Abstract

This study addresses the fundamental problem of representing the rheological properties of heterostructured materials composed of metals that differ significantly in their crystal structure, stacking fault energy, and related characteristics. The necessity of accounting for essential strengthening mechanisms is highlighted. The study is based on experimental results related to the fabrication of a multilayer, heterogeneous system via multistage wire drawing, supported by microstructural analysis, microhardness measurements, and numerical simulations employing various flow-stress models. A discussion is presented regarding the effectiveness of these models in representing the deformation behavior of the investigated materials. The primary materials examined were a multilayer system composed of microalloyed steel and titanium. The obtained results indicate that, in addition to incorporating strengthening mechanisms, it is necessary to consider significant microstructural changes affecting microstructure evolution—particularly grain refinement induced by continuous recrystallization and the effects of strain hardening. Moreover, the findings point to the potential intensification of strengthening associated with pile-up mechanisms, linked to the development of dislocation substructures and the possible fragmentation of the hard phase in the vicinity of the more ductile microalloyed steel phase. In conclusion, the discussion integrates measurements of rheological properties obtained through tensile tests, supported by microstructural analysis, digital image correlation (DIC), and microhardness measurements, which collectively demonstrate the effectiveness of the adopted analytical approach.

1. Introduction

Heterogeneous structural materials—characterized by variations in both microstructure and rheological properties—have, in recent years, emerged as an effective alternative to conventional structural materials produced through alloying and heat treatment [1,2]. Metal matrix heterogeneous materials constitute a new class of materials, now starting to make a major industrial impact in fields as diverse as aerospace, automotives, and electronics [3,4,5,6]. In this case, increasingly often, heterostructured materials are used, which can offer a unique combination of functional properties, significantly exceeding the properties of the constituent materials [7,8,9]. On an industrial scale, various technologies for producing multilayer materials have been developed, especially in the form of sheets and strips, e.g., by means of accumulative bonding, impulse, or explosive welding [10]. At the same time, other multilayer or heterogeneous systems have been proposed and effectively implemented for production, e.g., products manufactured by rotary swaging [11], wire drawing, or extrusion [12,13,14]. Compared with their homogeneous structured counterparts, heterogeneous metals and alloys have achieved a combination of superior mechanical properties, such as higher strength, better ductility, higher work hardening rate, and greater fracture resistance [1,15,16,17,18]. Many combinations of engineering materials can be used to build heterogeneous materials. One particularly attractive option is a structure based on steel as a common structural material. An overview of steel-based composites, in which consideration was given to conventional metal–matrix composites—where steel is combined with another metal, ceramic, or polymer—is presented in [19]. In addition, fully steel composites are defined, in which both components of the structure are developed within the steel itself. Heterogeneous materials can be defined as materials with dramatic heterogeneity in strength from one domain area to another. This strength heterogeneity can be caused by microstructural heterogeneity, crystal structure heterogeneity, or compositional heterogeneity. The domain sizes could be in the range of micrometers to millimeters, and the domain geometry can vary to form very diverse material systems [20]. Particularly attractive is the possibility of designing heterogeneous systems, for example, multilayer configurations, in which the distinct characteristics of the constituent materials enable the tailoring of desirable service properties. Such concepts have been known for centuries, with the most renowned historical example being “Damascus” steel. In contemporary applications, heterogeneous materials include systems composed of various metals (e.g., Cu and Nb) used in semiconductor manufacturing using methods such as multiscale Cu matrix embedding and parallel Nb nanotubes filled with Cu nanofilaments. These nanocomposite conductors are excellent candidates for generating intense pulsed magnetic fields (>90 T) [12]. The unique properties of heterogeneous materials arise from the action of mechanisms operating not only within each individual constituent but also from their mutual interactions, which generate additional effects stemming from the synergistic combination of strengthening processes such as strain hardening, dislocation substructure strengthening, precipitation strengthening, and solid-solution strengthening. As stated by David Embury in [21], “The concept of architectured materials has a lot of relevance to industry. There is great interest in lightweight structural applications for different demands, including energy transport and energy absorption, using architectural materials. Take titanium alloys. If we could make them transform like steel to achieve very high strengths, they would be applicable for several new purposes. The concept of hybrids is known. What we are looking at now, are new combinations of materials and new ways of fabricating complex geometries that is new ways of combining existing knowledge to design new engineering solutions”. A particularly interesting approach appears to be the combination of the effects of heterogeneity resulting from the use of different materials and the strong refinement of the microstructure achieved through severe plastic deformation (SPD). Recent studies show that the strength of ultrafine-grained (UFG) materials processed by SPD techniques is typically much higher than that predicted by the Hall–Petch relation. The physical nature of this phenomenon is related to the fact that the strength properties of UFG materials arise not only from the presence of ultrafine grains, but also from other nanostructural features, including the formation of subgrain dislocation structures, nanotwins, nanosized second-phase precipitates, and the grain boundary structure—their nonequilibrium character and the presence of impurity or alloying-element segregations at the grain boundaries [22]. In another study, multilayer steel–Ti systems subjected to very intense deformation through multistage wire drawing were analyzed [23]. In this way, research material was obtained that fits the characteristics of new structural materials described above. The results obtained from the characterization and assessment of the formability of the investigated materials will be useful for designing new heterostructural materials as well as for numerical simulations of their deformation processes. Although macroscopic bulk tests provide important information about materials, the fundamental phenomena under analysis occur at the micro- and nanoscale. Therefore, research methods must provide adequate resolution and enable the recording of results at this level, especially in relation to heterogeneous materials. In the studies presented here, the digital image correlation (DIC) method, particularly micro-DIC, was used to determine strain paths during mechanical testing. This technique may prove to be ideal for studying material deformation, especially in ultrafine-grained and nanostructured materials (strong strain gradients, highest strain measurement accuracy due to the small observation area, data extraction, and comparison with data from analyses such as the finite element method).

2. Materials and Methods

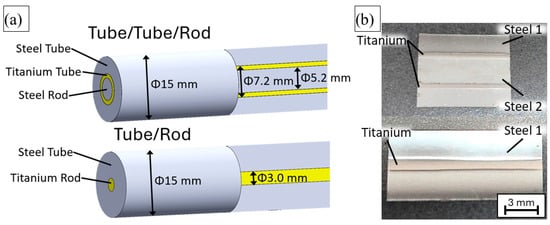

The research material consisted of multilayer, axisymmetric systems prepared in the form of two types of specimens: a tube/tube/rod system (TTR) and a tube/rod system (TR). The experimental work was carried out in two main stages. In the first stage, specimens composed of heterogeneous steel–titanium systems were produced. The TTR specimens were fabricated by placing a 7.2 mm × 1 mm titanium tube inside a steel 1 tube with an outer diameter of 15 mm, with a 5.2 mm steel 2 rod positioned in the interior of the titanium tube. The TR specimens were made from a steel 1 tube, also with an outer diameter of 15 mm, inside which a 3 mm titanium rod was placed; schematics for both systems are presented in Figure 1a. In the TTR system, the titanium cross-sectional area accounted for 11% of the total cross-section, whereas in the TR system, it accounted for 4%. All materials were in the annealed condition. The multilayer systems prepared in this manner were then annealed at 700 °C for 20 min in a flowing argon atmosphere. The adopted annealing conditions were selected as a compromise between the annealing requirements of steel and titanium and were based on microstructural observations conducted after various combinations of temperature and time, with the aim of obtaining a fully annealed microstructure in both materials. Both types of specimens were subjected to calibration rolling, which reduced the outer diameter of the investigated systems from 15 mm to 6.5 mm. Longitudinal sections of the produced samples are shown in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

Schematic of assembled TTR and TR systems (a); longitudinal section of TTR and TR samples at a diameter of 6.5 mm after caliber rolling (b).

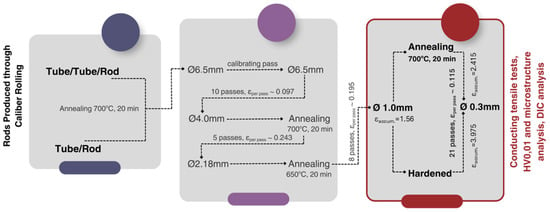

In the subsequent stage, drawing processes were performed on the specimens prepared by calibration rolling, in accordance with the scheme and conditions shown in Figure 2. The chemical compositions of the materials used in the study, as well as their initial characteristics, are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

The flowchart and process parameters used in experimental studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of research materials.

Heterogeneous materials produced in this way were subjected to mechanical and microstructural testing, as well as to analysis of local strain and stress distribution using a digital image correlation (DIC)–micro-DIC system. The tensile test of 1 mm and 0.3 mm wires was carried out under ex situ conditions using a heating–tensometric stage with a maximum load capacity of 5 kN. During deformation, a crosshead speed of 5 mm/s was applied to all specimens. The experiments were coupled with a microscale digital image correlation system (micro-DIC, Q-400, Dantec Dynamics, Neu-Ulm, Germany). Observations were performed using two high-resolution cameras (5 MPx) and a dedicated microscope in which the lenses were arranged at an angle of 17°, enabling analysis of the specimen along three different axes. Data processing was conducted using Istra4D v4.10 software. Prior to testing, the specimens that underwent micro-DIC observations were subjected to grinding, achieving the longitudinal section of the wire and polishing, followed by etching. The etching process was carried out in such a way as to reveal fine particles on the surface, forming stochastically distributed speckle patterns.

The aim of the research was to assess anomalies in the deformation mechanisms and kinetics of the produced incoherent metal-to-metal composites. Differences in hardening ability, both locally and globally within the investigated specimens, were revealed by microhardness measurements. The correlations between microstructure and mechanical state distributions in the heterogeneous specimens were examined using micrographs taken with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). All investigations were conducted on the longitudinal section of the wire samples.

3. Results and Discussion

During the passage of the investigated multilayer material through the drawing die, the soft steel layer deforms faster than the hard Ti layer in the transverse direction. This leads to the development of tensile stresses in the soft layer and compressive stresses in the hard layer. At the same time, due to the specific stress–strain state characteristic of the drawing process, the tensile stress in the hard Ti layer increases, as it is less plastic. Therefore, mechanical incompatibility in this layered structure transforms the tensile stress distribution typical of the drawing process into complex, non-uniform stress states.

One of the characteristic features of the wire drawing process is the high non-uniformity of stress and strain across the cross-section of the product. The intensity of this non-uniformity naturally increases with the degree of diameter reduction in the drawn wire. The situation becomes even more complex when a heterogeneous material, as in the present case, is subjected to the drawing process. In such circumstances, numerical simulation based on appropriate rheological models of the investigated materials is indispensable [24].

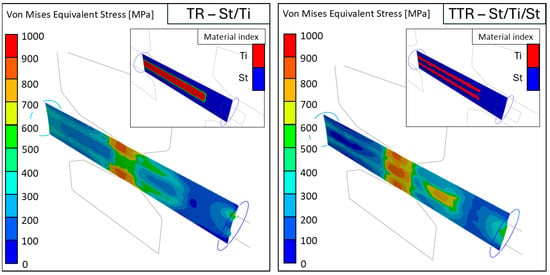

Figure 3 presents representative results of numerical simulations of stress intensity (von Mises) distributions, produced using the Forge NxT v4.0 software. The illustrated stress distributions clearly indicate significant differences in the stress states of the investigated TTR and TR systems. It can be clearly observed that the stress intensity accumulates in the more plastic layers, i.e., steel. This situation causes an increase in longitudinal stress in the hard layers, i.e., Ti, which consequently leads to loss of cohesion and fragmentation.

Figure 3.

Representative results of numerical simulations for the investigated multilayer systems. Examples of stress intensity distributions (Mises equivalent stress) in the cross-sections of TR and TTR samples after the second pass of the wire.

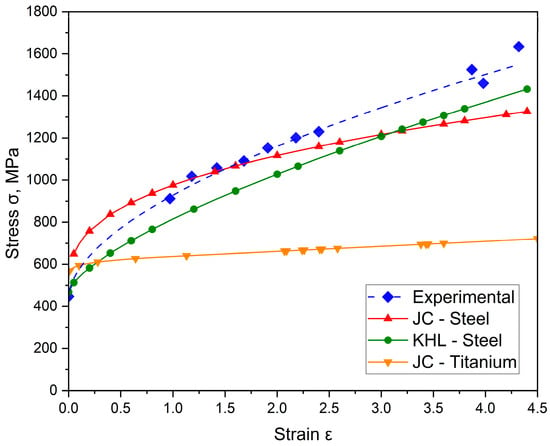

The problem of properly representing the rheological properties of both the investigated steels and Ti, as well as of the entire multilayer system, required the selection of appropriate models and their calibration based on plastometric tests. One of the key criteria for selecting a suitable flow stress model for the entire investigated steel/Ti system was the correct representation of phenomena that are essential from the standpoint of studies on the development of dislocation substructure and the intense refinement of the microstructure in steel, which is the base material in the multilayer system. At the current stage of the research, the decision was made to select two models, namely the Johnson–Cook (J-C) model [25] (Equation (1)) and the Khan–Huang–Liang (KHL) model [26] (Equation (2)), the coefficients for the equations are presented respectively in Table 2 and Table 3.

where σ—flow stress; ε—plastic strain; Tm—melting temperature; T—current temperature; Tr—reference temperature; , —reference strain rate; —current strain rate; σo, A, Ky, B, B*, n0, n1, C, m—material constants.

Table 2.

Coefficients of the JC model identified for the investigated materials.

Table 3.

Coefficients of the KHL model identified for the investigated materials.

The selection of the Johnson–Cook (J–C) model was motivated by its well-established capability to accurately represent the rheological behavior of both the investigated microalloyed steel and titanium. In contrast, the choice of the KHL model was guided by its ability to effectively capture microstructural phenomena occurring in the studied materials under the conditions of the applied multistage wire-drawing process. The effects of the crystal structure differences, which represent the core idea of this research, were incorporated into the material constants, which were obtained by calibrating the individual constitutive models for each material. The effects of interpass annealing, which was used in the deformation process, were included in the rheological models through the total accumulated strain.

The original formulation of the KHL model was proposed by Khan and Huang in 1992 [27] and was based on the decomposition of the total deformation rate into elastic and plastic components. Subsequently, the model was extended to account for the coupled dependence of work hardening on strain, strain rate, temperature, and grain size. This viscoplastic constitutive model incorporates a bilinear Hall–Petch-type relationship, enabling accurate representation of the mechanical response of nanocrystalline materials, including the grain-size dependence of work hardening. The KHL model has demonstrated high accuracy over a broad range of grain sizes, spanning from tens of nanometers to several hundred micrometers, as well as over a wide range of strain rates [26,27]. Moreover, the model is particularly well-suited for the analysis of deformation processes in ultrafine-grained (UFG) structures and offers the additional advantage of straightforward implementation within finite element modeling (FEM) frameworks [28].

The results of numerical simulations performed using the developed constitutive models, together with their comparison to experimental data for the constituent materials of the investigated multilayer systems, are presented in Figure 4. The experimental data were determined for steel based on the yield strength obtained from tensile tests on drawn wires with decreasing diameters and, consequently, higher values of accumulated strain.

Figure 4.

Representative results of numerical simulations of flow stress for each component of the investigated multilayer systems compared with steel experimental data.

The comparison of two different multilayer systems (TTR vs. TR) in the present study was intended to examine how the sequence and the number of rheologically different layers affect the mechanical response of the entire heterogeneous system. For example, a new net-shape plating technology for axisymmetric metallic parts using rotary swaging was presented in [29]. Several Cu/Al combinations have been investigated. It has been shown that the joint between the base workpiece and the coating material is tighter when the inner workpiece has a higher yield strength than the outer workpiece.

One of the aims of the present study was to create conditions under which the investigated steel/Ti heterogeneous systems would form a heterostructured material in which titanium particles of various sizes—obtained because of the loss of cohesion of Ti layers subjected to very large deformations—would act as reinforcement in the steel matrix [1,30,31,32,33,34].

When the hard layers begin to undergo plastic deformation, a state of exhaustion of plastic deformability is reached, and a process of loss of cohesion and fragmentation initiates within them. Differences in the intensity of these processes can be observed at the stage of a severe reduction in the diameter of the drawn wires. Figure 5 presents representative results of microstructural observations in TTR and TR system wires with diameters reduced to 1 mm. When analyzing the influence of the mechanical state on microstructure development in the investigated multilayer systems, attention should be paid to the role of the interpass annealing process. Strong accumulation of strain during the wire drawing processes led to the occurrence of severe plastic deformation (SPD) effects, manifested by a highly refined microstructure of the steel layers. This effect is observed only in the steel layers, whereas the Ti layers accommodate deformation through pronounced work hardening and grain elongation.

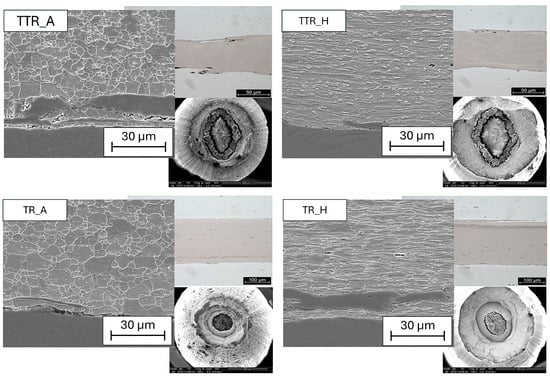

Figure 5.

Representative scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and optical-light images from the steel–Ti interfacial regions and fractured specimens after tensile tests of multilayer samples drawn to a diameter of 1 mm, in the strain-hardened condition (TTR_H, TR_H) and after annealing (TTR_A, TR_A).

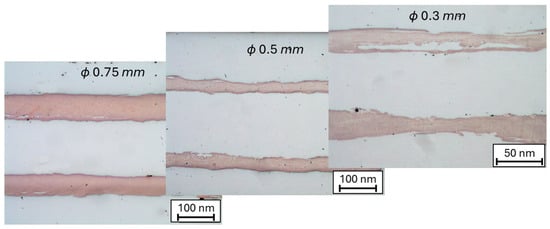

The results of scanning electron microscopy and optical-light observations (Figure 5) indicate significant differences in microstructure evolution in TTR and TR samples, both in the work-hardened condition and after annealing. A stronger grain refinement in the steel is visible, accompanied by a clear initiation of loss of cohesion in the Ti layers. Figure 6 shows the effects of further deformation, up to a diameter reduction to 0.3 mm, for samples drawn from the work-hardened state at a diameter of 1 mm. A clearly higher degree of fragmentation of the Ti layers can be observed in the TTR samples. It may be assumed that this behavior is primarily influenced by the characteristic stress heterogeneity, exemplified in Figure 3.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the progression of Ti-layer fragmentation in TTR samples drawn from the strain-hardened state at a diameter of 1 mm to a diameter of 0.3 mm.

While the interaction between the two phases is beneficial for mechanical properties, strain partitioning at the interfaces can cause micro-cracking, which deteriorates ductility [35,36,37]. The microscale stress concentration in the cracked region leads to early failure in the bulk scale. Therefore, accurate prediction of the mechanical failure in diverse scales based on a quantitative understanding of the fracture mechanisms is necessary to improve the reliability of heterostructured materials for user safety.

From the experimental results [38], it can be confirmed that the local strain at the onset of microscopic cracking is lower than the local strain at bulk-scale cracking. Furthermore, microscale damage occurs at a lower applied strain than bulk-scale damage. However, if it becomes possible to produce fragmented Ti layers randomly distributed as particles within the steel matrix, an improved mechanical response of such a structural material can be expected. For this reason, in heterogeneous materials reinforced with dispersed particles possessing significantly different mechanical and rheological properties—such as the investigated steel/Ti systems—special attention should be paid to loading conditions and mechanical states, as well as to their proper evaluation, both in terms of mechanical behavior and microstructural features.

One of the more effective methods for experimental assessment of strain partitioning between layers of materials with different rheological properties is the DIC method, particularly the micro-DIC technique used here. With more detailed analysis using high-resolution (HR) DIC combined with in situ SEM observations, it is possible to gain deeper insight into the phenomena occurring in heterogeneous materials. Figure 7 presents representative results of strain distribution analyses on cross-sections of TTR samples after diameter reduction to 1 mm, both in the work-hardened state (Figure 7a–c) and in the annealed state (Figure 7c–e). The analyzed samples were tensile tested using a heating–tensometric stage setup and simultaneously observed by micro-DIC. As a result, strain distributions partitioned between the steel and Ti layers were obtained. The presented distributions of effective strain illustrate its accumulation during tensile deformation at different stages of the test. It can be clearly seen that in the case of specimens tested in the strain-hardened state, strain localization occurs in the Ti layers. Only just before the onset of necking, i.e., upon reaching the maximum tensile stress level, does strain dissipation occur across the entire cross-section of the specimen.

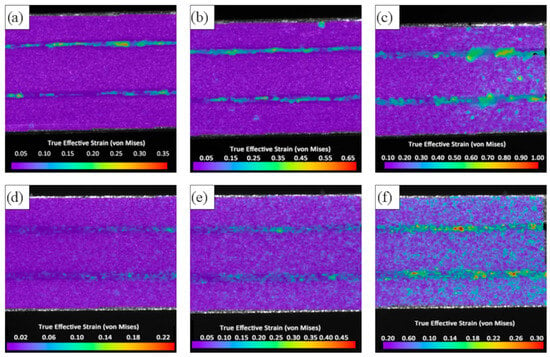

Figure 7.

Results of micro-DIC analysis of longitudinal cross-sections of TTR samples after drawing to a diameter of 1 mm. Distributions of effective strain from the moment the yield stress is exceeded (a,d) to the attainment of the maximum tensile stress (c,f) for samples in the strain-hardened condition (a–c) and the annealed condition (d–f).

In the case of tensile deformation of the annealed TTR specimen, in addition to strain localization in the Ti layers, accommodation of strain by the steel layers is also visible at an earlier stage of deformation. In this case, the steel is more susceptible to deformation than in specimens drawn in the strain-hardened state resulting from prior deformation.

By comparing the results presented in Figure 7, it can be observed that at all stages of tensile deformation, the strains in the Ti layers are distinctly higher in the strain-hardened specimens (Figure 7a–c). This results from the fact that the steel layers, undergoing strain hardening, transfer the load more strongly to the Ti layers due to the increase in plastic flow stress than in the annealed specimens, where the lower yield stress of the annealed steel promotes its deformation and thus a more uniform dissipation of strain across the cross-section.

Additionally, ex situ tensile tests were performed using micro-DIC for wires with a diameter of 0.3 mm. Strain distribution maps for both processing routes (with and without annealing at the initial stage of the process, i.e., at a diameter of 1 mm) and for both specimen types (TTR and TR) are presented in Figure 8. The applied micro-DIC analysis revealed significant strain inhomogeneity during tensile loading for all analyzed configurations, resulting from differences in the rheological properties of the constituent materials.

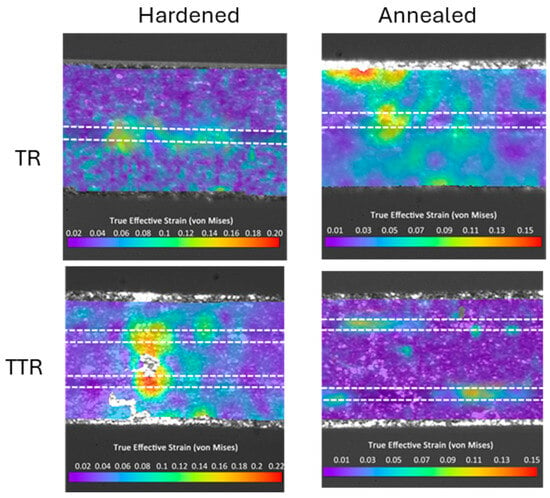

Figure 8.

Micro-DIC strain distribution maps for TR and TTR samples with a diameter of 0.3 mm, drawn from strain-hardened and annealed conditions at an initial diameter of 1 mm, white dashed lines represent the location of titanium layers.

Similar to the tensile deformation of specimens with a diameter of 1 mm, strain localization in the Ti layers was also observed here. For this reason, it can be concluded that the initiation of cohesion loss in the examined systems was clearly triggered by cracking in the hard Ti material. It should also be noted that for specimens drawn to a diameter of 0.3 mm from the strain-hardened state at the initial diameter of 1 mm, strain localization in the Ti layers was more pronounced than in previously annealed specimens. At the same time, a stronger strain concentration in the Ti layers was observed for TTR specimens compared to TR specimens.

When the investigated wires were drawn to a diameter of 0.3 mm from the annealed state, the strain partitioning between the steel and Ti layers was more uniform. One of the reasons for this behavior is the stronger fragmentation of the Ti layers in TTR specimens, which, in the presence of larger hardening gradients in specimens drawn from the strain-hardened state, promotes the localization of plastic deformation in this specific region of the cross-section. It can be expected that this phenomenon will have a direct impact on the mechanical properties of the investigated wires. An important factor in this case is the fact that, unlike in the TR samples, the hard-to-deform Ti layer is located between steel layers, which intensifies the state of tensile stresses and promotes fragmentation (see Figure 3).

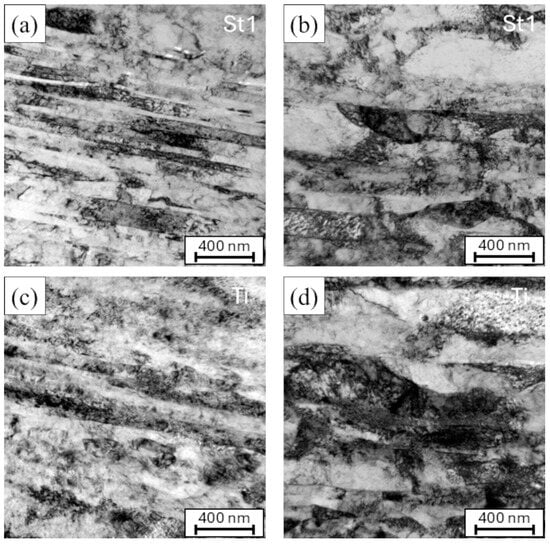

Representative TEM images of the examined samples are shown in Figure 9. The microstructures of the outer steel layer (steel 1) and Ti in the TTR samples after diameter reduction to 0.3 mm are presented. For comparison, microstructures of samples annealed at 1 mm diameter and those drawn to 0.3 mm in the strain-hardened state from previous drawing stages are also shown.

Figure 9.

Bright-field TEM images of steel and Ti layers in a 0.3 mm diameter TTR system. Outer steel 1 layer (a,b); Ti layer (c,d). The wires were hardened (a,c) and annealed (b,d) at a diameter of 1.0 mm.

A comparison of the dislocation structures in steel 1 and Ti reveals distinct differences in grain refinement and dislocation substructure between the hardened and annealed materials. The samples drawn from the hardened state at 1 mm exhibit a refined and strengthened microstructure (Figure 9a,c). The visible refinement of the structure in the steel layer is the result of continuous recrystallization (in situ), which occurred due to the strong accumulation of plastic deformation in the drawn multilayer wires.

Previous studies have proposed various explanations for the simultaneous improvement of strength and ductility, including interaction of dislocations with other dislocations, accumulation of dislocations at the boundaries, interaction of dislocations with precipitates, and the stability of the dislocation cellular structure under large deformation strains [39,40,41,42,43]. In the multilayer system under study, the microalloyed steels (steel 1 and steel 2) exhibit all the aforementioned interactions with dislocations moving during deformation. As a result, these layers experience significant strengthening, which, on one hand, facilitates their own deformation (in accordance with the Considère criterion), and on the other hand, effectively acts as a hard constraint for the Ti layer situated between steel 1 and steel 2. This configuration promotes deformation localization within the Ti layers, as evidenced by the micro-DIC analysis results (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Because of the hcp packing and the c/a ratio being different from the ideal value, the plastic deformation of Ti is accommodated by a combination of slip and twinning at room temperature. This gives rise to more complex mechanical responses than those of bcc or fcc structures [44,45].

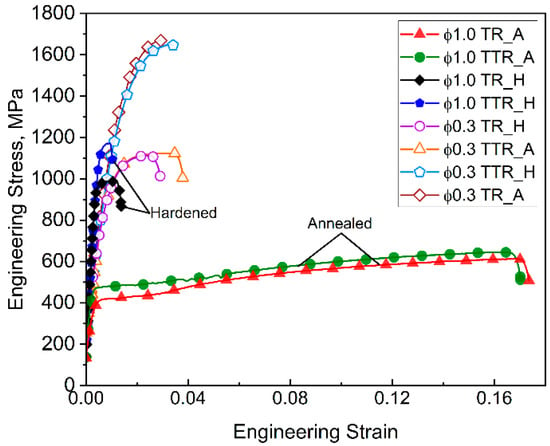

The representation of the mechanical response of the investigated multilayer systems is shown in Figure 10. The results of tensile tests of the TTR and TR systems after drawing to final diameters of 1 mm and 0.3 mm are compiled there. For the diameter of 1 mm, the curves represent the strain-hardened states (ϕ1.0 TR_H, TTR_H) and the annealed states (ϕ1.0 TR_A, TTR_A), whereas for the diameter of 0.3 mm, they correspond to strain-hardened states obtained by drawing from 1 mm diameter wires that were either strain-hardened (ϕ0.3 TR_H, TTR_H) or annealed (ϕ0.3 TR_A, TTR_A).

Figure 10.

Results of tensile tests of the investigated multilayer systems.

The presented results demonstrate a large variation in the mechanical properties of the multilayer systems investigated. As expected, the samples with a diameter of 1.0 mm subjected to prior annealing exhibit the highest plasticity and simultaneously the lowest strength. The same samples in the strain-hardened condition show higher strength properties, but lower than those of the samples with a diameter of 0.3 mm. The premature failure of those samples was caused by interfacial debonding. In these specimens, the titanium layer retained a substantial thickness (exceeding 50 μm and 100 μm in the TTR and TR samples, respectively). The largest differences in the tensile curves can be observed for the 0.3 mm samples, where the TR_A systems exhibit properties similar to those of TTR_H. In contrast, the TR_H samples show strength properties comparable to those of TTR_A, but with lower elongation.

The presented results clearly demonstrate how complex the analysis of mechanical properties is in multilayer systems composed of materials with such different rheological properties as steel and titanium. It may be assumed that the primary factors influencing the highly diversified mechanical responses are the different characteristics and strengthening mechanisms present in both investigated materials, i.e., microalloyed steel and titanium. The different evolution of the microstructure during multistage drawing of multilayer wires constitutes an additional contributing factor in this case.

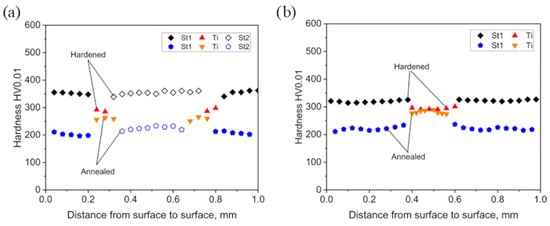

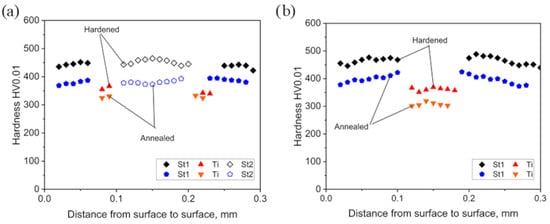

A representation of the strength properties of the examined heterogeneous systems is provided by HV 0.01 microhardness measurements, with a dwell time of 10 s. Figure 11 and Figure 12 show exemplary hardness distributions across the cross-sections of the investigated specimens. The presented hardness measurement results illustrate the influence of various strengthening mechanisms that played a significant role in shaping the mechanical properties of the investigated multilayer systems. Of particular importance appears to be the development of strengthening mechanisms during the drawing process—especially the effects of strain hardening and the associated refinement of the steel microstructure. For comparison, hardness profiles for TTR and TR samples are presented, all subjected to an identical deformation history. The hardness distributions illustrate the strengthening states of wires drawn to diameters of 1.0 mm (Figure 11) and 0.3 mm (Figure 12). The comparison of hardness distributions in individual layers allows for an assessment of changes in strengthening processes during the final stages of drawing in multilayer systems. The presented hardness measurement results also enable an evaluation of the rate of strain hardening in individual layers in both previously strain-hardened and annealed states.

Figure 11.

Hardness distributions across the cross-sections of drawn wires with a final diameter of 1.0 mm: TTR (a); TR (b).

Figure 12.

Hardness distributions across the cross-sections of wires drawn from 1 mm diameter stock, initially in annealed or hardened conditions, to a final diameter of 0.3 mm: TTR (a); TR (b).

For wires with a diameter of 1.0 mm, the final annealing was applied after drawing from a diameter of 2.18 mm, whereas for wires with a diameter of 0.3 mm, annealing was performed at a diameter of 1.0 mm. The strain-hardened state in wires with a diameter of 0.3 mm was obtained through multistage deformation from 2.18 mm. In the case of TTR wires with a diameter of 0.3 mm (Figure 12), the measured hardness values result from intensive fragmentation in the Ti layers (Figure 6). These wires generally exhibit higher strength, while the difference in hardness between the annealed state (at 1.0 mm), and the strain-hardened state is clearly smaller than in wires with a diameter of 1.0 mm. This effect, not observed in the Ti layers, indicates both strain hardening and the stabilization of strengthening mechanisms, largely associated with an intensive refinement of the steel microstructure in which in situ recrystallization occurred, induced by a strong accumulation of deformation. Fragmentation of the Ti layers further enhances this effect. The hardness distributions in wires with a diameter of 0.3 mm also show greater heterogeneity, probably resulting from deformation of a refined, stable microstructure enriched in high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs). Such a structure is no longer susceptible to in situ recrystallization and therefore reflects the inherent heterogeneity typical of drawn wires.

4. Summary and Conclusions

Multilayer systems composed of microalloyed steel and titanium were investigated. The results show that, in addition to conventional strengthening mechanisms, microstructural evolution plays a crucial role, particularly grain refinement via continuous recrystallization and strain hardening. Strengthening may be further intensified by pile-up mechanisms associated with dislocation substructures and fragmentation of the hard Ti phase near the more ductile steel layers.

The study demonstrates that achieving a heterogeneous structure with synergistic strengthening requires TTR-type samples subjected to large diameter reductions with minimal intermediate annealing, enabling severe plastic deformation and characteristic microstructural refinement. In contrast to TR samples, placing the hard-to-deform Ti layer between steel layers intensifies tensile stresses and promotes fragmentation. We believe that, based on the behavior of the titanium layer observed in the present study, the subsequent large deformation will result in the production of materials with particles of various sizes.

Microstructural characterization and micro-DIC analysis revealed strong strain localization in the Ti layers of heavily deformed specimens, with strain heterogeneity increasing in the strain-hardened condition. Rheological modeling successfully reproduced the observed deformation heterogeneity and strengthening mechanisms. Tensile testing and microhardness measurements confirmed that constructing heterogeneous systems from materials as dissimilar as microalloyed steel and titanium requires careful control of processing, microstructural evolution, and strengthening mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; methodology, B.P. and M.K.; software, P.L.-G.; validation, M.K., B.P. and P.L.-G.; formal analysis, B.P.; investigation, B.P., M.K. and P.L.-G.; resources, M.K. and J.M.; data curation, P.L.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, B.P. and J.M.; visualization, B.P. and P.L.-G.; supervision, J.M.; project administration, J.M.; funding acquisition, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Center, Poland, project 2022/45/B/ST8/01383.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged the National Science Center, Poland for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, R.; Li, X.; Gao, H. Towards Understanding the Structure–Property Relationships of Heterogeneous-Structured Materials. Scr. Mater. 2020, 186, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Zhou, R.; Vivegananthan, P.; See Wu, M.; Gao, H.; Zhou, K. Recent Progress in Gradient-Structured Metals and Alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 140, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, K.; Sato, H.; Arika, M.; Takahashi, R. Development of NbTi Superconducting Strands and Cables for the Field Winding of a 200-MW-class High-energy-density Superconducting Generator. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2006, 156, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kientzl, I.; Orbulov, I.N.; Dobránszky, J.; Németh, Á. Mechanical Behaviour Al-Matrix Composite Wires in Double Composite Structures. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2006, 50, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Yang, X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, L. Texture Evolution and Nanohardness in Cu-Nb Composite Wires. Materials 2021, 14, 5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zheng, W.; Hu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, D. Heterostructured Metal Matrix Composites for Structural Applications: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 9768–9801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, S.; Cao, J.; Merklein, M.; Yanagimoto, J. Forming of Metal-Based Composite Parts. CIRP Ann. 2021, 70, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, D.; Rong, X.; He, C.; Zhao, N. Breaking the Strength-Ductility Trade-off for Metal Matrix Composites: A Review of the Role of Nanoscale Reinforcement Dimension on the Deformation and Strengthening Mechanisms. Rev. Mater. Res. 2025, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Hao, M.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Rao, G.; Zhang, L.; Ding, C.; Zhou, K.; Liu, L.; et al. Heterostructures Enhance Simultaneously Strength and Ductility of a Commercial Titanium Alloy. Acta Mater. 2023, 257, 119182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzbeh, A.; Sedighi, M.; Hashemi, R. Comparison between Explosive Welding and Roll-Bonding Processes of AA1050/Mg AZ31B Bilayer Composite Sheets Considering Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 6322–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocich, R.; Kunčická, L.; Macháčková, A.; Šofer, M. Improvement of Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Rotary Swaged Al-Cu Clad Composites. Mater. Des. 2017, 123, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Castelnau, O.; Forest, S.; Hervé-Luanco, E.; Lecouturier, F.; Proudhon, H.; Thilly, L. Multiscale Modeling of the Elastic Behavior of Architectured and Nanostructured Cu–Nb Composite Wires. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2017, 121, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rdzawski, Z.; Stobrawa, J.; Głuchowski, W.; Sobota, J. Mechanism and Kinetics of Precipitation Process in Selected Copper Alloys. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2014, 59, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hansen, N.; Godfrey, A.; Huang, X. Dislocation-Based Plasticity and Strengthening Mechanisms in Sub-20 Nm Lamellar Structures in Pearlitic Steel Wire. Acta Mater. 2016, 114, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Fan, G. An Overview of Tailoring Strain Delocalization for Strength-Ductility Synergy. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 113, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; You, Z.S.; Tao, N.R.; Jin, Z.H.; Lu, L. Mechanically-Induced Grain Coarsening in Gradient Nano-Grained Copper. Acta Mater. 2017, 125, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Huang, C.X.; Fang, X.T.; Höppel, H.W.; Göken, M.; Zhu, Y.T. Hetero-Deformation Induced (HDI) Hardening Does Not Increase Linearly with Strain Gradient. Scr. Mater. 2020, 174, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.X.; Wang, Y.F.; Ma, X.L.; Yin, S.; Höppel, H.W.; Göken, M.; Wu, X.L.; Gao, H.J.; Zhu, Y.T. Interface Affected Zone for Optimal Strength and Ductility in Heterogeneous Laminate. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embury, D.; Bouaziz, O. Steel-Based Composites: Driving Forces and Classifications. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2010, 40, 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, Y. Heterogeneous Materials: A New Class of Materials with Unprecedented Mechanical Properties. Mater. Res. Lett. 2017, 5, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, A.H.; Embury David Embury, D. How to Replace Stainless Steel with Foam. Presented at CASA Centre for Advanced Structural Analysis. Available online: https://sfi-casa.no/how-to-replace-stainless-steel-with-foam-david-embury/ (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Raabe, D.; Sachtleber, M.; Zhao, Z.; Roters, F.; Zaefferer, S. Micromechanical and Macromechanical Effects in Grain Scale Polycrystal Plasticity Experimentation and Simulation. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 3433–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabich, B.; Majta, J.; Kwiecień, M.; Cichocki, K.; Błoniarz, R. Microstructure and Mechanical Response of Steel/Ti Composites Processed by Severe Wire Drawing. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2025, 56, 5740–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabich, B.; Żurowski, B.; Kwiecień, M.; Majta, J. Evaluation of Deformation Inhomogeneity in Multi-Layered Steel-Titanium and Steel-Magnesium Systems. Comput. Methods Mater. Sci. 2025, 25, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. A Constitutive Model and Data for Metals Subjected to Large Strains, High Strain Rates and High Temperatures. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Balistics, Hague, The Netherlands, 19–21 April 1983; American Defense Preparedness Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 1983; p. 541. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.S.; Suh, Y.S.; Chen, X.; Takacs, L.; Zhang, H. Nanocrystalline Aluminum and Iron: Mechanical Behavior at Quasi-Static and High Strain Rates, and Constitutive Modeling. Int. J. Plast. 2006, 22, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Huang, S. Experimental and Theoretical Study of Mechanical Behavior of 1100 Aluminum in the Strain Rate Range 10−5–104s−1. Int. J. Plast. 1992, 8, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszka, K.; Hodgson, P.D.; Majta, J. A Physical Based Modeling Approach for the Dynamic Behavior of Ultrafine Grained Structures. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2006, 177, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şchiopu, V.; Luca, D. A New Net-Shape Plating Technology for Axisymmetric Metallic Parts Using Rotary Swaging. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 85, 2471–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Tieu, A.K.; Lu, C.; Liu, X.; Godbole, A.; Li, H.; Kong, C.; Qin, Q. A Deformation Mechanism of Hard Metal Surrounded by Soft Metal during Roll Forming. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilly, L.; Colin, J.; Lecouturier, F.; Peyrade, J.P.; Grilhé, J.; Askénazy, S. Interface Instability in the Drawing Process of Copper/Tantalum Conductors. Acta Mater. 1999, 47, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, Y. Gradient and Lamellar Heterostructures for Superior Mechanical Properties. MRS Bull. 2021, 46, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, A.; Danesh Manesh, H.; Janghorban, K. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties and Structure of Multilayered Al/Ni Composites Produced by Accumulative Roll Bonding (ARB) Process. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 489, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, X. Heterostructured Materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 131, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Kang, Y.; Hodgson, P.D.; Stanford, N. Quantitative Measurement of Strain Partitioning and Slip Systems in a Dual-Phase Steel. Scr. Mater. 2013, 69, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadbeigi, H.; Pinna, C.; Celotto, S.; Yates, J.R. Local Plastic Strain Evolution in a High Strength Dual-Phase Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 5026–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Jonnalagadda, K.N. An In-Situ Investigation of the Strain Partitioning and Failure Across the Layers in a Multi-Layered Steel. Exp. Mech. 2024, 64, 703–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.H.; Kwon, J.; Moon, J.; Kwon, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, E.S.; Seo, M.H.; Hwang, H.; Kim, H.S. Determination of Damage Model Parameters Using Nano- and Bulk-Scale Digital Image Correlation and the Finite Element Method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkia, B.; Aubry, P.; Haghi-Ashtiani, P.; Auger, T.; Gosmain, L.; Schuster, F.; Maskrot, H. On the Origin of the High Tensile Strength and Ductility of Additively Manufactured 316L Stainless Steel: Multiscale Investigation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 41, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.S.; Dovgyy, B.; Hooper, P.A. Twinning Induced Plasticity in Austenitic Stainless Steel 316L Made by Additive Manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 704, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, B.; Guo, Q. Strengthening and Hardening Mechanisms of Additively Manufactured Stainless Steels: The Role of Cell Sizes. Scr. Mater. 2020, 177, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, K.M.; Meric de Bellefon, G.; Kuehl, B.; Thoma, D.J. Origin of Dislocation Structures in an Additively Manufactured Austenitic Stainless Steel 316L. Acta Mater. 2020, 199, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, T.; Forien, J.-B.; Perron, A.; Aubry, S.; Bertin, N.; Samanta, A.; Baker, A.; Wang, Y.M. New Insights on Cellular Structures Strengthening Mechanisms and Thermal Stability of an Austenitic Stainless Steel Fabricated by Laser Powder-Bed-Fusion. Acta Mater. 2021, 203, 116476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Wang, Q.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Sang, B.; Li, L. Plastic Deformation Mechanism and Slip Transmission Behavior of Commercially Pure Ti during In Situ Tensile Deformation. Metals 2022, 12, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, M.; Hama, T.; Knudsen, E.; Korkolis, Y.P. Plastic Deformation of Commercially-Pure Titanium: Experiments and Modeling. Int. J. Plast. 2018, 105, 164–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.