Abstract

The paper presents a follow-up on the subject of the use of thermal analysis for the generation of fraction solid evolution in cast alloys, particularly in aluminum—silicon alloys. It discusses in detail the importance of correctly determining the characteristic temperatures of the cooling curve, including the beginning of solidification, the eutectic temperature, and the end of solidification. It demonstrates the importance of the smoothing techniques applied to the experimentally recorded temperature (cooling curve). Newtonian and Fourier analyses are used to generate the evolution of fraction of solid and the latent heat on cups of different diameters, to assess the effect of cooling rate for Al-7.5%Si alloys. Calculation results are compared with the literature data. It was found that the maximum temperature of the alloy in the cup affected the overall results.

1. Introduction

The goals of thermal analysis of cooling curves of metal casting alloys are to establish the characteristic temperatures (liquidus TL, eutectic, TE, and solidus, TS) that are then used as the input parameters to calculate relevant solidification quantities such as fraction solid evolution, latent heat, phase transformation, etc. These characteristic temperatures are functions of the experimental measuring device and of the experimental procedure. The size and material of the test cup (e.g., steel or sand), and the temperature at which the alloy is collected in the test cup directly affect the characteristic temperatures, as they determine the cooling rate during solidification. The recorded cooling curve shows a maximum temperature, , that is related to the temperature at which the molten alloy is collected from the melting furnace but, in most cases, this is lower than the collection temperature, because of temperature loss during transfer.

In metalcasting practice, there are two basic methods of filling the test cups. The most common is to extract the liquid metal from the melting furnace with a small ladle and then pour it into a test cup instrumented with one or more thermocouples (e.g., Leeds and Northrup method). Alternatively, the molten metal may be held in a transfer ladle until it reaches a specified temperature, before pouring into the test cup. Another method consists of submerging the test cup in the intermediate ladle with the molten metal at the target temperature and then allowing the temperature in the cup to reach the temperature in the ladle. At that point, the cup is removed from the ladle, and the cooling curve is recorded as the alloy cools (e.g., the Sintercast method).

Another defining factor is the smoothing technique and the level of smoothing of the thermocouple data, as the raw data inherently exhibit experimental noise [1].

Standard thermal analysis techniques use a single cup, which means a single cooling rate. The goal of this paper is to document the effects of the cooling rate of cups of different sizes and of the smoothing level of the experimental data on the characteristic temperatures of the cooling curve, and then, on the resulting latent heat and fraction solid evolution, via two different mathematical approaches, i.e., Newtonian and Fourier analysis. This information is needed for software to predict porosity in castings.

2. Theoretical Background

The theory behind Newtonian analysis has been previously discussed by several authors, e.g., refs. [2,3,4,5,6]. The equations used in this work are summarized in Table 1. The Fourier analysis is based on the paper by Fras, Kapturkiewicz et al. [7] and the follow-up work in refs. [8,9,10]. The equations used in this work are summarized in Table 2. For a recent detailed analysis, see ref. [1].

Table 1.

Equations used in the Newtonian analysis.

Table 2.

Equations used in the Fourier analysis.

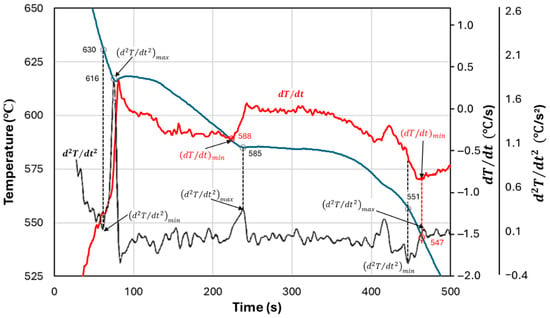

The results of the calculations in Table 1 depend on characteristic temperatures including the initial liquidus temperature (), the eutectic temperature (), and the solidification temperature (). In previous work [1], we investigated the effect of initial temperatures, considered to be , or , adapted from Bäckerud et al. [3]. Further illustration of possible selections of the critical temperatures is provided in Figure 1. However, this selection is reconsidered in Figure 2 and in the discussion that follows.

Figure 1.

Effect of the method for establishing the critical temperature on the obtained temperature for an Al7.5Si alloy poured in a D55 cup (adapted from Ref. [1]).

Figure 2.

Assumptions in the establishing of the initial temperatures: (a) characteristic temperatures and cooling rates; (b) example of selection of .

Solidification is assumed to start when the fraction solid in the melt becomes . At that time, the solidification heat released produces an inflexion on the cooling curve at a temperature defined as . However, the precise result for this temperature depends on the accuracy of the experimental measurements.

As discussed in earlier work, considerable noise may affect pinpointing and the moment when the . Using the maximum of the second time derivative of temperature, , to find the inflexion on the curve may bring the temperature significantly lower than , as the heat released initially may be very small. In this work, was taken as the temperature corresponding to the preceding (Figure 2b). This temperature of 622.8 °C is higher than 619.6 °C corresponding to .

According to Bäckerud et al. [3], the nucleation temperature, , which is the initial temperature in the calculations for , is positioned in time before and is lower than . However, the inflexion in this work was found to generate a higher than . In the example in Figure 2b for cup D40, is at a temperature of 619.6 °C, slightly above the 619.3 , while is at 622.8. For the other two cups, selection of based on the criterion before produces , as shown in Figure 2a.

The beginning of the eutectic temperature, , was selected as . The final temperature, which is the solidification temperature, , can be taken either as or as [1]. In this work, was selected based on , as in most papers on the subject, e.g., [4,7,10,11].

Data required for the calculations extracted from ref. [1] are presented in Table 3. It can be seen that the latent heat for the alloy of interest varies from 389 to 424 kJ/kg. Also, two values are suggested for i.e., 1.139 and 1.35 °C.

Table 3.

Experimental and tabulated data.

3. Materials and Methods

A Daesung Co. Ltd. (Seoul, Republic of Korea), EF4000 electric resistance furnace, 200 mm in diameter and 800 mm in height was used for melting the aluminum alloy. The specific power consumption of the furnace was 4 kW/h, and its maximum operating temperature was 1200 °C.

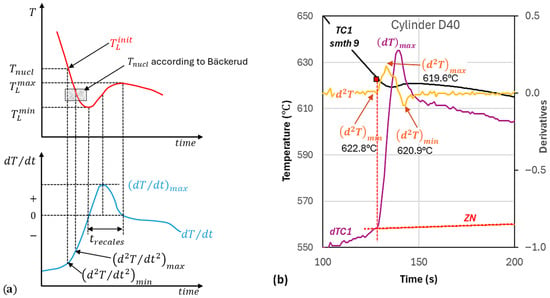

A series of experiments were conducted with three test cylindrical cups of different diameters. The cups were instrumented with three thermocouples each, one in the center and the other two close to the wall of the cup. Only two out of three thermocouples were used, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 (thermocouples in red). The type-K thermocouples were connected to a data acquisition system that converted the analog temperature signals into digital form. The temperature recorder operated with a sampling interval of 0.1 s and a minimum resolution of 0.1 °C, ensuring sufficient accuracy and reliability in the temperature measurements.

Figure 3.

Dimensions of the experimental cylindrical cups and positions of the thermocouples.

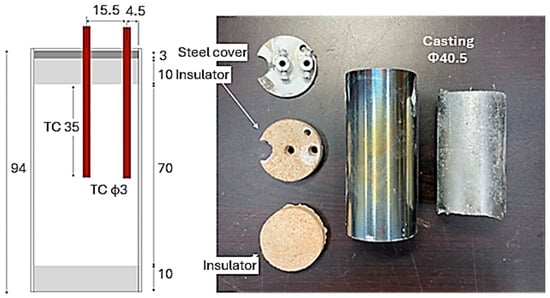

Figure 4.

Details of the construction of Cup D40.

The composition of the Al-7.5%Si alloy used in this research was as follows (in wt.%): 7.52Si, 0.35Mg, 0.15Fe, 0.0021Ca, 0.0034Cu, 0.00074Li, 0.0032Mn, 0.0023Sn, 0.014Ti, 0.0085V, 0.0026Zr, 91.94Al. After inserting the cup into the crucible and filling the cup with molten aluminum, the cup was suspended in air, as shown in Figure 5, and allowed to cool in air. Temperature measurements were obtained with K-type thermocouples. The signal was converted through an analog-to-digital (A/D) transformer and acquired by a data acquisition (DAQ) system. The temperature was recorded at 0.1 s intervals with a resolution of 0.1 °C.

Figure 5.

Cooling of cylindrical cup to allow solidification of the molten alloy.

4. Results and Discussion

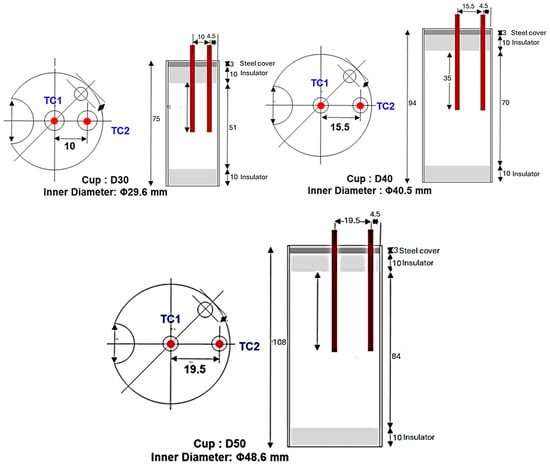

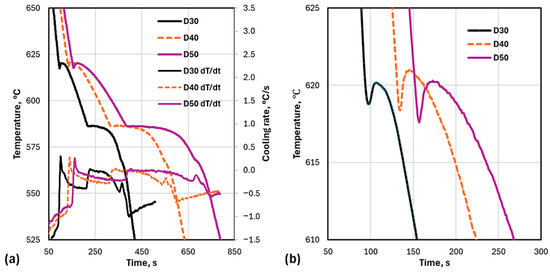

The experimentally recorded cooling curves and their calculated derivatives are presented in Figure 6. As seen in Table 4, while the cooling rate decreased from D30 to D50, the recalescence temperature (max. liquidus temperature, ) for D40 (620.9 °C) was higher than the respective temperatures for D30 (620.2 °C) and D50 (620.3 °C). Further analysis revealed that this anomaly was caused by the fact that D40 had the lowest maximum temperature according to the thermocouple, , from the three samples (771 °C in Table 4).

Figure 6.

Cooling curves of the three experimental cups: (a) cooling curves (raw data) and first derivatives (calculated with 9-point smoothing); (b) detail of liquidus arrest.

Table 4.

Maximum recorded temperatures and cooling rates.

An additional important factor affecting the outcome of calculations is the smoothing technique applied to the raw experimental data, as discussed in some detail in ref. [1]. Accurate determination of the starting point, , and of the final temperature, , is strenuous and open to errors because of the experimental data noise of the recorded cooling curves.

To calculate the latent heat of solidification, both Newtonian and Fourier analyses were used. The basic equations are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

4.1. Newtonian Analysis

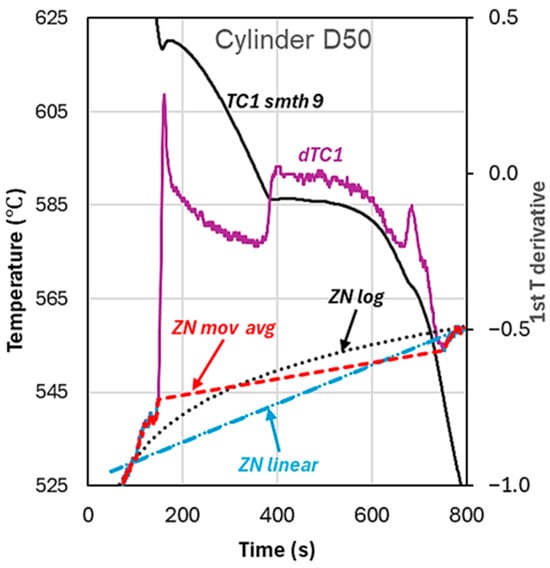

As discussed in a previous paper [1], the calculated fraction solid and latent heat () are heavily dependent on the characteristic temperatures, i.e., the initial liquidus temperature () and the final solidus temperature () used in calculations. A second problem is the generation of the zero curve, ZN. There are several solutions for Newtonian analysis advanced by researchers, e.g., refs. [4,5,11,15,16,17,18]. See also the review paper by Labrecque and Gagné [19]. Examples of the three methods have been also previously summarized (Figure 7, ref. [20]). However, none of the solutions for ZN can produce a correct evolution of the fraction solid, or an indisputable value for the latent heat, because the basic assumption of the Newtonian calculation, which is constant temperature across the diameter of the experimental cup, is not true. Some of the possibilities used by different researchers are illustrated in Figure 7. We note that the third-order polynomial ZN calculated by Kierkus and Sokolowski [11] is very close to the linear ZN. It must be emphasized that the calculated ZN depends not only on the fitting method, linear, logarithmic, or other method, but also on the number of data points selected before and after solidification.

Figure 7.

Various methods of calculation for the Newtonian Zero Curve, ZN, using values on the first derivative, dTC1, before the beginning and after the end of solidification.

Consequently, in this work, ZN was the line joining and on the first time derivative of temperature. Compared with the logarithmic ZN over points before and after solidification (see, for example, Djurdjevic [18]), this approximation is reasonable, as the overestimation of the latent heat is small.

The methodology for determining the critical temperatures is presented in Table 5. Note that in this work, is taken as the temperature corresponding to the minimum of the second time derivative of temperature, , that precedes in time the . is defined by the first derivative of temperature, .

Table 5.

Effect of the smoothing level on calculated critical temperatures, fraction solid, and latent heat.

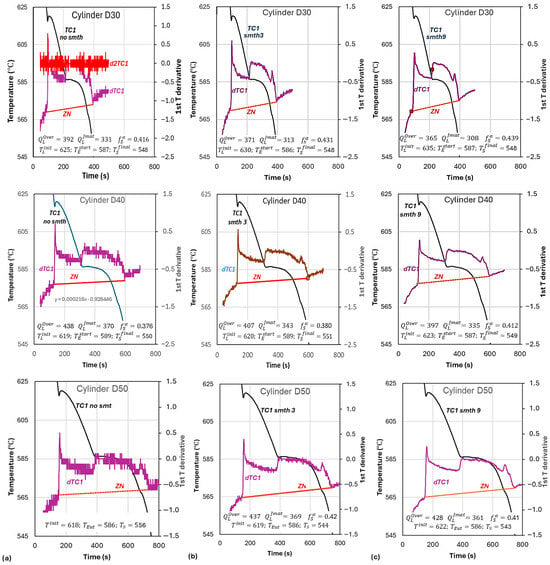

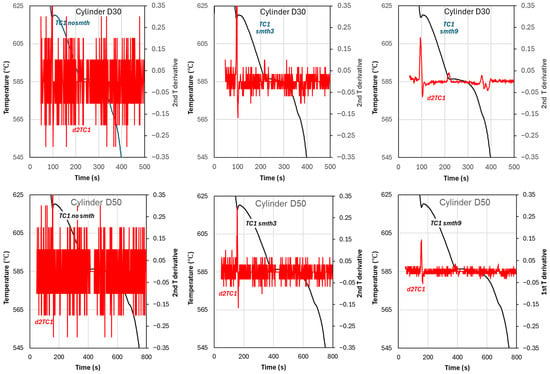

From the experimental and calculated data in Table 5, which also includes the cooling rates in the three cups, it was observed that the level of smoothing affected the outcome of the calculations. As experimental data noise is a problem, three levels of smoothing were used, i.e., no smoothing, three-point data smoothing, and nine-point data smoothing. The results of the Newtonian analysis of the experimental data are summarized in Figure 8; the data noise for cup D30 is illustrated as an example (no smoothing for temperature and for the first and second temperature derivatives). Data noise can be so bad that, as seen in Figure 8, cup D50, no smooth, at the end of solidification includes the same value (−0.6) over a time of 19 s. It is practically impossible to determine a unique and/or because of the high noise and therefore, the high number of options for the critical temperature in the calculated and curves. As smoothing is applied to the recorded data, the degree of error in selecting the critical temperatures decreases, but the calculated values are affected.

Figure 8.

Effect of smoothing of the 1st derivative data (cooling rate) and of the cup size on calculated latent heat: first row D30; second row D40; third row D50. (a) No smooth; (b) smooth 3; (c) smooth 9.

Table 5 also includes the calculated latent heat using the specific heats recommended by JMatPro and Overfelt, as listed in Table 3. Tabulated data for in Table 3 range from 389 to 424 kJ/kg. Compare this with data for cup D50 in Table 5, which are 361 for JMat cp, and 428 for Overfelt cp. This also illustrates the significant role that the selection of the specific heat plays in the calculation of the latent heat.

4.1.1. Effect of Smoothing

The effect of smoothing on the first and second temperature derivatives is illustrated in Figure 9. The correct establishment of the critical temperatures, in particular, , is impeded by the data noise affecting the time derivatives. Examples are provided in Figure 9 for cups D30 and D50. The inflexion of the cooling curve, where is taken for Newtonian analysis, is determined by .

Figure 9.

Effect of temperature smoothing on the second time derivatives of temperature (d2T): first row for cups D30; second row for cups D50.

In Figure 9, the second row shows that the plurality of minima for D50 is either −0.03 or −0.07. This makes it impossible to determine the precise location of without further assumptions. This problem reflects the need for better smoothing techniques such as polynomial interpolation. In addition to the high noise for no-smooth and three-point-smoothed data, Figure 9 also shows a significant decrease in the maximum and minimum of and with higher smoothing level. This affects the calculated latent heat.

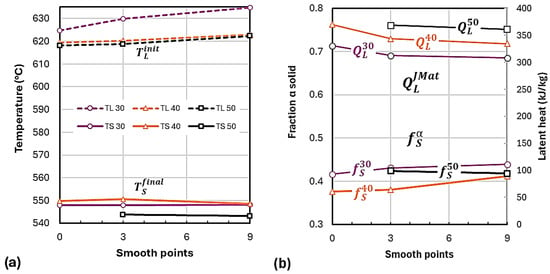

The effect of smoothing on the quantities of interest, , , , and , is illustrated in Figure 10. increases slightly with higher smoothing for all cup diameters (Figure 10a), with D50 exhibiting the lowest . shows less clear behavior. If just the effect of smoothing is considered, the value of this temperature should increase with higher cooling rate. However, the data in the figure show that D40 does not respect this sequence as it has a higher than D30. This anomaly, also seen for the liquidus arrest in Figure 6b, is caused by the low maximum temperature recorded by the D40 thermocouple (see Table 4). As a result, D40 had the lowest solid fraction among the three cups (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Effects of smoothing on various parameters for cups 30, 40, and 50 (a) on the initial and final temperatures; (b) on the latent heat and fraction solid for the JMat .

The second row in Figure 9 also demonstrates that the value of the calculated latent heat decreased with the smoothing level. As expected, the lowest latent heat was for the largest cup, . This analysis demonstrates the need to have all three cylindrical cups in the same mold so that they can be poured at the same temperature and thus experience the same maximum temperature.

4.1.2. Effect of Cooling Rate (Cup Size)

The effect of cooling rate on calculated data extracted from Table 5 and Figure 8 is summarized in Figure 11 for latent heat and fraction solid. No D50 latent heat data are included in Figure 11a, because no could be established for D50 with no smoothing. It is seen that, for the same , the latent heat decreased with a higher cooling rate (increasing with the cup size) and it was also sensitive to the selection. For smth-9, changed from 365 for the JMat to 428 for the Overfelt , compared with the literature data (Table 3) of 389 to 424 kJ/kg.

Figure 11.

Effect of cooling rate of the test cups on the fraction solid of α-phase at the eutectic temperature () and on latent heat, for Newtonian analysis: (a) No smooth; (b) smooth 3; (c) smooth 9.

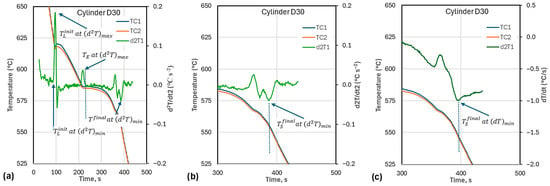

4.2. Fourier Analysis

For the Newtonian calculation, results for the parameters of interest rely heavily on the values of the characteristic temperatures extracted from the experimental cooling curves. The methodology used to estimate critical temperatures is summarized in Figure 12. For the initial temperature, , or can be selected (Figure 12a). For the final temperature, , two methods may be used: as shown in Figure 12a,b, or as shown in Figure 12c. Only smooth-9 data were used in the Fourier analysis. A summary of experimental results and analysis is presented in Table 6. As most literature data are for at , the calculations of α, , and were performed for this final temperature.

Figure 12.

Evaluation of significant temperatures , , and using the 1st and 2nd time derivatives of temperature. (a) use of to determine beginning and end of solidification; (b) detail for end of solidification; (c) use of to find the end of solidification.

Table 6.

Fourier analysis of smooth-9 experimental data.

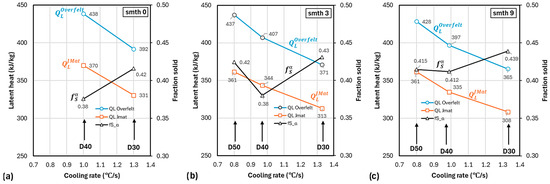

The assumption for the initial temperature has a major effect on the outcome of the Fourier calculation results, as seen in Table 6 and Figure 13. Both the table and the figures reveal that the selection delivers the highest latent heat.

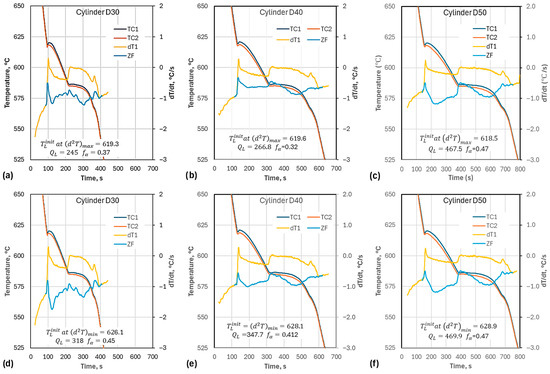

Figure 13.

Effect of the selection of the initial temperature on latent heat and fraction solid calculations for smooth-9 , based on JMat . (a) cylinder D30; at ; (b) cylinder D40; at ; (c) cylinder D50; at ; (d) cylinder D30; at ; (e) cylinder D40; at ; (f) cylinder D50; at .

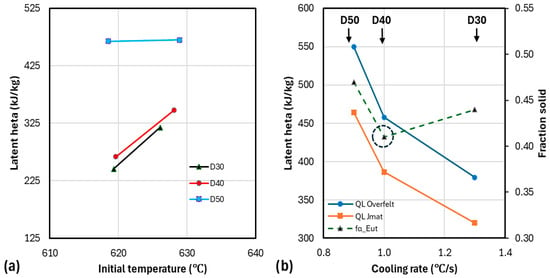

A graphic illustration of this statement is shown in Figure 14a. The assumptions for the initial temperature sequence on the figure are and . It can be seen that the difference between calculated with and that for is significant. D50 exhibits an apparent exception to this observation. This is attributed to the fact that as D50 solidified close to equilibrium, very little additional fraction solid was produced by changing . The cooling curve for D50 shows the lowest maximum temperature of all three samples (see Table 4). For comparison, the experimental and tabulated values in Table 3 range from 389 to 424 kJ/kg. It can be seen that, in the case of cup D30, the selection of the method affected the result by 9 °C.

Figure 14.

The effect of experimental variables on calculation of latent heat for Fourier analysis on smooth-9 data: (a) effect of initial temperature; (b) effect of cooling rate on latent heat and fraction of solid (α-phase).

As expected, the latent heat increased as a higher initial temperature was chosen, although only slightly for D50, and with the size of the cup (Figure 14a), but decreased with higher cooling rate (Figure 14b). The fraction solid of the α-phase at the eutectic temperature, , should have decreased with the higher cooling rate. It did for D50 to D30, but again, D40 presents a striking exception as it exhibits a smaller (see dotted circle on the figure).

4.3. Fraction Solid

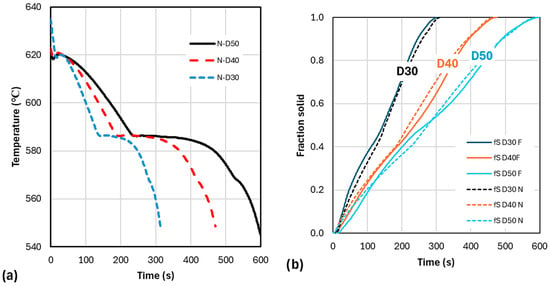

As stated in the introduction, the goal of this work was to establish a method for predicting the time-evolution of fraction solid from experimental data. A comparison between the cooling curves and the time evolution of Newtonian and Fourier calculated fraction solids is given in Figure 15. For the smooth-9 Newtonian analysis, the fraction of primary phase at the eutectic temperature, , varies from 0.44 to 0.41 to 0.42 for D30 to D40 to D50, respectively. For the smooth-9 Fourier analysis, the same sequence gives 0.45 to 0.41 to 0.47. Note that in both cases D40 has the lowest fraction solid. Overall, there is a clear difference between the Newtonian and Fourier evolutions of , further confirmed in Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Evolution of smooth-9 cooling curve (a) and of fraction solid (b) for Newtonian and Fourier calculations.

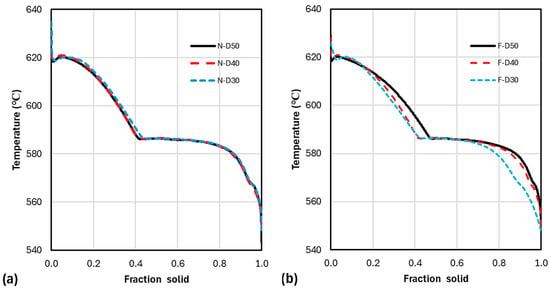

Figure 16.

Temperature–fraction solid evolution (smooth-9) for Newtonian (a) and Fourier (b) analysis.

The temperature–fraction solid curves for the three different size cups are almost superimposed in the Newtonian analysis (Figure 16a). By contrast, in the Fourier analysis, the effect of cooling rate is clearly visible (Figure 16b). The eutectic transformation starts at a lower for D30 (cooling rate 1.64 °C/s) than for D50 (cooling rate 1.17 °C/s), as expected, because of the higher undercooling. However, for D40, the eutectic starts at the same as for D30. This is because of the lower of D40.

5. Conclusions

Fraction solid evolution during the solidification of an Al-7.5%Si alloy was calculated based on the recorded cooling curves obtained from cylindrical steel cups with three different diameters. The cups were submerged in an induction furnace with molten Al-7.5%Si alloy. Once full, the cups were allowed to cool in air while the cooling curve was recorded with thermocouples. The recorded cooling curves were used to deliver information on the latent heat evolution during solidification and on the time evolution of fraction solid during solidification. Calculation of the latent heat and of the fraction solid was based on the calculation of the area between the recorded cooling curve and its corresponding zero-curve, ZC, which is a cooling curve of the liquid metal assuming no transformation (no latent heat produced). To calculate the ZC, either the Newtonian or the Fourier analysis method may be applied. Both these methods were used in this report. The Fourier analysis was conducted only on data averaged over nine points (smooth-9).

The paper demonstrates that the raw temperature data recorded by the thermocouples cannot be used in this analysis because of the data-acquisition noise, and consequently, smoothing subroutines must be employed. The time averaging over time step smoothing technique was used in this paper. It was found that the level of smoothing (number of data points over which the temperature was averaged) significantly affected the selection for the initial temperature, , which is the temperature at which the solidification starts. For example, for cup D40, the Newtonian analysis produced the following results: (a) for no smoothing, = −0.1 and = 619.3 °C; (b) for smoothing over three data points, ( = −0.03 with = 620.2; (c) for five-point smoothing, = 0 and = 622.8. This is an increase of 3.5 °C that affects the fraction solid values.

It was also found that, for the same , as expected, the latent heat, , decreased with a higher cooling rate. However, the calculated is highly dependent on the selection, as is directly proportional to . For smooth-9, changed from 365 for the JMat to 428 for the Overfelt . These values are both at the outside range of the literature data, which is 389 to 424 kJ/kg.

The thermal diffusivity (α) calculated in the Fourier analysis was affected by both the selection criterion for and the cooling rate, i.e., the size of the cup. However, for D50, α remained constant even when increased. The result was that the fraction solid remained constant at 0.47 for all variants of .

The calculated data were significantly affected by the maximum temperature registered by the thermocouple, supporting the requirement that all cups should have the same initial temperature. This approach is used in several industrial TA methods, such as Sintercast [21]. Furthermore, the results presented in this paper are particularly important for applications where the evolution of fraction solid during solidification is needed to calculate outcomes such as porosity location in the casting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.S., D.R. and E.K.; methodology, D.M.S. and D.R.; software, E.K. and D.K.; formal analysis, D.M.S.; investigation, E.K., D.K. and H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.S.; writing—review and editing D.R., E.K., D.K. and H.K.; supervision, D.R.; project administration and funding acquisition, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Korea Planning and Evaluation of Industrial Technology (KEIT) grant for development of 3.0 GPa% grade aluminum alloy and casting analysis technology for high vacuum die casting (20020283).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

EungSu Kweon, DongHoon Roh, DongYoon Kang and HuiChan Kim were employed by the company AnyCasting Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kweon, E.S.; Roh, D.H.; Kang, D.Y.; Stefanescu, D.M. The Use of Thermal Analysis for Generation of Fraction Solid Evolution in Al-Si alloys. Inter. Metalcat. 2025, 19, 3194–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabus, D.; Polten, S. Interpretation of Solidification Structures in Castings by Means of Differential Thermal Analysis. Giess. Rundsch. 1972, 9, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckerud, L.; Nilsson, K.; Steen, H. The Metallurgy of Cast Iron; Lux, B., Minkoff, I., Mollard, F., Eds.; Georgi Publishing: St. Saphorin, Switzerland, 1975; p. 625. [Google Scholar]

- Ekpoom, L.; Heine, R.W. Thermal analysis by differential heat analysis (DHA) of cast iron. Trans. Am. Foundry Soc. 1981, 89, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I.G.; Stefanescu, D.M. Computer-Aided Differential Thermal Analysis of Spheroidal and Compacted Graphite Cast Irons. Trans. Am. Foundry Soc. 1984, 92, 947–964. [Google Scholar]

- Djurdjevic, M.B.; Manasijevic, S.; Patarić, A.; Mihailović, M. Challenges by latent heat calculation—Competition among analytical and computational methods. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 157, 107704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fras, E.; Kapturkiewicz, W.; Burbielko, A.; Lopez, H.F. A New Concept in Thermal Analysis of Castings. AFS Trans. 1993, 101, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, J.O.; Stefanescu, D.M. Computer-Aided Cooling Curve Analysis Revisited. AFS Trans. 1997, 105, 349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Emadi, D.; Whiting, L.V.; Djurdjevic, M.; Kierkus, W.T.; Sokolowski, J. Comparison of Newtonian and Fourier thermal analysis techniques for calculation of latent heat and solid fraction of aluminum alloys. Metal. J. Metall. 2004, 10, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diószegi, A.; Hattel, J. Inverse thermal analysis method to study solidification in cast iron. Int. J. Cast Met. Res. 2004, 17, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierkus, W.T.; Sokolowski, J.H. Recent advances in CCA: A new method of determining ‘baseline’ equation. AFS Trans. 1999, 66, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Overfelt, R.A.; Bakhtiyarov, S.I.; Taylor, R.E. Thermophysical properties of A201, A319, and A356 aluminium casting alloys. High Temp. High Press. 2002, 34, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, Y.D.; Zhou, H.W. Effects of Pouring Temperature on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the A356 Aluminum Alloy Die castings. Mater. Res. 2020, 23, e20190676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itamura, M.; Yamamoto, N. Effect of silicon content on latent heat of Al-Si alloys. J. Jpn. Foundry Eng. 1996, 68, 493–498. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanescu, D.M.; Upadhya, G.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Heat Transfer-Solidification Kinetics Modeling of Solidification of Castings. Metall. Trans. A 1990, 21, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanescu, D.M. Solidification of Flake, Compacted/Vermicular and Spheroidal Graphite Cast Iron as Revealed by Thermal Analysis and Directional Solidification Experiments. MRS Symp. 1985, 34, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizaga, A.; Niklas, A.; Fernandez-Calvo, A.I.; Lacaze, J. Thermal analysis applied to estimation of solidification kinetics of Al–Si aluminum alloys. Int. J. Met. 2009, 22, 345–352. [Google Scholar]

- Djurdjevic, M.B. Application of thermal analysis in ferrous and nonferrous foundries. Met. Mater. Eng. 2021, 27, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrecque, C.; Gagné, M. Interpretation of Cooling Curves of Cast Irons: A Literature Review. AFS Trans. 1998, 72, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, G.; Larranaga, P.; Sertucha, J.; Suarez, R.; Stefanescu, D.M. Gray cast iron with high austenite-to-eutectic ratio, part 1—calculation and experimental evaluation of the fraction of primary austenite in cast iron. Trans. Am. Foundry Soc. 2012, 120, 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, S.; Popelar, P. Thermal Analysis and Process Control for Compacted Graphite Iron and Ductile Iron. In Proceedings of the 2013 Keith Millis Symposium on Ductile Iron, Nashville, TN, USA, 15–17 October 2013; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.