Simple Summary

Essential oils from eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) and lantana (Lantana camara) were explored as sustainable, dual-action biopesticides against the maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais) and its associated fungal pathogens. Both oils proved to be potent insecticides, achieving 100% weevil mortality at a 10% concentration within 24 hrs. However, eucalyptus oil was significantly more effective overall: it maintained 100% mortality even at a lower 5% concentration and acted as a superior antifungal agent, inhibiting fungal growth (including the dominant species, Fusarium solani) by up to 93%. Chemical analysis suggests this higher efficacy is attributable to its primary constituent, eucalyptol (52.8%), leading to the conclusion that Eucalyptus globulus essential oil is a promising natural control agent for both the weevils and the fungi they harbor.

Abstract

To control maize weevils (Sitophilus zeamais), a major pest of stored grains, this study explores the use of essential oils from Eucalyptus globulus and Lantana camara as natural biopesticides. Given the risks of synthetic pesticides, these oils offer a sustainable alternative. The research first identified ten fungal pathogens associated with the weevils, including the dominant species, Fusarium solani. Preliminary results showed that both oils were then tested for their ability to kill the fungi and the weevils. Eucalyptus globulus oil proved to be a superior antifungal agent, inhibiting fungal growth by up to 93%, significantly outperforming Lantana camara oil. Both oils demonstrated potent insecticidal properties, achieving 100% weevil mortality at a 10% concentration within 24 hrs. However, Eucalyptus oil was more effective, maintaining 100% mortality even at a lower 5% concentration, unlike Lantana oil. Chemical analysis showed that Eucalyptus oil’s high effectiveness may be associated with its main component, eucalyptol (52.8%). Lantana oil had a more varied composition, with caryophyllene (31%) as its primary constituent. The findings suggest that Eucalyptus globulus essential oil is a promising, two-in-one biopesticide capable of controlling both maize weevils and their associated fungal pathogens.

1. Introduction

Ensuring food security for a rapidly expanding global population requires sustainable strategies that safeguard both productivity and environmental health [1,2,3]. One of the major threats to stored grain reserves is the maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais), a destructive pest responsible for significant post-harvest losses worldwide [4,5]. While synthetic pesticides have effectively been employed to manage infestations, their continued use has led to widespread challenges, including ecological contamination [6,7], risks to human health [8,9], negative impacts on non-target organisms [10,11,12], and the emergence of resistant pest populations [13,14,15,16]. For instance, chemical insecticides such as malathion and chlorpyrifos often leave residue in grains [17], while fumigants like aluminium phosphide pose serious risks of toxicity through both ingestion and inhalation [5,18]. These limitations underline the need for safe, environmentally compatible pest control solutions.

Essential oils and other plant-derived bioactive compounds have gained increasing attention as viable alternatives to conventional pesticides. The pesticidal effects of essential oils are attributed to their complex secondary metabolites, including terpenoids, phenolics, flavonoids, and alkaloids [19,20,21,22], which display potent antimicrobial [23] and insecticidal properties [24,25]. Empirical evidence demonstrates their potential to suppress insect survival, reproduction, and feeding behaviour. For example, a study evaluated the insecticidal and repellent properties of free and microencapsulated Cinnamomum cassia essential oil (EO) against Sitophilus zeamais (maize weevil). The microencapsulated EO showed prolonged insecticidal activity, maintaining 45% efficacy on day 15 and remaining nearly stable for 65 days. The microcapsules also demonstrated reusability, retaining 70% mortality across five cycles, highlighting their potential as a sustainable approach to maize weevil management [26]. Similarly, Apium graveolens L. (celery) seed essential oil demonstrated potent insecticidal and repellent activities against the maize weevil, S. zeamais. Its effectiveness as a contact insecticide was dose- and time-dependent, with an LC50 of 19.83 nL/adult after 72 hrs. Furthermore, the oil exhibited strong repellent properties at concentrations above 16 µL/L of air, indicating its potential as a natural and sustainable alternative to synthetic pesticides [27].

A study by Yang et al. found that cinnamon oil was highly effective against S. zeamais via contact and fumigation, with its primary component being trans-cinnamaldehyde. However, the study noted its reduced efficacy in containers with grains, suggesting a need for controlled-release technologies to improve its persistence. Similarly, research by Pimenta et al. showed that clove essential oil and its main identified component, eugenol, had significant lethal, fumigant, and repellent effects. The oil was found to be highly toxic with an LC50 of 10.15 µL/g causing physiological and biochemical changes in the insect, highlighting its potential for pest control [28]. In addition to clove and cinnamon oils, other essential oils have shown promise. Several studies have evaluated the repellent properties of essential oils from different Eucalyptus species. For example, research by Ben Miri et al. found that the essential oils of Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus citriodora showed excellent repellent activity. Another study on Eucalyptus globulus essential oil by Ngongo-Kapenga et al. revealed a dose-dependent fumigant effect, with a volume of 30 µL causing the highest mortality [29]. Lastly, an investigation into oregano essential oil demonstrated its potent insecticidal activity. Its key identified active compounds, carvacrol and thymol, were found to be highly toxic and repellent, offering a promising, eco-friendly solution for pest management [29].

Species such as L. camara and Eucalyptus globulus are of particular interest, as their extracts demonstrate notable insecticidal and antifungal activities alongside a reduced environmental footprint [4,30,31]. Such findings highlight the efficacy of phytogenic pesticides, which are not only biodegradable but also exhibit broad-spectrum bioactivity with minimal ecological disruption. Eucalyptus essential oil (EO) is a promising alternative to synthetic pesticides because it is rich in bioactive compounds [32] which are reported to exhibit insecticidal, repellent, and antimicrobial properties [25]. Its biological activity is largely determined by the major terpene constituents α-pinene and β-caryophyllene [33]. Additionally, the global abundance of Eucalyptus biomass, high oil yields, and growing market demand make their large-scale extraction and application economically feasible. While Lantana oil is more locally abundant and underutilized, it offers multiple benefits as a pest control agent [34,35], owing to its diverse blend of bioactive compounds such as β-caryophyllene [36,37], α-pinene [38], and cadina-1(10),4-diene [39]. This complex phytochemical profile contributes to insecticidal, antifeedant, repellent, and antifungal activities, often through synergistic interactions among its constituents.

This study evaluates the insecticidal and antifungal potential of L. camara and E. globulus essential oils against the maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais) and its associated fungal pathogens. By identifying effective essential oil types and concentrations, this research contributes to the development of plant-based alternatives to synthetic pesticides, promoting sustainable pest management and reducing dependence on hazardous chemical practices. The efficacy of both essential oils was assessed through contact toxicity, repellence, and antifungal bioassays.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines for research involving living organisms and was approved by the University Research Ethics Committee (UREC) of Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha Campus. Ethics clearance was granted under protocol number WSU/FNS-GREC/2024/03/11/G5, ensuring adherence to institutional and international ethical standards. All experimental procedures were designed to safeguard the welfare of biological specimens and to maintain the integrity of insect-handling protocols.

2.2. Collection of Maize Weevils

The initial stock of maize weevils (Sitophilus zeamais) was obtained from GoodUkhanyo Farmer Development, Mthatha, Eastern Cape, South Africa (31°35′19″ S, 28°47′24″ E). The insects were reared on untreated maize kernels purchased from a local store and maintained under controlled laboratory conditions of 28.6 ± 2 °C, 65.6 ± 5% relative humidity, and a 12:12 light:dark (L:D) photoperiod. The cultures were kept in aerated glass jars with perforated lids covered by nylon mesh to prevent insect escape while allowing ventilation. Stock cultures were regularly renewed to maintain healthy insect populations for bioassays.

2.3. Collection of Plant Materials

Fresh leaves of L. camara and E. globulus were collected from the O.R. Tambo District, KSD Region, Eastern Cape, South Africa (31.7074° S, 28.5798° E). The region experiences an annual average rainfall of ~117 mm, with notable seasonal variation. Plant specimens were identified and authenticated by Mr. Prinavin Naidu (Herbarium Curator) and Dr. Madeleen Struwig (Taxonomist), Department of Botany, North-West University. Voucher specimens were deposited in the Walter Sisulu University Herbarium.

2.4. Preparation of Essential Oils

Fresh leaves of Lantana camara and Eucalyptus globulus (200 g each) were used for essential oil extraction following the hydrodistillation method described by Atti-Santos et al. [40]. Plant material was placed in a 500 mL round-bottom flask and submerged in 2.5 L of distilled water. The flask was heated on a mantle at 160–170 °C and connected to a Clevenger-type apparatus with a condenser to facilitate oil collection. Distillation was maintained for 3 hrs, after which the essential oils were collected, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate to remove residual moisture, and weighed. Oils were stored in airtight amber vials at 4 °C until use.

2.5. Isolation of Pathogenic Fungi

Adult maize weevils were surface-sterilized in 70% ethanol for 1–2 min, rinsed three times with sterile distilled water, and air-dried on sterile filter paper under a laminar flow hood (Laminar Airflow LLFV-204, Leicester, England, UK) Using sterile scalpels and forceps, insects were dissected, and internal tissues were aseptically transferred onto Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, Merck Biolab, Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa) plates. The plates were sealed with Parafilm® to prevent contamination and incubated (Scientific 160L Digital Incubator, Midrand, South Africa) at 25–28 °C in the dark for 10 days. Emerging fungal colonies were subcultured onto fresh PDA to obtain pure isolates.

2.6. Morphological Identification of Fungal Isolates

Fungal colonies were characterized based on macroscopic features, including colony color, texture, and growth patterns. Microscopic features were observed by preparing wet mounts in sterile distilled water and covering them with glass cover slips. Micromorphological traits such as spore shape, conidial arrangement, hyphal septation, and the presence of special structures (e.g., sclerotia, chlamydospores) were examined under a compound microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ni, Randburg, South Africa) and photomicrographs were taken for documentation. Preliminary identification was carried out using standard fungal taxonomic keys [41].

2.7. Molecular Identification of Fungal Isolates

2.7.1. Genomic Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) Extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from pure fungal cultures using the ZR Fungal/Bacterial DNA MiniPrep Kit (Catalogue No. 06005, Inqaba Biotec, Pretoria, South Africa), following the manufacturer’s protocol as adapted from Gopane et al. [41].

2.7.2. PCR Amplification

The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of rDNA was amplified using universal primers ITS1 and ITS4. PCR reactions (20 µL) consisted of 2 µL 10× buffer, 2 µL dNTP mix, 0.5 µL of each primer, 0.5 µL Taq polymerase, 9 µL nuclease-free water, and 5 µL template DNA. PCR cycling conditions were: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 50 °C for 30 s, and extension at 68 °C for 1 min (Bio-Rad C1000 TouchTM Thermal Cycler, Johannesburg, South Africa), with a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min.

2.7.3. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose gel (CSL-AG500, Cleaver Scientific Ltd., Rugby, Warwickshire, UK) stained with EZ-Vision® BlueLight DNA dye. DNA size was estimated using the NEB Fast Ladder (N3238; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA).

2.7.4. Sequencing and Data Analysis

PCR amplicons were purified using the ZR-96 DNA Sequencing Clean-up Kit™ (Zymo Research, Catalogue No. D4050, Inqaba, Pretoria, RSA) and sequenced bidirectionally using the ABI 3730xl Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA) with the BrilliantDye™ Terminator v3.1 Kit (Nimagen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands). Forward and reverse chromatograms were assembled into consensus sequences using CLC Bio Main Workbench veision 20.0.3. Sequences were analysed via BLAST version 2.16.0 against the NCBI GenBank database to confirm fungal identities.

2.8. Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils

The antifungal potential of L. camara and E. globulus essential oils was evaluated against ten fungal isolates obtained from S. zeamais. Fungal isolates were reactivated and maintained on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) until active mycelial growth was achieved. Spore suspensions were prepared by gently scraping 7-day-old cultures with sterile distilled water, filtering to remove hyphal fragments, and adjusting to a uniform inoculum density. For each treatment, 30 mL of molten PDA supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 was mixed with 2 mL of the spore suspension and poured into sterile 90 mm Petri dishes. After solidification, sterile 6 mm paper discs were placed equidistantly on the agar surface and impregnated with 20 µL of essential oil at concentrations of 100, 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 µL/L to assess dose-dependent effects. Sterile distilled water-treated discs served as negative controls. No chemical positive control was used to allow direct comparison among essential oil treatments. A 5 mm diameter mycelial plug from the margin of an actively growing fungal colony was aseptically placed at the center of each plate. Plates were incubated at 25 ± 1 °C in the dark for 5–7 days, depending on species growth rate. Radial mycelial growth was measured using a ruler or digital caliper, and percentage inhibition was calculated according to Singh et al. [42]:

where: C = average radial growth in the control (mm); T = average radial growth in the treatment (mm)

2.9. Contact Toxicity Effect of Essential Oils Against Maize Weevil

The contact toxicity of L. camara and E. globulus essential oils against Sitophilus zeamais was evaluated using a topical application assay. Measured volumes of essential oil (0.5 mL and 1 mL) were evenly applied to 10 g of sterilized maize grains (w/w) and transferred into sterile Petri dishes. Five adult weevils (5–10 days old) were introduced per dish, and each treatment was replicated three times. Malathion-treated maize served as a positive control, while untreated maize served as a negative control. Mortality was recorded daily over a 10-day exposure period. Weevils were considered dead if no movement was observed when gently probed with a fine needle. The assay allowed assessment of dose-dependent insecticidal effects of essential oils in comparison to conventional chemical control.

2.10. Repellence Assay of Essential Oils Against Maize Weevil

Repellence of the essential oil against Sitophilus zeamais was evaluated using a zone-choice bioassay adapted from established protocols. The assay was performed in 9 cm diameter glass Petri dishes lined with bisected Whatman No. 1 filter paper. One half-disc was uniformly treated with 0.5 mL of essential oil solution at different concentrations (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0% v/v in acetone), while the other half-disc received 0.5 mL of pure acetone to serve as a negative control. Both halves were air-dried at room temperature for 15 min to allow for complete solvent evaporation before being placed adjacently inside the Petri dish. For each concentration, ten unsexed adult S. zeamais (2–3 weeks old) were carefully released at the centre of the dish. The experiment was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions (27 ± 2 °C, 65 ± 5% RH, and 12:12 hrs light:dark photoperiod). The number of insects on each half of the filter paper was recorded at 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 hrs after exposure. The percentage repellence (PR) was calculated for each concentration and exposure time using the following formula:

where Nc = number of insects on the control half and Nt = number of insects on the treated half.

Repellence was further classified into six standard categories (Class 0: 0.01–0.1%, Class I: 0.1–20%, Class II: 20.1–40%, Class III: 40.1–60%, Class IV: 60.1–80%, and Class V: 80.1–100%) to determine the degree of effectiveness. Each treatment was replicated five times, and the mean repellence values were subjected to statistical analysis to assess concentration- and time-dependent effects.

2.11. GC-MS Analysis of Essential Oils

The chemical composition of Lantana camara and Eucalyptus globulus essential oils was determined using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) at the Department of Microbial, Biochemical & Food Biotechnology, University of the Free State, South Africa. Analyses were performed on a Thermo Scientific Trace 1310 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and coupled to a Thermo Scientific ISQ 7000 single quadrupole mass spectrometer. Separation was achieved using an SGE BP5MS capillary column (60 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness). Hydrogen was used as the carrier gas at a constant pressure of 200 kPa. The injector and FID were maintained at 290 °C, the transfer line at 280 °C, and the ion source at 200 °C. The oven program was set at 60 °C (10 min hold), ramped at 5 °C/min to 300 °C, and held for 30 min. The MS was operated in scan mode over the range 45–650 m/z. Instrument control and data acquisition were carried out using Thermo Xcalibur 4.0 software. Essential oil samples were diluted in 1 mL of the extraction solvent prior to analysis. Compounds were identified by comparing the electron ionization mass spectra with those in the NIST 2017 library. Authentic standards were not available for all compounds; therefore, identifications are reported as tentative and are supported by manual evaluation of fragmentation patterns and consistency with previously reported constituents of L. camara [43,44,45] and E. globulus [32,46,47] essential oils. Only constituents present at 1% of the total composition were included, while trace components below this threshold were excluded due to their negligible contribution.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), and differences among treatment means were compared using Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance level of p < 0.05. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

The mean (μ) for each treatment was calculated as: . The mean value, , was calculated using the formula: where N represents the number of plates that make up a specific isolate and is the measured diameter on each plate.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Identification of Fungal Pathogens

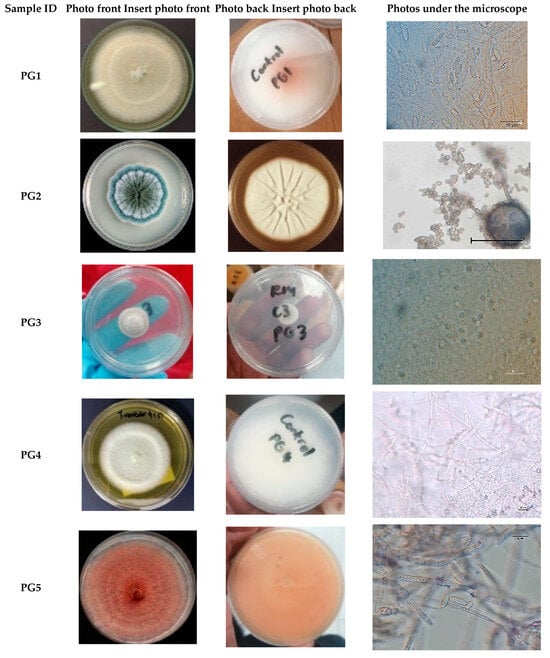

A total of ten fungal isolates (n = 10) were recovered from maize weevils (Sitophilus zeamais) infesting maize (Zea mays), representing diverse genera, including Fusarium, Penicillium, Purpureocillium, Cladosporium, and Trametes. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, the isolates PG1, PG6, PG9, and PG10 displayed white colonies on the frontal surface and orange-white pigmentation on the posterior surface, with filamentous, radially fuzzy margins. PG5, identified as Fusarium, exhibited pink colonies front and back, with septate hyphae, oval spores, and sickle-shaped conidia. PG2 and PG8 formed velvety, green colonies with undulating or lobed margins; microscopic examination revealed aerial hyphae, oval spores, and penicillate conidiophores, confirming Penicillium identification. PG3 presented light purple and white frontal colonies with cream-white posterior surfaces; hyaline, septate hyphae, ellipsoidal spores, and phialides supported classification as Purpureocillium. PG7 produced black-brown filamentous colonies with radial fuzzy margins, containing lemon-shaped spores and shielded conidiophores, consistent with Cladosporium. PG4 exhibited white filamentous colonies with clamp connections and smooth cylindrical spores, lacking conidiophores, and was identified as Trametes. Overall, morphological characterization revealed considerable diversity, with Fusarium being the most prevalent genus among the isolates.

Table 1.

Morphological Identification of Pathogenic Fungi: Macroscopic and Microscopic Characteristics.

Figure 1.

Visual and Microscopic Characterization of Pathogenic Fungi, Including Colony colour.

3.2. Molecular Identification of Fungal Pathogens

Molecular techniques were employed to confirm the identification of fungal isolates by comparing their sequences with those stored in the GenBank database (Table 2). Isolate PG1, PG5, PG6, PG9, and PG10 were all identified as Fusarium solani with the accession number OQ818134.1, demonstrating the abundance of this pathogen among the samples. This highlights F. solani as the dominant species in the sampled environment. Similarly, isolate PG2 was identified as Penicillium brasilinum with the accession number AB455514.2. Further analysis showed that isolate PG3 was Purpureocillium (accession number: MK503783.1). Isolate PG4 was identified as Trametes versicolor (accession number OR250362.1), and isolate PG7 was identified as Cladosporium sp. (accession number OP596126.1). The identification of isolate PG8 as Penicillium sp. (accession number MN788660.1) highlights the presence of another distinct Penicillium species. These findings provide valuable insights into the fungal biodiversity and potential ecological interactions occurring within the sampled environment.

Table 2.

Molecular Identification of fungal communities associated with S. zeamais.

3.3. Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils Against Fungal Pathogens from S. zeamais

The antifungal potential of L. camara and E. globulus essential oils was evaluated against ten fungal isolates obtained from S. zeamais (Table 3). Both oils demonstrated concentration-dependent inhibition, with efficacy increasing at higher concentrations (100–2000 µL/L). Among the isolates, PG5, PG8, and PG10 exhibited higher resistance at lower doses but increased susceptibility at higher concentrations. Several isolates, including PG2, PG3, PG6, and PG7, were highly sensitive to E. globulus essential oil. At the highest concentration (2000 µL/L), inhibition reached up to 93%, with PG3 showing 90% growth suppression. Comparative analysis revealed that E. globulus essential oil consistently outperformed L. camara oil across most concentrations, particularly at 1000 and 2000 µL/L. Both oils demonstrated fungistatic or fungicidal properties, with enhanced inhibitory effects at higher doses. L. camara oil was effective but generally required higher concentrations to achieve inhibition levels comparable to E. globulus, suggesting slightly lower broad-spectrum antifungal activity. Overall, these findings underline the superior efficacy of E. globulus essential oil as a potential biopesticide with both insecticidal and antifungal properties.

Table 3.

Antifungal activity of Eucalyptus globulus and Lantana camara essential oils against pathogenic fungi from S. zeamais.

3.4. Contact Toxicity Effect of Essential Oils Against Maize Weevil

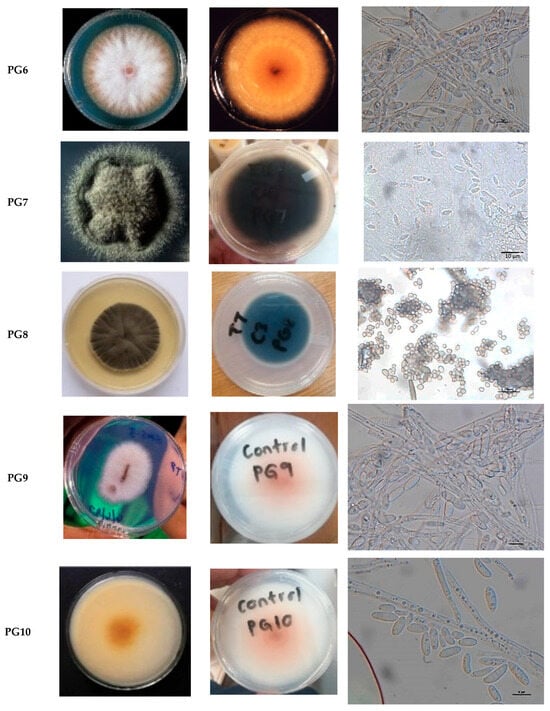

The insecticidal efficacy of E. globulus and L. camara essential oils against Sitophilus zeamais was monitored over a 10-day period (Table 4 and Figure 2). Preliminary results showed that positive control (malathion, 5%) caused immediate and complete mortality, achieving 100% death within 24 hrs. The negative control (distilled water) exhibited no mortality. Both concentrations of E. globulus essential oil (5% and 10%) demonstrated rapid and potent insecticidal effects, achieving complete weevil mortality (100%) within 24 hrs. Mean mortality values were 100 ± 4.5% for the 10% concentration and 100 ± 3.0% for the 5% concentration, suggesting strong toxicity regardless of concentration. In contrast, L. camara essential oil exhibited a concentration-dependent response. At 10%, the oil induced 100 ± 1.2% mortality on Day 1, comparable to both the positive control and E. globulus oil. However, the 5% concentration showed reduced and inconsistent efficacy, with mortality ranging from 20 ± 3.2% on Day 1 to 40 ± 0.2% on Day 6, and zero mortality on several intermediate days. These results indicate that L. camara oil requires threshold concentration to achieve optimal insecticidal activity, whereas E. globulus oil is highly effective even at lower concentrations.

Table 4.

Percentage mean mortality of maize weevils treated with essential oils over 10 days.

Figure 2.

Graph showing contact toxicity of essential oils against maize weevils.

3.5. Repellence Bioassay

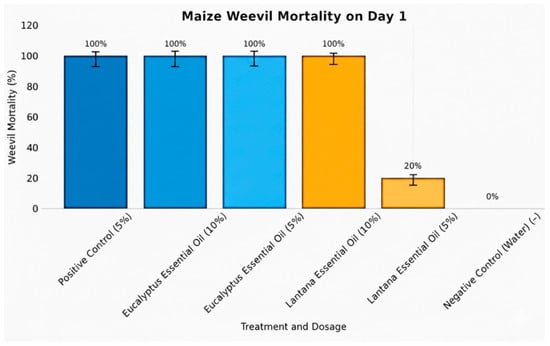

Preliminary results of repellence bioassay revealed clear concentration- and plant species–dependent differences in the behavioral response of S. zeamais adults to essential oil treatments (Table 5 and Figure 3). The positive control (synthetic repellent, 5%) achieved complete repellence (100 ± 2.0%), while no repellence was observed in the negative control (water) throughout the trial (0%). Among the test oils, E. globulus oil exhibited strong and consistent activity at both 10% and 5% concentrations, with mean repellence values exceeding 95% within the first hour of exposure and remaining in repellence Class V (80-100%) for up to 24 h. This demonstrates that E. globulus oil is a highly effective repellent even at moderate dosages. L. camara essential oil also showed high repellence at 10% concentration, producing a repellence level of 100 ± 1.2% on Day 1, consistent with Class V activity. In contrast, the 5% concentration of L. camara oil displayed variable and generally weak effects, with repellence fluctuating between 20 and 40% across observation days and remaining within Classes I–II. Overall, E. globulus oil demonstrated significantly higher and more stable repellence than L. camara oil at equivalent concentrations (p < 0.05). The effect of concentration was also statistically significant (p < 0.001), with higher dosages producing markedly stronger repellence.

Table 5.

Percentage repellence (PR%) and corresponding repellence classes of essential oils against Sitophilus zeamais adults at different time intervals (1–24 h).

Figure 3.

Bar graph showing the repellence (PR%) of essential oils against Sitophilus zeamais across the 1–24 h exposure intervals.

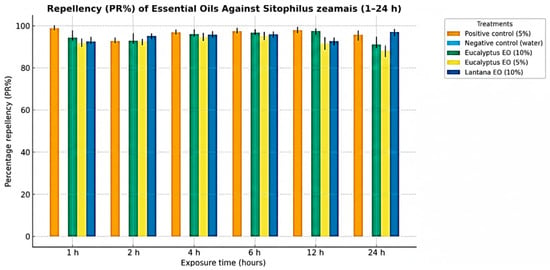

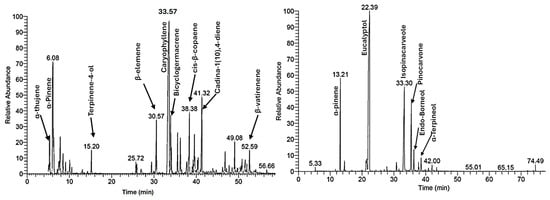

3.6. GC-MS Analysis

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of the essential oils from E. globulus and L. camara species revealed distinct phytochemical profiles, with each oil containing a unique blend of compounds as shown in Figure 4. The chemical compounds with significant abundance (≥1%) identified in the essential oil of L. camara and E. globulus leaves, along with their relative percentages, are presented in Table 6, while a detailed table including their MS fragmentation ions and selected mass spectra is provided in Table S1 and Figures S1–S8 (Supplementary Data). The analysis of L. camara exhibited a sesquiterpene-dominant chemical profile. The most abundant compound was identified as caryophyllene (30.99%), followed by cis-β-copaene (5.02%), cadina-1(10),4-diene (5.92%), bicyclogermacrene (4.11%), and β-elemene (4.08%). The high content of caryophyllene is known to contribute to the oil’s antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties [19]. α-pinene (13.83%) was identified as the most abundant monoterpenes. In contrast, E. globulus oil revealed a cineole-rich chemotype, with eucalyptol (1,8-cineole, 52.77%) as the major constituent. This was found alongside monoterpene hydrocarbon α-pinene (9.09%) and oxygenated monoterpenes isopinocarveole (16.72%) and pinocarvone (10.93%). This composition is consistent with literature reports that consistently identify E. globulus oil as cineole-dominant, typically containing approximately 17–90% eucalyptol [20].

Figure 4.

GC-MS chromatogram of essential oils extracted from L. camara (left) and E. globulus (right) leaves.

Table 6.

Chemical composition of essential oil extracted from L. camara and E. globulus leaves. Only constituents with relative abundance ≥1% are included.

4. Discussion

The present study successfully identified a diverse range of fungal pathogens, including Fusarium, Penicillium, Purpureocillium, Cladosporium, and Trametes, associated with maize weevils (Sitophilus zeamais). The prevalence of Fusarium species, particularly Fusarium solani (isolates PG1, PG5, PG6, PG9, and PG10), as the dominant pathogen is a notable finding. This result is consistent with existing literature, which frequently reports Fusarium species as significant post-harvest pathogens of maize [48,49,50]. In a separate but related discovery, a recent academic paper reported the first-ever isolation of the yeast Hyphopichia burtonii from the storage pest, S. zeamais. This novel finding is significant because the isolated yeast demonstrated strong bioactivity against mycotoxigenic fungi. The isolation suggests that the weevil may serve as a vector for beneficial microorganisms that could be leveraged for the biological control of fungal contamination in stored grains [51]. The molecular identification of all isolates, which confirmed the morphological findings, is crucial, as morphological characteristics alone can sometimes be ambiguous. The identification of PG4 as Trametes versicolor, a white-rot fungus, highlights the unexpected biodiversity associated with the weevil’s ecosystem.

The antifungal potential of the essential oils was also found to be concentration-dependent, with E. globulus oil demonstrating superior broad-spectrum activity compared to L. camara oil. The high level of inhibition observed with E. globulus oil is consistent with numerous studies highlighting the potent fungicidal properties of its major components, eucalyptol and α-Pinene. These compounds are thought to disrupt fungal cell membranes, leading to cell lysis and growth inhibition by increasing membrane permeability [23,52,53]. The observed resistance of certain isolates, such as PG5 (Fusarium solani), PG8 (Penicillium sp.), and PG10 (Fusarium solani), to the essential oils at lower concentrations is a critical finding. The concept of concentration-dependent efficacy is a cornerstone of antifungal research. Numerous studies have established that essential oils often require a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to be effective [54,55]. For instance, research on Eucalyptus camaldulensis essential oil found that while it could inhibit F. solani at lower concentrations, the effectiveness was significantly lower at reduced doses [56]. Similarly, other research has highlighted the variability in resistance among different strains of the same fungal species. This suggests that the genetic and physiological differences between individual strains can influence their susceptibility, a factor that our finding of resistance in specific isolates (PG5, PG8, PG10) strongly supports. On the other hand, Wu et al. demonstrated that Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is the most resistant pathogen to the essential oils tested, while Rhizoctonia solani is the most susceptible. The resistance of S. sclerotiorum is evident from its consistently higher EC50s, while the susceptibility of R. solani is evidenced by its consistently low EC50s across treatments. This aligns with the idea that the essential oils are not universally effective at all concentrations and that certain fungal isolates are better equipped to withstand their effects. The mechanisms behind this resistance are also a topic of extensive study, providing context for the observed results. Fungi can defend against essential oils through several pathways, including having a more robust cell wall, possessing efflux pumps that actively expel the oil’s active compounds, or producing enzymes that metabolize and detoxify the antifungal compounds [57,58,59]. This highlights why the effectiveness of essential oils against fungi is a complex biological interaction. Moreover, it explains why efficacy can vary so widely and why higher concentrations or combinations of essential oils are often required to overcome these cellular-level defences.

The insecticidal activity of both E. globulus and L. camara essential oils against S. zeamais was confirmed to be rapid and potent. The 100% mortality observed within 24 hrs for both Eucalyptus (at 5% and 10%) and L. camara (at 10%) is particularly significant and can be explained by their compositional differences. The immediate and complete mortality from E. globulus oil can be directly linked to its dominant component, eucalyptol (1,8-cineole), a well-documented insecticidal agent against stored-product pests [32,60,61,62]. The fumigant action of eucalyptol is believed to be neurotoxic, affecting the insect’s octopaminergic nervous system, leading to overstimulation, paralysis, and death [18,63,64]. In contrast, the insecticidal effect of the diverse blended L. camara oil is likely due to the synergistic action of its key constituents, caryophyllene and α-Pinene, as well as the minor compounds [65]. These terpenoids possess insect-repellent and toxic properties, also acting as neurotoxins by disrupting the central nervous system [22,66]. The slow concentration-dependent response of L. camara oil, where the 5% concentration was largely ineffective, suggests a minimum threshold is required for its bioactive compounds to exert a lethal effect.

In addition to their insecticidal and antifungal effects, the present study also demonstrated the strong repellence activity of E. globulus and L. camara essential oils against S. zeamais. The repellence bioassay revealed that both concentrations of E. globulus oil (5% and 10%) produced consistent and sustained repellence responses, with percentage repellence values exceeding 95% across all observation intervals. These results place E. globulus oil within repellence Class V, confirming its potency as a behavioral deterrent. The high repellence activity is attributable to the volatility of eucalyptol, which readily disperses in closed storage environments and interferes with the chemosensory mechanisms of insects, thereby discouraging contact with treated substrates. L. camara oil also exhibited strong repellence at 10%, achieving comparable deterrent effects to those of E. globulus oil. However, the 5% concentration displayed inconsistent repellence, fluctuating between Classes I and II. This irregular activity suggests that a threshold concentration is required for the volatiles in L. camara oil to accumulate in sufficient amounts to induce avoidance behaviour. The significantly higher and more stable repellence of E. globulus oil compared to L. camara at equivalent concentrations emphasises its greater utility as a botanical repellent.

Our findings show that a single, cineole-rich Eucalyptus globulus oil achieved rapid weevil mortality and up to 93% inhibition of dominant fungi such as Fusarium solani, outperforming many single-target botanical treatments reported previously [26,28,29,55,67]. This dual efficacy offers a significant management advantage for smallholder grain storage, where fungal contamination and insect infestation typically occur together and chemical fumigants pose health and resistance risks. Integrating such broad-spectrum plant-based biopesticides into post-harvest systems could reduce chemical pesticide reliance while addressing two critical loss pathways: mycotoxin-producing fungi and insect damage in a single, environmentally compatible intervention.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the preliminary results demonstrate that both E. globulus and L. camara essential oils hold significant promise as biopesticides for the management of S. zeamais and its associated fungal pathogens. The two essential oils exhibit distinct chemotypes. While L. camara oil is sesquiterpene-rich, dominated by β-caryophyllene and supplemented by α-pinene and other sesquiterpenes, cineole-rich E. globulus oil contains eucalyptol as major component with significant amounts of isopinocarveole, pinocarvone, and α-pinene. The presence of these components supports the potential antimicrobial and insecticidal activities of the oils. The efficacy of L. camara oil relies on the synergistic interactions of multiple constituents, requiring higher doses to reach toxic thresholds, while the activity of E. globulus is driven by a single dominant compound with rapid action. However, the varying levels of resistance among the fungal isolates highlight the need for further research into the specific mechanisms of action and potential for adaptation. Future studies should focus on the synergistic effects of the oil components and their long-term efficacy in a stored grain environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects17010068/s1, Figures S1–S8: MS spectra for compounds detected in L. camara and E. globulus; Table S1: Retention times, MS ion fragments and identified compounds for L. camara and E. globulus essential oils.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.M. and M.C.M.; methodology, O.J.P. and K.M.; validation, O.J.P., K.M., M.R.M. and M.C.M.; formal analysis, O.J.P.; investigation, O.J.P. and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, O.J.P.; writing—review and editing, M.R.M. and M.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study, including the raw and processed data for insect mortality and fungal inhibition assays, are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. A detailed essential oil chemical composition analysis (quantified constituents, retention times and ion fragments) and selected mass spectra are available in Supplementary Data, Table S1 and Figures S1–S8, respectively.

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to their respective institutes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tefera, M.L.; Carletti, A.; Altea, L.; Rizzu, M.; Migheli, Q.; Seddaiu, G. Land degradation and the upper hand of sustainable agricultural intensification in sub-Saharan Africa-A systematic review. J. Agric. Rural Dev. Trop. Subtrop. (JARTS) 2024, 125, 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Warmate, D.; Onarinde, B.A. Food safety incidents in the red meat industry: A review of foodborne disease outbreaks linked to the consumption of red meat and its products, 1991 to 2021. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 398, 110240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simane, B.; Kapwata, T.; Naidoo, N.; Cissé, G.; Wright, C.Y.; Berhane, K. Ensuring Africa’s Food Security by 2050: The role of population growth, climate-resilient strategies, and putative pathways to resilience. Foods 2025, 14, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngegba, P.M.; Cui, G.; Khalid, M.Z.; Zhong, G. Use of botanical pesticides in agriculture as an alternative to synthetic pesticides. Agriculture 2022, 12, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satya, S.; Kadian, N.; Kaushik, G.; Sharma, U. Impact of chemical pesticides for stored grain protection on environment and human health. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Controlled Atmosphere and Fumigation in Stored Products, New Delhi, India, 7–11 November 2016; pp. 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gossen, B.D.; McDonald, M.R. New technologies could enhance natural biological control and disease management and reduce reliance on synthetic pesticides. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 42, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganai, M.; Khan, Z.; Tabasum, B. Challenges and constraints in chemical pesticide usage and their solution: A review. Int. J. Fauna Biol. Stud. 2018, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Xiao, F.; Ojo, J.; Chao, W.H.; Ahmad, B.; Alam, A.; Abbas, S.; Abdelhafez, M.M.; Rahman, N.; Khan, K.A. Insect resistance to insecticides: Causes, mechanisms, and exploring potential solutions. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 118, e70045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, P.; Banerjee, G. Arms race between insecticide and insecticide resistance and evolution of insect management strategies. In Pesticides in Crop Production: Physiological and Biochemical Action; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ádám, B.; Cocco, P.; Godderis, L. Hazardous effects of pesticides on human health. Toxics 2024, 12, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, S.; Naik, V.K.; Naladi, B.J.; Rathore, A.; Yadav, P.; Lal, D. The Ecological Impact of Pesticides on Non-Target Organisms in Agricultural Ecosystems. Adv. Biores. 2024, 15, 322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, I.; El-Kady, M.M.; Arora, C.; Sundararajan, M.; Maiti, D.; Khan, A. A review on the fatal impact of pesticide toxicity on environment and human health. In Global Climate Change; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 361–391. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, A.; Yaqub, G.; Ayub, M.; Naeem, M. Determination of malathion, chlorpyrifos, λ-cyhalothrin and arsenic in rice. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 41, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Ur-Rashid, M.; Imran, A.B. Biomimetic and Synthetic Advances in Natural Pesticides: Balancing Efficiency and Environmental Safety. J. Chem. 2025, 2025, 1510186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlan, B.; Alkassab, A.T.; Borges, S.; Fisher, T.; Link-Vrabie, C.; McVey, E.; Ortego, L.; Nuti, M. Microbial pesticides: Challenges and future perspectives for non-target organism testing. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, W. Synthetic chemical insecticides: Environmental and agro contaminants. In Microbes for Sustainable Insect Pest Management: An Eco-Friendly Approach-Volume 1; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Teder, T.; Knapp, M. Sublethal effects enhance detrimental impact of insecticides on non-target organisms: A quantitative synthesis in parasitoids. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariadoss, A.; Sujeetha, A.R.; Sankarganesh, E. Challenges and Issues Associated with Chemical Methods of Fumigation. In Non-Chemical Methods for Disinfestation of Stored Products; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 60–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubenova, A.; Georgieva, L.; Antonova, V. Utilization of plant secondary metabolites for plant protection. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2023, 37, 2297533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlak Gajger, I.; Dar, S.A. Plant allelochemicals as sources of insecticides. Insects 2021, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bava, R.; Castagna, F.; Palma, E.; Marrelli, M.; Conforti, F.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Lupia, C.; Ceniti, C.; Tilocca, B. Essential oils for a sustainable control of honeybee varroosis. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Ma, J.; Gao, B. A review of bio-insecticidal activity of essential oils from Asteraceae. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2025, 132, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, F.; Lotfalizadeh, M.; Badpeyma, M.; Shakeri, A.; Soheili, V. From plants to antimicrobials: Natural products against bacterial membranes. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboucha, G.; Rahim, N.; Boulebd, H.; Bramki, A.; Andolfi, A.; Salvatore, M.M.; Masi, M. Chemical composition, in silico investigations and evaluation of antifungal, antibacterial, insecticidal and repellent activities of Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehn. leaf essential oil from ALGERIA. Plants 2024, 13, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, M.K. Insecticidal property of terpenes against maize weevil, Sitophilus zeamais (Motschulsky). J. Biopestic. 2022, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minozzo, M.; da Silva, G.S.; Bernardi, J.L.; do Nascimento, L.H.; Duarte, P.F.; Puton, B.M.S.; Junges, A.; Backes, G.T.; Sausen, T.L.; Steffens, C. Insecticidal Activity of Free and Microencapsulated Cinnamomum cassia Essential Oil Against Sitophilus zeamais in Stored Maize. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 4035–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanna, R.; Bunphan, D.; Kunlanit, B.; Khaengkhan, P.; Khaengkhan, P.; Bozdoğan, H. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil from Apium graveolens L. and Its Biological Activities Against Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky (Coleoptera: Dryophthoridae). Plants 2025, 14, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Isman, M.B.; Tak, J.-H. Insecticidal activity of 28 essential oils and a commercial product containing Cinnamomum cassia bark essential oil against Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky. Insects 2020, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, T.A.; da Silva, A.B.; Farias, L.R.A.; Cruz, G.S.; Teixeira, V.W.; Teixeira, Á.A.C.; de Lima Silva, N.; Trindade, R.C.P. Bioactivity, biochemical mechanisms, and olfactory effects of the essential oil from Syzygium aromaticum and its major compound eugenol on Sitophilus zeamais L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Res. Sq. 2025; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngongo-Kapenga, J.; Kwete, S.M.; Yefile-Mposhi, S.; Kalonji-Mbangila, A.; Mulumba-Badibanga, G.; Ngombo-Nzokwani, A.; Kalonji-Kabemba, N.; Kalala, B.K.; Kalonji-Mbuyi, A.; Muengula-Manyi, M. Use of essential oil of Eucalyptus globulus leaves against Sitophilus zeamais Motsch. Asian J. Biol. 2021, 10, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Guleria, N.; Deeksha, M.G.; Kumari, N.; Kumar, R.; Jha, A.K.; Parmar, N.; Ganguly, P.; de Aguiar Andrade, E.H.; Ferreira, O.O. From an invasive weed to an insecticidal agent: Exploring the potential of Lantana camara in insect management strategies—A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.-Y.; Kwan, Y.-M.; Sathyapriya, H. Utilization of Biodiversity for Sustainable Plant Disease Management. In Advances in Tropical Crop Protection; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Čmiková, N.; Galovičová, L.; Schwarzová, M.; Vukic, M.D.; Vukovic, N.L.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Bakay, L.; Kluz, M.I.; Puchalski, C.; Kačániová, M. Chemical composition and biological activities of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil. Plants 2023, 12, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liambila, R.N.; Wesonga, J.M.; Ngamau, C.N.; Wallyambilla, W. Seasonal and Regional Chemical Variability of the Wild Population of Lantana camara Leaf Essential Oil from Kenya. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 13, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Kato, M. Compounds involved in the invasive characteristics of Lantana camara. Molecules 2025, 30, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routray, S.; Kabi, M.; Debnath, D.; Palei, S. Potential of Lantana camara L. extracts as biopesticide against insect pests. J. Entomol. Res. 2021, 45, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinkela, N.; Morales, A.; Sánchez-Martínez, H.A.; Díaz, M.; Samba, N.; Mawunu, M.; Morán-Pinzón, J.A.; Silva, L.; Rodilla, J.; De León, E.G. Comprehensive Characterization of Lantana camara Essential Oils: GC-MS Profiling, Antioxidant Capacity, and Drug-Likeness Prediction. 2025. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/frontend/manuscript/3dace6650c68805bb4cddf8aa9e23b64/download_pub (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Satyal, P.; Crouch, R.A.; Monzote, L.; Cos, P.; Awadh Ali, N.A.; Alhaj, M.A.; Setzer, W.N. The chemical diversity of Lantana camara: Analyses of essential oil samples from Cuba, Nepal, and Yemen. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atti-Santos, A.C.; Rossato, M.; Serafini, L.A.; Cassel, E.; Moyna, P. Extraction of essential oils from lime (Citrus latifolia Tanaka) by hydrodistillation and supercritical carbon dioxide. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2005, 48, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopane, B.; Tchatchouang, C.K.; Regnier, T.; Ateba, C.; Manganyi, M. Community diversity and stress tolerance of culturable endophytic fungi from black seed (Nigella sativa L.). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 137, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishuba, A.; Leboko, J.; Ateba, C.N.; Manganyi, M.C. First report: Diversity of endophytic fungi possessing antifungal activity isolated from native Kougoed (Sceletium tortuosum L.). Mycobiology 2021, 49, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Pandey, N.; Agnihotri, V.; Singh, K.; Pandey, A. Antioxidant, antimicrobial activity and bioactive compounds of Bergenia ciliata Sternb.: A valuable medicinal herb of Sikkim Himalaya. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedeji, O.; Ekundayo, O.; König, W. Volatile leaf oil constituents of Lantana camara L from Nigeria. Flavour Fragr. J. 2003, 18, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J.; Balcázar, K.; López, J.; Castillo, L.N.; Ortega, R.; López, H.V.; Delgado-Fernández, E.; Vacacela, W.; Calva, J.; Armijos, C. Chemical Composition and Acaricidal Activity of Lantana camara L. Essential Oils Against Rhipicephalus microplus. Plants 2025, 14, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikal, A.; Ali, A.R. Chemical composition and toxicity studies on Lantana camara L. flower essential oil and its in silico binding and pharmacokinetics to superoxide dismutase 1 for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) therapy. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 24250–24264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almas, I.; Innocent, E.; Machumi, F.; Kisinza, W. Chemical composition of essential oils from Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus maculata grown in Tanzania. Sci. Afr. 2021, 12, e00758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (ed. 4.1); Allured Publ Crop: Carol Steam, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.M.; Ameye, M.; Phan, L.T.-K.; Devlieghere, F.; De Saeger, S.; Eeckhout, M.; Audenaert, K. Post-harvest contamination of maize by Fusarium verticillioides and fumonisins linked to traditional harvest and post-harvest practices: A case study of small-holder farms in Vietnam. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 339, 109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deressa, T.; Adugna, G.; Suresh, L.; Bekeko, Z.; Vaughan, M.M.; Iriarte-Broders, G.; Proctor, R.; Mehl, H.; Prasanna, B.M.; Opoku, J. Fusarium species associated with preharvest maize ear rot cause stalk rot disease in Ethiopia. Plant Dis. 2025, 10, 3057–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunino, M.P.; Herrera, J.M.; Pizzolitto, R.P.; Rubinstein, H.R.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Dambolena, J.S. Effect of selected volatiles on two stored pests: The fungus Fusarium verticillioides and the maize weevil Sithophilus zeamais. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7743–7749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seco, M.; Beltran, A.; Balendres, M. First record of Hyphopichia burtonii isolated from the storage pest Sitophilus zeamais and its bioactivity against mycotoxigenic fungi. Hell. Plant Prot. J. 2024, 17, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhantoobi, W.A.; Alkatheri, A.H.; Parusheva, T.; Lai, K.S.; Thomas, W.; Lim, S.-H.E. Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils and Their Mechanism of Action Against Bacterial and Fungal Infections. Saudi J. Biomed. Res. 2025, 10, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Woo, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.B.; Zheng, Y.; Chun, H.S. Antifungal activity of essential oil and plant-derived natural compounds against Aspergillus flavus. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, T.d.S.; Machado, J.C.B.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Soares, L.A.L. Bioactive Plant Compounds as Alternatives Against Antifungal Resistance in the Candida Strains. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Chitrakar, B.; Gu, Z.; Ban, X.; Hong, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, C. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of essential oils against microorganisms: Methods, function, accuracy factors and application. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 3445–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, B.; Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; Altieri, C.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Minimal inhibitory concentrations of thymol and carvacrol: Toward a unified statistical approach to find common trends. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakuubi, M.M.; Maina, A.W.; Wagacha, J.M. Antifungal activity of essential oil of Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. against selected Fusarium spp. Int. J. Microbiol. 2017, 2017, 8761610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-L.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Luo, X.-F.; Li, A.-P.; Zhang, S.-Y.; An, J.-X.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Liu, Y.-Q. Antifungal efficacy of sixty essential oils and mechanism of oregano essential oil against Rhizoctonia solani. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 191, 115975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Saini, R.; Shukla, P.; Tiwari, K. Role of secondary metabolites in plant defense mechanisms: A molecular and biotechnological insights. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 953–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, A.R.; Leite, J.P.V. Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils: Uses and Applications Against Plant Pathogens. In Natural Pesticides and Allelochemicals; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 147–167. [Google Scholar]

- Shala, A.Y.; Gururani, M.A. Phytochemical properties and diverse beneficial roles of Eucalyptus globulus Labill.: A review. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, H.H.; Sara, B.; Benhalima, H.; Benaliouche, F.; Sbartai, I.; Sbartai, H. Chemical characterization of Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) leaf essential oil and evaluation of its antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2024, 70, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammad, F.; Bentoumi, Y.; Gharnaout, M.L.; Zebib, B.; Merah, O. Inhibitory effect of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil against Botryosphaeria dothidea and Fomitiporia mediterranea fungi causing wood diseases in viticulture. Vegetos 2024, 38, 2482–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Kushwaha, A.; Sanju, S.; Spring, P.; Kumar, A.; Misra, P.; Shukla, P.K. Essential oils toxicity and conflicts. In Aromatherapy: The Science of Essential Oils; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2024; pp. 124–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ihssane, G.; Jihane, T.N. Comparative Efficacy of Essential Oils Extracted from the Fruits and Leaves of Eucalyptus globulus in the Control of a Stored-Product. Ph.D. Thesis, Larbi Tébessi University, Tébessa, Algeria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Baouahi, N.; Bouhadi, M.; Elagdi, C.; Hamdane, H.; Yousfi, S.; Bouamrani, M.L.; El Kouali, M.h.; Talbi, M.; Bennani, L. Evaluation, efficacy and function of essential oils from Lantana camara L. Morocco leaves for the antioxidant activity and as a bio-insecticide against the wheat weevil Sitophilus granarius in post-harvest crops. Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2025, 10, 3821–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laoudi, T.; Khelfane-Goucem, K.; Hamani-Aoudjit, S.; Chebrouk, F.; Amrouche, T.; Saher, L.; Kellouche, A. Chemical composition of essential oils from the leaves of Schinus molle and Cupressus sempervirens and their insecticidal activity against Oryzaephilus surinamensis (Coleoptera: Silvanidae). J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2023, 26, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.