Abstract

Sustainable manufacturing is essential for boosting resource allocation efficiency, as well as sustainable economic development, while the construction industry is one of the main sectors affecting it. However, the complexity of multidisciplinary integration of sustainable manufacturing makes it challenging to fully integrate into architectural design teaching. By incorporating architectural design competitions in architectural design teaching, we can encourage students to systematically reflect on the role of elements beyond traditional architectural design during the architectural design process to help them gain a more comprehensive understanding of sustainable manufacturing. The research results were obtained with a combination of both qualitative and quantitative analysis. We analyzed the survey data through grounded theory and presented the results graphically, which include a framework for promoting the learning of sustainable manufacturing through architectural design competitions in teaching architectural design. In order to gain an in-depth and comprehensive understanding of the teaching effect and to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the results, in addition to qualitative analysis, we also adopted statistical analysis to clarify whether the new teaching method is really effective. In evaluating whether there was a statistically significant difference in the understanding of sustainable manufacturing between students who participated in architectural design competitions and those who did not, according to the established teaching objectives, we found that a statistically significant difference did exist in the results, and further analyzed other contributing factors through regression analysis. Our research shows that introducing architectural design competitions into architectural design teaching is a feasible way to promote students’ understanding of sustainable manufacturing. In architectural design competitions, sustainable-manufacturing-related elements, such as resources and economy, were taken into consideration in line with various design elements, such as site, environment, ecology, and energy consumption, which were integrated into students’ design process of thinking, drawing, modeling, and presenting. In this way, students will have a clearer understanding of approaches to achieve sustainable manufacturing through architectural design. This research helps tap into the value and potential of architectural design competitions in delivering sustainable manufacturing during architecture education and can offer references for college teachers to conduct sustainability education.

1. Introduction

Sustainable manufacturing is characterized by the synergy between resources, ecology, economy, culture, and society [1,2,3,4,5]. It can promote optimization in industrial structures and balance economic growth with population expansion, environmental protection, and efficient resource extraction and allocation to place economic growth on a sustainable trajectory. It can also significantly and profoundly influence energy use, industrial development, the development and use of building materials, and the expansion of tourism and cultural activities [6,7,8]. The development of sustainable manufacturing prioritizes coordinated development to balance the three elements of population, resources, and environment with the three systems of ecology, economy, and society by attending to resource use and the carrying capacity of the environment to ensure that interactions between industrial development, resource utilization, and the natural environment are benign, sustainable, and optimal [9,10].

Sustainable manufacturing and sustainable development show common traits, and their mutual aim is to achieve shared goals by following the two fundamental principles of sustainability and equity through coordinated industrial development, protection of the natural environment, and guided social development. The development of sustainable manufacturing has unique characteristics as it is a product of the social division of labor and a set of corporate economic activities that have similar features. It must follow fundamental laws of industrial development and maintain appropriate allocations of resources across different industries and ensure good economic relationships between different enterprises in order to continually upgrade industrial structures. As both technology and society have developed, industries have increasingly valued sustainable manufacturing. The energy-intensive construction industry, which is often perceived to be an obstacle to the implementation of sustainable manufacturing [5,11,12,13], has extensive demands for natural resources and building materials [14,15,16,17,18], and it is responsible for prolific energy waste, environmental disruption, air pollution emissions, waste material production, and noise pollution.

Although the construction sector has a remarkable influence on sustainable manufacturing, the relationships between participants are complex. This complexity presents many obstacles to incorporating the concept of sustainable manufacturing into the teaching of architectural design [5,19]. Competitions, if included in curricula, can be effective vehicles for learning sustainable manufacturing [5,20]. Architectural design competitions have been held at many universities around the world. Well-known competitions include the Solar Decathlon, the UIA-HYP CUP International Student Competition in Architectural Design, the JDC-International Student Competition in Architectural Design, and the International Solar Building Design Competition. Although those broadly themed competitions, which are held in various formats, have gained the attention of architectural educators and researchers, the concept of an architectural competition as a learning technique is not incorporated into architectural design teaching [21,22,23].

In cases where teaching architectural design is divorced from teaching through architectural design competitions, the potential to promote sustainable manufacturing has been unfulfilled. The separation makes it difficult to introduce the concept of sustainable manufacturing as fundamental to the entire process of architectural design construction and introduces several problems for educators. For example, senior students majoring in architecture do not adequately understand the interactions and interdependence between architectural elements, such as form, environment, materials, technology, resources, culture, economy, and society. Thus, they cannot possess a thorough understanding of sustainable manufacturing based on holistic and systematic thinking. When applying their concepts and knowledge, they will, perhaps unconsciously, regard these elements as additional constraints on their designs rather than incorporating them into the architectural design process when exploring space, form, structure, and materials, as specified in the design standards, from the very beginning of a project, whether consciously or habitually. If students have an inadequate or incomplete understanding of sustainable manufacturing, their incorporation of it in architectural designs will be one-sided or inappropriate; the designs will not solve certain problems, and this ignorance will handicap their future careers as architects [5]. Architectural teaching can positively promote sustainable manufacturing, and in educating students, it is therefore necessary to develop the concept of sustainable manufacturing through architectural design competitions.

This thesis discusses the architectural design teaching method that Zhejiang University Of Science And Technology (ZUST) has conducted in conjunction with architectural design competitions over the years. The teaching method, which is committed to utilizing architectural design competitions as a style of architectural teaching that imparts the concept of sustainable manufacturing, seeks to further students’ understanding of sustainable manufacturing and strengthen the role of architectural design in making manufacturing more sustainable. Considering the great complexity and uncertainty of architectural design in architectural design competitions, and in order to avoid hindering students’ creativity when designing architectural space and architectural forms, we have not formulated a rigid architectural design teaching framework but a flexible one, centered around the different stages of architectural design competitions by delineating different factors in sustainable manufacturing. In doing so, a flexible method for teaching sustainable manufacturing has been created so that we can guide students to be aware and understand the meaning of sustainable manufacturing, thus helping them put the idea into practice in architectural design. This study is conducive for clarifying the role of architectural design competitions in promoting sustainable manufacturing, integrating sustainable manufacturing into architectural design teaching, and providing references for architectural educators and researchers for imparting the concept of sustainable manufacturing in architectural design.

2. Literature Review

Over the past 20 years, an increasing number of architectural design competitions have emerged. Well-known ones include the Solar Decathlon, UIA-HYP CUP International Student Competition In Architectural Design, JDC-International Student Competition In Architectural Design, and International Solar Building Design Competition. Their themes related to sustainable manufacturing are presented in Table 1. Accompanying the emerging architectural design competitions are a growing number of architectural educators and researchers who are beginning to pay heed to the role and value of architectural design competitions in architectural design teaching and sustainable manufacturing as a whole. Some studies have shown that competitions such as the Solar Decathlon can link sustainable manufacturing to many aspects of architectural design teaching [21,24], such as functional architectural design, site planning, energy use, construction, material applications, and new technology applications [25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. In addition, competition goals are also closely related to sustainable manufacturing, including the following: (i) encouraging professionals to minimize their buildings’ impact on the environment by applying superior materials and techniques; and (ii) popularizing renewable energy, energy efficiency, responsible energy use, and available technologies to the public [26]. Some studies show that architectural design competitions can become a platform for learning about green building, energy, analysis tools for energy consumption, and innovative applications for energy-saving technologies [21,32,33,34], involving energy efficiency, electric loads, solar energy supply, and electric energy balance [24], offering the required performance indicators, experimental data, and demonstration cases for solving problems in the architectural sciences [24,34,35,36,37].

Table 1.

Competition Themes Related to Sustainable Manufacturing.

Although architectural design competitions have garnered extensive attention from architectural educators and researchers, there are insufficient teaching-oriented studies that explore the role of architectural design competitions in promoting sustainable manufacturing. Many other studies have indicated that the concept of sustainable architecture should be integrated into architectural design teaching [32,38,39,40], but due to the limitations on class hours, teaching objectives, and the complexity of architectural design assignments, this integration in traditional architectural design courses lacks effective means and supporting scenarios. Some studies have explored the role of architectural design competitions in promoting sustainability education, but a lack of analysis exists on how to do so through architectural design competitions in architectural design teaching as a whole. The aforementioned circumstances are not conducive to the concept of sustainable manufacturing being fully integrated into architectural design teaching. In fact, with the help of the scenes and atmosphere created through simulated architectural design practices in the competitions, the connection between architectural design and sustainable manufacturing increases and becomes notable through the process of “industry-resources-material” transformation. Because manufacturing can be expanded to cultural and economic fields, the significance of sustainable manufacturing being integrated into architectural design teaching will continue to spread to society at large, which means the teaching effect will also become more prominent. It looks to be more comprehensive and far-reaching than sustainable architectural education that only focuses on saving materials and energy and reducing pollution. Overall, it is necessary to try to integrate the concept of sustainable manufacturing into architectural design teaching through architectural design competitions to bridge the gap between architectural design teaching and sustainable manufacturing.

3. Find a Flexible Method for Teaching Sustainable Manufacturing through Architectural Design Competitions

3.1. Teaching Cases

ZUST is renowned for cultivating application-oriented talent across mainland China. Its architecture major has adopted a five-year academic program that is widely emulated in Asian universities. Since 2018, ZUST has incorporated sustainable manufacturing into junior and senior architectural design courses through architectural design competitions. Four Zhejiang Rural Revitalization Competitions have been held to date, with the aim of innovatively boosting sustainable development in rural areas of China (see Table 2 for competition themes over the years) by involving industries related to rural culture, tourism, and social services. Since the first competition, over 100 ZUST students have participated and won accolades. The students guided by our team guided won nine gold, six silver, and five bronze awards since the competition started (Table 3 shows more award winners and their stories). Based on our teaching and experience over the past four years, we summarized a set of teaching methods that incorporate sustainable manufacturing into architectural design courses through architectural design competitions. Architectural design competitions prioritize innovative architectural designs that require inspiration and creativity, so the design process we developed is not followed rigidly, and randomness and uncertainty are always present. This teaching method therefore does not strictly adhere to a set framework to teach sustainable manufacturing. Instead, it is a flexible method for teaching sustainable manufacturing that can be adjusted within certain parameters.

Table 2.

Previous Themes of Zhejiang College Students Rural Revitalization Creative Competition.

Table 3.

Representative Award-winning Cases in the Zhejiang Rural Revitalization Competition Guided by Our Team.

We combined our analysis of the theme and requirements of the Zhejiang Rural Revitalization Competition and our understanding of sustainable manufacturing in formulating key nodes common to the architectural design stages for competitions and for teaching sustainable manufacturing. The architectural design stages and key nodes are identified in the flexible method. We divided the flexible method into four stages: research, categorizing research material, developing architectural designs, and building architectural models. We separated the key nodes into three categories: locality, materiality, and physicality. The relationship between the stages and key nodes is one–many rather than one–one, which means that a stage can involve two or three key nodes. Likewise, the stage in which a key node sits is not fixed and can be adjusted according to the needs of the designer. Although the architectural design stages we adopted seem traditional in terms of formal architecture teaching, they have characteristics that are clearly related to architectural practices. The entire method used to compete in the competition is determined by the key nodes and is variable and diverse. It should also be noted that the key nodes are critical within the flexible method because they are points at which sustainable manufacturing incorporated in the method intersects with architectural design. The nodes can also be considered as translating the architectural language of the architectural designs that are responses to the Zhejiang Rural Revitalization Competition to boost sustainable manufacturing. We now describe in more detail the flexible method for teaching sustainable manufacturing around key nodes.

3.2. The First Key Node: Locality

Locality focuses on the connections between architectural design and the site environment and landform. We required students to fully understand the natural environment, topography, and local customs around the site and to act in accordance with sustainable principles to keep the original site intact and to produce designs that fully utilize elements of the site, such as any original height differences, rivers, and vegetation.

Locality usually involves three design stages: research, categorizing research materials, and developing architectural designs. We used two research techniques in the first stage: an on-site survey and visits with local villagers living near the site. The survey gave us a clearer picture of the characteristics inherent to the natural topography of the site and village size, thus providing a foundation for incorporating locality into architectural designs. The visits with villagers allowed us to identify and understand the composition, lifestyles, and actual needs of the population, together with the industrial structure and special resources of the site, along with its human-related characteristics. The research provided reference material for incorporating locality into architectural designs in the contexts of sustainable manufacturing development and regional culture. We then analyzed all research data and summarized the characteristics of different types of data to provide guidance incorporating locality into the architectural design. In developing the architectural design, we elucidated specific strategies for the design to ensure locality through analysis of the spatial scale, form, and function of the construction.

3.3. The Second Key Node: Materiality

Materiality refers to the selection of locally sourced materials available for the architectural design process. In previous competitions, we used locally sourced materials for architectural designs as much as possible, including stone, wood, bamboo, and broken tiles. This approach ensures that local materials are used wherever possible in architectural designs and helps students to familiarize themselves with the local industrial chain.

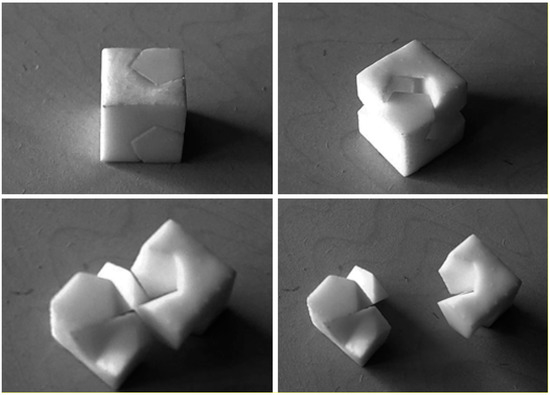

Materiality usually involves three design stages: research, categorizing research materials, and developing architectural designs, and sometimes involves building architectural models. In research, our goal was to explore and understand materials that have potential use in architectural designs and to catalog them by conducting on-site surveys and visiting villagers. The catalog includes both renewable materials and recyclable materials that have been neglected but which highlight local cultural values. In categorizing the research, we analyzed the research data and compared textures, examined environmental protection, and assessed the difficulty of using different materials to narrow the range of available materials. We selected some as key objects until the initial selection of material for use was completed. In addition, we summarized the state of the local industrial chain with respect to processing selected materials as we attempted to use locally processed materials. We considered the possibility of using the selected materials as objects of utility and cultural and creative products and how much cultural value and economic effects are accrued from their use. This is a sophisticated way of thinking about sustainable manufacturing and energizes the local industrial chain. We required students, in developing architectural designs, to relate closely to materials through the stages of conception, preliminary scheme design, and design model making (two-dimensional and three-dimensional models) and to be capable of having better command of materials in architectural design and subsequent construction.

3.4. The Third Key Node: Physicality

Physicality refers to emphasizing the connection between the architectural design and actual construction. Although a competition does not require the architectural design to be actualized, we still emphasize the materialization of an architectural design. We believe that emphasis on constructability in architectural design promotes sustainable manufacturing and prevents the conceptualization and design exercise from becoming an empty gesture.

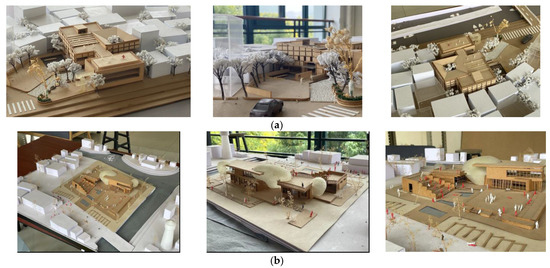

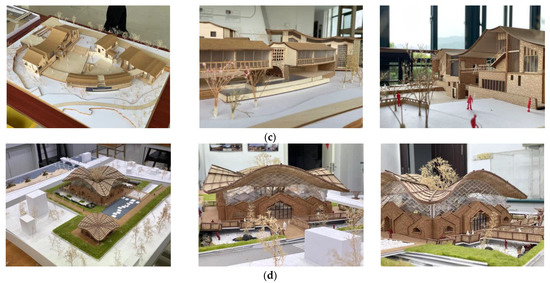

We usually approach physicality from two directions: developing architectural designs and creating architectural models. In developing designs, we guide students to an architectural design studio to learn from experienced architects, which is a far cry from having them attend a traditional architectural design class. Architects will offer suggestions from a professional point of view and cover construction, sustainable manufacturing, ecology and environmental protection, and energy conservation in architectural designs. This experience allows students to learn about the real-life challenges they will encounter when implementing architectural designs and enables them to reflect on their shortcomings, as well as ways to improve them. In creating models, apart from computer models, students constructed a 1:100 physical model (Figure 1) made from the components specified in the design (Figure 2). The physical model can make up for the lack of realism inherent in the virtual model, which helps students to improve architectural designs and helps them to marry the architectural design with what will be constructed.

Figure 1.

1:100 physical model. Notes: (a) the physical model of award-winning case called Stream Bank Leisure Spot in Gushi Town; (b) the physical model of award-winning case called Silkworm Culture Center; (c) the physical model of award-winning case called Empowering Shuiting She Ethnic Township; (d) and the physical model of award-winning case called Byte Dancing under the Bamboo Hat.

Figure 2.

The physical model of the components specified in the award-winning case called City on the Stems of Plants.

4. Research Methods

Because this teaching research lacks directly applicable theories, we adopted grounded theory as the research method to analyze the interview data for the following reasons. First, given the aforementioned context, grounded theory can compensate for the lack of depth and validity of traditional qualitative research and quantitative research to a certain extent by exploring theories from raw data. Second, it is highly applicable in causal identification, process interpretation, and new factor exploration, all of which are conducive with the characteristics of this teaching research. Third, studies have shown that for teaching, qualitative analysis proves to be more effective than quantitative analysis in analyzing problems [41].

To gain a full picture of the teaching effect and to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the research results, we applied statistical analysis in addition to grounded theory, which means the research combines both qualitative and quantitative analyses. This method has been utilized in research on the challenges facing architectural education [9,42], and the two types of analyses are complementary. Qualitative analysis based on grounded theory shifts toward the macro level and is designed to reveal the characteristics and internal connections of architectural design teaching and architectural design competitions when promoting the learning of sustainable manufacturing to formulate a new teaching theory of architectural design integrated with sustainable manufacturing. Quantitative analysis based on statistical analysis focuses on the micro level, which aims to clarify whether architectural design teaching of sustainable manufacturing through architectural design competitions is truly effective or not.

4.1. Qualitative Analysis Method Based on Grounded Theory

To understand how much students have learned about sustainable manufacturing, we conducted interviews with twenty-eight participants in architectural design competitions, including three sophomores, ten juniors, six seniors, five fifth graders, and four graduates, among whom eight students participated in two competitions in different years. The number of interviews met the requirement that the sample size of qualitative research is generally controlled between 20 and 30 [43].

We asked ten questions about architectural design competitions and sustainable manufacturing (Table 4). To facilitate the interview and obtain more true and objective data, we informed the students of the purpose and precautions of the interview prior to the interview and emphasized the requirement for them to express their true feelings. The interview lasted about two to three hours for each student. We recorded the interviews, which were checked and reviewed in a timely manner. If anything was unclear, we asked the interviewee for confirmation via phone or message. We followed the steps of grounded theory. First, we performed primary coding on the interview data, namely open coding. To ensure the analysis was accurate, open coding was conducted in a sentence-by-sentence coding manner (Table 5). On the basis of reading and arranging the interview data, we streamlined and refined words or sentences according to three coding levels, namely labeling (the coding prefix is marked with the letter “a”); initial conceptualization (the coding prefix is marked with the letter “A”); and core conceptualization (the coding prefix is marked with the letter “AA”), and obtained 36 core concepts (Table 5). We then proceeded to the second step: axial coding. According to the “condition-strategy-result-paradigm” model, we classified, compared, and organized the 36 core concepts obtained through open coding based on four aspects, to find out the logical and category relationship between the core concepts, which resulted in bringing that number down to six main categories (Table 6). The third step was selective coding. From the detailed analysis of the six categories obtained in the axial coding, we settled on two core categories and sorted out their connections with the core concepts and main categories through the paradigm model and presented the entire study around the “storyline” of two core categories (Table 6).

Table 4.

Interview outline.

Table 5.

The process of open coding.

Table 6.

The result of selective coding.

To ensure the quality of the research, we performed a theoretical saturation test on the codes. We coded the interview data of the reserved nine students (about one-third of the total) and discovered that no new categories were generated. We therefore deemed the theory constructed in the research saturated. In addition, we invited scholars and experts in the field to review the preliminary findings of the research and make recommendations on the findings.

4.2. Quantitative Analysis Method Based on Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of this study is targeted at the teaching effect of sustainable manufacturing with the flexible method. Considering the fact that Bloom’s taxonomy can reveal students’ cognitive level, we also adopted the method to formulate teaching objectives. As a tool for evaluating teaching objectives, Bloom’s taxonomy can reflect the relationship between acquiring knowledge and ability development in terms of the knowledge dimension and the cognitive dimension, which includes six aspects: memory, comprehension, application, analysis, evaluation, and creation, and each of them contains different sub-categories [44]. We primarily analyzed teaching according to the taxonomy of the cognitive dimension and its sub-categories, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Teaching Objectives Formulated in Combination with Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Through questionnaires, we examined how well those teaching objectives were achieved to evaluate the teaching effect of sustainable manufacturing. We associated the teaching objectives with the items from the mature scale [45,46] used to evaluate teaching effects, and finally determined 16 questions to evaluate the teaching effects (Table 8) after testing and optimizing. More specifically, through the 16 questions, we measured how well those teaching objectives were achieved (for example, Teaching Objective 1.1 was measured by Question 1; Teaching Objective 3.2 by Question 4). The fundamental idea of evaluating the teaching effect is that according to the intended teaching objectives, we evaluated whether there is a statistically significant difference in the understanding of sustainable manufacturing between the students who participated in architectural design competitions and the students who did not; if there is one, regression analysis is applied to further analyze the factors that affect the understanding of sustainable manufacturing.

Table 8.

Survey Questions for Evaluating Teaching Effects.

Different from the sample size required for conducting in-depth interviews based on grounded theory, the survey required more students who participated in architectural design competitions as the research sample. To improve data quality, the survey was anonymous. Furthermore, to reduce possible common method bias, we collected data over two rounds at three-week intervals. At time 1, questionnaires were distributed to 230 students. Specifically, we briefly introduced the purpose of this research in the introduction part of the questionnaire, and then we invited students to fill in the three items regarding how many times they participated in competitions, how many times they conducted field research, and how many times they made models, with variables controlled. After this round of the survey, we sifted the questionnaires and finally obtained 221 valid ones, with a valid response rate of 96.1%. At time 2, we sent new questionnaires to the previous 221 valid respondents at time 1 and asked them to score the teaching effects of sustainable manufacturing. At the end of this round, we received 216 valid questionnaires, with a valid response rate of 97.7%. In the final sample (216 students), the majority of respondents were male (63.00%); and the largest proportion of students were 23 years old (30.60%); those in the fifth year accounted for the most of the respondents (27.30%); 40.70% of the students took the course for the first time in the second year; 28.7% of the students learned about one sustainable manufacturing theory before taking the course; and 109 students participated in architectural design competitions while 107 did not, which means the number of participants and non-participants in design competitions was comparable.

We divided the 109 respondents who participated in architectural design competitions and the 107 students who did not into the experimental group (Group A) and the control group (Group B), respectively. Through T-testing, we examined whether there was a statistically significant difference between the experimental group and the control group in terms of the teaching effect of sustainable manufacturing. When p < 0.05, it means that there is one.

If it does exist, regression analysis is applied to determine the factors that affect the perception of sustainable manufacturing. Because the teaching included the adoption of the flexible method for teaching sustainable manufacturing, we inferred that the contributing factors are not only related to the number of times students participated in architectural design competitions, but also related to the three key nodes of locality, materiality, and physicality. Based on the aforementioned analysis and existing research on teaching effect evaluations [9,42,47,48], we made the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

The number of competition participation times was positively related to the teaching effect evaluation.

Hypothesis 2.

The number of field research times was positively related to the teaching effect evaluation.

Hypothesis 3.

The number of model making times was positively related to the teaching effect evaluation.

X1. the number of competition participation times was measured with a single item: “How many times have you attended a course that was integrated into architectural design competitions?” (1 = 0 time; 2 = 1 time; 3 = 2 times; 4 = 3 times; 5 = 4 times; 6 = 5 times and above).

X2. the number of field research times was measured with a single item: “How many times have you participated in field research on the site design?” (1 = 0 time; 2 = 1 time; 3 = 2 times; 4 = 3 times; 5 = 4 times; 6 = 5 times and above).

X3. the number of model making times was measured with a single item: “How many times have you participated in creating mock-ups?” (1 = 0 time; 2 = 1 time; 3 = 2 times; 4 = 3 times; 5 = 4 times; 6 = 5 times and above).

Y. We tested the teaching effect of sustainable manufacturing through an adapted 16-item scale. We used a five-point Likert scale in the survey (1 = “strongly disagree”, 5 = “strongly agree”). Sample items included “In the teaching of architectural design, teachers explicitly demonstrated knowledge of sustainable manufacturing” and “In the teaching of architectural design, teachers clearly presented methods for achieving sustainable manufacturing through architectural design competitions”. The Cronbach’s alpha of this measurement instrument was 0.973.

Control variables. According to existing research on teaching effect evaluations [47], we controlled for factors that may have influenced this research, such as the age, gender, current grade of the student, the grade when the student first participated in relevant competitions, and the amount of sustainable manufacturing theories students learned before taking the course.

5. Results

The research results were obtained with a combination of qualitative analysis and quantitative analysis. First, the findings of the qualitative analysis were presented graphically, which included a framework for promoting sustainable manufacturing learning through architectural design competitions in teaching architectural design. Second, the findings of the quantitative analysis were displayed as follows. Finally, the thesis briefly discussed how the quantitative analysis findings relate to this framework to promote sustainable manufacturing learning.

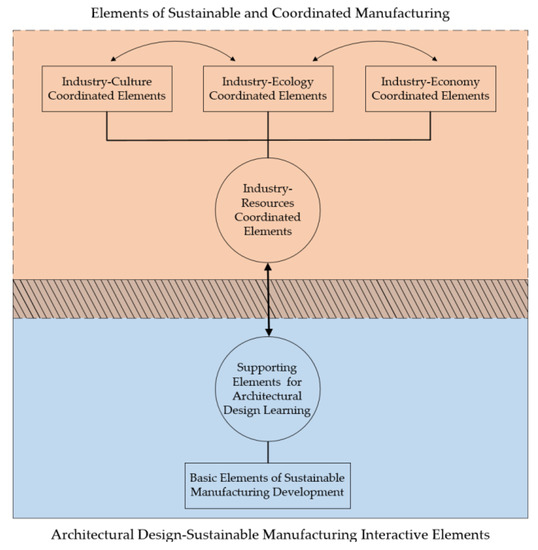

5.1. Research Results of Qualitative Analysis

We present the research results graphically, which is consistent with the requirements of grounded theory to present research findings graphically [49]. Around the categories established in the coding stage, we developed a framework for promoting sustainable manufacturing learning through architectural design competitions in architectural design teaching (Figure 3). The framework consists of interactive elements of “architectural design-sustainable manufacturing” and coordinated development elements of sustainable manufacturing. The former includes the basic elements of sustainable manufacturing development and the supporting elements for architectural design learning. The latter covers the four main categories of coordinated elements: “industry-resource”; “industry-ecology”; “industry-culture”; and “industry-economy”. Overall, the two core categories in the framework intersect with each other, and the main categories form a T-shaped structure. Partially, in this structure, the basic elements of sustainable manufacturing development at the bottom constitute the cornerstone of the structure, providing a logical and theoretical basis for students to learn, understand, and realize sustainable manufacturing during architectural design competitions. In the middle of the T-shaped structure lie supporting elements for architectural design learning and “industry-resource” coordinated elements. This place also marks the intersection of “architectural design-sustainable manufacturing” interactive elements and coordinated development elements for sustainable manufacturing, forming the core of the entire structure and serving as a bridge between those two kinds of elements. Specifically, the former offers internalized knowledge and concepts for students to learn, understand, and realize sustainable manufacturing in architectural design competitions, while the latter, based on relatively direct observables, provides students with operational means to achieve sustainable manufacturing. On the top of the structure sit coordinated elements of “industry-ecology”, “industry-culture”, and “industry-economy”, which form the structure’s roof. This is related to students’ direction, goals (including short-term, mid-term, and long-term goals), and results of achieving sustainable manufacturing. It is also a reflection of students’ understanding and realization of sustainable manufacturing through architectural design throughout the competition. Among them, the “industry-ecology” coordinated elements play a key role in maintaining a balance on top and promoting long-term balanced development of culture and economy in the industrial system. The different elements interact and promote each other, which constitute a complex system for learning sustainable manufacturing through architectural design competitions in architectural design teaching.

Figure 3.

A framework for promoting sustainable manufacturing learning through architectural design competitions in architectural design teaching.

5.2. Research Results of Quantitative Analysis

Through T-testing, we found the evaluation of the teaching effect of sustainable manufacturing between Group A and Group B showed statistically significant differences (t = 16.697, p = 0.000 < 0.05; Table 9), and the average score of Group A was higher than that of Group B in terms of the 16 questions. This shows that Group A exhibited a better evaluation of the teaching effect and fared well in completing the intended teaching objectives.

Table 9.

T-testing.

Because there was a statistically significant difference in the perception of sustainable manufacturing between Group A and B, we further analyzed the contributing factors through regression analysis.

- (1)

- Descriptive statistics

Table 10 shows the correction matrix and descriptive statistics for all variables in this study. Overall, these zero-order correlations indicated that the number of competition participation times was positively related to the teaching effect evaluation; the number of field research times was positively related to the teaching effect evaluation; and the number of model making times was positively related to the teaching effect evaluation. These results are consistent with the hypotheses of this study and provide preliminary evidence for the validation of the research hypotheses.

Table 10.

Descriptive statistics.

- (2)

- Hypotheses testing

We then calculated variance inflation factors to test for multicollinearity among the independent variables and found that they were all below the critical value of 10 [50], indicating that multicollinearity is not a serious problem.

Table 11 shows the results of the regression analysis. Hypothesis 1 predicted a positive relationship between competition participation times and the teaching effect evaluation. In line with this hypothesis, competition participation times were found to have a significant positive impact on the teaching effect evaluation (β = 0.489; p ≤ 0.01). Consequently, when students participate in more competitions, the better the teaching effect evaluation is. Hypothesis 2 expected a positive impact of field research times on the teaching effect evaluation. In line with this hypothesis, field research times were found to have a significant positive impact on the teaching effect evaluation (β = 0.083; p ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, hypothesis 3, which expected a positive relationship between model making times and the teaching effect evaluation, was significantly supported (β = −0.096; p ≤ 0.05).

Table 11.

Results of regression tests.

In summary, the above findings suggested that the three independent variables were positively related to the teaching effect evaluation. Thus, all hypotheses of this study were supported.

5.3. Linkage of Quantitative Analysis Findings to the Framework for Promoting Sustainable Manufacturing Learning

In this thesis, qualitative analysis and quantitative analysis are complementary to each other. Qualitative analysis based on grounded theory, which focuses more on the macro level, offers a framework and process to learn sustainable manufacturing, and is conducive to obtaining new teaching theories that integrate sustainable manufacturing into architectural design teaching. In comparison, quantitative analysis based on statistical analysis, which shifts towards the micro level, enables us to understand the teaching effect of sustainable manufacturing and obtain related feedback. That said, qualitative analysis underscores the building of different layers of sustainable manufacturing learning, which not only shows where analysis results can be applied, but also offers a deeper explanation for the results. To some extent, the more times a student participates in architectural design competitions, the easier it is to obtain information on the coordinated elements of “industry-resource”, “industry-ecology”, and “industry-culture”. The same results can also be achieved through field research and mock-up creation. This helps increase the opportunities for students to understand sustainable manufacturing, making their understanding more systematic and comprehensive. By comparison, quantitative analysis focuses more on details of the learning, showcasing direct factors that affect learning at a micro level. Those factors can reflect how the concept of sustainable manufacturing is applied in a practical way. In addition, those factors are relatively closely related to the “industry-resource” coordinated element which, in fact, plays a central role in the framework to promote sustainable manufacturing learning, and which intuitively affects the learning of sustainable manufacturing from a macro level. This mutual correspondence between “micro” and “macro” illustrates the rationality of the framework obtained from qualitative analysis to promote sustainable manufacturing learning.

6. Discussion

To summarize, we obtained new findings on sustainable manufacturing in architectural design teaching.

Our findings suggest that the introduction of architectural design competitions into architectural design teaching is a feasible method to promote students’ understanding of sustainable manufacturing. Architectural design competitions present a value chain, production chain, supply chain, and commodity chain related to sustainable manufacturing that are supported by different design elements, such as site, environment, ecology, and energy consumption, and naturally integrate those elements into the students’ architectural design process of thinking, drawing, modeling, and displaying. To obtain an inventive and reasonable architectural design scheme, students not only need to have an in-depth understanding of design elements, such as the site, environment, ecology, energy consumption, culture, industry, and local productivity levels, but also need to have a thorough understanding of the backgrounds of these design elements and how they interact with one another. Architectural design competitions will not only allow students to understand sustainability from a conceptual level, but also gain first-hand experiences of what sustainable manufacturing means, analyze local industrial landscapes, and think about the logic behind and method of achieving sustainable manufacturing. In this way, architectural design can truly embrace the concept of sustainable manufacturing and become an essential part of revitalizing local industries or a key factor in reactivating local industries. This finding agrees with what some researchers have described. Hill and Smith [51] believe that in the real world, the solutions to technical problems are interactive rather than completely linear or progressive as exploring the relationship between knowledge, skills, and different materials forms the basis for technical processes. Fantozzi et al. [52] infer that architectural design competitions can bring about effects that are difficult to obtain through traditional educational approaches. Even if the participants in the SD competition did not complete the actual construction of the building, they were still convinced that the competition would have a positive impact on their architectural design experience, in-person construction experience, and saving energy practices because the competition can effectively lead to increases in students’ knowledge, skills and awareness in architectural conceptual designs, construction, green building designs, energy conservation and emission reduction, and sustainable development by exposing those participants directly to concrete problems that occur in the processes of engineering construction, energy production, and social progress. Herrera-Limones et al. [32] argue that the competition provides an effective platform for the production and dissemination of sustainability knowledge. The platform is conducive to the future career development of architecture students because it helped students fully integrate energy-efficiency technologies, material ecology, construction economy, and other factors related to sustainable manufacturing into the architectural design process. Research from Baghi et al. [21] reflects that the SD competition is still key to deepening students’ understanding of sustainable manufacturing, especially across the three aspects of architectural design, resources (including equipment and materials), and ecology. He believes that in the SD competition, the most important innovations are concentrated within two aspects. One is the application of HVAC, architectural design, and construction equipment to different lifestyles and different climatic conditions, and the other is the the integration of building materials and various functional features into the main structure of the building. Additionally, some studies have shown that architectural design competitions provide an opportunity to verify the effectiveness of new technologies for solving problems, such as high energy consumption and carbon emissions [24,32,34,53]. It is unavoidable for teams participating in the competition to take sustainable manufacturing into consideration when they apply new technologies in the field [24,53]. If a new technology proves to be energy efficient, but its production and transportation process consume a large amount of energy and produce a significant amount of pollution, coupled with insufficient output and an immature market, it cannot be used in construction when emission reduction, product supply, and market acceptance of the full life cycle of the building are considered. Because competitive architectural design competition necessitates stringent requirements for quality projects, the participating teams rigorously and scientifically analyze the role of new technologies in energy conservation and emission reduction through simulation analysis of building performance and energy consumption simulation and continue to improve the quality of their work [24]. This process enables the participating student groups to gain a deeper understanding of sustainable manufacturing, achieving the teaching effect that cannot be achieved through traditional architectural teaching methods in this domain.

Our findings also suggest that the concept of sustainable manufacturing needs to be imparted earlier on in architecture majors. This does not mean that all content should be taught during this period, but a portion of it is enough because content, such as the production chain, supply chain, industrial structure, and industrial conditions, can be seen as a supplement to lower-level architecture design courses, which focus on the environment, materials, and techniques. In the competition, students’ indifference to the idea of sustainable manufacturing, as we observed, may cause their designs not only to be divorced from local natural conditions, the human environment, and economic conditions to a certain extent, but also make it challenging to adapt them to higher standards, such as material, energy, and water savings, eco-friendly and low-carbon requirements. A better solution for this is not for teachers to emphasize or explain to students the necessity and importance of sustainable manufacturing in architectural design, but that from the very beginning of the competition, students can become accustomed to regarding the idea as an integral aspect of design. In fact, sustainable manufacturing should not be a stopgap between an ideal architectural design and a realistic one, but a bridge connecting each. Given that, students may have a clearer understanding of the approaches to solving industrial and social problems through architectural designs to better integrate designs into the environment and culture alike. This finding has been advocated by some researchers and teaching staff. Altomonte et al. [40] argue that sustainability, such as sustainable manufacturing, should be integrated into architectural education as early as possible, and it can be introduced earlier on to undergraduates, which will help raise student awareness of sustainable development from the early stage of architectural education, motivate them to cope with the challenges of sustainable development that the construction industry faces, and stimulate their creativity to solve problems hindering sustainable development, such as environmental pollution and resource overuse. Domenica Iulo et al. [54] believe that it is necessary to impart concepts and knowledge related to sustainable manufacturing in the early stages of architectural education. Earlier exposure to these concepts and knowledge enables students to have a deeper understanding in their junior or senior year, and they will be less likely to consider those ideas as constraints. Xiang et al. [55] purport that we need to set the initial starting point to integrate sustainable development concepts and knowledge into the early years of architectural design undergraduate classes to help students establish a systematic understanding of sustainable development earlier and consider architectural design issues more comprehensively. The process should be continued throughout their studies. In addition, some studies have shown that a close link exists between the concept of sustainable manufacturing, including sustainable manufacturing and the content taught in the lower grades of architecture majors [56,57,58]. Toprak’s [56] perspective considers sustainable architecture to not only be related to energy and ecology, but to also have broader meanings. It can even be considered a philosophical way of thinking, which requires designers to focus on the design details of the environment, site, and materials; to try to think about architectural designs from the aspects of architectural scale, terrain environment, energy consumption, lighting, ventilation, the industrial chain, culture, and recycling; and learn to cooperate with users, customers, engineering professionals, building materials companies, and building material manufacturers.

Our findings also suggest that the introduction of architectural design competitions into architectural design teaching can provide students with an environment (condition or learning atmosphere) where they can authentically learn about sustainable manufacturing. Compared to traditional architectural design courses, architectural design competitions not only have higher requirements for architectural design quality, achievements, and innovation, but also provide a simulated real architectural design environment and more authentic practice for students. For those participants, materials, processes, and energy consumption in sustainable manufacturing are longer technical knowledge, but a part of social-cultural factors. Based on their own knowledge and experience, students can spontaneously understand the relationship between sustainable manufacturing and architectural design, the complexity and contradictions of architectural design practices, the social responsibility of architects, and knowledge that is not presented by teachers and that is indescribable. Equipped with this knowledge, they can actively explore ways to achieve and promote sustainable manufacturing through architectural designs, forming their own unique insights into the concept. For example, when it comes to eco-friendly architectural designs, students in an immersive design environment will more clearly perceive the real economic constraints of the site, supply chain restrictions, and energy-saving needs, such as shading, heat preservation, sunlight, and ventilation. They also need to be aware of the importance and necessity of designing low-carbon buildings through technologies adapted to the local landscape features. As a matter of fact, traditional local materials and buildings have proven to be effective in promoting the low-carbon and energy-saving construction of buildings [59,60]. When students regard local traditional building materials as an important medium for energy conservation, they will not only focus on how to display local cultural characteristics using local traditional building materials, but also pay attention to how to make energy-saving designs, such as thermal insulation and heat preservation by taking advantage of traditional building materials and innovating the use of those materials. The above process, spanning from constant reflection on actions and acquisition of new knowledge to problem solving, has the characteristics of constructivism. This finding is backed up by several studies. Hill [61] argues that, regardless of the future career, a practical way of learning through in-person experience proves to be more enlightening than that through traditional lecturing in the classroom. In Hwang et al.’s [62] opinion, learning by applying can stimulate the learner’s imagination and creativity to facilitate their cognitive development and keep them motivated. In addition, it can drive the learner to consciously do more learning tasks in different practical scenarios, thereby piquing their interest in doing so in real conditions. Wallin et al. [63], based on the case of engineering education, expounded on the situation where students cooperate with teachers in research and experiential learning in small groups. They believe that authentic learning will have a positive impact on students learning knowledge and skills. These effects include the following: higher levels of engagement; real experience of what work is like; a strong motivation to learn; active participation in all stages of research; and a deeper understanding of the nature of scientific research. Lee [64] argues that contextual learning may ultimately lead to transformative learning in which students encounter difficulties triggered by authentic learning and become willing to engage in critical reflection and rational dialogue, ultimately becoming a more authentic self both in the learning environment and in the real world at large.

7. Conclusions

Based on architectural design competitions held in China over the years, this research discusses a flexible method for integrating sustainable manufacturing into architectural design teaching. This research shows that architectural design competitions can link sustainable manufacturing to multiple aspects of architectural design teaching, which will serve as a platform for acquiring knowledge about green building and energy, analysis tools of energy consumption, and innovative applications of energy-saving technologies. The research aims to pursue a flexible method to teach sustainable manufacturing through architectural design competitions, which act as a form of architectural education carrying sustainable manufacturing to promote students’ understanding of the concept, and to strengthen the role of architectural design in achieving sustainable manufacturing. Compared with traditional design teaching in classrooms, architectural design competitions create an atmosphere closer to real-life designing and construction, which do not pay lip service to the idea of conserving resources and energy, but place sustainability at the core of sustainable design. This enables students to take various factors involved in architectural design into consideration and expand architectural design teaching to cultural, economic, and other fields in a more comprehensive way, bolstering the presence of sustainability across more aspects. Thus, sustainable manufacturing can be truly integrated into architectural design teaching.

This research suggests that the key nodes of integrating sustainable manufacturing into architectural design teaching can be divided into three aspects: locality, materiality, and physicality. By integrating these key nodes in different stages of architectural design, this research develops a flexible method to promote sustainable manufacturing in architectural design teaching through architectural design competitions where the basic elements of sustainable manufacturing development and the supporting factors of architectural design teaching intersect and promote one another, constituting a complex system for learning sustainable manufacturing in that way. The success of teaching practice shows that it is a feasible way to improve students’ understanding of sustainable manufacturing. Competitions modeled on real conditions establish elements related to sustainable manufacturing as prerequisites for architectural design that requires analysis and understanding of those factors. The interaction between those elements and those of traditional designs helps students not only understand sustainability conceptually, but also reflect on the application logic of sustainable manufacturing in the site design, in which they directly confront specific problems in engineering construction, energy production, and social development. As a result, it improves students’ awareness, knowledge, and ability to put sustainable manufacturing into practice while designing, a teaching result that is difficult to achieve with traditional architectural teaching methods.

The teaching methods involved in this research can be used in various teaching modes used in architectural design based on practical teaching. They share the same basic principles to transform the teaching of architectural design from theoretical to practical. Exposed to real problems arising in designing, students translate their abstract theoretical designs into concrete ones by exploring the connections between knowledge, skills, and materials to improve their awareness and professional skills. At the same time, they can reflect on the problems of actual design conditions and receive precious feedback for their designs, especially from those outside of the campus, whether it is competition judges, house owners, civil servants, or constructors giving different opinions and suggestions in their view, which is a huge supplement to the theories learned on campus and to teachers’ obstructed views and helps them understand sustainable manufacturing from a broader perspective. To summarize, this research is helpful to the penetration of sustainable manufacturing in architectural design teaching and provides a reference for introducing interactive teaching of architectural design and sustainable manufacturing elements into sustainable architectural teaching at the undergraduate level.

A major limitation of this research is that it fails to cover the impact of differences in students’ mastery of sustainable manufacturing on teaching. In ZUST’s teaching through architectural design competitions, participants range from sophomores to seniors, among whom some junior students have no concept of sustainable manufacturing at all. However, some seniors have repeatedly participated in competitions and gained considerable experience of sustainable manufacturing theoretically and practically, compared with those who have studied relevant theoretical courses or self-studied the concept of sustainable manufacturing. Students’ different foundations have given rise to divergent learning outcomes in terms of the sustainable elements in architectural design as evidenced by their different learning speeds and levels of mastery, the details of which are not captured in this research. In our subsequent research, we will conduct interviews to understand the learning process of students with different mastery levels of sustainable manufacturing, including their gains in learning process, learning challenges, and their performances in subsequent regular architectural design courses. By analyzing the interview data according to grounded theory, we will put forward an individualized hierarchical teaching method for students with different mastery levels of sustainable manufacturing as a part of the teaching method of “interaction between architectural design and elements of sustainable manufacturing”. We will also study the continuing impact of this teaching method on architectural design teaching.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and X.X.; methodology, X.X.; validation, L.L., X.Y. and X.X.; formal analysis, L.L., X.Y. and X.X.; investigation, L.L., X.Y., L.K., J.D. and Q.Z.; resources, L.L. and X.Y.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L., X.Y. and X.X.; writing—review and editing, L.L., X.Y. and X.X.; supervision, L.L., X.Y. and X.X.; funding acquisition, L.L. and X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 14th Five-Year Plan Teaching Reform Project of Common Undergraduate University in Zhejiang Province (Construction of sustainably renewable Diversified Practice Module Teaching System; No. jg20220403).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and reviewers for their kind and valuable suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dincer, I. Renewable Energy and Sustainable Development: A Crucial Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2000, 4, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assembly, U.G. 2005 World Summit Outcome; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-107-01136-6. [Google Scholar]

- Macekura, S.J. Of Limits and Growth: The Rise of Global Sustainable Development in the Twentieth Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-107-07261-9. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Limones, R.; Rey-Perez, J.; Hernandez-Valencia, M.; Roa-Fernandez, J. Student Competitions as a Learning Method with a Sustainable Focus in Higher Education: The University of Seville “Aura Projects” in the “Solar Decathlon 2019”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, A.P.; van Oers, R. Editorial: Bridging Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, L.M. Towards Sustainable Photovoltaics: The Search for New Materials. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 1840–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Feng, K.; Li, X.; Craft, A.B.; Wada, Y.; Burek, P.; Wood, E.F.; Sheffield, J. Solar and Wind Energy Enhances Drought Resilience and Groundwater Sustainability. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, S.P.; Lee, K.; Park, J.; Rieh, S.-Y. A Comparative Study on Sustainability in Architectural Education in Asia—With a Focus on Professional Degree Curricula. Sustainability 2016, 8, 258–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.Y.; Bakış, A.B. Sustainability in Construction Sector. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Implementation of the Outcomes of the United NationsConferences on Human Settlements and on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development and Strengthening of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). In Proceedings of the General Assembly, New York, NY, USA, 21 November 2016.

- Del Mar, C.M.; Alvarez, J.D.; Rodríguez, F.; Berenguel, M. Comfort Control in Buildings. In Advances in Industrial Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 39–78. ISBN 978-1-4471-6346-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert, P.; Castagnino, S.; Rothballer, C.; Renz, A.; Filitz, R. Digital-in-Engineering-and-Construction; Boston Consulting Group BCG: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2020; IEA: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Green Building Council. World GBC Annual Report Annual Report 2020; World Green Building Council: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Drgona, J.; Arroyo, J.; Figueroa, I.C.; Blum, D.; Arendt, K.; Kim, D.; Olle, E.P.; Oravec, J.; Wetter, M.; Vrabie, D.L.; et al. All You Need to Know about Model Predictive Control for Buildings. Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 50, 190–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, W.-M.; Lee, P.K.C.; Lam, K.-H. Building Professionals’ Intention to Use Smart and Sustainable Building Technologies—An Empirical Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, Z.; Draoui, A.; Allard, F. Metamodeling and Multicriteria Analysis for Sustainable and Passive Residential Building Refurbishment: A Case Study of French Housing Stock. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towards the European Higher Education Area. In Proceedings of the Communiqué of the meeting of European Ministers in Charge of Higher Education, Prague, Czech Republic, 19 May 2001.

- Ferrara, M.; Lisciandrello, C.; Messina, A.; Berta, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fabrizio, E. Optimizing the Transition between Design and Operation of ZEBs: Lessons Learnt from the Solar Decathlon China 2018 SCUTxPoliTo Prototype. Energy Build. 2020, 213, 109824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghi, Y.; Ma, Z.; Robinson, D.; Boehme, T. Innovation in Sustainable Solar-Powered Net-Zero Energy Solar Decathlon Houses: A Review and Showcase. Buildings 2021, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomonte, S. State of the Art of Environmental Sustainability in Academic Curricula and Conditions for Registration; Nottingham University: Nottingham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boarin, P.; Martinez-Molina, A.; Juan-Ferruses, I. Understanding Students’ Perception of Sustainability in Architecture Education: A Comparison among Universities in Three Different Continents. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.; Hendel, S.; Stark, M. Solar Decathlon Europe—A Review on the Energy Engineering of Experimental Solar Powered Houses. Energy Build. 2021, 251, 111336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar Decathlon: About Solar Decathlon. Available online: https://www.solardecathlon.gov/about.html (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Rules and Building Code-Solar Decathlon Middle East 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.solardecathlonme.com/imagecatalog/documents/sdme-rules.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Eastment, M.; Hayter, S.; Nahan, R.; Stafford, B.; Warner, C.; Hancock, E.; Howard, R. Solar Decathlon 2002: The Event in Review; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.; Nahan, R.; Warner, C.; Wassmer, M. Solar Decathlon 2005: Event in Review 7–16 October 2005; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, S.V.; Murcutt, G.; Ernst, W.; Mumovic, D.; Pich, F.; Baurier, A.; Baurier, J.; Garcia, P.J.; Wheeler, J.; Dunay, R. Solar Decathlon Europe 2010: Towards Energy Efficient Building. 2011. Available online: https://download.hrz.tu-darmstadt.de/media/FBi5/FGee/SOLAR-DECATHLON-EUROPE-2010.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Sánchez, S.V.; Torre, S.; Kolleeny, J.; Todorovic, M.; Urculo, R.; Pilkington, H.; Twill, J.; Unimas, E.R.; Rollet, P.; Bonnevie, J. Solar Decathlon Europe 2012—Improving Energy Efficient Buildings; Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Salamanca, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, C.; Farrar-Nagy, S.; Wassmer, M.; Stafford, B.; King, R.; Sánchez, S.V.; Rodríguez Ubiñas, E.; Cronemberger, J.; María-Tomé, J.S. The 2009 Department of Energy Solar Decathlon and the 2010 European Solar Decathlon—Expanding the Global Reach of Zero Energy Homes through Collegiate Competitions. In Proceedings of the 34th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7–12 June 2009; pp. 002121–002125. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Limones, R.; Millan-Jimenez, A.; Lopez-Escamilla, A.; Torres-Garcia, M. Health and Habitability in the Solar Decathlon University Competitions: Statistical Quantification and Real Influence on Comfort Conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA EBC || Annex 74 || Competition and Living Lab Platform || IEA EBC || Annex 74. Available online: https://annex74.iea-ebc.org/ (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Hendel, S. The SOLAR DECATHLON Knowledge Platform—Concept and Initial Application 2019. In Proceedings of the ISES EuroSun 2018 Conference–12th International Conference on Solar Energy for Buildings and Industry, Rapperswill, Switzerland, 10–13 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, M. Energy Technology and Lifestyle: A Case Study of the University at Buffalo 2015 Solar Decathlon Home. Renew. Energy 2018, 123, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Limones, R.; Luis Leon-Rodriguez, A.; Lopez-Escamilla, A. Solar Decathlon Latin America and Caribbean: Comfort and the Balance between Passive and Active Design. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemi, P.; Loge, F. Energy Efficiency Measures in Affordable Zero Net Energy Housing: A Case Study of the UC Davis 2015 Solar Decathlon Home. Renew. Energy 2017, 101, 1242–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; de Soto, B.G.; Adey, B.T. Construction Automation: Research Areas, Industry Concerns and Suggestions for Advancement. Autom. Constr. 2018, 94, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevron, M.-P. A Metacognitive Tool: Theoretical and Operational Analysis of Skills Exercised in Structured Concept Maps. Perspect. Sci. 2014, 2, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaal, S. Cognitive and Motivational Effects of Digital Concept Maps in Pre-Service Science Teacher Training. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, L. Effects of Campus Culture on Students’ Critical Thinking. Rev. High. Educ. 2000, 23, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghonim, M.; Eweda, N. Best Practices in Managing, Supervising, and Assessing Architectural Graduation Projects: A Quantitative Study. Front. Archit. Res. 2018, 7, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-1-4129-1606-6. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, S.; Senske, N. Between Design and Digital: Bridging the Gaps in Architectural Education. In Proceedings of the AAE 2016 International Peer-Reviewed Conference, London, UK, 7 April 2016; pp. 192–209. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W. Students’ Evaluations of University Teaching: Dimensionality, Reliability, Validity, Potential Biases and Usefulness. In The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An Evidence-Based Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SET Questions Starting Summer 2020. Available online: https://www.american.edu/provost/oira/set/new_questions.cfm (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Ghonim, M.; Eweda, N. Investigating Elective Courses in Architectural Education. Front. Archit. Res. 2018, 7, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, J.; Tang, R.; Hu, L. A Comprehensive Model of Teaching Digital Design in Architecture That Incorporates Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.E. Situational Analyses: Grounded Theory Mapping After the Postmodern Turn. Symb. Interact. 2003, 26, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-134-80101-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, A.M.; Smith, H.A. Practice Meets Theory in Technological Education: A Case of Authentic Learning in the High School Setting. J. Technol. Educ. 1998, 9, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, F.; Leccese, F.; Salvadori, G.; Spinelli, N.; Moggio, M.; Pedonese, C.; Formicola, L.; Mangiavacchi, E.; Baroni, M.; Vegnuti, S.; et al. Solar Decathlon ME18 Competition as a “Learning by Doing” Experience for Students The Case of the Team HAAB. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, Santa Cruz, Spain, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 1865–1869. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, I.; Gutierrez, A.; Montero, C.; Rodriguez-Ubinas, E.; Matallanas, E.; Castillo-Cagigal, M.; Porteros, M.; Solorzano, J.; Caamano-Martin, E.; Egido, M.A.; et al. Experiences and Methodology in a Multidisciplinary Energy and Architecture Competition: Solar Decathlon Europe 2012. Energy Build. 2014, 83, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R.; Airasian, P.W.; Cruikshank, K.A.; Mayer, R.E.; Pintrich, P.R.; Raths, J.; Wittrock, M.C. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Abridged Editon; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-8013-1903-7. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Wang, X.; Wan, A.; Huang, T.; Hu, L. A Pedagogical Approach to Incorporating the Concept of Sustainability into Design-to-Physical-Construction Teaching in Introductory Architectural Design Courses: A Case Study on a Bamboo Construction Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak, G.K. Disseminating the Use of Sustainable Design Principles Through Architectural Competitions. In 3rd International Sustainable Buildings Symposium (ISBS 2017); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Sev, A. How Can the Construction Industry Contribute to Sustainable Development? A Conceptual Framework. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 17, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mytleanere, K. Toward Sustainable Architecture. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Nykamp, H. A Transition to Green Buildings in Norway. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2017, 24, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Wu, C.; Zheng, J.; Zuo, L. The Research on Sustainable Technology of the Traditional House in the Southern Area of Hubei Province. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2020, 19, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.M. Research in Purpose and Value for the Study of Technology in Secondary Schools: A Theory of Authentic Learning. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2005, 15, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, V.L.; Moore, R.L. Developing Practical Knowledge and Skills of Online Instructional Design Students through Authentic Learning and Real-World Activities. TechTrends 2020, 64, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, P.; Adawi, T.; Gold, J. Linking Teaching and Research in an Undergraduate Course and Exploring Student Learning Experiences. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 42, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Autoethnography as an Authentic Learning Activity in Online Doctoral Education: An Integrated Approach to Authentic Learning. TechTrends 2020, 64, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).