Abstract

This study systematically investigates the composition–structure–property relationships in electrospark-deposited Cr-Ta coatings (10, 25, and 40 at.%) on CrNi3MoVA steel for wear resistance applications. Microstructural characterization reveals that the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits a dense microstructure with excellent metallurgical bonding to the substrate, consisting of a reinforcing Cr2Ta Laves phase and Fe-Cr solid solution. In contrast, higher Ta content (25–40 at.%) results in the formation of brittle Ta oxides and the development of cracks. Mechanical testing indicates that the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits superior hardness (6.35 GPa) and elastic–plastic deformation resistance (H/E = 0.041, H3/E2 = 0.0109), outperforming both higher-Ta coatings and the substrate material. Corresponding tribological assessments reveal that the Cr-10Ta coating achieves the lowest friction coefficient (~0.4) along with a minimal wear rate, which can be attributed to its synergistic combination of fine-grained structure, high dislocation density, and Laves phase reinforcement. The findings underscore that precise control over Ta content serves as an effective strategy for optimizing the wear resistance of Cr-Ta coatings through microstructural engineering.

1. Introduction

Wear is a predominant mode of component failure in mechanical systems, and enhancing material wear resistance is critical for extending part service life. This is particularly crucial in the weapons industry, where mechanical components are subjected to extreme conditions and stringent performance requirements [1]. A prominent example is the gun barrel, which experiences severe wear during firing, leading to diminished initial velocity, reduced accuracy, and, ultimately, premature barrel condemnation [2]. Conventional gun steels often fail to meet these demanding operational needs, making the development of advanced barrel life extension technologies a significant engineering challenge [3]. Among potential solutions, improving the tribological properties of barrel material surfaces represents a promising approach to achieving high-performance, long-lasting weapon systems. Consequently, an in-depth study of wear mechanisms and the development of novel tribological materials and technologies hold significant theoretical and practical value.

One effective strategy for enhancing gun barrel durability involves applying protective metallic coatings [4]. Electrodeposited chromium has been widely adopted due to its exceptional hardness, corrosion resistance, and wear resistance. However, as modern warfare demands higher initial velocities and firing rates and longer ranges of high-explosive projectiles, chromium-plated gun barrels increasingly suffer from accelerated wear. The formation of perforated cracks in conventional chromium coatings further limits their effectiveness under these extreme conditions [5]. In contrast, tantalum has emerged as an attractive alternative owing to its lower thermal conductivity and superior ductility compared to chromium [6]. Nevertheless, tantalum coatings often exhibit a mixture of α-Ta (ductile) and β-Ta (brittle) phases during deposition, with the former being highly desirable for crack suppression. Achieving pure α-Ta coatings remains technically challenging, prompting researchers to explore Cr-Ta composite coatings as a potential solution for improving the wear resistance and crack mitigation at the gun barrel/coating interface [7,8].

At present, existing studies on Cr-Ta coatings have primarily focused on the exploration of their mechanical properties, wear resistance, and corrosion behavior. For instance, Li et al. prepared Ta-Cr amorphous alloy coatings (50–70 at.% Ta) on the surface of CrNi3MoVA steel via double-target co-sputtering and found that reducing Ta concentration improved hardness, elasticity, and ductility [9]. Similarly, Spiak et al. produced Ta-Cr alloy coatings (2–6 at.% Cr) using molten salt electrodeposition, observing that increased Cr content enhanced microhardness and refined grain structure, thereby improving wear resistance [10]. Chang et al. further demonstrated that amorphous/nanocrystalline Cr-Ta coatings (37–71 at.% Cr) prepared by magnetron sputtering exhibited higher hardness than pure Cr or Ta coatings [11]. Additionally, Kim et al. [12,13] reported that sputtered amorphous Cr-Ta alloy displayed superior corrosion resistance compared to its constituent elements. Despite their excellent properties, refractory alloy coatings such as Cr-Ta face manufacturing challenges due to their high strength and melting points. Electrospark deposition (ESD) technology offers a viable solution, combining high energy density with low heat input to deposit robust coatings efficiently [14]. During ESD, a rotating or vibrating electrode generates high-current sparks that transfer material to the substrate, enhancing surface hardness and wear resistance [15]. This method has been successfully applied to produce Cr [16], Ta [17], self-lubricating [18], and high-entropy alloy coatings [14], demonstrating its versatility for military applications.

While numerous studies have explored Cr-Ta coatings with Ta content exceeding 30 at.%, research on low-Ta (<30 at.%) coatings prepared by ESD remains scarce. Moreover, the underlying wear mechanisms and key factors influencing their tribological performance are yet to be systematically investigated. In this study, Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents were fabricated using ESD, and their microstructure, morphology, and tribological properties were thoroughly characterized. This work aims to elucidate wear mechanisms and optimize coating design, providing a scientific foundation for enhancing the reliability and longevity of critical weapon components.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

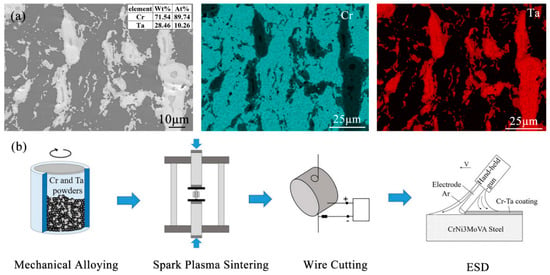

CrNi3MoVA steel samples with dimensions of 20 mm × 10 mm × 4 mm were utilized as the substrate material in this experiment, and their composition is detailed in Table 1. The electrode material consisted of Cr and Ta powders with a purity exceeding 99%, and both powders had a particle size of 45 μm. The compositions were designated as Cr-10Ta, Cr-25Ta, and Cr-40Ta, corresponding to nominal Ta additions of 10 at.%, 25 at.%, and 40 at.%; their composition is detailed in Table 1. The Cr and Ta powders were thoroughly mixed through ball milling and then sintered in an HPD250-C spark plasma sintering furnace (FCT Group, Rauenstein, Germany) to fabricate Cr-Ta composite materials. During the sintering process, the materials were heated to 1100 °C under a pressure of 40 MPa for a duration of 15 min, resulting in a sintered product with a diameter of 40 mm. Figure 1a shows the morphology and EDS analysis of Cr-Ta electrodes, which are a mixture of Cr and Ta particles. Subsequently, the composite Cr-Ta materials were machined into cylindrical electrodes with a diameter of 6 mm and a length of 50 mm.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of CrNi3MoVA steel and Cr-Ta materials (wt.%).

Figure 1.

Experimental description of Cr-Ta coatings prepared by ESD: (a) the microstructure and EDS elemental mapping of the electrode; (b) schematic of the preparation process.

Prior to coating deposition, both the substrate and the electrode materials were polished using 1500# sandpaper to eliminate surface oxides. Following polishing, they were cleaned in anhydrous ethanol for 10 min, then dried with compressed air before being set aside for later use. The Cr-Ta coatings were fabricated onto the CrNi3MoVA steel substrates using an electrospark deposition machine (DJ-2000, Shanghai Kangbei Mechanical and Electrical Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) under argon protection. The deposition process was conducted under an argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation. The specific deposition parameters were maintained at 80 V voltage, 1200 W power, 3200 r/min electrode rotation speed, 2 min/cm2 deposition time per unit area, and 15 L/min argon flow rate to ensure optimal coating quality and prevent oxidation. Figure 1b shows a schematic of the coating preparation process.

2.2. Characterization Methods

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) coupled with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS, X-Max, Oxford Instruments Co., Oxford, UK) was utilized to analyze the surface morphologies, worn morphologies, cross-sectional microstructure, and elemental distribution of the coatings. Phase analysis of the coatings was performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD, X’ Pert PRO, PANalytical Co., Almelo, The Netherlands). Post-electrolytic polishing, the microstructure of the coatings was further analyzed using electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD, Tescan Orsay Holding, Brno, Czech Republic), providing detailed insights into crystallographic orientations and grain boundaries.

A Berkovich-type diamond tip on a nanoindentation instrument (Nano G200, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to measure the nanoindentation micro-hardness (H) and elastic modulus (E) of the coatings. Each data point represents the average of six separate measurements on the same sample. The wear resistance of the coatings was assessed using a high-speed reciprocating friction tester (HSR-2M, Zhongke kaihua, Shenzhen, China), with a 304 stainless steel ball (6 mm diameter) as the friction counterpart. The wear test parameters were 6 N load, 5 mm reciprocation distance, 500 t/min reciprocation speed, and 5 min total duration. Wear loss was quantified by pre- and post-wear test weightings using a high-precision electronic balance (MS205DU, Mettler-Toledo International Inc., Greifensee, Switzerland) sensitive to 0.01 mg. The three-dimensional morphologies and surface roughness of the coatings were measured using a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, LS4000, Osaka, Japan). The roughness measurement was carried out using a contact-type profilometer, with its stylus gently traced along the surface of the sample at a constant speed. The vertical displacements of the stylus were recorded, and these data were then processed to calculate the roughness parameter Ra.

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure

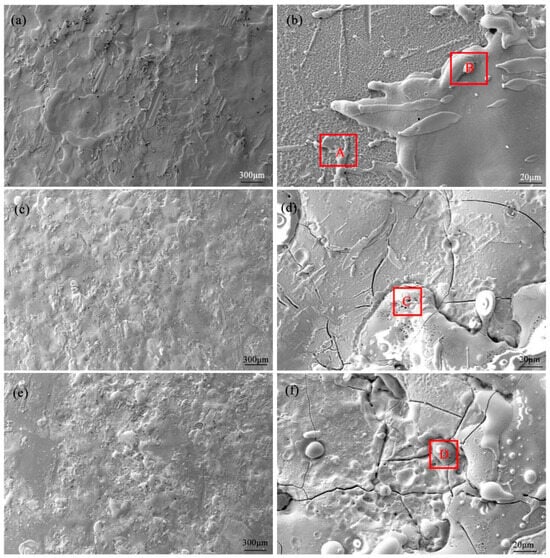

The surface morphology and cross-sectional characteristics of Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta concentrations (10 at.%, 25 at.%, and 40 at.%) are systematically presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. As depicted in Figure 2a,c,e, the coatings exhibit typical ESD characteristics, consisting of unevenly distributed deposition spots with distinct edge accumulations. The splash-like patterns observed at spot peripheries clearly indicate rapid solidification during the ESD process. Two prominent composition-dependent trends are evident: firstly, the deposition spot size decreases with increasing Ta content, with the Cr-10Ta coating showing the largest spots. This can be attributed to the significantly higher melting point of Ta (2996 °C) compared to Cr (1860 °C), meaning molten Ta has less time to splash before solidification, leading to smaller spots. Secondly, surface crack density shows a marked increase with higher Ta concentrations. The higher thermal expansion coefficient of Ta (6.5 × 10−6 K−1) compared to Cr (6.2 × 10−6 K−1) results in greater thermal stress during cooling as Ta content increases, which in turn promotes crack formation. Notably, the Cr-10Ta coating shows minimal cracking, mainly due to the thermal stress resulting from the rapid cooling characteristic of the ESD process [19].

Figure 2.

Surfaces of Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents: (a,b) Cr-10Ta coating, (c,d) Cr-25Ta coating, and (e,f) Cr-40Ta coating at low and high magnifications.

Figure 3.

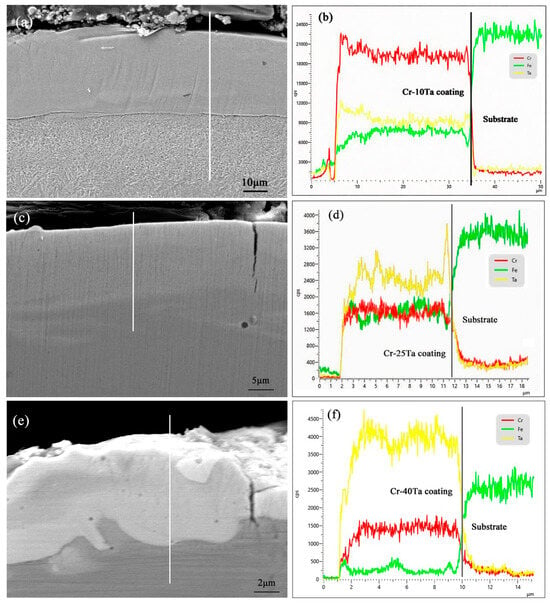

SEM cross-sectional images and corresponding EDS line scans of Cr-Ta coatings: (a,b) Cr-10Ta coating, (c,d) Cr-25Ta, (e,f) Cr-40Ta coating.

The high-resolution SEM images in Figure 2b,d,f reveal distinct microstructural features across the Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents. In the Cr-10Ta coating (Figure 2b), region A denotes a flat deposition spot, while region B shows the bulge formed by molten droplet particles at the edge of the deposition point. EDS analysis (Table 2) indicates that region B contains slightly elevated Cr and Ta concentrations compared to area A, attributed to localized variations in pulse energy during deposition that enhance material melting and transfer at these edge locations. For the higher-Ta-content coatings (Figure 2d,f), regions C and D illustrate a deposition site with numerous visible cracks. The EDS spectra of these regions demonstrate Ta enrichment with increasing nominal composition. In addition to Cr and Ta, the coatings also contain Fe and Ni, while O is present in the Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings. The significant presence of Fe elements in the Cr-Ta coatings can be explained by the intense energy from the electrical discharge during the ESD process, which rapidly melts and vaporizes the electrode material and a small portion of the substrate. This creates a molten pool and tiny droplets on the substrate surface, quickly solidifying to become a part of the coating [15].

Table 2.

EDS quantitative results of areas A, B, C, and D (at.%).

Cross-sectional analysis (Figure 3) reveals a progressive microstructural evolution with composition changes. The Cr-10Ta coating (Figure 3a) exhibits a dense, uniform 30 μm thick structure with excellent interfacial integrity, while Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings (Figure 3c,e) show reduced thicknesses (16 μm and 8 μm, respectively) and increased cracking. This trend is likely due to the low solid solubility between Fe and Ta, as indicated by the Fe-Ta phase diagram, where the higher the Ta content, the thinner the Cr-Ta coating. As depicted in elemental line scans (Figure 3b,d,f), elements of Cr and Ta transit gradually from the coating to the substrate, while Fe in the CrNi3MoVA steel shows an opposite trend, indicating a strong metallurgical bond between the Cr-Ta coatings and the substrate.

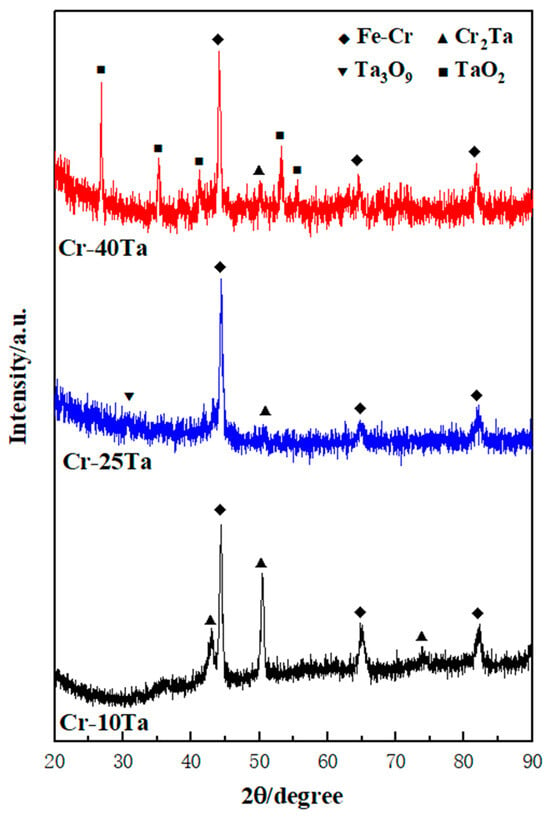

Figure 4 displays the X-ray diffraction patterns of Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents. The XRD peaks, supported by EDS results (Table 2), indicate the presence of Cr2Ta and Fe-Cr solid solution in the Cr-10Ta coating. Furthermore, the Cr-25Ta coating contains Fe-Cr solid solution, along with trace amounts of Ta3O9 and Cr2Ta. In contrast, the Cr-40Ta coating includes oxides TaO2 and Fe-Cr solid solution, as well as trace amounts of Cr2Ta. EDS surface analysis of the Cr-Ta coatings confirms a significant presence of Fe elements. The Fe-Cr phase diagram shows that Cr and Fe form continuous solid solutions in both liquid and solid states, supporting the observed formation of Fe-Cr solid solution in the coatings [20]. Moreover, given that the cooling rates of the coatings during the ESD process can reach 105–106 K/s, the formation of Cr-Ta coating is an unbalanced process, favoring the formation of Cr2Ta. A small amount of tantalum oxides is observed in the Cr-25Ta coatings, while a large amount of tantalum oxides is found in the Cr-40Ta coatings, which is likely attributable to the relatively high affinity of Ta for oxygen. With an increase in Ta content, the quantity of oxides generated via reaction also increases. In addition, a broad peak is observed at approximately 35°, which confirms that the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits a microcrystalline structure. This is probably due to the extremely rapid cooling rate during the ESD process, which makes it difficult for crystal nuclei to grow, thereby facilitating the formation of fine grains.

Figure 4.

XRD pattern of Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents.

3.2. Mechanical Properties

The nanomechanical properties of CrNi3MoVA steel and Cr-Ta coatings with different Ta contents are summarized in Table 3. All Cr-Ta coatings exhibit significantly higher hardness than the uncoated CrNi3MoVA substrate, consistent with previous reports on Cr coatings [16]. The larger radius of Ta atoms compared to Cr atoms leads to greater lattice distortion in the coatings. This distortion leads to solution strengthening and impedes dislocation motion, thereby increasing the hardness of the Cr-Ta coatings. Furthermore, the presence of hard Cr2Ta Laves phase precipitates in the Cr-10Ta coating, which acts as a reinforcing component [21]. However, the hardness of the Cr-Ta coatings decreases with increasing Ta content. This decrease is due to the lower hardness of Ta compared to Cr, resulting in a corresponding decrease in coating hardness with higher Ta content. These findings are consistent with those reported by Spiak et al. [10], confirming the composition-dependent mechanical behavior of Cr-Ta systems.

Table 3.

Nanomechanical properties of CrNi3MoVA steel and the Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents.

3.3. Wear Resistance

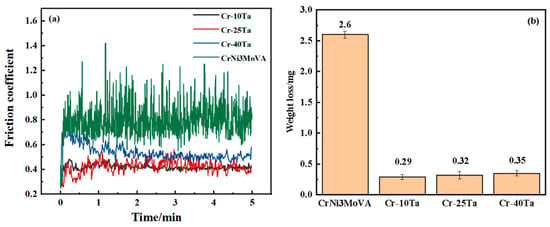

The tribological behavior of CrNi3MoVA steel and Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents is systematically compared through friction coefficient analysis (Figure 5a) and wear loss measurements (Figure 5b). The friction coefficient of all Cr-Ta coatings displays three distinct phases: an initial rising phase, a running-in period, and a stabilization phase. During the initial rising phase, minor surface irregularities and the accumulation of abrasive particles contribute to an increase in the friction coefficient. Throughout the running-in period for all the Cr-Ta coatings, surface roughness is reduced as minor protrusions wear down. Furthermore, the detachment of some abrasive particles from the contact surfaces results in a reduction in the friction coefficient. During the stabilization phase, all Cr-Ta coatings experience increased surface contact with the 304 stainless steel ball, leading to a gradual stabilization of the friction coefficient. It is apparent that the Cr-10Ta coating demonstrates superior performance with the lowest (~0.4) and most stable friction coefficient, while Cr-25Ta (0.4–0.5) and Cr-40Ta (~0.5) require longer stabilization times due to their higher surface roughness resulting from increased deposition points [22]. In contrast, CrNi3MoVA steel displays only running-in and stabilization phases with significantly higher (0.7–0.95) and more variable friction coefficients, attributable to its relatively smooth surface but inferior wear resistance. As shown in Figure 5b, all Cr-Ta coatings show approximately 86% reduction in wear loss compared to CrNi3MoVA steel. The Cr-10Ta coating exhibits the smallest worn volume and lowest wear rate according to Archard’s equation (V = μLN/H) [23] and wear rate calculations (ω = V/(L × F)) [24], owing to its optimal combination of low friction coefficient (μ) and high hardness (H). The degradation in wear resistance with increasing Ta content is clearly reflected in both the quantitative wear measurements and the corresponding surface morphology observed in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Friction coefficient (a) and wear loss (b) of CrNi3MoVA steel and the Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents.

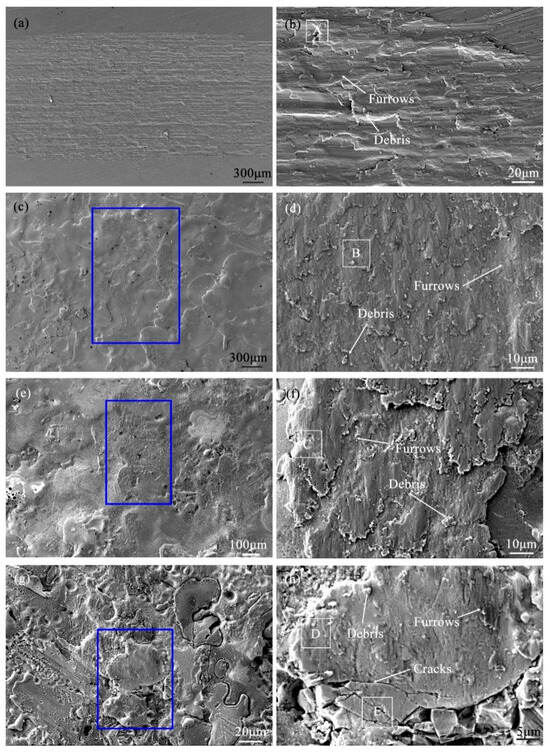

Figure 6.

Worn morphology of CrNi3MoVA steel (a,b), Cr-10Ta coating (c,d), Cr-25Ta coating (e,f), and Cr-40Ta coating (g,h) at low and high magnifications.

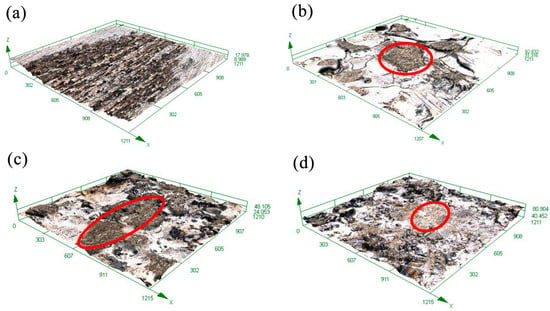

The surface morphology analysis provides critical insights into the performance differences of CrNi3MoVA steel and Cr-Ta coatings. As illustrated in Figure 6a,c,e,g and Figure 7, the worn surface of CrNi3MoVA steel has noticeably wider scratches and deep depressions compared to the relatively smooth wear tracks on Cr-Ta coatings, where damage is primarily confined to the elevated deposition areas. This distinct morphological difference stems from the hardness disparity between materials, while the similar strength between CrNi3MoVA steel and the 304 stainless steel friction pairs leads to severe interfacial shear damage and substantial wear loss, which makes the actual contact state at the friction interface unstable, directly causing a significant fluctuation for the friction coefficient of the CrNi3MoVA steel and making the material more susceptible to adhesive wear. As the hardness of the Cr-Ta coatings exceeds that of the friction pair, shear damage primarily occurs on the friction pair surface, leading to minimal coating wear [25]. Furthermore, the increased hardness of the three Cr-Ta coatings compared to CrNi3MoVA steel contributes to their improved wear resistance during frictional interactions. This enhanced wear resistance is attributed to the coatings’ ability to more effectively withstand the forces exerted by the friction pair, leading to reduced wear volume for the Cr-Ta coatings compared to CrNi3MoVA steel.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional worn morphologies: (a) CrNi3MoVA steel, (b) Cr-10Ta coating, (c) Cr-25Ta coating, (d) Cr-40Ta coating.

High-magnification SEM images (Figure 6b,d,f,h) show characteristic wear patterns, with furrows and debris visible on the worn surface, and severe plastic deformation occurring beside the furrows. The wear process initiates with stress concentration at the edge of the micro-protrusion during sliding contact, leading to fracture and the generation of abrasive debris. This debris is continuously squeezed and embedded into the material surface under continuous friction. When two surfaces rub against each other, mechanical energy is transformed into heat energy, resulting in a sharp temperature rise in the contact area. The combination of reciprocating motion and frictional heating promotes debris adhesion and plastic flow, ultimately resulting in the formation of distinct adhesive layers. EDS analysis (Table 4) further corroborates this wear mechanism by demonstrating an elevated oxygen content in wear scars (areas A–D) compared to the material prior to wear (Table 2), indicating high-temperature oxidation of debris during rubbing. This is due to a large amount of heat generated by the rapid rubbing process, leading to a drastic elevation in the temperature within this region. The worn debris undergoes vigorous chemical reactions with oxygen, ultimately leading to a significant increase in the oxygen content in the worn area. For the Cr-Ta coatings, substantial amounts of iron are transferred (areas B–D) from the softer 304 stainless steel counterpart, demonstrating their superior wear resistance through preferential material removal from the friction pair. However, it is noteworthy that the Cr-40Ta coating exhibits localized Ta/O enrichment (area E) along with Ta oxide aggregates, as confirmed by XRD. These features suggest that excessive Ta content promotes oxide formation, when combined with inherent coating cracks, leads to brittle fracture under shear stress. This microstructural vulnerability explains the coating’s inferior performance despite its hardness advantage over CrNi3MoVA steel. The combined evidence from morphology, composition analysis, and mechanical testing consistently demonstrates that while all Cr-Ta coatings outperform the CrNi3MoVA steel substrate, the Cr-10Ta composition achieves optimal wear resistance through balanced hardness and toughness, avoiding both plastic deformation failure and brittle fracture.

Table 4.

EDS quantitative results of areas A, B, C, D, and E (at.%).

4. Discussion

4.1. Microstructural Influence on the Tribological Performance of Cr-Ta Coatings

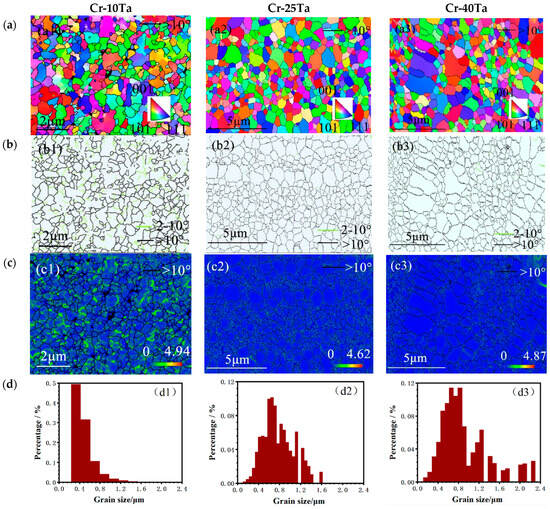

The tribological performance of Cr-Ta coatings is strongly influenced by their microstructure, particularly grain size, grain boundary characteristics, and dislocation density. Among the three coatings, the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits superior wear resistance, which can be attributed to its refined microstructure and high dislocation density. Figure 8 depicts the EBSD maps of the Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents. All three coatings exhibit equiaxed grain structures, as evidenced by inverse pole figure (IPF) maps (Figure 8a) [26]. However, distinct variations in grain size distribution are observed. The Cr-10Ta and Cr-25Ta coatings (Figure 8(a1,a2)) show relatively uniform grain distributions, while the Cr-40Ta coating contains a minor fraction of large grains (Figure 8(a3)). This grain coarsening can be attributed to the high melting point of Ta, which requires greater energy input during the ESD process. Consequently, extended high-temperature exposure promotes grain growth. A uniform distribution of equiaxed grains ensures a more uniform stress distribution within stressed material, thereby preventing premature failure due to localized stress concentration. Equiaxed grains exhibit consistent mechanical properties in all directions, enabling the material to better resist friction from multiple directions during rubbing, which reduces plastic deformation and localized severe wear. In contrast, the Cr-40Ta coating, with its coarse grains, is prone to grain boundary cracking and material spalling during rubbing, resulting in inferior wear resistance. This observation is consistent with the findings presented in Figure 6h.

Figure 8.

EBSD analysis of Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents: (a) inverse pole figure (IPF) map; (b) GBs maps; (c) kernel average misorientation (KAM) maps; (d) grain size distribution statistics.

Figure 8b presents the grain boundary (GB) maps of Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents. Black lines denote high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs, >10°), while green lines denote low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs, 2°–10°). As depicted in Figure 8(b1), the Cr-10Ta coating primarily consists of grains with LAGBs, which make up about 28.2%. In contrast, Figure 8(b2) and Figure 8(b3) reveal that the Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings are mainly composed of HAGBs, with LAGBs accounting for only 2.09% and 2.42%, respectively. A higher density of LAGBs correlates with a higher dislocation density [27]. This increased dislocation density contributes to surface work hardening, as supported by the hardness data presented in Table 3. Consequently, the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits the highest hardness among the three coatings.

Kernel average misorientation (KAM) maps are illustrated in Figure 8c. Prior research has demonstrated that the KAM value can serve as an indicator of dislocation density [28,29]. The dislocation density is represented on a color scale ranging from blue (low density) to red (high density). As shown in Figure 8(c2) and Figure 8(c3), dislocation density is predominantly blue, with green areas sparsely distributed along grain boundaries, indicating that the overall dislocation density in the Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings is relatively low. However, in Figure 8(c1), the KAM map of the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits increasingly distributed green areas, which indicates higher dislocation density [30]. Upon achieving a high dislocation density, the formation of dislocation entanglement becomes highly probable, ultimately resulting in an increase in the hardness. Consequently, the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits the highest hardness and outstanding wear resistance [31].

Figure 8d quantitatively analyzes the grain size and its distribution in Cr-Ta coatings. As depicted in Figure 8d, the majority of grains in the Cr-10Ta coating are less than 1 μm in size, whereas only half of the grains in the Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings are smaller than 1 μm. The average grain sizes for the Cr-10Ta, Cr-25Ta, and Cr-40Ta coatings are 0.403 μm, 0.487 μm, and 0.46 μm, respectively, indicating a fine-grained microstructure in the Cr-Ta coatings. The rapid cooling rate characteristic of ESD technology inhibits the growth of nuclei, leading to a fine-grained structure in the Cr-Ta coatings [15]. During the rubbing process, the resistance to deformation and fracture of the surface micro-convexities in fine-grained materials increases, thereby reducing the wear rate. This finding is consistent with the results reported in Roshan Sasi’s study [32].

In addition to microstructure, the phase composition of the coatings plays a critical role in their wear behavior. XRD and EDS analyses reveal that the Cr-40Ta coatings contain brittle tantalum oxides, which are prone to fracture during rubbing, exacerbating material loss. Moreover, Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings exhibit cracks (Figure 2 and Figure 3), further compromising their mechanical integrity. Under frictional stress, crack propagation leads to brittle spalling, significantly reducing wear resistance. In contrast, the Laves phase in the Cr-10Ta coating serves as a hardening phase, increasing the coating’s hardness and thus improving its wear resistance.

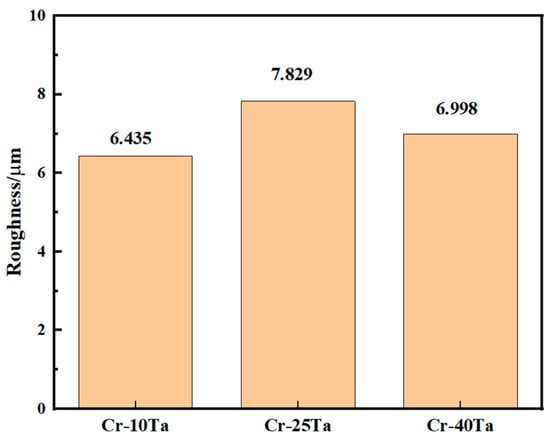

Surface roughness also affects tribological performance. As depicted in Figure 9, the Cr-10Ta coating has the lowest surface roughness, while the Cr-25Ta coating exhibits the highest surface roughness. Consequently, the friction coefficient of the Cr-25Ta coating exhibits significant fluctuations (Figure 5a). The Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings display numerous deposition points and cracks, increasing surface roughness. High surface roughness reduces the contact area of the worn surface, leading to point contact during rubbing. This leads to increased stress concentrations and resistance to plastic deformation on the worn surface, thereby raising the friction coefficient [33,34].

Figure 9.

Results of roughness (Ra) measurement on the surface of Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents.

4.2. Mechanical and Tribological Correlations of Cr-Ta Coatings

The wear resistance of Cr-Ta coatings is closely related to their mechanical properties, particularly hardness (H), elastic modulus (E), and their ratios (H/E, H/E2, and H3/E2). These parameters provide a multi-dimensional understanding of coating performance: the H/E ratio indicates the tolerance for elastic deformation, H/E2 signifies resistance to plastic deformation or permanent damage, and H3/E2 represents the capacity for energy dissipation during contact loading [35,36]. As illustrated in Table 5, the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits optimal mechanical characteristics with the highest values across all key parameters, significantly outperforming both the CrNi3MoVA steel substrate and other Ta-containing variants. This performance advantage arises from three primary mechanisms: (1) enhanced elastic energy absorption (high H/E) that prevents premature plastic deformation, (2) improved resistance to permanent surface damage (high H/E2), and (3) greater capacity for dissipating contact stresses (high H3/E2) [37,38].

Table 5.

Elastic-plastic deformation resistance parameters of CrNi3MoVA steel and the Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents.

With the increase in Ta content, a clear deterioration in mechanical parameters follows the trend Cr-10Ta > Cr-25Ta > Cr-40Ta, which is directly related to the observed wear resistance performance. Furthermore, the contact yield pressure is a crucial factor affecting the wear resistance of coatings. Contact yield pressure refers to the stress level at which the material begins to deform plastically under contact stress, as defined by the equation Py = 078r2/(H3/H2) [37]. The high H3/E2 value of the Cr-10Ta coating (0.0109) indicates its superior resistance to plastic yielding when compared to both the CrNi3MoVA steel substrate (0.0015) and higher-Ta-content coatings, elucidating its ability to maintain structural integrity during rubbing processes. However, this mechanical advantage progressively diminishes in Cr-25Ta (0.0065) and Cr-40Ta (0.0036) coatings, leading to reduced wear performance.

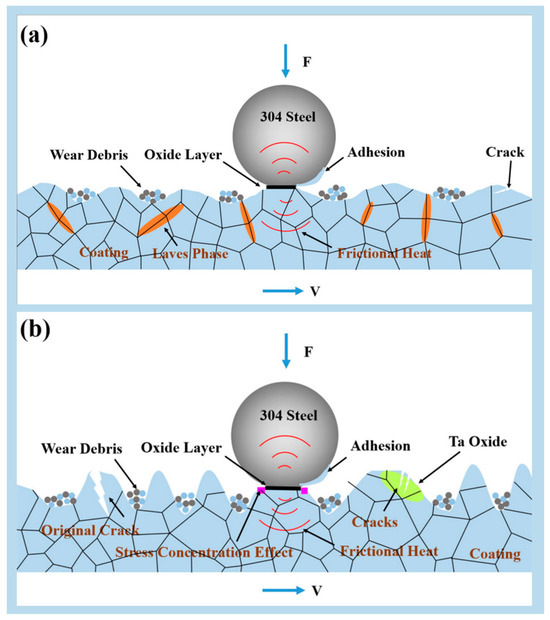

4.3. Wear Mechanism of Cr-Ta Coatings

The wear mechanism of the Cr-Ta coatings can be comprehensively understood through microstructural characterization and wear behavior analysis. As illustrated in Figure 10, the coatings exhibit distinct wear characteristics depending on their composition and microstructure. Microstructural observations and EDS results reveal that the Cr-Ta coatings undergo both adhesive wear and oxidative wear during the sliding process. The high hardness of the coatings minimizes plastic deformation and tearing at the contact interface, with only a small quantity of abrasive debris accumulating at the wear edge [39]. The frictional heat generated at the interface further provides the energy needed for the coating material to react with oxygen, facilitating the occurrence of oxidation wear.

Figure 10.

Schematic of wear behavior: (a) Cr-10Ta coating; (b) Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings.

For the Cr-10Ta coating, the presence of a hard Laves phase (Cr2Ta) provides substantial structural support during rubbing, as confirmed by XRD analysis. The coating exhibits a high dislocation density (Figure 8b,c), which strengthens dislocation interactions and enhances wear resistance. Additionally, the fine-grained structure of the coating (Figure 8d) plays a crucial role in its tribological performance. The high density of grain boundaries effectively hinders dislocation motion, improving resistance to plastic deformation and reducing material loss. When relative motion occurs between the coating surface and the friction counterpart, the shear fracture of the micro-protrusions on the coating surface takes place, leading to the material transfer from one surface to the other and, subsequently, the production of adhesive wear. Due to the structural support from the hard Laves phase and the strengthening of the material by the high dislocation density, the weight loss of the coating during adhesive wear is relatively minor. Moreover, grain boundaries alter crack propagation paths by deflecting cracks and increasing the energy required for their advancement, resulting in only superficial cracks (Figure 2b). The fine-grained structure also contributes to low surface roughness, reducing the actual contact area between friction pairs and minimizing stress concentration, as supported by the analysis in Figure 9.

In contrast, the Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings exhibit different wear behaviors due to their inherent microstructural characteristics. As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, these coatings contain pre-existing cracks that become stress concentration sites under frictional loading. When relative motion occurs between the coating and the friction counterpart, adhesive spots are prone to forming in the stress concentration regions, thereby increasing the wear. The large grain size and low grain boundary density (Figure 8(d2,d3)) further weaken their ability to impede crack propagation, leading to accelerated wear and the formation of wear debris. Additionally, XRD results indicate that the brittle Ta oxides in these coatings are prone to microcracking during rubbing, deteriorating their tribological properties (Figure 6h) [17]. The increased surface roughness (Figure 9) exacerbates stress concentration at micro-convex contact points, further intensifying wear. The higher surface roughness reduces the contact area, which increases stress concentration and accelerates the detachment of material during adhesive wear, further exacerbating the wear resistance.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the microstructure, mechanical properties, and tribological performance of Cr-Ta coatings with varying Ta contents (10 at.%, 25 at.%, and 40 at.%) were systematically investigated. The key findings are summarized as follows:

- The Cr-10Ta coating exhibits superior microstructural integrity, featuring a dense microcrystalline structure with metallurgical bonding to the CrNi3MoVA steel substrate, and it is primarily composed of the hard Cr2Ta Laves phase and Fe-Cr solid solution. In contrast, the Cr-25Ta and Cr-40Ta coatings exhibit cracks, for they are dominated by brittle Ta oxides and Fe-Cr solid solution.

- All Cr-Ta coatings significantly improve the mechanical properties of the substrate, as quantified by enhanced hardness and elastic–plastic deformation resistance parameters (H/E, H/E2, and H3/E2), among which the Cr-10Ta coating exhibits optimal mechanical performance, with a hardness of 6.35 GPa and the highest values for all elastic–plastic deformation resistance parameters.

- The tribological evaluation reveals that all Cr-Ta coatings substantially enhance the wear resistance of CrNi3MoVA steel, with adhesive wear and oxidative wear being the predominant mechanisms. The Cr-10Ta coating exhibits the lowest friction coefficient (approximately 0.4) and minimal wear loss (0.29 mg) and wear rate.

- The exceptional wear resistance of the Cr-10Ta coating can be attributed to its optimized microstructure, including high dislocation density, fine-grained microstructure, low surface roughness, and the reinforcing effect of the hard Laves phase, which collectively inhibit crack propagation and reduce material removal, making it a highly promising material for demanding wear-resistant applications.

Author Contributions

F.G.: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Validation. K.W.: Formal analysis, Visualization. F.L.: Formal analysis. L.Z.: Formal analysis. C.G. (Chang Gong): Validation. F.Z.: Writing—review and editing. M.D.: Methodology, Software. G.Z.: Data curation, Resources. C.G. (Cean Guo): Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision. J.Z.: Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support of the Research Project of Application Foundation of Liaoning Province of China (No. 2022JH2/101300006), the Research Project of Education Department of Liaoning Province of China (LJKMZ20220604 and 1030040000675), the Special Fund of Basic Scientific Research Operating Expense of Undergraduate Universities in Liaoning Province (LJ212410144077), the Light-Selection Team Plan of Shenyang Ligong University (SYLUGXTD5), the Foundation of National Key Laboratory for Remanufacturing and the Key Laboratory of Weapon Science & Technology Research (LJ232410144071), and the financial support of the Key R&D Project of the Joint Science and Technology Program of Liaoning Province (2025JH2/101800434).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Fengsheng Lu and Lei Zhang were employed by the North Huaan Industry Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Pei, W.; Pei, X.; Xie, Z.; Wang, J. Research progress of marine anti-corrosion and wear-resistant coating. Tribol. Int. 2024, 198, 109864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiawei, F.; Yanze, L.; Shiyu, C.; Haoyu, W. Review of Damage Mechanism and Life Improvement Methods of Large Caliber Gun Barrel. Equip. Environ. Eng. 2022, 19, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazovik, I.N.; Ashurkov, A.A. Powder gas diffusion into the surface layer of the aviation quick-firing gun barrel. Russ. Aeronaut. 2007, 50, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, P.J.; Todaro, M.E.; Kendall, G.; Witherell, M. Gun bore erosion mechanisms revisited with laser pulse heating. Surf. Technol. 2003, 163, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polášek, M.; Krbaťa, M.; Eckert, M.; Mikuš, P.; Cíger, R. Contact Fatigue Resistance of Gun Barrel Steels. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2023, 43, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopok, S.; Rickard, C.; Dunn, S. Thermal-chemical-mechanical gun bore erosion of an advanced artillery system part two, Modeling and predictions. Wear 2005, 258, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, P.J.; Kendall, G.; Todaro, M.E. Laser pulse heating of gun bore coatings. Surf. Technol. 2001, 146, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Cean, G.; Jian, Z. Research Progress of Cr, Ta and Cr-Ta Alloy Coating on the Inner Wall of Gun Barrel. Mater. Rep. 2025, 39, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiyan, L.; Cean, G.; Quan, L.; Yunhuan, W.; Lang, Z. Preparation and properties of tantalum-chromium amorphous alloy coatings by magnetron sputtering. J. Shenyang Ligong Univ. 2022, 41, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Spiak, W.A.; Janz, G.J. Electrodeposition of tantalum and tantalum-chromium alloys. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1981, 11, 11291–11297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.C.; Chen, Y.I.; Kao, H.L. Annealing of sputter-deposited nanocrystalline Cr-Ta coatings in a low-oxygen-containing atmosphere. Thin Solid Films 2012, 520, 6929–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Akiyama, E.; Habazaki, H.; Kawashima, A.; Asami, K.; Hashimoto, K. The Corrosion Behavior of Sputter-Deposited Amorphous Cr-Nb and Cr-Ta Alloys in 12-M HCL Solution. Corros. Sci. 1993, 34, 1947–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Akiyama, E.; Habazaki, H.; Kawashima, A.; Asami, K.; Hashimoto, K. An XPS study of the corrosion behavior of sputter-deposited amorphous Cr-Nb and Cr-Ta alloys in 12 M HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 1994, 36, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cean, G.; Zongke, Z.; Shuang, Z. High-speed Friction and Wear Performance of Electrospark Deposited AlCoCrFeNi High-entropy Alloy Coating. Mater. Rep. 2019, 33, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, C.; Casavola, C.; Pappalettera, G.; Renna, G. Advancements in Electrospark Deposition (ESD) Technique: A Short Review. Coatings 2022, 12, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cean, G.; Jian, Z.; Guangming, G.; Shiqiang, Y. Study on the properties of Cr coating on the surface of gun steel by electrospark deposition. J. Shenyang Ligong Univ. 2013, 32, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijun, W.; Guanglin, Z.; Fengsheng, L.; Lei, Z.; Yuanchao, W.; Shuang, Z.; Cean, G.; Jian, Z. Friction and wear performance of an electrospark-deposited Ta coating on CrNi3MoVA Steel. Mater. Technol. 2024, 58, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.X.; Guo, C.A.; Lu, F.S.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.J.; Xu, Z.Y.; Zhu, G.L. Influence of deposition voltage on tribological properties of W-WS2 coatings deposited by electrospark deposition. Chalcogenide Lett. 2023, 20, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, D.W.; McClanahan, E.D.; Lee, S.L.; Windover, D. Properties of thick sputtered Ta used for protective gun tube coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2001, 146, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyбaшевски, О. Phase Diagrams of Binary Iron-Based Systems; Metallurgy: Moscow, Russia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Y.; Shiqiang, L.; Xuan, X. Effects of Mo on microstructure and fracture toughness of Laves phase TaCr2 alloys. Trans. Mater. Heat Treat. 2017, 38, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, J.; Xiang, Y. Feasibility of preparing Mo2FeB2-based cermet coating by electrospark deposition on high speed steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 296, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roostaei, M.; Tabrizi, A.T.; Aghajani, H. Predicting the wear rate of Alumina/MoS2 nanocomposite coating by development of a relation between lancaster coefficient & surface parameters. Tribol. Int. 2024, 191, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, J.; Wang, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, J. Electrofluid in-situ forming MoS2-TiO2 lubricant-hard alternate coatings sintered at different temperatures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 477, 130367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Tang, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, Z.; Lin, H. Important contributions of metal interfaces on their tribological performances: From influencing factors to wear mechanisms. Compos. Struct. 2024, 337, 118027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Cao, H.; Chen, X.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, G. Enhanced tribocorrosion performance of laser-deposited Fe2CoNiCrAlTiCx high-entropy alloy coatings via in-situ graphitization in aqueous medium. Corros. Sci. 2024, 236, 112221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xia, H.; Shang, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Fu, Y.; Xu, J.; Dong, L. Interfacial engineering reaction strategy of in-situ Cr23C6/CoCrFeNi composites with network structure for high yield strength. Materialia 2024, 38, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Ma, T.; Yang, X.; Tao, J.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Vairis, A. In-situ investigation on dislocation slip concentrated fracture mechanism of linear friction welded dissimilar Ti17(α+β)/Ti17(β) titanium alloy joint. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 872, 144991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, G.; Chen, K.; Zhang, H.; Guo, N.; Xu, L. Impact of microstructure evolution on the corrosion behaviour of the Ti-6Al-4V alloy welded joint using high-frequency pulse wave laser. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4300–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, J.; Yang, Y.; Sun, J.; Yu, K.; Luo, Z. Synergistic enhancement of AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy coating through Laves phase and ceramic phase collaboration. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 491, 131192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Li, L.; Rong, Y.; Tan, C.; Wang, F. Microstructure and mechanical properties of ZrB2 ceramic particle reinforced AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy composite materials prepared by spark plasma sintering. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 45311–45319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasi, R.; Gallo, S.C.; Attar, H.; Taherishargh, M.; Barnett, M.R.; Fabijanic, D.M. The effect of phase constituents on the low and high stress abrasive wear behaviour of high entropy alloys. Wear 2024, 556, 205531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liang, H.; Jiang, L.; Qian, L. Effect of nanoscale surface roughness on sliding friction and wear in mixed lubrication. Wear 2023, 530, 204995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Lei, S.; Zhang, M. The friction and wear behavior of Cu/Cu-MoS2 self-lubricating coating prepared by electrospark deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 270, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, S.H.; Gulzar, A.; Saleem, S.; Wani, M.F.; Sehgal, R.; Yakovenko, A.A.; Goryacheva, I.G.; Sharma, M.D. Advances in development of solid lubricating MoS2 coatings for space applications: A review of modeling and experimental approaches. Tribol. Int. 2023, 192, 109194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Atheaya, D.; Tyagi, R.; Ranjan, V. High temperature friction and wear of atmospheric plasma spray deposited NiMoAl-Ag-WS2 composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 455, 129225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyland, A.; Matthews, A. On the significance of the H/E ratio in wear control: A nanocomposite coating approach to optimised tribological behavior. Wear 2000, 246, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslin, D.L.; Oliver, W.C. A new method for analyzing data from continuous depth-sensing micro indentation tests. J. Mater. Res. 1990, 5, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, G.; Sun, D.; Chen, L.; He, J.; Wang, S.; Xie, F. Cultivating a comprehensive understanding of microstructural attributes and wear mechanisms in FeCrCoNiAlTix high-entropy alloy coatings on TC6 substrates through laser cladding fabrication. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 984, 173865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.