Simple Summary

In the sub-Saharan regions of Africa, there are many termite species, of which very few have been correctly identified and described. The large majority of these species is either wrongly identified or waiting to be found and described because of the lack of identification keys and the errors within the existing keys. One way to overcome this problem is the use of reference works that contain illustrated parts of the body of termites along with accurate measurements of the features involved in termite identification. The purpose of this study is to provide pictures of the heads of soldiers (commonly used in termite identification) along with measurements of parts of the head and leg. A total of 12 termite species were examined. Seven of these species were already described, while the other five appear to have not been described before. Ten out of the twelve species are new records for the country.

Abstract

In Africa, despite their economic and ecological importance, termites are still relatively unknown. Their systematic remains uncertain, the approximate number of species for many biogeographic areas is underestimated, and there is still confusion in the identification of the species for many genera. This study combined morphological traits with morphometric measurements to determine several species collected in Togo and provided head illustrations of soldiers. Termites were sampled within the frame of transects laid in several landscapes inside three different parks including: Fosse aux Lions, Galangashie, and Fazao Malfakassa. Samples were grouped by morphospecies and measurements of part of the body (length and/or width of head, mandible, pronotum, gula, and hind tibia) were conducted. Twelve termite species including Foraminitermes corniferus, Lepidotermes sp., Noditermes cristifrons, Noditermes sp. 1 and Noditermes sp. 2, Promirotermes holmgren infera, Promirotermes sp., Unguitermes sp., Amitermes evuncifer, A. guineensis, A. truncatus, and A. spinifer were separated and pictured. Ten new species were added to the check list of the country, including five unidentified ones. Further studies such as biomolecular analysis should be carried out in order to clarify the status of these unknown species.

1. Introduction

Termites species and generic richness (particularly in the central and west part of the continent) is very important [1,2,3]. Most termite species are found in tropical forest, undisturbed savanna, and protected parks [4,5,6,7]. Although several studies have been conducted (and are still ongoing) on African termites, the diversity and the taxonomy of these termites remain poorly documented. Many species are waiting to be identified, while others have been incorrectly identified [8,9,10,11]. These taxonomical problems were pointed out by a group of researchers working on African termites [12].

In fact, the identification of African termites is based not only on the comparison of samples with reference species (which most of the time have not been correctly identified) but also with reference works by famous taxonomists [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. These reference works combine morphological traits (shape, color of different parts of the body) and morphometric measurements (length, width, and depth) of certain parts of the body of the soldier caste. The worker caste of termites is also used for identification, and the same features as soldiers are examined or measured [20]. In addition to the external morphological traits, gut anatomy is often used to identify termites [21]. All these descriptions are sometimes illustrated by hand drawing of the whole or part of the body of the termites instead of color images. This weakness is understandable as most of these reference works were carried out and published a century ago with tools and means that did not allow color images. However, since then, very few revisions have been conducted on African termite species. Among the useful reference works, several are also written in languages such as German [15], Italian [13,14] and French [8,9,17,18], which unlike English are not easily accessible to many researchers. Fortunately, recent research on termite taxonomy, in addition to using English, also uses images of the whole or part of the body of termites [22,23]. The research on termites in Togo (a West African country) has been hampered by the abovementioned issues. The check list of termite species of the country needs to be established. Although some recent studies have been carried out on the systematization of termite species, many areas of the country have still not been prospected, and their respective species remain unknown. The purpose of this study is to contribute to the knowledge of termites species in the country and to share color images along with the morphological features and morphometric measurements of several emblematic species from the central and northern parts of Togo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

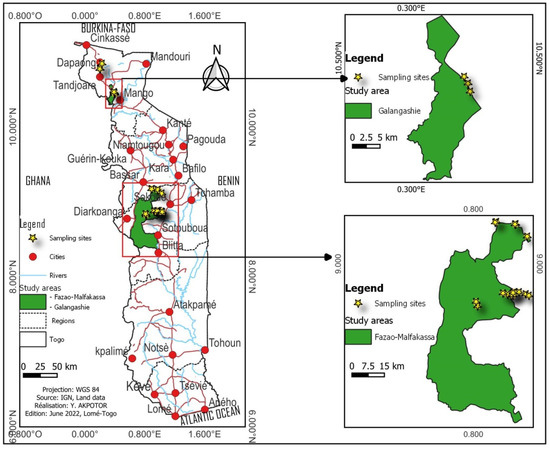

Termites were collected from three different parks (Figure 1) including: Fosse aux lions (10°46′–10°49′ N and 0° 11′–0°14′ E), Galangashie (10°19′–20°28′ N and 0°14′–0°27′ E), and Fazao-Malfakassa (8°20′–9°35′ N and 0°35′–1°02′ E).

Figure 1.

Map of Togo with prospected parks.

Fosse aux lions and Galangashi, both located in the northern part of Togo, are characterized by a Sudanian tropical climate with a long dry season (November to May) and a long rainy season (June to October). In these two parks, the mean temperatures range from 29 ± 2 °C during the rainy season to 30 ± 3 °C during the dry season. The annual rainfall is 986 mm, and the landscape is shrubby savanna. Fazao-Malfakassa, located in the center of the country, is characterized by a semi-humid tropical climate with a rainy season from April to October and a dry season from November to March. The mean temperatures range from 27.5 ± 1.5 °C during the dry season to 27 ± 2 °C during the rainy season. The annual rainfall is 120 mm, and the landscape is composed of dry forests, gallery forests, shrubby savanna, and fallows.

2.2. Termites Sampling

A total of 27 sampling sites were prospected with three transects per sampling site (81 transects for the whole study). The standard protocol [24] adapted to the savanna ecosystem [4,25] was used. Each transect of 100 × 5 m was divided into 20 sampling units of 5 × 2 m, which were sampled for 15 min [26,27]. Termites were searched within the frame of each sampling unit inside mounds, litter, wood, and grasses on trees by two well-trained collectors. After this searching on the surface, termites were also searched throughout eight soil scraps.

2.3. Termites Identification

Morphological traits (shape of the mandibles and the position of the mandible tooth) of the soldier and the number of antennal segments were used to separate species. Measurements of head width and length, left mandible length, pronotum width, and hind tibia length were made with a stereomicroscope (Leica EZ4) equipped with an integrated camera connected to a computer. Voucher specimens are conserved in the “Laboratoire d’Entomologie” of the University of Lomé (Lomé, Togo).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A total of 5 individual soldiers (when possible) were used for morphometric measurements. Thus, the morphometric data are presented as the mean of the measurements of each of chosen morphological feature from 5 individual soldiers.

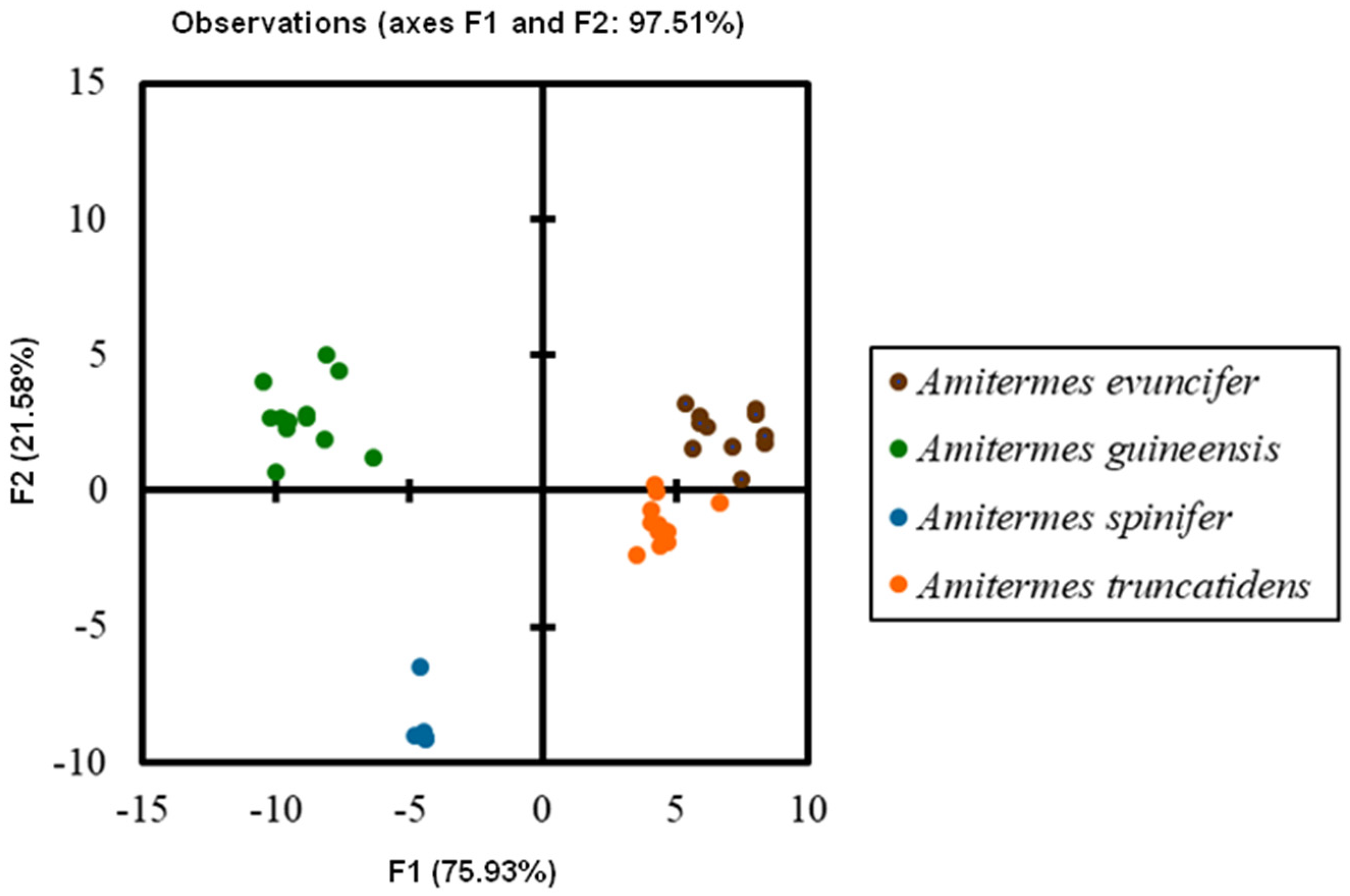

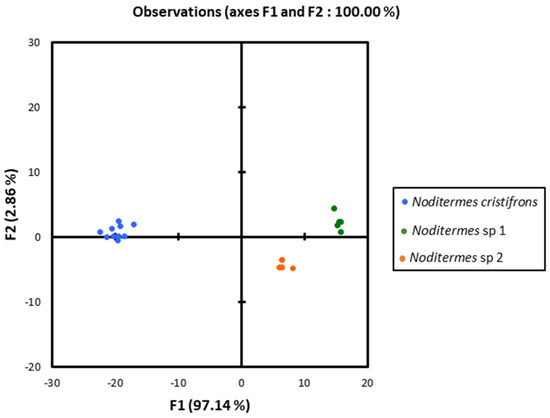

Factorial discriminant analysis (using morphometric data) was used to separate species with close measurements within the same genus. XLSTAT (version 6.1.9. 2003 Addinsoft, Inc., Broklyn, NY, USA) software was used for the factorial discriminant analysis.

3. Results

Twelve termite species belonging to seven genera and three subfamilies (Table 1) were examined in this study. All these species belonged to the Termitidae family. Except for A. evuncifer and A. guineensis, the other 10 species were recorded for the first time in Togo.

Table 1.

Termite species examined.

3.1. Foraminitermes Species

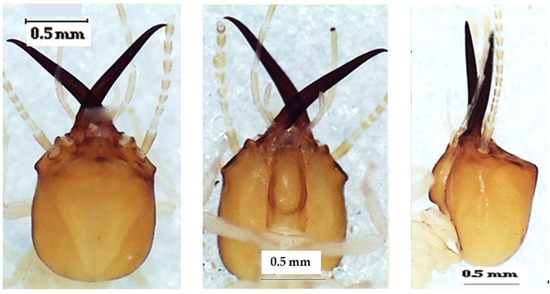

The head of the soldier was yellow-brown and sub-rectangular in the dorsal view (Figure 2). The labrum with a whitish tip was a bit shorter than the mandibles, which were shorter than the head capsule. The mandibles were brown at the base but darker at the top. The antennae had 15 articles. The morphometric measurements of this species are given in Table 2.

Figure 2.

The head of Foraminitermes corniferus soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Table 2.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Foraminitermes corniferus.

3.2. Lepidotermes Species

The head in the dorsal view (Figure 3) was almost square. The mandibles were wider at the base but tapered at the top. Each mandible had a basal tooth. There were 14 antennal articles. The morphometric measurements of this species are presented in Table 3.

Figure 3.

The head of Lepidotermes sp. soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Table 3.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Lepidotermes sp.

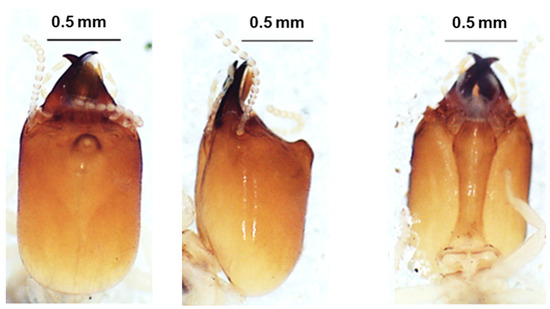

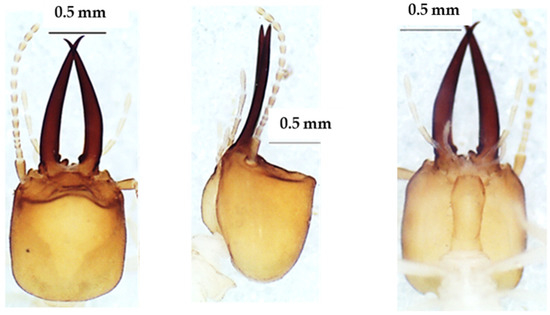

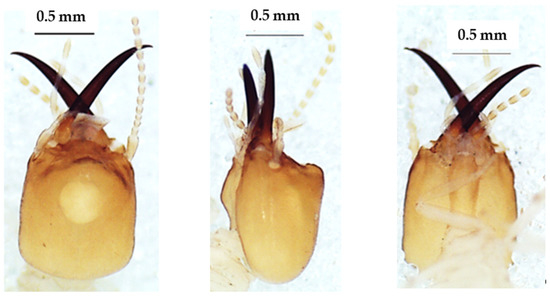

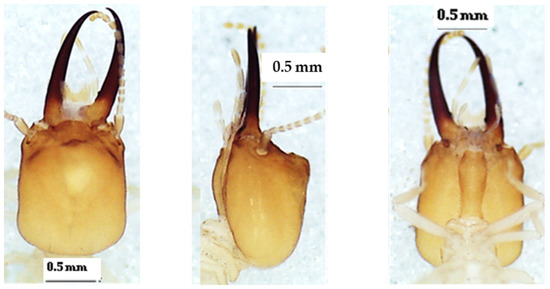

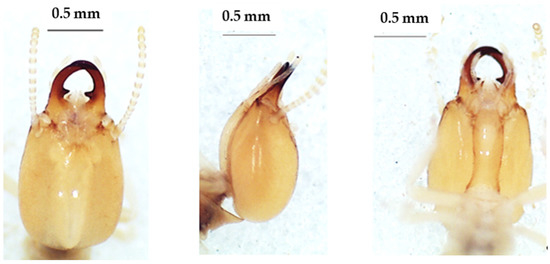

3.3. Noditermes Species

The heads of these three species in dorsal view (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) were almost rectangular and orange. Their respective labrum was bifurcate at the top. There were 14 antennal segments. However, they were distinct species, and their differences are highlighted in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. The head capsule of Noditermes sp. 1 was larger (1.626 ± 0.027 mm) and wider (1.15 ± 0.046 mm) than the other two Noditermes. Similarly, the mandibles of Noditermes sp. 1 were also longer (1.35 ± 0.026 mm) than those of the two other species. N. cristifrons had the smaller pronotum (0.508 ± 0.008 mm). The factorial differential analysis (Figure 7) shows clearly that these three Noditermes species were distinct.

Figure 4.

The head of Noditermes cristifrons soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Figure 5.

The head of Noditermes sp. 1 soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Figure 6.

The head of Noditermes sp. 2 soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Table 4.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Noditermes cristifrons.

Table 5.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Noditermes sp. 1.

Table 6.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Noditermes sp. 2.

Figure 7.

Noditermes species discrimination by factorial discriminant analysis.

3.4. Unguitermes Species

The head of the soldier in the dorsal view (Figure 8) was almost square and yellow-orange. The top of the labrum was rectilinear and wider than the base. The mandibles were longer than the head capsule (Table 7). There were 14 antennal articles.

Figure 8.

The head of Unguitermes sp. soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Table 7.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Unguitermes sp.

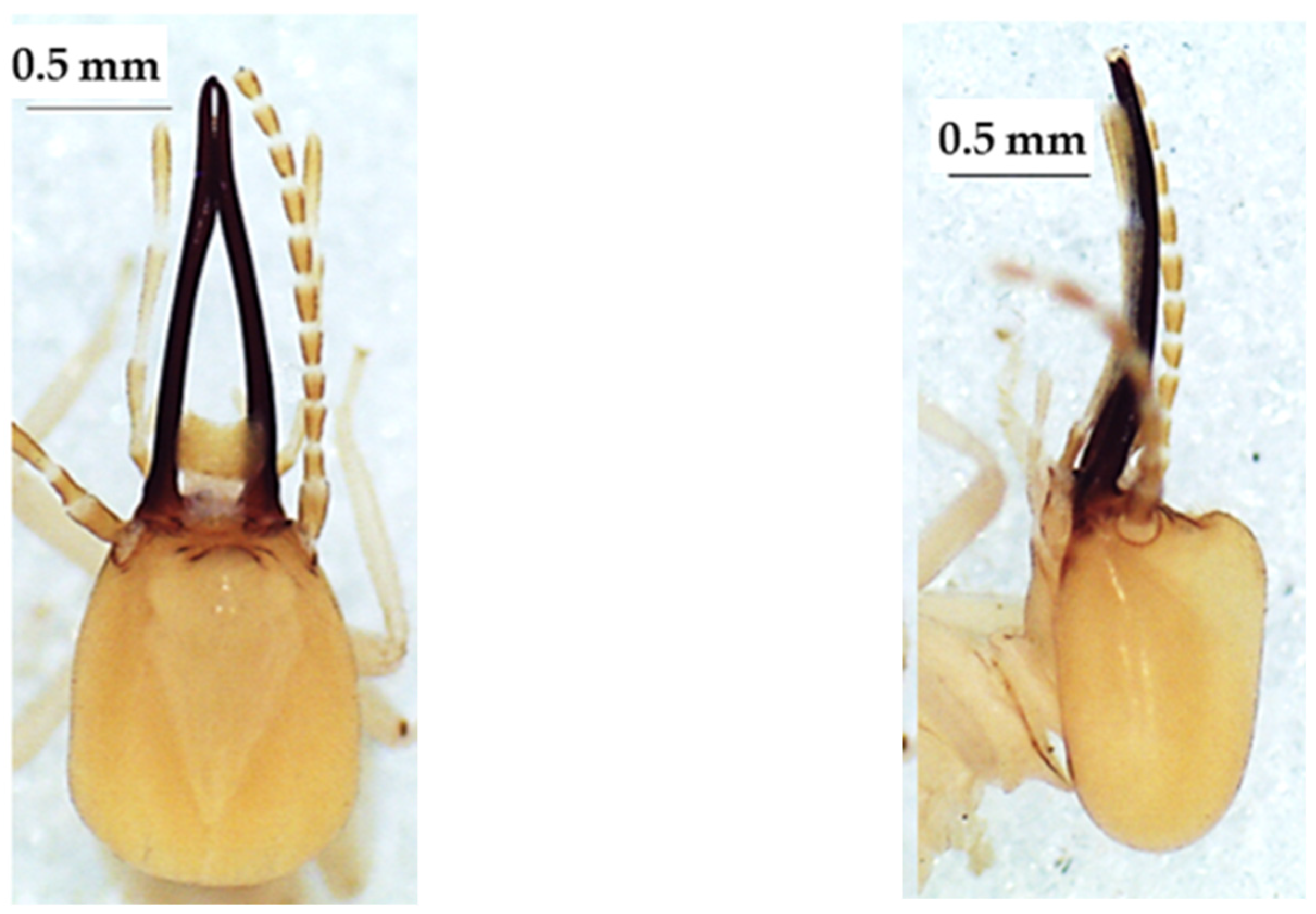

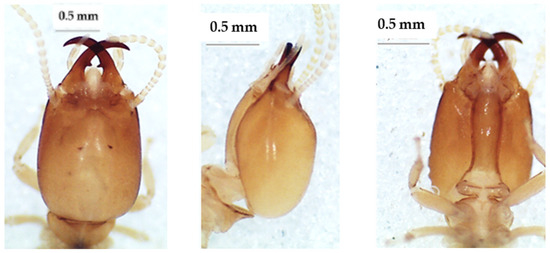

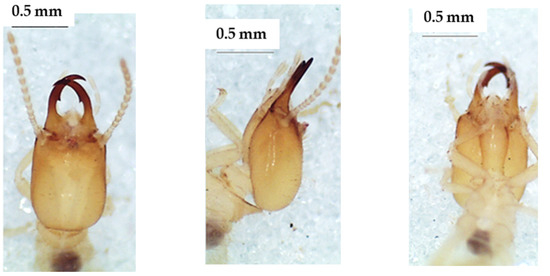

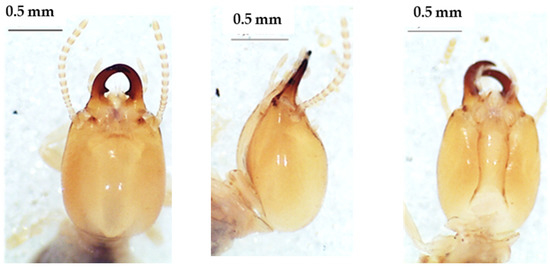

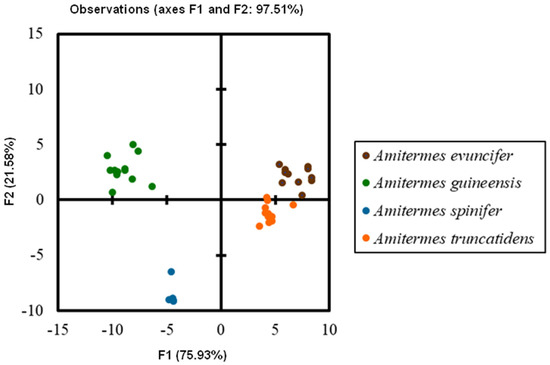

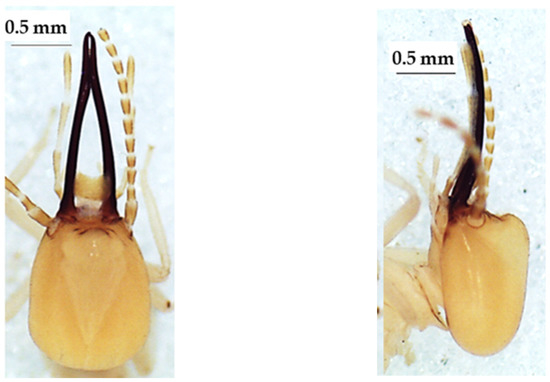

3.5. Amitermes Species

The four species of Amitermes including A. evuncifer (Table 8, Figure 9), A. guineensis (Table 9, Figure 10), A. spinifer (Table 10, Figure 11), and A. truncatidens (Table 11, Figure 12) were unambiguously identified. Apart from A. spinifer (with 13 antennal segments), the soldiers of the other three species had 14 antennal segments. All four species had mandibles strongly curved at the top, and each mandible had a tooth in its inner side. The tips of the mandibular teeth of A. evuncifer, A. truncatidens, and A. guineensis were horizontal, whereas in A. spinifer the tips of the mandibular teeth were pointing down. A. guineensis differed from the other species by the rectangular shape of the head capsule and especially by the average length, which was greater (1.225 ± 0.031 mm) than those of the other species. The species with a shorter head capsule was A. spinifer (0.933 ± 0.018 mm). The left mandible of A. guineensis was the longest (0.722 ± 0.058 mm), while A. truncatidens had the shortest left mandible (0.547 ± 0.023 mm). The ranges and measurements of head length, head width, left mandible length, pronotum width, gula width, and hind tibia length for each species are presented in Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11, respectively. Although the A. evuncifer and A. truncatidens measurements were close (Table 8 and Table 11), the factorial discrimant analysis showed that they were separate species (Figure 13), as well as the other two species (A. guineensis and A. spinifer).

Table 8.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Amitermes evuncifer.

Figure 9.

The head of Amitermes evuncifer soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Table 9.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Amitermes guineensis.

Figure 10.

The head of Amitermes guineensis soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Table 10.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Amitermes spinifer.

Figure 11.

The head of Amitermes spinifer soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Table 11.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Amitermes truncatidens.

Figure 12.

The head of Amitermes truncatidens soldier in dorsal view (left), lateral view (middle), and ventral view (right).

Figure 13.

Amitermes species discrimination by factorial discriminant analysis.

3.6. Promirotermes Species

For the two species of this genus, P. holmgreni infera, (Table 12, Figure 14) and Promirotermes sp. (Table 13, Figure 15) the hind part of the head was wider than the front part. The maxillary palps of the two species were as long as the mandibles, which were tapered at the top. Their respective labra were bifurcate and wider at the top.

Table 12.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Promirotermes holmgreni infera.

Figure 14.

The head of Promirotermes holmgreni infera soldier in dorsal view (left) and ventral view (right).

Table 13.

The measurements (mm) of the soldiers of Promirotermes sp.

Figure 15.

The head of Promirotermes sp. soldier in dorsal view (left) and ventral view (right).

4. Discussion

Among the recorded species, several had already been described, while others seemed to be ambiguous, because their measurements did not fall within the range of known species from West Africa. Foraminitermitinae include three genera: Foraminitermes, Labritermes, Holmgren 1914 and Pseudomicrotermes, Holmgren 1912 [28,29]. Foraminitermes species have been revised by Krishna [30]. Among the six described species of Foraminitermes, two species including F. tubifrons Holmgren 1912 and F. valens Silvestri 1914 [13], were both recorded in West Africa (Guinea, Ivory Coast, and Nigeria) and neighboring countries (Cameroon and Congo). F. corniferus is close to F. valens for some morphometric values in comparison to other species. However its head is larger than that of F. valens. As the other five Foraminitermes species, F. corniferus is endemic to the Ethiopian zoogeographical region and was recorded in Congo (Mukimbungu) [30]. The occurrence of F. corniferus in our study area indicates that the distribution area of this species, hitherto known from the Congo (Mukimnungu), extends to Togo. The genus Lepidotermes contains nine described species [29]. All these species are found principally in southern Africa [30,31,32,33,34]. Among these species, Lepidotermes sp. is morphologically close but smaller than the Lepidotermes lounsburyi and Lepidotermes planifacies described respectively by Silvestri [14] and Williams [35]. N. cristifrons, previously described as Cubitermes cristifrons [36], seemed to be the sole species of the seven described of the Noditermes genus [29] to occur in West Africa. It was recorded in Gambia in a forest ecosystem. The other two undetermined Noditermes (Noditermes sp. 1 and sp. 2) were all larger than N. cristifrons and appeared to not yet be described. This appears to be the same for Unguitermes sp. which was smaller than Unguitermes acutifrons [14] and Unguitermes magnus, Ruelle 1973 [37]. All the representative castes (imago, soldiers, and workers) of the four Amitermes species were already described and are all found in the Ethiopian zoogeographical region [19]. In this study, the ranges and means of the measurements of the soldiers fell within the ranges and means of respective species. Amitermes spinifer had the shorter and smaller head of all, while A. guineensis had the longer and the larger one. Compared to Promirotermes holmgren holmgren, P. holmgren infera, and P. holmgren redundans, the known species from West Africa, the Promirotermes sp. presented was clearly smaller and different by the shape of its head.

5. Conclusions

Twelve termite species were partially (head) illustrated in our study. Seven of these species including the four species of Amitermes genus (A. evuncifer, A. guineensis, A. spinifer, and A. truncatus), Foraminitermes corniferus, Noditermes cristifrons, and Promirotermes holmgren inferea were already described. The other five (Lepidotermes sp., Noditermes sp. 1, Noditermes sp. 2, Unguitermes sp., and Promirotermes sp.) were different by their measurements from the known species of the respective genus. This study was the first in Togo to present termite species with measurements and illustrations. It can be used as reference work for future taxonomic research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D.K., A.B.N. and A.I.G.; Methodology, T.Q.E., B.D.K., A.B.N. and A.I.G.; Software, B.D.K. and A.B.N.; Validation, T.Q.E., B.D.K., A.B.N. and A.I.G.; Formal analysis, T.Q.E., B.D.K. and A.B.N.; Investigation, T.Q.E. and B.D.K.; Data curation, T.Q.E., B.D.K. and A.B.N.; Writing—original draft preparation, B.D.K.; Writing—review and editing, T.Q.E., B.D.K., A.B.N. and A.I.G.; Visualization, T.Q.E., B.D.K., A.B.N. and A.I.G.; Supervision, B.D.K. and A.B.N.; Project administration, A.B.N. and A.I.G.; Funding acquisition, A.B.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was part of a project financed by UEMOA (Union Economique et Monétaire Ouest Africaine): PAES_UEMOA_Termites Afrique de l’Ouest_Don n° 2100155007376.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the authorities of the “Ministère de l’Environnement et des Ressources Forestières” for the logistics and other facilities. We thank Sanbena Banibea Bassan and villagers in the sampling localities for their help in the field.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Emerson, A.E. Geographical origins and dispersion of termite genera. Fieldiana. Zool. 1955, 37, 465–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleton, P.E.; Williams, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Explaining global termite diversity: Productivity or history? Biodivers. Conserv. 1994, 3, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleton, P. Global patterns of termite diversity. In Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbioses, Ecology; Abe, T., Bignell, D.E., Higashi, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosso, K.; Konaté, S.; Aïdara, D.; Linsenmair, K.E. Termite diversity and abundance across fire-induced habitat variability in a tropical moist savanna (Lamto, central Côte d’Ivoire). J. Trop. Ecol. 2010, 26, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosso, K.; Yéo, K.; Konaté, S.; Linsenmair, K.E. Importance of protected areas for biodiversity conservation in central Côte d’Ivoire: Comparison of termite assemblages between two neighbouring areas under differing levels of disturbance. J. Insect Sci. 2012, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosso, K.; Deligne, J.; Yéo, K.; Konaté, S.; Linsenmair, K.E. Changes in the termite assemblage across a sequence of land-use systems in the rural area around Lamto Reserve in Central Côte d’Ivoire. J. Insect Conserv. 2013, 17, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosso, K.; Roisin, Y.; Tiho, S.; Konaté, S.; Yéo, K. Short-term changes in the structure of termite assemblages associated with slash-and-burn agriculture in Côte d’Ivoire. Biotropica 2017, 49, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassé, P.P. Recherches sur la biologie des termites champignonnistes (Macrotermitinae). Ann. Sci. Nat. 1944, 6, 97–171. [Google Scholar]

- Bouillon, A.; Mathot, G. Quel est ce Termite Africain? Ed. de l’Université: Leopoldville, Belgian Congo, 1965; pp. 1–115. [Google Scholar]

- Josens, G. Etudes Biologique et Ecologique des Termites (Isoptera) de la Savane de Lamto-Pakobo (Côte d’Ivoire). Ph.D. Thesis, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Bruxelles, Belgique, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Ruelle, J.E. Isoptera. In Biogeography and Ecology of Southern Africa. Monographiae Biologicae; Werger, M.J.A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1978; pp. 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korb, J.; Kasseney, B.D.; Cakpo, Y.T.; Casalla Daza, R.H.; Gbenyedji, J.N.K.B.; Ilboudo, M.E.; Josens, G.; Koné, N.A.; Meusemann, K.; Ndiaye, A.B.; et al. Termite Taxonomy, challenges and prospects: West Africa, a case example. Insects 2019, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestri, F. Termitidi raccolti da L. Fea alla Guinea Portoghese e alla Isole, S. Thomé, Annobon, Principe e Fernando Poo. Ann. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. 1912, 45, 211–255. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri, F. Contribuzione alla conoscenza dei Termitidi e Termitophili dell’Africa occidentale. I. Termitidi. Bolletino Lab. Zool. Gen. Agrar. R Sc. Super. d’Agric. 1914, 9, 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, A.E. Termites of the Belgian Congo and the Cameroon. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1928, 57, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Grassé, P.P. Recherches sur la systématique et la biologie des termites de l’Afrique occidentale française. Première partie: Protermitidae, Mesotermitidae et Metatermitidae (Termitinae). Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 1937, 106, 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Noël, J. Le parc national du Niokolo-Koba. VIII. Isoptera. Mém. l’IFAN 1969, 84, 113–178. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöstedt, Y. Revision der Termiten Afrikas. 3. Monographie. In Kungl Svenska Vetenska Akademiens Handlingar; Almqvist & Wiksells Boktryckeri—A.-B.: Stockholm, Sweden, 1925; pp. 1–435. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, W.A. The termite genus Amitermes in Africa and the Middle East. Nat. Resour. Inst. Bull. 1992, 51, 1–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, W.A. The Identification of Worker Castes of Termite Genera from Soils of Africa and the Middle East; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1998; p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans, S.; Deligne, J.; Roisin, Y.; Josens, G. Phylogeny and revision of the “Cubitermes complex” termites (Termitidae: Cubitermitinae). Syst. Entomol. 2021, 46, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, A.B.; Njie, E.; Correa, P.A. Termites (Blattodea Latreille 1810, Termitoidae Latreille 1802) of Abuko Nature Reserve, Nyambai Forest Park and Tanji Bird Reserve (The Gambia). Insects 2019, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, A.B.; Ilboudo, M.E.; Sankara, F.; Bozdoğan, H. Diversity of Termites (Termitoidae Latreille) of the West Burkina Faso. Curr. Trends Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2021, 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.T.; Eggleton, P. Sampling termite assemblages in tropical forests: Testing a rapid biodiversity assessment protocol. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000, 37, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausberger, B.; Kimpel, D.; van Neer, A.; Korb, J. Uncovering cryptic species diversity of a community in a West African Savanna. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2011, 61, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyra, J.; Korb, J. Termite Communities along a Disturbance Gradient in a West African Savanna. Insects 2019, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effowe, T.Q.; Kasseney, B.D.; Ndiaye, A.B.; Sanbena, B.B.; Amevoin, K.; Glitho, I.A. Termites’ diversity in a protected park of the northern Sudanian savanna of Togo (West Africa). Nat. Conserv. 2021, 43, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.S.; Krishna, K. Family-Group Names for Termites (Isoptera); American Museum of Natural History: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, R. Termite Database. Available online: http://termitologia.net (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Krishna, K. The African Genus Foraminitermes Holmgren (Isoptera, Termitidae, Termitinae); American Museum of Natural History: New York, NY, USA, 1963; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrar, P. Termites of a South African Savanna. I. List of Species and Sub-habitat Preferences. Oecologia 1982, 52, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darlington, J.P.E.C. Termites (Isoptera) as secondary occupants in mounds of Macrotermes michaelseni (Sjöstedt) in Kenya. Insectes Soc. 2011, 59, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muvengwi, J.; Mbiba, M.; Ndagurwa, H.G.T.; Nyamadzawo, G.; Nhokovedzo, P. Termite diversity along a land use intensification gradient in a semi-arid savanna. J. Insect Conserv. 2017, 21, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netshifhefhe, S.R.; Kunjeku, E.C.; Visser, D.; Madzivhe, F.M.; Duncan, F.D. An Evaluation of Three Field Sampling Methods to Determine Termite Diversity in Cattle Grazing Lands. Afr. Entomol. 2018, 26, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.M.C. New East African Termitinae (Isoptera: Termitidae). Proc. R. Entomol. Soc. 1954, 23, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasmann, E. Zur Kenntnis der Termiten und Termitengäste von Belgischen Kongo. Rev. Zool. Afr. 1911, 1, 91–117. [Google Scholar]

- Ruelle, J.E. Four new species of Ungitermes sjöstedt from Ethiopian region (Isoptera, Termitidae). C. Ser. A 1973, 2, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).