Effect of Single-Pass DSR and Post-Annealing on the Static Recrystallization and Formability of Mg-Based Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Preparation

2.2. Rolling

2.3. Post-Annealing

2.4. Microstructural Characterization

2.5. Mechanical Testing

3. Results

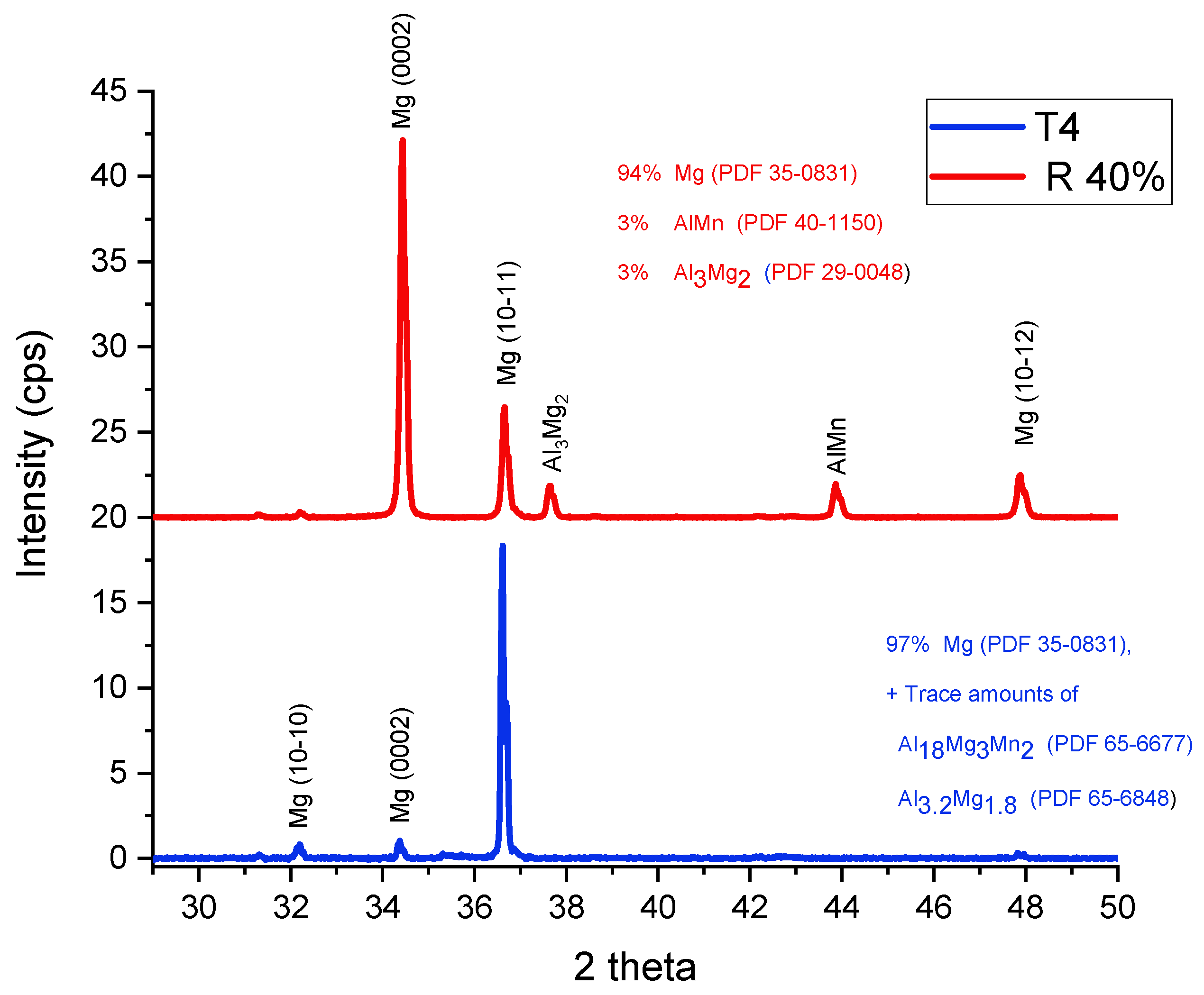

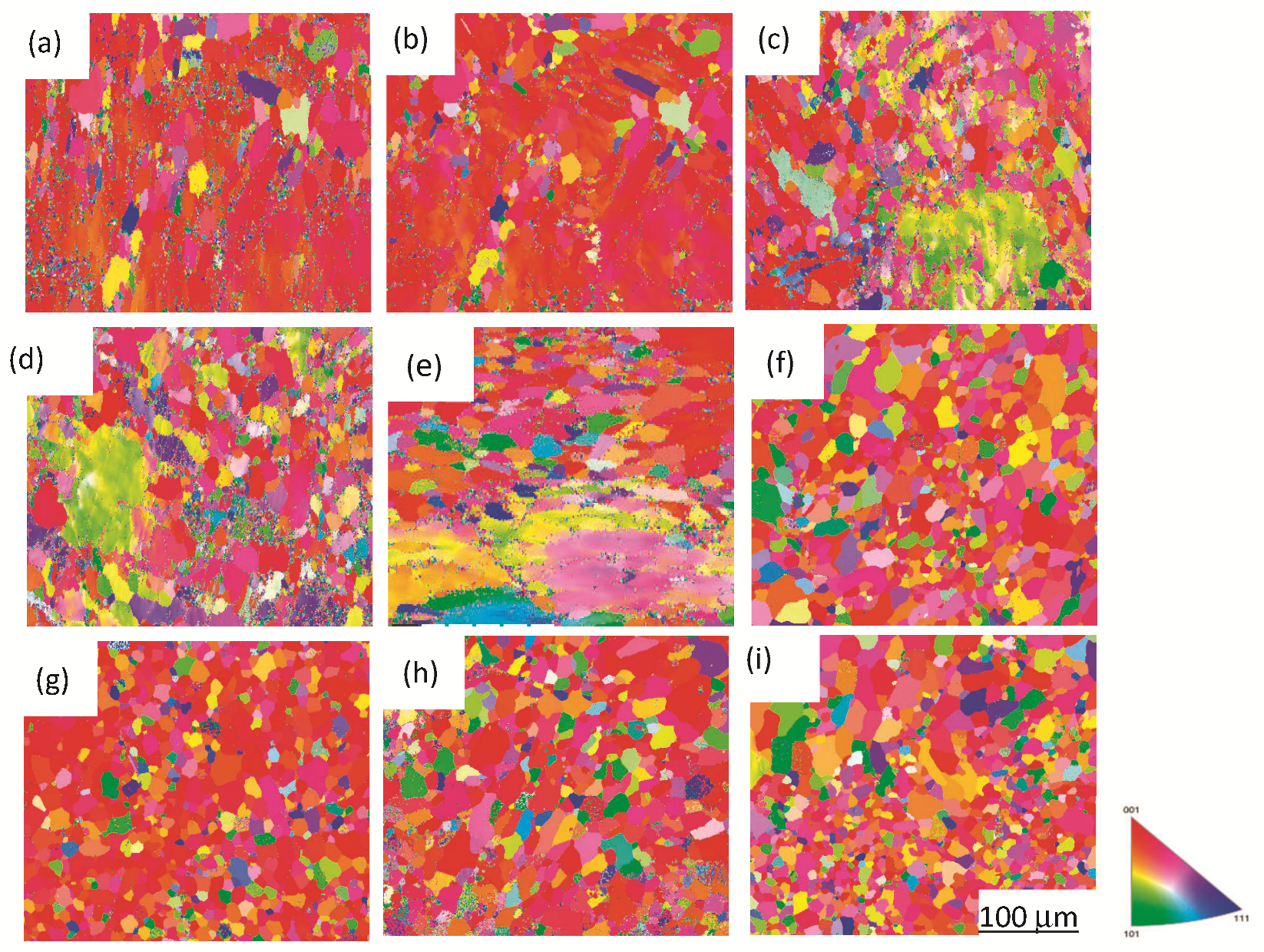

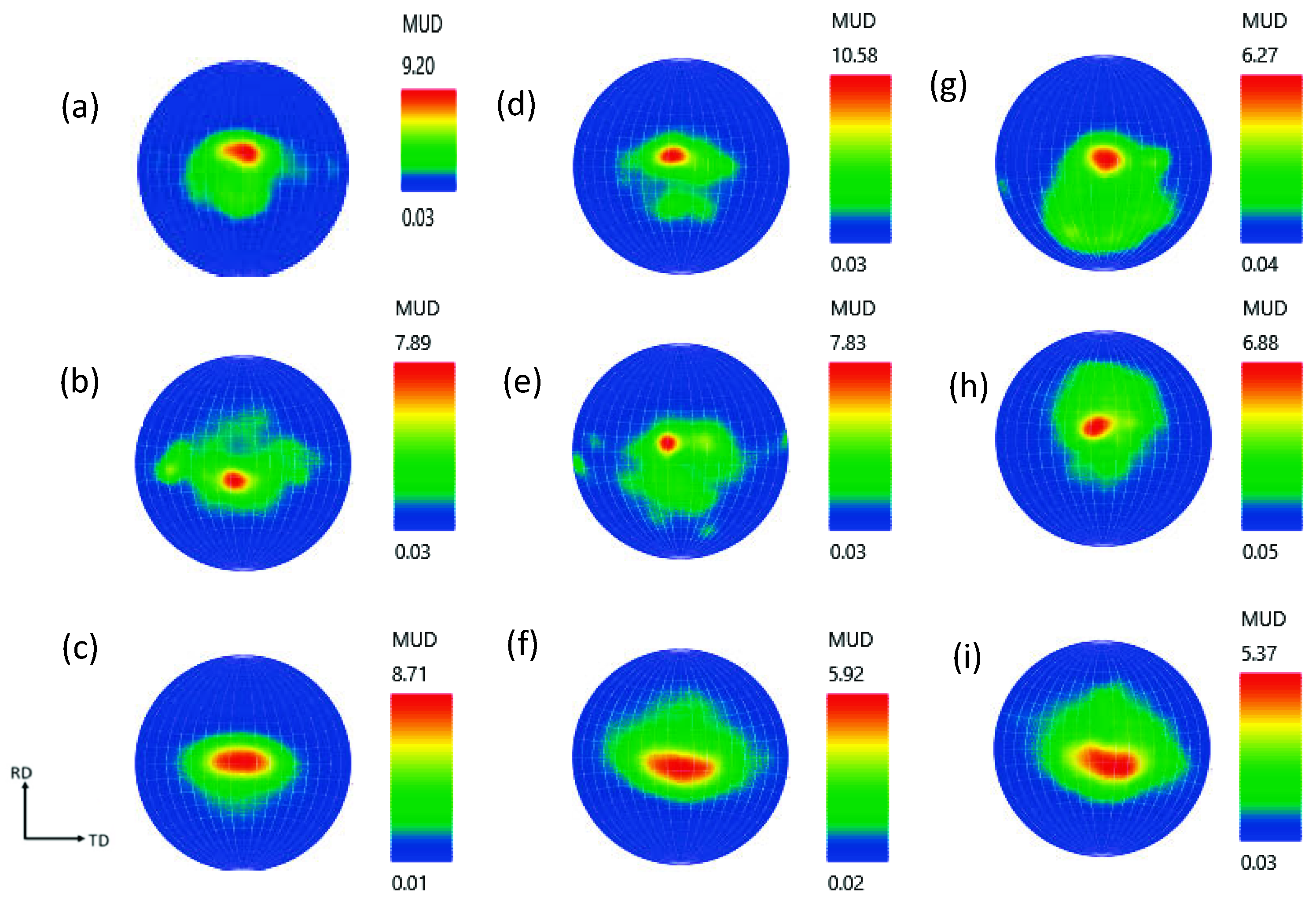

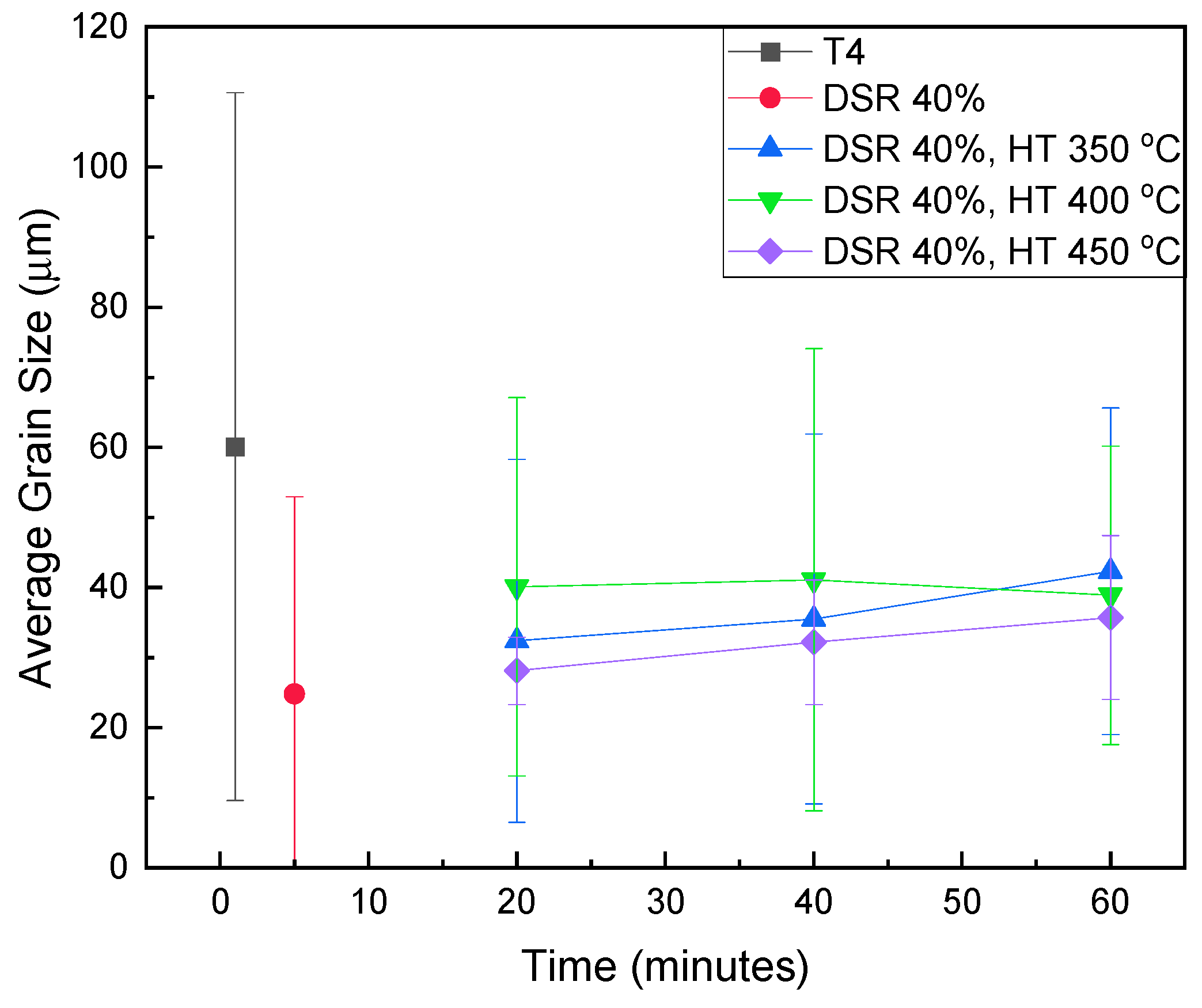

3.1. Microstructure of the Alloys

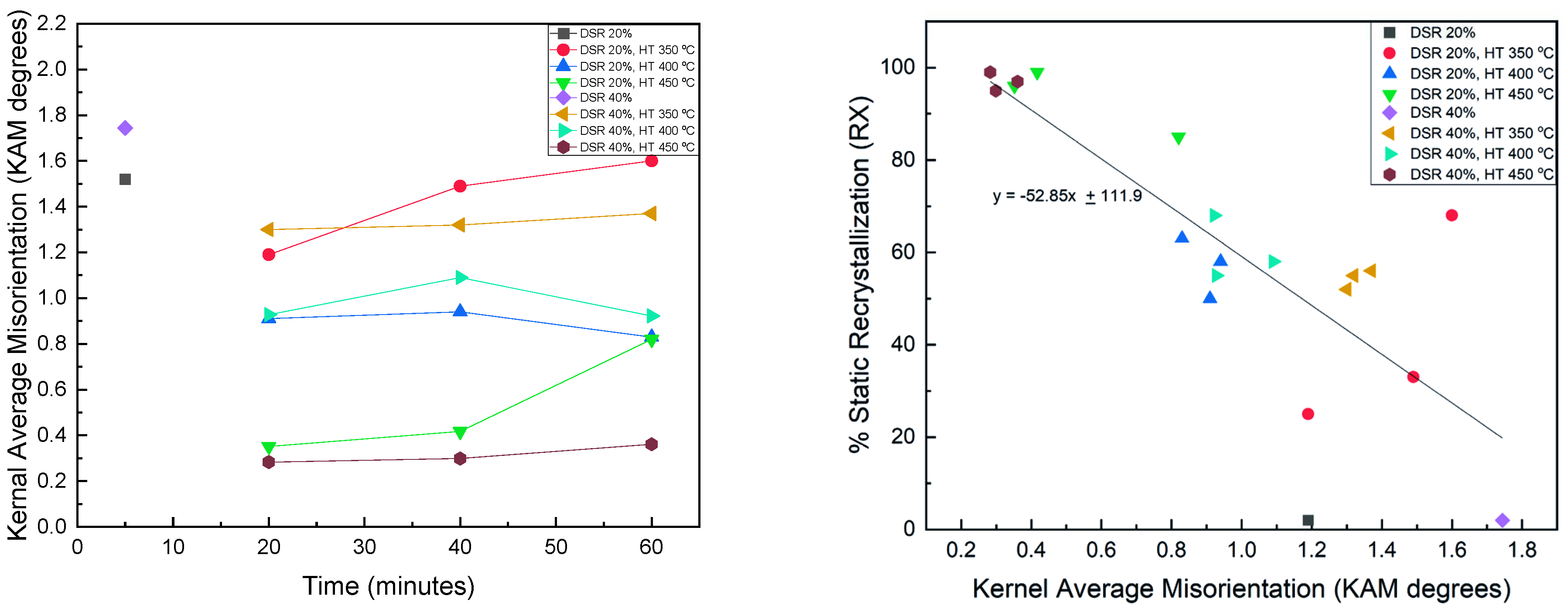

3.1.1. Microstructure Evolution of DSR Samples

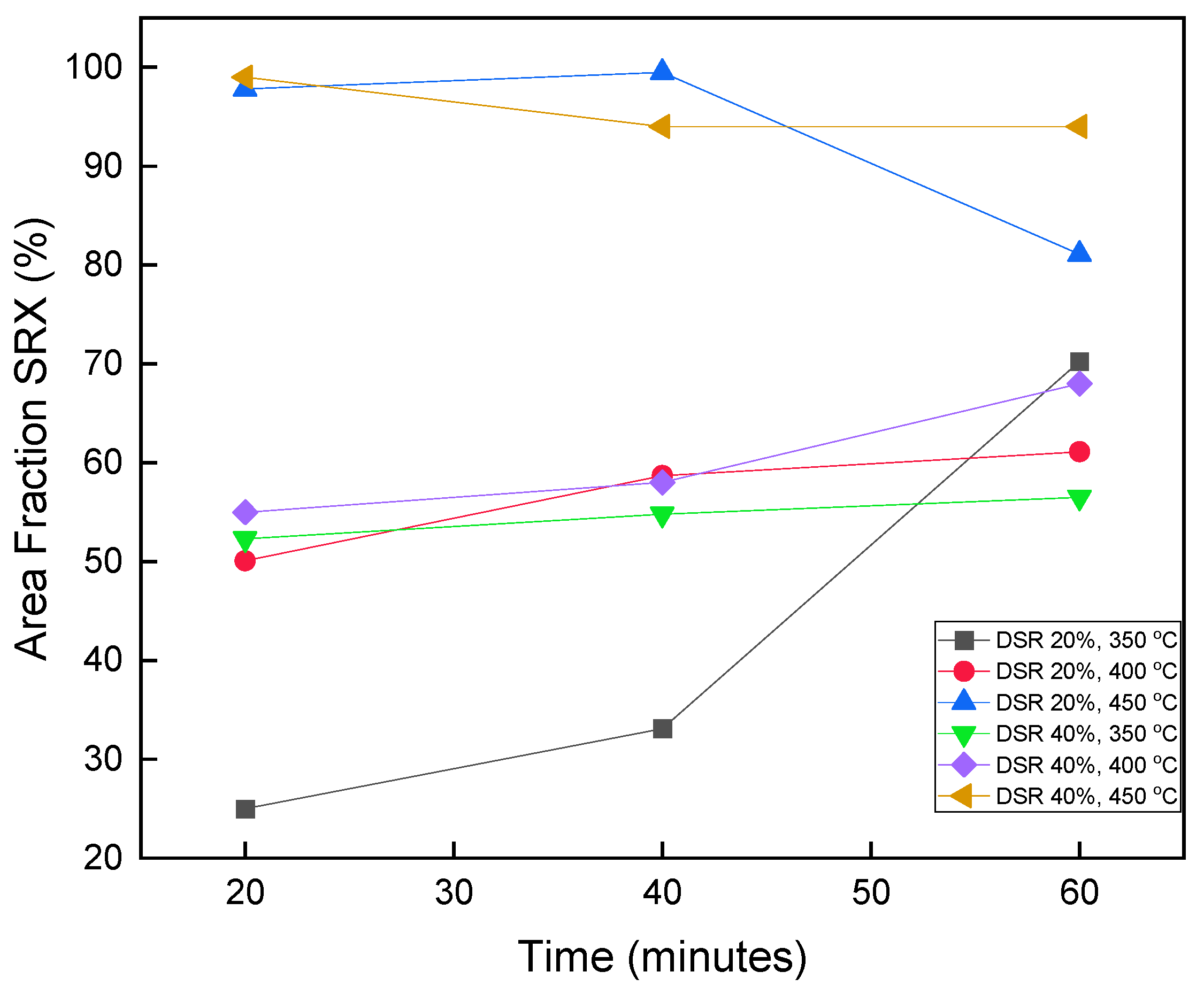

3.1.2. Microstructure Evolution of Post-Annealed Samples

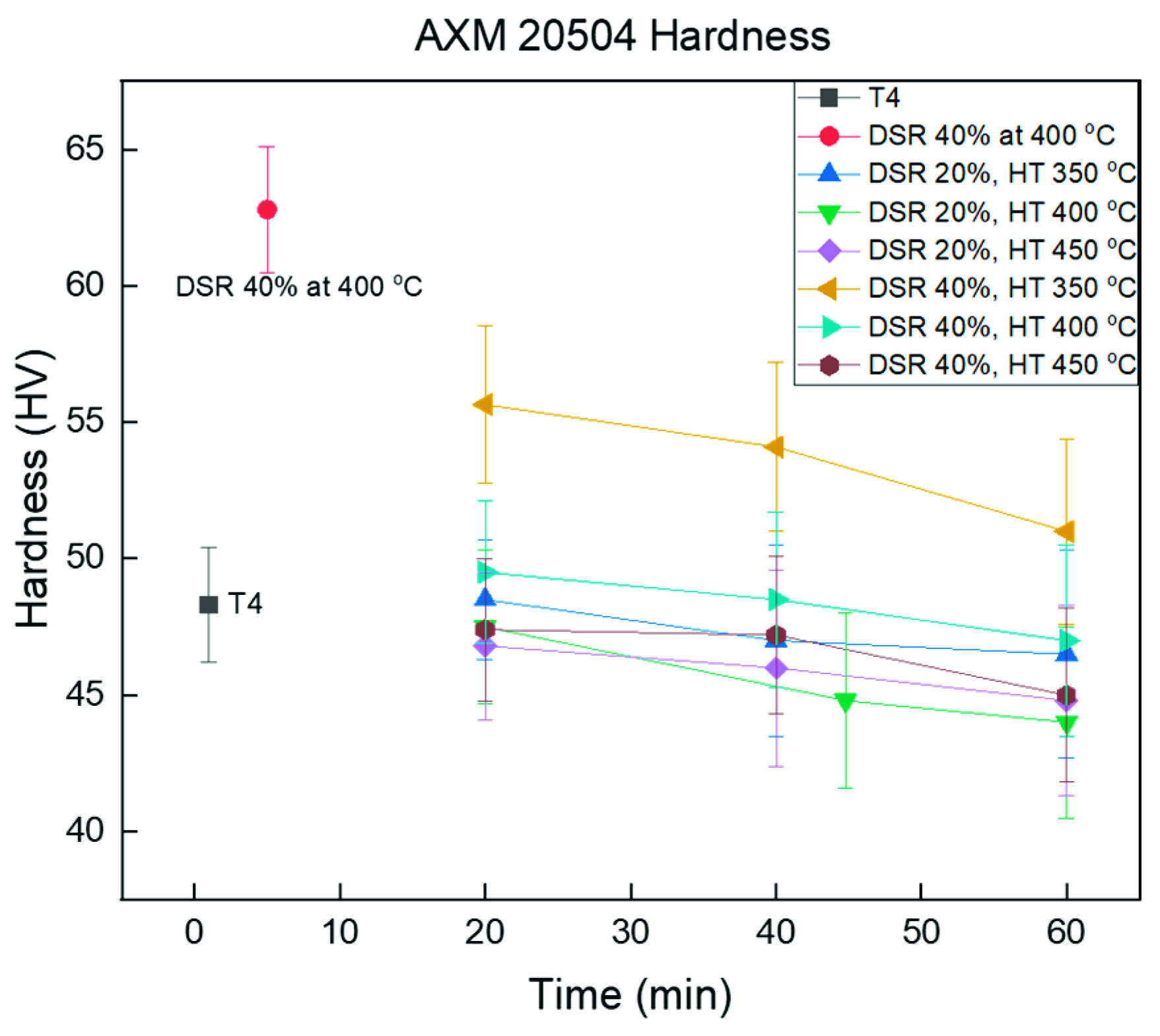

3.2. Mechanical Properties

3.2.1. Relationship of Hardness and Post-Annealing Temperature/Duration

3.2.2. Tensile Behavior of Post-Annealed Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stoudt, M.R. Magnesium: Applications and Advanced Processing in the Automotive Industry. JOM 2008, 60, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, P.G. The Crystallography and Deformation Modes of Hexagonal Close-Packed Metals. Metall. Rev. 1967, 118, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, J.; Kobayashi, T.; Mukai, T.; Watanabe, H.; Suzuki, M.; Maruyama, K.; Higashi, K. The Activity of Non-Basal Slip Systems and Dynamic Recovery at Room Temperature in Fine-Grained AZ31b Magnesium Alloys. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 2055–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ion, S.E.; Humphreys, F.J.; White, S.H. Dynamic Recrystallisation and the Development of Microstructure during the High Temperature Deformation of Magnesium. Acta Metall. 1982, 30, 1909–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Prado, M.T.; del Valle, J.A.; Contreras, J.M.; Ruano, O.A. Microstructural evolution during large strain hot rolling of an AM60 Mg alloy. Scr. Mater. 2004, 50, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle, J.A.; Ruano, O.A. Influence of texture on dynamic recrystallization and deformation mechanisms in rolled or ECAPed AZ31 magnesium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 487, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hua, L.; Sun, Y. Deformation Behavior and Dynamic Recrystallization of AZ61 Magnesium Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 580, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, C.; Xu, Z.; Sankar, J. Optimization of Mechanical Properties in Magnesium-Zinc Alloys. In Proceedings of the TMS 2021, Virtual, 15–18 March 2021; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, C.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yarmolenko, S.; Sankar, J. Comparison of Single-Pass Differential Speed Rolling (DSR) and Conventional Rolling (CR) on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Mg5Zn. Curr. Mater. Sci. Former. Recent Pat. Mater. Sci. 2023, 16, 431–442. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, J.; Poole, W.J.; Sinclair, C.W. Reducing the Tension-Compression Yield Asymmetry in a Mg-8Al-0.5Zn Alloy via Precipitation. Scr. Mater. 2010, 62, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, P.; Wang, L.-N.; Meng, L.; Cui, F. Orientational Analysis of Static Recrystallization at Compression Twins in a Magnesium Alloy AZ31. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 517, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S. Deformation and Its Effect on Recrystallization in Magnesium Alloy AZ31. Master’s Thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sandlöbes, S.; Friák, M.; Zaefferer, S.; Dick, A.; Yi, S.; Letzig, D.; Pei, Z.; Zhu, L.-F.; Neugebauer, J.; Raabe, D. The Relation Between Ductility and Stacking Fault Energies in Mg and Mg-Y Alloys. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 3011–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, N. The Effect of Rare Earth Elements on the Behavior of Magnesium-Based Alloys: Part 2—Recrystallization and Texture Development. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 565, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, H.; Ito, M.; Yang, X.; Jonas, J.J. Mechanisms of Grain Refinement in Mg-6Al-1Zn Alloy During Hot Deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 538, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, A.; Mishra, R.K.; Doherty, R.D.; Kalidindi, S.R. Influence of Deformation Twinning on Static Annealing of AZ31 Mg Alloy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 5966–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.R. Twinning and the Ductility of Magnesium Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 464, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J. The Deformation Behaviour of a Mg-8Al-0.5Zn Alloy. Ph.D. Thesis, Materials Engineering, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaseem, M.; Chung, B.K.; Yang, H.W.; Hamad, K.; Ko, Y.G. Effect of deformation temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of AZ31 Mg alloy processed by differential-speed rolling. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015, 31, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, K.; Ko, Y.G. A cross-shear deformation for optimizing the strength and ductility of AZ31 magnesium alloys. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.G.; Hamad, K. Structural features and mechanical properties of AZ31 Mg alloy warm-deformed by differential speed rolling. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 744, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, K.; Ko, Y.G. Continuous differential speed rolling for grain refinement of metals: Processing, microstructure, and properties. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2019, 44, 470–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, C.; Xu, Z.; Fialkova, S.; Rawles, J.; Sankar, J. Influence of Processing Temperature and Strain Rate on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Magnesium Alloys Processed by Single-Pass Differential Speed Rolling. Crystals 2024, 14, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.T.; Zhang, X.D.; Zheng, M.Y.; Qiao, X.G.; Wu, K.; Xu, C.; Kamado, S. Effect of Ca/Al ratio on microstructures and mechanical properties of Mg-Al-Ca-Mn Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Chen, S.-L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, K.; Yang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Schmid-Fetzer, R.; Oates, W. PANDAT software with Pan-Engine, Pan-Optimizer and Pan-Precipitation for multi-component phase diagram calculation and materials property simulation. Calphad 2009, 33, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, C. Effect of Differential Speed Rolling on the Dynamic Recrystallization of Lightweight Magnesium Alloys Unver Different Temperatures and Strain Rates. Ph.D. Thesis, North Carolina A&T State University, Greensboro, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- E8/E8M; Standard Testing Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Yarmolenko, S.; Kecskes, L.; Sankar, J. Evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-6Al alloy processed by differential speed rolling upon post-annealing treatment. Metals 2021, 11, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wei, L.; Huang, G.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Q.; Wu, P. Understanding the mechanisms of texture evolution in an Mg-2Zn-1Ca alloy during cold rolling and annealing. Int. J. Plast. 2022, 158, 103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollomon, J.H. Tensile Deformation. AIME 1945, 162, 268–290. [Google Scholar]

- Callister, W.D., Jr. Fundamentals of Materials Science and Engineering, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Kalpakjian, S. Manufacturing Engineering and Technology, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education South Asia Pte: Singapore, 2014; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Roll Formed Aluminum Alloy Components, ASM Handbook, 10th ed.; Handbook Committee; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2005; p. 482.

- Rollett, A.D. Plastic Deformation of Single Crystals. In Texture, Microstructure & Anisotropy Course Notes; Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, E.; Boas, W. Kristallplastizitat: Mit Besonderer Berucksightigung der Metalle, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1935; ISBN 978-3662342619. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Hadadzadeh, A.; Mokdad, F.; Wells, M.A.; Chen, D.L. A new grain orientation approach to analyze the dynamic recrystallization behavior of a cast-homogenized Mg-Zn-Zr alloy using electron backscattered diffraction. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 709, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hale, C.; Xu, Z.; Dhar, P.; Fialkova, S.; Sankar, J. Effect of Single-Pass DSR and Post-Annealing on the Static Recrystallization and Formability of Mg-Based Alloys. Metals 2026, 16, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010055

Hale C, Xu Z, Dhar P, Fialkova S, Sankar J. Effect of Single-Pass DSR and Post-Annealing on the Static Recrystallization and Formability of Mg-Based Alloys. Metals. 2026; 16(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleHale, Christopher, Zhigang Xu, Prithu Dhar, Svitlana Fialkova, and Jagannathan Sankar. 2026. "Effect of Single-Pass DSR and Post-Annealing on the Static Recrystallization and Formability of Mg-Based Alloys" Metals 16, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010055

APA StyleHale, C., Xu, Z., Dhar, P., Fialkova, S., & Sankar, J. (2026). Effect of Single-Pass DSR and Post-Annealing on the Static Recrystallization and Formability of Mg-Based Alloys. Metals, 16(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010055