Low Natural Parasitism of the Invasive Halyomorpha halys Versus Strong Native Suppression of Palomena prasina: Evidence from a Three-Year Survey in Northwestern Türkiye

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Naturally Laid Egg Masses of GSB and BMSB

2.2. Rearing and Observation of GSB and BMSB Egg Masses in the Laboratory

2.3. Determination of Egg Parasitoid Performance

2.4. Identification of Parasitoids

3. Results

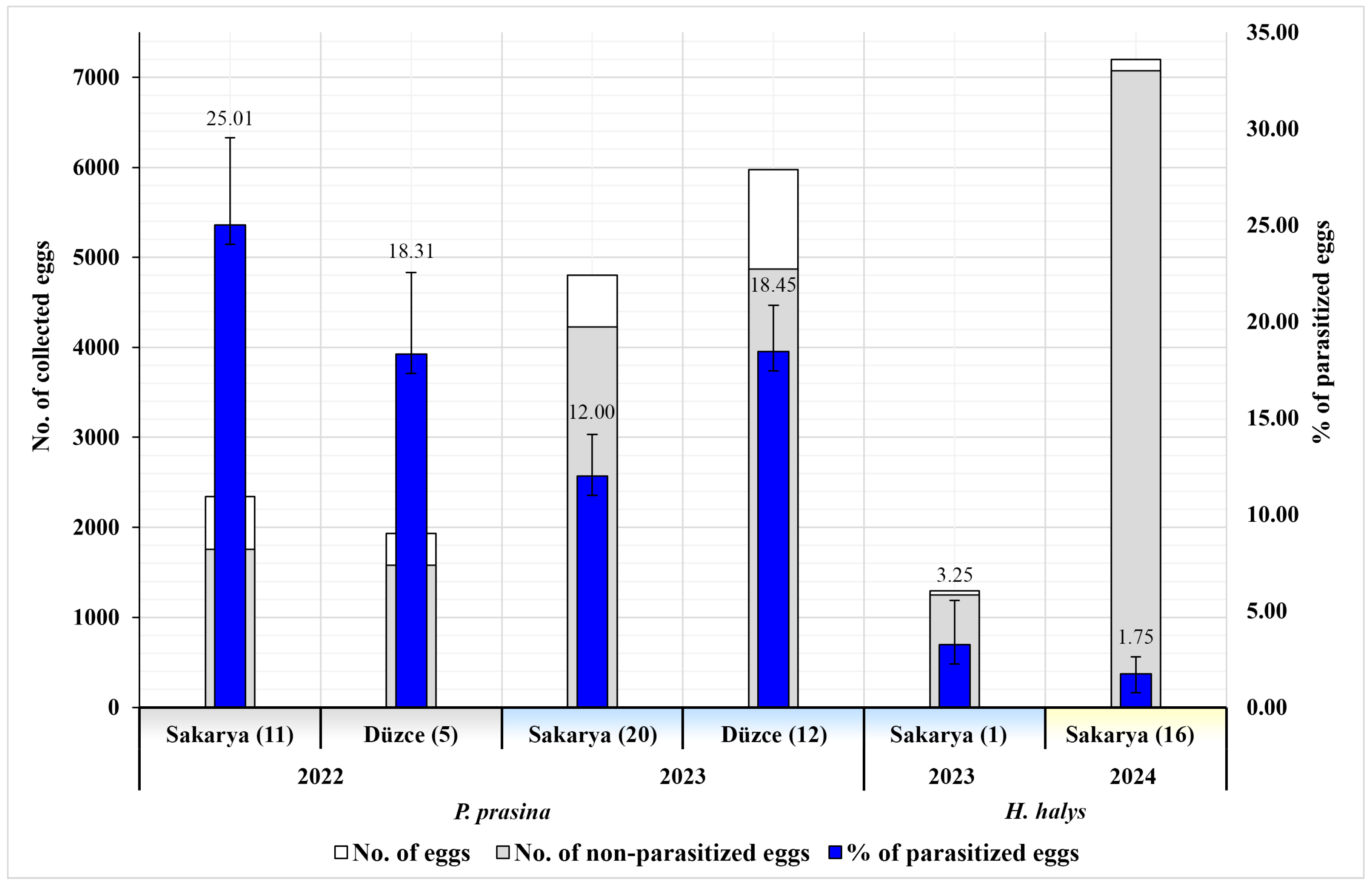

3.1. Egg Status and Parasitism Rates

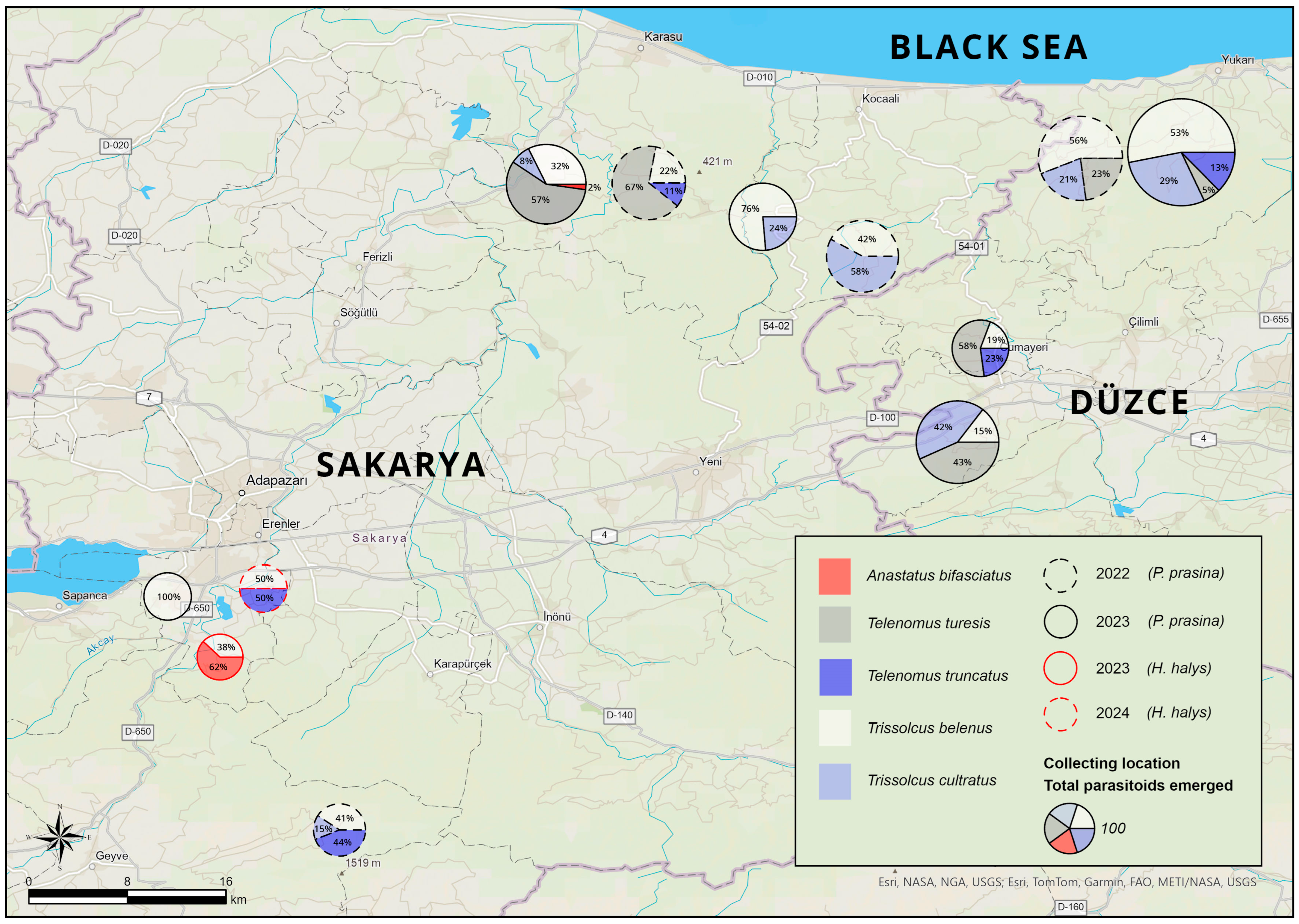

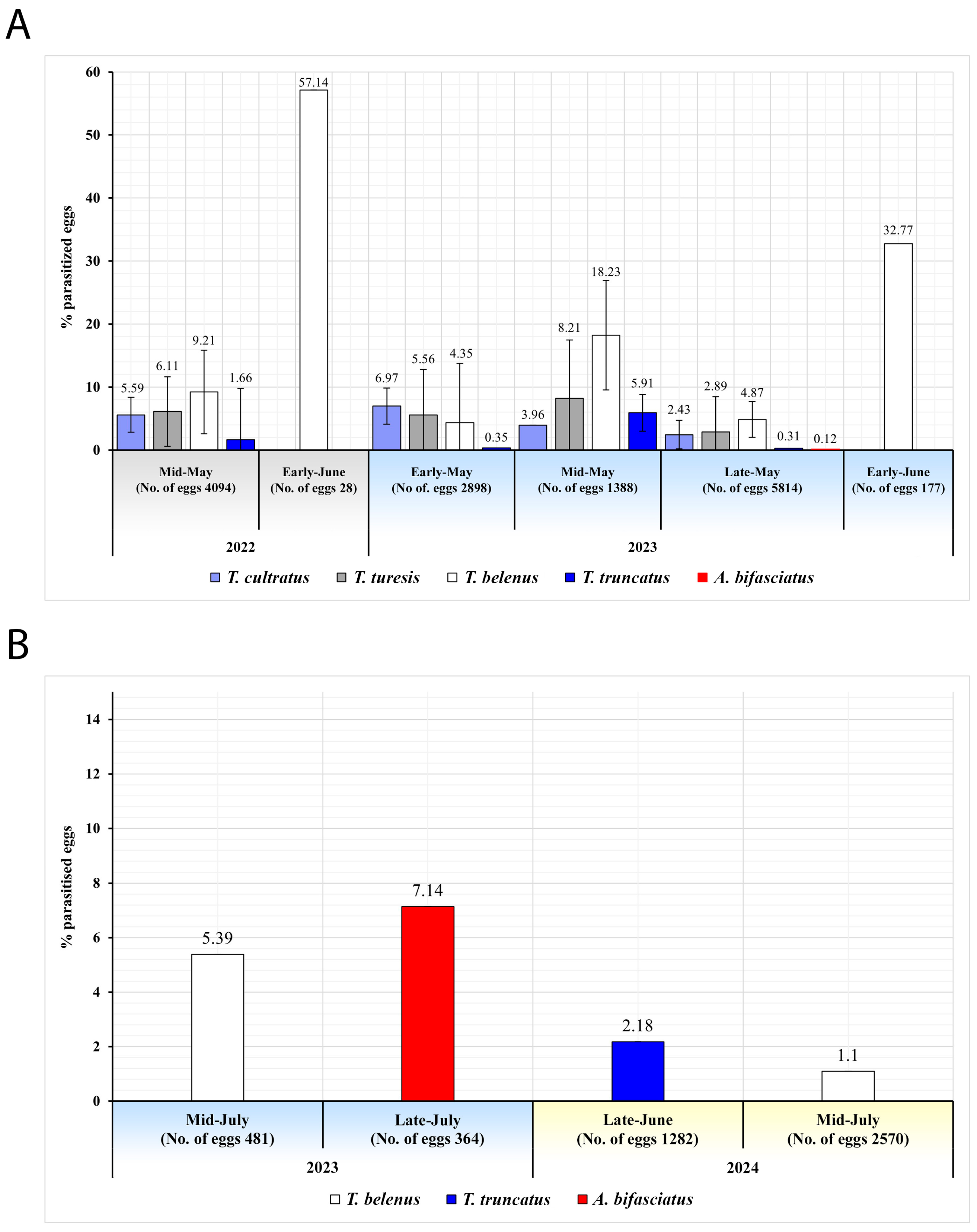

3.2. Species Composition of Egg Parasitoids

3.3. Molecular Confirmation of Parasitoid Identification

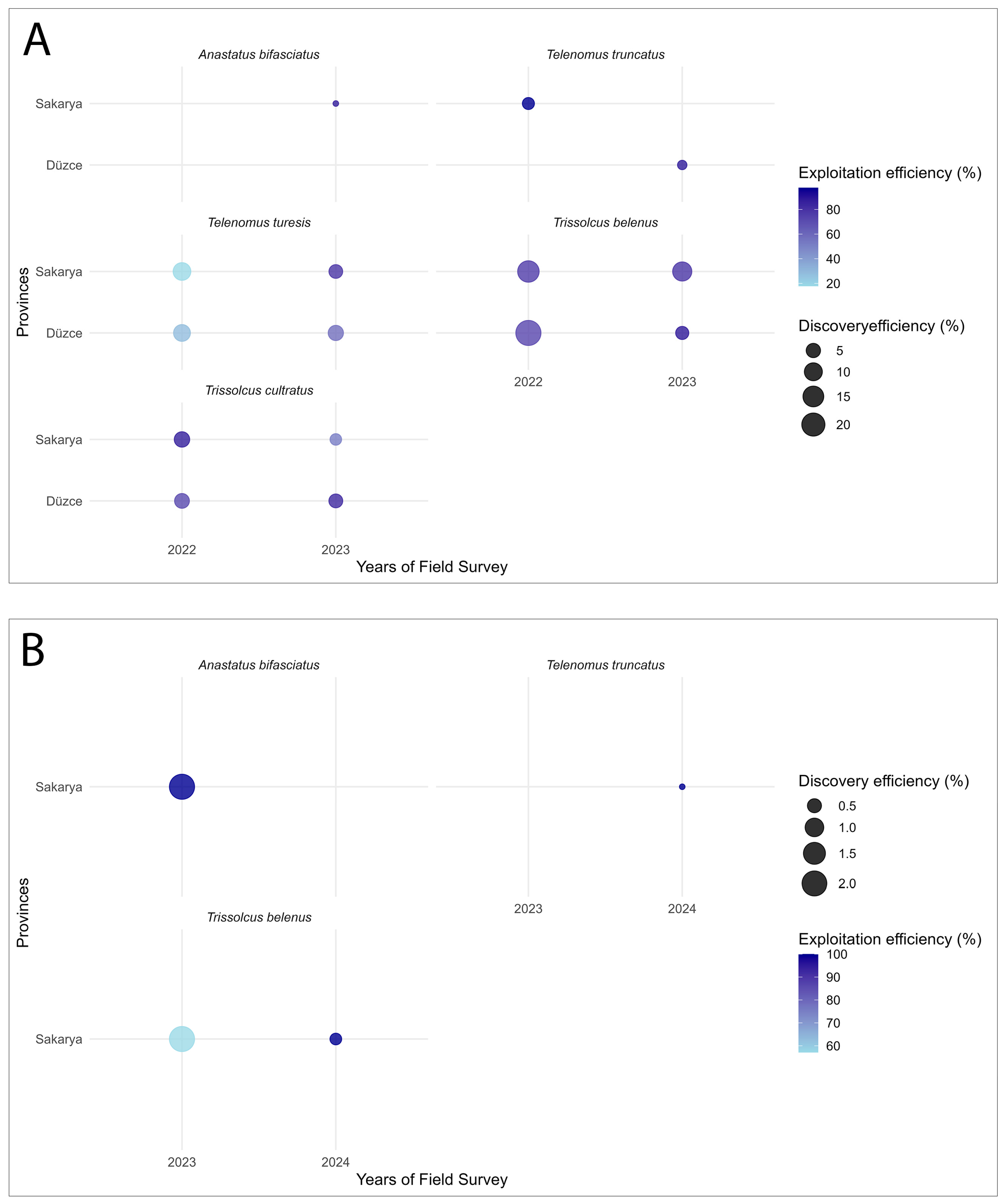

3.4. Discovery and Exploitation Efficiencies of Egg Parasitoids

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Panizzi, A.R.; McPherson, J.E.; James, D.G.; Javahery, M.; McPherson, R.M. Stink Bugs (Pentatomidae). In Heteroptera of Economic Importance; Schaefer, C.W., Panizzi, A.R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; pp. 421–474. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, J.E.; McPherson, R.M. Stink Bugs of Economic Importance in America North of Mexico; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, J.E. Invasive Stink Bugs and Related Species (Pentatomoidea): Biology, Higher Systematics, Semiochemistry, and Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarczyk, E.E.; Cottrell, T.E.; Tillman, G. Characterizing the spatiotemporal distribution of three native stink bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) across an agricultural landscape. Insects 2021, 12, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, C.; Saruhan, I.; Akça, I. The insect pest problem affecting hazelnut kernel quality in Turkey. Acta Hortic. 2005, 686, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.O.; Tuncer, C. A new invasive polyphagous pest in Turkey, brown marmorated stink bug [Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)]: Identification, similar species and current status. Black Sea J. Eng. Sci. 2021, 4, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.O.; Tuncer, C.; Tortorici, F.; Özer, G. Egg parasitoids of green shield bug, Palomena prasina L. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in hazelnut orchards of Turkey. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, C.; De Gregorio, T.; Ozdemir, I.O.; Gurarslan Ceran, D.; Castello, G. Determination using field cages of damage types caused by green shield bug feeding on hazelnut kernels. Acta Hortic. 2023, 1379, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, C.; Saruhan, I.; Akça, I. Seasonal occurrence and species composition of true bugs in hazelnut orchards. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1052, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saruhan, İ.; Tunçer, M.K.; Tuncer, C. Economic damage levels of the green shield bug (Palomena prasina, Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Türkiye hazelnut orchards. Black Sea J. Agric. 2023, 6, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, L.; Moraglio, S.T.; Tavella, L. Halyomorpha halys, a serious threat for hazelnut in newly invaded areas. J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraglio, S.T.; Bosco, L.; Tavella, L. Halyomorpha halys invasion: A new issue for hazelnut crop in northwestern Italy and western Georgia? Acta Hortic. 2018, 1226, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, R.; Calvy, M.; Valentie, E.; Driss, L.; Guignet, J.; Thomas, M.; Tavella, L. Symptoms resulting from the feeding of true bugs on growing hazelnuts. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2022, 170, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymamí, A.; Barrios, G.; Sordé, J.; Palau, R.; Solano, C.; Domingo, L.; Salvat, A.; Rovira, M. Biology and population dynamics of Palomena prasina L. in hazelnut orchards in Catalonia (Spain). Acta Hortic. 2023, 1379, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamas, E.; Japoshvili, G. List of species of Pentatomids (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in the hazelnut orchards of Sakartvelo (Georgia) and their potential parasitoids. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2022, 20, 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Hoebeke, R.E.; Carter, M.E. Halyomorpha halys (Stål) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae): A polyphagous plant pest from Asia newly detected in North America. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 2003, 105, 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Faúndez, E.I.; Rider, D.A. The brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) in Chile. Arq. Entomolóxicos 2017, 17, 305–330. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Pal, C.; Anderson, D.; Vétek, G.; Farkas, P.; Burne, A.; Fan, Q.-H.; Zhang, J.; Gunawardana, D.N.; Balan, R.K.; et al. Genetic diversity analysis of brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys based on mitochondrial COI and COII haplotypes. BMC Genom. Data 2021, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wermelinger, B.; Wyniger, D.; Forster, B. First records of an invasive bug in Europe: Halyomorpha halys Stål (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae), a new pest on woody ornamentals and fruit trees? Bull. Société Entomol. Suisse 2008, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari, M.; Maistrello, L.; Piemontese, L.; Bonini, R.; Dioli, P.; Lee, W.; Park, C.-G.; Partsinevelos, G.K.; Rebecchi, L.; Guidetti, R. Genetic diversity of the brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys in the invaded territories of Europe and its patterns of diffusion in Italy. Biol. Invasions 2018, 20, 1073–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heyden, T.; Saci, A.; Dioli, P. First record of the brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) in Algeria and its presence in North Africa (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Rev. Gaditana Entomol. 2021, 12, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, A.L.; Hamilton, G.C. Life history of the invasive species Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in northeastern United States. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2009, 102, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskey, T.C.; Nielsen, A.L. Impact of the invasive brown marmorated stink bug in North America and Europe: History, biology, ecology, and management. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çerçi, B.; Koçak, Ö. Further contribution to the Heteroptera (Hemiptera) fauna of Turkey with a new synonymy. Acta Biol. Turc. 2017, 30, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Güncan, A.; Gümüş, E. Brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) (Hemiptera: Heteroptera, Pentatomidae), a new and important pest in Turkey. Entomol. News 2019, 128, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.O.; Doğan, F.; Tuncer, C. The preliminary study on the biology of an invasive species, Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Northwest Türkiye. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 11, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak, K.; Uluca, M.; Tuncer, C. Distribution and population density of Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Black Sea Region of Türkiye. Turk. J. Zool. 2023, 47, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.O.; Turan, I.; Alkan, M.; Tuncer, C.; Walton, V.; Özer, G. Invasive insect genetics: Start codon targeted (SCoT) markers provide superior data to describe genetic diversity of brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys, in a newly colonized region. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2025, 173, 1097–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedstrom, C.S.; Shearer, P.W.; Miller, J.C.; Walton, V.M. The effects of kernel feeding by Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) on commercial hazelnuts. J. Econ. Entomol. 2014, 107, 1858–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murvanidze, M.; Krawczyk, G.; Inasaridze, N.; Dekanoidze, L.; Samsonadze, N.; Macharashvili, M.; Khutsishvili, S.; Shengelaia, S. Preliminary data on the biology of the brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys in Georgia. Turk. J. Zool. 2018, 42, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.O.; Karakaya, O.; Ateş, U.; Öztürk, B.; Uluca, M.; Tuncer, C. Characterization of hazelnut kernel responses to brown marmorated stink bug [Halyomorpha halys Stål (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)] infestations: Changes in bioactive compounds and fatty acid composition. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 124, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saruhan, İ.; Tuncer, C. Research on damage rate and type of green shieldbug (Palomena prasina L., Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) on hazelnut. Anadolu J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 25, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ak, K.; Tuncer, C.; Baltacı, A.; Eser, U.; Saruhan, I. Incidence and severity of stink bugs damage on kernels in Turkish hazelnut orchards. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1226, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavella, L.; Arzone, A.; Miaja, M.; Sonnati, C. Influence of bug (Heteroptera, Coreidae and Pentatomidae) feeding activity on hazelnut in northwestern Italy. Acta Hortic. 2001, 556, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.O.; (Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA and Sakarya University of Applied Sciences, Sakarya, Türkiye); Walton, V.; (Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA). BMSB Damage Rate in Hazelnut Orchards in Oregon and Türkiye, 2025. (Unpublished work).

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization. Crop Production Statistics. 2025. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- TÜİK. Hazelnut Production Statistics. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2025. Available online: https://www.tuik.gov.tr/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Leskey, T.C.; Hamilton, G.C.; Nielsen, A.L.; Polk, D.F.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Bergh, J.C.; Herbert, D.A.; Kuhar, T.P.; Pfeiffer, D.; Dively, G.P.; et al. Pest status of the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys, in the USA. Outlooks Pest Manag. 2012, 23, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskey, T.C.; Lee, D.H.; Short, B.D.; Wright, S.E. Impact of insecticides on the invasive Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae): Analysis of insecticide lethality. J. Econ. Entomol. 2012, 105, 1726–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraglio, S.T.; Tortorici, F.; Pansa, M.G.; Castelli, G.; Pontini, M.; Scovero, S.; Visentin, S.; Tavella, L. A 3-year survey on parasitism of Halyomorpha halys by egg parasitoids in northern Italy. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAF. Plant Protection Products Database. Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Türkiye. 2025. Available online: https://bku.tarimorman.gov.tr (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Kuhar, T.P.; Kamminga, K. Review of the chemical control research on Halyomorpha halys in the USA. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.C.; Morrison, W.R.; Khrimian, A.; Rice, K.B.; Leskey, T.C.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Nielsen, A.L.; Blaauw, B.R. Chemical ecology of Halyomorpha halys: Discoveries and applications. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 989–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, V.M.; Dalton, D.T.; Miller, B.; Harris, E.T.; Mirandola, E.; Tait, G.; Krawczyk, G.; Mermer, S. Economic impact and management of brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stål) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), in Oregon hazelnut orchards. Acta Hortic. 2023, 1379, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colazza, S.; Peri, E.; Salerno, G.; Conti, E. Host searching by egg parasitoids: Exploitation of host chemical cues. In Egg Parasitoids in Agroecosystems with Emphasis on Trichogramma; Consoli, F.L., Parra, J.R.P., Zucchi, R.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 9, pp. 97–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, E.; Colazza, S. Chemical Ecology of Egg Parasitoids Associated with True Bugs. Psyche A J. Entomol. 2012, 2012, 651015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haye, T.; Fischer, S.; Zhang, J.; Gariepy, T. Can native egg parasitoids adopt the invasive brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae), in Europe? J. Pest Sci. 2015, 88, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckhoff, C.; Tatman, K.M.; Hoelmer, K.A. Natural biological control of Halyomorpha halys by native egg parasitoids: A multi-year survey in northern Delaware. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 1143–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costi, E.; Haye, T.; Maistrello, L. Surveying native egg parasitoids and predators of the invasive Halyomorpha halys in Northern Italy. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 143, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraglio, S.T.; Tortorici, F.; Giromini, D.; Pansa, M.G.; Visentin, S.; Tavella, L. Field collection of egg parasitoids of Pentatomidae and Scutelleridae in Northwest Italy and their efficacy against Halyomorpha halys under laboratory conditions. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2021, 169, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapponi, L.; Tortorici, F.; Anfora, G.; Bardella, S.; Bariselli, M.; Benvenuto, L.; Bernardinelli, I.; Butturini, A.; Caruso, S.; Colla, R.; et al. Assessing the distribution of exotic egg parasitoids of Halyomorpha halys in Europe with a large-scale monitoring program. Insects 2021, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, F.; Moraglio, S.T.; Pansa, M.G.; Scovero, S.; Visentin, S.; Tavella, L. Species composition of the egg parasitoids of bugs in hazelnut orchards in northwestern Italy. Acta Hortic. 2023, 1379, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, F.; Talamas, E.J.; Moraglio, S.T.; Pansa, M.G.; Asadi-Farfar, M.; Tavella, L.; Caleca, V. A morphological, biological and molecular approach reveals four cryptic species of Trissolcus Ashmead (Hymenoptera, Scelionidae), egg parasitoids of Pentatomidae (Hemiptera). J. Hymenopt. Res. 2019, 73, 153–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, M.A. Doğu Karadeniz Fındıklarında Zarar Yapan Palomena prasina L. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)’nın Biyoekolojisi Üzerinde Araştırmalar; Gıda-Tarım ve Hayvancılık Bakanlığı Zirai Mücadele ve Zirai Karantina Genel Müdürlüğü, Samsun Bölge Zirai Mücadele Araştırma Enstitüsü Yayınları: Samsun, Türkiye, 1975. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici, F.; Orrù, B.; Timokhov, A.V.; Bout, A.; Bon, M.-C.; Tavella, L.; Talamas, E.J. Telenomus Haliday (Hymenoptera, Scelionidae) parasitizing Pentatomidae (Hemiptera) in the Palearctic region. J. Hymenopt. Res. 2024, 97, 591–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.O. First record of Telenomus turesis (Walker), native egg parasitoid of invasive brown marmorated stink bug [Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)] in Turkey. Anadolu J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 38, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altanlar, E.; Kılıç, M.; Altaş, K.; Talamas, E.; Tuncer, C. First record of native egg parasitoid, Anastatus bifasciatus, on Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) eggs in Türkiye. J. Agric. Nat. 2023, 26, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, F.; Bombi, P.; Loru, L.; Mele, A.; Moraglio, S.T.; Scaccini, D.; Pozzebon, A.; Pantaleoni, R.A.; Tavella, L. Halyomorpha halys and its egg parasitoids Trissolcus japonicus and T. mitsukurii: The geographic dimension of the interaction. NeoBiota 2023, 85, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elton, C.S. The Ecology of Invasion by Plants and Animals; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, H.E.; Lawson Handley, L.J.; Schönrogge, K.; Poland, R.L.; Purse, B.V. Can the enemy release hypothesis explain the success of invasive alien predators and parasitoids? BioControl 2011, 56, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, H.V.; Hawkins, B.A. Accumulation of native parasitoid species on introduced herbivores: A comparison of hosts as natives and hosts as invaders. Am. Nat. 1993, 141, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchin, M.E.; Lafferty, K.D.; Dobson, A.P.; McKenzie, V.J.; Kuris, A.M. Introduced species and their missing parasites. Nature 2003, 421, 628–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchin, M.E.; Mitchell, C.E. Parasites, pathogens, and invasions by plants and animals. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, V.; Rondoni, G.; Brodeur, J.; Conti, E. An Egg Parasitoid Efficiently Exploits Cues from a Coevolved Host but Not Those from a Novel Host. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haye, T.; Zhang, J.; Risse, M.; Gariepy, T.D. A temporal trophic shift from primary parasitism to facultative hyperparasitism during interspecific competition between two coevolved scelionid egg parasitoids. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 18708–18718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abram, P.K.; Brodeur, J.; Burte, V.; Boivin, G. Parasitoid-induced host egg abortion: An underappreciated component of biological control services provided by egg parasitoids. Biol. Control 2016, 98, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abram, P.K.; Gariepy, T.D.; Boivin, G.; Brodeur, J. An invasive stink bug as an evolutionary trap for an indigenous egg parasitoid. Biol. Invasions 2014, 16, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.L.; Jennings, D.E.; Hooks, C.R.R.; Shrewsbury, P.M. Field surveys of egg mortality and indigenous egg parasitoids of the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys, in ornamental nurseries in the mid-Atlantic USA. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roversi, P.F.; Binazzi, F.; Marianelli, L.; Costi, E.; Maistrello, L.; Sabbatini Peverieri, G. Searching for native egg-parasitoids of the invasive alien species Halyomorpha halys Stål (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) in Southern Europe. Redia 2016, 99, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.L.; Jennings, D.E.; Hooks, C.R.R.; Shrewsbury, P.M. Sentinel eggs underestimate rates of parasitism of the exotic brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys. Biol. Control 2014, 78, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, M.L.; Dieckhoff, C.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Olsen, R.T.; Weber, D.C.; Herlihy, M.V.; Talamas, E.J.; Vinyard, B.T.; Greenstone, M.H. Biological control of sentinel egg masses of the exotic invasive stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål) in mid-Atlantic USA ornamental landscapes. Biol. Control 2016, 103, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abram, P.K.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Acebes-Doria, A.; Andrews, H.; Beers, E.H.; Bergh, J.C.; Bessin, R.; Biddinger, D.; Botch, P.; Buffington, M.L.; et al. Indigenous arthropod natural enemies of the invasive brown marmorated stink bug in North America and Europe. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Konopka, J.K.; Poinapen, D.; Gariepy, T.; McNeil, J.N. Understanding the mismatch between behaviour and development in a novel host-parasitoid association. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, M.L.; Buffington, M.L.; Talamas, E.J.; Gates, M.W. Impact of the egg parasitoid, Gryon pennsylvanicum (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae), on sentinel and wild egg masses of the squash bug (Hemiptera: Coreidae) in Maryland. Environ. Entomol. 2016, 45, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAF. Release of Trissolcus japonicus (Samurai wasp) for the Control of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug. Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Türkiye, Karadeniz Agricultural Research Institute. 2025. Available online: https://arastirma.tarimorman.gov.tr/ktae/Haber/207 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Javahery, M. Development of eggs in some true bugs (Hemiptera–Heteroptera). Part I. Pentatomoidea. Can. Entomol. 1994, 126, 401–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-Q.; Yao, Y.-X.; Qiu, L.-F.; Li, Z.-X. A new species of Trissolcus (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) parasitizing eggs of Halyomorpha halys (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) in China with comments on its biology. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2009, 102, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, F.; Vinson, S.B. Efficacy assessment in egg parasitoids (Hymenoptera): Proposal for a unified terminology. In Proceedings Trichogramma and Other Egg Parasitoids: 3rd International Symposium; Wajnberg, E., Vinson, S.B., Eds.; INRA: Paris, France, 1991; pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, M.A.; Kononova, S.V. Telenominae of the Fauna of the USSR; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Talamas, E.J.; Buffington, M.L.; Hoelmer, K. Revision of Palearctic Trissolcus Ashmead (Hymenoptera, Scelionidae). J. Hymenopt. Res. 2017, 56, 3–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askew, R.R.; Nieves-Aldrey, J.L. Further observations on Eupelminae (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea, Eupelmidae) in the Iberian Peninsula and Canary Islands, including descriptions of new species. Graellsia 2004, 60, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Gibson, G.A.; Tang, L.U.; Xiang, J. Review of the species of Anastatus (Hymenoptera: Eupelmidae) known from China, with description of two new species with brachypterous females. Zootaxa 2020, 4767, 351–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamas, E.J.; Bon, M.C.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Buffington, M.L. Molecular phylogeny of Trissolcus wasps (Hymenoptera, Scelionidae) associated with Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae). J. Hymenopt. Res. 2019, 73, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atak, S.; Uçkan, F.; Koçak, E.; Soydabaş, H.K. Egg parasitoids of Sunn Pest and their effectiveness in Kocaeli province. Kocaeli Üniversitesi Fen Bilim. Derg. 2018, 1, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhman, V.E.; Timokhov, A.V. Karyotypes of three species of the genus Trissolcus Ashmead, 1893 (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae). Russ. Entomol. J. 2019, 28, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mele, A.; Scaccini, D.; Pozzebon, A. Hyperparasitism of Acroclisoides sinicus (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) on two biological control agents of Halyomorpha halys. Insects 2021, 12, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, J.K.; Haye, T.; Gariepy, T.; Mason, P.; Gillespie, D.; McNeil, J.N. An exotic parasitoid provides an invasional lifeline for native parasitoids. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vet, L.E.; Dicke, M. Ecology of infochemical use by natural enemies in a tritrophic context. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1992, 37, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.; Costa, M.L.M.; Sujii, E.R.; Cavalcanti, M.D.G.; Redigolo, G.F.; Resck, I.S.; Vilela, E.F. Semiochemical and physical stimuli involved in host recognition by Telenomus podisi (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) toward Euschistus heros (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Physiol. Entomol. 1999, 24, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, M.L.; Herlihy, M.V.; Vinyard, B.T.; Weber, D.C.; Greenstone, M.H. Parasitism and predation on sentinel egg masses of three stink bug species (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in native and exotic ornamental landscapes. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlihy, M.V.; Talamas, E.J.; Weber, D.C. Attack and success of native and exotic parasitoids on eggs of Halyomorpha halys in three Maryland habitats. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapponi, L.; Bon, M.C.; Fouani, J.M.; Anfora, G.; Schmidt, S.; Falagiarda, M. Assemblage of the Egg Parasitoids of the Invasive Stink Bug Halyomorpha halys: Insights on Plant Host Associations. Insects 2020, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japoshvili, G.; Arabuli, T.; Salakaia, M.; Tskaruashvili, Z.; Kirkitadze, G.; Talamas, E. Surveys for Halyomorpha halys (Stål) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) and its biocontrol potential by parasitic wasps in the Republic of Georgia (Sakartvelo). Phytoparasitica 2022, 50, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konjević, A.; Tavella, L.; Tortorici, F. The first records of Trissolcus japonicus (Ashmead) and Trissolcus mitsukurii (Ashmead) (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae), alien egg parasitoids of Halyomorpha halys (Stål) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Serbia. Biology 2024, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimpel, G.E.; Mills, N.J. Biological Control: Ecology and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, S.; Jarrett, B.J.; Szűcs, M. Non-Target Attack of the Native Stink Bug, Podisus maculiventris, by Trissolcus japonicus, Comes with Fitness Costs and Trade-Offs. Biol. Control 2023, 177, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.; Fellowes, M. Learning and Natal Host Influence Host Preference, Handling Time and Sex Allocation Behaviour in a Pupal Parasitoid. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2002, 51, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.S.; Bilton, A.R.; Mak, L.; Sait, S.M. Host Switching in a Generalist Parasitoid: Contrasting Transient and Transgenerational Costs Associated with Novel and Original Host Species. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fors, L.; Markus, R.; Theopold, U.; Ericson, L.; Hambńck, P.A. Geographic Variation and Trade-Offs in Parasitoid Virulence. J. Anim. Ecol. 2016, 85, 1595–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, A.; Pavinato, V.A.C.; Parra, J.R.P. Fitness-Related Changes in Laboratory Populations of the Egg Parasitoid Trichogramma galloi and the Implications of Rearing on Factitious Hosts. BioControl 2017, 62, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.M.; Gilbert, L.; Johnson, D.; Karley, A.J. Limited Effects of the Maternal Rearing Environment on the Behaviour and Fitness of an Insect Herbivore and Its Natural Enemy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woltering, S.B.; Romeis, J.; Collatz, J. Influence of the Rearing Host on Biological Parameters of Trichopria drosophilae, a Potential Biological Control Agent of Drosophila suzukii. Insects 2019, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, B.J.; Linder, S.; Fanning, P.D.; Isaacs, R.; Szűcs, M. Experimental Adaptation of Native Parasitoids to the Invasive Insect Pest, Drosophila suzukii. Biol. Control 2022, 167, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Gariepy, T.; Mason, P.; Gillespie, D.; Talamas, E.; Haye, T. Seasonal parasitism and host specificity of Trissolcus japonicus in northern China. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haye, T.; Moraglio, S.T.; Stahl, J.; Visentin, S.; Gregorio, T.; Tavella, L. Fundamental host range of Trissolcus japonicus in Europe. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häner, N.; Fenijn, F.; Haye, T. Does intraspecific variation in Trissolcus japonicus affect its response to non-target hosts? BioControl 2024, 69, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, T.E.; Manning, L.A.M.; Avila, G.A.; Holwell, G.I.; Park, K.C. Electrophysiological Responses of Trissolcus japonicus, T. basalis, and T. oenone (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) to Volatile Compounds Associated with New Zealand Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 2024, 50, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haye, T.; Moraglio, S.T.; Tortorici, F.; Marazzi, C.; Gariepy, T.D.; Tavella, L. Does the Fundamental Host Range of Trissolcus japonicus Match Its Realized Host Range in Europe? J. Pest Sci. 2024, 97, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognon, R.; Aldrich, J.R.; Sant’Ana, J.; Zalom, F.G. Conditioning native Telenomus and Trissolcus (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) egg parasitoids to recognize the exotic brown marmorated stink bug (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae: Halyomorpha halys). Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costi, E.; Wong, W.H.; Cossentine, J.; Acheampong, S.; Maistrello, L.; Haye, T.; Talamas, E.J.; Abram, P.K. Variation in levels of acceptance, developmental success, and abortion of Halyomorpha halys eggs by native North American parasitoids. Biol. Control 2020, 151, 104396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, V.; Rondoni, G.; Peri, E.; Conti, E.; Brodeur, J. Learning can be detrimental for a parasitic wasp. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0238336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaepfer, M.A.; Sherman, P.W.; Blossey, B.; Runge, M.C. Introduced species as evolutionary traps. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, J.K.; Gariepy, T.D.; Haye, T.; Zhang, J.; Rubin, B.D.; McNeil, J.N. Exploitation of pentatomids by native egg parasitoids in the native and introduced ranges of Halyomorpha halys: A molecular approach using sentinel egg masses. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, E.; Foti, M.C.; Martorana, L.; Cusumano, A.; Colazza, S. The invasive stink bug Halyomorpha halys affects the reproductive success and the experience-mediated behavioural responses of the egg parasitoid Trissolcus basalis. BioControl 2021, 66, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Province | District (No. of Location) | Host | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Sakarya | Kocaali (4) | Corylus avellana | 40°56′50.3″ N | 30°51′13.3″ E |

| 40°56′48.3″ N | 30°51′22.0″ E | ||||

| 40°56′52.3″ N | 30°51′21.9″ E | ||||

| 40°57′8.5″ N | 30°51′16.9″ E | ||||

| Karasu (4) | 41°0′2.9″ N | 30°41′57.9″ E | |||

| 41°0′3.2″ N | 30°41′59.0″ E | ||||

| 41°0′5.2″ N | 30°41′58.7″ E | ||||

| 41°0′1.9″ N | 30°41′57.7″ E | ||||

| Geyve (1) | 40°31′44.2″ N | 30°28′20.8″ E | |||

| Düzce | Akçakoca (5) | 41°1′7.4″ N | 31°0′45.2″ E | ||

| 41°1′9.5″ N | 31°0′45.7″ E | ||||

| 41°1′10.2″ N | 31°0′42.4″ E | ||||

| 41°1′10.9″ N | 31°0′50.3″ E | ||||

| 41°1′9.6″ N | 31°0′50.9″ E | ||||

| 2023 | Sakarya | Kocaali (5) | C. avellana | 40°58′33.9″ N | 30°46′51.8″ E |

| Prunus spinosa | 40°58′38.8″ N | 30°46′51.2″ E | |||

| C. avellana | 40°56′50.3″ N | 30°51′13.3″ E | |||

| 40°56′48.3″ N | 30°51′22.0″ E | ||||

| 40°57′08.5″ N | 30°51′16.9″ E | ||||

| Karasu (4) | 41°00′03.0″ N | 30°41′57.9″ E | |||

| 40°59′59.4″ N | 30°41′53.3″ E | ||||

| 40°59′29.1″ N | 30°41′09.3″ E | ||||

| 40°59′29.6″ N | 30°40′44.0″ E | ||||

| Arifiye (2) | 40°41′56.8″ N | 30°20′49.6″ E | |||

| 40°42′03.1″ N | 30°20′44.0″ E | ||||

| Düzce | Akçakoca (2) | 41°01′07.4″ N | 31°00′45.2″ E | ||

| 41°01′09.5″ N | 31°00′45.7″ E | ||||

| Dereköy (5) | 40°48′41.8″ N | 30°55′22.6″ E | |||

| 40°48′38.1″ N | 30°55′40.9″ E | ||||

| C. avellana and P. avium | 40°48′38.0″ N | 30°55′39.9″ E | |||

| C. avellana | 40°48′41.8″ N | 30°55′42.4″ E | |||

| 40°48′29.4″ N | 30°55′39.6″ E | ||||

| Cumayeri (1) | 40°52′48.4″ N | 30°56′22.6″ E | |||

| 2024 | Sakarya | Arifiye (2) | C. avellana | 40°41′57.2″ N | 30°20′49.6″ E |

| Actinidia deliciosa | 40°42′17.9″ N | 30°25′01.1″ E |

| Year | Pest Species | Province | District (No. of Orchards) | Period | No. Egg Masses | No. Eggs | % Hatched | Eggs Parasitized % (No. of Parasitoids) | % Sucked | % Broken | % Unhatched | Species Composition of Parasitoids (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trissolcus belenus | Trissolcus cultratus | Telenomus turesis | Telenomus truncatus | Anastatus bifasciatus | ||||||||||||

| 2022 | P. prasina | Sakarya | Kocaali (5) | 13–20 May | 48 | 1301 | 54.42 | 18.60 ± 5.54 b (242) | 8.15 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 42.15 | 57.85 | - | - | - |

| Karasu (4) | 27 | 739 | 34.64 | 33.96 ± 8.60 a (251) | 2.3 | 0.27 | 24.49 | 21.91 | - | 67.33 | 10.76 | - | ||||

| Geyve (2) | 12 | 303 | 45.87 | 30.69 ± 14.21 ab (93) | 8.58 | 0 | 1.65 | 40.86 | 15.05 | - | 44.09 | - | ||||

| Düzce | Akçakoca (5) | 18 May–10 June | 71 | 1933 | 65.65 | 18.31 ± 4.24 c (354) | 6.57 | 1.76 | 3.88 | 55.93 | 21.19 | 22.88 | - | - | ||

| Total | 158 | 4276 | 55.47 | 21.98 ± 3.13 A (940) | 6.45 | 1.08 | 6.27 | 41.81 | 24.36 | 26.60 | 7.23 | - | ||||

| 2023 | P. prasina | Sakarya | Kocaali (8) | 3–26 May | 83 | 2112 | 82.58 | 9.61 ± 3.21 e (203) | 2.56 | 2.98 | 0.14 | 76.35 | 23.65 | - | - | - |

| Karasu (10) | 2–31 May | 99 | 2512 | 37.06 | 12.54 ± 3.07 d (315) | 0.04 | 2.67 | 0 | 32.38 | 8.25 | 57.14 | - | 2.22 | |||

| Arifiye (1) | 10–30 June | 5 | 96 | 33.33 | 60.42 ± 9.99 a (58) | 0 | 16.67 | 0 | 100 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Geyve (1) | 3 | 81 | 100 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Düzce | Akçakoca (5) | 8–29 May | 108 | 2931 | 71.95 | 21.08 ± 3.61 c (618) | 0 | 1.84 | 0 | 53.07 | 28.96 | 5.34 | 12.62 | - | ||

| Gümüşova (6) | 3 May–11 June | 95 | 2550 | 81.69 | 13.49 ± 3.35 d (344) | 0 | 1.14 | 0 | 14.53 | 42.15 | 43.31 | - | - | |||

| Cumayeri (1) | 15–30 May | 18 | 493 | 37.32 | 28.40 ± 10.29 b (140) | 0 | 6.09 | 0 | 19.29 | - | 57.86 | 22.86 | - | |||

| Total | 411 | 10,775 | 67.32 | 15.57 ± 1.63 B (1678) | 0.51 | 2.40 | 0.03 | 42.91 | 23.72 | 26.40 | 6.56 | 0.42 | ||||

| Totals for P. prasina in 2022 and 2023 | 569 | 15,051 | 63.96 | 17.39 ± 1.47 (2618) | 2.20 | 2.03 | 1.80 | 42.51 | 23.95 | 26.47 | 6.80 | 0.27 | ||||

| H. halys | Sakarya | Arifiye (1) | 20 June–30 July | 50 | 1293 | 95.82 | 3.25 ± 2.28 A (42) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38.1 | - | - | - | 61.9 | |

| 2024 | H. halys | Sakarya | Arifiye (16) | 25 June–16 July | 258 | 7197 | 96.3 | 1.75 ± 0.86 B (126) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22.22 | - | - | 22,22 | - |

| Totals for H. halys in 2023 and 2024 | 308 | 8490 | 96.23 | 1.98 ± 0.81 (168) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26.19 | - | - | 16.67 | 15.48 | ||||

| Parasitoid Species | Pest | Year | Province | Discovery Efficiency (%) | GLM (Discovery Efficiency, Wald χ2, p) | Exploitation Efficiency (%) | GLM (Exploitation Efficiency, Wald χ2, p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. belenus | H. halys | 2023 | Sakarya | 2.08 ± 0 | N/A * | 57.14 ± 0 | N/A |

| 2024 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 100 ± 0 | |||||

| P. prasina | 2022 | Düzce | 24.88 ± 15.53 a | Year χ2 = 0.55 (p = 0.459); Province χ2 = 0.35 (p = 0.553); Year × Province χ2 = 0.44 (p = 0.507) | 73.51 ± 8.11 b | Year χ2 = 3.97 (p = 0.046); Province χ2 = 1.20 (p = 0.273); Year × Province χ2 = 18.28 (p < 0.001) | |

| Sakarya | 16.46 ± 9.55 a | 77.34 ± 11.10 ab | |||||

| 2023 | Düzce | 3.75 ± 1.77 a | 89.83 ± 2.97 a | ||||

| Sakarya | 12.02 ± 6.12 a | 79.92 ± 5.70 b | |||||

| T. cultratus | P. prasina | 2022 | Düzce | 5.57 ± 2.19 a | Year χ2 = 0.004 (p = 0.948); Province χ2 = 0.86 (p = 0.354); Year × Province χ2 = 1.14 (p = 0.285) | 72.12 ± 15.04 b | Year χ2 = 34.19 (p < 0.001); Province χ2 = 5.49 (p = 0.019); Year × Province χ2 = 230.68 (p < 0.001) |

| Sakarya | 6.35 ± 2.90 a | 88.10 ± 9.95 a | |||||

| 2023 | Düzce | 4.51 ± 1.77 a | 84.46 ± 5.86 a | ||||

| Sakarya | 2.38 ± 1.66 a | 51.97 ± 20.25 c | |||||

| T. turesis | P. prasina | 2022 | Düzce | 8.25 ± 4.68 a | Year χ2 = 5.81 (p = 0.016); Province χ2 = 1.50 (p = 0.221); Year × Province χ2 = 2.51 (p = 0.113). | 28.18 ± 12.87 c | Year χ2 = 116.22 (p < 0.001); Province χ2 = 7.12 (p = 0.008); Year × Province χ2 = 4.88 (p = 0.027) |

| Sakarya | 9.62 ± 5.19 a | 17.83 ± 7.31 c | |||||

| 2023 | Düzce | 6.12 ± 3.04 a | 57.57 ± 16.24 b | ||||

| Sakarya | 4.39 ± 2.95 a | 79.97 ± 9.31 a | |||||

| T. truncatus | H. halys | 2024 | Sakarya | 0.14 ± 0.14 | N/A | 100 ± 0 | N/A |

| P. prasina | 2022 | Sakarya | 2.78 ± 1.90 a | 97.56 ± 2.44 a | |||

| 2023 | Düzce | 1.02 ± 0.69 a | 89.00 ± 11.00 b | ||||

| A. bifasciatus | H. halys | 2023 | Sakarya | 2.08 ± 0 | N/A | 100 ± 0 | N/A |

| P. prasina | 0.08 ± 0.08 | 87.50 ± 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ozdemir, I.O.; Şılbır, M.F.; Karadağ, E.; Alaybay, A.; Özer, G.; Tortorici, F.; Walton, V.M.; Dogan, F. Low Natural Parasitism of the Invasive Halyomorpha halys Versus Strong Native Suppression of Palomena prasina: Evidence from a Three-Year Survey in Northwestern Türkiye. Insects 2025, 16, 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121212

Ozdemir IO, Şılbır MF, Karadağ E, Alaybay A, Özer G, Tortorici F, Walton VM, Dogan F. Low Natural Parasitism of the Invasive Halyomorpha halys Versus Strong Native Suppression of Palomena prasina: Evidence from a Three-Year Survey in Northwestern Türkiye. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121212

Chicago/Turabian StyleOzdemir, I. Oguz, Muhammed Fatih Şılbır, Eren Karadağ, Abdullatif Alaybay, Göksel Özer, Francesco Tortorici, Vaughn M. Walton, and Furkan Dogan. 2025. "Low Natural Parasitism of the Invasive Halyomorpha halys Versus Strong Native Suppression of Palomena prasina: Evidence from a Three-Year Survey in Northwestern Türkiye" Insects 16, no. 12: 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121212

APA StyleOzdemir, I. O., Şılbır, M. F., Karadağ, E., Alaybay, A., Özer, G., Tortorici, F., Walton, V. M., & Dogan, F. (2025). Low Natural Parasitism of the Invasive Halyomorpha halys Versus Strong Native Suppression of Palomena prasina: Evidence from a Three-Year Survey in Northwestern Türkiye. Insects, 16(12), 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121212