Simulated Heatwaves Affect Development of Two Congeneric Gregarious Larval–Pupal Endoparasitoids

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Cultures

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

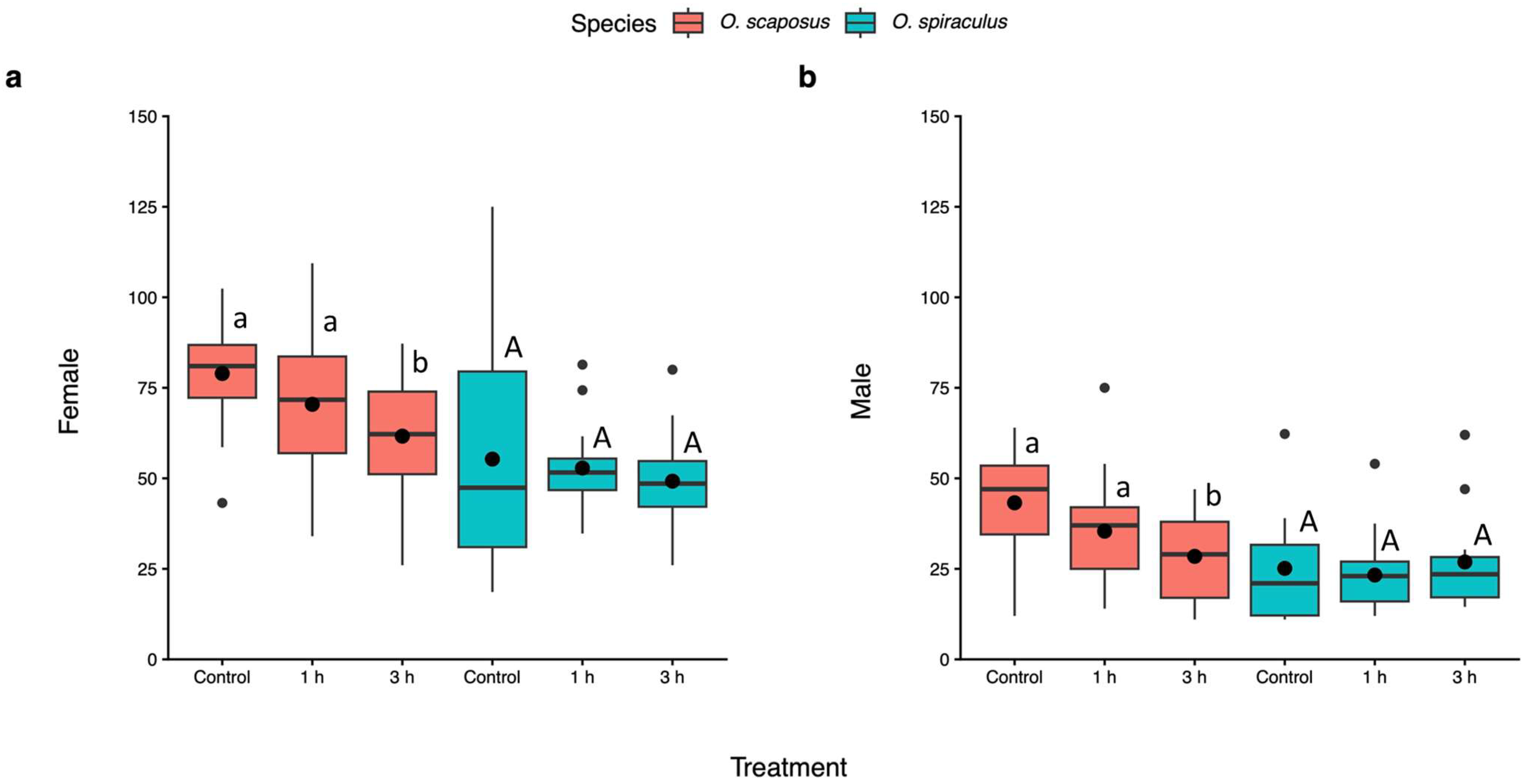

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barret, K.; et al. IPCC 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers; Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsolver, J.G.; Buckley, L.B. Evolution of plasticity and adaptive responses to climate change along climate gradients. Proc. R. Soc. B 2017, 284, 20170386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, L.D.; van de Pol, M. Tackling extremes: Challenges for ecological and evolutionary research on extreme climatic events. J. Anim. Ecol. 2016, 85, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasseur, D.A.; DeLong, J.P.; Gilbert, B.; Greig, H.S.; Harley, C.D.G.; McCann, K.S.; Savage, V.; Tunney, T.D.; O’Connor, M.I. Increased temperature variation poses a greater risk to species than climate warming. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20132612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colinet, H.; Sinclair, B.J.; Vernon, P.; Renault, D. Insects in fluctuating thermal environments. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015, 60, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-S.; Ma, G.; Pincebourde, S. Survive a warming climate: Insect responses to extreme high temperatures. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 66, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iltis, C.; Louapre, P.; Vogelweith, F.; Thiéry, D.; Moreau, J. How to stand the heat? Post-stress nutrition and developmental stage determine insect response to a heat wave. J. Insect Physiol. 2021, 131, 104214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Tokman, D.; Córdoba-Aguilar, A.; Dáttilo, W.; Lira-Noriega, A.; Sánchez-Guillén, R.A.; Villalobos, F. Insect responses to heat: Physiological mechanisms, evolution and ecological implications in a warming world. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 802–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Ma, C.S. Daily temperature extremes play an important role in predicting thermal effects. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 2289–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A. Conserving host–parasitoid interactions in a warming world. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 12, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Li, S.-M.; Ma, C.-S. Extreme climate shifts pest dominance hierarchy through thermal evolution and transgenerational plasticity. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 1524–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoks, R.; Verheyen, J.; Dievel, M.V.; Tüzün, N. Daily temperature variation and extreme high temperatures drive performance and biotic interactions in a warming world. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017, 23, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Heinen, R.; Gols, R.; Thakur, M.P. Climate change-mediated temperature extremes and insects: From outbreaks to breakdowns. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 6685–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-H.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Thomson, L.J. Potential impact of climate change on parasitism efficiency of egg parasitoids: A meta-analysis of Trichogramma under variable climate conditions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 231, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.N.; Zhang, W.; Ma, G.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Ma, C.S. A single hot event stimulates adult performance but reduces egg survival in the oriental fruit moth, Grapholitha molesta. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e116339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Rudolf, V.H.W.; Ma, C.S. Stage-specific heat effects: Timing and duration of heat waves alter demographic rates of a global insect pest. Oecologia 2015, 179, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauerfeind, S.S.; Fischer, K. Integrating temperature and nutrition–environmental impacts on an insect immune system. J. Insect Physiol. 2014, 64, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfray, H.C.J. Parasitoids: Behavioral and Evolutionary Ecology, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, M.J.; Zalucki, M.P. Climate change and biological control: The consequences of increasing temperatures on host–parasitoid interactions. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017, 20, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffs, C.T.; Lewis, O.T. Effects of climate warming on host–parasitoid interactions. Ecol. Entomol. 2013, 38, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Lann, C.; Van Baaren, J.; Visser, B. Dealing with predictable and unpredictable temperatures in a climate change context: The case of parasitoids and their hosts. J. Exp. Biol. 2021, 224, jeb238626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gols, R.; Biere, A.; Harvey, J.A. Differential effects of climate warming on reproduction and functional responses on insects in the fourth trophic level. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceryngier, P.; Roy, H.E.; Poland, R.L. Natural Enemies of Ladybird Beetles. In Ecology and Behaviour of the Ladybird Beetles (Coccinellidae), 1st ed.; Hodek, I., van Emden, H.F., Honěk, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012; Volume 16, pp. 375–443. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, M.H.; Gols, R.; Harvey, J.A. The biology and ecology of parasitoid wasps of predatory arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2023, 68, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, W.D. Extraordinary sex ratios: A sex-ratio theory for sex linkage and inbreeding has new implications in cytogenetics and entomology. Science 1967, 156, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.F. The Insects: Structure and Function, 5th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.-H.; Shiao, S.-F.; Okuyama, T. Development of insects under fluctuating temperature: A review and case study. J. Appl. Entomol. 2015, 139, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roff, D.A. The Evolution of Life Histories: Theory and Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, K.; Kölzow, N.; Höltje, H.; Karl, I. Assay conditions in laboratory experiments: Is the use of constant rather than fluctuating temperatures justified when investigating temperature-induced plasticity? Oecologia 2011, 166, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visser, B.; Le Lann, C.; den Blanken, F.J.; Harvey, J.A.; van Alphen, J.J.M.; Ellers, J. Loss of lipid synthesis as an evolutionary consequence of a parasitic lifestyle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 107, 8677–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Li, B.; Fei, M. Simulated Heatwaves Affect Development of Two Congeneric Gregarious Larval–Pupal Endoparasitoids. Insects 2026, 17, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010025

Wang L, Zhao Y, Jiao Z, Li B, Fei M. Simulated Heatwaves Affect Development of Two Congeneric Gregarious Larval–Pupal Endoparasitoids. Insects. 2026; 17(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lizhi, Yanli Zhao, Zhihui Jiao, Baoping Li, and Minghui Fei. 2026. "Simulated Heatwaves Affect Development of Two Congeneric Gregarious Larval–Pupal Endoparasitoids" Insects 17, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010025

APA StyleWang, L., Zhao, Y., Jiao, Z., Li, B., & Fei, M. (2026). Simulated Heatwaves Affect Development of Two Congeneric Gregarious Larval–Pupal Endoparasitoids. Insects, 17(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010025