Abstract

Vocational training aims to facilitate the acquisition of a series of professional skills by students, specified through a series of Learning Outcomes described in the official curricula. This requires teachers to adopt a wide variety of teaching methods and resources that allow for an appropriate match between learning styles and teaching styles, covering the diversity of styles present among students, to facilitate the achievement of all students. The students’ perception of the usefulness of the teaching resources used is an important factor in achieving this balance, and as a guide for better planning the methods and resources to be used in the classroom. This exploratory case study investigates students’ perceptions of the usefulness of different teaching resources and methods used to achieve the learning outcomes set out in the subject of water network installation and commissioning in an intermediate vocational training programme for water networks and treatment plants. The data was collected through a survey and individual interviews. The results of the research show that, despite a predominant preference for resources and methods associated with practical activities, as might be expected in vocational training, a significant heterogeneity in the attribution of usefulness to resources within the group was identified, which could be linked to different learning styles. Moreover, different dimensions emerged regarding the perception of usefulness that could better guide course planning towards a balanced diversification of methods and resources.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Concept of Professional Competence in the Context of the Spanish Vocational Education and Training System

One of the main objectives of the Spanish vocational training system, established in Organic Law 3/31 March 2022, is to ensure the qualification of individuals for the exercise of professional activities. This involves promoting the acquisition, consolidation, and expansion of both basic and professional competences that guarantee access to employment, continuity in the labour market, professional progression, and adaptation to the challenges posed by increasingly complex work environments. Within this framework, the law conceptualises professional competence as the body of knowledge and skills that enable individuals to carry out professional activities in line with production and employment requirements [1]. In accordance with this definition, and for the purposes of this study, the usefulness of a teaching resource is understood as its ability to help vocational training students acquire the knowledge and skills required to perform the activities linked to the professional competences established in the official curriculum of the corresponding qualification.

1.2. Learning Outcomes and Curriculum Structure

The required professional profiles are defined by a set of competencies. These competencies form the basis for various vocational training syllabi. Each syllabus is linked to specific training objectives aimed at helping learners acquire these competencies. The training objectives are achieved through subjects typically called professional modules. These modules focus on a specialised area of knowledge and cover a series of Learning Outcomes (LOs) outlined in the official curricula. The Vocational Training Act itself defines Learning Outcomes as “a basic element of the curriculum that describes what a student is expected to know, understand and be able to do, associated with an element of competence and which guides the rest of the curriculum elements, including the assessment criteria that allow the verification of the students’ achievements”. Thus, the LOs and their assessment criteria become the central element around which educational intervention is designed.

Within this general framework, the specific training framework for technical professionals in the urban water sector is defined by Royal Decree 114/17 February 2017, establishing the qualification of Technician in Water Networks and Treatment Plants, and Royal Decree 113/17 February 2017, establishing the qualification of Senior Technician in Water Management, which set out the basic aspects of the respective curricula.

1.3. Methodologies and Teaching Strategies

The various teaching and learning activities must be designed to ensure that all students acquire all the LOs required for qualification, using specific technologies, content, methodologies, materials, and resources of various types, along with a strong practical focus to prepare students for the labour market in a specific field. There is a wide range of teaching and learning strategies that must be consistent with each other [2]. However, there is no ideal teaching method, being that each method is good for certain teaching-learning situations. In consequence, the exclusive use of a single method hinders the achievement of the diverse objectives that teachers and students seek to achieve. Nevertheless, in training focused on the acquisition of professional skills, active teaching methodologies take on special relevance compared to traditional instruction [3], although the use of active methodologies does not exclude the use of direct instruction that is complementary and necessary alongside the former [4]. Although there is an extensive body of literature that points out the potential benefits of applying the Project-Based Learning (PBL) approach [5,6,7], which has great potential in facilitating the acquisition of skills in technical areas [8], its application is not without risks [9,10,11]; thus, an exhaustive analysis of its implications is required in all the dimensions that may be affected: regulatory aspects, teaching coordination, spaces, programming, technical and economic resources, planning its implementation from reflection, and adapting it to a particular Vocational Education and Training (VET) program [12].

1.4. Teaching Resources and Materials

Several authors have addressed the definition and role of teaching resources and materials in educational processes. The terms teaching resources and didactic materials are sometimes used as synonyms [13] and, at other times, as differentiated concepts considering the term resource to be broader, as it encompasses the notion of material [14], or establishing a clear distinction considering educational resources as any material used for training purposes or to support teaching activities, while didactic materials are those specifically designed to facilitate teaching and learning processes. Both, however, share key functions such as informing, guiding, training, motivating, simulating, and fostering expression and creativity, facilitating connections between theoretical content and practical learning. For these resources to be effective, they must be aligned with learning objectives, curricular content, student characteristics, and the pedagogical strategies in which they are embedded. Thus, the didactic materials used serve as mediators between teaching and learning, and their relevance depends on their capacity to facilitate the achievement of the intended learning objectives. Learning processes are always mediated by the use of some type of didactic material, which, in turn, conditions the way in which students learn [15,16,17].

The wide variety of resources available includes both printed materials (such as books, manuals, teaching guides, and lecture notes) and digital resources (virtual learning platforms, interactive videos, simulators, or applications). Despite the increasing prominence of ICT, lecture notes prepared by teachers remain essential in disciplines that require a strong theoretical foundation. This is particularly the case in water management training programmes, which are highly multidisciplinary and combine knowledge from hydraulics, electrical engineering, and civil engineering, together with practical procedures, such as pipe installation, motor maintenance, or welding. In this context, specialised technical manuals become indispensable resources in vocational training, as they provide precise and detailed information.

In the connection between knowledge, procedures, and skills in vocational training, it is particularly necessary to use physical technical resources and equipment in workshop spaces where students use real tools, machinery, equipment, instruments, and materials that simulate working conditions as a means of acquiring professional skills by integrating knowledge and abilities. In the urban water field, students must know and understand pressure drops in a pipe and the characteristic curves of a hydraulic pump, but they must also know how to select the right equipment and assemble and connect pipes, valves, pumps and their hydraulic and electrical connections and all the accessories necessary for the proper functioning of the installation, as well as how to take measurements for testing, commissioning and maintenance. Therefore, in addition to using notes, manuals, and videos, this context requires specific resources (pumps, valves, cutting machinery, pipes, etc.) that make sense through diverse, progressive, and varied teaching methods.

The methods and resources used require action on the part of the teacher (explanation, tutoring, support, assessment, etc.) and the students (study, reading, use of materials and equipment, reflection, synthesis, creation of various products, etc.).

1.5. Research Motivation and Study Aim

During the educational intervention, questions arise that invite us to delve deeper into the relative effectiveness of the activities carried out, reflect on the academic results observed, and investigate how each of the students is learning to identify possible ways to improve the processes developed and the results obtained. “Based on practice, teachers ask themselves questions that may have various purposes, such as better understanding the subjects participating in an educational activity, identifying tensions that hinder the proposed achievements, learning how certain materials are used, identifying how a particular aspect of the curriculum is implemented, and seeking strategies to improve educational practice, among other possibilities. These questions arise from our interest and curiosity about a particular aspect of the educational phenomenon; they also have an intentionality, as teachers aim to contribute in some way to understanding or improving this educational phenomenon” [18] (p. 8).

Thus, the need for this research arises from the need to increase knowledge on how intermediate VET students perceive the acquisition of professional skills, that is, their learning. This knowledge can guide future interventions to improve current educational practices. A large part of educational research should be carried out from a practical perspective, promoting the research role of teachers involved in science education, in close collaboration with university lecturers, as this would allow for providing a basis for the development of teaching resources, curricular approaches and assessment procedures that support innovation in teaching practice” [19] (p. 86).

In response to the question: What is the perception of first-year intermediate VET students studying “water networks and treatment plants” of the usefulness of the different teaching resources used to address a specific LO of the official curriculum included in the module on “water networks assembly and commissioning”? The aim of the study was to ascertain the perception of first-year intermediate VET students of the relative usefulness for their learning of the different didactic materials used during the course to achieve the LOs of the module on the “assembly and commissioning of water networks”.

Educational research in the field of vocational training in Spain is scarce, and even more scarce is research led by the teachers themselves, among other reasons, due to the lack of practical and real research proposals on topics that teachers encounter in the classroom [20,21].

This study is part of the research work within the framework of the thesis “Test bench as a collaborative teaching resource for the integrated acquisition of skills in vocational training programmes in the field of the urban water cycle” within the PhD programme, Water and Sustainable Development at the University Institute of Water and Environmental Sciences of the University of Alicante.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The group under study is a group of students enrolled in the first year of the intermediate vocational training course in water treatment networks and stations at the IES Beatriu Fajardo de Mendoza in Benidorm (Spain). The group consists of eight male students aged between 17 and 27 from families with an average socioeconomic status and diverse educational backgrounds (baccalaureate, compulsory secondary school, or basic VET). None of the students has been diagnosed with any educational support needs at previous stages. All of them live in the region where the centre is located.

It should be noted that, unfortunately, this small number of students is representative of the number of students enrolled in the intermediate degree in water networks in Spain despite the fact that there is a high demand for technicians in the sector with an employability that reaches 50% in their first year after obtaining the degree and 70% in the third year [22]. In Spain, there are only 27 educational centres that teach this degree. According to the enrolment data of the Spanish Ministry of Education, in the 2023-2024 academic year, only 111 students graduated, of which only 10 were girls, and during that academic year, a total of 473 students were enrolled, of which 442 were boys and 31 girls. (Source: https://www.educacionfpydeportes.gob.es/servicios-al-ciudadano/estadisticas/no-universitaria/alumnado/fp.html, accessed on 15 October 2025). If we assume that they are distributed approximately equally between first and second year, we will obtain an average of 8.75 first-year students per school.

The researcher in charge of the study is also the group’s tutor, having served as a tutor for the first year of the intermediate vocational training course in water networks and treatment plants and taught the module on the “assembly and commissioning of water networks” for four consecutive years. Such a dual role (instructor and researcher) may raise concerns regarding rigorous approaches in technical and methodological terms, especially since data collection and interpretation are paramount to meet the objectives of the study. On the contrary, dealing with such small groups becomes an advantage when performing action research as a close relation of confidence is established among the students and between the group and the tutor, and, furthermore, the students can meet second-year students and exchange comments on any issue they find of interest. Different aspects contribute to the development of a relation of confidence. The development of the module included 7 h of practical and theoretical activities per week, as well as occasional visits to the facilities of companies in the sector and occasional talks by technicians from companies organised by the tutor. The revisions of theoretical exams and practical work were carried out personally with each student to provide feedback aimed at the individualised improvement of learning. The tutor identified the type of company and activity that best suited each student after discussing their circumstances with them, so that they can carry out their internship period in the company. All the learning-teaching activities involved in the study were designed ad hoc by the tutor; thus, the preference shown by students for one resource or another could not imply intentions to please the tutor with their responses. In this context, opinions, ideas, feelings, requests, or complaints were raised freely and always heard and discussed. In a student-centred learning approach, letting the students be part of the processes to improve their learning made sense and, in turn, motivated them.

The group was informed at the beginning of the year-long course about the contents, the planning of the course, and the evaluation criteria and grading system. The grades corresponding to the learning outcomes considered in this study fall in the first term of the course. Furthermore, course grades were given at the end of the second term before the interviews and the survey were carried out to make it clear that there could not be any connection between the grades and the information obtained through the research activities. Participation was absolutely voluntary. The survey was anonymous, and no personal data from the interviews was recorded, nor were the interviews themselves recorded.

From the technical perspective, having worked as a Chemical Engineer for different companies in the field of water and wastewater treatment and management for 20 years before starting the position as VET teacher allowed for gaining a deep insight into the technical aspects of the competences taught and the importance of technicians knowing “how” to do things and “why” things are performed in a particular way, that is, skills and knowledge.

From a methodological perspective, part of the professional experience of the main researcher was devoted to research in the field of wastewater and sludge treatment in a Technological Institute; such experience in the field of experimental sciences could be misleading if applied to the present study related to social sciences. To face this circumstance, an expert professor from the Department of Developmental Psychology and Didactics of the University of Alicante collaborated in this study. Furthermore, the study is part of the research carried out within a thesis under the PhD programme, Water and Sustainable Development, at the University Institute of Water and Environmental Sciences of the University of Alicante, which helps to shape and perform the study more accurately.

2.2. Method

As it is limited to a group, a specific educational centre, and a specific academic year, the present study constitutes a case study. “In education, a classroom can be considered a case, just like a particular form of teacher intervention or a teaching programme” [23] (p. 311). It can be considered a study within the framework of action research because it is “a type of applied research that is carried out primarily by the people who work in a given context—for example, the teachers or educators of a school—to critically analyse their own performance in order to introduce changes to improve it in that context, without necessarily expecting the research to contribute to generalising the knowledge acquired beyond the framework in which it was generated” [24] (p. 21). The goals of action research are to improve and understand a particular educational practice [25]. Action research represents a form of intervention considered by some authors to follow mixed designs, as they normally collect quantitative and qualitative data and move simultaneously between the inductive and deductive frameworks. The mixed research route intertwines the quantitative and qualitative routes and mixes them through the collection and analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data, as well as their integration and joint discussion, to make inferences from all the information collected and achieve a greater understanding of the phenomenon under study [26]. The present study combines a qualitative approach with a descriptive and cross-sectional quantitative approach. Qualitative in that it seeks to interpret, understand, or transform, based on the perceptions and meanings attributed by the protagonists, delving deeper into the study of a case [27]. From the quantitative perspective, exploratory studies serve to obtain information about the possibility of carrying out a more complete and in-depth investigation regarding a particular context, identify promising concepts or variables to investigate, establish priorities for future studies, or suggest statements, hypotheses, and postulates [26].

In summary, this study is conceived as an exploratory case, a starting point from an action research approach to know the perception of students about the resources and means used and to incorporate this factor as an element of improvement in the design and planning of educational intervention in vocational training.

Two important concepts in the evaluation of the quality of research results are external validity (possibility of generalising the results to other populations or situations similar to the one studied), and internal validity (possibility of making correct inferences about the subjects examined), which depends on the fidelity with which the observations reflect the phenomenon under study and implies a measurement free of bias. Unlike what happens in a purely quantitative study, where it is easier to determine its quality through these validity criteria, in qualitative studies, this interpretation is more complex, since the methodology, the type of information, and the types of research questions differ in their nature, and aspects, such as external and internal validity, acquire other meanings. There are different proposals to address the rigour of qualitative studies, on one hand, from a positivist perspective through the aforementioned concepts of external and internal validity along with reliability and objectivity, typical of quantitative approaches, and, on the other hand, through the consideration of other factors parallel to the previous ones but associated with the qualitative field such as credibility, transferability, dependency, or confirmability. Other authors propose criteria of rigour associated with concepts, such as authenticity, fairness, and empowerment [27,28,29]. In the evaluation of the quality of a qualitative study, characteristics such as the relevance of the research question, its clarity, the theoretical basis, the clear and complete description of how the research was carried out, and the way in which the data were collected and analysed constitute markers that give an idea of the strengths and weaknesses of the study [30]. From the qualitative perspective, the possibility of generalising the results obtained in a given context to another, whose meaning is similar to that of the context studied, is based on what is called transferability, which can only occur from the rich and in-depth description of each phenomenon in its context, and is not based on the number of cases studied [31]. The case study described here does not intend to generalise its results, but a high degree of transfer can be attributed to it. We understand that part of them or their essence can be applied in other contexts, being able to provide guidelines to have a general idea of the problem studied and the possibility of applying certain solutions in another environment. In this sense, the environment, the participants, the materials, the time of the study, and the roles of the researchers have been fully described; the group under study is, in number and gender, representative of the typical group of students following this training, and the learning outcomes are those prescribed by regulations, so they remain unchanged over time and for all centres in Spain. All this gives rise to replicability and continuity aspects of the study with successive cohorts of students.

The general competence of the intermediate degree consists of “Assembling, operating and maintaining water networks, as well as operating and maintaining water treatment plant equipment and facilities, applying current regulations, quality protocols, safety and occupational risk prevention protocols, ensuring their functionality and respect for the environment”. The curriculum for this qualification includes, among others, the module on Assembly and commissioning of water networks, which contributes to the achievement of the general competence through the acquisition of the LOs that enable the student to:

- LO1 Prepare work plans for the assembly of water supply networks, selecting the work procedures from the corresponding project.

- LO2 Draw up work plans for the assembly of water sanitation networks, selecting the working procedures from the corresponding project.

- LO3 Carry out assembly operations for water supply and sanitation networks, interpreting technical documentation and applying established work procedures.

- LO4 Carry out pre-commissioning checks on water supply and sanitation networks, identifying the procedures specified in technical documentation.

- LO5 Prepare commissioning and operating procedures for water supply and sanitation networks, following the relevant protocols.

- LO6 Carry out commissioning and operating procedures on water supply and sanitation networks, applying the corresponding protocols.

- LO7 Apply prevention and safety measures regarding the commissioning of water supply and sanitation networks, interpreting the safety plans of companies in the sector.

During the 2024/25 academic year, for the development of the module Assembly and commissioning of water networks, in order to facilitate the acquisition of the stipulated LOs, the use of direct instruction sessions was employed, which contribute to the scaffolding of basic concepts, that is the conceptual framework behind the required competences and guidelines for elementary procedures, also individual guided practice that allows students to have their first encounter with the use of instrumentation, equipment, tools, machines, and procedures allowing for the acquisitions of skills related to basic operations and, finally, collaborative group projects that include various complex tasks of a competence-based nature that allows for the integration of knowledge and skills to meet a target.

The teaching aids and resources associated with the intervention under the indicated methodological framework were:

- -

- Reading materials covering the technical and theoretical aspects, consisting of PDF documents that can be downloaded from the official Virtual Learning Environment for comprehensive reading, which, from an instructional approach, facilitate the learning of basic concepts and knowledge.

- -

- Handouts for the development of individual practical work and the use of the tools, equipment and materials available in the workshop, which facilitate the learning of procedures and the acquisition of basic skills.

- -

- Guides for the development of projects and use of the tools, equipment, and materials available in the workshop. These are projects with a PBL approach as they mobilise knowledge and skills, based on prior scaffolding, in a collaborative manner, reproducing small competency tasks that reproduce common activities of their future professional activity, but which, at the same time, allow for the acquisition of complex concepts based on knowledge of the basic aspects covered previously.

Throughout the progress of the educational intervention related to the module on assembly and maintenance of water networks, a variety of resources and methods of increasing complexity have been used to address the same LO. It would be worth asking, first, to what extent each of the different resources used in relation to a particular LO contributes to each student’s learning. Continuous assessment in VET with well-aligned assessment tools with learning activities that allow for the official assessment criteria to be checked, as required by the regional education administration [32], can provide us with a view in that direction from the teacher’s perspective. Continuous assessment is a process that involves evaluating not only the results but also the improvement achieved by the students through direct observation, and the evaluation of different products such as tests, project reports, or assembly of installations, while providing students with continuous feedback [33]. In addition, integrating the view of the student could lead us to rethink certain aspects of the educational intervention and planning.

The diversity and relativity of learning have been verified by a large number of studies; thus, there are people who organise their thoughts in a linear and sequential way, while others prefer a holistic approach. From a cognitive perspective, it has been shown that people think differently, as well as capture information, process it, store it, and retrieve it differently. The concept of learning styles would refer to the personal characteristics involved in the understanding and processing of information in teaching–learning processes. These individual characteristics include cognitive, affective, and physiological traits that influence how students learn more easily in each context, with the predominant style not being an immutable element over time for an individual.

Despite acknowledging that the concept of learning styles does not have a unanimous approach, together with a multiplicity of definitions and taxonomies from different perspectives, some authors consider this diversity in the way of learning as a way to improve learning through personal reflection and the differential peculiarities in the way of learning [34,35,36]. In the face of criticism and controversies about the concept of learning styles in what has come to be called “the myth of learning styles”, some authors indicate that, after an analysis of the literature, these works have important shortcomings that would nullify their conclusions: they do not differentiate the taxonomies despite having different approaches, some approaches to learning styles are certainly open to criticism but others are reasonable and well-founded; critiques are based exclusively on articles in English, ignoring the enormous and valuable production of knowledge in the area that exists in Portuguese and Spanish. The studies demonstrated that they practically only cite authors who reinforce their critical position, and finally, they point out that the criticism of learning styles lies in the fact that qualitative research methodologies are reviled by critical voices that only consider research valid from methodologies of the experimental sciences [37]. Contrary to that position, other authors question the validity of the theory of learning styles, which they consider leads to a waste of resources, a limitation of students’ potential, and the deviation from more effective pedagogical practices. As an alternative, learning theories and strategies, such as cognitive load theory, retrieval practice, spaced repetition, dual coding theory, metacognition, and collaborative learning, are presented. The theory of cognitive load suggests that our working memory has a limited capacity and that teaching methods should avoid overloading it. To optimise learning, educational materials and methods should be designed to minimise unnecessary cognitive load, allowing students to focus on essential information. In this sense, techniques such as the use of solved examples or the segmentation of information can reduce cognitive load and improve learning. Metacognition refers to the students’ ability to think about their own thinking and learning processes. Metacognitive techniques include planning, monitoring, and evaluating one’s own learning activities. Collaborative learning involves structured approaches for students to work together, which can improve understanding and critical thinking. Interaction and the exchange of ideas can enrich learning. Dual coding theory suggests that information is processed in different channels and that using them together can improve learning. Therefore, teachers must integrate visual elements with verbal explanations to facilitate a deeper understanding and better retention of information. This position is in favour of assessing students’ cognitive abilities and not learning styles [38].

As indicated above, there are different proposals for classifying learning styles from different perspectives. A proposal that contemplates learning styles from different perspectives proposes to distinguish between the following [39]:

- Active/reflective. Active students tend to retain and understand new information better when they do something active with it. They prefer to learn by rehearsing and working with others. Reflective people tend to retain and understand new information by thinking and reflecting on it; they prefer to learn by thinking and working alone.

- Sensory/intuitive. Sensory learners prefer hard facts and practical procedures, while intuitive learners are more comfortable with theories and abstractions.

- Visual/verbal. Visual learners learn best with pictures, diagrams, and graphs, while verbal learners prefer words, both in written and spoken form.

- Sequential/global. Sequential students understand the material in a linear and step-by-step way, while global students learn in large leaps, visualising the whole. They can solve complex problems quickly; however, they may have difficulty explaining how they did it.

When such learning styles are put together with the alternative learning theories and strategies, some links might arise, e.g., the dual coding theory deals with the visual/verbal style, or the theory of cognitive overload might deal with the sequential/global style.

In line with this, other authors offer a different insight into this issue through a systematic review in which they analyse the relationship between learning styles and cognitive processes from a neuropsychological educational perspective, concluding that active, reflective, visual, and auditory styles significantly impact working memory, planning, information encoding, and cognitive flexibility. Their conclusions emphasise that adapting pedagogical strategies to learning styles and promoting varied environments enhances cognitive functions and optimises meaningful learning [40].

We agree on this broader insight that acknowledges the existence of different learning styles in the classroom and tries to respond to the different styles from different approaches and strategies that better fit each style, incorporating cognitive aspects for this purpose.

One way or the other, as far as we are concerned, from a practitioner point of view, it seems clear that not all students learn at the same pace and with the same resources. Hence, it would be worth asking: What perception do students have of the learning they have acquired? Which method and material did they find most effective for acquiring new knowledge and skills? To what extent, in the students’ perception, have the different resources and materials contributed to the acquisition of learning? Is the perception of the usefulness of the different resources used for learning homogeneous among students? Should more effort and time be focused on some materials and others discarded?

In order to define the scope of the investigation, we set out to explore the perceived usefulness of the teaching resources used to address learning outcomes LO1 and LO3, described in Table 1, as set out in the official curriculum, through general perceptions and reflection on two tasks highly representative of future professional activities: the installation of a connection to a drinking water supply network and the installation of a hydraulic pump.

Table 1.

Learning outcomes and assessment criteria related to the study.

The teaching resources and materials consistent with different didactic methods used to address the LOs described in Table 1 were:

- Reading material in relation to the assembly of water networks:

- Stages in supply and sanitation networks

- Components and accessories for the installation of networks

- Organisation and planning of the assembly in networks

- Graphical representation of hydraulic systems

- Equipment, tools, and techniques for network assembly

- Pumps and pumping stations

- Installation project guides

- A.

- Guides for the development of individual assemblies

- Use of basic assembly tools and Personal Protection Equipment

- Inventory of accessories and equipment involved in assemblies

- Types of pipes: cutting techniques

- Mechanical joints

- Flanged joints

- Glued joints

- Threaded joint

- Electrofusion joint

- B.

- Guides for collaborative projects integrating competency tasks:

- Collaborative project 1: Installation of a domestic drinking water connection

- Collaborative project 2: Installation of a lift pump

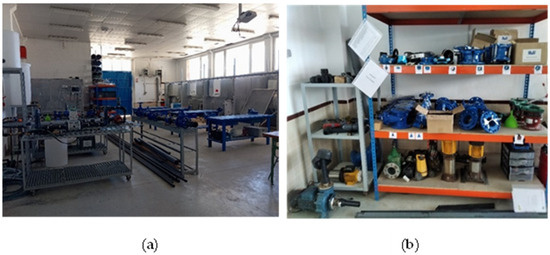

- Workshop on installing systems using all types of tools, components (valves, metres, pumps, etc.), and accessories (flanges, joints, fittings, etc.) for individual assembly, involving different basic work procedures, and the manufacture of a product (individual practical work). An overview of the workshop and some of the equipment and accessories can be seen in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows examples of this type of task.

Figure 1. (a) General view of the water network assembly workshop, where basic individual assembly tasks are carried out individually by students. (b) View of some of the resources available to carry out assembly techniques and projects.

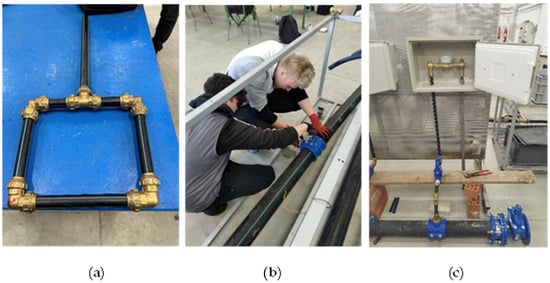

Figure 1. (a) General view of the water network assembly workshop, where basic individual assembly tasks are carried out individually by students. (b) View of some of the resources available to carry out assembly techniques and projects. Figure 2. Basic individual assemblies: (a) mechanical connection of brass fittings to polyethylene (PE) pipe, (b) assembly of cast fittings on pipe, (c) assembly of a connection in the workshop.

Figure 2. Basic individual assemblies: (a) mechanical connection of brass fittings to polyethylene (PE) pipe, (b) assembly of cast fittings on pipe, (c) assembly of a connection in the workshop. - Workshop for assembling installations with all types of tools, components (valves, metres, pumps, etc.), and accessories (flanges, joints, fittings, etc.) for the development of complex installations, including water networks, which require coordination and teamwork to complete (collaborative projects). Figure 3 shows the work area for the development of collaborative projects inspired by real jobs, while Figure 4 shows students working on this type of project.

Figure 3. (a,b) Images of real assembly work ongoing in the streets; (c) outdoor workshop for the development of network assembly projects.

Figure 3. (a,b) Images of real assembly work ongoing in the streets; (c) outdoor workshop for the development of network assembly projects. Figure 4. Different images of students performing tasks related to the assembly of drinking water connections and the assembly of a pump in collaborative projects in the outdoor workshop.

Figure 4. Different images of students performing tasks related to the assembly of drinking water connections and the assembly of a pump in collaborative projects in the outdoor workshop.

2.3. Data Collection

The data collection tools used were a survey technique involving a structured interview and an anonymous opinion questionnaire to gather the opinions of the students on the issue raised. No personal data was registered. Interviews were not recorded, and only codified written notes were collected to avoid the identification of participants from the registers. The eight students in the group completed both the survey and the interview.

The survey was conducted at the end of April 2025, once all the students in the group had been assessed and graded prior to the company training phase, which five of the eight members of the group would be eligible to attend, so that it was clear that the survey was being conducted for the purpose of improving the educational practices developed and that it would in no way influence the grades obtained. Individual interviews were conducted in the classroom or workshop throughout May, after the tests and assignments had been completed during the regular term. Some of the students had already started their work experience, so we took advantage of their visits to the centre to carry out the interviews. Others were attending the centre for extra classes to catch up on a module, so we used some spare time to interview them.

The grades obtained by the students in relation to LO1 and LO3, having used the methods and materials previously described, are presented in Table 2. Grades are expressed in percentages; the minimum percentage to be considered a pass is 50% in both aspects considered: skills and concepts. Practice U1-5 relates to different individual assembling techniques previously described. The acquisition of concepts was assessed through tests and questionnaires, and the skills were assessed through direct observation, considering the criteria described in Table 1. The grades had been given before both the survey, and the interviews were carried out. It is of interest to analyse if there is a correspondence between their preferences and the marks obtained.

Table 2.

Marks obtained related to LO1 and LO3 (% achieved).

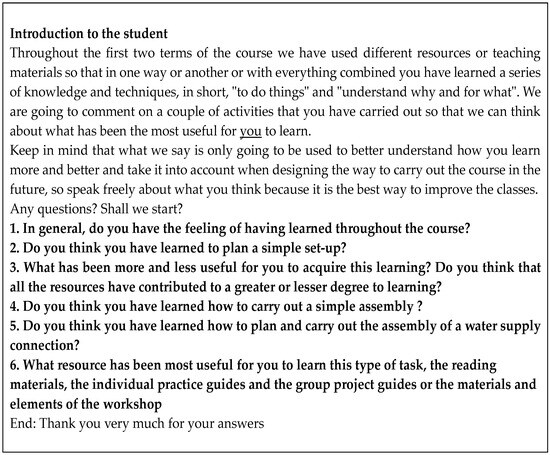

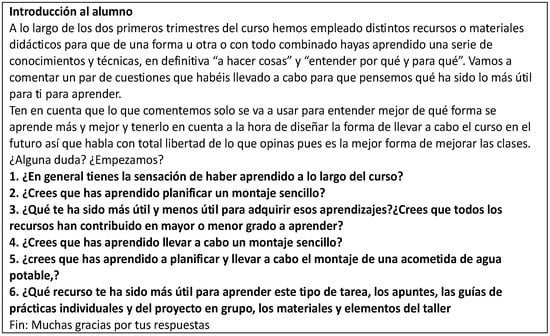

The aim of the interview was to gain a more detailed insight into the students’ perceptions and to see whether what they had previously indicated in the survey was reinforced in a relaxed atmosphere without the presence of other classmates or whether, on the contrary, they expressed views that contradicted what they had initially indicated. The script of the interview can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Interview script (original version in Spanish in Appendix A).

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

The results obtained in the survey conducted on the degree of usefulness the students attribute to the different teaching resources used in the course are shown in Table 3, using a Likert scale (1—Not useful, 2—Not very useful, 3—Somewhat useful, 4—Quite useful, 5—Very useful).

Table 3.

Results of the survey on the usefulness of the resources and materials used in teaching and learning situations related to the acquisition of LO1 and LO3 (1—Not useful, 2—Not very useful, 3—Somewhat useful, 4—Quite useful, 5—Very useful).

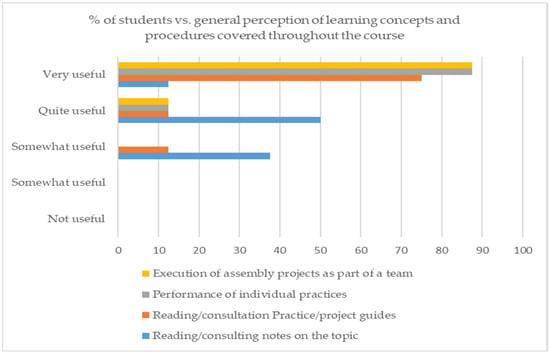

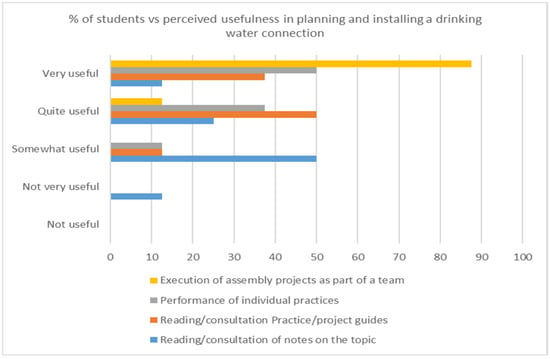

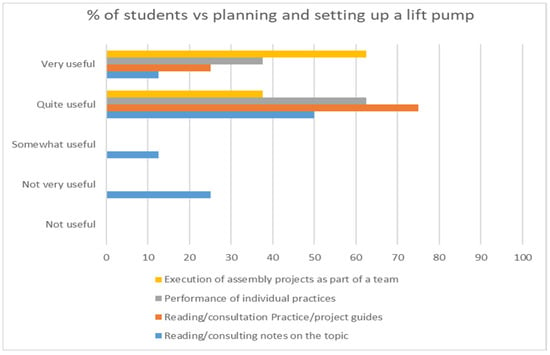

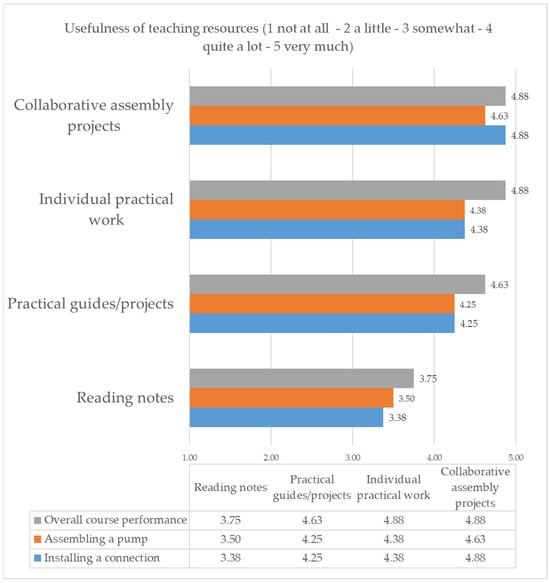

Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the data in Table 3 in graphs, so that the difference in students’ perception of the usefulness of the different teaching materials used in relation to the LOs under consideration is better identified.

Figure 6.

Percentage of students according to the usefulness perception of students in general in learning the different concepts and procedures covered during the course, related to the acquisition of LO1 and LO3.

Figure 7.

Percentage of students according to their perception of the usefulness of the methods and resources used throughout the course to acquire the knowledge and techniques required for planning and installing a drinking water connection, related to the acquisition of LO1 and LO3.

Figure 8.

Percentage of students according to their perception of the usefulness of the methods and resources used throughout the course to acquire the knowledge and techniques involved in planning and assembling a pump to drive water from one tank to another higher tank, related to the acquisition of LO1 and LO3.

Table 4 shows the average usefulness rating attributed to each teaching resource and the distribution of the ratings.

Table 4.

Statistics from the survey on the usefulness of the resources.

Figure 9 shows more clearly the difference in usefulness perceived by students in terms of the average of the different teaching resources used for learning related to the LOs under consideration.

Figure 9.

Average rating of the usefulness of the different media used.

3.2. Qualitative Results

The interview began by reflecting on the usefulness of the resources from a general perspective, trying to identify the overall impression that the students had of their learning. It then moves on to more specific aspects that allow them to recall experiences, images, and memories of what they have done and what they have retained from a competence-based perspective, before moving on to a reflection on a specific project, which involved mobilising these competences in practice. Regarding this last point, initially, the interview was intended to reflect on the projects regarding the installation of the water supply connection and the installation of a pump, in line with the survey, but it was decided that the interview would not delve deeper into the installation of the pump after the first interview, as it was taking too long and was proving tedious and repetitive with regard to the connection, albeit with a slightly higher degree of complexity.

3.2.1. General Perception of Learning

When asked: “In general, do you feel that you have learned a lot during the course?”, their opinions indicated a general perception of having acquired new knowledge about aspects that were completely new to them and provided some interesting insights, as can be seen in the following quotes:

Student 1: “A lot, more than enough for the world, they don’t have these studies there, which is what’s needed, except for FOL (refers to Training and Career Guidance) and English… Everything is needed, ten out of ten… really. The operators there don’t know anything, and we are technicians”.

Student 2: “Yes, positive, very satisfied, I didn’t think I would like it so much”.

Student 3: “Yes, when I go around (referring to the street) and see construction sites, I now know what materials they are using and what they are doing. I liked the course. It was my second choice, and I enjoyed it”.

Student 6: “Yes. Lots of things, especially in theory, although I didn’t put as much effort into it as I should have”.

Both Student 1 and Student 3 introduced external references to reinforce/confirm that they have acquired new learning. Student 1 had already started the in-company training when the interview was conducted, and his perception reinforced and confirmed this when he compared himself to operators who lacked training. Student 3 was waiting to start his work placement, and the interview reinforced his opinion with regard to the construction work he sees on the street. Both Student 3 and Student 2 added an interesting nuance when they expressed their satisfaction with the fact that they “liked” the course more than they initially expected. Student 6 also introduced an interesting nuance by acknowledging that they had not put in the effort that was really necessary. When asked this first question, some students already expressed their strong preference for more practical learning.

3.2.2. Perception of Learning Skills: Planning a Simple Assembly

When asked the second question, which focuses on skills: Do you think you have learned how to plan a simple assembly? Half of the students hesitated, showing a lack of confidence in their actual learning, and the rest said yes, and gave examples related to planning:

Student 2: “Yes, more or less… to repair leaks, change pipes…”

Student 3: “Plan it? Yes… present it… the measurements… decide on the tools, etc.”

Student 5: “I’m not sure, it would be difficult at first, but I think so”

Student 7: “I would know how to plan it, first make a diagram, then make a list of materials, the price…”

3.2.3. Perception of the Most Useful Resources for Planning

The third question prompted an initial reflection on which resource they found most useful for learning how to plan: What has been most useful and least useful for acquiring these skills? Although more practical approaches were generally preferred, there was some disparity in the perception of the degree of usefulness, which was in line with the presence of different learning styles. An interesting nuance was added with regard to activities with an individual or group practical approach. For different reasons, the students considered individual activities to be more useful for learning technical issues than those carried out in teams:

Student 1: “The notes are very important, they contain everything and are very useful for later reference, just like the plant manager’s notes. But the material is also important because we have assembled and disassembled things.” (Student 1) When asked if individual practical work or group projects are useful, he adds, “I’m older than the others and there’s a lot of messing around, and if the teacher isn’t there, we don’t get anywhere.”

Student 2: “Everything, yes. There are things in the notes that I didn’t know, for example, about water hammer. I didn’t know the symbols, and I learned them with the theory”. When asked about the order of usefulness, Student 2 added: “Individual practical work first and then group assembly because some people don’t help. The notes and guides are helpful, but less so”.

Student 3: “The most useful thing is to see it in a script where everything is explained so you can do it and ask yourself questions… I think everything has been useful, but the notes less so because everything is in the guides and there’s a lot in the notes and I see it all as important”.

Student 5: “It’s most useful when you do it on your own because you think about it more”.

Student 6: “Above all, the workshop on my own because I understand what I’ve seen in class. On your own it’s more boring but you concentrate more; in a group you get distracted”.

Student 7: “Firstly, the practical work I’ve done”.

Student 4: “Yes, all of them. First, the group projects; second, the notes; third, the guides; and last, the individual practical work”.

3.2.4. Perception of Learning Skills: Carrying out a Simple Assembly

The fourth question invited reflection on more practical learning, asking: Do you think you have learned how to carry out a simple assembly? The answers were more decisive, with all students answering yes without hesitation, showing higher confidence in practical execution than in previous planning. Some responses included the following:

Student 1: “Yes, no problem”.

Student 4: “Yes”.

Student 7: “It would be more difficult to do at work than in the workshop, but I would give it a go”

Student 8: “Yes, I’m sure”.

3.2.5. Perception of Learning: Planning and Assembly

The fifth question led to reflection on the planning and assembly of a specific installation typical of the professional development of graduates: Do you think you have learned how to plan and carry out the assembly of a drinking water connection? Again, some hesitation appeared when dealing with planning:

Student 1: “It would be difficult at first, but I think I could do it”.

Student 2: “Yes, I think I can do it. The position of the parts…”.

Student 3: “Yes, although we are used to asking you, but yes, on my own I think I could. As we have done it inside and outside”.

3.2.6. Perception of the Most Useful Resources for Learning

The last question invites reflection on what type of resources have been most useful for learning in general, without considering any particular activity or objective. When asked: What resource has been most useful for you in learning this type of task, notes, individual practice guides and group project guides, workshop materials and elements? All students pointed to practical activities as the most useful for learning and remembering what they had learned. However, they indicated that all the resources used had been useful for learning. Some quotes along these lines as expressed by the students:

Student 1: “Outdoor work (referring to the outdoor workshop) is what sticks best and is most similar to real life”.

Student 5: “Assembly in the trench is the most comprehensive (referring to the outdoor workshop). Perhaps not so many steps are necessary (referring to addressing the same learning outcome through a progressive sequence of different means)”.

“Individual work and work in the trench… but all useful”.

The units of analysis used were the respective answers from the students to each of the questions posed. The responses were classified in tables, allowing for a comparative analysis of the respective answers for each of the questions to be carried out. The coding scheme followed a nomenclature, as follows: Student: S1 to S8, Question: Q1 to Q6, Responses: R1 to R6. Thus, S8Q1R1 would indicate the response of Student 8 to Question 1.

The themes considered in the first approach were the overall perception of student learning, perception of the acquisition of specific competences, and eclecticism in the attribution of utility of resources/methods and resource/method with greater attribution of utility. The categories were mainly developed deductively, considering the questions derived from the main objective of the study:

What perception do students have of the learning they have acquired? Which method and material did they find most effective for acquiring new knowledge and skills? To what extent, in the students’ perception, did the different resources and materials contribute to the acquisition of learning? Is the perception of the usefulness of the different resources used for learning homogeneous among students? A final theme originated from the data collected in the study: characteristics of usefulness.

The qualitative data analysis procedure began with the organisation of the data obtained in the form of tables using Microsoft Excel®. After this, the correspondence and relevance of the answers in relation to the proposed themes related to the questions posed were identified, as well as the identification of new categories induced from the data. Finally, the interpretation was performed, and conclusions were drawn.

Subsequently, a fifth theme emerged from the students’ responses: characteristics of the usefulness of the resources. The categories identified are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Themes induced from the data collected.

Saturation in qualitative research denotes the stage at which the data collection and analysis have been exhaustively examined and comprehended, and no additional themes have emerged. Saturation, under the framework of thematic analysis, represents the point at which no further themes are identified from the analysed material, and the data gathered have been fully utilised to generate innovative insights [42,43]. The data collected and analysed could comprehensively answer research questions, and the themes identified were sufficiently exemplified, indicating the termination of data analysis.

4. Discussion

The survey results show that most students (87.5%) attribute greater usefulness for the learning they have acquired to practical activities, often referred to as “learning by doing”, both through individual activities, with an average rating of over 4, and in groups, with an average rating of close to 5, either from a general perspective of the module program (Question 1 of the survey) or in relation to the learning outcomes required considered in the study (Questions 2 and 3 of the survey). Although none of the written media used (notes and guides) are completely ruled out, they receive a low rating in terms of usefulness for learning. Thus, in grouping Rating 2 (not very useful) and Rating 3 (somewhat useful) as a negative rating of written media, it would be considered that around half of the students do not perceive this type of resource as useful, with an average rating of 3.75 for notes from an overall perspective, and 3.38 and 3.50 in relation to the specific situation under consideration. This circumstance is consistent with the eminently practical nature of vocational training and the type of students who mainly enrol in this type of training, especially at the intermediate level. However, the interviews conducted allow for a more in-depth analysis of the students’ perception of the relative usefulness of the resources used, introducing nuances and very interesting elements to this initial reading of the survey. The interviews revealed other issues from the students’ perspective, providing information on their reasons for attributing greater or lesser usefulness to the teaching resources, an aspect that cannot be observed in detail from the survey.

Thus, based on the comments obtained, most of the students do recognise a certain degree of usefulness for learning through written media, introducing nuances of value for this medium, such as its asynchronous nature, i.e., they are useful for consultation at any time and are a reference for future consultation, hence the reusability of a resource would emerge as a feature useful for learning. It is also noted that the usefulness of writing materials depends on the amount of time spent on them, with some students acknowledging that they “do not find it useful” but “have not spent time on it”. In this sense, time-/effort-demanding resources would be regarded as less useful than other ones related to the same learning outcomes involving hands-on learning.

Based on the information obtained through the surveys and interviews, we can observe that, despite being a small group, there were different preferences and perceptions of the contribution of the resources used for learning, a fact that could be linked to the existence of different learning styles among the students or, from a broader approach, to different cognitive abilities. This circumstance would justify the need to diversify teaching methods and resources to facilitate learning for each student, in line with the findings of various authors [17,44]. Similarly, an investigation carried out with the purpose of determining the relationship between the teaching materials used and the academic performance of primary students in various public schools concluded that the majority of students consider manipulative materials effective for understanding complex concepts, and that a variety of teaching materials can improve academic performance [45]. A recent study analysing the influence of different didactic materials on writing skills in high school students observed that, though active materials were considered as more useful by students, none of the didactic materials was seen as useless, ranging from traditional textbooks to online platforms and specialised software [46]; a study carried out with students of the University of Oviedo showed a clear preference of students of using active methods and materials [47].

Therefore, an educational intervention should be planned from the beginning of the course, using diverse and complementary methods and means, emphasising those that best suit the preferences of the group and favour learning and the acquisition of the desired skills, as suggested by other authors teachers should consider learning styles as a key element in the design and definition of teaching-learning strategies, in order to maximise students’ cognitive resources in each of the learning activities [48] (p. 99) by linking learning styles and active methodologies, and proposing different and diverse ways of learning to students to facilitate the acquisition of the required competencies [49].

In any case, practical activities that simulate professional tasks are preferred by the group, as they were seen as most useful; in terms of usefulness, this sentiment was in line with the conclusions of other researchers on the usefulness attributed by university students to virtual company simulators in their training under a PBL approach [50]. Thus, the transferability to real scenarios would be one of the most valued dimensions of the usefulness of the didactic resources used in the course.

A certain discrepancy emerged with respect to the survey, since although individual and group activities were valued almost equally, there was a certain preference for individual activities in terms of their usefulness for learning, as they facilitated concentration on the task, and because group tasks presented a certain conflict with regard to the contribution of the different members of a work team to the task. Thus, resources that kept the student focused on the ongoing task were seen as more useful by some students.

Through the diversity of media and resources, the aim is to achieve a reasonable fit between teaching styles and learning styles. In between these two extremes, we would place teaching strategies and methods, teaching resources and media, and teacher action and student action, assuming that “the optimal situation for learning is one in which diverse strategies, resources and opportunities can be mobilised, combined and utilised” [51] (p. 57). However, in the adjustment of teaching styles and learning styles present in a group, although it is advisable to emphasise the style preferred by the majority of students, in our case the most practical means, the use of other means and methods should not be omitted in order to “avoid a single teaching style framework that generates restrictive habits in students, impoverishing their range of styles to use”. From this perspective, offering learning situations mediated by resources that would not be preferred by the students would contribute to their development of greater competence in ‘learning to learn’. It should not be forgotten that this adjustment between teaching and learning styles does not guarantee the successful acquisition of competences by students, although it is a factor that plays a significant role in their achievement [51]. It should be noted that of the eight students in the study group, seven passed the module with grades between 80% and 50% and were promoted to the second year, while only one student obtained a failing grade and was not promoted to the second year.

In order to relate the results obtained by the students to the attribution of usefulness for learning of the different means used, it must be considered that these are obtained in a progressive process that begins with simpler tasks and content, but completely new for the students, which are the basis for the approaches to later, more complex and integrative tasks and content.

Thus, we can see that the initial individual practical tasks were the ones with the lowest number of failures (two out of eight), although in general, the grades were not high (between 49% and 66% of achievement). These basic tasks allowed for progress later on and constituted new, simple but unknown activities for the students, a fact that would justify their perception of greater relative usefulness. The grades obtained in relation to the conceptual part linked to these practical tasks, which required the use of written materials and their comprehensive reading, spanned a range of similar amplitude; however, they were somewhat lower (between 33% and 59% of achievement) and with a greater number of failures (four out of eight). This circumstance parallels the attribution of less usefulness to this type of material, pointing out the need to address it during the course of practical activities, such as in project-based learning.

Both the conceptual and procedural parts linked to the field of pumps were more complex and required the prior acquisition of the knowledge and skills seen previously. In the conceptual tests in this area, which were the most complex, a high percentage of failures (four out of eight) was observed, delving into the need to rethink the way of approaching the theoretical and conceptual aspects that are part of the competencies required.

Despite all this, the performance observed in the development of collaborative projects was, in the end, much better than would be expected considering the previous results, with the number of students who did not exceed expectations falling to only two out of eight in each of the projects. The development of projects required an integrated mobilisation of previously seen knowledge and skills, giving them a greater meaning with the construction of a product with a function and a form equating to real professional development, such as being able to observe similar constructions in the street outside the educational centre, an aspect for which they attribute to the projects a high utility.

Given the integrative nature of skills and knowledge of the projects and in view of the good results observed, the real acquisition of learning was greater than the perception that the students themselves had of what they learned, which can be attributed to metacognitive awareness. Metacognitive awareness enables enabled students to understand and monitor their own thinking processes, which is essential for effective self-regulated learning strategies, such as goal setting, planning, and self-assessment. Metacognitive awareness, self-regulated learning, and academic results are closely interconnected. When learners actively regulate their learning through these strategies, they become more adaptive and efficient in managing challenges, leading to improved academic performance [52,53,54]. Therefore, it would be interesting to explore how the use of different didactic methods and resources impacts metacognitive awareness in VET students in future research.

Despite the fact that these studies were mostly carried out by examining male students, there is a small but growing proportion of female students. Female and male students often exhibit distinct preferences in learning methods. Female students tend to favour collaborative and interactive approaches. They are also more likely to employ metacognitive strategies to regulate their learning. In contrast, male students often prefer independent and task-oriented methods, such as problem-solving and hands-on activities, reflecting a tendency toward autonomy and practical application in line with the results of the study [55].

These differences highlight the importance of adopting flexible instructional strategies that accommodate diverse learning preferences to optimise academic outcomes for all students; therefore, there could be a need for planning a different balance of methods and resources, whether dealing with an all-male group or a gender mixed group.

In short, although without abandoning the use of written support materials around the more conceptual aspects, shifting their approach to include the development of practical activities can be a way to improve the acquisition of the competences required to graduate.

5. Limitations of the Study

It bears noting that the present case study has been carried out on a population with a very small number of components, which imposes limitations when drawing conclusions about possible generalisations. However, this was not the objective of the study; rather, it was to explore possible trends in the perception of the relative usefulness of different teaching resources for learning among VET students and to identify possible factors that could affect this attribution, considering the lack of research on this particular field. The characteristics of the participating group did not allow us to observe whether there were significant differences in the identified preferences depending on gender or even to identify additional elements that could emerge from this perspective, an issue that is worth considering in future studies.

The group, although few in number, comprise the entire group of students studying the module and was representative, in number and predominant gender, of the type of groups of students who study this particular vocational training degree in Spain, according to the statistical data on enrolment and completion of vocational training studies from the Ministry of Education. On the other hand, the reference learning outcomes are mandatory for obtaining the degree considered. With this, it can be considered that the study is transferable to other groups that study this degree in the future and in other regions of Spain. Thus, the study may be expanded to additional cohorts in the same educational centre and to additional groups in other centres to obtain a greater number of data that corroborate or reorient the initial conclusions obtained from the initial, exploratory scope. Therefore, the conclusions derived from this study are useful to better shape and focus the continuation of the research.

6. Conclusions

In response to the initial question that gave rise to this exploratory study, according to the data obtained and among the group of participating students, there was a perception of greater usefulness for learning from the means and methods of a practical nature. Although practical resources are preferred and perceived as most useful, written materials were not rejected outright and were perceived to varying degrees as contributing to learning. This circumstance could be linked to the existence of different learning styles. Thus, the presence of different learning styles would lead to differences in the students’ attribution of usefulness to the teaching resources used during the course.

Based on the results obtained, the degree of acquisition of skills and knowledge assessed through the different assessment instruments with the established criteria was, in fact, greater than the perception that students had of the learning they achieved through the different means and methods. Students reported strong practical confidence, moderate variability in planning confidence, and a clear preference for hands-on, individual practice—supplemented by guides and notes. Students felt capable of planning and executing a drinking water connection, with initial difficulty expected and some reliance on instructor guidance. Outdoor/trench work was perceived as the most authentic preparation for professional tasks.

On the one hand, a motivating effect was observed in the initial practical tasks to which they attributed a very high usefulness for learning, and on the other hand, an effect of consolidation and integration of the projects was also observed with a high attribution of usefulness. Written materials and theoretical study play a supporting role in a progressive process whose concepts should be addressed to a greater extent in the practical activities themselves.

Different dimensions that contribute to the perception of usefulness have been identified, such as effort/time, focus, transferability, and reusability. These aspects are not present simultaneously in all teaching media used, but they allow for all of them to be perceived as useful to a greater or lesser extent.

Based on the observations made by the students in the interviews, at least four dimensions emerge that influence the perception of the usefulness of a teaching resource or medium:

- EFFORT: perceived as the medium’s ability to facilitate learning with less time or effort on the part of the student.

- FOCUS: perceived as the ability of the resource to facilitate the student’s concentration on the issue at hand.

- TRANSFERABILITY: perceived as the ability of the resource to facilitate the transfer of learning to real work contexts.

- REUSABILITY: perceived as the ability of the medium to facilitate future review of concepts or procedures associated with learning over time.

7. Further Work

Considering the limitations of the study—given that in each year’s group the characteristics of students on the intermediate vocational training course in water treatment networks and treatment plants are very diverse in terms of age, prior knowledge, educational background, and personal circumstances—no generalisations are intended to be made based on this case. However, the present study sets a starting point for identifying trends in the perception of usefulness of different didactic means among students as a factor to consider in the planning of the course. Hence, this study will be continued in subsequent years with successive cohorts of students and will consider additional groups from other educational centres. In doing so, the knowledge derived from this present study and subsequent studies may be relevant for the redesign of the intervention associated with the network assembly and commissioning module and facilitate learning across different student profiles.

The continuation of the work from this exploratory study would include the following lines of work:

1. Repeat the study at the same school with a new class of students, and invite an additional school located in the same region and two more schools located in other regions of Spain to participate in the study through a survey of students taking the same module that would allow for around 50 participants and random interviews with a percentage of students from these schools;

2. Sharing methods and means with the teachers at the participating schools and collecting their perceptions;

3. Analyse whether different preferences are observed between female and male students;

4. Delve into the characterisation of the usefulness of a medium/resource (dimensions of utility);

5. Investigate the possible relationship between the attribution of usefulness and academic results.

This study will continue in the course year 2025-2026 with a new group of first-year students to allow for a greater understanding of the perception of VET students of the relative usefulness of the didactic materials and methods in their learning. Other educational centres will be invited to participate in the study to expand the population participating in the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.-M. and C.R.-M.; methodology, A.C.-M. and C.R.-M.; validation, C.R.-M.; formal analysis, A.C.-M.; investigation, A.C.-M.; resources, A.C.-M. and C.R.-M.; data curation, A.C.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.C.-M. and C.R.-M.; visualisation, C.R.-M. and I.N.-S.; supervision, C.R.-M. and I.N.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the University of Alicante through the project “Advances in the modelling and characterization of sustainability in architecture with AI”, grant number GRE2022, University of Alicante, 2024/00083, and the APC was funded by the University of Alicante.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Regulations of the Ethics Committee of the University of Alicante states that ethical approval is required only for research projects that involve biomedical procedures, personal data, psychological or health-related information, biological samples, or any type of experimentation on humans or animals (Article 3.1 of the Regulations of the Ethics Committee of the Research of the University of Alicante). The present study comprised research within the social sciences in which methodologies exclusive to the biomedical sciences are not used. Anonymous opinion surveys used in this study did not include psychological or health information, and no personal data or recordings of the interviews were collected. Hence, opinion polls, on a topic or issue, professional situation, satisfaction with certain issues, etc., as long as psychological or health information was not included, did not require authorisation from the Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IES | Instituto de enseñanza secundaria [Secondary School] |

| FOL | Formación y orientación laboral [Training and Career Guidance] |

| LO | Learning outcome |

| RD | Royal decree |

| VET | Vocational education and training |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Interview script (original version in Spanish).

References

- España. Ley Orgánica 3/2022, de 31 de Marzo, de Ordenación e Integración de la Formación Profesional. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2022/03/31/3/con (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Rajadell Puiggròs, N. Formative processes in the classroom: Teaching-learning strategies. In Didáctica General Para Psicopedagogos; Sepulveda, F., Rajadell, N., Eds.; Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: Madrid, Spain, 2001; pp. 465–528. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández March, A. Active methodologies for skills training. Educ. Siglo XXI 2006, 24, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Montanero-Fernández, M. Emerging pedagogical methods for a new century: What is really innovative. Teoría Educ. Rev. Interuniv. 2019, 31, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, M. Does student learning improve through project work? In What Works in Education? Evidence for Educational Improvement; Fundació Bofill: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://ivalua.cat/sites/default/files/2020-05/Que_funciona_16_Castella.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Zhang, L.; Ma, Y. A study of the impact. of project-based learning on student learning effects: A meta-analysis study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1202728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, D.; Ortega-Sánchez, D. Project-Based Learning: A Systematic Review of the Literature (2015–2022). Human Rev. Int. Humanit. Rev./Rev. Int. Humanidades 2022, 11, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, L.G.; Santiago, A.W. Considerations on technology and its teaching. Tecné Epistem. Didaxis TED 2013, 33, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condliffe, B. Project-Based Learning: A Literature Review; Working Paper; Building Knowledge to Improve Social Policy; MDRC: Gurugram, India, 2017. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578933.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Villagrá, C.J.; Molina, R.; Llorens, F.; Gallego, F.J. Project-Based Learning: Experience and Lessons Learned; Octaedro Editorial; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; p. 41. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/108419 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Feeney, S.; Machicado, G.; Larrosa, L. Project-Based Learning as a Teaching Policy: Some Questions. Prax. Educ. 2022, 26, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canut, A. Plan for the Transition from a Module-Based Teaching-Learning Model to a Comprehensive Project-Based Learning (PBL) Model in a VET Course in the Professional Field of “Energy and Water”. Master’s Thesis, Cardenal Herrera University, Valencia, Spain, 2024. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10637/18392 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Ayala López, M.A. Technical and Pedagogical Considerations for Developing and Evaluating Teaching Materials. Rev. Atlante Cuad. Educ. Desarro. 2014. Available online: https://www.eumed.net/rev/atlante/2014/02/materiales-didacticos.html (accessed on 10 March 2025).