Research on the Shear Forces and Fracture Behavior of Self-Riveting Friction Stir Lap Welding Joints with Medium-Thick Aluminum/Steel Plates

Abstract

1. Introduction

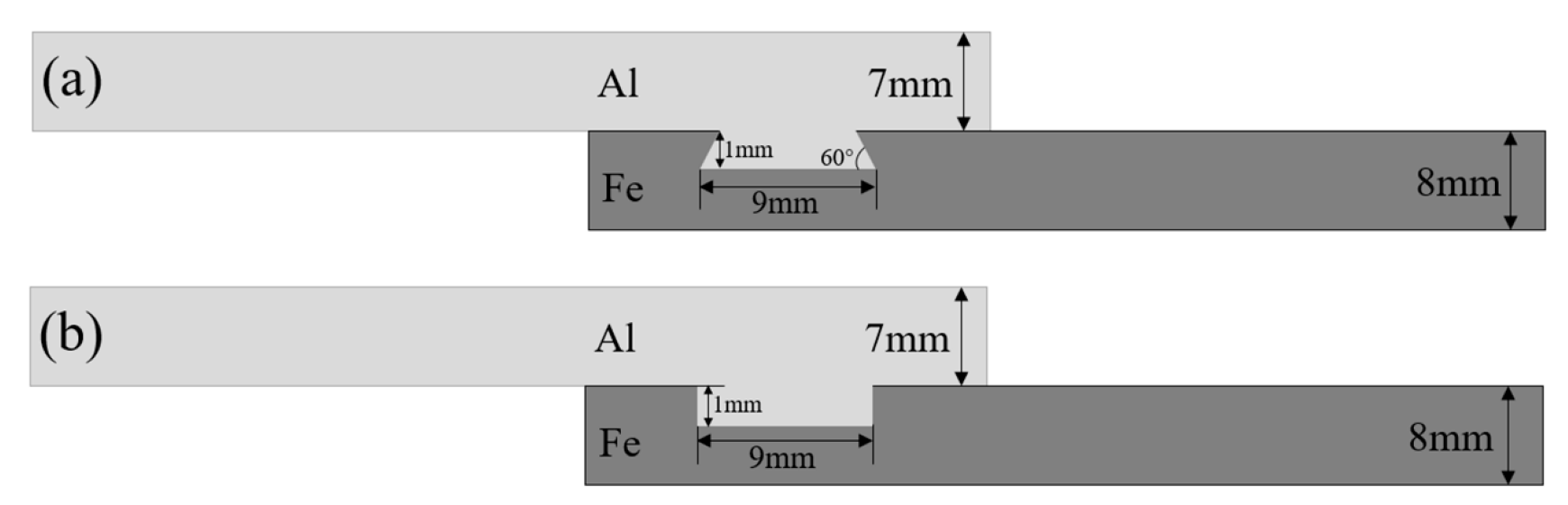

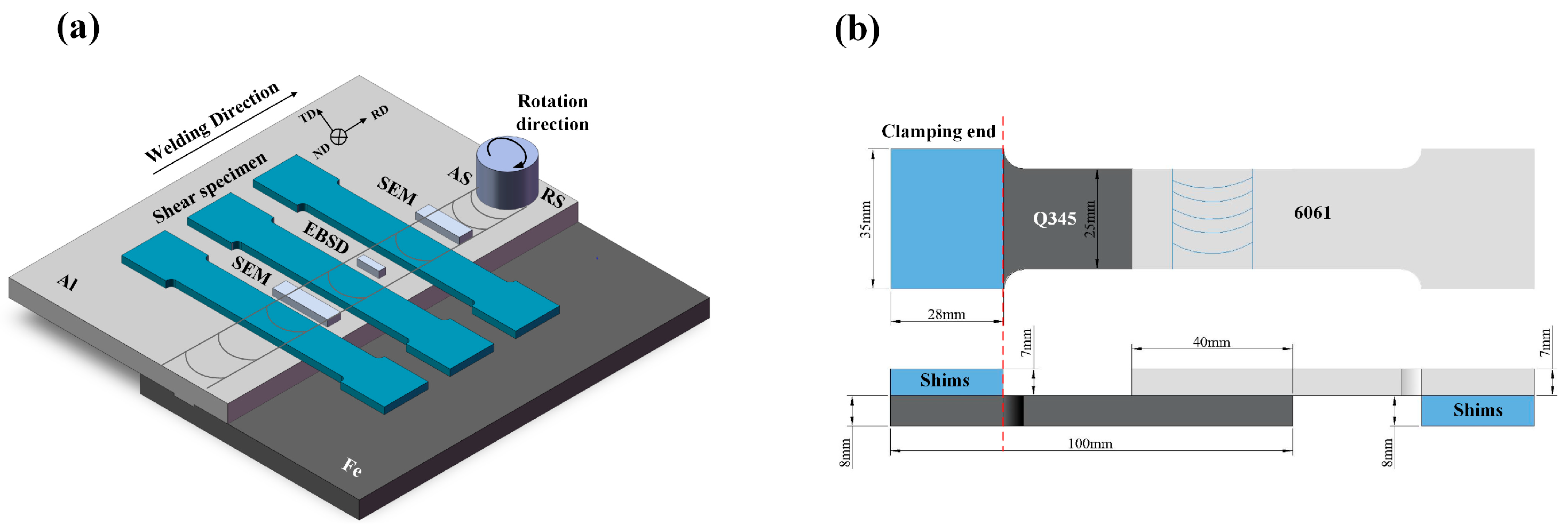

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

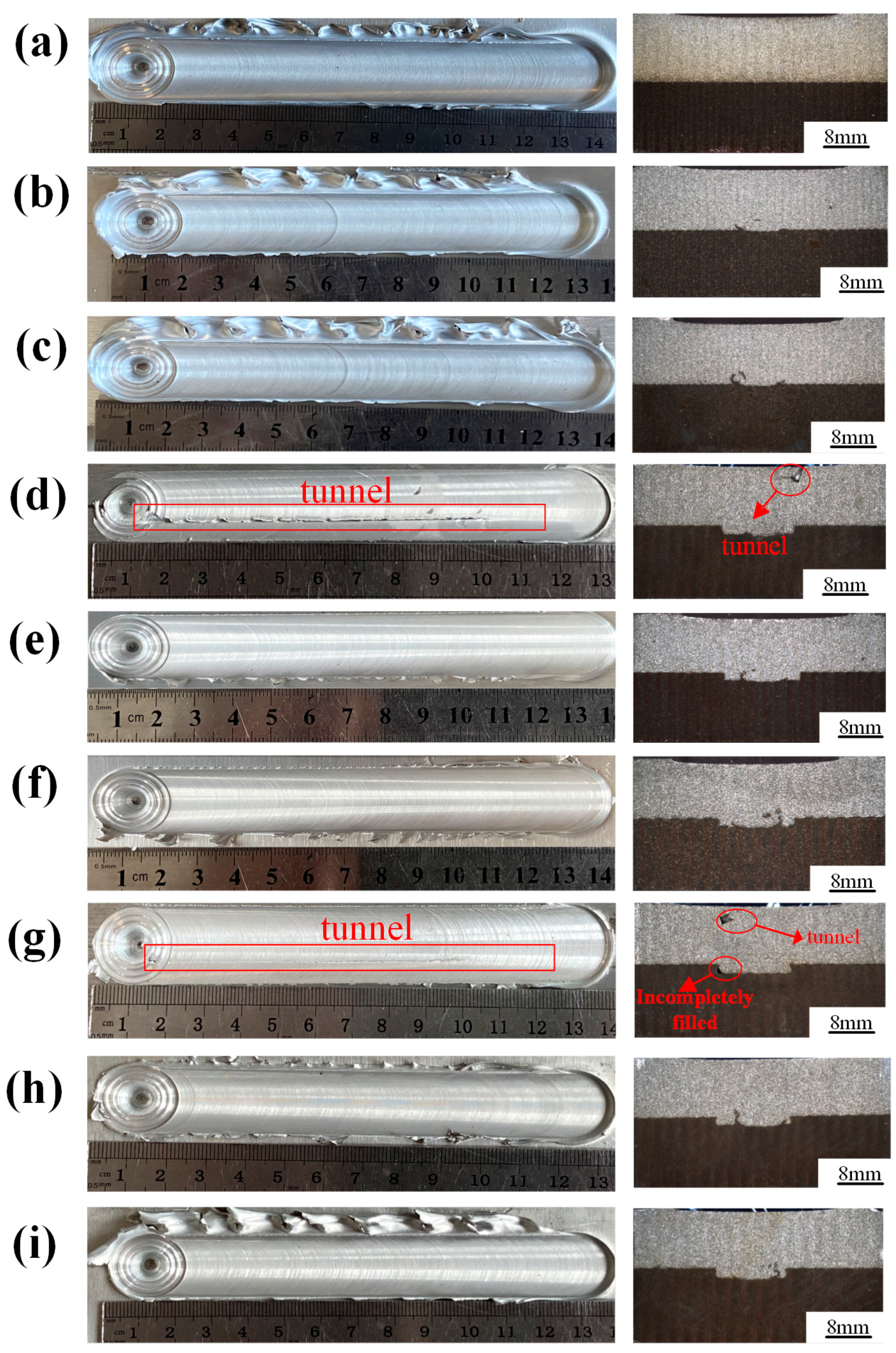

3.1. Weld Appearance

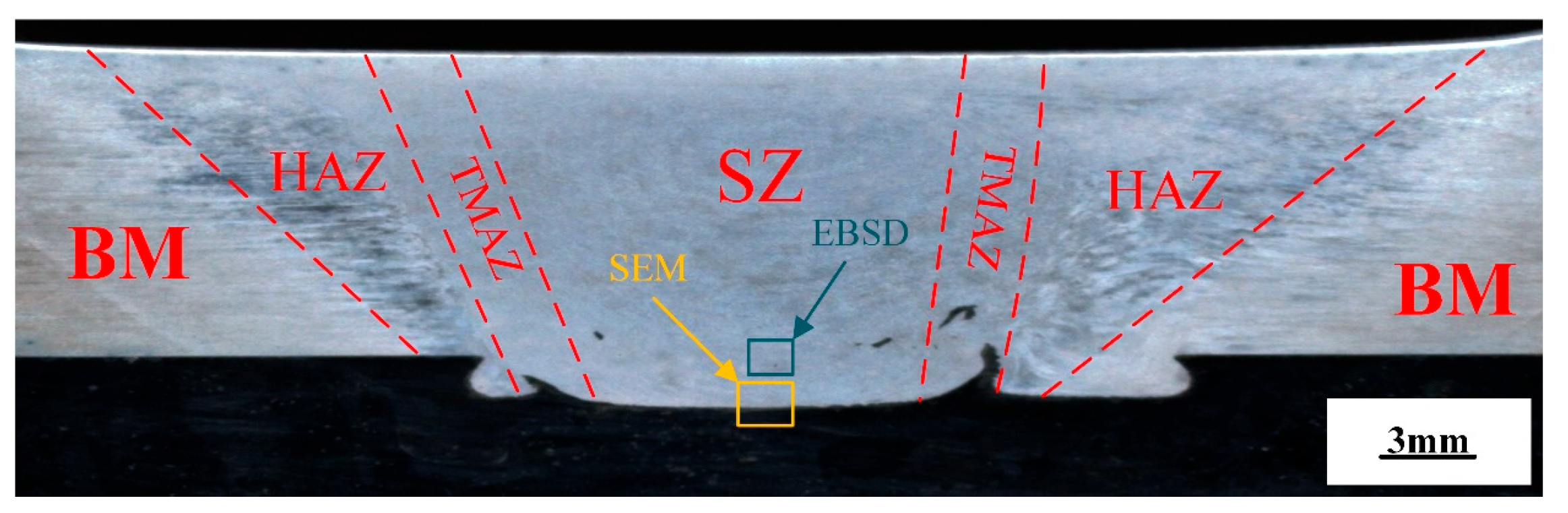

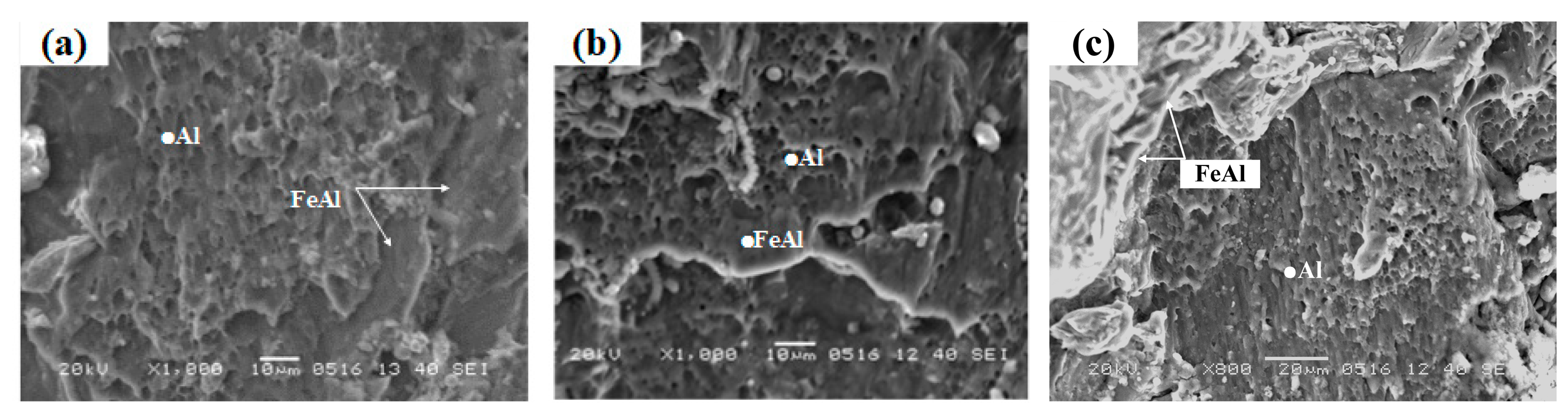

3.2. Microstructure Evolution of SRFSLW Joint

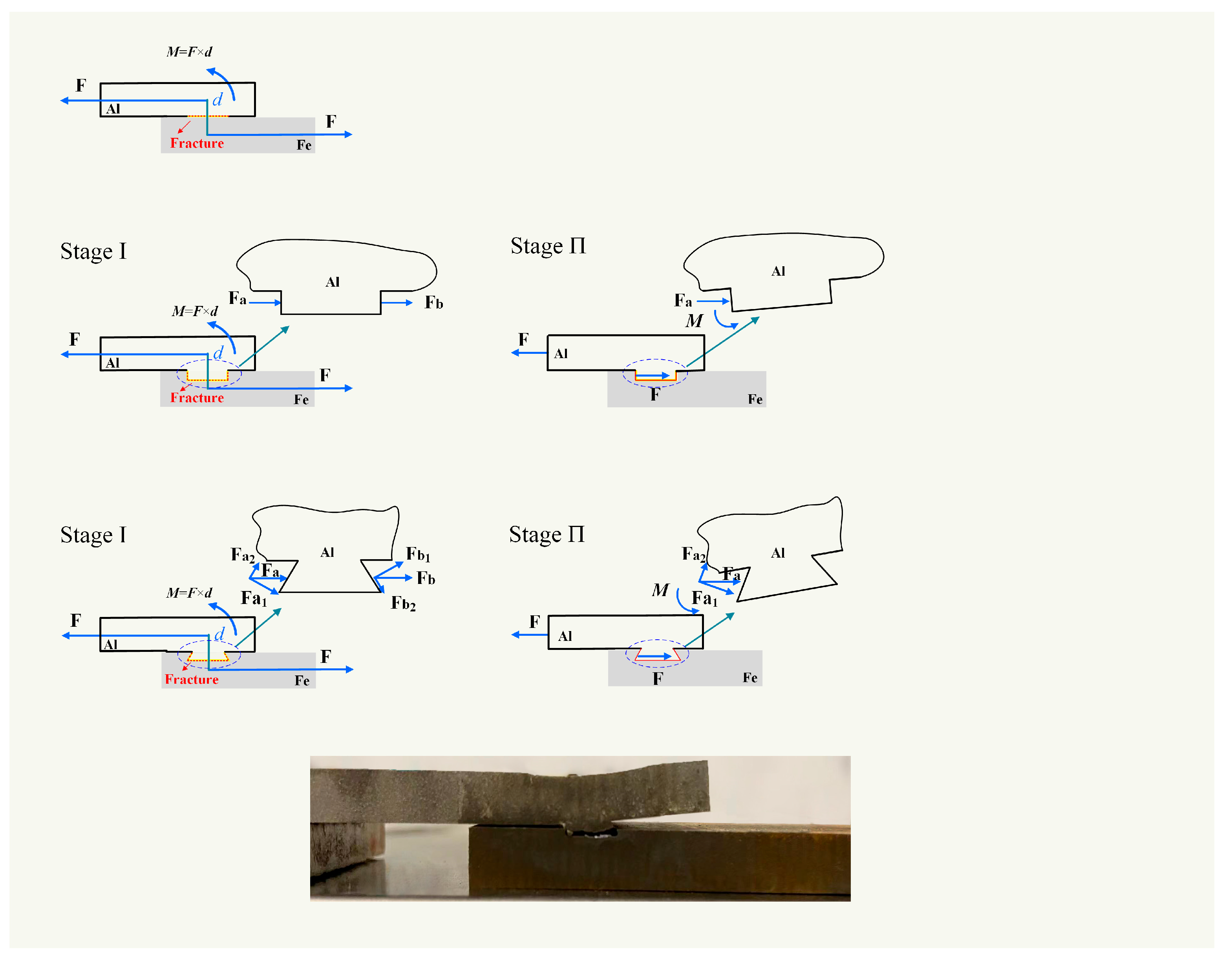

3.3. Shear Forces of SRFSLW Joint

3.4. Mechanism of Joint Strengthening

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, M.; Tao, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S. Hybrid Resistance-Laser Spot Welding of Aluminum to Steel Dissimilar Materials: Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Mater. Des. 2022, 221, 111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, Z.; Chen, S.; Gao, Y.; Tian, X.; Duan, R.; Liu, Z.; Dong, J. A Novel Method for Improving the Plastic Flow and Mechanical Properties of Spray-Formed 7055-T76 (Sc-Added) Aluminum Alloy FSW Joint by Rotating Magnetic Field. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Huang, Y. Friction Stir Welding of Dissimilar Aluminum Alloys and Steels: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 99, 1781–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J. Advanced Lightweight Materials for Automobiles: A Review. Mater. Des. 2022, 221, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lai, X.; Zhu, P.; Wang, W. Lightweight Design of Automobile Component Using High Strength Steel Based on Dent Resistance. Mater. Des. 2006, 27, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.T.; Omura, S.; Tokita, S.; Sato, Y.S.; Tatsumi, Y. Drastic Improvement in Dissimilar Aluminum-to-Steel Joint Strength by Combining Positive Roles of Silicon and Nickel Additions. Mater. Des. 2023, 225, 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Shen, Y. Effects of Preheating Treatment on Temperature Distribution and Material Flow of Aluminum Alloy and Steel Friction Stir Welds. J. Manuf. Process. 2017, 29, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschut, G.; Janzen, V.; Olfermann, T. Innovative and Highly Productive Joining Technologies for Multi-Material Lightweight Car Body Structures. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narsimhachary, D.; Dutta, K.; Shariff, S.M.; Padmanabham, G.; Basu, A. Mechanical and Microstructural Characterization of Laser Weld-Brazed AA6082-Galvanized Steel Joint. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 263, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Sidhar, H.; Mishra, R.S.; Hovanski, Y.; Upadhyay, P.; Carlson, B. Evaluation of Intermetallic Compound Layer at Aluminum/Steel Interface Joined by Friction Stir Scribe Technology. Mater. Des. 2019, 174, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qin, G.; Geng, P.; Ma, X. Interfacial Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Friction Welded Al/Steel Dissimilar Joints. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 49, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Ni, J. A Review of Friction Stir–Based Processes for Joining Dissimilar Materials. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 104, 1709–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaman, S.Y.; Cho, H.-H.; Das, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Hong, S.-T. Microstructure and Mechanical/Electrochemical Properties of Friction Stir Butt Welded Joint of Dissimilar Aluminum and Steel Alloys. Mater. Charact. 2019, 154, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabraeili, R.; Jafarian, H.R.; Khajeh, R.; Park, N.; Kim, Y.; Heidarzadeh, A.; Eivani, A.R. Effect of FSW Process Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the Dissimilar AA2024 Al Alloy and 304 Stainless Steel Joints. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 814, 140981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, P.; Morimura, M.; Ma, H.; Ma, Y.; Ma, N.; Liu, H.; Aoki, Y.; Fujii, H.; Qin, G. Elucidation of Intermetallic Compounds and Mechanical Properties of Dissimilar Friction Stir Lap Welded 5052 Al Alloy and DP590 Steel. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 906, 164381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.; Ganguly, S. Distribution of Intermetallic Compounds in Dissimilar Joint Interface of AA 5083 and HSLA Steel Welded by FSW Technique. Intermetallics 2022, 151, 107734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Li, R. Study on Low Axial Load Friction Stir Lap Joining of 6061-T6 and Zinc-Coated Steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2019, 50, 4642–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Medina, G.; Lopez, H.; Miranda-Pérez, A.; Hurtado-Delgado, E. Effect of Grain Recrystallization on Stir Zone and Mechanical Property Behavior of TRIP 780 Steel. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2020, 27, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Haghshenas, M.; Gerlich, A.P. Role of Welding Parameters on Interfacial Bonding in Dissimilar Steel/Aluminum Friction Stir Welds. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2015, 18, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.-H.; Liu, H.; Ji, S.-D.; Yan, D.-J.; Zhao, H.-X. Diffusion Bonding of Al-Mg-Si Alloy and 301L Stainless Steel by Friction Stir Lap Welding Using a Zn Interlayer. Materials 2022, 15, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myśliwiec, P.; Kubit, A.; Derazkola, H.A.; Szawara, P.; Slota, J. Feasibility Study on Dissimilar Joint between Alclad AA2024–T3 and DC04 Steel by Friction Stir Welding. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, A.; Sadeghi, B.; Sadeghian, B.; Taherizadeh, A.; Szkodo, M.; Cavaliere, P. Temperature Evolution, Material Flow, and Resulting Mechanical Properties as a Function of Tool Geometry during Friction Stir Welding of AA6082. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 10655–10668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, B.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, G.; Miao, Y. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Aluminum-Steel Dissimilar Metal Welded Using Arc and Friction Stir Hybrid Welding. Mater. Des. 2023, 225, 111520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hao, Z.; Wang, K.; Qiao, K.; Xue, K.; Liu, Q.; Han, P.; Wang, W.; Zheng, P. Effect of Ni Interlayer on Interfacial Microstructure and Fatigue Behavior of Friction Stir Lap Welded 6061 Aluminum Alloy and QP1180 Steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 180, 108096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, K.; Beygi, R.; Alikhani, A.; Marques, E.A.S.; Khalfallah, A.; da Silva, L.F.M. Study on Friction Stir Diffusion Bonding of Aluminum to Zinc-Coated Steel: A Comparison to Weld-Brazing. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 43, 111833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lim, Y.C.; Li, Y.; Tang, W.; Ma, Y.; Feng, Z.; Ni, J. Effects of Process Parameters on Friction Self-Piercing Riveting of Dissimilar Materials. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2016, 237, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wan, L.; Meng, X.; Liu, H.; Li, H. Self-Riveting Friction Stir Lap Welding of Aluminum Alloy to Steel. Mater. Lett. 2016, 185, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shan, H.; Niu, S.; Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Ma, N. A Comparative Study of Friction Self-Piercing Riveting and Self-Piercing Riveting of Aluminum Alloy AA5182-O. Engineering 2021, 7, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza-E-Rabby, M.; Ross, K.; Overman, N.R.; Olszta, M.J.; McDonnell, M.; Whalen, S.A. Joining Thick Section Aluminum to Steel with Suppressed FeAl Intermetallic Formation via Friction Stir Dovetailing. Scr. Mater. 2018, 148, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, T.; Wan, L.; Meng, X.; Zhou, L. Material Flow and Mechanical Properties of Aluminum-to-Steel Self-Riveting Friction Stir Lap Joints. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 263, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Gao, J.; Xie, Y.; Huang, T.; Dong, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, N.; Huang, Y. Extrinsic-Riveting Friction Stir Lap Welding of Al/Steel Dissimilar Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, H.; Ma, Y.; Niu, S.; Yang, B.; Lou, M.; Li, Y.; Lin, Z. Friction Stir Riveting (FSR) of AA6061-T6 Aluminum Alloy and DP600 Steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 295, 117156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveen Kumar, P.; Jayakumar, K.; Senthur Vaishnavan, S. FSW on AA5083 H-111 and AA5754 H-111 Dissimilar Plates with Scandium Intermetallic Layer. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 72, 2294–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, M.; Abdel-Gwad, A.; Omran, A.M.; Gökçe, B.; Sahraeinejad, S.; Gerlich, A.P. Friction Stir Weld Assisted Diffusion Bonding of 5754 Aluminum Alloy to Coated High Strength Steels. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Kimura, A.; Tsuda, N.; Serizawa, H.; Chen, D.; Je, H.; Fujii, H.; Ha, Y.; Morisada, Y.; Noto, H. Effects of Mechanical Force on Grain Structures of Friction Stir Welded Oxide Dispersion Strengthened Ferritic Steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 455, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Nelson, T.W. Influence of Heat Input on Post Weld Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Friction Stir Welded HSLA-65 Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 556, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Logé, R.E. A Review of Dynamic Recrystallization Phenomena in Metallic Materials. Mater. Des. 2016, 111, 548–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourdet, S.; Montheillet, F. A Model of Continuous Dynamic Recrystallization. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 2685–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Belyakov, A.; Kaibyshev, R.; Miura, H.; Jonas, J.J. Dynamic and Post-Dynamic Recrystallization under Hot, Cold and Severe Plastic Deformation Conditions. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 60, 130–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Gao, S.; Yin, Q.; Shi, L.; Kumar, S.; Zhao, W. Research on the Mechanical Properties and Fracture Mechanism of Ultrasonic Vibration Enhanced Friction Stir Welded Aluminum/Steel Joint. Mater. Charact. 2024, 207, 113534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot, F.; Gueydan, A.; Martinez, M.; Moisy, F.; Hug, E. A Correlation between the Ultimate Shear Stress and the Thickness Affected by Intermetallic Compounds in Friction Stir Welding of Dissimilar Aluminum Alloy–Stainless Steel Joints. Metals 2018, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourali, M.; Abdollah-zadeh, A.; Saeid, T.; Kargar, F. Influence of Welding Parameters on Intermetallic Compounds Formation in Dissimilar Steel/Aluminum Friction Stir Welds. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 715, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mg | Si | Cu | Mn | Zn | Fe | Cr | Ti | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8~1.2 | 0.4~0.8 | 0.15~0.4 | ≤0.15 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.70 | 0.04~0.35 | ≤0.15 | Bal. |

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Ni | Cr | Cu | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.20 | 0.55 | 1.60 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.40 | Bal. |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation After Fracture (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6061-T6 | ≥240 | ≥290 | ≥10 |

| Q355D | ≥355 | 470~630 | ≥22 |

| Group | Plunge Depth (mm) | Groove Type | Rotation Speed (rpm) | Welding Speed (mm/min) | Spindle Inclination Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.1 | Non-groove | 600 | 100 | 2.5 |

| A2 | 0.3 | ||||

| A3 | 0.5 | ||||

| B1 | 0.1 | Rectangular groove | |||

| B2 | 0.3 | ||||

| B3 | 0.5 | ||||

| C1 | 0.1 | Dovetail groove | |||

| C2 | 0.3 | ||||

| C3 | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, X.; Wang, J.; Zhai, C.; He, Y.; Chen, S.; Jin, Y.; Yu, R.; Maksymov, S. Research on the Shear Forces and Fracture Behavior of Self-Riveting Friction Stir Lap Welding Joints with Medium-Thick Aluminum/Steel Plates. Metals 2026, 16, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010127

Tian X, Wang J, Zhai C, He Y, Chen S, Jin Y, Yu R, Maksymov S. Research on the Shear Forces and Fracture Behavior of Self-Riveting Friction Stir Lap Welding Joints with Medium-Thick Aluminum/Steel Plates. Metals. 2026; 16(1):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010127

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Xiongwen, Jianxin Wang, Chang Zhai, Yabin He, Shujin Chen, Yiming Jin, Rui Yu, and Sergii Maksymov. 2026. "Research on the Shear Forces and Fracture Behavior of Self-Riveting Friction Stir Lap Welding Joints with Medium-Thick Aluminum/Steel Plates" Metals 16, no. 1: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010127

APA StyleTian, X., Wang, J., Zhai, C., He, Y., Chen, S., Jin, Y., Yu, R., & Maksymov, S. (2026). Research on the Shear Forces and Fracture Behavior of Self-Riveting Friction Stir Lap Welding Joints with Medium-Thick Aluminum/Steel Plates. Metals, 16(1), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010127