Investigating the Influence of Age-Friendly Community Infrastructure Facilities on the Health of the Elderly in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Variable Selection

2.2.1. Dependent Variables

2.2.2. Independent Variables

2.2.3. Covariates

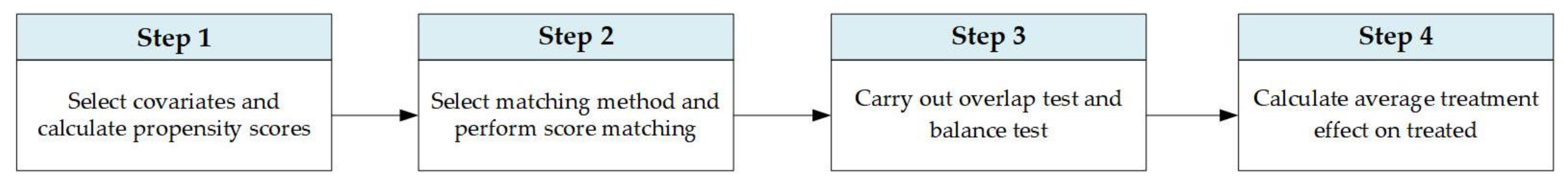

2.3. Research Methodology

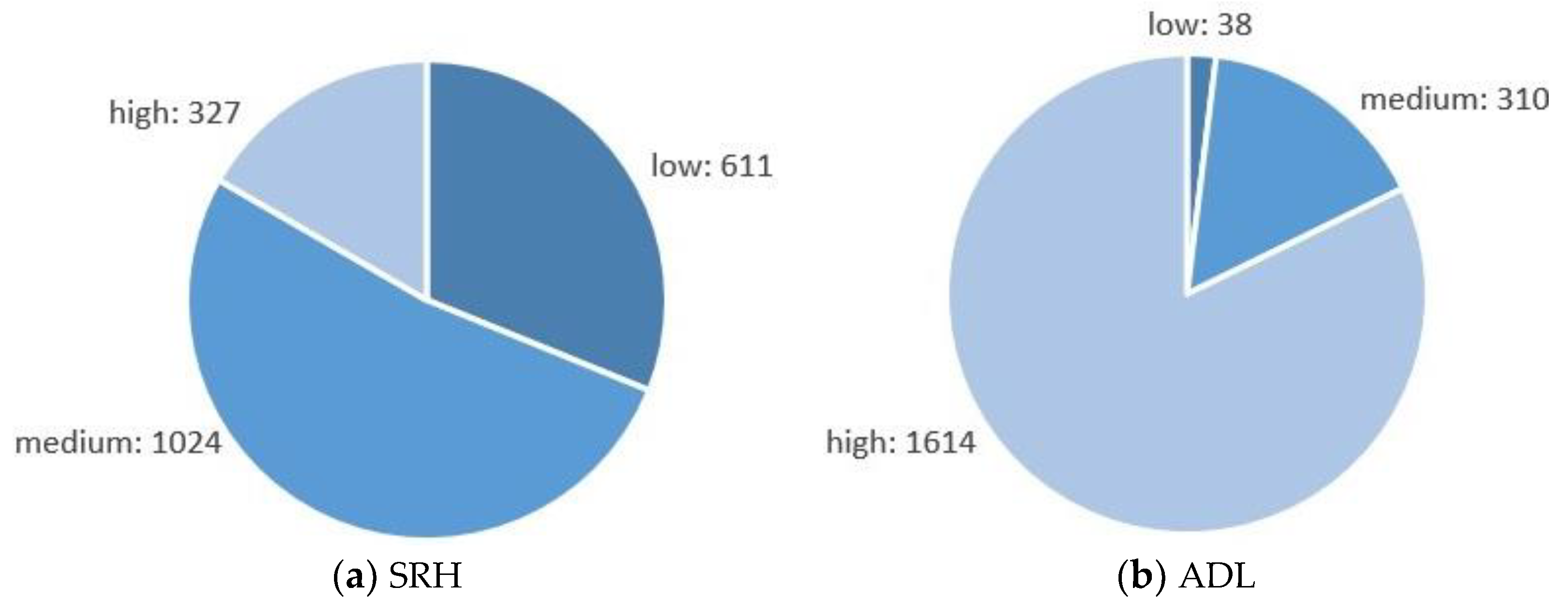

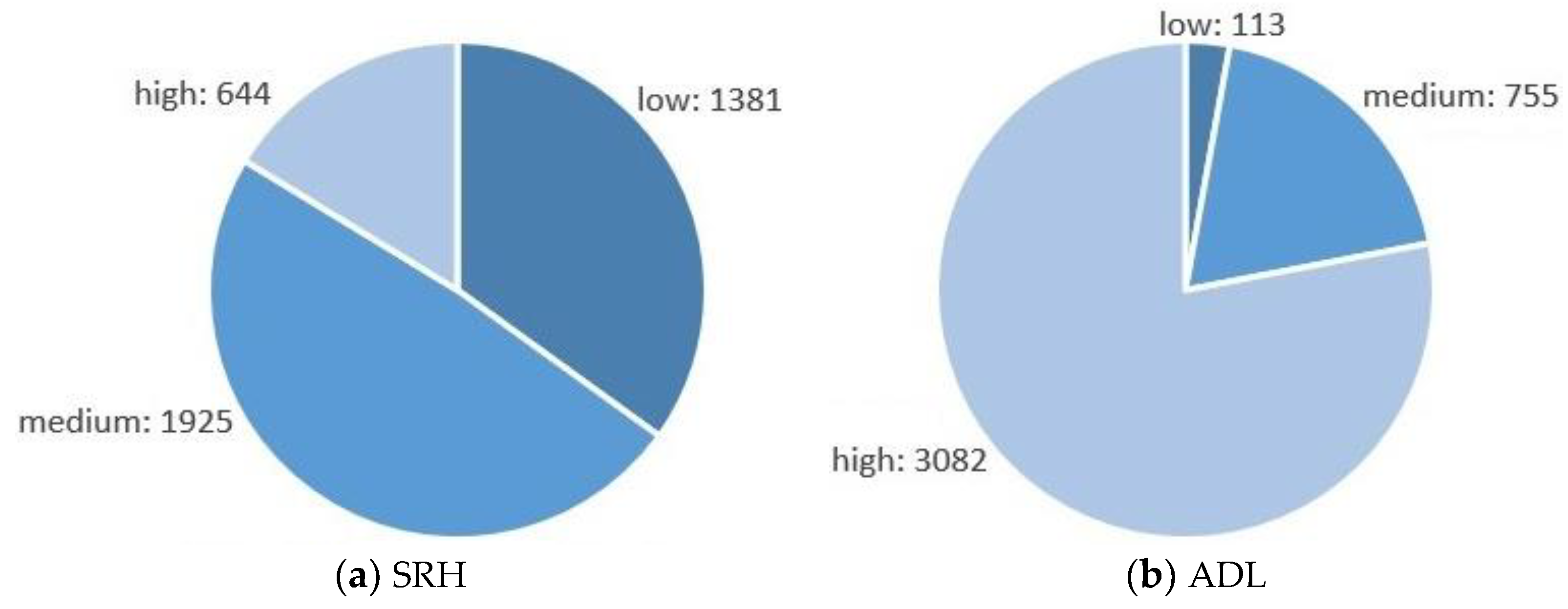

3. Results

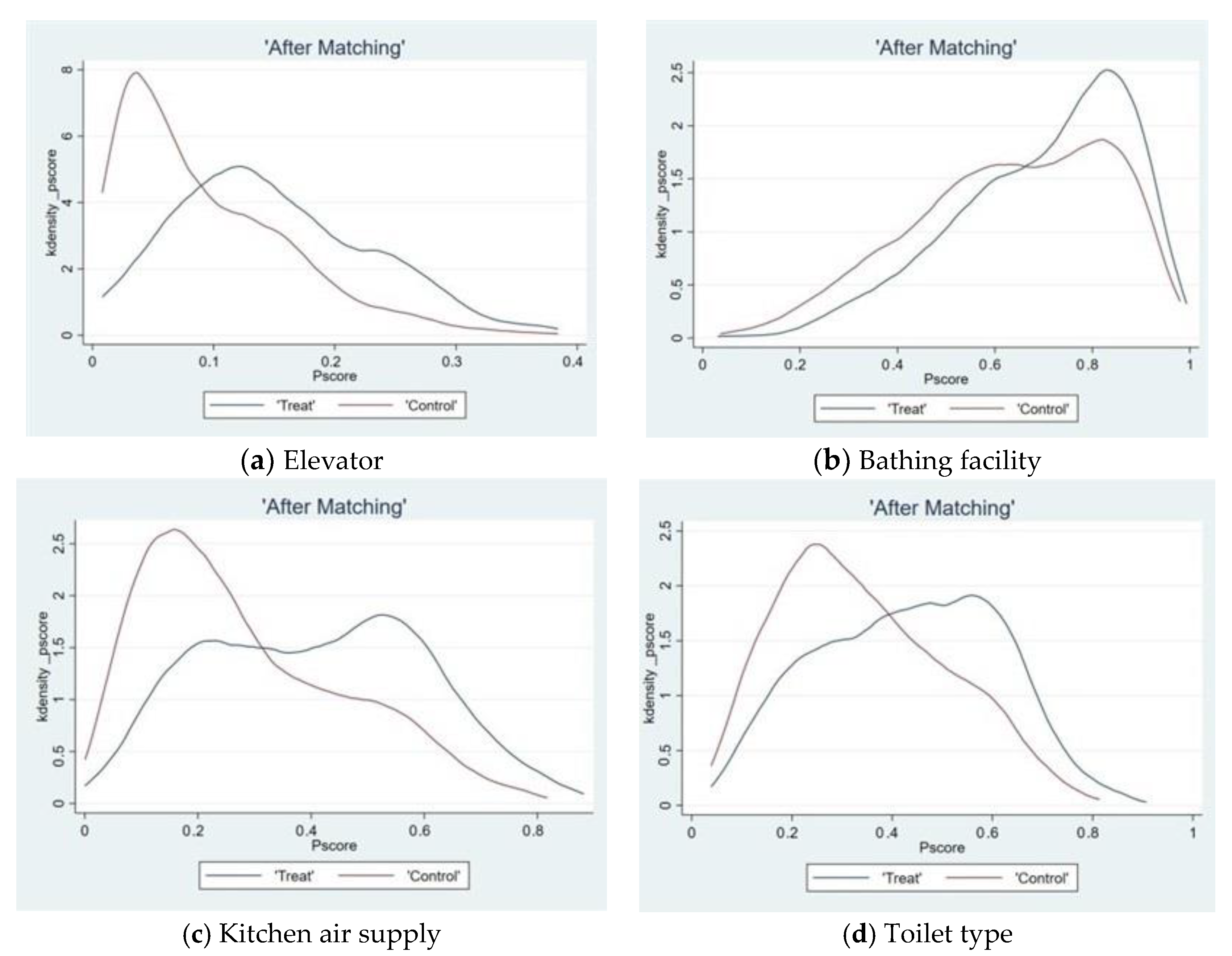

3.1. Overlap Test

3.2. Balance Test

3.3. Average Treatment Effect on Treatment Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, S.; Liu, Y.; Cui, C.; Xia, B. Influence of outdoor living environment on elders’ quality of life in old residential communities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cai, Q.; Li, C.; Wu, X.; Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Wu, Z. A Study in Bedroom Living Environment Preferences of the Urban Elderly in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliner, E.; Riley, M.; Maliene, V. Older people’s preferences for housing and environment characteristics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, R. Safe as houses? Ageing in place and vulnerable older people in the UK. Soc. Policy Admin. 2007, 41, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rao, T. The Effect of the Dwelling Environment on Rural Elderly Cognition: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Shen, S. Adoption of Major Housing Adaptation Policy Innovation for Older Adults by Provincial Governments in China: The Case of Existing Multifamily Dwelling Elevator Retrofit Projects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Lou, V.W.Q.; Lu, N. Does social capital influence preferences for aging in place? Evidence from urban China. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 22, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fänge, A.; Iwarsson, S. Changes in ADL Dependence and aspects of usability following housing adaptation—A longitudinal perspective. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2005, 59, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, S.E.; Jørstad-Stein, E.C.; Hauer, K.; Becker, C. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: The prevention of falls network Europe consensus. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C. Can global cities be ‘age-friendly cities’? Urban development and ageing populations. Cities 2016, 55, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Forsyth, A.; Worthington, S. Built Environment and Self-Rated Health: Comparing Young, Middle-Aged, and Older People in Chengdu, China. HERD: Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2021, 14, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y. City Government’s Adoption of Housing Adaptation Policy Innovation for Older Adults: Evidence From China. J. Gerontol. B 2022, 77, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesaroni, G.; Badaloni, C.; Romano, V.; Donato, E.; Perucci, C.A.; Forastiere, F. Socioeconomic position and health status of people who live near busy roads: The Rome Longitudinal Study (RoLS). Environ. Health 2010, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A.; Timmermans, H. Green spaces in the direct living environment and social contacts of the aging population. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2014, 129, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Nitschke, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shah, P.; Crabb, S.; Hansen, A. Traffic-related air pollution and health co-benefits of alternative transport in Adelaide, South Australia. Environ. Int. 2015, 74, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadda, G.; Cortes, A.; Olivi, A.; Tovar, M. The perception of the values of urban space by senior citizens of Valparaiso. J. Aging Stud. 2010, 24, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collerton, J.; Kingston, A.; Bond, J.; Davies, K.; Eccles, M.P.; Jagger, C.; Kirkwood, T.B.L.; Newton, J.L. The personal and health service impact of falls in 85 year olds: Cross-sectional findings from the Newcastle 85+ cohort study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J. Understanding Aging in Place: Home and community features, perceived age-friendliness of community, and intention toward aging in place. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Zhu, X.; Lane, A.P.; Portegijs, E. Editorial: Healthy aging and the community environment. Front. Public Health. 2021, 9, 737955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N. Designing for social needs to support aging in place within continuing care retirement communities. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2015, 30, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Stafford, M. How do objective and subjective assessments of neighbourhood influence social and physical functioning in older age? Findings from a British survey of ageing. Social Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2533–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbens, R.J.J.; van Assen, M.A.L.M. Associations of Environmental Factors With Quality of Life in Older Adults. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severinsen, C.; Breheny, M.; Stephens, C. Ageing in Unsuitable Places. Housing Stud. 2016, 31, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A.; Molinsky, J.; Kan, H.Y. Improving housing and neighborhoods for the vulnerable: Older people, small households, urban design, and planning. Urban Des. Int. 2019, 24, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsina, L.R.; Willetts, J.L.; Brennan, M.J.; Marucci-Wellman, H.; Lombardi, D.A.; Courtney, T.K.; Verma, S.K. Circumstances of fall-related injuries by age and gender among community-dwelling adults in the United States. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekbrand, H.; Ekman, R.; Thodelius, C.; Moller, M. Fall-related injuries for three ages groups—Analysis of Swedish registry data 1999–2013. J. Saf. Res. 2020, 70, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, C.; Malmqvist, I.; Gromark, S.; Wijk, H. Enablers and Barriers in the Physical Environment of Care for Older People in Ordinary Housing: A Scoping Review. J. Aging Environ. 2020, 34, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, S.; Morgan, P.L.; Schlangen, L.J.M.; Williams, P.; Skene, D.J.; Middleton, B. Blue-enriched lighting for older people living in care homes: Effect on activity, actigraphic sleep, mood and alertness. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Silva, M.; Wolterbeek, H.T.; Almeida, S.M. Elderly exposure to indoor air pollutants. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 85, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, W.J.; Singer, B.C.; Chan, W.R. Association of residential energy efficiency retrofits with indoor environmental quality, comfort, and health: A review of empirical data. Build. Environ. 2020, 180, 107067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loenhout, J.A.F.; le Grand, A.; Duijm, F.; Greven, F.; Vink, N.M.; Hoek, G.; Zuurbier, M. The effect of high indoor temperatures on self-perceived health of elderly persons. Environ. Res. 2016, 146, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, M.; Yu, J.; Chow, H. Impact of indoor facilities management on the quality of life of the elderly in public housing. Facilities 2016, 34, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thordardottir, B.; Fänge, A.M.; Chiatti, C.; Ekstam, L. Participation in Everyday Life Before and After a Housing Adaptation. J. Aging Environ. 2020, 34, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romli, M.H.; Tan, M.P.; Mackenzie, L.; Lovarini, M.; Kamaruzzaman, S.B.; Clemson, L. Factors associated with home hazards: Findings from the Malaysian Elders Longitudinal Research study: Factors associated with home hazards. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, M.Y.; Famakin, I.; Kwok, T. Relationships between indoor facilities management components and elderly people’s quality of life: A study of private domestic buildings. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodabad, S.S.M.; Zareipour, M.; Askarishahi, M.; Beigomi, A. Effect of the Living Environment on falls among the Elderly in Urmia. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, C.A.; Sims-Gould, J.; Winters, M. Safety perceptions of older adults on an urban greenway: Interplay of the social and built environment. Health Place 2021, 70, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylén, M.; Ekström, H.; Haak, M.; Elmståhl, S.; Iwarsson, S. Home and Health in the Third Age—Methodological Background and Descriptive Findings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7060–7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, F.T.; Ariza-Vega, P.; Gardiner, P.A.; Ashe, M.C. Indoor Built Environment and Older Adults’ Activity: A Systematic Review. Can. J. Aging 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. J. Biometrika 1983, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippersiel, P.; Robbins, S.M.; Dixon, P.C. Lower-limb coordination and variability during gait: The effects of age and walking surface. Gait Posture 2021, 85, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, P.; Li, L.; Song, Q.; Sun, W.; Zhang, C.; Fong, D.T.P.; Mao, D. Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation Improves Symptoms Among Older Adults With Knee Osteoarthritis During Stair Ascending: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Bu, J.; Zhang, Q. Do Stairs Inhibit Seniors Who Live on Upper Floors From Going Out? HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2020, 13, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Chen, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chang, C.; Tian, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Ji, Y. The Incidence of Falls and Related Factors among Chinese Elderly Community Residents in Six Provinces. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, P.J.; Golding-Day, M.R. The lived experience of bathing adaptations in the homes of older adults and their carers (BATH-OUT): A qualitative interview study. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 1534–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Mirutse, G.; Guo, L.; Ma, X. Role of socioeconomic status and housing conditions in geriatric depression in rural China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg, L.; Portegijs, E.; Rantanen, T.; Aartolahti, E.; Viljanen, A.; Hirvensalo, M.; Rantakokko, M. Neighborhood Mobility and Unmet Physical Activity Need in Old Age: A 2-Year Follow-Up. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2020, 28, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, H.; Schmidt, S.M.; Iwarsson, S. Home and health among different sub-groups of the ageing population: A comparison of two cohorts living in ordinary housing in Sweden. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, K.; Kurumatani, N.; Hosoi, H. Association between stairs in the home and instrumental activities of daily living among community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Díaz, A.U. Gender, exercise, and health: A life-course cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Diao, Y.; Dong, H. Using a Service Ontology to Understand What Influences Older Adults’ Outdoor Physical Activities in Nanjing. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Assignment |

|---|---|

| Dependent variables: | |

| SRH | Very poor = 1, Poor = 2, Fair = 3, Good = 4, Very good = 5 |

| ADL | No difficulty = 1, Otherwise = 0 |

| Independent variables: | |

| Elevator | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| Bathing facility | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| Kitchen gas supply | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| Toilet type | sitting type = 1, squatting type = 0 |

| Covariates: | |

| Gender | Male = 1, Female = 0 |

| Age | 2018 subtracts the Year of Birth |

| Residential category | Family residence = 1, Otherwise = 0 |

| Education level | From illiterate to doctor degree, assign 0 to 10 |

| Marital status | Married living with spouse = 1, Otherwise = 0 |

| Real sleep time | 0~24 (hour) |

| Exercise score | Yes = 1, No = 0; Added |

| Disease score | Yes = 1, No = 0; Added |

| Chronic disease score | Yes = 1, No = 0; Added |

| Family expenditure | Take its logarithm into the model |

| Family members | Number of family members |

| Variable | The No. 1 Database (1963 Samples) | The No. 2 Database (3950 Samples) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. | |

| Dependent variables: | ||||||||

| SRH | 2.843 | 0.943 | 1 | 5 | 2.801 | 0.965 | 1 | 5 |

| ADL | 10.759 | 2.134 | 0 | 12 | 10.442 | 2.387 | 0 | 12 |

| Independent variables: | ||||||||

| Elevator | 0.090 | 0.287 | 0 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Bathing facility | - | - | - | - | 0.632 | 0.482 | 0 | 1 |

| Kitchen gas supply | - | - | - | - | 0.284 | 0.451 | 0 | 1 |

| Toilet type | - | - | - | - | 0.342 | 0.474 | 0 | 1 |

| Covariates: | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.164 | 0.370 | 0 | 1 | 0.161 | 0.368 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 67.542 | 7.830 | 48 | 98 | 68.018 | 7.386 | 48 | 98 |

| Residential category | 0.990 | 0.100 | 0 | 1 | 0.985 | 0.123 | 0 | 1 |

| Education level | 2.263 | 2.071 | 0 | 8 | 1.891 | 1.945 | 0 | 8 |

| Marital status | 0.733 | 0.442 | 0 | 1 | 0.740 | 0.439 | 0 | 1 |

| Real sleep time | 5.837 | 2.039 | 1 | 15 | 5.880 | 2.130 | 1 | 15 |

| Exercise score | 1.574 | 0.828 | 0 | 3 | 1.524 | 0.862 | 0 | 3 |

| Disease score | 0.176 | 0.459 | 0 | 4 | 0.193 | 0.483 | 0 | 4 |

| Chronic disease score | 0.900 | 1.188 | 0 | 8 | 0.907 | 1.180 | 0 | 11 |

| Family expenditure | 2227 | 2777 | 15 | 80,000 | 1787 | 2248 | 2 | 80,000 |

| Family members | 3.238 | 1.853 | 0 | 15 | 3.019 | 1.786 | 0 | 18 |

| Variable | Matching | Elevator | Bathing Facility | Kitchen Gas Supply | Toilet Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Value | t | D-Value | t | D-Value | t | D-Value | t | ||

| Gender | Unmatched | 0.025 | 0.86 | −0.017 | −1.38 | −0.001 | −0.07 | −0.003 | −0.23 |

| Matched | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.011 | 1.11 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.006 | 0.41 | |

| Age | Unmatched | −1.533 | −2.49 ** | −2.102 | −8.71 *** | −1.256 | −4.83 *** | −0.366 | −1.48 |

| Matched | -0.124 | -0.14 | -0.265 | -1.28 | 0.035 | 0.10 | -0.037 | -0.12 | |

| Residential category | Unmatched | −0.001 | −0.15 | 0.006 | 1.48 | 0.005 | 1.23 | 0.002 | 0.50 |

| Matched | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.002 | 0.64 | 0.001 | 0.20 | −0.001 | −0.28 | |

| Education level | Unmatched | 1.357 | 8.46 *** | 0.934 | 14.96 *** | 1.403 | 21.61 *** | 1.055 | 16.73 *** |

| Matched | −0.006 | −0.02 | 0.064 | 1.11 | 0.003 | 0.03 | −0.018 | −0.22 | |

| Marital status | Unmatched | 0.027 | 0.76 | 0.042 | 2.88 *** | 0.021 | 1.35 | 0.014 | 0.92 |

| Matched | 0.018 | 0.40 | 0.031 | 2.47 | −0.006 | −0.34 | 0.003 | 0.15 | |

| Real sleep time | Unmatched | 0.329 | 2.05 ** | 0.004 | 0.06 | −0.018 | −0.24 | 0.145 | 2.03 ** |

| Matched | 0.051 | 0.27 | 0.031 | 0.53 | 0.006 | 0.07 | 0.029 | 0.38 | |

| Exercise score | Unmatched | −0.073 | −1.11 | 0.117 | 4.12 *** | 0.014 | 0.47 | −0.098 | −3.39 *** |

| Matched | 0.086 | 1.09 | −0.003 | −0.13 | −0.003 | −0.07 | 0.040 | 1.25 | |

| Disease score | Unmatched | −0.045 | −1.24 | −0.099 | −6.25 *** | −0.054 | −3.19 *** | −0.030 | −1.85 * |

| Matched | −0.006 | −0.12 | −0.006 | −0.46 | −0.001 | −0.08 | 0.001 | 0.08 | |

| Chronic disease score | Unmatched | 0.178 | 1.90 * | −0.051 | −1.30 | 0.094 | 2.26** | 0.094 | 2.38 ** |

| Matched | 0.017 | 0.12 | 0.008 | 0.23 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.047 | 1.01 | |

| Family expenditure | Unmatched | 0.650 | 8.65 *** | 0.823 | 25.30 *** | 0.776 | 21.89 *** | 0.672 | 19.75 *** |

| Matched | 0.007 | 0.09 | 0.055 | 2.13 | 0.014 | 0.37 | 0.033 | 0.88 | |

| Family members | Unmatched | 0.142 | 0.97 | 0.715 | 12.36 *** | 0.088 | 1.39 | −0.066 | −1.11 |

| Matched | −0.026 | −0.14 | −0.087 | −1.60 | −0.089 | −1.18 | −0.030 | −0.46 | |

| Variable | Matching Method | Treatment Group | Control Group | ATT | Std. Dev. | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevator | NNM (k = 4) | 3.051 | 2.928 | 0.123 | 0.084 | 1.46 |

| RM (r = 0.2502) | 3.051 | 2.835 | 0.215 | 0.073 | 2.95 *** | |

| KM | 3.051 | 2.911 | 0.140 | 0.076 | 1.85 * | |

| Mean | 3.051 | 2.873 | 0.178 | - | - | |

| Bathing facility | NNM (k = 4) | 2.866 | 2.778 | 0.087 | 0.049 | 1.78 * |

| RM (r = 0.2665) | 2.866 | 2.691 | 0.175 | 0.036 | 4.85 *** | |

| KM | 2.866 | 2.763 | 0.103 | 0.045 | 2.28 ** | |

| Mean | 2.866 | 2.744 | 0.122 | - | - | |

| Kitchen gas supply | NNM (k = 4) | 2.946 | 2.818 | 0.128 | 0.045 | 2.86 *** |

| RM (r = 0.2634) | 2.946 | 2.774 | 0.171 | 0.035 | 4.88 *** | |

| KM | 2.946 | 2.827 | 0.119 | 0.040 | 2.94 *** | |

| Mean | 2.946 | 2.807 | 0.139 | - | - | |

| Toilet type | NNM (k = 4) | 2.924 | 2.780 | 0.144 | 0.042 | 3.43 *** |

| RM (r = 0.2221) | 2.924 | 2.744 | 0.180 | 0.034 | 5.27 *** | |

| KM | 2.924 | 2.758 | 0.166 | 0.038 | 4.31 *** | |

| Mean | 2.924 | 2.761 | 0.163 | - | - |

| Variable | Matching Method | Treatment Group | Control Group | ATT | Std. Dev. | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevator | NNM (k = 4) | 11.339 | 11.048 | 0.291 | 0.150 | 1.94 * |

| RM (r = 0.2502) | 11.339 | 10.753 | 0.586 | 0.126 | 4.65 *** | |

| KM | 11.339 | 11.058 | 0.281 | 0.133 | 2.11 ** | |

| Mean | 11.339 | 10.953 | 0.386 | - | - | |

| Bathing facility | NNM (k = 4) | 10.759 | 10.296 | 0.463 | 0.124 | 3.73 *** |

| RM (r = 0.2665) | 10.759 | 10.115 | 0.644 | 0.091 | 7.04 *** | |

| KM | 10.759 | 10.284 | 0.475 | 0.115 | 4.12 *** | |

| Mean | 10.759 | 10.232 | 0.527 | - | - | |

| Kitchen gas supply | NNM (k = 4) | 10.968 | 10.650 | 0.319 | 0.105 | 3.05 *** |

| RM (r = 0.2634) | 10.968 | 10.452 | 0.517 | 0.082 | 6.27 *** | |

| KM | 10.968 | 10.654 | 0.315 | 0.097 | 3.25 *** | |

| Mean | 10.968 | 10.585 | 0.384 | - | - | |

| Toilet type | NNM (k = 4) | 10.888 | 10.451 | 0.436 | 0.101 | 4.31 *** |

| RM (r = 0.2221) | 10.890 | 10.312 | 0.577 | 0.080 | 7.20 *** | |

| KM | 10.890 | 10.390 | 0.499 | 0.093 | 5.40 *** | |

| Mean | 10.889 | 10.385 | 0.504 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Deng, R.; Shui, Y.; Wang, K.; Hu, Y. Investigating the Influence of Age-Friendly Community Infrastructure Facilities on the Health of the Elderly in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13020341

Chen Q, Zhang Z, Mao Y, Deng R, Shui Y, Wang K, Hu Y. Investigating the Influence of Age-Friendly Community Infrastructure Facilities on the Health of the Elderly in China. Buildings. 2023; 13(2):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13020341

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Qingwen, Zhao Zhang, Yihua Mao, Ruyu Deng, Yueyao Shui, Kai Wang, and Yuchen Hu. 2023. "Investigating the Influence of Age-Friendly Community Infrastructure Facilities on the Health of the Elderly in China" Buildings 13, no. 2: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13020341

APA StyleChen, Q., Zhang, Z., Mao, Y., Deng, R., Shui, Y., Wang, K., & Hu, Y. (2023). Investigating the Influence of Age-Friendly Community Infrastructure Facilities on the Health of the Elderly in China. Buildings, 13(2), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13020341