Abstract

To address the demands of modern high-speed and high-quality continuous casting production, depositing high-performance coatings on the surface of mold copper plates is critically important for extending the service life of continuous casting molds. To this end, a Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating was developed, and cryogenic treatment was applied to further improve its hardness and wear resistance. This work systematically investigates the microstructural evolution and performance enhancement of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating under different cryogenic treatment parameters, with special emphasis on the effects of treatment temperature on the coating’s microstructure, hardness, wear resistance, and adhesion to the substrate. The results demonstrate that decreasing the cryogenic treatment temperature and extending the holding time effectively refine the grains of the coating while simultaneously promoting the accumulation of microstrain and dislocation density. These changes lead to significant improvements in hardness, wear resistance, and interfacial bonding performance. Specifically, after direct immersion at −196 °C for 16 h, the coating reached a hardness value of 946.5 HV, and the wear rate was reduced to 0.032 mm3·(N·m)−1, representing only 54.6% of that of the untreated coating. The dominant wear mechanism transitioned to a mixed mode of abrasive wear and oxidative wear. Moreover, the cryogenic treatment enhanced the stability of the coating-substrate adhesion.

1. Introduction

The continuous casting mold is one of the core components of the continuous casting machine. Applying high-performance coatings on the surface of its copper plates not only helps extend the service life of the mold and reduce production costs but also effectively improves the quality of cast billets. Since the 1970s, coating systems have evolved from single-component to binary composite coatings, significantly addressing issues such as low bonding strength, insufficient hardness, and poor wear resistance in early coatings. Among various binary coatings, Ni-Co coatings have been widely adopted due to their advantages, including relatively high hardness, low friction coefficient [,], and a well-matched thermal expansion coefficient with copper substrates [,,]. However, with the ongoing advancement of modern continuous casting technology toward high-speed and high-quality production, Ni-Co coatings still face challenges such as high cost and insufficient hardness and wear resistance [,]. To further enhance the overall performance of coatings, a novel multi-component alloy coating system—the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating—has been proposed. By incorporating Cr elements and SiC nanoparticles, this system effectively improves the shortcomings of Ni-Co binary coatings in terms of hardness and wear resistance while maintaining excellent bonding performance with the substrate. Despite these improvements, further advances in wear performance of Ni–Co–Cr/SiC coatings are essential to align with the stringent requirements of modern high-speed casting and to sustain industrial competitiveness.

Cryogenic treatment, as a specialized heat treatment technique, enhances mechanical properties of materials by modulating alloy microstructure in ultra-low temperature environments. Initially applied primarily to ferrous materials, studies have confirmed that cryogenic treatment improves material performance through mechanisms including retained austenite conversion to martensite, grain refinement, and precipitation strengthening. For instance, studies by Patricia Jovičević-Klug et al. [] demonstrated that the enhanced wear resistance of high-speed steel after cryogenic treatment primarily results from microstructural homogenization and carbide refinement, leading to superior mechanical properties. Significant improvements in wear resistance and overall mechanical performance have also been observed in 36CrB4 alloy [], AISI D6 steel [], and high-speed steels []. The application of cryogenic treatment has now expanded to include non-ferrous systems, hard alloys, and functional coatings. In the field of non-ferrous metals, cryogenic treatment significantly enhances material properties: it improves the hardness and corrosion resistance of 7075 aluminum alloy by optimizing grain boundary precipitate distribution []; promotes grain refinement in CuBe2 alloy, leading to notable increases in strength and hardness []; induces refined distribution of Ω precipitates in Al-Cu-Mg-Ag alloy []; and numerous studies confirm its effectiveness in enhancing the strength and hardness of various copper alloys [] and aluminum alloys []. In hard alloys, cryogenic treatment promotes WC grain refinement in WC-Co systems and induces phase transformation of Co from α-Co (FCC) to ε-Co (HCP), thereby significantly improving material hardness [,,] and toughness [,].

While investigations into cryogenic treatment for continuous casting mold coatings remain relatively scarce, available evidence confirms its efficacy in enhancing the hardness and wear performance of cemented carbides and metallic coating systems. Progress has also been made in cryogenic treatment of hard alloy coatings. After treatment at −140 °C, the diamond-like carbon coating on M35 high-speed steel shows reduced surface roughness and improved adhesion, with wear resistance further enhanced following 6 h treatment at −190 °C []. TiAlN coating reaches peak performance after 36 h cryogenic treatment, with hardness and adhesion strength increasing to 3611.1 HV and 69.70 N, respectively, though excessive treatment duration leads to performance degradation []. Christian I. Chiadikobi et al. [] demonstrated that cryogenic processing significantly enhances the hardness and stiffness of AISI M2 high-speed steel with a PVD-TiN coating. Building upon the demonstrated strengthening effects of cryogenic treatment across multiple alloy systems, this study introduces this technique to Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coatings for continuous casting molds. The research aims to enhance the coating’s hardness and wear resistance through microstructural modification, thereby extending the service life of the casting mold.

In summary, while existing studies on cryogenic treatment applied to coating-substrate composites remain limited, evidence from literature confirms this technique facilitates microstructural evolution, residual stress redistribution, secondary phase formation, and grain refinement in metallic systems. These microstructural changes are often accompanied by strengthening effects such as grain refinement strengthening and precipitation strengthening. Notably, the underlying enhancement mechanisms vary significantly across different metallic materials after cryogenic treatment. Currently, the cryogenic treatment of Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coatings for continuous casting molds remains completely unexplored in scientific literature, while systematic investigations into its effects on interfacial adhesion between mold copper substrates and coatings are notably lacking. Therefore, this study proposes that cryogenic treatment holds great potential for significantly enhancing the hardness, wear resistance, and related mechanical characteristics of Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coatings applied in continuous casting molds.

Focusing on key cryogenic parameters—treatment temperature, dwell time, and cooling rate—this research precisely evaluates their individual effects on the microhardness of Ni–Co–Cr/SiC nanocomposite coatings using a one-factor-at-a-time methodology. Through comparative analysis, the optimal cryogenic treatment temperature and cooling rate parameters were first determined, with subsequent focus on examining the influence of different holding durations (0–48 h) on coating microstructure evolution, hardness, and wear resistance. The findings provide new theoretical insights and technical pathways for enhancing the comprehensive mechanical properties of continuous casting mold coatings.

2. Preparation and Cryogenic Treatment of the Coating Material

2.1. Coating Preparation

This study investigates a Ni–Co–Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating with a nominal composition of 73.0 wt% Ni, 22.5 wt% Co, 3.7 wt% Cr, and 0.8 wt% SiC. The coating was fabricated via electrodeposition onto a chromium–zirconium copper substrate measuring 25 mm × 25 mm × 2.5 mm, achieving a uniform thickness of approximately 45–55 μm. The electrolyte was formulated using chromium sulfate, cobalt sulfate, and nickel sulfate as metal sources, with nano-sized silicon carbide (SiC) particles acting as the reinforcement phase. To facilitate the co-deposition of metallic ions and nanoparticles, sodium formate (anhydrous) and urea were added as complexing agents []. The specific electrolyte formulation and processing conditions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Electroplating solution composition and electrodeposition process parameters.

Simultaneously, the inherent tendency of nanoparticles to agglomerate—due to their high specific surface energy and ultrafine dimensions—poses a significant challenge. Such agglomeration hinders uniform distribution within the coating, thereby compromising the dispersion strengthening effect and potentially inducing stress concentration and microcrack initiation, which collectively deteriorate coating performance. To mitigate nanoparticle agglomeration and enhance dispersion homogeneity, the electrolyte was subjected to 16 h of ultrasonic pretreatment prior to electrodeposition, employing a pulsed mode comprising 4 s ultrasonication followed by 4 s intervals. Moreover, ultrasonic agitation was maintained throughout the deposition process to ensure consistent and uniform nanoparticle distribution.

2.2. Cryogenic Treatment Scheme

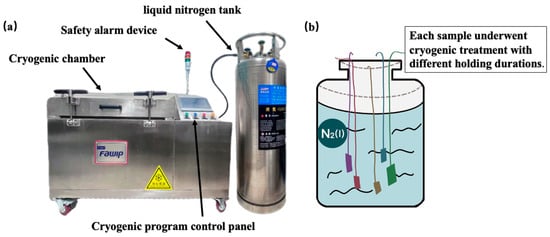

A program-controlled cryogenic treatment system (Model: SLX-30) was employed to precisely regulate the cryogenic temperature and cooling rate. Figure 1a illustrates the experimental setup of the program-controlled cryogenic treatment system. The general procedure involves placing the samples in the cryogenic chamber and controlling the flow of liquid nitrogen from the tank into the chamber through the program control panel, thereby achieving accurate control of both the cryogenic treatment temperature and cooling rate. The investigation of holding duration was conducted using a direct immersion method, with the detailed experimental apparatus illustrated in Figure 1b, where samples were directly placed in a liquid nitrogen-filled tank for different treatment durations.

Figure 1.

Cryogenic treatment setup: (a) SLX-30 program-controlled cryogenic chamber; (b) direct immersion method.

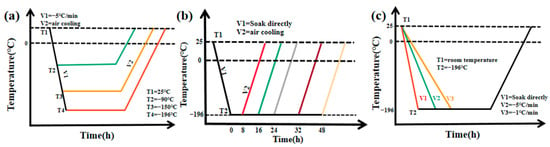

During the preliminary stage of this study, a comprehensive analysis was performed to examine how key cryogenic processing variables—namely, treatment temperature (−90 °C, −150 °C, and −196 °C) [,,], cooling rate (−1 °C·min−1, −5 °C·min−1, and direct liquid nitrogen immersion) [,,], and soaking time (8–40 h) [,,,]—influence the microhardness of Ni–Co–Cr/SiC nanocomposite coatings. The experimental workflow is illustrated in Figure 2. The results revealed that soaking time demonstrated the dominant effect on coating microstructure and mechanical characteristics among the tested parameters, consistent with earlier reports on comparable materials. Based on these findings, the current investigation utilized direct liquid nitrogen immersion (−196 °C) with systematically controlled soaking periods from 8 to 40 h, succeeded by spontaneous tempering to room temperature, to thoroughly examine how dwelling time affects the coatings’ microstructure, surface characteristics, hardness, and tribological performance. The optimal cryogenic holding parameters were ultimately determined through comparative analysis with as-deposited coatings.

Figure 2.

Experimental flowchart: (a) Cryogenic treatment temperature; (b) Holding duration; (c) Cooling rate.

2.3. Microstructural Characterization and Performance Testing Methods

2.3.1. Coating Phase Characterization

The coating composition and microstructure were characterized using electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction techniques. Following cryogenic treatment, samples were alcohol-cleaned prior to examination with a JEOL JSM-6510F field emission SEM (NEC Electronics Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for morphological analysis. Elemental composition was determined by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (NEC Electronics Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) employing an 80 mm2 X-MaxN silicon drift detector. Phase identification was conducted using a multifunctional high-resolution X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical B.V., Almelo, Netherlands) with copper target, operating at scanning parameters of 30 min duration across a 2θ range of 30–120°. Based on the diffraction patterns, average grain size, microstrain, and dislocation density were derived.

The Scherrer formula (Equation (1) [,]) was further used to calculate the average grain size (β) of the coatings under different cryogenic treatment durations.

In the equation, β is the diffraction peak’s full width at half maximum (FWHM, rad), K is a constant valued at 0.89, λ corresponds to the Cu Kα radiation wavelength (0.154056 nm), L represents the crystallite size perpendicular to the reflecting plane (nm), and θ denotes the Bragg angle (rad).

Furthermore, the stresses generated during the cryogenic treatment induce minor plastic deformation within the coating, leading to changes in microstructural characteristics including grain boundaries and dislocation arrangements. The alloy’s microstrain and dislocation density were determined from Equations (2) [] and (3) [], respectively.

In the formula, b represents the Burgers vector with a value of 0.249.

2.3.2. Materials Performance Testing Methods

This study employed Vickers hardness testing, friction and wear experiments, and micro-scratch testing to evaluate the coating hardness, wear resistance, and bonding performance with the substrate. Vickers hardness measurements were performed under 200 gf loading with 10 s dwell time using an HX-1000 instrument (MEGE INSTRUMENTS, Suzhou, China). Each sample underwent nine hardness measurements. To ensure data accuracy, the reported result was taken as the mean after eliminating the most extreme values at both ends of the data range.

Friction and wear performance were assessed using a UMT-2 tribometer (Bruker, MA, USA) in linear reciprocating mode with a spherical alumina counter body. Testing proceeded under these conditions: 15 N load, 30 min duration, 10 mm·s−1 speed, and 5 mm stroke. Wear scar topography was recorded by a Micro XAM non-contact optical profiler (KLA-Tencor, Milpitas, CA, USA) along 1 mm paths, with material loss subsequently determined. The wear rate is calculated from Equation (4) []:

where K designates the wear rate (mm3·(N·m)−1), V indicates wear volume (μm3), F corresponds to applied load (N), and signifies sliding distance (mm).

The adhesion performance was evaluated using a micro-scratch tester (CSM MST, Swiss CSM Instrument Co., Ltd., Zug, Switzerland). A spherical diamond indenter with a 100 μm tip radius was used to create 3 mm scratches under a linearly ramped load (0–20 N) at 5 mm·min−1. The critical penetration load was measured to evaluate the coating-substrate adhesion strength.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hardness

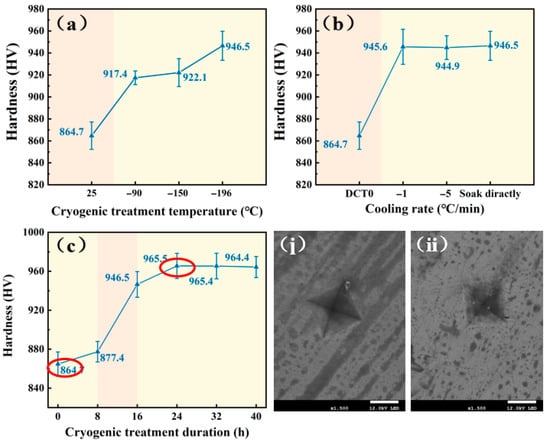

Figure 3 shows the hardness response of the Ni–Co–Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating to cryogenic treatment. All hardness measurements were taken on the coating surface. The data reveal a consistent improvement in coating hardness under different cryogenic treatment conditions. Specifically, as shown in Figure 3a, the hardness of the coating increased progressively as the cryogenic treatment temperature decreased. When the temperature was reduced to –90 °C, the hardness was already significantly higher than that of the untreated coating; when further lowered to –150 °C, the rate of hardness increase slowed; and when cooled to –196 °C, the hardness rose markedly to 946.5 HV, representing a 9.5% improvement over the original state.

Figure 3.

Effect of different cryogenic treatment parameters on coating hardness: (a) temperature; (b) cooling rate; (c) holding duration; (i) coating hardness indentation before cryogenic treatment; (ii) indentation hardness after direct immersion for 24 h.

In contrast, Figure 3b indicates that different cooling rates had almost no noticeable effect on hardness improvement. Meanwhile, as seen in Figure 3c, the holding time had a very significant influence on hardness. Within the 24 h treatment period, hardness continued to increase with prolonged holding time, reaching a maximum of 965.5 HV (an 11.7% improvement), after which it stabilized. It is worth noting that all cryogenically treated coatings exhibited better hardness performance than the untreated state. The specific indentation morphology of the obvious points circled in Figure 3c is shown in figures (i) (untreated) and (ii) (after 24 h of cold treatment).

The results demonstrate that, among the three process parameters, holding time has the dominant influence on coating performance, far exceeding the effects of treatment temperature and cooling rate. Therefore, the subsequent part of this paper will focus on investigating the influence of cryogenic holding time on the coating’s microstructure and mechanical properties.

3.2. Microstructure

3.2.1. XRD Characterization of Coating Structure

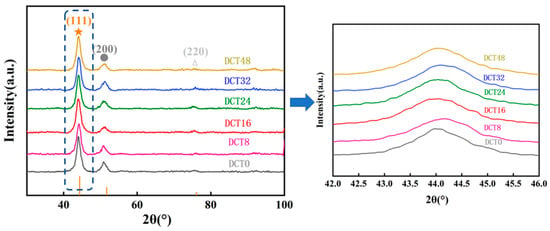

Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating after cryogenic treatment with different holding durations (where DCT0 represents the non-cryogenically treated reference sample, and DCTX denotes the experimental group subjected to X hours of cryogenic treatment). The results indicate that the phase structure of the coating remained a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure both before and after cryogenic treatment. The diffraction profiles maintained consistent shapes across extended holding durations, consistently matching pure nickel reference patterns (PDF#89-7128) with the exclusive presence of characteristic peaks. These results confirm the structural integrity of the single-phase FCC coating was preserved during cryogenic processing.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating under different cryogenic treatment durations.

Furthermore, the intensity of the diffraction peaks changed with varying cryogenic holding times. Figure 4 shows the XRD pattern of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC coating, displaying two dominant reflections corresponding to the (111) and (200) planes. With increasing holding time, both the intensity and width of these diffraction peaks changed. Magnifying the main peaks (111) revealed that the intensity and width of these diffraction peaks changed with increasing holding time. Notably, the (111) peak showed significant broadening, indicating possible grain refinement within the coating. When the cryogenic holding time reached 16 h, the intensity of the (200) peak noticeably decreased, suggesting textural evolution in the coating’s crystalline alignment.

The changes in diffraction peak intensity are attributed to the preferential rotation of grains toward certain crystallographic planes. Grain rotation commonly occurs in magnesium and similar alloys during cryogenic exposure, attributed to thermally induced lattice contraction stresses []. The broadening of the characteristic peaks after cryogenic treatment implies that the process promotes grain refinement in the coating.

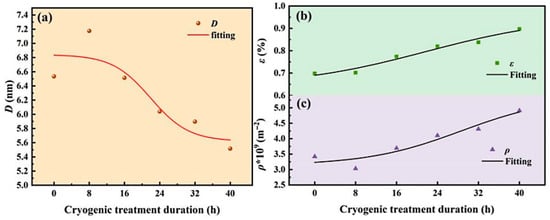

Figure 5 presents coating characteristics derived from XRD analysis: average grain size, microstrain, and dislocation density.

Figure 5.

Microstructural evolution under varied cryogenic durations: (a) average grain size; (b) microstrain; (c) dislocation density.

Following cryogenic exposure, the coating’s grain size, microstrain, and dislocation density were substantially affected. Following 40 h of cryogenic processing, the mean grain size reduced from 6.53 nm to 5.51 nm, while microstrain and dislocation density concurrently rose with progressively extended treatment duration.

The variation in microstrain reflects the degree of internal deformation in the material, primarily originating from stress-induced lattice contraction during cryogenic treatment [] and the continuous accumulation of dislocation density. When the coating undergoes rapid cooling from room temperature (~300 K) to liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K), its constituent phases (the Ni-Co-Cr alloy matrix and the SiC ceramic reinforcement phase) experience varying degrees of volumetric contraction due to differences in their coefficients of thermal expansion. This mismatch in contraction generates significant microscopic internal stresses at the interfacial regions. During the subsequent warming back to room temperature, these internal stresses cannot be fully released, leading to lattice distortion in the metal matrix and resulting in the accumulation of microstrain and dislocation density. Consequently, this process not only promotes grain refinement in the coating but also effectively induces lattice contraction and enhances dislocation density, thereby potentially improving its mechanical properties [].

3.2.2. Effect of Cryogenic Holding Time on Microstructure

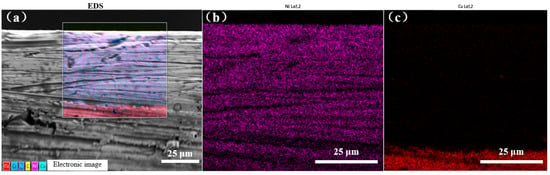

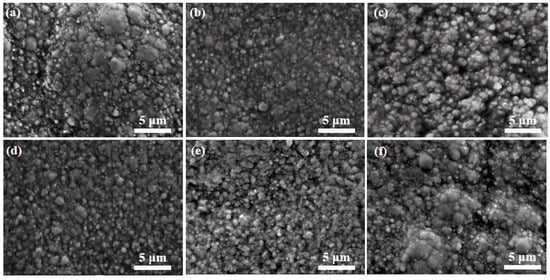

Figure 6 presents the cross-sectional EDS analysis of the coating prior to cryogenic treatment. As shown in Subfigure (a), a distinct bonding interface is observed between the coating and the substrate. The EDS mapping results (Figure 6b,c) demonstrate the absence of the copper element from the substrate above this interface. This complete nickel coverage is likely attributed to the uniform deposition of nickel on all surfaces during the electroplating process. Based on the cross-sectional images and EDS measurements, the coating thickness is determined to be maintained within the range of 45–55 μm. Figure 7 illustrates the surface morphological evolution of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating in both the untreated state and after different cryogenic holding durations (DCT8-DCT40). The results clearly show that no cracking or delamination occurred on the coating surfaces following cryogenic treatment.

Figure 6.

EDS results of the sample cross-section before cryogenic treatment: (a) test range; (b) Nickel element distribution; (c) Copper element distribution.

Figure 7.

Surface morphology of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating after different cryogenic holding durations: (a) DCT0; (b) DCT8; (c) DCT16; (d) DCT24; (e) DCT32; (f) DCT40.

As observed in Figure 7a, the silicon carbide (SiC) particles in the untreated coating appear relatively dispersed with irregular morphology and exhibit significant agglomeration, resulting in a porous microstructure and poor densification. After 8 h of cryogenic treatment (Figure 7b), the particle distribution becomes more uniform with initial refinement of larger particles. When the holding time was extended to 40 h (Figure 7c–f), further improvement in particle homogeneity was observed along with a gradual decrease in average particle size. The refinement of SiC particles contributes to a denser coating structure characterized by significantly reduced interparticle spacing and markedly enhanced compactness.

These findings demonstrate that appropriate cryogenic holding durations can effectively promote uniform particle distribution and grain refinement while maintaining the structural integrity of the coating. The cryogenic treatment ultimately enhances the overall coating performance through optimized reinforcement phase distribution and microstructural refinement.

3.3. Wear Resistance Testing of Coatings

3.3.1. Coefficient of Friction

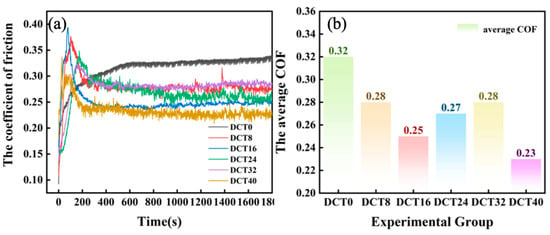

The coefficient of friction (COF) is one of the key parameters for evaluating the wear resistance of materials, and its magnitude is generally influenced by hardness and surface characteristics. In this study, a reciprocating tribometer was used to evaluate the wear resistance of the coating before and after cryogenic treatment. Figure 8a shows the variation in the COF over time for the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating under different cryogenic holding durations (0 h, 8 h, 16 h, 24 h, 32 h and 40 h).

Figure 8.

Effect of different cryogenic holding durations on the coefficient of friction of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating: (a) the coefficient of friction; (b) the average COF.

As observed, the change in COF undergoes two distinct stages: an initial running-in stage and a stable friction stage. During the running-in stage, after the Al2O3 ball contacts the coating surface, the COF increases rapidly and then gradually slows in its rate of increase. As the friction contact angle and surface roughness change, the particles on the coating surface are gradually flattened, and the contact surface becomes smoother, eventually entering the stable stage. In this stage, the fluctuation of the COF decreases, though surface cracks and wear debris may form.

The results indicate that when the cryogenic holding duration is short (8 h), the average COF of the coating shows an increasing trend. However, as the cryogenic holding duration further increases, the rate of COF increase during the initial stage slows significantly, and the COF remains at a relatively low level throughout the stable stage. This suggests that the wear resistance of the coating is enhanced.

Figure 8b illustrates the variation in the average coefficient of friction (COF) of the coating under different cryogenic holding durations. The results indicate that, compared to the pre-cryogenic condition, the average COF generally decreases after cryogenic treatment, suggesting an improvement in wear resistance. Notably, after 16 h of cryogenic treatment, the average COF reaches a value of 0.25. However, as the holding duration further increases, the average COF shows a tendency to rise. It should be noted that the magnitude of the COF can be influenced by surface flatness. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of wear resistance should also incorporate wear rate measurements for a more accurate assessment.

3.3.2. Wear Resistance

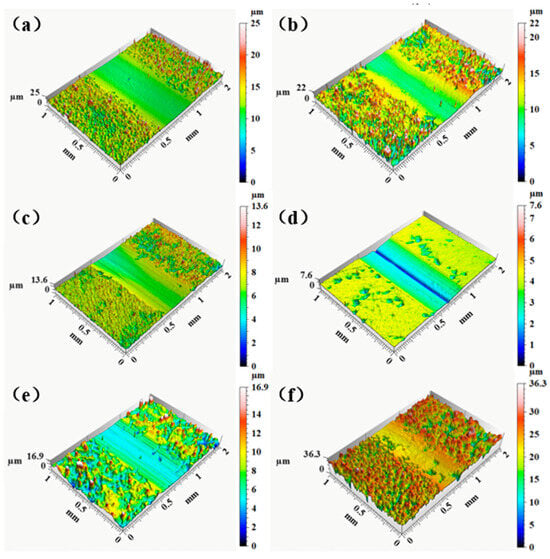

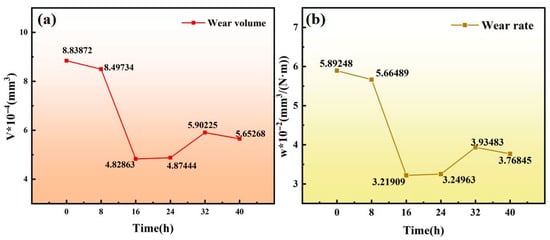

Wear rate serves as a critical parameter for evaluating the wear resistance of coatings. Figure 9 presents the reconstructed three-dimensional surface morphologies of the coatings after different cryogenic holding durations (0 h, 8 h, 16 h, 24 h, 32 h, and 40 h). Based on these morphological data, the wear volume of the coatings was calculated, with the computational results displayed in Figure 10b.

Figure 9.

Reconstructed 3D wear morphology of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating: (a) DCT0; (b) DCT8; (c) DCT16; (d) DCT24; (e) DCT32; (f) DCT40.

Figure 10.

Wear volume (a) and wear rate (b) of the coating after different cryogenic holding durations.

As shown in Figure 9, a notable reduction in the coating’s wear scar area was observed after cryogenic treatment. Both scar width and depth diminished, with the most pronounced improvement occurring after the 16 h process. Furthermore, cryogenic treatment led to a notable decline in both wear volume and wear rate of the coating. Wear volume and rate exhibited a non-monotonic trend with extended cryogenic holding time, initially declining before rising, which correlated with the coating hardness enhancement from cryogenic processing. Specifically, cryogenic treatment for 16 h was confirmed as the optimal duration, exhibiting the lowest wear volume at 482,863 μm3, corresponding to a wear rate of 0.032 mm3·(N·m)−1. This value represents 54.6% of that of the untreated coating—a reduction of 45.4%.

It is worth noting that when the cryogenic holding duration was extended to 24 h, the wear volume and wear rate remained almost unchanged. However, with further increases in holding time, both the wear rate and wear volume showed a slight upward trend, indicating a decline in wear resistance. Thus, optimal cryogenic treatment duration significantly enhances the anti-wear performance of Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coatings. However, excessively long treatment times may adversely affect wear performance, a pattern consistent with findings reported in existing studies on certain materials [].

Based on the preceding analysis, it is concluded that the reduction in wear volume and wear rate is attributed to the decreased average grain size induced by cryogenic treatment, which achieves grain refinement strengthening and consequently enhances coating hardness. Simultaneously, the increased dislocation density and microstrain likely suppress plastic flow and material loss during the friction process.

The evolution of coating hardness and wear performance with cryogenic processing time is consistent with Archard’s wear theory [], adhering to the relationship given in the following equation:

where V represents the wear volume, S denotes the sliding distance of the friction pair, K is the friction coefficient, FN indicates the applied load, and H signifies the microhardness. Experimental results reveal that under identical friction and wear test conditions, cryogenic treatment significantly enhances the hardness of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating through microstructural refinement. The hardened coating demonstrates improved resistance to abrasive penetration and plowing, consequently reducing wear volume. A smaller wear volume corresponds to superior wear resistance and higher hardness of the coating. Analysis suggests that the improved hardness and increased dislocation density following cryogenic treatment effectively suppress abrasive and adhesive wear mechanisms. However, when the treatment duration is excessively prolonged, leading to microcrack formation or enhanced brittleness, a slight increase in wear volume is observed. This phenomenon aligns with the trade-off mechanism between hardness and toughness, consistent with findings reported in existing literature [,].

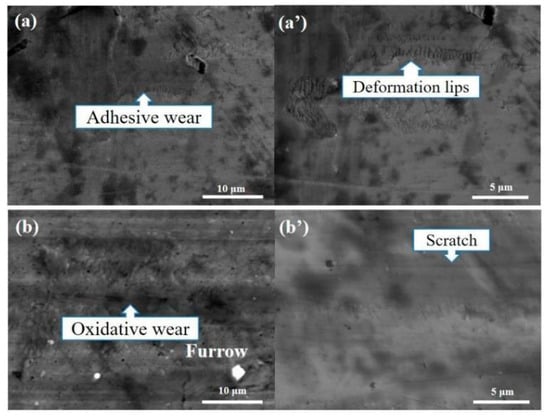

3.3.3. Wear Scar Observation

To further investigate how cryogenic treatment affects the coating’s wear mechanism, Figure 11 presents SEM images of the wear-induced microstructural features of the Ni–Co–Cr/SiC coating before and after 16 h of cryogenic treatment, revealing the evolution of wear behavior. Figure 11a,a’ display the wear scar morphology of the untreated Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating. The primary wear mechanism is adhesive wear, characterized by localized material accumulation or adhesion, accompanied by material transfer. As observed in Figure 11a′, deformed lips are present on the surface of the untreated coating, indicating that the substrate material underwent deformation due to high temperatures generated in localized areas during the friction process. In contrast, for the coating subjected to 16 h of cryogenic treatment, distinct plowing grooves along the sliding direction are visible in Figure 11b,b’. The wear mechanism transitions to abrasive dominance at this phase, with distinct oxidative characteristics concurrently appearing on the coating surface. Meanwhile, the 16 h treatment period produces significantly increased coating hardness while demonstrating effective suppression of adhesive wear mechanisms.

Figure 11.

Wear morphology of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating: (a,a’) DCT0; (b,b’) DCT16.

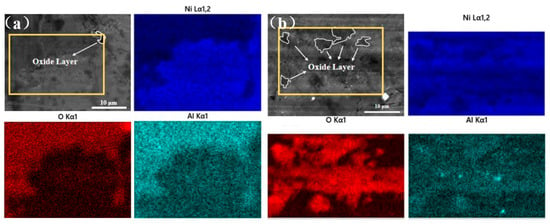

EDS elemental mapping and compositional results from wear scar analysis are provided in Figure 12 and Table 2, with data presented for both pre- and post-cryogenic treatment conditions. As shown in Figure 12, a significant amount of elements from the counter friction pair (Al and O) is detected on the surface of the untreated coating, indicating material transfer occurred between the coating and the counterpair during the friction process. This further confirms that the dominant wear mechanism is adhesive wear. Simultaneously, the localized aggregation of oxygen suggests that certain areas of the untreated coating also experienced oxidative wear to some extent. After 16 h of cryogenic treatment, the coating surface exhibits noticeable oxygen enrichment, and some regions show dark ablation features, indicating that oxidative wear remains present even after cryogenic treatment. Additionally, a small quantity of counterpair elements is still observed on the wear scar surface, implying that minor adhesive wear persists during the friction process. This can be attributed to the significant improvement in coating hardness due to cryogenic treatment, which reduces the probability of adhesive wear. However, the formation of an oxide layer also makes the coating more susceptible to oxidative wear under high-temperature conditions.

Figure 12.

EDS area scanning results of the wear scar on the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating: (a) DCT0; (b) DCT16.

Table 2.

EDS compositional characterization results of coatings DCT0 and DCT16.

Furthermore, the enhanced hardness of the coating after cryogenic treatment leads to more pronounced scratching and grooving caused by hard particles, making abrasive wear characteristics more evident.

This transition in wear mechanism is directly correlated with the enhancement of coating hardness. The untreated coating, with its lower hardness, experiences plastic deformation and atomic-scale bonding at surface asperities during contact with the counterface, leading to material adhesion and transfer. After cryogenic treatment, the significant improvement in coating hardness impedes plastic flow at the surface, thereby suppressing adhesive effects. Simultaneously, the hardened surface resists penetration by counterface asperities or third-party debris, causing material removal to occur primarily through micro-cutting and plowing—characteristic features of abrasive wear observed in SEM images. Additionally, EDS analysis confirms the consistent presence of oxygen on worn surfaces, verifying the persistent occurrence of oxidative wear. Although oxidation may become more pronounced after cryogenic treatment due to altered surface activity and stress state, it no longer serves as the dominant mechanism for material loss.

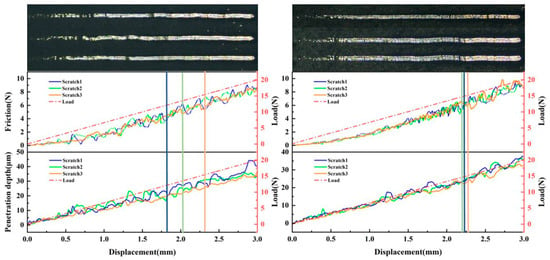

3.4. Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on the Bonding Properties of the Coating to the Substrate

As a protective coating, the adhesion performance between the coating and the substrate is also crucial. However, due to the difference in the thermal expansion coefficients of the coating and substrate materials, an excessively rapid cooling rate during cryogenic treatment may lead to stress accumulation at the coating-substrate interface, potentially causing coating delamination. This not only reduces the protective capability of the coating but may also result in dislodged coating fragments exacerbating wear on the substrate surface. Therefore, this study employed micro-scratch testing to evaluate the adhesion performance of the coating before cryogenic treatment and after 16 h of direct immersion treatment.

The bonding strength was evaluated through critical load values combined with comprehensive analysis of scratch morphology, friction force, and indenter penetration depth. Figure 13 presents the scratch morphology, friction force curves, and scratch depths for DCT0 and DCT16 coatings. Three tests were conducted for each specimen, revealing significant fluctuations in critical load values for the untreated coating, whereas the cryogenically treated coating maintained relatively stable values. The calculated average critical loads before and after cryogenic treatment were 13.64 N and 14.95 N, respectively. These results demonstrate that after 16 h of direct immersion in liquid nitrogen, the bonding strength between the coating and substrate not only remained intact but was substantially enhanced.

Figure 13.

Scratch morphology, friction force, and penetration depth of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating: (left) DCT0; (right) DCT16.

We propose that the synchronous uniform lattice contraction induced by cryogenic treatment in both coating and substrate generates beneficial compressive stresses at the interface. These compressive stresses effectively “lock” the interface by counteracting operational tensile stresses, thereby improving the coating’s bonding strength and spallation resistance.

4. Conclusions

This study provides an in-depth investigation of the microstructural evolution and performance enhancement of Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coatings induced by cryogenic treatment. The treatment promoted microstructural changes that improved the overall properties of the coating, particularly in terms of wear resistance. The following conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- Cryogenic treatment significantly improves the microstructure and properties of the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating. Among the process parameters, the cooling rate had a relatively minor effect on hardness and wear resistance, while lower treatment temperatures contributed to more pronounced strengthening effects. The holding duration exerted the most substantial influence on hardness, wear resistance, and adhesion performance. Based on comprehensive experimental results, the optimal process involves direct immersion in liquid nitrogen with a holding time of 16 h.

- (2)

- Cryogenic treatment does not alter the single-phase face-centered cubic (fcc) structure of the coating but refines the grain size and induces lattice contraction, accompanied by the accumulation of microstrain and dislocation density. After 40 h of direct immersion in liquid nitrogen, the average grain size decreased from 6.53 nm to 5.51 nm.

- (3)

- Within the holding duration range of 0–40 h, the hardness and wear resistance of the coating first increased and then decreased. The maximum hardness of 965.5 HV was achieved after 24 h of cryogenic treatment, representing an 11.7% increase compared to the untreated coating. After 16 h of treatment, the wear volume decreased to 482,863 μm3, and the wear rate was reduced to 0.032 mm3·(N·m)−1, only 54.6% of that of the untreated coating. When the holding time reached 24 h, the wear rate remained almost unchanged.

- (4)

- The untreated Ni-Co-Cr/SiC coating exhibited adhesive wear as its dominant mechanism. After 16 h of cryogenic exposure, the wear mode transitioned to abrasive wear. While oxidative wear persisted throughout, it became more pronounced following the treatment.

- (5)

- Cryogenic treatment enhances the bonding strength between the Ni-Co-Cr/SiC nanocomposite coating and the substrate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.; Methodology, Y.D. and M.L.; Validation, R.S. and H.D.; Formal analysis, X.Y. and D.C.; Investigation, X.Y., R.S., Y.D., M.L. and H.D.; Data curation, X.Y.; Writing—original draft, X.Y., R.S. and Y.D.; Writing—review and editing, D.C., M.L. and H.D.; Visualization, X.Y.; Supervision, D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52274320).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wu, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X. A high temperature wear-resistant Ni-based alloy coating for coppery blast furnace tuyere application. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 464, 129550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Dong, C.; Wang, S. Microstructure and Properties of Ni–Co Composite Cladding Coating on Mould Copper Plate. Materials 2019, 12, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrús, X.; Montiel, M.; Vallés, E.; Gómez, E. Electrocatalytic oxidation of methanol on CoNi electrodeposited materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 6705–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Kong, F. Understanding Mold Wear Mechanisms and Optimizing Performance through Nico Coating: An In-Depth Analysis. Metals 2023, 13, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Kong, F.J.M. Investigation and Improvement Strategies for Mold Fracture: A Study on the Application of a Pulse Electrodeposition Method for Enhancing Mold Lifespan. Materials 2023, 16, 7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimzadeh, A.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Walsh, F.C. A review of electrodeposited Ni-Co alloy and composite coatings: Microstructure, properties and applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 372, 463–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, Y.; Xue, Q.; Liu, H.; Xu, T. Microstructure and tribological properties of electrodeposited Ni–Co alloy deposits. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2005, 242, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovičević-Klug, P.; Sedlaček, M.; Jovičević-Klug, M.; Podgornik, B. Effect of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on Wear and Galling Properties of High-Speed Steels. Materials 2021, 14, 7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, Ü.; Bozkurt, F. Investigation of the Effects of Cryogenic Treatment on the Friction and Wear Properties of 36CrB4 Boron Steel. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 16209–16221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.H.S.; Israel, C.L.; da Silva, M.B.; Klein, G.A.; Soccol, L. Effects of deep cryogenic treatment on microstructure, impact toughness and wear resistance of an AISI D6 tool steel. Wear 2020, 456–457, 203382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari, M.; Cescato, D.; De Flora, M.G. Hot friction and wear behaviour of high speed steel and high chromium iron for rolls. Wear 2009, 267, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.M.; Ma, S.Y.; Wang, K.N.; Li, G.; Qu, Y.; Li, R. Effect of cyclic deep cryogenic treatment on corrosion resistance of 7075 Alloy. Met. Mater. Int. 2022, 28, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaz Ahmed, M.; Siddhi Jailani, H.; Rasool Mohideen, S.; Rajadurai, A. Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on Microstructure and Properties of CuBe2. Metallogr. Microstruct. Anal. 2016, 5, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyi, M.; Su, R.M.; Wang, K.N.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Li, R. Effect of deep cryogenic treatment on wear and corrosion resistance of an Al–Zn–Mg–Cu Alloy. Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 2021, 62, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, K.R. Effect of Cryorolling on Strengthening-Softening Transition in Deformation Twinned Cupronickel Alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A-Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2024, 55, 4747–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Synergistic Effects of Surface Texture and Cryogenic Treatment on the Tribological Performance of Aluminum Alloy Surfaces. Lubricants 2024, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmakumar, M.; Guruprasath, J.; Achuthan, P.; Dinakaran, D. Investigation of phase structure of cobalt and its effect in WC-Co cemented carbides before and after deep cryogenic treatment. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2018, 74, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuswamy, P.; Dinakaran, D. Evaluation of mechanical and metallurgical properties of cryo-treated tungsten carbide with 25% cobalt. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 3463–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmakumar, M.; Dinakaran, D. A review on cryogenic treatment of tungsten carbide (WC-Co) tool material. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2021, 36, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.H.; Huang, J.W.; Tang, Y.F.; Gu, L.-N. Effects of deep cryogenic treatment on microstructure and properties of WC–11Co cemented carbides with various carbon contents. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 3023–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Gu, K.; Wang, K.; Liu, X.; Cai, H.; Wang, J. Effect of deep cryogenic treatment on the fracture toughness and wear resistance of WC-Co cemented carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 85, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.H.; Qiu, X.T.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, G. Effects of repeated cycling cryogenic treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of hydrogenated diamond-like coatings. Thin Solid Film. 2023, 775, 139865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Duan, J.H.; Zhao, H.C.; Ye, Y.W.; Chen, H. Effect of cryogenic treatment time on microstructure and tribology performance of TiAlN coating. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 2021, 9, 035055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiadikobi, C.I.; Thornton, R.; Statharas, D.; Weston, D.P. The effects of deep cryogenic treatment on PVD-TiN coated AISI M2 high speed steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 493, 131248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, D.; Hua, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, R. Dispersion strengthening in Ni–Co–Cr–SiC coatings: Effects of particle-matrix adhesion and dislocation obstruction revealed by multiscale modeling. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 4490–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, F.; Küçük, Y.; Özbek, O.; Özbek, N.A.; Gök, M.S.; Altaş, E.; Uygur, İ. Effect of cryogenic treatment on wear behavior of Sleipner cold work tool steel. Tribol. Int. 2023, 180, 108301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensely, A.; Prabhakaran, A.; Mohan Lal, D.; Nagarajan, G. Enhancing the wear resistance of case carburized steel (En 353) by cryogenic treatment. Cryogenics 2005, 45, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Luo, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhang, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, X. Effect of Cryogenic Treatment on the Microstructure and Wear Resistance of 17Cr2Ni2MoVNb Carburizing Gear Steel. Coatings 2022, 12, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Xu, B.; Hao, L.; Sun, M.; Li, D. Influence of cooling rate during cryogenic treatment on the hierarchical microstructure and mechanical properties of M54 secondary hardening steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 851, 143659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.R.; Zhou, Z.C.; Wang, H.M.; Liu, J.Q.; Zhang, Z.B.; Gao, L.P.; Dong, C.; Su, W.X.; Wei, Y.M.; Zhao, H. Research on microstructure and mechanical properties of FeCoNi1.5CuB0.5Y0.2 high entropy alloy treated by cryogenic treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 907, 164310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, X.; Liang, X.; Guo, H.; Li, D.Y. Influence of different cryogenic treatments on high-temperature wear behavior of M2 steel. Wear 2017, 376–377, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Lv, Q.; Li, G.; Qu, Y.; Su, R.; Qiu, K.; Zhang, W.; Yu, B. Effect of cryogenic treatment on B2 nanophase, dislocation and mechanical properties of Al1.4CrFe2Ni2 (BCC) high entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 878, 145183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Huang, P.; Feng, Z.; Wei, Z.; Zu, G. Effect of Deep Cryogenic Time on Martensite Multi-Level Microstructures and Mechanical Properties in AISI M35 High-Speed Steel. Materials 2022, 15, 6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Meng, M.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Lei, G.; Zhang, H. Effect of deep cryogenic treatment on the microstructure and tensile property of Mg-9Gd-4Y–2Zn-0.5Zr alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 16, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yuan, X.; Hu, H.; Tian, P.; Long, M.; Chen, D. Microstructure evolution and wear resistance enhancement of nano-NiCoC alloy coatings via cryogenic treatment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 493, 131294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K. Impact of layer rotation on micro-structure, grain size, surface integrity and mechanical behaviour of SLM Al-Si-10Mg alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 9506–9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, H.; Sun, G.; Zhao, L.; Han, S.; An, J.; Lian, J. Optimizing mechanical and tribological properties of electrodeposited NiCo alloy coatings by tailoring hierarchical nanostructures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 450, 129027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, G.; Ueji, R.; Najafizadeh, A.; Monir-Vaghefi, S.M. Flow stress analysis of TWIP steel via the XRD measurement of dislocation density. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 2759–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. On the enhanced wear resistance of laser-clad CoCrCuFeNiTix high-entropy alloy coatings at elevated temperature. J. Tribol. Int. 2022, 174, 107767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.J.; Joo, S.-H.; Tsai, C.-W.; Yeh, J.-W.; Kim, H.S. Compressive deformation behavior of CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. Met. Mater. Int. 2016, 22, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.R.; Zhang, Z.B.; Wang, H.M.; Cao, Z.L.; Liu, J.Q.; Zhou, Z.C.; Dong, C.; Su, W.X.; Wei, Y.M.; Zhao, H.; et al. Modification of FeCoNi1.5CrCuP/2024Al composites subject to improved aging treatments with cryogenic and magnetic field. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 967, 171763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ji, P.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Jiao, J.; Lian, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, B. Effect of current density on the texture, residual stress, microhardness and corrosion resistance of electrodeposited chromium coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 471, 129868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellon, P.; Averback, R.S. Wear Resistance of Cu/Ag Multilayers: A Microscopic Study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 15288–15297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).