Money Matters: A Contemporary Review of Young Adults’ Financial Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Young adults: it is critical that this demographic group understand the importance of their financial behavior and attitude towards financial management. Any financial mistake made at any stage of their life could have long-term catastrophic financial consequences.

- Educational institutions: Incorporating financial education into the curricula at different stages of an individual’s life could enhance their knowledge of financial literacy and subsequently contribute to their financial decision-making and well-being.

- Employers: Finance-related training, in addition to the knowledge obtained from educational institutions, would immensely help working adults manage their finances more efficiently at this stage of their lives, as young adults would already have access to financial inclusions. Targeted financial wellness programs could help them cope with challenges and better equip them with financial management and long-term retirement planning.

- Finally, regulatory bodies could contribute immensely via policies that ensure other stakeholders effectively implement targeted interventions. This could narrow the financial literacy gaps and, more importantly, regulate the digitalization of financial literacy products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Method and Procedure

- The search was restricted to English-language documents

- The subject areas were limited to business and management, economics, psychology, and the social sciences.

- Only journal articles and early access were included.

2.2. Data Analysis Techniques

3. Results

3.1. Publication Trends

- First, increasing global concern about the extent of financial literacy and behavior of young adults and its significance on their financial planning, management, and financial security in later years.

- Second, young adults’ financial behavior is currently perceived to be influenced by emerging technologies (fintech) and social media influencers.

- Third, major economic disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) and a vulnerable and uncertain economic situation have increased the need for well-designed financial planning and debt management among young adults.

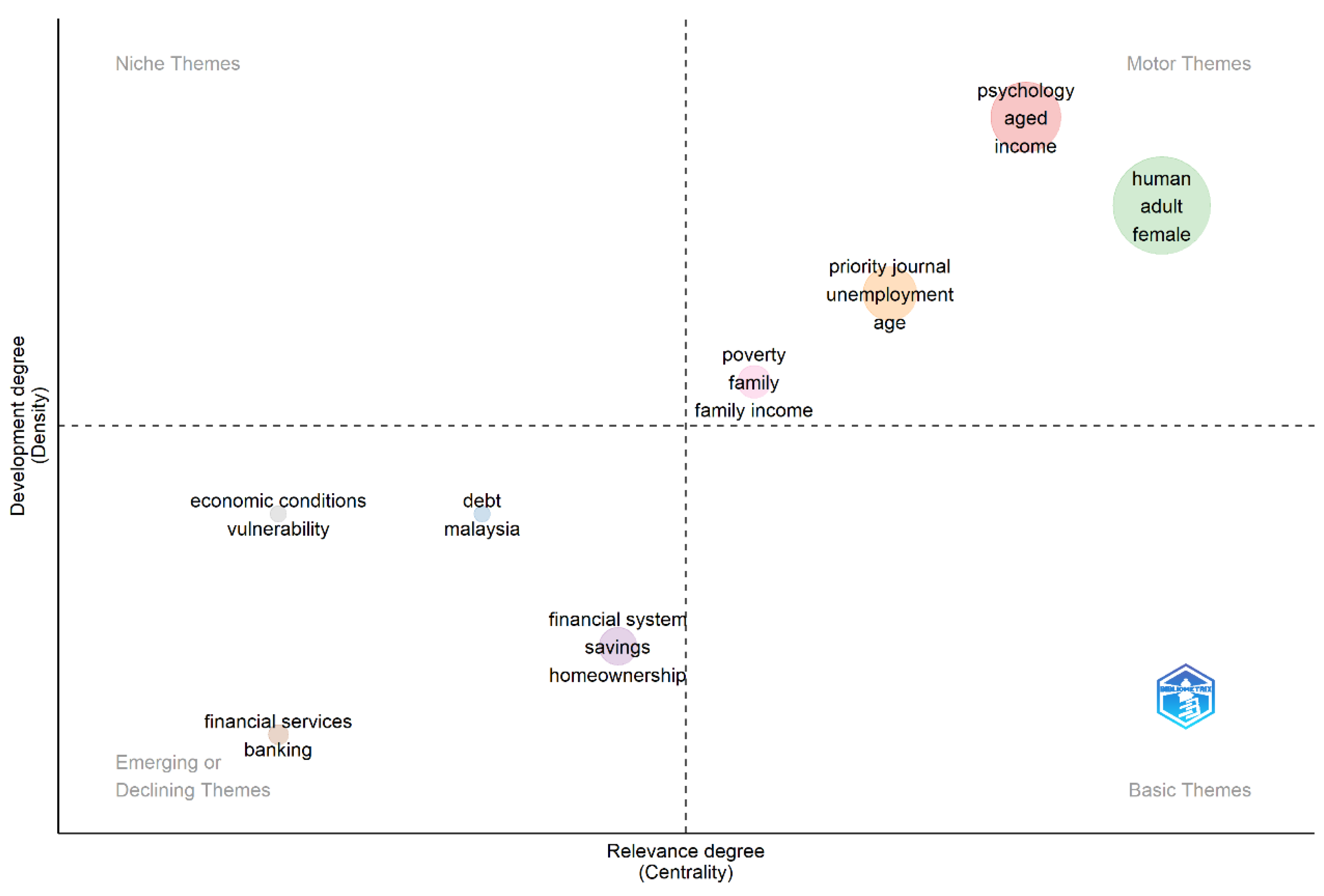

3.2. Thematic Map

3.2.1. Motor Themes (High Centrality and High Density)

3.2.2. Emerging or Declining Themes (Low Centrality and Low Density)

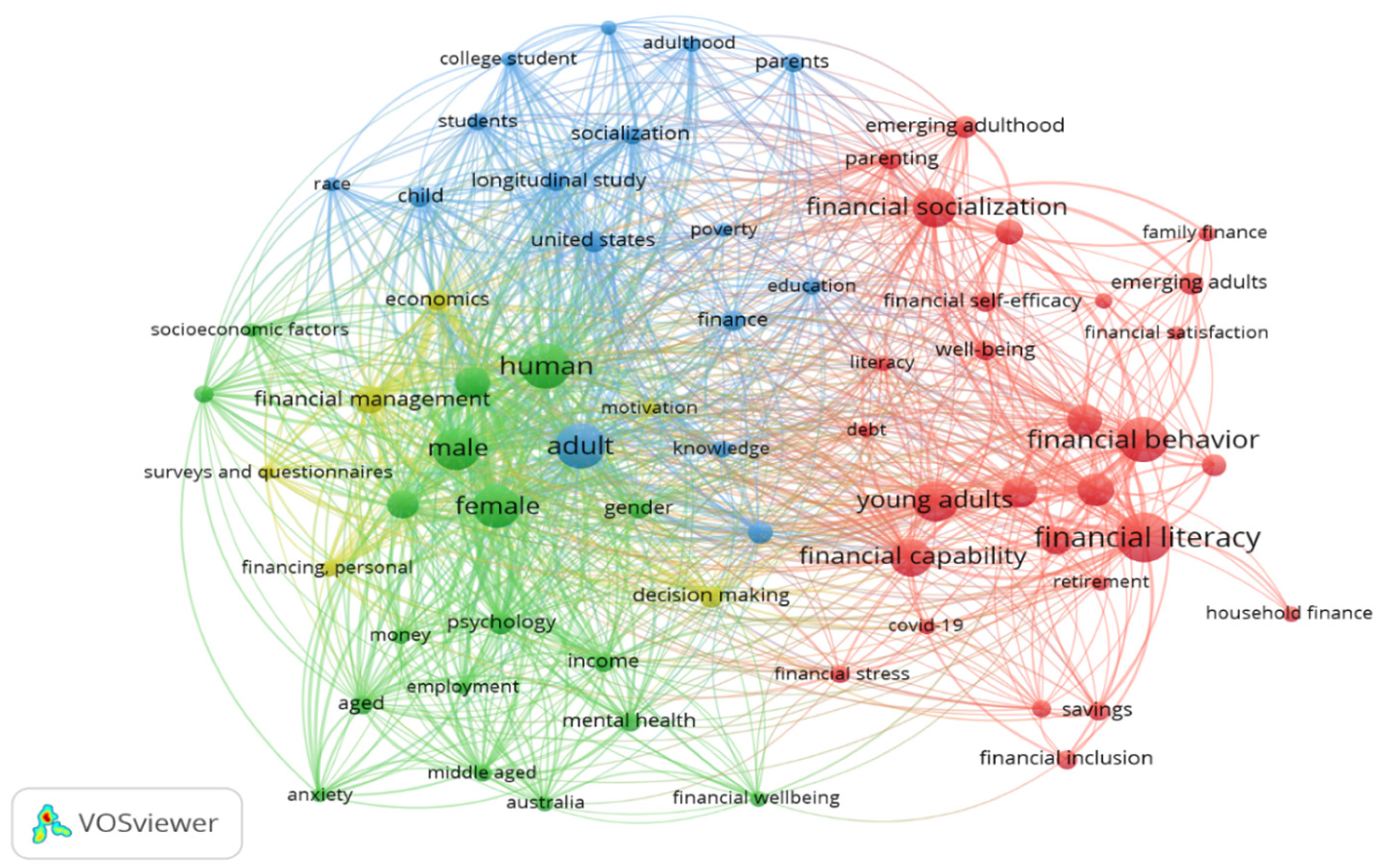

3.3. Keyword Analysis and Bibliographic Coupling

3.3.1. Red Cluster—Financial Literacy, Financial Capability, and Financial Behavior Among Young Adults

- Most studies are myopic and do not have a long-term focus on the financial behavior of young adults.

- Limited research on the combined effects of financial education with financial inclusion.

- Limited research on the impacts of digital financial literacy on young adults, including the effects on financial capabilities and emotional well-being, as digitalization has also increased the need for risk management in this context.

- Limited research on financial literacy and financial risk management among young adults, predominantly due to exposure to scammers.

- Studies should be undertaken over a longer time frame to witness the actual effects of financial literacy on young adults’ financial behavior and financial management.

- A multi-country study could examine the effects of integrating financial education with financial inclusion. A global study would be good, as access to financial inclusion is limited to several countries.

- Studies on the impacts of digital financial literacy and fintech on adults’ financial capabilities, financial behavior, and well-being.

- Explore the relationship between digital financial literacy and the possibilities of reducing financial scams among young adults.

3.3.2. Green Cluster—Psychosocial, Demographic (Gender), and Financial Behavior of Young Adults

- Limited longitudinal studies examining the psychosocial impact on young adults’ financial behavior.

- More constructs need to be explored to achieve a more holistic understanding of the psychological impact on young adults’ financial behavior.

- Most studies are conducted in silos. A more comprehensive study combining several aspects, such as financial education, demographics, psychology, and socio-economic factors, could give a broad picture of the realities of financial behavior and well-being.

- Limited study on gender influences on digital financial literacy, access to financial inclusion and ability to apply financial technology in the digital environment.

- A comprehensive longitudinal study across regions examining the impacts of psychology on young adults’ financial behavior could also capture the cultural effect in this context.

- Factors such as perfectionism and how it intensifies and suppresses financial stress and ultimately impacts financial behavior could be further examined.

- To assess real-world efficacy, implement and evaluate integrated interventions, blending financial literacy with financial inclusion.

- Gender-focused studies probing digital literacy disparities, engagement in financial technology, disparity in technological confidence and their ability to apply financial knowledge in digital environment.

3.3.3. Blue Cluster: Socialization and Financial Behavior of Young Adults

- Lack of studies examining the impact of non-family role models (mentors, community groups, influencers online) on young adults’ financial behavior.

- There is a limited understanding of when peer and social media influences on financial matters outdo family influence as individuals transition into adulthood. Are there any mediating roles in this regard?

- Studies are also scarce on how online socialization channels, such as social media platforms and FinTech applications, interact with traditional family-based financial teachings to shape financial attitudes and behaviors of young adults.

- Longitudinal study on the impact of non-family role models on young adults’ financial behavior and potential mediating factors to this relationship.

- Further research can examine when and how peer and social media influences begin to outweigh parental guidance in shaping financial behavior, or whether they act as complements across different cultures and life stages.

- Role of personality traits as moderators or mediators in the relationship between socialization and financial behavior of young adults.

- Examine how life-stage transitions (admission into college or University, starting employment, or marriage) alter the influence of parental financial socialization on the financial behavior and decision-making of young adults.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiao, J.J.; O’Neill, B. Consumer financial education and financial capability. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, K.H.K. Understanding Financial Planning Behavior: Insights from Theory of Planned Behavior for Financial Planning. Ph.D. Thesis, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, H.M.; Chen, B.H.; Chen, M.H.; Wang, C.H.; Wang, L.F. A study of the financial behavior based on the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2022, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.F.; Sabri, M.F.; Magli, A.S.; Abd Rahim, H.; Mokhtar, N.; Othman, M.A. The effects of financial literacy, self-efficacy and self-coping on financial behavior of emerging adults. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 905–915. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Kim, J. Factors associated with financial independence of young adults. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambuehl, S.; Bernheim, B.D.; Ersoy, F.; Harris, D. Peer Advice on Financial Decisions: A case of the blind leading the blind? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2025, 107, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, S.; Sotardi, V.A. Family Financial Socialisation and its Impact on Financial Confidence, Intentions, and Behaviors among New Zealand Adolescents. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2025, 46, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, S.; Sotardi, V. The impact of pocket money and term-time employment on the financial confidence of adolescents in New Zealand. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2025, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, H.; Singh, M. Examining the Role of Family in Shaping Financial Behavior: A Higher-Order Moderated-Mediation Approach. SCMS J. Indian Manag. 2024, 21, 70–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dhungana, M.; Shrestha, N. Financial Foundations: Role of Family Financial Socialization and Literacy in Enhancing Financial Well-Being of Gen Z. J. Emerg. Manag. Stud. 2025, 3, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, A. The interplay of parental financial behavior and financial literacy and the moderating effects of parental income. Glob. Bus. Financ. Rev. (GBFR) 2023, 28, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnewe, E.; Nicholson, G. Healthy financial habits in young adults: An exploratory study of the relationship between subjective financial literacy, engagement with finances, and financial decision-making. J. Consum. Aff. 2023, 57, 564–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zokaityte, A. Financial Literacy Education: Edu-Regulating Our Saving and Spending Habits; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Am. Econ. J. J. Econ. Lit. 2014, 52, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekarlaras, A.F.A.; Siregar, H.; Hasanah, N. Effects of Financial Literacy and Self-Efficacy On Risky Credit Behavior of Gen-Z. J. Apl. Bisnis Dan Manaj. 2025, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senduk, F.F.W.; Djatmika, E.T.; Wahyono, H.; Churiyah, M.; Mahasneh, O.; Arjanto, P. Fostering financially savvy generations: The intersection of financial education, digital financial misconception and parental wellbeing. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 9, p. 1460374. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, V.I. How do demographic and socioeconomic factors affect financial literacy and its variables? Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2077640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, P.; Anderson, M.; McRae, C.; Ramsay, I. The financial literacy of young people: Socio-economic status, language background, and the rural-urban chasm. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 2016, 26, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, A.; Messy, F.A. Measuring Financial Literacy: Results of the OECD/International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study. 2012. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2012/03/measuring-financial-literacy_g17a210b/5k9csfs90fr4-en.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Kardash, N.; Coleman-Tempel, L.E.; Ecker-Lyster, M.E. The role of parental education in financial socialization of children. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2023, 44, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Lim, H.; Lee, J.M. Young adults’ financial advice-seeking behavior: The roles of parental financial socialization. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 1226–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmunson, C.G.; Danes, S.M. Family financial socialization: Theory and critical review. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2011, 32, 644–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Bhatia, S.; Singh, S. Parental influence, financial literacy and investment behavior of young adults. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2022, 14, 520–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.; Barber, B.L.; Card, N.A.; Xiao, J.J.; Serido, J. Financial socialization of first-year college students: The roles of parents, work, and education. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Torquati, J. Are you close with your parents? The mediation effects of parent–child closeness on young adults’ financial socialization through young adults’ self-reported responsibility. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, A.B.; Kelley, H.H. Financial socialization: A decade in review. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42 (Suppl. S1), 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cude, B.; Lawrence, F.; Lyons, A.; Metzger, K.; LeJeune, E.; Marks, L.; Machtmes, K. College students and financial literacy: What they know and what we need to learn. Proc. East. Fam. Econ. Resour. Manag. Assoc. 2006, 102, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, M.B.; Parente, D.H.; Mansfield, P.M. Information learned from socialization agents: Its relationship to credit card use. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2005, 33, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, C.R.; Phillips, M.; Smalls, T.; Young, J. Investment behavior: Factors that impact African American women’s investment behavior. Rev. Black Political Econ. 2021, 48, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, R.S.; Ninova, E.; Silvers, J.A. With a little help from my friends: Selective social potentiation of emotion regulation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2021, 150, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Argyle, M. The Psychology of Money; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sundarasen, S.; Kumar, R.; Tanaraj, K.; Ali Alsmady, A.; Rajagopalan, U. From board diversity to disclosure: A comprehensive review on board dynamics and ESG reporting. Res. Glob. 2024, 9, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.K.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N. A bibliometric analysis of managerial finance: A retrospective. Manag. Financ. 2020, 46, 1495–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H.; Zeeshan, H.M.; Ahmad, F.; Bukhari, S.N.A.; Anwar, N.; Alanazi, A.; Sadiq, A.; Junaid, K.; Atif, M.; Abosalif, K.O.A.; et al. Bibliometric analysis of publications on the omicron variant from 2020 to 2022 in the Scopus database using R and VOSviewer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellili, N.O.D. Impact of corporate governance on environmental, social, and governance disclosure: Any difference between financial and non-financial companies? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Tripathi, P.S. Mapping the environmental, social and governance literature: A bibliometric and content analysis. J. Strategy Manag. 2023, 16, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, S.F.; Abdullah, D.F.; Elamer, A.; Yahaya, I.S.; Owusu, A. Global trends in board diversity research: A bibliometric view. Meditari Account. Res. 2023, 31, 441–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.; Rajagopalan, U.; Kanapathy, M.; Kamaludin, K. Women’s financial literacy: A bibliometric study on current research and future directions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Y.; Arwab, M.; Subhan, M.; Alam, M.S.; Hashmi, N.I.; Hisam, M.W.; Zameer, M.N. Modeling socio-economic consequences of COVID-19: An evidence from bibliometric analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 941187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ali, I.; Ashraf, R. A bibliometric review of the special issues of Psychology & Marketing: 1984–2020. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1144–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M.; Collins, J.M.; Odders-White, E. Experimental evidence on the effects of financial education on elementary school students’ knowledge, behavior, and attitudes. J. Consum. Aff. 2015, 49, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgood, S.; Walstad, W.B. The effects of perceived and actual financial literacy on financial behaviors. Econ. Inq. 2016, 54, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedline, T.; West, S. Financial education is not enough: Millennials may need financial capability to demonstrate healthier financial behaviors. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2016, 37, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass-Hanna, J.; Lyons, A.C.; Liu, F. Building financial resilience through financial and digital literacy in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2022, 51, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, T.; Ahmed, A.; Skagerlund, K.; Strömbäck, C.; Västfjäll, D.; Tinghög, G. Competence, confidence, and gender: The role of objective and subjective financial knowledge in household finance. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2020, 41, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zia, B. Financial Literacy Around the World: An Overview of the Evidence with Practical Suggestions for the Way Forward. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (6107). 2012. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/264001468340889422 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Munyegera, G.K.; Matsumoto, T. ICT for financial access: Mobile money and the financial behavior of rural households in Uganda. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2018, 22, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M.; Collins, M.; O’Rourke, C.; Elizabeth, O. Experiential Financial Literacy: A Field Study of My Classroom Economy. Working Paper. 2017. Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2018/preliminary/paper/NtBTnT6H (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Ahmed, Z.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Noreen, U. Two sides of a coin: Effects of perceived and actual financial literacy on investment decision making behavior mediated by financial risk tolerance. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Totenhagen, C.J.; Wilmarth, M.J.; Serido, J.; Curran, M.A.; Shim, S. Pathways from financial knowledge to relationship satisfaction: The roles of financial behaviors, perceived shared financial values with the romantic partner, and debt. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2019, 40, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthy, S.L.; Jonkman, J.; Blinn-Pike, L. Sensation-seeking, risk-taking, and problematic financial behaviors of college students. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2010, 31, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, A.; Aaltonen, M.; Rantala, K. Social determinants of debt problems in a Nordic welfare state: A Finnish register-based study. J. Consum. Policy 2015, 38, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, Y.J. Living beyond one’s means: Evidence from Malaysia. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2016, 43, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szendrey, J.; Fiala, L. “I Think I Can Get Ahead!” Perceived Economic Mobility, Income, and Financial Behaviors of Young Adults. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2018, 29, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Cai, J. Risk measures based on behavioral economics theory. Financ. Stoch. 2018, 22, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzahid, E.; Elouaourti, Z. Financial inclusion, mobile banking, informal finance and financial exclusion: Micro-level evidence from Morocco. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2021, 48, 1060–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peetz, J.; Wilson, A.E.; Strahan, E.J. So far away: The role of subjective temporal distance to future goals in motivation and behavior. Soc. Cogn. 2009, 27, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, J.P.; Xiao, J.J. The financial management behavior scale: Development and validation. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2011, 22, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, B.L.; Savla, J. Financial literacy of young adults: The importance of parental socialization. Fam. Relat. 2010, 59, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowa, G.A.; Despard, M.R. The influence of parental financial socialization on youth’s financial behavior: Evidence from Ghana. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2014, 35, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, A.; Kouwenberg, R.; Menkhoff, L. Childhood roots of financial literacy. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 51, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.A.; Parrott, E.; Ahn, S.Y.; Serido, J.; Shim, S. Young adults’ life outcomes and well-being: Perceived financial socialization from parents, the romantic partner, and young adults’ own financial behaviors. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2018, 39, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.L.; Rappleyea, D.L.; Schweichler, J.T.; Fang, X.; Moran, M.E. The financial behavior of emerging adults: A family financial socialization approach. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2017, 38, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosylis, R.; Erentaitė, R. Linking family financial socialization with its proximal and distal outcomes: Which socialization dimensions matter most for emerging adults’ financial identity, financial behaviors, and financial anxiety? Emerg. Adulthood 2020, 8, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, D. Antecedents to responsible financial management behavior among young adults: Moderating role of financial risk tolerance. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1177–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, R. Willful: How We Choose What We Do; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Serido, J.; Shim, S.; Tang, C. A developmental model of financial capability: A framework for promoting a successful transition to adulthood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2013, 37, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Baker, A. Self-esteem, financial knowledge and financial behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016, 54, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clusters | Keywords | Related Articles |

|---|---|---|

| RED Financial literacy, financial capability, and financial behavior among young adults | Financial behavior; financial literacy; financial capability; financial education; financial knowledge; young adults; financial satisfaction; financial attitude; family finance; emerging adulthood, parenting; financial socialization; financial self-efficacy; well-being; debt; financial stress, retirement; household; financial inclusion; COVID-19; savings; financial stress; household finance; savings; young adults | [47,48,49,50,52,53,68,75] |

| GREEN Psychosocial, Demographic (gender) and Financial Behavior of young adults | Adolescent; Human; female; male; gender; psychology; money; employment; income; mental health; financial well-being; middle-aged; Australia; anxiety; aged; decision-making; Economics; financial management; knowledge; mental health; young adults | [7,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,66,67,69,71] |

| BLUE Socialization and Financial Behavior of young adults | Adult; knowledge; finance; education; poverty; united states; longitudinal studies; child; race; socialization; college students; adulthood; parents; knowledge; socialization | [26,52,64,65,67,69,70,72,73] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sundarasen, S.; Rajagopalan, U.; Ibrahim, I. Money Matters: A Contemporary Review of Young Adults’ Financial Behavior. Societies 2025, 15, 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110304

Sundarasen S, Rajagopalan U, Ibrahim I. Money Matters: A Contemporary Review of Young Adults’ Financial Behavior. Societies. 2025; 15(11):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110304

Chicago/Turabian StyleSundarasen, Sheela, Usha Rajagopalan, and Izani Ibrahim. 2025. "Money Matters: A Contemporary Review of Young Adults’ Financial Behavior" Societies 15, no. 11: 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110304

APA StyleSundarasen, S., Rajagopalan, U., & Ibrahim, I. (2025). Money Matters: A Contemporary Review of Young Adults’ Financial Behavior. Societies, 15(11), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15110304