Abstract

This article explores the persistent issue of assaults on medical staff in China that are unrelated to malpractice, which exacerbate tensions in doctor–patient relationships. These conflicts are primarily fueled by factors such as the disparity between doctors and patients, unequal distribution of medical resources, and inadequacies in the legal protection system. Drawing on Foucault’s micro-power theory, this research proposes a tripartite governance model that includes reconfiguring medical resources through public–private partnerships, implementing proactive legal mechanisms such as hospital-embedded policing systems, and establishing mandatory protocols for treatment explanations to reduce information asymmetry. The article also highlights the importance of medical conflict mediation systems to effectively resolve disputes and ensure satisfaction for all parties involved.

1. Introduction

The deterioration of doctor–patient relationships in China has reached critical levels. According to the White Paper on Chinese Physicians’ Practice Status released by the Chinese Medical Doctor Association in 2018, among 42,838 respondents, only 34% of doctors reported never having personally experienced violent attacks on medical staff, while 66% had encountered doctor–patient conflicts of varying degrees (Chinese Medical Doctor Association 2018). Another study shows that, Chinese medical institutions reported 345 violent incidents between 2000 and 2020, in which 54 involved murdered victims (Zhang et al. 2021). Moreover, in the Work Report of The Supreme People’s Procuratorate, a total of 427 people were prosecuted for crimes involving attacks on or harassment of medical personnel in 2021 (The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China 2022). The frequent occurrence of violent acts against medical staff has garnered significant attention from several sectors. This phenomenon transcends individual disputes, reflecting systemic failures in China’s healthcare architecture. China’s healthcare reforms must address not only institutional organization but also the power asymmetries embedded in clinical encounters (Zhou and Grady 2016). This dual focus is essential for cultivating trust—the cornerstone of therapeutic alliances in medical practice (Hall et al. 2002).

However, existing scholarship predominantly examines doctor–patient tensions through empirical lenses. For instance, some scholars suppose that the tension in doctor–patient interactions arises due to a lack of trust mechanisms, as well as unfamiliarity between doctors and patients (Lv 2024). The issue stems from the intrinsic structure of hospitals as urban medical facilities, which inevitably give rise to impersonal interactions between doctors and patients. As a result, the trust mechanisms now in place have little effectiveness in enhancing these relationships (Li et al. 2019). Some researchers argue that it is important to examine the development of doctor–patient interactions in China from a historical standpoint, focusing on the concept of power (Zhou and Grady 2016). Moreover, research shows the doctor–patient relationship requires balancing clinical expertise and patient accessibility. This requires striking a calibrated equilibrium between temporal constraints of clinical encounters and discursive reciprocity (Yan 2023). While valuable, these approaches neglect the meso-level institutional dynamics—particularly how China’s “three-tier hospital system” structurally allocates both medical resources and epistemic authority. Tertiary hospitals handle 58% of outpatient visits but employ only 22% of doctors (National Health Commission 2022). This concentration of expertise creates Foucaultian “zones of power contestation” where patients’ lay knowledge clashes with biomedical authority (Wu and Yuan 2017).

Foucault’s micro-power theory deconstructs power into a decentralized network that permeates daily interactions, emphasizing its invisible operation through knowledge production and disciplinary mechanisms (Turkel 1990). In the doctor–patient relationship, the doctor’s authority—rooted in institutional recognition of medical knowledge (e.g., professional certification)—creates a power gap. Hospital processes (e.g., waiting rules, treatment protocols) further reinforce this asymmetry through disciplinary mechanisms. This symbiotic relationship between power and knowledge often makes patients dissatisfied due to information blind spots and institutional passivity, which may eventually turn into violent conflicts. This study uses this theory to reveal that the essence of doctor—patient conflicts is not only an individual dispute, but also an external manifestation of the imbalance in the micro-power structure within the medical system, providing a theoretical basis for reconstructing an equal interaction mechanism.

Analyzing from the paradigm of Foucault’s micro-power theory, the doctor–patient relationship within the realm of power relations primarily encompasses two specific dimensions: the inherent authority of doctors derived from their professional medical expertise, and the autonomous cognitive agency and power possessed by patients (Liu and Jia 2017). Consequently, whether harmony and unity can be achieved in the doctor–patient relationship hinges on whether a dynamic equilibrium is attained through the interplay and negotiation of these two dimensions of power. While Foucault’s power–knowledge dyad illuminates status disparities in clinical encounters, its application requires contextualization within China’s unique medico-legal landscape. Moreover, the logical linkages between these aspects must be explained, and management strategies from various viewpoints must be integrated.

2. Uncovering the Truth Behind Malicious Attacks on Doctor

In December 2019, Sun Wenbin admitted his mother to Civil Aviation General Hospital but grew dissatisfied with Dr. Yang Wen’s treatment, harboring resentment and plotting revenge. On December 24, he used a premeditated sharp knife to repeatedly stab Dr. Yang in the emergency room, causing her death. The court ruled that Sun’s actions constituted intentional homicide, noting the crime’s extreme viciousness, cruel methods, severe consequences, and significant social harm. While Sun voluntarily surrendered and confessed post-crime, these factors were deemed insufficient to mitigate punishment due to the offense’s gravity. He was sentenced to the highest penalty under the law in the first-instance judgment, highlighting the judiciary’s strict stance against violent attacks on medical professionals (China Court 2019). Another highly publicized case occurred in 2020; a violent attack on medical staff occurred at Beijing Chaoyang Hospital. Cui, upset that his eye treatment results did not meet his expectations, stormed the outpatient department’s seventh floor with a knife, injuring multiple doctors, nurses, and a bystander. His primary target, Dr. Tao Yong—who had restored some vision to Cui despite his severe complications and had shown concern for Cui’s finances—was brutally chased and slashed from the seventh to sixth floor. Dr. Tao suffered life-threatening injuries, including fractures, nerve and muscle damage, and significant blood loss, leaving him unable to perform surgeries post-recovery. Cui was convicted of intentional homicide and sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve and lifelong deprivation of political rights (The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China 2021).

Doctor–patient conflicts are not just disagreements between the two parties, but rather, they are intricately connected to the underlying social culture and medical system (Lv 2020). To identify the specific causes of malicious attacks on doctors, this study retrieved 131 criminal judgments (2012–2023) by searching keywords such as “killing medical staff,” “assaulting medical staff,” “retaliating against doctors,” and “beating doctors” on China Judgments Online. It should be acknowledged that the above-mentioned data and materials serving as the research foundation are not perfect. Firstly, as it is difficult to obtain data on deviant behavior in China and news reports cannot guarantee complete accuracy, this study can only use violent acts against medical staff constituting crimes as recorded in criminal judgments as research samples, even though this is insufficient to fully reflect the phenomenon of violence against medical personnel. Secondly, the information contained in the collected criminal judgments also has limitations, as not all criminal judgments are publicly disclosed. Therefore, the criminal judgments collected in this study may only reflect a portion of the cases that have occurred. Despite this, these 131 judgments still reveal many commonalities and characteristics of such malicious attack cases.

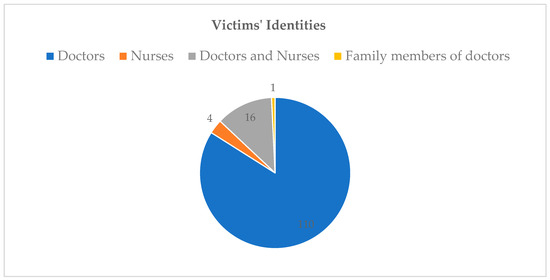

In terms of victims’ identities, the overwhelming majority of victims in violent crimes against medical personnel in China were doctors, rather than nurses (Figure 1). By contrast, numerous studies from outside China have concluded that nurses are the primary victims of most violent attacks on nurses. This cross-cultural difference in victim occupations has been confirmed by other research (Sun et al. 2017), which is one reason why this study focuses on the doctor as its research target.

Figure 1.

Victims’ identity in medical violence crime cases (2012–2023). Source: China Judgments Online.

Based on relevant factors such as the triggering causes of conflicts, criminal motives, and whether criminal tools were prepared, this study classifies these cases into three types: Hatred-based crimes, Reactive Attacks, and Fortuitous Incidents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Specific Types and Relevant Information of 131 Violent Crimes Against Medical Personnel Cases 1.

Hatred-based crimes refer to acts of violently killing or injuring doctors to retaliate against them under the domination of hatred motives, which constitute violations of criminal law. In the sample of this study, there were 43 cases of hatred-based crimes, accounting for 32.8% of all cases. Hatred-based crimes exhibit the following characteristics: (1) The hatred motive is manifested as the perpetrator’s deep resentment toward the victim and the pursuit of the victim’s death. (2) The hatred toward the victim primarily stems from the perpetrator’s dissatisfaction with treatment outcomes. Among the 43 hatred-based crime cases, 31 perpetrators’ hatred originated from dissatisfaction with treatment outcomes, accounting for 72.1% of this crime type (far higher than the proportion in the other two types). (3) The criminal acts in hatred-based crimes are mostly premeditated and cruel. In hatred-based crime cases, 35 perpetrators prepared criminal tools before committing the crime, accounting for 81.4% of this type. Driven by hatred and revenge motives and aided by criminal tools, the means of crime in this category are extremely cruel. (4) Hatred-based crimes result in the most severe outcomes. Among these cases, 22 caused serious injuries or death, exceeding half of the total. Specifically, 14 cases led to victim deaths (32.6% of this type), and 8 caused serious injuries (18.6%). Compared with other types of violent crimes against medical personnel, hatred-based crimes have the gravest consequences.

Reactive attacks refer to criminal acts where perpetrators express their dissatisfaction by committing offenses due to conflicts with medical institutions over issues such as medical services or hospital management. In the research sample, there were 75 cases of reactive attacks, accounting for 57.3% of all cases. Reactive attacks on medical staff exhibit the following characteristics: (1) The primary cause of conflict in reactive attacks is the perpetrator’s dissatisfaction with medical services. A total of 66 cases (88% of this type) involved crimes committed due to dissatisfaction with factors such as the speed of medical service delivery, medical payment procedures, or the attending doctor’s attitude. (2) Reactive attacks are mostly impromptu, with perpetrators generally not preparing beforehand. Only 1 case (1.3%) involved premeditated preparation of criminal tools. (3) The consequences of reactive attacks are less severe compared to hatred-based crimes. None resulted in death or serious injury; 24 cases (32%) caused minor injuries, and 29 cases (38.7%) resulted in slight injuries or less. (4) The study also found a high prevalence of pre-offense alcohol consumption among perpetrators of reactive attacks. In 37 cases (49.3% of this type), the perpetrators were under the influence of alcohol when committing the crimes.

Fortuitous incidents refer to crimes committed solely due to the perpetrator’s own reasons, with the occurrence of the crime being accidental for the victim. In the research sample, fortuitous medical violence incidents were the least common, with only 13 cases, accounting for 9.9% of all cases. Such incidents exhibit the following characteristics: (1) There is no prior interaction or doctor–patient relationship between the perpetrator and the victim before the crime occurs. (2) Perpetrators often commit crimes to vent emotions or pursue a specific goal, neither of which is related to the victim, who is randomly selected. (3) A high proportion of perpetrators in fortuitous incidents consumed alcohol before the crime. In 7 cases (53.8% of this type), the perpetrators were under the influence of alcohol when committing the offenses.

Through a meticulous analysis of these cases, it becomes strikingly evident that in 118 instances, accounting for 90.1% of the total, both hatred-based crimes and reactive attacks were preceded by adverse doctor–patient interactions. Owing to the previously discussed “doctor–patient power gap,” when doctors devise diagnosis and treatment plans, they must consider multifaceted factors such as patients’ medical conditions and physical constitutions. However, when this information is conveyed to patients, the latter usually only comprehend basic aspects like treatment results and expenses. Based on this limited understanding, patients form their own interpretations and expectations, while remaining unable to fathom the intricate underlying reasons and details. This situation exemplifies a significant divergence in how the interacting parties perceive the meaning of the information exchanged. In the face of such interpretive discrepancies, effective communication on an equal footing between doctors and patients proves arduous. Whenever treatment plans or medical procedures deviate from patients’ self-formed understandings and expectations, patients tend to cast doubt on the doctors’ strategies and the effectiveness of the treatment. Should the two parties persistently fail to converge in their comprehension of the information’s significance and value, conflicts will inevitably emerge during their interactions. These conflicts then escalate into negative dynamics, eventually giving rise to animosity or dissatisfaction towards doctors.

Two significant violent attacks against Beijing’s medical personnel stemmed mostly from these communication problems. Though experts said the patient’s condition had improved greatly, the underlying reason for the Chaoyang Hospital event was the patient’s discontent with the mismatch between the treatment outcomes and their expectations. The patient in the Civil Aviation Hospital incident refused to follow the doctor’s treatment plan and lacked appropriate communication throughout the medical process (Peng 2017). Furthermore, the duration of doctor–patient contact correlates negatively with the incidence of disputes (Yan 2023). Research findings reveal that perpetrators of violent acts against medical personnel predominantly have low educational attainments. A staggering 93.3% of them have either received no formal education or only completed basic schooling (Chai and Chen 2024). This objective reality strongly suggests that a lower level of education significantly impedes patients’ ability to understand the information communicated by doctors.

Moreover, the scarcity of sophisticated medical services falls short of meeting people’s expectations for prompt medical care. Fueled by the uneven distribution of medical resources and heavy reliance on the expertise of healthcare professionals, premier hospitals grapple with acute shortages in service provision. Consequently, 64.1% of the factors precipitating criminal acts stem from patients’ discontent with medical services, hospital administration, or the resolution of medical disputes. Among the 8 incidents linked to waiting times, 6 attacks triggered by extended waits took place at tertiary medical facilities. During medical conflicts, patients typically exhibit resistance, driven by information deficits and an ingrained mistrust of expert decisions (The Paper News 2019).

Ultimately, the persistent incidence of assaults on doctors is indicative of deep-seated conflicts within doctor–patient interactions. Patients’ distrust and uncertainty usually result from strong suspicion of doctors’ moral behavior. The contradiction between patients’ expectation of better treatment results and their wish to reduce costs as much as possible tends to foster their distrust. However, without a comprehensive healthcare system that allows people to submit feedback on the quality of medical treatments.

3. China’s Legal Framework: Worsening Doctor–Patient Relations

3.1. Healthcare System Challenges: A Comprehensive Review

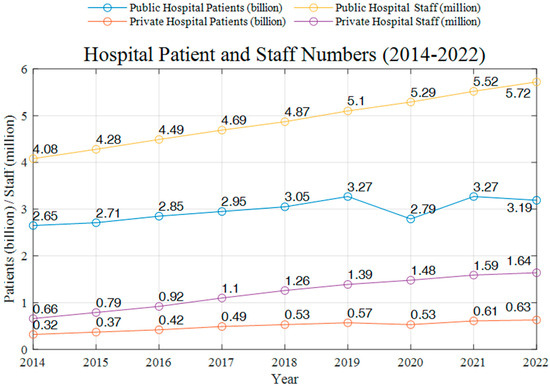

Table 2 reveals structural inequity: in 2022, public hospitals handled 83.5% of patient visits while occupying 64.3% of total institutions, whereas private counterparts (35.7% of institutions) served only 16.5% of patients—a disparity attributable to ’regulated competition’ favoring state actors (Peng 2017). Private hospitals are now undergoing substantial expansion, leading to a notable increase in the number of healthcare professionals and patients in private hospitals. Recent data indicates that the proportion of healthcare professionals and the volume of medical procedures in private hospitals have stabilised at about 15–20% throughout the country. This suggests an equitable allocation of healthcare professionals and treatment sessions throughout the sector. Despite private hospitals’ expansion (15.7% to 16.5% patient share from 2021–2022), their workforce growth stagnated at 22.2% of total medical staff (Table 2, Figure 2), reflecting that ’market entry without market power’ perpetuates dependency on public systems (Hsiao 2014). Despite experiencing growth, their marginalised status within the healthcare system has not improved much. Nevertheless, the long-standing contradictions in medical supply and demand and the healthcare system in China have not fundamentally changed in the post-pandemic era (Frenk 2010).

Table 2.

Comparison table of medical resources between public and private hospitals 1.

Figure 2.

Hospital Patient and Staff Numbers (2014–2022).

The exclusion of private hospitals from China’s healthcare system is seen in two main dimensions. First and foremost, the majority of private hospitals tend to be of modest to medium size. Although laws and financial infusions have provided incentives, their proportion of patient visits throughout the country remains less than 15%. Furthermore, private hospitals have made significant progress in enhancing the quality of their inpatient services by lowering drug and diagnostic costs. However, they do not enjoy the same level of technological advantages in outpatient services as public hospitals. Secondly, in 2022, the percentage of private hospital workers among all medical professionals countrywide was 22.2%, which is 55.6% lower than the proportion in public specialised hospitals. (National Health Commission 2022). Nevertheless, due to limitations imposed by the current healthcare system, the percentage of private hospitals’ market ownership remains undetermined. The existing healthcare system, which revolves around public hospitals, has shown no signs of improvement. Going forward, it is essential to maximize the benefits of private hospitals.

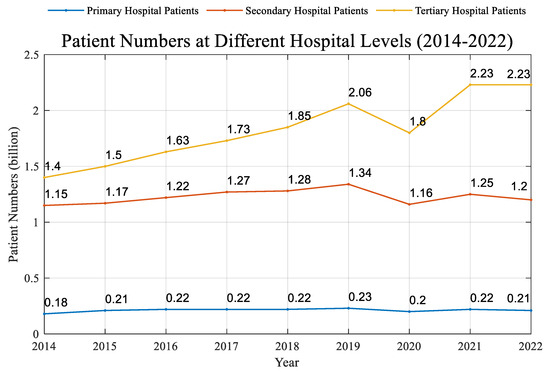

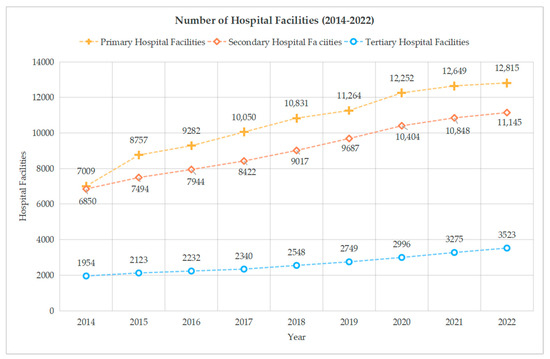

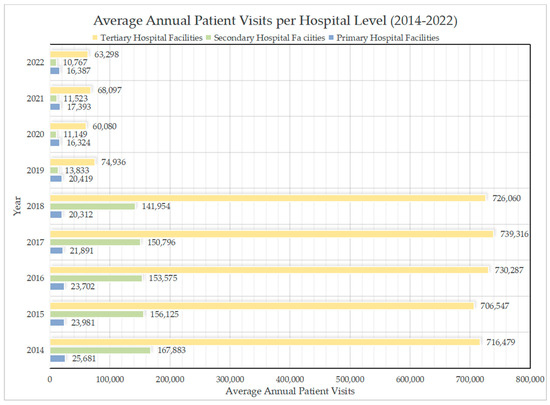

The geographical distribution of medical resources is unequal. The allocation of medical resources is more centralised due to the combined impact of geopolitical and economic centres. The distribution of medical resources is uneven, with a concentration of high-quality resources in big public hospitals. On the other hand, county-level primary hospitals have a very limited supply of medical resources, resulting in a vertical medical system that is characterised by a monocentric structure. This is primarily reflected in the following: (1) Tertiary hospitals’ patient visits are much higher than those at secondary hospitals; they also substantially exceed those at basic hospitals. (2) While their average patient visits are steadily declining, secondary hospitals have a consistent overall basis. This might have resulted in improvements in the quality of their provided medical treatments. (3) The average number of patient visits per hospital has drastically dropped as the number of main hospitals rises, possibly pointing to some underuse of medical resources (Table 3, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Table 3.

Comparison table of medical resources of tertiary hospitals 1.

Figure 3.

PatientNumbers at Different Hospital Levels (2014–2022).

Figure 4.

Number of Hospital Facilities (2014–2022).

Figure 5.

Average Annual Patient Visits per Hospital Level (2014–2022).

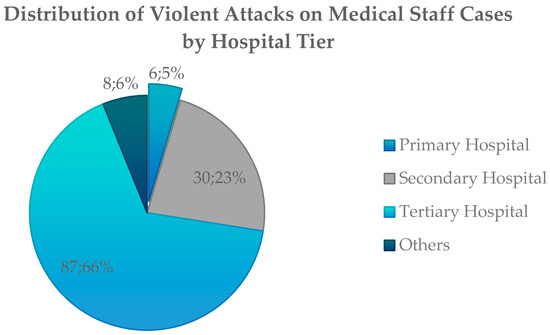

In the 131 cases analyzed in this study, 66% of violent attacks on medical staff occurred in tertiary hospitals—significantly higher than in other hospital tiers (Figure 6). This indicates that violent incidents against medical personnel primarily occur in higher-tier hospitals with advanced medical capabilities. These institutions, equipped with cutting-edge facilities and highly specialized doctors, attract patients from surrounding regions, often resulting in long waiting lines, challenging appointment processes, a high volume of complex cases, intense physician workloads, and elevated patient expectations. Paradoxically, areas with superior medical resource allocation thus experience more frequent violent incidents. Additionally, 23% of cases took place in secondary hospitals, largely due to more severe staffing shortages in some of these facilities, combined with insufficient educational qualifications among staff and less sophisticated medical equipment, which fail to meet patient demands (Chai and Chen 2024).

Figure 6.

Distribution of Violent Attacks on Medical Staff Cases by Hospital Tier.

3.2. Maintaining Order in Healthcare: An Institutional Analysis

The existing healthcare system is defined by a hierarchical arrangement of hospitals and uneven distribution of medical resources across different regions. The prevalence of public hospitals in the market mechanism hinders the promotion of equitable competition in the medical market and the optimization of primary healthcare’s potential functions. Moreover, this results in a decrease in the accessibility of medical services for patients and a discrepancy in the social standing of doctors and patients, hence intensifying tensions in doctor–patient interactions.

China’s substantive law addresses medical violence through Article 290 of the Criminal Law, which criminalizes “disturbances of medical order”. Some academics contend that the criminalization of “medical disturbances” should be attributed to the lack of deterrent effect of criminal punishment (e.g., Xu 2020). This problem is particularly evident due to deficiencies in criminal legislation that lead to incorrect application by the judiciary. Law as a coercive tool may, however, somewhat prevent hostile assaults on medical personnel, but it cannot undo the present lack of patient confidence in doctors. Moreover, one should consider from the standpoint of the present normative systems framework the limits and extent of criminal law, which defines punishments. Nevertheless, while existing legislation provides a legal deterrent against deliberate assaults on doctors through criminal penalties (Article 290, Criminal Law), its efficacy remains partial. It cannot succeed in reinstating people’s confidence in doctors. Presently, Chinese Criminal Law classifies several behaviors associated with “malevolent assaults on doctor”, enabling them to be specifically dealt with under current legal provisions. However, due to unresolved structural deficiencies within the healthcare system, using criminal law as a remedy after the fact to reduce medical violence has practical limits. Hence, it is crucial to construct a governance framework that adheres to the idea of mitigating risks. This framework should include a comprehensive approach to managing medical hazards and conducting rational discussions, with the aim of creating appropriate mechanisms for regulating these risks (Zhang 2016).

The violent attacks on doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic have drawn widespread social concern (People’s Daily 2020). At the national level, China has repeatedly introduced relevant laws and regulations to safeguard the occupational safety of medical personnel. Since 1 June 2020, China’s first foundational and comprehensive health-sector law—Law of the People’s Republic of China on Basic Medical and Health Care and the Promotion of Health—has been formally implemented. Article 33 of this law stipulates that “citizens receiving medical and health services shall comply with diagnostic and treatment protocols and medical service order, and respect medical and health personnel.” Meanwhile, Article 105 states that “disturbing the order of medical institution premises, threatening or endangering the personal safety of medical personnel, or infringing on their human dignity—if constituting a public security violation—shall be subject to public security management penalties in accordance with the law.” On 20 August 2021, the newly adopted Law on Doctors of the People’s Republic of China was officially promulgated. Articles 3 and 49 of the Doctors Law reaffirm the respect and protection of doctors. On 22 September of the same year, eight departments including the National Health Commission and the Ministry of Public Security jointly issued the Guidelines on Promoting Hospital Safety and Order Management. The document mandates that hospitals establish security screening systems and that public security organs station police offices in tertiary hospitals. It also emphasizes multi-channel resolution of medical disputes, requiring different disposal approaches based on dispute nature and severity—for example, hospitals must promptly notify local public security and health authorities of disputes likely to escalate conflicts or even trigger public security or criminal cases.

Meanwhile, provinces across China have successively enacted and adopted regulations and notices governing medical safety and order management. On 5 June 2020, the Beijing Municipal People’s Congress voted to approve the Regulations on Hospital Safety and Order Management in Beijing. The regulations mandate that secondary hospitals in Beijing implement security screening, barring entry to those who refuse; they also include 31 detailed provisions, such as installing one-button alarm systems in key hospital areas. In 2022, the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission issued the Notice on Strengthening Hospital Safety and Order Management in Shanghai, specifying that hospitals must establish security inspection protocols, designate screening zones, and deploy professional security personnel in line with relevant rules. On 11 March 2024, the Gansu Provincial People’s Government approved the Regulations on Hospital Safety and Order Management in Gansu Province, which enumerates seven categories of conduct that disrupt hospital safety, order, and medical procedures. The regulations also clarify that medical staff may take appropriate measures when facing security threats, such as evacuation, self-defense, or temporary suspension of treatment.

The promulgation of these legal documents has yielded measurable positive impacts. Data from the Supreme People’s Procuratorate reveal that prosecutions for crimes against medical staff dropped from 3202 in 2018 to 427 by 2021 (The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China 2022). However, 2022 saw a notable resurgence, with the figure climbing to 467 (The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China 2023).

The inadequate performance of the medical dispute resolution system is an external factor that contributes to occurrences of hostility against medical personnel. Undoubtedly, there are existing difficulties in substantiating the components of medical conflicts, such as a dearth of theoretical evidence. However, this is but one facet of enhancing the legal protections pertaining to medical proceedings. When it comes to the legal regulation of malicious attacks on medical staff, there are many ways in which the strategy of prevention is shown. Nevertheless, this approach of ensuring medical order via precaution fails to overcome the shortcomings of its delayed warning effectiveness. More precisely, the authorities were unable to promptly respond when the malicious assaults targeted medical professionals. Although the doctors were chased for a long time by the offenders, no one intervened to stop them, resulting in the inability to quickly prevent the harmful repercussions. The Chinese court, which focuses on settling disputes and pursuing justice as a core objective, does not adequately take into account risk considerations at the societal level (Wu 2015).

3.3. Enhancing Healthcare System Efficacy: A Detailed Review

Current dispute resolution systems often overlook the vulnerable position of doctors in medical conflicts. These systems tend to prioritize preserving stability over ensuring that rights and obligations are equitably distributed among all parties involved.

3.3.1. Doctors in a Vulnerable Position

The doctors’ mission to preserve lives and assist the wounded, in conjunction with their expertise, establishes a hierarchical distinction between them and their patients. Nevertheless, the medical setting and institutional structures expose clinicians to a precarious position in the face of medical conflicts. The intermingling of institutional identities exacerbates the medical side’s disadvantage in settling medical conflicts. Outside of the medical area, the hospital’s identity is a combination of professionalism and public responsibility. In settling medical disputes, the hospital generally opts for an extrajudicial private settlement approach, which gives patients a significant role in the decision-making process. However, this standard approach is often criticized for lacking controllability (Zhao 2011).

The underlying reason for this extrajudicial private settlement paradigm may be attributed to the interconnected nature of professionalism and public obligation within hospitals. The professionalism of hospitals mitigates the possible negative social repercussions and resource drain caused by turning to legal action, which may damage competitiveness due to long legal proceedings.

Hospitals, functioning as legal entities, provide expert medical services, and their functioning relies on maintaining a positive social standing. Hospitals’ dependence on reputation hinders their ability to address medical disputes via legal channels due to a lack of practical circumstances. Hospitals are placed at a disadvantage in settling doctor–patient conflicts due to the overwhelming focus on social reputation. In addition, hospitals are presently managed by public institutions, and their managers also have official positions. Within a pressure-driven system, individuals instinctively abide by the concepts of “maintaining stability” and “quick resolution” while addressing disagreements. Hospitals take a non-judgmental and de-rationalized posture in medical disagreements due to factors like “stability”, “speed”, and “reputation” (Legal Daily 2024; People’s Daily 2024).

3.3.2. Misjudgments in Medical Dispute Resolution

The process of transferring medical risks results in mistakes when establishing liability in medical disputes. In China, the dispute resolution process has a tendency toward bias, prioritizing the smooth settlement of disputes above the correctness of judgments about medical behavior.

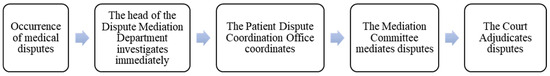

Initially, the first step in settling medical issues in China entails addressing them internally within institutions. When internal settlement of a conflict is not possible, it is escalated to a medical dispute mediation committee for resolution (Figure 7). Because the leader of a hospital has overlapping responsibilities within the system, doctors are often presumed to be at fault when it comes to settling medical disputes. This perception hinders the effectiveness of the first dispute resolution processes. While the Regulations on the Prevention and Handling of Medical Disputes outline procedures for resolving medical disputes—including mediation, arbitration, and litigation—these processes often face issues of lengthy processing cycles and high costs in practice. Consequently, many doctors opt to suffer in silence or resolve disputes privately when confronting conflicts, which further exacerbates their psychological stress and job burnout to some degree. Additionally, when addressing medical disputes, some local governments and hospitals often prioritize mediation and compromise to maintain social stability, overlooking the protection of medical staff’s legal rights and placing them in a disadvantaged position during dispute resolution. Research has shown that under strict healthcare regulations, hospitals or administrative bodies often adopt a “conflict-avoidance” approach to minimize dispute frequency (Li and Wang 2023). In some hospitals, medical staff even receive “grievance awards” as a form of appeasement after experiencing violent attacks. Such practices not only fail to effectively resolve the underlying issues but may also deepen their sense of injustice and dissatisfaction (CQN 2019; DXRC 2024).

Figure 7.

Medical Dispute Resolution Process.

This phenomenon is also present in medical litigation. When courts adjudicate medical disputes, they frequently impose duty on flawless institutions to provide compensation, reflecting a blatant unfairness. This is performed in accordance with the idea of safeguarding the weaker side.

3.3.3. Medical Insurance System Undermines Trust

The medical insurance system’s structural flaws—including resource maldistribution and perverse incentives—erode trust between doctors and patients. Limited medical insurance reimbursements and chaotic government control force doctors to use an over-treating minor illness approach to minimize any medical hazards. Particularly, the government’s inadequate healthcare funding has led to excessive commercialization. At the same time, the existing regulatory systems for the pharmaceutical business are flawed, resulting in a substantial cost burden on patients. In this context, doctors in this situation depend on “pharmacy-driven revenue” to obtain appropriate payment, resulting in the over commercialization of medical items (Chen et al. 2013).

Since the reform and opening-up, China’s medical insurance system has developed from pilot projects to national coverage. However, due to the large population and fiscal constraints, the current medical insurance in China features extremely limited reimbursement amounts. In addition, the interconnection between the three primary components of public health maintenance—namely, healthcare, health insurance, and medicines—has not been effectively established. Hospitals continue to depend on pharmaceutical sales as a source of income, and consumers have not yet fully experienced the socioeconomic advantages that health insurance should provide.

To address urban–rural disparities in medical insurance, the Chinese government has launched reforms to unify urban–rural resident medical insurance. However, these efforts have not narrowed gaps in premium structures, contribution thresholds, medical benefits, and other areas between urban employee medical insurance and urban–rural resident medical insurance—particularly for the latter. Data from the 2021 National Medical Security Development Statistical Bulletin by China’s National Healthcare Security Administration show the urban employee medical insurance fund covered 84.4% of inpatient costs within policy limits. Reimbursement rates for tertiary, secondary, and primary/hospital-level facilities were 83.4%, 86.9%, and 87.9%, respectively. In contrast, urban–rural resident medical insurance covered 69.3% of inpatient costs overall, with rates of 64.9%, 72.6%, and 77.4% for the same facility tiers—all significantly lower than employee insurance (National Healthcare Security Administration 2021).

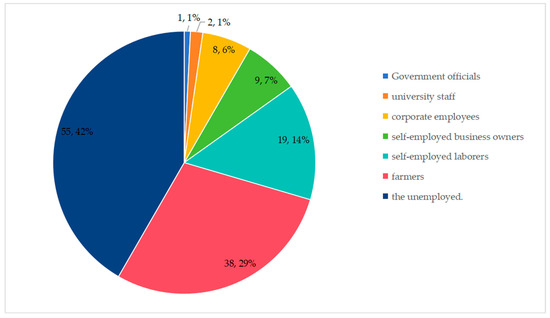

Compared to urban employees, lower reimbursement rates impose a heavier financial burden on low-income groups like farmers and the unemployed enrolled in urban–rural plans, increasing their likelihood of adversarial doctor–patient interactions. This correlation is validated by occupational analysis in this study: among 186 perpetrators in 131 cases, 132 had recorded occupations. Of these, 92% were farmers, migrant workers, or unemployed—demographics systematically disadvantaged within the medical insurance framework (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Occupational Profiles of Perpetrators in Violent Attacks Against Medical Staff.. In China, occupations eligible to enroll in urban employee medical insurance (with higher medical expense reimbursement rates) include government officials, university staff and corporate employees; while self-employed business owners, self-employed laborers, farmers, and the unemployed can only participate in urban–rural resident medical insurance.

To sum up, patients now seek both “low-cost” expenses and “high-quality” treatments as a result of declining diagnostic and treatment capacity of main healthcare facilities combined with waste of medical resources. This conflicts with the doctors at higher-level hospitals working too much. Doctors struggle to provide higher-level individualized medical services even as they provide consistent medical treatment. Furthermore aggravating these conflicts in an informationally unequal environment is the absence of scientific management in the insurance system, which results in misalignment and misinterpretation between doctors and patients.

4. Legal Approaches to Managing Malicious Attacks on Doctors

Bridging the power gap between doctors and patients requires building a positive interactive relationship. However, this gap is exacerbated by uneven distribution of medical resources and the medical insurance system on one hand, while the unilateral role of legislation has also proven limited on the other. Doctor–patient relationships are surrounded by tiny, everyday physical mechanisms and all those systems of micro-power (Foucault 1977). Therefore, “the focus must be on the specific material relations of power, of how it is exercised, concretely and in detail.” (Foucault 1980). Tackling harmful assaults on doctors is a methodical endeavor that necessitates the equitable use of medical resources to enhance the healthcare system’s framework. This approach prioritizes the avoidance of risks as a fundamental tenet of governance and the implementation of standardized protocols in medical practice.

4.1. Transforming the Structure of the Healthcare System

Between 2014 and 2022, the proportion of tertiary hospitals fluctuated between 11.2% and 12.8%, while their average outpatient visits accounted for 68.6–81.7% (Table 2). This “inverted pyramid” structure has resulted in prolonged waiting times for patients and a critical mismatch between their expectations and the healthcare system’s service capacity. Structurally, 66% of violent attacks against medical staff occurred in tertiary hospitals (Figure 6), exemplifying an outbreak of contradictions triggered by the overconcentration of premium medical resources. Therefore, it is imperative to advance structural reforms within the healthcare system.

Promoting structural reforms in medical resource allocation allows for policy and financial support to primary care facilities and private medical institutions. This support enhances the quality of service and facilitates better communication between doctors and patients. Furthermore, it is essential to enhance the provision of traditional Chinese medicine services at the local level in order to effectively address the medical requirements of the community (Yu and Liu 2020).

Implementing a dual system gives equal importance to both public and private hospitals. This approach boosts the standing of private hospitals. It also reduces the profit-driven approach of medicine-funding medical services. Countries such as the UK and Canada have discovered an alternative approach that lies between government involvement and market competitiveness. Universal public healthcare systems can lead to lower quality and efficiency in medical services, while commercialized medical models tend to drive up healthcare costs. Therefore, it is worth considering the third path explored by countries like the United Kingdom and Canada, which balances state intervention and market competition. They expand private practices outside the universal system. This approach explores compatibility between healthcare systems and market dynamics. The goal is to resolve the contradictions between inefficiency and cost.

The ongoing reform of the system entails the delicate task of reconciling the competing demands of various social groups, while simultaneously guaranteeing equitable protection of everyone’s rights and efficient allocation of medical resources (Liu et al. 2015). Furthermore, a progressive vertical healthcare system structure should be formed. A scientific vertical system should include both “positive progression relationships” and “reverse guidance effects”. The “positive progression relationship” suggests that the distribution of patient visits among primary, secondary, and tertiary hospitals should form an ascending pyramid. Initial patient consultations should predominantly occur at primary hospitals, which function primarily as “service hospitals”. The “reverse guidance effect” refers to the use of research capabilities and geographical advantages by tertiary hospitals to provide expert assistance to lower-level institutions.

Last but not least, implementing institutional changes is essential to ensure the fair allocation of medical resources. When it comes to maintaining a fair relationship between doctors and patients, it is of utmost importance to rethink the existing evaluation system for hospitals. Specifically, the performance assessment system for hospital executives should be updated and replaced. When it comes to trust mechanisms between doctors and patients, it is crucial to uphold the notion of equity in medical practices and provide equitable treatment across patients. Moreover, it is essential to adhere to the idea of consistency in medical services, along with stringent control of medical equipment and the enhancement of the health insurance system, in order to effectively address the problem of over-treatment in a methodical manner. Going forward, addressing medical insurance reimbursement disparities is crucial. This institutional inequity has resulted in 92% of perpetrators being from low-income groups (Figure 8). It is recommended to gradually increase the reimbursement ratio for urban and rural residents’ medical insurance to alleviate doctor–patient tensions at their economic core.

4.2. Upholding Medical Order with the Precautionary Principle

With the rise of a risk society, precaution against uncertain risks has become a legal responsibility essential to establishing medical order. In the legal construction of medical order, it is crucial to focus on precaution as the primary method, especially in light of the inherent deficiencies within China’s transforming healthcare system.

First, the implementation of hospital police authority introduces an official level of coercive power to uphold medical order, serving as a deterrent against assaults on medical personnel prior to and during incidents. This necessity is underscored by cases like the 2020 Beijing Chaoyang Hospital attack, where the perpetrator chased a doctor from the 7th to 6th floor with a knife without intervention, exposing critical flaws in hospital security screening and emergency response systems. Public security agencies used to just provide security, but now they also keep an eye on things inside hospitals. This is because hospital security needs and other societal factors are always changing (Li and Wang 2023). The establishment of police authority aims to preserve social order and combat unlawful behaviors, differentiating between investigatory power (which reconstructs past crimes to balance punishment and human rights) and administrative power (which targets ongoing or imminent illegal acts). Malicious attacks on doctors, like the Chaoyang Hospital incident, exemplify improper interferences with medical order that necessitate a tiered warning system: such systems clarify public security agencies’ roles in promptly halting disturbances, contrasting with the failed passive security measures that allowed the attack to escalate unimpeded. The administrative power, focused on public security management, must now proactively address unfolding threats rather than relying on reactive measures.

Second, the features of malicious medical assault cases. These events are characterized by possible public nature, biased interests, and substantive law level severity. In criminal law, the “Criminal Law Amendment (IX)” legally criminalizes medical disruptions without changing the behavior patterns. It is therefore essential to improve the application criteria for pertinent charges, thereby ensuring a fair criminal law assessment of intentional medical assault instances. For instance, the application criterion of Article 290, Section 1 of the “Criminal Law”, which calls for “medical activities to be hampered” and “causing severe losses” for a conviction of disrupting public order, could be decreased. Based on the “precautionary principle”, the threshold for this crime should be reduced to the single criterion of “hindering medical activities”. This also echoes the provision in Article 60 of the Law on Doctors of the People’s Republic of China, which prohibits “obstructing doctors from lawfully practicing their profession, interfering with their normal work and life, or infringing upon their personal dignity and safety through insults, slander, threats, assaults, or other means.” Additionally, for non-large-scale malicious medical assault cases, Article 293 of the “Criminal Law” on creating disturbances should be applied. Furthermore, patients involved in specific illegal activities should face appropriate charges. If a patient extorts property or commits fraud with improper motives, they should be charged with property crimes. Similarly, if a patient obstructs police officers from performing their duties, they should be charged with obstruction of public service crimes.

Third, leverage the prosecutorial authorities’ role in managing cases of malicious attacks on medical staff. Due to the specialized nature of medical disputes and the hospitals’ bias towards maintaining their “reputation”, there is a tendency towards “decriminalization” in handling crimes involving medical issues. This practice can diminish the offender’s subjective awareness of norms to some extent. Such tendencies towards a “keep the peace” approach must be addressed within the legal procedures. As a legal supervisory body, the prosecutorial authorities have the legitimacy to correct the actions based on their authority. In criminal proceedings, the prosecutorial authorities should promptly issue prosecutorial recommendations and uphold the authority of the law.

4.3. Promoting Standardization in Medical Practice

Enforcing doctors’ commitment to provide explanations as a legal requirement helps proactively avoid problems, while implementing a medical dispute mediation framework can effectively resolve disputes if they arise.

First, it is essential to clarify doctors’ obligation to explain significant medical matters during the course of their medical practice. The dominant relationship between doctors and patients is fundamentally due to the disparity in medical knowledge between the parties, a gap that is starkly reflected in data: 80.2% of violent incidents stem from dissatisfaction with treatment outcomes or medical services (Table 1), compounded by the fact that perpetrators of medical violence often have low educational attainment (Chai and Chen 2024). It is critical to establish a preventive regulatory framework to curb arbitrary practices. This regulation should require that doctors are obligated to provide a comprehensive explanation of significant matters pertaining to patient welfare during medical operations. If doctors do not meet this commitment, there should be appropriate legal consequences. Simultaneously, control of overactive medical practices—more especially, definition of the extent of overtreatment and improvement of compensation policies—is needed. Using other companies might also assist in resolving issues without clear answers (Dong et al. 2025).

Furthermore, enhancing the third-party medical dispute settlement method. The rise in doctor–patient disagreements may be attributed mostly to the inadequacy of the routes for resolving these issues. Conventional approaches to settling medical conflicts include medical litigation and administrative mediation. Given their involuntary character, absence of specialization, and intricacy, these procedures are unable to truly fulfill patients’ need for equitable and fast settlement of disputes. In addition, due to the institutional status of public hospitals as state-sanctioned entities under China’s Civil Code (Article 54), doctors are legally designated as agents of biomedical authority in medical disputes. These resolution models pushed by the government are unable to achieve true support among patients. Consequently, patients may only deviate from official resolution channels and violate the established medical order in order to obtain compensation. By tackling the problems at their origin, this institutional approach to mediation might help lower the possibility of medical conflicts (Wang et al. 2020).

5. Conclusions

The doctor–patient relationship is a legal and equal partnership between persons that is based on trust and protected by the medical system. The doctors’ possession of specialized expertise results in an inherent disparity in their social standing compared to patients. This research integrates the analysis of factors including victims, perpetrators, crime causes, and crime locations in 131 criminal verdicts with medical data, revealing that the unequal distribution of medical resources and legal flaws have jointly exacerbated tensions and fueled conflicts.

This article seeks to provide policy solutions for addressing the inequitable allocation of medical resources across various levels and areas. The objective is to alleviate the treatment burdens faced by doctors and enhance communication and service quality between doctors and patients. Moreover, the article proposes implementing the concept of risk prevention by giving hospital police the authority to rapidly mediate disagreements and authorizing prosecutors to handle cases of unfair punishment. In addition, the article supports the implementation of legislative requirements that oblige doctors to provide explanations for important medical issues, and for hospitals to assume the responsibility of proving their practices during legal disputes in order to govern hospital practices. Finally, it implements a varied dispute resolution procedure, using mediation to settle issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S.; Data curation, R.G.; Writing—original draft, W.S. and R.G.; Writing—review & editing, W.S., R.G. and H.W.; Visualization, H.W.; Supervision, W.S.; Project administration, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to all the cases and data mentioned in our paper are derived from government reports or public media coverage. According to Article 2 of China’s Regulations on the Review of Scientific and Technological Ethics (《科技伦理审查办法》) and Article 3 of the Regulations on the Ethical Review of Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans (《涉及人的生命科学和医学研究伦理审查办法》), the research in this paper also falls outside the scope of review.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chai, Songyang, and Guochen Chen. 2024. Identification of Key Populations, Time and Space, And High-Risk Factors for Violent Medical Injuries. Health Law 32: 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Aixue, Yushan Ji, and Nanfu He. 2013. Reform of the healthcare system should prevent over-marketisation. Economic Review Journal 8: 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Court. 2019. China Court Civil Aviation General Hospital Injury Incident: Female Doctor Died Due to Injury. December 25. Available online: https://www.chinacourt.org/article/detail/2019/12/id/4743442.shtml (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- China Quality News. 2019. Violent Attacks on Medical Staff by Patients Cannot be Limited to “Grievance Awards”. February 25. Available online: https://www.cqn.com.cn/ms/content/2019-02/25/content_6805795.htm (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Chinese Medical Doctor Association. 2018. White Paper on Chinese Physicians’ Practice Status (2017). Available online: https://www.cmda.net/u/cms/www/201807/06181247ffex.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- DingXiangRenCai. 2024. Hospital Policy: Unjustified Complaints Won’t Lead to Penalties—Instead, “Comfort Payments” and “Grievance Awards” Offered! September 9. Available online: https://www.jobmd.cn/article/qtyzzx/10008043.htm (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Dong, Chonghao, Maorui Yang, Hanqing Zhao, Gordon G. Liu, and Yujie Cui. 2025. An Analysis of the Standard and Responsibility of Excessive Medical Tort. Nursing and Rehabilitation 4: 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0394499420. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. Edited by Colin Gordon. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0394739540. [Google Scholar]

- Frenk, Julio. 2010. The Global Health System: Strengthening National Health Systems as the Next Step for Global Progress. PLoS Medicine 7: e1000089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Mark A., Elizabeth Dugan, Beiyao Zheng, and Aneil K. Mishra. 2002. Trust in Physicians and Medical Institutions: What Is It, Can It Be Measured, and Does It Matter? Milbank Quarterly 79: 613–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, William C. 2014. Correcting past health policy mistakes. Daedalus 143: 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legal Daily. 2024. Rapid Response to Demands: Contributing to “Ensuring Access to Good Medical Care”. March 28. Available online: http://www.legaldaily.com.cn/commentary/content/2024-03/28/content_8978650.html (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Li, Chang, and Jianxin Wang. 2023. The Role reconfiguration of Public Security Organs Participating in the Maintenance of Hospital Public Security Order. Journal of Hubei University of Police 6: 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Zhaoxu, Jin Zhang, Liyan Zhu, Hongyan Yin, Guodong Liu, Chongyan Ji, Xianhong Huang, Lei Han, and Jinfeng Yu. 2019. Time Attribute of China’s Doctor-Patient Conflict and Social Governance Strategies. Chinese Hospital Management 39: 65–67. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Time+Attribute+of+China%27s+Doctor-patient+Conflict+and+Social+Governance+Strategies&btnG= (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Liu, Junxiang, Yonghui Ma, and Jingzi Xu. 2015. An Evaluation on Equity in Current Primary Healthcare Reform in China. Asian Bioethics Review 7: 277–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Pengfei, and Zhonghai Jia. 2017. Examining Chinese Doctor-Patient Conflicts through the Lens of Foucault’s Micro-power theory. The Northern Forum 1: 131–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Xiankang. 2024. Fostering Trust through Emotional Communication: An Emotional-Sociological Approach to Rebuild Doctor-Patient Trust. Nankai Journal (Philosophy and Social Science Edition) 1: 1–10. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%E2%80%9C%E7%BC%98%E6%83%85%E7%BB%93%E4%BF%A1%E2%80%9D%3A+%E9%87%8D%E5%BB%BA%E5%8C%BB%E6%82%A3%E4%BF%A1%E4%BB%BB%E7%9A%84%E6%83%85%E6%84%9F%E7%A4%BE%E4%BC%9A%E5%AD%A6%E8%B7%AF%E5%BE%84&btnG= (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Lv, Xiaokang. 2020. From Doctor-Patient Relationship Governance to Doctor-Patient Community Construction: A Coordinated Approach to Rebuilding Doctor-Patient Trust. Journal of Nanjing Normal University (Social Science Edition) 4: 84–93. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%E4%BB%8E%E5%85%B3%E7%B3%BB%E6%B2%BB%E7%90%86%E5%88%B0%E5%85%B1%E5%90%8C%E4%BD%93%E5%BB%BA%E8%AE%BE%3A%E9%87%8D%E5%BB%BA%E5%8C%BB%E6%82%A3%E4%BF%A1%E4%BB%BB%E7%9A%84%E5%8D%8F%E5%90%8C%E8%B7%AF%E5%BE%84 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- National Healthcare Security Administration. 2021. National Medical Security Development Statistical Bulletin; June 8. Available online: https://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2022/6/8/art_7_8276.html?eqid=d4fa78af0003179d000000036433b153 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- National Health Commission. 2022. China Health Statistical Yearbook; Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Press.

- Paper News. 2019. Breaking: Details Emerge on Fatal Stabbing of Doctor at Beijing Civil Aviation General Hospital; State Rolls out Legislation to Combat Medical Disturbances. December 29, Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_5376817 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Peng, Jie. 2017. Knowledge Disparity and Structural Distrust: The Generative Logic of Patient Resistance in Medical Disputes. Academic Research 2: 66–71. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%E7%9F%A5%E8%AF%86%E4%B8%8D%E5%AF%B9%E7%AD%89%E4%B8%8E%E7%BB%93%E6%9E%84%E6%80%A7%E4%B8%8D%E4%BF%A1%E4%BB%BB%3A%E5%8C%BB%E7%96%97%E7%BA%A0%E7%BA%B7%E4%B8%AD%E6%82%A3%E8%80%85%E6%8A%97%E4%BA%89%E7%9A%84%E7%94%9F%E6%88%90%E9%80%BB%E8%BE%91&btnG= (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- People’s Daily. 2020. Ministry of Justice: Crack Down on Violent Attacks against Medical Staff and other Illegal Acts with Severity, Rigor, and Speed. February 24. Available online: https://www.peopleapp.com/column/30036897904-500001949556 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- People’s Daily. 2024. Speed is the Most Basic Requirement for Responding to Patients’ Demands. March 28. Available online: http://health.people.cn/n1/2024/0328/c14739-40205258.html (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Sun, Peihang, Xue Zhang, Yihua Sun, Hongkun Ma, Mingli Jiao, Kai Xing, Zheng Kang, Ning Ning, Yapeng Fu, Qunhong Wu, and et al. 2017. Workplace Violence against Health Care Workers in North Chinese Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China. 2021. Suspended death! Beijing Chaoyang Hospital Cui Zhenguo’s medical case was sentenced in the first instance. March 2. Available online: https://www.spp.gov.cn/zdgz/202102/t20210203_508352.shtml (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China. 2022. 2021 Work Report of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. March 15. Available online: https://www.spp.gov.cn/spp/gzbg/202203/t20220315_549267.shtml (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China. 2023. 2022 Work Report of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. March 17. Available online: https://www.spp.gov.cn/spp/gzbg/202303/t20230317_608767.shtml (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Turkel, Gerald. 1990. Michel Foucault: Law, Power, and Knowledge. Journal of Law and Society 17: 170–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Mengxiao, Gordon G. Liu, Hanqing Zhao, Thomas Butt, Maorui Yang, and Yujie Cui. 2020. The Role of Mediation in Solving Medical Disputes in China. BMC Health Services Research 20: 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Rui. 2015. On the Risk Prevention Function of Justice in the Context of Risk Society. Journal of Lanzhou University (Social Sciences) 43: 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Yexin, and Mingjian Yuan. 2017. Governance of Doctor-Patient Conflict: The Absence of the rule of law and Its Correction—An Interpretative Framework Based on Identity Conflict. Journal of Social Sciences 12: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Ming. 2020. Reflection and Improvement: Multiple Legal Governance in Medical Disputes. Zheng Fa Lun Cong 2: 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Zehua. 2023. The Interaction between Doctor-Patient Communication Duration and Doctors’ Perceptions of Sei-Tech Efficiency and Doctor-Patient Conflicts. Social Development Research 10: 84–102, 239–240. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Liangchun, and Huimin Liu. 2020. Stakeholders, Healthcare Equity and the Reform of China’s Healthcare System. Shandong Social Sciences 7: 125–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Boyuan. 2016. Transformation of China’s Medical Risk Governance Model and Institutional Construction—An Appraisal of the Regulations on the Prevention and Handling of Medical Disputes. Hebei Law Science 34: 114–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xin, Min Huang, Maorui Yang, Qunhong Wu, Hongkun Ma, Kai Xing, Ying Zhang, and Yalan Wang. 2021. Trends in Workplace Violence Involving Health care Professionals in China from 2000 to 2020: A review. Medical Science Monitor 27: e928393-1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Min. 2011. Evaluation of the third-party mediation mechanism for medical disputes in China. Med. & L. 30: 401–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Peiling, and Sue C. Grady. 2016. Three Modes of Power Operation: Understanding Doctor-Patient Conflicts in China’s Hospital Therapeutic Landscapes. Health & Place 42: 137–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).