Abstract

Background: Despite many young players showing strong potential, only a small fraction succeeds in the critical transition from youth to elite senior football. This scoping review synthesizes research on the junior-to-senior transition in men’s football, identifying main topics related with barriers and facilitators in the transition. Methods: Searches were performed in four databases (PubMed, Scopus, SPORTDiscus, and Web of Science) according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA, 2020) guidelines, using the following keywords: “football*” OR football AND talent* OR “talent identification” OR “talent development” OR expert* OR gift* AND “junior-to-senior” OR “transition career” or “athlete career transition” OR “transition phase”. Original articles in English focused on the junior-to-senior process in male footballers were included. Results: From 5307 titles, 35 studies met eligibility criteria. The most examined themes were psychosocial factors, including social support, stressors, and resilience. The reviewed studies identified organizational structure and effective club communication as facilitators and emphasized the importance of physical attributes to meet senior-level demands. Conclusions: Overall, the junior-to-senior transition is multifaceted, shaped by psychosocial, organizational, and physical factors. Despite robust research, gaps remain; future longitudinal and interdisciplinary studies should inform evidence-based strategies for optimizing player development and retention.

1. Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that the talent development processes in football is both complex and multidimensional [1]. Studies demonstrated that early success in youth football does not necessarily predict achievement at the senior level, highlighting the complex and non-linear nature of talent development pathways [2,3]. To improve progression from elite junior to elite senior levels of sport, a clear understanding of talent development is necessary.

Entry into a professional first team remains the primary benchmark for evaluating a successful athletic career in football [4,5]. A comprehensive understanding of athletic careers requires exploring the interplay between athletes’ multiple life domains (e.g., sport, education, employment) and the developmental trajectories they navigate as talented youth progress through their careers [6]. Effectively managing transitions within and beyond sport enhances an athlete’s likelihood of sustaining a long and successful sporting career and facilitates a smoother adjustment to retirement. Conversely, difficulties in coping with transitional phases are frequently associated with negative outcomes, including premature dropout from sport [7]. Within an ecological dynamics’ framework, “barriers” are constraints in the performer–environment relationship that limit young players’ capacity to adapt to senior-level demands, while “facilitators” denote supportive constraints and resources that enhance perception–action coupling, learning opportunities, and functional adaptation during the junior-to-senior transition [8,9].

Within the talent development process, the primary objective of football academies is to identify and nurture young talented players, an endeavour typically associated with achieving sporting success and generating financial returns for the club [10]. Nevertheless, statistics show that fewer than 10% of junior football players progress to the professional level, meaning that over 90% do not achieve professional status [5,11,12]. These players typically either leave the academies and are replaced by emerging talent, continue participating at a recreational level, or withdraw from sport entirely [13,14].

To reach professional status, football players must successfully navigate the junior-to-senior transition (JST), a critical phase marked by progression from junior (under-19) to senior (open age) competitions, which is especially important for those aspiring to elite levels in the sport. Research consistently identifies the JST as the most critical and challenging phase within an athlete’s career-long talent development in football, typically lasting between one and four years [15,16], and is considered as the most career-defining transition [17]. The JST is well known for its high dropout rate, and about 80% of athletes experience the JST as a crisis. Difficulties arise when young athletes lack the personal and contextual resources to manage increased performance demands, emotional pressures, and shifting social expectations. Factors such as weak coping skills, marginalization of athletic identity, insufficient institutional support, and negative sociocultural influences heighten vulnerability. Emotional barriers, unexpected events like injuries, and the absence of positive role models further hinder adaptation. Without adequate guidance and intervention, these challenges reinforce a downward spiral of stagnation and disengagement [18].

Stambulova and Samuel [19] defined “transitions as turning phases in athletes’ career development associated with a set of specific demands that athletes have to cope with in order to continue successfully in sport and/or the spheres of their life’s” (p. 119). Early work on talent development, such as Bloom’s [20] work, identified distinct stages through which talented individuals progress across domains, including, science, art, and sport. This talent development pathway comprises three stages: (1) the initiation stage where young athletes are introduced to organized sports and during which they are identified as talented athletes; (2) the development stage during which athletes become more dedicated to their sport and where the amount of training and level of specialization is increased; (3) the mastery or perfection stage in which athletes reach their highest level of athletic proficiency.

Several theoretical frameworks have shaped research on talent identification and development. Early work, notably on deliberate practice [21], laid the foundation, but later models emphasized the importance of transitions in athlete development. Key frameworks include: (1) the Athletic Career Transition Model [15,22], which views transition as coping with specific demands; (2) the Holistic Athletic Career Model [23], linking athletic, psychological, psychosocial, academic/vocational, financial domains across a career; (3) the Athletic Talent Development Environment Model ATDE: [24,25,26] which situates the junior-to-senior transition within a dynamic ecological system. Inspired by Bronfenbrenner’s [27] bio-ecological theory the ATDE highlights the layered environment influencing development, from immediate micro-level settings and their interrelations, through macro-level contexts, to the organizational culture of clubs, which collectively shape the effectiveness of talent development [28].

From a talent development perspective, a normative (predictable) from junior elite to senior elite would be ideal; however, the volatile nature of professional football often makes this transition unpredictable and stressful for players [29,30,31].

Current research on the junior-to-senior transition in football remains limited and predominantly cross-sectional, with most studies focusing on youth stages rather than systematically tracking outcomes at the senior level [32]. The existing literature underscores the multifaceted nature of this transition, which involves increased performance demands, intensified psychological and physical stressors, and substantial shifts in social and organizational contexts. Furthermore, a range of additional factors, including coaching approaches, competition intensity, injury management, psychological resilience, and the availability of social and institutional support, physical and maturational factors may also play a decisive role in shaping young players’ adaptation during this critical developmental stage [17,33,34,35].

The aim of this review was to organize and synthesize the available scientific literature on the male junior-to-senior transition in football, identifying key research topics and the main barriers and facilitators in this transition.

2. Materials and Methods

The present review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [36]. The protocol was registered by an expert element on the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/JBZXR, accessed on 26 June 2025).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The present review included studies that: (1) centered their attention in male football junior-to-senior transition; (2) contained relevant information on the junior-to-senior transition process; (3) examined changes over time and offered insights into development within the review’s context; (4) were original studies written in English. The studies were excluded if they: (1) included data from female athletes; (2) do not include relevant information concerning the topic under study; (3) were written in language others than English; (4) were grey literature.

2.2. Information Sources, Search and Selection Process

Four databases were searched (PubMed, Scopus, SPORTDiscus, and Web of Science) for published articles until 24 March 2024 (date of the search) using the following search terms: (“football*” OR soccer) AND (talent* OR “talent identification” OR “talent development” OR expert* OR gift*) AND (“junior-to-senior” OR “transition career” or “athlete career transition” OR “transition phase”). Subsequently, the references were exported to a citation management software (EndNoteTM 21.0, ClarivateTM), that was used also for the screening process. Duplicates were automatically removed and manually checked to ensure that duplicates were removed with precision. Two independent authors (JT and HS) examined the manuscripts for eligibility based on the title, abstract and full text review. Where discrepancies occurred, a third author (DVM) was consulted and solved the disagreements by consensus.

2.3. Quality of the Studies, Data Extraction and Synthesis

The overall methodological quality of the studies was assessed using two tools: (1) the 21-item Critical Review Form by Letts et al. [37] for qualitative studies; (2) the 16 item critical review form for quantitative studies by Law et al. [38].

Each qualitative article was subjected to an objective assessment to determine whether it contained the 21 critical components: objective (item 1), literature reviewed (item 2), study design (items 3, 4 and 5), sampling (items 6, 7, 8 and 9), data collection (descriptive clarity: items 10, 11 and 12; procedural rigor: item 13), data analyses (analytical rigor: items 14 and 15; auditability: items 16 and 17; theoretical connections: item 18), overall rigor (item 19) and conclusion/implications (items 20 and 21). On the other hand, quantitative studies were assessed to determine whether they included the16 items: objective (item 1), relevance of background literature (item 2), appropriateness of the study design (item 3), sample included (items 4 and 5), informed consent procedure (item 6), outcome measures (item 7), validity of measures (item 8), significance of results (item 10), analysis (item 11), clinical importance (item 12), description of drop-outs (item 13), conclusion (item 14), practical implications (item 15) and limitations (item 16). Item 9 (details of the intervention procedure) was not applicable because none of the studies included interventions.

The outcomes per item were 1 (meets criteria), 0 (does not meet the criteria fully), or NA (not applicable). A final score expressed as a percentage was calculated for each study by following the scoring guidelines of Faber et al. [39]. This final score corresponded to the sum of every score in each article divided by the total number of items scored for that specific research design (i.e., 16 or 21 items). As in previous studies (see, for example, Sarmento et al. [40]) we adopted the classifications of Faber, Bustin, Oosterveld, Elferink-Gemser and Nijhuis-Van der Sanden [39] and Te Wierike et al. [41] and classified the articles as: (1) low methodological quality—with a score ≤50%; (2) good methodological quality—score between 51 and 75%; and (3) excellent methodological quality—with a score > 75%.

The methodological quality of the studies was evaluated independently by two authors (JT and DM). A third author (HS) was consulted to solve the cases of disagreement between the two authors.

A data extraction sheet (from Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group’s data extraction template [42], was customized to this review’s study inclusion requirements and then pilot tested on ten randomly selected studies. Data were extracting according to the Participants/Exposure/Outcomes framework developed to build the search question. Based on each study’s aim, two authors (JT and HS) independently extracted the main data.

3. Results

3.1. Search, Selection and Inclusion Publication

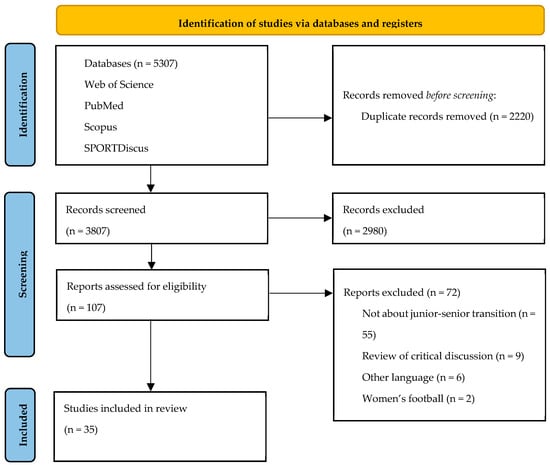

The search performed on databases identified 5307 manuscripts. Duplicates were removed (2220 studies) and the title and abstract of the 3087 remaining papers were screened according to the eligibility criteria. Subsequently, 2980 papers were deleted, and 107 records were examined in full text. Of these, 72 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria and were removed for the following reasons: (1) the paper did not present relevant information concerning junior-to-senior transition (n = 55); (2) the manuscripts are not an original paper (n = 9); (3) six articles were not written in English; (4) two articles were related to women’s football. Finally, 35 manuscripts were included in the present review, and they were retrieved for the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the studies included in the present review.

3.2. Quality of Studies

Concerning the quality of studies, the most noteworthy results were that: (1) the mean score for the 21 selected quantitative studies was 89.17%; (2) the mean score for the fourteen selected qualitative studies was 88.47%; (3) two publications achieved the maximum score of 100%; (4) no publication scored below 75%; (5) fourteen studies scored between 76 and 89%; and (6) 17 publications achieved an overall rating of >90%. All studies included in present review exceeded the minimum quality threshold, and therefore quality scores did not influence the synthesis of results. The versions of the Critical Review Forms used in this study are shown in Electronic Supplementary Material Tables S1 and S2.

3.3. General Description of Studies

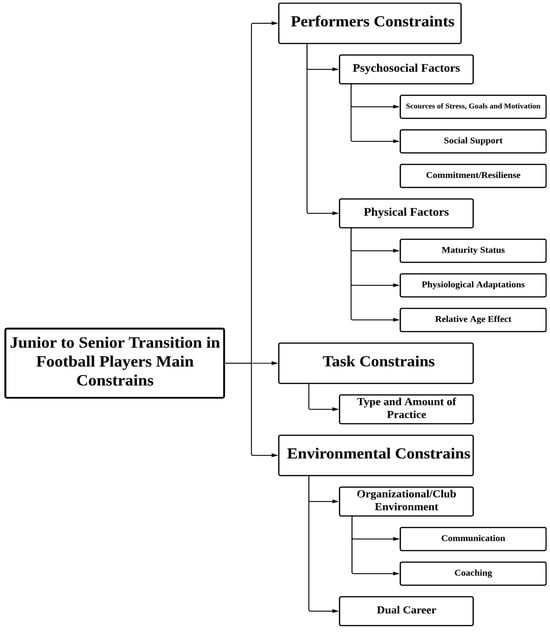

The ecological dynamics framework posits that behaviour can only be understood at the level of the performer–environment relationship, where interactions are shaped by a constellation of personal, task, and environmental constraints operating across multiple, interdependent timescales [43]. Based on this theoretical rationale, after careful analysis, and following a similar strategy of previous reviews on this topic [40,44], it was decided that the most appropriate way to present the results would be to categorise them according to the major research topics that emerged from the analysis (Figure 2): (1) performers constrains: psychosocial and physical factors; (2) task constrains; (3) environmental constrains: organizational/club environment and dual career.

Figure 2.

Scopes about junior-to-senior transition in football.

The sample characteristics (i.e., country, number of participants, sport, and age) are summarized in Table 1. Fourteen manuscripts (40%) included studies related to psychological aspects, seven (20%) included physical characteristics, and fourteen (40%) organizational, communicational, dual career, training characteristics and other topics. The studies included in this review involved players form different countries in Europe, North America, and Asia, covering different contexts, in which their analysis proved to be relevant, contributing to a more comprehensive and detailed understanding of the subject in question. The 35 manuscripts analysed in this review include studies carried out between 2005 and 2023. However, there has been a significant increase in the number of publications over the last decade.

Based on an ecological dynamics theoretical approach, we argue that talent should be considered as a dynamically varying relationship shaped by the constraints imposed by the physical and social environments, the tasks experienced and the personal resources of a player [45]. The context of modern football is characterised by repeated evaluation of footballers’ potential to succeed at the elite, adult level. Studies were organized into three main topics: performer constrains (i.e., studies that combined psychosocial constrains and physical constrains) (Table 1); task constrains (Table 2); and environmental constrains (organization/club environment and dual careers) (Table 3).

3.3.1. Performers Constraints

Physical Factors

Three main sub-themes were addressed in studies that focused on athletes’ physical characteristics: (1) maturity factors, (2) body growth, and (3) RAE (Table 1). Maturation plays a crucial role in the development of athletes, influencing how talent is perceived. Players who mature early often have temporary physical advantages, which leads to them being recognized as more talented football players. This highlights the need for careful evaluation beyond physical maturity to ensure a fair assessment of talent [63]. Maturation is the process through which individuals progress toward adulthood, involving structural and functional changes in their bodies as they transition from youth [66]. Although their chronological age may be similar, there is significant inter-individual variability in maturation status [67]. Maturation status refers to the stage of maturation at a specific point in time, representing an individual’s biological development at the moment of observation [68].

Body characteristics develop significantly during adolescence. Players who perform highly in childhood and early adolescence may not necessarily become successful professionals in adulthood [11]. About RAE, five studies compared relative age as a factor in selection or non-selection to become elite senior players during the transition phase [60,61,62,64,65]. Male footballers born in the fourth quarter are around four times more likely to reach professional status as adults than those born in the first quarter. Despite being fewer in number, players born in the fourth quarter face greater challenges in reaching their potential and this adversity helps them develop stronger coping mechanisms, promoting resilience and motivation. These characteristics are crucial for a successful transition from youth to senior level [61,62,65].

3.3.2. Task Constraints

Type and Amount of Practice

Some studies (Table 2) have shown the importance of training type and how essential they are to deepening knowledge [30,69,70,71]. Adapting to senior competition after ten years of youth football practice was identified as necessary for all the participants, requiring greater mental and physical demands [30].

Table 2.

Summary of studies that reported task constrains.

Table 2.

Summary of studies that reported task constrains.

| Study | Country | Sample Characteristics | Aim | Results | Practical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kannekens et al. [71] | Netherlands | n = 105 (age 16–18 years) Football | To identify possible key factors that help in predicting success over time. | Positioning and deciding is the tactical skill that best predicts the performance level in adulthood, with a correct classification of over 70% in players who are about to make the transition from youth competitions to the adult competition | Tactical expertise is a prerequisite for expert performance in sports and demonstrates the quality of a player to perform at the highest level. |

| Ford and Williams [70] | England | First Group: n = 16 (professional); Second Group: n = 16 (non-professional); (age 15 at the time) Football | To examine differences in the development pathways of elite youth football players in England who progressed to professional status in adulthood compared to those who did not. | After starting in football at 5 years of age, professional players in England followed the early engagement pathway throughout childhood during which they spent more time in football specific practice and play activity compared to those who did not progress to professional status in adulthood. | The development path of young players can be conditioned by the quality of practice and the path followed, whether in academies or not, may not be ideal for future performance. |

| Hendry and Hodges [69] | Scotland | n = 102 (born in 1996/1997) Football | To explore sport-specific practice on the development | Players that transitioned to adult-professional status from early youth elite levels gained early entry into a football academy, engaged in high volumes of football specific practice and play activities throughout their youth careers (defined by majority engagement in football from childhood), and participated in several sports other than football during childhood. | Athletes that successfully transition to adult professional football are best characterized by an early (majority) engagement pathway. |

| Swainston et al. [30] | England | n = 6 17–18 years Football | To describe evolving perspectives of young players experiences going through the junior-to-senior transition in professional football. | The transition from the academy to the first team is initially marked by the pressure of securing a professional contract. Contract decisions, adaptation to senior competition, barriers to transition without initial success, and social and psychological aspects of life—such as education, interpersonal relationships, and future vocation—provide unique contributions to the literature. Adapting to senior competition after ten years in youth football is identified early as a priority requiring greater mental and physical demands. Being in the first team changing room and in first-team stadiums is reported as valuable for adaptation and motivation, while the lack of first-team opportunities remains a significant barrier to successful transitions. | Players were required to adjust to training demands and a new social dynamic while learning new avenues of formal and informal support from the organization, with being on loan or playing with the U23s forming part of the process, as players focused on continuing to work toward their goals; the loan system served as the primary method for adapting to the physicality, decision-making, and style of play demands of senior football, alongside the distinct focus on winning matches and accumulating positive statistics, while the U23s offered opportunities to impress first-team staff; being comfortable with senior players and performing on the pitch helped in being accepted within the senior team, and social skills should not be overlooked, with opportunities for interaction between academy and first-team players helping to bridge the transition gap; additionally, the organization’s culture is fundamental, as initial negative perceptions—including demoralization, feelings of being ignored or unsupported, and the importance of patience and effort—play a decisive role in enabling opportunities over time. |

3.3.3. Environmental Constraints

Organization/Club Environmental and Dual Careers

Table 3 summarizes studies that combined organizational, communication, coaching and dual career, or in addition, covered other topics. A considerable number of studies (n = 10) are focused on understanding the main factors (e.g., competitive contexts, player development organizational structure, resources and barriers) that contribute to attain or develop expertise in the management factors. Four studies present organizational issues and the influence of strategies (e.g., communication between youth and senior team, players recruitment diversity, individual players development) in the sports context as a determining factor for success [72,73,74,75]. Six studies identify the importance that coaches play in the development of young athletes, covering technical and personal aspects, as well as communication and dual careers [76,77,78,79,80,81].

Table 3.

Studies that addressed predominantly environmental constrains.

Table 3.

Studies that addressed predominantly environmental constrains.

| Study | Country | Sample Characteristics | Aim | Results | Practical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaeyens et al. [76] | Belgium | n = 2.138 aged 16–39 years Football | To evaluate the benefit of the U-21 Belgium rule. | Many football teams appear either to lack the ability to develop young native players or are reticent to develop local youth talent to a level that allows under-21 players to be integrated into the first team, while reduced playing opportunities for younger football players occur because coaches are somewhat reluctant to select them for first-team matches due to their lack of match experience. | The most gifted youngsters had already been transferred to better sides and given opportunities to play in those first teams, while the reduced playing opportunities within the under-21 group in this study may stem from the ability of coaching and management personnel within clubs to effectively foster their existing young talent. |

| Relvas et al. [77] | Different countries (England, Portugal, Spain and Sweden) | n = 26 (HYD—head of youth departments); England (n = 6), Portugal (n = 5), Spain (n = 9), France (n = 2) and Sweden (n = 4) Adults Football | To explores the organizational structure and working practices of professional football clubs concerning young player development. | All the clubs noted that the main objective of their youth development programme was to develop players for their first team but there is an apparent gap between the first team, and the youth environments acts as an additional barrier to the player’s progression. | The lack of proximity and formal communication between the youngsters and the professional environment, regardless of the structure, causes dissatisfaction among the staff and seems to hinder the coherent progression of young players into the professional environment. |

| Larsen et al. [78] | Denmark | n = 22 (under 17 players) and the staff (club house manager; youth coaches for the under-13, under-15, under-17, and under-19 teams; sport manager; and team assistants) n= NR | To describe the holistic ecological approach to research in talent development in sport highlights and hot it affects an athlete in his or her athletic development. | The transition from youth to professional football often suffers from a lack of proximal role models and communication between the youth and professional environments, while coaches have a special responsibility to support athletes in this transition and athletes must be instructed on how to maintain control over their activity and investment in elite sport. | The environment can be centred on the relationship between the players and a team of coaches, assistants and directors who help the players focus on the important issues. A holistic lifestyle, dealing with dual careers (sport and school), developing the ability to work hard and be self-aware and responsible for your own training. |

| Larsen et al. [81] | Denmark | n = 22 (under 17 players) and its associated coaches; Football | To present an ecological-inspired program and intervention in a professional football. | This subsequently led to another problematic characteristic, namely that communication between coaches and players about challenges, expectations, and potential pitfalls in the youth-to-professional transition was non-existent at the club, and closely linked to the culture, the initial assessment showed that important psychosocial skills—such as managing performance and process outcomes, coping with adversity, and setting personal goals—were not taught as a natural part of training, even though they were often emphasized as very important for the within-career transition to the professional level. | Missing link between the youth and the professional players resulting in a lack of role models, and a lack of focus on the development of psychosocial skills. |

| Morris et al. [72] | England | n = 17 (n = 14 male; n = 3 female); 18 to 62 years Football | To analyse the demands, resources and barriers associated with the youth-to-senior sport transition | Coaches can provide support, and experienced sport physiologists may have a greater understanding of how to assist players with physical development compared to coaches with limited training in this area, so providing coaches with education in sport physiology and psychology can help them support athletes transitioning from youth to senior sport, alongside their motivation to help young athletes advance; organizations used staggered introductions into the senior team to allow players to assess their abilities and integrate into the squad, while educating parents on ways to support their sons, and transition outcomes were influenced by structured transition programs, with financial investment in youth setups not necessarily correlating with higher player development rates. | Knowledge of the youth-to-senior transition in sport allows practitioners to support athletes from different backgrounds and cultures appropriately, while a proactive approach to identifying factors influencing the transition and creating a list of contributing variables may yield positive outcomes; however, when players face negative responses from fans after moving up to the first team, they may struggle to succeed, highlighting areas of good practice such as staggered first-team entry, and financial investment can enable clubs to provide greater support, through sport science, education programs, and other resources, thereby enhancing youth athlete development and increasing player retention. |

| Aalberg and SÆTher [73] | Denmark | Head coaches for the team including head coach, chief of development and top player development coach, and all well experienced youth level coaches n = 6 players Football | To focused on individual development and how external factors affect athletic performance | A weak relationship between the youth department and the professional team hinders the exchange of knowledge, proximity, and fluid communication between the U19 group and the professional team, as clubs aim to “protect” senior players while motivating youngsters to compete for their place, yet fail to foster stronger links, making the gap seem large, whereas providing players with a well-coordinated environment, including coordination between the sport and collaborative educational institutions, proves crucial for enabling individual performance and for the environment’s capacity to develop successful athletes. | The focus on providing players with tools and resources both on and off the pitch, using a holistic and systematic methodology, highlights that the missing link between the youth level and the professional team may indicate that these groups do not operate under the same streamlined approach, providing a clear rationale for implementing a common philosophy and shared goals. |

| Hendry et al. [79] | Scotland | n = 102 (born in 1996/1997) Football | To consider the implications for talent development models and purported links between play and creativity. | For the transition to youth-professional, physical skills matter for selection (as do tactical and technical skills), such that concerns over selection bias towards more physically capable players in adolescence appear valid. | Coach evaluations are key determinants in future decisions about successful progression to professional youth and adult status. |

| Carpels et al. [74] | Different countries (England, Italy, Spain, France and Germany) | n = ~12.000 Football | To compare the effectiveness of this direct youth-to-senior pathway | The realistic chances of young players successfully transitioning to an elite-level first team are minimal, with some suggesting a 0.012% success rate, yet financial constraints may actually increase the success of academy graduates, as club training players (CTPs) can provide significant returns through income generation or future sales, and qualifying a player as a home-grown player (HGP) incentivizes clubs to invest in youth development; players in this category undergo continuous development and maturation appropriate to their age, and clubs should exercise patience in managing CTPs, particularly as increased match involvement does not appear to hinder club success. | The mobility of players and the internationalization of club squads allow clubs to recruit globally, bringing specific qualities they seek, and an indicator of successful academy production would be the proportion of academy graduates playing in professional senior squads, including association-trained players (ATPs) and expatriates (EXPs), regardless of origin. |

| Mannix et al. [80] | USA and Canada | n = 80 Football | To explore organisational aims and structure | Young players may undergo a ‘developing mastery phase’ that strategically provides an environment closely replicating the first team, while coaches can encourage them to increase awareness and ownership of their development through reflective practice; an increase in physical demands, noted by both coaches and transitioning players, highlights differences in training and match loads between youth and senior levels, and poor communication between the first team, reserve team, and youth academy staff across management, coaching, sport science, and medical departments may impede progression, whereas having the youth academy and first team on the same training site eases the transition by allowing young players to observe and emulate their role models. | Coaches and sports science staff in a professional club’s academy must ensure that physical development programs prepare young players for the demands of professional football, while communication among staff during the transition may be unclear or ineffective, impairing development initiatives, and although bringing youth and professional players together in a single facility can support the transition, a cultural distance still exists that creates a gap in organizational practices and communication between the youth and professional entities. |

| McGuigan et al. [75] | Scotland | n = 7 Football | To observe the factors that, including technical competence, physical process and the development environment, combine to determine the progression of young players. | The athlete’s path to elite competence in sport is rarely straightforward and typically involves challenges or obstacles, with all players who reach the first team demonstrating the ability to overcome adverse events that develop resilience and mental toughness; players who display superior physical and technical performance are more likely to succeed in the transition to senior football, as first-team coaches are less likely to trust younger, untested players, while the ideal development environment includes elite-level training, player welfare, psychological support, elite facilities for the first and B teams, an elite culture and mentality toward training and performance from all academy staff, and consideration of a wide range of player factors at both macro and micro levels, with coaches and support staff adapting team training sessions, the club philosophy, and prioritization of individual players in a team environment highlighted as key factors influencing a successful transition to the first team. | Young players are rarely exposed to adverse scenarios that allow them to develop resilience, mental toughness, and individualized development, which can hinder progression to the first team, with players possessing advanced physical and physiological capabilities more likely to advance, while a lack of specific post-academy training to meet development needs may be mitigated through loans for B team players deemed ready for first-team football, and the role of coaches or other professionals in the youth-to-first-team transition is crucial for safeguarding and supporting the development of young players within the first-team environment. |

4. Discussion

The article aimed to systematically review and organize the available literature on the junior-to-senior transition in male football players. Our findings reveal a marked and growing scholarly interest in this critical phase of athlete development (see Section 3.3). The review highlights that a substantial body of research focuses on establishing normative benchmarks for the transition and mapping performance trajectories from early developmental stages.

The transition from youth to senior football is a complex process shaped by the interaction of psychological, physical, social, and organizational factors. Success at this stage depends not only on technical and physical proficiency but also on the ability to adapt mentally and socially to the demands of professional sport.

Quantitative studies identify key predictors of successful transitions, such as sustained soccer-specific practice, advanced tactical awareness, and psychological attributes like motivation, resilience, and goal commitment. Physical maturity also plays a role, as more mature players often access greater competitive opportunities. However, those who display strong psychosocial skills, notably self-regulation, balanced passion, and the ability to combine sport with education, tend to adapt more effectively and maintain long-term development. Qualitative research highlights that the transition is rarely linear, being affected by uncertainty, pressure, and organizational gaps. Communication and alignment between academy and senior environments are decisive: while disconnection and limited psychological support hinder progress, shared methodologies and unified club philosophies promote smoother integration. Coaches emerge as key mediators, providing emotional and practical guidance during adaptation to new professional demands.

Across studies, common themes include the importance of psychological resilience, motivation, and organizational coherence. Environments that are both challenging and supportive foster players’ confidence and coping abilities. Ultimately, effective transitions rely on holistic, individualized approaches that integrate psychological support, coordinated club structures, and authentic learning opportunities within professional settings, allowing clubs to convert potential into sustainable performance.

These insights underscore the complexity and multifaceted nature of progressing from youth to elite senior football, emphasizing the need for continued, nuanced investigation.

4.1. Performers Constraints

4.1.1. Psychosocial Factors

Sources of Stress, Goals and Motivation

The limited opportunities for progression and the significant challenges associated with the junior-to-senior transition may contribute to mental health difficulties among talented youth football players [82,83]. Studies examining sources of stress during the junior-to-senior transitions consistently highlight competitive stressors, including, perform pressures, fear of making mistakes, the need to capitalise on limited opportunities, and insufficient time to prepare for senior-level training [55]. First-team experiences and opportunities should be viewed as integral components of a structured and holistic development process [58] ensuring that even those athletes who have signed professional contracts, despite being particularly vulnerable during this phase, receive appropriate support and are better equipped to employ effective coping strategies [57].

According to Morris, Tod and Eubank [59], within-career transition experiences among highly motivated athletes often generate both self-imposed and externally imposed pressure to achieve success. Given the numerous challenges faced during the junior-to-senior transition, many players fail and are subsequently released from professional football academies. This release can lead to significant psychological consequences, with players reporting experiences of depression, anxiety, identity disturbance, diminished self-worth, and reduced confidence, all of which negatively impact the quality of their transition out of full-time football [56]. Therefore, the implementation of preparatory programmes becomes essential, aiming to equip young players with psychological resilience, career adaptability, and coping strategies to deal with uncertainty and potential deselection. Such programmes could focus on mental skills training, identity management, educational guidance, and the development of alternative career plans, thereby promoting a smoother and more sustainable transition experience [52]. Football academies could develop pre-release programs aimed at preparing players for release by developing a series of psychosocial skills, which could support their transition out of football. Given the highly competitive nature of professional football and the limited opportunities for progression, it is crucial that players are encouraged to proactively prepare for alternative career pathways, thereby promoting long-term well-being and adaptability beyond football.

Goals or life aspirations that people pursue can influence their well-being, their progression within sport and the success of their careers [84]. Motivation plays a fundamental role in sports as it influences why and how athletes engage in the activities they have chosen, affecting the quality of their engagement and ultimately their performance [85]. As stated by Holt and Mitchell [53], pathway thinking includes strategic career planning and involves taking personal responsibility for development rather than only working hard for coaches. This was reminiscent of the notion of volition [86], who suggest that volition consist of knowing how to motivate oneself when other control processes fail. Volition involves working hard (especially training hard) to pursue a goal for oneself rather than uniquely appeasing one’s coaches, and it is closely related to the notion of planning careers. Hope theory [87] is based on the belief that goals are attainable, viewing hope as a positive motivational state driven by agency and pathway thinking, with goals serving as its foundation. Emerging evidence suggests that successful athletes are more likely to engage in strategic career planning, whereas their less successful counterparts often do not [53]. These differences highlight the importance of both personal and institutional support mechanisms in distinguishing elite from sub-elite athletes.

Social Support

Football support derived from key interpersonal relationships (e.g., coaches, parents, peers) in a sporting context has been identified as an important resource for athletes [88]. In a highly competitive environment, athletes who were able to adapt to the stressful circumstances possibly developed coping skills and social resources more frequently and more flexibly than those who did not encounter those circumstances [49]. Also, those athletes who attach importance to achievements in multiple spheres of life may become better prepared to deal with the transition to elite or professional football [13]. Some studies [50,89,90,91] reinforce the idea of developing policies among key stakeholders, ensuring the creation of supportive environments for talent development. These supportive environments include: (1) an integrated approach to player growth; (2) alignment between organizational objectives; (3) the establishment of strong social support structures; (4) a commitment to player well-being [47].

Jordana, Ramis, Chamorro, Pons, Borrueco, De Brandt and Torregrossa [46] explored the fact that many football academies are completely focused on turning talented youngsters into professional football players, overlooking that the majority won’t reach that goal. As a result, only a minority of players achieve professional status, while many others are left without adequate resources to cope with adversity during transition. However, the findings suggest that implementing proactive intervention programmes, targeting the demands, barriers, and available resources associated with transitions, could not only support the holistic development of young athletes but also enhance club outcomes in terms of reputation and long-term financial performance.

Commitment and Resilience

Some studies have addressed the importance of commitment and resilience in athletes. Resilience can be defined as a dynamic process of positive adaptations within a context of adversity [92,93], protecting young athletes from stressful situations or threatening scenarios [94]. In turn, sport commitment is characterized by the desire to continuously participate in a sport over time [95], maintaining adequate levels of dedication to achieve success in the progression of their careers in high performance or professional academy structures [96]. Individual factors, namely, sporting performance, self-esteem, and the athletic identity along with investing more time into the development of a performance-based identity are tied to a better performance [51] which, in turn, correlates with the influence that commitment and resilience have on a successful junior-to-senior transition [97]. Finally, Lundqvist, Gregson, Bonanno, Lolli and Di Salvo [54] referred resilience and motivation as essential player’s qualities for successful transitions, with players taking personal responsibility for their development, supporting them to stay involved in sport and better cope transitions and difficulties better [52].

4.1.2. Physical Factors

Maturity Factors

Biological maturation can significantly influence young players’ transition to senior football. Bolckmans, Perquy, Starkes, Memmert and Helsen [63] found that early-maturing players are often perceived as more talented due to temporary physical and fitness advantages. In contrast, late-maturing players must rely more on technical skill and creativity to compensate. Interestingly, initial physical disadvantages can evolve into long-term developmental benefits, as those who remain in the system may gain multifactorial superiority. Bolckmans and colleagues also reported a reversal of maturational bias during the junior-to-senior transition, suggesting that biologically younger players may eventually outperform their earlier-maturing peers. Notably, eliminating the relative age effect in academies may unintentionally diminish the developmental advantages associated with the “less likely players” hypothesis, which posits that relatively younger athletes benefit from competing against more mature peers.

These less likely late-maturing players to succeed hypothesis posits that the junior-to-senior transition bias in elite football may favour chronologically younger players within elite youth academies [98]. To remain competitive and secure retention in academies, relatively younger and late-maturing players often must independently develop creativity alongside advanced technical, tactical, and psychological skills. Although these abilities may be less evident in childhood and early adolescence, they typically become more pronounced during late adolescence and early adulthood, as differences in age and physical maturity lessen or even reverse [99]. Late-maturing players may also benefit from prolonged childhood and adolescent stages, allowing for longer learning and perceptual-motor skill development, further enhancing their creativity as football players [100]. Importantly, the less likely players to succeed hypothesis only holds if relatively young and late-maturing players are selected and retained in youth academies. The challenging environment they navigate is key to encourage and facilitate the development of superior technical, tactical, and psychological skills [98], because these skills might only become evident as players mature and transition into higher levels of competition. These findings are supported by Ostojic and colleagues, who demonstrated that late-maturing football players are more likely to achieve success at the elite level compared to their early-maturing peers [101].

Physiological Adaptations

Like maturational factors, physiological adaptations in young elite footballers, assessed through a talent selection model that incorporates anthropometric, maturational, physical fitness and motor coordination characteristics, are used as predictors of future career success [102]. Dugdale, Sanders, Myers, Williams and Hunter [11] found that players who were recruited earlier from the academy showed poorer physical performance during their first years at the academy; however, the rates of development observed throughout adolescence were substantially higher for successful players, contributing to increased performance during the transition from youth to senior football. Although there were several major limitations in this study, we acknowledge the widespread use of reductionist physical qualities assessments to support and influence decision-making for the selection, deselection and progression of players in the academy system [102,103]. More importantly, numerous factors beyond isolated physical attributes influence player success and career progression. Early maturing players benefit from temporary physical advantages, which can influence selection and early performance, but these advantages often fade over time and do not guarantee senior-level success. In contrast, late-maturing players may develop superior technical, perceptual, and tactical skills, which become increasingly evident as they reach late adolescence and adulthood. Accounting for maturational status in training design, load management, and selection strategies can enhance both fairness and the effectiveness of transitions. Integrating these physical considerations with broader developmental factors ensures that talent identification and player support systems capture potential beyond immediate physical performance, ultimately facilitating a more equitable and successful progression from youth to senior football [104,105].

Thus, physical performance alone cannot determine advancement. Researchers should adopt a holistic approach that integrates a wider array of performance qualities to better identify meaningful indicators of successful junior-to-senior transitions.

Relative Age Effect (RAE)

Variations in maturity within age groups can hinder talent identification, as relatively older players are more frequently selected. Pressure on clubs and coaches to deliver immediate results often leads to favouring players with a short-term advantage due to their birthdate, thereby risking the exclusion of those with greater long-term potential. These studies demonstrate how selection processes are strongly influenced by RAEs, particularly benefiting players born in the first half of the year [60,61,62,64,65]. However youth experience is a limited indicator of success in the senior team [64], contrasting with other finds that indicate that relatively younger players are more likely to reach football success at senior level [65] or to achieve a professional contract [61].

The RAE has been explained based on cognitive and physical maturation. Athletes who were born earlier (relatively older athletes) in the selection year had significant advantages when compared with those who were chronologically younger (relatively younger athletes) [106]. This tendency might have reduced the chances of discovering talented athletes born later in the reference year [60] or players born earlier may be mistakenly perceived as more likely to succeed and cannot be confirmed for the senior category [64]. An RAE in adult football could be accompanied by a loss of valuable players during the youth phase of the career and limiting the pool of talented players at the adult level [61]. In Italian football national teams, Boccia, Brustio, Rinaldi, Romagnoli, Cardinale and Piacentini [64] revealed that only 9% to 15% of junior players progress to the senior national team, with date of birth significantly influencing selection, favouring those born early in the calendar year. Brustio, Lupo, Ungureanu, Frati, Rainoldi and Boccia [60] confirmed this trend in the U-15 categories but noted that the disparity diminishes with age. These findings show that promising younger players are often overshadowed by older counterparts, causing talent loss in the early stages of development, while older players often fail to transition to senior levels, resulting in talent loss later in their journey [64]. This was confirmed by Kelly et al. [107], who highlighted that players born in the fourth quarter of the year are four times more likely to reach adult professional status compared to players born in the first quarter [62]. Considering the relevance of these data, coaches and other professionals must implement strategies to support players during junior-to-senior critical transition [61].

4.2. Task Constraints

Type and Amount of Practice

Practice design plays an essential role in the development of athletes and can directly influence their performance. Practice should replicate the technical, tactical, physiological, and psychological demands of the match, incorporating the variability and complexity of formal match performance [108]. The transition to senior competition environment, normally after a decade practicing in youth football, tends to be set as a key goal, demanding for a better preparation to the new social dynamic [30]. Two studies found that players who successfully transitioned from youth elite academies to adult professional status engaged in high volumes of football-specific practice and play throughout their youth, while also participating in multiple sports during childhood, unlike those who did not reach professional levels [69,70].

Positioning and decision-making are the tactical skills that best predict performance in players transitioning from youth to adult competitions. According to Kannekens and colleagues, players with high proficiency in these skills have approximately a sevenfold greater chance of reaching the professional level compared to those with lower scores [71].

The loan system, whereby a club temporarily transfers a player to another team, serves as a key pathway for adapting to the physical, tactical, and decision-making demands of senior football [30]. It also exposes players to the intense, result-driven pressure of senior environments focused on winning matches [109] and the challenge of managing performance expectations, such as accumulating strong match statistics at their loan clubs [110]. A second pathway to prepare players for senior team competition is the establishment of U23 teams by clubs, which offer a tailored environment and additional opportunities to facilitate the transition to the senior squad [30]. Moreover, players who felt comfortable playing alongside senior teammates demonstrated a greater ability to integrate into the squad and perform well in matches [72,111]. In turn, strong performance facilitated their acceptance within the senior team [109]. For the junior-to-senior transition, players must adapt to the demands of new practice regimen and a new social professional dynamics, while at the same time learning new forms of formal and informal support from the organization to work towards their goals [30].

4.3. Organizational/Club Environment

4.3.1. Communication and Coaching

High-level clubs typically provide players with a well-coordinated and structured environment, offering the necessary tools and resources to enable them to concentrate fully on their on-pitch performance and development [72,73]. The development environment, the club’s philosophy and the prioritisation of individual players within the context of the team were also highlighted in the literature as key factors influencing a successful transition [74,75]. The ability to align these characteristics with the requirements of senior football highlights the importance of creating development pathways that bridge the gap between youth and senior contexts [112].

Coaches play a fundamental role in the global development of athletes and can adopt more transformational training behaviours, thus promoting a greater likelihood of athletes having positive sporting experiences [81,113], namely by increasing the opportunities of young players to play in the senior team [76] or having high quality, structured, sport specific practice, that can positively contribute to the development of football skills [79].

Additionally, verbal communication plays a crucial role in ensuring clear and consistent messages among players, coaches, and staff, which can simultaneously improve team dynamics and generate a suitable environment to develop player skills and their integration into higher levels of competition [114,115]. The communication gap between youth and professional environments, whether physical or cultural, can hinder the coherent progression of young players the first senior team [77]. Even if academies that have a variety of strategies for developing players, they may fail to prepare the players for the senior team, if communication between staff is not clear and effective [80]. Young players are rarely exposed to adverse scenarios that allow them to develop resilience, mental toughness [81,116] and coping skills adapted to their individual needs [75], which may be detrimental to their progression towards first-team. Players with advanced physical and psychological capabilities are more likely to progress to the first team [117] but there tends to be a lack of specific post-academy training to meet development needs [75]. A potential solution to this problem could be to create and strengthen a better relationship between the development department and the professional team [73] and/or the role of the coach or specialized professional, challenging those involved in the physical preparation of young players to provide a training stimulus similar to the demands of senior teams, preparing players for the transition from youth to senior team [118].

4.3.2. Dual Career

Understanding the career of players through the umbrella of the Holistic Athletic Career Model [119], underlines a global approach to the career development of athletes and considers that an athletic career is defined by different stages of development that integrate other life domains [120]. In their review of dual career research, [121] identified several benefits of a dual career approach, which included individual development, enhanced sports performance and, in the longer term, enhanced life satisfaction.

Research investigating elite athletes’ career pathways showed that they typically follow one of three trajectories: (1) focusing exclusively on sport; (2) combining sport and education/work while prioritizing sports-based development; (3) constructing a stable dual career pathway. These three pathways, labelled as linear, convergent, and parallel [120], are associated with different psychosocial implications of career transitions (e.g., career ending, injury), with only the stable dual career trajectory being found to safeguard athletes’ broader personal development, employability and re-integration into society after the end of their career in elite sport [122,123]. A holistic lifestyle can integrate with dual careers (sport and school/work), developing the ability in junior athletes to work hard and be self-aware and responsible for your their training [81]. Also, some athletes have a career assistance program that organizes the athletes’ environment to their advantage [78].

4.4. Barriers and Facilitators

Taken together, the evidence indicates that the transition from junior to senior football is shaped by a complex interplay of psychological, physical, social, and organizational factors, which can act either as barriers or facilitators of development. According to the reviewed studies, facilitators of successful progression include strong psychological skills such as resilience, self-regulation, intrinsic motivation, and goal commitment. Players capable of managing uncertainty and maintaining focus under pressure are more likely to adapt effectively to the demands of professional football. Likewise, holistic development environments characterized by consistent technical, tactical, and psychosocial support, enhance adaptability and confidence. Close coordination between academy and senior structures, involving shared methodologies, gradual exposure to first-team contexts, and coaching continuity, further supports smoother transitions. Supportive interpersonal relationships with coaches, teammates, and family, alongside dual career pathways that balance sport and education, also contribute to players’ long-term engagement and well-being.

In contrast, the literature identifies several barriers that compromise the transition process. Chief among these are organizational misalignments, including poor communication between development levels, inconsistent coaching philosophies, and limited opportunities for young players to experience competitive senior football. Such gaps disrupt developmental continuity and foster insecurity. Psychological barriers, including performance anxiety, lack of confidence, and limited coping strategies, often emerge when players face increased external pressure without adequate support. Moreover, early maturation advantages can distort selection processes, reducing developmental opportunities for late-maturing players who might possess equal or greater potential in the long term.

Overall, these findings reinforce that the success of the junior-to-senior transition depends on the alignment of individual, relational, and structural dimensions. Clubs that promote coherent organizational cultures, sustain psychological support, and progressive exposure to senior demands are better positioned to transform emerging talent into sustained professional performance.

4.5. Limitations

A limitation of this review is the restriction to male football and English-language publications. This inevitably excluded evidence from women’s football but ensured conceptual consistency and maintained comparability across career structures and development pathways that differ substantially between men’s and women’s football.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review highlights that the junior-to-senior transition in football is unpredictable and shaped by a complex interplay of physical, psychological, technical, and social factors. Despite early demonstrations of talent, many young players struggle to adapt to the higher intensity, competition, and expectations of senior football. Success at this stage requires not only physical maturity and tactical understanding but also psychological adaptability and the ability to cope with professional demands. Players must integrate into new social dynamics, working alongside older teammates and building resilience within increasingly pressurized environments.

Crucial to this process are coaches and club structures that bridge the gap between youth and professional levels. Effective coordination, shared methodologies, and consistent communication across departments facilitate smoother transitions, while fragmented systems and inconsistent feedback hinder player development. The development of psychological skills, particularly resilience, motivation, and self-regulation, emerges as essential for sustaining progress and managing setbacks.

Interpersonal support from family, friends, and teammates helps maintain well-being, while integrating education and career planning provides stability beyond sport. A dual-career approach and exposure to progressively demanding environments foster long-term growth and readiness for senior competition.

Overall, the review identifies clear barriers and facilitators in the transition process. Facilitators include strong psychosocial support, coherent organizational structures, and coaches capable of guiding both performance and personal growth. Barriers arise from lack of communication between academy and senior teams, limited opportunities for gradual adaptation, and psychological stress linked to performance pressure and uncertainty. Ultimately, successful transitions depend on aligning individual qualities with supportive environments that treat the transition as an ongoing developmental process rather than a single decisive moment.

6. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

Despite growing attention to the junior-to-senior transition in football, notable research gaps persist. Most studies are cross-sectional, offering limited insight into the dynamic and evolving nature of the transition over time. Longitudinal research is needed to examine how psychological, physical, and social factors interact throughout development. While individual attributes such as resilience, motivation, and self-regulation have been explored, less is known about how these skills are cultivated and sustained in real-world club environments. Organizational and cultural influences, such as communication between departments, coaching alignment, and club philosophy, remain underexamined, as do the perspectives of key stakeholders, including coaches, sport directors, and families. The dual-career dimension, often cited as vital for holistic athlete development, lacks football-specific empirical investigation. Furthermore, methodological imbalances between quantitative and qualitative studies limit the integration of objective performance data with lived experiences. Addressing these gaps requires global, longitudinal, and mixed method approaches that link individual development with organizational processes and socio-cultural contexts, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the barriers and facilitators shaping successful transitions to senior football.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sports13120440/s1, Supplementary Table S1: Risk of bias assessment in quantitative studies; Supplementary Table S2: Risk of bias assessment in qualitative studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T., D.A. and H.S. (Hugo Sarmento); methodology, J.T., D.M., J.R., H.S. (Honorato Sousa) and H.S. (Hugo Sarmento); software, J.T., J.R. and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T., D.A., H.S. (Honorato Sousa) and H.S. (Hugo Sarmento).; writing—review and editing, J.T., D.A., D.M., J.R., H.S. (Honorato Sousa), A.F. and H.S. (Hugo Sarmento). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the present article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| JST | Junior-to-senior transition |

| RAE | Relative age effect |

References

- Adam, L.K.; Craig, A.; Williams Cook, R.; Sáiz, S.L.J.; Wilson, M.R. A multidisciplinary investigation into the talent development processes at an English football academy: A machine learning approach. Sports 2022, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güllich, A.; Barth, M.; Macnamara, B.N.; Hambrick, D.Z. Quantifying the extent to which successful juniors and successful seniors are two disparate populations: A systematic review and synthesis of findings. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiros, A.; Côté, J.; Fonseca, A.M. From early to adult sport success: Analysing athletes’ progression in national squads. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 14, S178–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, P.R.; Bordonau, J.L.D.; Bonanno, D.; Tavares, J.; Groenendijk, C.; Fink, C.; Gualtieri, D.; Gregson, W.; Varley, M.C.; Weston, M. A survey of talent identification and development processes in the youth academies of professional soccer clubs from around the world. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossmann, B.; Lames, M. From talent to professional football–youthism in German football. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2015, 10, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylleman, P. An organizational perspective on applied sport psychology in elite sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambulova, N.; Alfermann, D.; Statler, T.; Coté, J. ISSP position stand: Career development and transitions of athletes. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 7, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, K.; Araújo, D.; Seifert, L.; Orth, D. Expert performance in sport: An ecological dynamics perspective. In Routledge Handbook of Sport Expertise; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, D.; Sarmento, H.; Resende, R.; Gomes, A.R. Football coaching, the Portuguese way: The ecology of practice as the referent for evidence-based coach education. In The Routledge Handbook of Coach Development in Sport; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024; pp. 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, A.P.; Hall, H.K.; Appleton, P.R.; Kozub, S.A. Perfectionism and burnout in junior elite soccer players: The mediating influence of unconditional self-acceptance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugdale, J.H.; Sanders, D.; Myers, T.; Williams, A.M.; Hunter, A.M. Progression from youth to professional soccer: A longitudinal study of successful and unsuccessful academy graduates. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. The Tyranny of Talent: How it Compels and Limits Athletic Achievement... and Why You Should Ignore It; Aberrant Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro, J.L.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido, J.J. The critical transition from junior to elite football: Resources and barriers. In Football Psychology; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 324–336. [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa, M.; López Chamorro, J.M.; Ramis Laloux, Y. Transición de júnior a sénior y promoción de carreras duales en el deporte. Rev. De Psicol. Apl. Al Deporte Y Al Ejerc. Físico 2016, 1, e6. [Google Scholar]

- Stambulova, N. Talent development in sport: The perspective of career transitions. In Psychology of Sport Excellence; Hung, T.-M., Lidor, R., Hackfort, D., Eds.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2009; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Stambulova, N.B. Developmental sports career investigations in Russia: A post-perestroika analysis. Sport Psychol. 1994, 8, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, K.; Morris, R.; Tod, D.; Eubank, M. A meta-study of qualitative research on the junior-to-senior transition in sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 45, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambulova, N.B. Crisis-transitions in athletes: Current emphases on cognitive and contextual factors. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambulova, N.B.; Samuel, R.D. Career transitions. In The Routledge International Encyclopedia of Sport and Exercise Psychology; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B. Developing Talent in Young People; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Krampe, R.T.; Tesch-Römer, C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambulova, N. Symptoms of a crisis-transition: A grounded theory study. In SIPF Yearbook 2003; Hassmén, N., Ed.; Svensk Idrottspsykologisk Förening: Örebro, Sweden, 2003; pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wylleman, P.; Reints, A.; De Knop, P. A developmental and holistic perspective on athletic career development. In Managing High Performance Sport; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 191–214. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, K. The Ecology of Talent Development in Sport: A Multiple Case Study of Successful Athletic Talent Development Environments in Scandinavia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Dinamarca, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, K.; Stambulova, N.; Roessler, K.K. Holistic approach to athletic talent development environments: A successful sailing milieu. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, K.; Stambulova, N.; Roessler, K.K. Riding the Wave of an Expert: A Successful Talent Development Environment in Kayaking. Sport Psychol. 2011, 25, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, K.; Larsen, C.H.; Storm, L.K. All You Need to Know About Talent Development in Sport; Athlete Insight Press: Centennial, CO, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Champ, F.M.; Nesti, M.S.; Ronkainen, N.J.; Tod, D.A.; Littlewood, M.A. An exploration of the experiences of elite youth footballers: The impact of organizational culture. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2020, 32, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swainston, S.C.; Wilson, M.R.; Jones, M.I. Player experience during the junior to senior transition in professional football: A longitudinal case study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wylleman, P.; De Knop, P.; Reints, A. Transitions in competitive sports. In Lifelong Engagement in Sport and Physical Activity; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brustio, P.R.; McAuley, A.B.; Ungureanu, A.N.; Kelly, A.L. Career trajectories, transition rates, and birthdate distributions: The rocky road from youth to senior level in men’s European football. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1420220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, A.; Stambulova, N.B. Individual pathways through the junior-to-senior transition: Narratives of two Swedish team sport athletes. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2020, 32, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexe, D.I.; Čaušević, D.; Čović, N.; Rani, B.; Tohănean, D.I.; Abazović, E.; Setiawan, E.; Alexe, C.I. The Relationship between Functional Movement Quality and Speed, Agility, and Jump Performance in Elite Female Youth Football Players. Sports 2024, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čaušević, D.; Rani, B.; Gasibat, Q.; Čović, N.; Alexe, C.I.; Pavel, S.I.; Burchel, L.O.; Alexe, D.I. Maturity-Related Variations in Morphology, Body Composition, and Somatotype Features among Young Male Football Players. Children 2023, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letts, L.; Wilkins, S.; Law, M.; Stewart, D.; Bosch, J.; Westmorland, M. Critical Review Form–Qualitative Studies (Version 2.0); McMaster University: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Law, M.; Stewart, D.; Pollock, N.; Letts, L.; Bosch, J.; Westmorland, M. Guidelines for Critical Review of Qualitative Studies; McMaster University, Occupational Therapy Evidence-Based Practice Research Group: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, I.R.; Bustin, P.M.; Oosterveld, F.G.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Nijhuis-Van der Sanden, M.W. Assessing personal talent determinants in young racquet sport players: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, H.; Anguera, M.T.; Pereira, A.; Araújo, D. Talent Identification and Development in Male Football: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 907–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Wierike, S.; van der Sluis, V.; Van Den Akker--Scheek, I.; Elferink--Gemser, M.; Visscher, C. Psychosocial factors influencing the recovery of athletes with anterior cruciate ligament injury: A systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, C.C.a.C.R. Data Extraction Template for Included Studies. Available online: http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Davids, K.; Araújo, D.; Vilar, L.; Renshaw, I.; Pinder, R. An ecological dynamics approach to skill acquisition: Implications for development of talent in sport. Talent Dev. Excell. 2013, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, D.; Travassos, B.; Carmo, J.M.; Cardoso, F.; Costa, I.; Sarmento, H. Talent Identification and Development in Male Futsal: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, K.; Güllich, A.; Shuttleworth, R.; Araújo, D. Understanding environmental and task constraints on talent development: Analysis of micro-structure of practice and macro-structure of development histories. In Routledge Handbook of Talent Identification and Development in Sport; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Jordana, A.; Ramis, Y.; Chamorro, J.L.; Pons, J.; Borrueco, M.; De Brandt, K.; Torregrossa, M. Ready for failure? Irrational beliefs, perfectionism and mental health in male soccer academy players. J. Ration.-Emotive Cogn.-Behav. Ther. 2023, 41, 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Brannagan, P.M. Navigating the club-to-international transition process: An exploration of English Premier League youth footballers’ experiences. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 18, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, J.L.; Torregrosa, M.; Sánchez Oliva, D.; Garciá Calvo, T.; León, B. Future achievements, passion and motivation in the transition from junior-to-senior sport in spanish young elite soccer players. Span. J. Psychol. 2016, 19, E69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Yperen, N.W. Why some make it and others do not: Identifying psychological factors that predict career success in professional adult soccer. Sport Psychol. 2009, 23, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.O.; Gledhill, A.; Shand, R.; Littlewood, M.A.; Charnock, L.; Till, K. Players’ perceptions of the talent development environment within the English Premier League and Football League. Int. Sport Coach. J. 2021, 8, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]