbers of data points in these models were fewer than in the others. Similarly, since Meena and Ramana [38] proposed a model valid only for samples with up to 15% substitution, the data point in this model was also lower than in the others.

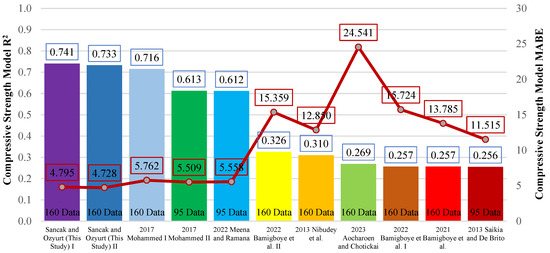

As a result of the metric analyses performed, it was found that the exponential and linear models proposed in this study were the most successful, with R2 values of 0.741 and 0.733, respectively. Following these two models, the model by Mohammed [19] came next, with an R2 value of 0.716. It was observed that the Saikia and De Brito [15] model had an R2 value of 0.256 and provided low accuracy results. Figure 12 shows the graph of the R2 and MABE values for the proposed models.

Figure 12.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for compressive strength models [15,19,32,36,37,38,39].

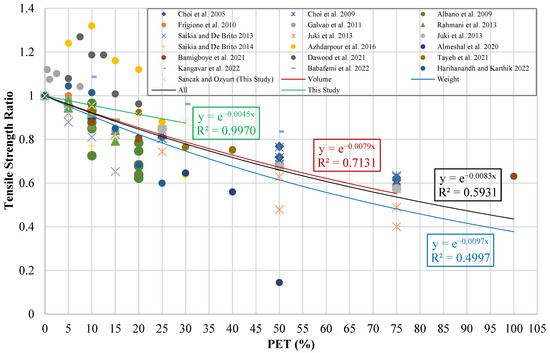

3.1.2. Tensile Strength Model Development

While creating the tensile strength graph of the data, a process similar to that used for the compressive strength graph was followed. A graph was created with one axis representing the tensile strength ratio () and the other axis representing the PET substitution percentage (). The resulting graph is shown in Figure 13. With the help of the trendlines fitted to the graph, model suggestions were made for volume substitution, weight substitution, the experimental data from this study, and all data. The equations obtained and the developed models are provided in Table 17. In Table 17, represents the tensile strength of PET-substituted concrete, represents the tensile strength of unsubstituted concrete, and represents the PET substitution percentage.

Figure 13.

Tensile strength ratio–PET (%) graph [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,21,22,26,27,28,31,32,33,34,35].

Table 17.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between tensile strength and PET substitution percentage.

The proposed improved models were subjected to an applicability check, along with other models in the literature that estimate the connection between PET substitution rate and the tensile strength of concrete. The check was performed using statistical metrics with data from the experimental database. The calculated values and models are provided in Table 18.

Table 18.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between tensile strength and PET substitution percentage.

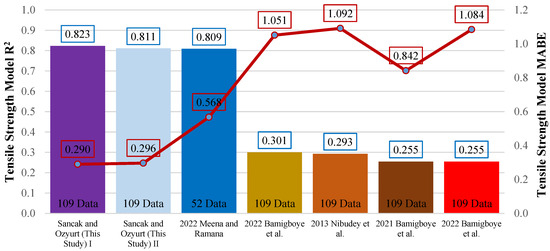

As a result of the metric analyses, it was found that among the models that included all tensile strength data, models I and II proposed by this study were the most successful, with R2 values of 0.823 and 0.811, respectively. It was determined that the models of Bamigboye et al. [32] and Bamigboye et al. [37] had an R2 value of 0.255 and provided low accuracy results. Since Meena and Ramana [38] proposed a model valid only for samples with up to 15% substitution, substitutions greater than 15% were not evaluated. Therefore, the data point in this model is lower than the others. Although a successful model was proposed with an R2 value of 0.809 for samples with a substitution rate of up to 15%, large errors were observed in the model’s predictions as the substitution percentage increased. Figure 14 shows the graph of the R2 and MABE values for the proposed models.

Figure 14.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between tensile strength and PET (%) [32,36,37,38].

The Connection Between Tensile Strength and Compressive Strength

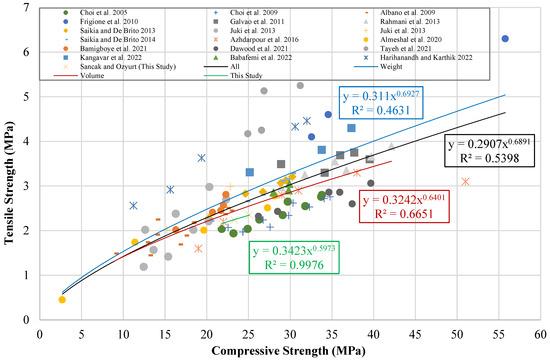

There are studies in the literature that examine the connection between the compressive strength and tensile strength of PET-substituted concrete samples and propose model suggestions in this regard. These suggestions were considered in this study, and a graph was created with tensile strength on one axis and compressive strength on the other. While creating this graph, the cube-shaped sample results were converted to the equivalent cylinder strength to avoid differences between compressive and tensile strengths. All results were processed in the graph to reflect the equivalent cylinder sample strength. The graph is shown in Figure 15. Model suggestions were generated using trendlines fitted to the graph. The equations obtained and the models developed are given in Table 19.

Figure 15.

Tensile strength–compressive strength graph [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,21,22,26,27,28,31,32,33,34,35].

Table 19.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength.

The proposed developed models were subjected to an applicability check, along with other models in the literature that predict the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength of PET-substituted concrete. The checks were performed using statistical metrics based on data from the experimental database. The calculated values and models are given in Table 20.

Table 20.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength.

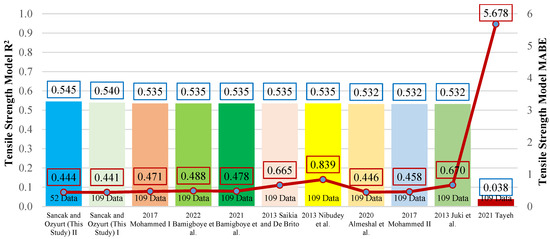

As a result of the metric analyses, it was found that models II and I proposed in this study were the most successful, with R2 values of 0.545 and 0.540, respectively. It was determined that the Tayeh [34] model had an R2 value of 0.038 and provided low accuracy results. Figure 16 shows the graph of the R2 and MABE values of the proposed models.

Figure 16.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength [15,17,31,32,34,36,37,40].

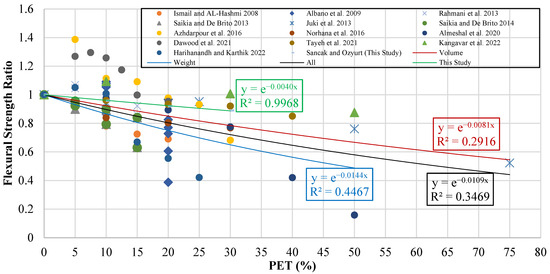

3.1.3. Flexural Strength Model Development

When creating the flexural strength graph from the data, a graph was plotted with the flexural strength ratio () on one axis and PET substitution percentage () on the other. The resulting graph is shown in Figure 17. Model suggestions were made for volume substitution, weight substitution, experimental data from this study, and all data, with the help of trendlines fitted to the graph. The equations obtained and the developed models are given in Table 21. In Table 21, represents the flexural strength of PET-substituted concrete, represents the flexural strength of unsubstituted concrete, and represents the PET substitution percentage.

Figure 17.

Flexural strength ratio–PET (%) graph [13,14,15,17,18,21,25,28,29,31,33,34,35].

Table 21.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between flexural strength and PET substitution percentage.

No other model has been found in the literature that estimates the connection between the PET substitution percentage and the flexural strength of concrete. The control was carried out using statistical metrics based on the experimental database. The calculated values are given in Table 21.

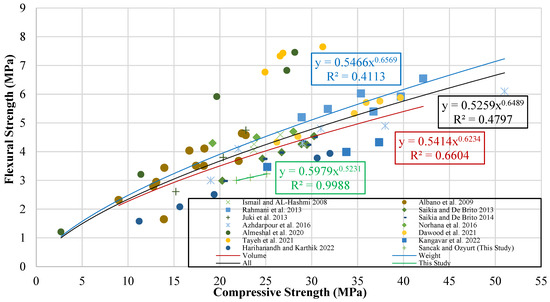

The Connection Between Flexural Strength and Compressive Strength

Some studies involving PET-substituted concrete samples have suggested a connection between compressive strength and flexural strength and have proposed models for this connection. In this study, these suggestions were considered, and a graph was created with flexural strength on one axis and compressive strength on the other. While creating this graph, the compressive strength was converted to cylinder sample strength. The resulting graph is shown in Figure 18. Model suggestions were made using trendlines fitted to the graph. The equations obtained and the models developed are given in Table 22.

Figure 18.

Flexural strength–compressive strength graph [13,14,15,17,18,21,25,28,29,31,33,34,35].

Table 22.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength.

The proposed developed models were subjected to an applicability check, along with other models in the literature that predict the relationship between the flexural strength and compressive strength of PET-substituted concrete. The checks were carried out using statistical metrics based on the experimental database. The calculated values and models are given in Table 23.

Table 23.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength.

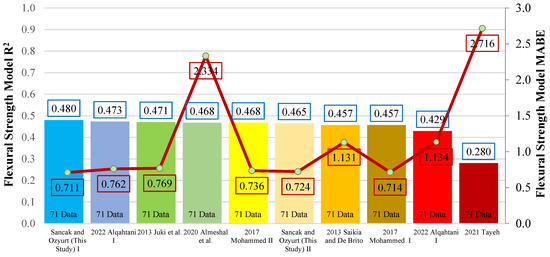

As a result of the metric analysis, it was found that model I proposed in this study was the most successful, with an R2 value of 0.480. It was determined that the Tayeh [34] model had an R2 value of 0.280 and provided low accuracy results. Figure 19 shows the graph of the R2 and MABE values of the proposed models.

Figure 19.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength [15,17,31,34,40,41].

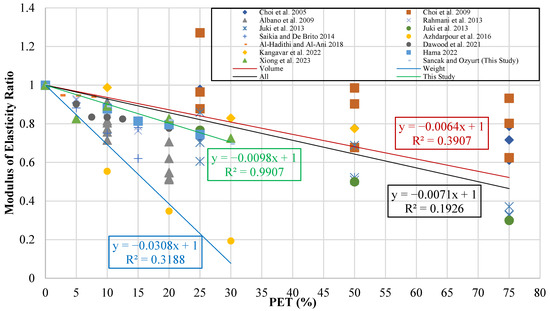

3.1.4. Modulus of Elasticity Model Development

While creating the elasticity modulus graph from the data, a graph was plotted with the elasticity modulus ratio () on one axis and PET substitution percentage () on the other. The resulting graph is shown in Figure 20. Model suggestions were made for volume substitution, weight substitution, experimental data from this study, and all data, with the help of a trendline on the graph. The equations obtained and the developed models are given in Table 24. In Table 24, represents the elasticity modulus of PET-substituted concrete, represents the elasticity modulus of unsubstituted concrete, and represents the PET substitution percentage.

Figure 20.

Modulus of elasticity ratio–PET (%) graph [11,12,13,14,16,17,18,20,21,23,24,28,33].

Table 24.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between modulus of elasticity and PET substitution percentage.

Among the previous studies, only Aocharoen and Chotickai [39] proposed a model that estimates the relationship between the PET substitution rate and the elasticity modulus of concrete. This model was subjected to applicability control together with the model obtained from this study. Control was carried out through statistical metrics using the data in the experimental database. The calculated values and models are given in Table 25.

Table 25.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between modulus of elasticity and PET substitution percentage.

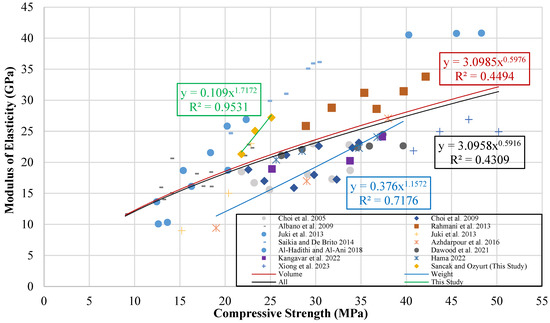

The Connection Between Modulus of Elasticity and Compressive Strength

To examine the connection between compressive strength and modulus of elasticity, a graph was created with compressive strength on one axis and modulus of elasticity on the other. The resulting graph is shown in Figure 21. Model suggestions were made by fitting trendlines to the graph. The equations obtained and the developed models are given in Table 26.

Figure 21.

Modulus of elasticity–compressive strength graph [11,12,13,14,16,17,18,20,21,23,24,28,33].

Table 26.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between modulus of elasticity and compressive strength.

The models estimating the connection between the elasticity modulus and compressive strength of PET-substituted concrete were subjected to applicability checks, along with other models from the literature. The checks were performed using statistical metrics based on an experimental database. The calculated values and models are presented in Table 27.

Table 27.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between modulus of elasticity and compressive strength.

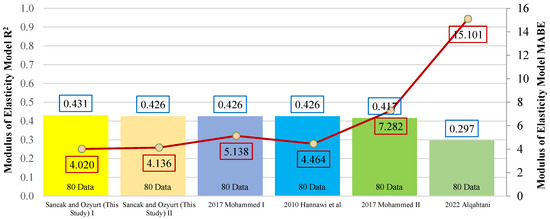

As a result of the metric analysis, it was found that model I, proposed in this study, was the most successful, with an R2 value of 0.431. The Alqahtani [41] model was found to have an R2 value of 0.297, indicating low accuracy. Figure 22 shows the graph of R2 and MABE values for the proposed models.

Figure 22.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between modules of elasticity and compressive strength [40,41,42].

3.2. FRP-Wrapping Effect

Previous researchers have considered the ultimate lateral confining pressure () of the FRP material, as defined in Equation (7). In Equation (7), represents the elasticity modulus of the FRP material, the thickness, and the ultimate tensile strain value. D represents the diameter of the concrete sample.

In a later study, researchers found that the FRP material ruptured at a lower strain value than expected during the experiment. Therefore, they suggested that using the FRP hoop rupture strain (), obtained by multiplying the FRP ultimate tensile strain () by the strain reduction factor (), would be useful. This value is calculated as shown in Equation (8). The equation for the actual ultimate lateral confining pressure (), obtained using the FRP hoop rupture strain (), is given in Equation (9).

In the study, samples with 10% PET substitution were wrapped in CFRP and GFRP, leading to increased compressive strength and strain values. The data from the experimental study, along with the sample and FRP properties, are given in Table 28.

Table 28.

FRP-confined concrete sample results and FRP properties.

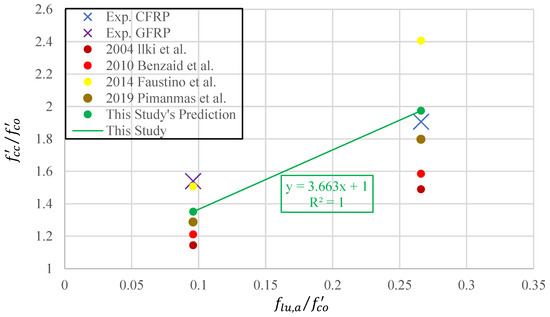

There are many model proposals in the literature that estimate the increase in compressive strength and strain values of concrete samples when FRPs are used. The predictions of some old and new models were compared with experimental data. A graph was created to compare compressive strength, with one axis representing and the other representing . The graph is shown in Figure 23.

Figure 23.

Experimental data and model predictions for compressive strength under FRP-wrapping effect [50,51,52,53].

Even though the experimental data are limited, a model was proposed for the compressive strength of PET-substituted concrete wrapped in FRP, using the trendline on the graph. The estimates from previous models are shown on the graph, and the MABE and MAPE values were calculated and are presented in Table 29.

Table 29.

Performance of FRP-confined concrete models for compressive strength.

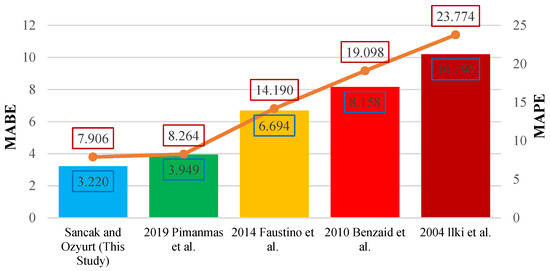

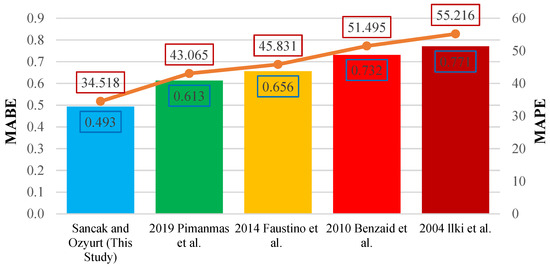

As a result of the metric analysis, it was found that the compressive strength model for PET-substituted concrete proposed in this study was the most successful, with an MABE value of 3.220. In general, all models produced consistent and similar results, and the more recent models were found to be more accurate. A graph showing the MABE and MAPE values of the proposed models is given in Figure 24.

Figure 24.

Comparison of MABE and MAPE for compressive strength models under FRP-wrapping effect [50,51,52,53].

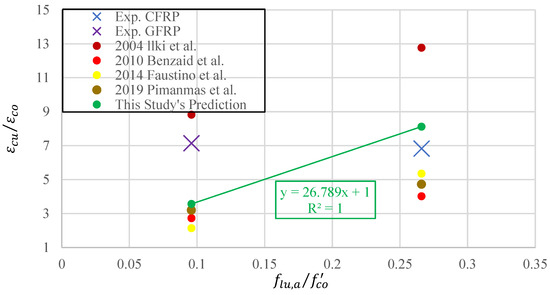

To compare the ultimate axial strain () values, a graph was created with one axis representing and the other representing . The graph is shown in Figure 25.

Figure 25.

Experimental data and model predictions for ultimate axial strain under FRP-wrapping effect [50,51,52,53].

Even though the experimental data are limited, a model was proposed for the ultimate axial strain value of PET-substituted concrete wrapped in FRP, using the trendline on the graph. The estimates from previous models are shown on the graph, and the MABE and MAPE values were calculated and are presented in Table 30.

Table 30.

Performance of FRP-confined concrete models for ultimate axial strain.

As a result of the statistical analysis, it was found that the ultimate axial strain model for PET-substituted concrete proposed in this study was the most successful, with an MABE value of 0.493. It was observed that the predictions of the Ilki et al. [50] model overestimated the experimental data, while the predictions of the other models were lower. The predictions of the more recent models were found to be more accurate. A graph showing the MABE and MAPE values of the proposed models is given in Figure 26.

Figure 26.

Comparison of MABE and MAPE for ultimate axial strain models under FRP-wrapping effect [50,51,52,53].

4. Conclusions

In this study, the effect of using PET as a fine aggregate substitute in concrete on various concrete properties was investigated. Additionally, the effects of using CFRP and GFRP in PET-substituted concrete were examined. A comprehensive experimental database was created for this study. Using this database, model proposals were made, and the prediction accuracy of previously proposed models was evaluated. As a result of the experiments and analyses, the following results emerged:

- For 30% PET substitution, the slump value decreased by approximately 20%. It was anticipated that further increasing the substitution rate could be disadvantageous for the workability of fresh concrete.

- Increasing the PET substitution rate decreased the density of concrete. It was concluded that PET substitution in concrete can contribute to reducing the weight of the structure or obtaining lightweight concrete if the concrete is used structurally.

- PET substitution in concrete decreased the elastic modulus, compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and flexural strength, while increasing the ultimate strain values. PET substitution can be used in cases where displacement is required, but it cannot be used to increase strength.

- The decrease in compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths due to PET substitution was compensated for by using FRP, which even exceeded the reference strength. Using PET inside the concrete and FRP outside is an effective method to obtain concrete that is both lighter and has more strength. It is considered usable in practical construction applications.

- The models proposed in this study were compatible with previous models and experimental data. They were found to provide the most accurate predictions and were applicable based on the experimental database.

It is thought that the number of studies using different rates of PET substitution, especially at high rates, should be increased. The possible effects of high-rate PET substitution on the behavior of concrete should be investigated in more detail.

The reliability of the proposed models is related to the quantity and quality of the data in the database. In this study, efforts were made to collect data from studies conducted on the subject so far. The presence of studies with vastly different results or insufficient experimental data may undermine the reliability of the models. It is important to note that the models may be revised as the content of the database evolves and the amount of data increases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.F.S. and M.Z.O.; methodology, O.F.S. and M.Z.O.; software, O.F.S.; validation, O.F.S. and M.Z.O.; formal analysis, O.F.S.; investigation, O.F.S.; resources, O.F.S. and M.Z.O.; data curation, O.F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.F.S.; writing—review and editing, O.F.S. and M.Z.O.; visualization, O.F.S.; supervision, O.F.S. and M.Z.O.; project administration, M.Z.O.; funding acquisition, O.F.S. and M.Z.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sakarya University Scientific Research Projects Unit, grant number 2024-26-61-21.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Raheem, A.B.; Noor, Z.Z.; Hassan, A.; Abd Hamid, M.K.; Samsudin, S.A.; Sabeen, A.H. Current developments in chemical recycling of post-consumer polyethylene terephthalate wastes for new materials production: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafighfard, T.; Cender, T.A.; Demir, E. Additive manufacturing of compliance optimized variable stiffness composites through short fiber alignment along curvilinear paths. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyathiar, P.; Kumar, P.; Carpenter, G.; Brace, J.; Mishra, D.K. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottle-to-bottle recycling for the beverage industry: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrington, A. Recycling of plastics. In Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; García, J.M. Chemical recycling of waste plastics for new materials production. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawecki, D.; Wu, Q.; Gonçalves, J.S.; Nowack, B. Polymer-specific dynamic probabilistic material flow analysis of seven polymers in Europe from 1950 to 2016. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, N.; Farfaras, N.; Wang, N.H.L.; Chen, W.T. Life cycle assessment of recycling high-density polyethylene plastic waste. J. Renew. Mater. 2021, 9, 1463–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, S.D.; Ribeiro, F.; O’brien, S.; Okoffo, E.; Toapanta, T.; Charlton, N.; Kaserzon, S.; Lin, C.-Y.; Tang, C.; Rauert, C.; et al. The message on the bottle: Rethinking plastic labelling to better encourage sustainable use. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 132, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmokaddem, M.; Mahi, A.; Senhadji, Y.; Pekmezci, B.Y. Mechanical and physical properties and morphology of concrete containing plastic waste as aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 257, 119559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, S.I.; Ali, M.R.; Al-Dulaijan, S.U.; Maslehuddin, M. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight recycled plastic aggregate concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.W.; Moon, D.J.; Chung, J.S.; Cho, S.K. Effects of waste PET bottles aggregate on the properties of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.W.; Moon, D.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lachemi, M. Characteristics of mortar and concrete containing fine aggregate manufactured from recycled waste polyethylene terephthalate bottles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2829–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, C.; Camacho, N.; Hernández, M.; Matheus, A.; Gutierrez, A.J.W.M. Influence of content and particle size of waste pet bottles on concrete behavior at different w/c ratios. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, E.; Dehestani, M.; Beygi, M.H.A.; Allahyari, H.; Nikbin, I.M. On the mechanical properties of concrete containing waste PET particles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, N.; Brito, J.D. Waste polyethylene terephthalate as an aggregate in concrete. Mater. Res. 2013, 16, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juki, M.I.; Muhamad, K.; Annas, M.M.K.; Boon, K.H.; Othman, N.; Kadir, A.B.A.; Asyraf, R.; Khalid, F.S. Development of concrete mix design nomograph containing polyethylene terephtalate (PET) as fine aggregate. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 701, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juki, M.I.; Awang, M.; Annas, M.M.K.; Boon, K.H.; Othman, N.; Kadir, A.B.A.; Roslan, M.A.; Khalid, F.S. Relationship between compressive, splitting tensile and flexural strength of concrete containing granulated waste polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles as fine aggregate. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 795, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, N.; De Brito, J. Mechanical properties and abrasion behaviour of concrete containing shredded PET bottle waste as a partial substitution of natural aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 52, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A. Flexural behavior and analysis of reinforced concrete beams made of recycled PET waste concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 155, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadithi, A.I.; Al-Ani, M.F. Effects of adding waste plastics on some properties of high performance concrete. In Proceedings of the 2018 11th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DeSE), Cambridge, UK, 2–5 September 2018; pp. 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangavar, M.E.; Lokuge, W.; Manalo, A.; Karunasena, W.; Frigione, M. Investigation on the properties of concrete with recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) granules as fine aggregate replacement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babafemi, A.J.; Sirba, N.; Paul, S.C.; Miah, M.J. Mechanical and durability assessment of recycled waste plastic (Resin8 & PET) eco-aggregate concrete. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, S.M. Behavior of concrete incorporating waste plastic as fine aggregate subjected to compression, impact load and bond resistance. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 3372–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Falliano, D.; Restuccia, L.; Di Trapani, F.; Demartino, C.; Marano, G.C. High-strain rate compressive behavior of concrete with two different substituted recycled plastic aggregates: Experimental characterization and probabilistic modeling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 130279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.Z.; Al-Hashmi, E.A. Use of waste plastic in concrete mixture as aggregate replacement. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2041–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigione, M. Recycling of PET bottles as fine aggregate in concrete. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvão, J.C.A.; Portella, K.F.; Joukoski, A.; Mendes, R.; Ferreira, E.S. Use of waste polymers in concrete for repair of dam hydraulic surfaces. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhdarpour, A.M.; Nikoudel, M.R.; Taheri, M. The effect of using polyethylene terephthalate particles on physical and strength-related properties of concrete; a laboratory evaluation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 109, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhana, A.R.; Kartini, K.; Hamidah, M.S. Recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and rubber crumb as replacement to fine aggregate. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.; Siddique, S.; Gupta, T.; Sharma, R.K.; Chaudhary, S. Impact resistance and energy absorption capacity of concrete containing plastic waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 176, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeshal, I.; Tayeh, B.A.; Alyousef, R.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Mohamed, A.M. Eco-friendly concrete containing recycled plastic as partial replacement for sand. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 4631–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamigboye, G.O.; Tarverdi, K.; Umoren, A.; Bassey, D.E.; Okorie, U.; Adediran, J. Evaluation of eco-friendly concrete having waste PET as fine aggregates. Clean. Mater. 2021, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, A.O.; Hayder, A.K.; Falih, R.S. Physical and mechanical properties of concrete containing PET wastes as a partial replacement for fine aggregates. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 14, e00482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, B.A.; Almeshal, I.; Magbool, H.M.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Alyousef, R. Performance of sustainable concrete containing different types of recycled plastic. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harihanandh, M.; Karthik, P. Feasibility study of recycled plastic waste as fine aggregates in concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 52, 1807–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibudey, R.N.; Nagarnaik, P.B.; Parbat, D.K.; Pande, A.M. Strengths prediction of plastic fiber reinforced concrete (M30). Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl 2013, 3, 1818–1825. [Google Scholar]

- Bamigboye, G.; Tarverdi, K.; Adigun, D.; Daniel, B.; Okorie, U.; Adediran, J. An appraisal of the mechanical, microstructural, and thermal characteristics of concrete containing waste PET as coarse aggregate. Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A.; Ramana, P.V. Mathematical model valuation for recycled material mechanical strengths. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aocharoen, Y.; Chotickai, P. Compressive mechanical and durability properties of concrete with polyethylene terephthalate and high-density polyethylene aggregates. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 12, 100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A. Modelling the mechanical properties of concrete containing PET waste aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 150, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, F.K. Development of composite PET plastic-based aggregate and its utilization in green lightweight concrete. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 13397–13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannawi, K.; Kamali-Bernard, S.; Prince, W. Physical and mechanical properties of mortars containing PET and PC waste aggregates. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 2312–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaidi, S.; Al-Kamaki, Y.S.S.; Al-Mahaidi, R.; Mohammed, A.S.; Ahmed, H.U.; Zaid, O.; Althoey, F.; Ahmad, J.; Isleem, H.F.; Bennetts, I. Investigation of the effectiveness of CFRP strengthening of concrete made with recycled waste PET fine plastic aggregate. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Lim, J.C.; Vincent, T. FRP-confined concrete in circular sections: Review and assessment of stress–strain models. Eng. Struct. 2013, 49, 1068–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey Castillo, E.; Griffith, M.; Ingham, J. Seismic behavior of RC columns flexurally strengthened with FRP sheets and FRP anchors. Compos. Struct. 2018, 203, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, F.; Asgarkhani, N.; Shafighfard, T.; Jankowski, R.; Yoo, D.Y. Machine-Learning Methods for Estimating Performance of Structural Concrete Members Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Chen, M.; Pan, J. Experimental study on seismic behaviours of hybrid FRP–steel-reinforced ECC–concrete composite columns. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 176, 107272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, G.; Zhou, P.; Li, C.; Dong, S.; Du, H.; Tian, J.; Guo, R.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; He, T. Mechanical properties evaluation of glass fiber reinforced thermoplastic composite plate under combined bending loading and water immersion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 440, 137470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valasaki, M.K.; Papakonstantinou, C.G. Fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) confined circular concrete columns: An experimental overview. Buildings 2023, 13, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilki, A.; Kumbasar, N.; Koc, V. Low strength concrete members externally confined with FRP sheets. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2004, 18, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaid, R.; Mesbah, H.; Chikh, N.E. FRP-confined concrete cylinders: Axial compression experiments and strength model. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2010, 29, 2469–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustino, P.; Chastre, C.; Paula, R. Design model for square RC columns under compression confined with CFRP. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2014, 57, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimanmas, A.; Saleem, S. Evaluation of existing stress–strain models and modeling of PET FRP–confined concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 04019303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- EN 933-1; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates—Part 1: Determination of Particle Size Distribution—Sieving Method. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Ağbulut, Ü.; Gürel, A.E.; Biçen, Y. Prediction of daily global solar radiation using different machine learning algorithms: Evaluation and comparison. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, H.; Ağbulut, Ü.; Gürel, A.E.; Yıldız, G.; Güvenç, U.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Hoang, A.T.; Deepanraj, B.; Saini, G.; Afzal, A. Forecasting of future greenhouse gas emission trajectory for India using energy and economic indexes with various metaheuristic algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 131946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C 78; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete. Annual Book of ASTM Standards. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- EN 12390-3; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- EN 12390-6; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 6: Tensile Splitting Strength of Test Specimens. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- EN 12390-5; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 5: Flexural Strength of Test Specimens. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- BS 1881-116; The Standard for Testing concrete—Method for Determination of Compressive Strength of Concrete Cubes. BSI: Macquarie Park, NSW, Australia, 1983.

- BS 1881-117; The Standard for Testing Concrete—Method for Determination of Tensile Splitting Strength. BSI: Macquarie Park, NSW, Australia, 1983.

- ASTM C293; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Center-Point Loading). Annual Book of ASTM Standards. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1979.

- NBR 5739; Concrete—Compression Test of Cylindric Specimens—Method of Test. ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; São Paulo, Brazil, 2007.

- NBR 7222; Mortar and Concrete—Determination of the Tension Strength of Cylindrical Specimens Submitted to Diametrical Compression—Method of Test. ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; São Paulo, Brazil, 1994.

- BS 1881; The Standard for Testing Concrete. BSI: Macquarie Park, NSW, Australia, 1983.

- ASTM C496; Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM C39/C39M-20; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).