Simple Summary

Neonicotinoids are a type of insecticide that were once considered safer for the environment than other pesticides. But recent research shows that even very small, non-lethal amounts of these chemicals can harm insects that provide ecosystem services—like bees that pollinate crops, insects that eat pests, and species that help break down dead plants and animals. These insecticides linger in soil and plants for long periods, causing changes in how insects move, smell, reproduce, and behave. Over time, this can disrupt entire food webs and weaken important natural processes that keep ecosystems healthy. To protect biodiversity and ensure sustainable farming, it is important to understand how low levels of pesticides can impact beneficial insects. Future research should focus on developing better pest control solutions that do not negatively affect the insects we rely on.

Abstract

Neonicotinoid insecticides were initially hailed as safer alternatives to organochlorine and organophosphate pesticides due to their perceived lower toxicity to non-target organisms. However, it has been recently discovered that sublethal exposure to neonicotinoids negatively affects beneficial arthropods that are essential for a functional ecosystem. These beneficial arthropods include pollinators, biological control agents, and decomposers. This review synthesizes current research on the physiological, behavioral, and reproductive consequences of neonicotinoids on non-target arthropods and their broader ecological impact. The chemical and physical properties of neonicotinoids raise concerns about long-term ecological consequences of neonicotinoid use because these chemicals are persistent in plants and soil, which contributes to prolonged exposure risks for organisms. Sublethal doses of neonicotinoids can disrupt the ecological services provided by these organisms by impairing essential biological processes including motor function, odor detection, development, and reproduction in insects, while also altering behavior such as foraging, mating, and nesting. Furthermore, neonicotinoid exposure can alter community structure, disrupting trophic interactions and food web stability. Recognizing the sublethal impacts of neonicotinoids is critical for the development of more sustainable pest management strategies. It is imperative that future research investigates the underlying mechanisms of sublethal toxicity and identifies safer, more effective approaches to neonicotinoid-based pest control to mitigate adverse ecological effects. Incorporating this knowledge into future environmental risk assessments will be essential for protecting biodiversity and maintaining ecosystem functionality.

1. Introduction

Neonicotinoid insecticides were developed to address concerns about the high toxicity of organochlorine and organophosphate pesticides on non-target organisms, and they became widely used in urban and agricultural systems during the 1990s [1]. Neonicotinoids are now the most widely used class of insecticides globally, accounting for over 20% of the market, due to their systemic movement within plants, extended residual activity, and broad-spectrum insecticidal properties, despite recognized toxicity to non-target organisms [2,3,4,5,6]. The sublethal effects of neonicotinoids on beneficial and non-target organisms have raised increasing concerns despite their efficacy at controlling herbivorous pests [7,8,9,10]. Existing research has largely focused on the lethal effects of neonicotinoids and therefore significant gaps remain in understanding their sublethal impacts on non-target insects.

Neonicotinoids are absorbed and move systemically within plants. This mode of action exposes the targeted herbivorous pests and other organisms throughout the food web [9]. The impacts of insecticides are broadly categorized as lethal or sublethal. Lethal insecticide effects arise from any exposure that causes death in an individual or population, whereas sublethal effects occur from any survivable exposure that alters an organism’s biology, physiology, or behavior [11]. These sublethal effects can contribute to the global decline of insects by profoundly influencing organismal, population, and community dynamics. Global declines in insects disrupt ecosystem processes and reduce overall productivity of cropping systems [12].

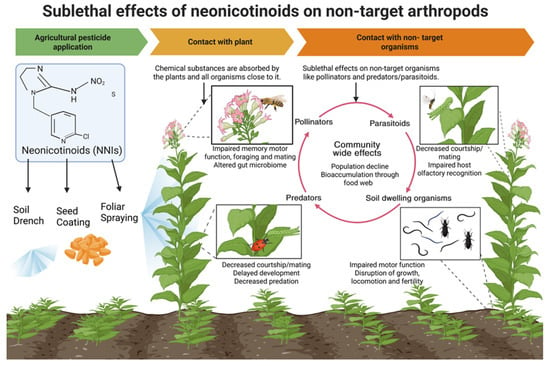

This review synthesizes evidence on the sublethal effects of neonicotinoids on beneficial insects and explores how these impacts propagate to key ecosystem services, including pollination, biological pest control, and biodiversity maintenance, discussing ecological consequences that are often overlooked. Exposure to sublethal doses of neonicotinoids can impair the physiology and alter the behavior of these non-target organisms and disrupt the critical ecological services they provide (Figure 1, Table 1). Beneficial insects such as pollinators and biological control agents provide ecosystem services valued at approximately US $57 billion per year to in the United States [13]. This review first examines the pathways through which neonicotinoids reach non-target arthropods in the environment. It then delves into the sublethal impacts on key physiological and behavioral traits, including development, motor functions, reproduction, olfactory responses, foraging behavior, and social interactions. Finally, we discuss how these sublethal effects cascade through ecological communities, diminishing essential services and processes that support ecosystem stability and productivity. We emphasize the urgent need to better understand the various routes of exposure to neonicotinoids and their impacts on the physiology and ecology of nontarget organisms by synthesizing existing literature and identifying critical research gaps. This knowledge should be incorporated into future environmental risk assessments to protect biodiversity and maintain ecosystem functionality.

Figure 1.

Effects of neonicotinoids though food web in agroecosystem and adjacent habitats. Image created in BioRender [14].

Table 1.

Summary of the sublethal effects of neonicotinoids on non-target arthropod physiology, reproduction, behavior, and community dynamics. Detailed information on tested dosages is provided in Table S1.

2. How Do Neonicotinoids Reach Non-Target Organisms

Pesticide exposure routes of non-target organisms, including beneficial predators and pollinators, have changed over time with the adoption of different application strategies. For example, foliar sprays and broadcast treatments have exposed many non-target organisms to high levels of aerial drift. Neonicotinoids applied as seed coatings were developed to increase systemic uptake into plant vascular tissues and reduce airborne exposure for many non-target organisms. However, while these formulations lower the risk of aerial contamination, they significantly increase the likelihood of neonicotinoids leaching into soil and accumulating in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems [109]. Their physicochemical properties—high water solubility, mobility in soil, and low soil adsorption—facilitate their persistence and movement in the environment [110,111]. It estimated that target plants absorb only a small fraction, 2 to 20%, of the applied neonicotinoids [109]. The remaining 80 to 98% leaches into soil and aquatic ecosystems, where it can persist for up to 8 months [112]. Neonicotinoids exhibit extensive environmental persistence, driven by their ability to propagate through ecosystems, as residues from seed-treated plants can be absorbed by untreated cover crops [113]. Seed coatings and granule formulations reduce aerial exposure but simultaneously facilitate persistent contamination through soil and water, complicating efforts to evaluate their ecological safety [114]. Plant-associated arthropods, like pollinators and omnivorous insects, get exposed to neonicotinoid accumulations in various plant products, including pollen, floral and extra-floral nectar, and guttation droplets [115,116]. Additionally, natural enemies, predators, and parasitoids exposed to nectar and pollen containing neonicotinoids decreased prey consumption, female reproduction, foraging success, mobility, survivorship, and altered sex ratios compared to unexposed controls [57,100,107,117]. Natural enemies are exposed to neonicotinoids not only through feeding on contaminated prey but also by interacting with treated plants, which many carnivorous arthropods use for shelter, supplemental feeding, or while searching for mates [72]. For example, the survival of Anagyrus pseudococci parasitoids was reduced after parasitizing the citrus mealybug Planococcus citri that fed on neonicotinoid-treated citrus plants compared to control citrus plants [105]. While the high absorbance of neonicotinoids by plants may reduce direct exposure to non-target organisms, it presents a persistent sublethal risk to insects interacting with plants or consuming contaminated prey.

3. Physiological Effects

Neonicotinoids share a similar mode of action across all insects. Neonicotinoids exhibit higher potency and selectivity compared to their naturally occurring analog, nicotine [118]. They function by binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which are agonist-gated ion channels responsible for rapid excitatory neurotransmission in the central nervous system [119]. Binding of neonicotinoids to nAChRs facilitates the accumulation of acetylcholine in the insect nervous system and an influx of calcium ions to the brain [120,121]. At lethal doses, this acetylcholine buildup results in paralysis and death [120,122]. At sublethal doses, however, this buildup affects insect movement, cellular processes, development, and reproduction [15,51,52,83]. Neonicotinoids have the added dimension of time-cumulative toxicity, in which sublethal effects may continue until the repeated doses cause a critical level of neuronal damage or death in the insect [123]. Neonicotinoids significantly impair the motor function of insects exposed to sublethal concentrations, with the mechanisms and severity varying across species [15,22,30,124]. In bees, exposure to neonicotinoid residues disrupted motor functions, reducing flight duration, impairing righting reflexes, inducing repeated circular movements, and increasing grooming behaviors [15,18,22,23,26,125]. Exposed bees also exhibited knockdown, trembling, erratic movements, heightened activity, and tremor following neonicotinoid exposure [16,19,21,28]. These pesticides also impair the movement and foraging ability of the predatory beetles Harpalus pennsylvanicus, with these effects persisting for several days post-exposure [30]. Short-term hypermobility occurred in the predatory beetle Platynus assimilis and the decomposer burying beetle Nicrophorus americanus, and reduced feeding arose in multiple predatory carabid species after exposure [31,32,84].

Reduced movement in insects has primarily been linked to the binding of neonicotinoids to insect nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). Sublethal imidacloprid, clothianidin, and thiamethoxam exposures alter nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunit expression in bees and other insects, and different receptor subtypes show variable binding affinity [126]. These exposures also modulate the transcription of genes involved in immunity, stress responses, and neural plasticity, including increased expression of the multifunctional gene vitellogenin and downregulation of creb and pka, which are linked to long-term memory [36]. However, the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor Rdl (resistant to dieldrin) has been proposed as a secondary target for neonicotinoids, demonstrating the complexity of their neurotoxic effects [127]. Acetylcholine and γ-aminobutyric acid also regulate critical biological processes, many of which are disrupted by neonicotinoids [48,128]. These processes include circadian rhythm regulation, sleep, memory, and olfactory learning in insects [41,47,128,129]. Honeybees Apis spp. exhibited decreased olfactory memory and learning ability after larval exposure to neonicotinoids [42,130,131]. Sublethal doses of imidacloprid damaged memory formation in the mushroom bodies, which are key regions of the insect brain involved in short- and medium-term memory [40]. Damselfly larvae Lestes congener exposed to neonicotinoids similarly demonstrated a decrease in learned recognition toward predatory fish odor cues [46]. Neonicotinoids’ ability to spontaneously bind to various neurotransmitter receptors in the insect nervous system further exacerbates their detrimental effects, impairing multiple physiological and behavioral processes critical for survival.

Sustained binding of neonicotinoids causes cellular damage from oxidative stress. Neonicotinoid binding to nAChRs opens ion channels but also prevents channel closure by inhibiting hydrolysis by acetylcholinesterase. Calcium ions flood neurons and activate enzymes that increase reactive oxygen species (ROS). Fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster larvae exposed to imidacloprid exhibited increased ROS, which lowered ATP production and reduced activity of mitochondrial enzymes [121]. Similarly, aquatic midge Chironomus dilutus and honeybee Apis mellifera experienced swelling and degeneration of the mitochondrial matrix in imidacloprid-exposed cells [35,39]. Oxidative stress from neonicotinoids resulted in nervous system damage and loss of energy production in both insects. Stress led to downregulation of creb and pka proteins linked to memory and learning [36,39]. This cellular damage may explain the diminished mobility and impaired learning seen in neonicotinoid-treated arthropods. Increases in anti-apoptotic proteins further demonstrates cellular damage from stress. Heat shock proteins (HSP70), which prevent cell death, were upregulated in adult stingless bee Melipona scutellaris after thiamethoxam exposure [37]. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST), a detoxification enzyme, similarly increased in the stingless bee Scaptotrigona postica and silk moth Bombyx mori after neonicotinoid exposure [38,132].

Neonicotinoids also exhibit a hormetic effect, a phenomenon in which low doses of an environmental agent, such as an insecticide, elicit stimulatory or seemingly beneficial effects [133]. For instance, residual low doses of neonicotinoids enhanced reproduction in the spined soldier bug Podisus maculiventris [55] and improved host-finding behaviors in the whitefly parasitoid Encarsia formosa [58,134]. In bumblebees, neonicotinoid exposure initially increased the speed of foraging learning but ultimately reduced long-term foraging efficiency [68]. This initial improvement may arise from certain bees’ preference for neonicotinoid-treated sucrose solution, since the bumblebee Bombus terrestris consumed more and traveled to neonicotinoid feeders even after feeder relocation [65]. Bumblebees preferred neonicotinoid-treated sucrose in a two-choice bioassay, despite neonicotinoids reducing their overall consumption and the adverse effects on their overall performance and health [9,64]. The hormetic effect raises significant concerns about prolonged exposure, as foraging insects may actively seek out neonicotinoid-treated food sources, inadvertently increasing their risk of sublethal impairments.

Sublethal doses of neonicotinoids significantly impact neural activity in various insect species altering sensory detection and behavior [44,135]. Tatarko et al. [135] investigated the effects of different imidacloprid concentrations on fruit fly D. melanogaster behavior and electrophysiological antennal responses. They found that sublethal imidacloprid exposure reduced activity in a single olfactory sensory neuron and delayed the recovery of the antennal response to baseline levels. Moreover, neonicotinoids also can impair other sensory systems. For instance, insecticide exposure reduced visual motion detection and decreased neuronal conduction in axons in the migratory locust Locusta migratoria [136]. Similarly, neonicotinoid doses increased honeybee Apis mellifera antennal responses to floral odors and queen pheromones, but expedited signal degeneration to floral odors [74]. While electroantennograms provide critical insights into olfactory disruptions caused by neonicotinoids, alternative mechanisms, such as brain dysfunction, may also be involved. Reduced learning performance and responsiveness in bumblebees and honeybees exposed to sublethal doses of neonicotinoids have been linked to reduced brain growth and altered gene expression [17,43]. However, sensory effects can vary among insect species. For example, sublethal doses of imidacloprid impaired both odor and color detection of the pollinating paper wasp Polistes fuscatus [45], but only damaged floral volatile odor detection in the bumblebee Bombus impatiens with no impact on color detection [44]. This finding highlights the species-specific nature of neonicotinoid impacts on sensory systems and underscores the potential for sublethal exposure to disrupt key ecological processes. For bumblebees, the inability to recognize floral volatiles may hinder efficient foraging, as scent cues are vital for locating nectar and pollen sources. Such impairments could reduce resource intake, reproductive success, and pollination efficiency. Furthermore, this sensory disruption may shift plant–pollinator interactions, favoring plants with more visually prominent cues while disadvantaging those reliant on olfactory signals.

Sublethal neonicotinoid exposure interferes with the development of beneficial insects. Low doses of neonicotinoids delayed the developmental time between larval instars and pupation in the coccinellid seven-spotted lady beetle, Coccinella septempunctata [52]. Similar effects have been observed in predatory lacewings Chrysopa pallens, bumblebee Bombus terrestris, and honeybee Apis mellifera larvae, which exhibited prolonged larval and pupal development times following neonicotinoid exposure [49,53,126]. In stingless bee Scaptotrigona aff. depilis, pupal development was prolonged while larval development was shortened, resulting in asymmetric adults [50]. Even invertebrates without larval stages, such as nematodes Caenorhabditis elegans, experienced delayed growth and reduced mobility after exposure to imidacloprid [34].

Recent studies have shown that some insects can detoxify or sequester these neonicotinoids. For example, monarch butterflies can tolerate high concentrations of neonicotinoids because their detoxification pathways have evolved to detoxify cardenolides from milkweed [137]. However, detoxification does not always eliminate the toxic effects, as neonicotinoid metabolites can be just as toxic, or even more so, than the parent compounds [136]. Furthermore, the energy cost of detoxification and sequestration mechanisms could result in physiological costs, leading to long-term population decline despite detoxification.

4. Behavioral Effects

As detailed in the previous section, sublethal doses of neonicotinoids affect the central nervous systems of insects, thereby disrupting behaviors critical for survival and reproduction. These disrupted behaviors include foraging, mating, and nesting. The ability of insects to efficiently search for food and shelter is fundamental to their survival. Neonicotinoids targeting herbivorous pests may cause long-term declines in pollinators foraging on treated crops [138]. A growing body of research has investigated how sublethal exposure to neonicotinoids alters nest-founding and foraging behavior in important pollinators [60,66,67,139]. For instance, bumblebee queens exposed to neonicotinoids exhibited delayed nesting behavior, while workers exposed to neonicotinoids were less likely to initiate foraging and nectar feeding [67]. A study in honeybees investigating the effects of two neonicotinoid insecticides, imidacloprid and clothianidin, revealed significant impacts on foraging-trip behavior [61]. While the results varied in a dose-dependent manner, exposure to both insecticides reduced mobility and induced a motionless phase at higher imidacloprid concentrations. Bees displayed abnormal behaviors such as arching their abdomens, flipping upside down, and paddling their legs while lying on their backs at higher concentrations of clothianidin [61]. The functional roles and ecosystem services of pollinators are jeopardized by the significant sublethal effects of neonicotinoids [61].

Sublethal effects of neonicotinoids vary substantially across social insect species. Some colonies exhibited marked behavioral impairments while others appeared relatively unaffected [20,62,63]. Honeybee colonies, for example, often experienced disrupted foraging efficiency and impaired communication due to interference with the waggle dance—a critical behavior used to convey spatial information about food sources. Such disruptions compromise individual foraging success, weaken overall colony cohesion, and reduce the fitness, survival, and reproduction of entire colonies [20,62,63]. Furthermore, stingless bee Melipona quadrifascitata displayed fewer social communication behaviors like antennation and trophallaxis after acetamiprid ingestion [71]. In contrast, the southern ant Monomorium antarcticum did not display significant sublethal effects on their foraging behavior under comparable neonicotinoid exposure. These divergent outcomes likely stem from fundamental differences in communication and foraging strategies. While social bees integrate both chemical signals and ritualistic behaviors like waggle dancing and trophallaxis, ants rely primarily on pheromone-based chemical communication [76,140]. These ecological and behavioral distinctions may mediate species-specific vulnerability to neonicotinoids. By demonstrating this variability, current findings challenge generalized assumptions about the colony-level effects of neonicotinoids and highlight the importance of species-specific approaches in ecological risk assessment. Evaluating pesticide impacts through a comparative behavioral lens will improve our ability to predict and mitigate risks across diverse taxa of social insects.

Although neonicotinoids did not significantly alter foraging behavior in eusocial ants, these insecticides reduced aggressiveness, thus shifting the outcomes of interspecific interactions such as competition. For instance, Monomorium antarcticum exhibited reduced aggressive behaviors—such as biting, spraying acid, and fighting—during encounters with the invasive ants Linepithema humile when exposed to imidacloprid. This decline in aggression led to reduced brood numbers and colony size, potentially compromising M. antarcticum’s competitive ability against invasive species [76,102]. Similarly, it has been observed that imidacloprid exposure decreased the survival of Lasius flavus workers by reducing avoidance behavior and increasing aggression toward co-occurring Lasius niger ants [75]. Notably, untreated L. niger ants responded with increased aggression toward imidacloprid-treated L. flavus, further exacerbating competitive interaction disruptions [75]. These findings suggest that sublethal neonicotinoid exposure can alter interspecific aggression and colony dynamics in social insects, highlighting broader ecological consequences that extend beyond individual-level effects. Sublethal neonicotinoid exposure also reduces the foraging behavior of solitary predaceous arthropods, often resulting in decreased predation rate or prolonged handling times [85,86,88]. For instance, offspring of the seven-spotted lady beetle Coccinella septempunctata exhibited reduced aphid prey predation when their parents were treated with thiamethoxam at LC10 [79]. Similarly, sublethal doses of thiacloprid reduced the time the hemipteran predator Macrolophus pygmaeus spent feeding, while increasing the time it spent resting and preening on treated plants [85]. Similarly, the predaceous beetle Serangium japonicum decreased prey attacks and increased prey handling time when foraging on plants treated with thiamethoxam [81]. Adult green lacewing Chrysoperla sinica exhibited reduced predation rates when exposed to sublethal doses of imidacloprid [86]. Other predaceous arthropods, such as Pardosa and Linyphiidae spiders, experienced both direct and indirect effects of neonicotinoid exposure. The predatory behavior of Linyphiidae spiders was reduced because sublethal topical doses of neonicotinoids resulted in temporary paralysis [88]. In contrast, Pardosa spiders killed the prey treated with neonicotinoids but avoided consuming them. This led to a waste of energy spent on hunting without a nutritional payoff [87].

Neonicotinoids can also disrupt the ability of parasitoids to locate and parasitize hosts. Female wasps Microplitis croceipes that consumed imidacloprid-treated nectar exhibited reduced ability to locate a host-damaged plant in a wind tunnel, indicating impaired olfactory function [72]. Similarly, in a two-choice olfactometer, female parasitoid wasps Nasonia vitripennis treated with sublethal doses of imidacloprid showed a reduced attraction to host pupae compared to the control group, further suggesting that neonicotinoids disrupt insect olfaction [69,70]. In addition, under laboratory conditions, Psix saccharicola and Trissolcus semistriatus parasitoid wasps displayed lower attack rates and prolonged handling times when parasitizing hemipteran host eggs following exposure to sublethal doses of thiamethoxam and lambda-cyhalothrin [77,78].

Essential ecosystem services, including pollination, biological control, and nutrient cycling, depend on complex behavioral processes that mediate interactions among organisms [13]. Many of these behaviors, such as foraging, host or prey location, and plant-pollinator communication, are chemically mediated and rely on accurate stimulus detection. Sublethal neonicotinoid exposure disrupts these chemically mediated behaviors in both social and solitary insects, impairing foraging efficiency, host-seeking, and sensory processing [67,72,73,81]. Such behavioral changes can cascade through the ecosystem, reducing predation rates, altering predator–prey dynamics, and interfering with pollinator efficiency. Neonicotinoids may further exacerbate these impacts by impairing essential colony-level behaviors, including communication, aggression, and escape responses in social insects [61,141]. Although responses are often species-specific [20,27,76], the consistent pattern of behavioral impairment across functional groups underscores the broad ecological risks posed by neonicotinoids. Understanding and mitigating these sublethal effects is therefore critical for preserving biodiversity and maintaining ecosystem resilience, especially considering the central role of behavior in regulating ecosystem processes [142,143].

5. Reproductive Effects

Mating and reproductive output drive population growth [70,97]. Sublethal neurotoxic effects of neonicotinoids can alter key reproductive processes, including mate-searching behavior, detecting mating pheromones, and courtship behaviors [69,70,91]. These disruptions impair individuals’ ability to locate and respond to potential mates, thereby accelerating population declines. In social insects, whose colony success depends heavily on reproductive health, these effects are especially severe [96,97]. Sublethal neonicotinoid exposure compromised honeybee colony health because exposed Apis mellifera queens had reduced sperm storage, enlarged ovaries, and decreased egg-laying rates [90]. Additionally, the genetic diversity and resilience of the colony was reduced because exposed queens mated less frequently [89]. Reproductive success in annual social bees, such as the bumblebee Bombus terrestris, depends on the production of new queens and males. Colonies exposed to imidacloprid showed an 85% reduction in queen production [95]. Sulfoxaflor exposure similarly reduced the number of reproductive workers and queens [49]. Sublethal doses of thiamethoxam impaired male fertility, resulting in 50% fewer viable sperm in mated queens compared to controls [93]. Neonicotinoid-induced neurological impairments may also reduce feeding efficiency, further constraining reproductive output [96]. These effects are not limited to bees. Sublethal neonicotinoid exposure in ants reduced queen fecundity, colony survival, and worker function [144,145,146]. Neonicotinoids undermine the sustainability of insect populations by interfering with reproductive systems, altering reproductive caste production, and reducing offspring viability. Together, these findings demonstrate that sublethal neonicotinoid exposure undermines insect population sustainability by disrupting reproductive systems, altering reproductive caste dynamics, and reducing offspring viability.

Neonicotinoids can also negatively impact insect reproduction by interfering with detection of and response to sex pheromones, preventing mate-finding and hindering courtship behaviors. Male Nasonia vitripennis parasitoid wasps exposed to sublethal doses of imidacloprid exhibited reduced courtship behaviors such as head-nodding and mounting. Additionally, response rates to male-produced sex pheromones were reduced in exposed females compared to control females [69,70]. Mating success declined more sharply in imidacloprid-treated males compared to treated females. Mating success plummeted by 80% when both sexes were exposed [69,70]. Male parasitoid wasps Spalangia endius displayed consistent courtship behaviors towards both exposed and unexposed females, but unexposed control females primarily mated with males, and exposed females were unreceptive. In contrast, females presented with exposed males and unexposed males were unlikely experience any courtship behavior from the exposed male, suggesting sex-specific responses to neonicotinoids [91]. Predators also displayed varied responses to sublethal neonicotinoid exposure. Exposure to low doses of neonicotinoids did not impact oviposition, fertility, or survival in the soldier bug Podisus maculiventris [55]. The Asian lady beetle, Harmonia axyridis, experienced more severe consequences, including negative transgenerational effects in reproduction following larval exposure [83]. In invertebrates, the fertility of Caenorhabditis elegans nematodes was reduced following sublethal exposure to neonicotinoids [34]. Courtship and mating behaviors of exposed male Pardosa spiders were decreased compared to control spiders [92]. In summary, neonicotinoids may impair reproduction success through various mechanisms, including disrupting pheromone communication, damaging sexual organs, or altering mating behaviors. These disruptions can lower reproductive output, alter the balance of sexual castes, and ultimately suppress population growth, with far-reaching consequences for insect biodiversity and conservation.

6. Community-Wide Effects

The widespread use of neonicotinoids has been suggested as a major driver of the global insect decline [147]. Given that insects comprise approximately 50% of biodiversity within ecological communities [148,149], their decline disrupts ecological interactions and destabilizes ecosystems [150]. A meta-analysis of 44 field and laboratory studies concluded that neonicotinoids negatively impacted multiple functional groups of non-target arthropods, including pollinators, predators, parasitoids, omnivores and detritivores [8]. These widespread effects extended beyond direct toxicity, disrupting species interactions and triggering cascading effects throughout food webs [151]. This impact was not only restricted to agroecosystems but was also observed in organic farms and natural habitats adjacent to neonicotinoids application sites [152]. Reduced prey availability limits food resources for higher trophic levels. Consequently, prey populations are released from top-down control, weakening biological control [151].

Neonicotinoids move through trophic levels and bioaccumulate in food webs despite being water-soluble and typically excreted by animals. For instance, accumulation of neonicotinoids in earthworms and slugs paralyzed predatory arthropods such as ground beetles [108,153]. Whiteflies feeding on neonicotinoid-treated tomato plants excreted unmetabolized residues in their honeydew, inadvertently creating a secondary contamination pathway that can expose beneficial arthropods and other honeydew-feeding organisms [106]. Sublethal neonicotinoid exposures altered community composition of soil-dwelling insect communities [29,99,102]. Additionally, neonicotinoid contamination was linked to declines in aquatic insect biodiversity and ecosystem function [154,155,156,157]. For example, increased neonicotinoid concentrations significantly reduced the abundance and biomass of key aquatic insect orders including Coleoptera, Diptera, Ephemeroptera, Odonata, and Trichoptera [158]. These findings demonstrate that neonicotinoids disrupt multiple ecological communities by altering trophic interactions.

These studies collectively highlight the far-reaching consequences of neonicotinoid exposure across multiple ecosystems. Although several studies have documented the direct toxic effects on individual species, the broader ecological disruptions, such as altered species interactions and cascading effects through food webs, remain understudied. In particular, the long-term implications for ecosystem services, stability, and functioning remain poorly understood. Ongoing biodiversity loss across trophic levels threatens to trigger profound and potentially irreversible ecological consequences.

7. Concluding Remarks

We examined the empirical evidence on the sublethal effects of neonicotinoids on the physiology, behavior, reproduction, and ecology of non-target arthropods in this review (Table 1, Table S1). The chemical properties of neonicotinoids contribute to their persistence in plants and soil, extending the exposure risk for non-target organisms. These sublethal effects can drive chronic declines of beneficial insects, leading to secondary pest outbreaks and biodiversity loss [158,159]. Declines in pollinators and natural enemies can also result in significant economic and ecological losses. Further research is needed to understand how neonicotinoids affect plant physiology, particularly plant defenses [160,161], as these changes can alter plant–insect interactions and propagate throughout the food web [151]. Importantly, major gaps remain in our understanding of multiple routes through which non-target arthropods are exposed to neonicotinoids, including contaminated nectar and pollen, guttation droplets, soil and leaf litter contact, prey-mediated transfer, and trophic cascades. These pathways determine not only the magnitude of exposure but also the likelihood that sublethal effects accumulate across life stages and trophic levels. Advancing mechanistic knowledge of both exposure routes and arthropod responses will be critical for predicting how sublethal effects spread through ecosystems. Despite mounting evidence of these impacts, long-term consequences of chronic, low-dose exposure on ecological interactions and ecosystems functioning remain poorly understood and should be prioritized in future research. Identifying the mechanisms of sublethal toxicity is crucial for guiding the development of safer insecticides and revising regulatory policies to mitigate their ecological side effects.

The ecological impact of neonicotinoids is often compounded by other stressors, including climate change and pathogen outbreaks. These combined pressures underscore the urgency of understanding how neonicotinoids contribute to biodiversity loss and ecosystem instability. Research on community-level responses remains limited, hampering our ability to predict disruptions to ecological networks and essential ecosystem services. Future studies should integrate long-term field data and experimental approaches to evaluate cascading effects across trophic levels. Advancing our understanding of these dynamics is critical for designing sustainable pest management strategies that reduce unintended environmental harm.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects17010026/s1, Table S1: Compilation of studies reporting sublethal effects of neonicotinoids on insect physiology, behavior, reproduction, and community interactions, with associated insect taxa, neonicotinoid compounds, and exposure doses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.K.S., S.A.M.A., A.E. and M.F.K.-B.; Bibliography search, S.K.S., S.A.M.A., F.A.M., A.E., M.S.W. and M.F.K.-B.; Resources, M.S.W. and M.F.K.-B.; Summary Table preparation, S.K.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.K.S., S.A.M.A., A.E. and M.F.K.-B.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.K.S., S.A.M.A., F.A.M., A.E., M.S.W. and M.F.K.-B.; Visualization, F.A.M. and A.E.; Supervision, M.F.K.-B.; Funding, M.S.W. and M.F.K.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the department of Entomology at the Pennsylvania State University. This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Hatch Appropriations under Project #PEN04923 and Accession #7006440, USDA multi-state project #PEN04757, USDA-Applied Research and Development Program #2025-70006-45152, and USDA-NIFA-SCRI Grant #2023-51181-41162.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Stokes Aker for his early contributions to this review. We also thank the Academic Editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seifert, J. Neonicotinoids. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, P.; Nauen, R.; Schindler, M.; Elbert, A. Overview of the Status and Global Strategy for Neonicotinoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2897–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D. REVIEW: An Overview of the Environmental Risks Posed by Neonicotinoid Insecticides. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Delso, N.; Amaral-Rogers, V.; Belzunces, L.P.; Bonmatin, J.M.; Chagnon, M.; Downs, C.; Furlan, L.; Gibbons, D.W.; Giorio, C.; Girolami, V.; et al. Systemic Insecticides (Neonicotinoids and Fipronil): Trends, Uses, Mode of Action and Metabolites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, T.J.; Goulson, D. The Environmental Risks of Neonicotinoid Pesticides: A Review of the Evidence Post 2013. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 17285–17325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todey, S.A.; Fallon, A.M.; Arnold, W.A. Neonicotinoid Insecticide Hydrolysis and Photolysis: Rates and Residual Toxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbert, A.; Haas, M.; Springer, B.; Thielert, W.; Nauen, R. Applied Aspects of Neonicotinoid Uses in Crop Protection. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.R.; Webb, E.B.; Goyne, K.W.; Mengel, D. Neonicotinoid Insecticides Negatively Affect Performance Measures of Non-target Terrestrial Arthropods: A Meta-analysis. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladik, M.L.; Main, A.R.; Goulson, D. Environmental Risks and Challenges Associated with Neonicotinoid Insecticides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3329–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Chen, K.H.C.; Huang, J.C.; Lai, H.T.; Uapipatanakul, B.; Roldan, M.J.M.; Macabeo, A.P.G.; Ger, T.R.; Hsiao, C.D. Physiological Effects of Neonicotinoid Insecticides on Non-Target Aquatic Animals—An Updated Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de França, S.M.; Breda, M.O.; Barbosa, D.R.S.; Araujo, A.M.N.; Guedes, C.A.; de França, S.M.; Breda, M.O.; Barbosa, D.R.S.; Araujo, A.M.N.; Guedes, C.A. The Sublethal Effects of Insecticides in Insects. In Biological Control of Pest and Vector Insects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Sluijs, J.P.; Amaral-Rogers, V.; Belzunces, L.P.; Bijleveld Van Lexmond, M.F.; Bonmatin, J.M.; Chagnon, M.; Downs, C.A.; Furlan, L.; Gibbons, D.W.; Giorio, C.; et al. Conclusions of the Worldwide Integrated Assessment on the Risks of Neonicotinoids and Fipronil to Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losey, J.E.; Vaughn, M. The Economic Value of Ecological Services Provided by Insects. Bioscience 2006, 56, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejomah, A. Effects of Neonicotinoids Through Food Web in Agroecosystem and Adjacent Habitats. 2025. Available online: https://BioRender.com/ol4lp4z (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Williamson, S.M.; Willis, S.J.; Wright, G.A. Exposure to Neonicotinoids Influences the Motor Function of Adult Worker Honeybees. Ecotoxicology 2014, 23, 1409–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colin, M.E.; Bonmatin, J.M.; Moineau, I.; Gaimon, C.; Brun, S.; Vermandere, J.P. A Method to Quantify and Analyze the Foraging Activity of Honey Bees: Relevance to the Sublethal Effects Induced by Systemic Insecticides. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2004, 47, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christen, V.; Grossar, D.; Charrière, J.D.; Eyer, M.; Jeker, L. Correlation between Increased Homing Flight Duration and Altered Gene Expression in the Brain of Honey Bee Foragers after Acute Oral Exposure to Thiacloprid and Thiamethoxam. Front. Insect Sci. 2021, 1, 765570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesselbach, H.; Scheiner, R. The Novel Pesticide Flupyradifurone (Sivanto) Affects Honeybee Motor Abilities. Ecotoxicology 2019, 28, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, M.; Armengaud, C.; Raymond, S.; Gauthier, M. Imidacloprid-Induced Facilitation of the Proboscis Extension Reflex Habituation in the Honeybee. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2001, 48, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrzycki, P.; Montanari, R.; Bortolotti, L.; Sabatini, A.G.; Maini, S.; Porrini, C. Effects of Imidacloprid Administered in Sub-Lethal Doses on Honey Bee Behaviour. Lab. Tests. Bull. Insectol. 2003, 56, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Suchail, S.; Guez, D.; Belzunces, L.P. Discrepancy between Acute and Chronic Toxicity Induced by Imidacloprid and Its Metabolites in Apis Mellifera. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2001, 20, 2482–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, S.; Nieh, J.C. A Common Neonicotinoid Pesticide, Thiamethoxam, Alters Honey Bee Activity, Motor Functions, and Movement to Light. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenna, D.; Cooley, H.; Pretelli, I.; Ramos Rodrigues, A.; Gill, S.D.; Gill, R.J. Pesticide Exposure Affects Flight Dynamics and Reduces Flight Endurance in Bumblebees. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 5637–5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, C.; Ebanks, B.; Hardy, I.C.W.; Davies, T.G.E.; Chakrabarti, L.; Stöger, R. Acute Imidacloprid Exposure Alters Mitochondrial Function in Bumblebee Flight Muscle and Brain. Front. Insect Sci. 2021, 1, 765179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crall, J.D.; Switzer, C.M.; Oppenheimer, R.L.; Ford Versypt, A.N.; Dey, B.; Brown, A.; Eyster, M.; Guérin, C.; Pierce, N.E.; Combes, S.A.; et al. Neonicotinoid Exposure Disrupts Bumblebee Nest Behavior, Social Networks, and Thermoregulation. Science 2018, 362, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, J.V.d.O.; Gomes, D.S.; da Silva, L.L.; de Oliveira, M.S.; Bastos, D.S.S.; Resende, M.T.C.S.; Alvim, J.R.L.; Reis, A.B.; de Oliveira, L.L.; Afzal, M.B.S.; et al. Effects of Sublethal Concentration of Thiamethoxam Formulation on the Wild Stingless Bee, Partamona helleri Friese (Hymenoptera: Apidae): Histopathology, Oxidative Stress and Behavioral Changes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crispim, P.D.; de Oliveira, V.E.S.; Batista, N.R.; Nocelli, R.C.F.; Antonialli-Junior, W.F. Lethal and Sublethal Dose of Thiamethoxam and Its Effects on the Behavior of a Non-Target Social Wasp. Neotrop. Entomol. 2023, 52, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.R.d.O.; Zanardi, O.Z.; Malaquias, J.B.; Souza Silva, C.A.; Yamamoto, P.T. The Impact of Four Widely Used Neonicotinoid Insecticides on Tetragonisca angustula (Latreille) (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Chemosphere 2019, 224, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, H.J.; Dale, A.M. Imidacloprid Seed Treatments Affect Individual Ant Behavior and Community Structure but Not Egg Predation, Pest Abundance or Soybean Yield. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, B.A.; Held, D.W.; Potter, D.A. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Bendiocarb, Halofenozide, and Imidacloprid on Harpalus Pennsylvanicus (Coleoptera: Carabidae) Following Different Modes of Exposure in Turfgrass. J. Econ. Entomol. 2001, 94, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, M.C.; Hladik, M.L.; McMurry, S.S.; Hittson, S.; Boyles, L.K.; Hoback, W.W. Neonicotinoid Exposure Causes Behavioral Impairment and Delayed Mortality of the Federally Threatened American Burying Beetle, Nicrophorus Americanus. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooming, E.; Merivee, E.; Must, A.; Merivee, M.I.; Sibul, I.; Nurme, K.; Williams, I.H. Behavioural Effects of the Neonicotinoid Insecticide Thiamethoxam on the Predatory Insect Platynus assimilis. Ecotoxicology 2017, 26, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunn, J.G.; Macaulay, S.J.; Matthaei, C.D. Food Shortage Amplifies Negative Sublethal Impacts of Low-Level Exposure to the Neonicotinoid Insecticide Imidacloprid on Stream Mayfly Nymphs. Water 2019, 11, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, B.R.; Whidden, E.; Gervasio, E.D.; Checchi, P.M.; Raley-Susman, K.M. Neonicotinoid-Containing Insecticide Disruption of Growth, Locomotion, and Fertility in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catae, A.F.; Roat, T.C.; Pratavieira, M.; da Silva Menegasso, A.R.; Palma, M.S.; Malaspina, O. Exposure to a Sublethal Concentration of Imidacloprid and the Side Effects on Target and Nontarget Organs of Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christen, V.; Mittner, F.; Fent, K. Molecular Effects of Neonicotinoids in Honey Bees (Apis mellifera). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4071–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miotelo, L.; Maloni, G.; Grella, T.C.; Nocelli, R.C.F.; Ferro, M.; Malaspina, O. Thiamethoxam-Induced Stress Responses in Melipona scutellaris: Insights into the Toxicological Effects on Malpighian Tubules. Apidologie 2025, 56, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloni, G.; Miotelo, L.; Otero, I.V.R.; de Souza, F.C.; Nocelli, R.C.F.; Malaspina, O. Acute Toxicity and Sublethal Effects of Thiamethoxam on the Stingless Bee Scaptotrigona postica: Survival, Neural Morphology, and Enzymatic Responses. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 369, 125864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Wang, D.; Li, H.; Xia, P.; Ran, Y.; You, J. Toxicogenomics Provides Insights to Toxicity Pathways of Neonicotinoids to Aquatic Insect, Chironomus dilutus. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decourtye, A.; Armengaud, C.; Renou, M.; Devillers, J.; Cluzeau, S.; Gauthier, M.; Pham-Delègue, M.H. Imidacloprid Impairs Memory and Brain Metabolism in the Honeybee (Apis mellifera L.). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2004, 78, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piiroinen, S.; Goulson, D. Chronic Neonicotinoid Pesticide Exposure and Parasite Stress Differentially Affects Learning in Honeybees and Bumblebees. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20160246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Chen, W.; Dong, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Nieh, J.C. A Neonicotinoid Impairs Olfactory Learning in Asian Honey Bees (Apis cerana) Exposed as Larvae or as Adults. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.B.; Arce, A.N.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Bischoff, P.H.; Burris, D.; Ahmed, F.; Gill, R.J. Insecticide Exposure during Brood or Early-Adult Development Reduces Brain Growth and Impairs Adult Learning in Bumblebees. Proc. R. Soc. B 2020, 287, 20192442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, F.; Francis, J.S.; Leonard, A.S. Modality-Specific Impairment of Learning by a Neonicotinoid Pesticide. Biol. Lett. 2019, 15, 20190359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, F.E.; Tibbetts, E.A. Field-Realistic Exposure to Neonicotinoid and Sulfoximine Insecticides Impairs Visual and Olfactory Learning and Memory in Polistes Paper Wasps. J. Exp. Biol. 2023, 226, 246083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramasingha, P.D.; Morrissey, C.A.; Phillips, I.D.; Crane, A.L.; Ferrari, M.C.O.; Chivers, D.P. Exposure to the Insecticide, Imidacloprid, Impairs Predator-Recognition Learning in Damselfly Larvae. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 123085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackenberg, M.C.; Giannoni-Guzmán, M.A.; Sanchez-Perez, E.; Doll, C.A.; Agosto-Rivera, J.L.; Broadie, K.; Moore, D.; McMahon, D.G. Neonicotinoids Disrupt Circadian Rhythms and Sleep in Honey Bees. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasman, K.; Rands, S.A.; Hodge, J.J.L. The Neonicotinoid Insecticide Imidacloprid Disrupts Bumblebee Foraging Rhythms and Sleep. iScience 2020, 23, 101827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siviter, H.; Folly, A.J.; Brown, M.J.F.; Leadbeater, E. Individual and Combined Impacts of Sulfoxaflor and Nosema bombi on Bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) Larval Growth. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 287, 20200935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.d.S.; Teixeira, J.S.G.; Vollet-Neto, A.; Queiroz, E.P.; Blochtein, B.; Pires, C.S.S.; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.L. Consumption of the Neonicotinoid Thiamethoxam during the Larval Stage Affects the Survival and Development of the Stingless Bee, Scaptotrigona Aff. depilis. Apidologie 2016, 47, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Ma, D.; Yu, C.; Liu, F.; Mu, W. Influence of Lethal and Sublethal Exposure to Clothianidin on the Seven-Spotted Lady Beetle, Coccinella septempunctata L. (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 161, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, J.; Luo, F.; Chen, Y.; Xie, M.; Liu, X.; Wei, H. The Toxicity Response of Coccinella septempunctata L. (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) after Exposure to Sublethal Concentrations of Acetamiprid. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Ren, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, D.; Hu, H.; Song, X.; Cui, J.; Ma, Y.; Yao, Y. Evaluation of the Toxicity and Sublethal Effects of Acetamiprid and Dinotefuran on the Predator Chrysopa pallens (Rambur) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). Toxics 2022, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Gadratagi, B.G.; Rana, D.K.; Ullah, F.; Adak, T.; Govindharaj, G.P.P.; Patil, N.B.; Mahendiran, A.; Desneux, N.; Rath, P.C. Multigenerational Insecticide Hormesis Enhances Fitness Traits in a Key Egg Parasitoid, Trichogramma chilonis Ishii. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rix, R.R.; Cutler, G.C. Low Doses of a Neonicotinoid Stimulate Reproduction in a Beneficial Predatory Insect. J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 2179–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, A.; Gadratagi, B.G.; Budhlakoti, N.; Rana, D.K.; Adak, T.; Govindharaj, G.P.P.; Patil, N.B.; Mahendiran, A.; Rath, P.C. Functional Response of an Egg Parasitoid, Trichogramma chilonis Ishii to Sublethal Imidacloprid Exposure. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 3656–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.B.; Mannion, C.M.; Klein, M.G.; Moyseenko, J.J.; Bishop, B. Effect of Insecticides on Tiphia vernalis (Hymenoptera: Tiphiidae) Oviposition and Survival of Progeny to Cocoon Stage When Parasitizing Popillia japonica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) Larvae. J. Econ. Entomol. 2005, 98, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dai, P.; Yang, X.; Ruan, C.; Biondi, A.; Desneux, N.; Zang, L. Selectivity of Novel and Traditional Insecticides Used for Management of Whiteflies on the Parasitoid Encarsia formosa. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2716–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberoni, D.; Favaro, R.; Baffoni, L.; Angeli, S.; Di Gioia, D. Neonicotinoids in the Agroecosystem: In-Field Long-Term Assessment on Honeybee Colony Strength and Microbiome. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 144116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morfin, N.; Goodwin, P.H.; Correa-Benitez, A.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Sublethal Exposure to Clothianidin during the Larval Stage Causes Long-Term Impairment of Hygienic and Foraging Behaviours of Honey Bees. Apidologie 2019, 50, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.W.; Tautz, J.; Grünewald, B.; Fuchs, S. RFID Tracking of Sublethal Effects of Two Neonicotinoid Insecticides on the Foraging Behavior of Apis mellifera. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tison, L.; Duer, A.; Púčiková, V.; Greggers, U.; Menzel, R. Detrimental Effects of Clothianidin on Foraging and Dance Communication in Honey Bees. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tison, L.; Hahn, M.L.; Holtz, S.; Rößner, A.; Greggers, U.; Bischoff, G.; Menzel, R. Honey Bees’ Behavior Is Impaired by Chronic Exposure to the Neonicotinoid Thiacloprid in the Field. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 7218–7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S.C.; Tiedeken, E.J.; Simcock, K.L.; Derveau, S.; Mitchell, J.; Softley, S.; Stout, J.C.; Wright, G.A. Bees Prefer Foods Containing Neonicotinoid Pesticides. Nature 2015, 521, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, A.N.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Yu, J.; Colgan, T.J.; Wurm, Y.; Gill, R.J. Foraging Bumblebees Acquire a Preference for Neonicotinoid-Treated Food with Prolonged Exposure. Proc. R. Soc. B 2018, 285, 20180655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leza, M.; Watrous, K.M.; Bratu, J.; Woodard, S.H. Effects of Neonicotinoid Insecticide Exposure and Monofloral Diet on Nest-Founding Bumblebee Queens. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20180761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, F.; Leonard, A.S. A Neonicotinoid Pesticide Impairs Foraging, but Not Learning, in Free-Flying Bumblebees. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, D.A.; Raine, N.E. Chronic Exposure to a Neonicotinoid Pesticide Alters the Interactions between Bumblebees and Wild Plants. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöfer, N.; Ackermann, J.; Hoheneder, J.; Hofferberth, J.; Ruther, J. Sublethal Effects of Four Insecticides Targeting Cholinergic Neurons on Partner and Host Finding in the Parasitic Wasp Nasonia vitripennis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 2400–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappert, L.; Pokorny, T.; Hofferberth, J.; Ruther, J. Sublethal Doses of Imidacloprid Disrupt Sexual Communication and Host Finding in a Parasitoid Wasp. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep42756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boff, S.; Friedel, A.; Mussury, R.M.; Lenis, P.R.; Raizer, J. Changes in Social Behavior Are Induced by Pesticide Ingestion in a Neotropical Stingless Bee. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 164, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapel, J.O.; Cortesero, A.M.; Lewis, W.J. Disruptive Sublethal Effects of Insecticides on Biological Control: Altered Foraging Ability and Life Span of a Parasitoid after Feeding on Extrafloral Nectar of Cotton Treated with Systemic Insecticides. Biol. Control 2000, 17, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.J.; Moffat, C.; Saranzewa, N.; Harvey, J.; Wright, G.A.; Connolly, C.N. Cholinergic Pesticides Cause Mushroom Body Neuronal Inactivation in Honeybees. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro, R.; Roved, J.; Haase, A.; Angeli, S. Impact of Chronic Exposure to Two Neonicotinoids on Honey Bee Antennal Responses to Flower Volatiles and Pheromonal Compounds. Front. Insect Sci. 2022, 2, 821145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, S.; Köhler, H.R. A Sublethal Imidacloprid Concentration Alters Foraging and Competition Behaviour of Ants. Ecotoxicology 2016, 25, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, R.F.; Lester, P.J.; Miller, A.S.; Ryan, K.G. A Neurotoxic Pesticide Changes the Outcome of Aggressive Interactions between Native and Invasive Ants. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20132157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar, F.; Reitz, S.; Jalali, M.A.; Ziaaddini, M.; Izadi, H. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Two Commercial Insecticides on Egg Parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) of Green Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, F.; Reitz, S.; Sardary, A.E.; Jalali, M.A.; Ziaaddini, M.; Izadi, H. Assessment of Toxicity Risk of Selected Insecticides Used in Pistachio Ecosystem on Two Egg Parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) of Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Yu, C.; Liu, F.; Mu, W. Sublethal and Transgenerational Effects of Thiamethoxam on the Demographic Fitness and Predation Performance of the Seven-Spot Ladybeetle Coccinella septempunctata L. (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Chemosphere 2019, 216, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.E.; avia Alves, F.M.; Pereira, R.C.; Aquino, L.A.; Fernandes, F.L.; Zanuncio, J.C. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Seven Insecticides on Three Beneficial Insects in Laboratory Assays and Field Trials. Chemosphere 2016, 156, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, J.W.; Desneux, N.; He, Y.X.; Weng, Q.Y. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Thiamethoxam on the Whitefly Predator Serangium japonicum (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) through Different Exposure Routes. Chemosphere 2015, 128, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Desneux, N.; Wu, K. Lethal Effect of Imidacloprid on the Coccinellid Predator Serangium japonicum and Sublethal Effects on Predator Voracity and on Functional Response to the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Ecotoxicology 2012, 21, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lv, H.; Li, X.; Wan, H.; He, S.; Li, J.; Ma, K. Sublethal Effects of Acetamiprid and Afidopyropen on Harmonia axyridis: Insights from Transcriptomics Analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 262, 115203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsons, K.A.; Tooker, J.F. Acute Toxicity of Neonicotinoid Insecticides to Ground Beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) from Pennsylvania. Environ. Entomol. 2025, 54, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinou, A.F.; Seraphides, N.; Stavrinides, M.C. Lethal and Behavioral Effects of Pesticides on the Insect Predator Macrolophus Pygmaeus. Chemosphere 2014, 96, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.J.; Wang, N.M.; Yu, Q.T.; Xue, C.B. Acute Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Four Insecticides on the Lacewing (Chrysoperla sinica Tjeder). Chemosphere 2020, 250, 12632110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korenko, S.; Saska, P.; Kysilková, K.; Řezáč, M.; Heneberg, P. Prey Contaminated with Neonicotinoids Induces Feeding Deterrent Behavior of a Common Farmland Spider. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezáč, M.; Řezáčová, V.; Heneberg, P. Contact Application of Neonicotinoids Suppresses the Predation Rate in Different Densities of Prey and Induces Paralysis of Common Farmland Spiders. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forfert, N.; Troxler, A.; Retschnig, G.; Gauthier, L.; Straub, L.; Moritz, R.F.A.; Neumann, P.; Williams, G.R. Neonicotinoid Pesticides Can Reduce Honeybee Colony Genetic Diversity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.R.; Troxler, A.; Retschnig, G.; Roth, K.; Yañez, O.; Shutler, D.; Neumann, P.; Gauthier, L. Neonicotinoid Pesticides Severely Affect Honey Bee Queens. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, A.N.; King, B.H. A Neonicotinoid Affects the Mating Behavior of Spalangia endius (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), a Biological Control Agent of Filth Flies. Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenko, S.; Sýkora, J.; Řezáč, M.; Heneberg, P. Neonicotinoids Suppress Contact Chemoreception in a Common Farmland Spider. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, L.; Minnameyer, A.; Camenzind, D.; Kalbermatten, I.; Tosi, S.; Van Oystaeyen, A.; Wäckers, F.; Neumann, P.; Strobl, V. Thiamethoxam as an Inadvertent Anti-Aphrodisiac in Male Bees. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, V.; Albrecht, M.; Villamar-Bouza, L.; Tosi, S.; Neumann, P.; Straub, L. The Neonicotinoid Thiamethoxam Impairs Male Fertility in Solitary Bees, Osmia cornuta. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehorn, P.R.; O’Connor, S.; Wackers, F.L.; Goulson, D. Neonicotinoid Pesticide Reduces Bumble Bee Colony Growth and Queen Production. Science 2012, 336, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laycock, I.; Lenthall, K.M.; Barratt, A.T.; Cresswell, J.E. Effects of Imidacloprid, a Neonicotinoid Pesticide, on Reproduction in Worker Bumble Bees (Bombus terrestris). Ecotoxicology 2012, 21, 1937–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, G.L.; Jansen, V.A.A.; Brown, M.J.F.; Raine, N.E. Pesticide Reduces Bumblebee Colony Initiation and Increases Probability of Population Extinction. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siviter, H.; Brown, M.J.F.; Leadbeater, E. Sulfoxaflor Exposure Reduces Bumblebee Reproductive Success. Nature 2018, 561, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis Chan, D.S.; Raine, N.E. Population Decline in a Ground-Nesting Solitary Squash Bee (Eucera pruinosa) Following Exposure to a Neonicotinoid Insecticide Treated Crop (Cucurbita pepo). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehorn, P.R.; Cook, N.; Blackburn, C.V.; Gill, S.M.; Green, J.; Shuker, D.M. Sex Allocation Theory Reveals a Hidden Cost of Neonicotinoid Exposure in a Parasitoid Wasp. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 201503089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidpour, M.; Maroofpour, N.; Ghane-Jahromi, M. Potential Demographic Impact of the Insecticide Mixture between Thiacloprid and Deltamethrin on the Cotton Aphid and Two of Its Natural Enemies. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2023, 113, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schläppi, D.; Kettler, N.; Straub, L.; Glauser, G.; Neumann, P. Long-Term Effects of Neonicotinoid Insecticides on Ants. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, P.C.; Moscardini, V.F.; Michaud, J.P.; Carvalho, G.A. Non-Target Effects of Chlorantraniliprole and Thiamethoxam on Chrysoperla carnea When Employed as Sunflower Seed Treatments. J. Pest Sci. 2014, 87, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, M.N.; Schneider, M.I.; Desneux, N.; González, B.; Ronco, A.E. Impact of the Neonicotinoid Acetamiprid on Immature Stages of the Predator Eriopis connexa (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Ecotoxicology 2013, 22, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo-Agudo, M.; González-Cabrera, J.; Picó, Y.; Calatayud-Vernich, P.; Urbaneja, A.; Dicke, M.; Tena, A. Neonicotinoids in Excretion Product of Phloem-Feeding Insects Kill Beneficial Insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 16817–16822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada, C.R.; Scharf, M.E. Whiteflies Can Excrete Insecticide-Tainted Honeydew on Tomatoes. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 337, 122527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grafton-Cardwell, E.E.; Lee, J.E.; Robillard, S.M.; Gorden, J.M. Role of Imidacloprid in Integrated Pest Management of California Citrus. J. Econ. Èntomol. 2008, 101, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.R.; Rohr, J.R.; Tooker, J.F. Neonicotinoid Insecticide Travels through a Soil Food Chain, Disrupting Biological Control of Non-Target Pests and Decreasing Soya Bean Yield. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, R.; Stork, A. Uptake, Translocation and Metabolism of Imidacloprid in Plants. Bull. Insectol. 2003, 56, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. 2010 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Decontamination Research and Development Conference; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, C.A.; Mineau, P.; Devries, J.H.; Sanchez-Bayo, F.; Liess, M.; Cavallaro, M.C.; Liber, K. Neonicotinoid Contamination of Global Surface Waters and Associated Risk to Aquatic Invertebrates: A Review. Environ. Int. 2015, 74, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, A.; Limay-Rios, V.; Xue, Y.; Smith, J.; Baute, T. Field-scale Examination of Neonicotinoid Insecticide Persistence in Soil as a Result of Seed Treatment Use in Commercial Maize (Corn) Fields in Southwestern Ontario. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredeson, M.M.; Lundgren, J.G. Neonicotinoid Insecticidal Seed-Treatment on Corn Contaminates Interseeded Cover Crops Intended as Habitat for Beneficial Insects. Ecotoxicology 2019, 28, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichel, L.; Nauen, R. Uptake, Translocation and Bioavailability of Imidacloprid in Several Hop Varieties. Pest Manag. Sci. 2004, 60, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonmatin, J.M.; Giorio, C.; Girolami, V.; Goulson, D.; Kreutzweiser, D.P.; Krupke, C.; Liess, M.; Long, E.; Marzaro, M.; Mitchell, E.A.; et al. Environmental Fate and Exposure; Neonicotinoids and Fipronil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girolami, V.; Mazzon, L.; Squartini, A.; Mori, N.; Marzaro, M.; Bernardo, A.D.; Greatti, M.; Giorio, C.; Tapparo, A. Translocation of Neonicotinoid Insecticides from Coated Seeds to Seedling Guttation Drops: A Novel Way of Intoxication for Bees. J. Econ. Entomol. 2009, 102, 1808–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Veire, M.; Tirry, L. Side Effects of Pesticides on Four Species of Beneficials Used in IPM in Glasshouse Vegetable Crops: “Worst Case” Laboratory Tests. Pestic. Benef. Org. 2003, 26, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa, M.; Yamamoto, I. Structure-Activity Relationships of Nicotinoids and Imidacloprid Analogs. J. Pestic. Sci. 1993, 18, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomizawa, M.; Casida, J.E. Molecular Recognition of Neonicotinoid Insecticides: The Determinants of Life or Death. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadón, A.; Ares, I.; Martínez, M.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.R.; Martínez, M.A. Neurotoxicity of Neonicotinoids. In Advances in Neurotoxicology; Aschner, M., Costa, L.G., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 4, pp. 167–207. [Google Scholar]

- Martelli, F.; Zhongyuan, Z.; Wang, J.; Wong, C.O.; Karagas, N.E.; Roessner, U.; Rupasinghe, T.; Venkatachalam, K.; Perry, T.; Bellen, H.J.; et al. Low Doses of the Neonicotinoid Insecticide Imidacloprid Induce ROS Triggering Neurological and Metabolic Impairments in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25840–25850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuščíková, L.; Bažány, D.; Greifová, H.; Knížatová, N.; Kováčik, A.; Lukáč, N.; Jambor, T. Screening of Toxic Effects of Neonicotinoid Insecticides with a Focus on Acetamiprid: A Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayo, F.; Tennekes, H.A. Time-Cumulative Toxicity of Neonicotinoids: Experimental Evidence and Implications for Environmental Risk Assessments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, M.E.; Flattum, R.F. The Mode of Action and Neurotoxic Properties of the Nitromethylene Heterocycle Insecticides. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1984, 22, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauen, R.; Ebbinghaus-Kintscher, U.; Schmuck, R. Toxicity and Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Interaction of Imidacloprid and Its Metabolites in Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2001, 57, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünewald, B.; Siefert, P. Acetylcholine and Its Receptors in Honeybees: Involvement in Development and Impairments by Neonicotinoids. Insects 2019, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor-Wells, J.; Brooke, B.D.; Bermudez, I.; Jones, A.K. The Neonicotinoid Imidacloprid, and the Pyrethroid Deltamethrin, Are Antagonists of the Insect Rdl GABA Receptor. J. Neurochem. 2015, 135, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasman, K.; Hidalgo, S.; Zhu, B.; Rands, S.A.; Hodge, J.J.L. Neonicotinoids Disrupt Memory, Circadian Behaviour and Sleep. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelito, K.R.; Shafer, O.T. Reciprocal Cholinergic and GABAergic Modulation of the Small Ventrolateral Pacemaker Neurons of Drosophila’s Circadian Clock Neuron Network. J. Neurophysiol. 2012, 107, 2096–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Shi, J.; Yu, L.; Wu, X. Metabolic Profiling of Apis mellifera Larvae Treated with Sublethal Acetamiprid Doses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 254, 114716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, A.; Yin, L.; Ke, L.; Dai, P.; Liu, Y.-J. Early-Life Sublethal Thiacloprid Exposure to Honey Bee Larvae: Enduring Effects on Adult Bee Cognitive Abilities. Toxics 2024, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, Z.; Li, M.; Fang, Y.; Qu, J.; Mao, T.; Chen, J.; Li, F.; Sun, H.; Li, B. Responses of Detoxification Enzymes in the Midgut of Bombyx mori after Exposure to Low-Dose of Acetamiprid. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P. Hormesis Defined. Ageing Res. Rev. 2008, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E.; Blande, J.D.; Masui, N.; Calabrese, E.J.; Zhang, J.; Sicard, P.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Benelli, G. Sublethal Chemical Stimulation of Arthropod Parasitoids and Parasites of Agricultural and Environmental Importance. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarko, A.R.; Leonard, A.S.; Mathew, D. A Neonicotinoid Pesticide Alters Drosophila Olfactory Processing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, R.H.; Gray, J.R. Neural Conduction, Visual Motion Detection, and Insect Flight Behaviour Are Disrupted by Low Doses of Imidacloprid and Its Metabolites. NeuroToxicology 2019, 72, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prouty, C.; Bartlett, L.J.; Krischik, V.; Altizer, S. Adult Monarch Butterflies Show High Tolerance to Neonicotinoid Insecticides. Ecol. Entomol. 2023, 48, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, B.A.; Isaac, N.J.B.; Bullock, J.M.; Roy, D.B.; Garthwaite, D.G.; Crowe, A.; Pywell, R.F. Impacts of Neonicotinoid Use on Long-Term Population Changes in Wild Bees in England. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.M.; Maus, C. The Relevance of Sublethal Effects in Honey Bee Testing for Pesticide Risk Assessment. Pest Manag. Sci. 2007, 63, 1058–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.E.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. Communication in Ants. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, R570–R574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, R.H.; Zhang, S.; Gray, J.R. Neonicotinoid and Sulfoximine Pesticides Differentially Impair Insect Escape Behavior and Motion Detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 5510–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.H.; Heard, M.S.; Isaac, N.J.B.; Roy, D.B.; Procter, D.; Eigenbrod, F.; Freckleton, R.; Hector, A.; Orme, C.D.L.; Petchey, O.L.; et al. Biodiversity and Resilience of Ecosystem Functions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, E.J.; Yearsley, J.M.; Crowe, T.P.; Emmerson, M.C.; Jacob, U.; Petchey, O.L. Loss of Functionally Unique Species May Gradually Undermine Ecosystems. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 278, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zeng, L.; Chen, J. Sublethal Effect of Imidacloprid on Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Feeding, Digging, and Foraging Behavior. Environ. Entomol. 2015, 44, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zeng, L.; Chen, J. Impact of Imidacloprid on New Queens of Imported Fire Ants, Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L. Toxicity and Sublethal Effects of Sulfoxaflor on the Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 139, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, D.L. Insect Declines in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stork, N.E. How Many Species of Insects and Other Terrestrial Arthropods Are There on Earth? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stork, N.E.; McBroom, J.; Gely, C.; Hamilton, A.J. New Approaches Narrow Global Species Estimates for Beetles, Insects, and Terrestrial Arthropods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7519–7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.D.; Tooker, J.F. Neonicotinoids Pose Undocumented Threats to Food Webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22609–22613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooker, J.F.; Pearsons, K.A. Newer Characters, Same Story: Neonicotinoid Insecticides Disrupt Food Webs through Direct and Indirect Effects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021, 46, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humann-Guilleminot, S.; Clément, S.; Desprat, J.; Binkowski, Ł.J.; Glauser, G.; Helfenstein, F. A Large-Scale Survey of House Sparrows Feathers Reveals Ubiquitous Presence of Neonicotinoids in Farmlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 660, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, C.; Bertrand, C.; Daniele, G.; Coeurdassier, M.; Benoit, P.; Nélieu, S.; Lafay, F.; Bretagnolle, V.; Gaba, S.; Vulliet, E.; et al. Residues of Currently Used Pesticides in Soils and Earthworms: A Silent Threat? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 305, 107167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beketov, M.A.; Kefford, B.J.; Schäfer, R.B.; Liess, M. Pesticides Reduce Regional Biodiversity of Stream Invertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 11039–11043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisa, L.W.; Amaral-Rogers, V.; Belzunces, L.P.; Bonmatin, J.M.; Downs, C.A.; Goulson, D.; Kreutzweiser, D.P.; Krupke, C.; Liess, M.; Mcfield, M.; et al. Effects of Neonicotinoids and Fipronil on Non-Target Invertebrates. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 22, 68–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagnon, M.; Kreutzweiser, D.; Mitchell, E.A.D.; Morrissey, C.A.; Noome, D.A.; Van der Sluijs, J.P. Risks of Large-Scale Use of Systemic Insecticides to Ecosystem Functioning and Services. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, M.C.; Main, A.R.; Liber, K.; Phillips, I.D.; Headley, J.V.; Peru, K.M.; Morrissey, C.A. Neonicotinoids and Other Agricultural Stressors Collectively Modify Aquatic Insect Communities. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmentlo, H.S.; Schrama, M.; De Snoo, G.R.; Van Bodegom, P.M.; Van Nieuwenhuijzen, A.; Vijver, M.G. Experimental Evidence for Neonicotinoid Driven Decline in Aquatic Emerging Insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2105692118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniec, A.; Creary, S.F.; Laskowski, K.L.; Nyrop, J.P.; Raupp, M.J. Neonicotinoid Insecticide Imidacloprid Causes Outbreaks of Spider Mites on Elm Trees in Urban Landscapes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniec, A.; Raupp, M.J.; Parker, R.D.; Kerns, D.; Eubanks, M.D. Neonicotinoid Insecticides Alter Induced Defenses and Increase Susceptibility to Spider Mites in Distantly Related Crop Plants. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.F.; Aguirre, N.M.; Carvalho, G.A.; Grunseich, J.M.; Helms, A.M.; Peñaflor, M.F.G.V. Effects of Neonicotinoid Seed Treatment on Maize Anti-Herbivore Defenses Vary across Plant Genotypes. J. Pest Sci. 2024, 97, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.