Abstract

In practical applications, steel storage racks include a wide range of beam-to-column connections (BCCs), which have a significant impact on their structural stability, particularly under various loading conditions. This systematic review focuses on the application of the finite element method (FEM) as a complementary tool to evaluate the mechanical behavior of these connections. Key parameters that influence connection performance include the connector’s class and hook configuration, column thickness, beam height and weld position on the connector. Although the Eurocode 3 standard provides design guidelines for connections, experimental testing remains the most reliable method due to the complexity of semi-rigid connections, particularly in the context of pallet racks. Validated FEM analysis emerges as a dependable and cost-effective alternative to experiments, enabling more detailed parametric studies and improving the prediction of structural response. This review focuses on the advantages of FEM integration into design workflows via quantitative synthesis, while also emphasizing the role of contact formulations in modeling accuracy. To establish FEM as an independent predictive tool for the design and optimization of steel storage racks, future research should focus on cohesive zone modeling, ductile damage criteria, advanced contact strategies and additional machine learning (ML) techniques.

1. Introduction

This review synthesizes key findings from the literature to evaluate the effectiveness of the potential independent usage of FEM in analyzing semi-rigid connections. Pallet racks, as part of warehouse equipment, are of enormous importance for the organization and location of stored products. Storage of any type of item is made possible by their configuration and design, making them highly adaptable to different needs, which increases their popularity. Pallet racks, depending on type, can be organized in blocks or rows with aisles in warehouses. Arranging them in such a way allows for appropriate access to each unit load. A crucial aspect of organized storage is the reliable and quick accessibility of items. That is why several types of racks can be used to optimize warehouse efficiency, while their layout ensures that the structural reliability of pallet racks depends primarily on the performance of all existing connections under various loading conditions. Due to the nature of pallet racks, which are typically made from cold-formed thin-walled steel sections [1], conventional welded or bolted joints from a long time ago have been replaced by semi-rigid, boltless connections that improve efficient assembly and reduce cost while maintaining structural performance. Given the relatively short history of thin-walled racking profiles, their research is still in the phase of intensive expansion [2]. The chronological trend in research approaches is evident: the earliest contributions focused predominantly on analytical formulations that idealize the behavior of semi-rigid connections. As pallet rack technology evolved, analytical models were followed by experimental testing, which became the dominant research method. Special attention was given to experimental tests of different types of connections, as well as a numerical analysis of their behavior. Numerous studies confirm that the existing models do not provide sufficient precision in order to predict connection behavior, highlighting the need for further optimization and improvement of the current design, analyses and standards. Accordingly, the European standards, including Eurocode 3 [3], the European Materials Handling Federation (FEM) [4] and EN 15512 [5] define general design criteria that are applicable to adjustable storage systems, and provide procedures to characterize their moment rotation response. Only in recent years has FEM gained importance, and current research trends show a clear shift toward using FEM as an independent method that is capable of estimating behavior, performing parametric optimization and predicting failure modes without extensive experimental testing in the future. Therefore, the literature review primarily focuses on studies published within the last 20 years, as advances in numerical modeling during this period have led to more precise and reliable results. Although older studies exist and are acknowledged, they are not analyzed in detail due to the increase in the development of numerical analysis in current practice. Analyzed articles were examined in terms of their approach (experimental, FEM, analytical) and classified accordingly in further sections. However, discrepancies between FEM and experiments remain, primarily due to limitations in contact modeling, fracture simulation and simplifications of boundary conditions. These gaps highlight the need for a systematic review that identifies the critical parameters and proposes advanced modeling strategies.

Studies [6,7,8,9,10,11,12] relied on experimental tests, FEM and simplified analytical models to predict the structural response. Key parameters such as column thickness, connector configuration and beam height affect connection flexibility and load-bearing capacity [13,14]. Failure modes vary with column thickness, ranging from perforation tearing in thin columns to tab cracking in thicker ones, as well as connector configuration [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Hooks and perforations were consistently identified as the most sensitive elements. Regarding research on global analysis, it is worth mentioning the work by Bernuzzi et al. [21,22,23,24,25], who demonstrated the key role of the warping degree of freedom in pallet racks, as well as the influence of floor deflection. Recent studies [26,27,28] utilize beam elements that already incorporate warping in their analyses. Trouncer and Rasmussen [29,30] experimentally investigated thin-walled steel rack frames and developed numerical models that demonstrate how standard calculations neglect the effect of local instability. Research on experimental and numerical analysis demonstrated their importance, since authors concluded that each type of weld significantly affects the capacity and ductility of connections [31,32,33,34,35]. Dumbrava and Cerbu [36] demonstrated that the effect of looseness in BCCs can cause discrepancies in the calculation of deflections, while Taranu et al. [37] analyzed the behavior of perforated columns under the axial load, confirming that buckling primarily depends on slenderness.

In addition to permanent static and variable loading, such as the weight of stored goods and their placement method, seismic performance is also important, as cyclic stress reduces stiffness and energy dissipation capacity. Seismic considerations are addressed separately in EN 16681 [38], based on Eurocode 8 [39]. This phenomenon and the progressive weakening of the connection have been demonstrated through experiments, highlighting the significance of ductility in earthquake design. Moreover, Yin et al. [40] highlighted that the speed-lock bolt connections exhibit low initial stiffness, while Jovanovic et al. [41] represented a new hysteresis model, with only four parameters successfully describing their behavior under cyclic loading. Due to significant geometric and material nonlinearity, accurate modeling necessitates experimental validation, with a focus on the explicit connection dependency of elements such as beams and beam-end connectors (BECs) [42].

Beyond mechanical loads, thermal effects also play a critical role in connection performance. Building upon this, a high-temperature study was conducted, demonstrating that semi-rigid BCCs lose approximately 40% of their initial stiffness when exposed to elevated temperatures, while others confirm the reliability of FEM in thermal responses [43,44]. Liang et al. [45] examined how the temperature of cold-formed steel structures affects energy efficiency and explores design strategies to reduce that loss.

Although the primary focus of this review is on semi-rigid BCCs, it is important to acknowledge the role of baseplate connections in the response of the rack structure too, as demonstrated by Yazici [46]. Recently, Fragassa et al. [47] highlighted the continuous evolution of metals and their significance in modern industry. Moreover, Shah et al. [48] showed that the ML model can predict the M-θ behavior of boltless connections with good accuracy, achieving FEM and reducing the need for expensive experimental testing. Additionally, Ganasan et al. [49] confirmed that ML, especially support vector machine (SVM) models, can be useful tools for material utilization and to improve safety, recommending larger datasets and integration of FEM simulations. Even in the comparison of American and European standards [50,51,52], the static load-bearing capacity of steel pallet racks was analyzed, with a focus on the influence of different design methods.

Overall, the literature confirms that FEM provides valuable insights into stress distribution and failure modes, yet discrepancies remain due to limitations in contact modeling and fracture simulation. Experimental validation continues to be essential, with FEM enabling parametric optimization and predicting failure modes with reduced cost. The aim of further research is to establish FEM as an independent and predictive tool that is capable of replacing extensive experimental testing in the future. To achieve this, future studies should focus on the development of cohesive zone modeling, ductile damage criteria and advanced multi-point contact formulations, while complementary approaches such as ML may further enhance FEM accuracy. The scientific contribution of this review lies in systematically identifying critical parameters: column thickness, connector class, hook configuration, beam height, weld position and connecting them to observed failure modes and FEM prediction accuracy. By integrating comparative analyses and highlighting discrepancies between FEM and experiments, the review establishes methodological gaps and proposes cohesive zone modeling and ductile damage criteria as future directions. This structured approach advances the state of the art by positioning FEM not merely as a validation tool but as a potential independent method for the design and optimization of rack connections.

2. Design Principles and Classification of Beam-to-Column Connectors

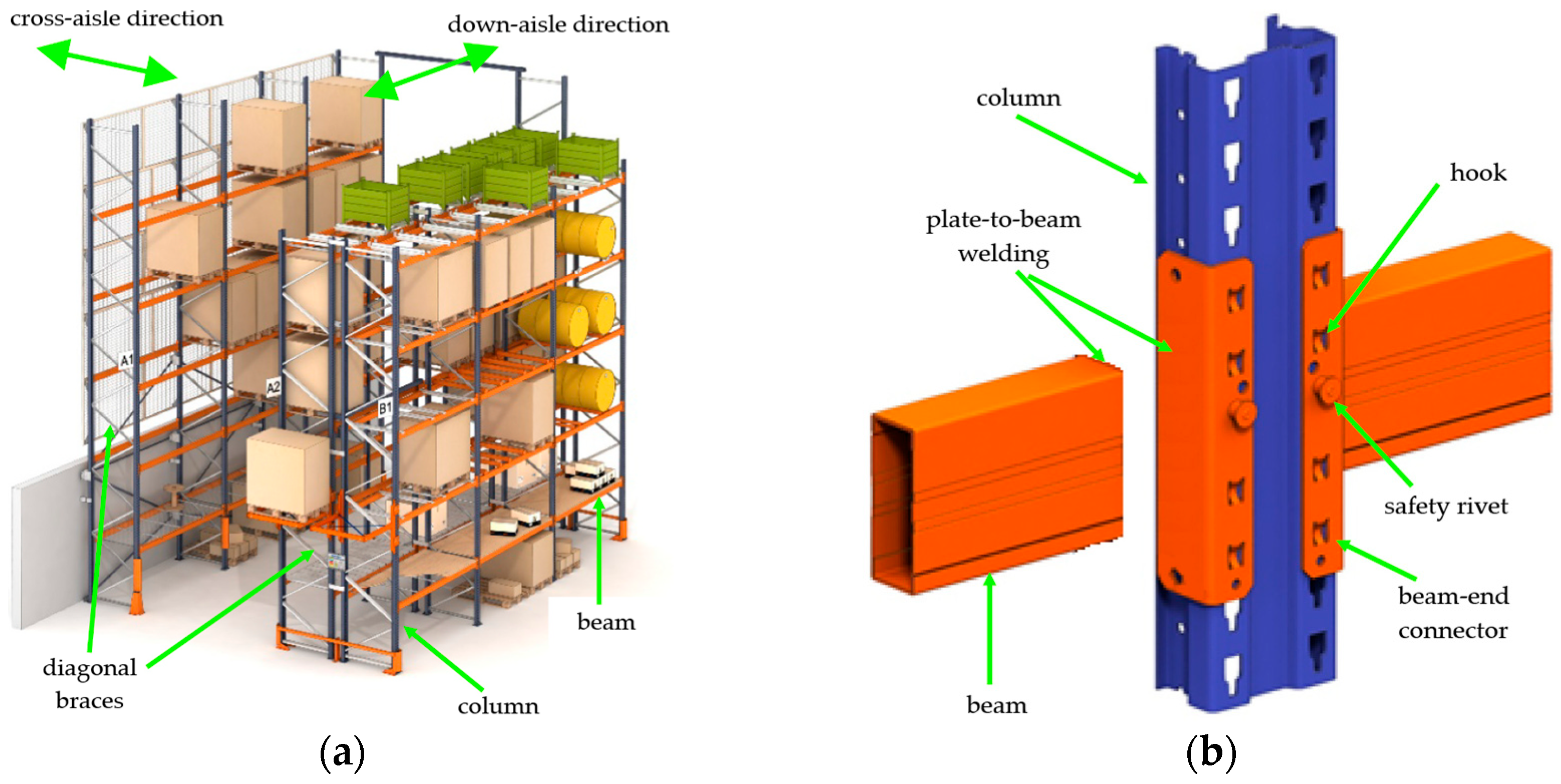

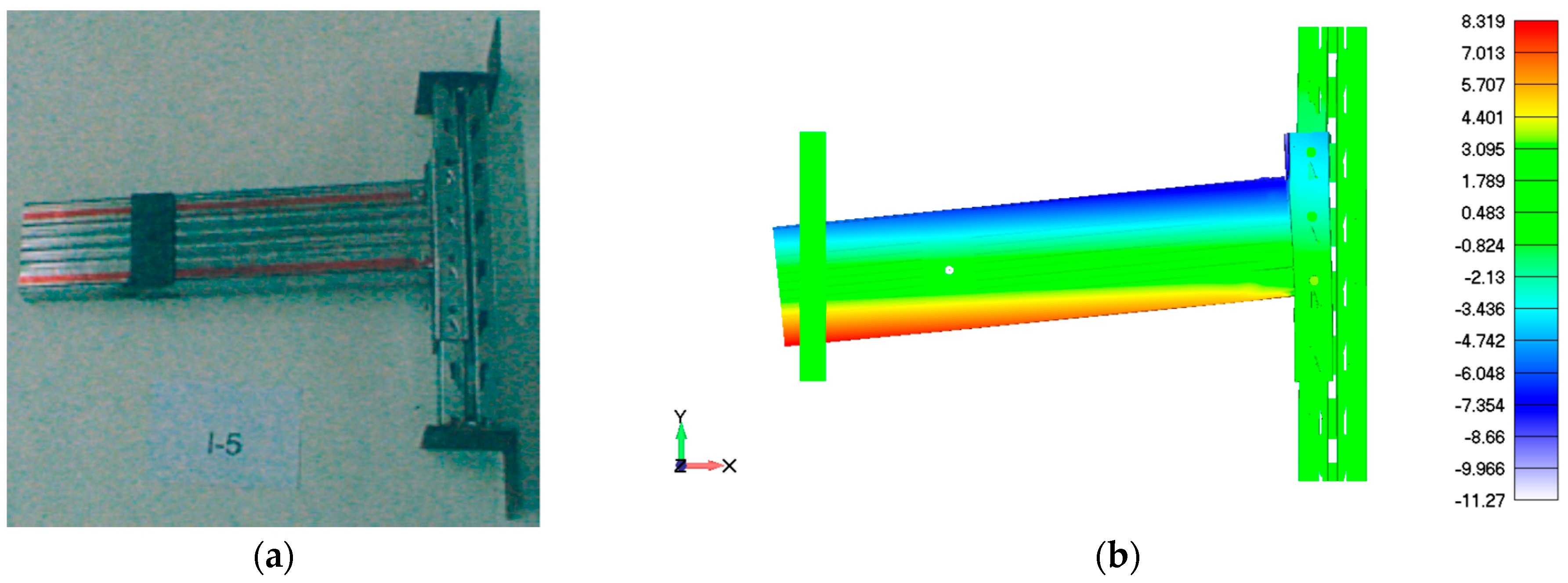

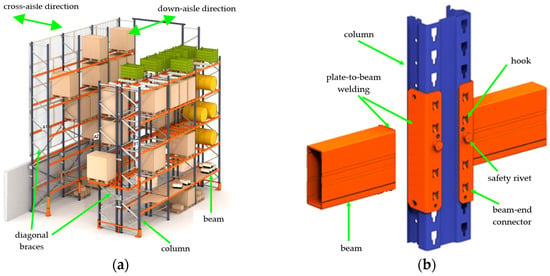

The primary components of these racks include vertical elements such as columns, horizontal elements such as front and rear beams and horizontal and/or diagonal braces, as shown in Figure 1a. The longitudinal direction that goes parallel to storage aisles is called the down-aisle direction, while the transverse one is the cross-aisle direction. An element that is not completely rigid and, as such, significantly affects the global stability of the structure is the BEC, as illustrated in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

Rack structure: (a) overall configuration, (b) beam-to-column connection (reprinted with permission from Ref. [35]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier).

However, apart from the regular service function of BCCs, limitations in resistance to lateral and seismic loads make them vulnerable to local buckling, splitting of the column perforation, or weakening due to cyclic loading. This is precisely why Eurocode 3 and related European standards, such as EN 15512 [5], define the design and testing criteria for connections in storage systems under common conditions, as well as EN 16681 [38], under seismic.

Classification of Semi-Rigid Beam-End Connectors

Semi-rigid connections occupy an intermediate position between fully rigid and pinned, transmitting moments and forces. Their mechanical behavior, previously discussed in the context of experimental and numerical studies, strongly depends on parameters such as column thickness, connector class and joining method, which are emphasized due to their critical role in structural performance.

Elements that provide the stable spatial structure are an essential part of every type of rack. They are categorized into basic and additional elements. The basic elements are as follows:

- Vertical frames;

- Horizontal beams;

- Baseplates with anchors;

- Spacers.

The frames’ horizontal and vertical bracing system ensures rack stability in the cross-aisle direction. Connectors between beams and columns are a unique component that is welded or otherwise made to be an integral part of the beam. They have special elements that are placed into the column’s perforation, such as tabs, studs or hooks. Consequently, the rigidity of the BCC guarantees the stability of the rack in the down-aisle direction.

As the basic elements are required for a rack, additional components can be installed depending on the storage type, load characteristics and operational requirements. This can include protections, back stoppers, additional stiffeners, crossbars with various profiles, sheet metal inserts, etc. Although secondary in function, these components significantly influence the system’s structural behavior by enhancing its overall stability, redistribution of internal loads and improving resistance to local deformations and buckling. Their presence is hard to consider and almost impossible in the existing standard experimental evaluation, while numerical analysis can easily ensure accurate prediction of rack performance with them under operating conditions. Besides the above-mentioned additional stiffeners, residual stresses and profiling imperfections have also been identified as influential factors that affect the stability and strength of semi-rigid connections [1,45].

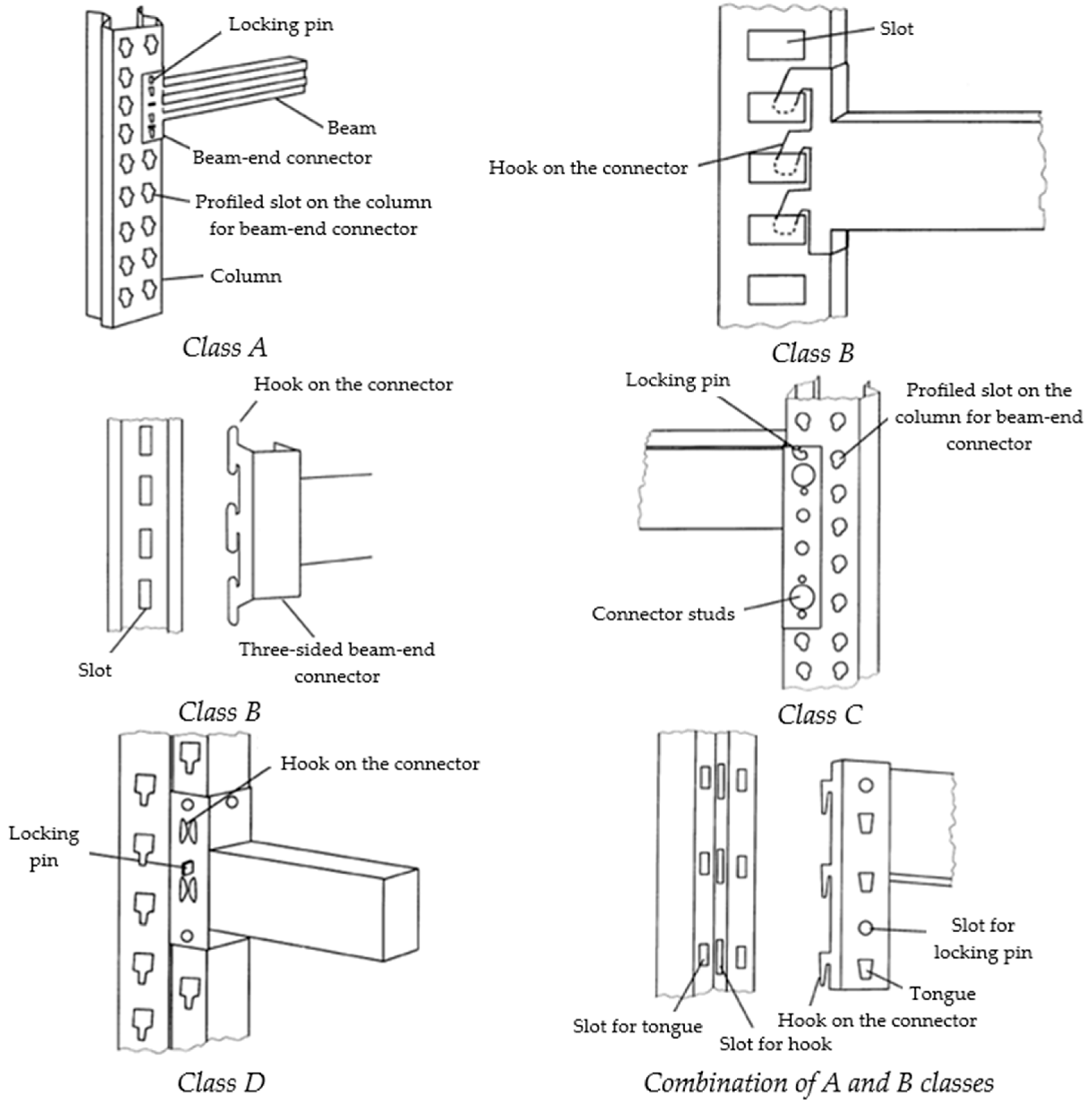

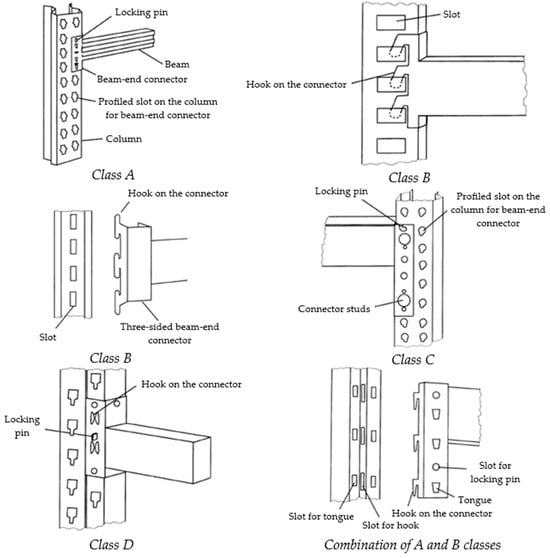

The construction of BEC consists of hooks that fit into the properly spaced holes in the column–column perforation. It also enables the connection of the beam with the vertical frame, and as concluded in [53], perforations have a significant impact on stress distribution and torsional stiffness. To prevent connection failure, a safety rivet, or so-called locking pin, is incorporated as an additional safety element. BECs can be divided into four classes, as defined in [2], as shown in Figure 2 and experimentally analyzed in [54,55]:

Figure 2.

Classification of beam-end connectors with connection elements (reprinted with permission from Ref. [2]. Copyright 2023, Faculty of Engineering, University of Kragujevac).

- Class A—tongue and groove construction. This type of construction has an integrated tab, formed through a punching operation on the BEC; during assembly, the BEC makes contact with the column rib at the front and with the column baseplate at the side.

- Class B—construction obtained by punching with a press. A press-punch operation is used to form this type of connector; by joining the rib and the BEC in parallel, a two-sided contact is achieved; if the joint is formed perpendicular to the rib, a three-sided contact is achieved between the column and the connector.

- Class C—construction with a built-in stud. The punched holes in the BEC are created using a pressed pin assembly, which replaces the hooks found in other connector types; the connection is established with the column leg and rib.

- Class D—construction of a double-integrated hook. The clips are formed through a punching process, allowing contact with the column at two points; the hooks are located on only one side and a connection is made with the rib and column baseplate.

To achieve multiple contacts in the vertical direction, certain classes can be combined. An important element used with each connector class is the previously mentioned locking pin. It prevents the potential movement of the beam from its intended position.

3. Overview of Semi-Rigid Beam-to-Column Connections

This chapter integrates the overview of experimental testing, analytical approach and broader numerical analyses, as well as the seismic assessment as a distinct and critically important loading condition, as explicitly addressed in special provisions of Eurocode 8 [39], to comprehensively characterize semi-rigid BCCs in rack structures. The focus is on unifying them to gain a holistic understanding of their mechanical behavior. Although experimental testing remains fundamental for validation, and as analytical solutions are unreliable, numerical models provide an essential framework for the simulation of complex phenomena and conducting parametric studies.

3.1. Experimental Evaluation of BCCs

As previously emphasized throughout the manuscript, experimental testing of semi-rigid BCCs in pallet racks plays a key role in understanding their behavior under various loads [56,57]. Their mechanical behavior is described through the nonlinear response, which defines the connection’s flexibility and capacity for energy dissipation. Experimental tests confirm a typical three-phase response: an initial linear-elastic segment, followed by nonlinear deformation and the formation of a plastic hinge at high rotations [20,35,58]. This characteristic progression is also illustrated in Figure 6.1c, in Eurocode 3, part 1–8 [3], where the curve clearly separates the following phases:

- Linear elastic phase—represented by the initial stiffness of the joint, determined by the slope of the curve at low rotations, shown with dependence on Figure 6.1c as ;

- Nonlinear deformation phase—beyond the elastic limit, plastic deformations occur in the BEC and the column, resulting in the formation of a plastic hinge; this phase allows for continued rotation while maintaining load capacity, as shown in Figure 6.1c as ;

- Cancelation phase—occurs when stress values exceed the joint’s capacity, potentially leading to failure mechanisms, as shown in Figure 6.1c as .

Unlike idealized pinned or rigid joints in classic structural analysis, these connections exhibit semi-rigid behavior, which is characterized by distinct experimental phases. Local yielding, geometric imperfections and connector deformation influence this response [15,16,54].

The importance of experimental testing, both single and double cantilever, for reliable prediction of the BEC stiffness has been demonstrated in studies [6,7,8]. Building on this, extensive experimental research was conducted, confirming that BEC geometry and beam height significantly influence joint behavior [9,12]. Król et al. [15] further demonstrated that boltless connections, known for their quick installation and high ductility, can dissipate significant energy under cyclic loading but tend to exhibit local column damage at elevated moment levels. In a broader parametric study [59], 16 samples were experimentally tested, concluding that column thickness, beam height and number of hooks are the primary geometrical parameters that affect cyclic behavior, with the number of hooks being identified as the most influential. Typical failure modes observed in experiments include the following:

- Splitting of column perforations in thin profiles.

- Cracking of connector hooks in thicker profiles.

- Pulling out the BEC from the column perforation.

- Localized bending of the beam near the connection zone.

The specific failure type closely depends on the weld position and assembly strength, which degrade under various loads. Since ductile failure provides structural advantages by enabling energy dissipation and delaying failure, stronger welds are recommended. This aligns with the “strong column–weak beam” principle that is commonly used in seismic design. Conversely, complete connection failure can affect column instability and lead to displacement of the unit load, thereby increasing the overall structural risk.

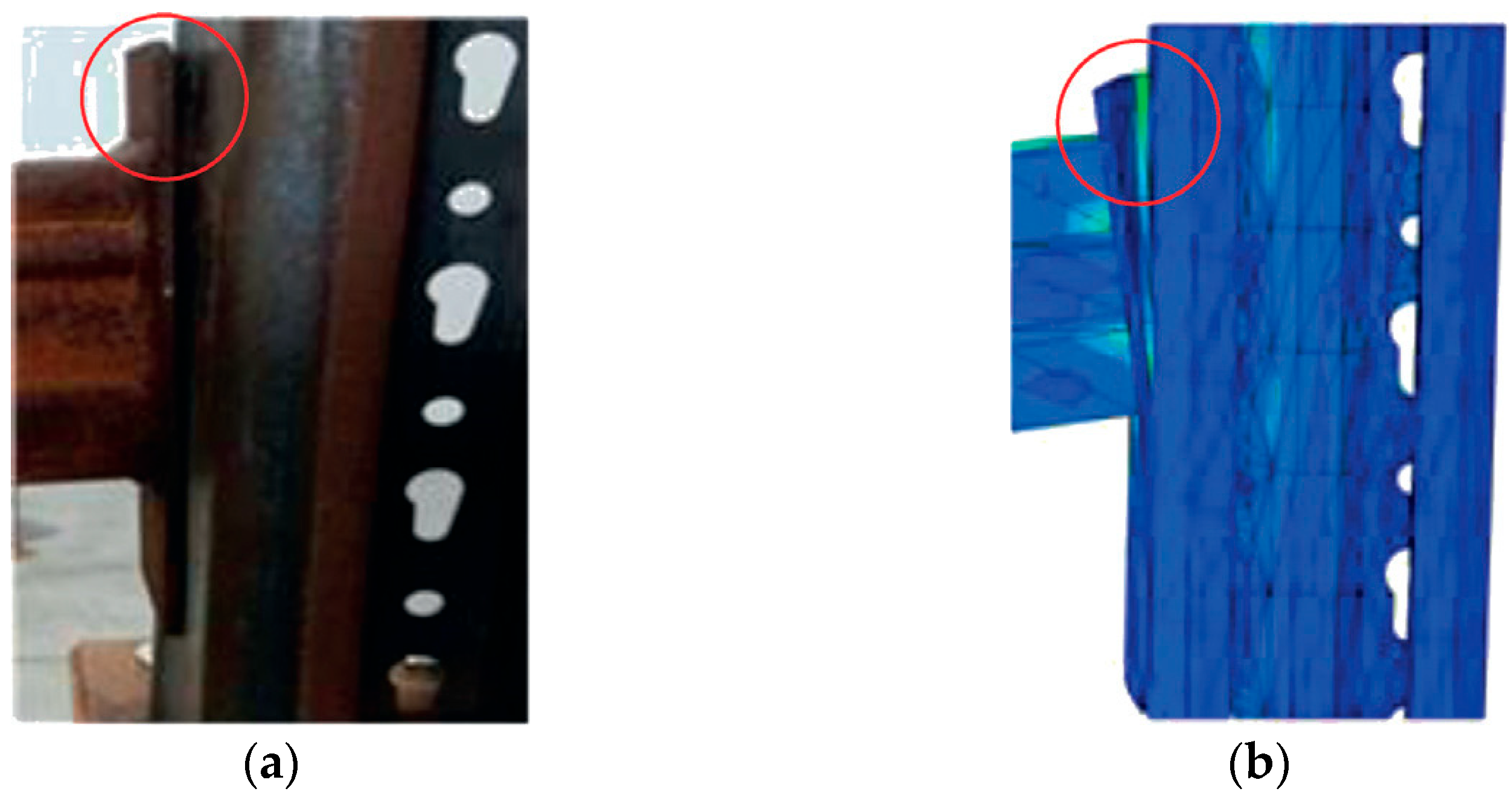

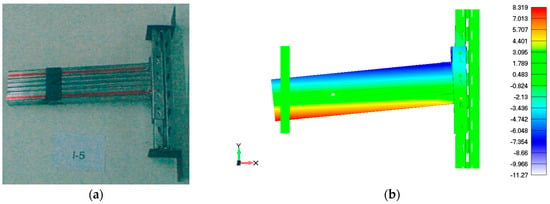

To illustrate the specific failure modes and deformations observed during monotonic and cyclic tests on cold-formed semi-rigid BCCs, Figure 3 and Figure 4 present representative examples of classes A and D, respectively, which were selected for their clarity and diagnostic relevance. Slęczka and Kozłowski [60] conducted single and double cantilever tests on several BCC samples, varying in beam height and depth. They aimed to propose the component method as an additional method that evaluates each parameter separately, emphasizing their critical aspects, such as tabs in shear, connectors in bending and shear and the column perforation in tearing. Localized yielding and rotation in the panel zone of connection under monotonic loading is shown in Figure 3a, indicating the onset of plastic hinge formation. As a result of concentrated stresses near the BEC, Figure 3b shows the deformation of the column perforation obtained experimentally in [61], characterized by localized plasticity.

Figure 3.

Experimental deformation of class A connection under single cantilever test in the following: (a) the panel zone of a steel rack connection (reprinted from Ref. [60]). (b) Column perforation and hooks (reprinted with permission from Ref. [61]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier).

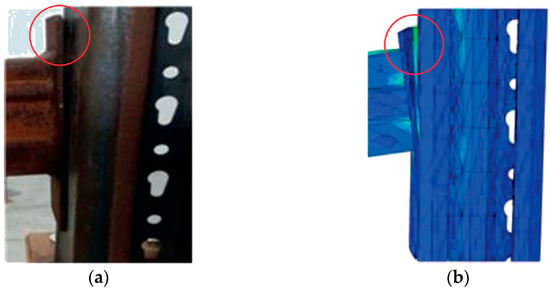

Figure 4.

Failures of class D connection in single cantilever tests: (a) brittle failure due to sliding of the hooked assembly; (b) ductile failure due to weld rupture (reprinted with permission from Ref. [33]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier).

To further analyze, López-Almansa [33] researched the critical elements of rack structures and identified the main connections that affect the structural response, including BCCs and baseplate connections, and identified two primary bending failures. A brittle failure mode observed during cyclic testing is presented in Figure 4a. It shows tearing of the hooks and column perforation, marked with arrows, which is caused by sliding and stress concentration at the BEC, highlighting the sensitivity of thin-walled profiles under cyclic loading. In contrast, ductile failure mode is characterized by the cracking of a welded connection between beam and connector, as shown in Figure 4b, also indicated by an arrow. This comparison demonstrates the importance of weld position to achieve ductile behavior and delay connection failure.

These results confirm the influence of several parameters on connection performance and provide a basis for understanding deformation modes. Based on various experimental tests [8,35,40,62,63], it can be concluded that the most sensitive elements during the experiment are hooks and column perforation. Building upon these findings, Gusella [64] conducted monotonic tests and demonstrated that the BEC contributes more to the overall rotational capacity than either the column or the beam. Yazici et al. [65] systematically examined the influence of the weld position between the beam and the connector on the behavior of boltless connections. The weld position was described as having the greatest influence on the moment capacity, stiffness and ductility, while column and beam geometry was of secondary importance. The optimal weld position was determined to be farther from the top of the connector, resulting in a better force balance and a lower risk of local failure. The paper thus emphasized the significance of the weld position while also pointing to future research for FEM optimization and ML models.

As previously discussed, although experimental assessments offer valuable insight into the physical response of semi-rigid connections, they are often limited by cost, time and scalability. Accordingly, the following section explores analytical approaches to interpreting connection behavior and to deriving simplified design models, as defined in related standards for storage systems [3,5].

3.2. Analytical Approach of BCCs

To better align with the experimental data, multi-linear and polynomial models are often used instead of traditional bilinear representations. The Frye–Morris polynomial model is widely used for predicting initial stiffness, while power-law models provide improved predictions of ultimate moment capacity [9,19,66,67]. It is based on an odd-power polynomial representation of the curve, as follows:

where

- —Relative rotation.

- —Curve-fitting constants, obtained in experimental test.

- —Parameter which scales the ordinate of curves, depending on geometrical and mechanical characteristics.

- —Moment of rotation.

In some cases, the slope of the curve can become negative for some values of M. This may cause difficulties in analyzing semi-rigid BCCs, using the tangent stiffness formulation. To solve that problem, a formulation for parameter K is given in the following:

where

- —Geometric parameters of connection.

- —Coefficients obtained to give a good fit to the curve.

Several authors [32,66,67,68] used this model, while Zhao and Yehia [69,70] presented a mechanical model to predict initial rotational stiffness, considering key deformable components: tab bending, column wall bearing and bending, BEC bending and shear and column web shear. Validation against experimental results provided a satisfactory agreement. In study [61], the methodology involved statistical processing of experimental data and a series of tests on 36 samples to propose a modified Ramberg–Osgood model that connects the geometry of the connection with its mechanical performance. Aguero et al. [71,72] provided general analytical models for plastic design of thin-walled sections under different combinations of internal forces, with practical recommendations for Eurocode standard improvements. This contribution was complemented by the development of analytical–numerical methods to access the load-bearing capacity of class 4 thin-walled sections, taking into account bi-moment effects. These methods were validated using FEM, broadening the existing approaches.

Following on from insufficient analytical formulations, the next section introduces FEM as a tool for simulating complex joint behavior. Therefore, numerical simulations tend to become an indispensable tool for the analysis of semi-rigid connections under various loading conditions, due to their ability to predict, visualize and improve the performance of BCCs.

3.3. Numerical Analysis of BCCs

Since experimental tests can be expensive and time-consuming, numerical and analytical models provide a practical alternative for analyzing the behavior of semi-rigid connections, especially in pallet racks. It is evident that analytical modeling still faces limitations to fully capture the complexity of connection behavior. For this reason, the following section emphasizes representative studies that visually compare the experimental results with FEM simulations, highlighting the strengths and limitations of numerical approaches.

These examples are chosen not for their relative importance, but for their clarity in illustrating stress distribution and failure modes, enhancing their interpretability and model validation. Numerical analyses have also proven to be effective in analyzing complex phenomena such as local buckling, distortional instability and connection flexibility [31,36]. Abdel-Jaber performed a numerical study and then verified it through analytical and experimental tests on stiffness, measuring the vertical deflection of beams and horizontal deflection of BECs [73,74].

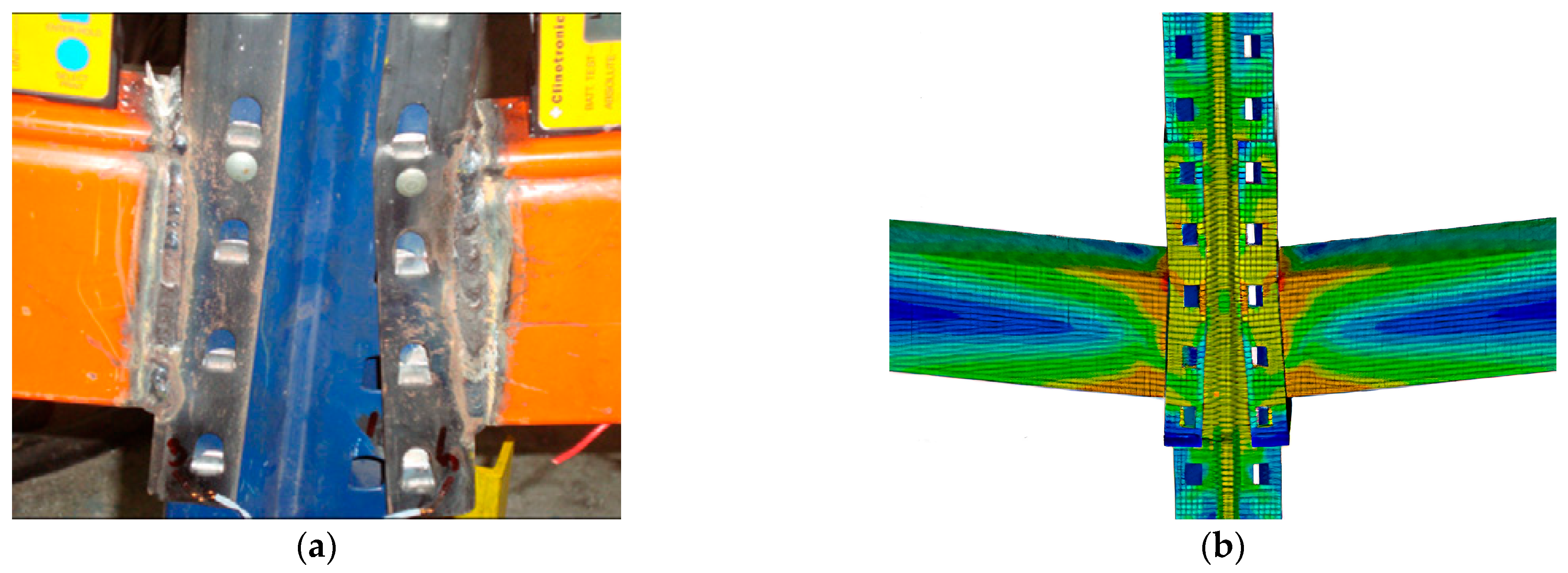

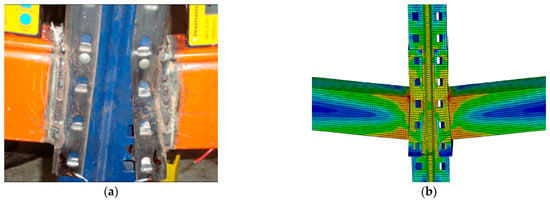

Prabha et al. [9] conducted 18 experimental tests on boltless, semi-rigid BCCs class A, with varying column thickness, BEC depth and beam height. Increasing the column thickness from 1.8 mm to 2.5 mm resulted in up to a 63% improvement in moment capacity, while increasing the beam height from 100 mm to 150 mm led to an increase of 53% in moment capacity and up to 71% in initial stiffness. Furthermore, an increase in the number of hooks from four to five led to a noticeable increase in stiffness and strength. The experimental test shown in Figure 5a represents the deformation of connector class A and progressive damage of the column under load. The FEM simulation of the same configuration, as shown in Figure 5b, illustrates the equivalent stress distribution and deformation contours. The numerical model used a frictionless surface-to-surface contact formulation, using S4R, shell 4-nodal elements, to present a realistic connector-to-column interaction. FEM resulted in a discrepancy in moment capacity below 5%, while rotational stiffness varied more significantly, reaching up to 20% depending on BEC geometry and column thickness. This discrepancy is primarily due to the absence of fracture modeling, which led to a slight overestimation of the moment capacity and failed to capture the localized tearing of the column perforation, especially progressive failure initiated at hooks, and a sudden load drop was observed experimentally. Nevertheless, the numerical results confirmed consistent qualitative agreement in the elastic and early plastic phases, making the FEM suitable for parametric studies and stiffness estimation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the connection failure class A in double cantilever test: (a) experimental test resulted in hook deformation and tearing of the column perforation; (b) FEM simulation of the same failure mode, illustrating the stress concentration zones and deformation contours. (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [9]. Copyright 2010, Elsevier).

Shah et al. [17] compared graphs from experimental and numerical analyses of four samples, highlighting the general compatibility between the results, although significant differences in the ultimate moment capacity were observed because FEM predicted less intense perforation failure. Increasing the number of hooks proves more effective than connector thickness for enhancing the performance. Furthermore, the welding position of the joint between the beam and the BEC also affects connection behavior, with down-welding improving uniform stress distribution and thus connection durability, while up-welding promotes premature failure. The result of the experimental test and deformation of the connector class A under load, with visible hook displacement and column distortion, is shown in Figure 6a. The corresponding FEM model, shown in Figure 6b, replicates the same boundary conditions and loads and illustrates the stress distribution and deformation contours. A frictionless surface-to-surface contact definition, implemented with C3D8R continuum 8-nodal elements, was used, which successfully identified the stress concentration zones and failure modes. A quantitative comparison revealed that FEM overestimated the moment capacity by 3–8% and stiffness by up to 23%, especially in thinner profiles. Despite simplifications in contact modeling and the absence of fracture representation, FEM remains a robust framework for evaluating connection stiffness and geometric sensitivity.

Figure 6.

Comparison of double cantilever test for connector class A: (a) experimental setup, showing the physical deformation of BCC; (b) FEM simulation, replicating the same boundary conditions and loading scenario. (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [17]. Copyright 2016, Elsevier).

In a related study [18], the same comparison approach revealed that the connector thickness and the number of hooks significantly affect the moment capacity and initial stiffness, with hooks identified as the primary source of potential failure modes. In [41], a new four-parameter hysteresis model, called the steel rack joint (SJR), was presented and it satisfactorily described the behavior of the BCC under cyclic loading. Giordano et al. [54] identified the pinching in the hysteresis loop, which emphasizes the differences in the cyclic response of the class A–B connection compared to traditional steel structures. Relying on that, Gusella et al. [55] analyzed the pinching effect in detail through numerical simulation, taking into account the degradation of the rotational stiffness and its importance when describing behavior.

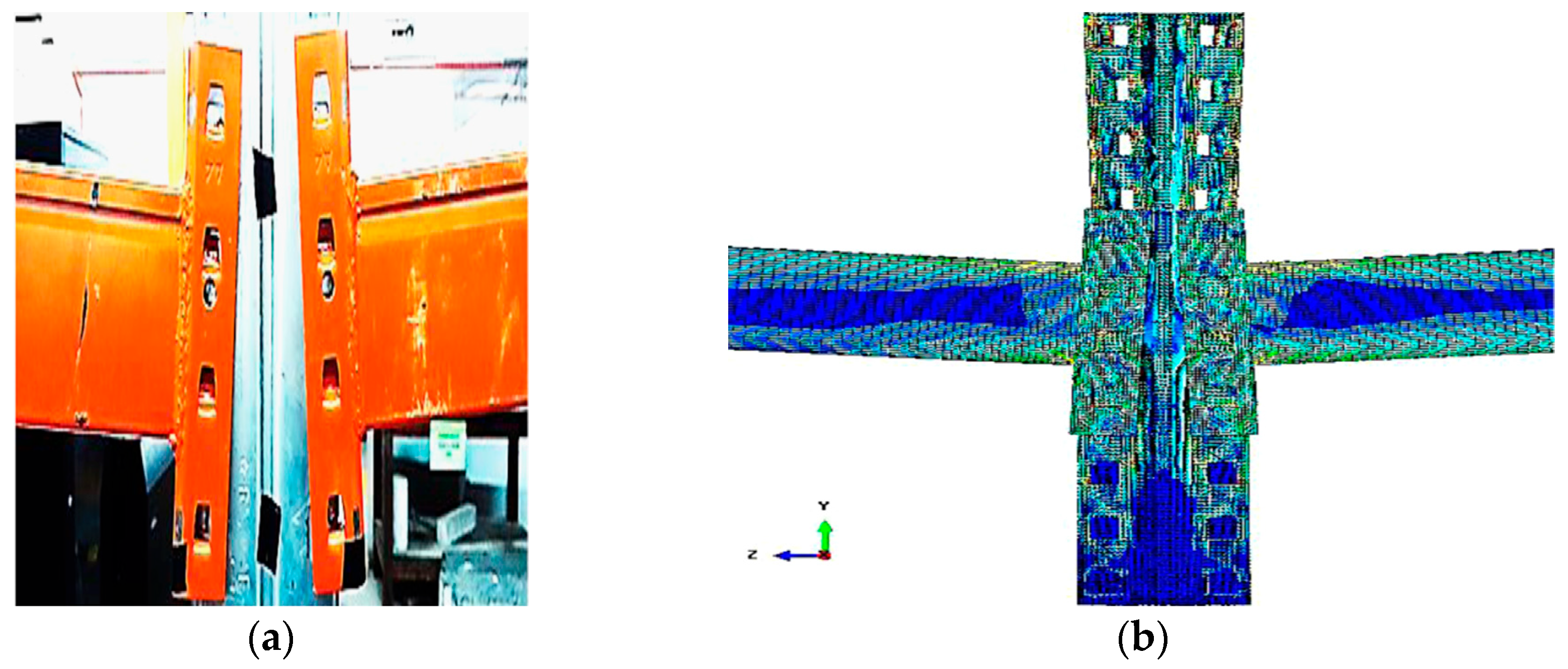

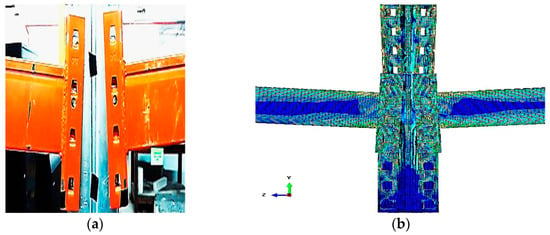

Vujanac et al. [32] used the single cantilever test to investigate the deformation of a test sample and compared it with the corresponding numerical model. When geometric change was combined with a transition from three to four connector hooks, improvements became significantly more pronounced. This indicates that a greater beam height, followed by thicker columns, enhances the moment capacity and initial rotational stiffness of the connection. The experimental deformation of a connector class A–B under cyclic loading is presented in Figure 7a. It highlights the failure initiation at the hooks and progressive tearing of the column perforation. The FEM model presented in Figure 7b shows the simulation of the equivalent loading conditions, including material nonlinearity and surface-to-surface contact formulation using three-dimensional 8-nodal finite elements, providing visual confirmation of critical stress zones and ductile response. Although the FEM model successfully reproduced the overall deformation and stress distribution, a quantitative comparison revealed measurable discrepancies. The ultimate moment capacity was on average 3–5% higher in simulations. An increase in beam height, with constant column thickness, led to a 20% increase in rotational stiffness and bending strength. While not intended to be a scaled representation, the validated model offers practical insight into connection behavior and serves as a reliable tool for comparative and early-stage design guidelines.

Figure 7.

Comparison of single cantilever test for connector class A–B: (a) experimental deformation of connection; (b) FEM simulation of connection deformation (reprinted from Ref. [32]).

A detailed numerical analysis of the dynamic behavior of BCCs in steel pallet racks was carried out in [75], focusing on the influence of geometric parameters such as the thickness of the BEC and the gap between the column and the connector. Miranda [76] numerically evaluated the behavior and stiffness of BCCs used in industrial storage system structures using FEM simulation, based on the prescriptions of the Rack Manufacturing Institute (RMI). The numerical model employed a node-to-surface contact formulation to ensure the interaction between beam and column. The numerical and experimental failure modes coincided and the difference between the connection stiffness values obtained numerically and experimentally was less than 10%.

Building on the findings of [77], the influence of various parameters in boltless BCC class C was examined through a single cantilever bending test. The experimental test shown in Figure 8a from [78] by the same author demonstrates the progressive deformation of connector studs under cyclic loading, followed by localized tearing around the column perforation. The same failure mechanism in FEM is illustrated in Figure 8b, including stress concentration zones and connector failure, where the maximum deformation is indicated by a red circle. While earlier studies relied on node-to-surface formulations, using SHELL163 elements for the beam, column and connector, and SOLID45 elements for studs with frictional surface-to-surface contacts in this research reflects the advancement of numerical modeling techniques, further validating FEM as a reliable tool for parametric studies. Therefore, this research identified the column thickness, beam height and connector geometry as the primary factors that affect ductility and stiffness, with quantified variations of 10% and 15%, respectively.

Figure 8.

Comparison of failure mode in single cantilever test for connector class C: (a) experimental deformation of connection; (b) FEM simulation of the same deformation (Reprinted from Ref. [78]).

Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 clearly demonstrate the progress in finite element technology and contact formulations as a visual comparison of FEM simulations with experiments. The transition from solid and shell elements and node-to-surface contact formulations to more advanced surface-to-surface contact definitions and hybrid element strategies demonstrates numerical modeling’s ability to capture both overall stiffness and localized failure modes. But currently, experimental testing remains essential to characterize connection behavior through characteristics. Consequently, validated numerical models, whose significance is enhanced by comparison with the experimental data, fill this gap, enabling an efficient assessment of how geometry, material properties and connection configuration affect performance, thereby providing engineers’ reliable tools for design optimization.

Compared to conventional models, the data-driven approach produced a prediction of stiffness that more closely aligns with the experimental and FEM results, as confirmed by static loading tests in [79]. Santamaria et al. [80] demonstrated that including detailed parameters, such as hook–slot interactions, beam height and weld position, enhances the predictive accuracy of the initial stiffness in boltless connections. In [81], standard connections were compared against hybrid versions with additional bolts, focusing on the rotational stiffness of BCCs through experimental and numerical analyses. Unlike standard approaches that define stiffness based on connection properties, Hou et al. [82] proposed a classification method in which bracing stiffness is explicitly taken into account when determining the rotational stiffness required to model BCCs as rigid.

Beyond static analyses, the influence of seismic on semi-rigid BCCs requires special attention due to its critical impact on structural performance, which is why, as previously mentioned, it is given as a separate part in Eurocode standards, while elevated temperatures, whether as incidental or potential operational conditions, are also addressed for their impact on connection behavior. The energy dissipation capacity of BCCs is notable but insufficient to prevent structural damage during major earthquakes [5,83]. The influence of design parameters on seismic activity was quantified [84,85], while [86] demonstrated that the mass factor is not a representative parameter for racks exposed to earthquakes. A numerical study on seismic response was conducted by Álvarez et al. [87]. Consequently, the European Standard EN 16681 [38] expands upon Eurocode 8 [39] by enforcing stricter requirements for pallet racks in seismic regions. Comparative studies between American and European design codes reveal significant differences in load capacity assessments, highlighting the impact of the design methodology, geometric parameters and rotational stiffness of connections [50,51,52,88]. This confirms the future viability of the FEM as an independent framework. The aim to rely solely on the FEM is to reduce the cost and complexity connected to extensive experimental testing, simultaneously achieving reliable predictions of connection behavior.

3.3.1. Summary of Influential Parameters

This section summarizes the key findings from previous studies on semi-rigid BCCs in pallet racks, highlighting the influence of dominant parameters, as follows:

- Connector class.

- Column thickness.

- Beam height.

- Number of hooks.

- Weld position.

To enhance comparative analysis, two summary tables are provided that highlight the most influential parameters examined across the literature. As part of the broader review, Table 1 represents studies that explicitly investigate the variations in the connection configuration that are relevant to the observed failure modes.

Table 1.

Classification of investigated connector classes and influential parameters.

The studies presented in Table 1 show that the connector class consistently governs the failure mode, with hooked configurations, e.g., [6,7,12,17], leading to perforation tearing or connector distortion. Class A is the most common because it is widely used in industry. Other classes (A–B, B, C, D) appear sporadically, mostly in studies examining specific performances or comparing alternative configurations. Column thickness strongly influences where failure initiates, such that thinner columns cause tearing near perforation, while thicker ones shift failure toward the connector [16,20,62]. Beam height affects stiffness and moment capacity, with higher beams delaying failure onset and redistributing deformation zones, as analyzed in [12,16,80]. The number of hooks affects load distribution and rotational restraint, thereby influencing failure modes and energy dissipation capacity [9,17,63]. Weld position, although rarely analyzed, can change stress paths and crack initiation zones [12,17,77,80]. A quantitative overview of each analyzed parameter, based on frequency and reported impact across recent studies, is provided in Table 2. Percentages were calculated based on the total number of studies listed in Table 1. For example, 88% for column thickness indicates that 27 out of 31 studies explicitly analyzed this parameter. Furthermore, while each analyzed study used a specific type of connector, their influence was assumed to be 100%, so each type was assigned by its own influence.

Table 2.

Influence of parameters on failure modes in semi-rigid BCCs.

The comparative analysis confirms that the connector class is the most consistently examined parameter, addressed in all studies, as it directly governs the failure mode. Column thickness was identified as critical in 88% of cases due to its strong influence on deformation mechanisms. Beam height and number of hooks also show significant impact on stiffness and failure progression, with 76% and 64%, respectively. Only 12% of studies analyzed weld position, because it is usually a fixed position in standard connector designs and varies that requires precise geometric control and further testing. The few studies that examine it highlight its impact on crack formation and load redistribution. These findings support the priority of influential parameters’ optimization in future design and modeling, particularly to improve connection performance and structural reliability.

3.3.2. Summary of Comparative Experimental and Numerical Research

Numerous studies, through experimental tests and validation with FEM, showed that connection stiffness is generally more sensitive to parameters such as column thickness, beam height and number of hooks, than connector thickness. Hook failure, initiated by distortion and resulting in stress concentrations at the column perforation, was consistently identified as the primary failure mode, often followed by perforation tearing and BEC deformation in samples with thinner or fewer hooks. To support a clearer understanding of semi-rigid BCC behavior, Table 3 presents a structured overview of most relevant studies from the last two decades that combine an experimental test with FEM, or rely on FEM alone. Table 3 summarizes the applied methodology, main features and, where available, the quantified discrepancy between the experimental and FEM results.

Table 3.

Overview of studies on semi-rigid BCCs in pallet racks.

Although the FEM has proven effective in reproducing global deformation and moment capacity (approximately 10%) of semi-rigid BCCs, the most significant discrepancies remain in rotational stiffness (app. 23%), as expressed in Table 3. This is primarily due to the following factors:

- Simplified boundary conditions.

- The absence of initial geometric imperfections and residual stresses.

- Limitations in contact and fracture modeling.

Further research into contact formulations and modeling strategies is required to understand the main causes and improve prediction accuracy. The following section focuses on contact modeling issues, outlining the approaches of previous studies and their implications for reliable FEM analysis of semi-rigid BCCs.

Reviewed studies consistently demonstrate that local connection behavior leads to the global frame response of pallet racking systems. Rotational stiffness or early tearing at perforations reduces lateral stiffness and increases displacement at the system level, while improved ductile welds and influential parameters enhance the system’s response. Local mechanisms such as buckling, slipping or tearing impact global stability, load-bearing capacity and dynamic performance and thus cannot be considered independently. This underscores the importance of incorporating connection-level FEM models into frame-level analyses to ensure that design standards are adjusted to reflect the nonlinear and semi-rigid behavior observed experimentally and numerically.

3.3.3. Contact Modeling Issues

Contact modeling represents one of the most critical aspects of FEM analysis of semi-rigid connections. Shell elements are most commonly used for thin-walled columns, while solid elements are used for connectors and beams, with mesh refinement being concentrated on perforations and connector hooks. The finite element mesh is usually discretized with triangular and quadrilateral in 2D, and with tetrahedral and hexahedral in 3D elements, balancing efficiency and local accuracy. Material models are typically bilinear elasto-plastic, thus ignoring strain hardening and anisotropy. In addition to the quantitative differences between the FEM and the experiment given in Table 3, significant differences also exist in the way the contact is modeled. Table 4 provides an overview of element types and contact formulations used in the relevant research.

Table 4.

Overview of studies on element types and contact formulations.

As shown in Table 4, current FEM contact formulations mainly rely on surface-to-surface contact definitions, which provide stable solutions but remain limited when simulating multi-point contact and progressive damage. Advanced multi-point contact strategies, although not yet widely implemented in commercial FEM software, should be considered to improve the accuracy of BCCs modeling. Cohesive contact formulations, although not considered in analyzed studies, are increasingly applied due to their ability to simulate the fracture and tearing of perforations or weld rupture, while node-to-surface contact proves less accurate for larger contact areas and complex connections. It highlights the FEM’s growing ability to not only replicate general deformation patterns but also to provide reliable quantitative predictions, emphasizing the importance of improved element and contact formulations in closing the gap between experimental testing and numerical analysis.

Although numerical analysis traditionally relies on FEM-based software packages, it is important to briefly revisit, as previously mentioned, the limited but noteworthy part of the research that explores the analytical approach. Some authors [60,93,94] investigated an alternative approach through analytical models based on component methodology. In contrast to FEM-based modeling, Bonada et al. [90] proposed the application of generalized beam theory (GBT) for global analysis in the down-aisle direction, but due to the inability to accurately represent connections, it remains an adjunct to FEM analysis. Further examples of advanced analysis are presented in [95,96], where a detailed study of global ductility is conducted by using experimental and numerical push-over analyses, respectively, and calibrated against experimental curves. As a research method, FEM was proposed in [97] because it allows us to incorporate all design features and component connection in rack structures. Recent developments also include the integration of ML techniques to overcome limitations in traditional FEM frameworks. Small datasets limit the effectiveness of ML, despite its high potential. To address the lack of data, hybrid approaches combining ML with FEM simulations are becoming increasingly popular.

3.3.4. Machine Learning Approach

The growing need for ML in engineering has been highlighted in several studies. Shah et al. [48] developed an ML model that achieved accuracy compared to the FEM and reduced testing costs. Their research demonstrated that combining the SVM with signal decomposition improves reliability and makes this approach applicable across a variety of connection types. Gansan et al. [49] emphasized the reliability of ML models as predictive tools for optimizing material utilization and enhanced safety. Both studies analyzed SVMs and pointed out the limitations caused by restricted datasets, noting that the small number of experimental samples and limited design variations reduces the generalizability of ML models. Despite these challenges, Shah [48] showed that the enhanced SVM-DWT model can achieve reliable accuracy and outperform FEM predictions, indicating that careful parameter selection and methodological improvements allow ML approaches to remain effective even under limited data. To improve robustness, they recommended that future research expand datasets, include environmental factors and investigate hybrid ML simulation frameworks. In subsequent research, Gansan [98] concluded that the DT least square model provided the most accurate predictions of behavior, while the others, SVM Radial and DL Rectifier, were less consistent. He also highlighted the limitations of small datasets and restricted design variations, recommending broader input parameters and larger experimental bases. To supplement these findings, Etim et al. [99] conducted a comprehensive analysis of ML applications in structural engineering. Their review underscored both the promise and pitfalls of ML. Regardless of whether ML can accelerate simulations and improve prediction accuracy, its effectiveness is often with limited data. Hybrid approaches, such as the combination of the FEM with experimental results or integrating engineering guidelines into ML models, are increasingly recognized as viable solutions. Consequently, current research indicates that ML can reliably predict the response of boltless BCCs, even with limited datasets. However, their acceptance requires careful parameter selection, integration with engineering models and expansion of datasets to ensure practical relevance.

In a broader context, FEM studies on panel zone behavior show how local modeling of joint regions can have a significant impact on global frame performance [100]. Although these analyses are limited to seismic moment-resisting frames in buildings, rather than storage racks, they highlight the general importance of accurate local modeling assumptions in predicting the global structural response, which is especially important under extreme loading conditions such as seismic and thermal effects.

4. Discussion

The complex design of cold-formed semi-rigid BCCs arises from research into their mechanical behavior in specific pallet racking systems. Although these connections are widely used due to their affordability, flexibility and ease of assembly in steel structures, they present serious stability issues, particularly under combined static, seismic and thermal loads. This review emphasizes the need to further analyze semi-rigid BCCs as highly sensitive structural elements affected by all influential parameters.

Several analytical models, such as the Frye–Morris polynomial and the three-parameter power model, have been proposed to describe the response of semi-rigid BCCs. While accurate under specific conditions, their general applicability is often limited by variations in geometry and material properties. Experimental studies confirm that conventional linear models failed to describe nonlinear post-elastic behavior, whereas multi-linear formulations better represent plastic hinge formation and large rotations before failure. Therefore, boltless connections, despite lower initial stiffness, have shown promising potential for applications due to their capacity for energy dissipation. Connection efficiency improves not only with increased column thickness, beam height and number of hooks but also with optimized weld placement and improvement of the existing connector class. The significance of these parameters is further reinforced by the quantitative overview presented in Table 1 and Table 2, where various types of connector’s classes were examined in all studies and directly governed failure mode, while column thickness is identified as being critical in 88% of cases due to its role in perforation tearing. Beam height and number of hooks also show substantial influence—76% and 64%, respectively—confirming their contribution to stiffness enhancement and delayed failure.

Numerical simulations enable a more comprehensive understanding of connection behavior by analyzing the deformation effects and geometric imperfections that are often neglected in the mentioned simplified analytical models. Increases in beam height result in noticeable improvements in moment capacity and initial rotational stiffness. Another finding supported by the FEM is the impact of the welding position. Although the welding position is addressed in only 12% of studies, its effect on stress redistribution and crack initiation is notable, especially when the beam is welded farther from the top of the BEC. These parameters are not only critical for mechanical behavior but also directly influence the accuracy of FEM simulations. As shown in Table 3, most studies resulted in discrepancies below 10% for the ultimate moment capacity and up to 23% for rotational stiffness. They are correlated with the percentage of accurate modeling of connector’s class, column thickness, beam height and hook configuration. Studies that analyze these parameters aim to achieve better alignment between FEM and experimental results, confirming their role in structural performance and model reliability. These improvements, however, stop at specific boundaries, which indicates a nonlinear relationship that analyses using FEM could reliably detect. These insights support the importance of column, beam, connector and hook configuration in design optimization.

In addition to contact formulations, the choice of finite element type has proven to be equally important for the accuracy of FEM simulations. Shell elements offered efficiency in modeling thin-walled profiles but often underestimated localized tearing and fracture. Solid elements provided more realistic stress distribution and ductile response, though they tended to slightly overestimate the moment capacity and stiffness. Hybrid approaches, combining both types, as well as cohesive contact modeling, represent a more advanced stage of numerical modeling, enabling simultaneous representation of global stiffness and connection failure. This progression reflects the broader advancement of the FEM, where element technology and contact definitions together determine the reliability of simulations and their alignment with experimental results. Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 demonstrate how finite element formulations enhance the FEM’s ability to predict the connections’ behavior, confirming the effectiveness of advanced numerical modeling of semi-rigid connections.

Current FEM contact formulations mainly rely on surface-to-surface definitions, as shown in Table 4, which provide stable solutions but remain limited in simulating multi-point contact and progressive damage. Node-to-surface contact proves less accurate for larger contact areas, while cohesive formulations show promise in the simulation of fracture in perforations and welds. Advanced multi-point contact strategies that are not yet widely implemented represent a potential breakthrough for improving modeling accuracy. Beyond mechanical modeling, ML approaches have demonstrated the ability to predict M-θ behavior with good accuracy, reducing the need for experimental testing. These methods, when integrated with FEM, can enhance the predictive reliability and support optimization of the design parameters.

Despite the previously mentioned research, the current design standards, such as EN 15512 and EN 16681, still lack the precision necessary to predict connection behavior under different loading conditions, as concluded in [33]. By quantifying these variables through FEM and validating them against the experimental data, this review helps us to understand connections beyond generalized design assumptions. These findings suggest that rotational stiffness and failure modes are not merely dependent on material strength but also on the interactive behavior of contact surfaces, classes of BEC and analyzed influential parameters, which were identified as being dominant in over 75% of the reviewed studies. Therefore, parametric FEM modeling is not only cost-effective, but also essential for adapting design strategies to any rack configuration. Future research should therefore focus on cohesive zone modeling, ductile damage criteria and advanced multi-point contact formulations complemented by ML integration, to establish FEM as an independent predictive tool in the design of steel storage racks.

5. Conclusions

Over the past two decades, research on BCCs has evolved through three distinct phases: (1) early analytical studies that idealize moment–rotation behavior; (2) extensive experimental tests focused on identifying failure modes and mechanical behavior under various loads; and (3) the recent shift toward the FEM as a tool, to predict deformation mechanisms and optimize connector configuration. This review positions FEM modeling as a core methodological framework for analyzing complex interactions between contact surfaces and noticeable nonlinear responses in connection behavior. Existing design methodologies and simplified analytical models remain insufficient to describe the cyclic degradation, stiffness and potential failure modes observed in practice. While experimental studies remain essential, their limitation in cost and applicability make advanced numerical methods increasingly relevant. Therefore, the absence of a general analytical model for predicting moment–rotation behavior in various configurations, combined with the cost and complexity of experimental tests, highlighted the need for numerical analysis.

Numerical modeling enables a detailed analysis of how parameters and stress affect connection behavior, especially under cyclic loading and in the plastic deformation zone. This is supported by the quantitative synthesis presented in Table 1 and Table 2, where analyzed parameters were identified as being dominant in the reviewed studies. Consequently, increasing the column thickness and beam height most effectively enhances the moment capacity, while a greater number of hooks increase stiffness and delay failure. The optimal weld position and connector classes improve seismic resistance. These findings confirm their critical role in governing failure modes and rotational stiffness. Furthermore, comparisons between FEM simulations and experimental results, as presented in Table 3, show discrepancies below 10% for moment capacity and up to 23% for rotational stiffness, confirming the reliability of numerical modeling. In addition, the type of finite element has proven effective: shell elements offered efficiency for thin-walled profiles and solid elements provided more realistic stress distribution and ductile responses, while hybrid approaches enabled simultaneous representation of global stiffness and local connector failure. Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate how advances in element formulations have progressively enhanced the FEM’s ability to follow experimental results. Table 4 further emphasizes the role of contact formulations, showing that surface-to-surface contact dominates current practice, node-to-surface is less accurate for larger areas, cohesive formulations promise fracture simulation and multi-point strategies represent a crucial future direction. Based on these findings, several research directions are identified:

- Development of multiple contact modeling techniques, including friction, separation effects and stress concentrations to better reflect real connection behavior;

- Geometry-driven parametric studies, focusing on hook dimensions, column thickness, beam height, weld configuration and other geometric imperfections;

- Performance optimization under seismic and cyclic loading, identifying configurations that enhance energy dissipation and maintain post-yield stiffness;

- Cost-effective numerical modeling—FEM-based approaches provide designers and manufacturers with the opportunity to expand the existing product range or introduce new solutions without costly experimental testing, enabling broader parametric analysis and structural optimization;

- Experimental verification—while this review emphasizes numerical analysis, further research should focus on experimental validation of developed models, focusing on typical failure modes, cyclic degradation and the influence of dominant parameters;

- Since cheaper materials frequently result in thicker sections with simpler, less effective connections, while rising material costs lead to lightweight constructions with advanced connections, future research should examine how market trends affect connection design;

- The integration of cohesive zone models or ductile damage criteria into the FEM framework to better simulate rupture of column perforation;

- The quantitative effect of explicitly modeling weld geometry and heat-affected zones on predicting the failure mode;

- While this review provides the foundation for ML integration, with data in Table 3 offering precise guidelines for product refinement, the application of ML with the FEM could predict connection behavior during early-stage design; also, making these studies more accessible to a wider audience will improve their practical application;

- Although the European standards currently only accept the experimental methods for racking members, this review confirms that the other methods, like simulation by finite element with improvement and further development (it can already reproduce most of the parameters involved in the problem), can come close to the experimental results, or even reach them, which means that in the near future, supported with ML, it can become standard procedure for the racking element design to be the appropriate standard. The FEM currently uses less computer time than in the past, so it is easy to modify any parameter in the model, in order to investigate sensitivity factors or improve the design. All of this is in line with the current widespread availability of modern computer technology and software.

As mentioned above, the FEM is not yet an independent tool, but its ability to perform parametric optimization and reduce experimental costs positions it as a candidate for future independence. Advanced future research can establish the FEM as an independent predictive method for the design and optimization of semi-rigid steel storage rack connections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and R.V.; methodology, M.P.; validation, S.V. and N.M.; formal analysis, M.P. and R.V.; investigation, M.P. and R.V.; resources, M.P. and R.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P. and R.V.; writing—review and editing, M.P., R.V. and N.M.; visualization, S.V., M.B. and Z.D.; supervision, R.V., M.B. and Z.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCC | Beam-to-Column Connection |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| BEC | Beam-End Connector |

| ML | Machine Learning |

References

- Lee, Y.H.; Tan, C.S.; Mohammad, S.; Md Tahir, M.; Shek, P.N. Review on Cold-Formed Steel Connections. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujanac, R.; Miloradovic, N. Fundamentals of Storage and Transportation Systems, 1st ed.; Faculty of Engineering University of Kragujevac: Kragujevac, Serbia, 2023; ISBN 978-86-6335-102-8. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1993-1-1: 2005; Design of Steel Structures, Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings, Part 1-3: General Rules—Supplementary Rules for Cold Formed Thin Gauge Members and Sheeting, Part 1-8: Design of Joints. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- FEM 10.2.02; The Design of Static Steel Pallet Racking: Racking Design Code. Federation Europeene de la Manutention, Section X: West Bromwich, UK, 2001.

- EN 15512; Steel Static Storage Systems-Adjustable Pallet Racking Systems-Principles for Structural Design. CEN European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

- Bajoria, K.M.; Talikoti, R.S. Determination of Flexibility of Beam-to-Column Connectors Used in Thin Walled Cold-Formed Steel Pallet Racking Systems. Thin-Walled Struct. 2006, 44, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajoria, K.M.; Sangle, K.K.; Talicotti, R.S. Modal Analysis of Cold-Formed Pallet Rack Structures with Semi-Rigid Connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2010, 66, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangle, K.K.; Bajoria, K.M.; Talicotti, R.S. Stability and Dynamic Analysis of Cold-Formed Storage Rack Structures with Semirigid Connections. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2011, 11, 1059–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, P.; Marimuthu, V.; Saravanan, M.; Arul Jayachandran, S. Evaluation of Connection Flexibility in Cold Formed Steel Racks. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2010, 66, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangle, K.K.; Bajoria, K.M.; Talicotti, R.S. Elastic Stability Analysis of Cold-Formed Pallet Rack Structures with Semi-Rigid Connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2012, 71, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, R.M.M.; Zhang, P.; Alam, M.S. Investigation on Teardrop Connection of Rack Clad Building. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Civil, Structural and Transportation Engineering, Online, 17–19 May 2021; Avestia Publishing: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, C.; Arik, E.; Özkal, F.M. Influence of Design Parameters on Beam-to-Column Connections of Steel Storage Rack Systems. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 152, 107439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Simoncelli, M.; Venezia, M. Performance of Mono-Symmetric Upright Pallet Racks under Slab Deflections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2017, 128, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonada, J.; Pastor, M.M.; Roure, F.; Casafont, M. Distortional Influence of Pallet Rack Uprights Subject to Combined Compression and Bending. Structures 2016, 8, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, P.A.; Papadopoulos-Woźniak, M.; Wójt, J. Experimental Tests on Semi-Rigid, Hooking-Type Beam-to-Column Double-Sided Joints in Sway-Frame Structural Pallet Racking Systems. Procedia Eng. 2014, 91, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Sivakumaran, K.S. Flexural Behavior of Steel Storage Rack Beam-to-Upright Connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 99, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.N.R.; Ramli Sulong, N.H.; Khan, R.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Shariati, M. Behavior of Industrial Steel Rack Connections. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 70–71, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.N.R.; Ramli Sulong, N.H.; Khan, R.; Jumaat, M.Z. Structural Performance of Boltless Beam End Connectors. Adv. Steel Constr. 2017, 13, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridmehr, I.; Tahir, M.M.; Lahmer, T. Classification System for Semi-Rigid Beam-to-Column Connections. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2016, 13, 2152–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.; Prabha, P.; Rajasankar, J.; Iyer, N.R.; Raviswaran, N.; Nagendiran, V.; Kamalakannan, S.S. Cold-Formed Steel Pallet Rack Connection: An Experimental Study. Int. J. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2015, 7, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Gobetti, A.; Gabbianelli, G.; Simoncelli, M. Warping Influence on the Resistance of Uprights in Steel Storage Pallet Racks. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 101, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Pieri, A.; Squadrito, V. Warping Influence on the Static Design of Unbraced Steel Storage Pallet Racks. Thin-Walled Struct. 2014, 79, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Gobetti, A.; Gabbianelli, G.; Simoncelli, M. Unbraced Pallet Rack Design in Accordance with European Practice–Part 1: Selection of the Method of Analysis. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 86, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Gobetti, A.; Gabbianelli, G.; Simoncelli, M. Unbraced Pallet Rack Design in Accordance with European Practice–Part 2: Essential Verification Checks. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 86, 208–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Persico, D.; Simoncelli, M. Influence of Floor Deflections on the Performance of Steel Storage Pallet Racks. Eng. Struct. 2016, 123, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Simoncelli, M. EU and US Design Approaches for Steel Storage Pallet Racks with Mono-Symmetric Cross-Section Uprights. Thin-Walled Struct. 2017, 113, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gao, W.-L.; Liu, S.-W.; Pekoz, T.; Ziemian, R.D.; Crews, J. Dynamic Analysis and Seismic Responses of Industrial Rack Structures with Perforated Cold-Formed Steel Columns Using Line Elements. In Proceedings of the Cold-Formed Steel Research Consortium Colloquium, Online, 20–22 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.-W.; Pekoz, T.; Gao, W.-L.; Ziemian, R.D.; Crews, J. Frame Analysis and Design of Industrial Rack Structures with Perforated Cold-Formed Steel Columns. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 163, 107755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouncer, A.N.; Rasmussen, K.J.R. Ultra-Light Gauge Steel Storage Rack Frames. Part 1: Experimental Investigations. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 124, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouncer, A.N.; Rasmussen, K.J.R. Ultra-Light Gauge Steel Storage Rack Frames. Part 2—Analysis and Design Considerations of Second Order Effects. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 124, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena Cardoso, F.; Rasmussen, K.J.R. Finite Element (FE) Modelling of Storage Rack Frames. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 126, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujanac, R.; Miloradović, N.; Vulović, S.; Pavlović, A. A Comprehensive Study into the Boltless Connections of Racking Systems. Metals 2020, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Almansa, F.; Bové, O.; Casafont, M.; Ferrer, M.; Bonada, J. State-of-the-Art Review on Adjustable Pallet Racks Testing for Seismic Design. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022, 181, 110126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bové, O.; Ferrer, M.; López-Almansa, F.; Roure, F. Numerical Investigation on a Seismic Testing Campaign on Adjustable Pallet Rack Speed-Lock Connections. Eng. Struct. 2022, 252, 113653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bové, O.; López-Almansa, F.; Ferrer, M.; Roure, F. Ductility Improvement of Adjustable Pallet Rack Speed-Lock Connections: Experimental Study. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 188, 107015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrava, F.; Cerbu, C. Effect of the Looseness of the Beam End Connection Used for the Pallet Racking Storage Systems, on the Mechanical Behavior of the Bearing Beams. Materials 2022, 15, 4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranu, G.; Iacob, S.; Taranu, N. Buckling Behavior of Perforated Cold-Formed Steel Uprights: Experimental Evaluation and Comparative Assessment Using FEM, EWM, and DSM. Buildings 2025, 15, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16681; Steel Static Storage Systems-Adjustable Pallet Racking Systems-Principles for Seismic Design. CEN European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Eurocode 8; Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance-Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings. CEN European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- Yin, L.; Tang, G.; Zhang, M.; Wang, B.; Feng, B. Monotonic and Cyclic Response of Speed-Lock Connections with Bolts in Storage Racks. Eng. Struct. 2016, 116, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, Đ.; Žarković, D.; Vukobratović, V.; Brujić, Z. Hysteresis Model for Beam-to-Column Connections of Steel Storage Racks. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 142, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.N.R.; Sulong, N.H.R.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Shariati, M. State-of-the-Art Review on the Design and Performance of Steel Pallet Rack Connections. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 66, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.N.R.; Ramli Sulong, N.H.; Shariati, M.; Khan, R.; Jumaat, M.Z. Behavior of Steel Pallet Rack Beam-to-Column Connections at Elevated Temperatures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2016, 106, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyanayagam, A.D.; Keerthan, P.; Mahendran, M. Thermal Modelling of Load Bearing Cold-Formed Steel Frame Walls Under Realistic Design Fire Conditions. Adv. Steel Constr. 2017, 13, 160–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Roy, K.; Fang, Z.; Lim, J.B.P. A Critical Review on Optimization of Cold-Formed Steel Members for Better Structural and Thermal Performances. Buildings 2022, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, C.; Gürbüz, M.; Orhan, S.N.; Solak, K.; Özkal, F.M. Structural Performance of Different Baseplate Configurations in Storage Rack Systems. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 50, 13209–13223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragassa, C. Advances in Design by Metallic Materials: Synthesis, Characterization, Simulation and Applications. Metals 2021, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.N.R.; Hussain, S.F. An Optimized Machine Learning Based Moment-Rotation Analysis of Steel Pallet Rack Connections. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2021, 79, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganasan, R.; Abd Latif, M.F.; Mahyeddin, M.E.; Nagarajoo, K.; Hosen, M.A.; Nayaka, R. Machine Learning Applications in Structural Engineering: Prediction Models for Moment-Rotation Characteristics in Boltless Steel Connections. J. Adv. Ind. Technol. Appl. 2024, 5, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roure, F.; Somalo, M.R.; Casafont, M.; Pastor, M.M.; Bonada, J.; Peköz, T. Determination of Beam-to-column Connection Characteristics in Pallet Rack Structures: A Comparison of the EN and ANSI Methods and an Analysis of the Influence of the Moment-to-shear Ratios. Steel Constr. 2013, 6, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C. European and United States Approaches for Steel Storage Pallet Rack Design: Part 1: Discussions and General Comparisons. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 97, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Draskovic, N.; Simoncelli, M. European and United States Approaches for Steel Storage Pallet Rack Design. Part 2: Practical Applications. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 97, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C.; Montanino, A.; Simoncelli, M. Torsional Behaviour of Thin-walled Members with Regular Perforation Systems. ce/papers 2021, 4, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, S.; Gusella, F.; Lavacchini, G.; Orlando, M.; Spinelli, P. 03.20: Experimental Tests on Beam-end Connectors of Cold-formed Steel Storage Pallet Racks. ce/papers 2017, 1, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella, F.; Orlando, M.; Spinelli, P. Pinching in Steel Rack Joints: Numerical Modelling and Effects on Structural Response. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2019, 19, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrava, F.; Cerbu, C. Experimental Study on the Stiffness of Steel Beam-to-Upright Connections for Storage Racking Systems. Materials 2020, 13, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shi, L.; Shariati, M.; Toghroli, A.; Mohamad, E.T.; Bui, D.T.; Khorami, M. Behavior of Steel Storage Pallet Racking Connection—A Review. Steel Compos. Struct. 2019, 30, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Niu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Tang, G.; Deng, T.; Li, Z. Structural Performance of Speed-Lock Joints with Split Bolts in Steel Storage Racks. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 208, 107991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Dai, L.; Rasmussen, K.J.R. Hysteretic Behaviour of Steel Storage Rack Beam-to-Upright Boltless Connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2018, 144, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślęczka, L.; Aleksander, K. Experimental and Theoretical Investigations of Pallet Racks Connections. Adv. Steel Constr. 2007, 3, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourya, U.T.; Jayachandran, S.A. Moment-Rotation Model for a Range of Beam-to-Upright Connections in Cold-Formed Steel Storage Racks. Structures 2024, 66, 106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, M.; Tahir, M.M.; Wee, T.C.; Shah, S.N.R.; Jalali, A.; Abdullahi, M.M.; Khorami, M. Experimental Investigations on Monotonic and Cyclic Behavior of Steel Pallet Rack Connections. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 85, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Zhao, X.; Rasmussen, K.J.R. Cyclic Performance of Steel Storage Rack Beam-to-Upright Bolted Connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2018, 148, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella, F.; Lavacchini, G.; Orlando, M. Monotonic and Cyclic Tests on Beam-Column Joints of Industrial Pallet Racks. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2018, 140, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, C.; Gusella, F.; Özkal, F.M. Effect of Beam-to-Connector Weld Position on the Flexural Response of Boltless Rack Connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2026, 237, 110141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, P.; Marimuthu, V.; Jayachandran, S.A.; Seetharaman, S.; Raman, N. An Improved Polynomial Model for Top -and Seat- Angle Connection. Steel Compos. Struct. 2008, 8, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, P.; Rekha, S.; Marimuthu, V.; Saravanan, M.; Palani, G.S.; Surendran, M. Modified Frye–Morris Polynomial Model for Double Web-Angle Connections. Int. J. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2015, 7, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, C.; Martí, P.; Victoria, M.; Querin, O.M. Review on the Modelling of Joint Behaviour in Steel Frames. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Dai, L.; Wang, T.; Sivakumaran, K.S.; Chen, Y. A Theoretical Model for the Rotational Stiffness of Storage Rack Beam-to-Upright Connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2017, 133, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, M.; Gawwan, S.; Yehia, M.M. A Mechanical Model to Predict the Initial Stiffness of The Beam-to-Upright Connection in A Steel Pallet Racking System. Eng. Res. J. 2024, 183, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüero, A.; Baláž, I.; Höglund, T.; Koleková, Y. Plastic Design of Metal Thin-Walled Cross-Sections of Any Shape Under Any Combination of Internal Forces. Buildings 2024, 14, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguero, A.; Glauz, R.; Almerich-Chulia, A.; Kolekova, Y.; Martin-Concepcion, P. Resistance of Steel Sections (Classes 1 to 4) Including Bimoment Effects. Buildings 2025, 15, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]