Abstract

This study investigates the thermodynamic and experimental aspects of producing a chromium–manganese ligature under high-temperature smelting conditions using low-grade iron–manganese ore and ferrosilicochrome (FeSiCr) dust as both a reducing agent and a chromium source. Thermodynamic modeling of the multicomponent Fe–Cr–Mn–Si–Al–Ca–Mg–O system was carried out using the HSC Chemistry 10 and FactSage 8.4 software packages to substantiate the temperature regime, reducing agent consumption, and conditions for the formation of a stable metal–slag system. The calculations indicated that efficient reduction of manganese oxides and formation of the metallic phase are achieved at a smelting temperature of 1600 °C with a reducing agent consumption of approximately 50 kg. Experimental smelting trials conducted in a laboratory Tammann furnace under the calculated parameters confirmed the validity of the thermodynamic predictions and demonstrated the feasibility of obtaining a concentrated chromium–manganese ligature. The resulting metallic product exhibited a high total content of alloying elements and had the following chemical composition (wt.%): Fe 35.41, Cr 41.10, Mn 8.15, and Si 4.31. SEM–EDS microstructural analysis revealed a uniform distribution of chromium and manganese within the metallic matrix, indicating stable reduction behavior and favorable melt crystallization conditions. The obtained results demonstrate the effectiveness of an integrated thermodynamic–experimental approach for producing chromium–manganese ligatures from low-grade mineral raw materials and industrial by-products and confirm the potential applicability of the proposed process for complex steel alloying.

1. Introduction

The increasing demands on the service performance of steels and the improvement of energy efficiency in metallurgical processes have led to growing interest in complex alloying technologies that enable the simultaneous introduction of multiple alloying elements into the molten metal [1,2,3,4,5]. Chromium and manganese are among the key alloying elements in modern steelmaking, as they significantly enhance the strength, hardenability, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance of steels [6,7,8,9].

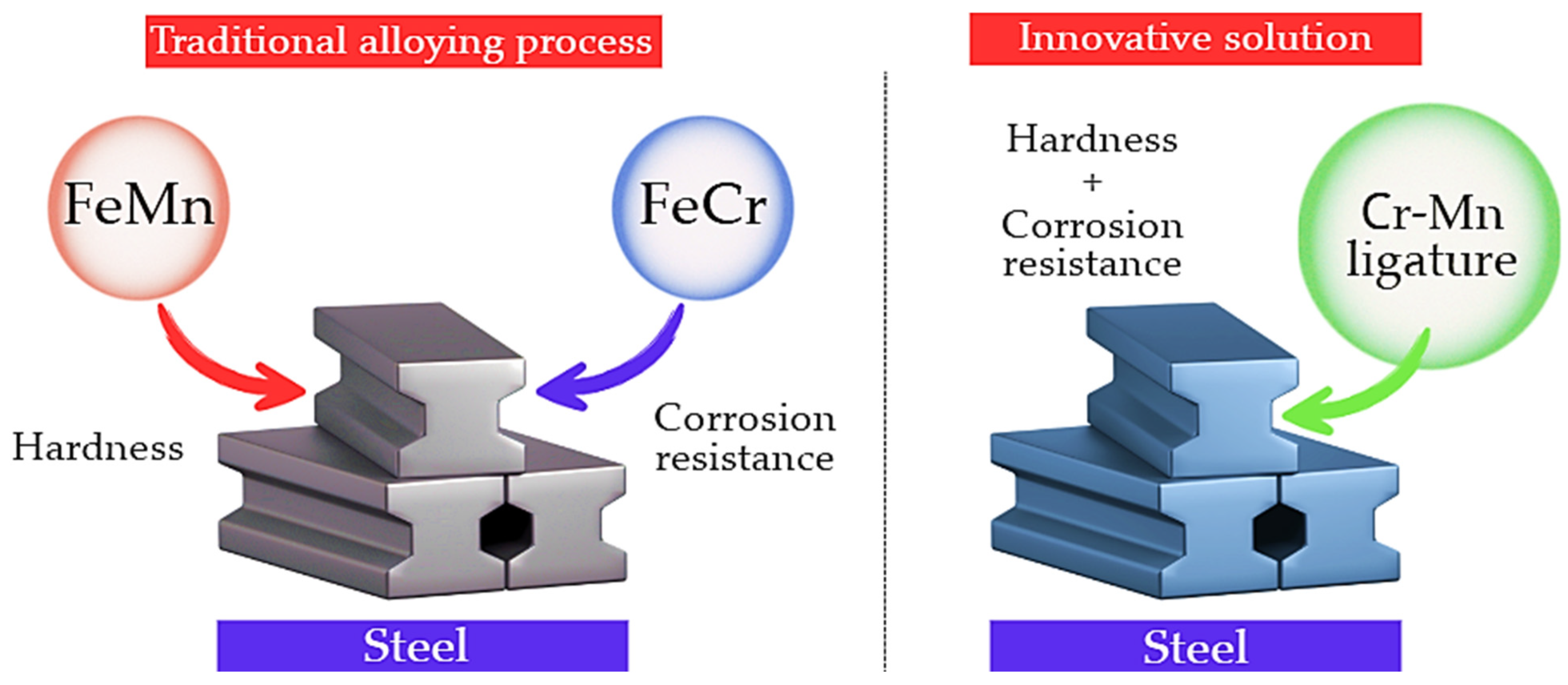

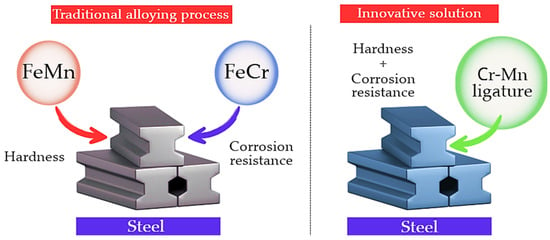

The conventional practice of separate addition of chromium and manganese in the form of individual ferroalloys complicates the alloying process, increases specific energy consumption, and is often accompanied by additional losses of alloying elements. In this context, the development and application of chromium–manganese ligatures are considered a promising approach for simplifying alloying operations and improving the stability and efficiency of metallurgical processes, as schematically illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the conventional alloying process and the innovative approach to complex Cr–Mn alloying.

Within this framework, the development of chromium–manganese ligatures is closely linked to broader challenges of resource efficiency and sustainability in ferroalloy production, particularly in relation to the behavior of multicomponent metal–slag systems and the utilization of complex raw materials.

In the context of sustainable metallurgical development, considerable attention is devoted to technologies enabling the comprehensive recovery of valuable components from multicomponent raw materials and technogenic wastes, including those arising during the production of chromium- and manganese-containing ferroalloys. Based on thermodynamic modeling combined with experimental verification, several studies [10,11] have examined in detail the behavior of CaO–SiO2–MgO–Al2O3 oxide systems forming the slag phase in high-temperature reduction processes, providing a scientific basis for optimizing Cr and Mn reduction conditions. A number of works [12,13] emphasize the effectiveness of metallothermic approaches and precise control of slag basicity in enhancing alloying element recovery, improving alloy purity, and reducing specific energy consumption. Furthermore, investigations of carbothermic interaction mechanisms in similar systems [14] highlight the importance of diffusion processes and phase transformations within the melt and at the metal–slag interface. The application of these approaches opens prospects for involving low-grade ores and technogenic materials in metallurgical processing; however, it requires careful consideration of physicochemical factors governing the stability of reduction reactions.

Despite the evident advantages of complex alloying, the production of chromium–manganese ligature is associated with a number of significant physicochemical challenges. Chromium and manganese exhibit a high affinity for oxygen and a strong tendency to form thermodynamically stable oxide compounds [15,16,17], which considerably complicates their simultaneous reduction under high-temperature smelting conditions. The efficiency of Cr and Mn transfer into the metallic phase is largely governed by the state of the slag system, including its phase composition, thermodynamic stability, and rheological properties. Slag viscosity, phase state, and the ability to ensure effective metal–slag separation play a decisive role in the completeness of reduction reactions and the overall stability of the metallurgical process [18,19,20,21,22,23].

In previously published works by the authors addressing resource-efficient smelting technologies for chromium-containing ferroalloys and multicomponent metal–slag systems [24,25,26], it has been shown that studies in this field are generally limited either to thermodynamic evaluations of equilibrium system behavior or isolated experimental investigations.

Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of producing chromium–manganese ligatures using silicon–aluminum reducing agents, such as aluminosilicomanganese and ferrosilicoaluminum alloys [27]. The application of these reducing systems provided high recovery levels of the main alloying elements, exceeding 80%, which indicates favorable thermodynamic conditions and a high degree of completion of reduction reactions. In contrast, when conventional ferroalloys, including ferrochrome and ferromanganese, are employed, the recovery of chromium and manganese typically remains within the range of 67–73% [11,28,29,30]. This limitation is primarily associated with metal losses to the slag phase and the restricted efficiency of the reduction processes. These differences highlight the significant influence of the nature of the reducing agent on the kinetics and depth of alloying element reduction.

The relevance of the present study is further enhanced by the increasing necessity to involve low-grade chromium- and manganese-bearing ores in metallurgical processing, the proportion of which in the raw material base continues to grow. Processing such ores using conventional technologies is associated with increased energy consumption and a deterioration of technical and economic performance. At the same time, interest in the rational utilization of technogenic materials and by-products of ferroalloy production is steadily increasing. In particular, during FeSiCr crushing, a fine-grained fraction (FeSiCr dust) is generated, which possesses considerable reducing potential but often remains underutilized [31]. The systematic formation of this material at enterprises such as the Aksu Ferroalloy Plant makes its application in metallurgical processes both technically feasible and economically justified.

The scientific novelty of the present work lies in the comprehensive substantiation and experimental implementation of an approach for producing chromium–manganese ligatures under high-temperature smelting conditions using low-grade mineral raw materials and an accessible silicon-containing reducing agent in the form of FeSiCr dust. In contrast to previous studies focused on silicon–aluminum reducing systems, this work proposes and implements the use of FeSiCr dust as an industrial by-product, accompanied by a simultaneous assessment of its influence on process thermodynamics, slag phase composition, and rheological properties.

The study combines thermodynamic modeling of slag phase composition and viscosity using specialized software packages with experimental smelting trials conducted in a Tammann furnace. The obtained products were examined by scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive spectroscopy, which enabled the establishment of relationships between thermodynamic prerequisites, slag characteristics, and the actual recovery behavior of chromium and manganese. As a result, the work develops a scientifically grounded approach to chromium–manganese ligature production that integrates the processing of low-grade raw materials, the utilization of industrial by-products, and the optimization of high-temperature reduction processes.

From an industrial standpoint, the proposed approach provides a realistic opportunity to incorporate low-grade iron–manganese ores and FeSiCr dust into existing ferroalloy production routes. The use of FeSiCr dust, which is commonly accumulated or inefficiently utilized, allows it to be regarded as a valuable secondary resource, contributing to waste reduction and improved raw material efficiency. Moreover, the production of a chromium–manganese ligature simplifies alloying operations in steelmaking, creating the potential for lower energy demand and reduced alloying losses. In this way, the developed process is consistent with current trends in sustainable metallurgy and the principles of the circular economy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

As raw materials for the production of the chromium–manganese ligature, a low-grade iron–manganese ore from the Kerege–Tas deposit and industrially generated FeSiCr dust were used. The selection of these materials was motivated by the focus of the study on the processing of low-grade mineral resources and secondary metallurgical materials that are readily available for practical application.

The low-grade iron–manganese ore from the Kerege–Tas deposit is characterized by a reduced manganese content and the presence of associated oxides of iron, silicon, aluminum, and magnesium, which significantly complicates its utilization in conventional ferroalloy production technologies. The chemical composition of the ore is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the low-grade Kerege–Tas iron–manganese ore (wt.%).

FeSiCr dust, generated during the crushing of FeSiCr at the Aksu Ferroalloy Plant (Kazakhstan), was used as the reducing agent. This material is characterized by a high silicon content and the presence of residual chromium, which provides a pronounced reducing potential under high-temperature processing conditions. The chemical composition of the FeSiCr dust is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of FeSiCr dust used as a reducing agent (wt.%).

The chemical composition of the raw materials used in this study was determined using wet chemical analysis methods. The obtained analytical data were subsequently employed for mass balance calculations, thermodynamic modeling, and interpretation of the experimental smelting results.

2.2. Thermodynamic Modeling

Thermodynamic modeling was performed to substantiate the key parameters of the chromium–manganese ligature production process and to preliminarily assess the conditions of high-temperature smelting within the multicomponent Fe–Cr–Mn–Si–Al–Ca–Mg–O system. The study included calculations characterizing the equilibrium state of the metal–slag system and aimed to determine the smelting temperature, reducing agent consumption, and the optimal ratio of slag-forming components.

The initial thermodynamic assessment was carried out using the HSC Chemistry 10 software package [32]. The Equilibrium module was employed to determine the equilibrium phase composition of the Fe–Cr–Mn–Si–Al–Ca–Mg–O system at specified temperature and pressure conditions. Based on the modeling results, the feasibility of chromium and manganese oxide reduction, their tendency to transfer into the metallic phase, and the thermodynamic viability of the process were evaluated. The obtained data were used to justify the temperature range of smelting and the required consumption of reducing agent.

To enable targeted control of the slag phase composition and to evaluate its technological properties, subsequent calculations were performed using the FactSage 8.4 software package. Thermodynamic modeling was conducted for a multicomponent system involving the main slag-forming oxides, which made it possible to identify the regions of slag phase stability. The CaO addition was selected through calculation in order to optimize the slag composition and establish favorable thermodynamic conditions within the metal–slag system.

The rheological properties of the slags were evaluated using the FactSage Viscosity module. As a result of the calculations, the dependence of slag viscosity on temperature and chemical composition was established, and slag compositions ensuring effective separation of the metallic and slag phases were identified. Viscosity values were considered one of the key criteria in assessing the technological stability of the smelting process and in selecting optimal slag compositions for experimental investigations.

Thus, the results of thermodynamic modeling of the Fe–Cr–Mn–Si–Al–Ca–Mg–O system made it possible to substantiate the smelting temperature and reducing agent and lime consumption, as well as to purposefully control the phase and rheological properties of the slag system. The obtained calculated data were used as a scientific basis for planning and interpreting the experimental smelting trials conducted in the Tammann furnace.

2.3. Experimental Smelting

Experimental smelting trials were conducted to practically verify the results of thermodynamic modeling and evaluate the conditions for producing a chromium–manganese ligature under real high-temperature conditions. The smelting experiments were carried out in a laboratory Tammann furnace, which provides a stable and well-controlled temperature regime and is widely used for investigations of metal–slag systems. The temperature inside the furnace was monitored using a WRe-type thermocouple positioned in close proximity to the crucible, ensuring reliable control of the thermal regime during the smelting experiments.

The charge for the experimental smelting trials was prepared based on low-grade iron–manganese ore from the Kerege–Tas deposit and FeSiCr dust used as the reducing agent. The quantitative ratio of the components, as well as the consumption of the reducing agent and lime, was determined according to the results of thermodynamic modeling of the Fe–Cr–Mn–Si–Al–Ca–Mg–O system using the HSC Chemistry 10 and FactSage software packages.

Considering the laboratory-scale crucible smelting, the manganese ore was preliminarily crushed to particle sizes below 5 mm. FeSiCr dust and lime were used in a fine-grained state. The crucible was covered with a lid to ensure stable processing conditions and reduce material losses.

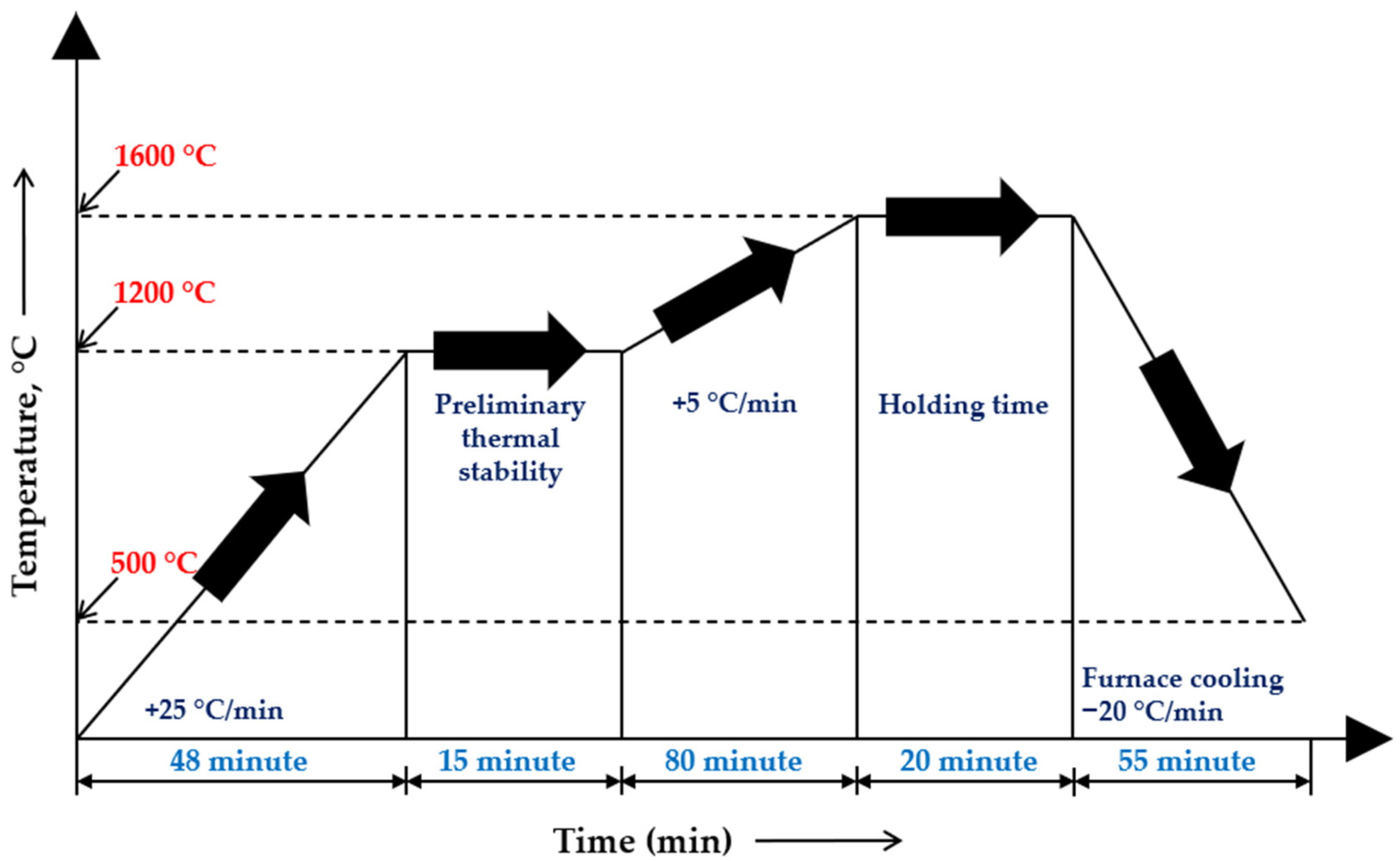

The smelting temperature was selected in accordance with the thermodynamic modeling results, and the experiments were conducted at a maximum temperature of 1600 °C. After reaching this temperature, an isothermal holding period of 20 min was applied to ensure the completion of chromium and manganese oxide reduction and the establishment of equilibrium between the metallic and slag phases.

Upon completion of smelting, the crucible was cooled inside the furnace down to approximately 500 °C under controlled furnace-cooling conditions, after which it was removed from the furnace and allowed to cool to ambient temperature. The smelting products were then mechanically separated to isolate the metallic and slag phases and subsequently used for phase and microstructural analyses, as well as for evaluating the degree of chromium and manganese transfer into the metallic phase.

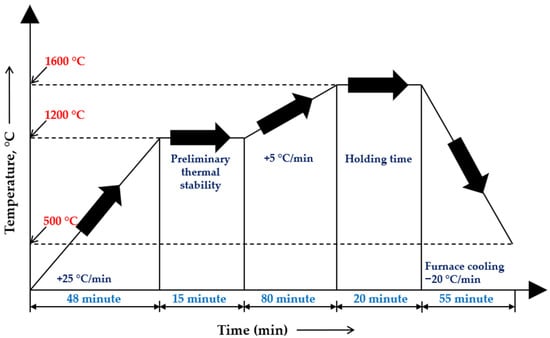

The experimental heating, melting, and furnace-cooling stages followed the temperature–time profile illustrated in Figure 2. The experimental results were compared with the thermodynamic modeling data to assess the influence of the temperature regime and slag system properties on the efficiency of the reduction reactions.

Figure 2.

Temperature–time profile of the high-temperature smelting experiment.

2.4. Microstructural and Phase Characterization

Microstructural analysis and investigation of the distribution of alloying elements in the metallic phase were carried out using scanning electron microscopy combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM–EDS) with a ZEM20 benchtop scanning electron microscope manufactured by ZEPTOOLS Technology (Tongling, Anhui Province, China). This instrument provides high spatial resolution imaging and enables localized elemental analysis of the metallic matrix, which is particularly important for evaluating the distribution of chromium and manganese in the obtained chromium–manganese ligature.

The microstructural characterization of the samples was carried out on metallographically prepared polished sections using secondary electron (SE) and backscattered electron (BSE) imaging modes, which provide contrast based on surface morphology and the average atomic number of the phases. Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was employed for local phase identification and for assessing the elemental distribution within the metallic and slag phases.

The phase composition of the obtained products was investigated by X-ray diffraction using a PANalytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands). Phase identification was performed by comparing the experimental diffraction patterns with the PDF-4 database of the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermodynamic Assessment

The thermodynamic results obtained in the present study were aimed at evaluating the influence of the temperature regime and FeSiCr dust consumption on the conditions of metallic phase formation during chromium–manganese ligature production. Thermodynamic calculations were performed using HSC Chemistry 10 software. The calculations were performed over a wide temperature range of 1400–1800 °C, which made it possible to trace the general trends of the reduction processes and to identify the region of thermodynamically favorable smelting conditions. Particular attention was paid to the role of the reducing agent consumption, as its amount directly determines the degree of manganese reduction, the composition of the metallic phase, and the stability of the metal–slag system.

In the metallic phase, the formation of both a metallic matrix containing Cr, Fe, Mn, and Si and a series of chromium, iron, and manganese silicide compounds was established, including CrSi, CrSi2, Cr3Si, Cr5Si3, FeSi, Fe3Si, Fe5Si3, MnSi, Mn3Si, and Mn5Si3. The presence of these phases indicates a deep progression of reduction and alloying reactions and reflects the high chemical activity of silicon in the investigated system.

Analysis of the slag phase showed that it represents a complex oxide assemblage predominantly belonging to the CaO–Al2O3–SiO2 system, with the formation of characteristic mineralogical phases. The slag is mainly composed of calcium aluminosilicates (CaAl12O19, CaAl2Si2O8, and CaSiO3) and manganese-bearing silicates (MnSiO3, Mn2SiO4), as well as simple oxides and spinel-type compounds (Al2O3, Cr2O3, MnO, SiO2, and MnO·Al2O3).

The diversity of oxide and silicate compounds in the slag phase indicates the establishment of a complex phase equilibrium within the metal–slag system. The ratio of basic and acidic oxides plays a decisive role in determining melt structure, slag physicochemical properties, and the distribution behavior of elements between phases, thereby confirming the active role of the slag in the metallurgical process.

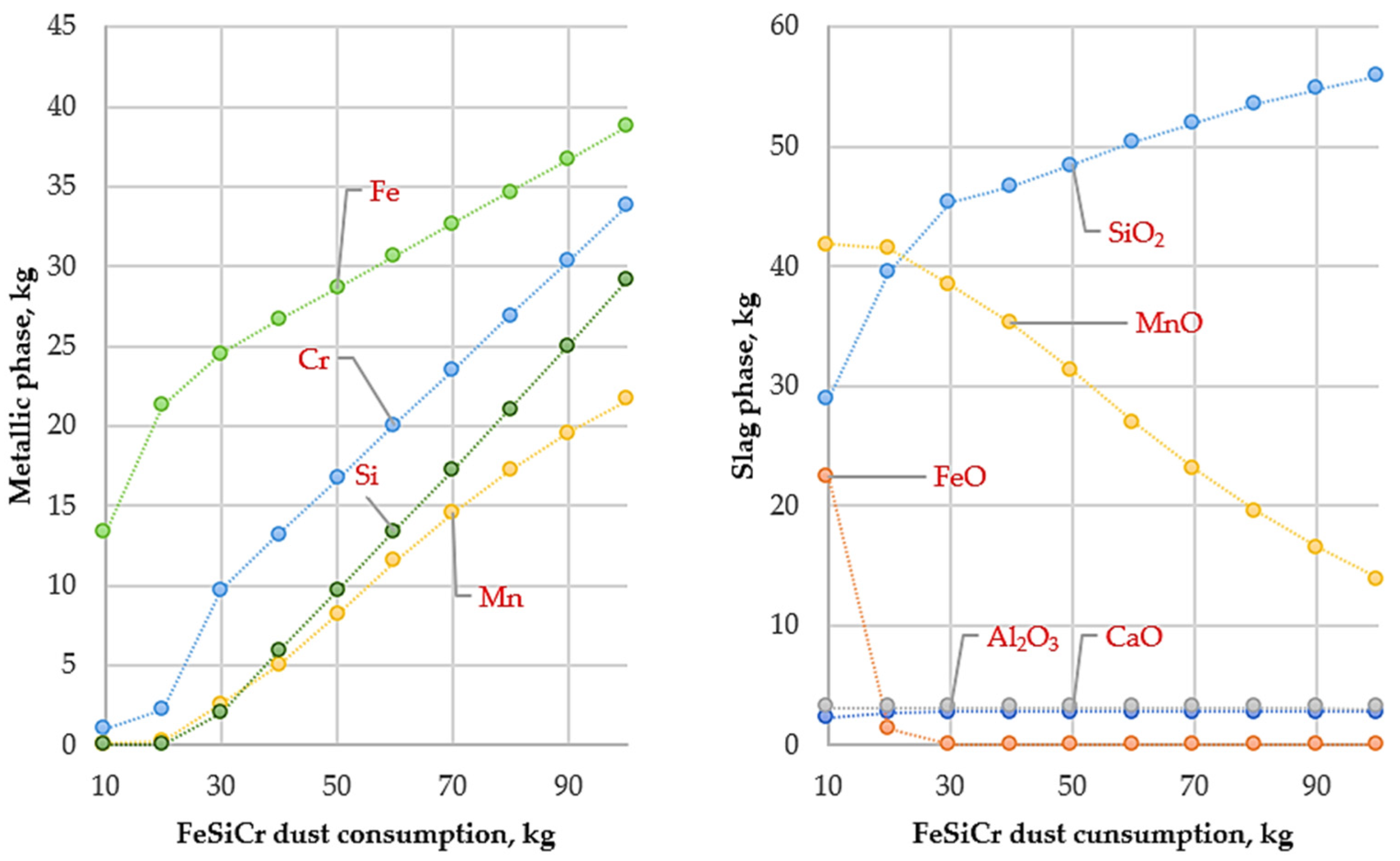

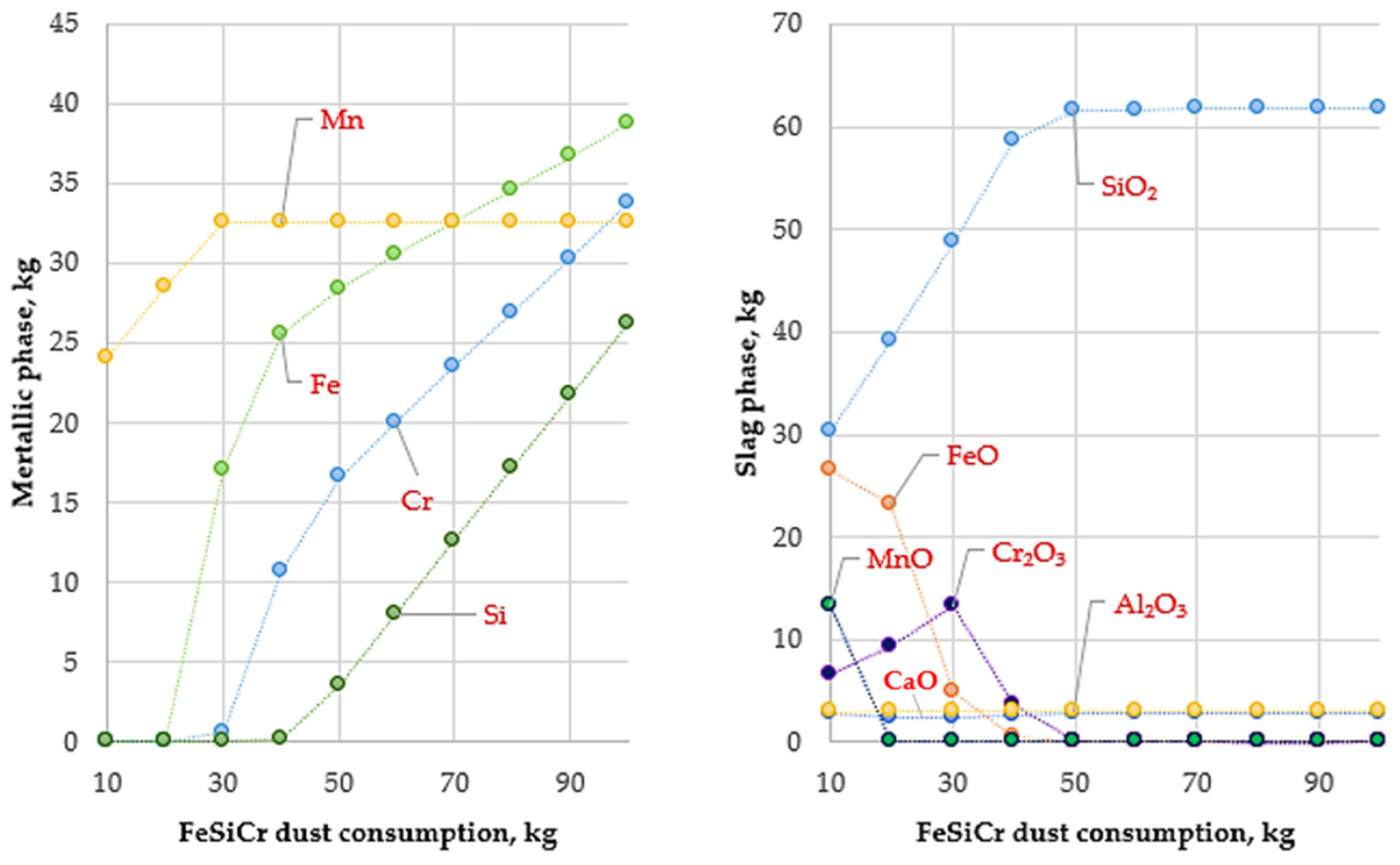

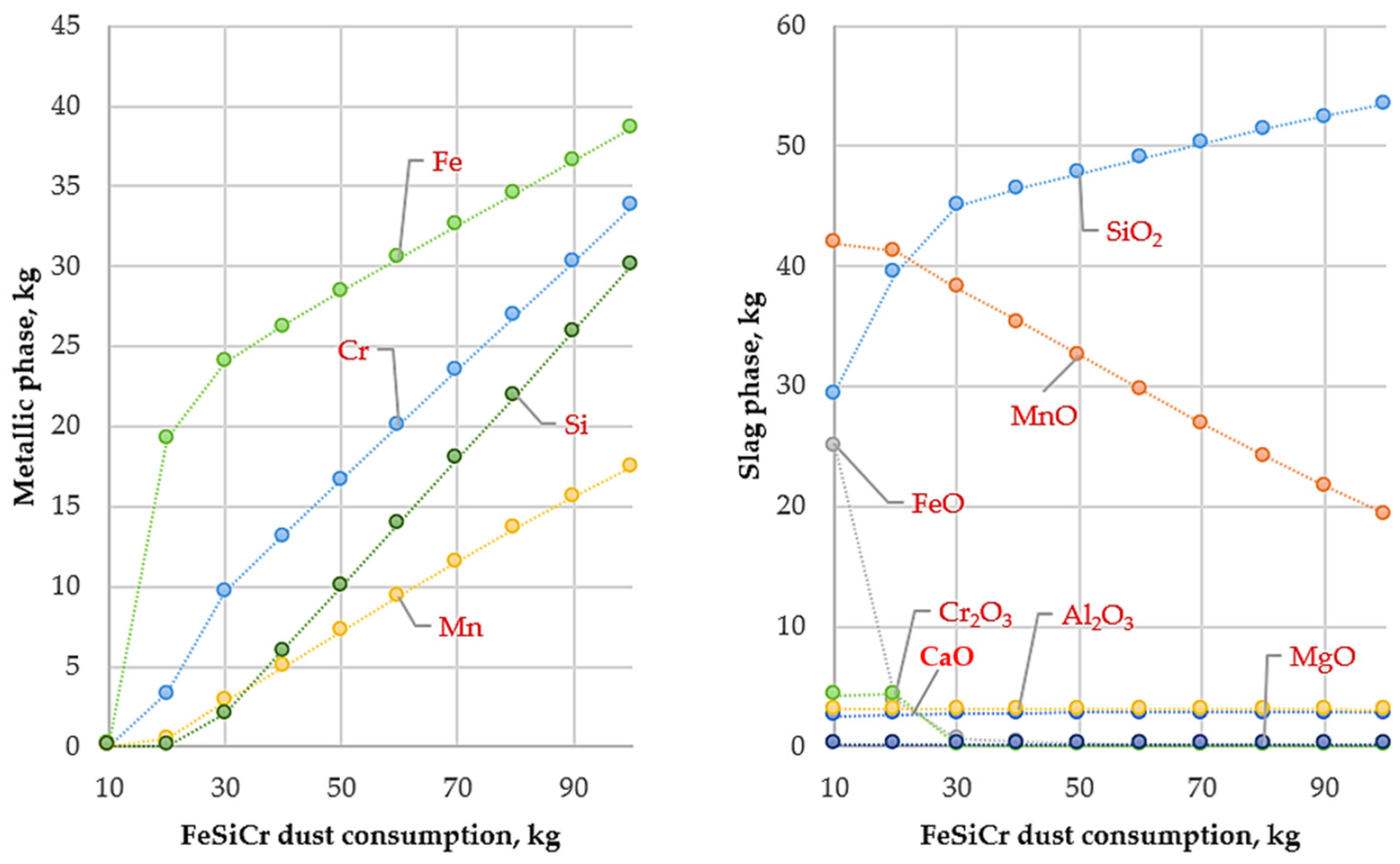

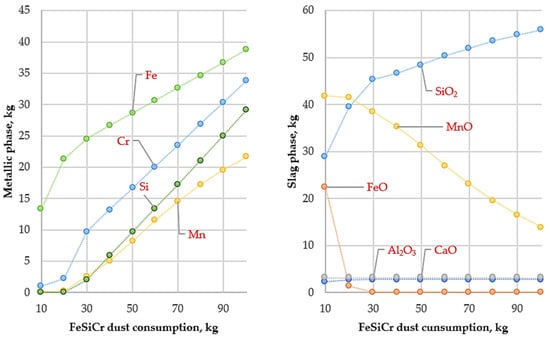

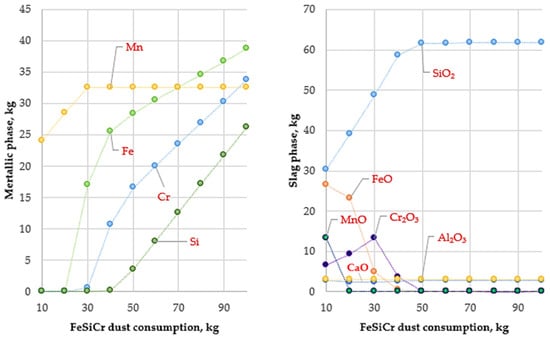

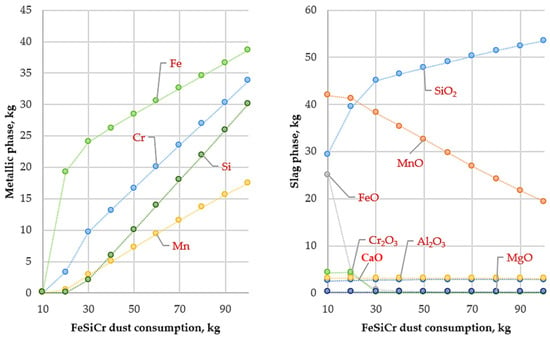

The results of thermodynamic calculations illustrating the influence of temperature and FeSiCr dust consumption on smelting conditions are presented in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 3.

Variation in metallic and slag phase masses with FeSiCr dust consumption (10–100 kg) at 1400 °C.

Figure 4.

Variation in metallic and slag phase masses with FeSiCr dust consumption (10–100 kg) at 1600 °C.

Figure 5.

Variation in metallic and slag phase masses with FeSiCr dust consumption (10–100 kg) at 1800 °C.

The results of thermodynamic modeling performed at 1400 °C (Figure 3) show that the depth of reduction reactions is governed by the thermodynamic stability of metal oxides and the chemical nature of the applied reducing agent. Under these conditions, the reduction behavior of iron and manganese oxides differs significantly.

Iron oxides at 1400 °C are thermodynamically less stable compounds. According to Ellingham diagrams, the reduction reactions of iron oxides by silicon are characterized by negative Gibbs free energy values (ΔG), which ensures an almost complete reduction of iron to the metallic state and is accompanied by a steady increase in its content in the metallic phase.

In contrast, manganese oxide (MnO) exhibits considerably higher thermodynamic stability. At 1400 °C, the affinity of silicon for oxygen is insufficient to fully break the Mn–O bond; consequently, the ΔG values of MnO reduction reactions do not shift into a distinctly negative region. As a result, manganese is only partially reduced and is predominantly retained in the slag phase in the form of MnO, which is consistent with the calculated slag composition.

Under these conditions, silicon introduced with FeSiCr dust, after actively interacting with iron oxides, does not possess sufficient thermodynamic driving force to further reduce manganese and therefore accumulates in the metallic phase. This leads to silicon enrichment of the metal, while a significant fraction of manganese remains in the slag.

Thus, the modeling results at 1400 °C indicate a high efficiency of iron reduction when using FeSiCr dust, whereas deep reduction of manganese by silicon is thermodynamically limited. To increase the degree of manganese transfer into the metallic phase, an increase in smelting temperature is required to shift the Gibbs free energy of MnO reduction reactions into the negative region.

At this temperature, the reduction of manganese oxides is significantly intensified, resulting in an almost complete transfer of manganese into the metallic phase (Figure 4). This indicates that 1600 °C provides sufficient thermodynamic potential to overcome the high stability of MnO and to achieve its complete reduction by silicon contained in the FeSiCr dust. Simultaneously, the reduction of iron and chromium oxides proceeds steadily, ensuring a high degree of their transfer into the metallic phase.

Analysis of element recovery confirms the key role of temperature, particularly with respect to manganese. Compared with 1400 °C, where the manganese recovery was approximately 66%, an increase in temperature to 1600 °C raises this value to 99.97%. At the same time, the recovery of iron and chromium remains at a high level, reaching 99.94% and 98.76%, respectively.

The high efficiency of the reduction process is further confirmed by the composition of the slag phase. At an optimal reducing agent consumption (above 30 kg, conditional units), the slag is almost completely depleted of valuable metal oxides. The reduction of MnO content in the slag to near-zero values provides direct evidence of the complete transfer of manganese into the metallic phase. As a result, the final slag represents a stable oxide system predominantly composed of SiO2, Al2O3, and CaO. Analysis of the metallic phase shows that the obtained ligature is characterized by a complex chemical composition with the presence of silicide phases such as FeSi, CrSi, MnSi, Cr5Si3, and Fe5Si3.

The study also established the optimal consumption of the reducing agent. The calculations showed that an optimal amount of FeSiCr dust was approximately 50 kg, at which the recovery of the main metals reached its maximum values (97–99%). Further increases in reducing agent consumption did not result in a significant improvement in metal recovery but led to excessive silicon accumulation in the metallic phase. Thus, a FeSiCr dust consumption of 50 kg provided an optimal balance between a high recovery of valuable components and a balanced chemical composition of the final product.

Overall, increasing the smelting temperature to 1600 °C is a key condition for the production of Cr–Mn ligatures using FeSiCr dust. This temperature regime, combined with the optimal reducing agent consumption (50 kg), ensures the nearly complete recovery of manganese, iron, and chromium from the initial raw materials and creates favorable prerequisites for achieving high technological and economic efficiency of the process.

Within the framework of the study, the effect of further increasing the temperature above the optimal level of 1600 °C up to 1800 °C on the main technological indicators of the process was analyzed (Figure 5). The purpose of this modeling stage was to assess potential negative effects associated with excessively high temperatures and to determine the upper limit of the optimal technological window.

The modeling results demonstrated that increasing the temperature beyond the optimal value does not improve process efficiency but, on the contrary, leads to its deterioration. According to the mass balance calculations, the mass of the produced metal decreases to 119.95 kg, while the mass of the slag phase increases to 78.83 kg, indicating a reduction in the overall yield of the target product.

The key issue at 1800 °C is a sharp decrease in the degree of manganese transfer into the metallic phase. At 1600 °C, the manganese recovery exceeded 99.9%, whereas at 1800 °C, its maximum value decreased to 53.61%, which is even lower than that obtained at 1400 °C. This phenomenon is attributed, first, to a significant increase in the saturated vapor pressure of metallic manganese at high temperature, resulting in its intensive evaporation and transfer into the gas phase, and second, to the retention of a considerable amount of unreduced manganese oxide in the slag (up to 19.37 kg). Thus, the total manganese losses arise from both its evaporation and its retention in the slag phase.

An increase in temperature also negatively affects silicon distribution. The degree of silicon transfer into the metallic phase rises to 54.46%, leading to excessive silicon accumulation in the final alloy and deterioration of its chemical composition. Although the recovery of iron and chromium at 1800 °C remains high (above 98%), the substantial losses of manganese fully negate any potential advantages of this temperature regime.

Thus, increasing the smelting temperature to 1800 °C is technologically and economically unjustified. Excessively high temperatures result in intensive manganese evaporation, its retention in the slag, increased silicon content in the metallic phase, and consequently, a reduction in overall process efficiency. The obtained results confirm that 1600 °C represents the upper boundary of the optimal technological window for producing Cr–Mn ligatures using FeSiCr dust.

As a result of the conducted thermodynamic analysis using the HSC Chemistry 10 software package, effective technological conditions for producing Cr–Mn ligatures with FeSiCr dust as the reducing agent were established. According to the calculated data, the optimal smelting temperature is 1600 °C, and the rational reducing agent consumption is 50 kg (conditional units). Under these process parameters, the maximum recovery of the main metals into the metallic phase and the formation of a stable slag system are achieved. The calculated chemical compositions of the metallic and slag phases corresponding to these conditions are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Calculated composition of the metallic and slag phases at the optimal smelting conditions (1600 °C, 50 kg of FeSiCr dust).

In addition to achieving a high degree of metal recovery, the regulation of the physicochemical properties of the slag—such as viscosity, melting temperature, and basicity—is of critical importance for ensuring the stability of the metallurgical process and its industrial efficiency. Under the optimal regime, the initial slag is characterized by an increased content of silicon dioxide, indicating a high level of acidity. Acidic slags generally exhibit elevated viscosity and sluggish melting behavior, which can hinder effective metal–slag separation and lead to technological complications.

To adjust the properties of the slag phase under the thermodynamically optimal operating conditions, an additional thermodynamic assessment was carried out. Using the FactSage 8.4 software package, the initially formed acidic slag was modified by adding various amounts of CaO (from 10 to 150 kg, with a step of 10 kg) in order to regulate slag basicity and viscosity. The influence of CaO addition on the chemical composition and basicity of the slag was investigated.

The modeling results illustrating changes in the normalized slag composition (wt.%) and basicity level as a function of CaO addition are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effect of CaO addition (10–150 kg, step 10 kg) to the initially formed acidic slag on its chemical composition (wt.%) and basicity under the selected thermodynamic conditions.

The data presented in Table 4 indicate that an increase in lime consumption has a decisive effect on the composition and basicity of the slag phase. In the absence of CaO addition, the slag is characterized by a high SiO2 content and a low basicity index (B3 ≈ 0.05), corresponding to an acidic melt. As the CaO addition increases to approximately 50 kg, the proportion of calcium-containing components rises, and a gradual decrease in slag acidity is observed, accompanied by an increase in B3 to values close to 0.8. Further lime addition shifts the system into the region of stable basic slags: at CaO consumptions of 80–100 kg, the basicity index exceeds 1.3–1.5, while at maximum lime additions (130–150 kg), a highly basic slag is formed with B3 > 2. This behavior indicates effective neutralization of acidic components and demonstrates the feasibility of targeted slag regime control through lime additions.

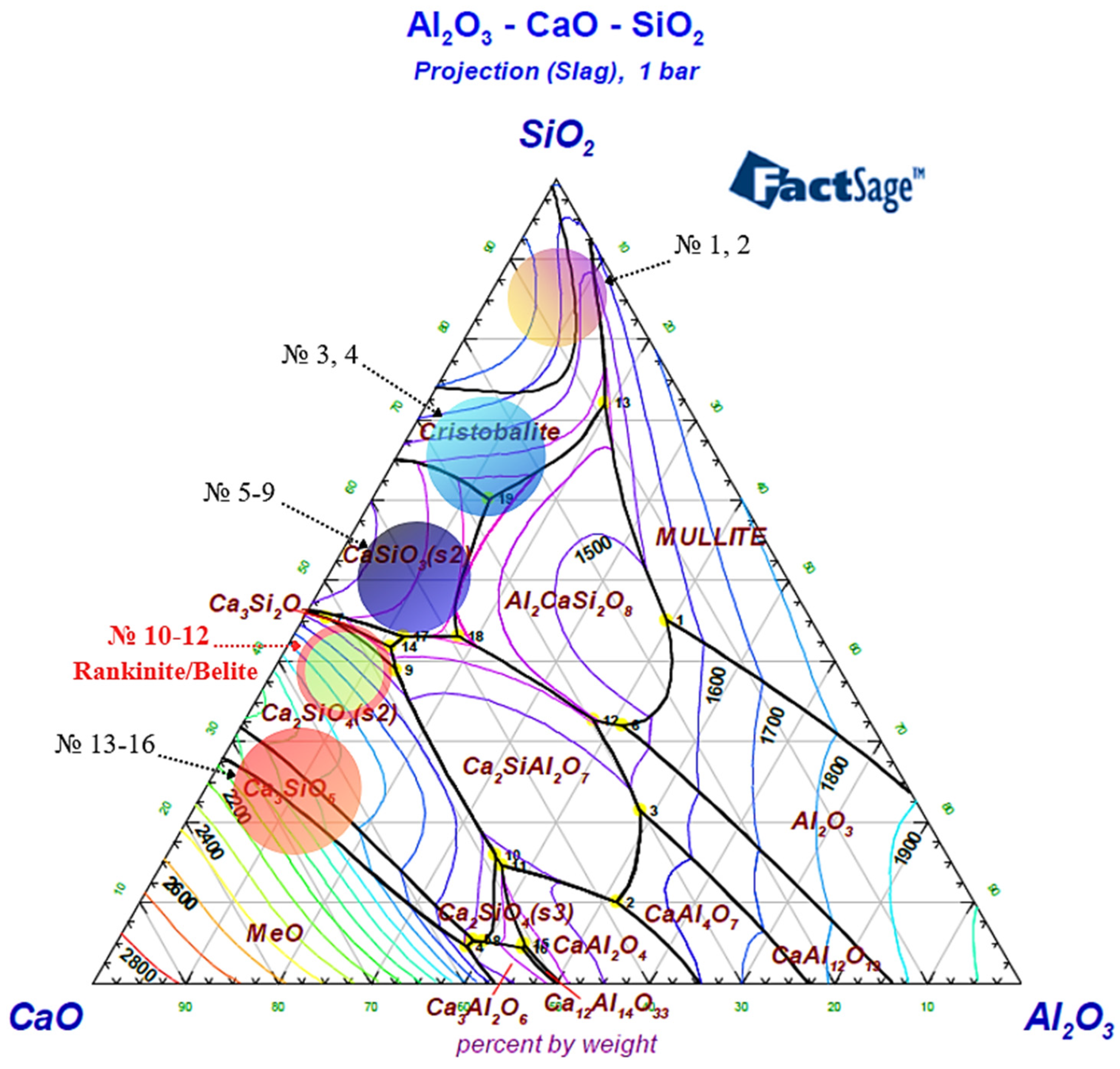

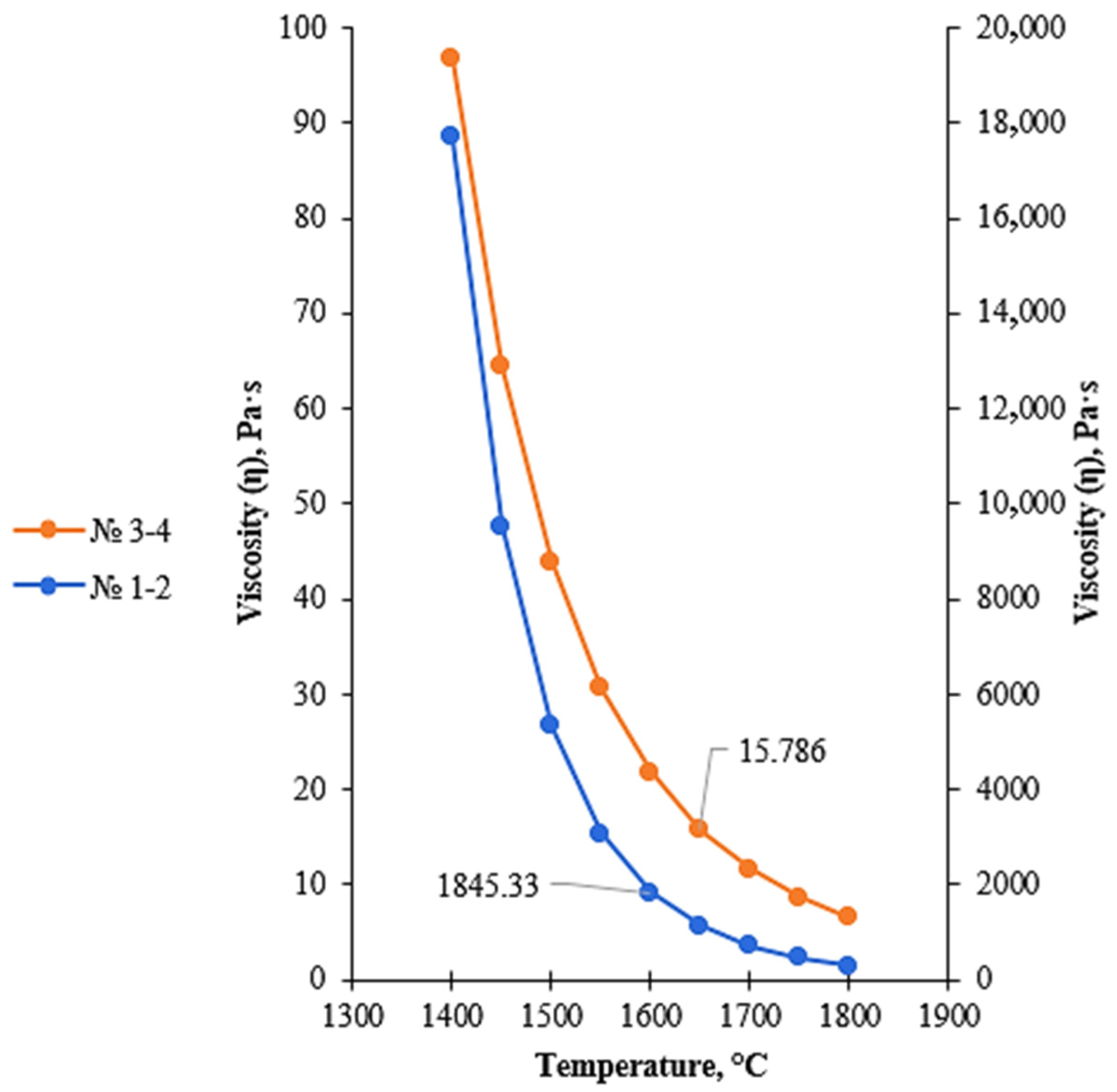

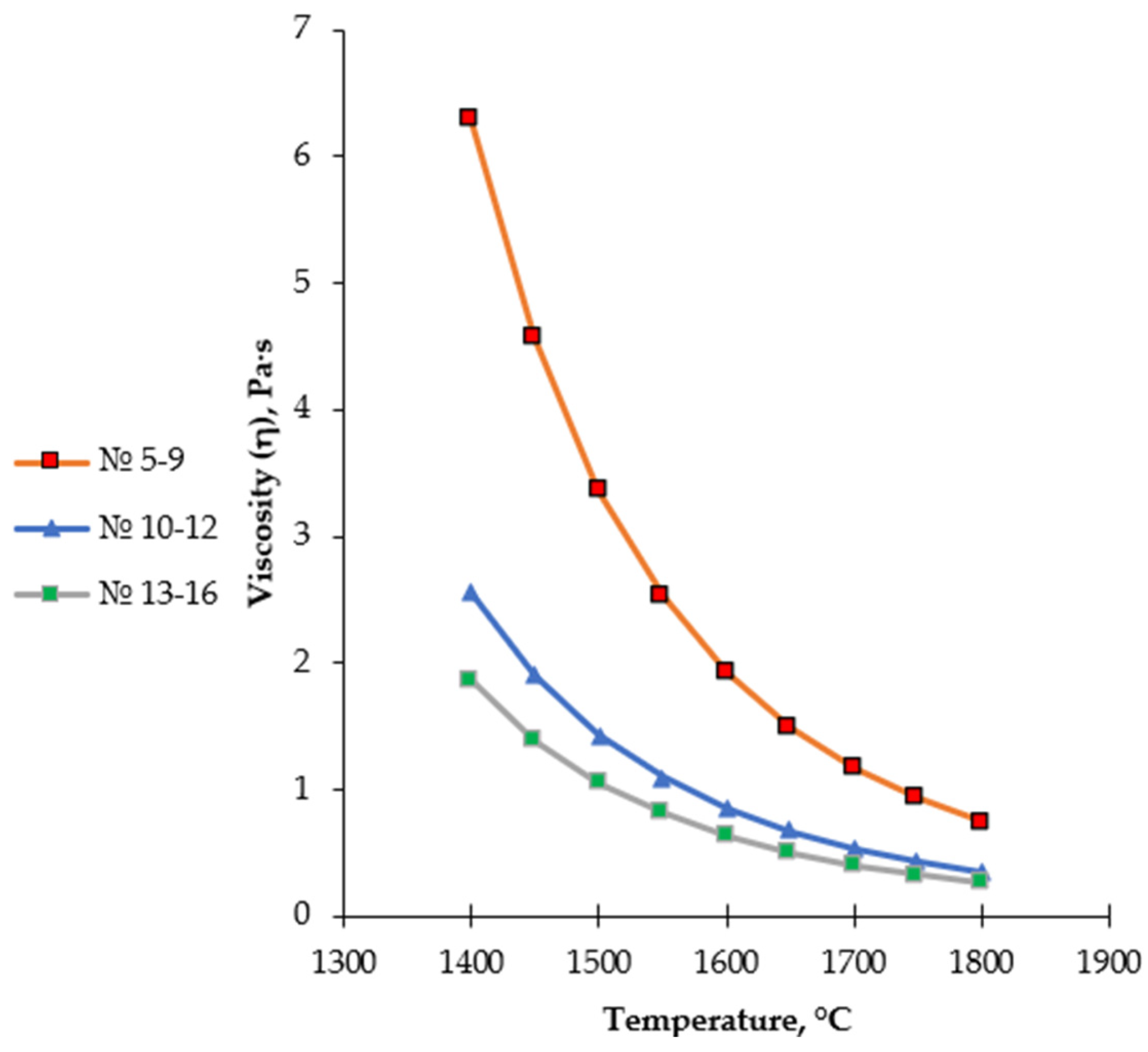

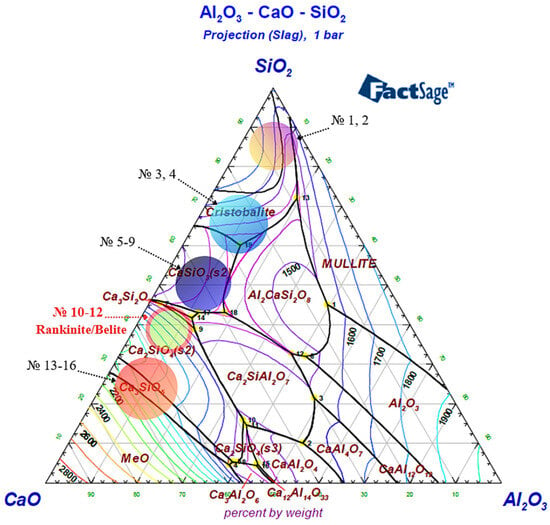

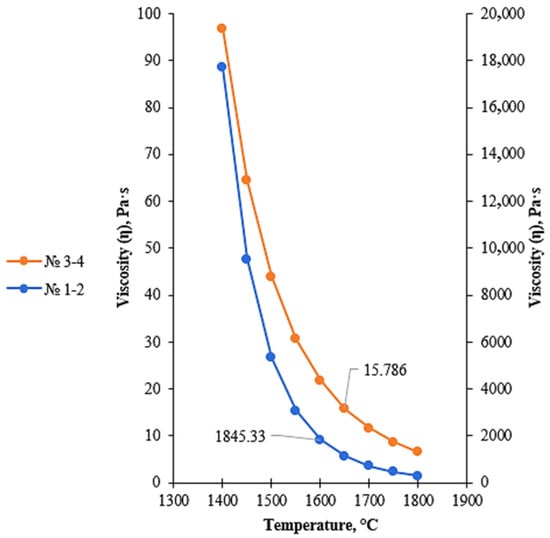

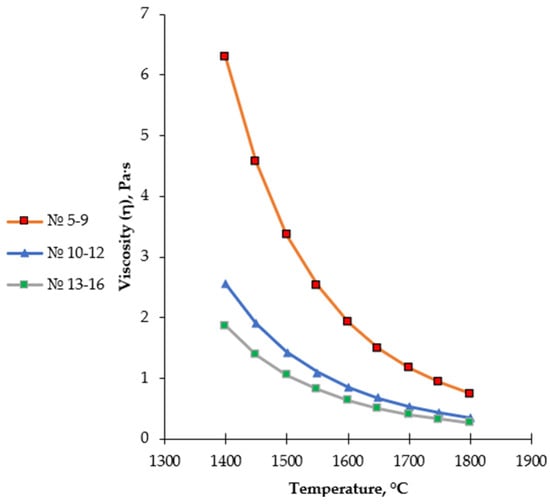

To optimize the slag regime during the production of the complex Cr–Mn ligature, a phase analysis of the Al2O3–CaO–SiO2 system was carried out based on the corresponding phase diagram. To assess the effect of lime consumption on the liquidus temperature and slag phase composition, the investigated compositions were grouped into several characteristic regions, as shown in Figure 6. In addition, the viscosity of the identified slag regions was analyzed in detail over a wide temperature range (Figure 7 and Figure 8; Table 5 and Table 6).

Figure 6.

Three-component phase diagram of the Al2O3–CaO–SiO2 system, generated using FactSage 8.4.

Figure 7.

Temperature dependence of viscosity of low-basicity acidic slags (regions 1–4), calculated using the FactSage 8.4 Viscosity module.

Figure 8.

Temperature dependence of the viscosity of medium- and high-basicity slags (Regions 5–16), calculated using the FactSage 8.4 Viscosity module.

Table 5.

Calculated parameters of temperature dependence (Zones 1–4).

Table 6.

Calculated parameters of temperature dependence (Zones 5–16).

Regions 1–2 correspond to silica-rich slags with extremely low basicity and are located near the SiO2 apex of the Al2O3–CaO–SiO2 phase diagram. These regions are characterized by a high silica content, which results in a highly polymerized silicate melt structure. The spatially extended network of [SiO4] tetrahedra leads to a sharp increase in viscosity and a reduction in slag fluidity, thereby hindering the movement of metallic droplets and impairing effective metal–slag separation.

Regions 3–4 correspond to the thermodynamic stability field of the cristobalite phase. For these compositions, SiO2 dominates the slag, promoting the formation of its high-temperature crystalline modifications. The presence of cristobalite increases the structural rigidity of the slag and maintains high viscosity values, while the transition of the melt to a fully liquid state becomes possible only at relatively high temperatures. When transitioning from regions 1–2 to regions 3–4, a decrease in activation energy of approximately 99 kJ/mol is observed, indicating the initial stage of silicate network depolymerization; however, both regions remain characterized by high viscosity and limited fluidity.

Regions 5–9 are characterized by the predominance of the CaSiO3 (wollastonite) phase and are formed with a gradual increase in CaO content. Within this range, a decrease in the degree of silicate network polymerization is observed, resulting in a noticeable reduction in slag viscosity compared to silica-rich regions. However, due to the still insufficient CaO content, the rheological properties of the slag do not yet reach an optimal technological level. Consequently, Regions 5–9 exhibit a transitional character, reflecting the evolution from low-basicity silicate systems toward high-basicity calcium-containing slags.

Regions 10–12 correspond to the thermodynamic stability fields of rankinite (Ca3Si2O7) and belite (Ca2SiO4) phases in the Al2O3–CaO–SiO2 system and were selected in the present study as the primary working range for experimental smelting. In these regions, the CaO/SiO2 ratio reaches optimal values, leading to pronounced depolymerization of the silicate melt. The breakdown of the spatial silicate network is accompanied by a substantial decrease in viscosity and the formation of a highly fluid slag, creating favorable conditions for the free movement of metallic droplets, their coalescence, and efficient metal–slag separation.

According to the thermodynamic modeling results, within this range, the slag remains fully liquid in the temperature interval of 1600–1650 °C, and the phase equilibrium is characterized by relative stability. This ensures deep reduction of chromium and manganese and facilitates the separation of the metallic phase. In this context, the rankinite–belite region represents an optimal compromise between slag rheological properties and its metallurgical functions.

The temperature dependence of slag viscosity for regions 10–12 was described using the Frenkel–Andrade equation (Table 6). The calculated activation energy for viscous flow is Ea = 142.85 kJ/mol, indicating a relatively low degree of slag structure polymerization and reduced energy barriers for ionic transport. This activation energy value corresponds to the formation of a low-viscosity, highly fluid melt, ensuring the technological stability of the smelting process.

In this regard, precise selection and dosing of lime in experimental studies are of fundamental importance. Excessive CaO addition may shift the slag composition toward an ultra-high basicity region with an increased risk of solid phase formation, whereas insufficient CaO leads to increased viscosity and deterioration of the melt’s technological properties. Therefore, optimal CaO addition allows full realization of the advantages of the rankinite–belite region while minimizing adverse effects during system cooling.

Regions 13–16 are characterized by a further increase in CaO content and correspond to the formation of highly basic, including tricalcium, phases. In this range, the likelihood of free CaO and MeO-type phases increases, and the system shifts toward a high-temperature domain (≥1700 °C). Excessive slag basicity may enhance chemical aggressiveness, accelerate refractory lining wear, and increase the risk of phase instability, making these regions undesirable for industrial application.

Thus, slag compositions corresponding to regions 10–12 were selected for experimental investigations, as they exhibit thermodynamic stability, favorable rheological properties, and ensure efficient metal–slag separation. The calculated chemical compositions of the metallic and slag phases obtained from thermodynamic modeling are presented in Table 7. These data provide a scientific basis for planning and implementing experimental smelting trials, enabling a preliminary assessment of the effects of charge composition, temperature regime, and slag properties on the stability and efficiency of the metallurgical process.

Table 7.

Thermodynamically calculated compositions of metal and slag phases.

3.2. Experimental Melting Procedure

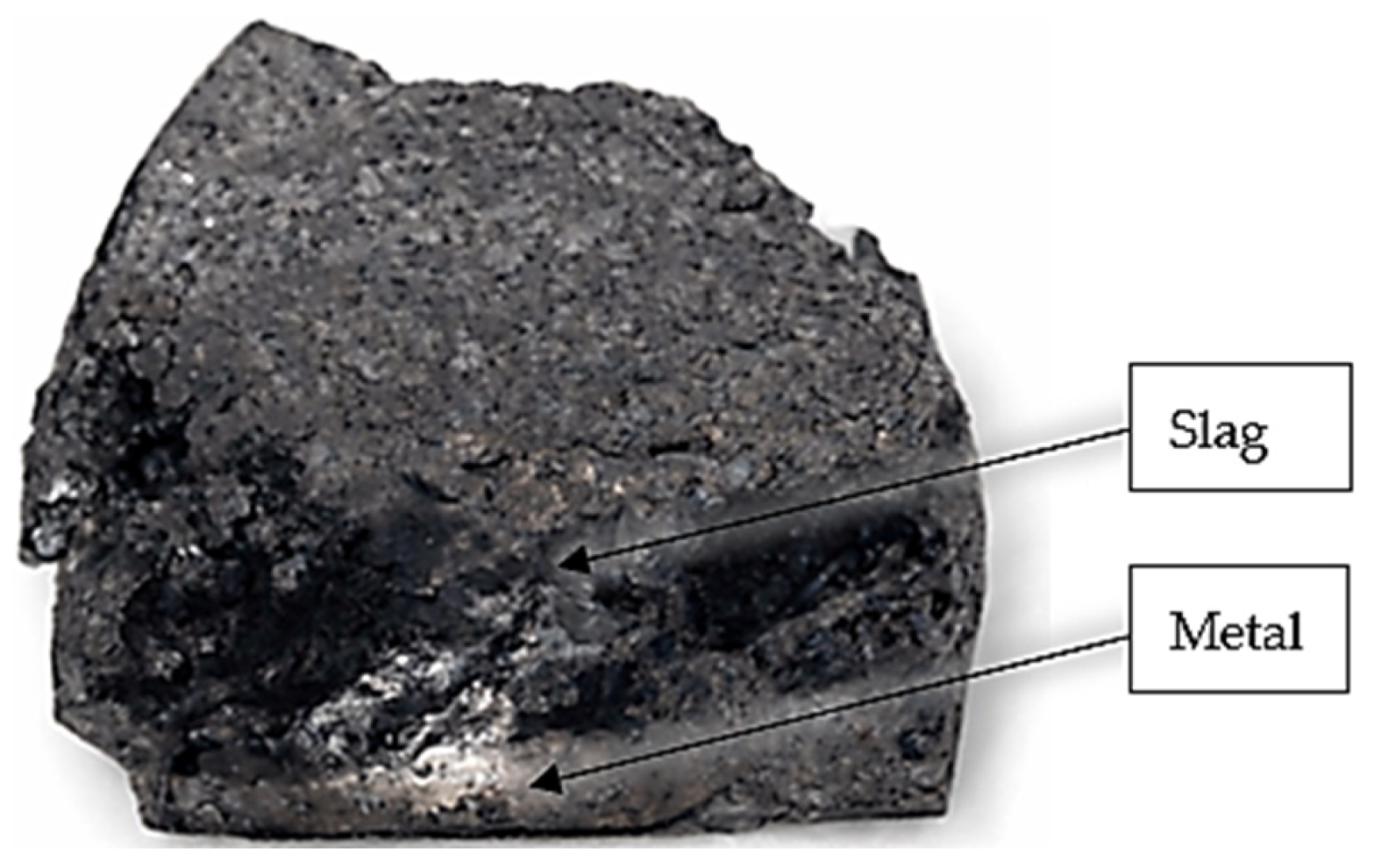

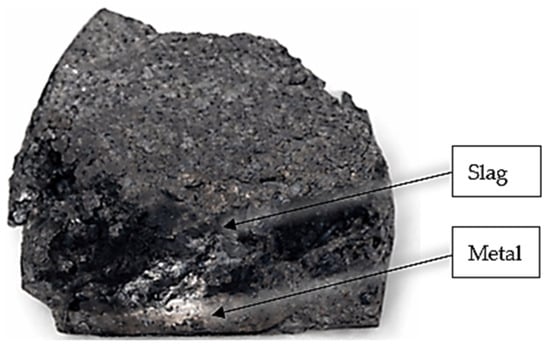

Based on the results of thermodynamic calculations, a charge mixture with a total mass of 130 g was prepared, consisting of 52 g of low-grade iron–manganese ore, 26 g of FeSiCr dust, and 52 g of CaO. Prior to smelting, the mixture was thoroughly homogenized manually in a porcelain mortar until a uniform mass was obtained. This ensured an even distribution of the components throughout the crucible volume and promoted uniform progression of reduction reactions and phase transformations during heating. The homogenized mixture was then loaded into an alumina crucible. Smelting was carried out in a Tammann furnace heated to 1600 °C, a temperature selected on the basis of thermodynamic modeling results, according to which the maximum recovery of Cr, Mn, and Fe is achieved under this temperature regime. The charge was held at the target temperature for 20 min, providing sufficient time for reduction reactions to proceed and for the formation of metallic and slag phases. After completion of the smelting process, the crucible was removed from the furnace and cooled to room temperature. The external appearance of the metallic and slag phases is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Appearance of the metal and slag products after experimental smelting of the Cr–Mn ligature.

After cooling, a clear separation of the metallic and slag phases was observed; the slag phase remained intact and did not undergo disintegration or dispersion. As a result of the experimental smelting, a Cr–Mn metallic phase was obtained with a composition consistent with the thermodynamic predictions.

After cooling, a clear separation between the metallic and slag phases was observed, with the slag remaining structurally stable and showing no tendency toward fragmentation. The obtained Cr–Mn metallic phase exhibited a chemical composition in good agreement with the thermodynamic predictions. The chemical composition of the metallic phase was determined by classical wet chemical analysis in accordance with standardized procedures specified in GOST 4757-91 [33] and GOST 4755-91 [34] and was found to be Fe (35.41 wt.%), Cr (41.10 wt.%), Mn (8.15 wt.%), and Si (4.31 wt.%).

It should be emphasized that thermodynamic modeling in the present study represents an idealized equilibrium description of a closed system and, by its nature, does not account for kinetic limitations of the real process. Factors such as reaction rates, diffusion constraints, heat and mass transfer with the surroundings, and finite holding time are therefore beyond the scope of the equilibrium thermodynamic approach. Under laboratory smelting conditions at 1600 °C, the attainment of complete thermodynamic equilibrium is practically unattainable; nevertheless, the experimental results confirm the validity of the thermodynamic trends identified and demonstrate the practical feasibility of the proposed process.

To assess the influence of kinetic effects and experimental reproducibility, a series of comparative smelting experiments was carried out with different durations of isothermal holding at 1600 °C (10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min). It was found that holding times shorter than 15 min resulted in an incomplete reduction of chromium and manganese, accompanied by increased metal losses to the slag phase. In contrast, prolonged holding beyond 25–30 min led to increased manganese losses, most likely due to evaporation and secondary oxidation. The most stable and reproducible results were achieved at an isothermal holding time of 20 min, which ensured the highest degree of chromium transfer to the metallic phase while minimizing manganese losses. These conditions were therefore selected as optimal and used for the experimental results reported in this work.

An important outcome of the present study is that the achieved manganese recovery to the metallic phase is comparable to or higher than that reported for conventional production routes of LC FeCr and LC FeMn alloys. This highlights the practical advantage of the proposed approach even at the laboratory scale and in the presence of unavoidable kinetic limitations. A comparative evaluation of the proposed process and conventional alloying approaches is summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Comparison of chromium–manganese alloying approaches based on literature data and the results of the present study.

Table 8 presents a comparative analysis of the manganese and chromium recovery levels obtained in the present study in comparison with those reported for conventional low-carbon FeCr and FeMn production, as well as with the authors’ previously published results. It is shown that, under the conditions of the present work, the use of FeSiCr dust as a reducing agent enables a high degree of manganese recovery from iron–manganese ore, along with effective utilization of chromium introduced into the system with the FeSiCr dust. The obtained results demonstrate the advantages of the proposed approach relative to conventional production routes and previously reported variants.

3.3. SEM–EDS Analysis

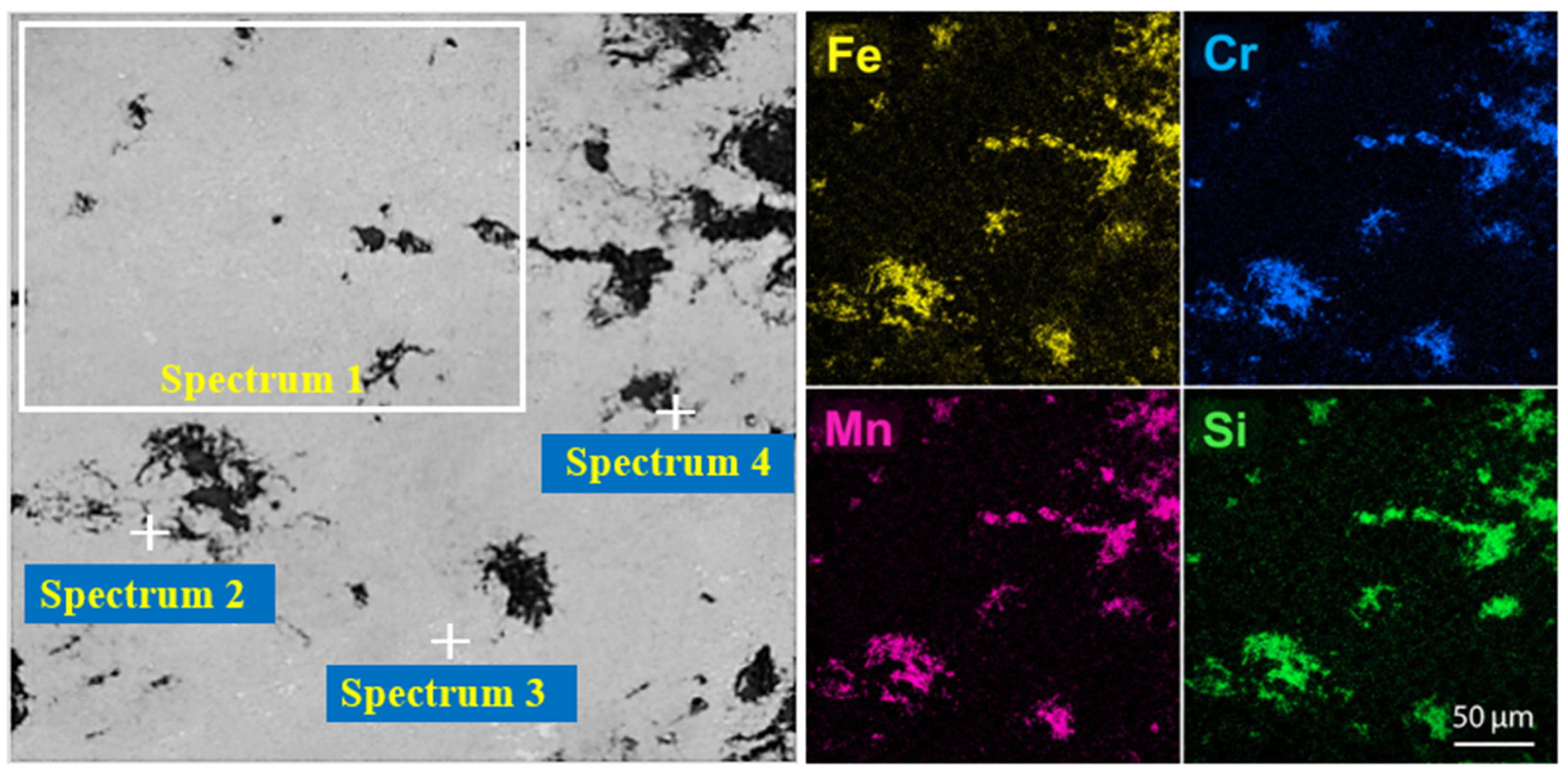

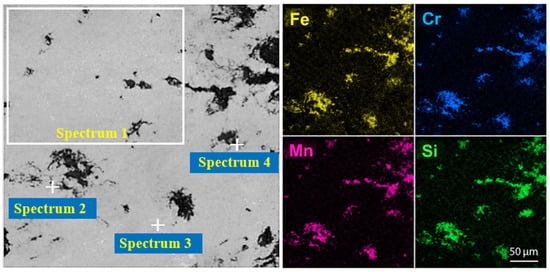

To confirm the phase composition and the distribution of the main elements in the products of experimental smelting, analyses were carried out using scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive spectroscopy. The SEM/EDS studies were performed on the samples obtained at an isothermal holding time of 20 min, as chemical analysis identified this duration as optimal for achieving maximum chromium recovery and effective phase separation. The morphology and microstructural features of the metallic and slag phases for this optimal regime are presented in Figure 10, where their clear phase differentiation can be distinctly observed. The quantitative results of the EDS analysis, which are semi-quantitative and intended for phase comparison rather than absolute composition, characterizing the chemical composition of individual phases and selected local regions, are summarized in Table 9. These data enable a direct comparison between the experimentally obtained results and the thermodynamic modeling outcomes, as well as an assessment of the agreement between the predicted and actual compositions.

Figure 10.

SEM images and EDS elemental distribution maps of the metallic and slag phases.

Table 9.

EDS quantitative analysis of selected regions (Spectra 1–4), mass %.

The SEM–EDS microstructural and phase analysis of the metallic phase revealed a multicomponent matrix with pronounced microstructural heterogeneity, which is typical for highly alloyed Fe–Cr–Mn–Si systems produced via reduction smelting. As shown in the elemental distribution maps, it is not obvious that there is a uniform distribution of the main elements within the metallic phase. Instead, the mapping results illustrate local concentration gradients, where specific areas are significantly enriched with certain alloying elements.

This non-uniformity is quantitatively confirmed by the EDS analysis of selected regions (Table 9). For instance, the manganese (Mn) concentration varies substantially, reaching a maximum of 63.11 wt.% in Spectrum 2, while dropping to 23.53 wt.% in Spectrum 3. Similarly, silicon (Si) exhibits strong local segregation in Spectrum 4 (25.72 wt.%), whereas in other regions like Spectrum 2, its presence is minimal, at 1.30 wt.%.

Such local compositional variations are attributed to the complex crystallization behavior and the redistribution of components during melt cooling. These variations indicate the formation of silicide and intermetallic phases that develop during the final stages of solidification under non-equilibrium conditions. Despite this local heterogeneity, no evidence of coarse macroscopic segregation or isolated secondary phases was detected, which confirms the metallurgical stability of the melt and the efficiency of the reduction reactions under the selected smelting parameters. Overall, the observed microstructural pattern is in good agreement with thermodynamic modeling, confirming a phase-stable system.

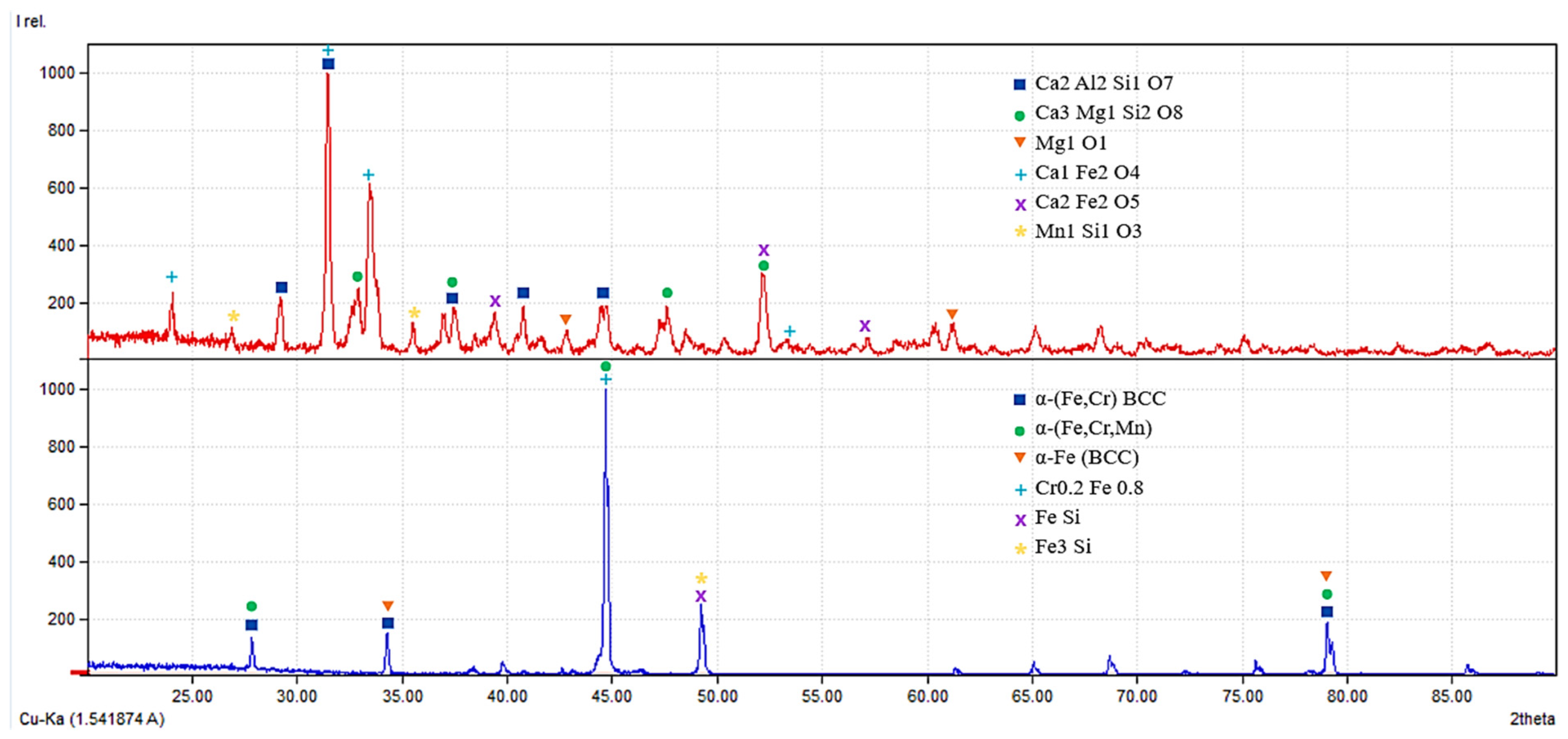

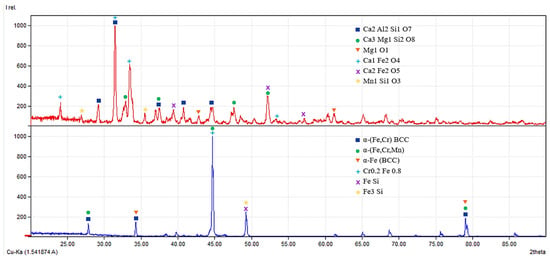

To further identify the phase composition of the formed metallic and slag systems and to verify the phase stability inferred from the SEM–EDS analysis, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed. The results of the phase identification for both metallic and slag phases are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the metallic and slag phases obtained after reduction smelting.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the slag (top) and metallic (bottom) phases obtained after reduction smelting. The slag phase is mainly composed of calcium aluminosilicate and silicate compounds (gehlenite, merwinite, periclase, calcium ferrite, and brownmillerite), while only trace amounts of manganese silicate phases are detected, indicating a low concentration of metallic components in the slag. The metallic phase is dominated by a stable α-(Fe,Cr) BCC solid solution with minor Fe–Si intermetallic phases, confirming the high efficiency of metal extraction and the formation of a structurally and phase-stable metallic system.

4. Conclusions

Based on the performed thermodynamic modeling and experimental verification, the feasibility of producing a complex Cr–Mn ligature from Kerege–Tas low-grade iron–manganese ore using FeSiCr dust as a reducing agent was scientifically substantiated. The application of the HSC Chemistry and FactSage software packages enabled the determination of rational process parameters and the evaluation of the effects of temperature, reducing agent consumption, and flux addition on the phase state of the metal–slag system.

It was established that at a smelting temperature of approximately 1600 °C, Low grade iron–manganese ore 100 kg, a FeSiCr dust consumption of about 50 kg, and the addition of 100 kg of lime, conditions are formed that ensure a high recovery of the main metals (Cr, Mn, and Fe) into the metallic phase while simultaneously promoting the formation of a thermodynamically stable slag. Under these parameters, the slag phase is localized within the stability field of rankinite–belite phases, corresponding to an optimal CaO/SiO2 ratio and providing favorable rheological properties of the melt.

Experimental smelting carried out under the selected laboratory conditions confirmed the general trends predicted by thermodynamic modeling and demonstrated the formation of clearly separated metallic and slag phases after cooling. X-ray diffraction analysis revealed that the metallic phase is dominated by a stable α-(Fe,Cr) solid solution with minor Fe–Si intermetallic phases, while the slag is primarily composed of calcium silicate and aluminosilicate phases. These findings are consistent with the predicted phase assemblages of the metal–slag system.

Microstructural analysis using SEM–EDS showed the formation of a multicomponent Fe–Cr–Mn–Si metallic matrix without pronounced macrosegregation, indicating favorable crystallization behavior under the applied laboratory smelting regime. The uniform distribution of the main alloying elements further supports the stability of the metallic phase formed under the investigated conditions.

Overall, the obtained results demonstrate the effectiveness of an integrated approach combining thermodynamic modeling with experimental validation for the preliminary development of technologies aimed at processing iron–manganese ores to produce complex Cr–Mn ligatures. The identified technological parameters should be regarded as indicative and as forming a scientific basis for further optimization rather than as finalized industrial conditions. The present study was conducted at the laboratory scale, and factors critical for industrial scale-up—such as furnace atmosphere, increased melt volume, manganese volatilization control, energy consumption, and kinetic effects—were beyond the scope of this work and will be addressed in future pilot-scale and semi-industrial investigations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and S.K.; methodology, Y.M., A.A. and A.S.; investigation, S.K., A.Z., A.B. and Z.S.; formal analysis, S.K., Z.S. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.M., A.S. and A.A.; visualization, S.K., S.A. and A.B.; supervision, Y.M. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP23488918).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Laboratory of Ferroalloys and Reduction Processes of the Zh. Abishev Chemical–Metallurgical Institute (Karaganda) for their valuable assistance and technical support provided during the research. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Resources, Energy and Environment, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway, for providing scientific support, research infrastructure, and an academic environment that contributed to the completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funding bodies had no involvement in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, or the decision to publish.

References

- Qiao, Y.; Ni, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Sun, B.; Bai, C. Iron-Based High-Temperature Alloys: Alloying Strategies and New Opportunities. Materials 2025, 18, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Meng, G.; Zhang, K.; Zuo, Z.; Song, X.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, S. Research Progress on Energy-Saving Technologies and Methods for Steel Metallurgy Process Systems—A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, J.L.; De Luca, A.; Dunand, D.C.; Dye, D.; Miracle, D.B.; Oh, H.S.; Olivetti, E.A.; Pollock, T.M.; Poole, W.J.; Yang, R.; et al. Sustainability through alloy design: Challenges and opportunities. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 117, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Wang, L. A review of energy use and energy-efficient technologies for the iron and steel industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 1022–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, D. The Materials Science behind Sustainable Metals and Alloys. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2436–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; Cui, C.; Zhang, Q.; Du, Z. Study on the role of chromium addition on sliding wear and corrosion resistance of high-manganese steel coating fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing. Wear 2024, 540–541, 205242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Xin, Y.; Yin, S.; Gao, L.; Shi, Z. Effect of Mn on Corrosion Resistance of Low-Cr Weathering Steel. Metals 2024, 14, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, W.; Wu, N.; Lyu, Y.; Guo, L.; Luo, F. Effect of Cr content and its alloying method on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-manganese steel-bonded carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2021, 101, 105698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghawry, M.M.; El-Basaty, A.B. Enhancing the corrosion resistance of high manganese steel through controlled chromium additions. Int. J. Met. 2025, 19, 3260–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyev, O.; Abdirashit, A.; Almagambetov, M.; Nurgali, N.; Kelamanov, B.; Yessengaliyev, D.; Mukhambetkaliyev, A. Assessment of Physicochemical Properties of Dust from Crushing High-Carbon Ferrochrome: Methods for Agglomeration. Materials 2025, 18, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sariyev, O.; Almagambetov, M.; Nurgali, N.; Abikenova, G.; Kelamanov, B.; Yessengaliyev, D.; Abdirashit, A. Development of a Briquetting Method for Dust from High-Carbon Ferrochrome (HC FeCr) Crushing Using Vibropressing on an Industrial Scale and Its Subsequent Remelting. Materials 2025, 18, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdirashit, A.; Kelamanov, B.; Sariyev, O.; Yessengaliyev, D.; Abilberikova, A.; Zhuniskaliyev, T.; Kuatbay, Y.; Naurazbayev, M.; Nazargali, A. Study of Nickel–Chromium-Containing Ferroalloy Production. Processes 2025, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyev, O.; Kelamanov, B.; Dossekenov, M.; Davletova, A.; Kuatbay, Y.; Zhuniskaliyev, T.; Abdirashit, A.; Gasik, M. Environmental Characterization of Ferrochromium Production Waste (Refined Slag) and Its Carbonization Product. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdirashit, A.; Yessengaliyev, D.; Kelamanov, B.; Sariyev, O.; Abikenova, G.; Nurgali, N.; Almagambetov, M.; Zhuniskaliyev, T.; Kuatbay, Y.; Abylay, Z. Investigation of the Possibility of Obtaining Nickel-Containing Ferroalloys from Lateritic Nickel Ores by a Metallothermic Method. Metals 2025, 15, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubaschewski, O.; Alcock, C.B.; Spencer, P.J. Materials Thermochemistry, 6th ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gasik, M. Handbook of Ferroalloys: Theory and Technology; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fruehan, R.J. The Making, Shaping and Treating of Steel: Steelmaking and Refining; AISE Steel Foundation: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1998; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, I.; Min, D.J. A review of the relationship between viscosity and the structure of calcium-silicate-based slags in ironmaking. Steel Res. Int. 2012, 83, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Bernhard, C.; Mayerhofer, A.; Michelic, S.K. Influence of slag viscosity and composition on the inclusion content in steel. ISIJ Int. 2021, 61, 2991–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tang, K.; Tangstad, M. Reduction and dissolution behaviour of manganese slag in the ferromanganese process. Minerals 2020, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, V.; Tangstad, M. Kinetics of manganese reduction comparing synthetic slags and ores for ferromanganese production. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2025, 56, 2731–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsomondo, M.B.C.; Simbi, D.J. Kinetics of chromite ore reduction from MgO–CaO–SiO2–FeO–Cr2O3–Al2O3 slag system by carbon dissolved in high carbon ferrochromium alloy bath. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2002, 29, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Qing, G.; Zhao, B. Phase Equilibria Studies in the CaO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2 System with Al2O3/SiO2 Weight Ratio of 0.4. Metals 2023, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetov, A.; Zulhan, Z.; Sadyk, Z.; Burumbayev, A.; Zhakan, A.; Kabylkanov, S.; Toleukadyr, R.; Saulebek, Z.; Ayaganova, Z.; Makhambetov, Y. Carbon-Free Smelting of Ferrochrome Using FeAlSiCa Alloy. Processes 2025, 13, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhambetov, Y.; Sadyk, Z.; Zhakan, A.; Burumbayev, A.; Kabylkanov, S.; Myrzagaliyev, A.; Aubakirov, D.; Lu, N.; Akhmetov, A. Electric Arc Metallothermic Smelting of FeCr Using FeAlSiCa as a Reductant. Materials 2025, 18, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhambetov, Y.; Zhakan, A.; Zhunusov, A.; Kabylkanov, S.; Burumbayev, A.; Sadyk, Z.; Akhmetov, A.; Uakhitova, B. Resource-Efficient Smelting Technology for FeCrMnSi Ferroalloy Production from Technogenic Wastes in an Ore-Thermal Furnace. Metals 2025, 15, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhambetov, Y.; Abdulina, S.; Kabylkanov, S.; Burumbayev, A.; Zhakan, A.; Sadyk, Z.; Akhmetov, A. Production of Chromium–Manganese Ligature from Low-Grade Chromium and Iron–Manganese Ores Using Silicon–Aluminum Alloys as Reductants. Processes 2025, 13, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsanga, N.; Tangstad, M.; Kalenga, M.W.; Nheta, W. Manganese Alloy Production—A Review of the SAF Process and Emerging Technologies. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 44840–44857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangstad, M.; Bublik, S.; Haghdani, S.; Einarsrud, K.E.; Tang, K. Slag Properties in the Primary Production Process of Mn-Ferroalloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2021, 52, 3688–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druinsky, M.I.; Zhuchkov, V.I. Production of Complex Ferroalloys from Mineral Raw Materials of Kazakhstan; Nauka: Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1988; p. 208. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kazchrome. TNC Kazchrome JSC Annual Report for 2024; TNC Kazchrome JSC: Aktobe, Kazakhstan, 2025; Available online: https://www.kazchrome.com/en/investors/disclosures/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- HSC Chemistry. Database Applications—HSC Chemistry. chemIT Services. Available online: https://www.chemits.com/en/software/database-applications/hsc-chemistry.html (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- GOST 4757-91; Ferromanganese. Specifications. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 1991.

- GOST 4755-91; Ferrosilicomanganese. Specifications. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 1991.

- Xu, J.; Duan, Q.; Deng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Gao, L. Valuable Recovery Technology and Resource Utilization of Chromium-Containing Metallurgical Dust and Slag. Metals 2023, 13, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.