Abstract

The Bayer process is used to extract alumina from bauxite, resulting in the formation of a highly alkaline solid residue known as bauxite residue (BR). However, such residue contains insufficient iron (<35% Fe) and complex impurity composition for use in blast furnace ironmaking. This study investigates the potential for enhancing the extraction of aluminium (Al) and increasing the concentration of Fe in residue by electrolytical reduction in suspension of BR in a spent Bayer process solution. A maximal current efficiency of 43.7% was obtained during the electroreduction of the coarse fraction of BR. The magnetite-containing residue obtained was further used as an aid in the high-pressure Bayer process leaching of gibbsitic bauxite. Adding the reduced BR increased the Al extraction rate by up to 7.2%. The kinetics of bauxite leaching at 120–160 °C and time interval 0–40 min in the presence of reduced BR were investigated using a shrinking core model (SCM). The results showed that the leaching kinetics of Al correlate well with the intraparticle SCM equation, indicating that the reaction velocity is regulated by the diffusion of the OH− or Al(OH)4− through the product layer. The apparent activation energy of the process at 140–160 °C was found to be 32.2 kJ/mol. Al in the solid residue is closely associated with Fe, i.e., it is enclosed in a solid matrix of iron minerals.

1. Introduction

The production of smelter grade alumina (Al2O3) from bauxite predominantly employs the Bayer process [1], the most widely adopted method of alumina refining worldwide. This process involves the alkaline high-pressure digestion of bauxite at temperatures between 140 and 270 °C [2,3,4]. This results in the formation of a slurry, which is then separated into a saturated aluminate liquor and bauxite residue (BR). The annual processing of bauxite exceeds 140 million tons worldwide, generating around 250 million tons of BR. This BR is currently accumulated in mud ponds at a rate of over 4 billion tons [5,6,7].

BR has a complex mineral composition, consisting mainly of iron (Fe) and titanium (Ti) oxides, as well as by-products of the leaching process [8]. As a result, BR also contains significant quantities of sodium (Na), aluminium (Al) and silicon (Si) [9]. To mitigate the loss of Na and Al during the process, lime is often added [10], although the low concentration of valuable components in BR makes its economic treatment challenging.

Several advanced methodologies are being investigated to address the BR problem, including gravity enrichment [11,12,13], chemical treatment [14,15,16], reduction roasting and reduction melting [17,18,19]. Among these, reductive leaching has emerged as a particularly promising approach, with the potential to transform BR into iron concentrate through high-pressure leaching [20,21,22]. This process involves reduction of iron minerals, such as hematite and goethite, to magnetite, thereby making it possible to separate them from other BR components by magnetic separation [23,24].

One implementation strategy for reductive leaching involves using Al and Fe powders to reduce Fe-bearing minerals directly in the leaching solution by hydrogen [25,26,27]. However, this process involves additional costs associated with purchasing and handling reducing agents. Alternative approaches utilize organic compounds [28,29,30] to reduce iron minerals. While this method shows promise, subsequent treatment of the leachate is required to remove organic impurities, which may affect the precipitation stage adversely [31].

Another method of iron mineral reduction, which does not require the addition of additional raw materials, is electrolytic reduction [32]. In this case, oxygen is released at the anode, while iron and hydrogen are released at the cathode. However, the proportion of current that is consumed to produce iron varies greatly depending on the composition of the solution [33]. This means that additional research is required so that the process can be carried out under the conditions of the Bayer process.

In our previous research [34,35], electrolytic reduction was successfully applied for leaching of hematite-boehmite bauxites, demonstrating its potential to improve the efficiency of the Bayer process. In this study, we extend this research by investigating the possibility of applying electrolytic reduction to high-iron goethite-gibbsite bauxites from Guinea. Different characterization techniques were used to analyze the feedstock and leaching products, including X-ray phase analysis (XRD), X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF) and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). Utilizing the electrolytic reduction of coarse BR particles makes it possible to obtain magnetite-containing residue with a high Fe content. Adding this residue to raw bauxite during the Bayer process enhances extraction efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

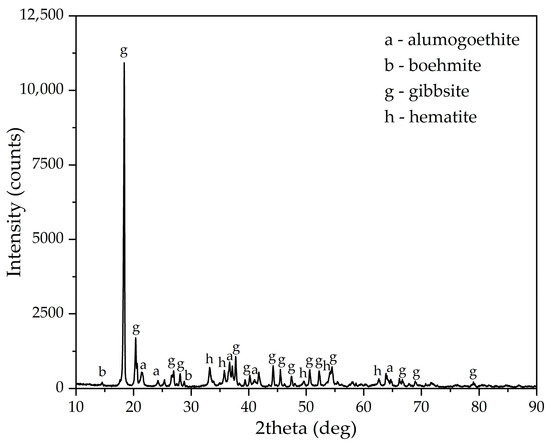

The gibbsitic bauxite from the Dian-Dian deposit in Guinea that was utilized in this study was provided by UC RUSAL (Moscow, Russia). Table 1 presents the chemical composition of the raw bauxite. A qualitative analysis suggests that its primary components consist of Al and Fe. The silica content was found to be negligible, with the silica module equivalent to 37.85 units. The significant presence of lost on ignition (LOI) can be attributed to the occurrence of hydroxide phases within the raw bauxite, as evidenced by the X-ray diffraction pattern presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the raw gibbsitic bauxite from Dian-Dian deposit, Guinea, wt. %.

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of the Dian-Dian bauxite, Guinea.

It is evident that the predominant Al-containing phase is gibbsite, with a negligible amount of boehmite. Iron is represented by two mineral species: alumogoethite ((Fe,Al)OOH) and hematite (Fe2O3). The high proportion of iron substitution by Al in goethite in this type of bauxite was confirmed in a previous study [36]. A spent aluminate solution for high-pressure leaching with a concentration of 100 g/L Al2O3 and 200 g/L Na2O was prepared by dissolving analytical-grade sodium hydroxide and aluminium hydroxide in distilled water. The required quantity of aluminium hydroxide was dissolved in a heated sodium solution that had a concentration of 300 g/dm3 of Na2O. The solution was then filtered to remove insoluble inclusions. Following analysis, the solution was diluted to the required concentration with distilled water prior to use. In electrolytical experiments, the solution was employed in its original concentration, without dilution.

2.2. Analytical Methods

XRD analysis of raw materials and solid products was performed using a XRD 7000 Maxima diffractometer (Shimadzu Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with a Cu-Ka radiation source and 15 min exposure time. Determination of the phase composition and semi-quantitative evaluation using the Rietveld method was carried out using Match! 3 (Crystal Impact, Bohn, Germany). The morphology of the solid product particles and elemental mapping were defined using a Tescan Vega 4 scanning electron microscope (SEM-EDX) (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic). The chemical composition of the samples was determined using a Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) EDX-8000 powder X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. The concentration of metal ions in the leach solutions was quantified using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) with a Expec 6500 spectrometer (Focused Photonics Inc., Hangzhou, China). The particle size distributions (PSD) of the raw BR and solid residues were studied using a Bettersizer ST particle size analyser (Bettersize Instruments, Liaoning, China), with an ultrasound exposure of 10 W. The magnetic properties of bauxite residue were determined using a vibrating sample magnetometer (Lake Shore 7407, Lake Shore Cryotronics, Inc., Westerville, OH, USA).

2.3. Experimental Procedure

The raw bauxite was ground in a rod mill prior to leaching, with the aim of obtaining 80% particles smaller than 70 µm. The bauxite was then mixed with a recycled solution at a Na2O:Al2O3 molar ratio of 1.4 after leaching in a pregnant solution. If necessary, reduced BR was then added to the mixture, which was then subjected to a preliminary desilication process at 75 °C for 16 h with constant stirring at 300 rpm in a sealed steel reactor placed in an oil bath integrated heating magnetic stirrer DF-101S (LICHEN Scientific Group, Shaoxing, China), which allowed heating to 210 °C. After that, the temperature of the water bath was increased to the desired temperature for high-pressure leaching. It was then kept there for 1 h, unless otherwise specified. To study the kinetics of the processes, the milled bauxite was sieved to obtain a narrow bauxite fraction. A 50–63 μm fraction was selected as its chemical composition did not differ from that of the total bauxite mass [37].

Once the leaching process was complete, the pulp was thickened in an air thermostat. After 10 min, the overflow was separated and sent for filtration and washing to separate the solution and obtain a finely dispersed fraction of BR. The underflow solid phase was washed and dried at 110 °C for 4 h before being sent for electrolytic reduction in a 500 mL stain-less steel thermostated reactor coated with PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) with a mesh current supply (surface area 70 cm2), as shown in the work [34]. The mesh was connected by stainless steel wire to the terminal of a ZiveLab SP 2 potentiostat (Zivelab, Seoul, Republic of Korea). A 10 cm2 nickel plate was used as the anode. The reference electrode was a mercury-mercury-oxide electrode OH-/HgO, Hg (RE-1A, YM, Xi’an, China).

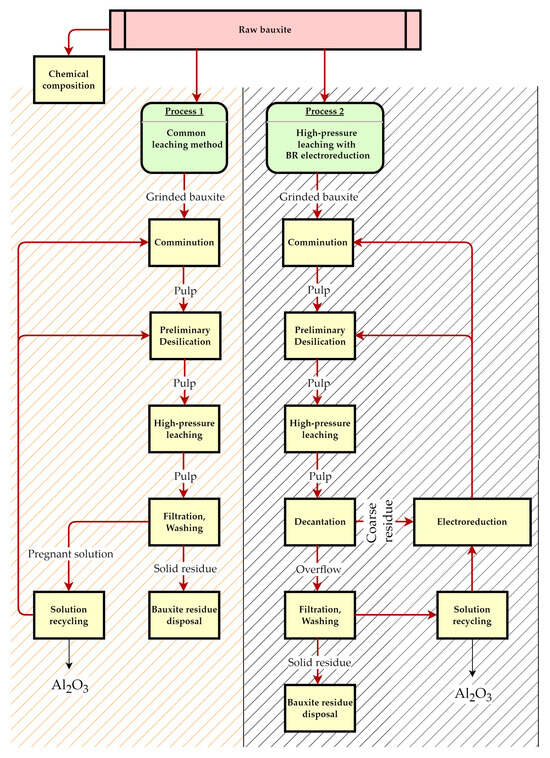

Figure 2 shows a general diagram of the common Bayer process and the process with the use of electrolytic reduction.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the common Bayer process and the process with the use of electrolytic reduction in this research.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Potential Application of Electrolytical Reduction in the Bayer Process for the Leaching of Gibbsitic Bauxite

Electrolytic reduction can be used in several options in the Bayer cycle for processing bauxite:

- Direct application of electrolytic reduction during leaching or pre-desilication.

- Electrolytic reduction of iron minerals in bauxite residue formed after leaching.

- Electrolytic reduction of the coarse fraction of bauxite residue (sands) obtained by gravity enrichment (decantation).

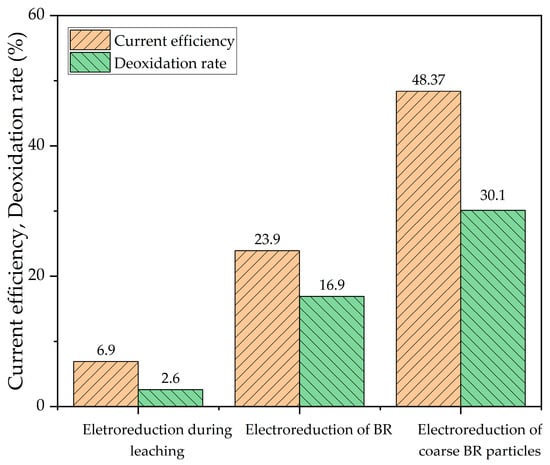

Option 1 could be the most effective in terms of simplifying the process flow. However, as shown in Figure 3, this method results in the lowest current efficiency due to the low concentration of free alkali in the solution. This is because, during the interaction of leaching agent (electrolyte) with gibbsite bauxite, Al dissolves even at low temperatures, causing the solution to become saturated with Al. Consequently, further research is required to make this method economically viable.

Figure 3.

Current efficiency and deoxidation rate at different variants of using electroreduction in the Bayer cycle at 110 °C, 100 g/L solid concentration, current density 150 A/m2 and time 1 h.

The raw bauxite was subjected to standard leaching at a temperature of 140 °C for 30 min according to the first process variant in Figure 2, yielding BR. The chemical composition of the BR is shown in Table 2. Electroreduction of this type of BR in the Bayer spent solution was much more efficient than electroreduction during bauxite leaching, but the current yield was still less than 24%. This is due to the high content of finely dispersed aluminosilicate particles formed during the leaching process, which also leads to low sedimentation efficiency.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of bauxite residue (BR) and the coarse fraction of BR (sands) separated by decantation after leaching of the raw bauxite at 140 °C for 30 min, wt.%.

Next, sands were extracted from the BR formed by the standard Bayer process by decantation. Table 2 shows the chemical composition of the sands that were separated by decantation. The yield of this fraction was 54.5%. It is evident that this fraction of BR contains more than 75% iron oxide.

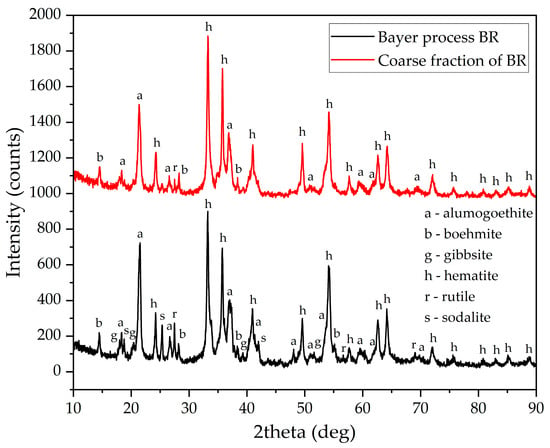

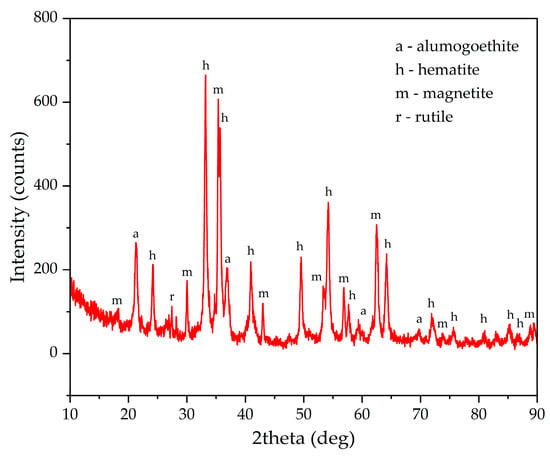

According to the XRD pattern shown in Figure 4 the main iron-containing phases in this BR are hematite and alumogoethite, the latter of which contains almost all undissolved Al. Additionally, as with ordinary BR, this fraction contains residues of boehmite. Unlike common BR, sodalite peaks are not visible in the sands, and there are much fewer rutile and gibbsite peaks, as confirmed by the chemical composition.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the common Bayer process BR and the sands.

The best result was obtained by using electrolytic reduction of sands iron minerals in a spent Bayer solution (Figure 3). This fraction has a higher hematite concentration (Figure 4), lower levels of aluminosilicate and no re-precipitated gibbsite, which explains the highest current efficiency.

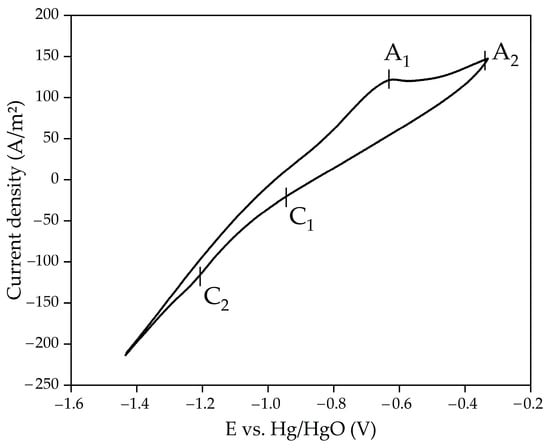

Figure 5 shows the results of cyclic voltammetry for suspension of the sands in a spent Bayer process solution at a temperature of 110 °C, with a solid concentration of 100 g/L and a measurement rate of 50 mV/s.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammetry at temperature 110 °C and solid concentration 100 g/L for suspension of sands in spent Bayer solution with the concentration 300 g/L Na2O.

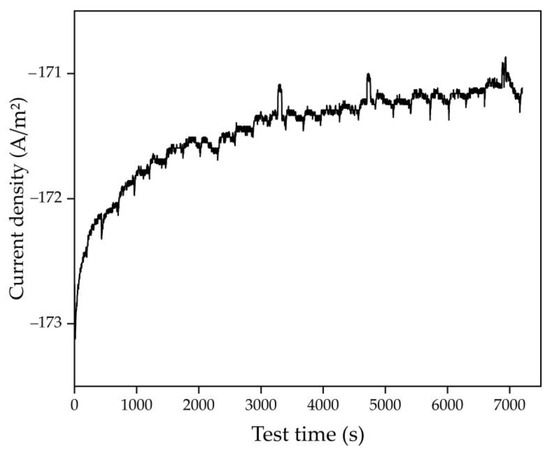

As with a purely alkaline solution [35], when BR is used as the initial material, the cathode currents C1 and C2 are barely distinguishable. However, C2 current, which corresponds to the formation of Fe at a potential of −1.21 V, can be seen. The anode peaks are much more visible as they are not masked by hydrogen evolution. Based on cyclic measurements, the following parameters were selected for reducing iron minerals in sands in a spent Bayer solution: temperature 110 °C; cathode potential relative to the mercury reference electrode −1.21 V; electrolysis duration until complete transformation of hematite into magnetite at 100% current efficiency; and solid concentration 100 g/L. Figure 6 shows the results of potentiostatic measurements during electrolysis over 2 h. It can be seen that the current density gradually decreased during electrolysis, which may be due to the formation of metallic Fe on the surface of the current supply [38].

Figure 6.

Dependence of current density on electrolysis time at a constant potential of −1.21 В using the bulk cathode and the suspension of sand in spent Bayer solution.

Figure 7 shows the results of the XRD analysis of the solid product of electrolysis. Following the additional treatment of the residue in an unsaturated spent Bayer solution containing Fe2+ ions, sodalite undergoes transformation and boehmite dissolves, while titanium compounds most likely convert to titanomagnetite or Ti(IV)-substituted hematite [29]. Their formation is related to the interaction between sodium titanate, which is deposited in an alkaline solution on mineral surface, and Fe2+ ions. There is a clear increase in the amount of magnetite and a decrease in the amount of goethite. According to the Rietveld method, magnetite accounted for 37.9% of the total iron oxides, while the mass of the current supply mesh increased by 0.1 g (5.8% of the consumed current) due to the formation of metallic Fe. The total proportion of current used to obtain magnetite and Fe was 43.7%. In a previous study using a pure alkaline solution, the current efficiency was over 73.8%. The difference can be attributed to the higher concentration of free sodium hydroxide in the pure alkali solution. Such efficiency in the use of electric current implies an increase in energy costs of ~35–40 kWh per t of bauxite, which makes the process more expensive. This can be mitigated by increased aluminium extraction and reduced BR production. However, further research is needed to improve the efficiency of electric current use in the Bayer process solution.

Figure 7.

XRD pattern of the electrolytically reduced sands.

Table 3 shows the chemical composition of the BR obtained after electroreduction. The Fe content of the BR increased to 83.2% (58.2% TFe) due to the dissolution of Al and Na. The proportion of LOI decreased due to the conversion of goethite to hematite and magnetite. The BR obtained was subsequently used as an additive in leaching new portions of bauxite.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of the electroreduced sands, wt.%.

3.2. The Effect of Electrolytically Reduced BR on High-Pressure Leaching of Gibbsitic Bauxite

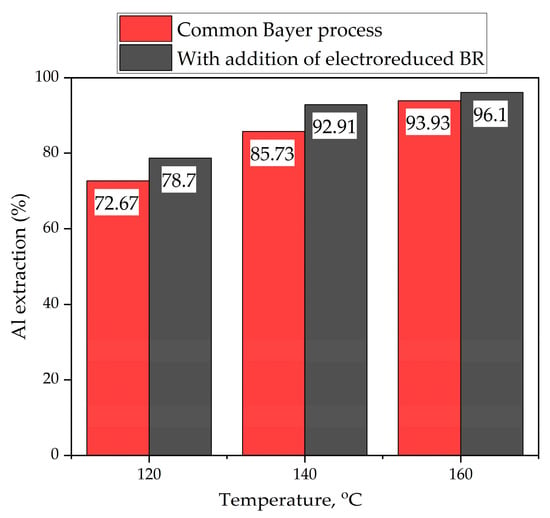

Experiments were conducted to evaluate the effect of adding electrolytically reduced sands on the leaching of gibbsitic bauxite. These experiments involved leaching raw bauxite with and without the addition of reduced sands at different temperatures for 30 min, based on a bauxite dosage that would produce a modulus of 1.4 units. The results of these experiments are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The effect of adding reduced BR to gibbsitic bauxite during leaching at different temperatures.

As can be seen, the addition of reduced BR slightly increases alumina extraction, by up to 7.2%. This may be related to the dissolution of alumogoethite and the destruction of sodium titanate that has precipitated onto the surface of minerals [29]. Without reduced BR, the degree of alumina extraction at 140 °C was 85.73%; with reduced sands, it increased to 92.91%. However, the additive increases residue yield, since 50% of the residue (the coarse fraction) is constantly recycled.

Examining the chemical composition of the bauxite residue (Table 4) reveals that the Fe content after electrochemical reduction is significantly higher, while the Al and alkali content is lower. This is partially because their concentration in the reduced BR was much lower (Table 3).

Table 4.

Chemical composition of the residue obtained after leaching with and without additive, wt.%.

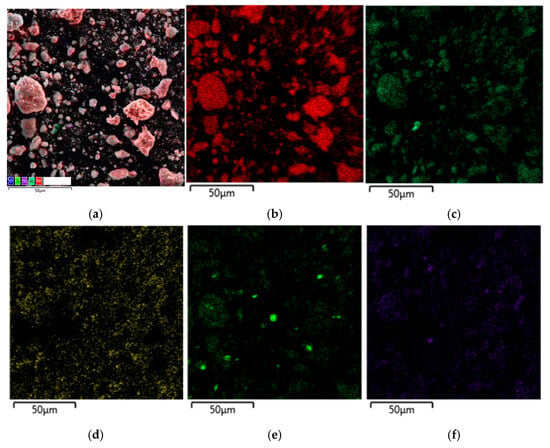

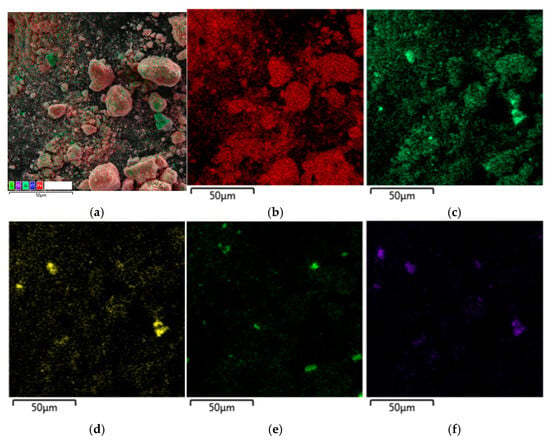

The chemical analysis is confirmed by comparing the SEM-EDS analysis results for the BR after electroreduction (Figure 9) and after standard Bayer process leaching (Figure 10). It is evident that, in the solid residue obtained by leaching with the addition of reduced BR, Al is associated with iron minerals; however, its content, as well as that of caustic alkali, is much lower than for standard Bayer process residue. The resulting BR is fully magnetic, with magnetization reaching 25.18 emu/g at a magnetic field of 10 kOe. After thickening, the fine fraction of the BR (D50 = 12.71 μm) can be sent for Fe concentrate separation and the coarse fraction (D50 = 63.30 μm) returned for electrolytic reduction. It should be noted that adding electrolytically reduced BR to the bauxite leaching process also significantly increases the thickening rate, making it easier to separate the solid residue particles from the leaching solution [35].

Figure 9.

SEM-EDX analysis of the residue after leaching with the addition of the reduced BR: (a) multilayer EDS; (b) map for Fe; (c) map for Al; (d) map for Na; (e) map for Ti; (f) map for Si.

Figure 10.

SEM-EDX analysis of the residue obtained by the leaching of raw bauxite without additive: (a) multilayer EDS; (b) map for Fe; (c) map for Al; (d) map for Na; (e) map for Ti; (f) map for Si.

3.3. Leaching Kinetics

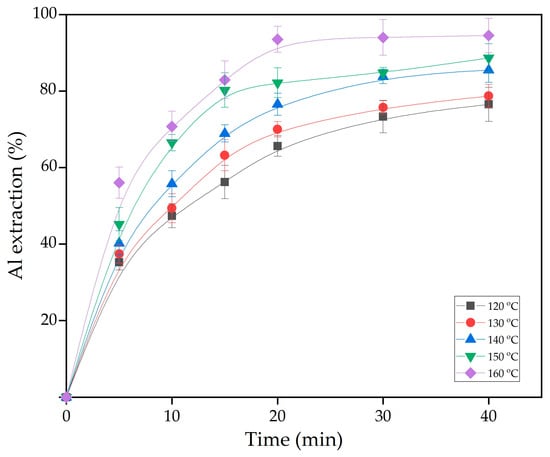

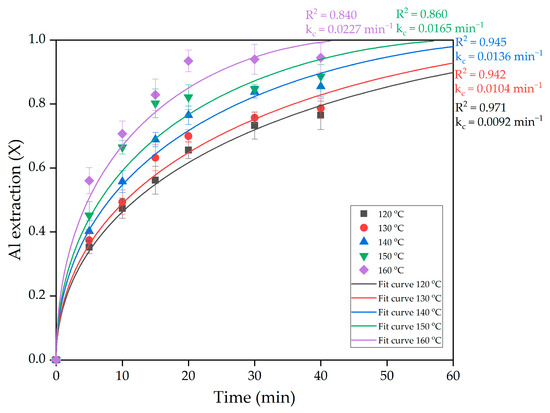

To study the kinetics of gibbsitic bauxite leaching with the addition of reduced sands, experiments were conducted on the effect of leaching duration on the degree of alumina extraction at different temperatures. In these experiments, the concentration of the recycled solution was 200 g/L of Na2O and 100 g/L of Al2O3. The L:S ratio was calculated to achieve a molar ratio of Na2O to Al2O3 of 1.4 in the pregnant solution. Reduced sands was added at amount of 15% of the raw bauxite mass (approximately 50% of the BR mass that will be formed during leaching of this type of bauxite). The results of the experiments are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

The effect of leaching time and temperature (symbols) on Al extraction from bauxite with the addition of reduced BR.

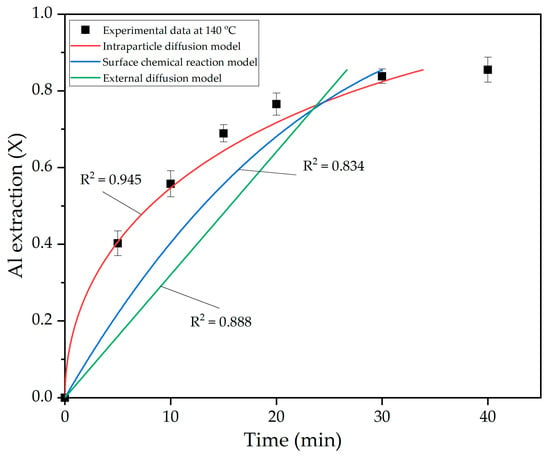

Figure 11 shows that temperature has a significant effect on the leaching rate of bauxite, especially during the first 15 min. After this time, the leaching rate decreases significantly due to the fact that, after 30 min of leaching (Figure 9), practically no gibbsite remains in the solid phase. In other words, the remaining Al is enclosed in boehmite and alumogoethite. These minerals require more time to leach, regardless of the leaching temperature, indicating that diffusion through the layer of unreacted substance becomes the limiting stage of the process. To evaluate this, the experimental data at 140 °C were fitted to various shrinking core model equations (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

The nonlinear fitting of data in Figure 11 at 140 °C into shrinking core model (SCM) equations.

Shrinking core model assumes that the initial substance dissolves from the particles’ surface during leaching, leaving an inert reaction product layer behind. As leaching proceeds, this layer expands and the core of the starting material shrinks [39,40,41]. If the process rate is limited by diffusion of the leaching agent to the core through the reaction product layer, Equation (1) for intra-particle diffusion is used. If the rate of the process is limited by the rate of the chemical reaction itself, Equation (2) is used. If the rate of the chemical reaction is limited by the supply of reagent to the particle surface through the liquid film, Equation (3) for external diffusion is used.

[1 − 2/3X − (1 − X)2/3] = kt.

[1 − (1 − X)1/3] = kt,

X = kt,

As can be seen in Figure 12, the equation for internal diffusion was best suited to describe the bauxite leaching process when electroreduced BR is added. This confirms the earlier assumption that the process is controlled by the leaching rate of alumogoethite and boehmite, which are enclosed in a solid matrix of iron minerals.

The distribution of Al and Fe on the surface of BR particles after leaching with and without the addition of electroreduced BR can be seen on the SEM-EDS mapping (Figure 9 and Figure 10). It is evident that Al is evenly distributed over the surface of the particles together with Fe, but there are also separate particles with high Al content, most likely boehmite. Additionally, the Al concentration decreases with the addition of the reduced BR and areas containing only Fe appear.

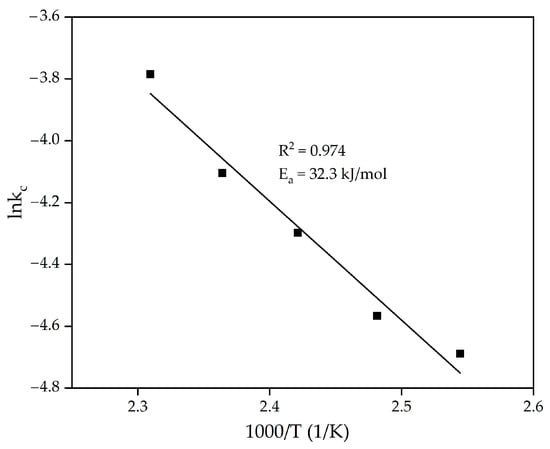

To determine the activation energy of the process, the experimental data in Figure 11 were fitted to the SCM for internal diffusion (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

The nonlinear fitting of data in Figure 12 into intraparticle diffusion SCM.

As can be seen from Figure 13, the experimental points agree well with the SCM at almost all temperatures, except at 150 and 160 °C. This is, however, due to the rapid plateauing once practically all the Al has been extracted from the raw material. The rate constants obtained by substituting the experimental data into the SCM were used to calculate the apparent activation energy of the process using the logarithmic form of the Arrhenius equation (Equation (4)).

lnk = lnA + Ea/RT,

The results of the substitution are shown in Figure 14. As can be seen from Figure 14, the apparent activation energy was found to be 32.3 kJ/mol, confirming that the process is limited by diffusion [42].

Figure 14.

Dependence of logarithm k in Figure 13 on inverse temperature (in temperature interval 120–160 °C).

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the potential for improving the extraction of Al and increasing the concentration of Fe in the residue through electrolytic reduction in a suspension of BR in a spent Bayer process solution. The main conclusions are as follows:

- The reduction of iron minerals in suspension of bauxite or fine BR particles (50% of particles less than 12 μm) in spent Bayer process solution resulted in current efficiency 6.9% and 23.9%, respectively. Therefore, further research is required to make this method economically viable.

- Maximal current efficiency of 43.7% was obtained after 2 h of electrical reduction using a suspension of coarse BR particles (sands) in spent Bayer process solution. The deoxidation rate of hematite and goethite to magnetite was 37.9%.

- The Fe2O3 content in the reduced residue increased to 83.2% versus 75.5% for the sands after Bayer leaching.

- The magnetite-containing residue was further used as an aid in the high-pressure Bayer process leaching of gibbsitic bauxite. Adding the reduced BR increased the Al extraction rate by up to 7.2%, the Fe2O3 content in BR—up to 15%.

- Kinetics results showed that Al leaching correlated well with the intra-particle SCM equation, indicating that reaction velocity is regulated by diffusion of the leaching agent through the product layer. The apparent activation energy of the process at 140–160 °C was found to be 32.2 kJ/mol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and I.L.; methodology, A.S.; software, D.V.; validation, A.S. and I.L.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, I.L.; data curation, I.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, D.V.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, I.L.; project administration, I.L.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation and Government of Sverdlovsk region, Joint Grant No 24-29-20287.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Evgeny Kolesnikov from NUST MISiS for his help with the SEM and XRD studies of the solid samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BR | Bauxite residue |

| SCM | Shrinking core model |

| XRD | X-Ray diffraction |

| SEM-EDS | Scanning electron microscopy with the energy dispersive spectroscopy analysis |

References

- Kaußen, F.M.; Friedrich, B. Methods for Alkaline Recovery of Aluminum from Bauxite Residue. J. Sustain. Metall. 2016, 2, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, B.I. The Chemistry of CaO and Ca(OH)2 Relating to the Bayer Process. Hydrometallurgy 1996, 43, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vind, J.; Alexandri, A.; Vassiliadou, V.; Panias, D. Distribution of Selected Trace Elements in the Bayer Process. Metals 2018, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, E.-S.A. Leaching Kinetics of Gibbsitic Bauxite with Sodium Hydroxide. E3S Web Conf. 2016, 8, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, P.; Oustadakis, P.; Kountouris, N.; Samouhos, M.; Anastassakis, G.; Taxiarchou, M. Iron Recovery from Turkish and Romanian Bauxite Residues Through Magnetic Separation: Effect of Hydrothermal Processing and Separation Conditions. Separations 2025, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, F.; Isworo, G.; Mahaputra, R.; Pintowantoro, S. Possible Strategies for Red Mud Neutralization and Dealkalization from the Alumina Production Industry: A Review for Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 5159–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhilash; Shrivastava, S.K.; Rahman, M.R.; Meshram, P. Red Mud Neutralisation by CO2 Promotes Alkali Recovery and Higher Scandium Extraction. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2025, 16, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomirovic, T.; Smith, P.; Southam, D.; Tashi, S.; Jones, F. Crystallization of Sodalite Particles under Bayer-Type Conditions. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 137, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Qi, T.; Liu, G.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. Phase Transformation of Desilication Products in Red Mud Dealkalization Process. J. Sustain. Metall. 2022, 8, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ning, Z.; Wang, X.; Chai, Q.; Zhang, R. One-Step Calcification–Biomaterialization Transformation Process for Treating High-Iron Bauxite Ore. JOM 2025, 77, 6711–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abikenova, G.K.; Dauletov, D.D.; Tverdokhlebov, S.A.; Danchenko, I.S. Investigation of the possibility of using depleted bauxite in alumina production at the Pavlodar aluminum plant. Kompleks. Ispolz. Miner. Syra = Complex Use Miner. Resour. 2025, 333, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, E.C.L.; Fernandez, O.J.C.; Emim, M.P.; Figueira, B.A.M.; Couto, N.A.F. Granulometric Separation of Bauxite Tailings to Metallurgical Processing. Mat. Res. 2025, 28, e20250076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.K.; Nayak, A.P.; Das, S.P. Ultrasonic-Assisted Pre-Concentration of Iron Values in Bauxite Residue Suitable for Reduction-Roasting Purpose. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2025, 212, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Ma, S.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Hui, H.; Zhang, Y. Dissolution Behavior of Aluminum and Silicon from Kaolinite Diaspore Symbiotic Low-Grade Bauxite in Low Alkali System. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 701, 134821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, J. A Novel Sustainable and Facile Method in Alumina Industry: Pre-Treatment of High Silica Bauxite by Cyclic Alkaline Leaching. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladyshev, S.; Dyussenova, S.; Abikak, Y.; Akhmadiyeva, N.; Imangaliyeva, L.; Bakhshyan, A. Selective Processing of the Kaolinite Fraction of High-Silicon Bauxite. Processes 2024, 12, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, M.K.; Zhu, M.; Safarian, J. Hydrogen Reduction of Bauxite Residue for Green Steel and Sustainable Alumina Production. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 1363–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopic, S.; Kostić, D.; Schneider, R.; Sievers, M.; Wegmann, F.; Emil Kaya, E.; Perušić, M.; Friedrich, B. Recovery of Titanium from Red Mud Using Carbothermic Reduction and High Pressure Leaching of the Slag in an Autoclave. Minerals 2024, 14, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilla, G.; Hertel, T.; Blanpain, B.; Pontikes, Y. Sustainable Recovery of Metallic Fe and Oxides from Bauxite Residue via H2 Reduction: Enhancing Purity and Recovery Rates. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. Enhanced Conversion Mechanism of Al-Goethite in Gibbsitic Bauxite under Reductive Bayer Digestion Process. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 3077–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. Cleaning Disposal of High-Iron Bauxite Residue Using Hydrothermal Hydrogen Reduction. Bull. Env. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 109, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lv, G.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; He, X.; Zhang, T. Summary of Research Progress on the Separation and Extraction of Iron from Bayer Red Mud. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 186–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, P.M.; Oustadakis, P.; Anastassakis, G.; Pissas, M.; Taxiarchou, M. Iron Recovery from Bauxite Residue (BR) through Magnetic Separation; Effect of Endogenous Properties and Processing Conditions. Miner. Eng. 2024, 217, 108954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, Z.; Shen, L. Efficient Separation of Iron and Alumina in Red Mud Using Reduction Roasting and Magnetic Separation. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, B.; Qi, T.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Pi, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, M. Reduction of Red Mud Discharge by Reductive Bayer Digestion: A Comparative Study and Industrial Validation. JOM 2020, 72, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. Comprehensive Utilization of Al-Goethite-Containing Red Mud Treated Through Low-Temperature Sodium Salt-Assisted Roasting–Water Leaching. J. Sustain. Metall. 2022, 8, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. Low-Temperature Thermal Conversion of Al-Substituted Goethite in Gibbsitic Bauxite for Maximum Alumina Extraction. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 4162–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lv, G.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Yun, Z.; Zhang, T. Innovative Starch-Based Alkaline Thermal Reduction of Hematite: A Fundamental Study on Mineral Phase Reconstruction and Its Potential in the Bayer Process. Miner. Eng. 2025, 231, 109452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, T.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Li, X. A Clean Two-Stage Bayer Process for Achieving near-Zero Waste Discharge from High-Iron Gibbsitic Bauxite. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 405, 136991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lv, G.; Liu, B.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yun, Z.; Zhang, T. Straw-Induced Hematite-to-Magnetite Conversion in Alkaline Media: Experimental Study and Potential in Bayer Process. Miner. Eng. 2025, 234, 109723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, H.; Liu, J. Negative Effects of Dissolved Organic Compounds on Settling Performance of Goethite in Bayer Red Mud. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maihatchi, A.; Pons, M.-N.; Ricoux, Q.; Goettmann, F.; Lapicque, F. Electrolytic Iron Production from Alkaline Suspensions of Solid Oxides: Compared Cases of Hematite, Iron Ore and Iron-Rich Bayer Process Residues. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 2020, 10, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoupa, S.; Koutalidi, S.; Bourbos, E.; Balomenos, E.; Panias, D. Electrolytic Iron Production from Alkaline Bauxite Residue Slurries at Low Temperatures: Carbon-Free Electrochemical Process for the Production of Metallic Iron. Johns. Matthey Technol. Rev. 2021, 65, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoppert, A.; Valeev, D.; Loginova, I. Novel Method of Bauxite Treatment Using Electroreductive Bayer Process. Metals 2023, 13, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoppert, A.; Loginova, I.; Diallo, M.M.; Valeev, D. Effect of Elemental Iron Containing Bauxite Residue Obtained After Electroreduction on High-Pressure Alkaline Leaching of Boehmitic Bauxite and Subsequent Thickening Rate. Materials 2025, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoppert, A.; Valeev, D.; Diallo, M.M.; Loginova, I.; Beavogui, M.C.; Rakhmonov, A.; Ovchenkov, Y.; Pankratov, D. High-Iron Bauxite Residue (Red Mud) Valorization Using Hydrochemical Conversion of Goethite to Magnetite. Materials 2022, 15, 8423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beavogui, M.C.; Balmaev, B.G.; Kaba, O.B.; Konaté, A.A.; Loginova, I.V. Bauxite Enrichment Process (Bayer Process): Bauxite Cases from Sangaredi (Guinea) and Sierra Leone. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Industrial Manufacturing and Metallurgy (ICIMM 2021), Nizhny Tagil, Russia, 17–19 June 2021; p. 020003. [Google Scholar]

- Haarberg, G.M.; Khalaghi, B. Electrodeoxidation of Iron Oxide in Aqueous NaOH Electrolyte. ECS Trans. 2020, 97, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, K.; Shoppert, A.; Rogozhnikov, D.; Kuzas, E.; Zakhar’yan, S.; Naboichenko, S. Effect of Preliminary Alkali Desilication on Ammonia Pressure Leaching of Low-Grade Copper–Silver Concentrate. Metals 2020, 10, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, K.A.; Rogozhnikov, D.A.; Kuzas, E.A.; Shoppert, A.A. Leaching Kinetics of Arsenic Sulfide-Containing Materials by Copper Sulfate Solution. Metals 2020, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenspiel, O. Chemical Reaction Engineering, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 0-471-25424-X. [Google Scholar]

- Gok, O.; Anderson, C.G.; Cicekli, G.; Cocen, E.I. Leaching Kinetics of Copper from Chalcopyrite Concentrate in Nitrous-Sulfuric Acid. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2014, 50, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.