Abstract

This study investigates the presence and distribution of second phases in continuous rheo-extrusion (CRE)-processed Al-La-Ti-B grain refiners and their effect on refining A356 Al-Si alloy. Thermodynamic calculations and microstructural characterization revealed that the main second phases include α-Al, TiAl3, TiB2, Al11La3, LaB6, and Ti2AL20La, with their types evolving with varying Ti/La ratios. The CRE process effectively refined and homogenized these phases. Among the tested refiners, the addition of 0.2 wt.% Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B showed the most effective refinement for A356 alloy, achieving the smallest average α-Al grain size of 221 μm and secondary dendrite arm spacing (SDAS) of 24.62 μm. This optimal refinement corresponded to superior mechanical properties: a tensile strength of 164.52 MPa and elongation of 9.0% in the as-cast state, which were further improved to be 261.13 MPa after T6 heat treatment with elongation of 5.5%. The enhancement is attributed to La’s dual role in modifying the morphology and distribution of TiB2 and TiAl3 phases and acting as a surface-active element to reduce nucleation work, thereby promoting heterogeneous nucleation. This work demonstrates that the CRE process is an effective route to fabricate high-performance La-bearing refiners with engineered microstructures and reveals that optimizing the Ti/La ratio is critical for maximizing grain refinement and mechanical performance in Al-Si alloys.

1. Introduction

Aluminum alloys, particularly Al-Si-based systems such as A356, are widely employed in aerospace, automotive, and rail transit industries due to their favorable strength-to-weight ratio, castability, and corrosion resistance [1,2,3,4]. However, the presence of casting defects—including porosity, shrinkage cavities, and hot tearing—often limits their application in high-performance components. Grain refinement is recognized as one of the most effective approaches to mitigate these defects, promoting a fine and equiaxed microstructure that enhances both mechanical properties and process reliability [5].

Commercial Al-Ti-B master alloys (e.g., Al-5Ti-1B) are commonly used as grain refiners for aluminum alloys [6]. Nevertheless, their efficiency is severely compromised in hypoeutectic Al-Si alloys due to the well-documented “Si poisoning” effect. Silicon promotes the formation of silicide layers (e.g., Ti(Al1−xSix)3) on potent nucleants such as TiB2 and TiAl3, thereby poisoning their nucleation sites and leading to rapid fading of refinement effectiveness [7,8]. To address this issue, researchers have turned to rare-earth (RE) element-bearing refiners. Wu et al. [9] added La to an Al-7Si alloy, which improved the alloy’s microstructure and mechanical properties, providing a basis for the rare-earth modification of Al-Si alloys. Ding et al. [10] added a combination of Y and an Al-Ti-B master alloy to 6063 Al-Si alloy. The Y existed in the forms of AlTiY and Al3Y, refining the alloy grains from 482 μm to 98 μm while simultaneously reducing the size of Mg2Si and optimizing the Fe-rich phases. This resulted in a 75% increase in the alloy’s elongation while maintaining ductile fracture. Luo et al. [11] added La-B-Sr to an Al-10Si alloy. La, by forming LaB6, released the Sr that was consumed by B, achieving simultaneous grain refinement of α-Al (to 218 μm) and modification of the Si phase (presenting a fibrous morphology with an average length of 1.8 μm). This resolved the Sr-B poisoning issue, resulting in an alloy tensile strength of 203.1 MPa and an elongation of 5.6%. Liu et al. [12] utilized remelted chips to produce an Al-5Ti-1B-1Ce refiner. Ce promoted the transformation of TiAl3 to Ti2AL20Ce, suppressing agglomeration. This refined pure aluminum grains from 3000 μm to 185.2 μm, with no significant grain growth for up to 60 min, achieving both chip recycling and highly efficient refinement. Meng et al. [13] used Ce to modify an Al-Ti-B refiner in a 6111 Al-Si alloy. Ce exhibited the most negative adsorption energy towards TiB2, refining the TiB2 particles (size reduced by 39.4%) and forming a Ti2AL20Ce protective layer that inhibited Al3Ti agglomeration. The refinement effect showed no significant fading within 60 min, increasing the alloy’s tensile strength by 33 MPa and elongation by 29.3%. Qiu et al. [14] applied Ce + Yb composite modification to a TiB2/Al-Si-Mg-Cu-Cr composite, optimizing the microstructure and enhancing the mechanical properties, thereby expanding the applications of rare earths in Al-Si matrix composites. Xia et al. [15] applied an Al-5Ti-1B-La master alloy to an A356 Al-Si alloy, significantly refining the grains and improving the mechanical properties, further validating the refinement effectiveness of La. The introduction of RE elements into the Al-Ti-B system is expected to mitigate the Si poisoning effect and develop a more robust refiner for Al-Si alloys.

Despite these promising aspects, several challenges remain unresolved in the development of RE-bearing refiners. These include the precise control over the type, size, and distribution of second phases (e.g., TiB2, TiAl3, and various RE-containing intermetallics like Al11La3, LaB6, and Ti2AL20La), which are crucial for the nucleation efficiency. Furthermore, conventional manufacturing processes often lead to coarse and agglomerated second phases, limiting the refinement performance. Therefore, an advanced processing technology is required to achieve a uniform microstructure. CRE is an emerging severe plastic deformation technology known for its ability to produce refined and homogeneous microstructures in alloys. It combines continuous casting and extrusion, facilitating the breakdown of coarse phases and promoting a fine, dispersed distribution of second-phase particles [16]. Applying CRE to fabricate Al-La-Ti-B refiners presents a potential pathway to overcome the microstructural limitations of conventionally produced refiners.

This work presents a novel approach to developing high-performance La-bearing grain refiners for Al-Si alloys by synergistically combining the CRE process with precise Ti/La ratio control. A series of Al-La-Ti-B refiners were fabricated via CRE, and their second-phase distribution, refinement efficacy in A356 alloy, and the mechanism of La’s action were systematically investigated. The CRE process enables an unprecedentedly fine and uniform dispersion of second phases, while the systematic study identifies the critical Ti/La ratio that dictates phase evolution and optimizes refinement performance.

2. Experimental

2.1. Material Preparation

The preparation of the Al-La-Ti-B refiner included 99.7% industrial pure aluminum, Al-10Ti and Al-3B alloys, and Al-30La intermediate alloy. A356 alloy and a hexachloroethane degassing agent were used during the refining experiments. The chemical compositions of industrial pure aluminum are shown in Table 1, and the compositions of A356 alloy are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of industrial pure aluminum (wt.%).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of A356 aluminum alloy (wt.%).

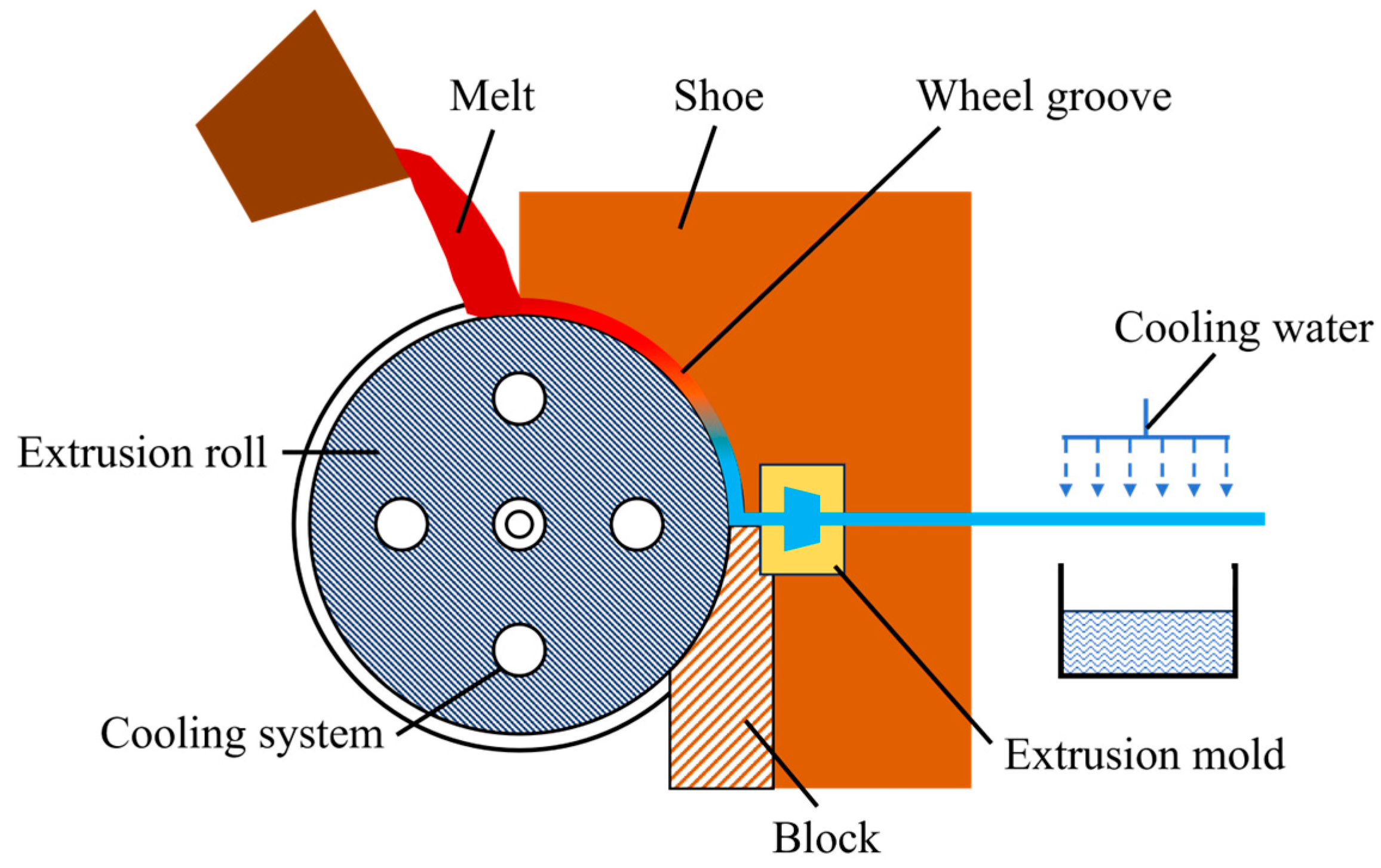

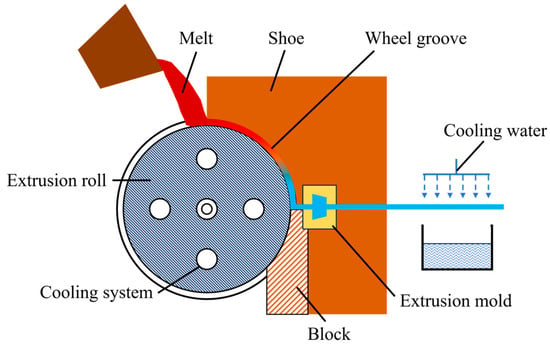

For the preparation of the Al-La-Ti-B refiner, the crucible was placed in the melting furnace, and the temperature was set to 510 °C to prevent the damage of the crucible. Then, the industrial pure aluminum was placed in the crucible, and the furnace temperature was adjusted to around 820 °C. After complete melting, Al-10Ti and Al-3B were added. After the alloy was completely melted into liquid. Al-30La alloy was added into the alloy liquid, and the degassing agent was added to the alloy liquid for degassing and slag removal. Finally, the alloy melt was processed using the CRE equipment shown in Figure 1 to obtain the CRE Al-La-Ti-B refiner.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the CRE process.

For the refinement of the A356 alloy, 1800 g of A356 alloy was prepared for five refining agents (Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B, Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B, Al-1.5La-2.5Ti-1B, Al-1La-3.5Ti-1B, and commercial Al-5Ti-1B). A356 alloy was added to the crucible at a temperature of 760 °C; after the A356 alloy was completely melted, 2 wt.% refiner was added, and stirring was guaranteed to accelerate the reaction. After degassing, the melt was poured into the steel mold for further detections.

2.2. Characterization of the CRE Al-La-Ti-B Refiners and Refined A356 Alloy

The phase stability of Al-La-Ti-B alloys was predicted by thermodynamic calculations using FactSage 8.3 software equipped with the FTlite database [17], under equilibrium conditions and a pressure of 1 atm.

For microstructural characterization, samples were sectioned, ground, polished, and etched with Keller’s reagent (95 mL of H2O, 2.5 mL of HNO3, 1.5 mL of HCl, and 1.0 mL of HF). Optical microscopy (OM, Leica DMi8, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to observe the grain structure of the CRE Al-La-Ti-B refiners and the macro-/microstructure of the refined A356 alloys. The average grain size and SDAS were measured using the linear intercept method on more than 500 grains or dendrite arms per sample with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (IPP 6.0) software. Phase identification was conducted by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Panalytical Empyrean, Almelo, NL) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), with a scanning range of 20° to 90° (2θ), a step size of 0.02°, and a scanning speed of 10°/min. The refiner microstructure and local chemical composition were analyzed using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Zeiss SUPRA 55, Jena, Germany) operated at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a working distance of ~10 mm, equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector (Oxford Instruments plc, Abingdon, UK). EDS point analysis and mapping were performed with a live time of 60 s per acquisition.

Tensile tests of the refined A356 alloys were conducted at room temperature using an electronic universal testing machine (Shimadzu AG-IC 100 kN, Kyoto, Japan) according to the ASTM E8 standard [18]. Cylindrical tensile specimens with a gauge diameter of 5 mm and a gauge length of 25 mm were used. Tests were performed at a constant crosshead speed of 1 mm/min until fracture. The elongation was calculated according to Equation (1). To ensure statistical reliability and demonstrate repeatability, three parallel specimens were tested for each experimental condition. The reported values for all quantitative data (grain size, SDAS, tensile strength, and elongation) represent the mean ± standard deviation.

where, E is the elongation, %; l is the sample length after the tensile test, mm; and l0 is the sample length before the tensile test, mm.

3. Results

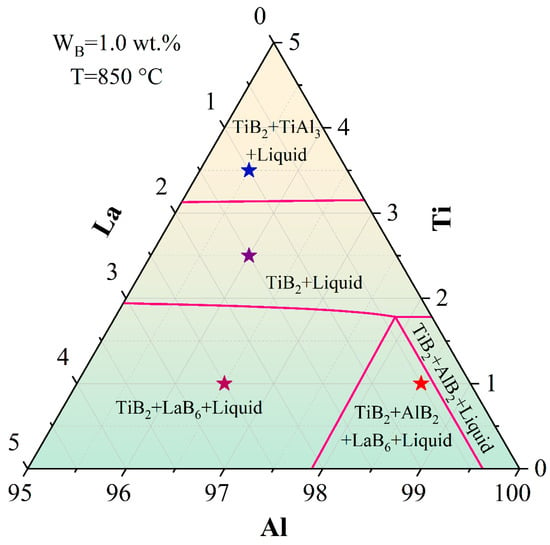

3.1. Thermodynamic Calculations on Al-La-Ti-B Alloys

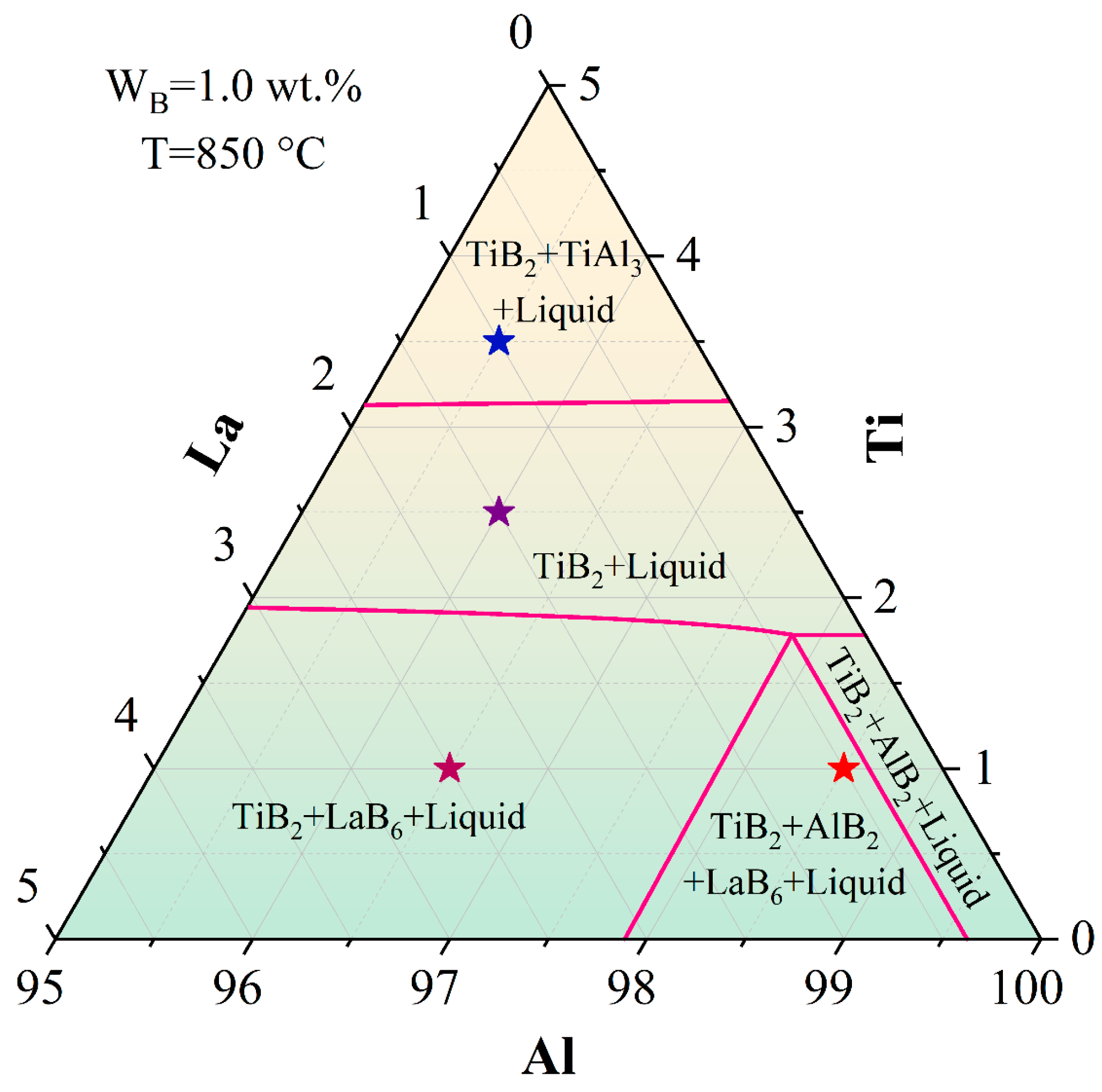

Figure 2 presents the thermodynamic phase diagrams of the investigated Al-La-Ti-B alloys. The diagrams reveal that each composition, with its distinct Ti/La ratio, occupies a different phase region. Consequently, the dominant second phases transit from TiB2 and LaB6 in the low-Ti/high-La alloys to TiAl3 and TiB2 in the high-Ti/low-La alloys. This systematic shift in phase formation suggests a corresponding variation in their grain refinement efficacy for Al-Si alloys, which is explored in the subsequent sections.

Figure 2.

Thermodynamic calculations on Al-La-Ti-B alloys (the star symbols denote the Al-La-Ti-B compositions used in this work).

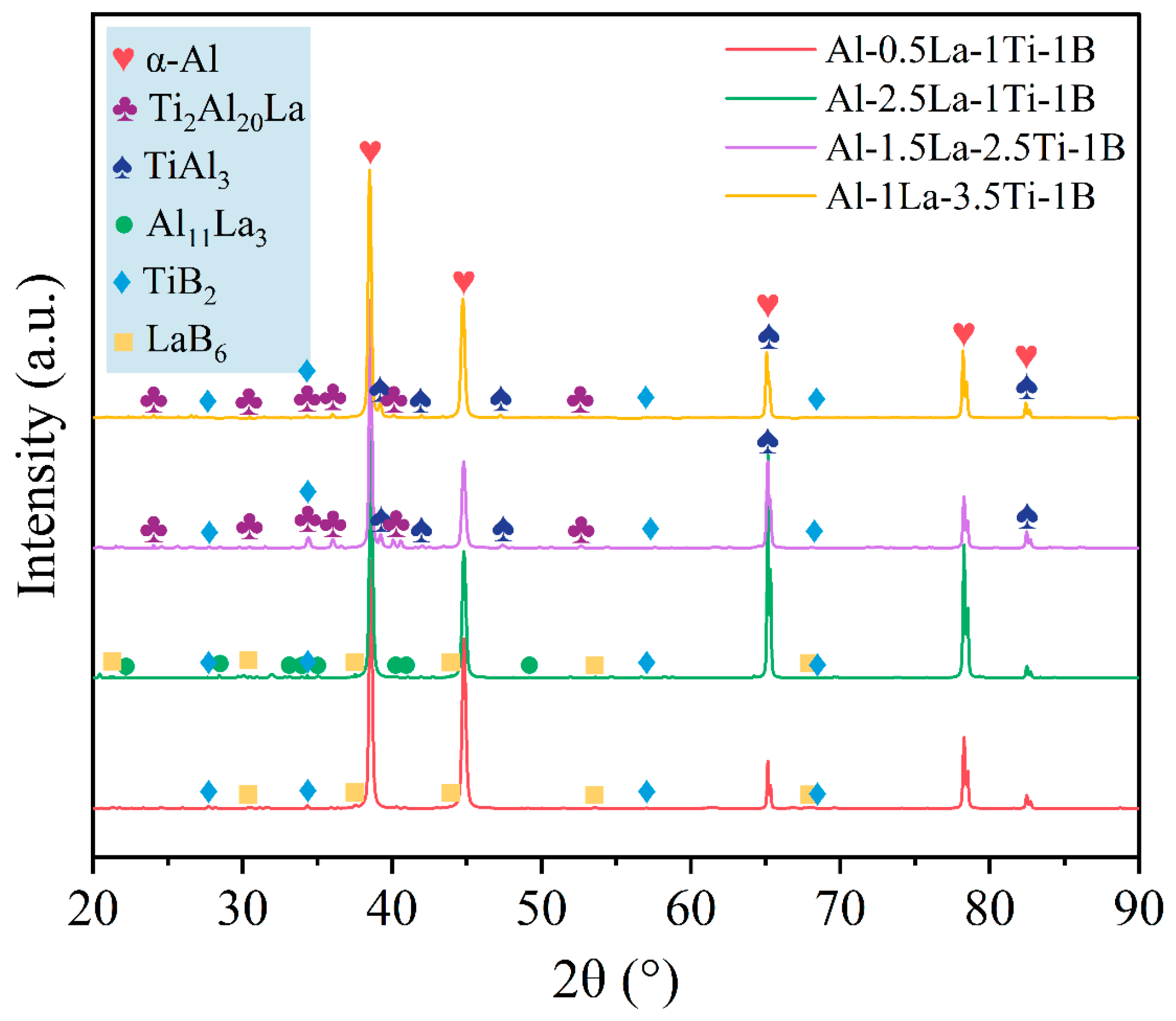

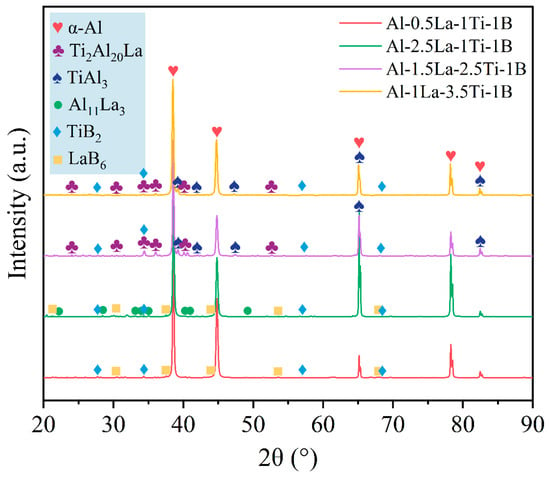

3.2. Phases Analysis of CRE Al-La-Ti-B Refiner

Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of the investigated alloys. Through qualitative analysis, the main second phases of the Al-La-Ti-B refiner include five phases: α-Al, TiAl3, TiB2, Al11La3, LaB6, and Ti2AL20La. The second phases of Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B are TiB2 and LaB6, with no AlB2 phase detected. For Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B, it contains Al11La3, LaB6, and TiB2 phases. Furthermore, the second phases in Al-1.5La-2.5Ti-1B and Al-1La-3.5Ti-1B alloys are the same. The corresponding diffraction peaks can be clearly observed, and the second phases are determined as TiAl3, Ti2AL20La, and TiB2. The presence of Al11La3 and Ti2AL20La phases observed in the XRD results was not predicted by the thermodynamic calculations. This is primarily due to the relatively low thermodynamic stability of these phases in the aluminum melt and the extremely low equilibrium solid solubility of La in the Al matrix. Consequently, they are not readily accounted for in equilibrium calculations and instead precipitate during the non-equilibrium solidification of the alloy.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the investigated alloys.

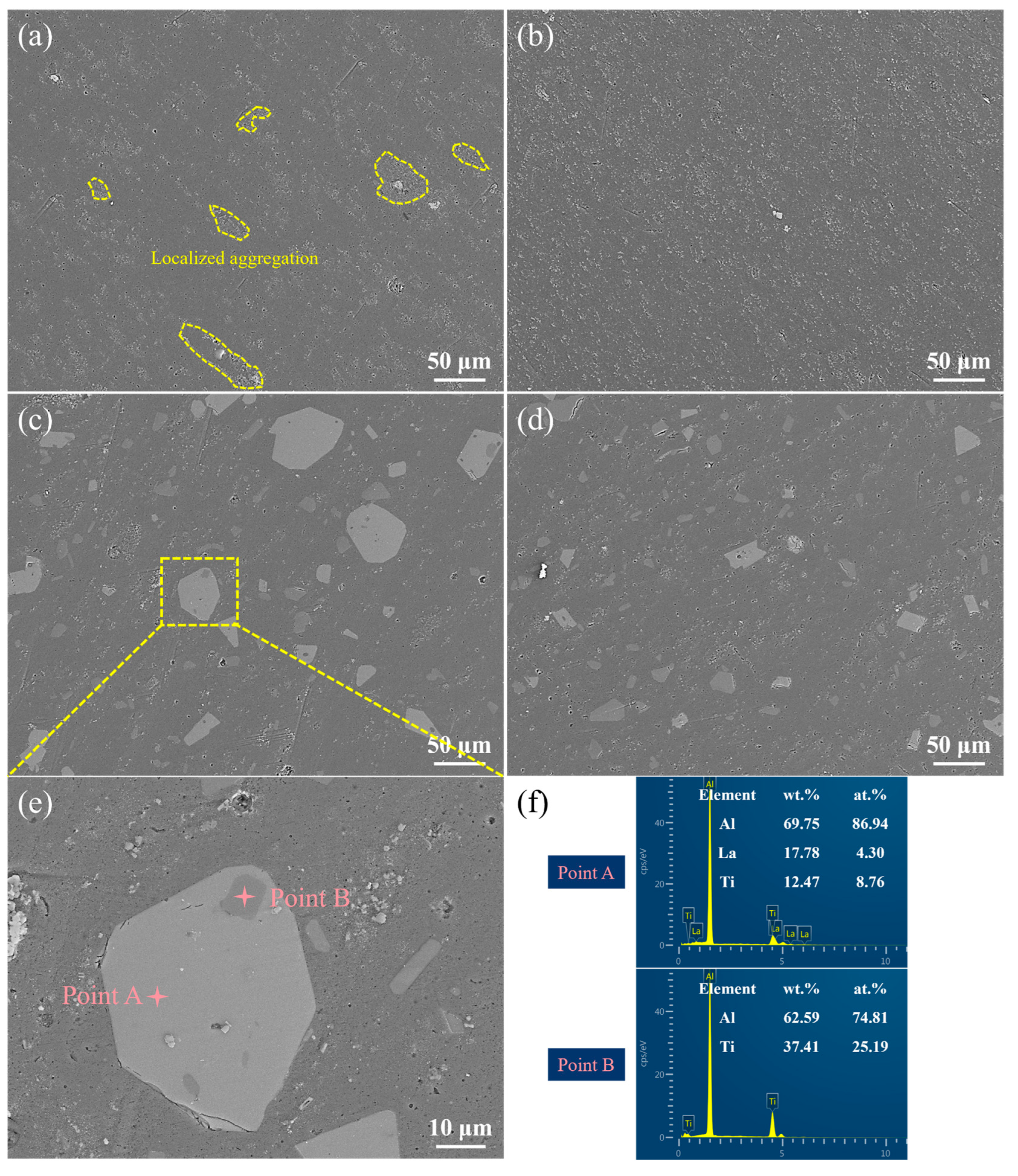

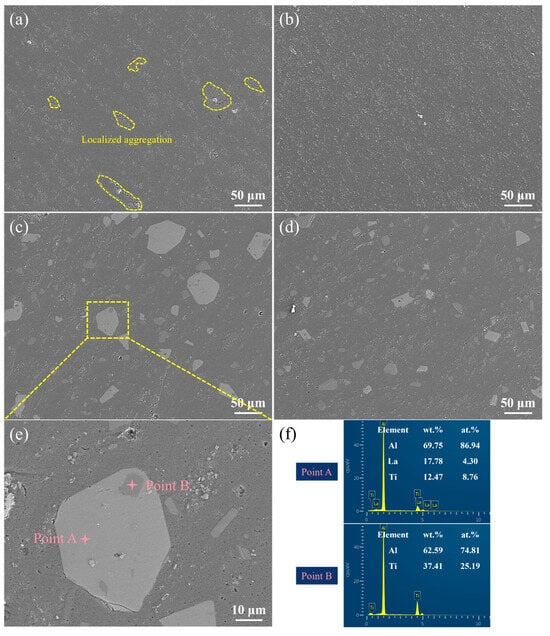

Figure 4 shows the morphology and distribution of the second phases in CRE Al-La-Ti-B alloys. The morphological characteristics and distribution of each phase can be clearly observed. Figure 4a and Figure 4b present the microstructures of the Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B and Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B alloys, respectively. In both alloys, the second phases primarily consist of particulate particles, with no large blocky phases forming. However, the distribution of these particles shows a significant difference. The Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B alloy exhibits a lower number density of particles along with localized aggregation. In contrast, the Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B alloy possesses a higher number density of particles, which distribute in a more dispersed and uniform manner. According to studies by Chen et al. [14,19], adding rare-earth (RE) elements to the Al-Ti-B system can effectively suppress the agglomeration tendency of particles and promote their homogeneous distribution. Therefore, in the present work, the lower La content in the Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B alloy provides insufficient suppression of agglomeration, leading to the observed localized clustering of particles. Figure 4c and Figure 4d show the microstructures of the Al-2.5Ti-1.5La-1B and Al-3.5Ti-1La-1B alloys, respectively. Unlike the previous alloys, these microstructures contain not only particulate phases but also large light grey and dark grey blocky phases. Notably, some of the dark grey phases appear encapsulated within larger bright white blocky phases. Previous research [20,21,22] identifies the light grey blocky phase as the Ti2AL20RE ternary phase and the dark grey one as the TiAl3 phase. Combined with the evidence from Figure 4e,f, we identify the light grey blocky phases in Figure 4c,d as Ti2AL20La and the dark grey phases as TiAl3. The two figures clearly show that with increasing Ti content and decreasing La content, the Ti2AL20La phase in Figure 4d decreases in both size and quantity, while the population of the TiAl3 phase increases correspondingly. The fine and uniform dispersion of second phases observed in all CRE alloys (Figure 4a–d) contrasts sharply with the coarse and segregated structures typically reported in conventionally cast Al-Ti-B-type refiners [23,24]. Notably, the absence of large, needle-like TiAl3 and severely agglomerated TiB2 clusters highlights the microstructural refinement capability of the CRE process.

Figure 4.

Morphology and distribution of the second phases in CRE Al-La-Ti-B alloys: (a) Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B; (b) Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B; (c) Al-2.5Ti-1.5La-1B; (d) Al-3.5Ti-1La-1B; (e) enlarged view of the area in the yellow dashed box in (c); (f) EDS analysis of points A and B in (e).

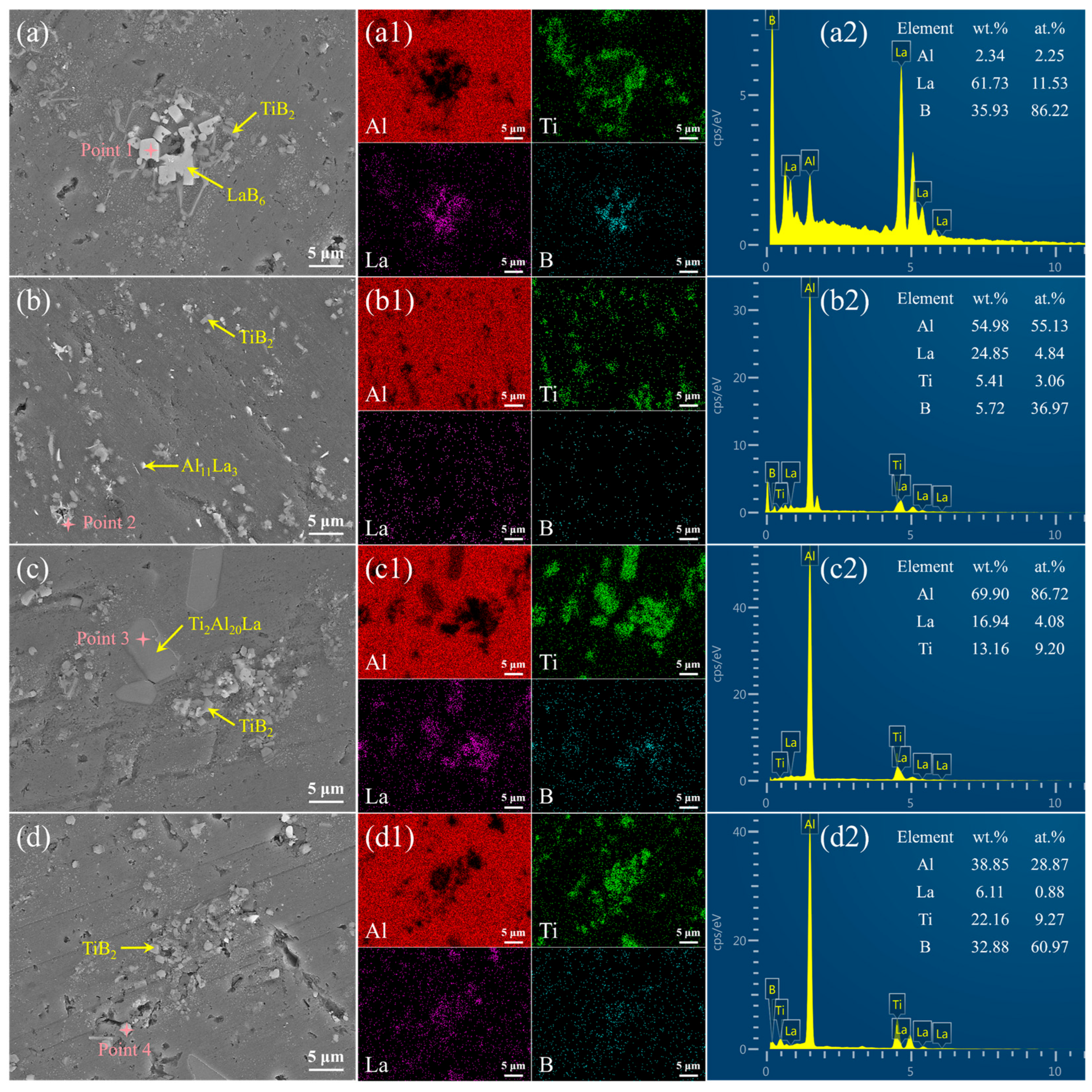

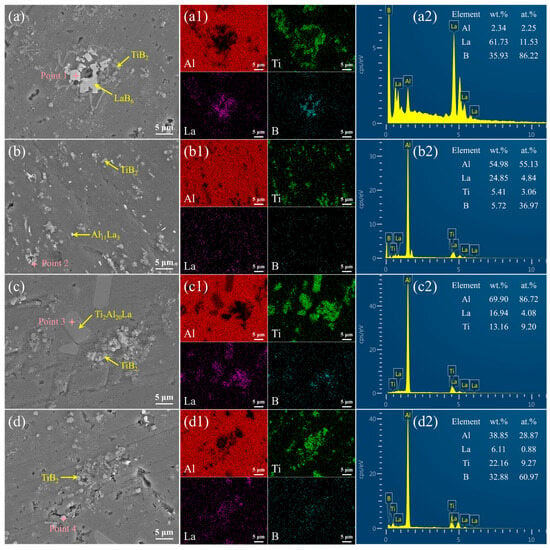

Figure 5 shows the magnification and the corresponding elemental mappings with EDS mappings of Figure 4. Based on the magnification and mappings in Figure 5a, there are three types of elemental compositions at this point 1, namely Al, La, and B. The atomic percentages of La and B are 11.53 at.% and 86.22 at.%, which are close to the stoichiometric ratio of LaB6. Therefore, it can be inferred that the phase at this point is the LaB6 phase. EDS analysis on the bright white flocculent phase at point 2 along the TiB2 edge in Figure 5b reveals the presence of La and Al elements. Combined with the XRD pattern in Figure 3, this phase is identified as Al11La3. In Figure 5c, a gray-black block phase shows enrichment of Ti and La elements (Figure 5(c1)). EDS point analysis at point 3 indicates that the atomic ratio of Al, Ti, and La is approximately 20:2:1 (Figure 5(c2)), suggesting that this block phase is Ti2AL20La. Furthermore, TiB2 particles are observed in Figure 5d. EDS mapping analysis in Figure 5(d1) reveals the enrichment of La within these TiB2 aggregates. This is corroborated by point analysis at location 4, which is approximately detected as 0.88 at.% La (Figure 5(d2)). It should be noted that thermodynamic calculations in Figure 2 predict that neither Al11La3 nor LaB6 should form in the Al-3.5Ti-1La-1B system, and these phases are also absent in the XRD pattern in Figure 3. Therefore, it can be inferred that a small amount of La is either dissolved in or adsorbed onto the surface of TiB2.

Figure 5.

Magnification and the corresponding elemental mappings with EDS mappings of Figure 4: (a,a1,a2) Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B; (b,b1,b2) Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B; (c,c1,c2) Al-2.5Ti-1.5La-1B; (d,d1,d2) Al-3.5Ti-1La-1B.

Thus, combined with Figure 4 and Figure 5, the TiB2 phase is a fine and aggregated particle, the LaB6 phase is bright gray block, Al11La3 is flocculent substance, the TiAl3 phase is a dark gray block or elongated shape, and the Ti2AL20La phase is a bright gray block. Furthermore, with the increasing Ti content from 1.0 to 3.5 wt.%, the big TiAl3 phase is more obvious, combined with the occurrence of the Ti2AL20La phase.

4. Results and Discussion

To explore the refinement effect of Al-La-Ti-B refiners, A356 alloy is used, which has good casting performance but has many disadvantages without refinement. The important indicator for evaluating the refinement of refiners is the average grain size of α-Al combined with the mechanical performance. Therefore, based on the above four La-bearing agents, the microstructure and mechanical properties of refined A356 alloys are studied.

4.1. Macro- and Microstructures of the Refined A356 Alloys

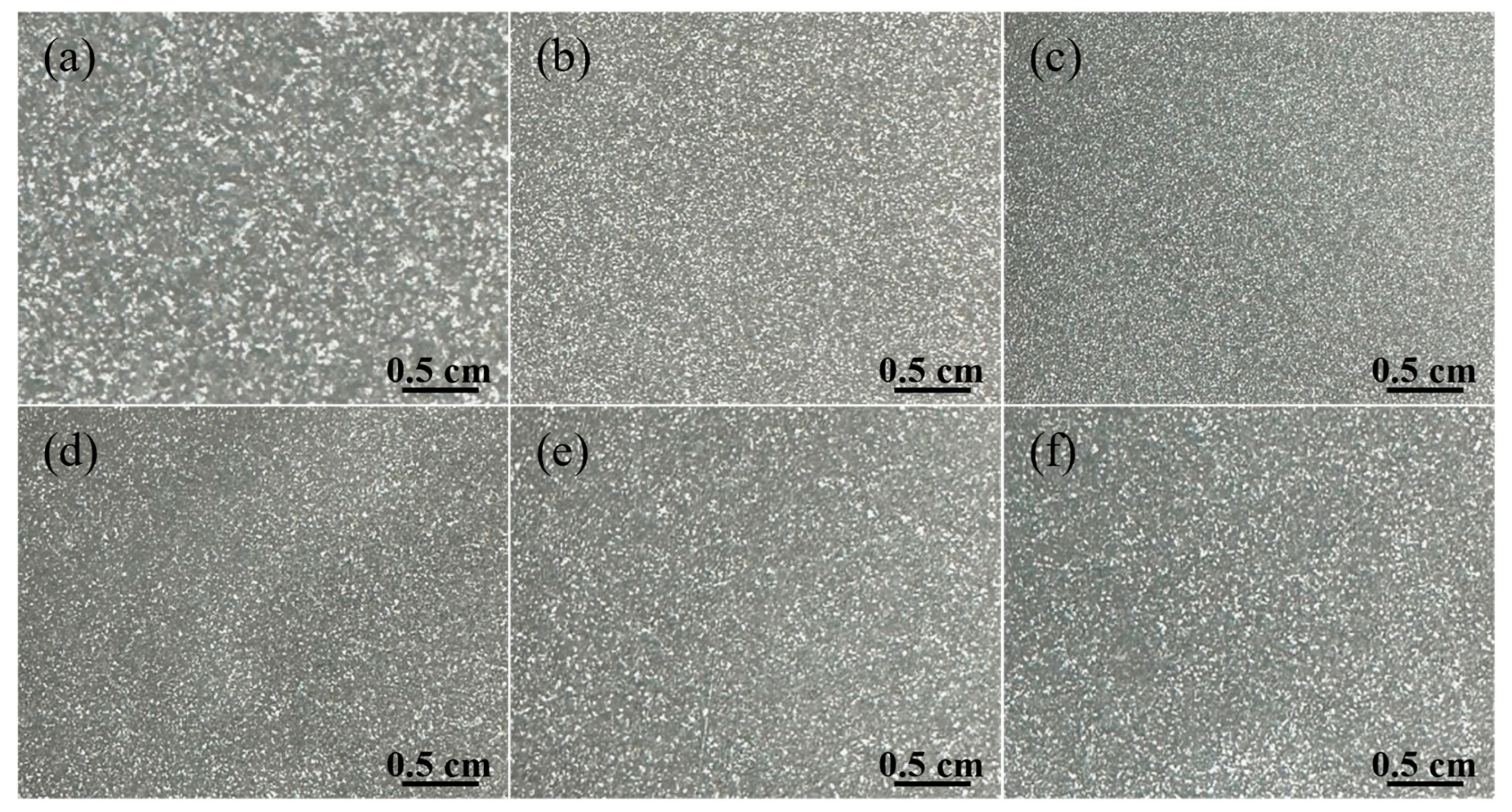

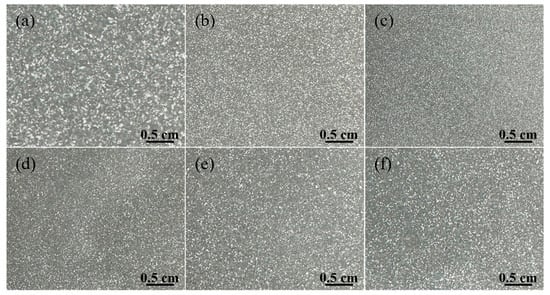

Macrostructures of the refined A356 alloys with different types of Al-La-Ti-B refiners are shown in Figure 6. The refiner addition is 0.2 wt.%. To make a comparison, macrostructures of the A356 alloy without refiners and with commercial Al-5Ti-1B refiner are also presented. Based on Figure 6a–f, there is a significant difference in the macrostructure of the A356 alloys with the absence and addition of refiners, indicating the importance of adding refiners. Comparing Figure 6b–f, the La-bearing refiners provide superior refinement compared to the commercial Al-5Ti-1B, indicating that the rare-earth element La has a promoting effect on the refinement of Al-Ti-B refiner. Furthermore, the grain size in Figure 6c is smaller than that in Figure 6b,d,e, indicating that the Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B refiner offers superior refinement for the A356 alloy.

Figure 6.

Macrostructures of the refined A356 alloys with different types of Al-La-Ti-B refiners: (a) without refiners; (b) Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B; (c) Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B; (d) Al-2.5Ti-1.5La-1B; (e) Al-3.5Ti-1La-1B; (f) Al-5Ti-1B.

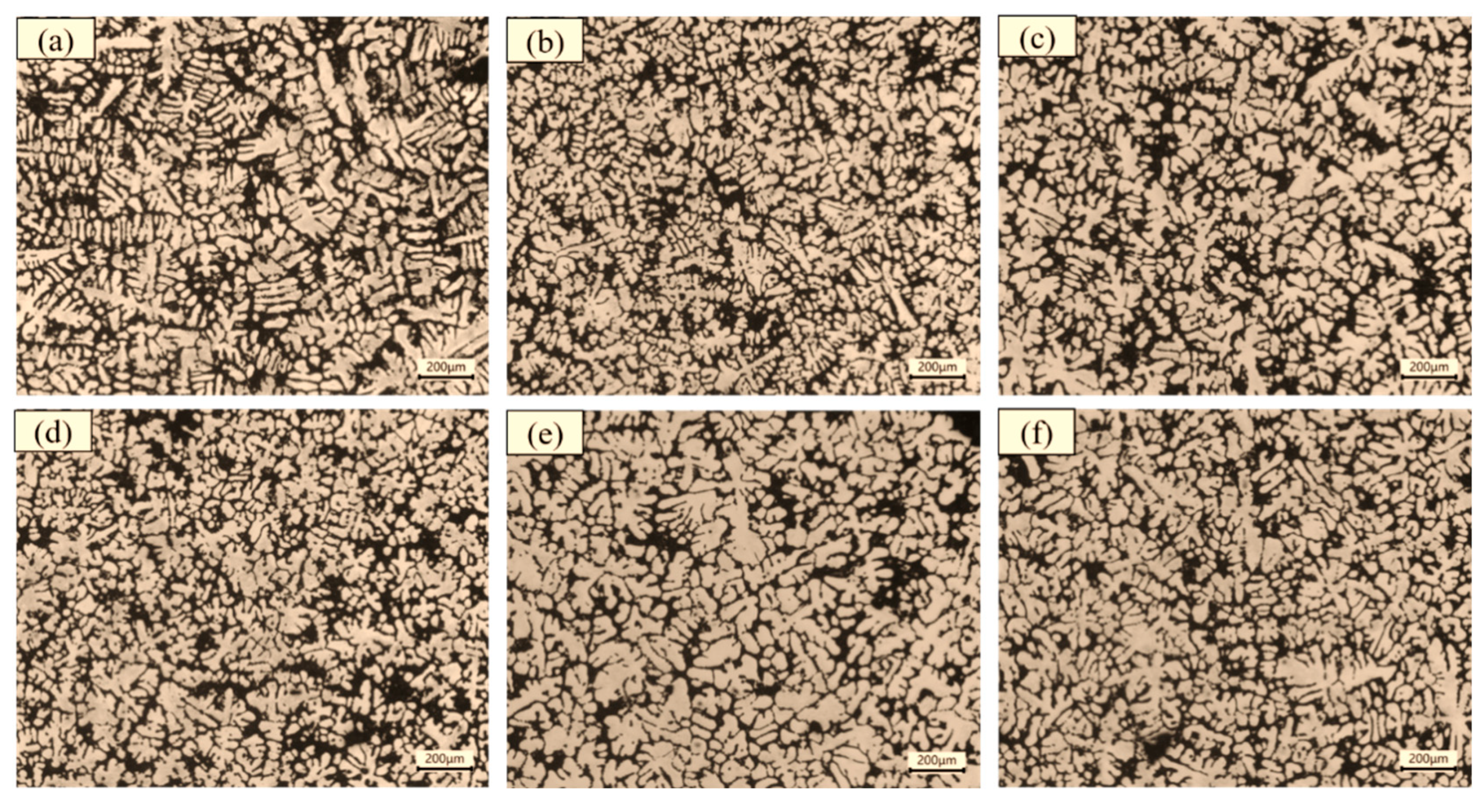

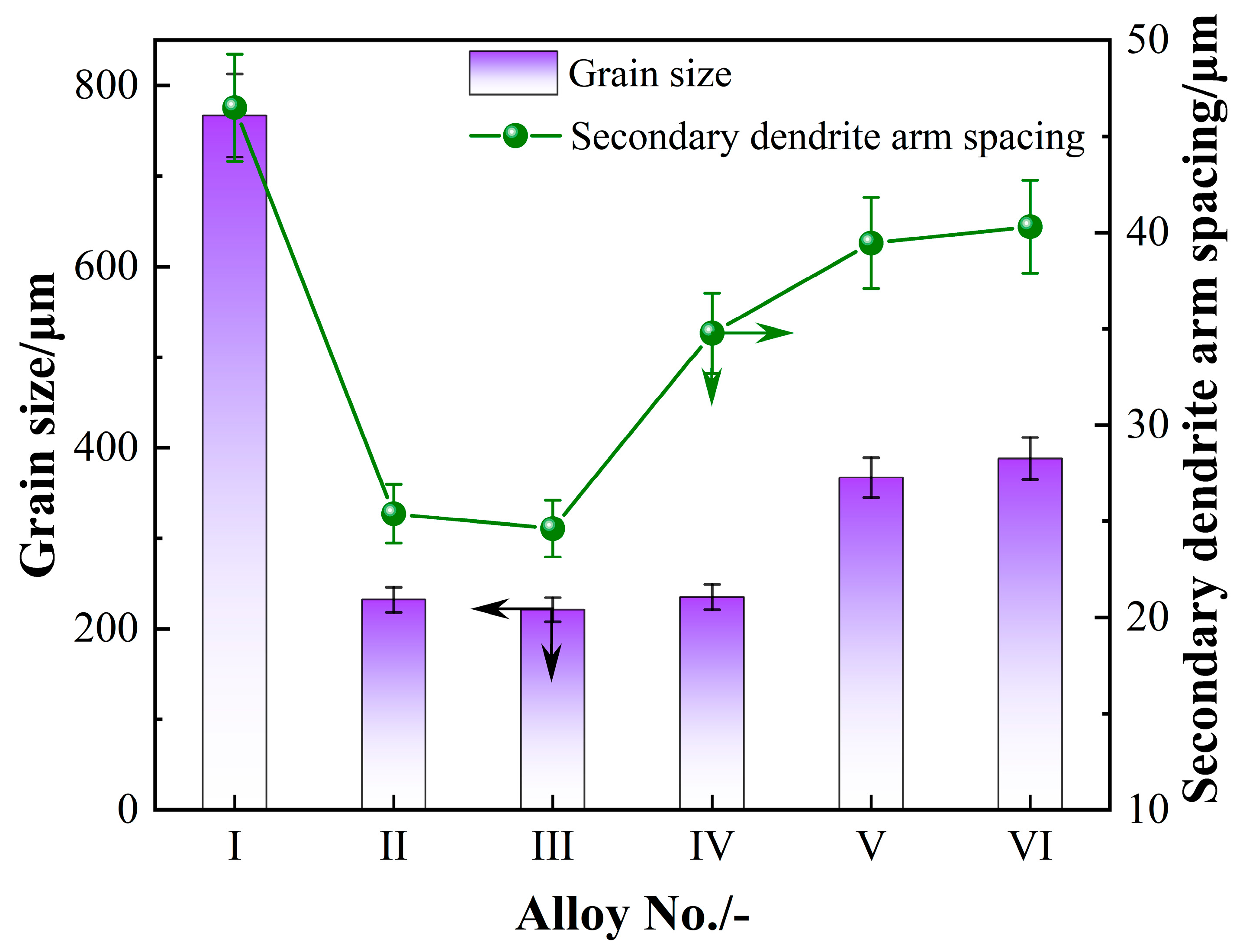

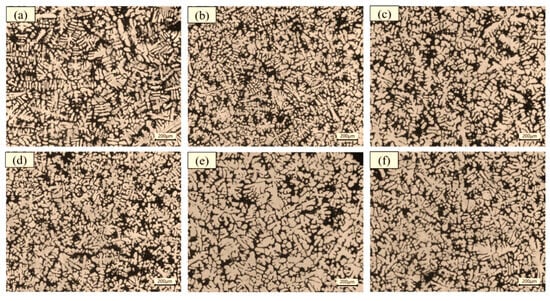

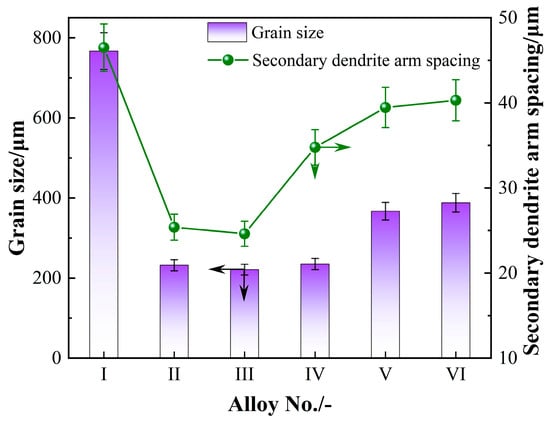

Figure 7 shows the α-Al grains of the refined A356 alloys with different types of Al-La-Ti-B refiners. As shown in Figure 7a, the grain size of A356 alloy without refiners is significantly larger than the other groups of alloys. However, the refinement of the A356 alloys with different types of Al-La-Ti-B refiners is comparable, and the difference in grain size is not significant. After measurement using IPP 6.0 software, the smallest grain size of 221 μm under 0.2 wt.% Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B addition is obtained. Figure 8 and Table 3 show the grain size of the refined A356 alloys with different types of Al-La-Ti-B refiners. With increasing Ti content in the refiner, the refinement of refined A356 alloys is negative, and the grain size of refined A356 alloys is increased. As shown in Figure 7e, at a 0.2 wt.% Al-5Ti-1B addition, the grain size of refined A356 alloy is as large as 388 μm. Furthermore, the secondary dendrite arms’ spacing of refined A356 alloys is calculated and also shown in Figure 8 and Table 3. For the original A356 alloy, the SDAS is 46.49 μm, significantly larger than the other experimental groups. When the La-bearing refiner is added, the SDAS is smaller, and the value of 24.62 μm is obtained under the 0.2 wt.% Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B addition. Thus, the lower grain size and SDAS signify a better mechanical property.

Figure 7.

Microstructures of the refined A356 alloys with different types of Al-La-Ti-B refiners: (a) without refiners; (b) Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B; (c) Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B; (d) Al-2.5Ti-1.5La-1B; (e) Al-3.5Ti-1La-1B; (f) Al-5Ti-1B.

Figure 8.

Tendency of the grain size and SDAS of refined A356 alloy.

Table 3.

Grain sizes and SDASs of refined A356 alloys.

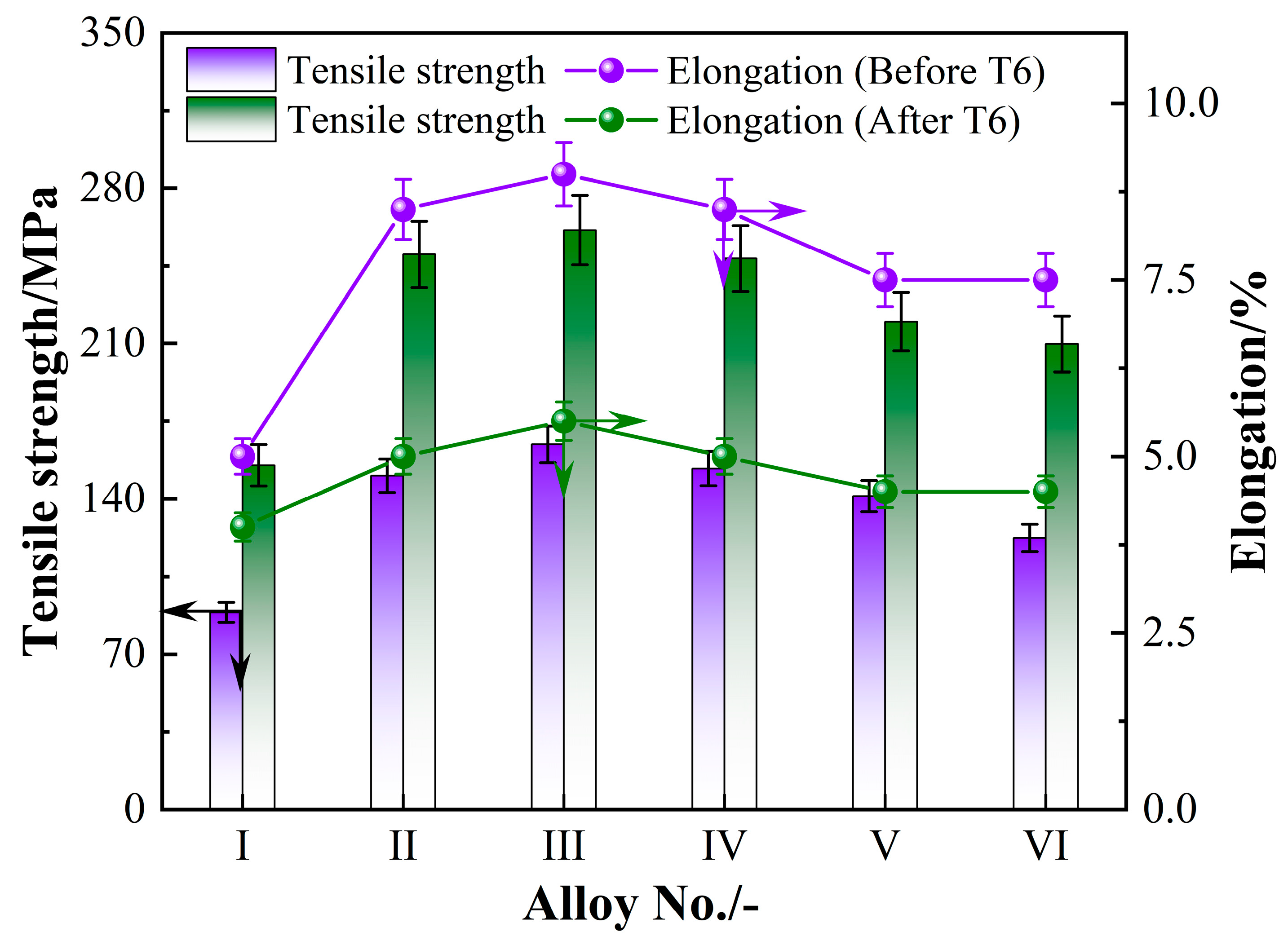

4.2. Mechanical Properties of the Refined A356 Alloys

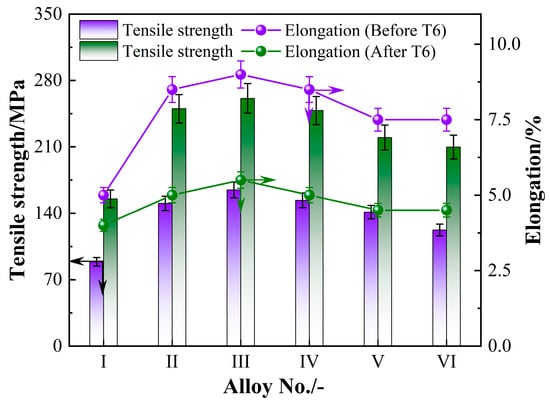

After adding the La-bearing refiners, the tensile strength and elongation of refined A356 alloy were measured. Figure 9 and Table 4 show the mechanical properties of the refined A356 alloys (defined as Alloy Nos. I-VI). Also, the mechanical properties of refined A356 alloys after T6 heat treatment are presented. It can be seen that the tensile strengths and elongation of Alloy No. I and Alloy No. VI are 88.77 MPa and 5%, 122.36 MPa and 7.5%, respectively. The tensile strengths of Alloy Nos. II-V are higher than Alloy Nos. I and VI, indicating the promoting effect of elemental La on the property improvement of A356 alloy. The peak values of both tensile strength and elongation are obtained with Alloy No. III. Before the T6 heat treatment, the tensile strength and elongation of Alloy No. III are 164.52 MPa and 9.0%, respectively.

Figure 9.

Tensile strengths and elongations of refined A356 alloys.

Table 4.

The values of tensile strength and elongation of refined A356 alloys.

T6 heat treatment facilitates the increment of tensile strength due to the participate of second phases, such as Mg2Si. After T6 heat treatment, the tensile strengths of the alloys are all higher than those before T6 heat treatment. As seen in Figure 9 and Table 4, the tensile strength of Alloy No. III is still the highest, with a value of 261.13 MPa, combined with a decline in the elongation of 5.5%. The significant increase in tensile strength after T6 treatment is attributed to precipitation hardening, where a high density of fine β”-Mg2Si precipitates forms within the α-Al matrix, effectively impeding dislocation motion [25]. The concomitant decrease in elongation, however, is a direct consequence of this strengthening mechanism. The dense precipitate network severely restricts plastic flow by hindering dislocation glide, thereby reducing the material’s capacity for uniform deformation before necking initiates [26]. Additionally, the potential formation of precipitate-free zones along grain boundaries may further localize strain and contribute to the reduced ductility [27]. This strength–ductility trade-off is characteristic of age-hardenable aluminum alloys.

4.3. Discussion on the Effect of La on the Second Phase in Al-Ti-B Refiner

The rare-earth element La, as a surface-active substance, can generate Ti2AL20La particles when added to aluminum melt. Due to the low solubility of La in aluminum melt, it tends to segregate at the interface between α-Al and TiAl3 particles during solidification, thereby hindering the growth and aggregation of TiAl3 and promoting the formation of small TiAl3 phases. In addition, La can fill the defects at the original crystal interface, further suppressing the aggregation and growth of second-phase particles and providing more small and symmetrical nucleation substrates for heterogeneous nucleation [28]. Additionally, La has the ability to induce needle-like to spherical transformation in aluminum and aluminum alloys. Microscopic observations show that needle-like TiAl3 and agglomerated TiB2 particles are not present in the Al-La-Ti-B refiners. Therefore, the addition of La effectively reduces the size and improves the morphology of the TiAl3 phase, optimizes the distribution of the TiB2 phase, and significantly enhances heterogeneous nucleation.

4.3.1. Effect of La on TiB2 Phase

In the Al-Ti-B refining agent system, TiB2 particles are prone to aggregation and precipitation, leading to a gradual weakening of the refining effect. The aggregation morphology of TiB2 is mainly divided into two types: dense and loose. Among them, dense aggregation has a poor refinement effect, while loose aggregation can demonstrate a good refinement effect. When the system transforms into the Al-La-Ti-B structure, the rare-earth element La plays a crucial role, which will react with other components (Ti and Al) in the system to form a Ti2AL20La phase that can quickly melt and effectively reduce the surface energy of the system, thereby hindering the aggregation and precipitation process of borides [29]. Thus, in aluminum melt, TiB2 can be uniformly dispersed in particles. More evenly dispersed TiB2 particles can significantly improve the refinement effect. Moreover, these particles are less prone to agglomeration and precipitation. In this way, not only does it prolong the effective refining time of the refiner, but it also greatly enhances the ability of the Al-La-Ti-B refiner to resist the degradation of the effect [30].

4.3.2. Effect of Rare-Earth La on TiAl3 Phase

The influence of elemental La on the TiAl3 phase is mainly reflected in microstructure refinement and performance optimization. La suppresses the coarsening and aggregation of the TiAl3 phase; the size can be refined from 50 μm to below 15 μm, thus promoting the uniform dispersion distribution of TiAl3 phase. Also, the segregation of La at the interface of TiAl3 matrix reduces the interfacial energy and inhibits atomic diffusion [15]. This effect has been applied to aviation-grade high-strength aluminum alloys and high-temperature titanium aluminum alloys, providing key support for high-performance alloy design.

4.4. Effect of La on the Refining Effect of Al-La-Ti-B Refiner

As discussed above, the elemental La on the refining agent is reflected in two aspects: on the one hand, the La element can improve the morphology and distribution of the second phases; on the other hand, the La element, as a surface-active substance, promotes heterogeneous nucleation, aggregates at grain boundaries and phase boundaries, fills surface defects, and inhibits grain growth. This aggregation behavior reduces the contact area between crystal nuclei, liquid phase, and residual impurities [30].

where, Fk is the nucleation energy; σ1 is the specific surface energy between the crystal nucleus and impurities; σ2 is the specific surface energy between the crystal nucleus and liquid; S1 is the contact area between the crystal nucleus and impurities; and S2 is the contact area between the crystal nucleus and the liquid.

Due to the addition of elemental La, the contact area decreases, and during the process of grain growth, the surface energy decreases, resulting in a decrease in nucleation work. Therefore, the reduced nucleation work of grains makes it easier to promote nucleation, increase the nucleation rate, and promote grain refinement. Based on the experimental results, the addition of the rare-earth element La also improves the morphology and size of the second phases. The size of TiAl3 decreased, and the distribution of TiB2 particles become more evenly dispersed.

Therefore, the addition of La imparts effective grain refinement capability to the Al-Ti-B refiner. Comparing four different La-containing refiners, the Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B refiner produces the TiB2 phase and LaB6 phase in A356 alloy, with TiB2 acting as the primary refining phase and contributing to enhanced refinement. For Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B, because the release of La from the Al11La3 phase can enhance the surface activity of TiB2 and improve the refinement effect, this refiner demonstrates optimal refinement efficacy. As the Ti content increases, the Al-1.5La-2.5Ti-1B and Al-1La-3.5Ti-1B refiners produce TiB2, TiAl3, and Ti2AL20La phases when refining A356 alloy. The excess Ti will form Ti-Si compounds such as τ-TiAlxSiy and TixSiy, inducing the poisoning of TiB2 refinement. Therefore, the refinement of these two refiners is relatively poor [8,31,32].

The above discussion highlights that the outstanding performance of the Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B refiner stems from the synergy between the CRE process and the optimized composition. The CRE process guarantees the fine and uniform distribution of second phases, which is a prerequisite for effectively studying and utilizing the beneficial effects of La. Concurrently, the optimization of the Ti/La ratio ensures that these well-dispersed phases possess the highest nucleation potency against Si poisoning.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a new CRE Al-La-Ti-B refiner was developed. The microstructures under different Ti contents are studied, the refinement effect on A356 alloys were discussed, and the mechanical properties including the tensile strength and elongation are measured. Based on the experimental results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) Thermodynamic calculations and microstructure investigations shows that the main second phases of the Al-La-Ti-B refiner includes five phases: α-Al, TiAl3, TiB2, Al11La3, LaB6, and Ti2AL20La. As the Ti content increases, the second phases evolve from TiB2 and LaB6 for Al-0.5La-1Ti-1B to TiAl3, Ti2AL20La, and TiB2 phases for Al-1La-3.5Ti-1B alloys.

(2) The macro- and microstructures of the refined A356 alloys show that the smallest grain size of 221 μm and SDAS of 24.62 μm under 0.2 wt.% Al-2.5La-1Ti-1B addition is obtained. On this basis, before the T6 heat treatment, the tensile strength and elongation of refined A356 alloy are 164.52 MPa and 9.0%, respectively. After the T6 heat treatment, the tensile strength increases to 261.13 MPa along with a decline in the elongation of 5.5%.

(3) Elemental La not only improves the morphology and distribution of the second phases of TiB2 and TiAl3 but also, as a surface-active substance, decreases the nucleation work during the process of grain growth, promoting heterogeneous nucleation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.H. and H.L.; Methodology, Q.H.; Validation, Y.L., H.Q., S.Z., S.L. (Shide Li), Q.L., S.L. (Shuji Liu), J.Z. and R.G.; Formal analysis, Q.H.; Investigation, Q.H. and S.Y.; Resources, G.Z., Y.L., H.Q., S.L. (Shide Li), Q.L., S.L. (Shuji Liu) and R.G.; Data curation, Q.H., S.Z. and J.Z.; Writing—original draft, Q.H.; Writing—review and editing, G.Z., Y.L., H.Q., S.Z., S.L. (Shide Li), Q.L., S.Y., S.L. (Shuji Liu), J.Z. and R.G.; Visualization, S.Z. and J.Z.; Supervision, G.Z., H.L. and S.Y.; Project administration, G.Z.; Funding acquisition, G.Z., S.Y. and R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dalian Science & Technology Innovation Foundation Project [grant No. 2024JJ11PT003], National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant No. U2341253, 52371019], Key Research and Development Program of Liaoning Province [grant No. 2025JH2/101800136], and Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province [grant No. JYTMS20230031].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yongfei Li, Haibo Qiao, Haifeng Liu, Shide Li, Qiang Liu and Shuji Liu were employed by the company CITIC Dicastal Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Cui, X.; Cui, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X. The improvement of electrical conductivity of hypoeutectic Al-Si alloys achieved by composite melt treatment. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 788, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gu, D.; Xi, L.; Zhang, H.; Shi, K.; Wu, B.; Zhang, R.; Qi, J. High-performance aluminum-based materials processed by laser powder bed fusion: Process, microstructure, defects and properties coordination. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2024, 3, 200145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.H.; Shin, J.H.; Bae, D.H. Si phase modification on the elevated temperature mechanical properties of Al-Si hypereutectic alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 748, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Du, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W. Effect of Al-Ti-C master alloy addition on microstructures and mechanical properties of cast eutectic Al-Si-Fe-Cu alloy. Mater. Des. 2017, 115, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunitha, K.; Gurusami, K. Study of Al-Si alloys grain refinement by inoculation. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 1825–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A.L.; Bunn, A.M.; Tronche, A.; Evans, P.V.; Bristow, D.J. Modelling of inoculation of metallic melts: Application to grain refinement of aluminium by Al–Ti–B. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 2823–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Que, Z.; Hashimoto, T.; Zhou, X.; Fan, Z. Mechanism for Si Poisoning of Al-Ti-B Grain Refiners in Al Alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 5743–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, B.; Liu, B.; Nie, A.; Gu, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, Q. Insight into Si poisoning on grain refinement of Al-Si/Al-5Ti-B system. Acta Mater. 2020, 187, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Luo, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, H. Effect of La addition on microstructure and mechanical properties of hypoeutectic Al-7Si aluminum alloy. China Foundry 2021, 18, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhao, X.; Chen, T.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Lei, D. Effect of rare earth Y and Al–Ti–B master alloy on the microstructure and mechanical properties of 6063 aluminum alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 830, 154685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Yuan, L.; Peng, L.; Pan, F.; Ding, W. Achieving grain refinement of α-Al and Si modification simultaneously by La–B–Sr addition in Al–10Si alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 135, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Hu, M.; Li, X.; Piao, J. Synthesis of Al-5Ti-1B-1Ce alloy from remelted chips and its refinement effect. Mater. Lett. 2023, 349, 134798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Tang, H.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Peng, F.; Zheng, X.; Wang, J. Anti-fading study of Al–Ti–B by adding Ce on 6111 aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 2420–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Li, J.; Mao, H.; Lang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Han, F.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, J.; Du, X. Effects of (Ce+Yb) Combined Modification on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of TiB2/Al–Si–Mg–Cu–Cr Composites. Int. J. Metalcast. 2025, 19, 2945–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Zhao, Q.; Ping, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Li, Z.; Cai, Q. Effect of Al–5Ti–1B–La intermediate alloy on microstructure and mechanical properties of A356.2 aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 1458–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, Q.; Zhang, G.; Yin, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Guan, R. Balancing strength and electrical conductivity in recycled Al-Mg-Si alloys: Beneficial effect of combining continuous rheo-extrusion processing with Al-5Ti-1B refiner. Mater. Des. 2025, 255, 114169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, C.W.; Bélisle, E.; Chartrand, P.; Decterov, S.A.; Eriksson, G.; Gheribi, A.E.; Hack, K.; Jung, I.H.; Kang, Y.B.; Melançon, J.; et al. FactSage thermochemical software and databases, 2010–2016. Calphad 2016, 54, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Chen, Z.Q.; Hu, W.X.; Shi, L.; Wang, W. Effect of rare earth on morphology and dispersion of TiB2 phase in Al-Ti-B alloy refiner. China Foundry 2023, 20, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Guan, R. Mechanical Properties of Refined A356 Alloy in Response to Continuous Rheological Extruded Al-5Ti-0.6C-1.0Ce Alloy Prepared at Different Temperatures. Metals 2023, 13, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Guan, R. Response of mechanical properties of A356 alloy to continuous rheological extrusion Al-5Ti-0.6C-xCe alloy addition upon different Ce contents. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Jia, H.; He, Q.; Guan, R. Microstructure evolution and strengthening mechanism of A356/Al-X-Ce(Ti, C) system by inoculation treatment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, D.; Zhu, G.; Jiang, M.; Shu, D.; Mi, J.; et al. Effect of trace boron on grain refinement of commercially pure aluminum by Al–5Ti–1B. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, H.; He, J.; Zhao, J. Kinetic behaviour of TiB2 particles in Al melt and their effect on grain refinement of aluminium alloys. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2020, 30, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amne Elahi, M.; Shabestari, S.G. Effect of various melt and heat treatment conditions on impact toughness of A356 aluminum alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.J.; Kocks, U.F.; Scattergood, R.O. The effect of dislocation self-interaction on the orowan stress. Philos. Mag. 1973, 28, 1241–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Wu, Y.; Ding, K. Hardening response and precipitation behavior of Al–7%Si–0.3%Mg alloy in a pre-aging process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 560, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, F. Research Status and Prospective Properties of the Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Series Aluminum Alloys. Metals 2023, 13, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; He, J.; Jiang, H. Synergistic Effect of La and TiB2 Particles on Grain Refinement in Aluminum Alloy. Materials 2022, 15, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y. Effect of rare earth element on Al-Ti-B-RE master alloys. J. Cent. South Univ. 2005, 36, 386–389. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.Y.; Chen, S.L.; Chou, K.C. Experimental investigation and thermodynamic calculation of the Al–Si–Ti system in Al-rich corner. J. Alloy. Compd. 2014, 602, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, Q.; Luo, Q.; Pang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chou, K.; Wang, X.; Li, Q. Thermodynamic investigation on phase formation in the Al–Si rich region of Al–Si–Ti system. Mater. Des. 2016, 102, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.