Abstract

Cultural models are simplified images and storylines that encapsulated what is regarded as typical for a social group. Cultural models of teachers include body images of dress, adornment, and comportment, and are useful in examining society’s standards and values. Two participants, Erin and Gabbie (pseudonyms), shared stories about their tattoos, which in the U.S. have historically been seen as a mode of resistance. These tattoos that reflected the teachers’ personal lives were regarded in light of the cultural model of the U.S. teacher, a typically conservatively dressed and coiffed female. According to discourse analysis of the participants’ stories, each teacher’s students did not interpret these tattoos in the same ways. Erin’s students were surprised at the tattoo and interpreted it as a sign she no longer fit the typical teacher mold. Gabbie’s students were not surprised at the tattoo but noted it as confirmatory evidence that she fit the needs of the alternative, nonmainstream school context where the cultural model would be ill suited. This analysis makes a case for more complex interpretations of teachers’ bodies that do not fit the mainstream cultural models of teachers.

1. Introduction

Social assumptions of what is normal help people prepare for actions and existence in the world. Notably, the term normal is problematic because it raises the questions of for whom it is normal and in which circumstances and, in general, it reinforces dominant paradigms, effectually marginalizing others. However, using normalcy as an organizing principle is useful because it reveals the social theories one is employing to make choices and guesses within the world [1]. One may assume that most experiences will be normal ones, and rightfully so, as this is the nature of normality. Therefore categorizing experiences as either meeting one’s expectations for normality or not can be a useful way to make sense of the world and act in it. These assumptions provide a frame for organizing life experiences.

In education, these organizing principles have shaped what societies at large have deemed typical in education. Cultural models [2,3] are tools in determining normalcy. Cultural models are “images or storylines or descriptions” based on a sociocultural group’s “taken-for-granted assumptions about what is ‘typical’ or ‘normal’” ([3], p. 59) that people use to judge their experiences. The cultural models associated with schools, as institutions that uphold social values, are particularly useful in examining a society’s standards.

Teachers are both practical and symbolic sites of what the institutions of schooling aim to convey as valuable [4]. A cultural model of teacher represents not only what is conventional but also what is idealized for the profession and for the society into which students are being indoctrinated. Cultural models of teachers often include rhetorical bodily images of what is socially valued; however, images of real life teachers may not match archetypal images and are thus vulnerable to critique. Real life teachers whose bodily images are outside the cultural model can more easily be disregarded, marginalized as less than optimal, and, in some cases, demonized as deviant.

Two participants, Erin and Gabbie (all names are pseudonyms), shared stories about their tattooed bodily images that reflected their personal lives. In a society where women might feel a level of social control over their bodies, tattoos can be personal expressions that highlight “power relations that surround the body” ([5], p. 57). The cultural model of a teacher image in the U.S. (i.e., a conservatively dressed and coiffed female) does not include tattoos, because culturally and historically in the U.S., tattoos have been a mode of resistance [5]; therefore, Erin and Gabbie deviated from the cultural model. According to discourse analysis of the participants’ stories, each teacher’s students seemingly did not interpret these deviations in the same ways, which has implications for how a teacher’s bodily images is viewed in context and how cultural models serve education in a society.

2. Theoretical Frame

The way people see the world and operate accordingly is based in part on beliefs and values, which Gee ([1], p. 78) presents as a type of social theory. A social theory involves “(usually unconscious) assumptions about models of simplified worlds” or what Holland and Quinn [2] and Gee [3] termed cultural models. As people suppose these simplified worlds to be real, they also judge the events and people of the real world against the cultural model.

In the most recent edition of An Introduction to Discourse Analysis, Gee ([6], p. 71) forwent the term cultural models for the term figured worlds. A figured world is “a picture of a simplified world that captures what is taken to be typical or normal,” therefore cultural models are absorbed as part of a figured world. Gee may have reasoned that the term figured world would call to mind a larger field than would cultural model, which seems more isolated and decontextualized.

Although both Gee [6] and Holland, Skinner, Lachiotte, and Cain [7] and have chosen to use figured worlds to encompass both cultural models and the simplified worlds in which cultural models appear, I have chosen to maintain the term cultural models for several reasons. First, cultural model emphasizes the cultural influence on a simplified image. The importance of the situated social, cultural, and historical influences cannot be emphasized enough. Second, the term model is ripe with connotations of stagnant images that permeate and surround the practices and problems in everyday life. People use a model as a fixed concept that can structure making sense of lived experiences. A model, such as a theoretical model or a physical model, is not fluid; it is posed as a stationary representation on to which ideas can be mapped. Lived experiences do not always match the model, at which point the model might be changed or the discrepancies get problematically ignored or masked to maintain the model [8]. In most cases, a model is held up as an immovable ideal and something to aspire to. Third, the word model is well-established in education as something a teacher both is (i.e., a model of how a woman should be) and what a teacher does to instruct students (i.e., a teacher modeling how to complete a task). I in no way disagree with Gee’s [6] and Holland et al.’s [7] choices to use the term figured worlds, but for these reasons, the term cultural model serves this research both theoretically and practically.

2.1. Cultural Models and Situated Meanings

Cultural models are “the typical stories […] stored in our heads […] in the form of images, metaphors, and narratives” ([6], p. 71). These stories are so typical that they can be called to mind with little effort. These images, metaphors, and narratives are so engrained in society that they exist outside people’s heads also, manifested through and within d/Discourse; Gee ([3], p. 7) distinguished between the lower-case “d” discourse as on-site language in the event, and the upper-case “D” Discourse as “one’s body, clothes, gestures, actions, interactions, ways with things, symbols, tools, technologies […] and values, attitudes, beliefs, and emotions […] non-language ‘stuff’.” Both discourse and Discourse are sites where cultural models are present and fueled.

Cultural models are useful both in practical and theoretical senses. Practically, cultural models function in the local, microdiscursive interactions people have with one another. People within the same social groups often share cultural models (i.e., an assumed sense of what is typical), which can serve as a starting point for understanding among people. Yet what is typical differs across cultural and social groups. Cultural models can be placed in relation to situated meanings. Situated meanings are understandings that “‘hang together’ to form a pattern that specific sociocultural groups of people find significant” ([3], p. 41). Many social groups can call the same cultural model “ideal” but find different situated meanings acceptable according to the context.

Theoretically, because cultural models manifest themselves within the larger macro-worlds of social institutions, we are able to use cultural models to analyze the “complex patterns of institutions and cultures across societies and history” ([6], p. 76). Cultural models are the boiled down emblems of the social values upheld by and within institutions. The Discourse (i.e., ways of being, including language, interactions, tools, and objects) valued in and by an institution can be complicated, and cultural models cut through complicated tenets and represent the principles of an institution in their most simple form. Therefore cultural models operate as a connector between the local micro events and the macro-world of institutions.

Gee ([6], p. 78), in writing about figured worlds of which cultural models are a part, wrote that they “are rooted in our actual experiences in the world, but, rather like movies, those experiences have been edited to capture what is taken to be essential or typical.” So these cultural models are not simply high theory; they are part of our everyday lives as we draw on archetypal cultural models to make sense of our complicated experiences (e.g., situated meanings). Books and media, which often make use of these archetypal images because they quickly and clearly convey a message, are reminders of how cultural models are inescapable in everyday life [9,10].

2.2. Cultural Models and Situated Meanings of Teacher

Assumptions are linked to the word teacher. These assumptions are due in part to the demographic descriptor of the average teacher in the U.S., where this study was conducted, being a White, middle-class, able-bodied, heterosexual woman in her early-to-mid forties [11,12]. The assumptions, however, go beyond demographics. Women teachers have historically been described as mother figures [10,13], compliant, sweet, well mannered [10,14], “all that is good, and wise, and lovely” ([15], p. 10), and conservative, patient, calm, and self-possessed [16]. Teachers are called to keep certain qualities in a fragile balance. For example, they should be self-regulating and yet be able to be regulated by others [17], and they should obscure their feminine bodies with dress, but not to the point of masculinization or androgyny [18]. This long-established idealized female teacher image persists. In general, teachers who style themselves counter to the conservative teacher image, including having tattoos, are greeted with unfavorable reactions and dress codes to reinforce the cultural model [4,19,20,21,22]. This model is repeated not just in the discourse of educational institutions, but also in the general media as a reflection of the larger cultural construction of what a proper teacher should be [9].

When one encounters a person called a teacher, one judges that teacher against the cultural model of the simplified world. The real teacher is always compared to the idealized version of teacher, and is therefore under pressure to rise to that unattainable ideal, always being in a position of falling short, partially because the real teacher is complex and open to contradictions while the cultural model is not.

A social group or groups can share what is an idealized teacher but may identify several situated meanings of teacher that are acceptable (or not) within certain contexts. Atkinson [19] detailed three categories inspired by a group of teacher education students: the apple jumper teacher (akin to what I refer to here as the idealized cultural model), who conceal their bodies with boxy attire including vests and jumpers with symbols of school (e.g., apples, rulers); the teacher babe, who wears stylish, form-fitting, body-revealing clothes; and the bland uniformer teacher, who adopts unremarkable nonfeminine business casual clothing (e.g., slacks and a blazer) that allows the her to navigate classroom duties (e.g., bending down, sitting on the floor). Atkinson makes the case that the apple jumper teacher indicated proper femininity, doing the impossible work of blending a virginal body and a motherly body, but was seen by the young teachers as old fashioned and thus threatening despite it being a widely acceptable teacher type. The teacher babe was a feminized but sexualized teacher and thus panned by the young teachers. The bland uniformer, as both defeminized and desexualized, was seen as the most professional and desirable. Although Atkinson critiques these categories as limited and flawed, they are constructions that matter in the lives of teachers, and regardless of any social group’s opinions of any one cultural model.

The body, as material and real, is one site where teachers are judged against the cultural model. People assume real teachers to have certain traits based on the bodily appearance and actions of their bodies, just as they judge the cultural model of teachers to be conservative and demure because their bodily appearance indicates so. The body is a site for meaning making.

3. Women Teachers’ Bodies

Physical bodies are always present, and it is precisely their constant existence that makes them less visible. The presence of bodies is expected, so they go unnoticed. When they do become a matter of focus, bodies are easily objectified, moving from whole person to body parts (e.g., breasts) or things (e.g., a hairstyle). For example, clothing, as portrayed in drawings and pop culture, is a site that informs limits of acceptable teacher bodily appearance. According to Weber and Mitchell’s [23] analysis of over 600 drawings of teachers by both students and teachers themselves, female teachers are most often drawn with their hair in a bun, wearing glasses and pearls, and usually a wide or sack-like skirt. The majority of students invoked the iconic image of a teacher, which as described by MacLure [22] is a modestly dressed woman, standing in front of students, with a nearby blackboard or presentation surface. Weber and Mitchell [23] found that when any images did rupture this idea of teacher, the teachers’ bodies were portrayed as fantastical figures in a far-fetched context (e.g., a teacher as a flying fairy), reinforcing the dowdy cultural model of teacher (See Figure 1), and nearly everything else is abnormal.

Figure 1.

The model of a dowdy schoolteacher is often a conservatively styled in bland dress with glasses.

Figure 1.

The model of a dowdy schoolteacher is often a conservatively styled in bland dress with glasses.

Women’s bodies are regulated to serve an institutional or external purpose [24,25]. The institution of schooling makes teachers objects of students’, parents’, administrators’, and the community’s gazes. These gazes send signals to a teacher about what is expected of a teacher’s body. The profession has a history of using observations of what happens in the professional realm of schools as evidence of the type of person one is or will be in the personal realm [26] and vice versa.

Waller’s [18] oft-cited sociological education study held integration of professional and personal lives as the key to being a prestigious teacher, explaining that the optimal image of a teacher was an earnest, well-mannered, conservative, stable person of high moral control. Fulfilling these expectations included integrating the teacher’s professional self and personal self, so that a teacher was an exemplar whether in or out of school. Lortie’s ([16], p. 97) analysis supported Waller’s description that the virtuous teacher in professional and personal realms was still the standard. However, Lortie did establish doubt that teachers were willing or able to integrate their personal and professional lives. In Lortie’s study, the belief that “everyone is watching” was socially and intellectually stagnating.

Other people regulate a teacher’s embodied actions until she regulates herself, because she is pressured to function within the institutional expectations or risk being disciplined [27]. Teachers or teacher candidates must decide to conform, resist, or find other options. The iconic classroom in popular culture (i.e., a teacher at the front, students in front of her) is a consistent, controlled symbol, so much so that other images are “alien or threatening” ([22], p. 14). When one accepts the notion that noniconic images are threatening, that resignation reinforces the constricted images that teachers are expected to embody. Resisting that resignation bolsters noniconic teachers by making them more purposefully present in schools.

Gendered images and identities have inconsistencies, but contradictions create opportunities for people to resist and for analysis of those resistances [28]. Contradictions exist in subverting gender norms, and there is no simple understanding of any image of teacher [23]. However, even if the intent is to subvert the system, it is how the bodily image is perceived by others that matters [28,29]. To better understand these images, one must take into account who saw the image, who created the image, the sociocultural meanings involved, and its sociohistorical influences—in short, the context cannot be ignored [28].

4. Methodology

In this focused portion of a larger study, Riessman’s [30,31] narrative methodology was used to answer how women teachers understand their bodies were read as texts amidst personal lives becoming known in the public realm. Two participants, Erin and Gabbie (pseudonyms), shared stories about their tattoos that reflected their personal lives. Both focal participants engaged in four one-on-one interviews totaling 4 hours and 56 minutes and 95 transcribed pages for Erin, and 3 hours and 2 minutes and 66 transcribed pages for Gabbie. Audio files and transcription were paired with researcher notes and photographed images to comprise the study’s data.

In-depth data gathering was used to offset one unchangeable factor; because neither woman was teaching in the K-12 classroom nor was in the same setting as their narratives of interest, observations of teachers in these settings were impossible, as was gathering data from students. Therefore, participants’ narratives stand as valuable sources of information. According to a feminist research approach [32,33], a participant is entitled to the opportunity to tell her stories in ways that convey her intended messages. Sharing narratives allowed participants to contrast their perceptions and experiences with the models of the broader culture [34].

Using thematic analysis [31], I determined that pertinent narratives were the stories that answered the research question: How did participants perceive their bodies were read as texts? These narratives were identified as being salient when participants talked about how they perceived others interpreting their bodies as aspects of their personal lives became known publically. This public knowledge did not always directly appear in the narrative. In the case of these two participants, Erin directly told her colleagues and students about her divorce. Gabbie classified her personal change becoming known as one in which people likely gradually pieced together an understanding about her sexuality as a lesbian. She directly “came out” to a few colleagues and hinted at her sexuality with a few students who were seeking perspective on their own sexuality. “Outings” about personal matters in public forums can be gradual [35], and thus public knowledge about Gabbie being gay also accumulated over time.

For these pertinent narratives, I marked the transcribed narratives with notational devices [3,36,37] to visually represent at a microstructure level how the narrative sounded during the telling (see Appendix). I also patterned the lines into stanzas, macrostructures (e.g., “SETTING, CATALYST, CRISIS, EVALUATION, RESOLUTION, [or] CODA” ([3], p. 110), and narrative parts, based on thematic content and linguistic markers (see Appendix). Examining the microstructure and macrostructure of narratives shows the choices speakers make to send intended message and how speakers organize meanings about their world.

I then used Gee’s [3,36] Discourse analysis to tie the language of participants’ stories to broader sociocultural meanings about women teachers. In addition to other discursive features, I examined participants’ I-statements, cause-effect assumptions, and use of cultural models to convey their perceptions of how others made sense of the teacher participants’ bodies. I analyzed images (i.e., non-lingual representations) connected to narratives for the content and others’ reactions to the image [31,38]. This analysis informed how participants saw their bodies as texts read within their schools.

5. Findings

Erin and Gabbie shared stories about tattoos on their bodies that reflected their personal lives. Erin was a newly divorced teacher. Gabbie was beginning to embrace her homosexuality, and although she was not completely and explicitly “out” to her entire school community, some people did know she was gay. Erin’s and Gabbie’s bodies were sites to express their personal lives. Pitts ([5], p. 57) pointed out that in a society where women might feel a level of social control over their bodies, tattoos can be personal expressions and can highlight “power relations that surround the body.” Erin’s and Gabbie’s stories, when examined beside each other, reveal how their bodies were texts that were read in relation to the cultural model of teacher.

5.1. A Story from Erin

During my second interview with Erin, I asked her to complete a timeline of the events surrounding the personal lives that became known in the public realm. While filling out her timeline, she realized that a linear representation was not sufficient for this time in her life; she saw events as circular. This revelation led her to explain one of the two tattoos she had on the inside of her foot. The tattoo that had a circular pattern (see Figure 2) was a remembrance of the time in her life when she was getting divorced. Erin said the Polynesian wave symbol served as a reminder to her that “when you come crashing down remember that you will get sucked back up and out…and that if you just keep yourself moving you’ll be ok.” In agreement with me, Erin elaborated on the idea that her body was a text that could be read.

Figure 2.

One of Erin’s two tattoos on the inside of her foot.

Figure 2.

One of Erin’s two tattoos on the inside of her foot.

- Part 3. Reading Tattoos

- I. EVALUATION

- Stanza J. Identifying with her body as text

- J1. and actually I think it is really interesting because it is

- J2. it is me making my body the text

- J3. it’s like read me read that this happened to me

- II. CRISIS

- Stanza K. Abstract

- K1. um and and students always notice my tattoos

- K2. they always do

- III. SETTING

- Stanza L. When students read tattoos

- L1. it’s not immediate usually um

- L2. it’s usually a couple months in

- IV. CRISIS

- Stanza M. Students notice tattoos

- M1. but they're like •(gasp) you have a tattoo …

- V. EVALUATION

- Stanza N. Moving categories

- N1. you’re like all of a sudden you get placed in this different category

- N2. you know like you’re not the teacher that they shove in the closet every night and take the battery out of you know

- VI. RESOLUTION

- Stanza O. Students ask about meaning

- O1. and um so yeah so and

- O2. and obviously kids have always asked like what is that and I [say] Polynesian wave symbol that’s it //

A cultural model is at work in this narrative, as the simplified image or storyline that involves assumptions about what is normal [2]. Erin posited the cultural model of a proper teacher being the “teacher that they shove in the closet every night and take the battery out of” (N2). This cultural model of teacher exists only for the classroom, without a personal life to complicate her professional world. This teacher image evokes ideas of an automaton, who does not need to think and is controllable. There is little indication as to what this teacher would look like, but it is clear the teacher would not be tattooed. This cultural model of teacher without a personal life yields to her surrounding professional context. She just would not have a tattoo, as a personal expression and part of reclaiming her body from confining sociocultural pressures [3]. Erin posited this cultural model as one that her school community used to organize experiences and provide limits about what an appropriate teacher is.

Erin represented a situated meaning of the word teacher in the context of her school. Erin described the school community as one that “fed on drama,” where community involvement included lawsuits and “calling teachers on the floor.” She cited two teachers who were “dragged out of that community because of parent gossip.” According to Erin, her students’ surprise at her tattoos was a signal that she did not fit the iconic view of what a teacher should be. Erin explained that a student typically did not expect her to have tattoos. According to Erin, learning that she did have tattoos changed the meaning they developed about her as a teacher. Erin’s body was central in this meaning making as it was judged against a cultural model of teacher. Erin presented this narrative as a typical and generic exchange with her students, not as a single event with a specific group of students.

Erin believed that there was a change in how students thought of her after they realized she has tattoos. By saying, “all of a sudden you get placed in this different category” (N1), Erin thought her students once considered her the kind of woman who existed as an uncomplicated teacher operating only to serve her classroom, a teacher who meshed with the model; once students noticed her tattoos, Erin perceived that they took her out of that cultural model category and put her into “this different category” (N1). Erin did not explain what the different category was, only that it was not the cultural model she was once a part of. There was some evidence that Erin was resisting the cultural model of teacher, not only by having a tattoo but also by a specific statement; Erin admitted, “I didn’t want kids to think I was the teacher that went in the closet and had her battery taken out each night,” so she read herself as a teacher outside the cultural model.

Erin believed that some students supported Erin’s resisting the iconic model of teacher and some did not. Erin supposed students ranged in their interpretations of her newly revealed situated meaning of teacher. She said, “There’s some kids who … they’re really interested in the person that you are inside.” Erin said, “Um I think there’s other kids who they want to keep you in the classroom. It’s like I don’t want to know that you... get sick or… just you come in do your job; I’ll do my little job.” Although students may have had little information about the circumstances of her divorce that led to Erin getting her tattoos, according to Erin, it was her bodily image that allowed students to see the possibility of Erin’s personal life. It was also Erin’s bodily image that allowed students to read her as outside the cultural model of teacher.

5.2. A Story from Gabbie

Gabbie’s first teaching job was at a small private secondary boarding school in New England called Blair Mill School. As part of her job assignment, she lived in a dorm with students and two other faculty members, blurring the professional and personal divide. The boarding school facilitated students and teachers being in each other’s lives outside the classroom.

Like Erin, Gabbie had a tattoo, but the contexts in which Erin and Gabbie taught and the expectations for these teachers were not the same. Therefore, the meanings developed about their respective tattoos were not the same. Cultural models are socially, culturally, and historically determined [1]. Cultural models of teachers may be recognizable by several social groups, revealing a picture of what society at large values, but groups do not necessarily value the models in the same ways or to the same degree. Different social groups may have varied interpretations of a cultural model, and thus different interpretations of situated meanings that are in relation to the cultural model. That is to say, a situated meaning of teacher may be counter to a cultural model, but it might not be a problem because the entire school context might be counter-culture. In Gabbie’s case, the cultural model of teacher may have been recognizable, but the social group did not see it fitting their values, making it favorable for her tattooed self as an acceptable situated meaning of teacher.

A sketch (see Figure 3) of Gabbie’s tattoo hung in Gabbie’s dorm room apartment, where students regularly had access. One student named Karen asked Gabbie what the sketch was, and Gabbie told Karen it was a tattoo that she had. Karen’s response was a simple, “Cool.” This image resurfaced when Karen created a quilt project in Gabbie’s women’s studies class. Gabbie told the following narrative about Karen’s project on the history of women communicating through quilting (see Figure 4).

Figure 3.

The sketch of Gabbie’s tattoo that hung in her dorm apartment at Blair Mill School.

Figure 3.

The sketch of Gabbie’s tattoo that hung in her dorm apartment at Blair Mill School.

Figure 4.

The sketch of Gabbie’s tattoo that hung in her dorm apartment at Blair Mill School.

Figure 4.

The sketch of Gabbie’s tattoo that hung in her dorm apartment at Blair Mill School.

- IV. EVALUATION

- IV. F. Understandings of persons in the class

- F1. And [Karen] pulls this quilt out

- F2. and on this quilt I swear to god there were TEN panels

- F3. and on each panel it symbolized how she saw the person in the class

- F4. and we had one guy that took the class

- F5. so for his it was like a lacrosse stick and I forget the other thing

- F6. so she like had a camera and a running shoe for Dana

- F7. and like a soccer ball and skis for Jan

- F8. and for me she had like this design

- F9. that actually ended up becoming a tattoo::o that I got

- F10. actually

- F11. it’s like this ah it’s this graphic symbol

- F12. with a woman symbol and a swan

- F13. that my friend designed

- F14. it was really cool um

- V. RESOLUTION

- Stanza F. Emotional connection

- F1. and at the very END she gave me the quilt

- F2. and I was BAWLING

- F3. I was like this is aMAZing

- VI. CODA

- Stanza G. Quilt in personal space

- G1. and the quilt still hangs like in my apartment to this day//

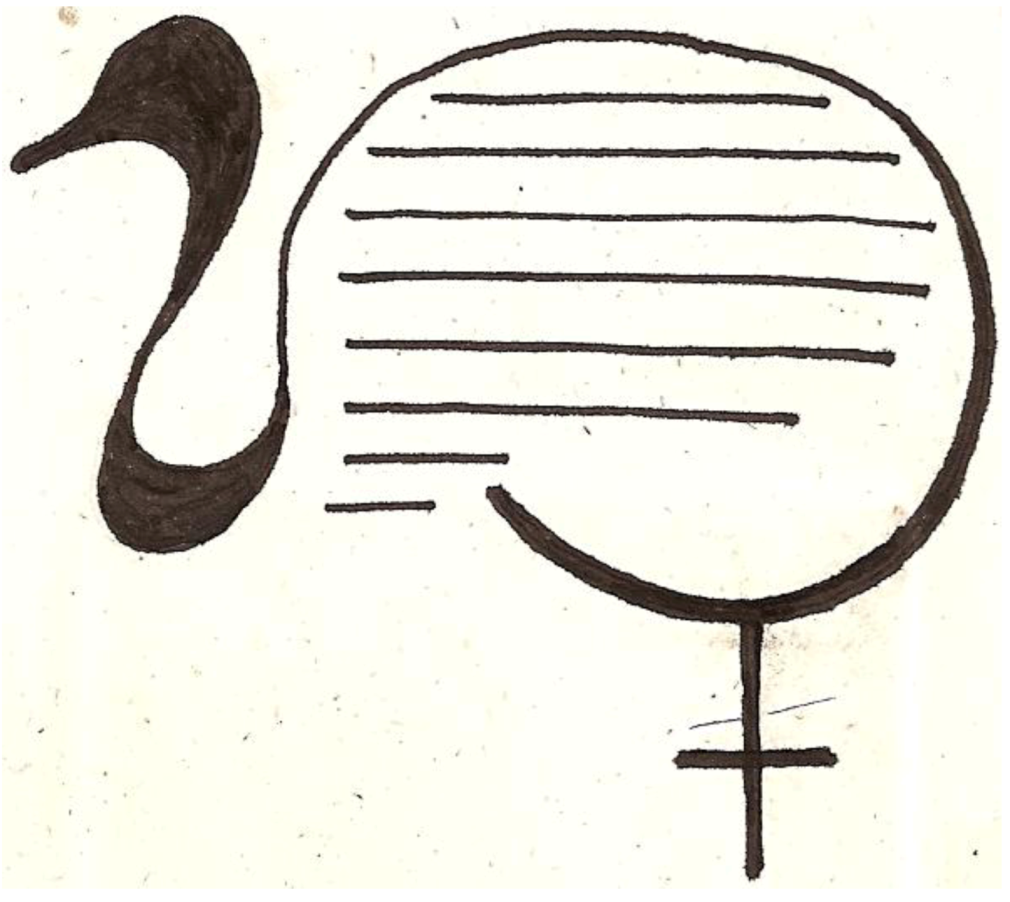

The sketch of Gabbie’s tattoo and the symbol the student made for the quilt (see Figure 5) are not exactly alike, but they have similar characteristics. Both show an image of a swan that according to Gabbie meant the power of woman, an approximation of the female symbol ♀, and the letter G for Gabbie. The sketch and the quilt symbol are different in curvature, the position of the letter G, and color. Karen included enough of the components (e.g., the swan, ♀, and the letter G for Gabbie) to show she had some sense of the meaning behind the image. The tattoo did not definitively reveal matters of Gabbie’s homosexuality, although her students could have interpreted it that way. It is possible that Gabbie’s role as a women’s history instructor prompted students to see the women-centered symbol as evidence of Gabbie’s passion about women’s issues. Gabbie made her intended meaning of the tattoo known within the research context, but it is unclear how students interpreted the content of the tattoo within the school context.

It is possible, however, to examine Gabbie’s perceptions of how the students saw her tattoo in light of the cultural model of teacher. Unlike Erin’s story, Gabbie provided no evidence that her students were shocked at Gabbie having a tattoo. There was no evidence that students knowing about their teacher’s tattoo placed her in “a different category.” If anything, Karen’s quilt and Gabbie’s reaction celebrated how Gabbie was represented by her tattoo. The language “I was BAWLING” (F2) and “I was like this is aMAZing,” (F3) emphasized Gabbie’s joy in her students’ work. Gabbie was still displaying the quilt in her apartment almost fourteen years later at the time of our interviews (G1), reinforcing the pride she felt in that quilt project and how she was represented.

Figure 5.

Symbol that represented Gabbie on a student’s quilt project. The symbol was the student’s version of Gabbie’s tattoo.

Figure 5.

Symbol that represented Gabbie on a student’s quilt project. The symbol was the student’s version of Gabbie’s tattoo.

The Blair Mill students created meaning from Gabbie’s tattoo in relation to a cultural model of teacher. Both Gabbie and the students may have been aware of the cultural model of teacher that lives only for the classroom with no personal life, but that cultural model seemed ill fitting with their somewhat unusual school setting. Due to the alternative school context, a situated meaning of teacher served the context better than the cultural model idealized on a wider cultural scale. Gabbie was in a context that melded personal and professional lives. The boarding school arrangement facilitated students and teachers being in each other’s lives outside the classroom. Therefore students saw teachers as people who had personal lives outside the classroom. Further, Gabbie confirmed that the school ethos was welcoming of difference. At the time, Gabbie did not feel secure being an “out” lesbian although Blair Mill offered a “welcoming open environment,” where the leadership encouraged “respecting diversity.” When I asked Gabbie, “Do you think that you could have been out at Blair Mill?” she responded, “Yes, I could have. I just wasn’t comfortable with myself at that time.” Gabbie’s view that a teacher’s homosexual personal life would be accepted exemplified that the expectations for teachers in Gabbie’s school were influenced by the context.

One might predict, in the least, tolerance at a teacher having a tattoo, but one cannot assume that a teacher with a tattoo was the expectation at Blair Mill. Although Karen’s response to the tattoo was an unfussy “Cool,” the attention Karen gave to the tattoo implies that Gabbie having a tattoo was notable. The student, Karen, chose images that “symbolized how she saw the person in the class” (F3), and Karen gave the tattoo symbol primacy. Despite Gabbie being involved in several school-sanctioned activities, such as coaching basketball and soccer, Karen did not choose to represent Gabbie by those activities as she did with the students in the class. The tattoo symbol made an impact on Karen, but there was no evidence that Karen read the tattoo as a sign that Gabbie was trying to subvert the cultural model of teacher. In fact, the cultural model of teacher was already subverted by the school arrangement, so there was little reason for Gabbie’s tattoo to be seen as a sign of rebellion to the simplified automaton teacher. Based on the school context and the stated meaning of the quilt, the tattoo seemed more so to be interpreted as a sign of who Gabbie was as a person. It just happened that who Gabbie was as a person fit well with the valued situated meaning of teacher at Blair Mill.

In both narratives, the issue was not a teacher having tattoos as much as it was how that sign was read in relation to the expectations of the people involved in the context. Erin was resisting the cultural model to carve out the possibility for a different situated meaning of teacher. Gabbie did not need to carve out that space for a different kind of teacher because the context had already created the opportunity for a different teacher image. Regardless of the level of acceptability of a teacher with tattoos, both Erin’s and Gabbie’s bodies were sites for meaning making. Their teachers’ bodies provided visual input about who these teachers were in their personal and professional lives and how their situated images compared to the cultural model of teacher.

5.3. Summary

Erin’s and Gabbie’s narratives showed that although the cultural model of a teacher (i.e., the iconic image of a conservatively styled female) does not include someone with tattoos, the presence of tattoos on a teacher does not yield a default meaning. It is true that culturally and historically in the United States, tattoos are a mode of resistance to mainstream culture [5], so evidence exists that both Erin and Gabbie deviated from the cultural model. However, students interpreted these deviations in different ways.

Erin believed that her students interpreted her tattoos as evidence that she no longer matched the cultural model they expected. Gabbie’s tattoo was also a break from the iconic image of teacher, but because the school was set for a different type of teacher, the cultural model had already been set aside. In both narratives, the issue was not a teacher having tattoos as much as it was how that body was read in relation to how the community regarded the cultural model.

Both Erin’s and Gabbie’s bodies were sites for meaning making. Their teacher bodies provided visual input about who these teachers were in their personal and professional lives and how their situated images compared to the cultural model of teacher. According to Erin, it was her tattooed body that allowed students to see the possibility of Erin’s personal life. And for Gabbie, visualizing her body with a tattoo was simple confirmation of the personal life that her students already knew existed.

6. Discussion

This study began with the idea of exploring more complicated stories and images of teachers than the iconic cultural model of teacher could offer. The creation and maintenance of the iconic image of teacher may provide a level of security for students, parents, other teachers, administrators, and community members in setting expectations for teachers. The iconic image may also serve to attract others into the profession who are lulled by the simplistic image.

This present study offers images that do not match the iconic image. Erin’s and Gabbie’s tattoos indicated they were resisting the iconic image of teacher. It was unclear if some students wanted them to resist that image; therefore it is ambiguous whose needs and wants are being addressed when the cultural model is resisted. The question of whose needs and wants are being served goes beyond the scope of this study and is likely a subject for future research, because the issue is pertinent for the teaching field and society at large.

Because cultural models are not rhetorical devices but factor in teachers’ lives, teachers need the opportunity to improve their analytical skills regarding cultural models. Teachers are already making complicated decisions about their publically viewed images every time they step into the public realm of the classroom. Further, the increased use of social networking websites among women who may enter future teacher education classrooms [39] is an opportunity for teachers to represent their personal and professional lives. On personal social networking pages, users create images that may show resistance to the cultural model of teacher, but teachers also need guidance in how resisting the cultural model of teacher on these sites has affordances and limits. Once those understandings are developed teachers will be better able to resist unfavorable or unwanted meanings of teacher.

Considering this study, teachers need to be asked to attend to how their bodies are texts that are interpreted for meaning about who they are as teachers and people. Advice for teachers needs to go beyond covering up tattoos and piercings [40]. One’s appearance is only part of the matter. Teachers and teacher education students need to be encouraged and supported in evaluating school contexts and in giving thought to people’s expectations regarding their bodies in those contexts.

Erin’s and Gabbie’s stories show that perhaps neither Waller [x] nor Lortie [x] presented a nuanced enough view of teachers. Both Waller and Lortie acknowledged the extent to which teachers are on display as people seek to understand how teachers’ personal lives are in concert with their profession. Waller claimed that teachers would have to project the idealized cultural model both in and out of school, and Lortie doubted integration of personal and professional lives was even possible. However, it was exactly Gabbie’s integration of her personal and professional lives outside the cultural model that led to a successful teaching experience. Also, Erin’s sloughing off the cultural model image raised her students’ curiosity but not necessarily disapproval. Even though both teachers’ bodily images may have been judged in comparison to the idealized teacher image, they were not ostracized for it within their teaching contexts.

Supporting teaching in evaluating their school contexts is not just important for early-career teachers being indoctrinated into the profession. Teachers change and schools change, despite the reductive portrayals of teachers and schools that are seemingly constant [41]. A teacher may find herself fitting in well in the school context at the beginning of her career, but less so at a later point. It would behoove a teacher to know how to evaluate her situation in order to be ready to leave that setting, work to change that setting, or leave the profession in search of a better employment situation. Without understanding how she is read by others, a teacher might believe the reductive portrayals of schools and think she is better off leaving teaching altogether because she has assumed all schools are the same, when, in fact, schools can be quite distinct.

Appendix

Table 1.

Notation and Arrangement for In-depth Transcription.

| Notation | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Part 1. Part Label | Part number with bold upper and lower case print indicated the label of the part and is similar to a title for the narrative. |

| II. SECTION | Roman numeral and bold capitalized print indicates macrostructure section of narrative. |

| Stanza A. Description | Stanza letter with bold label with the first letter capitalized indicates the purpose or topic of the data clump in the narrative. |

| A1. | Capital letter and number indicates the stanza and line number spoken by the participant. |

| C: | Indented, italicized capital letter C and colon indicates the researcher Christine is speaking. |

| // | Double slash marks indicate the voice has a pitch that sounds final. |

| word | Underline indicates stressed word or word segment |

| WORD | Capitalized word or word segment indicates an emphatic tone |

| .. | Double periods indicates a pause. |

| :: | Repeated colons indicates elongated sound; the longer the row of colons, the longer the sound. |

| ( ) | Parentheses indicate an action or sound, such as (clears throat) or inaudible speech recorded as accurately as possible. |

| ↑ | Sound has a rising intonation compared to the pitch that came before. |

| ↓ | Sound has a falling intonation compared to the pitch that came before. |

| ◦word◦ | Degree signs indicate quieter speech |

References

- Gee, J.P. Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses, 2nd ed; RoutledgeFarmer: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Models in Language and Thought; Holland, D.; Quinn, N. (Eds.) Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987.

- Gee, J.P. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, 2nd ed; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cooks, L.; LeBesco, K. Introduction and the pedagogy of the teacher’s body. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2006, 28, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, V.L. In the Flesh: The Cultural Politics of Body Modification; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.P. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, 3rd ed; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, D.; Skinner, D.; Lachiotte, W.; Cain, C. Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Archaeology of Knowledge: And the Discourse on Language; A.M.S. Smith, Trans.; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, M. The Hollywood Curriculum: Teachers in the Movies; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grumet, M. Bitter Milk: Women and Teaching; The University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Strizek, G.A.; Pittsonberger, J.L.; Riordan, K.E.; Lyter, D.M.; Orlofsky, G.F. Characteristics of Schools, Districts, Teachers, Principals, and School Libraries in the United States: 2003–2004 Schools and Staffing Survey (NCES 2006-313 Revised); U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zumwalt, K.; Craig, E. Teachers’ characteristics: Research on the demographic profile. In Studying Teacher Education: The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education; Cochran-Smith, M., Zeichner, K.M., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 111–156. [Google Scholar]

- Alsup, J. Teacher Identity Discourses: Negotiating Personal and Professional Spaces; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, F.R. The Schoolma’am; Arno Press: New York, NY, US, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Beecher, C.E. The Evils Suffered by American Women and American Children: The Causes and the Remedy; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1846. [Google Scholar]

- Lortie, D.C. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study; The University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Biklen, S.K. School Work: Gender and the Cultural Construction of Teaching; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, W. The Sociology of Teaching; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, B. Apple jumper, teacher babe, and bland uniformer teachers: Fashioning feminine teacher bodies. Educ. Stud. 2008, 44, 98–121. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, O. Schools enforce dress codes—for teachers. USA Today 2003, 6d. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T. Performing a/sexual teacher: The Cartesian duality in education. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2006, 28, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLure, M. Discourse in Educational and Social Research; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, S.; Mitchell, C. That’s Funny, You don’t Look like a Teacher! Interrogating Images and Identity in Popular Culture; Falmer Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, J. (Creator); Jhally, S. (Producer) Killing us Softly 3: Advertising's Image of Women [Motion Picture]. Available from Media Education Foundation, 60 Masonic Street, Northampton, MA 01060, 2000.

- Sawicki, J. Disciplining Foucault: Feminism, Power, and the Body; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot, S.L. Worlds Apart: Relationships between Families and Schools; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison; A. Sheridan, Trans.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- de Lauretis, T. Alice doesn’t: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bordo, S. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Analysis; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, A. Interviewing women: A contradiction in terms. In Doing Feminist Research; Roberts, H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1981; pp. 30–61. [Google Scholar]

- Reinharz, S. Feminist methods in social research; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Personal Narratives Group, Interpreting Women’s Lives: Feminist Theory and Personal Narratives; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1989.

- Ome, J. “You will always have to out yourself”: Reconsidering coming out through strategic outness. Sexualities 2010, 14, 681–703. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.P. A linguistic approach to narrative. J. Narrative Life Hist. 1991, 1, 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, G. Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation; Lerner, G.H., Ed.; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart, A.; Madden, M.; Macgill, A.R.; Smith, A. Teens and Social Media: The Use of Social Media Gains a Greater Foothold in Teen Life as They Embrace the Conversational Nature of Interactive Online Media. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2007/Teens-and-Social-Media.aspx (accessed on 25 October 2012).

- Obrycki, L. Professionalism: What it means for a new teacher. In 2009 Job Search Handbook for Educators; American Association for Employment in Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2008; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot, S. Lives of teachers. In Handbook of Teaching and Policy; Shulman, L., Sykes, G., Eds.; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).