Abstract

The presence of the brittle β/B2 phase in TiAl alloys often deteriorates their mechanical properties, posing a significant challenge for manufacturing large-sized, high-performance sheets. To address this issue, this study systematically investigates the synergistic effect of pack rolling and subsequent heat treatment on the microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of a Ti-44Al-4Nb-1.5Mo-0.1B-0.1Y alloy. Sheets with two different deformation levels (R7: 69.8% and R11: 83.0% reduction) were prepared via pack rolling. This was followed by a series of heat treatments at different temperatures (1150–1350 °C) and cyclic heat treatments at 1250 °C (3, 6, and 9 cycles). The results demonstrate that the higher deformation level (R11) promoted extensive dynamic recrystallization, resulting in a uniform microstructure of equiaxed γ, α2, and β phases, while the lower deformation (R7) retained a significant fraction of deformed γ/α2 lamellae. Heat treatment at 1250 °C was identified as optimal for transforming the microstructure into fine lamellar colonies while effectively reducing the β/B2 phase. Cyclic heat treatment at this temperature further decreased the β-phase content to 4.1% after 9 cycles. The elimination mechanism was determined to follow the β→ α → γ + α2 phase transformation sequence, driven by the combined effect of rolling-induced defects and cyclic thermal stress. Cyclic heat treatment at this temperature was particularly effective in generating a high density of nucleation sites within the lamellar colonies, leading to significant refinement of the lamellar structure. Consequently, the R11 sheet subjected to 9 cycles of heat treatment exhibited a 15.5% increase in tensile strength and an 8.3% improvement in elongation compared to the hot-isostatically pressed state. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the significant refinement of lamellar colonies and the reduction in interlamellar spacing. This work presents an effective integrated processing strategy for fabricating high-performance TiAl alloy sheets with superior strength and toughness.

1. Introduction

TiAl intermetallic compounds (hereafter referred to as “TiAl alloys”) exhibit low density, high specific strength, and excellent oxidation resistance, showcasing broad application prospects in high-temperature structural components for aerospace engineering [1,2,3,4,5]. For key components of hypersonic weapons such as spacers, hot-section skins, and wings, their requirements for light weight, heat resistance, and high strength are extremely stringent, creating an urgent need to prepare large-sized, high-performance TiAl alloy sheets [6]. However, the poor room-temperature ductility and significant forming difficulties of TiAl alloys severely restrict their widespread application [2,7]. Currently, researchers focusing on TiAl alloys primarily employ pack rolling to improve their formability [8,9]. Meanwhile, to enhance the high-temperature deformation capacity of TiAl alloys, a common strategy involves incorporating β-phase stabilizing elements (such as Nb and Mo) to introduce the body-centered cubic (BCC) β-phase, which boosts high-temperature processing plasticity [10,11]. However, the BCC β-phase transforms into the ordered B2 phase during cooling, a phase characterized by significant room-temperature brittleness that severely impacts the service performance of TiAl alloys.

To address the challenge of preparing large-sized, high-performance TiAl alloy sheets, researchers have primarily employed rolling processes integrated with heat treatment. Rolling effectively homogenizes the microstructure of TiAl alloys, refining lamellar colonies. Increasing deformation amount and improving rolling rate are critical approaches to optimize the microstructure of metallic materials. Current research focuses on exploring the limits of pack rolling to maximize deformation and enhance rolling rate, thereby promoting microstructural refinement. Previous studies have typically employed double-step [12] and multi-step [13] heat treatments to eliminate residual β-phase in TiAl alloys, aiming to achieve a fully lamellar microstructure. However, these processes suffer from long treatment times, low efficiency, and strict temperature accuracy requirements. Additionally, they exhibit inefficient regulation of the internal microstructure within lamellar colonies and are ineffective in significantly refining lamellar spacing. To address these limitations, an increasing number of researchers have turned to cyclic heat treatment—a method involving rapid, periodic temperature fluctuations within the near-α phase region. This approach effectively promotes β-phase elimination and enhances microstructural refinement. Notably, Kim’s research team in Korea [14] demonstrated that cyclic heat treatment of as-cast TiAl alloys can refine coarse as-cast microstructures, reducing their size from 1000 μm to 65 μm.

Over the past decade, the incorporation of β-phase stabilizing elements such as Nb, Mo, and V has emerged as a focal point in TiAl alloy composition design [15]. This approach balances two critical requirements: first, ensuring sufficient β-phase presence to facilitate coordinated deformation during high-temperature processing and enhance hot-formability, and second, minimizing residual β/B2 phases at room temperature to improve the alloys’ service performance. The TNM (Ti-42-46Al-xNb-xMo) alloy embodies this dual objective effectively, making it a suitable candidate for this study. In recent years, TNM alloys have garnered increasing attention due to their exceptional hot workability, as demonstrated in prior investigations [2,16,17]. Due to their high content of β-phase stabilizing elements (Nb, Mo), TNM alloys maintain adequate β-phase during high-temperature deformation to facilitate coordinated plastic flow. In this study, heat treatment is employed to regulate the retention of β/B2 phases at room temperature. In this paper, the effects of different rolling processes on the microstructure and mechanical properties of TiAl alloys are systematically investigated. Concurrently, heat treatment is used to optimize the microstructure, minimizing β/B2 phase content to ensure the mechanical integrity of TiAl alloy sheets. This integrated approach ultimately yields large-sized, high-performance TiAl alloy sheets with excellent service performance.

2. Materials and Methods

In this paper, a TiAl alloy with a nominal composition of Ti-44Al-4Nb-1.5Mo-0.1B-0.1Y was selected (a variant of the TNM alloy). The raw materials used to synthesize the alloy included sponge Ti (99.99%), high-purity Al (99.999%), Ti-52Nb, and Ti-32Mo. To eliminate potential segregation, the alloy was remelted three times in a vacuum-suspension melting furnace and then subjected to hot isostatic pressing. The actual main composition was determined to be Al: 44.25%, Nb: 3.84%, and Mo: 1.59%.

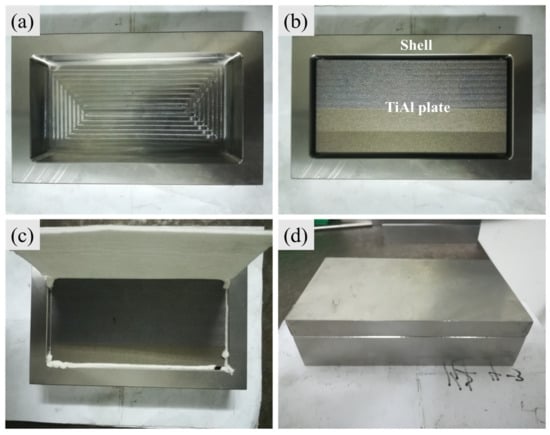

The TiAl alloy ingots obtained after melting and hot isostatic pressing were used to cut TiAl alloy sheets with dimensions of 80 mm × 40 mm × 10 mm from the central region using a wire cutting process. Previous experience has shown that stainless steel effectively harmonizes with the plastic deformation of TiAl alloy, making it a suitable choice for the envelope shell material [18]. At the same time, the size of the stainless-steel shell needs to be carefully designed. It should not only ensure sufficient space between the stainless-steel shell and the TiAl alloy plate to reduce stress concentration during deformation, but also ensure a proper fit to prevent inhomogeneous plastic deformation (as shown in Figure 1a,b). TiAl alloy is highly sensitive to temperature during the deformation process. To further minimize the temperature drop during rolling, a layer of high-temperature protective cotton was inserted between the plate and the stainless-steel shell, as shown in Figure 1c. This layer helps maintain a more uniform temperature. Additionally, the stainless steel upper and lower covers are welded together to prevent shear cracking of the shells during the rolling process, as shown in Figure 1d.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the jacket rolling set: (a) Stainless steel shell. (b) Placement of plates. (c) Filling with high-temperature protective cotton. (d) Welding of the stainless-steel shell.

The hot working plastic deformability of TiAl alloys improves with an increase in deformation temperature; however, excessively high temperatures can lead to the formation of coarse grains. Based on the heat processing diagrams for Ti-44Al-4Nb-1.5Mo alloys [5,19], TiAl alloys exhibit excellent deformation capability in the temperature range of 1180–1220 °C. Therefore, a deformation temperature of 1200 °C was selected for the pack rolling process to ensure that deformation occurs within the γ+α two-phase region. Table 1 presents the deformation conditions of the TiAl alloy for each rolling pass. The rolling speed is about 0.2m/s, and the mean strain rates ranges from 0.42 s−1 to 1.84 s−1. The initial thickness of the pack (including the stainless-steel shell) is 40 mm. At the beginning of the deformation, a large rolling reduction of 20% is applied, followed by 15% rolling reduction for passes 2 through 10, and a 9.3% rolling reduction for the final pass. After each rolling pass, the plate is returned to the heating furnace for a 15-min holding time to minimize the adverse effects of temperature drop on the rolling process. To study the effect of different deformation levels on the thermal deformation of TiAl alloy, two deformation conditions are designed in this study. One sheet is rolled to the seventh pass, with a final sheet thickness of 12.1 mm and a total reduction of 69.8%, referred to as the R7. The other plate is rolled to the eleventh pass, with a final sheet thickness of 6.8 mm and a total reduction of 83.0%, referred to as the R11. After rolling, all plates were placed in a furnace at 800 °C and cooled to room temperature in the furnace. Slow furnace cooling from 800 °C allows the material to pass through this critical zone gradually, minimizing internal stresses and preventing crack initiation [2].

Table 1.

TiAl Alloy Rolling Process Chart.

Hot rolling of TiAl alloys is conducted in a double-stick hot rolling mill located at the National Engineering Research Center for Advanced Rolling and Intelligent Manufacturing of the University of Science and Technology Beijing (Beijing, China). The roll surface width of this mill is 350 mm, and the drum diameter is 380 mm. To investigate the mechanism behind the changes in the heat treatment process of TiAl alloys, this study utilizes a DIL805A thermal expansion meter(BÄHR, Hüllhorst, Germany) to ensure the accuracy of the heat treatment temperature. The microstructure of the TiAl alloy was observed using backscatter electron diffraction (BSE) with a Quanta 450 FEG field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) (FEI Company, Brno, Czech Republic). In this study, the samples were tested by Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) using Oxford Instruments’ Nordlys Max3 (Abingdon, UK) with a step size of 0.3 μm. The EBSD samples were prepared as follows: they were first mechanically polished, followed by electropolishing using a solution of 6% perchloric acid, 34% butanol, and 60% methanol at −25 °C. For Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) observations, a Tecnai G2 F30 field emission transmission electron microscope (FEI, Long Island, NY, USA) was employed. The transmission specimens were initially polished to a size of φ3 × 0.3 mm and subsequently thinned by ion milling. Tensile tests were conducted at a universal testing machine (Changchun Institute of Testing Machinery, Changchun, China). The tensile specimens were cut parallel to the rolling direction, and the tensile rate was 0.05 mm/min at both room temperature and elevated temperatures (650, 750 and 850 °C). For elevated temperature tests, the samples were soaked at the target temperature for 10 min before applying the tensile load.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure Analysis of TiAl Alloy Sheet After Rolling

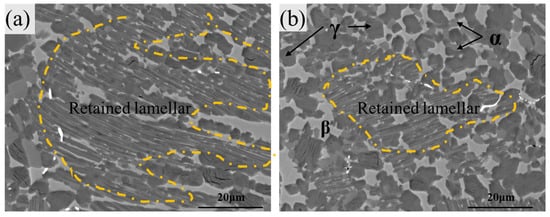

During the pack rolling process, TiAl alloys experience different stress conditions in the center and edge regions, with the edge region being more susceptible to temperature drops due to contact with stainless steel. Therefore, it is important to investigate the microstructure of TiAl alloys in these regions after rolling deformation. Figure 2a shows the microstructure of the edge region of the R7. It can be observed that most of the γ/α2 lamellae are preserved, with the lamellae being twisted and bent. A small amount of spherical β phase and γ phase particles are present around the γ/α2 lamellae, indicating that dynamic recrystallization has occurred at the lamellae interfaces. Figure 2b shows the microstructure of the central region of the R7 sheet, which mainly consists of equiaxed γ, α2, and β phases, along with residual γ/α2 lamellae. The volume fraction of γ/α2 lamellae in the central region is significantly lower than that in the edge region. Compared to the edge region, the microstructure in the central region is more uniform and exhibits finer grains. Compared to the microstructures obtained after Gleeble-3500 thermal simulation of compression at 1200 °C by our research group, the rolled-and-deformed microstructure contains a higher proportion of γ/α2 lamellae and a larger number of equiaxed recrystallized γ phase particles. In contrast, fewer recrystallized α2 phase particles are present [5,19]. This is primarily due to the larger strain rate and higher lnZ (Zener–Hollomon) value during pack rolling [20], which promote dynamic recrystallization within the sheet layer. The appearance of a large number of equiaxed recrystallized γ phase particles can be explained as follows: Pn one hand, the 15-min holding after each rolling pass provides sufficient time for recrystallized grains to grow, leading to the formation of equiaxed γ phase particles. On the other hand, the holding also helps release the stresses generated during the rolling process, which inhibits the γ→α2 phase transformation, resulting in a lower content of α2 phase.

Figure 2.

BSE-SEM images of the R7 rolled sheet microstructure: (a) Edge region, (b) Center region.

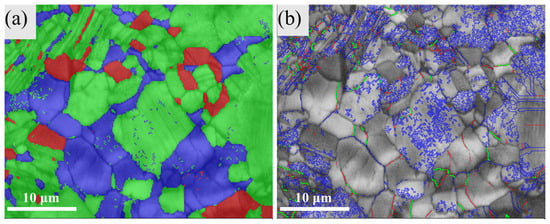

Figure 3 presents the EBSD phase map and the corresponding inverse pole figure (IPF) of the central region in the R7 sheet. The phase map in Figure 3a reveals that the microstructure comprises γ (green, 80.0%), β (blue, 16.1%), and α2 (red, 3.9%) phases. This represents a change of −4.3%, +5.1%, and −0.8% for the γ, β, and α2 phases, respectively, compared to the hot-isostatic-pressed (HIPed) state. Notably, the rolling deformation leads to an increase in β phase content but a decrease in both α2 and γ phases. Dynamic recrystallization refines the equiaxed γ, β, and α2 phases to average grain sizes of 4.9 μm, 6.2 μm, and 5.6 μm, respectively. The refinement occurs because DRX nucleation (via grain boundary bulging in the γ-phase or sub-grain rotation in the α2-phase) creates new fine grains. In TiAl alloys with low stacking fault energy, dynamic recovery is limited, leading to high dislocation densities that promote extensive DRX nucleation. These equiaxed phases are uniformly dispersed around the residual γ/α2 lamellae. Additionally, annealing twins are observed within the γ phase, as indicated by the arrows in Figure 3a. The IPF map in Figure 3b shows a residual γ/α2 lamella within the boxed area, exhibiting a consistent crystallographic orientation throughout. The arrows inside the box point to coarse γ phase laths (identified by correlating with Figure 3a) that have grown via recrystallization and exhibit orientations differing from the surrounding lamella. In contrast, the black-circled area exhibits highly scattered orientations, indicating the formation of numerous new, fine grains within the lamellae, many of which are submicron-sized (<1 μm). Both the boxed and circled regions in Figure 3b correspond to residual γ/α2 lamellae from Figure 3a. However, they exhibit markedly different degrees of recrystallization due to localized variations in deformation strain. In the circled region, the lamellae experienced more severe deformation, leading to a higher degree of recrystallization, partial fragmentation, and decomposition.

Figure 3.

EBSD analysis of the microstructure of the R7 rolled sheet: (a) Phase map; (b) IPF diagram, (the α2 phase in red, γ phase in green, and β phase in blue).

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis of the microstructures in the edge and center regions of the R11 sheet following the rolling process. As shown in Figure 4a, the edge region of the R11 sheet exhibits wedge-shaped cracks and intergranular pores. The pronounced divergence in grain flow directions on either side of these cracks (highlighted by red arrows) signifies that cracking initiated from inhomogeneous deformation at the microgranular level. The formation of these defects is attributed to two synergistic factors. Firstly, the substantial total reduction (83.0% for R11 vs. 69.8% for R7) induces severe deformation and localized flow instability in the edge region. Secondly, the thinner pack resulting from higher reduction accelerates heat dissipation during rolling, leading to a greater temperature drop. This temperature decrease markedly reduces the alloy’s plasticity, and the combined effect of lower temperature and higher strain promotes crack initiation and propagation. In stark contrast, the center region (Figure 4b) is nearly devoid of lamellar structures and consists predominantly of a uniform dispersion of equiaxed γ, β, and α2 phases. This homogeneous microstructure indicates that dynamic recrystallization was extensive and complete in the center, where thermal conditions were more stable and deformation was more uniform than at the edges.

Figure 4.

BSE-SEM images of the R11 rolled sheet microstructure: (a) Edge region, (b) Center region.

Figure 5 presents a comprehensive EBSD analysis of the center region of the R11 sheet, detailing the phase constitution and the grain boundary character distribution. The phase map in Figure 5a quantifies the phase fractions as 60.6% γ, 29.9% β, and 9.4% α2. A comparative analysis with the R7 sheet reveals that the increased total reduction of 83.0% in the R11 sheet promotes phase transformations, leading to a decrease in γ phase content accompanied by an increase in both the β and α2 phase contents. The near-doubling of β phase content from R7 (16.1%) to R11 (29.9%) is attributed to the higher rolling reduction. The greater deformation in R11 promotes a more extensive γ→β phase transformation due to increased defect density and stored energy. Simultaneously, the associated faster cooling helps suppress the β→α transformation during cooling, leading to greater retention of the metastable β phase at room temperature. The grain boundary misorientation distribution map in Figure 5b delineates low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs, 2–5°, in red), medium-angle grain boundaries (MAGBs, 5–15°, in green), and high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs, 15–90°, in blue). A predominant presence of blue HAGBs within the γ phase regions provides direct evidence of extensive dynamic recrystallization (DRX) [21,22]. This is because the transformation of subgrain boundaries (LAGBs) into HAGBs through the absorption of dislocations is the fundamental mechanism behind DRX. The high density of HAGBs indicates that the rolling process, with its larger strain rate, provided sufficient driving force for complete recrystallization, resulting in a refined microstructure of equiaxed grains.

Figure 5.

EBSD images of the microstructure of the R11 rolled sheet: (a) Phase diagram (the α2 phase in red, γ phase in green, and β phase in blue), (b) grain boundary misorientation distribution map.

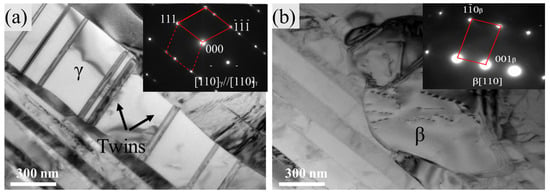

Owing to its high volume fraction, the γ phase undergoes extensive dynamic recrystallization (DRX), which dominates the deformation mechanism during the rolling of TiAl alloy sheets. Moreover, the formation of annealing twins within the γ phase is evident, as clearly revealed in the TEM micrograph of Figure 6a. These twins contribute to strain accommodation during the deformation and subsequent grain growth. The critical role of the β-phase in coordinating deformation is further elucidated by the dislocation configurations observed via TEM in Figure 6b. The presence of dislocations within the β phase (B2 structure) confirms its capacity to accommodate plastic strain by slip, thereby enhancing the overall workability of the alloy by mitigating stress concentrations at the γ/β interfaces [23].

Figure 6.

Microstructure of the R11 sheet: (a) Twin in the γ phase; (b) Dislocations in the β phase.

A comparison of the microstructure between the R7 and R11 sheets reveals that the amount of residual γ/α2 lamellae in the TiAl alloys decreases with increasing deformation. This phenomenon is attributed to the large reduction, which promotes dynamic recrystallization, thereby crushing and decomposing the lamellae. In the R7 specimen, due to insufficient deformation, recrystallization was incomplete, resulting in the retention of some lamellar colonies. Regarding microstructural uniformity, the R7 sheet exhibits minimal differences between its edge and center regions due to limited deformation. In contrast, the R11 sheet develops edge cracks in the edge region owing to significant deformation and an associated temperature drop. Meanwhile, the center region of the R11 sheet undergoes sufficient recrystallization, resulting in a fine and uniform microstructure.

3.2. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure of TiAl Alloy Sheets

The β/B2 phase in TiAl alloys can negatively impact mechanical properties such as creep resistance and fatigue performance during high-temperature service [24,25]. Therefore, a suitable heat treatment is essential for hot-rolled TiAl alloy sheets. The objective of this heat treatment is to minimize the β/B2 phase content and achieve a microstructure with uniform, fine lamellae.

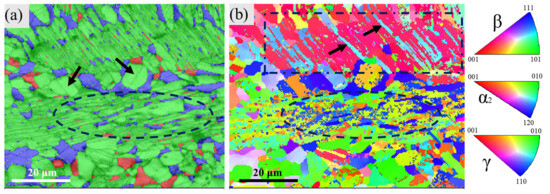

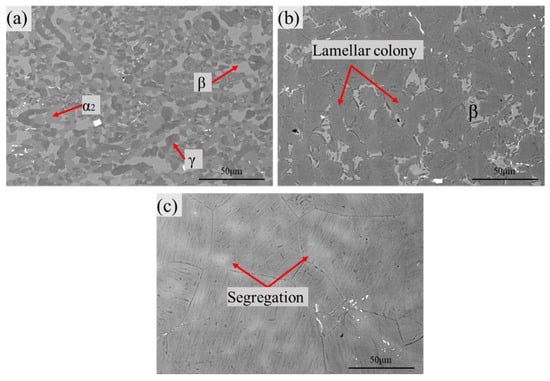

Figure 7 presents the microstructure of the R7 sheet after being held at 1150, 1250, and 1350 °C for 1 h, followed by air cooling. As shown in Figure 7a, after holding at 1150 °C, the microstructure primarily consists of equiaxed γ, α2, and β phases, with the lamellar structure being essentially absent. At 1250 °C, the microstructure transforms from the initial rolled state into a lamellar structure, with a few free β phase particles distributed along the lamellar boundaries. At this temperature, the average lamellar size is 25.7 μm. When the temperature is further increased to 1350 °C, only coarse lamellar structures, ranging from 50 to 100 μm in size, are observed, along with the presence of white deviatoric bands in the microstructure.

Figure 7.

Microstructure of the R7 sheet after heat treatment under different conditions: (a) 1150 °C/1 h, air cooling; (b) 1250 °C/1 h, air cooling; (c) 1350 °C/1 h, air cooling.

Figure 8 shows the microstructure of the R11 sheet after heat treatment at different temperatures. From Figure 8a, it is evident that, compared to the rolled state, the deformation traces and elongation have largely disappeared after heat treatment at 1150 °C, and the content of the α2 phase has increased significantly. After heat treatment at 1250 °C, the microstructure primarily consists of γ/α2 lamellae (with an average colony size of 21.7 μm) and β phase grains distributed along the lamellar boundaries. The β phase appears “embedded” within the γ phase present at the boundaries. Compared to the as-rolled condition, the β phase content is significantly reduced. After heat treatment at 1350 °C, the microstructure is composed mainly of coarse γ/α2 lamellae, with an average colony size ranging from 50 to 80 μm, and β phase grains are sparsely distributed around them. Compared to the R7 sheet, the R11 sheet develops a finer lamellar structure after heat treatment. This is attributed to the greater deformation endured by the R11 sheet, which results in a higher density of dislocations and defects. These defects provide additional nucleation sites for recrystallization, leading to a finer microstructure. The rapid coarsening of the lamellae in both the R7 and R11 sheets during heat treatment at 1350 °C is primarily due to the high temperature and abnormal grain growth occurring in the α-single phase region. In contrast, during heat treatment at 1250 °C (Figure 8b), lamellar growth is less pronounced because the temperature is below the α-transus temperature, and the α2 and γ phases mutually pin each other, inhibiting the coarsening of the γ/α2 lamellae.

Figure 8.

Microstructure of R11 sheets after heat treatment under different conditions (a) 1150 °C/1 h, air cooling; (b) 1250 °C/1 h, air cooling; (c) 1350 °C/1 h, air cooling.

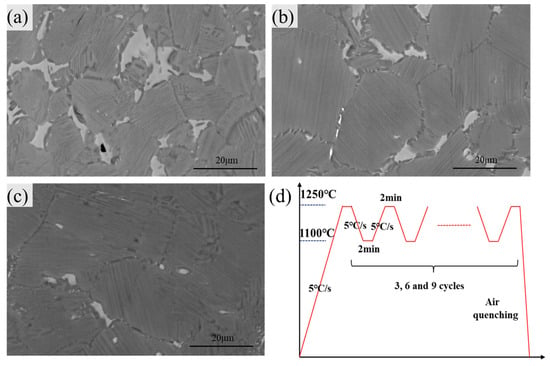

Based on the results of heat treatments at different temperatures, the treatment at 1250 °C was found to be most effective in reducing the β/B2 phase content. To further control the β/B2 phase content, a cyclic heat treatment process at 1250 °C was employed. This cyclic heat treatment was performed exclusively on the R11 sheet because it exhibited a finer initial microstructure after conventional heat treatment compared to the R7 sheet. Figure 9 presents the microstructural evolution of the R11 sheet subjected to varying numbers of cyclic heat treatments. The β phase content was measured to be 11.7%, 5.2%, and 4.1% after 3, 6, and 9 cycles, respectively. Evidently, the β phase content decreases with an increasing number of cycles. Additionally, the size of the γ/α2 lamellae initially increased and then decreased as the number of thermal cycles increased. The β phase, distributed at the lamellar boundaries, acts as a pinning agent, inhibiting the growth of the lamellae. When the number of cycles increased from 3 to 6, the significant reduction in β phase content weakened its pinning effect, consequently allowing the lamellae to coarsen. However, as the number of cycles increased further from 6 to 9, the reduction in β phase content became less pronounced. Nevertheless, the continued cyclic treatment promoted recrystallization nucleation, which became the dominant mechanism for microstructural refinement, leading to a decrease in lamellar size. This observation is consistent with the work of Luo [26], who refined the microstructure of Ta-containing TiAl alloys via cyclic heat treatment and identified two refinement mechanisms: phase boundary α-nucleation and grain boundary α-nucleation. The refinement observed in our study at high cycle numbers may involve similar mechanisms.

Figure 9.

Microstructure of R11 sheet after cyclic heat treatment (a) After 3 cycles; (b) After 6 cycles; (c) After 9 cycles; (d) Cyclic heat treatment process flow diagram.

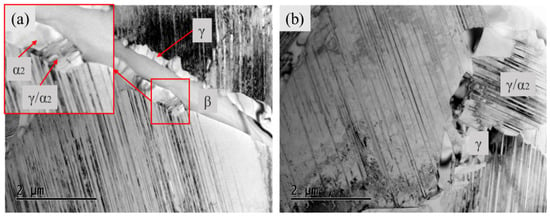

Figure 10 presents the TEM morphology of the R11 sheet after 3 and 9 cycles of heat treatment. In Figure 10a, the γ, β, and α2 grains surrounding the lamellae are clearly visible. Notably, fine γ/α2 lamellar colonies can be observed inside the α2 grains, as highlighted by the red rectangle. The β phase preferentially transforms into the α phase following the expulsion of Ti and absorption of Al, as these two phases are chemically similar, facilitating a rapid compositional change. Subsequently, these α phases transform into γ/α2 lamellae during cooling. Figure 10b presents the TEM morphology after 9 cycles of heat treatment. It can be observed that equiaxed microstructures are almost absent at the lamellar boundaries. A smaller lamellar colony, approximately 2 μm in size, is visible between two larger colonies. This likely represents a lamellar colony whose growth was incomplete following the elimination of the β phase. Analysis of the TEM images (Figure 10) indicates that the interlamellar spacing of the γ/α2 lamellae after nine cycles was approximately 100 nm, significantly smaller than that in the hot-isostatically pressed condition (338 ± 16 nm). During the cyclic heat treatment at 1250 °C, which is slightly above the γ-solvus temperature (Tγsolve, 1247 °C), the microstructure was in a critical state within the α-phase region. During the cooling segment of each cycle, fine γ laths precipitated from the α-phase, concurrent with the α → α2 ordering reaction, leading to the formation of the γ/α2 lamellar structure. In summary, the elimination mechanism of the β phase follows the sequence β → α → γ + α2. This process is collectively driven by the distortion energy and defects introduced by rolling deformation, along with the high temperature and cyclic thermal stresses during heat treatment.

Figure 10.

TEM image of R11 sheet after cyclic heat treatment (a) After 3 cycles; (b) After 9 cycles.

3.3. Mechanical Properties and Fracture Mechanism of TiAl Alloys

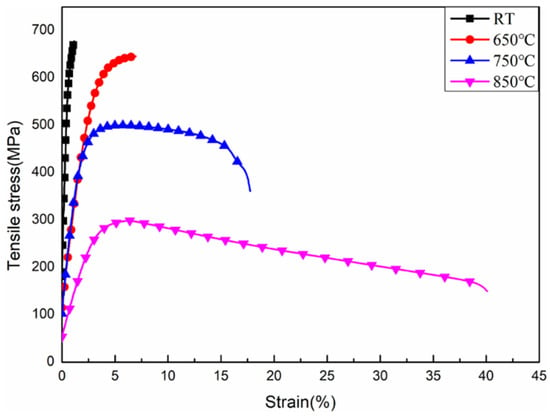

Figure 11 shows the tensile property curves of the TiAl alloy sheets at room temperature and high temperature after nine heat treatment cycles at 1250 °C. At room temperature, the alloy exhibited a tensile strength of 676.4 MPa and an elongation of 1.43%. Compared with the hot-isostatically pressed (before the hot pack-rolling) TiAl alloy, the heat-treated sheet showed increases of 90.7 MPa (15.5%) in tensile strength and 0.11% (8.3%) in elongation. These enhancements are attributed to two main factors. First, the heat treatment resulted in a nearly fully lamellar microstructure with substantially reduced contents of the β and γ phases. This fully lamellar structure possesses high intrinsic strength due to its ordered arrangement. Second, the rolling and heat treatment processes refined the γ/α2 lamellae, reducing their size from about 40–50 μm to 20–30 μm. This refinement improves plasticity by facilitating more uniform deformation at the lamellar interfaces.

Figure 11.

Room-temperature and high-temperature tensile mechanical properties of R11 sheet.

The tensile strengths of the TiAl alloy sheets at 650 °C, 750 °C, and 850 °C were measured as 653.7 MPa, 498.1 MPa, and 301.3 MPa, respectively. The corresponding elongations were 6.8%, 17.5%, and 41.2%. This indicates that the tensile strength decreases while the elongation increases with increasing temperature. The primary reason for this trend is that the thermal activation energy for deformation decreases at elevated temperatures. This reduction facilitates dislocation glide, climb, and twin formation, thereby enabling more extensive plastic deformation. The experimental results reported by Xu et al. [27]. indicate a yield strength ranging from 416 to 440 MPa and an elongation between 7.5% and 11.7%. In contrast, the alloy investigated in this study demonstrates an approximately 11% increase in yield strength and an approximately 80% improvement in elongation compared to those values.

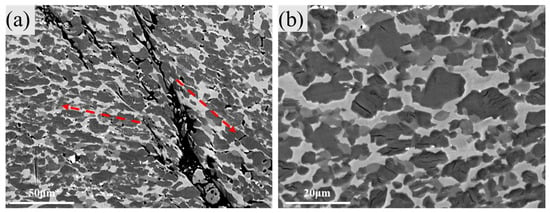

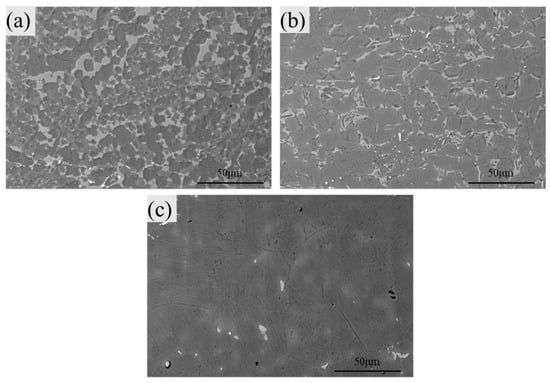

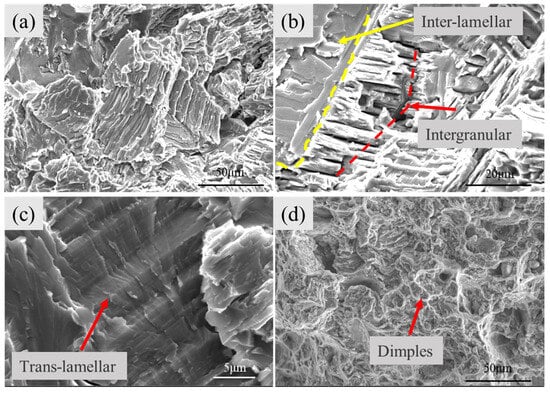

To investigate the fracture mechanism of the TiAl alloy during tensile deformation, its fracture behavior after room-temperature and high-temperature tests was analyzed, as shown in Figure 12. Figure 12a reveals that the room-temperature tensile fracture exhibits characteristics of brittle fracture, involving a mixture of trans-lamellar, inter-lamellar, and inter-granular cracking. In Figure 12b, the small facet in the upper-left corner corresponds to an inter-lamellar fracture, where the crack propagates rapidly along the direction parallel to the γ/α2 lamellae, resulting in a smooth and flat fracture surface. The central region of Figure 12b shows inter-granular fracture, where the crack extends along the interfaces of the γ/α2 lamellae. At this stage, the bending and deflection of the interfaces at their intersections dissipate the crack propagation energy, thereby inhibiting further crack advancement. Previous research [28,29] has indicated that the propagation rate of inter-lamellar cracks is closely related to the lamellar size in TiAl alloys. When the lamellae are relatively coarse, the number of lamellar interfaces and intersections per unit volume is reduced. Consequently, the crack propagation rate along the inter-granular path increases. Conversely, in alloys with finer lamellae, a higher density of interfaces exists per unit volume. As the crack advances, it encounters greater resistance at the interfacial intersections, effectively slowing its propagation. This mechanism ultimately enhances the alloy’s plasticity. Figure 12c illustrates the characteristics of a trans-lamellar fracture, where the crack propagates obliquely through the γ/α2 lamellae in a step-like manner. Figure 12d shows the fracture morphology of the TiAl alloy after high-temperature tensile deformation at 850 °C, which is characterized by numerous dimples, indicating a ductile fracture mode.

Figure 12.

Room-temperature and high-temperature tensile fracture of R11 sheet (a) Room temperature, (b) 650 °C, (c) 750 °C, (d) 850 °C.

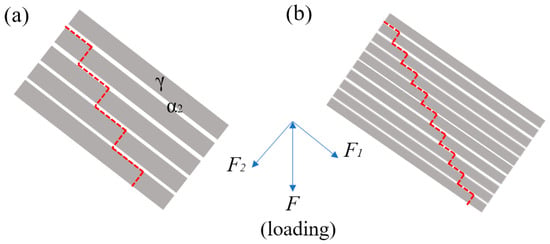

In general, the propagation rate of trans-lamellar cracks is inversely related to the lamellar spacing. Smaller spacing increases the number of γ/α2 interfaces that a crack must traverse per unit advance, thereby enhancing the resistance to crack growth, as illustrated in Figure 13. Additionally, trans-lamellar cracking is favored when the angle between the lamellae and the tensile axis is 40–50°, a phenomenon also observed during the hot compression of a Ti-44Al-4Nb-1Mo alloy [19]. This can be explained by resolving the applied tensile/compressive force into components parallel (F1) and perpendicular (F2) to the lamellae. The component F1 drives crack propagation along the interfaces, while F2 provides the energy to overcome interfacial resistance and propagate the crack through the lamellae. At an orientation angle of 40–50°, F1 and F2 are balanced, facilitating continuous crack propagation. After cyclic heat treatment, the refined lamellar size and spacing in the TiAl alloy reduce the crack propagation rate, thereby improving the alloy’s resistance to crack extension.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of crack penetration. (a) Coarse lamellar spacing. (b) Fine lamellar spacing.

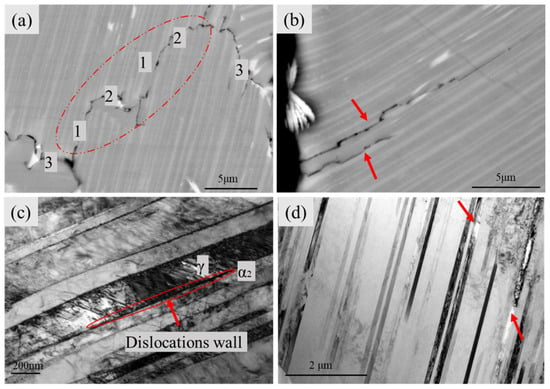

To further investigate the fracture mechanism of the TiAl alloy, the region adjacent to the tensile deformation zone was analyzed, as shown in Figure 14. Figure 14a reveals the presence of multiple cracks. Here, labels “1”, “2”, and “3” denote inter-lamellar, trans-lamellar, and inter-granular cracks, respectively. The series of small cracks labeled “1+2+1+2” in the central area can be collectively considered as a larger trans-lamellar crack (see the red circle). Figure 14b shows the microstructure within the γ/α2 lamellae at 20,000× magnification, where inter-lamellar cracks are seen propagating along the γ/α2 interfaces (gray: γ lamellae; bright white: α2 lamellae). TEM analysis of the lamellar region (Figure 14c) confirms that the wider, dark lamellae are the γ phase, while the adjacent, thinner lamellae are the α2 phase. Within the γ lamellae, dislocations and twins are present simultaneously. High-density dislocation pile-ups are evident at the γ/α2 interfaces, forming dislocation walls. The incompatible deformation between the γ and α2 phases at these interfaces induces significant stress concentration, readily promoting crack initiation, as indicated by the arrow in Figure 14d. Kabir [30] investigated the room-temperature tensile fracture behavior of a TNB alloy heat-treated at 1230–1300 °C and found that cracks primarily initiated at γ grain boundaries, γ/α2 phase boundaries, and the intersections between lamellae and grains. This was attributed to the directional mismatch between individual grains and grain clusters, leading to localized stress concentrations that ultimately resulted in microcracking at the interfaces between the lamellae and spheroidized grains. Regarding crack propagation, as demonstrated in the literature [31], when a crack encounters lamellar bundles within the alloy, its progress is hindered. For the crack to continue advancing, it must either propagate along the interface between the lamellar bundles and the matrix (inter-granular cracking), traverse through the lamellar bundles (trans-lamellar cracking), or initiate a new crack in the γ matrix on the opposite side to release energy. These processes either elongate the crack path or require greater energy, thereby increasing the difficulty of crack extension. In conclusion, the fracture of the alloy after thermal cycling exhibits a mixed mode, involving inter-lamellar, trans-lamellar, and inter-granular cracking. Among these, interlamellar cracking originates from dislocation pile-up at the γ/α2 interfaces within the lamellar structure.

Figure 14.

Microstructure of room-temperature tensile fracture section of R11 sheet (a) Mixed cracking (b) Cracking along the layer (c) Dislocation plugging at the γ/α2 interface (d) Cracking at the γ/α2 interface.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the strength and plasticity of TiAl alloy ingots were improved through a combined rolling and heat treatment process. Experimental methods were employed to investigate the mechanisms underlying the simultaneous enhancement of strength and plasticity. The following conclusions were drawn:

(1) TiAl alloy sheets were fabricated via pack rolling. At low deformation levels, γ/α2 lamellae are retained; at high deformation levels, these lamellae largely disintegrate, and the microstructure transforms into a mixture of equiaxed γ, α2, and β phases.

(2) Cyclic heat treatment was applied to as-rolled TiAl alloys, where the β-phase content decreased gradually with increasing temperature. However, excessively high temperature (1350 °C) resulted in overly coarse lamellar microstructures. At 1250 °C, after 3, 6, and 9 heat treatment cycles, the β-phase content decreased to 11.7%, 5.2%, and 4.1%, respectively, demonstrating efficient β-phase elimination. The mechanism of β-phase elimination was attributed to the β→α→γ+α2 phase transformation pathway, driven by the combined action of distortion energy and defects introduced by rolling deformation, elevated temperature, and cyclic thermal stress during heat treatment.

(3) The strength and plasticity of the TiAl alloy sheet after 9-cycle heat treatment increased by 15.5% and 8.3%, respectively, compared to the hot-isostatic-pressed state. The β-phase elimination primarily provides the precondition for improved plasticity by preventing early crack initiation. The microstructural refinement then provides the main toughening mechanism by effectively hindering crack growth. The tensile fracture exhibited a mixed mode of inter-lamellar, trans-lamellar, and intergranular cracking with the toughening mechanism primarily attributed to the refinement of lamellar colonies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.; Methodology, Z.L., D.S. and L.Y.; Software, K.S.; Validation, Z.L.; Formal Analysis, Z.L.; Investigation, S.T.; Data Curation, C.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.L., D.S. and C.L.; Writing—Review & Editing, S.T. and L.Y.; Visualization, K.S.; Supervision, L.Y.; Project Administration, H.J.; Funding Acquisition, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52201035) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (FRF-TP-24-010A).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Tian Shiwei, Liao Zhiqian, Song Dejun, Li Chong and Sun Kuishan were employed by the company Luoyang Ship Material Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Mu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Sheng, J.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Z.; Yang, G.; Sun, T.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J. A novel approach to coating for improving the comprehensive high-temperature service performance of TiAl alloys. Acta Mater. 2025, 283, 120500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, H.; Mayer, S. Design, processing, microstructure, properties, and applications of advanced intermetallic TiAl alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2013, 15, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, X.; Ren, C.; Song, Z.; Waqar, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, W.; et al. Exceptional strength and ductility in heterogeneous multi-gradient TiAl alloys through additive manufacturing. Acta Mater. 2024, 281, 120395. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.; Peng, H.; Guo, H.; Chen, B. An innovative way to fabricate γ-TiAl blades and their failure mechanisms under thermal shock. Scr. Mater. 2021, 203, 114092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Jiang, H.; Guo, W.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, S. Hot deformation and dynamic recrystallization behavior of TiAl-based alloy. Intermetallics 2019, 112, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.; Erdely, P.; Fischer, F.D.; Holec, D.; Kastenhuber, M.; Klein, T.; Clemens, H. Intermetallic β-solidifying γ-TiAl based alloys− from fundamental research to application. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2017, 19, 1600735. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Fang, H.; Liang, J.; Ding, X.; Zhu, B.; Chen, R. Forming Ru containing eutectoid structure serves as the dislocation storage unit at the lamellar colony boundary of TiAl alloy. Acta Mater. 2025, 285, 120587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Yu, H.; Ning, X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, X. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti43Al9V sheets fabricated via pressure-less sintering and hot pack rolling. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 113918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, R.; Zhang, J.; Lu, X. Achieving enhanced high-temperature strength in Ti-48Al-1Fe alloy sheets by direct hot pack-rolling of powder-sintered billets without cogging. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2025, 335, 118669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, H.; Chladil, H.F.; Wallgram, W.; Zickler, G.; Gerling, R.; Liss, K.-D.; Kremmer, S.; Güther, V.; Smarsly, W. In and ex situ investigations of the β-phase in a Nb and Mo containing γ-TiAl based alloy. Intermetallics 2008, 16, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, H.; Wallgram, W.; Kremmer, S.; Güther, V.; Otto, A.; Bartels, A. Design of novel β-solidifying TiAl alloys with adjustable β/B2-phase fraction and excellent hot-workability. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2008, 10, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloffer, M.; Rashkova, B.; Schöberl, T.; Schwaighofer, E.; Zhang, Z.; Clemens, H.; Mayer, S. Evolution of the ωo phase in a β-stabilized multi-phase TiAl alloy and its effect on hardness. Acta Mater. 2014, 64, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.; Bian, H.; Aoyagi, K.; Chiba, A. Effect of multi-stage heat treatment on mechanical properties and microstructure transformation of Ti–48Al–2Cr–2Nb alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 816, 141321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, S.-W.; Oh, M.-H.; Kim, S.-E. Producing fine fully lamellar microstructure for cast γ-TiAl without hot working. Intermetallics 2020, 120, 106728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, W.; Chen, Z.; Liu, C.; Shi, J.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Q. Enhanced mechanical properties of TiAl alloy through Nb alloying by Triple-wire arc directed energy deposition. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2025, 339, 118800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, H.; Smarsly, W. Light-weight intermetallic titanium aluminides–status of research and development. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 278, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, J.C.; Palm, M. Reassessment of the binary aluminum-titanium phase diagram. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 2006, 27, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.R.; Liu, G.H.; Xu, M.; Wang, B.; Niu, H.; Misra, R.; Wang, Z. Effects of hot-pack rolling process on microstructure, high-temperature tensile properties, and deformation mechanisms in hot-pack rolled thin Ti–44Al–5Nb-(Mo, V, B) sheets. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 764, 138197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Tian, S.; Guo, W.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, S. Hot deformation behavior and deformation mechanism of two TiAl-Mo alloys during hot compression. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 719, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Su, L.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y. Effect of Zener-Hollomon parameter on dynamic recrystallization mechanism and texture evolution of extruded Ti-47Al-2Cr-0.2 Mo alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 927, 147994. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, H.; Wang, Y.; Peng, H.; Miao, K.; Liang, Z.; Xu, L.; Xiao, S.; Gao, B.; Xie, X.; Li, X.; et al. Enhanced compressive creep properties of a Y2O3-bearing Ti–48Al–2Cr–2Nb alloy additively manufactured by electron beam powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 896, 146277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, M.; Zhou, T.; Hu, L.; Shi, L.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Y. Deformation behavior and dynamic recrystallization mechanism of a novel high Nb containing TiAl alloy in (α+ γ) dual-phase field. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 945, 169250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; He, A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, H. Investigation on the microstructure evolution and dynamic recrystallization mechanisms of TiAl alloy at elevated temperature. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 968–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsui, T.; Mizuta, K. Detrimental effects of βo-phase on practical properties of TiAl Alloys. Metals 2024, 14, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molénat, G.; Galy, B.; Musi, M.; Toualbi, L.; Thomas, M.; Clemens, H.; Monchoux, J.-P.; Couret, A. Plasticity and brittleness of the ordered βo phase in a TNM-TiAl alloy. Intermetallics 2022, 151, 107653. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, B.; Guo, T.; Zhang, J.; Yang, F.; Wu, J.; Mao, X. Effect of Ta on microstructure and property of β titanium aluminide sheet. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2019, 48, 2677–2682. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; He, J.; Cao, R.; Luo, X.; Chang, J.; Zhao, Z. On the role of weak interface in the high cycle fatigue damage mechanism at elevated temperature in forged TNM-TiAl alloy. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 202, 109242. [Google Scholar]

- Prithiv, T.S.; Bhuyan, P.; Pradhan, S.K.; Sarma, V.S.; Mandal, S. A critical evluation on efficacy of recrystallization vs. strain induced boundary migration in achieving grain boundary engineered microstructure in a Ni-base superalloy Acta. Materialia 2018, 146, 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Neogi, A.; Janisch, R. Unravelling the lamellar size-dependent fracture behavior of fully lamellar intermetallic γ-TiAl. Acta Mater. 2022, 227, 117698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.R.; Bartsch, M.; Chernova, L.; Kelm, K.; Wischek, J. Correlations between microstructure and room temperature tensile behavior of a duplex TNB alloy for systematically heat treated samples. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 635, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Tian, J. The effect of boron addition on the deformation behavior and microstructure of β-solidify TiAl alloys. Mater. Charact. 2018, 145, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.