Abstract

Criminal laws and their deserts-based punishments, particularly in Anglo-American systems, remain grounded in folk psychology assumptions about free will, willpower, and agency. Yet advances in neuropsychiatry, neuromicrobiology, behavioral genetics, multi-omics, and exposome sciences, are revealing how here-and-now decisions are profoundly shaped by antecedent factors. This transdisciplinary evidence increasingly undermines the folk psychology model: some argue it leaves “not a single crack of daylight to shoehorn in free will”, while others suggest the evidence at least reveals far greater constraints on agency than currently acknowledged. Historically, courts and corrections have marginalized brain and behavior sciences, often invoking prescientific notions of monsters and wickedness to explain harmful behavior—encouraging anti-science sentiment and protecting normative assumptions. Earlier disciplinary silos, such as isolated neuroscience or single-gene claims, did little to challenge the system. But today’s integrated sciences—from microbiology and toxicology to nutrition and traumatology, powered by omics and machine learning—pose a threat to the folk psychology fulcrum. Resistance to change is well known in criminal justice, but the accelerating pace of biopsychosocial science makes it unlikely that traditional assumptions will endure. In response to modern science, emergent concepts of reform have been presented. Here, we review the public health quarantine model, an emergent concept that aligns criminal justice with public health principles. The model recognizes human behavior as emergent from complex biological, social, and environmental determinants. It turns away from retribution, while seeking accountability in a way that supports healing and prevention.

1. Introduction

Among social institutions in the Global North, especially those following Anglo-American criminal law and its associated ‘deserts-based’ punishment, courts and correctional institutions are notoriously resistant to change [1]. While much has been written on the far-reaching public health consequences of mass incarceration and strict crime control policies [2,3], the upstream drivers of such practices—the prescientific folk psychology beliefs underpinning the status quo—have largely escaped scrutiny [4]. In a world increasingly demanding science and evidence-based policies and practices, desert-based systems of punishment have largely remained adjacent to those demands.

Over the past 25 years, our understanding of human thought, behavior, and their complex biopsychosocial roots has grown substantially [5,6]. Among the most influential developments is the body of work known as the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD), which shows that factors from early life—including those occurring pre-conception—play a significant role in determining health outcomes later in life [7,8]. DOHaD findings are bolstered by the expanding fields of exposomics and the availability of multi-omics technologies. The exposome examines accumulated environmental exposures (both adverse and beneficial) that help predict the biological responses of the “total organism to the total environment” over time [9]. Omics technologies produce objective markers from genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics, and allow for pairing with aspects of cognition and behavior [10,11]. These advances are illuminating pathways between environmental exposures, genetic susceptibility, and lived experiences—promoting an understanding of how these factors interact to shape lifelong trajectories of health and disease, including those related to mental health and behavior.

Taken as a whole, this growing body of scientific knowledge is challenging long-standing cultural narratives—particularly those rooted in folk psychology—that rely on simplistic notions of individual choice, moral blameworthiness, and personal responsibility [12,13]. Indeed, some argue that the progression of biopsychosocial scientific evidence is placing the courts and corrections in a position in which they appear anti-science; it is argued that the emergent science is undermining the legitimacy of punishment and retributive systems [14]. While there have been demands for total abandonment of prisons—the so-called prison abolition movement—plans for suitable alternatives to current systems remain sparse [15].

One emergent concept receiving increased academic attention is Gregg D. Caruso’s public health quarantine model [16,17,18]. Here, we discuss the particulars of this emergent non-retributive concept of criminal justice. While the concept has been explored in detail within the frameworks of legal philosophy, it has not yet received attention in transdisciplinary channels that are otherwise well positioned to consider its implementation. Since justice is the first word mentioned in Societies scope, readers are well positioned to appraise how the concept might be readied for real-world scientific evaluation and cautious merger onto the road of policy translation. Like many academic models addressing complex social questions, the contemporary public health quarantine model is built upon historical frameworks and ideas. We consider this history to be important, and include discussion of early developments of the concept. Since the model abandons the current fulcrum of Anglo-American retributive punishment—worldviews rooted in folk psychology—we begin with a brief discussion of the subject.

2. Folk Psychology: A Primer

Folk psychology beliefs are “commonsense” or “everyday” ideas that guide expectations concerning the behavior of others [19]. As such, they often foster stereotypes, trait attributions, and assumptions. One of the more common folk psychology beliefs is that people can, and should, exert full control over their decisions through agency and willpower. This belief underpins widespread moral judgments about complex conditions like obesity, despite robust scientific evidence showing that willpower plays a negligible role compared to broader structural, environmental, and biological influences [20,21]. Yet such outdated assumptions about ‘free will’ and obesity persist, even among health professionals [22].

Folk psychology beliefs overlap with mythology and parapsychology, allowing room for the existence of “demons,” “monsters” and “beasts” in society, morally blameworthy creatures that are not like the rest of us [23]. It is not uncommon for judges to make moral judgment statements at sentencing such as “there is a special place in hell for you,” and engage in dehumanization through descriptives such as “monster,” “beast,” “demonic,” and related terms [24,25,26,27]. These types of claims, also made regularly by prosecutors, reinforce folk parapsychology ideas, which is to say, anti-science ideas, on the existence of monsters and beasts. For example, at the trial of Manson followers Leslie Van Houton and Patricia Krenwinkel (the former recently granted, the latter recently recommended for, parole [28]), the prosecutor called for the death penalty in this way: “These defendants are not human beings, ladies and gentlemen, they are not human beings. These defendants are human monsters, human mutations” [29].

Critical to our discussions below, folk psychology beliefs related to free will and morality underpin modern criminal justice systems. That is, across the globe, legal systems continue to operate as bulwarks for prescientific notions such as moral fiber. While the courts allow for rare exceptions to the assumption of inner reasoning power—such as very young children or individuals with significant intellectual disability—most people who come into contact with the justice system are assumed to be fully autonomous agents. The enormous variability in human development, shaped by biological and environmental factors and lived experiences over time, is typically excluded from legal consideration [4].

Although courts do not require proof that free will “exists,” there is open acknowledgment that criminal law sits on a fulcrum whereon all humans adults (outside of aforementioned rare exceptions) have the “power” to reason and choose freely between right and wrong [30]. In turn, this forms the moral and philosophical basis for retribution, blame, and punishment. Consider the case of homosexuality in mid-20th century Americana. At the time, same-sex sexual behavior (SSB) was criminalized, and prevailing narratives in syndicated media articles promoted the idea that changing SSB is simply a matter of applying “willpower” [31,32,33]. Books by Freudian pseudoscientists claimed conversion “cures” [34]. Although SSB was delisted as a mental disorder in 1973, the folk psychology idea of free will endured—in 1998, the majority of the American public (56%) still adhered to the folk belief that gay men and lesbians could change their behavior by willpower [35]. The full decriminalization of SSB was not complete until the 2003 Supreme Court case of Lawrence v. Texas [36]. It is easy to hypothesize that such folk beliefs—completely at odds with contemporary science [37]—helped to prop up the criminalization of homosexuality and widespread discrimination. Indeed, it is now possible to argue that vigorous adherence to folk psychology ideas, especially those related to moral blame and judgment of others, are causal factors in widespread social harm [4].

The distinct feature of many folk psychology beliefs is that they conflict with scientific findings [38]. The gap between folk beliefs such as “converting” SSB through willpower, and scientific reality, can be narrowed by education. Between 1998 and 2015 the percentage of Americans who believed in a willpower based “conversion” of SSB declined by 26% [39]. We will return to the subject of education in the frame of retributive punishment later. For now, it is worth examining a folk psychology belief that is undergoing significant social transformation in real time—the idea that obesity is a matter of free will and willpower.

3. Folk Psychology Vs. Obesity Science

“She [the obese person] need not carry that extra weight about with her unless she so wills.”Frances Stern, Obesity Expert, 1924 [40]

The quote above, drawn from the American Medical Association’s journal Hygeia, provides a snapshot of the enduring folk-psychology-rooted idea that willpower, or lack thereof, explains obesity. The authors claimed that people living with obesity should feel shame, arguing that experts “unanimously agree that she should be ashamed of her weight.” They viewed shame is a motivating factor. Moreover, they argued that people who dropped out of their clinic were “apparently lacking the willpower to keep the diet” [40]. This latter claim leaves no ambiguity about who is to blame for treatment failure.

In the industrial era and through mid-century Americana, willpower was widely noted to be a central feature of “cures” for obesity [41,42]. Moreover, these ideas endure. International research shows that the “commonsense” folk psychology idea that obesity is a willpower issue remains widely held by most members of societies [43,44,45,46,47,48]. Yet, with advances in neuroendocrinology and neuromicrobiology, and especially with the global success of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1) agonist drugs [49,50], the folk psychology ideas of willpower are now at odds with scientific knowledge and consensus on obesity. International experts are explicit in their calls to dismantle the false “commonsense” idea that obesity can be remedied simply by “agency” and exercising willpower: “Challenging and changing widespread, deep-rooted beliefs, longstanding preconceptions, and prevailing mindsets requires a new public narrative of obesity that is coherent with modern scientific knowledge” [51].

Despite scientific consensus that obesity is not merely a matter of acting on free will and applying agency, the “normative” view of folk psychology remains entrenched. For example, research demonstrates that people using GLP-1 medications are viewed negatively and obesity stigma surrounding GLP-1 medications endure [52], especially among those who have successfully lost weight without medications and/or those who believe obesity can be controlled through diet and exercise [53,54]. This suggests that the gap between scientific consensus and current stigma is wide, and will likely remain so in the short term. However, it is likely that these agents will lead to a shift in thinking, beyond obesity per se. As millions more adults use these agents, and there is continued maturation of research demonstrating their value for impulsivity, addiction, and mental health more broadly [55,56,57], we suspect that they will heighten awareness of the biological aspects of justice involvement [58]. Indeed, the emerging research on obesity joins rapidly accumulating evidence surrounding the biological basis of behaviors that are the subject of punishment and retribution.

4. Folk Psychology and the Retributive Impulse

“Criminal law thus proceeds upon the principle that it is morally right to hate criminals, and it confirms and justifies that [public] sentiment by inflicting upon criminals punishments which express it.”Lawyer and Judge, Sir James F. Stephen, 1883 [59]

Writing near the peak of colonialism, James Stephen, oft-claimed to be a brilliant legal scholar, argued strongly for society’s need to continue to hate criminals. He asserted that hatred and a desire for deliberate revenge were important ingredients in maintaining a “healthy” justice system. He feared that a lack of hatred for criminals would lead to apathy and lawlessness. In his view, the emotions related to hatred and vengeance bring about a resultant gratification when criminal punishments are meted out by society’s representatives. In this way, the combination of public hatred and punishment gratification work in the favor of public safety [60]. Of course, Stephen elided the fact that many, if not most, of the people to be “hated” were previously victims of abuse and violence [61].

While justifications for contemporary retributivism may not depend on hatred, at least not overtly, the retributive impulse and hatred of justice involved people endures [62]. The hatred is manifest in Scarlet Letter policies such as restrictions on community involvement, voting rights, housing, employment, and financial aid, to name a few [63,64]. Justice involved persons are in many ways the prime example of an easily “othered” out-group, and there is no reason to think that Stephen’s fear of a society with a lack of hate toward “offenders” has been realized [61,65]. The historical marginalization and policy-driven stigma has been made easier by the folk psychology assumption that the defendant or convicted offender could have easily made other choices (Figure 1). Criminal law concedes that law-abiding choices are perhaps easier for some than others, but that really does not matter in the courtroom. Why? According to defenders of the system, the choice to abstain from unlawful behavior is, on the whole, easy enough [66].

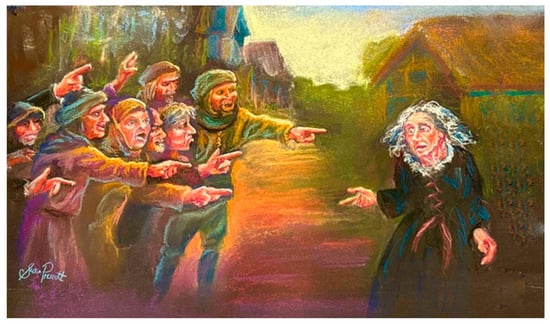

Figure 1.

In agreement with the views of Clarence Darrow, a growing number of scholars argue that folk psychology beliefs underpin, justify, and make normative, the infliction of punishment (Artwork by author, S.L.P.).

One reason why willpower and free will beliefs endure is likely because at the individual level they are associated with outcomes that are surely positive. For example, holding strong personal beliefs in free will has been linked to better job performance [67], academic performance [68], wellbeing [69], adherence to a healthy lifestyle [70], and meaning in life [71]. Yet, associations between individual level free will beliefs and personal successes may also explain the punitive aspects of such beliefs when an individual applies them to others. For example, if an individual enjoys high levels of trait-based self-control, they expect the same in others [72]. If life course success is attributed to free will and largely unconstrained agency, then it is easy to apply moral judgment, side-step scientific knowledge, and assume that everyone else deserves their lot in life. This is why the emerging obesity science is so informative.

Of course, it is understood that obesity is distinct from behaviors associated with justice involvement, such as aggression, antisocial, and/or violent behavior. However, the critical overlap with criminal justice discourse is the way in which folk psychology beliefs underpin blameworthiness, stigma, dehumanization, and ideas surrounding punishment. Not only do folk psychology beliefs in free will strengthen blame, they are also associated with punitiveness [73]. For example, stronger free will beliefs are associated with support for capital punishment and higher incarceration rates, and punitive responses to everyday moral transgressions [74]. Moreover, individuals who hold stronger beliefs in free will are more likely to blame people with schizophrenia or obesity for their own condition [75]. Researchers have also found that a greater belief in a personal agency framework of addiction (vs. the view of a neurobiological disease) is associated with a higher moral responsibility attribution [76]. Interestingly, free will beliefs seem to buffer or alleviate the distress that might otherwise be associated with meting out punishment [77]. Prison guards with higher beliefs in agency (i.e., agreement with the statement: Individual choices, not one’s circumstances, determine success in life) are more likely to be punitive and discount the mental health harms of extended use of solitary confinement [78].

These types of attributions help explain why people living with mental illness and/or obesity have been, and continue to be, subjected to folk psychology-rooted discrimination and marginalization. Indeed, the overlap between folk psychology beliefs related to obesity and criminal behavior (and blameworthiness) can be visualized via experimental mock trial/jury research. In vignette scenarios, female defendants who are overweight or obese are perceived to be repeat offenders, and more likely to be found guilty [79], and more generally, overweight subjects are likely to be considered blameworthy and punished [80]. While there are neurobiological overlaps between obesity and behaviors that might lead to higher risks of justice involvement [81,82,83,84], the extent to which folk psychology and fatphobia biases enhance the risk of conviction is worthy of scrutiny. For now, it is important to note that rigid adherence to free will beliefs is associated with a retributive impulse, while gaining scientific knowledge about the neurobiological basis of behavior seems to diminish support for retributive punishment [85,86]. On the other hand, prescientific notions of “evil forces” and “evilness” in a person lead to greater punishment [87,88].

5. Prescientific Structure Under Pressure

“At a day not far remote the teachings of bio-chemists and behaviorists, of psychiatrists and penologists, will transform our whole system of punishment for crime.”Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo, 1928 [89]

Notwithstanding legitimate concerns related to the spread of misinformation and an anti-science drift in the post-COVID era, international scientists enjoy very high levels of public trust [90], and societies as a whole are increasingly driven by evidence-based policies and practices [91]. Even though there may be differences along lines of political ideology, the 21st century has witnessed a significant increase in the inclusion of scientific citations within policymaking discourse [92]. Yet, the field of criminal law and its associated systems (e.g., courts, corrections) seem to sit outside of the frame of evidence-based brain sciences, instead continuing to lean on prescientific folk beliefs and what is considered “normative” within its own framework. Put simply, law has justified and reinforced folk psychology judgements as normative, in part by walling off advances in biopsychosocial and related brain/behavioral sciences [4,14].

This is not to say that the criminal justice system is disinterested in science, especially the sort of forensics that might place a suspect at the scene of a crime. In a strange way, courts have largely ignored brain sciences while, at the same time, liberally adopted many aspects of junk science. Once in place, junk science becomes entrenched, with courts seemingly unwilling to concede that the likes of bite marks, tool comparison, hair microscopy and much more, have little scientific merit. Prosecutors and law enforcement maintain dogma through “shadow forensics”—the intentional shielding of forensic techniques from evidentiary oversight [93]. In the United States, judges (through Supreme Court decisions known as the Daubert trilogy) have appointed themselves as adjudicators of what is deemed credible science. The problem with this scenario is well documented—judges, like professionals within law in general, often lack scientific education and knowledge. Indeed, there appears to be a Dunning-Kruger effect wherein legal professionals overestimate their scientific abilities [94]. Prosecutors appear to have a disinterest in brain and behavioral sciences that point toward diminished capacity or mitigation [95,96]; this becomes even more troubling when considering that, at least in the United States, most judges are former prosecutors [97].

As mentioned, law and criminal justice systems are structures that sit atop the prescientific foundations of folk psychology. These foundations, however, are under scientific pressure. Breakthroughs in neuroscience, polygenic risk assessment, neuromicrobiology, and the mapping of the public health exposome—boosted by rapid advances in omics technologies—are converging with decades of work under the rubric of DOHaD. Together, these streams of knowledge are beginning to unsettle long-standing legal ideas about human choice, self-control, and minimal thresholds of rational thought [98,99,100].

It is unlikely that criminal justice systems will be able to address the weaknesses in its structural integrity by simply tinkering around the edges of the foundations—placing some patchwork on via rulings that acknowledge the scientific realities of brain development. Two examples of edge-tinkering include US Supreme Court decisions that ended capital punishment and mandatory life sentences without parole for juveniles. These are signs that the courts understand that brain development is a lengthy process. However, scientific challenges to folk psychology and blameworthiness, whether via obesity or other health-related sciences, are exposing flaws that go far beyond arbitrary age-related rulings on brain science vs. moral blame.

The scientific pressure on criminal justice systems is no longer isolated to single gene explanations for aggression, or neuroimaging reports suggesting altered activity in the prefrontal cortex. The preclinical animal studies linking differences in neurotransmitters with behavior were of no threat to systems oriented toward punishment and retribution. The system could deflect these because, for the most part, they lacked explanatory power (save for rare cases such as a large brain tumor or major structural damage) in specific criminal cases [100]. The difference with contemporary biological criminology is that it is not one-dimensional. Rather, it is capable of simultaneously integrating polygenic indices with multi-omics research (combining genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data) along with nutritional neuroscience and microbiome sciences [12]. These advances, aided by massive data collections and machine learning, are bringing biological context (via objective markers) to neuroimaging scans [101,102,103,104]. The integration of findings will bring explanatory power to individual cases and help society understand, for example, why large-scale research shows that appropriate prescriptions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications are associated with much (25–41%) lower risks of subsequent criminal convictions [105,106,107].

While genes are not deterministic, as once thought, they are certainly not irrelevant. Indeed, some 40% to 60% of the variance in aggressive, criminal, and antisocial behavior can be explained by genetic factors [108,109,110]. Polygenic indices are proving to have predictive power—their influence on externalizing behaviors in childhood is comparable to that of well-known environmental risks such as abuse or peer victimization [111]. Neurodivergence, or neuroanatomical variability, predicts behaviors that are otherwise associated with later justice involvement [112,113]. Here, contemporary biological criminology considers exposome science—the study of the total accumulated environmental exposures (both detrimental and beneficial)—that can help predict the biological responses of the “total organism to the total environment” over time [9]. That is, it considers all of the psychosocial factors—ranging from generational trauma to poverty [114,115,116]—that bring a person to a moment in time, and the ways in which these lived experiences “get under the skin” to biologically influence real-time cognition and behavior [117,118].

From our perspective, it is virtually inevitable that this body of work will continue to grow and assemble around law and criminal justice, exposing an assumption that is widely accepted as the cornerstone of criminal law: “the responsible human subject as the noumenal self, characterized exclusively by a rational free will unencumbered by character, temperament, and circumstance” [30]. It is our contention that criminal justice structures will find it increasingly difficult to fend off volumes of international research demonstrating that rational free will (or willpower, or agency, whatever the preferred term) is subject to significant constraints at the individual level, and humans at the moment of a potentially criminal act are in fact encumbered by “character, temperament and circumstance” [119]. Undoubtedly, philosophical debates concerning free will and its “existence” will endure. However, even in the face of uncertainty about free will and its power, desert-based retributive punishment should be deemed unjustified. Put simply, there is enough uncertainty surrounding free will to follow the scientific path of the precautionary principle of harm reduction [120].

While fully acknowledging that an untold number of unanswered research questions remain, we posit that the existing evidence is robust enough to push serious society-wide discussions related to non-retributive models of criminal justice. One such approach is the public health quarantine model, a topic we turn to next. First, we will provide a brief overview of its early origins in the first portion of the 20th century. This history is important because the contemporary public health quarantine model has been developed in a way that disentangles it from nefarious or harmful (some well-intended, others not) practices that consumed so much of the ‘reform’ discourse in the early 20th century.

6. Crime and Public Safety as a Matter of Health, Quarantine

“The criminal deserves sympathy—just as the victim of a contagious disease, who for the protection of the public is in quarantine, deserves sympathy. The public is entitled to protection in either case until the danger to the community has passed…it would be folly at the inception of a case of diphtheria to prophecy the exact day and hour when it would be safe to permit the patient to mingle with society. It is even greater folly to endeavor to do this with the criminal.”Walter N. Thayer, MD, 1924 [121]

In the early part of the 20th century, Walter Thayer was a well-known prison physician and reformer. He would go on to become the New York State Commissioner of Corrections. He vigorously opposed the eugenic practices of sterilization, arguing against ideas that heredity equates to criminal destiny [122]. On the other hand, he contended that fixed sentences or simply abiding by prison rules (the latter used by parole boards as a primary indicator of ‘reform’) were not serving the interests of public safety. It was his position that courts should only decide guilt or innocence, and that the separation of guilty parties from mainstream society should be determined by committees of experts within medicine and psychosocial sciences.

Rather than a specific crime being the sole determinant of sentencing, Thayer believed each individual case should be “painstakingly” examined by teams of sociologists, psychologists, and physicians [123]. This personalized approach, admittedly labor-intensive, would consider the developmental and overall biopsychosocial factors that lead to justice involvement, and the demonstrated capacity for successful reentry. He argued that investments in a holistic understanding of each individual would save society money over the long term.

Thayer’s views, and similar perspectives among a number of his contemporaries, were drawn from the public health disease model of quarantine. Mainstream magazine articles argued that “the prison must be looked upon as a place wherein [criminals] are quarantined until their ailments have been diagnosed and a proper treatment applied…the mere recognition of crime as a disease will do much to remedy present conditions” [124]. Reformers such as Thayer envisioned a non-retributive criminal justice system wherein medical experts—not judges or lawyers—were deeply involved in sentencing and determinations of reentry or readiness for return to society. These advocates did not deny the right of society to protect itself, and the need to sequester individuals who have been confirmed to have committed harms against individuals or society. The main message was that criminal behavior should be viewed through a health and disease lens, one that considers social structures, environmental factors, and individual neuropsychiatric differences.

Viewed in a generous light, these positions were intended to be an alternative to harsh sentencing, horrendous carceral conditions, and prevailing views that crime could be ‘exterminated’ through retribution and capital punishment. Of course, as sociologists know well, the practical application of ‘crime as disease’ models in the first half of the 20th century were parceled into eugenical policies, compulsory ‘treatments’ (with long term harms, most lacking any semblance of informed consent), racist practices, perceptions of permanent dangerousness, labeling, and reinforcement of the idea that justice involved persons and their families are ‘inferior’ [125,126,127]. This era of psychology was rooted in Freudian pseudoscience, with many (now discredited) assumptions [128,129,130]. Biological aspects of criminology at the time were rudimentary and short on validity and reliability [131].

These early ideas of a public health quarantine approach to crime were not developed through an ethical framework. In the absence of high-quality science, the sort that would guide unbiased decision-making on sentencing and reentry, the concept languished. Critics, including prisoners, were justifiably concerned that indeterminant sentences could lead to permanent confinement of people who are merely perceived to represent a danger. Indeed, Thayer openly admitted that his non-retributive quarantine plan (referred to as the Napanoch Plan) would lead to the permanent quarantine of some prisoners. However, he vehemently opposed “3 strikes” type laws that trigger mandatory life sentences for repeat offenders: “It is to my mind psychologically wrong. It is neither right nor proper to say, when a man is convicted, that he may never be released” [132].

Although there was mid-20th-century enthusiasm for rehabilitation and education programs, by the 1970s, the societal pendulum swung back toward retribution and punishment [133]. This change in this era was facilitated, at least in part, by both the widespread dissemination of academic reports suggesting that investments in rehabilitation and parole were not reducing recidivism [134,135], and a coincident increase in violent crime. Community corrections, such as parole, were viewed with skepticism, and policies moved toward crime control. The end result, at least in the United States, produced mass incarceration, abolishment of parole in many jurisdictions, and a massive uptick in life without parole sentences (between 1992 and 2016, a 328% increase) [136]. In other words, the early 20th century fears that a quarantine model of rehabilitation (operated by healthcare professionals) would lead to permanent isolation were being realized anyway, albeit through different means—directly through mandatory sentencing laws and at the discretion of ‘crime control’ judges.

The last decade has witnessed a shift in societal attitudes toward mass incarceration and the need for carceral reform. Multiple nationwide surveys in the United States indicate that a majority of respondents now support rehabilitation and the release of prisoners (both violent and non-violent) well before their sentences are complete—provided there is some assurance that societal risk has been mitigated, and successful reentry is supported [137]. There is increased recognition that the view of crime through the health/disease lens is not without merit [138]. At the same time, there has been a massive rise in academic scholarship surrounding prison abolitionism (ultimately aiming at the complete dismantling of the current carceral state) [139] and criminal law minimalism (which seeks preventive justice and a turn from retribution) [15].

Running parallel to these discussions of abolition, minimalism, and mental health is the aforementioned recognition by an increasing number of scholars in law, psychology, biology, medicine, and philosophy that ideas of near universal levels of willpower (also, abundant “free will” and agency) are antiquated concepts [4,13,119,130]. We use the word parallel because the abolition and minimalist discourse largely elides the individual constraints of brain architecture and neurophysiology as developed by Sapolsky [140] and others. That is, challenges to the status quo and calls for deep reform—not simply tinkering around the edges—are originating from different fronts. Taken together, we suggest that the time may be right for a more fully developed public health quarantine model of criminal justice, framed by ethics, to move from ideation to trial.

7. The Public Health Quarantine Model

The public health quarantine model of criminal justice reimagines the system by shifting its central purpose from retribution to prevention. Rather than grounding justice in the traditional “just deserts” view of moral responsibility, it assumes that behavior is largely shaped by factors beyond individual control [13,16,141]. In reference to free will, it operates from the position known as hard incompatibilism—that is, the sort of free will required for moral responsibility (and subsequent deserts-based punishment) is not compatible with the ever-growing mountain of evidence connecting current actions with prior factors beyond our control [142,143,144]. Drawing inspiration from early 20th-century ideas of ‘free will’ skepticism, and non-retributive care-based sequestration, Derk Pereboom and the current author (GDC) developed a model that is underpinned by the idea that people are not morally responsible (in the basic desert sense) for their actions [18]. Instead, it emphasizes addressing the social, environmental, and developmental roots of criminal behavior.

A defining feature of the model is its recognition of the overlap between the social determinants of health and the social determinants of criminalized behavior. Like John Snow’s removal of the Broad Street pump to halt cholera, the quarantine model seeks to act on the “causes of causes” of justice involvement [12]. Many of these upstream risks are found in the adverse conditions of early life. For example, children whose parents report four or more adverse childhood experiences are nearly twice as likely to face arrest by age 25 as those whose parents report few or none [145]. The model also acknowledges the so-called victim–offender overlap—the well-established finding that many justice-involved individuals were first victims themselves, and that cycles of harm can spread in a contagion-like fashion [146,147]. At the same time, it emphasizes the protective role of positive childhood experiences—safe, stable, and nurturing environments that extend beyond the mere absence of trauma—since these experiences are linked to lower delinquency, stronger self-control, and better mental health in adulthood [148].

Although the model borrows its language from infectious disease control, it insists that state power must be exercised with ethical restraint. Just as it would be unethical to subject someone quarantined for illness to suffering beyond what is necessary for public protection, so too it is wrong to impose punitive suffering on those detained by the justice system. Retribution has no place in this framework. Incapacitation may be justified, but only when there is an ongoing risk of serious harm, and only at the level of restriction required for safety [16]. Rehabilitation and wellbeing must remain central to any confinement, even in cases of indefinite detention. The model offers no justification for misery, cruelty, or punishment for its own sake [99]. Despite its framing, however, the public health quarantine model has received little sustained engagement from the public health community. Yet it is likely that prevention scientists and health professionals would find common cause with its emphasis on early-life investment, the reduction in unjust punishment, and the pursuit of structural reform [4].

One of the most difficult aspects of the model lies in its reliance on the preventive detention of those who have committed crimes. This is the same criticism directed at Thayer in his 1920s Napanoch Plan. Caruso maintains that only those posing a serious threat should be confined, and that the state must carry the burden of proof, reviewed at regular intervals, to justify continued incapacitation [13]. The model proposes building in maximum upper limits of detention for extremely violent offenders, after which the state (and its experts) must provide clear documentation–such as evidence of aggression and violence in prison, credible threats to continue to do harm upon release, etc.—to justify further detention. This need for confinement beyond upper limits, outside of any retributive impulse, and the methods by which release is determined, are among the more difficult aspects of the model. As far as preemptive detention for those who have committed no crime, the model resists this through its emphasis on liberty and the presumption of harmlessness [149].

Critics rightly observe that predicting dangerousness is far more complex than predicting disease transmission. Decisions about who is detained, what evidence suffices, and how risk is determined remain contentious [150]. Biological markers can heighten perceptions of dangerousness [151,152]. The model therefore requires tools of risk assessment, but existing instruments, although in widespread use for parole and bail decisions, are far from accurate. Traditional actuarial tools and algorithmic models, especially in predicting violence, are prone to racial bias, in part because they rely on arrest records that reflect systemic discrimination as much as actual behavior [153,154]. Even widely used instruments such as the Static-99 or the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide, when judged by standards applied in medicine, achieve only “fair” predictive accuracy at best [155,156]. While machine learning and emerging approaches such as neuroimaging, EEG, microbiome, or biomarker analysis may improve predictions, they carry their own ethical concerns.

To succeed, the quarantine model must ensure that advances in neuroscience or microbiology enhance fairness and protect liberty, rather than entrench bias [157]. This will require greater investments in research surrounding risk and its assessments, including those that might incorporate paper-and-pencil tests, clinical judgment, and objective biological markers. It will also require a whole-person approach that includes rigorous multivariable testing of predictors, while at the same time eliminating sources of biases and reducing the power of dated (potentially discriminatory) sources of evidence [158].

The model also raises broader questions about dignity and human rights. Critics argue that denying free will undermines dignity, yet others counter that recognizing the constraints on human agency is more humane than moralizing biological and social disadvantages into “sin” [140]. For individuals with measurable neurobiological vulnerabilities, exposure to toxins, food insecurity, or repeated victimization, dignity is far more threatened by confinement in degrading conditions than by rejecting free will as a fiction [4]. Caruso challenges the retributive claim that punishment itself preserves dignity, arguing that inflicting suffering on the grounds of “respecting” someone as a morally responsible agent is a perverse distortion of dignity [13]. From a public health perspective, practices such as shaming or harsh incarceration appear less as affirmations of agency than as expressions of hostility, fear, or indifference to cruelty [4].

Yet the model does not ignore the cultural attachment to retribution. Retributive impulses are deeply embedded in Western law and psychology. As stated by US Supreme Court justice Benjamin Cardozo, “The thirst for vengeance is a very real, even if it be a hideous, thing; and states may not ignore it till humanity has been raised to greater heights…disregard such passions altogether, and the alternative may be the recrudescence of the duel or the feud” [89]. Research consistently shows that people often experience emotional satisfaction—the “joy of punishment”—even when punishment has little preventive effect [130,159]. Moreover, across cultures, justice is frequently understood as reciprocal fairness. Victims and communities often expect some form of punishment as recognition of harm, and may view its absence as unfairness. A justice model that appears to disregard these expectations risks eroding public trust and legitimacy [160].

For this reason, the promise of the public health quarantine model may depend on integration with non-retributive practices such as restorative justice. Restorative approaches emphasize healing, dialogue, and accountability, giving victims and communities a meaningful voice while avoiding the cruelty of retribution. Evidence suggests that restorative justice can reduce recidivism while offering psychological benefits for both harmed and harming parties [161,162,163]. By foregrounding prevention, dignity, and repair, restorative justice may provide a bridge between the public health model’s aspirations and society’s enduring expectations of justice. The model acknowledges the wrongs done to victims. At the same time, though, the public health model is distinct from efforts that encourage semi or soft forms of retribution, or those that posit (at odds with most surveys) victims desire retribution and the witnessing of suffering of justice-involved persons [17].

8. Barriers to Policy and Practice Translation

“Assuming it is possible to change ourselves as [hard incompatibilism of the public health quarantine model] desires, however, we would be a new people. The history of attempts to remake human beings to achieve a radical new vision of society is one of failure, and indeed, horror.”Stephen J. Morse, 2018 [164]

The public health quarantine model proposes a profound shift in how we understand criminal justice: away from punishment and desert, toward prevention, rehabilitation, and structural reform. It rejects cruelty, insists on the principle of least infringement, and seeks to treat those who harm others with the same ethical restraint as those quarantined for illness. As such, the concept may represent a threat to the status quo and conjure up images of a history of forced (and highly unethical) medical treatments of crime. Obviously, this history is dark and steeped in racism, sexism, and classism. However, it was concentrated at a time when medicine was broadly unethical and absent informed consent and ethical guardrails [165]. Public health has its own dark history, but it does not mean that its contemporary frameworks are comparable to the early 20th century.

The concept also meets with the well-known resistance to change among hardened institutions such as corrections and Anglo-American criminal law. Defenders of the current folk psychology-based paradigm—such as influential law professor Stephen J. Morse, quoted above—describe the model as “frightening” [164]. Morse claims that we would be a new people, radically transformed, if we abandoned the folk psychology underpinning criminal law and its associated practices of desert-based punishment. Yet, history is laden with abandonment of folk psychology ideas and other prescientific beliefs, and none have made us into a “new people” [130]. Abandoning judgment-based folk psychology beliefs is distinct from grand plans to remake human beings, and veiled attempts to equate the former with the latter appear unserious. In the annals of relatively recent history, society has abandoned ideas that people with epilepsy are diabolical, possessed with evil, and worthy of criminal punishment [166]. Prescientific folk beliefs that produced the Salem witch trials have been abandoned, and Tourette’s syndrome is no longer criminalized as diabolical possession [167]. No dystopian reality has emerged as a result.

The translation of the public health quarantine model will require a deeper understanding of the rationale and methods used to maintain folk psychology beliefs. Criminal justice systems have been able to safeguard folk psychology by vigorously defending the idea that, outside of the (unscientific) category of insanity and extreme neurocognitive disability, all those funneled into criminal justice systems are morally blameworthy, capable of being described as evil monsters, yet “normal.” As pointed out by scholar Paul Churchland, “So long as one sticks to normal brains, the poverty of folk psychology is perhaps not strikingly evident. But as soon as one examines the many perplexing behavioral and cognitive deficits suffered by people with damaged brains, one’s descriptive and explanatory resources start to claw the air” [168].

Emergent science is demonstrating that a “damaged” brain is far more common than previously appreciated. The public health quarantine model is interested in why the odds of criminal justice involvement among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are 61% higher than those without PTSD, and the odds of arrest for violent offenses are 59% higher [169]. As science advances, the criticism of the public health quarantine model is placed into a position of cherry-picking and justifying the specific folk psychology ideas that are status quo-preferred. This defense in the face of emergent science often results in the fallacy of Phineas. This describes an erroneous assumption that only “structural” or tissue damage in the brain (e.g., that is visible via select brain imaging, or in the famed case of Phineas Gage, an actual tamping rod through the skull) provides explanatory power in the realm of cognition, behavior, and biophysiology [4].

As Thayer pointed out, the large-scale implementation of care-based quarantine approaches would be hampered without changes to criminal codes and statutes [170,171]. To the extent that laws mandate punishment through specific sentencing (e.g., determinate sentences, life without parole, 3-strikes laws), a diverse group of health/behavior experts—a committee or commission—would be constrained in their ability to make decisions on release and sequestration. Laws would need to empower such committees to make binding decisions once guilt or innocence was established through the usual pathways of due process. The public health quarantine model does not interfere with habeas corpus, appeal processes, and/or executive clemency/pardons. It does, however, remove judges—most of whom have little educational background in neuropsychiatric and behavioral sciences—from decision-making on post-conviction sentencing.

While Thayer argued that there should be no determinate or maximum sentences, he did suggest that for cases below second-degree murder, the setting of low minimum sentences would assist in satisfying the public’s confidence in the system. In 1927, Thayer’s plan received some traction when the governor of New York, Alfred E. Smith, asked for an investigation into the feasibility of a Sentencing Board (made up of physicians and criminologists) that would replace judges as the determinants of all felony sentencing. Smith felt that the best minds in health and science might approach the sentencing decision with “calmer discretion” and avoid the commonplace judicial decision to “teach an offender a lesson” and “send a deterrent message” to society [172]. “It appeals to me as a modern, humane, scientific way to deal with the criminal offender,” Smith said [173]. Smith also called for the maintenance of minimum sentences, even if discretionary power was moved to an expert-led sentencing board. Predictably, judges opposed Smith’s idea in public hearings—referring to it as “an attack on the judiciary”—and it stalled [174].

Obviously, there is some overlap with these ideas and the intended function of parole boards. However, as noted above, the distinction with the public health quarantine model is that committees of health experts are not operating through worldviews of moral blameworthiness and ideas of ‘evil’ or monstrous persons. While its implementation faces serious obstacles—especially entrenched retributive attitudes and the difficulty of accurately assessing dangerousness or harm potential—it offers a framework that places dignity and prevention at the center of justice. Its future may depend on careful integration with restorative approaches that meet the human need for accountability while avoiding the destructive consequences of retribution.

Earlier, we mentioned the value of education in countering unscientific folk psychology beliefs. Translation efforts, including those that springboard from existing models of restorative justice, will require education among criminal justice professions (particularly the courtroom working group) and the public writ large. Here, it is worth noting that individuals with educational backgrounds in biology and behavioral sciences are less likely to endorse punitive sentencing [86] and more likely to prefer rehabilitative care [175]. For example, scientific education can narrow the gap between perceptions of the dangerousness of a person with a neuropsychiatric disorder and the reality that biology (e.g., polygenic loci, current neuroarchitecture, etc.) does not equate to destiny. Moreover, research shows a wide gap between public knowledge of judicial operations (and forensic/legal psychology) and tabloid media-driven retributive impulses [176]. The latter is easily leveraged for political gain and policies that run counter to a public health quarantine model. Since most criminal court judges in the United States are elected, and therefore prone to electability perceptions vis à vis crime control, an independent group of health experts deciding cases should remain detached from political emotion, and attached to science.

Since the public health quarantine model emphasizes prevention, communities and their policymakers will need to be assured that investments in addressing the ‘causes of the causes’ do indeed translate into public safety. Available evidence from public health and prevention science does support continued investments [177,178,179]. However, to be fully implemented, the public health quarantine model will require clear and robust evidence-based lines between prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and public safety. Gaps between real-world statistics and perceived public safety will also need to be scrutinized.

9. Conclusions

“We shall look on crime as a disease, and its physicians shall displace the judges, its hospitals displace the galleys. Liberty and health shall be alike. We shall pour balm and oil where we formerly applied iron and fire…this change shall be simple and sublime.”Victor Hugo, 1832 [180]

Criminal laws and associated desert-based punishments, especially in regions influenced by Anglo-American worldviews, are underpinned by folk psychology assumptions. Combined advances in neuropsychiatry, neuromicrobiology, behavioral genetics, exposome, and DOHaD sciences, along with multi-omics technologies, are illuminating the ways in which here-and-now decisions are determined by antecedent factors. Collectively, this research challenges folk psychology ideas, including those related to so-called free will, willpower, and agency. While some have argued that the totality of this research translates into “not a single crack of daylight to shoehorn in free will” [130], others concede that the constraints on agency are far more significant than currently appreciated [4].

Up to now, Anglo-American systems of criminal justice, including courts and corrections, have kept brain and behavior sciences at the periphery. Such marginalization is not merely passive—by offering up prescientific ideas to explain behavior, referring to monsters and wickedness among justice-involved persons, judges and prosecutors encourage anti-science sentiment. Behavior that can be explained through emergent biopsychosocial science represents more than an inconvenience to the folk psychology fulcrum; it is a direct threat to the normative assumptions of the system.

Although criminal justice systems and their units (especially corrections) are well known for their resistance to change, it is unlikely that the folk psychology assumptions can withstand the rapid growth of transdisciplinary brain and behavior sciences. The courts could (mostly) resist the causal value of a neuroscience that sat alone within a disciplinary silo. Outside of brain imaging demonstrating massive structural damage (e.g., from a tumor), early 2000s neuroscience was not a threat to folk psychology assumptions. Nor were single gene explanations for behavior. The contemporary neuroscience that is toppling folk psychology assumptions is informed by multiple disciplines—from microbiology to toxicology and nutrition to traumatology, further enhanced by omics and machine learning.

Between the collapse of folk ideas and calls for the complete abolition of justice systems, the public health quarantine model has emerged as a new concept, built upon historical ideas of justice and ethical public health principles. The concept is emerging at a time when there is significant convergence of multiple lines of supportive biopsychosocial evidence. The public health quarantine model, which upholds society’s fundamental right to protect itself while doing so with minimal harm, is worthy of transdisciplinary debate, translation, and real-world evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.L.; investigation, S.L.P. and A.C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.L. and S.L.P.; writing—review and editing, G.D.C., A.C.L., and S.L.P.; visualization, G.D.C., A.C.L., and S.L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Edwards, B.D.; Travis, L.F. Introduction to Criminal Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Strick, L.B.; Ramaswamy, M.; Stern, M. A public health framework for carceral health. Lancet 2024, 404, 2234–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloud, D.H.; Garcia-Grossman, I.R.; Armstrong, A.; Williams, B. Public health and prisons: Priorities in the age of mass incarceration. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2023, 44, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, A.C.; Prescott, S.L. The Big Minority View: Do Prescientific Beliefs Underpin Criminal Justice Cruelty, and Is the Public Health Quarantine Model a Remedy? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.C.; Raine, A.; Farrington, D.P. The interaction of biopsychological and socio-environmental influences on criminological outcomes. Justice Q. 2022, 39, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denson, T.F.; Griffiths, M.A.; Smith, L. Attitudes toward incarceration, neuronormalization and psychological treatment for violent offenders. Psychol. Crime Law 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, E.T.; Gabard-Durnam, L.J. Prenatal influences on postnatal neuroplasticity: Integrating DOHaD and sensitive/critical period frameworks to understand biological embedding in early development. Infancy 2025, 30, e12588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, C.; Fernández, C.R. Neuroscience advances and the developmental origins of health and disease research. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e229251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, H.; Holt, P.G.; Inouye, M.; Logan, A.C.; Prescott, S.L.; Sly, P.D. An exposome perspective: Early-life events and immune development in a changing world. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagenbeek, F.A.; Kluft, C.; Hankemeier, T.; Bartels, M.; Draisma, H.H.; Middeldorp, C.M.; Berger, R.; Noto, A.; Lussu, M.; Pool, R.; et al. Discovery of biochemical biomarkers for aggression: A role for metabolomics in psychiatry. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2016, 171, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagenbeek, F.A.; van Dongen, J.; Pool, R.; Boomsma, D.I. Twins and omics: The role of twin studies in multi-omics. In Twin Research for Everyone; Tarnocki, A., Tarnoki, D., Harris, J., Segal, N., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 547–584. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, A.C.; Berryessa, C.M.; Callender, J.S.; Caruso, G.D.; Hagenbeek, F.A.; Mishra, P.; Prescott, S.L. The Land That Time Forgot? Planetary Health and the Criminal Justice System. Challenges 2025, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.D. Rejecting Retributivism: Free Will, Punishment, and Criminal Justice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Callender, J.S. Neuroscience and Criminal Justice: Time for a “Copernican Revolution?”. William Mary Law Rev. 2021, 63, 1119–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Slobogin, C. The Minimalist Alternative to Abolitionism: Focusing on the Non-Dangerous Many. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2024, 77, 531–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.D. Free will skepticism and criminal behavior: A public health-quarantine model. Southwest Philos. Rev. 2016, 32, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.D. Why We Should Reject Semiretributivism and Be Skeptics about Basic Desert Moral Responsibility: A Reply to John Martin Fischer. Harv. Rev. Philos. 2023, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereboom, D.; Caruso, G.D. Hard-incompatibilist existentialism: Neuroscience, punishment, and meaning in life. In Neuroexistentialism; Caruso, G.D., Flanagan, O., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 193–224. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, K.; Spaulding, S.; Westra, E. Introduction to folk psychology: Pluralistic approaches. Synthese 2021, 199, 1685–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grannell, A.; Fallon, F.; Al-Najim, W.; le Roux, C. Obesity and responsibility: Is it time to rethink agency? Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, S.; Vallis, M. Moving beyond eat less, move more using willpower: Reframing obesity as a chronic disease impact of the 2020 Canadian obesity guidelines reframed narrative on perceptions of self and the patient–provider relationship. Clin. Obes. 2023, 13, e12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. European Commission classifies obesity as a chronic disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, P. Deliver us from evil: The case for skepticism. In Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Evil; Nys, T., de Wijze, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Boyko, C.A. Written response to Senator Patrick J. Leahy. In Confirmation Hearing on Federal Appointments; United States Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, J.B. Nothing But Evil: Oregon Man Gets Two Life Sentences; The Columbian: Vancouver, WA, USA, 2004; pp. A–2. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, D. There Is a Special Place in Hell for Somebody Like You; Jackson Citizen Patriot: Jackson, MI, USA, 2013; p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, J. Convicted Rapist-Murderer Sentenced to Life Plus; The Miami Herald: Miami, FL, USA, 1980; p. 2-B. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, S. Reformed Manson Follower Eyes Freedom After 56 Years: ‘She’s not the Same Person Anymore’. The Guardian, 4 June 2025. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jun/04/charles-manson-follower-patricia-krenweinkel-parole (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Fox, J.V. Tate prosecutor: Monsters must die. The Record, 19 March 1971; pp. C–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dan-Cohen, M. Responsibility and the Boundaries of the Self. Harv. Law Rev. 1992, 105, 959–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, G.W. Prevention best antidote against homosexuality. The Piqua Daily Call, 7 March 1974; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, G.W. Homosexual can be normal using sheer willpower. The Saginaw News, 3 August 1955; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, G.W. Breaking homosexuality requires only will power. The Saginaw News, 17 June 1960; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hesnard, A. Strange Lust: The Psychology of Homosexuality; Amethnol Press: New York, NY, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Leland, J.; Miller, M. Can gays convert? Newsweek, 17 August 1998; pp. 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Anthony, M.; Supreme Court Of The United States. U.S. Reports: Lawrence et al. v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558; United States Library of Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep539558/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Felesina, T.; Zietsch, B.P. Emerging insights into the genetics and evolution of human same-sex sexual behavior. Trends Genet. 2025, 41, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stich, S.P. From Folk Psychology to Cognitive Science: The Case Against Belief; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Support for Same-Sex Marriage at Record High, but Key Segments Remain Opposed: Section 2, Knowing Gays and Lesbians, Religious Conflicts, Beliefs about Homosexuality. 8 June 2015. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2015/06/08/section-2-knowing-gays-and-lesbians-religious-conflicts-beliefs-about-homosexuality/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Stern, F.; Meserve, R.T. Reducing as a science, not a fad. Hygeia 1924, 2, 419–422. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J.F. Dangers of obesity. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 1918, 19, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R. The complexities of the problem of obesity. Med. Clin. N. Am. 1960, 44, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Muñoz, J.; Aguarón-García, M.J.; Malagón-Aguilera, M.D.; Cuesta-Martínez, R.; Reig-Garcia, G.; Solà-Miravete, M.E. Weight Bias in Nursing: A Pilot Study on Feasibility and Negative Attitude Assessment Among Primary Care Nurses. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Opinion Research Center Survey on Obesity Among American Adults. University of Chicago. Issue Brief. October 2016. Available online: https://www.norc.org/content/dam/norc-org/pdfs/Issue%20Brief%20B_ASMBS%20NORC%20Obesity%20Poll.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Orth, T. Obesity-Based Prejudice: Most Say It Occurs at Least Somewhat Often in Dating, Work, and Health Care. YouGov USA Public. 14 April 2023. Available online: https://today.yougov.com/health/articles/45564-obesity-based-prejudice-frequent-yougov-poll (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Goff, A.J.; Lee, Y.; Tham, K.W. Weight bias and stigma in healthcare professionals: A narrative review with a Singapore lens. Singap. Med. J. 2023, 64, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, D.; Ertınmaz, B.; Erden, N.; Gönenli, M.G.; Sargın, M.; Akbaş, F.; Yumuk, V. Barriers to Obesity Management in Primary Health-Care. Endocrinol. Res. Pract. 2024, 28, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Almohammedsaleh, A.S.; Alshawaf, Y.Y.; Alqurayn, A.M.; Alshawaf, Y.Y.; Alqurayn, A. Barriers to a Healthy Lifestyle Among Obese Patients Attending Primary Care Clinics in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e69036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.J.; Sim, B.; Teo, Y.H.; Teo, Y.N.; Chan, M.Y.; Yeo, L.L.L.; Eng, P.C.; Tan, B.Y.Q.; Sattar, N.; Dalakoti, M.; et al. Efficacy of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Weight Loss, BMI, and Waist Circumference for Patients with Obesity or Overweight: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression of 47 Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, J.; Cordioli, M.; Tozzo, V.; Urbut, S.; Arumäe, K.; Smit, R.A.; Lee, J.; Li, J.H.; Janucik, A.; Ding, Y.; et al. Association between plausible genetic factors and weight loss from GLP1-RA and bariatric surgery. Nat. Med. 2025, 18, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, F.; Puhl, R.M.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Ryan, D.H.; Mechanick, J.I.; Nadglowski, J.; Ramos Salas, X.; Schauer, P.R.; Twenefour, D.; et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, S.M.; Persky, S. The effect of GLP-1 receptor agonist use on negative evaluations of women with higher and lower body weight. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, S.M.; Stock, M.L.; Persky, S. Comparing the Impact of GLP-1 Agonists vs. Lifestyle Interventions and Weight Controllability Information on Stigma and Weight-Related Cognitions. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2025, 32, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldkorn, M.; Schwartz, B.; Monterosso, J. Views Among the General Public on New Anti-Obesity Medications and on the Perception of Obesity as a Failure of Willpower. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2025, 11, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Volkow, N.D.; Berger, N.A.; Davis, P.B.; Kaelber, D.C.; Xu, R. Associations of semaglutide with incidence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder in real-world population. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranäs, C.; Caffrey, A.; Edvardsson, C.E.; Schmidt, H.D.; Jerlhag, E. Semaglutide suppresses cocaine taking, seeking, and cocaine-evoked dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2025, 98, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Mapping the effectiveness and risks of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sileoni, A.M.; Turco, E.T.; Semeraro, F.; Cavallotto, C.; Mosca, A.; Chiappini, S.; Martinotti, G. Semaglutide for Craving Reduction in a Cocaine Dependent Patient: A Case Report. Clin. Neuropsychopharmacol. Addict. 2025, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, J.F. A History of the Criminal Law of England; Macmillan and Co.: London, UK, 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, J.F. Liberty Equality Fraternity; Holt Williams: London, UK, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Godsoe, C. The victim/offender overlap and criminal system reform. Brook. L. Rev. 2021, 87, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, J. Hating Criminals: How Can Something That Feels So Good Be Wrong? Mich. Law Rev. 1990, 88, 1448–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.E.; Stuewig, J.B.; Tangney, J.P. The effect of stigma on criminal offenders’ functioning: A longitudinal mediational model. Deviant Behav. 2016, 37, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.E.; Phillips, S.; Kromash, R.; Siebert, S.; Roberts, W.; Peltier, M.; Smith, M.D.; Verplaetse, T.; Marotta, P.; Burke, C.; et al. The causes and consequences of stigma among individuals involved in the criminal legal system: A systematic review. Stigma Health 2024, 9, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B.; Levine, K. Redistributing justice. Columbia Law Rev. 2024, 124, 1531–1591. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, S.J. The twilight of welfare criminology: A reply to Judge Bazelon. South. Calif. Law Rev. 1975, 49, 1247–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, T.F.; Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; Lambert, N.M.; Fincham, F.D.; Brewer, L.E. Personal philosophy and personnel achievement: Belief in free will predicts better job performance. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2010, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, G.; Chandrashekar, S.P.; Wong, K.F.E. The freedom to excel: Belief in free will predicts better academic performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 90, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Huo, Y. Is free will belief a positive predictor of well-being? The evidence of the cross-lagged examination. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 193, 111617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Quinton, T.; Crescioni, A.W. Free to be Healthy? Free Will Beliefs are Positively Associated With Health Behavior. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 00332941241260264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, J.; Huo, Y. The value of believing in free will: A prediction on seeking and experiencing meaning in life. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2024, 16, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Forstmann, M.; Burgmer, P. Moralizing mental states: The role of trait self-control and control perceptions. Cognition 2021, 214, 104662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genschow, O.; Vehlow, B. Free to blame? Belief in free will is related to victim blaming. Conscious. Cogn. 2021, 88, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, A.J.; Bastian, B. Free WIll Belief Predicts Individual and Societal Punitiveness Across 44 Countries. Res. Sq. 2025; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, S.P. It’s in your control: Free will beliefs and attribution of blame to obese people and people with mental illness. Collabra Psychol. 2020, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rise, J.; Halkjelsvik, T. Conceptualizations of Addiction and Moral Responsibility. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.J.; Baumeister, R.F.; Ditto, P.H. Making punishment palatable: Belief in free will alleviates punitive distress. Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 51, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Hughes, V.; Mears, D.P. Prison personnel views of the effects of solitary confinement on the mental health of incarcerated persons. Crim. Justice Behav. 2025, 52, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schvey, N.A.; Puhl, R.M.; Levandoski, K.A.; Brownell, K.D. The influence of a defendant’s body weight on perceptions of guilt. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, I.I.D.E.; Wott, C.B.; Carels, R.A. The influence of plaintiff’s body weight on judgments of responsibility: The role of weight bias. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 8, e599–e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, A.W.; Siegel, Z.; Kist, C.; Mays, W.A.; Kharofa, R.; Siegel, R. Pediatric youth who have obesity have high rates of adult criminal behavior and low rates of homeownership. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121221127884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.W.; Goldstein, R.; Mason, E.E.; Bell, S.E.; Blum, N. Depression and other mental disorders in the relatives of morbidly obese patients. J. Affect. Disord. 1992, 25, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, G.; Pine, D.S.; Gamma, A.; Milos, G.; Ajdacic, V.; Eich, D.; Rössler, W.; Angst, J. The associations between psychopathology and being overweight: A 20-year prospective study. Psychol. Med. 2004, 34, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, D.S.; Cohen, P.; Brook, J.; Coplan, J.D. Psychiatric symptoms in adolescence as predictors of obesity in early adulthood: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, A.F.; Greene, J.D.; Karremans, J.C.; Luguri, J.B.; Clark, C.J.; Schooler, J.W.; Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D. Free will and punishment: A mechanistic view of human nature reduces retribution. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaidou, M.A.; Berryessa, C.M. A jury of scientists: Formal education in biobehavioral sciences reduces the odds of punitive criminal sentencing. Behav. Sci. Law 2022, 40, 787–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikani, M.; Rafiee, P. Why we derogate victims and demonize perpetrators: The influence of just-world beliefs and the characteristics of victims and perpetrators. Soc. Justice Res. 2023, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.R.; Shi, L.; Hickert, A. Stigmatizing ‘evildoers’: How beliefs about evil and public stigma explain criminal justice policy preferences. Psychol. Crime Law 2024, 31, 1366–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, B. What Medicine Can Do for Law. Bull. N Y Acad. Med. 1929, 5, 581–607. [Google Scholar]

- Cologna, V.; Mede, N.G.; Berger, S.; Besley, J.; Brick, C.; Joubert, M.; Maibach, E.W.; Mihelj, S.; Oreskes, N.; Schäfer, M.S.; et al. Trust in scientists and their role in society across 68 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2025, 9, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.; Boaz, A. Transforming evidence for policy and practice: Creating space for new conversations. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnas, A.C.; LaPira, T.M.; Wang, D. Partisan disparities in the use of science in policy. Science 2025, 388, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, C. Shadow Forensics: Uncovering 911 Call Analysis. Univ. Wis. Leg. Stud. Res. Paper 2025, 1833, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Lorandos, D.; Blevins, M. Dunning-Kruger and the law: Lawyers’ overconfidence in their scientific abilities allows junk science to pervert justice. Champion 2025, 49, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Batastini, A.B.; Lester, M.E.; Thompson, R.A. Mental illness in the eyes of the law: Examining perceptions of stigma among judges and attorneys. Psychol. Crime Law 2018, 24, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaidou, M.A.; Berryessa, C.M.; Xie, S.S. A mixed-methods analysis of the influence of bio-behavioral scientific evidence on US judges’ reasoning and sentencing decision-making. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2025, 102, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S. Addressing potential bias: The imbalance of former prosecutors and former public defenders on the bench. J. Leg. Prof. 2019, 44, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Shayeb, T.Y. Behavioral Genetics & Criminal Culpability: Addressing the Problem of Free Will in the Context of the Modern American Justice System. Univ. Dist. Columbia Law Rev. 2016, 19, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, G.D. Neurolaw; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, A.C.; Mishra, P. The Promise of Neurolaw in Global Justice: An Interview with Dr. Pragya Mishra. Challenges 2025, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Tang, R.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhu, R.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gong, X.; Wang, F. Dissecting biological heterogeneity in major depressive disorder based on neuroimaging subtypes with multi-omics data. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Akaila, D.; Arjemandi, M.; Papineni, V.; Yaqub, M. MINDSETS: Multi-omics integration with neuroimaging for dementia subtyping and effective temporal study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Du, W.; Liang, Y.; Xu, P.; Ding, Q.; Chen, X.; Jia, S.; Wang, X. An integrated neuroimaging-omics approach for the gut-brain communication pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1211979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Rao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Kong, H.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, D.M.; et al. Multi-omics analyses of the gut microbiome, fecal metabolome, and multimodal brain MRI reveal the role of Alistipes and its related metabolites in major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 2025, 55, e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Coghill, D.; Sjölander, A.; Yao, H.; Zhang, L.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Brikell, I.; Lichtenstein, P.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Larsson, H.; et al. Increased Prescribing of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Medication and Real-World Outcomes Over Time. JAMA Psychiatry 2025, 82, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, P.; Halldner, L.; Zetterqvist, J.; Sjölander, A.; Serlachius, E.; Fazel, S.; Långström, N.; Larsson, H. Medication for attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2006–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, N.; Sjölander, A.; Nourredine, M.; Li, L.; Garcia-Argibay, M.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Brikell, I.; Lichtenstein, P.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; et al. ADHD drug treatment and risk of suicidal behaviours, substance misuse, accidental injuries, transport accidents, and criminality: Emulation of target trials. BMJ 2025, 390, e083658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J. Genetic contributions to antisocial personality and behavior: A meta-analytic review from an evolutionary perspective. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 150, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.H.; Waldman, I.D. Genetic and environmental influences on aggression. In Human Aggression and Violence: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences; Shaver, P.R., Mikulincer, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bruins, S.; van der Laan, C.M.; Bartels, M.; Dolan, C.V.; Boomsma, D. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Aggression Across the Lifespan: A Longitudinal Twin Study. arXiv 2024. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/jxmzs_v1 (accessed on 4 August 2025).