Classifying Job Value Profiles and Employment Outcomes Among Culinary Arts Graduates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Job Values and Profiles

2.2. Job Value Profiles and Qualitative Employment Outcomes

3. Methods

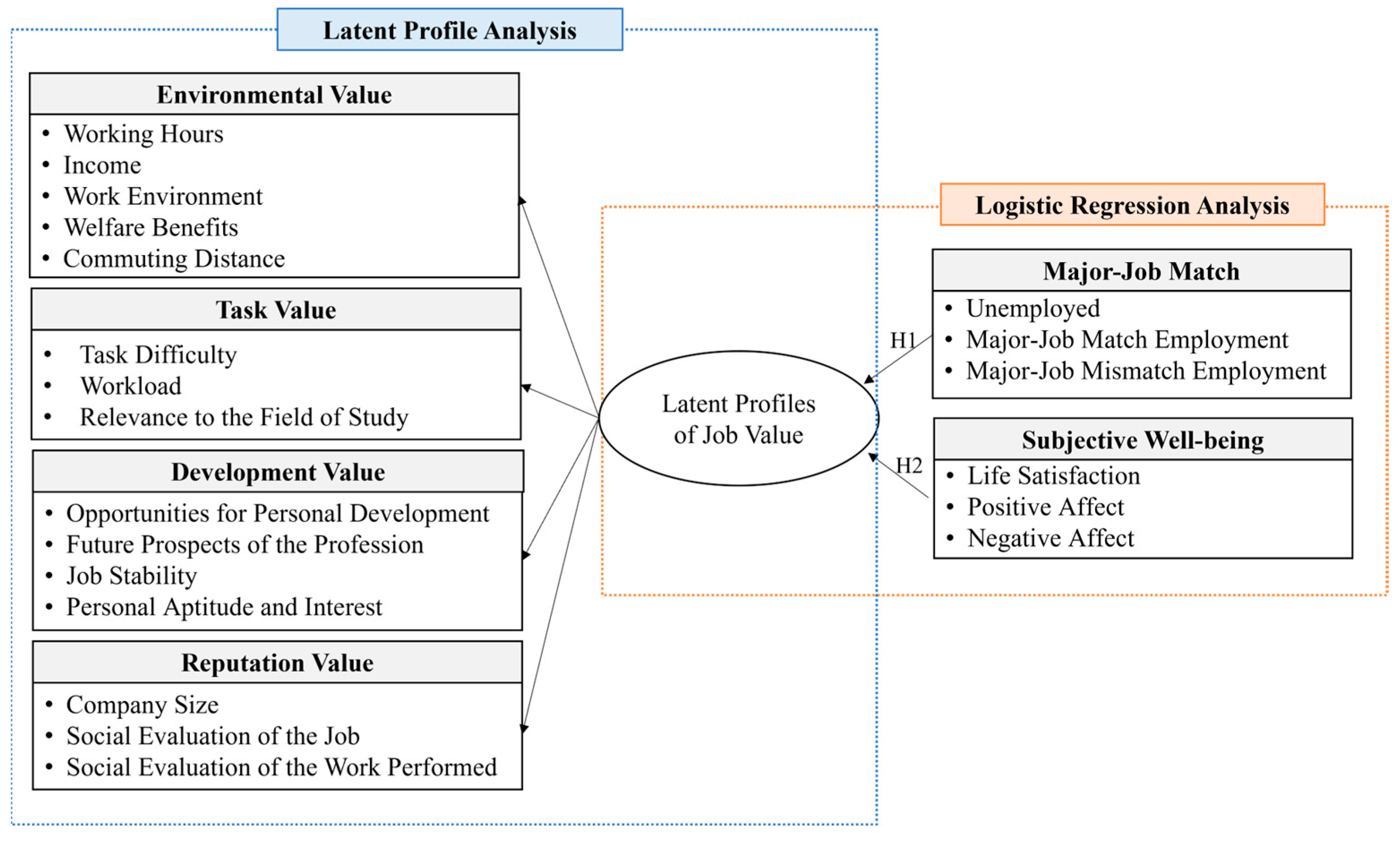

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Research Subjects

3.3. Measurement Tools

3.4. Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Measurement Tools

4.2. LPA on Job Values

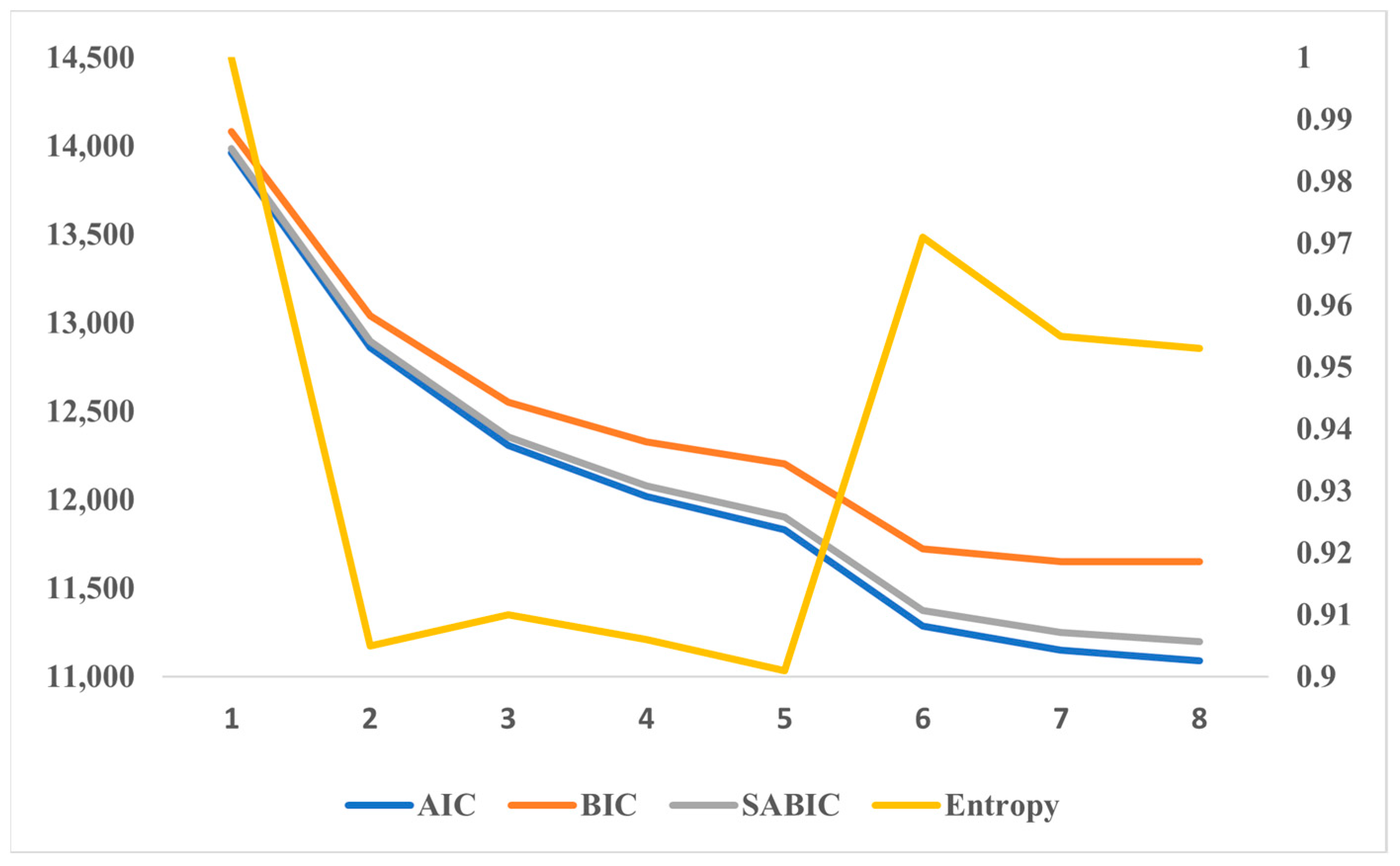

4.2.1. Model Fit Results Based on the Number of Profiles

4.2.2. Profile Characteristics Identified Through Z-Scores

4.3. Results of Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Maloni, M.; Hiatt, M.S.; Campbell, S. Understanding the work values of Gen Z business students. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.B.; Fuxman, L.; Mohr, I.; Reisel, W.D.; Grigoriou, N. “We aren’t your reincarnation!” workplace motivation across X, Y and Z Generations. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 42, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Employment and Labor. Ministry of Employment and Labor Employment Trend Survey for Youth in the First Half of 2024; Ministry of Employment and Labor: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. The Effects of Work-Life Balance on Turnover Intentions of Generation Y Employees: Focused on the Mediating Effect of Psychological Capital. Master`s Thesis, Busan National University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S.-W.; Kim, H.-C.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Lee, J.-T. What makes hotel chefs in Korea interact with Sns community at work? Modeling the interplay between social capital and job satisfaction by the level of customer orientation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tongchaiprasit, P.; Ariyabuddhiphongs, V. Creativity and turnover intention among hotel chefs: The mediating effects of job satisfaction and job stress. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasa, A.; Fabbricatore, C.; Ferraro, G.; Pozzulo, R.; Martino, I.; Liuzza, M.T. Work-Related Stress among Chefs: A Predictive Model of Health Complaints. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Han, H.; Law, R. Work environment and well-being of different occupational groups in hospitality: Job demand–control–support model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, T.K.; Min, K.C. Changes in work values of college graduates with culinary-related major. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2021, 27, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Manshoor, A.; Mohamad, N.H.; Idris, N.A.; Lenggogeni, S. Graduates dilemma: To be or not to be a chef. Environ. Behav. Proc. J. 2022, 7, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.K. The effects of generation MZ chefs’ perception of person-environment fit in a workplace on job satisfaction, work engagement and prosocial organizational behavior. J. Converg. Food Spat. Des. 2024, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Bong, J.H. The effects of person environment (organization, job, supervisor) fit on the job engagement and job performance: Focusing on moderating effects by kitchen and F&B. Foodserv. Ind. J. 2019, 15, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Y.; Buyruk, L. The effect of work value perceptions and person organization fit on job satisfaction of X and Y generation employees in hospitality businesses. J. Multidiscip. Acad. Tour. 2024, 9, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwak, D.Y.; Yoon, H.H. A study on the relationship between passion, commitment to a career choice and satisfaction in their major according to the work value subtypes of students majoring in the culinary. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2020, 26, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckenooghe, D.; Raja, U.; Butt, A.N.; Abbas, M.; Bilgrami, S. Unpacking the curvilinear relationship between negative affectivity, performance, and turnover intentions: The moderating effect of time-related work stress. J. Manag. Organ. 2017, 23, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, A.J.S.; Bujacz, A.; Gagné, M. Person-centered methodologies in the organizational sciences: Introduction to the feature topic. Organ. Res. Methods 2018, 21, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.K. Latent profiles and its predictors of work value in generation Z university students. J. Educ. Cult. 2024, 30, 233–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Wong, C.-S.; Zeng, G. Personality profiles for hospitality employees: Impact on job performance and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckenooghe, D.; De Clercq, D.; Raja, U. A person-centered, latent profile analysis of psychological capital. Aust. J. Manag. 2019, 44, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daljeet, K.N.; Bremner, N.L.; Giammarco, E.A.; Meyer, J.P.; Paunonen, S.V. Taking a person-centered approach to personality: A latent-profile analysis of the Hexaco Model of personality. J. Res. Personal. 2017, 70, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifan, V.A.; Pantea, M.F. The receptivity of younger generation Romanian employees to new technology implementation and its impact on the balance between work and life. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2023, 24, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busque-Carrier, M.; Ratelle, C.F.; Le Corff, Y. Linking work values profiles to basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 3183–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, C.N.; Nagar, D. The Role of Work Values in Job Choice Decision—An Empirical Study. Indian J. Manag. 2011, 4, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, B.; Zada, M.; Memon, K.R.; Ullah, R.; Khattak, A.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Araya-Castillo, L. Challenges and strategies for employee retention in the hospitality industry: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, E.D.; Cho, S.; Liu, J. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on work engagement in the hospitality industry: Test of motivation crowding theory. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-H.; Teng, C.-C. Intrinsic or extrinsic motivations for hospitality employees’ creativity: The moderating role of organization-level regulatory focus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 60, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavasileiou, E.; Lyons, S.; Shaw, G.; Georgiou, A. Work values in tourism: Past, present and future. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 64, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmans, J.; Wille, B.; Schreurs, B. Person-centered methods in vocational research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 118, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.G.; Jo, A.R. Classification in work values and the relationship between individual and workplace factors of youth employees with college graduates. J. Corp. Educ. Talent Res. 2022, 24, 165–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Gilal, F.G. Composition of motivation profiles at work using latent analysis: Theory and evidence. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Hirayama, H.; Takada, N.; Sugiyama, S.; Yamada, M.; Takahashi, M.; Toshi, K.; Asakura, K. Classification by nurses’ work values and their characteristics: Latent profile analysis of nurses working in Japanese hospitals. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Song, J.H. Work values: A latent class analysis of Korean employees. High. Educ. Ski. Work-Based Learn. 2022, 12, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.O.; Kim, E.B. Classification of vocational college graduates` job values and their relationships to job satisfaction. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2016, 35, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.P.; Lim, H.R. A study on the types of career values and influencing factors among middle and high school students through latent profile analysis. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2024, 43, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.J.; Park, T.Y. A study of factors influencing successful entry into the labor market for college graduates. J. Learn.-Centered Curric. Instr. 2024, 24, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.S.; Im, J.H.; Ahn, S.S. A study on the influencing contextual factors of college graduates on the initial employment outcomes in food service management program in South Korea. J. Employ. Career 2018, 8, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fernet, C.; Litalien, D.; Morin, A.J.S.; Austin, S.; Gagné, M.; Lavoie-Tremblay, M.; Forest, J. On the temporal stability of self-determined work motivation profiles: A latent transition analysis. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.M.; Chung, H.Y. Effects of the project-based AI education program on AI ethical consciousness and creative problem-solving skills using flipped learning. J. Res. Curric. Instr. 2021, 25, 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Lin, Z.; He, M.; Wong, I.A. The perils of hospitality internship: A growth curve approach to job motivation change. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, E.J. Analysis of Group Characteristics by Major-Job Match and Job Satisfaction Level of Youth Graduates: Focusing on Reason for Major Selection, Priority for Employment, Turnover Intention, Subjective Well-Being. J. Career Educ. Res. 2019, 32, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Cheung, M.; Leung, P.; He, X.; Li, X.; Huang, R. Major-to-employment mismatch in social work: A values-based framework explaining job-search decisions among Chinese graduates in Shanghai, China. Int. Soc. Work 2021, 64, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Seo, S.H. Effect of Millennials’s work value on their first tenure: Serial mediation effect of person-job fit and job satisfaction. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2021, 40, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busseri, M.A. Examining the structure of subjective well-being through meta-analysis of the associations among positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 122, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W. An empirical analysis of changes in occupational values in regional migration of the young population. Kore Local Adm. Rev. 2023, 37, 319–342. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. The effects of perceived service quality on repurchase intentions and subjective well-being of Chinese tourists: The mediating role of relationship quality. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.A.; Lee, H.R. The effects of work-life balance on the subjective well-being, job engagement, and presenteeism of hotel employee. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2019, 31, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Gordon, S.; Tang, C.-H. Momentary well-being matters: Daily fluctuations in hotel employees’ turnover intention. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.I.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, Y.T. An empirical study on airline cabin crew’s work engagement and the possibility of presenteeism: How these concepts are affected by work-life balance. J. Aviat. Manag. Soc. Korea 2019, 17, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörös, Z. The role of work values in the subjective quality-of-life of employees and self-employed adults. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 15, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayar, S.; Urbanaviciute, I.; Massoudi, K.; Rossier, J. The role of personality profiles in the longitudinal relationship between work–related well–being and life satisfaction among working adults in Switzerland. Eur. J. Personal. 2020, 34, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Herrmann, A.; Nagy, N.; Spurk, D. All in the name of work? Nonwork orientations as predictors of salary, career satisfaction, and life satisfaction. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A.; Wang, M.; Valero, D.; Kauffeld, S. Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, J.K.; Magidson, J. Technical Guide for Latent GOLD 5.0: Basic, Advanced, and Syntax; Statistical Innovations Inc.: Belmont, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, K.S.; Williams, N.A.; Parra, G.R. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosmer, D.W., Jr.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock-Yowell, E.; Reed, C.A.; Mohn, R.S.; Galles, J.; Peterson, G.W.; Reardon, R.C. Neuroticism, negative thinking, and coping with respect to career decision state. Career Dev. Q 2015, 63, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnia, F.; Nafukho, F.M.; Petrides, K.V. Predicting career decision-making difficulties: The role of trait emotional intelligence, positive and negative emotions. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unanue, W.; Gómez, M.E.; Cortez, D.; Oyanedel, J.C.; Mendiburo-Seguel, A. Revisiting the link between job satisfaction and life satisfaction: The role of basic psychological needs. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgellis, Y.; Lange, T. Traditional versus secular values and the job–life satisfaction relationship across Europe. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Researcher | Subjects | Profile Types | Measurement Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jung [17] | Generation Z College Students | Value-Diminished, Value-Exploring, Value-Elevated | Achievement, Diversity, Autonomy, etc. (13 items in total) |

| Park and Jo [29] | College graduates under 39 years old | Overall Low-Recognition, Stable Reward-Seeking, Value-Contemplation, Overall Emphasis, Stability-Oriented | Profiles reveal significant differences in job satisfaction and preferences. |

| Chen et al. [30] | Chinese Workers | Dominant, High-Midrange, Low-Midrange, Intrinsic Motivation-Minor, Intrinsic Motivation-Dominant | This study consists of 29 items and four dimensions: external motivation, intrinsic motivation, introjection motivation, and identification motivation. |

| Hara et al. [31] | Nurses | Self-Oriented type, Low Type, Medium-Low Type, Medium-High Type, High Type | Intrinsic work values were assessed with four items (e.g., work autonomy and growth), extrinsic work values with two items (e.g., job security and income), social work values with five items (e.g., contributing to society), and prestige work values with three items (e.g., authority and influence). |

| Lee et al. [32] | Korean Workers | Seeking Job Security and Income, Seeking Aptitude/Interest, Job Security, and Income, Seeking Balanced Values rather than Income, Income-oriented, Seeking Self-fulfillment, Job Security, and Income | Measured with six factors: job reputation, job security, income, aptitude/interest, self-fulfillment, and career prospects. |

| Ryu and Kim [33] | Graduates of 2-year or 3-year colleges | All-Values Cherishing type, Non-Cherishing type, Reputation/Environment/Growth Cherishing type, Environment/Growth Cherishing type | 15 items from GOMS (e.g., labor income, working hours, etc.) |

| Hong and Lim [34] | Employees | Social Impact-Focused Type, Overall High Value-Seeking Type, Reward Preference Type, Low Social Impact-Seeking Type | 12 items (e.g., wages, honor, social contribution, etc.) |

| Measurement Items | Mean ± S.D. | Minimum | Maximum | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 4.31 ± 0.69 | 2 | 5 | −0.603 | −0.39 |

| Working Hours | 4.25 ± 0.69 | 1 | 5 | −0.621 | 0.415 |

| Personal Aptitude and Interest | 4.29 ± 0.73 | 2 | 5 | −0.634 | −0.481 |

| Relevance to the Field of Study | 3.77 ± 1.07 | 1 | 5 | −0.751 | 0.0891 |

| Task Difficulty | 3.68 ± 0.83 | 1 | 5 | −0.185 | 0.0278 |

| Workload | 3.80 ± 0.79 | 1 | 5 | −0.102 | −0.415 |

| Opportunities for Personal Development | 4.18 ± 0.74 | 1 | 5 | −0.539 | −0.0671 |

| Future Prospects of the Profession | 4.20 ± 0.74 | 2 | 5 | −0.54 | −0.396 |

| Job Stability | 4.23 ± 0.75 | 2 | 5 | −0.511 | −0.687 |

| Work Environment | 4.22 ± 0.71 | 2 | 5 | −0.474 | −0.464 |

| Welfare Benefits | 4.14 ± 0.74 | 1 | 5 | −0.616 | 0.482 |

| Company Size | 3.40 ± 0.97 | 1 | 5 | −0.314 | 0.027 |

| Commuting Distance | 3.87 ± 0.87 | 1 | 5 | −0.276 | −0.612 |

| Social Evaluation of the Job | 3.53 ± 0.93 | 1 | 5 | −0.516 | 0.517 |

| Social Evaluation of the Work Performed | 3.50 ± 0.92 | 1 | 5 | −0.499 | 0.501 |

| Life Satisfaction | 5.10 ± 1.21 | 1.33 | 7 | −0.266 | −0.467 |

| Positive Affect | 4.88 ± 1.24 | 1 | 7 | −0.224 | −0.267 |

| Negative Affect | 3.71 ± 1.37 | 1 | 7 | 0.147 | −0.493 |

| Classes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LogLik | −6951.0 | −6383.5 | −6091.8 | −5930.5 | −5821.3 | −5533.5 | −5449.1 | −5401.9 |

| AIC | 13,962.0 | 12,858.9 | 12,307.5 | 12,017.1 | 11,830.5 | 11,287.0 | 11,150.1 | 11,087.8 |

| BIC | 14,081.0 | 13,040.9 | 12,552.8 | 12,325.6 | 12,202.4 | 11,722.1 | 11,648.6 | 11,649.5 |

| SABIC | 13,986.0 | 12,894.9 | 12,356.1 | 12,078.2 | 11,904.1 | 11,373.1 | 11,248.8 | 11,199.0 |

| Entropy | 1.000 | 0.905 | 0.910 | 0.906 | 0.901 | 0.971 | 0.955 | 0.953 |

| BLRT | 1135.3 * | 583.4 * | 322.4 * | 218.6 * | 575.5 * | 168.9 * | 94.3 * | |

| 1 | 386 (100.0) | 282 (73.1) | 79 (20.5) | 83 (21.5) | 67 (17.4) | 52 (13.5) | 48 (12.4) | 48 (12.4) |

| 2 | 104 (26.9) | 237 (61.4) | 59 (15.3) | 60 (15.5) | 34 (8.8) | 34 (8.8) | 34 (8.8) | |

| 3 | 70 (18.1) | 180 46.6) | 58 (15.0) | 52 (13.5) | 45 (11.7) | 45 (11.7) | ||

| 4 | 64 (16.6) | 171 44.3) | 151 (39.1) | 50 (13.0) | 48 (12.4) | |||

| 5 | 30 (7.8) | 71 (18.4) | 105 (27.2) | 105 (27.2) | ||||

| 6 | 26 (6.7) | 75 (19.4) | 56 (14.5) | |||||

| 7 | 29 (7.5) | 24 (6.2) | ||||||

| 8 | 26 (6.7) |

| Job Value Items | Mean | z Score | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Environmental Value | Income | 4.75 | 3.11 | 4.81 | 4.42 | 4.13 | 3.59 | 1.42 | −1.01 | 1.50 | 0.93 | 0.50 | −0.30 |

| Working Hours | 4.79 | 3.11 | 4.67 | 4.35 | 3.98 | 3.47 | 1.47 | −1.02 | 1.30 | 0.82 | 0.28 | −0.48 | |

| Work Environment | 4.79 | 2.96 | 4.77 | 4.35 | 3.81 | 3.25 | 1.47 | −1.24 | 1.45 | 0.82 | 0.02 | −0.81 | |

| Welfare Benefits | 4.75 | 2.89 | 4.54 | 4.29 | 3.87 | 3.27 | 1.42 | −1.34 | 1.10 | 0.73 | 0.11 | −0.78 | |

| Commuting Distance | 4.67 | 3.09 | 3.87 | 3.90 | 3.67 | 3.29 | 1.30 | −1.04 | 0.11 | 0.16 | −0.18 | −0.75 | |

| Task Value | Task Difficulty | 4.48 | 2.97 | 3.60 | 3.73 | 3.31 | 3.08 | 1.02 | −1.22 | −0.29 | −0.09 | −0.72 | −1.06 |

| Workload | 4.56 | 2.94 | 3.79 | 3.88 | 3.38 | 3.08 | 1.13 | −1.27 | −0.01 | 0.13 | −0.61 | −1.06 | |

| Relevance to the Field of Study | 4.33 | 3.01 | 3.79 | 3.92 | 3.48 | 3.15 | 0.79 | −1.17 | −0.01 | 0.19 | −0.46 | −0.96 | |

| Developmental Value | Opportunities for Personal Development | 4.67 | 2.92 | 4.40 | 4.42 | 3.85 | 3.23 | 1.30 | −1.30 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.08 | −0.84 |

| Future Prospects of the Profession | 4.75 | 3.03 | 4.58 | 4.37 | 3.92 | 3.39 | 1.42 | −1.13 | 1.16 | 0.85 | 0.19 | −0.60 | |

| Job Stability | 4.81 | 3.06 | 4.77 | 4.42 | 3.81 | 3.35 | 1.50 | −1.08 | 1.45 | 0.93 | 0.02 | −0.66 | |

| Personal Aptitude and Interest | 4.73 | 3.07 | 4.56 | 4.54 | 4.10 | 3.46 | 1.39 | −1.08 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 0.45 | −0.50 | |

| Reputation Value | Company Size | 4.35 | 2.93 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 3.10 | 2.90 | 0.82 | −1.29 | −0.69 | −0.69 | −1.03 | −1.33 |

| Social Evaluation of the Job | 5.00 | 2.98 | 2.98 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 2.94 | 1.79 | −1.21 | −1.21 | 0.30 | −1.18 | −1.27 | |

| Social Evaluation of the Work Performed | 4.90 | 2.98 | 3.00 | 3.92 | 3.02 | 2.97 | 1.64 | −1.21 | −1.18 | 0.19 | −1.15 | −1.23 | |

| Dependent | Predictor | Estimate | SE | Z | Odds Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile 2 | Gender | Female | −0.618 | 0.495 | −1.248 | 0.539 |

| Type of college | 4 year college | −0.532 | 0.600 | −0.887 | 0.587 | |

| Major–job match | mismatched | −0.984 | 0.637 | −1.545 | 0.374 | |

| matched | −1.260 | 0.587 | −2.148 * | 0.284 | ||

| Subjective well-being | Life satisfaction | −0.039 | 0.253 | −0.152 | 0.962 | |

| Positive affect | 0.068 | 0.231 | 0.293 | 1.07 | ||

| Negative affect | 0.414 | 0.189 | 2.193 * | 1.513 | ||

| Profile 3 | Gender | Female | 0.352 | 0.415 | 0.847 | 1.421 |

| Type of college | 4 year college | 0.311 | 0.461 | 0.675 | 1.365 | |

| Major–job match | mismatched | −1.753 | 0.641 | −2.736 ** | 0.173 | |

| matched | −0.942 | 0.518 | −1.817 | 0.39 | ||

| Subjective well-being | Life satisfaction | −0.309 | 0.239 | −1.294 | 0.734 | |

| Positive affect | 0.316 | 0.221 | 1.425 | 1.371 | ||

| Negative affect | 0.417 | 0.170 | 2.449 * | 1.517 | ||

| Profile 4 | Gender | Female | 0.644 | 0.342 | 1.881 | 1.903 |

| Type of college | 4 year college | −0.016 | 0.394 | −0.040 | 0.984 | |

| Major–job match | mismatched | −0.964 | 0.514 | −1.876 | 0.381 | |

| matched | −0.439 | 0.458 | −0.960 | 0.644 | ||

| Subjective well-being | Life satisfaction | −0.588 | 0.204 | −2.875 ** | 0.556 | |

| Positive affect | 0.312 | 0.188 | 1.661 | 1.367 | ||

| Negative affect | 0.078 | 0.144 | 0.537 | 1.081 | ||

| Profile 5 | Gender | Female | −0.102 | 0.394 | −0.260 | 0.903 |

| Type of college | 4 year college | 0.338 | 0.433 | 0.780 | 1.402 | |

| Major–job match | mismatched | −1.481 | 0.595 | −2.490 * | 0.227 | |

| matched | −0.717 | 0.501 | −1.431 | 0.488 | ||

| Subjective well-being | Life satisfaction | −0.492 | 0.225 | −2.188 * | 0.612 | |

| Positive affect | 0.306 | 0.208 | 1.472 | 1.358 | ||

| Negative affect | 0.419 | 0.161 | 2.597 ** | 1.521 | ||

| Profile 6 | Gender | Female | 0.423 | 0.512 | 0.827 | 1.527 |

| Type of college | 4 year college | −0.913 | 0.714 | −1.279 | 0.401 | |

| Major–job match | mismatched | −0.746 | 0.802 | −0.930 | 0.474 | |

| matched | 0.183 | 0.682 | 0.268 | 1.201 | ||

| Subjective well-being | Life satisfaction | −0.973 | 0.311 | −3.132 ** | 0.378 | |

| Positive affect | −0.018 | 0.285 | −0.065 | 0.982 | ||

| Negative affect | −0.028 | 0.226 | −0.125 | 0.972 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Na, T.-K.; Han, S. Classifying Job Value Profiles and Employment Outcomes Among Culinary Arts Graduates. Societies 2025, 15, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15030066

Na T-K, Han S. Classifying Job Value Profiles and Employment Outcomes Among Culinary Arts Graduates. Societies. 2025; 15(3):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15030066

Chicago/Turabian StyleNa, Tae-Kyun, and Saem Han. 2025. "Classifying Job Value Profiles and Employment Outcomes Among Culinary Arts Graduates" Societies 15, no. 3: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15030066

APA StyleNa, T.-K., & Han, S. (2025). Classifying Job Value Profiles and Employment Outcomes Among Culinary Arts Graduates. Societies, 15(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15030066