Simple Summary

Chironomidae, a highly diverse family of freshwater flies, possess an unparalleled ability to thrive in a vast array of aquatic environments. The Chironomidae family is currently divided into 11 subfamilies, with the subfamily Tanypodinae comprising nearly 60 genera and over 600 species worldwide, and the genus Ablabesmyia being one of the largest within the Pentaneurini tribe. The mitochondrial genome of the genus Ablabesmyia has not yet been reported. We have undertaken the sequencing, assembly, and annotation of the mitochondrial genomes for a selection of species within the genus Ablabesmyia, which includes eight distinct species. Our comprehensive examination, which includes a total of 17 mitochondrial genomes, offers unprecedented insights into the evolutionary narratives of these taxa, contributing significantly to the field of entomology and evolutionary biology.

Abstract

(1) Background: The insect mitogenome encodes essential genetic components and serves as an effective marker for molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis in insects due to its small size, maternal inheritance, and rapid evolution. The morphological identification of Ablabesmyia is challenging, particularly for non-experts. Thus, there is an increasing need for molecular data to improve classification accuracy and phylogenetic analysis. (2) Methods: Our analysis encompassed eight species of Ablabesmyia, a single species of Conchapelopia, one species of Denopelopia, and one species of Thienemannimyia, all originating from China. We then performed a comprehensive analysis of the nucleotide composition, sequence length, and evolutionary rate. (3) Results: All newly assembled mitogenomes displayed a negative GC-skew, indicating a cytosine bias, while most exhibited a positive AT-skew, reflecting an adenine and thymine abundance. All thirteen protein-coding genes (PCGs) featured the conventional start codon ATN, aligning closely with the typical mitochondrial start codon observed in insects. The evolutionary rates of these PCGs can be ordered as follows: ND2 > ATP8 > ND6 > ND4 > ND5 > ND3 > ND4L > ND1 > CYTB > COIII > ATP6 > COII > COI. (4) Conclusions: These newly sequenced mitogenomes exhibit structural features and nucleotide compositions that closely align with those of previously reported Chironomidae species, marking a significant expansion of the chironomid mitogenome database.

1. Introduction

Recently, insect mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) have attracted increased research attention for their remarkable conservation in structure and gene arrangement, mirroring those of their ancestral forms [1,2,3,4,5]. The insect mitogenome, a double-stranded circular molecule of 14–20 kb, encodes essential genetic components and serves as an effective marker for molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis in Insecta due to its small size, maternal inheritance, and rapid evolution [6,7,8,9,10].

Chironomidae, a highly diverse family of freshwater midges, possess an unparalleled ability to thrive in a vast array of aquatic environments, ranging from oxygen-depleted waters to the frigid peaks of the Himalayas and the deep abyss of Lake Baikal [11]. Their remarkable resilience in extreme conditions, such as temperatures as low as −16 °C, and their status as one of the most widely distributed insects globally, make them invaluable bioindicators for assessing ecological health and detecting environmental changes [12,13]. With an estimated 15,000 species worldwide, these aquatic insects exhibit exceptional species diversity, which can be attributed to their ancient lineage, limited dispersal, and evolutionary flexibility [11]. They play a crucial role in aquatic ecosystems by significantly contributing to the processing of detritus and influencing trophic dynamics. Their tolerance to harsh conditions also renders them valuable for ecological and water quality assessments [14]. Furthermore, their high population densities and unique life cycle characteristics are central to theoretical ecological studies and have practical applications in biological monitoring and as a food source for various animals [15,16].

The Chironomidae family is currently classified into 11 subfamilies within the global taxonomy system [17,18]. Among these subfamilies, Orthocladiinae, Tanypodinae, and Chironominae are particularly notable, as they encompass the greatest number of species and have a broad distribution across the globe [19]. The subfamily Tanypodinae, comprising nearly 60 genera and over 600 species worldwide, is divided into eight tribes, with the largest being the tribe Pentaneurini [20,21]. The genus Ablabesmyia, one of the largest within the Pentaneurini tribe, was established by Johannsen in 1905, with Tipula monilis Linnaeus 1758 designated as the type species [22].

The genus Ablabesmyia, featuring four subgenera—Ablabesmyia Johannsen, Asayia Roback, Karelia Roback, and Sartaia Roback, is distinguished among Chironomidae by the unique characteristics of its adult genitalia [23,24]. The male Ablabesmyia are easily recognized by their vibrant pigmentation, which adorns their leg bands and wings, and further distinguished by the unique arrangement of acrostichal setae that diverge around the prescutellar depression, framing the medial scar—a hallmark of the genus [25]. During the pupal stage, the genus Ablabesmyia stands out with a distinctive set of features, including a robust thoracic horn, a pronounced thoracic comb, and an adhesive sheath encasing the anal macrosetae [26]. The larvae of Ablabesmyia are marked by several distinctive traits: typically, one to three dark posterior parapod claws, a segmentation of the basal segment of the maxillary palp into two to six parts with the ring organ positioned between the two most distal segments, and pecten hypopharyngeal teeth that are notably unequal in size, all of which serve as diagnostic characteristics for this genus [27]. The larvae of Ablabesmyia are eurytopic, living in a variety of small and large lotic and lentic waters, bog pools, the littoral part of eutrophic lakes, and in rivers [22,27]. The morphological identification of Ablabesmyia can be quite challenging, especially for those without expert knowledge. Therefore, there is a growing need for additional molecular data to facilitate accurate classification and to enhance phylogenetic analysis.

In order to elucidate the mitochondrial genomes of the genus Ablabesmyia and to deepen our understanding of the intricate phylogenetic relationships within the family Chironomidae, we have undertaken the sequencing, assembly, and annotation of the mitochondrial genomes for a selection of species within the genus Ablabesmyia, which includes eight distinct species. Additionally, we have included the mitogenomes of one species each from Conchapelopia, Denopelopia, and Thienemannimyia. To enrich our analysis and provide a more profound comprehension of the mitogenome’s characteristics, we have also incorporated six mitogenomes that have been published previously. Leveraging the strength of Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods, we have conducted a thorough analysis across various databases. This approach has allowed us to unravel the complex phylogenetic relationships within the subfamily Tanypodinae. Our comprehensive examination, which includes a total of 17 mitochondrial genomes, offers unprecedented insights into the evolutionary narratives of these taxa, contributing significantly to the fields of entomology and evolutionary biology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Taxon Sampling and Sequencing

Our analysis encompassed eight species of Ablabesmyia, a single species of Conchapelopia, one species of Denopelopia, and one species of Thienemannimyia, all originating from China, with detailed information provided in Table 1. Additionally, for the purposes of comparative mitogenomic analysis and phylogenetic reconstruction, we retrieved the mitogenomes of Clinotanypus yani Cheng & Wang, 2008 and Tanypus punctipennis Meigen, 1818 from GenBank [16,28]. Building upon extensive prior phylogenetic research conducted on Chironomidae, we selected four species that served as outgroups from each of the closely related genera: Cricotopus dentatus Hirvenoja, 1985, Cricotopus bicinctus (Meigen, 1818), Boreoheptagyia alulasetosa Makarchenko, Wu & Wang, 2008, and Boreoheptagyia kurobebrevis (Sasa & Okazawa, 1992). Before DNA extraction and morphological examination, all samples were preserved in a solution containing 85% to 95% ethanol and stored at a temperature of −20 °C.

Table 1.

Collection information of newly sequenced species in this study.

To extract total genomic DNA, we utilized the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (DP304; TIANGEN, Beijing, China). The voucher specimens have been deposited at the College of Life Sciences, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China, for potential future reference and investigation. The whole genome samples were then sent to Berry Genomics in Beijing, China, for sequencing. For library preparation, we employed the TruSeq Nano DNA HT Sample Preparation Kit from Illumina (United States Illumina Company, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (United States Illumina Company, San Diego, CA, USA) using a paired-end strategy (PE150), targeting DNA fragments with an insert size of 350 bp. After sequencing, raw reads were processed using Trimmomatic, and the resulting clean reads were retained for further downstream analyses [29].

2.2. Assembly, Annotation, and Composition Analyses

To reconstruct the mitogenome sequences, we utilized NOVOPlasty v3.8.3 (Brussels, Belgium) in a de novo assembly approach, starting with the COI gene as the seed sequence and exploring a spectrum of k-mer sizes ranging from 23 to 39 bp to optimize the mitogenome assembly [30]. Annotation of the mitogenome adhered to the protocol outlined by [31], with enhancements. Specifically, the secondary structure of tRNAs was deciphered using the MITOS WebServer, while rRNAs and protein-coding genes (PCGs) were annotated manually within Geneious, leveraging the Clustal Omega algorithm for alignment [32]. To further validate and refine the boundaries of rRNAs and PCGs, we employed the Clustal W function available in MEGA 11. The analysis of nucleotide composition bias and the composition of individual genes was conducted using SeqKit v0.16.0, a tool developed in Chongqing, China [33]. Visualization of the mitochondrial genome map was accomplished using the CGView server, which is available at https://cgview.ca/ (accessed on 15 July 2024) [34]. MEGA 11 was utilized to determine the nucleotide composition, codon usage, and relative synonymous codon usage of the mitochondrial genome [35]. Quantification of nucleotide composition bias was achieved through the calculation of AT-skew, defined as (A − T)/(A + T), and GC-skew, calculated as (G − C)/(G + C). Furthermore, we computed the synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous substitution rates (Ka) using DnaSP6.0 [34], providing insights into the evolutionary dynamics of the mitogenome.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

To construct phylogenetic trees, we selectively isolated two ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes and thirteen protein-coding genes (PCGs) from seventeen mitochondrial genomes. Sequence alignment for both nucleotides and proteins was carried out using MAFFT (Osaka, Japan), employing the L-INS-I algorithm to exclude ambiguous alignments. Trimming of sequences was then executed with Trimal v1.4.1 (Barcelona, Spain), preparing the sequences for phylogenetic analysis. This analysis was based on five distinct data matrices generated by FASconCAT-G v1.04 (Santa Cruz, CA, USA), specifically configured as follows: (1) cds_fna, encompassing all codon positions of the 13 PCGs; (2) cds_rna, integrating all codon positions of the 13 PCGs along with the two rRNA sequences; (3) cds12_rna, incorporating the first and second codon positions of the 13 PCGs and the two rRNA sequences; (4) cds12, focusing solely on the first and second codon positions of the 13 PCGs; and (5) cds_faa, utilizing the amino acid sequences derived from the 13 PCGs. To quantify the variability among these matrices, we utilized AliGROOVE v1.06 (Bonn, Germany), drawing inspiration from previous studies conducted by [35,36,37,38]. For the ML analysis, the optimal substitution models are used for each gene partition. The bootstrapping phase and node support were calculated by using 1000 replicates. Following this, maximum likelihood (ML) trees were constructed using IQ-tree v2.0.7, and Bayesian inference (BI) trees were constructed using Phylobayes-MPI v1.8, providing robust insights into the evolutionary relationships among the mitochondrial genomes under investigation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mitogenomic Organization

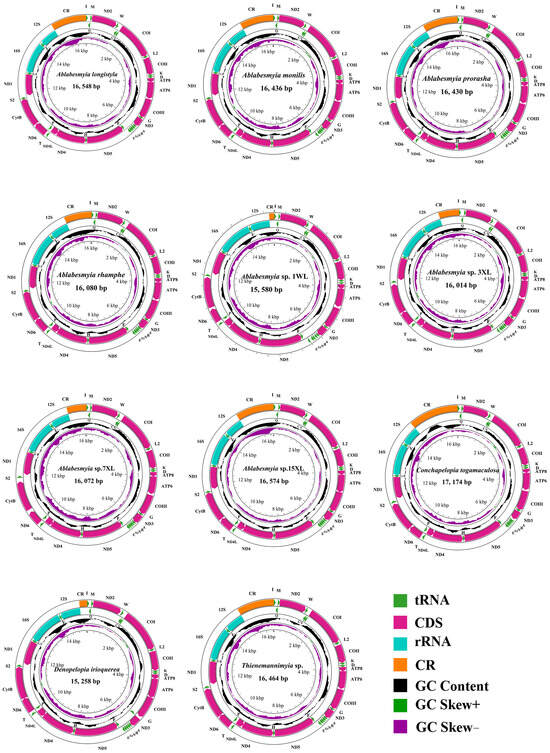

The sequences newly acquired exhibited a range of lengths, varying from 15,258 base pairs (bp) in Denopelopia irioquerea to 17,174 bp in Conchapelopia togamaculosa. The primary factor contributing to this variation was the fluctuating size of the control region (CR), which ranged from 191 bp in Ablabesmyia sp. 1WL to 1959 bp in Ablabesmyia sp. 3XL (Table 2). All of the newly assembled mitogenomes contained a standard complement of genetic elements, consisting of one control region (CR) and 37 genes. Specifically, these genes encompassed 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and 2 ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), as depicted in Figure 1. Notably, the lengths of the majority of these newly assembled mitogenomes were comparable to those observed in previously published Chironomidae mitogenomes. The sequence characteristics of the represented species are visually summarized in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Nucleotide composition of 17 mitogenomes.

Figure 1.

The mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) map of various representative species spanning four genera within the subfamily Tanypodiinae, highlighting their distinctive attributes. Standard abbreviations are used for protein-coding genes (PCGs) and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), while single-letter abbreviations are employed for transfer RNAs (tRNAs) to ensure clarity. The second concentric circle highlights the GC content of the entire mitogenome, providing insights into its nucleotide composition. The third circle illustrates the GC-skew, offering additional information about the nucleotide distribution. Finally, the innermost circle represents the total length of the mitogenome, providing a comprehensive overview of its characteristics.

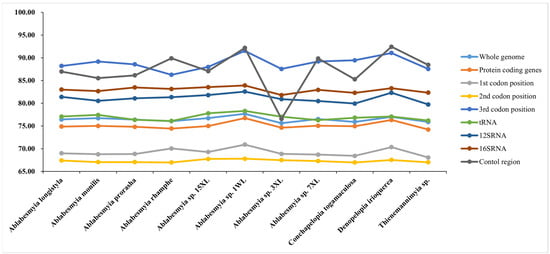

The nucleotide composition of the newly reported mitogenomes demonstrated consistent patterns among the samples, as presented in Table 2, which were characteristic of the AT-bias typical in Chironomidae and other insect lineages. Significant variation was observed in the AT content of the mitochondrial genomes, with values ranging from 74.20% in B. alulasetosa to 78.78% in C. bicinctus (Figure 2 and Table 2). Notably, the control region (CR) exhibited the highest AT content, ranging from 76.57% in A. sp. 3XL to 92.41% in D. irioquerea. In contrast, the AT content in transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and protein-coding genes (PCGs) was relatively lower compared to ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Difference in AT content of protein-coding genes of Tanypodiinae mitogenomes.

All newly assembled mitogenomes displayed a negative GC-skew, indicating a cytosine bias, while most exhibited a positive AT-skew, reflecting an adenine and thymine abundance. The GC-skew ranged from −0.195 in A. sp. 15XL to −0.060 in C. yani. The AT-skew varied from 0.006 in C. bicinctus to 0.051 in A. sp. 3XL, with two exceptions: C. yani and B. kurobebrevis, which displayed negative AT-skews of −0.130 and −0.008, respectively. The GC content itself ranged from 21.22% in C. bicinctus to 25.80% in B. alulasetosa, offering additional insights into the nucleotide composition of these mitogenomes (Table 2).

3.2. Protein-Coding Genes, Codon Usage, and Evolutionary Rates

Among diverse species, no substantial differences were observed in the size of transfer RNA (tRNA), protein-coding genes (PCGs), and ribosomal RNA (rRNA). In particular, the total length of the thirteen PCGs in the acquired mitogenomes varied minimally, ranging between 11,210 and 11,225 base pairs. A comparative analysis of our results with existing Chironomidae data revealed a significant pattern: the adenine–thymine (AT) content at the third codon positions of the PCGs was notably higher compared to those at the first and second positions (Figure 2). Notably, a majority of the seventeen mitogenomes exhibited a negative guanine–cytosine (GC)-skew in their PCGs. Additionally, all these mitogenomes displayed a negative AT-skew in the same genes, with values ranging from −0.195 in B. kurobebrevis to −0.155 in A. sp. 1WL. The AT content percentage varied from 70.90% in B. alulasetosa to 76.73% in A. sp. 1WL, whereas the GC content ranged from 23.27% in A. sp. 1WL to 29.10% in B. alulasetosa (see Table 2 for detailed information).

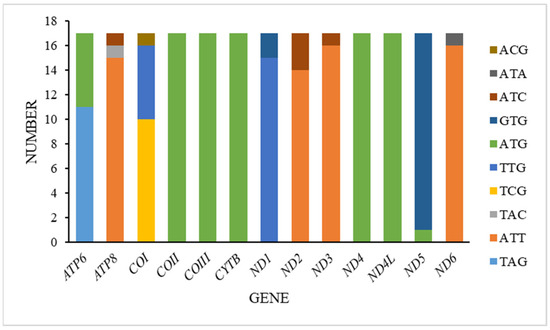

In the mitogenomes we acquired, all thirteen protein-coding genes (PCGs) mostly featured the conventional start codon ATN, aligning closely with the typical mitochondrial start codon observed in insects. However, deviations were noted in other genes. Specifically, the cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) gene utilized TCG as its start codon in ten species, TTG in six species, and ACG in one species. The ATP synthase subunit 8 (ATP8) gene began with ATT in fifteen species and ATC in one species, while the ATP synthase subunit 6 (ATP6) gene started with ATG in all species. The NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (ND1) gene utilized TTG as its start codon in fifteen species and GTG in two species. Similarly, the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2) gene started with ATT in fourteen species and ATC in three species, and the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 3 (ND3) gene began with ATT in sixteen species and ATC in one species. Furthermore, the cytochrome oxidase subunit 2 (COII), cytochrome oxidase subunit 3 (COIII), cytochrome b (CYTB), NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4 (ND4), and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4L (ND4L) genes consistently started with ATG. The NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 (ND5) gene uniquely started with GTG in sixteen species and ATG in one species, while the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 6 (ND6) gene exclusively began with ATT in sixteen species and ATA in one species (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Start codons of protein-coding genes among Tanypodiinae mitogenomes.

Regarding stop codons, the majority of the 13 PCGs primarily utilized TAA. Exceptions included the COI gene with twelve instances of TAA and one TAG, the COIII gene with thirteen TAA, the ND6 gene with one TAA and one TAG, the ND1 gene with one TAG, and the ND4 gene with five TAG instances.

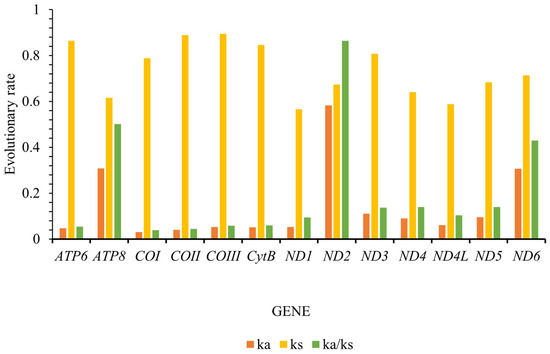

The Ka/Ks ratio, also known as ω, is a widely utilized metric to quantify the rate of sequence evolution in the context of natural selection. Our findings closely mirror those reported for other insect species, demonstrating that the Ka/Ks values for all thirteen protein-coding genes (PCGs) consistently fell below one, with a range spanning from 0.039 for cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI) to 0.864 for NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2) (Figure 4). The evolutionary rates of these PCGs can be ordered as follows: ND2 > ATP8 > ND6 > ND4 > ND5 > ND3 > ND4L > ND1 > CYTB > COIII > ATP6 > COII > COI. Our findings notably demonstrate that many of these genes have evolved under purifying selection, which acts to remove harmful mutations and is influenced by varying selective pressures. Specifically, the low ω values observed for COII and COI indicate a stringent selection environment, suggesting strong evolutionary constraints. In contrast, the higher ω values for ND2, ATP8, and ND6 suggest a more relaxed purifying selection pressure, implying that these genes may be evolving with greater freedom (Figure 4). These insights enhance our understanding of the evolutionary dynamics of these PCGs and the role of natural selection in shaping their sequence evolution.

Figure 4.

Evolutionary rates of the 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs) in Tanypodiinae mitogenomes. Non-synonymous substitutions are denoted as Ka, while synonymous substitutions are represented as Ks. The Ka/Ks ratio indicates the selection pressure on each PCG. The x-axis lists the 13 PCGs, and the y-axis displays the Ka/Ks values.

The lengths of the seventeen mitochondrial tRNAs exhibited considerable variation, ranging from 1480 to 1525 base pairs (bp). The AT content of these tRNAs also showed significant differences, with values spanning from 75.40% in B. alulasetosa to 80.00% in C. bicinctus. Notably, all tRNAs, except for B. kurobebrevis (with an AT-skew of −0.108) and C. bicinctus (with an AT-skew of −0.007), demonstrated a positive AT-skew, with values ranging from 0.008 to 0.049. In contrast to the AT content, the GC content of the tRNAs varied from 20.00% in C. bicinctus to 24.60% in B. alulasetosa. Furthermore, the GC-skew displayed substantial variability, with values ranging from 0.129 in A. prorasha to 0.185 in C. dentatus. These findings highlight the diverse nucleotide compositions and skewness patterns within the mitochondrial tRNAs of the studied species.

Regarding the rRNA sequences, their lengths exhibited considerable variation, ranging from 2161 bp in B. alulasetosa to 2255 bp in A. sp. 1WL. The AT content remained consistently high across all mitogenomes, with values varying between 79.75% and 83.54%. In contrast, the GC content showed a narrower range, spanning from 16.46% to 20.35%. Notably, the GC-skew of all mitogenomes, except for C. yani, which exhibited a negative value of −0.310, was significantly positive, ranging from 0.025 to 0.295. While the majority of mitogenomes demonstrated a negative AT-skew, ranging from −0.028 to −0.001, four species—C. yani, C. bicinctus, B. alulasetosa, and B. kurobebrevis—displayed positive AT-skews, with values of 0.015, 0.002, 0.013, and 0.011, respectively. For a detailed summary of these findings, please refer to Table 2.

3.3. Phylogenetic Relationships

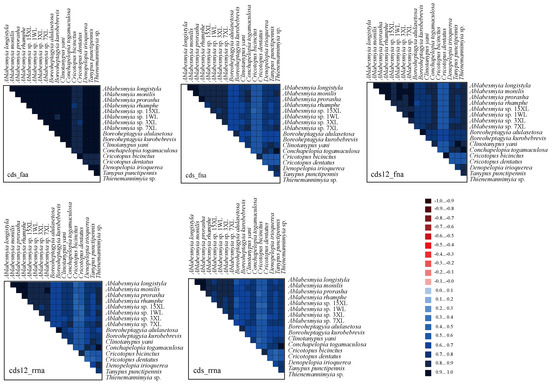

The analysis of heterogeneity divergence differences provides insights into the similarities of mitochondrial gene sequences across various species. Notably, due to the redundancy of the genetic code, the AA dataset exhibited the lowest level of heterogeneity, while the cds12_rrna dataset showed a relatively higher degree of heterogeneity (Figure 5). This indicates that the mutation rate at the third codon position in protein-coding genes (PCGs) exceeds that of the first and second positions. As a result, the third codon positions are deemed unsuitable for inferring phylogenetic relationships within the genus Ablabesmyia. Additionally, the heterogeneity observed in the outgroup species of Cricotopus and Boreoheptagyia is significantly lower than that in the ingroup species.

Figure 5.

The evaluation of heterogeneity among the mitogenomes of 17 species within the subfamily Tanypodiinae focused on their protein-coding genes (PCGs), amino acid sequences, and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs). Sequence similarity was visually depicted using colored blocks, based on AliGROOVE scores that range from −1 (indicating significant heterogeneity between datasets, shown in red) to +1 (indicating minimal heterogeneity, shown in blue). A lighter color in each dataset’s block corresponds to greater heterogeneity, while a darker color indicates lower heterogeneity.

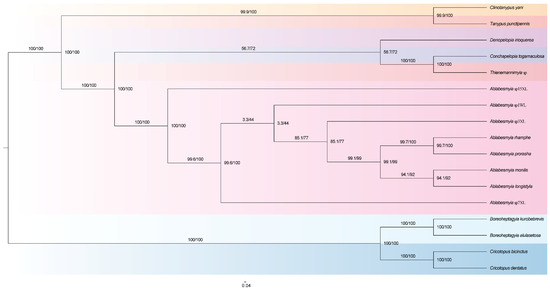

Both Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of these ten datasets consistently identified a similar topological structure across the phylogenetic trees, although there were differences in branch lengths and statistical support values (Figures S1–S9). From the perspective of mitochondrial genomes, the eight species of genus Ablabesmyia identified morphologically are supported as belonging to this genus, and existing data also support the division of this genus into several subgenera (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic ML tree of the genus Ablabesmyia, based on analysis PCG12_rRNA in partition.

The study of the phylogeny of the family Chironomidae has made some progress based on female adults and other morphological characteristics [40,41]. In recent years, the development of molecular biology has enabled further exploration of the phylogenetic relationships within the subfamily Tanypodinae [19]. In the phylogenetic analysis of Chironomidae using molecular data from fragments of 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA, CAD1, CAD4, and mtCOI, analyzed with mixed-model Bayesian and maximum likelihood methods, the results show that Ablabesmyia and Conchapelopia are more closely related and form a sister group with Tanypus, a finding further supported by our research on mitochondrial genomes [19]. Cladistic analyses using 86 morphological characters from 115 species have confirmed that the species Ablabesmyia, Denopelopia, Conchapelopia, and Thienemannimyia are closely related, forming a group referred to as the tribe Pentaneurini, and the tribes Tanypodini + Clinotanypodini are sister groups to the tribe Pentaneurini, which is well supported by mitochondrial genome studies [42]. Incorporating sequence data from mitochondrial COI and nuclear 28S and CAD, Bayesian and maximum likelihood phylogenetic inferences support the view that Ablabesmyia is a terminal group, representing branches or evolutionary stages that appeared later in the evolutionary process, within the tribe Pentaneurini, a finding also reflected in our mitochondrial genome data [43]. To more precisely define and evaluate the phylogenetic relationships within the subfamily Tanypondinae, it is essential to incorporate mitogenomes from a wider variety of species across different genera.

4. Conclusions

Despite the distinct morphological traits observed among the developmental stages—larvae, pupae, and adult males and females—of different genera of Tanypodinae, there is a notable discrepancy between phylogenetic results based on morphology, short gene sequences, and mitochondrial genome data. However, an emerging consensus from molecular phylogenetics underscores the enduring importance of morphological analysis in the study of chironomids. Moreover, while the comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genomes offers exciting possibilities, it requires rigorous examination and careful consideration. A holistic systematic analysis that integrates morphological, biogeographical, and life history traits across various developmental stages of insects, supplemented by genomic data, is essential. Such an integrative approach is likely to illuminate the intrinsic evolutionary connections within the natural world.

For the first time, the mitochondrial genomes of eight species within the genus Ablabesmyia have been meticulously annotated, assembled, and documented. These newly sequenced mitogenomes exhibit structural features and nucleotide compositions that closely align with those of previously reported Chironomidae species, marking a significant expansion of the chironomid mitogenome database. This advancement lays a solid foundation for future phylogenetic studies. The newly sequenced mitogenomes show remarkably similar structural traits and nucleotide compositions, closely matching the data previously published for Chironomidae.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects16020178/s1. Figures S1–S4 present ML phylogenetic trees of the genus Ablabesmyia based on various analyses (cds_faa, cds_rrna, cds12_fna, cds-fna) using the Partition model in IQTREE, with support values indicated by SHaLRT/UFBoot2, respectively. Figures S5–S9 present BI phylogenomic trees of the genus Ablabesmyia based on various analyses (cds_faa, cds_fna, cds_rrna, cds12_fna, cds12_rrna) using the CAT + GTR model in phylobayes, with support values on nodes indicated by Bayesian posterior probabilities. Table S1 presents the final gene partitions for the maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-B.L. and W.-X.P.; Software, Y.-N.T., C.-Y.W. and J.-X.N.; Investigation, Y.-N.T., C.-Y.W. and J.-X.N.; Data curation, W.C., W.-X.P. and Y.-N.T. Writing—original draft, W.-B.L., W.-X.P. and W.C.; Writing—review and editing, C.-C.Y.; Visualization, W.-B.L.; Supervision, C.-C.Y.; Funding acquisition, C.-C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32370489, 32170473) and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin Science and Technology Correspondent (23KPHDRC00240, 22KPXMRC00070).

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding the availability of DNA sequences: The new mitogenomes were deposited in GenBank of the NCBI and the accession numbers are in Table 2.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Xiaolong Lin (Shanghai Ocean University) for providing information on some of the species.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cameron, S.L. Insect mitochondrial genomics: Implications for evolution and phylogeny. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014, 59, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Li, X.; Yin, X.; Li, X.; Yin, J.; Pan, P. The mitochondrial genomes of palaeopteran insects and insights into the early insect relationships. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Li, Y.J.; Ge, X.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Yang, Y.X.; Bai, M.; Ge, S.Q. Mitochondrial genomes of Sternochetus species (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and the phylogenetic implications. Arch. Insect Biochem. 2022, 111, e21898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.T.; Du, Y.Z. Comparison of the complete mitochondrial genome of the stonefly Sweltsa longistyla (Plecoptera: Chloroperlidae) with mitogenomes of three other stoneflies. Gene 2015, 558, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolstenholme, D.R. Animal mitochondrial DNA: Structure and evolution. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1992, 141, 173–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zang, H.; Ye, X.; Peng, L.; Wang, B.; Lian, G.; Sun, C. Comparative Mitogenomic Analyses of Hydropsychidae Revealing the Novel Rearrangement of Protein-Coding Gene and tRNA (Trichoptera: Annulipalpia). Insects 2022, 13, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Li, R.; Zhu, B.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, C. Comparative Mitogenome Analyses of Subgenera and Species Groups in Epeorus (Ephemeroptera: Heptageniidae). Insects 2022, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Y.; Yan, L.P.; Pape, T.; Gao, Y.Y.; Zhang, D. Evolutionary insights into bot flies (Insecta: Diptera: Oestridae) from comparative analysis of the mitochondrial genomes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Peng, L.; Vogler, A.P.; Morse, J.C.; Yang, L.; Sun, C.; Wang, B. Massive gene rearrangements of mitochondrial genomes and implications for the phylogeny of Trichoptera (Insecta). Syst. Entomol. 2023, 48, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Ge, X.; Shi, F.; Wang, L.; Zang, H.; Sun, C.; Wang, B. New Mitogenome Features of Philopotamidae (Insecta: Trichoptera) with Two New Species of Gunungiella. Insects 2022, 13, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, A.; Armitage, P.; Cranston, P.; Pinder, L. The Chironomidae. The Biology and Ecology of Non-biting Midges. J. Anim. Ecol. 1995, 64, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chang, T.; Zhao, K.; Sun, X.; Qiao, H.; Yan, C.; Wang, Y. Genome-wide annotation of cuticular protein genes in non-biting midge Propsilocerus akamusi and transcriptome analysis of their response to heavy metal pollution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Chen, G.; Wang, L.; Lei, T.; Qi, X. DNA Barcoding Supports “Color-Pattern’’-Based Species of Stictochironomus from China (Diptera: Chironomidae). Insects 2024, 15, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrington, L.C. Global diversity of non-biting midges (Chironomidae; Insecta-Diptera) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 2008, 595, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Pei, W.; Ge, X.; Yan, C. Phylogenetic and Comparative Analysis of Cryptochironomus, Demicryptochironomus and Harnischia Inferred from Mitogenomes (Diptera: Chironomidae). Insects 2024, 15, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.L.; Liu, Z.; Yan, L.P.; Duan, X.; Bu, W.J.; Wang, X.H.; Zheng, C.G. Mitogenomes provide new insights of evolutionary history of Boreheptagyiini and Diamesini (Diptera: Chironomidae: Diamesinae). Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, F.X.; Li, X.B.; Aishan, Z.; Lin, X.L. New Mitogenomes of the Polypedilum Generic Complex (Diptera: Chironomidae): Characterization and Phylogenetic Implications. Insects 2023, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinder, L.C.V.; Reiss, F. The Pupae of Chironominae (Diptera: Chironomidae) of the Holarctic Region—Keys and Diagnoses. In Chironomidae of the Holarctic Region. Keys and Diagnoses. Part 2—Pupae; Wiederholm, T., Ed.; Entomologica Scandinavica Supplement: Sandby, Sweden, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cranston, P.; Hardy, N.; Morse, G. A dated molecular phylogeny for the Chironomidae (Diptera). Syst. Entomol. 2011, 37, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashe, P.; O’Connor, J.P. A World Catalogue of Chironomidae (Diptera). Part 1. Buchonomyiinae, Chilenomyiinae, Podonominae, Aphroteniinae, Tanypodinae, Usambaromyiinae, Diamesinae, Prodiamesinae and Telmatogetoninae; Irish Biogeographical Society & National Museum of Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2009; p. 445. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Wang, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W. Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Tanypus chinensis and Tanypus kraatzi (Diptera: Chironomidae): Characterization and Phylogenetic Implications. Genes 2024, 15, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niitsuma, H.; Tang, H. Taxonomic review of Ablabesmyia Johannsen (Diptera: Chironomidae: Tanypodinae) from Oriental China, with descriptions of six new species. Zootaxa 2019, 4564, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stur, E.; da Silva, F.L.; Ekrem, T. Back from the Past: DNA Barcodes and Morphology Support Ablabesmyia americana Fittkau as a Valid Species (Diptera: Chironomidae). Diversity 2019, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.L.D.; Dantas, G.P.D.S.; Hamada, N. Description of immature stages of Ablabesmyia cordeiroi Neubern, 2013 (Diptera: Chironomidae: Tanypodinae). Acta Amaz. 2019, 49, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.A.; Fittkau, E.J. The Adult Males of Tanypodinae (Diptera: Chironomidae) of the Holarctic Region—Keys and Diagnoses. In Chironomidae of the Holarctic Region. Keys and Diagnoses. Part 3. Adult Males; Wiederholm, T., Ed.; Entomologica Scandinavica Supplement: Sandby, Sweden, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fittkau, E.J.; Murray, D.A. The Pupae of Tanypodinae (Diptera: Chironomidae) of the Holarctic Region—Keys and Diagnoses. In Chironomidae of the Holarctic Region. Keys and Diagnoses. Part 2—Pupae; Wiederholm, T., Ed.; Entomologica Scandinavica Supplement: Sandby, Sweden, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, T.; Ekrem, T.; Cranston, P.S. The larvae of the Holarctic Chironomidae (Diptera). Insect Syst. Evol. Suppl. 2013, 66, 1–557. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, X. First report of the complete mitogenome of Tanypus punctipennis Meigen, 1818 (Diptera, Chironomidae) from Hebei Province, China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2022, 7, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierckxsens, N.; Mardulyn, P.; Smits, G.J. NOVOPlasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.G.; Ye, Z.; Zhu, X.X.; Zhang, H.G.; Dong, X.; Chen, P.G.; Bu, W.J. Integrative taxonomy uncovers hidden species diversity in the rheophilic genus Potamometra (Hemiptera: Gerridae). Zool. Scr. 2020, 49, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Le, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.Q. SeqKit: A cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kück, P.; Meid, S.A.; Groß, C.; Wägele, J.W.; Misof, B. AliGROOVE—Visualization of heterogeneous sequence divergence within multiple sequence alignments and detection of inflated branch support. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, M.; Sun, L.; Wang, R.; Li, C.; Gresens, S.; Li, Z.; Lin, X. New mitogenomes from the genus Cricotopus (Diptera: Chironomidae, Orthocladiinae): Characterization and phylogenetic implications. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 115, e22067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæther, O.A. Female Genitalia in Chironomidae and Other Nematocera: Morphology, Phylogenies, Keys; Department of Fisheries and the Environment: Fisheries and Marine Service: Ottawa, Canada, 1977; pp. 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, T.; Mendes, H.F.; Pinho, L.C. Two New Neotropical Chironominae Genera (Diptera: Chironomidae). Chironomus J. Chironomidae Res. 2017, 30, 26–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Ekrem, T. Phylogenetic relationships of nonbiting midges in the subfamily Tanypodinae (Diptera: Chironomidae) inferred from morphology. Syst. Entomol. 2016, 41, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosch, M.; Silva, F.; Ekrem, T.; Baker, A.; Bryant, L.; Stur, E.; Cranston, P. A new molecular phylogeny for the Tanypodinae (Diptera: Chironomidae) places the Australian diversity in a global context. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2022, 166, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).