Simple Summary

This study investigated the biological efficacy of DsCPV-1, a cypovirus strain originally isolated from Dendrolimus sibiricus Tschetv., after passage through the alternative, promising producer host Manduca sexta (L.), to evaluate its potential as a biocontrol agent against two lepidopteran forest pests. Virulence of DsCPV-1 passaged through M. sexta was assessed in the original host (D. sibiricus) and the alternative host (Lymantria dispar) and compared with that of DsCPV-1 passaged through its original host. Polyhedron productivity of DsCPV-1 passaged through M. sexta was examined in D. sibiricus and L. dispar and compared with productivity observed when the DsCPV-1 was passaged in D. sibiricus and M. sexta to determine whether polyhedron formation, and thus transmission potential, is restored. Exposure to DsCPV-1 passaged through M. sexta caused high mortality and polyhedron formation in D. sibiricus, confirming its promise as a biocontrol agent for this pest. In contrast, DsCPV-1 passaged through either D. sibiricus or M. sexta induced no significant mortality in L. dispar, despite viral replication and polyhedron formation, suggesting mid-instar larvae are tolerant to infection. Polyhedron production by DsCPV-1 passaged through M. sexta was restored in D. sibiricus but not in L. dispar.

Abstract

Lymantria dispar (L.) and Dendrolimus sibiricus Tschetv. are lepidopteran forest pest species, with a long history of outbreak dynamics. The recently isolated strain of Cypovirus—Dendrolimus sibiricus cypovirus-1 (DsCPV-1) shows potential as a bioinsecticide against these and other lepidopteran species. Manduca sexta (L.) has been identified as a promising producer of DsCPV-1. Although M. sexta offers clear advantages as an alternative host for DsCPV-1 production, the DsCPV-1 isolate passaged through M. sexta (DsCPV-Ms) produces fewer polyhedra than the original isolate. Here, we evaluated the virulence, recovery of polyhedron formation, and replication of the DsCPV-Ms in L. dispar (alternative host) and D. sibiricus (original host) larvae to assess its suitability as a biocontrol agent in these hosts. Our results demonstrate that DsCPV-Ms causes significant mortality along with efficient polyhedra synthesis in D. sibiricus larvae. In contrast, DsCPV-Ms infection of L. dispar resulted in no significant mortality despite detectable viral replication and polyhedron formation. Polyhedron formation in L. dispar was significantly lower following infection with DsCPV-Ms than with the original isolate, despite confirmed replication of DsCPV-Ms. These findings indicate that DsCPV-Ms remains effective against D. sibiricus; however, further improvements are needed before it can be applied to L. dispar.

1. Introduction

Lymantria dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae), a polyphagous defoliator [], is listed among the world’s top 100 invasive species (“GISD,” n.d.) (accessed on 18 June 2025) and causes extensive damage to broadleaf forests []. Dendrolimus sibiricus Tschetv. (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae) is a conifer pest that leads to large-scale forest damage during population outbreaks across Northern Asia [] and has been identified as a potential emerging invasive pest species, raising concerns about its possible establishment in new regions [,,].

In response to increasing ecological concerns over chemical pesticides, there is growing interest in developing biological control agents that are both effective and environmentally friendly. A recently identified cypovirus strain, Dendrolimus sibiricus Cypovirus-1 (DsCPV-1), has shown promising potential as a biocontrol agent against several lepidopteran pest species, including forest and agricultural pests [], as well as demonstrating biological safety for non-target invertebrates []. This RNA virus, originally isolated from D. sibiricus larvae, belongs to the family Spinareoviridae, genus Cypovirus (ICTV) which is characterized by the production of occlusion bodies (OBs) known as polyhedra []. Polyhedra-forming viruses encapsulate infectious viral particles into OBs and favor their persistence in the environment, especially in soil, until they are consumed by a susceptible insect, remaining infective for long periods during low host population phases (i.e., diapause, seasonal reasons, etc.) [,,].

To facilitate large-scale production of DsCPV-1, an efficient and cost-effective production method is required. Manduca sexta (L.) (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae), one of DsCPV-1’s alternative hosts, is a promising species for in vivo DsCPV-1 production due to its rapid development, low rearing costs during routine farming, ability to support DsCPV-1 replication, and capacity to cause mortality in initial host D. sibiricus larvae [,]. However, the ability of the isolate obtained from M. sexta (hereafter referred to as DsCPV-Ms isolate) to cause mortality in other target lepidopteran species has not been demonstrated and the mortality rate has not been characterized in any study yet. In addition, previous studies have shown that DsCPV-1 passaged through M. sexta exhibits atypical pathogenesis, which is characterized by reduced polyhedra formation when compared to the original isolate obtained from D. sibiricus (DsCPV-Ds isolate) []. Although the reduced number of polyhedra in DsCPV-Ms isolates may potentially be compensated by polyhedra formation in infected larvae treated with this suspension, the ability of lepidopteran larvae to produce polyhedra following DsCPV-Ms infection has not yet been investigated.

Therefore, to assess the potential effectiveness of a bioinsecticide based on DsCPV-1 passaged through the alternative host M. sexta, this study was conducted to evaluate the virulence and polyhedra production of this viral isolate in alternative host larvae against two economically significant forest pest species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insects and DsCPV-1

Fourth-instar larvae of D. sibiricus were collected in the forest-steppe zone of southern Western Siberia (52.039° N, 80.3090° E), Russia. The larvae were reared at +24 °C and 40% to 60% relative humidity under the 16:8 light:dark regime and were fed the shoots of the larch Larix sibirica.

Egg masses of diapausing L. dispar were collected in the Novosibirsk region, Western Siberia (54.2342° N, 82.7614° E), Russia. The eggs were stored at +4 °C throughout the winter diapause. Larval hatching was synchronized with birch leaf budburst (occurring in the first third of May), according to Martemyanov et al., 2015 []. After hatching, the larvae were reared on cut branches of silver birch (Betula pendula Roth) under controlled conditions of +22 °C temperature, natural humidity, and a natural photoperiod.

Polyhedra of DsCPV-Ds were isolated from cadavers of D. sibiricus larvae initially infected by DsCPV-1 isolate according to Martemyanov et al., 2023 []. The DsCPV-Ms suspension was prepared from 20 dead M. sexta larvae infected with the DsCPV-Ds isolate. After removing the cuticle, the internal tissues of the larvae were homogenized, diluted with water, and filtered through a series of gauze to produce a clarified suspension. Final suspension of DsCPV-Ms isolate was 22 mL.

2.2. Challenging D. sibiricus and L. dispar Larvae with DsCPV-1 Isolates

Fifth-instar larvae of D. sibiricus were used for infection with suspension of DsCPV-1-Ms isolate. This suspension was diluted 20-, 200-, 2000- and 20,000-fold, and a volume 10 mL of each dilution was applied by spraying onto branches of larch, dried and were later consumed by D. sibiricus larvae. Mortality was recorded daily for 8 days in both the infected and control groups. Each infected group consisted of three replicates, with 15 larvae per replicate, for a total of 45 larvae per dilution (20-fold, 200-fold, 2000-fold, and 20,000-fold). Similarly, the control group comprised three replicates of 15 untreated larvae each (n = 45). DsCPV-1 infection data for D. sibiricus were obtained from Martemyanov et al., 2023 [].

Third-instar larvae of L. dispar were used for infection with different isolates of DsCPV-1. For DsCPV-Ds suspension, concentration was 5 × 107 polyhedra/mL. We also used a 20-fold dilution of DsCPV-1-Ms isolate to infect L. dispar larvae, as its virulence in D. sibiricus larvae was shown to be equivalent to that of a 5 × 107 polyhedra/mL (Martemyanov et al., 2023 [] and this study). Both suspensions, with a volume 10 mL, were applied by spraying onto branches of B. pendula, which were dried and later consumed by L. dispar larvae. Mortality was recorded daily for 14 days in both the infected and control groups. Each group consisted of five replicates with 10 larvae per replicate, resulting in a total of 50 larvae per group (n = 50).

Dead larvae of D. sibiricus infected with the DsCPV-Ms isolate and of L. dispar infected with both the DsCPV-Ds and DsCPV-Ms isolates were individually homogenized using a polyurethane pestle. The polyhedra productivity of the DsCPV-1 isolates was estimated with light microscopy (400×) using a hemocytometer.

2.3. qPCR Assay

qPCR was applied to confirm DsCPV-1 replication in L. dispar larvae infected with DsCPV-Ds and DsCPV-Ms. For this analysis, five randomly selected infected larvae were dissected and their gut tissues collected on day 1, and an additional set of five asymptomatic infected larvae were sampled on day 14, from both isolates. These were not the same larvae as those in the mortality group, as we maintained a separate larval group to prevent sample depletion due to sampling. Total RNA was extracted using the Lira-reagent (BioLabMix, Novosibirsk, Russia), followed by reverse transcription using the RT-M-MuLV-RH kit (BioLabMix, Novosibirsk, Russia) and qPCR using the BioMaster HS-qPCR SYBR Blue kit (BioLabMix, Novosibirsk, Russia), according to Subbotina et al., 2025 []. The primers used for amplification of the DsCPV-1 polyhedrin gene were designed as follows (5′–3′): forward primer, TCTCACCGAATGCTTACCCA; reverse primer, AGAGCGTCACCCTATCCGAA. To enable accurate comparison of Cq values, the extracted RNA samples were diluted identically, according to Belevich et al., 2024 [].

To determine the viral load in the DsCPV-Ms isolate, a 50 μL aliquot of a 20-fold dilution of the DsCPV-Ms suspension was processed for RNA isolation. RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and amplification were performed using the same protocols as those applied to larval intestinal samples. For the standard curve, a pAL2-T plasmid vector containing a fragment of the polyhedrin gene (GenBank: OL774561.1) was constructed. The 153 bp fragment (sequence: 5′-TCTCACCGAATGCTTACCCATACCTCGACATCAATAACCATAGCTATGGAGTAGCTCTGAGTAACCATCAGTGATTGCTCGTGTAACTTGGATACCAGAAAACATGACGCCGTGATGAATTACGCGCCCGGTCTTCGGATAGGGTGACGCTCT-3′) was amplified using the same primers and qPCR protocol described in Subbotina et al., 2025 [], and subsequently cloned into the pAL2-T vector using the Quick-TA Cloning Kit (Evrogen, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The ligation product was chemically transformed into XL1-Blue competent cells (Evrogen, Russia), and transformants were cultured for 12 h at 37 °C. Plasmid DNA was isolated with the Plasmid-10-Mini Kit (Biolabmix, Russia) in accordance with the kit protocol. A standard curve was generated using serial 2-fold dilutions of the pAL2-T plasmid vector containing a polyhedrin gene insert, with a known copy number per PCR reaction: DNA (copy) = (6.02 × 1023(copy/mol) × DNA concentration(g/μL))/(Mvector with insert(g/mol)) []. The copy number per mL of the original suspension was then calculated by accounting for sample dilution factors and volume of aliquot of suspension.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Mortality in groups of D. sibiricus and L. dispar larvae, polyhedra productivity and qPCR data in groups of L. dispar larvae were tested using a Mann–Whitney U test (Statistica 6.0). Polyhedra productivity in D. sibiricus larva was tested using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (in PAST 3). Data were preliminarily checked for outliers.

3. Results

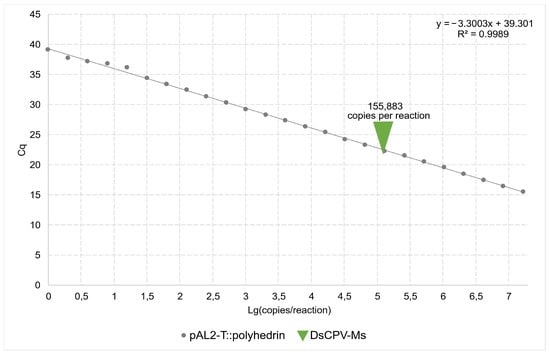

The viral load of the DsCPV-Ms isolate was quantified by qPCR using a standard calibration curve (y = −3.3003x + 39.301; Figure 1). The copy number in the DsCPV-Ms suspension sample was 155,883 copies per PCR reaction. After accounting for dilution factors and sample volume, the viral titer in the DsCPV-Ms suspension was calculated as 3.0 × 108 copies/mL.

Figure 1.

Quantitative PCR for the pAL2-T plasmid vector carrying a polyhedrin gene insert and DsCPV-Ms suspension samples.

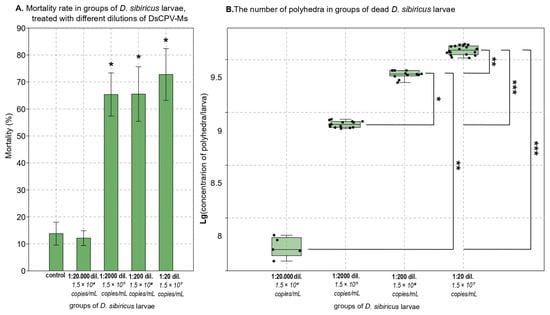

Subsequently, 20-fold, 200-fold, 2000-fold, and 20,000-fold dilutions of this DsCPV-Ms suspension were used to infect D. sibiricus, and the 20-fold dilution was used to infect L. dispar. The corresponding viral concentrations were as follows: 20-fold dilution—1.5 × 107 copies/mL, 200-fold—1.5 × 106 copies/mL, 2000-fold—1.5 × 105 copies/mL, and 20,000-fold—1.5 × 104 copies/mL (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2.

(A): * p < 0.05 versus the control (Mann–Whitney U test). (B): Brackets indicate pairs of groups with statistically significant differences (Dunn’s post hoc test); asterisks denote significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Exposure to the 20-fold dilution of DsCPV-Ms isolate resulted in 72.8% mortality (control vs. infected: Z = −1.964, p = 0.049; Mann–Whitney U test); 65.6% at the 200-fold dilution (control vs. infected: Z = −1.964, p = 0.049), 65.4% at the 2000-fold dilution (control vs. infected: Z = −1.964, p = 0.049) and 12.1% at the 20,000-fold dilution in D. sibiricus larvae (control vs. infected: Z = 0.00, p = 1.00; Mann–Whitney U test; Figure 2A).

In dead DsCPV-Ms infected D. sibiricus larvae, polyhedra were detected by light microscopy. For 20-fold dilution of DsCPV-Ms isolate, the median productivity in five-instar larvae was 3.9 × 109 polyhedra/larvae with a range of 3.3 × 109 to 4.4 × 109; for 200-fold dilution—2.3 × 109 polyhedra/larvae with a range of 1.9 × 109 to 2.5 × 109; for 2000-fold dilution—7.7 × 108 polyhedra/larvae with a range of 7.0 × 108 to 8.6 × 108; for 20,000-fold dilution—5.0 × 107 polyhedra/larvae with a range of 3.9 × 107 to 6.9 × 107 (Kruskal–Wallis test: H(3, N=49) = 43.79008, p < 0.001; see results of Dunn’s post hoc test on Figure 2B).

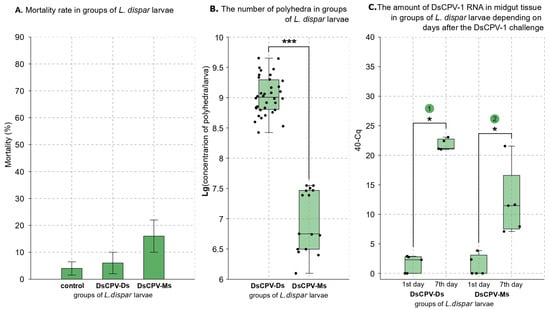

To infect L. dispar larvae, we used a concentration of 5 × 107 polyhedra per milliliter for DsCPV-Ds suspension and a 20-fold dilution of stock DsCPV-Ms. These concentrations were selected because they demonstrated comparable virulence effects in studies: against L. dispar (Martemyanov et al., 2023 []) and D. sibiricus (this study). No significant differences in mortality were observed between the control and infected larvae in this experiment (control vs. infected of DsCPV-Ds: Z = −0.209, p = 0.811; control vs. infected of DsCPV-Ms: Z = −1.462, p = 0.118; Mann–Whitney U test; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A): * p < 0.05 versus the control (Mann–Whitney U test). (B): Brackets indicate comparable groups; asterisks denote significant differences between those groups: *** p < 0.001 (Mann–Whitney U test). (C): Brackets indicate comparable groups; asterisks denote significant differences between those groups: * p < 0.05 (Mann–Whitney U test); 1. p = 0.012, 2. p = 0.011 (Mann-Whitney U test).

In L. dispar larvae infected with both viral isolates, polyhedra were successfully detected by light microscopy. The proportion of samples in which polyhedra were observed was higher in larvae infected with the DsCPV-Ds isolate (90.7%) compared to those infected with the DsCPV-Ms isolate (41.0%). The median productivity of polyhedra during infection significantly differs between the two isolates. For the DsCPV-Ds isolate, the median yield was 1 × 109 polyhedra/larva, with a range of 2.7 × 108 to 4.5 × 109, while DsCPV-Ms isolate exhibited a lower median productivity of 5.6 × 106 polyhedra/larva, with a range of 1.2 × 106 to 3.5 × 107 polyhedra/larva (Z = 5.581942, p < 0.001; Mann–Whitney U test; Figure 3B).

To confirm DsCPV-1 replication in L. dispar larvae infected with DsCPV-Ds and DsCPV-Ms isolates, qPCR was performed, as no significant mortality was observed in the DsCPV-Ds treated group, and neither significant mortality nor polyhedron formation was detected in most individuals from the DsCPV-Ms-treated group. Using the comparative Cq method with equally diluted samples [], we demonstrated that the amount of DsCPV-1 dsRNA significantly increased over the infection in larvae infected with DsCPV-Ds isolate compared to the control group (Z = 2.5143, p = 0.012; Mann–Whitney U test; Figure 3C), as well as in those infected with DsCPV-Ms isolate compared to the control group (Z = 2.5377, p = 0.011; Mann–Whitney U test; Figure 3C).

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate high mortality in fifth-instar larvae of D. sibiricus (72.8%) following infection with the 20-fold dilution of DsCPV-1 passaged through M. sexta (i.e., DsCPV-Ms), confirming its strong virulence and potential as a biocontrol agent against D. sibiricus. This is particularly advantageous, as rearing D. sibiricus for virus production is constrained by its prolonged life cycle, lasting two to five years [], and its strictly seasonal availability, whereas M. sexta can be cultured (or even farmed) year-round under standard conditions and supported reliable viral amplification. In addition, based on mortality data from D. sibiricus infections with the DsCPV-Ms isolate and our previous studies, we selected a 20-fold dilution of the DsCPV-Ms as the pathogenic equivalent of 5 × 107 polyhedra/mL of the DsCPV-Ds for infecting L. dispar. We selected treatment concentrations based on their biological effect, not the number of virus particles. This way, we compared polyhedron production in L. dispar under equally pathogenic conditions, an approach that better approximates conditions expected in future field applications.

In our previous study, we showed that polyhedron productivity in middle-instar D. sibiricus larvae infected with original DsCPV-1 suspension at a concentration of 2 × 107 polyhedra/mL averaged 1.0 × 108 polyhedra per larva, with a range of 2.5 × 107 to 3.1 × 108 []. In the current study, D. sibiricus larvae infected with DsCPV-Ms isolate exhibited high levels of polyhedron formation across all treatment concentrations (medians ranging from 3.9 × 107 to 5.0 × 109 polyhedra per larva), which were comparable to or exceeded polyhedron productivity observed in the previous DsCPV-Ds infection. The higher yields may be attributed to the use of later-instar larvae in the present study, as larger larvae tend to produce more polyhedra [,]. Nevertheless, these results suggest that polyhedron formation is restored in the original host D. sibiricus infected with the DsCPV-Ms isolate and reaches levels comparable to those observed in D. sibiricus larvae infected with original DsCPV-1. A similar phenomenon—restoration of polyhedron formation upon reverse passage through the insect host—is observed in baculoviruses, which exhibit a “passage effect” characterized by reduced polyhedron production and infectivity following prolonged propagation in cell culture [,,,]. Despite their phylogenetic divergence, baculoviruses and cypoviruses have functional and evolutional parallels in polyhedron formation []. Thus, shifts in dominant phenotypes induced by intrahost bottlenecks could underlie polyhedron loss and recovery in both groups [,]. Although the specific mechanisms driving the emergence of polyhedron-free phenotypes in the DsCPV-Ms isolate (genetic or host-mediated) remain unknown. In the context of future application of the DsCPV-Ms as a biological control agent, the restoration of high-level polyhedron production will allow for the persistence of a large number of viral particles in the environment, thereby reducing the concentration needed for subsequent treatments.

Although previous studies demonstrated substantial mortality rates in second-instar L. dispar larvae (72.5%) following exposure to 107 polyhedra/mL of the DsCPV-1 [] and 33.5% mortality following exposure to 106 polyhedra/mL of DsCPV-1 [], as well as 72.8% mortality in late-instar D. sibiricus larvae after DsCPV-Ms treatment (current study), the present study failed to detect any significant differences in mortality among L. dispar groups treated with either viral passage compared to the control group. Despite this viral replication occurs in both infected groups, as evidenced by both microscopy screening of polyhedra and qPCR analysis. The absence of significant mortality despite confirmed infection in experimental L. dispar larvae suggests the presence of tolerance, defined as the ability to mitigate the negative effects of a pathogen on host fitness without reducing pathogen load, rather than resistance, which involves suppressing pathogen replication or accumulation [,,].

No significant mortality was observed in L. dispar larvae infected with DsCPV-Ds isolate compared to the control group. Given that the same viral suspension caused high mortality in younger larvae in our previous study [], the current results could indicate an age-related reduction in sensitivity. A similar instar-dependent effect has been demonstrated in Spodoptera exigua larvae infected with a Cypovirus []. Numerous studies have documented age-associated increases in non-specific immune parameters, both basally [,] and when stimulated by various pathogens [,], specifically in Lepidoptera [,,] and in L. dispar [,,]. Since the primary target tissue of Cypovirus is the midgut [], enhanced intestinal defense mechanisms may contribute to tolerance of L. dispar larvae to DsCPV-1 infection [,]. One plausible mechanism involves the exfoliation of midgut epithelium during molting processes [,] and through cell proliferation [,,], which could potentially provide healthy cells for organismal survival. However, this hypothesis requires further experimental validation. This could be addressed by implementing earlier treatments to target the most sensitive developmental stages, along with the addition of biologically active compounds such as optical brighteners, which have demonstrated their effectiveness in reducing lethal doses of Cypovirus in L. dispar [] and other viruses in lepidopteran insects [,,].

Polyhedron formation was observed in groups of L. dispar larvae infected with both isolates. While the extent of polyhedron formation varied significantly across isolates, the use of biological effect-based normalization, rather than quantification relative to infectious particle input, precludes definitive conclusions regarding whether these differences in polyhedron formation arise from variations in initial viral entry or post-entry replication dynamics. Notably, a substantial proportion (59%) of individuals infected with the DsCPV-Ms isolate failed to produce detectable polyhedra in L. dispar, despite positive qPCR signals confirming viral replication. This phenotype closely resembles the infection pattern previously reported in M. sexta []. While we observed polyhedron restoration in the original host, D. sibiricus, likely due to selection pressure favoring polyhedron-forming variants, as they are more readily transmitted within the original host population [,], this pressure apparently does not occur in the alternative host, L. dispar.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that DsCPV-1 passaged through M. sexta retains high virulence and efficient polyhedron production, which preserves its transmission potential in D. sibiricus populations. These findings highlight DsCPV-Ms isolate of DsCPV-1 promise as a biologically effective agent for the control of D. sibiricus. In contrast, although DsCPV-1 replicates in L. dispar, neither DsCPV-Ds nor DsCPV-Ms infection resulted in significant mortality of middle instar larvae, a pattern that may reflect age-related insensitivity. Furthermore, reduced polyhedra formation following DsCPV-Ms indicates a failure to restore occlusion body production after passage through M. sexta. Thus, although DsCPV-1 passaged through M. sexta retains high virulence and efficient polyhedron production in its original host, D. sibiricus, its application against alternative hosts such as L. dispar requires further optimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization V.V.M. and A.O.S.; formal analysis A.O.S.; funding acquisition V.V.M.; investigation A.O.S., Y.B.A., B.S.K., S.S.M. and A.V.K.; methodology A.O.S. and E.L.A.; project administration V.V.M.; resources A.V.K. and V.V.M.; Supervision E.L.A. and I.A.B.; visualization A.O.S.; writing—original draft A.O.S.; writing—review and editing V.V.M. and A.O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the State Program of the “Sirius” Federal Territory “Scientific and Technological Development of the ‘Sirius’ Federal Territory” (Agreement No. 24-03 from 27 September 2024) for infection of L. dispar and qPCR assay, and the Federal Fundamental Scientific Research Program for 2021–2025 (FWGS-2021-0003) for dose-dependent infection of D. sibiricus.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pogue, M. A Review of Selected Species of Lymantria Hübner (1819) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae: Lymantriinae) from Subtropical and Temperate Regions of Asia, Including the Descriptions of Three New Species, Some Potentially Invasive to North America; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boukouvala, M.C.; Kavallieratos, N.G.; Skourti, A.; Pons, X.; Alonso, C.L.; Eizaguirre, M.; Fernandez, E.B.; Solera, E.D.; Fita, S.; Bohinc, T.; et al. Lymantria dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae): Current Status of Biology, Ecology, and Management in Europe with Notes from North America. Insects 2022, 13, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranchikov, Y.N. Siberian Moth-a Relentless Modifier of Taiga Forest Ecosystems in Northern Asia; Siberian Federal University: Krasnoyarsk, Russia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Möykkynen, T.; Pukkala, T. Modelling of the Spread of a Potential Invasive Pest, the Siberian Moth (Dendrolimus sibiricus) in Europe. For. Ecosyst. 2014, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flø, D.; Rafoss, T.; Wendell, M.; Sundheim, L. The Siberian Moth (Dendrolimus sibiricus), a Pest Risk Assessment for Norway. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.; Djoumad, A.; Holden, D.; Kimoto, T.; Capron, A.; Dubatolov, V.V.; Akhanaev, Y.B.; Yakimova, M.E.; Martemyanov, V.V.; Cusson, M. A TaqMan Assay for the Detection and Monitoring of Potentially Invasive Lasiocampids, With Particular Attention to the Siberian Silk Moth, Dendrolimus sibiricus (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae). J. Insect Sci. Online 2023, 23, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martemyanov, V.V.; Akhanaev, Y.B.; Belousova, I.A.; Pavlusin, S.V.; Yakimova, M.E.; Kharlamova, D.D.; Ageev, A.A.; Golovina, A.N.; Astapenko, S.A.; Kolosov, A.V.; et al. A New Cypovirus-1 Strain as a Promising Agent for Lepidopteran Pest Control. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0385522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belevitch, O.; Yurchenko, Y.; Kharlamova, D.; Shatalova, E.; Agrikolyanskaya, N.; Subbotina, A.; Ignatieva, A.; Tokarev, Y.; Martemyanov, V. Ecological Safety of Insecticide Based on Entomopathogenic Virus DsCPV-1 for Nontarget Invertebrates. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloncik, S.; Mori, H. Cypoviruses. In The Insect Viruses; Miller, L.K., Ball, L.A., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 337–369. ISBN 978-1-4615-5341-0. [Google Scholar]

- Maramorosch, K. Viral Insecticides for Biological Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-0-323-14237-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hukuhara, T.; Wada, H. Adsorption of Polyhedra of a Cytoplasmic-Polyhedrosis Virus by Soil Particles. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1972, 20, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. Soil as an Environmental Reservoir for Baculoviruses: Persistence, Dispersal and Role in Pest Control. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbotina, A.O.; Martemyanov, V.V.; Belousova, I.A. Atypical Pathogenesis of DsCPV-1 in Candidate for Mass Production Manduca sexta (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2025, 118, 1436–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martemyanov, V.V.; Pavlushin, S.V.; Dubovskiy, I.M.; Yushkova, Y.V.; Morosov, S.V.; Chernyak, E.I.; Efimov, V.M.; Ruuhola, T.; Glupov, V.V. Asynchrony between Host Plant and Insects-Defoliator within a Tritrophic System: The Role of Herbivore Innate Immunity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Shin, S.G.; Hwang, S. Absolute and Relative QPCR Quantification of Plasmid Copy Number in Escherichia Coli. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 123, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, N.; Flament, J.; Baranchikov, Y.; Grégoire, J.-C. Larval Performances and Life Cycle Completion of the Siberian Moth, Dendrolimus sibiricus (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae), on Potential Host Plants in Europe: A Laboratory Study on Potted Trees. Eur. J. For. Res. 2011, 130, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teakle, R.E.; Byrne, V.S. Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus Production in Heliothis Armigera Infected at Different Larval Ages. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1989, 53, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardi, F.; Leite, L.G.; Zamataro, C.E. Production of Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus of Anticarsia gemmatalis Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae): Effect of Virus Dosage, Host Density and Age. An. Soc. Entomol. Bras. 1997, 26, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beames, B.; Summers, M.D. Location and Nucleotide Sequence of the 25K Protein Missing from Baculovirus Few Polyhedra (FP) Mutants. Virology 1989, 168, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krell, P.J. Passage Effect of Virus Infection in Insect Cells. Cytotechnology 1996, 20, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavicek, J.M.; Hayes-Plazolles, N.; Kelly, M.E. Identification of a Lymantria dispar Nucleopolyhedrovirus Isolate That Does Not Accumulate Few-Polyhedra Mutants during Extended Serial Passage in Cell Culture. Biol. Control 2001, 22, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, J.C.; Godfray, H.C.J.; O’Reilly, D.R. A Few-Polyhedra Mutant and Wild-Type Nucleopolyhedrovirus Remain as a Stable Polymorphism during Serial Coinfection in Trichoplusia Ni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 2052–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Axford, D.; Owen, R.; Evans, G.; Ginn, H.M.; Sutton, G.; Stuart, D.I. Polyhedra Structures and the Evolution of the Insect Viruses. J. Struct. Biol. 2015, 192, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwart, M.P.; Elena, S.F. Matters of Size: Genetic Bottlenecks in Virus Infection and Their Potential Impact on Evolution. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2015, 2, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrone, J.T.; Lauring, A.S. Genetic Bottlenecks in Intraspecies Virus Transmission. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2018, 28, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhanaev, Y.B.; Pavlushin, S.V.; Kharlamova, D.D.; Odnoprienko, D.; Subbotina, A.O.; Belousova, I.A.; Ignatieva, A.N.; Kononchuk, A.G.; Tokarev, Y.S.; Martemyanov, V.V. The Impact of a Cypovirus on Parental and Filial Generations of Lymantria dispar L. Insects 2023, 14, 917. Insects 2023, 14, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, J.S.; Schneider, D.S. Tolerance of Infections. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.V.L.; Cotter, S.C. Resistance and Tolerance: The Role of Nutrients on Pathogen Dynamics and Infection Outcomes in an Insect Host. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lissner, M.M.; Schneider, D.S. The Physiological Basis of Disease Tolerance in Insects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 29, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Sun, X.; TANG, X.; PENG, H. Producing Dendrolimus Punctatus Cytoplasmic Polyhedrosis Virus in Substitutive Host Spodoptera Exigua *: Producing Dendrolimus Punctatus Cytoplasmic Polyhedrosis Virus in Substitutive Host Spodoptera Exigua. Chin. J. Appplied Environ. Biol. 2010, 16, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerofsky, M.; Harel, E.; Silverman, N.; Tatar, M. Aging of the Innate Immune Response in Drosophila Melanogaster. Aging Cell 2005, 4, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelweith, F.; Foitzik, S.; Meunier, J. Age, Sex, Mating Status, but Not Social Isolation Interact to Shape Basal Immunity in a Group-Living Insect. J. Insect Physiol. 2017, 103, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, L.D.; Houck, M.A. The Immune Response of Larvae and Pupae of Calliphora vicina (Diptera: Calliphoridae), upon Administered Insult with Escherichia coli. J. Med. Entomol. 2002, 39, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, B.A.; Washburn, J.O.; Volkman, L.E. AcMNPV Pathogenesis and Developmental Resistance in Fifth Instar Heliothis Virescens. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1998, 72, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monobrullah, M.; Nagata, M. Effect of Larval Age on Susceptibility of Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to Spodoptera litura Multiple Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus. Can. Entomol. 2000, 132, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhard, E.K.; Volkman, L.E. Developmental Resistance in Fourth Instar Trichoplusia Ni Orally Inoculated with Autographa Californica M Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus. Virology 1995, 209, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, M.; Hoover, K. Intrastadial Developmental Resistance of Third Instar Gypsy Moths (Lymantria dispar L.) to L. dispar Nucleopolyhedrovirus. Biol. Control 2007, 40, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, J.; Cox-Foster, D.; Gardner, M.; Slavicek, J.; Thiem, S.; Hoover, K. Pathogenesis of Lymantria dispar Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus in L. dispar and Mechanisms of Developmental Resistance. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 1590–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, J.; Cox-Foster, D.; Slavicek, J.; Hoover, K. Contributions of Immune Responses to Developmental Resistance in Lymantria dispar Challenged with Baculovirus. J. Insect Physiol. 2010, 56, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, N.; Hou, C.; Gao, K.; Tang, X.; Guo, X. Analysis of Reassortant and Intragenic Recombination in Cypovirus. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awais, M.M.; Fei, S.; Xia, J.; Feng, M.; Sun, J. Insights into Midgut Cell Types and Their Crucial Role in Antiviral Immunity in the Lepidopteran Model Bombyx Mori. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1349428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, K.; Washburn, J.O.; Volkman, L.E. Midgut-Based Resistance of Heliothis Virescens to Baculovirus Infection Mediated by Phytochemicals in Cotton. J. Insect Physiol. 2000, 46, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, I.T.; Schultz, J.C. Rapid Changes in Tree Leaf Chemistry Induced by Damage: Evidence for Communication between Plants. Science 1983, 221, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzetti, E.; Casartelli, M.; D’Antona, P.; Montali, A.; Romanelli, D.; Cappellozza, S.; Caccia, S.; Grimaldi, A.; de Eguileor, M.; Tettamanti, G. Midgut Epithelium in Molting Silkworm: A Fine Balance among Cell Growth, Differentiation, and Survival. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2016, 45, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagnola, A.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L. Intestinal Regeneration as an Insect Resistance Mechanism to Entomopathogenic Bacteria. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2016, 15, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuno, S.; Takatsuka, J.; Nakai, M.; Ototake, S.; Masui, A.; Kunimi, Y. Viral-Enhancing Activity of Various Stilbene-Derived Brighteners for a Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Nucleopolyhedrovirus. Biol. Control 2003, 26, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukawa, S.; Nakai, M.; Okuno, S.; Takatsuka, J.; Kunimi, Y. Nucleopolyhedrovirus Enhancement by a Fluorescent Brightener in Mythimna separata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2003, 38, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).