Abstract

In the modern dialogue of urban planning, social sustainability emerges as a crucial focus, especially in swiftly expanding cities like Hyderabad, Pakistan. Despite its importance, social sustainability is frequently overlooked, particularly in developing regions. This research examines the planning frameworks shaping socially sustainable residential areas in Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad City. Once lush farmland, Qasimabad has swiftly transformed into residential sectors. This transition has led to declining living standards and weakened social sustainability metrics. Through meticulous analysis, this study evaluates the community engagement, inclusivity and accessibility, social cohesion and safety, and facilities and amenities factors of social sustainability in the residential neighborhoods of Qasimabad Taluka using field visits and a comprehensive questionnaire survey with a sample size of 307 adopting cluster and quota sampling techniques. Data analysis with SPSS-22, supported by reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and Yeh’s satisfaction index model reveals key elements such as community accessibility, safety, green spaces, and aesthetic appeal. The findings reveal deteriorating infrastructure in Qasimabad, emphasizing the necessity for substantial interventions in infrastructure development, public space revitalization, and the cultivation of civic consciousness. Addressing these issues is vital for fostering neighborhoods that are both livable and socially cohesive. By shedding light on these critical needs, urban planners can effectively create sustainable living environments in Qasimabad Taluka.

1. Introduction

In today’s rapidly urbanizing world, developing socially sustainable residential neighborhoods has become a critical concern for cities and societies worldwide. These neighborhoods not only provide housing for residents but also foster a sense of community, promote social interaction, and enhance the overall well-being of their inhabitants. In urban planning and architecture, the idea of social sustainability is becoming more and more significant. Ensuring that the planning and design address the social demands of the residential neighborhood community is crucial. Sustainable planning approaches that emerge heavily incorporate the concept of social sustainability. Clarence A. Perry was the first to propose the idea of a residential neighborhood [1]. In essence, it is a residential concept that can include the population intake and the necessary facilities, including residential units, schools, and places of worship [2]. However, the primary thoroughfares that delineated the community were utilized for commercial objectives solely when required [3]. However, some contend that planning processes, particularly in developing [4] nations like Pakistan, frequently overlook social equality. Hyderabad City in Pakistan appears to be a long way from social sustainability and has an apparent problem meeting the requirements of its people to achieve social justice due to the city’s significant urbanization [5].

According to researchers [6,7,8], social sustainability refers to meeting fundamental human needs and ensuring that these requirements are met for future generations. Therefore, the definition of the social sustainability idea centers around the concept of “human” [4,8]. In light of this, social sustainability is an urban development process that is backed by institutions and policies that promote social cohesion and foster social integration and better living circumstances for all societal groups [8,9]. Researchers are increasingly viewing the social sustainability concept from an urban design viewpoint and identifying significant factors that contribute to this concept because of the concept’s vast implications in built-environment disciplines [4,10,11]. Those studies have mostly focused on the physical aspect of the urban design perspective [12]. The phrase “sustainable development” was initially coined in the 1972 book Limits to Growth, and it gained popularity in the early 1990s, when it was applied to advancements in urban planning and building design. However, modern urban development has a long history of sustainability issues in contemporary urban development [13]. One of the primary features of sustainable neighborhoods is that their population density should be limited in terms of the services and amenities that the neighborhood may provide. A strong foundation for governance can address public needs and encourage community involvement, civic engagement, a sense of belonging, and openness in local institutions. Developing homes with all the required amenities, such as parks, schools, drainage systems, and nearby Medicare facilities, can enhance social sustainability [14].

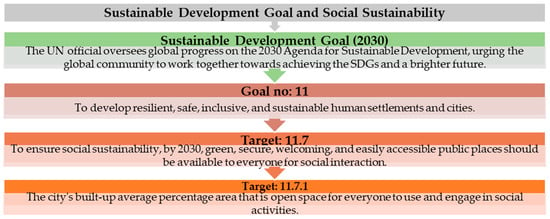

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been outlined by UN-Habitat, with goal 11 being “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable”, which focuses on improving cities [15]. This study is based on goal No. 11 and target 11.7 of the SDGs of UN-Habitat. Figure 1 shows SDG goal 11 and its target, focusing on social sustainability.

Figure 1.

Sustainable Development Goals and social sustainability [15].

To promote and increase sustainability, the United Nations established and funded the Human Settlement Center in 1978 [16]. Since residential areas are thought to be one of the answers to urban social problems and may offer a remedy for urban shortcomings, it was one of the most persuasive concepts in the minds of both theorists and practitioners. Prioritizing social sustainability, people’s health, and safety—especially that of vulnerable populations—is crucial. By creating a sense of safety, these programs can boost people’s self-esteem and sense of community. By ensuring that the neighborhoods continue to be vibrant centers of human interaction, connection, and support for future generations, we are investing in social sustainability and safeguarding the neighborhood’s future.

Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 11 (SDG 11) on sustainable cities and communities and the growth of residential neighborhoods depends on the idea of social sustainability. Social sustainability involves fostering good community relations, enhancing well-being, and ensuring safety and security [17,18]. Factors such as social equity, community stability, and pride contribute to social sustainability in neighborhoods, impacting residents’ quality of life [19]. Incorporating social sustainability principles into neighborhood design can lead to positive outcomes, emphasizing the importance of social aspects in creating consistent and livable communities [2].

Therefore, essentially, it is a residential neighborhood model that can include the appropriate amenities, including residential units, schools, places of worship, and inhabitants, while the major thoroughfares that surround the neighborhood are only sometimes utilized for commercial purposes [3,20]. For several reasons, responsible community planning techniques are essential in developing nations. First, these nations’ rapid urbanization and population increases frequently result in the emergence of informal settlements, which often have subpar standards of living and lack essential infrastructure and services [21]. Second, social sustainability can support equity and social inclusion, which are necessary for creating resilient communities. It is crucial to overall sustainable development [22]. Thirdly, social sustainability can support social capital and community cohesion, reducing the detrimental consequences of inequality and poverty [23]. Contemporary neighborhoods are becoming increasingly fragmented due to a rise in obstacles, which may cause various issues [24,25]. This can lead to different problems, including (a) a decline in the complexity of the urban fabric, (b) deficits in functionality, and (c) hazards to the ecosystem. These barriers, which fall into several categories, can lead to a range of conflicts in the city; finally, by putting residents near the natural world, socially responsible functional spaces can support a healthy atmosphere. Pakistan is seeing a fast increase in cities, often without planning. Nevertheless, cities cannot become inventive, beautiful, well-planned, or efficiently run independently [26].

Three equally significant pillars or components of sustainability are social, economic, and environmental, and they must be balanced [4,11,27,28]. The social component of sustainability is the least studied of the three pillars mentioned [29] and was only given significant attention as a crucial component of sustainability that warrants separate discussion after the year 2000 [30,31]. According to Colantino, A. [32], social issues were just included in the sustainability agenda in the late 1990s, while environmental and economic pillars have dominated sustainability discussions since the agenda’s inception [33]. The same situation was in Pakistan.

Issues related to socially sustainable neighborhood development have received less attention in Pakistan in past years [34]. Long- and short-term planning measures must be implemented to reduce the social and economic divide between neighborhoods. In Pakistan, neighborhood social sustainability is a crucial first step toward sustainable development and social cohesiveness in the metropolis [35]. Regarding social sustainability, neighborhoods differ significantly; the most significant degree of sustainability correlates with education. There is a noticeable distinction between unsustainable and sustainable neighborhoods regarding access to recreational amenities. A lack of basic civic amenities, unplanned and unregulated urban expansion, weak institutions, and a lack of enforcement of policies are significant obstacles to implementing socially sustainable neighborhood planning concepts in Pakistani residential areas [36].

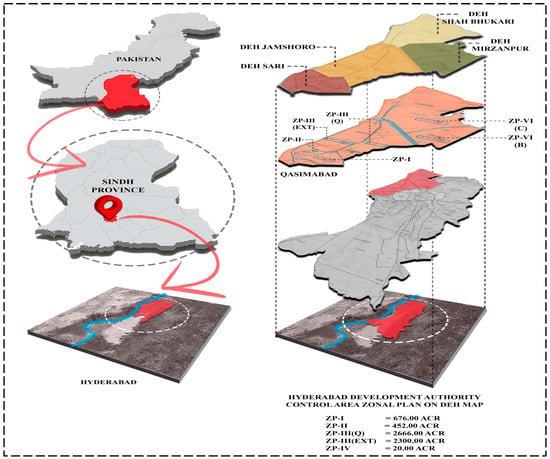

Hyderabad City is comprised of three sub-regions (locally termed as Talukas). The study has selected Qasimabad Taluka as the case study area because it is rapidly urbanizing due to rural–urban migration and urban sprawl. The Qasimabad Taluka is distributed into four dehs, i.e., Deh Sari, Deh Jamshoro, Deh Shah Bukhari, and Deh Mirzapuri. In the context of Qasimabad Taluka in Hyderabad City, this research article aims to investigate the planning practices employed to develop socially sustainable residential neighborhoods.

This research article investigates the planning practices for creating socially sustainable residential neighborhoods in Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad City, Pakistan. The study examines the challenges and limitations faced in achieving social sustainability in residential neighborhoods in this particular area. Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro of Qasimabad Taluka were selected as case study areas. The reason behind the selection of these two dehs was that different housing schemes/residential neighborhoods were initiated in both dehs from 1980–2010; therefore, the study was able to investigate whether the planning practices applied in the neighborhoods of both dehs were able to adopt social sustainability or not.

This study is the first type of research to investigate socially sustainable neighborhood planning parameters in Pakistan, aiming to empathize citizens’ concerns and provide solutions for their well-being. Therefore, this study seeks to analyze the challenges and limitations faced in achieving social sustainability in residential neighborhoods in this particular area. The study has covered community engagement, inclusivity and accessibility, social cohesion and safety, and facilities and amenities factors of social sustainability. These neighborhoods can play a significant role in fostering community cohesion, promoting social interaction, and enhancing residents’ overall quality of life. However, with the negligence of social sustainability factors, these neighborhoods are lacking in these aspects.

The findings and suggestions of this study can be beneficial not only for the other talukas of Hyderabad City for the design of residential neighborhoods. The findings of this research will also help the planners and policymakers of Pakistan and other countries and nations, where social sustainability is still an emerging idea. Those nations can incorporate social sustainability factors in the residential design guidelines of their policy documents.

Five sections make up the remainder of the paper. A review of the literature is given in the first section. The methods used for this investigation are described in the second section. The study’s findings are covered in the third section using exploratory factor analysis using SPSS-22. The analysis’s findings are completed in the fourth section of this article, and a discussion and conclusions are presented in the fifth section.

2. Literature Review

The ethos of sustainable development emerged due to growing urban populations and the demand for physical development to satisfy any city or neighborhood’s social and economic needs [37]. Recent studies on social sustainability have looked more closely at this complexity and how it interacts with other planners’ triangle components. Researchers stress the importance of understanding how popular conceptions of “the good life” can facilitate and obstruct efforts to promote sustainable development [38]. Bramley [39], who examines the efforts to build a more compact city to attain sustainability, proposes a social sustainability framework. To try to provide an accessible way of life for everyone, social sustainability is, on the one hand, primarily concerned with distributive justice or social equality. Sustainability is a constant vision and process rather than a final product, as it introduces new lifestyles and values to every part of the world through sustainable development [40,41].

There have been various studies on socially sustainable neighborhood planning in developing countries, focusing on different aspects such as evaluation frameworks, comparison of concepts, and case studies. Here are some highlights from recent research.

Evaluating Social Sustainability in Jordanian Residential Neighborhoods: The study developed a framework for rating social sustainability in neighborhoods, utilizing a quantitative approach that combines the AHP techniques and case studies. This research mainly focuses on the Jordanian context and aims to understand the context’s influence on social sustainability assessment [42]

Sustainable Neighborhoods in Brazil: This research compared three Brazilian neighborhoods planned as sustainable urban units, analyzing them against common principles of urban sustainability like local interaction, mobility, mixed use, natural resources and innovation, and socio-economic participation. The study suggests sustainable neighborhoods could encourage sustainable development in Brazil by incorporating active public stakeholder participation [43]

Sustainable Urbanism in Developing Countries: A book that analyzes several planning and design criteria through case studies from India, Indonesia, China, etc., using advanced GIS techniques. It refers to urban planning as an effective measure to protect and promote the cultural characteristics of specific locations in these developing countries [44]. Then, some information about design philosophy can be attracted to the current neighborhood planning layout: What captured Perry’s attention was the dehumanizing effect of the neighborhood layout with no encouragement for social interaction. One of the most significant factors for sustainability-oriented planning is comprehending how the spatial configuration impacts social dynamics. The Garden City Concept (Howard Howard’s concept of the “Garden City”, which focused on green belts, attractive social amenities, and clustering functions) was central to his idea of New Town. Including these principles can be responsible for better sustainability for neighborhoods. There has been a significant global population shift in recent years, with many moving from rural to urban areas and between nations due to the rapid prosperity associated with the worldwide intensification of industrial and commercial zones [45,46,47]. Within cities, neighborhoods are always firmly grounded in reality, possessing various physical, social, and cultural attributes [48]. Through their substantial development contributions, the neighborhood becomes an essential city unit, which is the goal of sustainable urban development. One of the most critical features of city expansion is the popularity of more sustainable cities in recent years. The concept of sustainable cities was created to help with and handle issues related to people’s higher living standards [49,50].

2.1. Purpose of Sustainable Cities

The Italian architect Giancarlo di Carlo once said, “Once we produced to consume, now we consume to produce” [51]. Through the course of the 20th century, the idea of sustainable development evolved as a response to the degradation of the urban environment. The 1972 United Nations Conference in Stockholm placed a high priority on topics related to urban administration and human settlement.

One of the main components for better urban growth is the pursuit of sustainable cities, which has increased in recent years. The concept of sustainable cities was created to help with and solve problems related to the higher living standards of the populace [49,52]. City planners, architects, and designers have taken notice of the neighborhood. Both academics and practitioners highly value the notion that neighborhoods can remedy urban shortcomings and resolve social problems in urban areas. Communities and structured local institutions can be used to characterize neighborhoods [53].

2.2. Sustainable Urban Development

Metro-level urban entities like “Central Business Districts (CBDs) [54]”, “Historic Districts”, neighborhoods, and urban public spaces as microscale built environments have all been included in the purview of urban social sustainability, which commences at the macro level at the region and city [28]. The extant literature served as the foundation for studies on the three distinct urban units (macro, medium, and micro scales). It has been determined that the social sustainability of micro-scale urban built environments, such as public urban spaces in cities, has received the least attention and still requires investigation. Nonetheless, approach-based studies are another category that covers social sustainability in an urban setting. The most often researched topics in urban concerns are housing and density, historic district urban renewal initiatives, urban form, urban rehabilitation, and issues related to urban regeneration and restoration. In the UK, urban regeneration strategies include an increasing number of social sustainability evaluation instruments, as noted by Glasson and Wood [55]. A different study [54], looks at the characteristics and elements that support social sustainability in the restoration of Shanghai, China’s historic neighborhoods. Ancell and Thompson-Fawcett [38] attempted, nevertheless, to create a model for the social sustainability of medium-density housing in Australia’s New Zealand. However, Pakseresht and Fazeli [56] address the necessity of a social sustainability-based strategy for creating regeneration plans in emerging and less developed nations in Tehran, Iran. In a different study [57], restoration solutions based on users’ visions are proposed for Naghsh-e-Jahan Square to achieve social sustainability.

2.3. Social Sustainability

Social sustainability in sustainable residential neighborhoods is crucial for enhancing community well-being and quality of life. Studies emphasize the significance of social aspects in neighborhood design [58], highlighting the positive impact of incorporating social sustainability principles in residential complexes [59]. Factors such as social equity, community stability, and safety play key roles in fostering social sustainability [60]. Research also indicates that neighborhood design criteria, including mixed land use and public spaces, significantly influence social sustainability [61]. Furthermore, the quality of life in residential communities is closely linked to residents’ behaviors and interactions with their urban environment, affecting social sustainability. Enhancing social interaction through urban form aspects like green spaces and mixed land use can significantly improve social life in residential neighborhoods.

Urban communities need more than just physical spaces to solve issues and create the required capacities for social sustainability. It is also essential to consider extra features like social structures and procedures. Public participation processes are unhelpful in achieving social sustainability because they are transitory and project-oriented, which hinders sustainable solutions and does not support the growth of local groups to handle dynamic social concerns.

2.4. Sustainable Neighborhood

Sustainable neighborhoods play a crucial role in enhancing the sustainability of residential environments. Various studies emphasize the importance of efficient spatial organization at the neighborhood unit level to achieve sustainability [62]. Evaluating neighborhoods based on sustainable criteria such as regional issues, compacted form, mixed land use, connectivity, and walkability is essential [63]. Urban sustainability is a key consideration in urban policies, aiming to protect the environment from deterioration due to economic growth and resource consumption [64,65]. Professionals are increasingly focusing on integrating sustainability into residential neighborhood planning to improve living conditions and address the negative impacts of rapid urbanization [66]. Contemporary strategies in architecture and planning are evolving to meet the demands of sustainable development, emphasizing environmental, economic, and social aspects of neighborhood design [67].

2.5. Sustainable Residential Neighborhood Characteristics

Sustainable residential neighborhoods exhibit key characteristics such as efficient spatial organization, green spaces, mixed land use, pedestrian-oriented design, and walkability [64]. These neighborhoods prioritize environmental preservation, social interaction, and reduced reliance on vehicles [68]. Implementing sustainable neighborhood criteria, like high population density and grid pattern planning, enhances walkability and sustainability [67]. The importance of sustainable neighborhood design lies in creating environments that balance residential needs with green spaces [69], promoting a human scale in land use regulation for a sustainable environment. Assessing urban sustainability in residential neighborhoods through systems like LEED-ND helps in understanding and improving environmental standards for future urban development. Innovative approaches to neighborhood planning and architecture are crucial to address challenges like resource depletion, climate change, economic constraints, and the need for walkable communities. Figure 2 below lists the qualities to be aware of when interacting in public engagement and social sustainability.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of social sustainability [34].

The traits mentioned above make it easier to assess social sustainability in light of the sustainable development pillar (i.e., social sustainability) [70]. However, the study has covered aspects such as community engagement, inclusivity and accessibility, facilities and amenities, and social cohesion and safety for social sustainability.

In conclusion, the literature review underscores the dynamic and transformative nature of sustainable development, which brings forth new lifestyles and values on a global scale. Social sustainability, a complex and integral component of this vision, is intricately interwoven with the other elements of the planners’ triangle. Frameworks such as Bramley’s [39] highlight the pivotal role of distributive justice and social equality, which are central to achieving social sustainability. Studies in developing countries, including research on Jordanian neighborhoods and sustainable urbanism in Brazil and India [43,71], underscore the significance of local context and the critical role of public participation. These studies emphasize the importance of designing neighborhoods that promote social interaction and inclusivity through thoughtful spatial configuration and social dynamics.

Our research on social sustainability in residential neighborhoods in Pakistan, particularly in Qasimabad Taluka, aligns with the principles set forth in Sustainable Development Goal 11, specifically Target 11.7 and Indicator 11.7.1 [15]. We concentrate on essential traits such as inclusivity and accessibility, social cohesion and cultural diversity, health and education, public spaces, social equity, and aesthetics. By addressing these facets, we aspire to contribute to the creation of livable, equitable, and resilient urban communities. This research advances the discourse on sustainable urban development and provides valuable insights for policymakers and urban planners, facilitating the development of more holistic and inclusive urban environments.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

Qasimabad Taluka in Hyderabad City has been selected as study area, due to its expanding population in comparison to other city talukas (sub-regions) of Hyderabad city. Hyderabad is a city for administration, business, and specialized medical and educational services. It is pretty significant historically as well. Geographically and historically, the city has consistently drawn migrants from surrounding towns and rural regions. Qasimabad has been observed as one of the locations with the most significant population inflow.

This study evaluates social sustainability in Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad, Pakistan; traits of social sustainability are examined by focusing on targets 11.7 and 11.7.1 of UN-Habitat [15]. The primary reason for choosing Qasimabad Taluka in Hyderabad is its increasing land values and few sanctioned facilities, as they widely detract from the sustainable living attributes. The evaluation of the built environment and how sustainability is integrally tied to it was made more accessible by the assessment of the international literature. Research and improvement was conducted on sustainable mixed approaches—an analytical and rigorous methodology for assessing evolution’s role in the emergence of social urban problems [71]. The study was conducted in the residential neighborhood of two dehs in Qasimabad Taluka, i.e., Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro. In general, analyzing current conditions for socially sustainable neighborhood planning practices aids in understanding the causes of deficiencies. It may help determine the current gap toward socially sustainable neighborhood planning.

Qasimabad Taluka began its development in 1979 [72,73] and was split into four deh neighborhood areas by the Hyderabad Development Authority. It consists of four dehs, which are named as follows: Deh Jamshoro, Deh Sari, Deh Shah Bukhari, and Deh Mirzapuri. Deh Sari began to develop in 1979, and development in Deh Jamshoro started in 1980 with an increase in population. Deh Shah Bukhari and Deh Mirzapuri, on the other hand, continue to be sparsely populated and are developing slowly. Figure 3 shows the study area map, indicating each deh division.

Figure 3.

The layout plan of Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad, Sindh, Pakistan.

Population increase is the most significant impediment to establishing a sustainable city in the regional context. The urban population of Hyderabad was expected to be 1,500,000 in the 2010 census, and it grew steadily over the years to reach an estimated 1,850,000 by 2020 [74]. Qasimabad Taluka, on the other hand, had a population of 11,534 in the 1998 census and gradually increased to 118,374 in the 2017 census [75], representing a 269% growth rate [76]. Furthermore, the most occupied dehs have been selected for the study to investigate the social sustainability in residential neighborhoods, i.e., Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro.

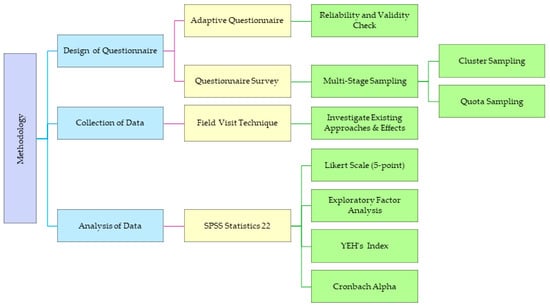

3.2. Methodology

To ensure the social sustainability of residential neighborhoods, the study employed a meticulous data collection process. This process involved a questionnaire survey and field visits, as suggested by Halim bin and Hasnita bin [77]. A comprehensive data collection process is imperative to determine whether a residential neighborhood is socially sustainable [77]. These methods give insights into the residents’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors related to social interaction and sustainable living. The research framework is represented in Figure 4, which is described below.

Figure 4.

Research methodology framework.

The research framework, illustrated in Figure 4, integrates questionnaire survey and field visit approaches to understand community dynamics comprehensively. To show the progressive relationship between socially sustainable neighborhoods and current residential neighborhood planning, the research is mainly restricted to analyzing social sustainability factors and characteristics for sustainable communities (i.e., by focusing on opportunities for community residents to engage, inclusivity and accessibility, facilities and amenities, and social cohesion and safety) and looking into current setups with the concept of socially sustainable residential neighborhood planning practices for the chosen case study, i.e., Qasimabad Taluka in Hyderabad City. This study investigates the relationship between social sustainability and the planning practices of the past 40 years (1980–2020) and how it influences inhabitants’ satisfaction levels [78].

This study utilized close-ended questions to delve into subjective experiences and the influence of sustainable practices on residents’ daily lives.

3.3. Data Collection

According to SDG Goal 11 (Target 11.7), a socially sustainable neighborhood has socially sustainable attributes. To attain the investigation, each sampled housing scheme was chosen to examine the subsequent characteristics of a socially sustainable neighborhood: safety, aesthetics, education, cultural diversity, social cohesion, health and well-being, accessibility, inclusion, and equity [17,19].

The data were collected by using the questionnaire survey and field visit techniques. This study utilized close-ended questions to delve into subjective experiences and the influence of sustainable practices on residents’ daily lives. The questionnaire survey data were collected using multi-stage sampling methods [79]. The data collection focuses on the indicators and characteristics to measure social sustainability, which comprises knowing the neighboring dwellers interact with others by prominent accessibility along safety measures, as well as opinions of people relating to convenience and the built form, as well as social spaces.

The adaptive questionnaire was designed with a focus on social sustainability characteristics, ensuring it covered important areas such as opportunities for community residents to engage, inclusivity and accessibility, facilities and amenities, and social cohesion and safety. By prioritizing opportunities for residents to engage, the survey gathered insights into how individuals connect with and participate in their local community, fostering engagement and a sense of belonging. Inclusivity and accessibility were also paramount, with questions aimed at understanding the diverse needs and experiences of all residents, ensuring no voice was overlooked. Additionally, the survey addressed facilities and amenities, examining the availability and quality of essential community resources such as parks, education, and healthcare. Social cohesion and safety were explored to assess residents’ relationships with one another and their perceptions of neighborhood safety. By focusing on these core aspects, the adaptive questionnaire provided a thorough evaluation of the community’s social sustainability, offering valuable data for future improvements and policies.

The field visit technique was also used for data collection. The primary aim of a field visit is to gather geographical details. Therefore, the sampled housing schemes were personally visited to investigate the actual condition, especially in terms of the community engagement, inclusivity and accessibility, facilities and amenities, and social cohesion and safety factors of social sustainability. The results of this investigation are discussed in Section 4.1.

3.4. Sample Size

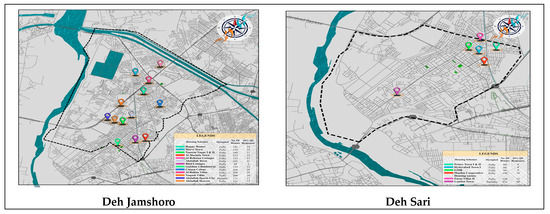

In 1979, Qasimabad Taluka in Hyderabad City began to develop. According to Sindh [80], the taluka’s land area is 6114 acres, where Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro have been occupied to the utmost. The residential areas initiated registering a major set of residential areas from 1979, mainly registered between the 80 s period in both dehs, whereas Deh Sari is fully occupied and comprised of 63 housing schemes to date and Deh Jamshoro has 123 registered residential schemes to date. This research was collected from the two groups (dehs) of Qasimabad Taluka, and therefore a combination of both probability and non-probability sampling were used. The housing schemes in Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro were developed during 1979–2010 by the Hyderabad Development Authority. Afterwards, the housing schemes were developed in the other dehs of Qasimabad Takuka. Therefore, firstly, the cluster sampling was used to choose the housing schemes developed in different decades from 1979–2010 (see Table 1). Most of the development in Qasimabad Taluka occurred in the 1980s, and therefore six housing schemes from Deh Jamshoro and five from Deh Sari were selected. The other housing schemes developed in the 1990, 2000, and 2010 decades were also selected; the details about these housing schemes and their development year are given in Table 1. The housing schemes were selected by concentrating on each decade of development up to this point, or 5–7% of every ten years of development [81]. The data for registered housing schemes have been collected [82]. The total number of registered housing schemes in Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad is 226. Then, on the housing scheme level, the quota sampling technique was adopted. It is a non-probability technique and the researchers chose this technique according to specific traits or qualities. The reason behind the selection of a cluster of housing schemes on a decade basis was to investigate the application of social sustainability in planning practices during the 1980–2010 phase in Qasimabad Taluka and also give equal chance to every development phase to avoid biasedness and maintain the validity and reliability of research.

Table 1.

Cluster sampling of housing schemes.

Selected Housing Schemes

Using the cluster sampling method, 13 housing schemes were selected from Deh Jamshoro and 6 from Deh Sari, as there are 123 housing schemes in Deh Jamshoro, and Deh Sari has 63 housing schemes. The following table shows the primary data of the selected housing scheme for further analysis (i.e., the study areas have been chosen by focusing on the decade and size of each housing scheme). Table 1 shows the cluster of housing schemes from each deh separately, along with the number of houses and number of responses taken by using the quota sampling method [81]; 307 responses have been gathered.

The selected clusters of the Deh Jamshoro and Deh Sari housing schemes are indicated in Figure 5 above. Investigated characteristics of socially sustainable development were examined in the chosen dwelling projects.

Figure 5.

Location indication (selected housing schemes).

3.5. Data Analysis

Yeh’s Index of Satisfaction was employed to assess residents’ nominal satisfaction with various sustainability aspects such as social cohesion, safety, cleanliness, and transportation options [83]. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 22 (SPSS-22) was the primary data analysis tool. To ensure the reliability and validity of the data, we applied Cronbach’s alpha to the sample size for each variable related to social sustainability. The reliability index was interpreted as follows:

- -

- Good: Alpha ≥ 0.6;

- -

- Better: Alpha between 0.7 and 0.8;

- -

- Excellent: Alpha ≥ 0.9 [84].

This research conducted an exploratory factor analysis to identify patterns within the data. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test was used to assess the adequacy of the sampling, with values between 0.8 and 1.0 indicating sufficient sampling [85]. KMO values were categorized as follows:

- -

- Mediocre: 0.6–0.69;

- -

- Medium: 0.7–0.79;

- -

- Insufficient: <0.6, necessitating corrective measures [86].

Qualitative Approach: The narrative from field visits complemented the quantitative findings, offering a richer, more nuanced understanding of the community.

Likert Scale: A 5-point Likert scale was incorporated into the survey to quantify respondents’ attitudes and feelings. Responses were numerically coded and analyzed statistically to uncover patterns and correlations. The responses have been numerically coded and subjected to statistical analysis to find patterns and correlations in the data. The next part discusses the results obtained through data collection and analysis.

4. Results

The results gathered through field visits, structured observation, descriptive analysis, Cronbach’s alpha, the Yeh Satisfaction Index model, and exploratory factor analysis are presented below.

4.1. Result of Field Visits

Field visits provided detailed insights into specific behaviors and patterns. Figure 6. depicts Qasimabad’s (i.e., Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro) unsustainable situation and the aesthetics of the city. Such inadequate local land use planning could lead to social discord [83] due to interactions between social groups and the extent to which individuals belong to a specific group or community [87]. Protecting the environment requires prioritizing sustainability for the present and future. Planners and decision-makers should focus on technologies that can rapidly restore the urban environment and provide vital solutions [49,88]. There is broad consensus regarding the significance of neighborhood planning in attaining social sustainability [67].

Figure 6.

Non-sustainable scenario of Qasimabad: city aesthetics.

In public spaces, health and well-being are connected to buildings and can be enhanced by aesthetics and views; none seem to satisfy. The social activity for community engagement, social cohesion, and social equity needs the public spaces to interact, which seems complicated to find at a neighboring level.

The decisive levels in Table 2 were meticulously determined through a comprehensive evaluation process, incorporating a blend of critical factors. These factors include the intrinsic importance of each characteristic in fostering social sustainability, the informed insights and judgments of experts in the field, and the tangible impact of these characteristics on enhancing community welfare.

Table 2.

Socially sustainable residential neighborhood characteristics.

Significant: Indicates a noteworthy impact on social sustainability but not necessarily critical.

Vital: Denotes essential characteristics that are crucial for the well-being and social sustainability of the community.

Pivotal: Represents key characteristics that have a substantial influence on the overall sustainability and functionality of the neighborhood.

Adjectives like ‘significant’, ‘vital’, and ‘pivotal’ were carefully selected and assigned corresponding grades to reflect their perceived importance and influence accurately. This nuanced approach ensures that each characteristic’s role in promoting a socially sustainable residential neighborhood is thoroughly understood and appropriately prioritized.

4.2. Results of Descriptive Analysis

Descriptive analysis is a method used to examine social sustainability in a community, focusing on factors like resident engagement, inclusivity, accessibility, facilities, and safety. It uses Cronbach’s alpha, a 5-point Likert scale, exploratory analysis, and a satisfaction index model to gather insights. The scale measures residents’ perceptions of opportunities for engagement, while Cronbach’s alpha ensures data consistency. The satisfaction index model helps identify areas for improvement and informs targeted interventions. This approach helps guide policymakers in improving residents’ experiences and quality of life.

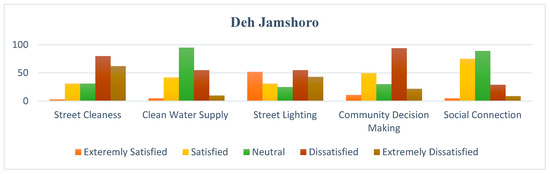

4.2.1. Opportunities for Community Residents to Engage

Residents of each deh were surveyed about their prospects for community engagement, and the feedback was predominantly unfavorable. This highlights a significant gap in essential opportunities for community interaction, which are crucial for timely and effective decision-making within the community. The absence of these engagement opportunities can delay decision-making processes and hinder the formation of strong social connections, which are vital for fostering a cohesive and supportive living environment. The survey responses underscored the importance of social connections in enhancing community welfare and making informed living decisions. However, the reliance on various infrastructural factors such as street cleaning, lighting, and clean water supply often diminishes these social connections. This dependency tends to lower the perceived importance and ranking of social ties, ultimately impeding collective community improvement. This dependency often results in a lower ranking of social ties, which hinders collective improvement. Figure 7 describes the responses received from inhabitants.

Figure 7.

Opportunities for communities to engage.

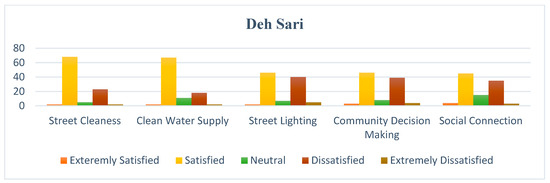

4.2.2. Inclusivity and Accessibility

The investigation into inclusivity and accessibility delves into the modes of movement within the studied areas. This includes assessing access to local transportation, as well as the ease of private vehicle movement. The analysis revealed that the infrastructure supporting these modes of transportation was subpar, with little attention given to amenities like cycling routes and pedestrian passages. Inclusivity and accessibility are crucial considerations in the development of any residential neighborhood as they impact the quality of life for residents. Figure 8 provides a visual representation of the accessibility statistics for each deh, shedding light on the current state of inclusivity and accessibility within these areas.

Figure 8.

Inclusivity and accessibility.

The responses collected at Deh Jamshoro and Deh Sari indicate appropriate accessibility for local and private vehicular movement but inadequate provision for pedestrians and no cycling routes for movement.

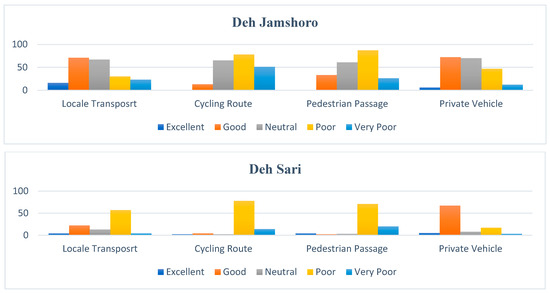

4.2.3. Facilities and Amenities

The list of items in Figure 9 represents various aspects related to facilities and amenities in residential neighborhoods, specifically focusing on Qasimabad Taluka in Hyderabad City, Pakistan. These items were selected based on their significance in contributing to the overall livability, sustainability, and quality of life in residential neighborhoods, aligning with the study’s focus on socially sustainable planning practices.

Figure 9.

Facilities and amenities.

The basic facilities and amenities are a priority for the development of any residential neighborhood. Figure 9 shows the statistics for facilities and amenities in residential neighborhoods for each deh.

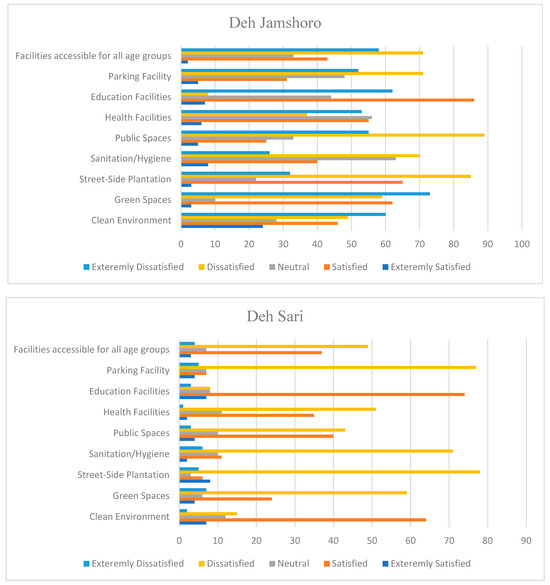

4.2.4. Social Cohesion and Safety

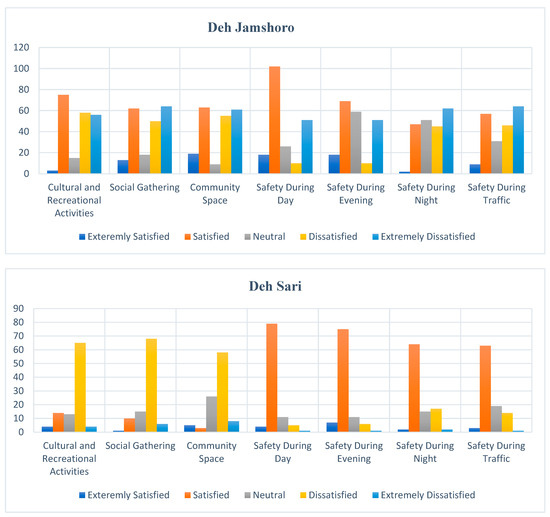

To investigate social cohesion, the survey analysis for each deh, shown in Figure 10, presents a dissatisfying level of social gathering, community spaces, and cultural and recreational spaces for inhabitants. The public parks and spaces are available but not maintained, so the inhabitants are losing interest. At the same time, the security is being supported by residents.

Figure 10.

Social cohesion and safety.

The above studies have shown that community satisfaction can be influenced by familiar places or public domains, including open spaces at various neighborhood and street levels, which facilitate inter-communal interaction [2,19]. The analysis indicates that open spaces at the precinct level play a significant role in fostering a sense of community. However, it is important to note that while the data reflect residents’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction with open spaces, they do not explicitly rank the importance of open spaces against other factors [32]. Therefore, while open spaces are crucial, the study does not definitively establish their relative importance compared to other characteristics in the context of community satisfaction and social interaction [78].

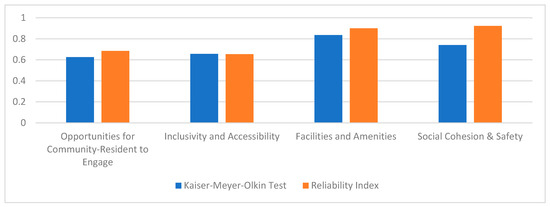

4.3. Cronbach’s Alpha and Exploratory Factor Analysis

To analyze the validity and reliability of sample size, Cronbach’s alpha and exploratory analysis have been applied. A range of 0.8 to 1.0 for the KMO test values indicates adequate sampling. KMO levels are medium (0.7–0.79) and mediocre (0.6–0.69). If the sampling is insufficient and corrective action is required, a KMO value of less than 0.6 indicates this [86]. The analysis ranges between 0.633 and 0856 and defines the KMO test sufficiently, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cronbach’s alpha and exploratory factor analysis.

For each variable selected for social sustainability, the reliability analysis index scale check was carried out, and the data and sample reliability index were examined using SPSS-22 for the frequencies of each variable. When the reliability index hits 0.6, it is deemed good; when it reaches 0.7–0.8, it is deemed better; and when it reaches 0.9, it is considered excellent [84]. The number of items as variables selected for each characteristic ranges from 0.623 to 0.887, defining the reliability index from good to excellent, as illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Exploratory factor analysis.

4.4. Yeh’s Satisfaction Index

One of the most critical indicators of pleasure, well-being, and quality of life has been identified as residential satisfaction as shown in Table 4. The analysis infrequently displayed the positive satisfaction index for the chosen variables. The overall satisfaction score for the socially sustainable residential neighborhood is −308.775%, indicating residents’ discontent with the lack of socially engaged places in Hyderabad’s Qasimabad Taluka, as indicated by the selection variable presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Yeh’s Satisfaction Index.

The characteristics selected to gauge the social sustainability of residential neighborhoods include opportunities for the community to engage, inclusivity and accessibility, facilities and amenities, and social cohesion and safety for the satisfaction index; the variables for the characteristics are identified as −12.703, −71.267, −209.12, and −15.685, respectively. A peaceful environment and the impact of growth are significant issues that must be addressed to improve the social sustainability of communities by encouraging a sense of fulfillment and ownership of the place. This positive social reaction can improve the neighborhood’s physical and functional aspects and increase its economic viability. On the other side, the residents’ satisfaction leads to adverse values.

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Characteristics of Socially Sustainable Neighborhoods

It is clear from the literature review that opportunities for the community to engage, inclusivity and accessibility, facilities and amenities, and social cohesion and safety are the important features of social sustainability. However, based on the provided results in Section 4, they are not meeting the desired levels in Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro of Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad. The further details include the following.

Opportunities for Community Residents to Engage: The evaluation of facilities and amenities indicates several shortcomings, particularly in cleanliness, green spaces, and sanitation, which are essential for enhancing residential quality of life. Furthermore, there is substantial dissatisfaction with the availability and quality of social gathering spaces and recreational facilities, highlighting a failure to effectively promote social cohesion.

Inclusivity and Accessibility: The responses collected from Deh Jamshoro and Deh Sari indicate appropriate accessibility for local and private vehicular movement but inadequate provision for pedestrians and no cycling routes, signifying a lack of comprehensive inclusivity and accessibility measures.

Facilities and Amenities: The statistics for facilities and amenities in residential neighborhoods in Figure 9 reveal shortcomings in meeting desired levels, which could include issues related to cleanliness, green spaces, sanitation, public spaces, and health facilities.

Social Cohesion and Safety: The dissatisfying level of social gathering, community spaces, and cultural and recreational spaces for inhabitants in Figure 10 suggests a gap in fostering social cohesion and safety within the study area despite efforts by residents to support security.

Satisfaction Index: The overall dissatisfaction reflected in the satisfaction index (−308.775%) indicates residents’ discontent with the lack of socially engaged places in Hyderabad’s Qasimabad Taluka, encompassing factors related to community engagement, inclusivity, accessibility, and amenities.

5.2. Social Behavior in the Study Area

Table 5 shows measures of social sustainability through indicators (social behavior). The scores in Table 5 are derived from a combination of questionnaire responses and field visits. The purpose was to understand residents’ perceptions and behaviors related to social sustainability indicators identified and explained in the literature review section. The data used to build Table 5 include responses from residents regarding their knowledge of neighbors, frequency of social activities and gatherings, safety concerns, attachment to their residence, and ability to make new friends and also include the information gathered through field visits. These responses were categorized and analyzed to determine the level of social sustainability indicated by each indicator.

Table 5.

Locale inhabitant awareness about social sustainability (social behavior).

5.3. Key Findings

The literature review on planning practices for socially sustainable residential neighborhoods in Pakistan, specifically in Hyderabad, highlights several key findings:

- Firstly, there is a growing recognition of the importance of social sustainability (SS) in sustainable development agendas, emphasizing the need to integrate SS measures into residential areas [17].

- Secondly, the role of neighborhoods as the basic social unit crucial for city survival is emphasized, indicating the positive outcomes of incorporating social sustainability principles in neighborhood design [89].

- Thirdly, there is a focus on the need for inclusive and healthy living environments in urban areas, with a call for neighborhood sustainability assessment tools to prioritize the social pillar of sustainability to create more inclusive districts [68].

- Lastly, urban challenges in Pakistan, including social, physical, and economic hardships, underscore the urgency of bridging the gap in policy and practice to promote resilient and sustainable urbanization [90].

This study examined and evaluated the effects of the residential neighborhood design strategies in Qasimabad Taluka on the detrimental effects of the overall local population. This research identifies the main obstacles and gaps in sustainable community development. It entails estimating the social sustainability of the region as it stands now, identifying areas that require development, and creating plans to close any gaps.

These data points collectively support that while inclusivity, accessibility, and transportation are recognized as crucial factors, the responses from the study area suggest that these characteristics do not meet the desired level or standards expected for a socially sustainable residential neighborhood.

In public spaces, health and well-being are connected to buildings and can be enhanced by aesthetics and views; none seem to satisfy. The social activity for community engagement, social cohesion, and social equity needs public spaces for interaction, which seems complicated to find at a neighboring level. This research will help managers and builders become more proficient and also help develop communities negatively impacted by poor design. It will also assist governmental organizations and professional associations in creating fresh approaches to problems that impede the long-term development of building practices and experts [91,92].

The analysis of social sustainability features in Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad, reveals significant discrepancies when compared to findings from other developing countries. Studies such as Sadasivam and Alpana’s investigation of Delhi [78] and research on sustainable neighborhoods in Brazil highlight similar challenges [43], emphasizing the importance of community engagement, inclusivity, and accessibility. In contrast to the successful models observed in Brazil and the compact city frameworks discussed in “Compact Cities: Sustainable Urban Forms for Developing Countries”, Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro exhibit notable shortcomings in cleanliness, green spaces, and overall sanitation, reflecting broader issues with facilities and amenities. Furthermore, while Delhi and other urban areas have made strides in improving social cohesion and safety, the dissatisfaction in Hyderabad regarding social gathering spaces and recreational facilities indicates a failure to meet these crucial needs. The stark contrast with the Jordanian study [42], which reveals more successful integration of social sustainability practices, underscores the urgent need for Hyderabad to enhance its infrastructure and policies to achieve comparable outcomes in community engagement and social well-being.

There is a relationship between neighborhood planning practices and social sustainability centers around how well planning initiatives integrate social equity, community cohesion, accessibility, and the overall well-being of residents [4,11]. Although if planning practices prioritize these aspects, neighborhoods can become more inclusive, resilient, and supportive of residents’ needs. However, conversely, a lack of attention to social sustainability can lead to various issues, such as diminished quality of life, social disparities, and challenges in creating a cohesive community [3,35]. The case of Qasimabad Taluka in Hyderabad exemplifies a disconnect between planning practices and social sustainability, highlighting the need for incorporating social sustainability into community design processes for community well-being [36,93].

This study’s finds out that there is a significant correlation between urban form and social sustainability. Pattern, placement, and design of open spaces at various community levels and the resulting space between buildings considerably promote people’s ability to meet and create social ties. This aids the neighborhood’s social sustainability. As a result, improving the neighborhood’s social aspect dramatically depends on its physical design to build a sustainable community.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this investigation into planning practices for socially sustainable residential neighborhoods in Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad City, Pakistan, has revealed several key findings. This study focused on opportunities for community resident engagement, inclusivity, accessibility, facilities and amenities, and social cohesion and safety and analyzed the characteristics of socially sustainable neighborhoods.

The findings reveal a significant dissimilarity between the community’s social building priorities for a morally sustainable neighborhood and the current state in the study area. Residents voiced discontent with activities aimed at increasing community participation. They indicated that social divisions result from many conditions not linked solely to factors such as street hygienization, lighting, and water supply. The parameters of accessibility and the inclusivity of the local community were discovered to be not well considered. The pedestrian and cycling infrastructure within the neighborhood is the most affected. Thus, the basic infrastructure and resources essential for the residents’ welfare were minimal.

Furthermore, the need for improving social links and security was suggested by inhabitants, who did not have an acceptable social area for gathering, and public parks with insufficient attention were mentioned as reasons that are impacting safety. The general trend of the residents’ satisfaction was downward, and some important factors along the lines of adequate water supply, cycling routes, plentiful green areas, and proper traffic lights were poorly scored.

This research also mentioned physical design as one factor that boosts social sustainability. It explained the connection between urban structure and community welfare. The results are a wake-up call for strategic intervention to consider all people’s necessities for social life, preventing and providing for accessibility, and creating a secure living environment and welfare in every respect.

Without strong community ties, residents may lack a robust social support system. In times of crisis or need, individuals may find it challenging to access support from their community, exacerbating vulnerabilities. The characteristic in Table 6 was formed having taken into account the results of a wide-ranging survey data analysis, expert assessments, and field visits relative to social sustainability indicators. The indicators were examined to ascertain how much of an impact they have on social sustainability scores. Once the scores were available, the indicators were grouped into levels such as ‘low’, ‘moderate’, and ‘high’ based on the magnitude to which they affect social sustainability outcomes.

Table 6.

Conclusion assessment for Qasimabad Taluka Hyderabad (as a socially sustainable neighborhood).

This study’s conclusions as an assessment of Qasimabad are presented in Table 6, showing that neighborhood planning practices and social sustainability are unrelated in Qasimabad Taluka Hyderabad, and the results and findings gathered for Qasimabad lead to higher dissatisfaction to attain social sustainability in a residential neighborhood. The findings of the results for socially sustainable neighborhood planning in the case of Qasimabad Taluka, Hyderabad, show a significant variance in reaching and satisfying the level required to achieve socially sustainable goals (Target 11.7) and indicate that neighborhoods with higher social sustainability scores also have higher resident satisfaction. However, the study discovered that several obstacles, including a shortage of funds, a lack of political will, and insufficient public participation, make it difficult to achieve social sustainability in neighborhood planning and its crucial component of neighborhood planning that affects resident satisfaction with social sustainability. Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach that involves policy interventions, community engagement, and efforts to bridge social gaps. Promoting inclusivity in education, improving healthcare accessibility, fostering cultural exchange, and combating discrimination are critical components of building a socially cohesive and inclusive community.

It was also evident from the available results that the planning practices applied in Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro from 1979 to 2010 were mostly based on conventional planning style and had neglected the social sustainability aspect in establishing housing schemes. The conventional aspect only considered the parks and mosques as the only social interaction places. The reason might be that the sustainable development concept was introduced in 1992, whereas Deh Sari and Deh Jamshoro were developed from 1979, so the planners and architects of the residential neighborhoods of these two dehs followed the conventional planning practices. Up until now, these professionals designed housing schemes on the same conventional style like the case of London Town, which was developed in 2006.

Dealing with these gaps and challenges will become an essential thing that will add to social sustainability in Qasimabad Taluka. Proposed interventions could involve working on the physical infrastructure and establishing public spaces where the community could meet. Improving public spaces and promoting a civic attitude among residents might also be part of this process. By spotlighting these issues, planners can address livability and social matters; the neighborhoods can thus become sustainable.

It is therefore recommended that the Hyderabad Development Authority, Qasimabad Taluka Office, and Hyderabad Municipal Corporation should consider these issues and develop the residential schemes by considering the social sustainability factors. The policy makers and planners of Sindh province and Pakistan should also make amendments in their policy documents at the provincial and national levels to introduce design guidelines for residential neighborhoods on the basis of sustainability and its three pillars.

7. Limitations of the Study

Sustainable development is traditionally understood through three interconnected pillars: social, environmental, and economic. This research, however, concentrated solely on the social pillar, with a specific focus on Goal 11, and particularly Targets 11.7 and 11.7.1. This study thoroughly examined elements such as community engagement, inclusivity and accessibility, facilities and amenities, and social cohesion and safety. It did not extend to exploring the relationship between social and economic sustainability, nor did it address the environmental dimension of sustainability. As a result, future research could benefit from investigating the links between social and environmental sustainability, as well as examining the interactions among all three pillars of sustainable development to achieve a more holistic understanding.

Author Contributions

Data gathering by H.M. and S.K.; formal analysis by M.A.H.T. and I.A.M.; investigation by H.M.; methodology by H.M., S.K. and M.A.H.T.; project administration by M.S. and N.A.; supervision by S.K., M.A.H.T. and I.A.M.; writing—original draft by H.M.; writing, review and editing by H.M., S.K., M.A.H.T. and I.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Department of City and Regional Planning and Research and Ethics Committee (protocol code 04324, 15 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

The informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to the data collection process. All participants were informed that data will only be used for academic purposes and that their personal information will not be disclosed at any stage. All participants were aged above 18 years.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the Department of City and Regional Planning, Mehran University of Engineering and Technology, Jamshoro, Pakistan, for providing a conducive research environment in the field of Urban Planning.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Lloyd Lawhon, L. The neighborhood unit: Physical design or physical determinism? J. Plan. Hist. 2009, 8, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.R.; Mabdeh, S.N.; Nassar, A. Social Sustainability in Gated Communities versus Conventional Communities: The Case of Amman. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 2141–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.L. Origin of the neighbourhood unit. Plan. Perspect. 2002, 17, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, T. Integrating social equity in sustainable development practice: Institutional commitments and patient capital. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcraft, S. Social Sustainability and new communities: Moving from concept to practice in the UK. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littig, B.; Griessler, E. Social Sustainability: Acatchward between political pragmatism and social theory. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehan, A.; Soflaei, F. Social Sustainability in Urban Context: Concepts, Definitions, and Principles; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, M. Urban Policy Engagement with social sustainability in Metro Vancouver. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; Lee, G. Critical factors for improving social sustainability of urban renewal projects. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 85, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.; Wilson, L. A Critical Assessment of Urban Social Sustainability; The University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Secher, L.K. Measuring Social Sustainability in the Small-Scale Built Environment, UNICA Euromaster in Urban Studies 4Cities; Universite Libre de Bruxelles UNICA: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, S.M.; Beatley, T. The Sustaınable Urban Development Reader, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aparna, N. Clean India. Journal of Geo. Sci. and Environ, Protection. 2015, 3, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- U. N. E. a. S. Council. Sustainable Development Goals. Distr.: General, 2021. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/28467E_2021_58_EN.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Saha, D.; Paterson, R.G. Local Government efforts to promoteth “Three Es” of sustainable development; survey in medium to large cities in the United States. Plan. Educ. Res. 2008, 28, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golić, K.; Kosorić, V.; Stamatovic Vuckovic, S.; Kujundzic, K. Strategies for Realization of Socially Sustainable Residential Buildings: Experts’ Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvi, H.; Soomro, M.; Memon, I.A. Influence of Socio-economic Factors on Mode Choice of Employees in Karachi City. Glob. Econ. Rev. 2022, 7, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojago, E. The Role of Social Sustainability in the Designation of a Sustainable Community: Based on Cumulative Development Patterns in Residential Complexes. In Environmental Resilience and Management; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marvi, H.; Soomro, M.; Bhutto, S. Comparative Analysis of Passive Parks of Hyderabad City with National Reference Manual. Glob. Reg. Rev. 2022, 7, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okot-Okumu, J.; Luwaga, A. Neighborhood planning as a strategy for achieving sustainable urban development in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2016, 82, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme–UN-Habitat. The Europa Dictionary of International Organisations 2022 2022. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussein, M. Social capital and resilience in low-income communities: A case study from Jordan. Urban Plan. 2017, 2, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sas-Bojarska, A.; Rembeza, M. Planning the city against barriers. Enhancing the role of public spaces. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 1556–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. From Garden City to Eco-urbanism: The quest for sustainable neighborhood development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planning Commission. Framework for Economic Growth. Government of Pakistan; Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, M.; Peacock, C. Social Sustainability: A comparison of studies in UK, USA and Australia. In Proceedings of the 17th Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 16–19 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, L.; Gauntlett, E. Housing and Sustainable Communities Indicators Project: Stage 1 Report-Model of Social Sustainability; WACOSS (Western Australia Council of Social Service): West Leederville, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahramanpouri, A.; Abdullah, A.S.; Sedaghatnia, S.; Lamit, H. Urban Social Sustainability Contributing Factors in Kuala Lampur Streets. In Asian Conference on Environment-Behaviour Studies; Elsevier: Tehran, Iran, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia: Magill, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lamit, H.; Ghahramanpouri, A.; Sedaghatnia, S. Urban Social Sustainability Trends in Research Literature. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Colantino, A. Urban Social sustainability thems and assessment methods. Proceeding Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2010, 2, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcraft, S.; Bacon, N.; Caistor-Arendar, L.; Hackett, T. Design for Social Sustainability: A Framework for Creating Thriving New Communities; Young Foundation: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, W.; Noor, S.; Tariq, A. The development of a basic framework for the sustainability of residential buildings in Pakistan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, Z.A. Assessing Social Capital with Respect to Urban Forms in Pakistan. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. (TURCOMAT) 2021, 12, 5075–5092. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, N.; Hassan, R.; Qureshi, N.N. Home Developing National Urban Policies. A Case Study of Pakistan; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Waseem, H.B.; Talpur, M.A.H. Impact Assessment of Urban Pull-factors to cause Uncontrolled Urbanization: Evidence from Pakistan. Sukkur IBA J. Comput. Math. Sci. 2021, 5, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancell, S.; Thompson-Fawcett, M. The social sustainability of medium density housing: A conceptual model and Christchurch case study. Hous. Study 2008, 23, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G.; Power, S. Urban form and social sustainability: The role of density and housing type. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2009, 36, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armin, R.; Farajian, P.; Eghbali, H. Sustainable Neighborhood Planning (Case Study: Gisha Neighborhood). SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ismu, R.D.A.; Gunawan, P.; Fikriyah, F.; Dian, D.; Fadly, U.; Nabila, E.P.; Achmad, T.N.; Masamitsu, O. Reciprocity and Social Capital for Sustainable Rural Development. Societies 2024, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.A.; Alshdiefat, A.S.; Rana, M.Q.; Kaushik, A.; Oladinrin, O.T. Evaluating social sustainability in Jordanian residential neighborhoods: A combined expert-user approach. City Territ. Archit. 2022, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, A.P.L.; Reboita, M.S.; Silva, L.F.; Gerasimova, M.K.; Sant’Anna, D.O. Sustainable neighborhoods in Brazil: A comparison of concepts and applications. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 6001–6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, U.; Biswas, A.; Mukherjee, J.; Mahata, D. Sustainable Urbanism in Developing Countries; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J. Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marvi, H.; Soomro, M.; Das, G. Rehabilitation and Revitalization of Slum Area: A Case Study of Tower Market Hyderabad. Glob. Reg. Rev. 2021, 6, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.H.; Marvi, H.; Soomro, M. Factors Encouraging Single Occupant Vehicle Users to Adopt Sustainable Alternative Mode Choice. Glob. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2022, 7, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenks, M.; Burgess, R. Compact Cities: Sustainable Urban Forms for Developing Countries; Taylor & Francis e-Library: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, M.; Hyowon, L. The paradox of sustainable city: Defination and example. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 1267–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Joan, M.W.; Ester, L.A. Creating Communities of Choice: Stakeholder Participation in Community Planning. Societies 2018, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridou, I.; Papadopoulos, A.M.; Hegger, M. A feasibility evaluation tool for sustainable cities–A case study for Greece. Energy Policy 2012, 44, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, M.R.; Jackson, J.E.; Sanders, S.R.; Erickson, L.D.; Morlan, T.; Brown, R.B. The Manifestation of Neighborhood Effects: A Pattern for Community Growth? Societies 2020, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachel, K.; Hubert, L.-Y. What is a Neighbourhood? The Structure and Function of an Idea. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2000, 27, 815–826. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.; Chan, E.; Xu, Y. Sustainable development and the rehabilitation of a historic urban district—Social sustainability in the case of Tianzifang in Shanghai. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban Regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakseresht, S.; Fazeli, M. Toward a social sustainability-based strategy for Urban Regeneration in Tehran. In Impact Assessment and Responsible Development for Infrastructure, Business and Industry; International Association for Impact Assessment: Puebla, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ferial, A.; Ali, A.; Sara, P.Z.; Rahman, A.N. Restoration Strategies of Naghsh-e-Jahan Square to Achieve Social Sustainability Based on Users Visions. Soc. Sci. 2011, 39, 4985–4992. [Google Scholar]

- Zetterberg, L.; Eriksson, M.; Ravry, C.; Santosa, A.; Ng, N. Neighbourhood social sustainable development and spatial scale: A qualitative case study in Sweden. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.R. Investigating social sustainability in public housing: Case studies of projects in Jordan. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Urban Design and Planning, Leeds, UK; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, E. Social Sustainability in Residential Communities “The Quality of Life through Users’ Behavioral Attitudes”. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.N.; Elmokadem, A.A.E.; Ali, S.M.; Badawey, N. Improve Urban Form to Achieve High Social Sustainability in a Residential Neighborhood Salam New City as a Case Study. Buildings 2022, 12, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kindy, S.K. The Effect of Spatial Organization on the Sustainability of the Neighborhood Unit in the Residential Environment. J. Eng. 2012, 18, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, W.; Mohamed, M.; Saoudi, H. Assessment of urban sustainability in collective residential neighborhoods A case study of the neighborhood of 400 dwellings in the city of M’sila. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 38, 835–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labin, A.E.; Sqour, S.; Rjoub, A.; Al Shawabkeh, R.; Al Husban, S. Sustainable Neighbourhood Evaluation Criteria -Design and Urban Values (Case study: Neighbourhoods from Al-Mafraq, Jordan). J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2022, 31, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Noora A, C.; Emad, M.; Imad, A.; Abdulsamad, A. Sustainable Neighborhood Assessment: Evaluating Residential Sustainability in Sharjah City’s Old Neighborhoods Using the UN-Habitat’s Sustainable Neighborhood Principles. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, F.M.; Ferreira, F.A.; Correia, R.J. Ranking residential neighborhoods based on their sustainability: A cm-bwm approach. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2022, 26, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A. Designing Innovative Sustainable Neighborhoods; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arab, W.; Mohamed, M.; Saoudi, H. Urban sustainability assessment of development and urbanization tools Case study of land occupancy plan No. 08 in the city of Ain Khadra, Algeria. Tech. Socila Sci. J. 2022, 38, 895–902. [Google Scholar]

- Marvi, H.; Khaskheli, R.; Soomro, M. Urban Green Spaces; Strategic Design Proposal for Conservation: The Case Study of Hyderabad City (Provide Future Development Control Guidelines). Glob. Sociol. Rev. 2022, 7, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. A New Strategy of Sustainable Neighbourhood Planning: Five Principles; Urban Planning and Design Branch, UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kalwar, S.; Marvi, H.; Samoo, S.K. Development Prospects for Medium-Size Cities of Southeast Asian Countries. Res. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. Rev. 2022, 3, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Planning & Development Department, Sindh. Planning and Development Department Government of Sindh. 2020. Available online: https://pnd.sindh.gov.pk/ (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Sindh Ordinance no. VI of 1976. The Hyderabad Development Authority Ordinance, 1976.

- P. B. o. Statistics. In District at a Glance Hyderabad; Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2023.

- Loayza, N.; Tomoko, W. Public infrastructure trends and gaps in Pakistan. FID4SA-Repository: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peerzado, M.B.; Magsi, H. Population and Causes of Agricultural Land Conversation in Hyderabad, Sindh, Pakistan. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim bin, A.; Hasnita bin, H. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities: The Case of Organizational Research. Selangor Bus. Rev. 2017, 2, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivam, K.; Alpana, S. Social sustainability and neighbourhood design: An investigation of residents’ satisfaction in Delhi. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 849–870. [Google Scholar]

- The Open University. 6 Methods of Data Collection & Analysis; The Open University: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]