Abstract

This study argues that Vision 2030 and social housing should consider the elements of the sociocultural dimension of urban design (SDUD) to alleviate urban poverty-induced feelings. By examining public spaces in the context of Vision 2030 and the implementation of social housing projects, this study aims to provide a theoretical framework that may assist city policymakers in rethinking the role of public spaces in alleviating poverty-related feelings. A review of the relevant literature explores the SDUD elements and builds an index to measure poverty through bibliometric and content analysis. This index was used to analyze the gaps in Vision 2030 in South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt, which we randomly chose. It focused on SDUD elements, social housing, and public spaces. We empirically examined the role of public spaces in alleviating poverty-related feelings using the SDUD index. We applied episodic narrative and interview-based storytelling techniques to a limited group of poor residents in the Al Asmarat Housing Project in Mokattam, Cairo, Egypt. This interview discusses the role of public spaces in reducing poverty-related feelings. The results focus on exploring the four SDUD elements of poverty and examining how public spaces alleviate poverty-induced feelings. Vision 2030 revolves around SDUD elements, social housing, and public spaces. Urban design policies can alleviate poverty in development projects for the poor. Integrating urban design policies into Vision 2030 makes city dwellers in developing countries feel less inferior.

1. Introduction

From a qualitative standpoint, this study emphasizes the critical role of public spaces in alleviating poverty-related feelings in Vision 2030 and social housing at the scale of urban form. Flourishing individuals is one of the domains of community well-being [1]. This approach treats deprivation as a psychological phenomenon, where economic and community well-being must be provided [2]. Well-being is not just meeting subsistence needs; in its broadest sense, it extends beyond meeting basic needs such as hunger, health care, and a safe place to live [3,4]. According to the UN-Habitat World Cities Report (2016), 1.6 billion people live in inadequate housing in developing countries [5]. Four years later, the official UN website (2020) declared that “about one in four urban residents’ lives in slums or informal settlements” [6]. In the same year, the World Bank reported that poverty reduction indicators in 2017 decreased significantly [7]. However, in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, there is still a risk of an increase in the number of impoverished people because their economies are weak. This would make it harder to reach some of the 2030 Agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals for fighting urban poverty.

There are many studies concerned with combating poverty, which have been conducted by international institutions [7,8,9,10,11] and scientific researchers [12,13,14,15,16]. However, these studies only look at the economic rates and dimensions (shown by numbers and percentages) related to hunger and food insecurity. Meanwhile, many theorists link poverty and well-being to food security and use food security to measure a city’s success [15,16]. The International Food Security Assessment expects that the ‘food security outlook [may] improve…by 2030 for 76 low- and middle-income countries’ despite ‘sharp income declines in 2020’ [11], p. 16. Moreover, many researchers and practitioners are now seeking to carefully assess poverty challenges in cities of the Global South, such as food access or food insecurity in Blantyre, Malawian [16], economic growth, human capital, and agricultural value related to urbanization in Vietnam [13], South Africa [14], and Nairobi, Kenya [15]. In this way, most of the research conducted in the social sciences has been on how to fight urban poverty in both the North and South of the world.

In prior studies, there was no evidence that urban design addressed alleviating poverty as part of Vision 2030. We searched Vision 2030, poverty, and urban design in the Web of Science (WOS) database in late November 2022, and found two articles between 2015 and 2022. Moreover, there is a need for more evidence that alleviating poverty in social housing could be achieved by focusing on poor residents’ feelings in public spaces. Four key terms and concepts are explained herein: urban poverty, public spaces, social housing, and Africa. In late November 2022, this article scanned the WOS database for these terms in academic journals between 2015–2022. From the social science, geography, planning and development, and urban studies categories, 349 manuscripts discuss “urban poverty”, 29,688 manuscripts focus on “public spaces”, and 196,682 manuscripts deal with “social housing”. We found 233 articles when we searched the three terms together, but only 5 when we added ‘Africa’. Thus, there needs to be more research concerning the role of public spaces in alleviating residents’ feelings of poverty in Africa. This study seeks to fill these gaps in the research.

Other studies have been developed to explore urban poverty by investigating how cities deal with threats to well-being, which included enhancing economic output and increasing productivity and urban agglomeration in Mexico [17], and the lack of urban green infrastructure for people experiencing poverty in South Africa [18]. Furthermore, several studies have focused on urban poverty in the Global North. Studies focused on designing and maintaining green spaces to meet cultural, recreational, and related needs and ensure equitable access for city residents in Sheffield, England [19]. Other studies examined the spatial structure, urban renewal, and walkability of Księży Młyn, Poland [20], the intensification of cultural production in disadvantaged communities in Newark, NJ, USA [21], and the urban morphology of Melbourne, Australia [22]. Other studies in the field of urban studies present the following poverty indicators: the erosion of social harmony and shifting the spatial distributions of poverty (its centralization and decentralization) in Welles in England [23]; creating urban public spaces to achieve social inclusion based on the passions, satisfactions, and urban experiences of citizens [24,25,26]; reducing feelings of exclusion by increasing the sense of belonging, which improves lives [27], and a national policy’s role in addressing public space and strengthening the participation of different stakeholders in that effort [28].

The following research questions are addressed in this study:

- Does Vision 2030 have an urban design gap regarding poverty challenges and urban policy? If so, how can we improve these policies?

- Should social housing consider the role of public spaces in alleviating poverty?

This study aims to provide a theoretical framework that helps city policymakers reconsider the role of public spaces in alleviating poverty-related feelings in Vision 2030 and implementing social housing projects. There are three objectives to achieve this purpose: (I) To identify the elements of the sociocultural dimension of urban design for poverty alleviation. Furthermore, to build the SDUD index based on four elements: sociocultural indicators, processes, principles, and criteria; (II) To review the use of these elements in Vision 2030 for three African countries. Then, it is critical to ensure that poverty can be combated at the scale of urban form; (III) To examine the role of public spaces in alleviating poverty-related feelings in an actual project using the four elements of the SDUD index, episodic narrative interviews [29], and storytelling [30,31].

By reviewing the literature published between 2019 and 2022, this study examines the elements of the SDUD index. It then looks at the visions for 2030 of three African countries—South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt—to see whether these elements are included. As part of developing housing projects for the poor, the analysis assumes that integrating the qualitative elements of SDUD associated with public spaces can alleviate residents’ feelings of poverty. It also emphasizes the literary definition of urban poverty.

This study relied on the opinions of some of the urban poverty obtained through episodic narrative interviews by Mueller (2019) to develop a framework that enables the measurement of the role of public spaces in development projects for people with low incomes to alleviate poverty-related feelings [29]. For two reasons, the Al Asmarat Housing Project in Mokattam in Cairo has been selected as a case study in Cairo, Egypt. First, the Al Asmarat Housing Project follows Egypt’s Vision 2030 nationally. It implements urban housing policies at the local level to help the urban poor who live in informal settlements. Second, regarding the status quo, the urban form of this project extends beyond qualitative planning, considering the principles and criteria of the SDUD, specifically as they relate to public spaces as part of developing social housing. An assessment of the socio-cultural dimension of urban design is presented as a contribution to urban poverty alleviation. It uses four elements to build the SDUD index to alleviate urban poverty: social indicators, societal processes, principles, and criteria. Another contribution is to explore the beliefs of poor residents. These beliefs help in the creation of a framework to quantify the role of public spaces in alleviating poverty in development projects for the poor. Using these elements, the index, and the framework, African countries and the Global South can implement Vision 2030 and urban policy for social housing more effectively.

Reassessing the SDUD index for combating poverty is of broad interest to urban design policymakers so that public and private actors can make informed decisions. A novel aspect of the study is revisiting the elements of the SDUD in alleviating poverty-related feelings in the international literature that previously focused on urban poverty. This revisitation concludes by integrating sociocultural indicators, societal processes, urban design principles, and criteria to build an index to alleviate poverty-related feelings, focusing on public spaces. An additional novelty is the application of episodic narrative interviews and storytelling techniques to measure residents’ feelings in developing countries and propose a framework for poverty feelings. Through this framework, the role of public spaces appears in social housing at the scale of urban form. The expected results will reveal the qualitative effect of public spaces on improving the feeling of being poor and deprived of necessities. Even if we assume that the economic conditions are substandard, improving psychological conditions may push people with low incomes to spread positive ideas that contribute to creating more favorable economic conditions.

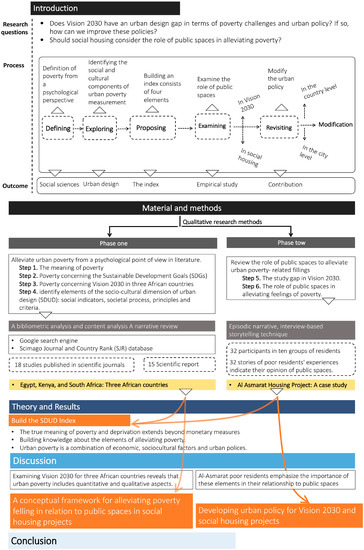

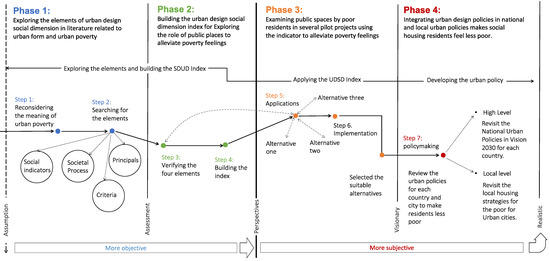

This study proposes alleviating poverty-related feelings through a process based on five steps. Figure 1 illustrates the research design in six sections after this introduction, followed by the materials and methods section that analyzes urban poverty by exploring relevant literature reviews. Using bibliometric analysis and content analysis, we examine the gaps in Vision 2030, followed by a case study of the Cairo’s Al Asmarat Housing Project. A narrative review-based storytelling technique was used to analyze the case study. From a psychological perspective, the third section discusses relative and absolute poverty, urban policies, Vision 2030 to alleviate poverty-related feelings, and social housing at the scale of urban form to alleviate poverty-related feelings. The SDUD index concludes this section. The following three sections discuss the results and two key findings and recommendations regarding public spaces to alleviate poverty-related feelings.

Figure 1.

The process of alleviating poverty-related feelings and the research design.

The fourth and fifth sections examine the validity of the assumption that there are gaps in the applications of Vision 2030 in the three African countries we examine in this study. In addition, they explore residents’ opinions on an actual social housing project in Egypt. This methodology considers urban design’s sociocultural dimension when developing policies for Vision 2030 and social housing. In its final section, this study summarizes public spaces’ role in alleviating poverty. The concluding remarks encourage policymakers to use the SDUD index to enhance the policies of Vision 2030 and social housing at the national and local levels.

2. Theory

The literature review in this section examines the meaning of poverty and its relationship with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Vision 2030. It looks for elements of the sociocultural dimension of urban design for poverty alleviation in the three African countries we examine in this study.

2.1. The Meaning of Poverty

Economic restraints and psychological burdens compound the sense of poverty regarding particular needs. King (1995) [32] considers how Albert Camus (1913–1961), in his unfinished novel The First Man, expressed that extreme poverty has exceptionally vivid odors [32]. Letemendia (1997) [33] adds that Camus—not Marx—mentioned that it was poverty that taught him the meaning of freedom and that Camus describes poverty as ‘the absolute deprivation of the necessities of life’ ([33] p. 242). Charles Dickens (1838), who preceded Camus, also offered a generative conception of social injustice as the basis of poverty and hunger [34].

The Asian Development Bank (2014) defined urban poverty as a multidimensional phenomenon related to income and non-income [9], while the World Bank Group (2018) defined poverty using physical dimensions related to the relationship between income levels and consumption rates [35]. Others in urban planning have linked poverty to sociocultural indicators, such as the prevalence of adequate housing for people who have been homeless or have experienced housing instability [36,37], the provision of education (basic literacy to university education) [38], and the availability of health services (e.g., healthy nutrition, infant and senior mortality, and life expectancy) [39,40,41]. In addition, the World Bank Group (2020) has also measured hospital-to-population ratios, doctor and support personnel availability rates, and general community services (e.g., utility networks, such as electricity, water, and sanitation) [7]. Meanwhile, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (2022) report focused on multidimensional poverty and the deprivation of the necessities of life, arguing that the lack of the luxury of living is part of poverty [42].

2.2. Poverty concerning the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Vision 2030

Since the 1980s, eradicating poverty has been an essential part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) work, conducted by the United Nations. The Brundtland Report (1987) referred to the basic principles of the concept of sustainable development [43]. During the UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, sustainable development principles were formally incorporated into international law. The Rio Declaration from this conference included 27 principles of sustainable development [44]. Sustainable development ensures sustainable consumption, production, climate, and living patterns. It also promotes peaceful and inclusive societies, ensures that everyone has access to justice, and sets up effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels with broad participation.

The United Nations (2015) launched eight Millennium Development Goals [45]: (1) Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; (2) Achieve universal primary education; (3) Promote gender equality and empower women; (4) Reduce child mortality; (5) Improve maternal health; (6) Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; (7) Ensure environmental sustainability; (8) Develop a global partnership for development. The United Nations (2015) presented 169 secondary goals associated with 17 Sustainable Development Goals [45]. The United Nations (2017) created a shared vision for a better and more sustainable future, including several intractable issues in the New Urban Agenda: poverty, hunger, health, education, equality, unpolluted water, clean energy, the economy, industry, innovation, infrastructure, reducing spatial equity, and sustainable cities and societies. Since the United Nations’ shared vision, many African cities have envisioned ending poverty by 2030 [46].

3. Materials and Methods

This study focuses on the urban policy in Vision 2030 and social housing. We assume that looking at the sociocultural dimension of urban design may assist in finding out how public spaces can help alleviate poverty-related feelings. Therefore, we proposed a sociocultural dimension of urban design (SDUD) index to alleviate poverty. First, based on our knowledge of absolute and relative poverty, we determined the elements of this index that would alleviate poverty on an urban scale. A social science literature review showed four factors contributing to poverty alleviation: social indicators, societal processes, principles, and criteria. Second, based on a critical analysis, we used these elements of the SDUD index to see if the assumption that there are gaps in Vision 2030 applications because they focus too much on the quantitative aspects was used. In this vein, we examined the expected effects of Vision 2030 on three African cities: South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt. This critical analysis confirmed that Vision 2030 in these three countries used these elements, individually or in combination. This analysis confirmed the importance of developing this use to combine the physical and qualitative aspects. Third, we discussed the role of public spaces in alleviating poverty using these elements, relying on two qualitative research methods. The first is using storytelling techniques to extract information from real-life experiences based on specific experiences [30]. The second is episodic narrative interviews, a phenomenon-driven research method developed by integrating several methods, such as semi-structured interviews, narrative inquiry, and episodic interviews. It is a method that extends beyond just telling stories because it takes into account social phenomena [29]. This section describes the case study and illustrates data collection and sampling.

3.1. The Case Study: Al Asmarat Housing Project in Cairo, Egypt

Egypt reduced extreme poverty (those living on less than USD 1.25 per day) by more than 62 percent between 1990 and 2008. However, 13 percent of the population will live in poverty by 2030 (with less than USD 3.10 daily) [47]. Egypt is one of the countries that recognize the importance of providing decent living conditions for its citizens, mainly those who live in poverty. Therefore, the Egyptian state has developed many informal areas (slums) within the state’s plan for sustainable urban development and in accordance with the 2030 Agenda [48].

Al Asmarat is a type of government housing, representing one of the choices citizens make in developing informal settlements [49]. Al Asmarat, also known as “Long Live Egypt City,” is the first urban agglomeration to meet the health, economic, and social needs of impoverished areas in Egypt [50]. The Al Asmarat Housing Project is a social solidarity project fully funded by the Egyptian government. These projects aim to alleviate the suffering of slum dwellers in Cairo. Most are low-income government employees or work jobs without a steady income, such as street vendors or daily workers. Furthermore, their informal settlements lack many elements needed for a decent life. These reasons support what was mentioned earlier regarding the research hypothesis, as well as that space quality and community well-being can make people feel less poor.

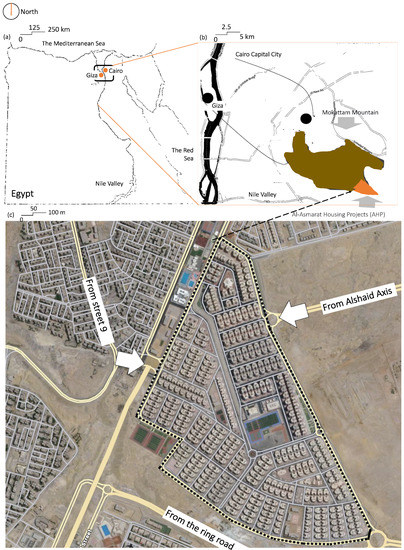

3.1.1. Geographical Location

The Al Asmarat Housing Project is a residential extension on the upper plateau of Mokattam Mountain. It is located southeast of Cairo, the capital of Egypt, and Giza, the second-largest city in Greater Cairo. The site is situated on 188 acres of undeveloped land. It includes 18,420 entirely constructed and furnished apartments with an area of 60 square meters. Three roads lead to the site: Street 9 in Mokattam, the Ring Road, and the Alshaid Axis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The study area’s geographical location and the site’s surrounding residential area: (a) Egypt; (b) Mokattam in Cairo; (c) Al Asmarat Housing Project.

3.1.2. Socio-Economic Base

The Egyptian government fully bears the costs of this social solidarity project, whereas housing is not within reach of poor citizens. The government has set the monthly rent at EGP 350 and has made an exception for groups that are vulnerable or unable to pay. Most citizens lived in poor neighborhoods, such as Ezbet Khairallah, Tal al-Aqrab, Mansheyet Nasser, al-Duwayqa, Qal’at al-Kabsh, al-Mawardi, Establ Antar, Batn al-Baqar, and Maspero Triangle, while some residents of Sayyad Aisha were extremely vulnerable.

Several studies have described the situation of poverty in the city of Al Asmarat as follows [51,52]: the monthly income ranges between less than EGP 1000 and sometimes up to EGP 2500. Most of these studies classified poverty based on people’s work in government jobs (couriers, security guards, etc.), permanent or seasonal service jobs, such as street and home cleaning, and handiwork, such as car mechanics, carpenters, and technical finishers. Some of whom are street vendors, who were also listed as living under the poverty line. Most of the residents in our case study work stable jobs and do not utilize the Pension and Social Security Fund. The people who participated in this study are illiterate, few of them know how to read and write, the ratio of primary education to technical education is medium, and only a small percentage has university education. In addition, the social structure of our case study includes divorced women, widows, and breadwinners. Many also have long-term illnesses or disabilities.

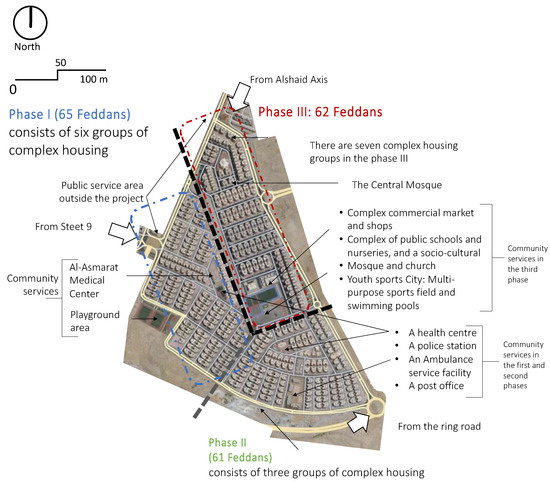

3.1.3. Master Plan

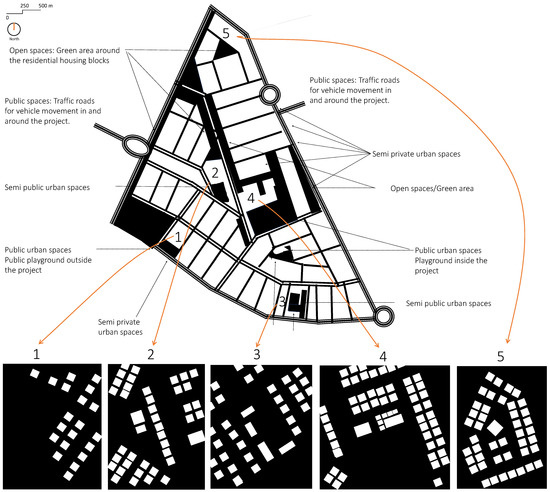

The “Tahya Misr” (Long Live Egypt in Arabic) fund implemented the project without user intervention, and the general plan took into account the relationship between the size of the project and the number of residents to form the new residential community. The project was implemented in three construction phases, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Master plan for Al Asmarat Housing Project: basic planning unit, a hierarchy of built-up areas, and phases.

The master plan is based on four fundamental ideas: an integrated community project, the basic planning unit, the hierarchy of built-up areas, and sequencing construction phasing. First, the city neighborhood constitutes the basic unit of development. It consists of complex residential groups in which nine-story residential buildings are arranged in independent residential groups with a multi-graded urban space, including a single-family model. Second, the master plan adheres to the road network’s functional hierarchy, which traditionally separates residential groups by vehicular roads. Third, the master plan follows the hierarchy of public spaces, represented by motorways and public, semi-public, and private urban spaces, ending with open green areas and parking lots. The master plan includes many public services, such as a complex of commercial markets, shops, schools, nurseries, mosques, and churches, in addition to a youth sports city, a multi-purpose sports stadium, swimming pools, a health center, a police station, an ambulance facility, a post office, and open spaces, such as playgrounds and car parking.

3.1.4. Micro-Scale Morphology: Urban Form

The urban form in Al Asmarat Housing consists of two main concepts. The first fully integrated project is based on a detailed construction plan with prototype housing and multi-story apartment buildings. It is wholly constructed and furnished. The second type of urban planning involves integrated grids with linear and nuclear urban tissues. It is made up of many different residential groups and housing clusters, with public spaces and community services between buildings.

Figure 4 shows the planning grid in a linear–nuclear pattern in several directions. The figure demonstrates grid planning, complex and cluster housing groups, urban hierarchy, public spaces, and community services. Each small group between the building blocks includes a semi-private urban space, representing the lowest degree of gradation of public spaces. Additionally, roadways surround each complex housing area separately.

Figure 4.

Grid planning, complex and cluster housing groups, and services.

The urban form of the Al Asmarat Housing Project addresses social housing in three phases, following the neighborhood planning philosophy of a flexible grid system. The master plan is a grid-based plan and urban layout designed to integrate a linear–nuclear urban structure distributed in complex residential groups and housing clusters interspersed with community services and public spaces. Al Asmarat’s master plan achieves similar planning units and streamlines spaces, roads, and community services. The idea of implementing three phases is based on the concept of complex or multi-family residential groups. There are six complex housing groups in the first stage, three in the second, and seven in the third. Each multi-family residential group contains small housing clusters ranging from 8 to 14 building blocks in two parallel rows constituting the basic planning unit (blocks).

The corresponding hierarchy of public spaces is also shown in Figure 5, which starts with the road network, followed by public urban spaces and open green spaces. Next comes the semi-public urban space, followed by the complex residential area.

Figure 5.

A site planning map. Types of public and open spaces with examples of element organization in the five figure-ground maps: blocks and public spaces.

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

This phase is divided into four steps. In the first phase, we used Google’s search engine and the Scimago Journal and Country Rank (SJR) database for bibliometric analysis. In addition, we conducted a narrative review using a content analysis approach guideline [53,54,55].

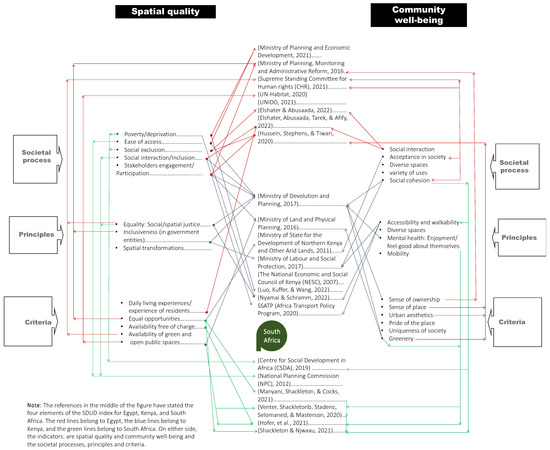

The first step was to build general knowledge on the meaning of urban poverty. This analysis showed that the true sense of poverty and deprivation extends beyond monetary measures. The second step explains poverty in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The third step focused on building knowledge on alleviating poverty through a preliminary analysis of scientific journals that published studies on the three African countries we examine in this study. The focus of the fourth step was on research that includes urban poverty, public spaces, social housing, and Africa, published in journals registered in the Scimago database between 2019 and 2022, provided that the research title, abstract, word indexing, or search text were the focus (Table S1). This process resulted in the sociocultural dimension of the urban design (SDUD) index, which measures the pattern of public spaces and principles of urban planning and design concerning sustainable development and urban poverty. The study relied on keywords in two groups of indicators: spatial quality and community well-being. Each group includes processes, principles, and criteria. After reading the whole text, the detailed research results showed that several words went together, indicating that our study was relevant to the research.

The second phase involves considering the elements of the SDUD index to conclude on two axes. First, we need to identify the study gap in Vision 2030, which lacks emphasis on the psychological aspects of fighting poverty and gives priority to the economic aspect. Second, it is about allowing people to know the essential needs for social housing and rethinking the role of public spaces in making people feel less poor.

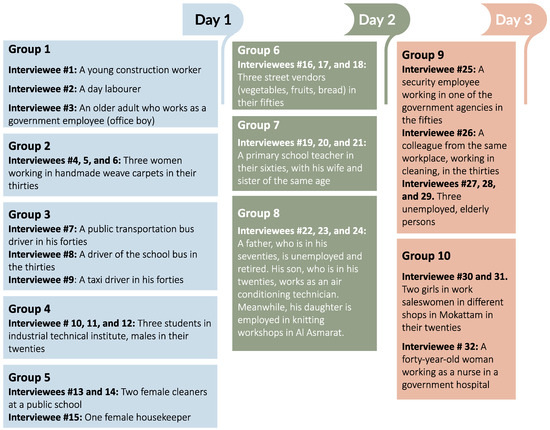

There are two more steps in this phase. The fifth step is examining Vision 2030 in the three African countries that were mentioned earlier to understand whether it is invalid to pay attention to the psychological aspects of alleviating poverty, using in fifteen scientific reports (Table S2). The sixth step aims to allow residents to tell stories from their experiences of their daily lives to express their opinions, desires, and perceptions about fighting poverty. We are committed to using the SDUD index’s elements to determine people’s thoughts. At this step, we relied on the fact that the sample members have lived in Al Asmarat since its formation, and their economic and occupational status indicates that they are indeed poor. We used Mueller’s six steps for the episodic narrative interview method [29]: (I) We evaluated the phenomenon of concern on ‘the role of public spaces in alleviating feelings of poverty’; (II) We explained the reason for the interview with population groups aiming to develop social housing for poverty alleviation. We made it clear to each group of residents that the interview would take ten minutes at most and would be based on a dialogue about this phenomenon alone; (III) We elaborated on the power of public spaces in social housing as an opportunity to alleviate feelings of poverty; (IV) We asked each participant to tell a story about their feelings on public spaces in Asmarat; (V) We asked some of them to describe their personal experience with and feelings about those public spaces; (VI) We asked each group isa they would like to add anything to the narrative they shared. Thirty-two participants divided into ten groups were interviewed to assess if public spaces changed their feelings about poverty. The interviews focused on three description categories regarding shared experiences (see also Table S3):

- Can I accept and integrate the same rights to use with neighbors, exclude others from using, and engage in unneighborly interaction with the community?

- What about ease of access, equal opportunities, walkability, accessibility, mobility, new experiences, aesthetics, and similarity?

- How do the availability and meeting the local needs of public spaces contribute to mental health, satisfaction, care, and pride?

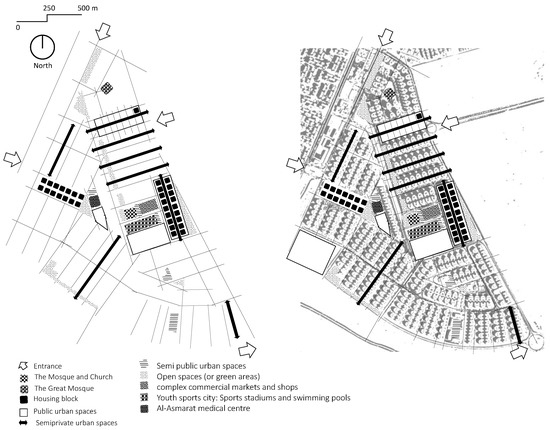

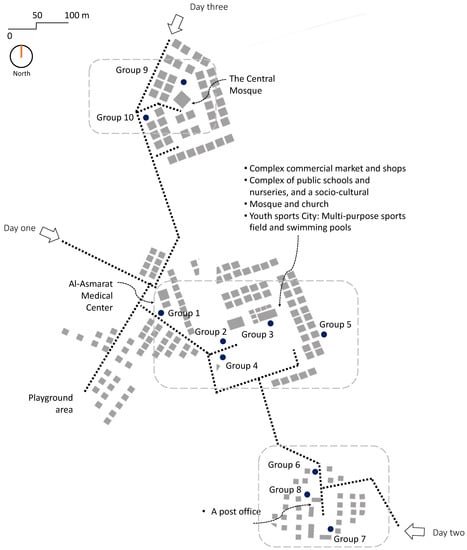

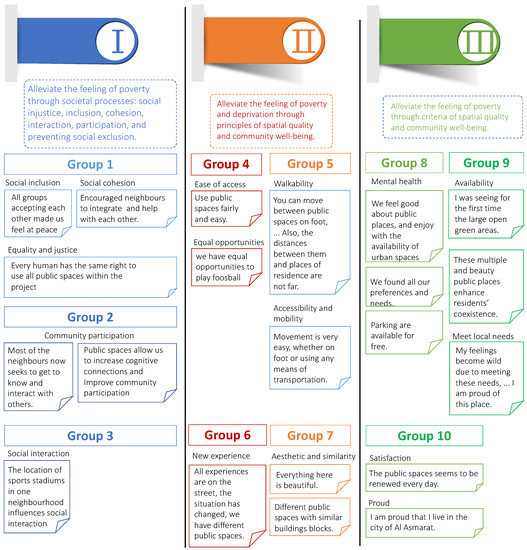

Thirty-two participants were divided into ten groups (Figure 6). The thirty-two participants were divided into ten groups; no group included more than five individuals and our interviewing style was personal, so that accurate results could be obtained. There were five groups on the first day (15 participants), three groups on the second day (nine participants), and two groups on the last day (eight participants). In November 2022, interviews were conducted every Friday, a holiday.

Figure 6.

The 32 participants represented different ages, careers, and genders.

Episodic interviews were conducted in public spaces, not citizens’ homes or workplaces (Figure 7). Finding and communicating with participants took more time than preparing the appetizers. The storytelling with each group took at most half an hour. At the scale of urban form, we have identified for the discussion three directions: the need for public spaces, missing design principles, and possible solutions. Before engaging residents, we agreed as a group that public spaces were defined as streets, parks, open areas between buildings, semi-public spaces associated with neighboring activities, and even semi-private spaces related to different activities. Lastly, the dialogue had to not deviate from the following main points: feelings, poverty, open spaces, social housing, personal experiences, the Al Asmarat Project, and informal settlements. As part of the process of extracting the results, we crossed out all topics that were outside the indexing words. Lastly, we made it clear that personal information or political issues should not be included, even if they have to do with social housing.

Figure 7.

Interview itinerary and the locations of three groups of participants.

The current work has two limitations. Firstly, the study focused on a single social housing project and few participants. Several social housing projects must be included in future studies in many African countries. The participants must represent a certain percentage for the results to be accurate. Secondly, the study uses a traditional method of collecting data from participants. The results should be collected and unloaded using a technologically advanced program. The familiar words repeated in each story make it essential to analyze the interviewees’ stories. This repetition may indicate the stories’ most significant elements and, therefore, the hypothesis test. The study required more people than we had available. Training in the use of the latest technology was provided to these individuals.

4. Results from Bibliometric Analysis

4.1. Poverty concerning Vision 2030 in Three African Countries

This section examines the expected effects of Vision 2030 on three African cities: South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt. In the following critical analysis, we will discuss three aspects of each country’s vision: societal aspects, features of the housing strategy in-development projects, and public spaces.

Egypt’s vision consisted of two parts (Ministry of Planning and Economic Development, 2021; UNIDO, 2021) [56,57]: (a) Economic growth, increasing trade, investment, and labor productivity; (b) Social aspect: social justice (focus on health and education), gender equality (empowerment of women), equal opportunities, and governance (transparency). In social housing, Egypt creates diverse spaces, encourages walkability, availability of green and open public spaces, and implements the construction of green buildings [58]. In Egypt, within the state’s plan for sustainable urban development and in accordance to Vision 2030, the Ministry of Planning, Monitoring, and Administrative Reform (2016) stated that many social housing projects were established to develop informal settlements (slums) and eliminate dangerous areas [48]. UN-Habitat (2020) [59] states that Egyptian social housing aims to address its citizens’ housing needs and social welfare. Social housing projects meet the social dimension, including social justice, equity, and sustainable urban forms for adequate, safe, and healthy housing. They also focus on sociocultural integration, recreational, mental, and physical health facilities, economic activities on pedestrian paths and public spaces, and the use of space for economic and social activities [31,60]. In line with the SDGs and Egypt’s Vision 2030, a key feature of Egypt’s housing strategy in its development projects is encouraging social cohesion (Supreme Standing Committee for Human Rights) [49]. The social housing project in Egypt focuses on “decent housing” and “decent life” programs [26,49].

According to the National Economic and Social Council of Kenya (NESC) (2007), Vision 2030 is divided into three categories [61]. The first category includes working with the government to provide jobs, combat poverty, and provide large-scale income-generating activities. The second category is the social aspect, which focuses on enhancing a sound and healthy social environment and reducing inequalities (equality) for vulnerable groups in poor societies (e.g., young people, women, and the marginalized). The topics that are addressed are education and training, water and sanitation distribution, public transportation improvements, hygiene, the environment, housing, and urbanization. This category focuses on the requirement of ensuring equal access to public services. The third category is the political aspect, which focuses on a democratic governance that respects individual freedom and the law. The Ministry of Land and Physical Planning (2016) [62] indicates that the three aspects of this vision are economic, social, and political. In this vein, the National Spatial Plan (2015–2045) includes seven principles [62]: effective public participation and engagement, urban containment and compact cities, livability, smart and green urban growth, sustainable development, promotion of ecological integrity, and promotion of public transportation (to ensure the efficiency and functionality of urban spaces) ([62], p. 19).

Following the Ministry of Devolution and Planning (2017), the Kenyan Constitution, 2010, aims to make Kenya more equitable and inclusive [63]. This constitution emphasizes social protection, namely the right to adequate food, food security, and decent livelihoods. Kenya’s vision also emphasized that people should not be left out of society to protect society and social cohesion [64]. Social protection also includes the principles of equality, and equally accessible and equal opportunities ([64], p. 21). Regarding social housing, Kenya’s vision focuses on providing adequate housing in a sustainable environment for those living in informal settlements ([64], p. 39). It provides sufficient, appropriate, and affordable housing in a sustainable environment in northern Kenya, with equal opportunities ([65], p. 94). Initiatives adopted by Kenya as part of its green economy strategy intend to support the nation’s development efforts in addressing poverty and inequality ([65], p. 40). Aside from providing adequate, affordable housing for the rest of the population, equal access is being sought [61]; however, there has been no mention of public spaces.

South Africa is among the leaders in adopting green economy strategies through programs to promote energy efficiency, green transportation, sustainable housing, climate-resilient agriculture, and improving the quality of life. According to the South African National Planning Commission (2012), Vision 2030 included two aspects [66]: (a) The human side, which aims to combat poverty and inequality in education, human capacity development, economic growth, and job creation; (b) The urban side, which includes land redistribution, construction (housing, schools, and hospitals) and utilities (water, sanitation, and energy). Regarding social housing, the South African vision focused on compact urban development, and mixed housing strategies are being promoted to make public spaces and facilities more accessible and improve household life quality. As part of the vision, state-owned land was used to provide affordable housing to people experiencing poverty, improve informal settlements, and transform them into well-located accommodations, in addition to the state’s activities that aimed to achieve “optimal settlement performance” through a set of actions, including the creation of public spaces. The essential criteria are ease of access, quality development, encouraging social interactions that meet social cohesion and common understanding, and equal opportunities for all to share everyday experiences.

4.2. What Elements of the Sociocultural Dimension of Urban Design Alleviate Poverty?

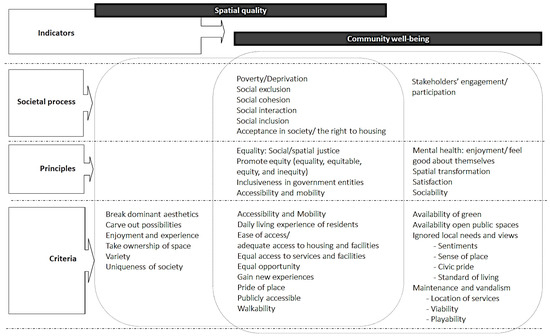

A number of recent studies have indicated that several elements of the sociocultural dimension of urban design can alleviate poverty. Previous studies have emphasized these elements through spatial quality and community well-being indicators.

4.2.1. Spatial Quality

Acre and Wyckmans (2014) define spatial quality as a combination of physical, cognitive, and societal characteristics [67]. Quality enhances the collective’s presence in public spaces throughout the day by providing diverse functions, activities, and physical elements. This issue focuses on social cohesion, urban vitality principles, and cities’ liveliness. For example, Khalili and Fallah (2018) examine how women live in their communities [68]. Therefore, this study tackles the issue of having the ability to participate in regular relationships and activities, ensuring no one is denied access or participation. It notes that poverty and equality are centered on exclusion, disadvantage (for poverty), and deprivation (for equality). Garau and Annunziata (2022) look at the social effects of urban form while moving from one activity to another [69]. Mouratidis and Yiannakou (2020) indicate how vibrant neighborhoods foster strong communities [70].

There is a wide choice of principles and criteria for public space design related to the processes of exclusion and deprivation available in the literature [71]. One of these principles is spatial transformation, which focuses on social exclusion and its different factors, such as taking away options and private space and breaking the prevailing aesthetics [72]. Another principle is access to public spaces for all groups of a local community regardless of gender, age, employment status, financial status, and physical disability [19,73,74]. Researchers used a variety of criteria to assess societal deprivation and inclusion, including satisfaction, standard of living [24], equal opportunities [75,76], promoting equity and equal access (publicly accessible) [19], accessibility and mobility [77], more accessible urban spaces [18,73], citizens’ emotions, satisfaction, urban experience [78], and adequate distance to facilities [79].

4.2.2. Community Well-Being

Previous studies have shown the importance of using public spaces flexibly to meet the population’s diverse needs [80,81]. For example, The Asian Development Bank (2014) stated that public spaces should provide an attractive and exciting cultural space that is socially acceptable to all users to achieve social inclusion and acceptance in society [9]. Such spaces also aim to achieve social integration and acceptance as an alternative to exclusion and preference [81]. Urban resilience should improve people’s well-being by creating inclusive urban public spaces where people have more positive experiences, a stronger sense of place, and a higher quality of civic pride [82,83].

Fast food restaurants, cafes, retail kiosks, and modern popular markets offer services that meet daily needs and boost morale, making people feel less bored or deprived. Sitting, children playing, social gatherings, and hiking for both sexes, young people, and older people are examples of these activities. The design of public spaces should increase the urban vitality of the cities by incorporating principles of participation, livability, and availability, as well as several criteria, such as social interaction and experience, walkability, and playability [68,70,84], more abundant, accessible [76], and greener [18] public spaces, viability, and friendliness. In addition, creating an atmosphere of psychological comfort and optimism is another way to make people happy and feel good about themselves [78,82]. Previous research has found that spatial quality and community well-being are the most complex elements of combating urban poverty. It was reported in the literature that the urban design social dimension index could consist of three elements, social processes, design principles, and criteria, according to the sociocultural indicators at the scale of the urban form [85]. Table 1 shows the four elements of the SDUD index with the relevant references.

Table 1.

The four elements of the SDUD index with relevant references.

4.3. Does Vision 2030 for Three African Countries Use the Elements of the SDUD?

This section summarizes the findings for three African countries, Egypt, Kenya, and South Africa, as well as searches the four elements of the SDUD index for alleviating poverty in greater detail in each vision (Figure 8). A key finding of this study is that the 2030 visions for urban poverty will focus on quantitative and qualitative measures. When comparing these visions in three countries—South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt—SDUD index elements are undoubtedly present, especially concerning social housing projects. In a similar vein, the results show that using the SDUD index elements in public spaces is much better understood when involving the community and creating more green spaces.

Figure 8.

The four SUDU elements used in Vision 2030 are for three African countries: Egypt [49,56,57,58,62,80,82,86] Kenya [61,62,63,64,65,77,79], and South Africa [18,66,67,78,83,87].

The three visions in this study aspire to all age groups and groups with special needs having safe access to green cities and having an equal amount of green and open spaces. Vision 2030 for Egypt, Kenya, and South Africa addresses several aspects of urban poverty, including economic, human, sociocultural, political, and sustainable urban development. Each vision focuses on affordable housing for people with low incomes (social housing) to improve their quality of life. It strives for equality: social/spatial justice, social interaction, social cohesion, and equal opportunities for everyone in their everyday experiences. It looks at public spaces through variety, vitality, and equal access to public services.

5. Results

5.1. Can Public Spaces Help Alleviate Poverty-Related Feelings in Social Housing in Egypt?

The literature review reveals that two key indicators are necessary for understanding the sociocultural dimension: spatial quality and community well-being. The societal processes include deprivation, social exclusion, social inclusion, stakeholder engagement, and city vitality/liveliness. At the same time, the principles varied between spatial transformations, quality of life, well-being, justice, equity/social cohesion/inequity, inequalities, inclusion, participation, livability, and availability. Furthermore, the criteria were as follows: carving out possibilities, taking control of space, breaking dominant aesthetics, distance to facilities, satisfaction, standard of living, equality of opportunities, promoting equity, accessibility, mobility, being more accessible, citizens’ emotions, urban experience, sense of place, civic pride, quality of life, experiences of residents, walkability, playability, viability, and conviviality (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The elements of the SDUD index.

This study has explored the elements of the SDUD index. The results answered the two questions in the introduction section. First, the SDUD index elements alleviate poverty in Vision 2030 for the three African countries we explore in this study. Second, the results confirm that specific public spaces in Al Asmarat can alleviate poverty.

Experiences in public spaces can be enhanced by engaging in SDUD discussions with different participants. Based on the literature review on the scale of urban form, the SDUD index elements examined were used in this section. We have identified three directions of discussion on the scale of urban form to examine three aspects (see also Table S2): (I) Alleviating the feeling of poverty through inclusion (integration), cohesion, interaction, and preventing social exclusion; (II) Alleviating the sense of poverty and deprivation through the availability and variety of public spaces; (III) Alleviating the feeling of poverty through spatial quality and community well-being.

The preliminary results of the episodic interviews showed that people experiencing poverty perceive public spaces as an inexpensive outlet to entertain themselves outside the walls of their homes, which can barely accommodate the members of the family. Men and women of all age groups, as well as children agreed on the importance of these spaces for work and leisure. Several young men and women reported that finding a place to go out walking, jogging, or participating in a recreational or sporting activity significantly reduced their psychological suffering. Based on the SDUD index, the results regarding the alleviation of feelings of poverty regarding spatial quality and community well-being are as follows.

5.2. First Indicator: Spatial Quality

This study confirmed the findings regarding social cohesion, inclusion, and exclusion. Most participants claimed that the public spaces in Al Asmarat created a welcoming environment and introduced the concept of dealing with neighbors with kindness. One of the participants in Group 1, a young construction worker, said, “[…] Every human has the same right to everything within the project.” A day laborer believed that “[…] the availability of public spaces with sufficient space, openness to the whole project without putting up fences or restrictions, … encouraged neighbors to help and to integrate.” An elderly man who is a government employee added, “[…] The nonacceptance of some people towards the poor makes us resentful…, accommodating all groups and accustoming them to accepting each other made us feel at peace.”

The results show that public spaces reflect the essential value of social interaction, cohesion, and community participation between neighbors. These spaces attract different types of residents, regardless of their background. The results then examined the preferences of the local population of Al Asmarat, who move together between different informal settlements in the city of Cairo and have no prior knowledge of the different types of public spaces. Moreover, the results showed that many had achieved high levels of social interaction among the population, which is most prevalent in public parks, sports club spaces, public buildings, and markets. Women appear to be the happiest group, with many urban spaces close to their homes. According to one Group 2 participant, a woman who weaves handmade carpets in one of Asmara’s workshops, she “[…] dealt with most of the neighbors and now seeks to get to know and interact with others because of the wonderful allocations of all these open spaces.” Another woman who works in the same place added, “[…] Neighbors are vital, whether we want to entertain ourselves or do work together…, the workshops below the buildings have neighbors from everywhere in the buildings, near and far.” A third woman said, “[…] Public spaces allow to increase cognitive connections, … it also improves community participation.”

Three more men working as drivers who were Group 3 participants reported that the real outings occur in the street or any public place near their residences. A bus driver in his fifties explained, “[…] Often, we used open spaces to sit outside for chatting and smoking away from the family in the house. We do not sit on balconies, especially on the ninth floor.” His neighbor, a school bus driver, said, “[…] I would have preferred that the public spaces were connected to the playgrounds and each group of residential buildings so that the interaction between members of the residential groups would be more relevant.” A third participant, a taxi driver, said, “[…] Social interaction in Egyptian environments is different from Western environments; we do not have to know each other personally, but at least we should have a face-to-face relationship.” The location of sports stadiums in one of the studied neighborhoods influences social interaction at the neighborhood level.

The matter of entering and using public spaces without paying fees or subscriptions arises when discussing residents’ ability to use public spaces fairly and easily. Different groups discussed equality and justice regarding their right to similar social services as those used by more economically privileged groups. An industrial technical institute student from Group 4 said, “I wish I could play football… today I found the opportunities to fulfill my life’s dream.” His colleague said, “[…] sports stadiums compensate for not being able to join sports clubs…, after we learn our skills here, we can join any sports club in the country.” A third colleague said, “[…] Now I can take my grandchildren to the sports stadiums. We have equal opportunities to play foosball… maybe someone will be like Mo Salah.”

Some positive and negative aspects were voiced by Group 5 participants. Walkability, accessibility, and mobility were considered positive aspects. Regarding housekeeping, a female worker said, “[…] Movement is effortless, whether on foot or using any means of transportation.” She added, “[…] You can move between public spaces on foot, … also, the distances between them and their places of residence are not far.” As for shortcomings, the other two female cleaners commented that the spaces between buildings (meaning semi-private spaces) only consider the requirements and needs of some family members. A female cleaner working in a public school indicated that she lived on the eighth floor and said, “[…] I cannot leave her young children playing in the green areas at the bottom of the building with children she does not know. There are no places where they can stay with the children when they play in front of the buildings.” A third female cleaner, who works in a shopping mall, added, “[…] There are no places where women gather to talk or have fun, like in our old place of residence…, here the residents know each other only from their faces.”

Group 6 participants seemed surprised by how the feelings these new experiences evoked in them. The majority confirmed that it was an entirely different experience from all their previous experiences. A young person spoke with emotion, “[…] We were not used to these places before… You know that slums do not have public spaces.” His peer continued, “[…] All our experiences are on the street, whether sitting in cafes or front of houses on the sidewalks, even playing football in the street… the situation has changed; we have different public spaces.” A third peer added, “[…] let me describe my experience of spring celebrations (Sham El Nessim), … we celebrated in public parks and on the central islands in the wide streets, and we were pleased.” In response to our question about their aspirations for the future after this novel experience, one asked a metaphorical question: “[…] How would you feel if you were able to do this every day, or on every occasion, without anyone bothering you or objecting?” Here, the three young people stressed the importance of maintaining these changes in the future, and that the housing administration should not come at any time to prevent them from sitting or celebrating in public spaces in complete comfort.

Nevertheless, only a few participants have touched on the aesthetics of urbanization. In Group 7, some residents pointed out the similarities between the buildings, “[…] Everything here is beautiful”, a primary school teacher said succinctly. However, his wife said, “[…] I lived in Al Asmarat for about a year. Every time I go out with my granddaughter, we lose direction and get lost, … Until now, we do not know where we live, all the buildings are the same, and the distances between them are the same.” His sister intervened and said, “[…] The public spaces here are all the same, … The difference may be visible in structures such as the mosque, church, and mall… those we use as landmarks to direct us to our destination.”

5.3. Second Indicator: Community Well-Being

The implications of these findings concern three aspects. First, the basic principles are local preferences, needs, saturation levels, and coexistence. They also showed three related criteria: meeting local needs and opinions, respecting the population’s feelings, and creating a sense of place that leads to pride. Second, the standard of living has increased beyond imagination, with the availability of playground areas, vegetation cover, and green spaces, and with the high level of maintenance, preservation, and the prevention of vandalism. Residents, including women, men, the youth, elderly, and children, confirmed that Al Asmarat’s public spaces provided complete psychological satisfaction. Most participants confirmed they were not optimistic that housing could provide them with this standard of living.

Group 8 consisted of a small family, and the father, a retired man in his seventies, spoke about his story of moving out of the slums, “I never imagined that the public spaces would be so solemn… We lived in areas where you all know the standard of living. When they told us we would move to a new project, I always spoke with myself (it was all an illusion). Until now, I did not imagine I would complete my life at this level,” “We feel good about public places and enjoy the availability of urban spaces.” His son, a young man in his thirties, said, “Praise be to God, this luxurious standard of living is a blessing from God… “Thank you to everyone who allowed me to live my youth in this wonderful place.” His sister, a young woman, said, “The open spaces compensated for my economic inability to meet friends at home… We identified all our preferences and more than our needs.”

In addition to the public spaces between residences, there are different public spaces around mosques and churches, green spaces, and many sports fields. Most residents emphasized that vegetation cover and the pavement materials contribute to a sense of self-importance. A Group 9 participant, a security employee working in a government agency said, “[…] I swear to God. My salary is not enough for me throughout the month, … just leaving the house and walking on a paved sidewalk and road, makes me feel rich, … my feelings become wild due to meeting these needs, … I am proud of this place.” His colleague from the same workplace added, “[…] All these trees, palms, and ground plants make you feel comfortable; of course, the money is significant, but there are other benefits, such as living in a clean and tidy environment.” All stories in this group focused on the fact that ‘green land,’ meaning ‘green open spaces,’ was a distant dream for them, as the informal settlements they lived in did not have a single patch of green. An elderly person who had lived in the slums their entire life said: “[…] I worked for the past five years in a gated community (the compound), … I was seeing for the first time the large open green areas and during my rest, … I was going to sit down in the green area and eat my food, … I was feeling happy. Thanks to God, I found what I always wanted in my residential area today.” A second person stated, “Could you imagine?… I saw nothing but rubbish and dirt during the last twenty years …, I live on the first floor now; when I look out the window and see all these green spaces and vastness, I feel human.” Another said, “[…] These numerous and beautiful public places enhance residents’ coexistence, and… we are not lacking now except in increasing our incomes.”

Group 10 included three women of different ages. Although the project is new and appears to be in good condition, most groups we interviewed on maintenance, preservation, and vandalism stated that public spaces are among the most important places the project management maintains. A young woman who works as a saleswoman in a shop in Mokattam remarked, “[…] it is a wonder that everything in the public spaces seems to be renewed every day, … all the plants, the furnishings, the floors, … I remember very well that I never saw any scratches in the paving or the furnishings of the place.” Her colleague, who works in another shop added, “[…] all the people here maintain the place, … you can’t see any distortion on the murals or the trespassing of plants or anything else, … we all feel that the place is our personal property, and we must preserve it like our eyes.” A forty-year-old woman working as a nurse in a government hospital indicated, “[…] I am proud to live in Al Asmarat, similar to the city of October and Sheikh Zayed.”

The results showed the existence of four issues related to spatial quality and community well-being. First, welcoming spaces encourage social integration and acceptance in society. Second, the areas’ diversity and close connection with housing, services, and other facilities achieve the most significant social and recreational benefits and promote social interaction, cohesion, and community engagement. Third, the ease of access to public spaces fairly and without compensation. Fourth, the dissimilarity of spaces at the level of the urban form relates to mental health, a sense of ownership, pride in the place, and urban aesthetic through the emerging experiences. Figure 10 summarizes a few stories from each of the ten participant groups.

Figure 10.

Selected samples of stories from each of the ten participant groups.

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussing the Results

This study used content analysis from the social sciences to identify the sociocultural dimension of urban design (SDUD), regarding the alleviation of urban poverty. It then proposed an index for examining and analyzing urban poverty related to the relevant topics. This index was used, in this study, to identify gaps in the literature. It first concerned urban planning and design articles and examined Vision 2030’s reports. It then used episodic narrative interviews and storytelling techniques to shed light on how public spaces help alleviate feelings of poverty in social housing. It was found that poverty alleviation in this type of housing is a topic that still needs to be studied. Lastly, the study developed a way for urban planners and designers to use the SDUD index’s elements as a guide.

The results of this study shed light on Vision 2030. This study addresses economic, social, and political needs quantitatively and qualitatively. In this vein, the results demonstrate the implications of incorporating or ignoring these elements have on combating poverty in Vision 2030 for the three African countries we examined. Furthermore, this vision should have specifically addressed the existence of public spaces as a component of urban form that can help alleviate poverty. This study also sheds light on the interaction between urban form and changing the living experiences of poor residents in the context of their culture and economic status.

Meanwhile, the results demonstrated that developing housing projects for people with low incomes in Egypt uses some elements of the SDUD index: indicators, principles, and criteria. The findings suggest that two key issues should be considered when developing social housing projects. First, the social dimension of urban design comprises four elements: sociocultural indicators, societal processes, urban design principles, and criteria. Second, the role of public spaces at the scale of urban form. The results also confirm our choice of integrating sociocultural indicators, processes, design principles, and criteria to build the SDUD index for measuring the role of public spaces in development projects for poor people to alleviate the feeling of poverty. It focuses on residents’ feelings of deprivation during recovery at the scale of the urban form. These updated findings are related to Vision 2030 for the three African countries explored in this paper and residents’ feelings in Egypt’s Al Asmarat Housing Project.

The analytical review of the master plan and urban form of the Al Asmarat reveals the responsible authorities’ desire not only to meet the development requirements based on the population’s needs in quantitative terms but also to contribute to the population’s well-being and social welfare. This finding correlates well with previous UN-Habitat studies on housing strategies in Egypt. According to Sims and Abdel-Fattah (2020), these projects consider sociocultural and economic dimensions. They include social justice and equity, providing economic activities along pedestrian traffic paths and public spaces, and using public spaces to practice commercial and social activities [60,88]. In addition, these communities are different and unique from an architectural point of view. The planner and designer sought to implement the ideas of a sustainable urban form, which include social and cultural integration through the availability of health, psychological, and physical facilities.

The current study’s findings go beyond what has previously been reported. They show that the population’s views on urban poverty must be prioritized within community development strategies. All the results agreed that two social factors cause poverty in social housing projects. The first indicator is spatial quality, and the second is human well-being. Previous studies have indicated that spatial quality is a relatively tricky indicator during the interview process. This issue arises because opinions are gathered from individuals who have never lived in urban communities. However, the conversation with the individuals who live in these communities confirmed that emphasizing the importance of qualitative social dimensions can also help reduce the feeling of poverty [67]. Furthermore, urban poverty is related not only to per capita income form a purely economic standpoint but also from a psychological standpoint.

Most of those classified as living below the poverty line confirmed that the spatial quality of urban forms and public spaces could alleviate feelings of poverty. This issue occurs despite life’s harshness and the necessity for money, which cannot be overlooked. Our findings agreed with those of many other studies we referred to regarding the evocation of feelings due to newly acquired experiences [78] and the equal access of all neighbors to public spaces [78]. Moreover, it reduced feelings of deprivation caused by seeing things but not being able to quickly access them [19]. In addition, they increase their sense of pride because they felt that the designs of public spaces met their daily requirements [82,83].

However, many residents had mixed feelings about finding public spaces near their homes due to their socioeconomic status, although some were enthusiastic. Our findings that most participants find that public spaces promote social interaction among neighbors, ensuring the project’s viability, agreed with the findings of previous studies [68,70,84]. So, they provide people with places with greenery [18], which enhance their mental health [78,82].

A common experience of urban poverty is a feeling of deprivation, as confirmed by most participants’ stories in the episodic narrative groups. In many stories, the results showed that the words used were related to the use of public spaces in a way that reflected “equality.” In addition, the results showed that all users could use public spaces “without financial compensation” and would, therefore, not be marginalized. On the other hand, there were many opinions on “integration”, “sticking”, “interconnectedness”, “interaction”, “acceptance of the other”, “psychological peace”, and “optimism.” Furthermore, the opinions on well-being that were among the most frequently reported were “meeting a need”, “seeing what they have not seen before”, “compensation,” “lack of financial capacity”, “a clean environment”, and “happiness.”

Most of those who participated in the dialogue did not react adversely to participating in the conversation. The participants were delighted to be relocated out of informal settlements. Investigating low-income people’s feelings on social and cultural issues from a psychological perspective without making the participants feel uncomfortable is generally an accepted practice. Among the most important goals of Vision 2030 are those for South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt.

In the future, it may be helpful to compensate people with low incomes for their lack of funds by promoting morale-lifting socio-cultural aspects. This psychological compensation may be a way of changing or improving one aspect of the development projects for people with low incomes. It may also add a new dimension to Vision 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals regarding the participation of poor people in combating poverty. Moreover, this compensation will bypass the limitations of material poverty as the only measure for combating urban poverty. The residents of this settlement enjoy many advantages that may not be found in small cities or remote places. However, the extent to which other Egyptian nationals or nationals of any other African countries can accept this kind of sharing of empathy is still being determined. Therefore, it still needs to be clarified whether urban spaces reduce the feeling of poverty in all the developing countries of the south of the world or whether they are linked to the Asmara project because it is in the capital of Egypt, Cairo.

At this stage of understanding, this study represents the start, not the end of this research, and these results cannot be assumed to be true without further examination. This fact may raise concerns about discussing the phenomenon of “the alleviation of feelings of poverty”, only through the role of public spaces in social housing projects, which can be addressed by expanding urban design studies to several spatiotemporal contexts. Public places are part of the urban fabric, where daily life experiences occur. Their existence can assist in reducing feelings of poverty for people from different social and economic backgrounds, neighborhoods, and neighborhood units. Building facades, pedestrian movement paths, squares, intersection points, and interspaces were not included in the current study.

6.2. Comparison with Prior Studies

This study’s approach is not intended to infringe on economic thought but rather to emphasize that “urban poverty” may not be best measured only by income, nutrition, or access to medication. Instead, it also focuses on the deprivation of the necessities of life. Poverty can also occur when an individual is prevented from walking, enjoying a movie in a theatre, or listening to music in an urban space. Along these lines, Pan and Pafka (2021) argue that the spatial aggregation of creative activities plays a role in the economic engine of Melbourne, Australia. Thus, it is essential to consider the social, cultural, and spiritual indicators of poverty [22]. The need to expand the definition of “poverty” to include social, cultural, and spiritual deprivation is not to say that poverty indicators must not address the role of wealth but that the inequities in wealth often emerge together with social, cultural, and spiritual inequality. Moreover, Wang, Kwan and Hu (2020) provide an example from Nanjing, China, in which people living below the poverty line were denied access to facilities and services in an affluent neighborhood; the study described this experience of inaccessibility as an indicator of poverty [89].

Since 2015, many have called for reviewing the direction of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This is because of the ambiguity around how the UN will continue to achieve some unattainable goals. For example, “end poverty in all its forms and principles”, “universal health coverage”, “end all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere”, and “achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men [90]. The focus of those goals on urban policymaking [91]), the inappropriateness of the SDGs indicators at the local level in different contexts [92], and the excessive economic orientation of the SDGs by policymakers using multiple financial measures of sustainability [93] sparked criticism.

In short, the literature on the SDGs and Vision 2030 strongly suggests that they target a political framework and an economic environment to reduce the challenges of absolute poverty within quantifiable and qualitative limits [13,15,94]. Further study is required on activating the elements of the sociocultural dimension of urban design (SDUD) that alleviates the feeling of poverty, especially in terms of spatial quality [67,68,78] and community well-being [24,82,95].

Numerous studies on the national status quo show that the ‘safe’ limits set by economists are purely political perceptions that may not necessarily respond to intrinsic human needs [59], as in the example of Kenya [15] and South Africa [14]. Satterthwaite (2003) [96] advises that although statistics on urban poverty levels are available, there is a significant lack of primary data related to the physical state of cities [96]. Despite the implementation of SDGs in 2016, many researchers consider their performance to be a failure from a human rights perspective [91,97]. Taubenböck and Wurm (2018) [98] have argued that little research has been directed toward the physical and morphological structures of urban areas [98]. In this regard, Valencia et al. (2019) demonstrated that many of the SDGs—especially those that address topics such as poverty, hunger, sustainable growth, and industrialization—have been inspired by economic perspectives [92]. According to Parker (2019), reflecting on his meeting with members of the Global Future Council, he stated that Vision 2030 hoped to harness unprecedented technological change to eradicate poverty and hunger and normalize positive well-being [99]. In addition, Baquedano et al. (2020) addresses the link between poverty and food insecurity based on the income index [11].

Previous findings emphasized the importance of Vision 2030 by understanding poverty in a way that goes beyond just improving daily income. Moreover, previous studies confirm that the psychological factor is one of the considerations that should be addressed to achieve equality and address social deprivation/exclusion [2,78,82]. Concerning social housing projects, the results demonstrated that the role of high-quality public spaces that serve the needs of recreation, exercise, and playing sports, and also increase morale, which is a positive effect culture and art have on people, becomes clear when there is a high degree of psychological satisfaction. However, activating the positive effects of public spaces alone is insufficient to alleviate the feelings of urban poverty, as the economic aspect, from the point of view of the residents of social housing, is more important than the psychological aspect. The psychological aspect can be relied upon to achieve equality and equal accessibility, and reduce social deprivation and exclusion.

The more profound point here is that a good city provides a wide range of public spaces that everyone can enter; hence, city planners and policymakers must configure public spaces to help the public flourish without charge. Along these lines, Bodnar (2015) reminds us that we need to design [for] those [who] are marginalized [100]. On the other hand, Sengupta (2017) and Wael et al. (2022) warns of the pitfalls of public spaces, as demonstrated in the example of Tundikhel, Kathmandu in Nepal and Ramses Square, Cairo in Egypt whose public spaces are not friendly to the public and were created to serve the “publicness” agenda of the state’s institutional machinery [101,102].

6.3. The Proposed Conceptual Framework

The elements of the SDUD index can explore how much of a difference in public spaces can make in alleviating poverty-related feelings. Figure 11 illustrates a proposed conceptual framework to derive benefits from the elements of the SDUD index in urban policy at the national and local levels. This framework includes four phases and seven steps.

Figure 11.

The proposed conceptual framework.

Phase one of the study involves defining the elements of the SDUD index through the literature on the meaning of urban poverty. The first step is to define urban poverty as an absolute and situational concept and to understand how to explore the elements of the social dimension of urban design through the literature related to urban form and urban poverty. The third step, which is in the second phase, is to verify these elements and the fourth step is to build the SDUD index to examine the role of public spaces. Phase three focuses through the last two steps on exploring the role of public spaces for poor residents in several pilot projects using the SDUD index through content analysis of Vision 2030 and episodic narrative interviews based on storytelling techniques. Step five is applying these findings to many countries and alternative projects and choosing the positive and negative aspects that are to be implemented in social housing. By following these steps, designers can determine what elements and designs to select to alleviate poverty and develop national and local guidelines. Policymakers can use the set guidelines to assess the scale of cities and social housing. These guidelines can also be developed to be used in cities in developing countries.

6.4. Study Limitations

Achieving good results requires reviewing most of the visions developed by the poorest countries of the Global South. The current study’s limitations include its reliance in exploring the elements of the SDUD index in Vision 2030 for three African countries and a single Egyptian development project. Moreover, more development projects in several African countries should be listed in future studies. Using older methods of recording the results of episodic narrative interviews and storytelling techniques is also a limitation. To obtain as many “resident” comments as possible, we should compare them and choose the most similar statistical methods, using the latest methods and techniques to collect their views.

It is essential to highlight that the World Bank (2018) estimates that an individual must earn at least USD 1.25 daily to live above the global poverty line. However, in many parts of the world, not even one meal can be purchased with this amount of money, let alone enable an individual to achieve physical and emotional satisfaction. Therefore, this study asserts that societal rampages and violence, such as the recent rise in international political unrest related to growing wealth inequalities and the class disparity between the poor and wealthy, will not be corrected by eliminating the hunger of the poor. Instead, when creating development projects for low-income people, it is more important to consider the SDUD index’s elements, such as spatial equity, deprivation, self-sufficiency, quality, and social resilience.

Life is a blessing that should be experienced by human beings in all its splendor and joy. No one’s income should be enough only for subsistence. Life does not become safe, stable, and worthy of living unless there is moral, social, cultural, and spiritual well-being, which goes beyond only having crumbs to satisfy hunger. Are a few dollars alone enough to live above the poverty line? Or should we also think that being unable to listen to Vivaldi’s music or read Hamlet by Shakespeare is a sign of poverty?