Abstract

Drawing on Sen’s capabilities approach and digital empowerment frameworks, this study investigates digital literacy as a mediating factor in the conversion of structural resources into empowerment outcomes for indigenous women artisans of native cotton in northern Peru. A cross-sectional explanatory study involving 100 craftswomen used structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to examine the impact of technological infrastructure, sociodemographic factors, and sociocultural knowledge on economic, personal, and social empowerment, with digital literacy as the necessary mediating mechanism. A 45-item questionnaire assessed predictor variables, the four mediator dimensions (cognitive, technical, social and communicative competencies) and the three domains of empowerment as dependent variables. PLS-SEM analysis in SmartPLS 4.0 showed that the model fit well (SRMR = 0.072, CFI = 0.931) and that the structural factors accounted for 80.4% of the variance in digital literacy. The mediator had a large effect on all areas of empowerment but had the largest effect on economic empowerment (β = 0.846, R2 = 0.709) compared to personal and social empowerment (β = 0.618, β = 0.628, R2 ≈ 0.37). The indirect effects validated the mediating role of digital literacy, demonstrating its function as an essential conversion mechanism that transforms infrastructural, sociodemographic, and knowledge resources into tangible empowerment gains. The results provide empirical support for skills-based frameworks in digital inclusion initiatives, advancing SDGs 5, 8, and 9 by illustrating how digital skills empower vulnerable artisanal communities to transform traditional knowledge and access to technology into multifaceted empowerment outcomes.

1. Introduction

Structural gender inequalities in rural areas are one of the main barriers to achieving sustainable development, because they prevent women from participating and competing in an economy where traditional forms of production coexist with the new opportunities created by digital technology. Among Peruvian rural women producers, structural obstacles still persist, such as the scarce adoption of digital technologies, insertion in formal markets and connection with economic networks that make their productive development and empowerment viable [1,2]. Among them, native female cotton artisans in Morrope still face such barriers. This double exclusion—gender and digital—reinforces the vulnerability of these craftswomen, whose ancestral knowledge and productive practices will not be able to become competitive strengths in current economic systems. Recent studies show that technological appropriation presents different obstacles according to gender in different rural contexts, where women still have very restricted access to digital platforms and services [3,4]. These results, observed on a global scale, confirm the digital divide affecting rural women artisans and open the question of what factors predict their empowerment. How does becoming digitally literate transform their socioeconomic reality?

The combination of gender equality theories and digital literacy theoretical frameworks offers a holistic look at how technological skills can empower women in rural areas. Digital literacy goes beyond technical skill and involves essential aspects of contemporary empowerment, such as equal access to information, effective communication, and economic participation [5,6]. This multidimensional conceptualization is consistent with recent research that recognizes digital skills as mediators between classic structural factors of empowerment and its contemporary manifestations [7,8]. Digital literacy involves cognitive, social, technical, and communicative aspects that enable female economic inclusion by providing access to information, business, and social capital ecosystems [9,10]. Structural equation modeling to investigate these complex relationships is a methodologically robust way to disentangle multifactorial causal chains and conceptualize empowerment as a multidimensional construct [11,12].

While more and more researchers are interested in how digital technology can empower women, there is still a gap in how digital literacy can empower women in rural artisanal communities. Although many studies have found positive associations between access to technology and female empowerment [13,14], quantitative evidence on the mediating mechanisms of digital literacy remains scarce, particularly in specific cultural and economic contexts, such as indigenous cotton textile crafts [15,16]. Recent studies show that there are still gender gaps in participation in domestic enterprises and that women-led innovations face institutional barriers that restrict their potential to use digital technologies for the Sustainable Development Goals [17,18,19]. These findings point to the need for a contextualized line of research that explores digital literacy as a mediator in specific cultural and economic contexts, beyond generalizations that obscure local singularities.

Morrope was chosen as a case study because it is a place where ancestral knowledge of native cotton cultivation, artisanal systems of production, and current demands of commercial digitization intersect, manifesting the forces transforming traditional artisanal communities around the world. This district is one of the few places in the Americas where the native cotton species Gossypium barbadense is still planted and artisanal textiles are made, with the possibility of being declared intangible cultural heritage by [20]. This opens up opportunities and challenges that enrich the research findings, investigating the appropriation of technology in communities with traditional roots. As a middle-income country with an expanding digital infrastructure but with large inequalities between rural and urban areas (where female Internet access is 39% compared to 85% in urban areas) [21], Peru is a case to study theories of digital inclusion in contexts of economic change. Recent macroeconomic studies confirm that measures of gender inequality predict systematic differences in female economic participation, but localized empirical evidence is needed to inform contextualized policies [22,23]. The purpose of this research is to address these methodological and contextual gaps by applying structural equation modeling to analyze the mediating role of digital literacy in the empowerment of indigenous female cotton artisans, whose ancestral knowledge and commercial integration difficulties differ from other rural producer groups, providing quantitative evidence for Latin America, still underrepresented in the literature on digital literacy and female empowerment. This research provides quantitative evidence for Latin America, still underrepresented in the literature on digital literacy and female empowerment.

The objective of this research is to establish the mediating role of digital literacy on socio-demographic, technological and socio-cultural factors in the economic, personal and social empowerment dimensions of native cotton artisans in Mórrope, Peru, using structural equation modeling with a PLS-SEM approach. The article explores existing knowledge gaps on how digital skills translate into actual empowerment outcomes for vulnerable women in traditional economies, where recent evidence suggests that women’s economic empowerment through technological innovation must take into account gender-specific enablers and barriers [24,25]. The results provide empirical evidence in line with SDGs 5, 8, and 9 by showing numerical evidence on how digital literacy interventions can empower women in artisanal communities. By measuring digital literacy as a mediating variable in these complex causal relationships, the study creates actionable insights for policymakers and development practitioners, offering an empirically verified, methodologically replicable and culturally adaptable model for other artisanal and rural contexts around the world.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Rural Women’s Empowerment

Sen’s capability approach constitutes the theoretical framework underpinning the conceptualization of empowerment as a multidimensional process wherein structural resources are converted into outcomes through individual capabilities [11]. This perspective distinguishes among available resources, transformative capabilities, and outcomes, transcending reductionist perspectives that conflate empowerment with quantitative measures of well-being. For indigenous cotton artisans, this framework elucidates how ancestral knowledge requires contemporary mediation mechanisms to translate into economic value within globalized markets. In this regard, ref. [1] provide empirical evidence that digital skills function as conversion capabilities, transforming mobile technology access into measurable empowerment gains among rural women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh, with composite empowerment indices increasing from 37.47% to 61.92%.

Furthermore, gender equity theory and intersectional approaches provide the analytical framework for understanding how structural gender inequalities intersect with other identity markers—including rurality, ethnicity, and socioeconomic class—to produce differentiated patterns of exclusion and marginalization [26]. The ability to exercise choice incorporates three interrelated dimensions: resources (defined broadly to include not only access but also future claims to both material and human and social resources), agency (including processes of decision-making as well as less measurable manifestations such as negotiation and resistance), and achievements (well-being outcomes) [27]. In this sense, ref. [28] provide empirical evidence demonstrating that economic empowerment constitutes a multidimensional process requiring individual action, supportive public policies, and institutional changes. Multidimensional empowerment encompasses three analytically distinct yet empirically interrelated dimensions: economic (control over financial resources and market access), personal (self-efficacy and decision-making capacity), and social (community participation and social recognition) [27,29]. Consistent with this perspective, ref. [30] demonstrate that income diversification, credit access, and training programs significantly predict women’s entrepreneurial performance in rural Africa, findings that inform the present structural equation modeling approach.

Hypothesis 1.

Technological factors positively predict digital literacy of native cotton women artisans.

Hypothesis 2.

Sociodemographic factors positively predict digital literacy of native cotton craftswomen.

Hypothesis 3.

Knowledge-related factors positively predict digital literacy of native cotton craftswomen.

2.2. Digital Literacy as a Theoretically Mediated Mechanism

Sen’s capabilities approach provides the theoretical basis for thinking of digital literacy as a conversion agent, rather than as a structural resource or contextual mediator. Here, conversion factors are learned skills that transform resources (means) into achieved functionings (valued outcomes), being the mediating mechanisms that enable the translation of structural opportunities into realizations. This analytical difference is theoretically necessary: technological infrastructure, socio-economic resources and local knowledge systems are structural preconditions but are latent without the transformative potential of digital literacy. Conversion factors differ from resources in that they are learned capabilities that enable individuals to harness the empowering potential implied by structural opportunities. The mediating specification applies this theoretical framework, illustrating how resources require transformative mechanisms to generate change.

The conception of digital literacy as mediating rather than moderating is supported by theoretical differences. Moderating variables alter the magnitude or direction of relationships between predictors and outcomes but do not open the causal channels through which effects flow. On the other hand, conversion factors in capability frameworks are essential intermediate links; the conversion of resources into functionings is not possible without them. Evidence indicates that access to technology without digital skills has little impact on empowerment [2]. This implies that digital literacy is a driver of transformation rather than a reinforcer of practices. This pattern, where the relationship between predictor and outcome becomes ineffective rather than just weaker without the mediator, theoretically evidences mediation rather than moderation. Ref. [1] found evidence for this: having a cell phone did not generate a significant impact on empowerment until it was combined with digital use skills, suggesting that the resource-outcome pathway needs a mediating ability to operate.

Likewise, considering digital literacy as a predictor variable independent of sociodemographic and technological variables would be a conceptual error when establishing its theoretical role in capability frameworks. Sociodemographic characteristics (chronological age, educational level, socioeconomic level) and technological infrastructure are pre-existing structural conditions, external to the individual and existing prior to his or her action. Digital literacy, on the other hand, is learned by actively interacting with these structural conditions. Capability theory posits that skills are transformative mechanisms that channel the influence of structural factors on performance, rather than independent parallel predictors operating in separate causal channels. The mediating specification operationalizes this theoretical-sequential logic: initial structural conditions allow capabilities to develop, and then capabilities transform those conditions into actions [11]. This sequential causal architecture—which separates initial structural conditions, transforming capabilities, and outcomes—distinguishes capability-based mediation models from additive regression models, in which all predictors are conceptually treated as conceptually equivalent and causally simultaneous.

Contemporary digital empowerment frameworks also conceptualize digital literacy as a mediating capability between structural access and empowerment outcomes [6,7]. These theoretical frameworks propose that digital competencies operate through domain-specific channels: cognitive dimensions open the door to accessing and critically evaluating digital information; technical dimensions enable moving on platforms and creating content; communicative dimensions develop networks and participate in the marketplace; and social dimensions foster community participation and collective action [5]. Each of these is a mechanism for transforming structural resources into domain-specific empowerment outcomes. For example, technological infrastructure is a prerequisite for the use of digital platforms, but cognitive digital literacy is what transforms access into market information that leads to economic empowerment. This multi-pathway mediation exemplifies the entangled nature of digital literacy as a skill and empowerment as a process, where particular dimensions of competence activate different outcome domains through theoretically distinct causal mechanisms.

In the specific case of indigenous cotton crafts, digital literacy appropriates culturally native channels that alphabetize with the codes of craft entrepreneurship. Traditional craft knowledge (ancestral forms of cotton cultivation, native plant dyes, pre-Columbian weaving techniques) is a type of human capital specific to a culture. But this knowledge is useless without digital communication skills to reach heritage tourism markets, cultural authenticity certification systems and fair trade networks. Digital devices and mobile internet access are examples of enabling capital. But this infrastructure requires digital marketing skills to monetize through e-commerce channels, social networks and marketplaces. Socio-demographic resources, such as academic qualifications and community social networks, are capital. But these resources need digital networking capabilities to connect with international buyers, craft cooperatives and heritage organizations [31]. The mediating specification defines how latent structural resources lie dormant without domain-specific digital competencies that can activate them in craft contexts, where traditional modes of know-how and contemporary market channels operate through ontologically separate pathways that digital literacy succeeds in linking. This uniqueness demonstrates that conversion factors are highly localized in livelihood systems and that digital literacy enables certain transformations of resources into market functions, which, in the case of cultural heritage, are very different from agricultural or manufacturing ones.

Hypothesis 4.

Digital literacy positively predicts the economic empowerment of indigenous women cotton artisans.

Hypothesis 5.

Digital literacy positively predicts personal empowerment of native cotton craftswomen.

Hypothesis 6.

Digital literacy positively predicts social empowerment of native cotton craftswomen.

2.3. Empirical Evidence for the Mediating Hypotheses

Recent empirical studies confirm the theoretical conceptualization of digital literacy as a transformative agent, albeit with very different methodological approaches. Ref. [8] find longitudinal evidence that digital literacy explains the association between structural interventions and rural poverty reduction outcomes in China, demonstrating that infrastructure improvements operate primarily through digital skills development. Their panel structure confirms temporal anteriority, strengthening causal inference about the mediation pathway. Ref. [6] find that digital financial inclusion, i.e., access to digital payment and credit systems, influences the performance of female-led firms in China, but its cross-sectional nature precludes making definitive causal claims about mediation. Ref. [1] find that cell phone ownership by rural women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh is associated with empowerment, especially when combined with improvements in digital skills. This suggests that skills mediate the association between technology and empowerment, although they did not directly analyze indirect effects using mediation analysis methods. Research analyzing partial mediations provides additional theoretical support. Ref. [28] note that structural factors directly influence economic empowerment and also indirectly through digital capabilities, in line with partial mediation models. Refs. [13,32] find similar results that digital literacy passes structurally but also leaves residual direct channels, i.e., that empowerment operates through multiple simultaneous mechanisms. However, these studies did not employ formal mediation testing methodologies, such as bootstrapped indirect effects, that constrain strong causal inferences. For native cotton artisans, these empirical models point out that digital literacy should be the primary mediating mechanism, converting technological access, sociodemographic resources, and ancestral knowledge into empowering outcomes. This study extends the current literature by formally testing mediating pathways using structural equation modeling with bootstrapped confidence intervals for indirect effects, providing stronger evidence for the suggested conversion mechanism. Table 1 summarizes the nine hypotheses, their proposed relationships theoretical foundations, and supporting empirical evidence. Table 2 presents the conceptual model of mediation, illustrating the relationships among predictors, the mediating variable, and empowerment outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of hypotheses and theoretical underpinnings.

Table 2.

Conceptual model of mediation.

Hypothesis 7.

Digital literacy significantly mediates the relationship between technological factors and dimensions of empowerment (economic, personal, and social) of Native cotton artisan women.

Hypothesis 8.

Digital literacy significantly mediates the relationship between sociodemographic factors and empowerment dimensions (economic, personal and social) of native cotton craftswomen.

Hypothesis 9.

Digital literacy significantly mediates the relationship between sociocultural factors and dimensions of empowerment (economic, personal and social) of native cotton women artisans.

2.4. Hypotheses of the Model

- Direct hypotheses (H1–H3): Predictors → Digital literacy.

- Direct hypotheses (H4–H6): Digital literacy → Dimensions of empowerment.

- Mediation hypotheses (H7–H9): Predictors → Digital literacy → Empowerment (economic, personal, social).

Note. The conceptual model integrates Sen’s capabilities approach with contemporary sociotechnical perspectives, conceptualizing digital literacy as a conversion factor that mediates the transformation of structural resources into multidimensional empowerment outcomes.

3. Materials and Methods

A quantitative, explanatory, cross-sectional, design using structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to explore the mediating role of digital literacy in the relationship between predictor variables and empowerment outcomes in native craftswomen cotton producers. The methodological design made it possible to examine causal relationships among several latent variables, providing empirical evidence to theorize about digital empowerment processes in rural areas.

3.1. Research Design

The study employed a non-experimental cross-sectional design, appropriate for simultaneously estimating direct and indirect effects in complex theoretical models. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used for its ability to assess latent constructs, estimate measurement errors through confirmatory factor analysis, and test multiple regression equations simultaneously [42]. While its cross-sectional design restricts causal inferences, it is well suited to reveal complex associations between variables at a specific point in time, consistent with the exploratory goal of examining culturally situated digital empowerment. Such a design made it possible to analyze potential mediation pathways between exogenous predictors, digital literacy (mediating variable), and multidimensional empowerment outcomes.

The PLS-SEM approach was chosen over CB-SEM for three methodological reasons: first, the exploratory nature of the model, which is more prediction-oriented in contexts with limited prior theory [43]; second, the sample size (n = 100), which is appropriate for PLS-SEM use in small to moderate samples [42]; and third, its robustness to violations of multivariate normality, which is common in specialized craft populations [44].

3.2. Context and Study Population

The research was conducted in the district of Mórrope, Lambayeque Region, northern Peru, a rural territory internationally recognized for the ancestral cultivation of native cotton (Gossypium barbadense) and traditional textile handicraft production. This district constitutes one of the few surviving centers in the Americas where pre-Columbian cotton varieties continue to be cultivated and processed using traditional methods, representing living cultural heritage currently under consideration for UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage recognition [20]. The convergence of ancestral knowledge systems, artisanal production modes, and contemporary digital market opportunities renders Mórrope a theoretically significant case for examining technology-mediated empowerment processes—a phenomenon that cannot be adequately studied in general rural populations or conventional agricultural settings lacking this unique cultural-economic intersection.

Women’s access to digital technology, which is key to working in agrifood systems, continues to lag behind men’s, with rural women particularly disadvantaged due to constraints such as affordability, illiteracy, user capabilities, and discriminatory social norms [45]. In low- and middle-income countries, women are 13 percent less likely than men to own a smartphone, representing 200 million fewer women than men with smartphone ownership [46]. This persistent digital gender gap underscores the importance of examining how digital literacy mediates empowerment outcomes among marginalized populations, particularly rural women engaged in traditional economic activities.

The study population comprised the complete universe of 325 registered indigenous women artisans actively engaged in native cotton textile production within the district, identified through the membership registry of the Asociación de Artesanas de Algodón Nativo de Mórrope and cross-referenced with municipal community cadasters. This finite population represents the totality of women practitioners of this heritage craft within the defined geographic boundaries—not an arbitrary selection but the complete identifiable population meeting established eligibility criteria. Eligibility requirements included (a) minimum two years of demonstrable experience in native cotton handicraft production; (b) permanent residence within district boundaries; and (c) active, ongoing participation in traditional cultivation and textile production processes. These criteria ensured participants maintained substantive engagement with both cultural and economic dimensions of native cotton craftsmanship, excluding occasional or peripheral involvement.

3.3. Sampling and Sample Size

A simple random sample was drawn from the census population to ensure representativeness and minimize selection bias. Sample size determination followed conventional statistical criteria: 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), 5% margin of error, and estimated population proportion of 0.50 (maximum variance assumption), yielding a calculated minimum sample of 98 participants, rounded to n = 100 for analytical convenience. The achieved sample represents 30.8% of the total registered artisan population, providing substantial coverage of the target universe.

The sample size satisfies established requirements for partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). According to [43], the minimum sample size for PLS-SEM should equal 10 times the largest number of structural paths directed at any single construct in the model. In our structural specification, digital literacy—the most connected construct—receives three incoming paths from predictor variables (technological, sociodemographic, and sociocultural factors), requiring a minimum of 30 cases. Our sample of 100 substantially exceeds this threshold by a factor of 3.3, providing adequate statistical power for parameter estimation, model fit assessment, and reliable detection of medium effect sizes (f2 ≥ 0.15) at α = 0.05. As the model is moderately complex (three exogenous constructs, one mediating variable, and three endogenous dimensions), the sample provided sufficient statistical power to accurately estimate parameters and evaluate model fit [42].

3.4. Measurement Instrument

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire with 45 items created for this study, with the objective of measuring digital literacy and empowerment characteristics in the context of indigenous cotton handicraft, as there was no previously validated scale for this culturally specific population. All items used five-point Likert scales (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). Three types of exogenous predictors were identified in the questionnaire: sociodemographic (age, educational level, marital status, family composition, years of experience); technological (access to devices, quality of Internet connection, frequency of use, availability of devices in the home); and knowledge (traditional knowledge of cotton cultivation, experience in craft techniques, participation in training programs and integration of ancestral knowledge with current practices).

Digital literacy as a mediating variable was evaluated in three dimensions adapted to the handicraft contexts: access to and use of digital technologies to promote and sell handicrafts; online digital communication skills (social networks, online sales platforms); and information skills (search, evaluation and use of information on markets, techniques and business opportunities in the native language).

Endogenous empowerment was implemented through three dimensions associated with indigenous cotton crafts: economic (income generation, resource control, market access, autonomy in financial decisions); personal (autonomy in craft decisions, self-efficacy in craft skills, confidence in production, decision-making authority in the production chain); and social (community participation in crafts, networking of cotton artisans, recognition of indigenous cotton crafts, participation in collective decisions).

3.5. Validation of the Instrument

The questionnaire underwent content validation to ensure validity and reliability following established methodological procedures. Content validity was assessed by a panel of five experts (university professors and professionals with experience in rural development, gender studies, and traditional crafts). Each item was rated on importance, clarity, cultural appropriateness, and coherence with the theoretical construct, achieving an Aiken’s V coefficient of 0.86, demonstrating high consensus that items were important and representative of the construct. Additionally, pilot tests were conducted with 30 local cotton artisans, excluded from the final sample, to confirm item comprehension, response dispersion, administration time, and contextual relevance. Initial reliability analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82, indicating adequate internal consistency according to established thresholds [43]. Following expert panel recommendations and pilot test feedback, modifications were implemented to simplify terminology and confusing language into forms easily understood by artisans, items were reordered to improve flow, redundant items were eliminated, and sections addressing digital literacy application to cotton commerce and economic activities were strengthened.

3.6. Data Collection Procedure

Data collection team. Data were collected by a field team comprising workers from the Mórrope District Municipality with experience in rural community work and knowledge of local cultural protocols. This team facilitated access to communities and the establishment of trust with participating artisans.

Timing and scheduling. Data collection was conducted between December 2024 and March 2025, scheduled to coincide with periods when artisans had greater availability for research participation. Each questionnaire administration required approximately 30 min with assistance from the support team.

Participant selection and location. Participants were selected through simple random sampling from the census list of 325 registered artisans. The field team traveled directly to the district’s hamlets, visiting artisans at their workshops. The highest concentration of participants was located in the Arbolsol hamlet, where the majority of native cotton artisans in the district are found. Other hamlets with active artisan presence were also visited. The response rate was 100%, as all selected participants agreed to participate in the study.

Administration procedures. Questionnaires were administered face-to-face at participants’ artisan workshops, respecting their usual work environment. Prior to questionnaire distribution, each participant was informed about the study’s purpose, their voluntary participation, the confidentiality of their responses, and the potential benefits for the community. Informed consent was obtained following culturally sensitive protocols for the indigenous population. To preserve confidentiality, data were coded to maintain privacy and follow cultural norms.

Quality control. All completed questionnaires were reviewed for completeness and consistency. Data were handled following established procedures to ensure accuracy and reliability.

3.7. Data Analysis Strategy

Data analysis was carried out in sequential stages. First, initial procedures were performed to verify the integrity of the questionnaires, identify and deal with outliers (using standardized residuals), and assess univariate and multivariate normality. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, measures of central tendency and dispersion, were used to describe sample demographics, technology access patterns and craft-specific indicators. Construct reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability coefficients, and convergent validity was analyzed using average variance extracted (AVE) and discriminant validity according to the Fornell-Larcker criterion. According to [43], in exploratory research in specific cultural settings, items with factor loadings between 0.60 and 0.70 were retained when their elimination did not partially improve composite reliability or AVE (average variance extracted). This choice was justified by the exploratory nature of the research, the theoretical and practical relevance of retaining items that best represented the essential dimensions of traditional craft contexts, and for achieving adequate overall reliability (CR > 0.70) and acceptable convergent validity (AVE > 0.50), while maintaining good psychometric properties.

Discriminant validity was further assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT), following contemporary methodological recommendations [43]. HTMT values below the threshold of 0.85 were established as the criterion to confirm adequate discriminant validity.

The model was fitted using the standardized root mean residual (SRMR), which calculates the average difference between observed and model-estimated correlations; the normalized fit index (NFI) and comparative fit index (CFI), which contrast the hypothesized model with a null model; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which penalizes model complexity, giving a measure of the overall fit of the model to the data. Mediation effects were tested using bootstrapping with a bias correction of 5000 resamples, a robust method that creates empirical confidence intervals for indirect effects without assuming particular distributions. This is the suggested approach for mediation analysis in SEM [43], as it provides reliable estimates of the indirect paths through which predictors influence empowerment through digital literacy.

3.8. Ethical Considerations

Prior to data collection, participants were informed in detail about the objectives of the study, the scope of the research, the potential benefits to the community, and their right to participate or withdraw at any time. The identity and confidentiality of the participants were maintained through anonymous coding, following conventional protocols on knowledge related to cotton cultivation. The research followed the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence in order to do no harm and contribute to the social and economic development of the community. All materials were linguistically and culturally adapted to ensure their relevance and local understanding. The research protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee and followed ethical guidelines for social research with indigenous and traditional communities, respecting cultural diversity, community autonomy and protection of conventional ecological knowledge. Data were securely archived according to standardized protocols, paying special attention to culturally sensitive information on traditional ways of growing and processing cotton.

4. Results

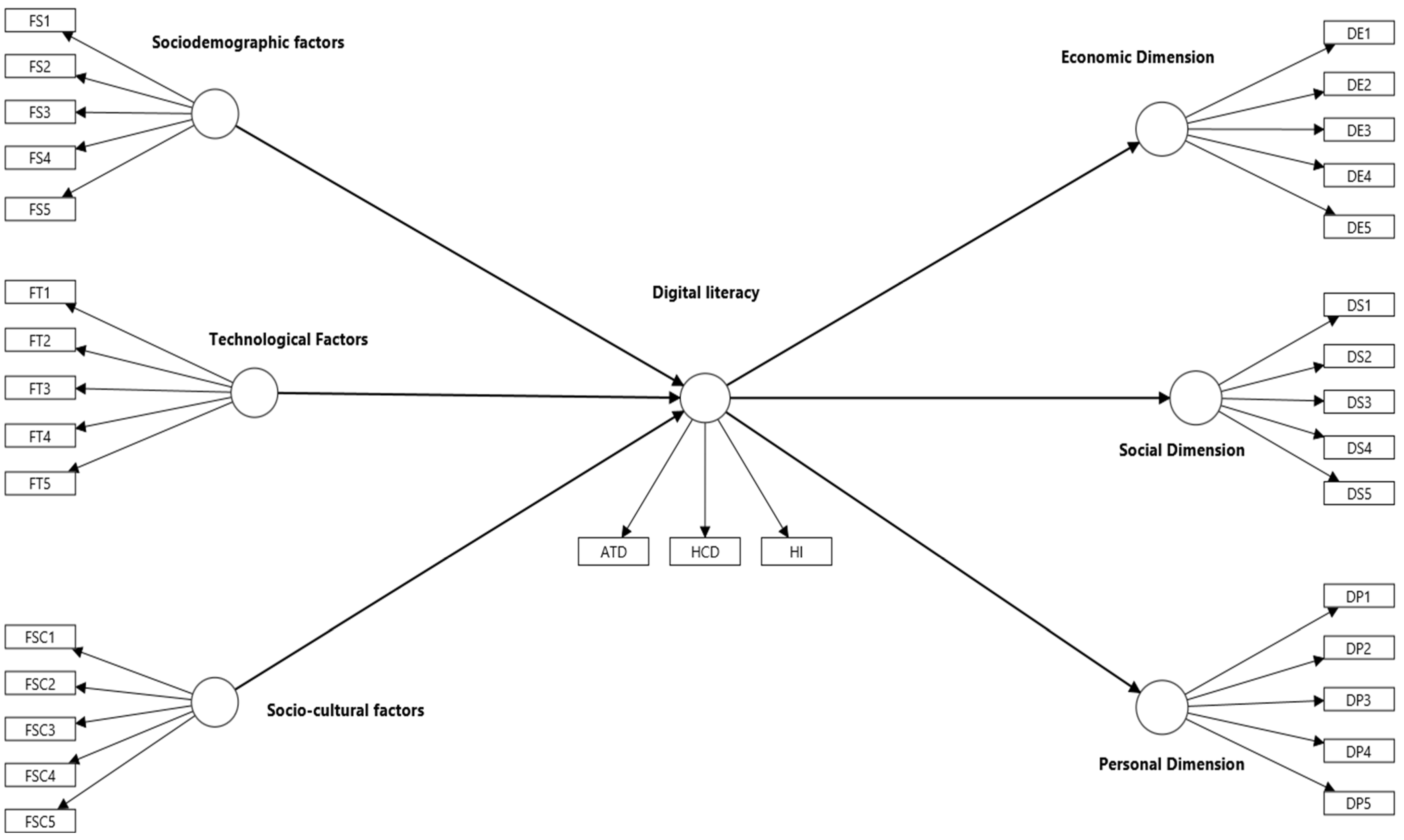

The partial least squares method (PLS-SEM) and SmartPLS 4.0 software were applied to model structural equations. The model was composed of seven latent variables measured by 45 indicators: three exogenous predictor variables (sociodemographic, technological and sociocultural), one mediating variable (digital literacy) and three endogenous empowerment variables (economic, personal and social). The analysis was carried out in two stages: first the measurement model was tested, and then the structural relationships were analyzed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model.

4.1. Preliminary Data Analysis

Before estimating the structural model, a thorough preliminary analysis of the data was performed. The sample (n = 100) had a mean age of 42.3 years (SD = 8.7), with 67% of the participants having completed primary education and 78% being married. In terms of access to technology, 89% owned a cell phone and 34% had regular access to the Internet. Univariate normality assessment using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests showed significant deviations in several items (p < 0.05), confirming the suitability of PLS-SEM as an estimation method. Missing values were minimal (<2% per variable) and were managed by listwise elimination. The detection of multivariate outliers using the Mahalanobis distance (p < 0.001) identified three extreme cases that were retained after verifying their empirical legitimacy and representativeness of the craft context.

4.2. Evaluation of Model Fit

The structural model demonstrated an adequate fit according to the criteria established for the PLS-SEM evaluation. As shown in Table 3, all fit indices met or exceeded the recommended thresholds, and both estimated and saturated models performed within acceptable ranges. The consistency between the estimated and saturated indices confirmed the suitability of the structural model for hypothesis testing.

Table 3.

Model fit indices.

4.3. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

The confirmatory factor analysis revealed satisfactory psychometric properties in all constructs. The results presented in Table 4 show the external loadings of the items composing each construct of the measurement model. The analysis reveals that most of the factor loadings exceed the recommended minimum threshold of 0.70 [43], indicating adequate convergent validity and a strong relationship between the indicators and their respective latent constructs.

Table 4.

Factor loadings of the measurement model.

Discriminant validity was confirmed through the heterotrait-monotrait criterion (HTMT). All constructs achieved HTMT values below the 0.85 threshold, confirming adequate discriminant validity: digital literacy (0.73), economic empowerment (0.68), personal empowerment (0.71), social empowerment (0.66), sociocultural factors (0.74), sociodemographic factors (0.69), and technological factors (0.72).

Table 5 shows that all constructs achieved adequate internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients above the threshold of 0.70. Convergent validity was confirmed by the mean extracted variance (MEV) values, with six of the seven constructs exceeding the 0.50 criterion. The sociocultural factors construct approached the threshold with an SMV of 0.503. The factor loadings of all indicators exceeded 0.60, demonstrating an adequate relationship between the items and the construct.

Table 5.

Assessment of the reliability and validity of the measurement model.

Table 6 presents the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for assessing multicollinearity among the constructs of the structural model, where all values range between 1.000 and 1.746, satisfactorily meeting the established criterion that VIF values should be between 1 and 3 to ensure the absence of multicollinearity problems. The relationships in which digital literacy acts as a predictor variable have VIF values of 1.000, showing a total absence of multicollinearity, while the factors predicting digital literacy show slightly higher values, but within the acceptable range: sociocultural factor (1.746), Sociodemographic Factor (1.732) and Technological Factors (1.455), confirming that there is no problematic multicollinearity among the predictor variables and validating the statistical robustness of the structural model.

Table 6.

Multicollinearity indicators.

4.4. Results of the Structural Model

4.4.1. Predictors of Digital Literacy

The three exogenous factors jointly explained 80.4% of the variance in digital literacy (R2 = 0.804, adjusted R2 = 0.797), indicating substantial predictive power. Table 7 presents the direct effects within the structural model. Technological factors showed the strongest predictive relationship with digital literacy, reflecting a large effect size. Sociodemographic and sociocultural factors contributed less substantially, although both were statistically significant and were classified as small effects according to Cohen’s criteria.

4.4.2. Effects of Digital Literacy on Empowerment

Digital literacy showed significant positive relationships with all three dimensions of empowerment, although the magnitude of influence varied. The economic dimension showed the strongest association, characterized by a large effect size. The personal and social dimensions showed medium to large effects, with comparable magnitudes in both.

Table 7.

Standardized coefficients and effect sizes of the structural model.

Table 7.

Standardized coefficients and effect sizes of the structural model.

| Path | b | t-Value | p-Value | f2 | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors → Digital literacy | |||||

| Technological factors → Digital literacy | 0.615 | 7.505 | <0.001 | 0.904 | Large |

| Sociodemographic factors → Digital literacy. | 0.219 | 3.053 | 0.002 | 0.129 | Small |

| Sociocultural factors → Digital literacy. | 0.184 | 3.345 | 0.001 | 0.131 | Small |

| Digital literacy → Empowerment dimensions. | |||||

| Digital literacy → Economic dimension | 0.846 | 36.710 | <0.001 | 2.432 | Large |

| Digital literacy → Personal dimension | 0.618 | 11.617 | <0.001 | 0.594 | Medium-large |

| Digital literacy → Social dimension | 0.628 | 9.262 | <0.001 | 0.587 | Medium-Large |

4.5. Variance Explained in the Dimensions of Empowerment

4.5.1. Direct Effects on the Structural Model

Table 8 presents the standardized path coefficients (β) derived from the structural equation analysis using PLS-SEM, which show the direct causal relationships between the constructs of the proposed theoretical model. The results reveal that technological factors have the strongest predictive effect on digital literacy (β = 0.615, p < 0.001), classified as a large effect according to Cohen’s criteria (f2 = 0.904), followed by statistically significant but smaller contributions from sociodemographic (β = 0.219, p = 0.002) and sociocultural (β = 0.184, p = 0.001) factors, both categorized as small effects. Regarding the effects of digital literacy on the dimensions of empowerment, we observe a predominant influence on the economic dimension (β = 0.846, p < 0.001, f2 = 2.432), characterized by an exceptionally large effect size, while the personal and social dimensions show comparable and statistically robust effects (β = 0.618 and β = 0.628, respectively, both p < 0.001) with effect sizes classified as medium to large, confirming the empirical validity of the theoretical hypotheses formulated and the differential relevance of digital literacy as a mediator in the multidimensional processes of empowerment of native cotton artisans.

Digital literacy explained varying proportions of the variance in the empowerment dimensions. The economic dimension showed the greatest explanatory power (R2 = 0.709), indicating that digital literacy explained approximately 71% of its variance. In contrast, the personal and social dimensions showed more modest explanatory coefficients (R2 = 0.373 and R2 = 0.370, respectively), suggesting that factors other than digital literacy contribute to these aspects of empowerment.

4.5.2. Mediation Analysis

A comprehensive mediation analysis revealed significant indirect pathways through digital literacy for all combinations of predictors and outcomes, as presented in Table 8. The technology pathway consistently demonstrated the strongest mediation effects across all dimensions of empowerment. The sociodemographic and sociocultural pathways showed smaller, but statistically significant, indirect effects with confidence intervals excluding zero for all relationships analyzed.

A consistent pattern was observed across all mediation pathways, with economic empowerment consistently receiving the most significant spillover effects, followed by comparable effects in the social and personal dimensions. Bootstrap confidence intervals confirmed the statistical significance of all indirect effects, providing strong evidence of the mediating role of digital literacy.

Table 8.

Indirect effects through the mediation of digital literacy.

Table 8.

Indirect effects through the mediation of digital literacy.

| Mediation Pathway | b | p-Value | Lower 95% CI | 95% Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological factors → Digital literacy → Empowerment | ||||

| Technology → DL → Economics | 0.521 | <0.001 | 0.442 | 0.598 |

| Technology → DL → Social | 0.385 | <0.001 | 0.298 | 0.471 |

| Technology → DL → Personal | 0.381 | <0.001 | 0.294 | 0.467 |

| Sociodemographic factors → Digital literacy → Empowerment | ||||

| Socio → DL → Economic | 0.185 | 0.002 | 0.068 | 0.302 |

| Socio → DL → Social | 0.139 | 0.010 | 0.034 | 0.244 |

| Partner → DL → Personal | 0.135 | 0.003 | 0.047 | 0.223 |

| Socio-cultural factors → Digital literacy → Empowerment | ||||

| Education → DL → Economic | 0.156 | 0.001 | 0.066 | 0.246 |

| Cultivated → DL → Social | 0.117 | 0.004 | 0.037 | 0.197 |

| Cultivated → DL → Personal | 0.114 | 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.183 |

Note. DL = Digital literacy; CI = Confidence interval based on a bias-corrected bootstrap (5000 resamples).

4.5.3. Summary of Main Findings

Structural equation modeling supported the hypothesized mediation model in which digital literacy was a significant mediator between all types of predictors and dimensions of empowerment. Technological reasons were the main cause of digital literacy development, with the largest contribution to the variance explained. Digital literacy was present as a factor influencing all dimensions of empowerment, with economic empowerment having the highest coefficient ratio. All direct and indirect paths supported the empirical validity of the theoretical model in this sample of participating Native cotton artisan women participants.

5. Discussion

This study examined the mediating role of digital literacy among structural predictors and multidimensional outcomes of empowerment among native women cotton artisans in Mórrope, Peru. Structural equation modeling provided strong support for the nine hypotheses, demonstrating that digital literacy functions as an important conversion mechanism that transforms technological, socio-demographic and socio-cultural resources into economic, personal and social empowerment.

5.1. Digital Literacy as a Central Mediating Mechanism

The structural equation model explained 80.4% of the variance in digital literacy, indicating a high predictive ability of the structural factors. Ref. [1] recorded empowerment progress among rural women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh, and ref. [8] found that digital literacy was a predictor of poverty decline, but these studies focused on direct associations rather than defined mediating pathways. Our results enrich the existing literature by showing that digital literacy is a conversion mechanism that consistently converts structural resources into empowering outcomes.

This explanatory power points to craft contexts with consolidated markets and cultural significance as settings that favor the development of digital skills that go beyond information access. These findings expand Sen’s framework in demonstrating how conversion factors operate in distinct livelihood systems. In artisanal entrepreneurship, digital literacy enables entry into heritage markets and promotion of cultural products, evidencing inequalities in empowerment pathways between cultural production and product-agricultural systems.

5.2. Technological Infrastructure as a Major Determinant

Technological factors were the best predictors (β = 0.615, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.904), in contrast to the meta-analysis of [37], where educational level was the best predictor in different contexts. This difference is probably due to the environment: our craft sample operates in established heritage markets where infrastructure problems may be more determinant than educational differences, once basic literacy levels are exceeded. This finding supports [33] evidence on technology ecosystems as critical entry points and extends [36] recommendation to invest in digital infrastructure.

The results also enrich [47] notion that digital exclusion is a vicious cycle. Our results suggest that the provision of specific infrastructure can interrupt these cycles in contexts with pre-existing social capital and market opportunities, but that infrastructure alone is insufficient to overcome educational and socio-cultural barriers. Sociodemographic (β = 0.219) and sociocultural (β = 0.184) factors were significant, but with less impact, acting more as facilitators than determinants in the presence of sufficient infrastructure.

5.3. Differential Results in Empowerment

Digital literacy was a significant predictor of economic empowerment (β = 0.846, R2 = 0.709, f2 = 2.432). Ref. [6] found that digital financial inclusion explained 52% of the variance in female entrepreneurship, while ref. [7] reported 48% for economic bargaining power; however, direct comparisons should be taken with caution due to differences in the constructs. Digital financial inclusion is access to transactions, and our metric measures a broader set of skills directly relevant to craft marketing. The greater impact is likely due to how niche the metrics are and how well digital marketing skills fit with traditional craft sales [48].

On the other hand, digital literacy had a medium influence on personal (β = 0.618, R2 = 0.373) and social empowerment (β = 0.628, R2 = 0.370). The reduction in explained variance implies that digital competencies alone are not sufficient for psychological and relational empowerment in contexts with consolidated patriarchal structures. These findings are consistent with those of [15]), who found that access to technology has little effect on self-efficacy when there are unquestioned patriarchal norms, and build on the findings of [2] on male control of technology as a barrier to empowerment. The results challenge techno-optimist views by revealing that digital literacy can facilitate economic transactions without changing underlying power relations, which is consistent with [28] assertion that empowerment needs simultaneous advances in individual agency, supportive policies, and structural reforms.

5.4. Mediation and Partial Mediation Pathways

Digital literacy largely mediated all relationships, and technological factors showed the strongest indirect effects (economic β = 0.521; social β = 0.385; personal β = 0.381). Mediation was partial, as sociodemographic and sociocultural factors continued to have direct effects (β = 0.114 to 0.185) along with indirect pathways, consistent with frameworks that theorize empowerment as a multiple pathway [13,32]. This model builds on [8] evidence that digital literacy reduces poverty, showing that mediating mechanisms go beyond economic outcomes to encompass empowerment in many aspects. Partial mediation challenges linear models of ownership and shows that successful interventions should not only focus on digital literacy but also simultaneously work on the direct routes by which structural resources impact empowerment.

5.5. Contextual Specificity and Theoretical Contributions

This research expands Sen’s capabilities view by showing how it can be applied to the agency between indigenous knowledge and digital technologies. The findings confirm [31] conceptualization of digital inclusion as knowledge hybridization by quantitatively demonstrating that combining traditional expertise with digital skills generates empowerment if sufficient infrastructure is in place. Indigenous artisanal entrepreneurship is distinguished from agricultural contexts by established traditional markets, premiums for cultural authenticity, and differentiated positioning strategies. Highly significant economic effects (f2 = 2.432) suggest that local market conditions may be more determinant than mechanisms applicable to all rural livelihoods.

Morrope’s infrastructure is half-baked: it has connectivity, but few devices. This makes it different from more neglected areas. The main technological factor is evidence that infrastructure improvements can generate significant impacts on development levels in places with elementary connectivity, but access is still restricted. This enriches the digital divide frameworks, showing that transformation mechanisms operate differently in different types of infrastructure.

5.6. Critical Tensions and Theoretical Implications

The differential effect on economic empowerment (R2 = 0.709) versus the personal and social dimensions (R2 ≈ 0.37) evidences problems of digital inclusion. Digital literacy enables market inclusion but also generates commoditization pressures that can erode cultural authenticity. As ref. [31] point out, platforms tend to prioritize commercial over cultural ends, and ref. [2] warn that technological benefits can widen inequalities. Digital platforms have their risks, such as the intensification of production to the detriment of traditional forms, stereotypical marketing strategies and dependence on third-party intermediaries that take away your autonomy.

This paper brings three theoretical improvements to Sen’s framework. First, it illustrates that conversion factors are not the same for all types of work. For example, digital literacy is more influential on economic development in craft contexts because it is more in line with the market form in which heritage moves. Second, partial mediation models challenge linear models, showing that conversion and structural factors operate simultaneously on parallel pathways. Third, differentiated impacts across dimensions lend numerical support to the theory of intersectional empowerment, demonstrating how patriarchal frameworks constrain individual and societal outcomes, despite the development of capabilities.

5.7. Policy Implications

The empirical findings of this study generate specific, evidence-based policy recommendations grounded in the observed effect sizes and explanatory patterns. The dominant influence of technological factors on digital literacy development (β = 0.615, f2 = 0.904) indicates that infrastructure investment should constitute the primary policy priority in contexts where connectivity and device access remain limited. This finding suggests that, within communities possessing pre-existing social capital and established market opportunities like Mórrope’s artisan networks, targeted infrastructure provision can initiate virtuous cycles of digital skill development and empowerment—effectively interrupting the self-perpetuating patterns of digital exclusion documented by Ref. [48] and van Dijk (2020) [49].

However, the partial mediation patterns observed—wherein sociodemographic (β = 0.219) and sociocultural (β = 0.184) factors maintained significant direct effects on empowerment alongside digitally mediated pathways—caution against exclusively skills-focused interventions. Effective programming must simultaneously address the direct channels through which education, traditional knowledge, and social positioning influence empowerment outcomes. This implies integrated approaches combining (a) connectivity infrastructure expansion; (b) device accessibility programs; (c) culturally adapted digital skills training; (d) technical support systems; and (e) locally relevant content development—rather than isolated skills training divorced from broader structural interventions.

The substantially greater explained variance in economic empowerment (R2 = 0.709) compared to personal and social dimensions (R2 ≈ 0.37) generates important policy implications regarding the scope and limitations of digital inclusion initiatives. While digital literacy demonstrably enables market participation and income generation, its limited impact on psychological autonomy and community power relations suggests that digital interventions cannot substitute for direct engagement with patriarchal structures constraining women’s agency within households and communities. Closing the gender gap in farm productivity and the wage gap in agrifood systems would increase global gross domestic product by nearly USD 1 trillion [45], underscoring the economic rationale for gender-transformative approaches. Policy frameworks should therefore combine digital empowerment programming with complementary strategies addressing gender norms and community hierarchies [28].

The exceptionally large effect of digital literacy on economic empowerment (f2 = 2.432) simultaneously justifies prioritization of digital marketing platforms while signaling potential risks requiring policy attention. Market integration through digital channels creates commodification pressures that may erode the cultural authenticity constituting the distinctive value proposition of indigenous crafts. Policy responses should include artisan-controlled certification systems protecting cultural authenticity claims, intellectual property protections for traditional knowledge and designs, fair trade certification facilitating market access while ensuring equitable value distribution, and cooperative governance structures enabling collective negotiation with digital platforms and intermediaries [31]. These protective mechanisms should accompany rather than replace digital inclusion efforts, recognizing that market access and cultural preservation require coordinated rather than sequential policy attention.

5.8. Limitations and Future Research

The cross-sectional design does not allow causality to be inferred even with directional hypotheses; reverse causality is always an alternative explanation. Longitudinal panel designs would improve inference by establishing temporal priority. Restricting the sample to a single district with intermediate infrastructure and markets restricts generalization. Comparison across contexts would reveal universal mechanisms on which specific ones depend. Low explained variance in personal and social empowerment (R2 ≈ 0.37) indicates the existence of unmeasured variables; future studies should explore community social capital, household dynamics, and institutional contexts. Self-reported measures may be affected by social desirability bias; objective indicators and mixed-methods designs may provide a more complete perspective. Finally, this research did not systematically address the negative effects of digital market integration, such as the cultural commodification and extractivist relations of platforms, which deserve to be studied with qualitative methods.

6. Conclusions

This study empirically demonstrated that digital literacy functions as a mediating mechanism converting technological, sociodemographic, and sociocultural resources into economic, personal, and social empowerment among indigenous cotton artisans in northern Peru. Structural equation modeling revealed that technological infrastructure constitutes the primary determinant of digital literacy development (β = 0.615, f2 = 0.904), while digital competencies exert substantially greater influence on economic empowerment (R2 = 0.709) than on personal or social dimensions (R2 ≈ 0.37). These differential effects indicate that digital skills facilitate market integration without necessarily transforming the patriarchal structures constraining domestic authority and community participation.

The partial mediation patterns identified challenge linear technology adoption models by demonstrating that structural resources influence empowerment through multiple concurrent pathways, not solely through digital literacy acquisition. This complexity implies that interventions cannot rely exclusively on skills training but must simultaneously address direct channels through which education, infrastructure, and traditional knowledge affect empowerment outcomes independent of digital competencies. Within indigenous artisanal contexts, digital literacy enables heritage craft marketing through contemporary channels while simultaneously generating tensions between economic opportunity and cultural authenticity that communities must strategically navigate.

The findings contribute to capability-based theoretical frameworks by empirically demonstrating that conversion factors operate differentially across livelihood systems and empowerment dimensions. Digital literacy’s substantial economic impact reflects alignment between marketing competencies and heritage product commercialization strategies—a pattern likely differing in agricultural contexts where digital applications primarily support information access rather than direct market participation. This livelihood-specific variation suggests capability frameworks require contextual adaptation rather than universal application.

Policy implications emphasize infrastructure investment prioritization in underserved regions while recognizing connectivity alone as insufficient. Effective interventions require integrated approaches combining infrastructure development with culturally appropriate skills training, institutional support for artisanal cooperatives, protection against cultural commodification, and complementary strategies addressing gender barriers to technology access. The limited impact on personal and social empowerment underscores the critical need for simultaneous interventions addressing patriarchal norms within households and communities. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to establish temporal precedence, investigate potential adverse effects of digital market integration through qualitative methods, and conduct comparative studies across diverse contexts to delineate boundary conditions of the identified mechanisms.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee (protocol code 2024-UIET-IIICyT-ITCA 0002-2024-GM-UIET-IIICyT and 1 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions concerning indigenous community participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rahman, M.S.; Haque, M.E.; Afrad, M.S.I.; Hasan, S.S.; Rahman, M.A. Impact of Mobile Phone Usage on Empowerment of Rural Women Entrepreneurs: Evidence from Rural Bangladesh. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, K.H.; Baird, T.D.; Woodhouse, E.; Christie, M.E.; McCabe, J.T.; Terta, F.; Peter, N. Mobile Phones and Women’s Empowerment in Maasai Communities: How Men Shape Women’s Social Relations and Access to Phones. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindakis, S.; Showkat, G. The Digital Revolution in India: Bridging the Gap in Rural Technology Adoption. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chang, K. Mobile Immobility: An Exploratory Study of Rural Women’s Engagement with e-Commerce Livestreaming in China. J. Chin. Sociol. 2024, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzard, V. Economic Empowerment of Iranian Women through the Internet. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Gao, M. Can Digital Financial Inclusion Promote Female Entrepreneurship? Evidence and Mechanisms. North Am. J. Econ. Finance 2022, 63, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-W. Online Banking and Women’s Increasing Bargaining Power in Marriage: A Case Study in a ‘Taobao Village’ of Southern Fujian. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2022, 92, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zha, F.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, X. Does Digital Literacy Reduce the Risk of Returning to Poverty? Evidence from China. Telecommun. Policy 2024, 48, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindra, I.G.; Pahlevi, S.M.; Susenna, A.; Agustina, L.; Kusumasari, D.; Sukma, Y.A.A.; Hernikawati, D.; Rahmi, A.A.; Pravitasari, A.A.; Kristiani, F. Framework for Monitoring the Spatiotemporal Distribution and Clustering of the Digital Society Index of Indonesia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornel-Vázquez, R.; Iglesias, E.; Loureiro, M. Adoption of Clean Energy Cooking Technologies in Rural Households: The Role of Women. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2024, 29, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.G.; McAdam, M. Scaffolding Liminality: The Lived Experience of Women Entrepreneurs in Digital Spaces. Technovation 2022, 118, 102537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongo, B.; Ondoua, B.; Ngo, J.F.; Ngnouwal, G. Does Social Media Improve Women’s Political Empowerment in Africa? Telecommun. Policy 2023, 47, 102624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Nisar, Q.A.; Koondhar, M.A.; Meo, M.S.; Rong, K. Analyzing the Women’s Empowerment and Food Security Nexus in Rural Areas of Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Pakistan: By Giving Consideration to Sense of Land Entitlement and Infrastructural Facilities. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass-Hanna, J.; Lyons, A.C.; Liu, F. Building Financial Resilience through Financial and Digital Literacy in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2022, 51, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Tasmin, M.; Nasim, S.M. Technology for Empowerment: Context of Urban Afghan Women. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.; Fu, X.; Minayora, A. Digital Technology-Based Entrepreneurial Pursuit of the Marginalised Communities. J. Int. Manag. 2022, 28, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgomezulu, W.R.; Dar, J.A.; Maonga, B.B. Gendered Differences in Household Engagement in Non-Farm Business Operations and Implications on Household Welfare: A Case of Rural and Urban Malawi. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.; Sarkki, S.; Fransala, J.; Murtagh, A.; Weir, L.; Ahl, H.; Lépy, É.; Heikkinen, H.I. Empowering Women-Led Innovations: Key Players In Realising The Long-Term Vision For Rural Areas. Eur. Countrys. 2024, 16, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, M.; Purwar, T.; Shah, R.; Vizcaino, M.; Castillo, L. Empowerment and Integration of Refugee Women: A Transdisciplinary Approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Empowering Women Through Digital Literacy: IFAP’s Impact Across. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/empowering-women-through-digital-literacy-ifaps-impact-across-marginalized-communities (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- INEI Las Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en los Hogares: Abr-May-Jun 2023. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/es/institucion/inei/informes-publicaciones/4687921-information-and-communication-technologies-in-households-apr-may-jun-2023 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Algül, Y. Assessing the Relationship between Broad Gender Inequality and the Gender Unemployment Gap: Insights from an Extensive Global Macroeconometric Panel Analysis. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, N.; Yurco, K. Beyond the ‘Gender Gap’ in Agriculture: Africa’s Green Revolution and Gendered Rural Transformation in Rwanda. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 112, 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shupler, M.; Karl, J.; O’Keefe, M.; Hoka Osiolo, H.; Perros, T.; Nabukwangwa Simiyu, W.; Gohole, A.; Lorenzetti, F.; Puzzolo, E.; Mwitari, J.; et al. Gendered Financial & Nutritional Benefits from Access to Pay-as-You-Go LPG for Cooking in an Informal Settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. World Dev. Sustain. 2024, 5, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhao, M.; Chen, H. Effects of the Three-Child Policy on the Employment Bias against Professional Women: Evidence from 260 Enterprises in Jiangxi Province. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornginnaya, S. Chapter 7—Asian Cooperatives and Gender Equality. In Waking the Asian Pacific Co-Operative Potential; Altman, M., Jensen, A., Kurimoto, A., Tulus, R., Dongre, Y., Jang, S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 71–88. ISBN 978-0-12-816666-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Dev. Change 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, S.; Gera, N.; Dana, L.-P. Antecedents of Economic Empowerment: An Empirical Study of Working Women in Delhi-NCR. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 38, 784–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.K.; Prasad, R.; Behera, S. Chapter 2—Rural Women’s Health Disparities, Hunger, and Poverty. In Healthcare Strategies and Planning for Social Inclusion and Development; Behera, B.K., Prasad, R., Behera, S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 43–76. ISBN 978-0-323-90447-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kitole, F.; Genda, E. Empowering Her Drive: Unveiling the Resilience and Triumphs of Women Entrepreneurs in Rural Landscapes. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2024, 104, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.; Wilson, S. Evaluating a Women’s Digital Inclusion and Storytelling Initiative through the Lens of Empowerment. Digit. Geogr. Soc. 2024, 7, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiastuti, T.; Al-shami, S.A.; Mawardi, I.; Zulaikha, S.; Haron, R.; Kasri, R.A.; Mustofa, M.U.A.; Dewi, E.P. Capturing the Barriers and Strategic Solutions for Women Empowerment: Delphy Analytical Network Process. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Enayati, M.; Raj, D.; Montresor, A.; Ramesh, M.V. Internet over the Ocean: A Smart IoT-Enabled Digital Ecosystem for Empowering Coastal Fisher Communities. Technol. Soc. 2024, 79, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Devi, N. Digital Literacy: A Pathway toward Empowering Rural Women. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayanand, R.; Khan, Z.; Kalwar, M.; Kumar, A. Digital Literacy for Rural Women’s Empowerment and Socioeconomic Participation: A Comprehensive Study 2024.

- UNDP 5 Facts You Need to Know about Digital Public Infrastructure. Available online: https://www.undp.org/egypt/stories/5-facts-you-need-know-about-digital-public-infrastructure (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Jain, K.; Mathur, N. Analyzing the Impact of Education on Women’s Empowerment: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Res. Rev. Int. J. Multidiscip. 2024, 9, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokal, P.; Sart, G.; Danilina, M.; Ta’Amnha, M.A. The Impact of Education Level and Economic Freedom on Gender Inequality: Panel Evidence from Emerging Markets. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1202014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: Gender Overview 2023; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Yang, L. Digital Literacy’s Impact on Digital Village Participation in Rural Left-behind Women through Serial Mediation of Political Trust and Self-Efficacy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S. Political Empowerment of Women and Financial Inclusion: Is There a Link? Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2022, 5, 100267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. (Eds.) An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–29. ISBN 978-3-030-80519-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two Structural Equation Models: LISREL and PLS Applied to Consumer Exit-Voice Theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The Status of Women in Agrifood Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; ISBN 978-92-5-137814-4. [Google Scholar]

- GSMA. The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/blog/the-mobile-gender-gap-report-2024/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Ragnedda, M.; Ruiu, M.L.; Addeo, F. The Self-Reinforcing Effect of Digital and Social Exclusion: The Inequality Loop. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 72, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women Facts and Figures: Economic Empowerment. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- van Dijk, J. The Digital Divide; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.