Abstract

This concept paper introduces the Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry and Analysis (CCHIA) framework—a critical synthesis tool designed to advance historical contextual inquiry in urban studies. The study aims to develop a structured methodological framework that integrates historical and critical approaches to enhance the analysis of urban phenomena. To develop this framework, we employed a two-fold strategy, conducting a literature search of the social sciences and urban studies using databases including Google Scholar, Web of Science, JSTOR, and Scopus. First, we screened Google Scholar to identify relevant scholars and works published between 1883 and 2024. Second, a content analysis of 58 peer-reviewed articles (2000–2024) was then performed. The concept paper follows a five-stage, 26-step framework integrating four history-focused concepts—interpretive history, historical perspective, historical context, and historical contextualization—alongside three critical approaches: critical discourse analysis, comparative historical analysis, and critical urban theory. By synthesizing these elements, the suggested framework equips researchers to systematically decode the historical and societal forces shaping urban phenomena. CCHIA challenges traditional urban scholarship by leveraging interdisciplinary insights from the social sciences, addressing context as a theoretical perspective for understanding urban formation, and as a critical influence on academic writing. The contribution of CCHIA lies in linking historical analysis to contemporary urban challenges—enabling researchers to focus on previous literature analysis findings to address the current situation’s challenges. The CCHIA framework offers an adaptable toolkit for producing socially engaged and context-sensitive urban textbooks.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, scholars have increasingly disputed the methodological challenges in developing the critical synthesis of urban studies [1,2]. The interdisciplinary focus is evident in the expanding methodologies across the social sciences. In literary studies, this includes critical textual analysis [3]. Contextual inquiry is increasingly applied in education and pedagogy [4]. Higher education research utilizes assessment frameworks to evaluate academic practices [5]. Critical research methodology design further strengthens analytical approaches [6].

Additionally, equity-centered academic writing practices promote inclusivity [7]. In addition, critical historical analysis provides insights into socio-spatial phenomena [8,9]. These studies discuss the complexities of scholarly synthesis and the ongoing efforts to enhance its methodological rigor and impact. Most synthesis processes contextualize authors’ perspectives to trace the evolution of ideas, approaches, and applications within specific social, historical, and cultural contexts [10].

Understanding these contexts is essential for interpreting theoretical contributions and linking past scholarships to contemporary debates [2,3,11,12,13,14]. Context provides a foundational approach that integrates temporal and spatial dimensions, offering valuable insights into explaining historical events while preserving their authentic meaning [14]. By maintaining alignment with the original context, interpretations can retain their connection to specific problems or innovative contributions shaped by the unique circumstances of their time and environment [14].

This contextual grounding is particularly critical in architecture, urban planning, and urban design, where context extends beyond physical settings to cover the complex interplay between urban fabrics, human behaviors, and societal and historical influences. This coverage creates a new approach that reflects the conditions of a particular place, time, and people [11,15,16,17]. Understanding these dimensions is vital for developing theoretical paradigms tailored to specific historical and spatial conditions [11].

Urban researchers overwhelmingly agree that context matters [18,19]. However, a key challenge is the lack of scholarly guidance on incorporating context into text in the critical synthesis of urban studies. Researchers often struggle to effectively integrate ‘context’ and explore the interplay between context and text, leading to missed opportunities to enhance their literature review writings. Additionally, many researchers still stumble when it comes to weaving historical, societal, and spatial dimensions in academic writings [13]. Urban analyses that oversimplify complexities risk overlooking power imbalances, marginalizing voices, and detaching theories from the political and social realities that shaped them [4,10,20].

A fundamental challenge that is often overlooked is that every urban theory, regardless of its level of abstraction, emerges from specific historical and social conditions. If researchers fail to address the roots of such theories, their work risks irrelevance—or worse, complicity in the inequities it seeks to analyze. Every theoretical background in urban studies is inherently shaped by the historical and societal conditions that define its epistemological boundaries, ethical foundations, and practical relevance [12,13,21,22]. Scholars such as Shane [16] and Cuthbert [23] have advanced the principle of contextualism in these fields, but integrating spatial and temporal dimensions remains complex.

Analyses of cities and communities often flatten complexity—skimming over power imbalances, ignoring those whose voices are left out, or treating theories as if they exist in a vacuum, detached from the real-world politics and struggles that shaped them. But here is the problem we often miss: every urban theory, no matter how abstract, is borne from specific historical and social conditions. If we fail to address these roots, the scientific work risks irrelevance or complicity in the inequities it seeks to analyze. Understanding historical, social, and cultural contexts is essential for producing meaningful interpretations in urban studies. Approaches such as interpretive history [24,25,26], historical perspective [27,28,29], and contextual analysis [30] emphasize the value of embedding research within its broader framework. While these approaches highlight the importance of context–text interplay [31,32,33], they often lack the tools necessary to fully address the spatial, temporal, and textual dimensions critical to architecture, urban planning, and urban design. Despite the growing emphasis on contextualizing research [34], existing frameworks like narrative inquiry [35], systematic reviews [36,37], and thematic analysis [38,39] fall short of addressing the unique challenges of these fields.

Recent advancements in historical inquiry [8,40], critical analysis [22,41], and reasoning [42] underscore the need for integrating historical perspectives into urban research. However, a significant gap in methodologies that effectively combine historical context with critical analysis tailored to urban studies remains. This paper addresses this gap by proposing the Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry and Analysis (CCHIA) framework, which integrates critical discourse analysis [43,44], comparative historical analysis [45,46], and critical urban theory [47,48,49]. Designed specifically for architecture, urban planning, and urban design, the CCHIA framework equips researchers with tools to bridge past insights and contemporary challenges, offering a more nuanced approach to urban studies’ critical synthesis.

This research addresses the challenges of integrating context into architecture, urban planning, and urban design. It introduces the Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry and Analysis (CCHIA) framework to examine how historical context shapes urban and architectural discourse. The study applies four history-focused concepts—interpretive history, historical perspective, historical context, and contextualization—alongside three critical methods: critical discourse analysis, comparative historical analysis, and critical urban theory. Its purpose is to provide a nuanced approach to incorporating historical context into the critical synthesis of urban studies.

The literature search was conducted across multiple academic databases, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, JSTOR, and Scopus, selected based on their comprehensive coverage of urban studies and the related disciplines. The selection criteria were influenced by relevance, peer-reviewed sources, and multidisciplinary scope, ensuring a robust and inclusive synthesis of the existing research. The search started by using inquiry keywords including ‘context’, ‘text’, ‘critical synthesis’, ‘urban studies’, ‘architecture’, ‘urban planning’, and ‘urban design’; no direct resources were found to address this issue.

The contribution of this manuscript lies in introducing the CCHIA framework, a novel methodology that enhances urban studies’ critical synthesis by integrating four history-focused concepts and three critical discourse analysis approaches. By addressing the pressing need to effectively incorporate context into architecture, urban planning, and urban design research, the CCHIA framework provides a structured, fifteen-step process for conducting rigorous and contextually sensitive analyses. It emphasizes the interplay between context and text, prompting a deeper understanding of the “when”, “where, and “why” behind urban phenomena, in addition to the “what”. This paper evaluates the framework’s effectiveness in improving urban studies’ critical synthesis through a content analysis of the relevant literature. It offers innovative solutions to challenges in integrating historical inquiry and contemporary analysis. The originality of this study lies in its ability to bridge theoretical frameworks and real-world urban issues, equipping researchers with practical tools to enhance the relevance and impact of their work.

This article proceeds as follows: the introduction is followed by a description of the methodology and the preparation of a list of relevant references. Next, foundational elements from the literature social sciences relevant to the context–text interplay are reviewed. Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6 detail the three-stage development of the CCHIA framework: (1) identifying commonalities and differences among seven key elements (concepts and methods); (2) adapting social science principles to urban studies contexts; and (3) synthesizing these principles into a two-part methodological framework for analyzing urban challenges. Finally, the CCHIA framework is presented, along with a discussion of its contribution, novelty, and added value.

2. Methodology

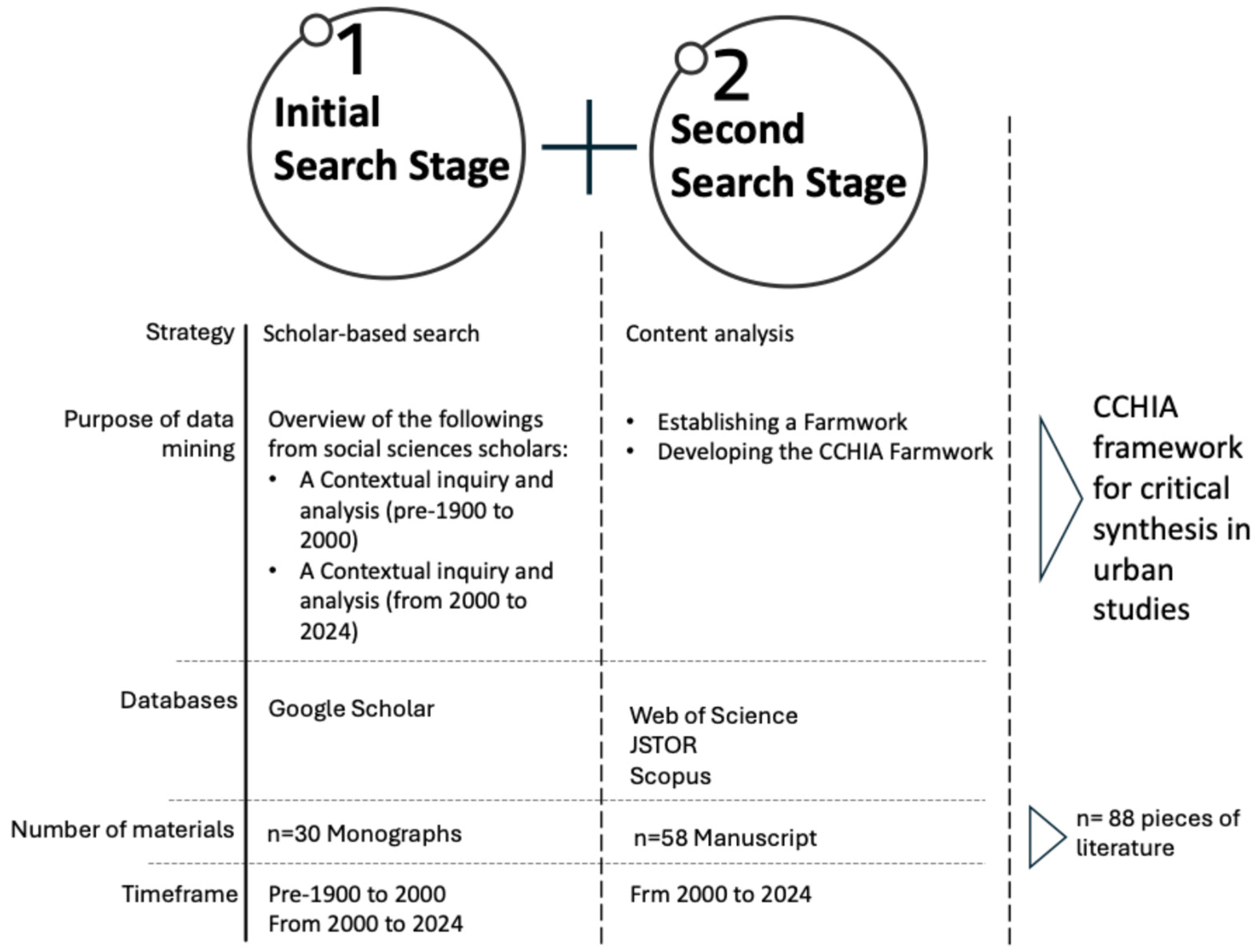

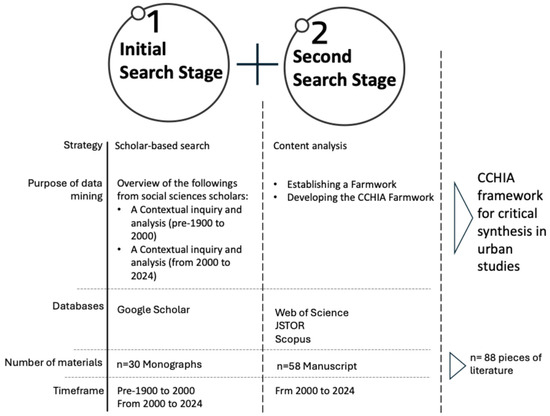

This study employed a two-fold literature search strategy, consisting of an initial search stage of a scholar-based search strategy followed by content analysis (Figure 1). A scholar-based search strategy focuses on identifying the key contributions of influential scholars in the field to establish a foundational understanding of the topic. Content analysis is a qualitative research method used here to interpret textual data by categorizing patterns, themes, and meanings within scholarly works. This strategy aimed to develop a framework integrating historical contextual analyses from the social sciences into the writing of critical syntheses in urban studies.

Figure 1.

A two-fold literature search strategy targeting the CCHIA framework. Note: ‘n’ stands for the number of pieces of literature. Source: the authors.

During the initial search stage, Google Scholar was used to identify prominent scholars contributing to contextual inquiry and analysis. Google Scholar was selected for its comprehensive coverage, citation-based ranking, accessibility, interdisciplinary reach, real-time updates, and global inclusivity. These features make it an effective tool for identifying influential scholars and foundational works in contextual inquiry and analysis, ensuring a robust and well-rounded literature review. The selection criteria of materials in Google Scholar focused on their prominence in the field and the high citation impact of their monographs on Google Scholar. The expected outcome of this stage was to establish a historical background on contextual inquiry and analysis within the social sciences.

The initial search stage of material review focused on elements including history-focused concepts and critical approaches, forming the theoretical foundation. Along with other elements that affect the context–text interplay, we selected these two elements to be relevant to urban studies. History-focused concepts and critical approaches were chosen because they provide a comprehensive lens for understanding the evolution of ideas and the analytical frameworks necessary for evaluating them [21,50,51]. The historical perspective establishes context, tracing developments over time, while the critical approach thoroughly examines underlying assumptions, interpretations, and implications [43,52,53,54]. Together, they form a strong theoretical foundation for the study.

For the second search stage of this study, three databases were selected based on their complementary strengths: Web of Science, Scopus, and JSTOR. Web of Science was chosen for its extensive collection of high-impact, peer-reviewed articles, and robust citation analysis tools, which help to identify influential works in the field. Scopus was included for its multidisciplinary coverage and advanced bibliometric features, enabling a comprehensive analysis of trends and impacts across the social sciences, urban studies, and the related disciplines. JSTOR was selected for its rich historical and archival content repository, particularly in the social sciences and humanities, providing access to the foundational texts and primary sources essential for contextual analysis. These databases ensure well-rounded and rigorous materials for content analysis, combining contemporary research with historical depth.

In addition, the selection of these databases was based on their accessibility for the authors and their relevance to the study’s scope within the social sciences and urban studies. We excluded PubMed due to its focus on medical and natural sciences and omitted Dimensions and Lens, as they were unavailable for use unless specific subsections were accessible.

The content analysis focused on investigating the complex interrelations within urban phenomena and the necessity of interdisciplinary knowledge integration. The directed qualitative approach was also used to construct a comprehensive reference list for analyzing the role of historical context in recent urban studies’ critical syntheses, particularly in architecture, urban planning, and urban design [55]. The following section constructs the reference list from our literature search strategy as follows:

- We identified relevant keywords spanning disciplines such as social sciences and urban studies. We used Boolean operators to refine our results by conducting searches in Google Scholar, Web of Science, or Scopus databases. Keywords included terms like “interpretive history”, “historical perspective”, “historical context”, “historical contextualization”, “contextual analysis”, “contextualism”, “critical discourse analysis”, “comparative historical analysis”, and “critical urban theory”. For urban studies articles, we emphasized topics related to architecture, urban planning, and urban design.

- To ensure the thorough selection of sources, we established criteria emphasizing historical dimensions, critical thinking, and the context–text interplay. These criteria were informed by established quality benchmarks used in similar research, rather than adopting a formal systematic review approach. After identifying over a hundred articles, we applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to refine the results to a manageable scope. The inclusion criteria were limited to peer-reviewed articles indexed in JSTOR, Web of Science, or Scopus, published in high-ranking journals (Q1 and Q2), written in English, and published between 2000 and 2024. Articles not meeting these criteria were excluded to maintain the focus on high-quality sources. This selection process aligns with the research objectives, enabling a targeted and context-sensitive literature review.

The results from the search of the initial research strategy yielded 30 manuscripts, which were classified into two groups (pre and post millennium) based on the publication timeframe, with 8 and 22 monographs, respectively.

The second stage ended with 58 manuscripts indexed in Web of Science, JSTOR, or Scopus, which underwent content analysis of the entire text. The expected outcome from this stage was to build the framework of Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry [8,40,56], followed by developing the CCHIA framework. This framework integrates methodology and philosophical inquiry to enhance the quality of critical synthesis in urban studies across disciplines.

3. Results from the Initial Stage

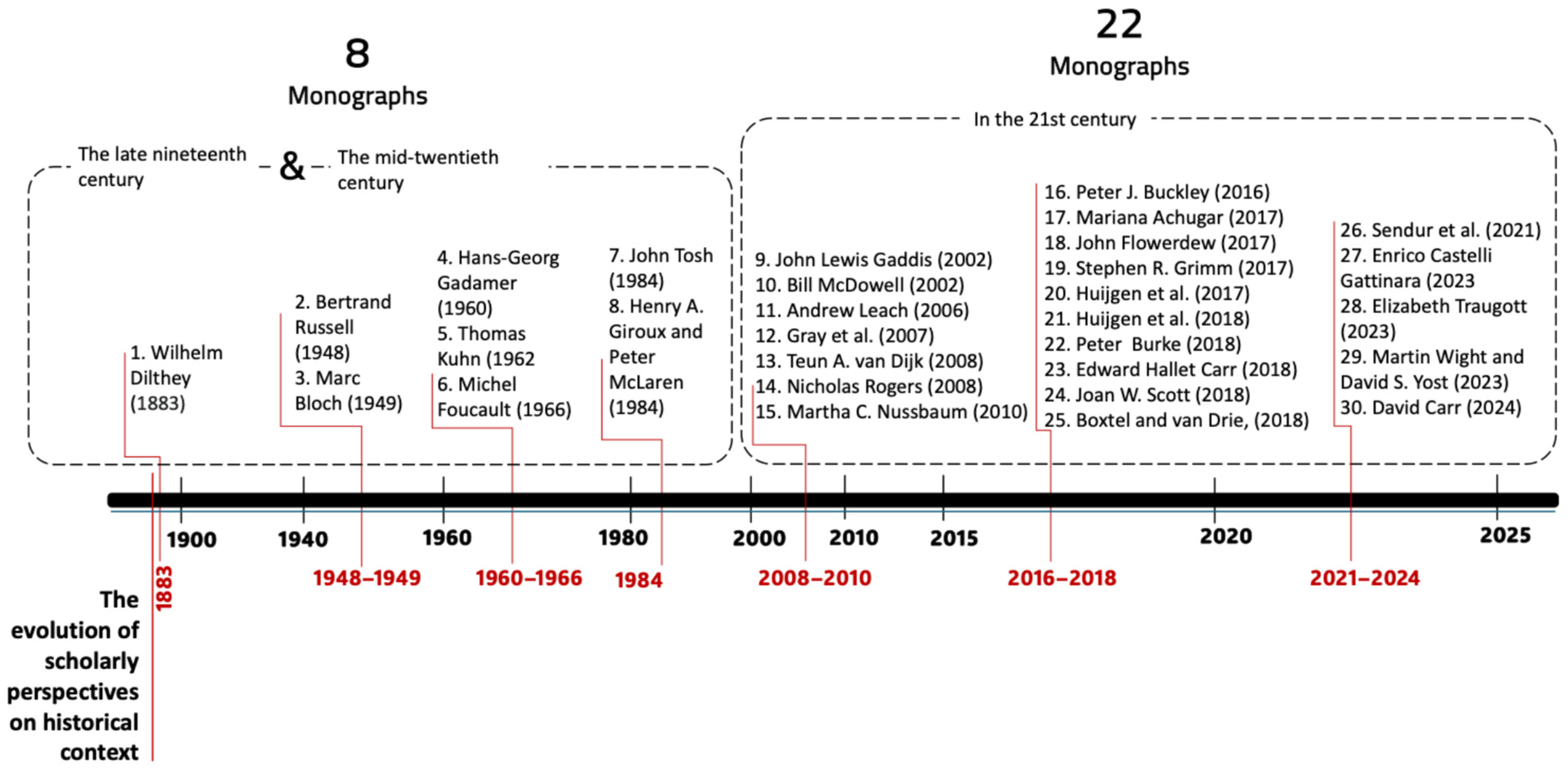

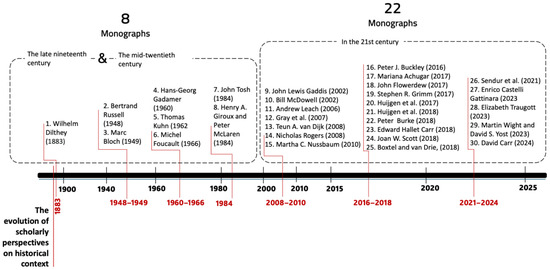

Studying history to examine the interactions of context–text interplay in social science research is very important, as it sustains theoretical bases, promotes critical thinking, and enhances awareness of historical and current issues. Figure 2 presents a timeline illustrating the evolution of scholarly perspectives on historical context and critical synthesis. It covers the period from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century to the 21st century (1883–2024). The timeline highlights 30 seminal works that inform this study’s contextual and conceptual framework.

Figure 2.

The timeline of the selected 30 seminal monographs on historical context (1883–2024). The text in red represents the selected timeframe for investigation in this study. Source: the authors based on literature [13,19,21,22,25,26,27,28,29,32,41,42,43,51,53,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69].

The timeline, featuring 30 authors, is divided into two periods—pre 1900 to 2000 and 2000 to 2024—demonstrating the chronological development of critical synthesis regarding historical–contextual inquiry (see Supplementary A, Tables S1 and S2). The following section presents two sub-sections derived from the initial data search. The first traces the evolution of scholarly perspectives on historical context and critical synthesis from the late 19th century to the present, highlighting key contributions from influential thinkers such as Dilthey, Russell, Bloch, Gadamer, Kuhn, and Foucault, who shaped historical inquiry and analysis. The second sub-section explores advancements in the 21st century, including contextual analysis, historical reasoning, and the integration of critical historical inquiry across various disciplines.

3.1. A Contextual Inquiry and Analysis (Pre 1900 to 2000)

Early outcomes in the late nineteenth century contained foundational work by Wilhelm Dilthey [57]. His Introduction to the Human Sciences, initially published in 1883, laid the groundwork for determining the natural sciences’ explanatory approach to the human sciences’ interpretive one [57]. Central to his argument was the irreplaceable role of historical context in understanding the human experience. In the early twentieth century, Bertrand Russell [58] offered integrated insights into the methodology of historical inquiry in his Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits, initially published in 1948–1949. At about the same time, through his historical research and in light of his empirical methods that called for examining sources to construct realistic narratives, the well-known historian Marc Bloch [59], in his influential work The Historian’s Craft, became a cornerstone of historical standpoints.

In the mid-twentieth century, especially the 1960s, a theoretical paradigm shift toward a refined process of integrating interpretive approaches into narrative studies [70] was detected. It served as a benchmark for understanding the development of ideas and processes of knowledge and understanding and their adaptation to changing historical perspectives and societal realities. In this vein, significant literature by the most famous respected pioneers in this field, such as Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Truth and Method [25], initially published in 1960; Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions [26], initially published in 1962; and Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish [24], initially published in 1966, are included. Gadamer [25] was a crucial scholar in this paradigm shift, as he profoundly influenced how we consciously understand the production and interpretation of historical knowledge and fundamentally informed scholars’ understanding of history. While Gadamer’s [25] work revolutionized the investigation of historical narratives by emphasizing the crucial role of self-interpretation (the cornerstone of interpretation), Kuhn’s concept of paradigm shifts simultaneously shed light on how changes in intellectual frameworks reshaped them [26]. Previous research indicated that Foucault [24] analyzed how power structures influence narratives, highlighting the importance of considering broader social contexts.

In the late 20th century, fairly recent studies indicated the convergence of history and critical theory. In the book The Pursuit of History by Tosh [21], which focuses on modern history’s aims, methods, and new directions, John Tosh handled the objectives, methods, and progressive approaches of historical study. Tosh highlights the importance of contextual analysis in understanding historical phenomena. That same year, Giroux and McLaren’s edited volume of Critical Pedagogy, the State, and Cultural Struggle framed education as a dynamic cultural and historical process [61]. They argued that this perspective deepens critiques of educational practices, while revealing how historical and societal forces shape possibilities for resistance, transformation, and social reform within pedagogy.

3.2. A Contextual Inquiry and Analysis (From 2000 to 2024)

Over time, extensive literature has advanced the social sciences; the twenty-first century has highlighted historical context concepts. John Lewis Gaddis [62] contributed foundational methods in historical inquiry, focusing on analyzing sources to reconstruct objective historical narratives. Bill McDowell [63] further emphasized the crucial role of historical context throughout history, arguing that social sciences literature should thoroughly examine historical context and contextualization to enrich our understanding of current issues and bridge the past and present, particularly before drawing conclusions based on quantitative data.

Andrew Leach [64] explored the dynamics between historical interpretation and societal influences, informing the methodological rigor of urban studies. The applications of this historical perspective—inquiry, thinking, analysis, reasoning, and criticism—are diverse, including historical analysis [56]. Teun A. van Dijk [29] and Nicholas Rogers [28] emphasized the role of historical thinking in education, underlining contextual factors’ contributions to fostering critical engagement through historical perspectives.

Further contributions to various historical perspective applications emerged in the mid-2010s, such as the historical research approach that investigate cities’ identities [65,71], historical reasoning [42], and historical contextualization [13,32,72]. In the late 2010s, scholars like Mariana Achugar [43], John Flowerdew [53], and Stephen R. Grimm [51] contributed to these perspectives, integrating discourse analysis to connect urban studies with critical historical insights. The field of critical historical inquiry continues to evolve, with contemporary scholars such as Peter Burke [66], E.H. Carr [66], and Joan W. Scott [68] stressing that the fluidity of historical contexts within critical historical inquiry evolves and shapes contemporary academic discourse. Moreover, Huijgen, van de Grift, van Boxtel, and Holthuis [72] focused on pedagogy, advocating for teaching historical thinking to include the complex socio-cultural factors shaping historical events.

Recent advancements have linked architectural history with contemporary practices to reveal the impact of historical perspectives on modern design. Stefano Gattinara [69] has made seminal contributions; for instance, he links architectural history with current practices, exploring how historical perspectives influence modern design. Elizabeth Traugott [19] presented how elements of socio-linguistic circumstances and their cultural patterns shape linguistic transformation.

Similarly, Wight and Yost [41] emphasize vital components of historical analysis, including the critical use of sources, narrative structure, and integrated insight. Numerous studies have investigated a diverse approach that considers history as a group of objective events, stressing instead the dynamic interplay of human experiences and interpretations. The literature records different views on using the phenomenological approach, which raises the value of historical inquiry in urban research. David Carr [22] argues that personal and collective experiences are integral to interpreting historical events. In this vein, Carr [22] demonstrates how this approach can provide a more profound and greater understanding of the historical world by integrating phenomenological insights into historical analysis.

A more comprehensive description of this result from the initial stage of the research strategy highlights the value of incorporating historical perspectives into academic discussions to better address today’s challenges. Researchers should show how their work environment shapes historical phenomena, situating history within specific social and cultural settings. The discussion should unfold along two main axes: historical inquiry and historical analysis. The first axis, historical inquiry, includes ideas like interpretive history, historical perspective, historical context, and historical contextualization—key concepts that help build rich narratives connecting past events to present realities. The second axis, including contextual analysis and critical thinking, focuses on historical methods, which provide insights to strengthen academic works’ theoretical and methodological foundations.

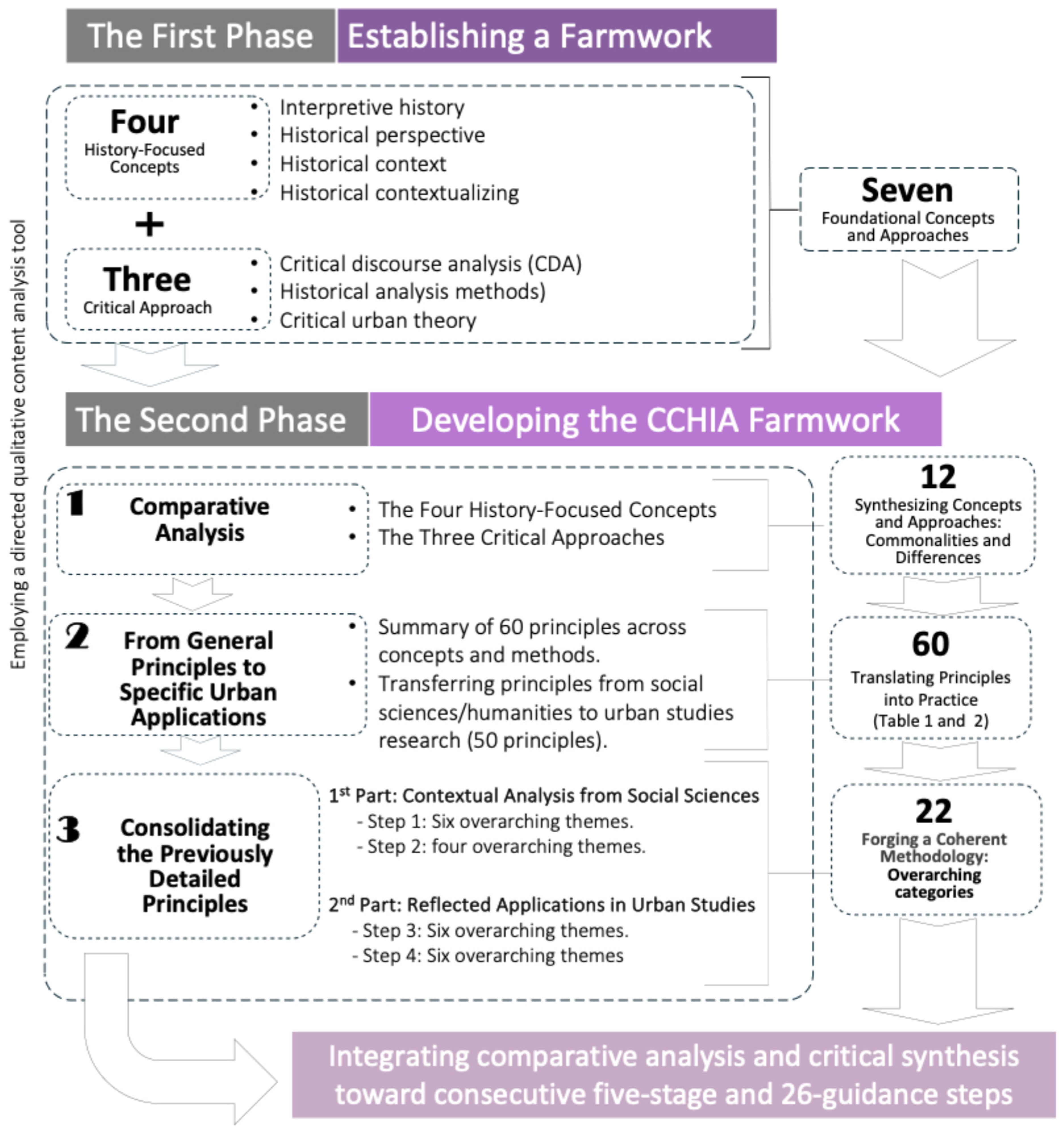

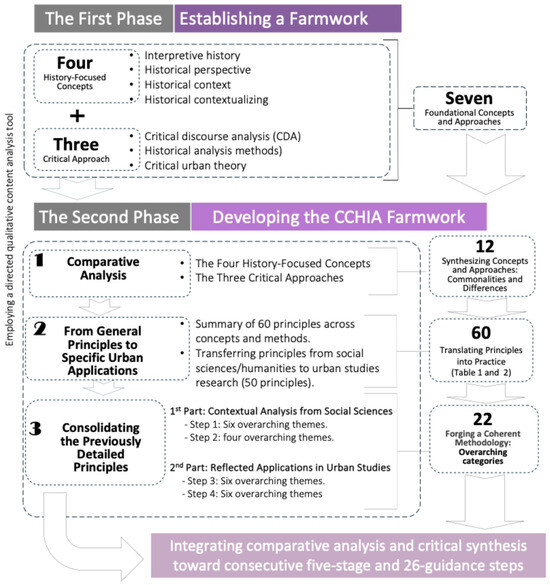

4. The First Result from the Second Stage: Establishing a Framework

Building on data from the content analysis of 58 manuscripts, this section establishes the theoretical foundation for the Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry and Analysis (CCHIA) framework (Figure 3). Based on our content analysis, we examined seven foundational elements. These include four history-focused concepts: interpretive history, historical perspective, historical context, and historical contextualization. Additionally, we identified three critical approaches: critical discourse analysis, comparative historical analysis, and critical urban theory. These elements shape the interplay between context and text in the social sciences, as discussed in the background section.

Figure 3.

The two-phase process of content analysis ending with the suggested CCHIA framework. Source: the authors.

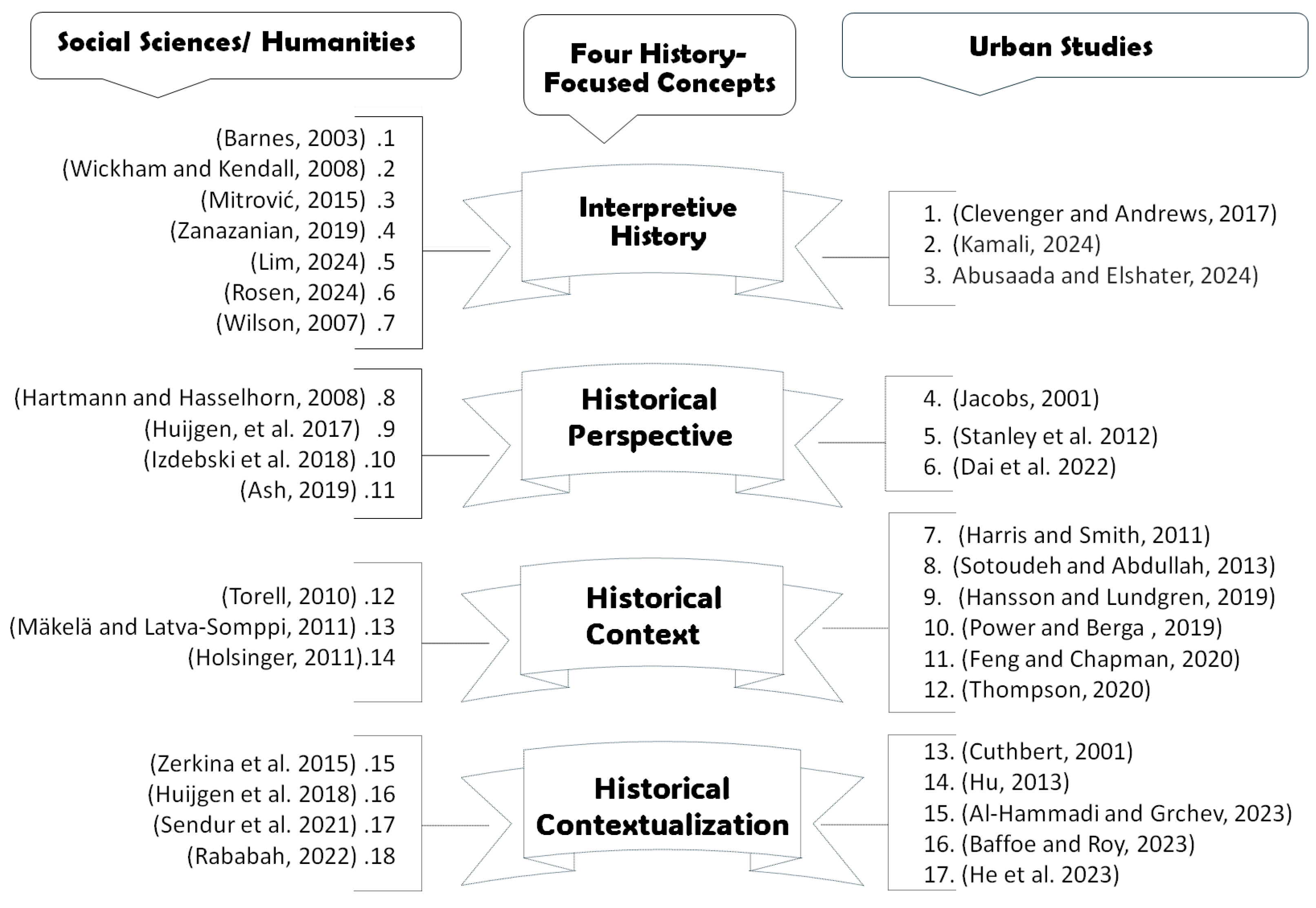

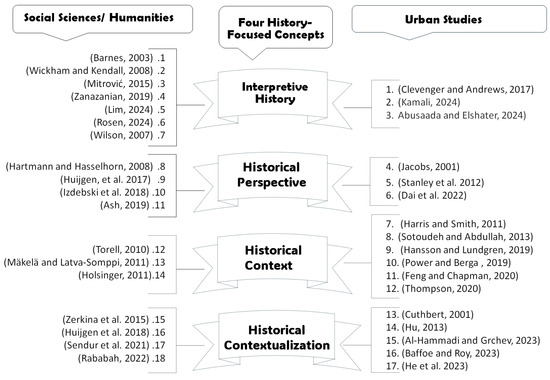

4.1. Four History-Focused Concepts in the Social Sciences and Urban Studies

This investigation clarifies how these seven elements (concepts and approaches) shape historical texts in social sciences. It provides depth and justification for the proposed framework and enhances its ingenuity and contribution to urban studies research. Furthermore, it highlights the framework’s interdisciplinary nature, which enhances its credibility, value, and potential applicability within the academic community. This analysis clarifies how these elements shape historical texts, demonstrating the framework’s originality. In this vein, two groups included the selected articles:

- -

- The first group focused on four history-focused concepts (interpretive history, historical perspective, historical context, and historical contextualization), guiding the selection and categorization of 35 articles. These articles, which illustrate historical context, historical thinking, and critical discourse analysis and influence interpretation, were further categorized into two groups of disciplines: social sciences (18 articles) and architecture, urban planning, and urban design (17 articles), as illustrated in Figure 4 (see Supplementary B: Table S3 for social sciences, and Table S4 for urban studies).

Figure 4. Thirty-five sources for the four history-focused concepts are based on social sciences and urban studies research. Source: the authors based on literature [3,30,31,32,33,50,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80].

Figure 4. Thirty-five sources for the four history-focused concepts are based on social sciences and urban studies research. Source: the authors based on literature [3,30,31,32,33,50,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80].

- -

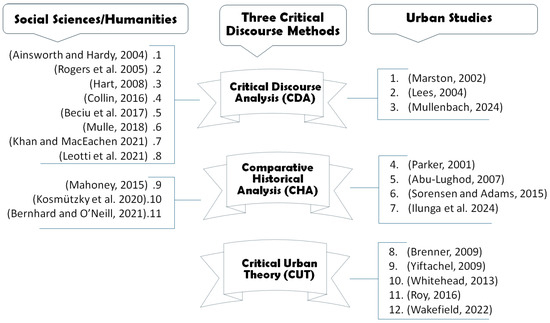

- Building on the concepts discussed in the background section, the present section confirmed the findings about the second group. It introduced three essential critical historical inquiry and analysis methodologies, each offering unique tools to explore the context–text interplay. This group categorized 23 peer-reviewed articles, as illustrated in Figure 5 (see Supplementary C: Tables S5 and S6).

Figure 5. Twenty-three sources for the three methods are based on social sciences and urban studies literature. Source: the authors based on literature [45,46,47,48,49,54,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96].

Figure 5. Twenty-three sources for the three methods are based on social sciences and urban studies literature. Source: the authors based on literature [45,46,47,48,49,54,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96].

The analysis begins by exploring how context and text interact in various pieces of selected social science literature to establish the theoretical basis for this article. Thus, theoretical basis concludes with seven elements used by social sciences, humanities, and urban studies theorists, divided into two axes: four history-focused concepts and three critical approaches. The following sub-section examines four key history-focused concepts—interpretive history, historical perspective, historical context, and historical contextualization—that are pivotal for analyzing urban phenomena.

4.1.1. Interpretive History

Interpretive history is a methodological approach that enhances historical thinking by uncovering the subjective meanings and contextual factors shaping historical events. It goes beyond objective recounting, integrating diverse sources such as locational analysis [73], personal narratives [30], and critical discourse analysis [74] to transcend a strictly objective recounting of facts by linking historical events to broader theoretical frameworks and incorporating the concept of historical consciousness [50,75].

Interpretive history offers a critical perspective for analyzing the social, temporal, and cultural dynamics of historical phenomena in the social sciences. The following principles highlight their transformative potential in these disciplines. For instance, Barnes [73] highlights the role of locational analysis in revealing socio-political and intellectual influences embedded in historical and cultural contexts. Wilson [30] demonstrates how personal narratives add depth to historical interpretations. Wickham and Kendall [74] emphasize the multifaceted nature of historical interpretation, privileging the perspectives of historical actors and situating their actions within unique social and temporal contexts. Mitrović [75] explores how historical consciousness shapes cognitive processes, enabling researchers to engage with historically rooted social problems.

Quantitative and qualitative methods further enrich interpretive history. Lim [76] argues that quantitative analysis uncovers patterns and trends in historical phenomena, while qualitative inquiry examines long-term developments and their implications for contemporary and future trends. These methods establish a rigorous and nuanced foundation for interpreting historical records and connecting them to broader cultural and social approaches. Additionally, employing interpretive validation methods, such as assessing conjuncture, scope, intersection, comparability, and self-accounting, supports diverse interpretations [77]. These principles collectively demonstrate the importance of a rigorous and nuanced approach to interpretive historical analysis.

In urban studies, interpretive history provides critical insights into the design of cities by examining how social values and ideologies shape architecture, urban planning, and urban design decisions. For example, Clevenger and Andrews [97] analyze Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City concept, revealing how socio-political and environmental factors shaped their principles in response to industrialization. Their study highlights four key principles: (a) examining the interplay between architectural forms and public health discourses, (b) understanding Garden City’s responses to socio-environmental challenges, (c) linking its design to a broader ideological approach, and (d) recognizing architecture’s role in shaping societal health and spatial practices.

Likewise, Kamali [98] adopts a historical interpretation approach to contemporary architecture, emphasizing the influence of historical narratives on design principles. This perspective underscores the interplay between historical contexts and modern architectural thought, revealing the impact of societal values, cultural symbolism, and political ideologies on design. Key principles include: (a) analyzing historical influences on architectural discourse, (b) bridging historical analysis and contemporary design, and (c) interpreting architecture as a cultural artifact reflecting the relationship between historical context and modern expression. Abusaada and Elshater [99] expand on this approach by examining how architects draw on urban history to inspire innovative designs. Their study illustrates how analogies and metaphors derived from historical urbanism foster creative problem-solving, linking past urban forms to challenges. Key principles include (a) integrating historical insights into urban approaches, (b) exploring the influence of historical metaphors on design thinking, and (c) demonstrating how interpretive history bridges historical inspiration and contemporary architectural creation.

4.1.2. Historical Perspective

Historical perspective is an analytical approach that enhances historical thinking and writing by contextualizing events within a broader strategy. It transcends cataloging dates and facts, focusing instead on the social, cultural, and intellectual dimensions shaping historical phenomena [31]. This perspective is essential for understanding how historical events and policies establish enduring patterns that influence contemporary issues, particularly societal challenges. By examining the interplay between historical narratives and their contexts, researchers uncover the dynamic processes that shape modern problems. Situating events within their socio-political, cultural, and economic contexts offers more profound insights into their long-term implications [32]. This approach critically engages with historical context, narratives, and sources, enabling more nuanced interpretations of past and present connections.

In social sciences, historical perspective provides a critical approach for understanding complex societal issues and informing contemporary research. The following principles underline its transformative potential in these disciplines. For instance, Hartmann and Hasselhorn [31] demonstrate how examining the long-term consequences of historical events reveals enduring societal impacts that transcend immediate reactions. Similarly, Huijgen et al. [32] highlight the analysis of decisions and events within their specific temporal, social, and cultural contexts, fostering critical thinking and more nuanced interpretations. Izdebski et al. [33] emphasize maintaining the contextual integrity of historical phenomena, which ensures accurate connections between past actions and present-day challenges while avoiding anachronistic interpretations. Ash [78] stresses the value of integrating multidisciplinary perspectives to understand the complex impacts of historical processes better. These principles show how historical analysis enriches our understanding of societal dynamics and contributes to developing solutions to current challenges.

In urban studies, historical perspective provides a robust approach to uncovering patterns and informing current debates. The following findings highlight the transformative potential of historical perspectives in urban research. These insights reveal critical connections between past and present, fostering a deeper understanding of the socio-spatial dynamics that shape contemporary urban challenges. For example, Jacobs [100] shows how the development of housing policies created enduring inequalities, offering insights into modern urban challenges. Similarly, Stanley et al. [101] explore historical changes in urban open spaces, illuminating their ecological, social, and political roles today. Dai et al. [102] examine traditional urban systems shaped by historical environmental and cultural conditions, offering strategies for addressing climate change resilience. These principles highlight the essence of historical analysis in formulating equitable and informed solutions for present-day urban issues.

4.1.3. Historical Context

Historical context is a critical methodological approach that examines the forces, conditions, and events shaping the creation and interpretation of historical concepts. It emphasizes the influence of ideologies, biases, and social dynamics on historical approaches, offering significant benefits in social sciences research. By linking past and present, this approach enhances the theoretical rigor of studies, uncovers hidden biases, and highlights power dynamics. It also fosters critical thinking and pedagogy, encouraging nuanced interpretations and engagement with complex social issues, ensuring the accuracy of historical data and addressing potential research biases.

Additionally, it ensures the accuracy of historical data and interpretations, addressing potential biases in research. Mäkelä and Latva-Somppi [103] believe that historical context is essential in the literature of the social sciences. It anchors ideas, theories, and practices within their specific time, place, and circumstances, deepening the analysis. Historical context is a reflective tool in narrative crafting, demonstrating how engaging with historical context enriches creative processes and textual interpretations. At the same time, Bruce Holsinger [3] believes that historical context is far more complex than a backdrop for events or a list of facts. He suggests that historical context is a dynamic force that shapes and informs the text. It is not merely about surface details or chronological events, but about understanding the deep, underlying forces that shape the creation and reception of a text. Holsinger [3] emphasizes the importance of establishing the context through careful analysis, rather than assuming it is simply there to be discovered. He suggests that this can be carried out by uncovering the intricate web of social, cultural, political, and economic factors present during a text’s creation. As such, this manuscript provides a deeper understanding of its meaning and significance.

Three fundamental principles should be considered when effectively applying historical context in urban sciences: Torell [79] emphasizes the critical assessment of past policies and practices to understand their influence on contemporary environmental challenges, enabling the development of more informed and responsive policies that address historical legacies and present-day needs. Mäkelä and Latva-Somppi [103] highlight the importance of connecting historical narratives to their specific socio-historical conditions to enhance researchers’ interpretative capabilities and provide an approach to understanding the evolution of cultural meanings over time. Finally, Holsinger [3] stresses recognizing the multifaceted nature of historical context, emphasizing its ever-evolving role in shaping critical thought and fostering nuanced interpretations. When applied rigorously, these three principles demonstrate the value of historical context in enriching architecture, urban planning, and urban design research and practice.

Historical context is vital for studying urban studies. Extensive research illustrates the interplay between historical forces and urban development outcomes. For instance, Harris and Smith [104] demonstrate how integrating heritage considerations enriches urban design. Further illustrating this point, Hansson and Lundgren [105] show how contextual forces shape housing policy, and Power and Berga [106] highlight the mutual influence of texts and their social contexts. Feng and Chapman [107] explore how historical narratives establish the legitimacy of authority. In addition, Thompson [108] investigates the connection between socio-historical dynamics and innovations in housing. Lastly, Ceylan [109] emphasizes the significance of historical awareness in design decisions, resulting in more thoughtful and contextually responsive architectural solutions.

4.1.4. Historical Contextualization

Historical contextualization concerns placing an event or phenomenon within its broader historical and societal problems. This approach uncovers the connection between the issue and its time. One must understand the historical context to effectively contextualize events, societal norms, technological advancements, and geographic factors. This approach emphasizes analyzing the subject’s background and purpose and the societal conditions that influenced its creation and subsequent interpretations [32,110].

The process of historical contextualization includes (a) providing a descriptive account of the relevant circumstances surrounding the subject, (b) emphasizing the significance of its time and place, and (c) exploring how historical conditions shaped its creation and interpretations [13]. By examining these elements, researchers can understand how values and historical dynamics influenced the subject’s development and meaning [72]. This approach enables critical thinking and a perspective of more profound paid attention to historical phenomena, as illustrated across disciplines in the social sciences [110].

These principles could be included in analyzing the historical and cultural foundations of texts in the social sciences. Zerkina, Kostina, and Pesina [111] highlight the importance of understanding how historical and social contexts shape texts and how discourse reflects and perpetuates societal values and norms. Huijgen et al. [72] and Sendur et al. [13] demonstrate that explicitly teaching contextualization improves students’ analytical reasoning and argumentation skills, emphasizing that it is a teachable rather than innate ability. Huijgen et al. [72] further advocate for active learning strategies, such as guided inquiry and reflective tasks, to foster critical engagement with historical sources. Sendur et al. [13] also highlight the transferability of contextualization skills across diverse learning contexts, including for second-language learners. Finally, Rababah [110] emphasizes the importance of recognizing historical texts as both products and agents of societal change, exploring the interplay of historical forces in shaping narratives, and acknowledging the dual nature of historical evidence. These studies collectively underscore the multifaceted nature of adequate historical contextualization.

In urban planning and urban design, historical contextualization integrates historical perspectives within specific contexts to address complex urban issues. This process ensures that architecture, urban planning, and urban design reflect unique local histories and evolving needs. For example, Cuthbert [23] emphasizes the importance of blending global trends with local histories in urban design, while Hu [112] demonstrates how integrating historical awareness into contemporary challenges informs effective design practices. Al-Hammadi and Grchev [113] illustrate this concept through their analysis of contextual architecture, showcasing the balance between tradition and modernity. These examples highlight the dynamic role of historical contextualization in creating urban spaces that are both historically grounded and responsive to contemporary demands.

Additionally, Baffoe and Roy [114] explore how colonial-era planning continues to shape urban structures and governance, emphasizing the need to understand historical legacies to address overcrowding and inequity. Their analysis illustrates how past actions have lasting consequences that must be understood for effective future planning. He, Yuan, and Chen [80] emphasize that urban heritage management is dynamic and shaped by shifting socio-political identities, as seen in the reinterpretation of Beijing’s colonial-era planning. Their work demonstrates how historical understanding evolves with changing social and political landscapes, making it essential for adaptive urban studies, particularly architecture, urban planning, and urban design.

4.2. Three Critical Approaches

This section examines three established critical analytical approaches in the social sciences: critical discourse analysis (CDA), comparative historical analysis (CHA), and critical urban theory (CUT). Critical discourse analysis (CDA) focuses on the power dynamics within discourse, offering tools to analyze how language constructs and perpetuates social hierarchies [85,115,116,117]. CHA examines causal mechanisms and historical trajectories to understand how past events shape present societal structures [45,46,54]. Critical urban theory (CUT) expands the analytical scope by critiquing depoliticized interpretations of urbanization. It emphasizes the interplay between historical legacies, socio-political contexts, urban governance, and spatial practices [47,48,49]. CUT interrogates the historical foundations of neoliberal urban policies and the role of global capital in shaping cities, while advocating for social justice in urban research and praxis [95,96]. While CDA and CHA provide structured methodologies for dissecting discourses and historical processes, CUT offers a theoretical perspective for critiquing socio-political forces in urban environments. By drawing on insights from CDA (e.g., language–power dynamics) and CHA (e.g., historical causation), CUT enriches urban analysis by connecting historical narratives, socio-political contexts, and spatial realities.

4.2.1. Critical Discourse Analysis

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is a qualitative methodological approach focusing on the intricate relationships between language, power, and society. CDA explicitly investigates how discourse reflects and reinforces power structures, ideologies, and social inequalities. Widely applied across disciplines such as educational research [82,84,85,112] and broader social sciences—including qualitative social work and critical discourse studies [54,86,115,116]—CDA examines how language reflects and constructs power dynamics. Employing linguistic and analytical techniques reveals how texts are shaped by social and historical contexts, reinforcing ideologies and societal contradictions.

For instance, CDA explores critical societal challenges such as identity, racism, and inequality, offering profound insights into how language drives historical and social change [116]. In historical and social research, CDA critically investigates language within historical texts, policies, and discourses to expose the perpetuation of power imbalances and social inequalities. Scholars like Wickham and Kendall [74] influenced Foucault’s [24,60] theories to demonstrate how historical documents subtly entrench power hierarchies. Similarly, Collin [54] integrates Marxist literary critiques to highlight the embedded conflicts and power structures in language, showing how historical narratives can influence transformative social movements. As a tool, CDA is invaluable in contexts where discourse reinforces or disrupts societal hierarchies [83]. For researchers, CDA offers an approach to understanding how language legitimizes dominant ideologies and marginalizes vulnerable groups, enabling analyses that challenge entrenched inequalities.

Fundamental principles include those present in the work of Ainsworth and Hardy [115], highlighting the importance of uncovering hidden biases and power structures embedded within discourse. Hart [116] emphasizes understanding texts as reflections of historical changes, while Collin [54] examines how discourse transforms societal approaches. Khan and MacEachen [85] and Mulle [84] emphasize the critical interrogation of language’s influence on shaping public perceptions. In addition to CDA, Leotti et al. [86] critically analyze how language constructs social realities that extend beyond surface meanings, revealing how dominant groups are legitimized while vulnerable groups are marginalized, thus informing transformative social practices.

In urban studies, CDA is a valuable methodological tool for examining how language and discourse influence urban power dynamics, social inequalities, and the lived experiences of diverse social groups. CDA enables researchers to analyze the language of planning documents, policies, and public narratives, revealing how these discourses reflect and reinforce societal power structures in urban development. By treating language as a formative force that shapes social realities, CDA uncovers the ways in which urban spaces are organized and contested, particularly in the context of systemic inequities. For example, Greg Marston [88] employs CDA to critique policy-oriented housing research, demonstrating how dominant narratives frequently marginalize the voices of vulnerable populations facing housing insecurity. He argues that uncovering these biases is essential for promoting more inclusive and equitable housing policies.

Loretta Lees [89] investigates how urban discourses are deeply embedded in power relations and historical contexts, revealing how policies and narratives shape perceptions of space and urban identities. Her work highlights the constructive role of language in defining urban life while reinforcing societal norms. Lauren E. Mullenbach [90] applies CDA to park-development narratives, showing how these often prioritize social benefits while neglecting the needs of marginalized communities. Her analysis reveals that such narratives can inadvertently facilitate gentrification, displacing vulnerable groups. Mullenbach [90] advocates for reframing urban discourses to foster equitable development, ensuring urban spaces are inclusive and benefit all community members, rather than perpetuating existing inequalities.

4.2.2. Comparative Historical Analysis (CHA)

By employing CHA, urban researchers trace the evolution of urban planning approaches and city infrastructures, revealing how social, political, and economic forces have historically shaped urban areas. This approach uncovers patterns, contradictions, and community dynamics across cities with varied models and historical paths, offering nuanced insights into urban transformations. In social sciences research, one of the goals of using CHA is to generate causal arguments and mechanisms relevant to macro-social phenomena. For example, Mahoney [46] used CHA to derive context-based comparisons, revealing insights into human behavior and social structures while critiquing the existing theoretical approaches. Similarly, Kosmützky, Nocala, and Diogo [45] emphasized contextualization by examining how historical, social, and political factors shape phenomena while ensuring valid comparisons across historical trajectories. Their work uncovered structural patterns and differences over time. In comparative politics and international relations, Bernhard and O’Neill [87] used CHA to analyze the interplay between historical decisions and institutional practices in comparative politics and international relations, demonstrating their influence on urban governance and societal change. This approach makes CHA a respected methodology across diverse social sciences disciplines.

Notably, CHA is utilized to identify recurring themes and unique variations within historical and institutional contexts. Parker [91] applied CHA to analyze urban identities and the structuration of power. Abu-Lughod [92] underscored the role of cultural and historical distinctiveness in urban experiences, comparing cities to unravel the complexities of urban development.

Similarly, Sorensen and Adams [93] employed CHA to explore the interplay between property regulations and urban development, tracing the influence of regulatory approaches across historical and political contexts. Ilunga et al. [94] extended this approach to examine the evolution of “soft” urban planning policies, revealing their implications for consensus building and public engagement. CHA provides a robust approach to understanding the socio-political and institutional forces underpinning urban governance, planning, and development by focusing on causal mechanisms and context-sensitive analysis. This approach enables scholars to dissect complex interactions between historical decisions, policy texts, and societal dynamics, offering critical insights into the processes driving urban change.

4.2.3. Critical Urban Theory (CUT)

Critical Urban Theory (CUT) emerged as a response to the limitations of traditional urban planning and urban design, which often approached cities from neutral, technocratic, and depoliticized perspectives. Developed in the late 1960s and 1970s, CUT critiques the socio-political, economic, and ecological forces that shape urban environments. This approach emphasizes how urban policies, power structures, and capitalist ideologies perpetuate inequalities, particularly affecting marginalized communities [47,49]. CUT draws on critical social theories to analyze urban governance, focusing on spatial disparities and resistance to exclusionary practices.

The principles of Critical Urban Theory (CUT) in the works of Brenner [47], Yiftachel [49], and Roy [48] stress the socio-political nature of urban spaces and the power dynamics that shape them. CUT critiques urban governance, emphasizing how neoliberal policies and capitalist ideologies perpetuate inequalities [47], while linking language and power structures to urban marginalization [49]. This critique extends by focusing on urban informality and the production of inequality in the global South, highlighting dispossession and resistance [48]. These examples demonstrate CUT’s capacity to reveal the socio-economic and political mechanisms behind urban struggles and inequality.

Moreover, Whitehead [95] and Wakefield [96] expand CUT’s focus to ecological dimensions, emphasizing the need for equitable urban planning in the face of climate change. Whitehead [95] examines how climate adaptation policies disproportionately affect marginalized communities, advocating for socio-environmental justice. Wakefield [96] supports this, urging a rethinking of urban governance to address new ecological challenges within the social justice approach. Both emphasize the interconnectedness of social and environmental issues, underscoring CUT’s interdisciplinary approach to addressing urban inequalities while criticizing neoliberal approaches perpetuating exclusion and environmental harm.

5. The Second Result from the Second Stage: Developing the CCHIA Procedure

This section outlines the iterative three-stage process behind developing the Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry and Analysis (CCHIA) framework—a tool designed to bridge historical scholarship and contemporary urban practice through contextually grounded research. In the first stage, the CCHIA synthesizes the shared foundations and divergences among four history-focused concepts and three critical approaches, identifying synergies and tensions in their theoretical underpinnings. The second stage transitions from abstract principles to actionable methodologies, exploring how broad perspectives from history and philosophy—such as hermeneutics, power dynamics, and epistemological shifts—can be translated into concrete architectural, urban planning, and design strategies. Finally, the CCHIA framework combines the previously discussed principles into a coherent methodology for addressing complex urban challenges. Connecting historical context with urban design ensures analytical rigor and contextual sensitivity across architectural, urban planning, and urban design research.

A content analysis of the selected literature (2000–2023) identified twelve key commonalities and differences (four related to history-focused concepts and eight to critical approaches), yielding 50 principles (36 from history-focused concepts and 14 from critical approaches).These principles, adapted from social sciences research, were organized into 22 overarching themes (four representing social sciences and six urban studies) and integrated into the Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry and Analysis (CCHIA) framework to demonstrate how historical perspectives enhance the analysis of contemporary urban issues.

5.1. Comparative Analysis: Commonalities and Differences

This section examines the commonalities and distinctions among four history-focused concepts—interpretive history, historical perspective, historical context, and historical contextualization—and three critical approaches—critical discourse analysis (CDA), comparative historical analysis (CHA), and critical urban theory (CUT)—in their application to urban studies’ critical synthesis.

5.1.1. Comparative Analysis of the Four History-Focused Concepts

The critical synthesis of these four history-focused concepts reveals their interconnectedness and distinctions in scope, interpretation, methodology, and applicability. All four require interdisciplinary analysis, but they diverge in emphasis—historical perspective integrates economic and cultural viewpoints, while historical contextualization prioritizes immediate socio-political influences. A shared commitment to historical interpretation unites them, though their focus varies: historical context objectively examines socio-political conditions, historical perspective bridges long-term patterns and contextual specifics, and historical contextualization situates events within precise temporal and spatial frameworks. Methodologically, all four rely on qualitative inquiry, yet interpretive history emphasizes self-narratives, historical contextualization systematically analyzes structures, and historical perspective identifies overarching temporal trends. Their practical utility in urban studies also differs—historical perspective and context help explain contemporary urban policies. In contrast, interpretive history remains anchored in understanding events within their original cultural and temporal settings. By synthesizing these approaches, critical synthesis strengthens urban research by ensuring analytical depth, contextual awareness, and methodological rigor, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of historical influences on present-day urban challenges.

5.1.2. Comparative Analysis of the Three Critical Approaches

The critical synthesis of critical discourse analysis (CDA), comparative historical analysis (CHA), and critical urban theory (CUT) highlights their shared commitment to contextualizing historical, social, and political influences, while revealing key distinctions in scope, methodology, and focus. All three methodologies analyze power dynamics, ideologies, and socio-political structures. However, they differ in their primary concerns—CDA examines how language and discourse reinforce or challenge power hierarchies, CHA explores historiographical biases and ideological influences in historical narratives, and CUT critiques urban spaces’ capitalist and neoliberal shaping. While CDA relies on linguistic and socio-linguistic tools to expose social inequalities in discourse, CHA takes a broader historiographical approach to uncover ideological and political influences in historical texts. CUT integrates urban geography, sociology, and political economy to analyze spatial justice and governance.

Despite their methodological differences, all three approaches share an emancipatory goal, challenging entrenched inequalities and advocating for more just interpretations of history, policy, and urban development. CDA and CUT actively contest social injustices, aiming for equitable discourse and urban transformation, while CHA provides a comparative perspective to understand how past narratives shape present realities. While each method can be interdisciplinary, CUT is inherently multidisciplinary, merging insights from urban studies and political economy. In contrast, CDA and CHA primarily draw from discourse analysis and historiography. By integrating these methodologies through critical synthesis, urban research can achieve greater analytical depth, bridging historical, linguistic, and socio-political perspectives to uncover the complex forces shaping contemporary urban environments.

5.2. From General Principles to Specific Urban Applications

This sub-section is on qualitative historical inquiry into the key principles of social sciences analysis and their applications in urban studies research. It shows how the principles of the seven elements in some social sciences studies are adapted and specialized within architecture, urban planning, and urban design practice. While the social sciences offer broad methodological and analytical frameworks, urban studies apply and modify these approaches to address specific architectural, urban planning, and urban design challenges. The seven fundamental elements discussed in history are based on social sciences principles, which help urban planners and designers to address specific urban challenges. This sub-section outlines these principles by identifying and categorizing 60 principles across the seven elements: 36 related to history-focused concepts and 24 associated with critical approaches (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Outline of 36 principles across history-focused concepts derived from interdisciplinary fields, including 18 for social sciences and 18 for urban studies. Source: the literature compiled by the authors.

Table 2.

Outline of 24 principles across critical approaches derived from interdisciplinary concepts, including 7 for social sciences and 17 for urban studies. Source: the literature compiled by the authors.

5.3. Consolidating the Previously Detailed Principles

A two-fold methodological framework that combines the principles discussed earlier in this section is presented here. It offers a structured framework for analyzing complex urban planning and design research challenges. The first part addresses the application of contextual analysis, demonstrating how to apply, analyze, develop, and evaluate contextual approaches from social sciences and their application in urban studies (critique, reframing, linking historical contexts to urban policies, adapting to contemporary visions, and redefining discourses). The second part focuses on reflected applications, outlining how to identify biases, analyze language’s role, and extract insights from social sciences, with urban studies examples demonstrating critiques, reframing, and contextual links to urban text. The following subsections organizes the 60 principles outlined in Table 1 and Table 2, derived from the four history-focused concepts—comprising 25 in social sciences and 35 in urban studies—into 22 overarching themes in two parts, and 24 from the three critical approaches.

5.3.1. First Part: Contextual Analysis from Social Sciences

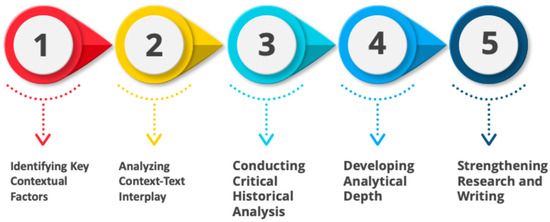

The first stage consolidates 25 principles from history-focused concepts and historical methods into 10 overarching themes based on a cross-sectional analysis of scholarly articles (2000–2024), as shown in Figure 6. This stage is further divided into two phases:

Figure 6.

Five stages of contextual critical historical analysis (CCHIA) framework. Source: the authors.

- -

- Step One: consolidate eight principles derived from 19 articles in social sciences, published across 17 journals between 2000 and 2024, into six overarching themes (see Supplementary B, Table S3).

- Analyze historical and social contexts to understand how they shape narratives, societal values, and contradictions, ensuring contextual integrity throughout research and interpretation [33,73,75,110,111,119];

- Incorporate stories, personal accounts, and historical actors’ viewpoints to create dynamic, human-centered interpretations of historical phenomena [30,73];

- Develop coherent, analytically rich narratives that link historical texts to socio-historical conditions and foster sophisticated reasoning and nuanced interpretations [3,75,103];

- Enhance critical thinking and qualitative analysis by teaching and employing contextualization as a skill supported by active learning strategies and interpretive validation [13,77];

- Adopt a multidisciplinary perspective to assess past policies, practices, and long-term consequences, integrating insights from diverse fields [31,78,79];

- Apply contextualization skills to foster critical engagement with historical sources, benefiting diverse learners and improving historical argumentation across educational settings [13,77].

- -

- Step Two: consolidate seven principles from 11 articles in social sciences (2000–2024) into four overarching themes (see Supplementary B, Table S3).

- Uncover hidden biases and power structures and critique how discourse reflects and perpetuates societal inequalities [54,115];

- Examine how language constructs social realities, shapes public perceptions, and influences approaches [84,85,86];

- Analyze texts as reflections of historical changes and compare historical trajectories to uncover structural patterns and societal transformations [45,87,116];

- Derive context-based insights into urban governance by connecting historical analysis with contemporary structural dynamics [46].

5.3.2. Second Stage: Reflected Applications in Urban Studies

The second stage reflected applications and focused on 35 principles related to the four history-focused concepts and three critical approaches, consolidated into twelve overarching steps based on a cross-sectional analysis of scholarly articles (2000–2024). This part is further divided into two phases:

- -

- Step Three: Consolidate eight principles from 17 urban studies articles published in 11 journals between 2000 and 2024 into six overarching themes (Supplementary B, Table S4).

- Interpret historical narratives to inform urban thought, connect historical analysis with urban innovation, and trace institutional origins and evolution to uncover long-term impacts on approaches [99,114,120].

- Analyze socio-political and cultural approaches embedded in urban discourses, balance global trends with local histories, and redefine narratives to amplify marginalized voices and promote equity [23,48,89,97].

- Explore historical and cultural contexts of urban policies, examine transformations in urban spaces, and integrate heritage and context into design innovations for inclusive urban practices [80,94,101,118].

- Adapt historical attention to current challenges by analyzing resilience strategies, learning from historical urban systems, and addressing everyday practices and resistance within marginalized power networks [48,102].

- Employ historical symbolism in problem-solving, connect socio-historical dynamics to innovative design strategies, and examine contextual forces shaping urban policies and governance approaches [98,99,105,108].

- Critique urban challenges by connecting historical precedents to governance strategies and evolving interpretations of urban heritage to promote justice-oriented and inclusive practices [80,104,113].

- -

- Step Four: a total of 18 principles from 12 urban studies articles published in six journals between 2000 and 2024 were similarly consolidated into six overarching themes (Supplementary B, Table S4).

- Expose imbalances in urban policies (housing and governance), critique socio-political structures perpetuating inequalities, and advocate for justice-oriented alternatives to neoliberal frameworks [47,49,88];

- Examine societal norms embedded in urban discourses, reframe narratives to prioritize equity, and redefine language to amplify marginalized voices, fostering inclusive urban practices [48,89,90];

- Explore the influence of historical and cultural factors on urban policies, trace the evolution of property regulations and planning practices, and link historical contexts to governance frameworks [92,94];

- Analyze governance structures shaped by historical contexts, examine policies for equitable urban development, and address informality and resistance within marginalized systems [48,91,93];

- Connect urban struggles to environmental justice, critique unequal impacts of climate policies, and advocate for integrated approaches linking social and environmental justice in governance [95,96];

- Assess the construction and evolution of urban discourses, focusing on their socio-political effects on marginalized communities. Analyze how these narratives influence inclusivity and perpetuate power structures, advocating for equitable redefinition to address systemic inequalities [48,89,90].

The 22 overarching themes above stress the significance of integrating historical analysis, critical thinking, narrative construction, and multidisciplinary approaches to create a proposed approach that enables researchers to delve deeper into historical phenomena, build convincing arguments, and address contemporary issues with greater insight.

6. Discussion: CCHIA Framework for Critical Synthesis in Urban Studies—Integrating Historical Contextual Analysis

This section introduces the Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry and Analysis (CCHIA) framework for critical synthesis in urban studies research. Through interpretive history, historical perspective, historical context, historical contextualization, Critical Discourse Analysis, Comparative Historical Analysis, and Critical Urban Theory, CCHIA provides an interdisciplinary framework beyond mere historical context. Unlike existing methods, CCHIA actively examines biases within historical narratives, revealing marginalized perspectives and fostering more nuanced interpretations.

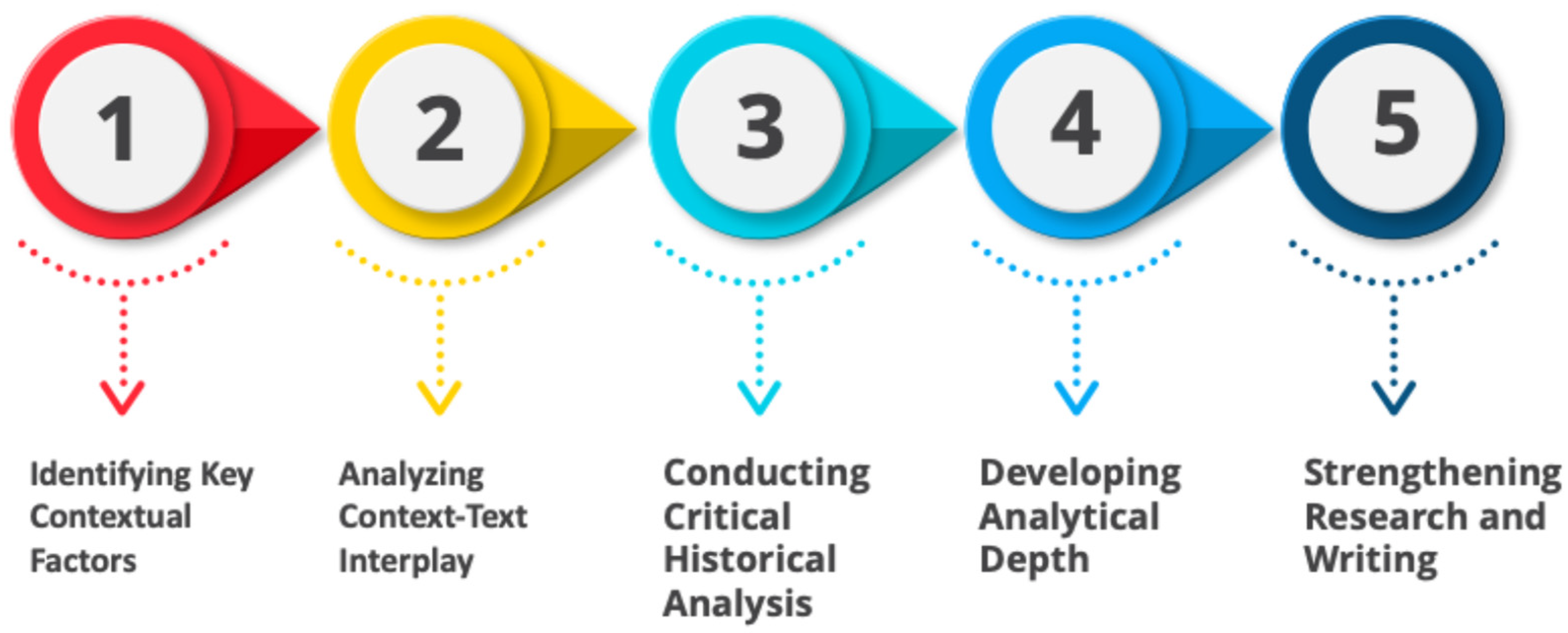

6.1. The Proposed CCHIA Framework: Consecutive Five-Stage and 26-Step Guidance Approach

To break down the Contextual Critical Historical Inquiry and Analysis (CCHIA) framework, a practical five-stage, 26-step guide was designed to help urban researchers weave historical insights and critical thinking into their work. Think of it as a roadmap for digging into the past to better understand today’s cities. By blending historical research with tough questions about power, inequality, and context, this framework aims to make urban studies more grounded, thoughtful, and impactful. In short, it is about putting history to work to create smarter, fairer cities. The framework guides researchers, as illustrated in Figure 6, through (1) identifying key contextual factors—historical and social contexts, (2) analyzing context–text interplay, (3) conducting a historical analysis to link past and present urban issues, (4) developing analytical depth—expanding multidisciplinary perspectives, and (5) strengthening research through context–text interplay.

By following the framework of the five stage and 26 guidance steps, researchers can develop a strong approach and acquire the tools to contend with urban issues critically. This framework offers two key benefits: Firstly, it encourages researchers to consider the complexity of urban paradigms by examining historical and contextual factors, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of urban issues. Secondly, the framework promotes critical thinking by urging researchers to question and analyze the facts, underlying factors, and narratives that shape urban realities. Below is a structured toolkit designed as a cumulative, step-by-step guide to help researchers systematically write their work using the provided insights and benefits.

6.1.1. Stage 1: Identifying Key Contextual Factors—Historical and Social Contexts

Start by investigating the “big why”—the policies, cultural shifts, or economic trends that shape urban issues (e.g., how past housing laws still influence gentrification today).

- Employ locational analysis to incorporate the spatial dimensions of urban phenomena;

- Identify critical urban phenomena (theories, movements, paradigms) and ensure that the data reflect historical integrity and societal relevance;

- Appreciate qualitative nuances by integrating historical actors’ narratives and contextual subtleties (e.g., local resistance to global policies);

- Evaluate the long-term consequences of historical policies, actors, and turning points on current urban frameworks;

- Trace the chronological evolution of theoretical components (pioneers, key transformations) to build coherent explanations;

- Balance global and local histories by analyzing how macro trends (e.g., neoliberalism) interact with micro-level cultural contexts;

6.1.2. Stage 2: Analyzing Context–Text Interplay

Explore how these forces—such as political decisions or economic pressures—interact with urban problems. Ask the following: Who gains? Who loses?

- Identify crucial urban phenomena (concepts, terminologies, paradigms) to specify historical foundations and ensure alignment with societal relevance (e.g., neoliberalism’s impact on housing policies);

- Derive context-based insights by tracing the chronological evolution of theoretical components, including pioneers (e.g., Henri Lefebvre) and key transformations (e.g., shifts from modernist to participatory planning);

- Redefine discourses equitably to dismantle systemic inequalities, prioritizing marginalized voices in policy critiques (e.g., reframing “slum” narratives to highlight informal community agency);

6.1.3. Stage 3: Conducting Critical Historical Analysis

Critically examine the past to expose hidden inequalities (e.g., how colonial planning still affects city layouts) and challenge one-sided stories about urban growth.

- Redefine discourses equitably to dismantle systemic inequalities, prioritizing marginalized voices in policy critiques (e.g., reframing “slum” narratives to highlight informal community agency);

- Incorporate historical actors’ perspectives through personal narratives and archival accounts (e.g., oral histories of displaced communities in gentrification studies);

- Critique urban challenges through historical precedents by linking past paradigms to present inequities (e.g., redlining’s role in contemporary housing disparities);

- Evaluate the long-term consequences of historical policies and actors, emphasizing marginalized contexts (e.g., enduring effects of highway construction on minority neighborhoods);

- Uncover embedded biases in societal urban realities by analyzing systemic imbalances (e.g., gendered public space design rooted in 19th-century norms);

- Strengthen research credibility by scrutinizing contradictions in historical narratives (e.g., “urban renewal” rhetoric vs. displacement outcomes);

6.1.4. Stage 4: Developing Analytical Depth—Expanding Multidisciplinary Perspectives

Bring insights from sociology, design, and history to ensure that diverse voices (like migrant communities’ experiences) shape solutions.

- Advance worldly reasoning by constructing precise arguments and coherent narratives (e.g., critiquing “trickle-down urbanism” through historical policy failures);

- Enhance qualitative analysis through interpretive validation, embedding contextual reasoning in discussions (e.g., validating informal settlement narratives against archival records);

- Link past transformations to present challenges by analyzing historical shifts (e.g., deindustrialization) and their impact on contemporary discourse (e.g., rust belt revitalization debates);

- Reshape narratives by integrating diverse perspectives, such as migrant communities’ oral histories, to reframe urban gentrification studies;

- Leverage multidisciplinary methodologies to dissect issues like urban gentrification (e.g., combining historical maps with demographic data);

- Uncover structural inequalities by assessing gaps between paradigms and practices (e.g., disparities in green space access rooted in racialized zoning);

6.1.5. Stage 5: Strengthening Research and Writing Through Context–Text Interplay

Use historical evidence to build credible arguments, reframe narratives, and show how language (like terms such as “urban renewal”) impacts policies and realities.

- Reframe narratives to balance text and historical–societal context, prioritizing actionable guidance (e.g., teaching contextualization skills over listing isolated principles);

- Promote thematically driven practices by integrating historical analysis with methodologies (e.g., pairing archival research with participatory mapping);

- Engage deeply with historical sources to refine arguments and enhance credibility (e.g., cross-referencing policy documents with grassroots testimonies);

- Analyze language’s impact on shaping urban phenomena (e.g., how terms like “urban renewal” mask displacement);

- Recognize language as a constructor of social realities (e.g., “resilience” discourses obscuring systemic vulnerabilities).

By applying these five stages and 26 guidance steps, researchers navigate a structured methodology that enhances the reliability of their findings. Additionally, the framework helps to bridge historical theory and contemporary urban practices, ensuring that their work is intellectually grounded and practically relevant. Researchers can now address contemporary urban challenges more effectively by analyzing how these paradigms intersect with their historical and spatial contexts.

6.2. Contribution, Novelty, and Added Value