Abstract

Competent management of the production and consumption of waste is the foundation for ensuring a favorable environment in cities and comfortable living conditions for the population. Laws and regulations play a key role in this process since they determine measures aimed at creating conditions for safe waste management, an effective management system in the field of environmental protection from waste pollution. In the cities of many developing countries, including Russia, despite the efforts being made, there is an increase in the volume of municipal solid waste. Solving the problems of waste management has been set as a national task. The article analyzes the current condition of solid waste management systems in developed and developing countries and identifies the features and prospects of waste management, including the one in Russia. It is established that the existing set of organizational, sanitary, and legal measures, and legal regulation of relations and law enforcement practices in the field of solid municipal waste management in many developing countries is still in the forming stage. The positive experiences of countries in implementing sustainable systems of safe waste management and the positions of judicial bodies on controversial issues of waste management in cities can be used as the basis for an environmental policy of safe waste management at all levels of public authority, as well as improving legislation in the field of waste management.

1. Introduction

Various facilities used for economic and other activities that meet the diverse needs of the population and serve as sources of waste generation are concentrated in cities. Uncontrolled municipal solid-waste landfills are also sources of pollution. Waste can be found both in urban and adjacent areas. Occupying hectares of the city’s territory, it negatively affects not only the natural environment but also human health and endangers the comfortable living conditions of the population, causing an increase in consumption. Accordingly, there is a need to effectively use and manage both waste and resources (Filho et al. 2016; Lisina 2020; Bello et al. 2022).

Waste generation rates are growing rapidly in most cities of the world (Krivul’kin and Efremova 2018; Yousefloo and Babazadeh 2020). Due to population growth and urbanization, waste volumes may increase by up to 70% by 2050 (UNEP and IWMA 2015; Kaza et al. 2018). Approximately 33% of municipal solid waste generated worldwide is irrationally used; as a rule, open burial or incineration is used (Levin 2019; Sokolov et al. 2019). According to experts, already in 2016, 2.01 billion tons of solid municipal waste were accumulated in cities around the world and amounted to an average of 0.74 kg/day per person (Kaza et al. 2018). According to the authors (Soni et al. 2022), about 0.64, 0.14, 0.13, and 0.10 million tons are generated daily in the USA, Germany, Mexico, and Japan, respectively. It has been established that in developed countries the level of solid waste generation depends on GDP per capita (Li et al. 2016), and for developing and poorly developed countries there is no such dependence (Kawai and Tasaki 2016). Undeveloped, developing, and developed countries are responsible for 23%, 37%, and 40% of global waste generation (Kolekar et al. 2017).

In many developed countries of the world, the policy of the last decades has been aimed at preventing waste generation and promoting recycling. This makes it possible to reduce the environmental burden throughout the life cycle of municipal waste, as well as to benefit more from resources and create additional jobs (Eurostat 2016; Malinauskaite et al. 2017; Ayodele et al. 2018).

Depending on the level of socioeconomic development of countries, municipal solid waste differs by composition (Alzamora and Barros 2020; Soni et al. 2022). For example, in low-income countries, organic waste prevails (56%), while wood, glass, rubber, leather, etc. account for up to 1% of the total waste generated. For the high-income population, organic waste (32%), paper/cardboard (25%), and plastic (13%) make up the biggest part of the total volume of municipal waste generated; wood, rubber, and leather are represented to a lesser extent, 4% of each type (UNEP and IWMA 2015). The study (Soni et al. 2022) provides details of the differences between the types of solid household waste (paper, textiles, plastic, glass, metals, organic waste, and others) of cities in the USA, the European Union, and developing countries (on average for the selected group). Paper, textiles, plastics, and metals predominate in the waste of US cities; glass and other types of waste—in the EU; plastic and organic waste—in developing countries.

In the studies (Pappu et al. 2007; Castaldi et al. 2017), a significant difference was found in the characteristics and quantity of existing solid waste depending on the economic status, standard of living, and level of culture and literacy of the population. According to the authors (Soni et al. 2022), by 2025, the amount of solid waste will remain virtually unchanged in France, South Africa, and the UK; will decrease in Germany and Italy; and will increase in the rest of the reviewed countries (Japan, Brazil, Russia, India, China, Egypt, Iran, Kenya, Nigeria, and Indonesia) compared to the same indicator in 2012.

Different countries are trying to develop their own management strategies in the field of municipal waste management aimed at reducing the volume of waste disposal and its sustainable use. Experts note that the sustainable methods of managing and processing municipal solid waste are those in which the generated waste is not accumulated, but completely extracted, reused, and recycled (Bello et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2022).

For almost 20 years in Europe, environmental policies have been implemented aimed at preventing waste generation, recycling, reuse, prohibition, and/or restriction of waste burial. Municipal waste management is based on these strategic objectives aimed at its intensive processing1. On average, only a quarter of the total volume of solid municipal waste from European countries is subject to burial. There is no single approach to existing waste disposal methods among the EU countries. There are European countries where the municipal-waste disposal rate is zero (Switzerland) or is a minimum of 3–5% (Sweden, Germany, and Belgium) of the total volume of solid waste generated, or half of the waste generated is subject to burial (Spain) (Gallardo et al. 2021; Chioatto and Sospiro 2023).

The United States ranks first in the world in terms of municipal waste generation. At the same time, only a third of the waste is sent for recycling, 13% is incinerated at specialized power plants, and the rest is buried (Shilkina 2020; Soni et al. 2022).

Japan has chosen to limit the disposal of municipal waste (no more than 5% of the total volume), the vast majority of waste is sent for recycling or incineration, provided that the garbage is sorted by the population in advance. Japan is known for a special way of garbage disposal—the construction of islands from the remains of garbage after its incineration (Amemiya 2018). China is gradually moving from importing and/or dumping waste to incineration (Zhu et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2021).

For comparison, the population of Japan is comparable to the population of Russia, while the area is 45 times smaller. However, approximately equal volumes of waste are generated in the territories of these countries per year (44.5 million tons in Japan and 56.5 million tons in Russia). At the same time, in Japan, 72% of waste is incinerated at 1900 incinerators, and in Russia 2.4%—at 10 facilities (Shilkina 2020).

Despite the significant area of the territory and the predominance of industrial production, in Russia over the past few years, amid a significant decrease in the volume of waste of hazard classes I–III, there has been an increase in the total amount of less hazardous waste including municipal solid waste. Certain regions are distinguished by specific types of waste caused by the predominance of a certain branch of the economy, economic, or other activity2. For the Russian Federation, the formation of an integrated system for the management of solid municipal waste, and the creation of a modern infrastructure for the safe management of extremely hazardous and high-risk waste3 is recognized as a priority task. Since 1998, more than a thousand regulatory legal acts and documents have been adopted that create a legal basis for the management of production and consumption waste including solid municipal waste. The Federal Law No. 89-FZ of 24 June 1998 “On Production and Consumption Waste”4 is the framework law. However, the very concept of “production and consumption waste” still remains unclear. Those measures that are not aimed at reducing the volume of waste and not at its processing, but at ensuring its safe handling, prevail. Preventive measures are poorly developed, and the powers of local governments in the field of waste management are limited. This determined the need for a study of the waste management system in Russia, the results of which revealed an obvious legal dissonance between the state of legal regulation and applied practice, as well as the shortcomings of legal regulation that can be eliminated only by using the best practices of certain countries in the field of waste management.

Despite the positive experience and developments of many legal acts regulating waste management relations, even in developed countries, no more than 20% of all solid household waste is recycled. A significant part of this waste is placed in landfills or buried in the ground. In the United States, they are only planning to reduce this figure by almost half to 25% in the near future. In developing or underdeveloped countries, this percentage is significantly higher (Soni et al. 2022). The problem is felt in both developed and developing countries (Acerbi et al. 2022). European countries are showing different trends with regard to waste (Rogoff 2019), and countries that have implemented waste disposal and incineration directives are showing encouraging results but are increasing the gap with countries that have postponed such measures (D’Adamo et al. 2022). Moreover, some developed countries (USA, Canada, Australia, and some European countries) export their garbage to poorly developed countries instead of effective resource management (Patil and Ramakrishna 2020). What is holding back the widespread formation of a safe and efficient waste management system? Perhaps this is hindered by bureaucracy or lack of funding, political will, culture and education of the country’s population, or the development of the necessary infrastructure. This study is aimed at collecting information on various legal aspects of sustainable waste management. The purpose of the study is to make a comparative review of the current state of the solid waste management system in the geographical focus of developed and developing countries, including Russia, to identify the features and prospects of waste management, and to develop recommendations for improving the legislative framework for safe waste management, and also to analyze the issues of prevention of waste generation, waste removal, reduction of negative impact on the environment, ensuring safety, use of useful ingredients, suppression of criminal acts (for example, illegal dumping of waste, the illegal establishment of enterprises for processing or storing hazardous waste transported from developed countries to developing countries), and other issues that are relevant for all countries without exception and for the global community as a whole.

2. Legal Aspects, Policies, Practices, and Achievements in Waste Management in Different Countries

The waste management system in developed countries forms the basis of environmental strategic planning and is aimed at minimizing waste generation, reducing the volume of its burying, and increasing the rate of waste recycling (Chioatto and Sospiro 2023; Yang et al. 2023). Thus, the EU’s waste policy is aimed at protecting the environment and human health and facilitating the EU’s transition to a closed-loop economy. It sets goals and objectives for improving waste management, stimulating innovations in the field of recycling, and limiting waste burial. The Waste Framework Directive is the EU legal framework for waste management. On the territory of the European Union, an order of preference for waste management is being introduced. It is called the “waste hierarchy” and is based on waste generation prevention, reuse, and recycling (Zhang et al. 2022). The management is based on the establishment of requirements for the handling of certain types of waste (batteries and accumulators, biodegradable types of waste, landfill waste, construction and dismantling waste, transport waste with expired service life, packaging waste, polychlorinated biphenyls and terphenyls, mining waste, sewage sludge, etc.)5.

New approaches to waste management are reflected in the concepts of state development: in Japan (The New Growth Strategy6), the UK (UK Low Carbon Industrial Strategy7), South Korea (Low Carbon Green Growth8), the Green Growth Strategy has been adopted; in China9 (PRC Law on the Prevention and Control of Environmental Pollution by Solid Wastes10), in the USA (Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA)11, and the European Union,12, legislative acts have been developed to promote the closed-loop economy (Kafle et al. 2017; Nyangchak 2022).

RCRA gives the US Environmental Protection Agency the right to control hazardous waste from “cradle to grave”. This includes the generation, transportation, processing, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste. To achieve this goal, the Environmental Protection Agency is developing regulations, guidelines, and policies to ensure the safe management and treatment of solid and hazardous waste, as well as programs that encourage source reduction and beneficial recycling (Barton and Ainerua 2020).

The PRC Law on the Prevention and Control of Environmental Pollution by Solid Wastes was adopted in 1995, and it was amended in 2004, 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2020, respectively. The latest version came into force on 1 September 2020. This law applies to the prevention and control of environmental pollution by solid waste. This law does not apply to the prevention and control of marine pollution by solid waste and environmental pollution by solid radioactive waste. The country applies a classification system for household waste. It is prohibited to dump, store, or dispose of any solid waste from abroad in China. The state is gradually implementing zero import of solid waste (Mantsurov 2016).

The basic principles of the closed-loop economy are based on the renewal of resources, the processing of secondary raw materials, and the transition from fossil fuels to the use of renewable energy sources, and contain various interrelated stages13. In the Chinese context, the closed-loop economy is aimed at reduction, reuse, and recycling. At the legislative level, the beginning of the implementation of state policy is associated with the adoption of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Promotion of a Closed-loop Economy in 2008 (Pesce et al. 2020). These efforts have led to the development of a set of measures to generate flows of valuable resources, improve production efficiency and environmental indicators, prevent waste destruction, and form the foundations of sustainable waste management.

Accordingly, laws and/or directives have been developed for the management of certain types of waste. These include Directive 94/62/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 20 December 1994 on packaging and packaging waste14, Directive 2006/66/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 6 September 2006 on batteries and accumulators and spent batteries and accumulators, repealing Directive 91/157/EEC15, Council Directive 86/278/EEC of 12 June 1986 on the protection of the environment and, in particular, the soil when using sewage sludge in agriculture16, and others. The priority direction of the environmental policy of the EU countries and the world is the establishment of targets for the reduction of food and other industrial waste. It focuses on the following policy areas: prevention (including reduction of food waste), separate collection (waste oils and textiles), as well as the application of the waste hierarchy and the “polluter pays” principle. An important way to achieve the targets for reducing food waste should be to create incentives for changing consumer behavior17.

Within the framework of the strategic goals and objectives defined by the EU waste management directives, Some EU countries approve their own programs taking into account priority issues. The Italian and French programs have been developed based on the Spanish legislative model for reducing food waste. The models aim to achieve a 50% reduction in food waste per capita in retail and consumer sales and a 20% reduction in food losses along production and supply chains by 2030 compared to 2020 (Gómez-Urquijo 2022). The Irish Closed-Loop Economy Program (2021–2027) is the driving force behind Ireland’s transition to a closed-loop economy. The concept of the EPA-led Program in Ireland is that a closed-loop economy ensures that everyone uses fewer resources and prevents waste to achieve sustainable economic growth. This program includes and is based on the National Waste Prevention Program. The focus in Ireland is on reducing the amount of raw materials used and maximizing the cost of materials throughout the production and consumption chain. Waste is recycled wherever possible and returned to production processes. Otherwise, it is used for energy production instead of disposal in a landfill.

Experts note that in the European Union, there is a highly developed legislative framework for waste management, in which the waste hierarchy is a guiding principle, and integrated sustainable waste management is encouraged, while waste is considered primarily as a resource (Filho et al. 2016).

Since 1972, in order to improve the waste management system, European countries began to switch to the principle of extended producer responsibility after the adoption of international environmental obligations within the framework of the 1972 United Nations Stockholm Conference. The Extended Producer Responsibility Policy18 (EPR) is characterized by the fact that at the end of the product’s service life, responsibility for its environmental impact is assigned to the original manufacturer or seller of such a product. In fact, EPR is a continuation of the well-known “polluter pays” principle and is aimed at ensuring that the manufacturer (seller) assumes responsibility for those products whose shelf life (use) has expired. Thus, the manufacturer (seller) is forced to take measures to reduce waste by improving the mechanisms of product reuse.

The EPR principle was introduced in 1994 in Sweden, the producer responsibility legislation contains legal requirements for liability in relation to various goods and products (printed publications, packaging, vehicles, etc.). In the UK and Germany, there are also laws on the responsibility of the manufacturer for packaging (and its processing) and on the “return” of packaging, based on the EPR principle. The laws of these countries provide for a set of measures aimed at implementing the EPR principle. They are focused on improving the reuse of the product and/or packaging, reducing the number (volumes) of products and the volume of materials used, as well as attracting interested parties to activities in the field of “design for the environment” (Chandrappa and Das 2012, pp. 39–40). Activities to implement the EPR principle are stimulated by recycling subsidies, bans on waste disposal, recycling targets, pricing of waste collection and/or disposal, promotion of reuse of products and packaging, and other measures.

The organization of a system of education and upbringing in the field of waste management is of great importance in European countries. For example, in Switzerland, waste management issues, including garbage sorting, are studied in schools from the first grade. City residents have the right to choose the form of accumulation and collection of waste—separate or not. There are about fifty types of waste collection in Switzerland, depending on the type of waste (Erhardt 2019). Plastic bottles, paper, cardboard, glass, wine bottle corks, foil coffee capsules, etc. are collected separately. For common types of waste, containers are located on specially equipped street areas near houses or supermarkets, and for some at special collection points (stations); for certain types of waste, a special vehicle moves through settlements on a certain day and at a certain time (for example, to collect Christmas trees in early January), types of waste that are not recyclable should be collected in separate special packages that are purchased in stores, and the proceeds from their sale are directed to waste management. If a citizen has decided not to sort any waste at all, then they are obliged to purchase special packages for “unsorted” waste every time they throw it away. A person who discards waste not in a special package faces a high fine (50–200 francs). The regulatory authorities are working very effectively in this direction. Of the total amount of waste thrown out by the Swiss population after sorting at sorting stations in the future, one half (usually paper, cardboard, glass, household appliances, fabric, plastic bottles, aluminum cans, batteries, some food waste, etc.) is recycled, and the other half is incinerated at thirty incinerators with advanced purification systems. Waste burial in Switzerland has been prohibited since the late 1980s. Thus, since 1986 (adoption of the Waste Management Guidelines (BUVAL), Switzerland has moved to a new level of solving problems in the field of waste management, creating a favorable environment and improving the quality of life of the population of its cities (Lisina 2020).

In developed countries, the proper organization of the waste management system, including the management of places (territories) of disposal, is important in ensuring safe waste management. Some countries have completely abandoned waste burial, while others have learned how to properly equip waste disposal facilities, form sustainable operational practices, control the type of waste accepted for burial, process filtrate before unloading, collect methane, and so on (Ludwing et al. 2012).

Waste management areas are not easy to unify since the territories, climate, and production processes are different. While cities with higher incomes are used to operating on the “use and throw away” principle, cities and regions with lower incomes tend to reuse waste or produce less waste. There is also an imbalance between different countries in the consumption of resources and waste generation (they can adopt “clean” technologies but use a lot of packaging), in determining priorities (for some, the fight against solid municipal waste is one of the priority problems, while others are concerned about the problems of hunger, water shortage, war, and other similar circumstances) (Chandrappa and Das 2012, pp. 22–23).

Despite the difficulties of management in the field of solid waste management, many developed countries are striving to build an integrated solid waste management system (ISWM), including legal, technical, political, environmental, socioeconomic, and cultural aspects (Kumar 2016). The ISWM system is a comprehensive waste management system, including a program for waste prevention, recycling, treatment, and disposal. When developing a waste management program, various factors (institutional, financial, economic, social, legal, technical, and environmental) are taken into account19.

ISWM includes three basic components: prevention, recycling, and disposal. This management system is carried out at all stages of economic and other activities, starting from the planning and design of an object of economic and other activities, ending with the decommissioning of the object. The main directions of waste management are public assessment (PA), environmental impact assessment, strategic environmental assessment, socioeconomic assessment, and sustainability assessment (SA).

The waste life cycle assessment (LCA) is an important preventive measure of environmental protection in the ISWM management system. It represents a holistic approach to waste prevention by analyzing the service life of a product (activity process), including the procurement of raw materials, storage of raw materials, production, storage of products, transportation, distribution, use, reuse, maintenance, waste recycling, waste storage, waste transportation, waste disposal, and removal. However, experts underline the problem of the objectivity of LCA reports due to economic interests (for example, in relation to cigarettes, alcohol, crackers, etc.) (Chandrappa and Das 2012, pp. 37–38).

In many countries, such as China and other Asian countries, implementing the ISWM system of effective waste management, criminal liability is only provided for violation of the requirements of legislation in the field of waste management. At the same time, a significant preventive measure is a principle of “natural justice”, according to which, if a violation of the requirements of legislation in the field of waste management is detected, the violator is first warned about the violation, they are given the opportunity to correct the situation, and only then criminal punishment follows. A mechanism similar to the implementation of the principle of “natural justice” has also been introduced into Russian legislation regulating the procedure for state control (supervision).

The USA occupies a leading place in the world in terms of annual volumes of solid household waste, among which 37.4% is paper and 11.2% is organic waste. The waste management policy is aimed at reducing primary solid household waste by sorting waste by the population and recycling it. By 2030, the United States should abandon the burial of household waste (Bello et al. 2022).

The US experience on the distribution of costs for the restoration of the disturbed environment as a result of damage caused to it or its components after waste disposal is interesting. In the event that waste is generated, or pollution occurs as a result of industrial activity, the responsibility for the consequences always lies with the producer of waste or pollution, since the right to waste cannot be transferred. In the case when the landfill operator accepts the waste for final disposal, there is a risk that the waste may contaminate the groundwater due to a violation of the lining of the landfill. Both the landfill operator and the waste producer bear the burden of responsibility for the restoration of damage; thus the costs of restoration are distributed. However, this practice is not widespread in the world.

In Japan, the basis of waste management is a good regulatory framework. Laws have been adopted in various areas of waste management, with special attention paid to waste management and public cleaning (WMPC), promoting the efficient use of resources, recycling of containers and packaging, recycling of household utensils and household appliances, recycling of building materials, food processing, and green procurement (Bello et al. 2022). Japan is one of the first countries to introduce extended producer responsibility and advanced rules (along with South Korea) for the management of electronic waste (Rajesh et al. 2022). At the same time, Japan has taken the path of burning most of the solid waste generated and disposing of garbage on artificial islands created from it. Special attention is paid to the environmental upbringing and education of the Japanese.

Along with environmental education and training in waste management, to which much attention is paid, in developed countries, tools for waste management awareness, monitoring activities in the field of waste management, licensing, and accounting systems, stimulating safe waste management, including the introduction of a “return system” (DRS, involving payment of the deposit included in the cost of the goods by the consumer, that (deposit) will be returned to them when transferring waste (cans, bottles, etc.) for reuse; for example, in Australia, 10–15% of the cost of the bottle is the deposit amount) that finances the implementation of projects for safe waste management (through budgets of different levels, grants, user fees, pollution fines) (Chandrappa and Das 2012, pp. 50–52).

A country with one of the largest economies In the world, Russia, has huge growth potential in the household waste management industry due to its poorly developed infrastructure. Within a year of raids, Rosprirodnadzor employees identified 33.5 thousand illegal landfills. Every year, the volume of household waste in Russia increases by 50 million tons, of which Moscow has almost 20%. It is not surprising that in the capital, as in the whole country, the situation is complicated and requires radical solutions. Almost 60% of all landfills are located within settlement borders and, according to the latest data, the total amount of accumulated waste in Russia exceeds 30,000 million tons. To date, in Russia, a country with 83 territorial subjects, 9 time zones, and bordering 18 countries, “there are less than 400 enterprises for sorting and disposing of solid household waste and 1092 landfills” (Zamyslov 2014).

Many types of waste are well amenable to neutralization and recycling for the purpose of its further disposal, but the level of use of such waste remains still low. The problems hindering the development of the market for recycled material resources can be divided into technical and technological, organizational and managerial, and economic and informational.

Article 3 “Basic principles and priority directions of state policy in the field of waste management” (ed. Federal Law No. 458-FZ of 29 December 2014)20: states that the directions of state policy in the field of waste management are the priority in the following sequence:

- (1)

- maximum use of raw materials;

- (2)

- prevention of waste generation;

- (3)

- reduction of waste generation and reduction of the hazard class of waste in the sources of its formation;

- (4)

- waste treatment;

- (5)

- waste disposal;

- (6)

- waste neutralization.

Thus, state policy should be aimed at minimizing waste burial, but statistics say quite the opposite, and almost all accumulated waste is buried in most regions (Sidyagin and Vesnin 2016).

The bases of administrative and legal regulation for the procedure for handling production and consumption waste are the norms of the Constitution of the Russian Federation21, Article 42 of which provides that everyone has the right to a favorable environment, reliable information about its condition, and compensation for damage caused to their health or property by an environmental offense, in addition, everyone is obliged to preserve nature and the environment, take care of natural resources (v. 58).

In addition, the federal law “On Environmental Protection” dated 10 January 2002 No. 7-FZ (hereinafter—FZ No. 7-FZ)22. establishes similar provisions in the sphere of respect for natural resources, which are the basis of sustainable development, life, and activities of the peoples living on the territory of the Russian Federation. It also defines the legal basis of the state policy in the field of environmental protection, ensuring a balanced solution to socioeconomic problems, the preservation of a favorable environment, biological diversity, and natural resources in order to meet the needs of present and future generations, strengthening the rule of law in the field of environmental protection and environmental safety.

At the same time, the legal basis for the management of production and consumption waste in order to prevent the harmful effects of production and consumption waste on human health and the environment, as well as the involvement of such waste in economic turnover as an additional source of raw materials is determined by the federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste” dated 24 June 1998 No. 89-FZ (hereinafter—Federal Law No. 89-FZ), namely, production and consumption waste (hereinafter referred to as waste)—substances or objects formed in the process of production, the performance of works, provision of services, or in the process of consumption, which are removed, intended for removal, or are subject to removal in accordance with Federal Law No. 89-FZ.

It should be noted that as a result of waste processing, a product may be formed that does not belong to waste, but is a product of processing, i.e., in this case, the subject cannot bear administrative responsibility for violating the provisions of Article 8.2 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation. Thus, substances and materials formed as a result of production activities can be sold as products if the company has the appropriate technical conditions and documentation, and the developed regulatory and/or technical documentation for products must take into account the requirements of relevant state and industry standards, sanitary-epidemiological, and environmental standards.

For example, Part 1 of Article 8.2 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation provides for administrative liability for noncompliance with environmental protection requirements during the collection, accumulation, transportation, processing, disposal, or neutralization of production and consumption waste, with the exception of cases provided for in Article 8.2.3 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation, in the form of an administrative fine for citizens in the amount of 1000 to 2000 rubles, for officials—from 10,000 to 30,000 rubles; for persons engaged in entrepreneurial activity without forming a legal entity—from 30,000 to 50,000 rubles or administrative suspension of activity for up to 90 days; for legal entities—from 100,000 to 250,000 rubles or administrative suspension of activity for up to 90 days.

In addition, Part 4 of Article 8.2 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation provides for administrative liability for noncompliance with environmental protection requirements for the disposal of production and consumption waste, with the exception of cases provided for in Article 8.2.3 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation, in the form of a fine for citizens in the amount of 3000 to 5000 rubles; for officials—from 20,000 to 40,000 rubles; for persons engaged in entrepreneurial activity without the formation of a legal entity—from 40,000 to 50,000 rubles or administrative suspension of activity for up to 90 days; for legal entities—from 300,000 to 400,000 rubles or administrative suspension of activity for up to 90 days.

In the event that these actions (inaction) caused harm to human health or the environment, or the occurrence of an epidemic or epizootic, if these actions (inaction) do not contain a criminally punishable act, Part 6 of Article 8.2 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation provides for administrative liability in the form of an administrative fine for citizens in the amount of 6000 to 7000 rubles; for officials—from 50,000 to 60,000 rubles; for persons engaged in entrepreneurial activity without forming a legal entity—from 60,000 to 70,000 rubles or administrative suspension of activity for up to 90 days; for legal entities—from 600,000 to 700,000 rubles or administrative suspension of activity for up to 90 days.

In the law enforcement practice of Article 8.2 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation, there is a competition of jurisdiction, since there are judicial acts indicating public interests protected by this article (as well as in general by Chapter 8 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation) that are in no way related to entrepreneurial or other economic activity and, therefore, disputes related to bringing to administrative responsibility are not subordinate to arbitration courts, since the object of offenses, the compositions of which are formulated in Chapter 8 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation (and, in particular, in Article 8.2 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation), are public relations in the field of ensuring the order of waste management, and the objective side of such offenses is formed by actions (inaction) consisting of a violation of nature management and the requirements of legislation on environmental protection (as well as the rules and requirements of waste management). In other words, the commission of actions (inaction) that form the objective side of the offense provided for in Article (part of Article) of Chapter 8 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation, in any case, constitutes a violation of public law, namely the rules governing public relations regarding the protection of environmental objects that are not related in any way to the implementation of entrepreneurial or other economic activities by individuals and organizations.

At the same time, only a person who has a corresponding obligation to comply with the requirements of legislation in the field of environmental protection in the field of industrial and household waste management can be held liable, i.e., an unassisted person cannot be brought to administrative responsibility under Article 8.2 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation. Attention should also be paid to the specifics of bringing public entities (state authorities and local self-government bodies) to administrative responsibility under Article 8.2 of the Administrative Code of the Russian Federation.

By virtue of Clause 3 of Article 8 of Federal Law No. 89-FZ and Clause 3 of Article 7 of Federal Law No. 7-FZ and Clause 18 of Parts 1, 3 and 4 of Article 14 of Federal Law No. 131-FZ of 6 October 2003 “On General Principles of Organization of Local Self-Government in the Russian Federation”23 the powers of local self-government bodies of a municipal district in the field of waste management includes participation in the organization of activities for the collection (including separate collection) and transportation of solid municipal waste.

According to the statistics of the Judicial Department at the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation, for the 1st half of 2022, 857 cases of this category were received by the courts of general jurisdiction, a total of 809 cases were considered; 458 persons were brought to justice, of which: legal entities—215, officials—53, persons engaged in entrepreneurial activity without the formation of a legal entity—73, and other individuals—117; for which a penalty was imposed in the form of a warning—29, a fine—375, and suspension of activity—54; fines were imposed in the amount of 14,614,600 rubles, of which forcibly collected or paid voluntarily—4,274,600 rubles.24 However, in 2018, the courts of general jurisdiction received 2133 of this category, and a total of 2137 cases were considered; 1367 persons were brought to justice, of which: 753 legal entities, 174 officials, 175 persons engaged in entrepreneurial activity without forming a legal entity, and 265 other individuals; for which a penalty was imposed in the form of a warning—71, a fine—1027, and suspension of activity—269; fines in the amount of 39,157,200 rubles were imposed, of which 12,228,000 rubles were collected forcibly or paid voluntarily.25 And in 2017, the courts of general jurisdiction received 2034 of this category, a total of 2038 cases were considered; 1296 persons were brought to justice, of which: legal entities—673, officials—180, persons engaged in entrepreneurial activity without forming a legal entity—135, and other individuals—308; for which a penalty was imposed in the form of a warning—46, a fine—1014, and suspension of activity—236; fines in the amount of 37,731,200 rubles were imposed, of which 9,811,836 rubles were collected forcibly or paid voluntarily26.

As we can see, the number of administrative offenses in this category is characterized by stability and dynamics, which indicates the insufficient effectiveness of administrative and tort regulation in this area of legal relations, the presence of administrative penalties that do not have a sufficient preventive or deterrent effect, a low percentage of execution of punishments, which, in turn, violates the principle of inevitability of punishment, since the amounts of administrative fines that are collected or paid voluntarily are 15–20% on average, which means it requires a radical rethinking of the system of approaches to administrative and tort regulation of relations in this area and the development of new preventive measures (Antonova and Evsikova 2020).

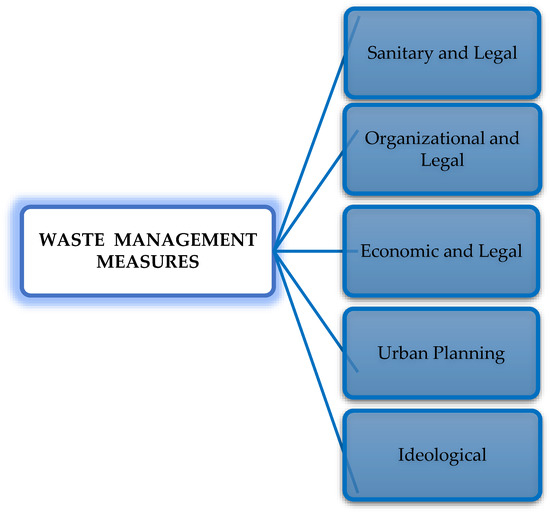

Public tasks in the field of safe waste management in cities are provided by a set of measures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Measures for safe waste management in cities.

Sanitary and legal measures establish requirements for the sanitary cleaning of urban areas, neutralization and safe disposal of production and consumption waste in the planning and construction of cities, for waste disposal facilities including the arrangement of places of accumulation of solid municipal waste, as well as requirements for the solid municipal waste management.

Organizational and legal measures include legal instruments that form the content of waste management. These include information support in the field of waste management, accounting and reporting, monitoring of the state and pollution of the environment on the territory of waste disposal facilities, state environmental supervision and control in the field of waste management and in the field of regulation of tariffs for solid municipal waste management, as well as licensing and rationing in the field of waste management (including disposal of waste from the use of goods), standards for the accumulation of solid municipal waste, legal liability for violation of the legal requirements in the field of waste management, and elimination of accumulated damage in the field of waste management, etc.

Economic and legal measures include legal measures that stimulate the activities of entities engaged in economic and other activities to minimize waste generation, utilization fees, payments for negative environmental impact through waste disposal, pricing system, and tariffs in the field of solid municipal waste management, etc.

Urban planning measures include taking into account the schemes of territorial waste disposal when planning the development of urban areas, the establishment of urban planning regulations for industrial zones and special purpose zones, and the regulation of the design and construction of waste management facilities. They are provided for by urban development legislation. Local self-government bodies should actively participate in this.

Ideological measures consist of ensuring an increase in the level of ecological culture of the subjects of environmental–legal relations in the field of production and consumption waste management (Lisina 2020).

In the Russian Federation, the most developed legal measures for environmental protection are organizational, legal, and sanitary measures. Among them, those that are aimed at ensuring safe waste management rather than reducing waste volumes, prevail. Such legal measures as restrictions and prohibitions on waste to be disposed of27, the principle of “extended responsibility”, and activities for the separate collection of municipal solid waste need to be developed.

Articles 8 and 8 1 of the federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste” provide for legal measures in the field of waste management carried out by local self-government authorities. They are responsible for organizing the management of solid municipal waste. Thus, local self-government authorities are obliged to determine the layout of places (sites) for the accumulation of solid municipal waste and keep their registration in accordance with established sanitary rules and regulations28.

The problems of solid municipal waste management are difficult to solve due to legislative shortcomings. As noted, (Ignatieva 2018), there is still ambiguity even in the very understanding of the term production and consumption waste. In accordance with Article 1 of the federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste”, solid municipal waste includes waste that is generated in residential premises during consumption by individuals; goods that have lost their consumer properties during their use by individuals in residential premises in order to meet personal and household needs; waste that is generated in the course of activity of legal entities and individual entrepreneurs and similar in composition to waste generated in residential premises during consumption by individuals.

The condition for recognizing municipal waste is its “consumption”. The legislator does not define this term. It is unclear whether its physical consumption is legally significant or not. It is wrong that the legislator restricts such consumption to an individual in a residential building. In fact, such consumption is possible in nonresidential premises. As a condition for recognizing an object as solid municipal waste, the loss of consumer properties of goods is also questionable since anything, including those that have retained useful properties, can be thrown away by a person. Since it is not possible to predict which physical object can be legally recognized as waste, the legislative decision of a number of countries such as Singapore and India on the expanded understanding of waste is valid.

For example, according to the law “On Environmental Protection” (Singapore, 1968), the term “waste” includes (a) any substance that is waste, waste water, or other unwanted excess substances resulting from the application of a process; (b) any substance or product that needs to be disposed of as broken, worn out, contaminated or otherwise damaged; (c) anything that is disposed of or otherwise treated as if it were waste is considered waste unless proven otherwise (Chandrappa and Das 2012, p. 22). In the Municipal Solid Waste Regulations (India, 1999), solid household waste is understood as commercial and household waste generated in a municipal or fixed (subordinate) area in solid or semisolid form, with the exception of industrial hazardous waste, but including treated medical waste (Chandrappa and Das 2012, p. 22). Many countries have laws on solid waste or municipal solid waste. There are various terms such as “household waste”, “municipal solid waste”, “domestic wastewater”, etc.

In Russia, the term “solid municipal waste” was introduced into legislation to replace the previously existing concept of “solid household waste”, which, according to the authors (Ponomarev and Filatkina 2016), had a narrow understanding and content. Despite this, the concept of “solid household waste” can still be found in Russian federal legislation.

The term “municipal solid waste” can be found in the legislation of Singapore, which refers to all the waste, the generation and collection of which is carried out in urban areas. The Environmental Protection Agency (USA, 2008) defines municipal solid waste (MSW) as materials that are traditionally managed by municipalities through incineration, burial, recycling, or composting. In the law “On Environmental Protection” (Finland, 2002), the term “domestic wastewater” can be found. This includes wastewater from toilets, kitchens, offices, dairy farms, etc. In order to prevent pollution of the environment with “domestic” wastewater, this law requires property owners to install equipment for the treatment of such wastewater (Krassov 2014).

The shortcomings of the understanding of solid municipal waste in Russia are also indicated by the list of “Municipal waste, similar to municipal waste in production and in the provision of services to the population” (code 73000000000) as part of the Federal Classification Catalog of Waste approved by Rosprirodnadzor (Federal Service for Supervision of Natural Resource Usage)29. The list of municipal solid waste includes those wastes that may actually be dangerous to the environment and the health of the city’s population. For example, in addition to waste from residential and office premises, these include waste generated from the cleaning of settlement territories, waste from the disposal of landfills of solid municipal waste, waste from the cleaning of coastal facilities of ports, including water flushing systems of remote berthing devices contaminated with petroleum products.

Requirements in the field of waste management can be general and special. General legal requirements for waste management are provided for by the federal law “On Environmental Protection”30. Environmental protection from pollution by production and consumption waste is ensured by the establishment of legal requirements in the field of waste management at various stages of economic and other activities, in the field of environmental regulation, state environmental expertise, environmental control (supervision), etc. According to paragraph 1 of Article 44 of the federal law “On Environmental Protection”, when placing new settlements and their development, it is obligatory to comply with the requirements for ensuring the safe handling of production and consumption waste.

The federal laws “On Production and Consumption Waste” and “On sanitary and epidemiological welfare of the population”31 provide for special legal requirements for environmental protection in cities from waste pollution. Therefore, as established by articles 24 6—24 13 of the federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste”, special legal norms were established as mandatory requirements for the rules for the treatment of solid municipal waste (the need to develop uniform rules for the treatment and rules for charging activities for the treatment of solid municipal waste and pricing, requirements for regional operators for the treatment of solid municipal waste, features of concluding contracts for the provision of solid municipal waste management services, requirements for informing participants in legal relations in the field of solid municipal waste management, the procedure for control (supervision) in the field of tariff regulation in the field of solid municipal waste management, planning activities in the field of solid municipal waste management, and the principle of “extended responsibility” for solid municipal waste from the use of goods). In contrast to global practice, the principle of extended liability has been just recently introduced in the legislation of the Russian Federation.

In some countries, separate laws regulate the management of hazardous waste (Australia and India), the management of biomedical waste and solid household waste (India), waste management (Austria), disposal of household appliances (Japan), prevention (“avoidance”) of waste and natural resource recovery (Australia), and solid waste management (Cambodia).

In the Russian Federation, subordinate legal acts, including federal regulatory documents of the national standardization system, have a significant weight in the total volume of legal regulation of relations in this area. There are more than 65 federal regulatory documents in the field of production and consumption waste management. They were adopted by the authorized federal standardization body on various issues of managing the system of safe waste management (in particular, waste certification, construction waste disposal, maintenance of the outdoor space, collection and removal of household waste, and placement of landfills for waste disposal, etc.). Bylaws detail the provisions of federal laws that establish requirements for environmental protection in the field of waste management depending on the type of waste and the hazard class of waste (Figure 2), the type of economic and other activities, or the stage of economic and other activities; hence, the different legal requirements in the field of environmental protection from waste pollution. They provided for architectural and construction design, construction, reconstruction, capital repairs of buildings, structures, and other objects related to waste management, operation of buildings and structures related to waste management, waste disposal facilities and waste accumulation sites, waste transportation, and cross-border movement of waste.

Figure 2.

Classification of waste based on the degree of its negative impact on the environment.

The basic requirements for the collection, accumulation, transportation, processing, disposal, neutralization, and disposal of production and consumption waste in cities are provided for by the federal law “On Sanitary and Epidemiological Welfare of the Population”. They are detailed in sanitary and epidemiological rules and regulations (for example, Resolution No. 3 of the Chief State Sanitary Doctor of the Russian Federation dated 28 January 2021 “On Approval of Sanitary Rules and Regulations SanPiN 2.1.3684-21 “Sanitary and epidemiological requirements for the maintenance of urban and rural settlements, water bodies, drinking water and drinking water supply, atmospheric air, soils, residential premises, operation of industrial, public premises, organization and implementation of sanitary and anti-epidemic (preventive) measures””32), hygienic standards, veterinary and sanitary rules, methodological guidelines, and methodological recommendations.

For municipal solid waste, the legislation also establishes separate rules for its accumulation. There are legal requirements for the arrangement of places of accumulation of solid municipal waste with the possibility of separate storage of solid municipal waste by types of waste, waste groups, and groups of homogeneous waste; that is, separate accumulation.

The subjects of the Russian Federation independently establish standards for the accumulation of solid municipal waste, including standards related to its separate accumulation. The format of the source data for calculating the standards for the accumulation of solid municipal waste in the subjects of the Russian Federation may differ. For example, the Moscow Region has completely switched to a separate accumulation of municipal solid waste. The territory of the Moscow Region, including all its cities, is divided into seven clusters, for which standards for the accumulation of solid municipal waste are established, and a system for its collection is organized. At the same time, the administrative responsibility of operators for mixing waste during collection and further handling is established33.

In some subjects of the Russian Federation, accumulation standards are established for the entire territory of the subject as a whole, and in some—for municipalities of the subject of the Russian Federation. Standards for the accumulation of solid municipal waste can be set both in m3 and in kg per unit of account, which can be either one resident or 1 m2 of the total area, or both indicators can be used34.

These standards are the basis for calculating utility fees for solid municipal waste management. The method of accumulation of solid municipal waste, separate or not separate, affects the amount of this fee. The legislation35 establishes requirements according to which separate accumulation of solid municipal waste can affect the amount of utility fees only if the separate accumulation of solid municipal waste is organized. To do this, the state authority of the subject of the Russian Federation by a regulatory legal act must approve the procedure for the separate accumulation of solid municipal waste, and consumers must comply with it—perform the separation of solid municipal waste according to the types of waste and carry out the storage of sorted waste in separate containers for certain types of waste. Thus, the adoption of a decision by a state authority of a constituent entity of the Russian Federation establishing a separate accumulation of solid municipal waste is a mandatory legal condition for calculating utility fees for handling it based on a separate method of its accumulation. The subjects of the Russian Federation do not ignore these issues. They establish the procedure for its separate collection and accumulation (for example, Kemerovo region-Kuzbass, Moscow region, Sverdlovsk region, etc.).

Such stages of the solid municipal waste life cycle as collection, transportation, processing, disposal, neutralization, and burial on the territory of the subject of the Russian Federation are provided by regional operators in relation to the zone of activity defined for them. The current legislation does not limit the number of regional operators functioning on the territory of one subject of the Russian Federation. The subject of the Russian Federation must determine them according to the rules of competitive selection in accordance with the procedure established by Article 246 of the federal law “On the Conduct by Authorized Executive Authorities of the Subjects of the Russian Federation of a competitive selection of Regional Operators for the Management of Solid Municipal Waste”36. According to the results of the competitive selection, having assumed the duties of a regional operator, the latter are responsible for violations of the legal requirements for the sanitary maintenance of territories, organization of cleaning, and ensuring cleanliness and order in the city. Judicial practice shows that the contracts concluded by them for the provision of services in the field of solid municipal waste management do not exempt operators from the obligations provided for by legislation on environmental protection and on the sanitary and epidemiological welfare of the population.

The subjects of the Russian Federation play an important role in creating a management system in the field of safe waste management, including solid municipal waste. Safe waste management is carried out by the subjects of the Russian Federation through the planning and organization of activities in the field of waste management. The main documents of waste management planning and organization of the subjects of the Russian Federation are recognized as the regional program in the field of waste management and the territorial scheme in the field of waste management. The regional program defines the goals, objectives, measures for safe waste management, and sources of their financing. A description of the system of organization and implementation of activities for the safe management of waste that is generated and (or) received in the subject of the Russian Federation is contained in the territorial scheme.

One of the problems of law enforcement activities in the field of waste management is the alignment of these documents with territorial planning documents in the subject of the Russian Federation. The federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste” and the Urban Planning Code of the Russian Federation contain requirements for the preparation of a territorial scheme in the field of waste management based on territorial planning documents of a constituent entity of the Russian Federation. Thus, according to Article 14 of the Urban Planning Code of the Russian Federation37, materials on the justification of territorial planning documents of the subjects of the Russian Federation must contain information on the generation, recovery, neutralization, and placement of solid municipal waste contained in territorial schemes of waste management including solid municipal waste, as well as objects used for its recovery, neutralization, and burial and included in the territorial scheme in the field of waste management including solid municipal waste. However, in practice, the information contained in these documents is often contradictory and irrelevant.

At the same time, it is impossible to improve the safe waste management system outside the territory of cities in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation without solving other issues that are beyond the scope of regional planning of waste management activities. Issues related to the elimination of accumulated damage from waste and its prevention in the future, the ordering of unauthorized waste disposal sites since the laws prohibit the disposal of waste within the boundaries of settlements, in forest park zones, water protection zones, and in health and wellness areas and resorts are relevant for the subjects of Russia.

As part of the implementation of the federal national projects “Ecology” and “Clean Country”, as well as Industrial Development Strategies for the Processing, Disposal, and Neutralization of Production and Consumption Waste Until 203038, the subjects of the Russian Federation are developing investment programs in the field of waste management, which provide for measures for the construction of new facilities and the reconstruction of existing facilities for the treatment, neutralization, and disposal of waste, including municipal.

Moscow region demonstrates a positive experience. On its territory, measures are being taken to recultivate landfills of solid municipal waste and it is planned to build plants for thermal neutralization of waste with electricity generation. In the period from 2017 to 2021, 13 landfills were recultivated, of which 3 large landfills were recultivated in 2021, while in 2022, there were 4 more municipal solid waste landfills in the reclamation plans39. It is planned to build four plants for thermal waste disposal with electricity generation40.

In the Russian Federation, the effectiveness of waste management depends on its organization at the regional level. However, in global practice, the leading role in waste management belongs to local governments. In the Russian Federation, the powers of local self-government bodies in the field of ensuring safe waste management are limited. It is possible to distinguish two areas of activity of local self-government bodies in the field of waste, mainly municipal solid waste management.

The first direction determines the implementation of those powers of local self-government bodies that are directly attributed to their competence by law. The second direction is formed by the “powers of participation”, that is, local self-government bodies can participate in solving those issues that are attributed to the powers of state authorities. For example, the creation and maintenance of places (sites) for the accumulation of solid municipal waste, the definition of schemes for the placement of places (sites) for waste accumulation, and the maintenance of their register according to Article 8 of the federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste” are attributed to the powers of local self-government bodies of urban settlements and urban districts.

If there are legal disputes over the maintenance of places of accumulation of solid municipal waste and their arrangement, the designation of the entity obliged to carry out such activities (local governments, regional operators, or management companies), the courts in most cases decide that the maintenance of places of accumulation of solid municipal waste and their development falls within the competence of local governments and is their responsibility41. With regard to the implementation of duties to identify and eliminate unauthorized landfills on the territory of the city, the courts also adhere to a uniform position. The court decisions emphasize that even if a regional operator is designated in accordance with the established procedure, local governments are obliged to participate in the identification and liquidation of unauthorized landfills in the city.

The powers of local self-government bodies in accordance with Article 8 of the federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste” include the organization of environmental education and the formation of environmental culture in the field of solid municipal waste management among the population. Despite the existing legal norms on environmental education and culture, the Russian Federation only relatively recently began to promote the formation of an environmentally oriented worldview in the field of solid municipal waste management. In the development of the federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste” in municipalities in Russia, there is a practice of developing action plans for raising the environmental awareness of the population and the formation of environmental culture in the field of solid municipal waste management. Such events are informing the population about organizations engaged in waste management activities, distributing materials on the separate accumulation of solid municipal waste, informing about the correct handling of different waste types through the official website of the municipality, thematic stands, environmental actions, conversations, classroom hours in schools, conducting raids to identify unauthorized landfills, etc. These forms of interaction with local self-government bodies are necessary and are a condition for maintaining the urban life quality.

The second area of activity of local self-government bodies in the Russian Federation is determined by the so-called “powers of participation”. They are determined by articles 11, 20, 24 3, 24 9, 24 10, 24 11, 24 12, 25 of the federal law “On Production and Consumption Waste”, as well as the federal law “On the General Principles of the Organization of Local Self-Government in the Russian Federation” (for example, articles 14, 16). For example, local governments participate in the information support of activities in the field of waste management: they provide data to the regional inventory of waste, participate in the organization of activities for the accumulation (including separate), collection, transportation, processing, disposal, neutralization, and burial of municipal solid waste, and participate in the regulation of tariffs for waste management.

All over the world, local governments are actively involved in the waste, solid waste included, management system. This approach is due to the fact that for its effective functioning, it is important to take into account the specifics of a particular territory (the level of development of the city, the population number, the area of the city, the peculiarities of the internal organization of the city territory (for example, waste removal may be complicated in densely populated areas), and the types of waste and the volume of its generation). At the same time, with such active participation of local governments in the integrated waste management system, they may be prohibited from participating in the management of certain types of waste (for example, hazardous, radioactive, and medical), which is what is happening. In our opinion, this is fully justified. However, the effectiveness of the activities of local self-government bodies in the field of safe waste management is impossible without the participation of the local population, which must actively take part in the management system, as well as bear personal responsibility for noncompliance with waste management legislation.

Waste management, including municipal solid waste, is a serious problem in most developing countries. According to the World Bank, approximately 50% of urban waste from developing countries remains uncollected. In developing countries, one of the indicators of urban planning is the percentage of uncollected waste, and political barriers contribute to 75% of solid waste mismanagement (Loukil and Rouached 2020).

Waste management in developing countries is more challenging than in developed countries because landfills are the most common way to bury solid waste, as this is the cheapest option.

The difficulty in waste management in developed countries is that, as a rule, there are no reliable taxation regimes, tariffs, fees for services, as well as credit and debt servicing regimes to support the infrastructure. Developing countries generally do not have relatively high emission standards for financing. Thus, such countries largely depend on international donors and modest national support. As a rule, paper and cardboard wastes are incinerated before collection and disposal, and metal waste (iron, copper, aluminum, zinc, and lead) is collected for recycling. Some institutions, including cafes, restaurants, and sanatoriums, carefully collect food waste to turn it into compost or use it as animal feed. Others try to reuse and recycle everything that is possible, even if they improperly reuse bags of sugar, pesticides, and lime for storing food, feed, etc. (Ermolaeva 2017).

Lead recycling is also problematic in developing countries. In several large cities, young people collect discarded car batteries to extract lead from them. Lead is melted on kitchen stoves, poured into wooden molds, and sold for further processing. Unfortunately, when inhaled, lead vapors cause neurological stresses and diseases. A long-standing policy of the U.S. government has been to have U.S. embassies and foreign aid missions screen American workers for lead in their blood and/or hair and expel them from the affected countries for several weeks until their lead levels return to normal.

The analysis of global and national waste management programs based on socio-economic indicators allowed for the establishment that the standard of living affects the amount of waste generated (the higher it is, the more garbage masses are formed), and it is advisable to divide management practices according to different levels of life support. It was found that for countries with high, medium, and low income, the fractions of waste generation are different, since the lower the standard of living, the less waste that is difficult to recycle is generated. If the main problem for countries with a high standard of living is the amount of waste generated, then for countries with an average level it is the problem of organizing a management scheme with a sufficient volume of garbage masses suitable for recycling. Countries with a low standard of living are experiencing insufficient capacities for the production, disposal, and organization of waste within states, and are also the target of illegal imports of waste from more affluent countries.

The problem of waste in developing countries was described as a systemic problem back in 1972 in a report to the Club of Rome “The Limits to Growth”. Its authors, Donella Meadows, Dennis Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and William Behren, described the results of modeling the growth of the human population and the depletion of natural resources (Wilson et al. 2013). The work took into account such systemic and changing relative variables in developing countries as nonrenewable natural resources, industrial agricultural capital, farmland, capital of the service sector, free land, nonremovable pollutants (waste and chemical pollution), and population growth. The more the population grows, the more natural resources it needs to provide industrial capital, and the more waste is produced. However, the planet has a limit to the growth of the human population and the ability to absorb and/or recycle waste. There are several schemes that can be developed to control the system and to reduce it to control over one or more of its elements (population containment, search for new energy resources on renewable energy sources, energy efficiency, and resource intensity), but the problem of waste, as a byproduct of vital activity with the growth of any element, will remain.

One of the most important sources of solid waste is electronic waste. In developing countries, the problem of handling electronic waste (household appliances, computers, telephones, batteries, electronic parts used in transport, medical equipment, and security systems) and environmental pollution due to its accumulation is gaining momentum due to the lack of a legislative framework or government policy42. According to the Global Electronic Waste Monitoring Report (e-waste) for 2020, the production of electronic waste in 2019 amounted to about 53.6 Mt, of which 17.4% were properly collected and recycled, and the remaining 82.6% were not accounted for (Fathi et al. 2022). Every year, almost 50 Mt of electronic waste is generated in the world, and the contribution is higher in the developed countries of Europe, America, and Asia (based on the amount of electronic waste per capita). Asia currently produces a huge amount of e-waste, almost 24.9 Mt. However, taking into account the per capita consumption rate, Europe produces 16.2 kg per capita, America—13.3 kg per capita, and Asia—5.6 kg per capita. India and China are the largest consumers of electronic gadgets. China has enacted e-waste regulations with 14 types of e-waste classification. In addition, China has reduced WEEE imports in recent years. Globally, India is among the top five countries producing electronic waste. India has its own legislation on the handling of both solid and electronic waste, but it generates about 2.4 kg per capita. India is constantly updating rules and regulations for the proper management of e-waste for the benefit of the nation, as well as to raise public awareness about reducing pollution caused by e-waste (Rajesh et al. 2022). By 2030, global e-waste is predicted to reach 74.7 Mt (Rajesh et al. 2022). According to the forecast of the World Bank (Figure 3), by 2050 electronic waste will amount to 111.0 Mt. As we can see, in this case, a fairly optimistic forecast is considered (a uniform annual increase of 9.1% vs. 2000), with an exponential increase in the amount of e-waste and the world will drown in this waste.

Figure 3.

The amount of e-waste in the world: 1—empirical data43 (Kaza et al. 2018); 2—theoretical data with a uniform growth of 9.1% per year from the level of 2000.

According to the Solid Waste Management Rules of 2000, municipal authorities are solely responsible for monitoring and planning the development of infrastructure for the collection, storage, separation, transportation, processing, and disposal of solid waste. Solid household waste should be collected on a regular basis at preagreed dates and schedules in each house. The rules introduced the use of garbage cans of different colors depending on the category of waste. Thus, a green trash can is designed for biodegradable waste, a white trash can for recyclable waste, and a black trash can for other waste. Manual handling of solid waste is prohibited, but in unavoidable circumstances, the rules encourage the manual handling of waste with proper precautions by employees. Basically, the rules regulate the collection of waste and its primary storage. At the same time, special attention is paid to waste disposal methods, care of waste disposal sites after their closure for at least 15 years, and periodic medical examination of landfill workers. The location of landfills should be chosen away from such places as national parks, reservoirs, forests, and residential areas (Rajesh et al. 2022).

On 29 December 2018, the State Council of China released an ambitious urban program “Zero Waste”. Initial pilot projects were established for 11 cities and 5 regions (named “11 + 5”), covering Shenzhen, Baotou, Tongling, Weihai, Chongqing, Shaoxing, Sanya, Xuchang, Xuzhou, Panjin, and Xining, as well as Xiunan, Beijing Electronic City, Tianjin Eco-City, Guangjie, and Ruijin. By maximizing the reduction and recycling of waste, as well as minimizing landfills and environmental impacts, the philosophy of the program aims to promote a model of urban green development based on innovation, coordination, environmental friendliness, openness, and sharing (Zeng and Li 2021). In China, the main focus in the fight against domestic waste is on incinerators; by now about 50% of solid waste is incinerated.

Despite the measures taken, currently, the main method of handling municipal solid waste (MSW) in developing countries is storage and disposal. The same method is the main one for the disposal of electronic waste (China, India, Malaysia, and Pakistan), which leads to the contamination of soils and groundwater. At the same time, some countries, such as Malaysia, are striving to increase the volume of e-waste incineration with energy recovery, which is recognized as effective (Ismail and Hanafiah 2021).

In 2011, India adopted rules for the management of electronic waste, providing for extended producer responsibility. The manufacturer is obliged to establish a proper system for collecting electronic waste after the expiration of the service life of the equipment or the failure of the equipment before the expiration of its service life. The manufacturer must keep records of electronic waste with the provision of detailed information for the State Council for Pollution Control and raise consumer awareness about collection and return centers. The rules introduced a deposit system. When selling a new electronic product, consumers are charged an additional amount which is saved as a deposit. The amount deposited must be returned to the consumer with the appropriate interest after the expiration of the service life of a particular electronic product, provided that it is properly returned to authorized dealers. The collection target starts at 30% of the total volume of electronic waste and will increase by 10% every two years (Turaga et al. 2019). There are 312 state-authorized installations for dismantling (recycling) electronic waste in India. The state also implements preventive measures aimed at reducing the amount of electronic waste, for example, public service announcements in cinemas. The results of the activities are processed and taken into account44.