Simple Summary

The Aphis gossypii is a global problem for its pesticide resistance with substantial economic and ecological cost and a wide host range, including cotton and cucurbits. The development of insecticide resistance is rapid and widespread and threatens crop productivity. Biopesticides have emerged as a better alternative for pest control. Cucurbitacin B (CucB) and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) are the major secondary metabolites of host plants cucurbits and cotton. In this study, we used cotton- and cucurbit-specialized aphids (CO and CU) as a study system to better understand the effects of CucB and EGCG on cotton aphid. Our study showed that CucB and EGCG can significantly reduce the population-level fitness of A. gossypii, affect their ability to adapt to nonhost plants and alter the levels of some detoxifying enzymes, which showed a potential to be developed into new biopesticides against the notorious aphids.

Abstract

Aphis gossypii (Glover) is distributed worldwide and causes substantial economic and ecological problems owing to its rapid reproduction and high pesticide resistance. Plant-derived cucurbitacin B (CucB) and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) are known to have insecticidal and repellent activities. However, their insecticidal activity on cotton- and cucurbit-specialized aphids (CO and CU), the two important host biotypes of A. gossypii, remains to be investigated. In the present study, we characterized, for the first time, the effects of these two plant extracts on the two host biotypes of A. gossypii. CucB and EGCG significantly reduced the A. gossypii population-level fitness and affected their ability to adapt to nonhost plants. Activities of important detoxification enzymes were also altered, indicating that pesticide resistance is weakened in the tested aphids. Our results suggest that CucB and EGCG have unique properties and may be developed as potential biopesticides for aphid control in agriculture.

1. Introduction

Agricultural losses due to pests pose considerable economic and ecological challenges, exacerbated by climate change [1]. So far, insect pest control has mostly depended on the use of synthetic chemical insecticides [2,3]. However, extensive and long-term application of synthetic insecticides has resulted in residual pollution in food, water, and other environmental components with adverse effects on human health and ecosystems [4], along with a strong negative impact on biodiversity [5]. Meanwhile, insects have evolved multiple mechanisms to overcome insecticide toxicity, including detoxification and excretion, which reduce pesticide effectiveness [6,7]. The development of insecticide resistance is rapid and widespread and threatens crop productivity. In contrast, biopesticides (e.g., fungus and plant extracts) have therefore emerged as a better alternative for pest control [8,9,10]. They can potentially reduce the use of chemical pesticides and provide new ideas for the synthesis of novel biopesticides for pest control [8,9,11]. Some plant extracts are being used for the management of insect pests such as Plutella xylostella, and Drosophila suzukii, and their application is becoming an integral part of ecological conservation programs [12,13].

Cucurbitacin B (CucB) and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) are the major secondary metabolites of host plants cucurbits and cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), respectively [14,15]. They can be easily extracted from plants or synthesized in vitro [16,17]. Cucurbitacin is a group of natural triterpenoids, oxygen-rich compounds commonly found in Cucurbitaceae family, and are toxic to some arthropods [18,19,20]. A previous study showed that high concentrations of CucB as part of an artificial diet increases aphid mortality and decreases the fitness of melon aphids [21]. EGCG is a type of catechins and is a major component of the polyphenols found in cotton tissues [14,22,23]. EGCG strongly and directly inhibits telomerase [24] and affects metabolism in mammals and insects [25,26]. Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s), glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), carboxylesterase (CarE), acetylcholinesterase (AchE), and acid phosphatase (ACP) are involved in xenobiotic metabolism of insects [27,28,29,30,31]. However, the effects of CucB and EGCG on population-level fitness and xenobiotic metabolism enzymes of cotton-melon aphids have never been adequately characterized.

The cotton-melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae), is a notorious pest of economically important crops, including cotton and cucurbits [2,10]. It has a worldwide distribution and causes substantial crop loss owing to its rapid clonal reproduction and a broad host range [7,32,33]. It also acts as a vector for transmitting viral diseases [33,34]. Aphids live by sucking nutrients from the plant phloem, which results in nutrient loss, hinders photosynthetic capacity of plant, distorts plant growth and development, and induces rapid plant defense responses including remarkable changes in plant secondary metabolites [35]. Previous studies illustrate that A. gossypii populations have formed obvious host races, which use only a subset of host plant species in their recorded host range [36,37]. Cotton and cucurbit-specialized aphids (CO and CU, respectively), are two typical biotypes that have strong host-specific natures [38]. Interestingly, the two host-specialized aphids cannot survive and establish populations after reciprocal host transfers [36]. In the last few decades, A. gossypii has developed resistance to all major groups of synthetic insecticides and has affected cotton yields in virtually all cotton-growing areas worldwide [39]. Apparently, A. gossypii has evolved to adapt to sudden environmental changes, in particular, it has experienced several geographic migrations and host transfers, which is generally accompanied by multiple biotic and abiotic stresses viz. environmental stress, host nutrition stress, and population density stress. [40]. Due to the lack of active selection, cotton aphid often landed on a non-optimal host, resulting in development of strong host adaptation towards an unexpected host. Overcoming host’s secondary defense substances is critical for adaptation to an unexpected host [3,37]. Therefore, an effective control method for A. gossypii and understanding the mechanisms of adaptation towards an unexpected host are both essential for a potentially suitable control program. Development of biopesticides against A. gossypii is critical and will require a better understanding of the effects of plant secondary metabolites on aphid population dynamics.

We hypothesize that both CucB and EGCG are detrimental to the ecological fitness of cotton-melon aphid. In this study, we assess the potential effects of CucB and EGCG on population-level fitness, nonhost adaption of offspring (offspring of CU fed on cotton, and CO fed on cucumber), and activities of key detoxification enzymes of A. gossypii in the laboratory. The findings from the present study are essential for understanding how plant–aphid interactions are affected by these important allelochemicals and further the application of CucB or EGCG for integrated aphid management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Maintenance

Aphid colonies were collected from cotton and cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) plants in the field of Anyang Experimental Station, Institute of Cotton Research, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (ICR, CAAS), Henan Province (36°5′34.8″ N, 114°31′47.19″ E). The colonies of cotton-specialized aphids (CO) and cucurbit-specialized aphids (CU) were maintained on cotton and cucumber plants, respectively, for more than 100 generations (2 years) without exposure to any insecticides in the laboratory. The biotypes were identified using a previously published protocol [41]. Aphids were reared in insect rearing cages (35 cm × 35 cm × 35 cm, Baoyuan Xingye Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China; the cage frames were made from stainless steel tube covered with nylon yarn around it) in controlled climate chambers maintained at 26 ± 1 °C with 65 ± 5% relative humidity (RH) and a photoperiod of 16:8 h (light: dark).

2.2. Preparation of CucB and EGCG

CucB (CAS:6199-67-3) and EGCG (CAS:989-51-5) (purity > 95% in both) were purchased from Huayueyang Biotech. Co. (Beijing, China). Acetone (CAS:67-64-1) purchased from Beijing Chemical Works (Beijing, China) was used as a solvent for CucB while EGCG was dissolved in water. Solutions of 1, 5, and 10 mg/L CucB and EGCG were prepared separately for toxicity tests according to previous studies [42,43] and our preliminary experiment. While distilled water and 50% acetone was used as a negative control, respectively.

2.3. Toxicity Analysis of CucB and EGCG on A. gossypii

The toxicities of CucB and EGCG on A. gossypii were evaluated under laboratory conditions where the aphids were fed on natural diets containing CucB and EGCG using a modified leaf-dipping method [44,45]. Briefly, individual cucumber or cotton leaves (The leaf measures 8–9 cm in diameter) were dipped in test solutions for 30 s. Treated leaves were then dried in the fume hood for 60 min. Afterward, the leaves were placed with the abaxial surface facing upward on the surface of 1.8% agar in petri dishes (9 cm D × 1.5 cm H). Aphids were then transferred to the petri dish (one in each), and the leaves were replaced every 1–2 days. Aphids were considered dead when they did not react for at least 5 min, and the body turned black after being touched with a soft brush.

2.3.1. Effects of CucB and EGCG on the Life History Traits of A. gossypii

Five-day-old adult CO and CU (generation F) were separately transferred to the petri dishes containing host leaves treated with CucB and EGCG, and the progeny produced in 24 h was taken as F0 generation. After 24 h, all adult aphids (F) were removed leaving behind only the newborn nymphs (F0) (n = 100, 10 aphids for one time, and repeat for 10 times). The aphid (F0) survival rate and fecundity under each treatment were recorded daily (i.e., the number of newborn nymphs F1 laid by each aphid F0 and the survival status of aphids F0 were observed and recorded daily until the eventual death of the aphids F0) to estimate the direct effects of CucB and EGCG on the population-level fitness longevity and fecundity of aphid populations. All newborn nymphs (F1) were removed from the petri dishes immediately after birth.

2.3.2. Effects of CucB and EGCG on the Nonhost Adaptation of F1 Generations

The CO and CU neonate aphids (F1) described in Section 2.3.1 were transferred to untreated nonhost plants in the petri dish (n = 100). In other words, the F0 was fed on toxin treated host plant for whole lifecycle, while the F1 was transferred to a clean nonhost plant. Then, the survival rate of F1 was recorded daily [46]. Their fecundity was checked every day until the death of all individuals to estimate the indirect effects of CucB and EGCG on the aphid population-level fitness in nonhost plant adaptation.

2.3.3. Effects of CucB and EGCG on Detoxifying Enzymes of A. Gossypii

Following starvation for 5 h, 3rd instar nymph aphids (colonies were fed on clean host leaves) were transferred to the petri dishes containing the leaves treated with CucB and EGCG (0, 1, 5, 10 mg/L, and control) as previously described. The samples were collected to identify the content of detoxifying metabolic enzymes with different interval of exposure viz. t1; after 24 h, t2; after 48 h, and t3; after 72 h. Subsequently, aphids were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until use. For each treatment/exposure time, 60 aphids were raised separately for each treatment and collected in three replicates after the specified exposure time.

The enzymes were tested using the following kits according to the instructions: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) assay kit (Cat. No. A024-1-1), Carboxylesterase (CarE) test kit (Cat. No. A133-1-1), Glutathione S-transferase (Cat. No. GST) assay kit (Cat. No. A004), Acid phosphatase (ACP) assay kit (Cat. No. A060-1) and Insect cytochrome P450 Elisa Kit (Cat. No. H303) (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Life table data were analyzed according to the life-table, two-sex life table theory [47]. TWO-SEX-MSChart analysis was carried out for analysing the life table. The population age-specific survival rate (lx), the net reproductive rate (R0, offspring/individual), intrinsic rate of increase (r, day−1), the finite rate of increase (λ, day−1), and mean generation time (T, day) were calculated [47]. To obtain stable estimates of variances and standard errors of the developmental time, longevity, fecundity, and other population parameters, we used the bootstrap technique to calculate the means, to estimate the variances and standard error [48,49] with 100,000 resampling (100,000 bootstraps generated a normal frequency distribution and less variable results, which were not caused by the variation of sample sizes) [50]. The paired test was used to assess differences among treatments [51].

Differences in enzyme content were analyzed via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test and two-way ANOVA using SAS 9.4.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of CucB and EGCG on the Life History Traits of A. gossypii

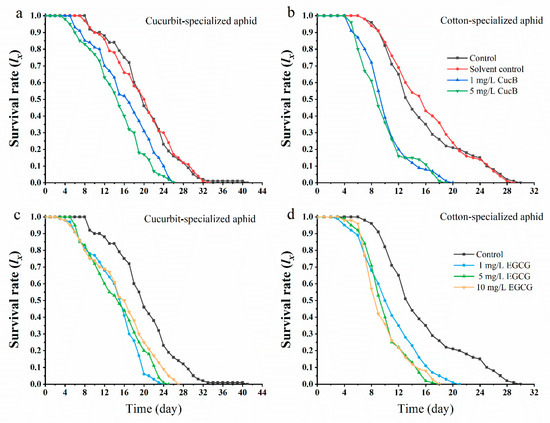

The negative effects of CucB and EGCG on insects have been reported in Bactrocera cucurbitae [52], Diabrotica virgifera [53], Heterodera glycines [54], and Drosophila melanogaster [55]. The insecticidal and repellent activities of CucB and EGCG have been studied, and an artificial diet was used to measure the effect of CucB on aphid demographics [56]. In this study, we pretreated cotton and cucumber leaves (leaf-dipping method) for aphid feeding with different concentrations of CucB and EGCG, and investigated the survival rates of the F0 generation of CO and CU. We found that exposure of A. gossypii to CucB and EGCG significantly decreased the survival rates of both biotypes (Figure 1). From day 5 of feeding, the survival rates declined rapidly in both CU and CO treated with CucB or EGCG, but declined slightly at day 8 of feeding in the water- or solvent-treatment controls. The F0 aphids maintained on CucB or EGCG treated leaves all died after 20–24 days of feeding, but the survival rate for CO and CU control groups were 21% and 14%, respectively. Thus, the results indicate significant toxicity for CucB and EGCG on aphids when provided as part of their natural diet. Moreover, the responses were stronger with higher concentrations of CucB and EGCG (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival rate (lx) of Aphis gossypii exposed to Cucurbitacin B (CucB) and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG). (a): CUS exposed to CucB; (b): COS exposed to CucB; (c): CUS exposed to EGCG; (d): COS exposed to EGCG.

We compared the life tables of aphids treated with different concentrations of CucB and EGCG with those in control groups (Table 1 and Table 2). The parameters for population dynamics, including r, R0, λ, T, and oviposition day were significantly reduced when compared with the control groups except for the T of CO fed on EGCG treated cotton leaves (Table 2). While EGCG increased the total pre-ovipositional period (TPRP, day) (>4.2 d in CU and >5.0 d in CO), 5 mg/L CucB significantly suppressed the fecundity (22.6) and longevity (9.9 d) in CU. Furthermore, after exposing individuals to CucB and EGCG, the growth period of pre-adult and the APRP (pre-reproductive period) significantly increased. EGCG inhibited the development of F0 CO with more potent effects at higher concentrations (Table 1 and Table 2). However, there was no evident dose-dependent effect of EGCG on CU (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Effect of CucB and EGCG on fecundity, longevity, adult pre-reproductive period (APRP), total pre-reproductive period (TPRP), and mean and oviposition day of Aphis gossypii.

Table 2.

Effects of CucB and EGCG on population parameters of Aphis gossypii.

3.2. Effects of CucB and EGCG on the Nonhost Adaptation of F1 Generations

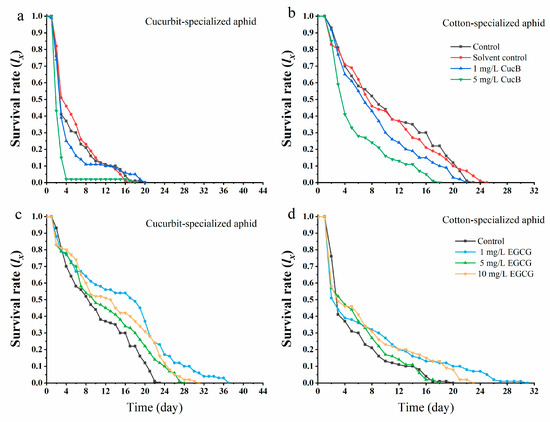

Exposure to CucB significantly decreased the survival rate of A. gossypii offspring that fed on nonhost plants (Figure 2a,b). On cotton leaves, the survival rate of CU offspring from parents exposed to CucB was considerably decreased when compared with the control. Four days after they were transferred to nonhost plants, only 2% of CU survived while 50% survived in the control group. The results were similar for CO aphid offspring. Moreover, the effect of CucB on F1 was more substantial at higher concentrations. The mortality in CO aphid offspring born of the EGCG exposed parents was also increased. The survivorship curve indicated that the increased mortality occurred at early life stages (<5 d) (Figure 2d). On the contrary, EGCG improved the performance of the F1 of CU on non-host plants where the mortality rate of A. gossypii was reduced when compared to the control group (Figure 2c). Meanwhile, the mortality rate of A. gossypii did not increase with the concentration of EGCG. A low concentration of EGCG (1 mg/L) showed a non-host plant adaptation of cotton-melon aphid (Figure 2c,d).

Figure 2.

Survival rate (lx) of Aphis gossypii on nonhost plants when the maternal generation is exposed to CucB and EGCG. (a): CUS exposed to CucB; (b): COS exposed to CucB; (c): CUS exposed to EGCG; (d): COS exposed to EGCG.

We also investigated the life table parameters of the above aphid offspring in nonhost plants (Table 3 and Table 4). Compared with the untreated control group, the pre-adult duration, oviposition day, and fecundity of the F1 generation significantly increased, due to the treatment of the parental generation with CucB and EGCG, except F1 of CU on cotton after exposed to CucB (Table 3). Furthermore, after exposing the F0 individuals to CucB, the TPOP, longevity of the F1 generation of CO significantly decreased (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of CucB and EGCG on fecundity, longevity, adult pre-reproductive period (APRP), total pre-reproductive period (TPRP), and mean and oviposition day of Aphis gossypii on nonhost plant.

Table 4.

Effects of CucB and EGCG on F1 population parameters of Aphis gossypii on nonhost plant.

Parameters for CU with maternal generation exposed to CucB (R0 less than 1, r < 0, and λ < 1) suggested a sub sequential population extinction. This effect was further enhanced when a higher concentration of CucB was used. However, compared with the control group, parental exposure to EGCG improved the fitness of CU, and this improvement was dose-dependent (r > 0). The values of life table parameters (r, λ) of CO did not differ significantly between CucB and EGCG treatments. Nevertheless, CucB reduced the fecundity, R0, longevity, and T with stronger effects at higher concentrations (Table 4). Similarly, maternal generation exposure to EGCG increased fecundity, longevity, and T (Table 3 and Table 4). However, 1 mg/L EGCG had stronger effects on increasing longevity, fecundity, and population parameters (R0, λ, r) in both CU and CO.

Nevertheless, when compared with the host-fed A. gossypii, feeding on nonhost plants significantly reduced the population-level fitness of CU and CO (Table 1 and Table 2, control). However, EGCG could improve population-level fitness of cotton-melon aphids on non-host plants to some extent (Table 3 and Table 4).

3.3. Effects of CucB and EGCG on Detoxifying Enzymes of A. Gossypii

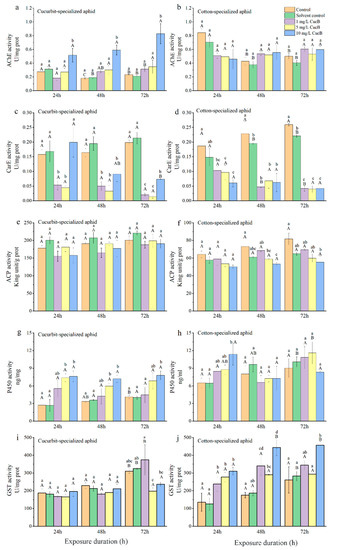

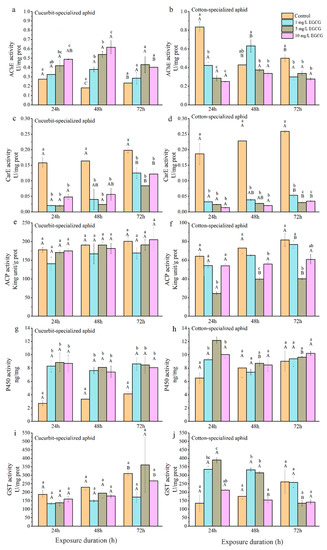

3.3.1. Acetylcholinesterase

The AChE activities in both biotypes of aphids fed on control leaves decreased at 48 h post-feeding and then increased slightly at 72 h, with the highest activity at 24 h (Table 5; Figure 3 and Figure 4). CU exhibited no significant differences between the control and treatment groups at 1 and 5 mg/L of CucB (Figure 3a). However, at 10 mg/L CucB treatment enhanced AChE activity (p < 0.05) with time. For CO, CucB lightly suppressed AChE activity at 24 h (F4,10 = 3.46, p = 0.051) post-feeding, but the effect was not significant at later stages Figure 3b). CU exhibited significantly increased AChE activity at 24 h and 48 h post-feeding on leaves treated with different concentrations of EGCG, but the activity returned to the level of the control group at 72 h (Figure 4a). AChE activity in CO were significantly inhibited at all three concentrations of EGCG at every time interval except for 48 h with 1 mg/L EGCG (Figure 4b). Thus, CucB and EGCG stimulated AChE activity in CU while it suppressed it in CO.

Table 5.

Effects of concentration and the duration exposure of CucB on EGCG on detoxifying enzyme activities.

Figure 3.

Effect of CucB on enzyme activity in Aphis gossypii in different time intervals. (a): AChE activity of CUS; (b): AChE activity of COS; (c): CarE activity of CUS; (d): CarE activity of COS; (e): ACP activity of CUS; (f): ACP activity of COS; (g): P450 activity of CUS; (h): P450 activity of COS; (i): GST activity of CUS; (j): GST activity of COS. Bars labelled with different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between concentrations in same time interval, bars labelled with different capital letters indicate significant differences between time intervals in in same concentration (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

(a): AChE activity of CUS; (b): AChE activity of COS; (c): CarE activity of CUS; (d): CarE activity of COS; (e): ACP activity of CUS; (f): ACP activity of COS; (g): P450 activity of CUS; (h): P450 activity of COS; (i): GST activity of CUS; (j): GST activity of COS. Effect of EGCG on enzyme activity in Aphis gossypii in different time intervals.Bars labelled with different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between concentrations in same time interval, bars labelled with different capital letters indicate significant differences between time intervals in in same concentration (p < 0.05).

Each bar represents mean ± SE of three biological samples from different treatments. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences at the same concentration with different treatment times, and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at different concentrations with the same treatment times (One-way ANOVA).

3.3.2. Carboxylesterase

CucB significantly decreased CarE activity in both CU and CO at all time points (Table 5; Figure 3c,d), except in CU treated with 10 mg/L CucB 24 h post-feeding (F2,6 = 0.33, p = 0.729) (Figure 3c). Within the cotton-melon aphids, EGCG induction significantly inhibited levels of the CarE (Table 3; Figure 4c,d). For example, CarE activities in CO were 0.03, 0.02, and 0.01 U/mg at 24 h, showing respectively 82.80%, 87.41%, and 92.50%, reductions of activity compared with the control group. Moreover, duration of EGCG exposure also significantly altered CarE levels in cotton-melon aphids (Table 5).

3.3.3. Acid Phosphatase

No significant differences in ACP activity (p > 0.05) were found among CU fed on the plants treated varying concentrations of CucB and EGCG (Table 5; Figure 3e,f and Figure 4e). However, CucB suppressed ACP activity in CO at 48 and 72 h post-feeding. The suppression was more robust at higher concentrations (Table 5; Figure 4f).

3.3.4. Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases

The P450 activities increased significantly in CU fed on leaves treated with three different concentrations of CucB (Table 5; Figure 3g), and in CO at 24 h post-feeding fed with 10 mg/L of CucB (Figure 4h). However, the P450 activity was similar to that in the control group for CO at other time points (Table 3; Figure 3h). The treatment of EGCG induced a concentration-independent increase of P450 activity in both CU and CO when compared with the controls (Table 3; Figure 4g,h). whereas, duration of CucB and EGCG exposure showed no significantly altered P450 levels in cotton-melon aphids (Table 5).

3.3.5. Glutathione S-Transferases

After A. gossypii was fed on leaves treated with CucB, GST activity in CO was significantly increased with increasing concentrations of CucB (Table 3; Figure 3j). However, a high concentration of CucB suppressed GST activity in CU after feeding for 72 h (Table 3; Figure 3i). Like ACP, the activity of GST in CU showed no difference at any point, except under treatment with 10 mg/L EGCG for 72 h, which was much higher than that at 24 and 48 h (Table 3; Figure 4i). A statistically significant increase in GST activity was found in the treated CO for 24 and 48 h (p < 0.01). With the exception of the 10 mg/L EGCG treatment, the GST levels in the treated groups decreased to the level of the control group at 72 h (Table 3; Figure 4j).

It is worth noting that after treatment with three concentrations of EGCG and two lower concentrations of CucB (1 and 5 mg/L), there was an initial increase in the overall activity of GST in CO, followed by a decrease to control group levels. When feeding on nonhost plants, the expression of detoxification-related enzymes, such as P450 and GSTs, may be activated in response to the presence of toxic substances.

4. Discussion

Biopesticides (natural products) have emerged as a better alternative for pest control [31]. CucB and EGCG are the major secondary metabolites of host plants cucurbits and cotton, which are the host plant of two typical biotypes of the notorious agricultural pest aphid—CU and CO [14,15,38]. Accordingly, these two natural products could provide an alternative to synthetic insecticides for environmentally-friendly control of cotton-melon aphids in future. However, the effects of EGCG and CuCB on cotton-melon aphids, especially transgenerational effect, have rarely been manipulated experimentally.

This study showed the direct effects, transgenerational effects of CucB and EGCG on the biological traits and five enzymes activity of the cotton-melon aphid. Our results clearly demonstrate that 5 mg/L CucB and 10 mg/L EGCG were effective in inhibiting development, survival, and fecundity in CU and CO. The results, thus, indicate that CucB and EGCG can directly and significantly reduce the population-level fitness of A. gossypii with stronger effects at higher concentrations. These results are consistent with previously published work on the toxicity of CucB [21], in which CucB was part of an artificial diet. In our study, we used a leaf-dipping method. In another study, a sub-lethal concentration of cucurbitacin E altered the percentages of survival, pupation, fecundity, and egg hatchability of Spodoptera litura [57]. Therefore, our results further confirm the positive effects of these plant-derived chemicals on A. gossypii and demonstrate their importance in defense against herbivory insect [58].

Furthermore, previous reports have suggested that cotton and cucumber serve as alternate hosts for CU and CO, respectively, under food deficiency [59]. The ability of aphids, especially host-specialized populations, to recognize and respond to nonhosts is vital for their survival and fitness [36]. Overcoming host’s secondary defense metabolites is critical for adaptation to an unexpected host [3,37]. Our results showed that cotton is not a suitable host for CU after parental exposure to CucB. CucB decreased the fitness in CO when fed with cucumber leaves with a higher concentration of CucB. However, EGCG could slightly improve the adaptability of A. gossypii on nonhosts. In this study, exposure to EGCG delayed the development of F1 of cotton-melon aphid on non-host plant, but also showed to increase its fecundity. However, it was hard to establish CU and CO populations on nonhost plants after treatment with EGCG or CucB. These results provide evidence that CucB and EGCG can indirectly affect the population-level fitness of these two host-specialized aphids following reciprocal host transfers. In practice, we needed to consider that EGCG in the field for host plants may lead to an ecological problem—the population-level fitness of non-host adaption maybe improved when exposed to EGCG.

CucB and EGCG has been recognized as an excellent organic pesticide, however, few studies have been conducted on the role of CucB and EGCG in animal subjects [21,25]. P450s, GSTs, CarE, AchE, and ACP have been reported to be involved in the xenobiotic metabolism of insects. The inhibition of AChE produces a generalized synaptic collapse that can lead to insect death [30]. AChE is responsible for catalyzing the hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine leading to the release of acetate and choline [60,61]. ACP catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphoric acid to produce inorganic phosphoric acid under acidic conditions, which is often related to nutrient uptake [62]. P450 enzymes have important roles in the synthesis and degradation of ecdysteroids and juvenile hormones and in the metabolism of foreign chemicals of natural or synthetic origin [63]. GSTs belong to a multigene family of dimeric, multifunctional proteins that have a central role in detoxification of xenobiotic compounds, including drugs, herbicides, and insecticides [64]. Furthermore, the elevated levels of GSTs are associated with tolerance to insecticides [65].

It is worth noting that after treatment with three concentrations of EGCG and two lower concentrations of CucB (1 and 5 mg/L), there was an initial increase in the overall activity of GST in CO, followed by a decrease to the control group levels. When feeding on nonhost plants, the expression of detoxification-related enzymes, such as P450 and GSTs, may be activated in response to the presence of toxic substances [66]. We speculate that feeding on a natural diet containing CucB and EGCG causes changes in the expression of insect detoxification enzymes or enzyme activities as well as related detoxification mechanisms, which would further weaken the ability of aphids to metabolize. In plants, P450 enzymes involved in secondary metabolism plays a role in cucurbitacin biosynthesis [67,68]. CucB and EGCG significantly altered the levels of few detoxifying enzymes. They increased the levels of AChE and P450 in CU, decreased the levels of AChE (in CO), CarE, and ACP. EGCG and CucB were found to increase activity of P450 during the early feeding stage (24 h), but diminished the activity to normal levels at 48 and 72 h. The alteration in GST activity varied with the concentration of CucB. GST activity was stimulated by CucB in CO, while a contrasting effect was observed in CU with a gradual increase in feeding time. Low concentrations of EGCG increased GST activity up until 48 h in CO, but did not affect GST activity in CU. Interestingly, most detoxification enzymes in cotton-melon can be significantly altered by low concentrations of EGCG and CucB within short duration, which showed potential in preventing and controlling this pest. Our results showed an overwhelming inhibition of CarE activity by CucB and EGCG, indicating loss of detoxifying ability and increased vulnerability to stressors in CU and CO. Such an effect may be due to the absence of a mechanism to metabolize CucB and EGCG in A. gossypii. We speculate that feeding on a natural diet containing CucB and EGCG causes changes in the expression of insect detoxification enzymes or enzyme activities as well as related detoxification mechanisms, which would further weaken the ability of aphids to metabolize.

Hereby, we conclude that differences in biochemical responses of aphids to xenobiotics are influenced by a variety of factors such as the nature and dosage of the test substance, the age and biotype of the insect, and the type of enzyme being assayed. Our results showed that CucB and EGCG had direct and indirect impact on cotton-melon aphids.

5. Conclusions

This article aimed to provide a preliminary study on the toxic effects of CucB and EGCG on A. gossypii with the focus on population-level fitness, and detoxification enzymes to theoretical support for the subsequent development of pesticides using them as effective ingredients. In summary, CucB and EGCG can significantly reduce the population-level fitness of A. gossypii, affect their ability to adapt to nonhost plants and alter the levels of some detoxifying enzymes. Based on the presented data and subsequent results, CucB and EGCG have the potential to be developed into new biopesticides against the notorious aphids. A future study is necessary to exploit these potential biopesticides through a comparative evaluation with other known bio-pesticides, especially the transgenerational effects of EGCG. This may also have important implications in pest management efforts to control A. gossypii.

Author Contributions

S.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. J.C.: Visualization, Supervision. J.L.: Supervision. L.N.: Methodology, Software. H.H.: Supervision. C.M.: Investigation, Data curation, Validation. C.Z.: Data curation, Software, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31972355).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We give thanks to Main Faisal Nazir, Jiao Shang and Changcai Wu (State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Institute of Cotton Research, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for assistance with English language idioms. We also give thanks to Baoyin Wang (Hangzhou Handu Industrial Design Co., Ltd., Hang Zhou, China) for helping with the creation of the Graphical Figure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest for the current study.

References

- Allen-Perkins, A.; Estrada, E. Mathematical modelling for sustainable aphid control in agriculture via intercropping. Proc. R. Soc. A 2019, 475, 20190136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züst, T.; Agrawal, A.A. Mechanisms and evolution of plant resistance to aphids. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 15206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, R.; Eastop, V.F. Aphids on The World’s Trees—An Identification and Information Guide; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mossa, A.T.H.; Mohafrash, S.M.M.; Chandrasekaran, N. Safety of Natural Insecticides: Toxic Effects on Experimental Animals. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, F. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckel, D.G. Insecticide Resistance After Silent Spring. Science 2012, 337, 1612–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubran, E.; Delorme, R.; Augé, D.; Moreau, J.-P. Insecticide resistance in Cotton Aphid Aphis gossypii (Glover) in the Sudan Gezira. Pestic. Sci. 1992, 35, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, K.L.; Kansiime, M.K.; Mugambi, I.; Nunda, W.; Chacha, D.; Rware, H.; Makale, F.; Mulema, J.; Lamontagne-Godwin, J.; Williams, F.; et al. Why don’t smallholder farmers in Kenya use more biopesticides? Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 3615–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Benton, T.G.; Graham, R.I.; Grzywacz, D. Pest Control: Biopesticides’ Potential. Science 2013, 342, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheke, R.A. New pests for old as GMOs bring on substitute pests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8239–8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, P.G. Pesticidal natural products—Status and future potential. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesey, I.W.; Jiang, N.; Weißflog, J.; Winz, R.; Svatoš, A.; Wang, C.-Z.; Hansson, B.S.; Knaden, M. Plant-Based Natural Product Chemistry for Integrated Pest Management of Drosophila suzukii. J. Chem. Ecol. 2019, 45, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerda, H.; Carpio, C.; Ledezma-Carrizalez, A.C.; Sánchez, J.; Ramos, L.; Muñoz-Shugulí, C.; Andino, M.; Chiurato, M. Effects of Aqueous Extracts from Amazon Plants on Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) and Brevicoryne brassicae (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Laboratory, Semifield, and field trials. J. Insect Sci. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R. Effects of Catechin in Culture and in Cotton Seedlings on the Growth and Polygalacturonase Activity of Rhizoctonia solani. Phytopathology 1978, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, R.L.; Metcalf, R.A.; Rhodes, A.M. Cucurbitacins as kairomones for diabroticite beetles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 3769–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, S.; Kaul, S.C.; Wadhwa, R. Cucurbitacin B and cancer intervention: Chemistry, biology and mechanisms (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2018, 52, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Ho, C.-T.; Huang, Q. Chemistry and Health Effect of Tea Polyphenol (−)-Epigallocatechin 3-O-(3-O-Methyl)gallate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 5374–5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, C.R.; Hoffman, C.A. Chemical Feeding Deterrent Mobilized in Response to Insect Herbivory and Counteradaptation by Epilachna tredecimnotata. Science 1980, 209, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, C.P.; Jones, C.M. Cucumber Beetle Resistance and Mite Susceptibility Controlled by the Bitter Gene in Cucumis sativus L. Science 1971, 172, 1145–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, U.; Aeri, V.; Mir, S.R. Cucurbitacins—An insight into medicinal leads from nature. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2015, 9, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, H.K.; Shan, T.; Chen, X.; Ma, K.; Shi, X.; Desneux, N.; Biondi, A.; Gao, X. Impact of the secondary plant metabolite Cucurbitacin B on the demographical traits of the melon aphid, Aphis gossypii. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, C.R.; Bell, A.A.; Stipanovic, R.D. Effect of aging on flavonoid content and resistance of cotton leaves to Verticillium wilt. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 1976, 8, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikano, I.; Rosa, C.; Tan, C.-W.; Felton, G.W. Tritrophic Interactions: Microbe-Mediated Plant Effects on Insect Herbivores. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017, 55, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naasani, I.; Seimiya, H.; Tsuruo, T. Telomerase inhibition, telomere shortening, and senescence of cancer cells by tea catechins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 249, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzzolin, L.; Zaffani, S.; Benoni, G. Safety implications regarding use of phytomedicines. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006, 62, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, P.W.; Stevenson, P.C.; Simmonds, M.S.; Sharma, H.C. Phenolic compounds on the pod-surface of pigeonpea, Cajanus cajan, mediate feeding behavior of Helicoverpa armigera larvae. J. Chem. Ecol. 2003, 4, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayati, A.A.; Ranson, H.; Hemingway, J. Insect glutathione transferases and insecticide resistance. Insect Mol. Biol. 2005, 14, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.S.; Rider, D.S.; Walsh, T.K.; De Vos, M.; Gordon, K.H.; Ponnala, L.; Macmil, S.L.; Roe, B.A.; Jander, G. Comparative analysis of detoxification enzymes in Acyrthosiphon pisum and Myzus persicae. Insect Mol. Biol. 2010, 19 (Suppl. 2), 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.-H.; Yu, X.-R.; Shang, Q.-L.; Shi, X.-Y.; Gao, X.-W. Oral delivery mediated RNA interference of a carboxylesterase gene results in reduced resistance to organophosphorus insecticides in the cotton Aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, A.M.; Moreira, A.C.; Lopes, B.R.; Fracola, M.F.; de Almeida, F.G.; Bueno, O.C.; Cass, Q.B.; Souza, D.H.F. Acetylcholinesterases from Leaf-Cutting ant Atta sexdens: Purification, Characterization, and Capillary Reactors for On-Flow Assays. Enzym. Res. 2019, 2019, 6139863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafiz, M.; Alam, M.; Chi, H.; Hassan, E.; Shim, J.-K.; Lee, K.-Y. Effects of Sublethal Doses of Methyl Benzoate on the Life History Traits and Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Activity of Aphis gossypii. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furk, C.; Hines, C.M. Aspects of insecticide resistance in the melon and cotton aphis, Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Ann. Appl. Biol. 1993, 123, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletto, J.; Martin, T.; Vanlerberghe-Masutti, F.; Brévault, T. Insecticide resistance traits differ among and within host races in Aphis gossypii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2010, 66, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombaert, E.; Boll, R.; Lapchin, L. Dispersal strategies of phytophagous insects at a local scale: Adaptive potential of aphids in an agricultural environment. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walling, L.L. The Myriad Plant Responses to Herbivores. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2000, 19, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.D.; Zhai, B.P.; Zhang, X.X. Specialized host-plant performance of the cotton aphid is altered by experience. Ecol. Res. 2008, 23, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, B.K.; Choudhury, P.R. Host races of the cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii, in asexual populations from wild plants of Taro and Brinjal. J. Insect Sci. 2013, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liang, X.L.; Zhao, H.Y.; Xu, T.T.; Liu, X.D. Special plant species determines diet breadth of phytophagous insects: A study on host plant expansion of the host-specialized Aphis gossypii Glover. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tang, C.; Ma, K.; Xia, J.; Song, D.; Gao, X.-W. Overexpression of UDP-glycosyltransferase potentially involved in insecticide resistance in Aphis gossypii Glover collected from Bt cotton fields in China. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.A.; Leather, S.; Pickup, J.; Harrington, R. Mortality during dispersal and the cost of host specificity in parasites: How many aphids find hosts? J. Anim. Ecol. 2001, 67, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Luo, J.Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Lv, L.M.; Zhu, X.Z.; Li, C.H.; Cui, J.J. Identification of Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Biotypes from Different Host Plants in North China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Matsuda, K. Feeding responses of four phytophagous lady beetle species (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) to cucurbitacins and alkaloids. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2000, 35, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tallamy, D.; Stull, J.; Ehresman, N.; Gorski, P.; Mason, C. Cucurbitacins as Feeding and Oviposition Deterrents to Insects. Environ. Entomol. 1997, 26, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafiz, M.; Hassan, E.; Shim, J.-K.; Lee, K.-Y. Insecticidal efficacy of three benzoate derivatives against Aphis gossypii and its predator Chrysoperla carnea. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 184, 109653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Qi, H.; Yang, D.; Yuan, H.; Rui, C. Cycloxaprid: A novel cis-nitromethylene neonicotinoid insecticide to control imidacloprid-resistant cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 132, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Nahhal, Y.; El-Dahdouh, N. Toxicity of Amoxicillin and Erythromycin to Fish and Mosquitoes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 10, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H. Life-Table Analysis Incorporating Both Sexes and Variable Development Rates Among Individuals. Environ. Entomol. 1988, 17, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignani, S.; Rosa, R. The moving block bootstrap to assess the accuracy of statistical estimates in Ising model simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995, 92, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.W. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Teach. Stat. 2010, 23, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akca, I.; Ayvaz, T.; Yazici, E.; Smith, C.L.; Chi, H. Demography and population projection of Aphis fabae (Hemiptera: Aphididae): With additional comments on life table research criteria. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 1466–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkopru, E.P.; Atlihan, R.; Okut, H.; Chi, H. Demographic Assessment of Plant Cultivar Resistance to Insect Pests: A Case Study of the Dusky-Veined Walnut Aphid (Hemiptera: Callaphididae) on Five Walnut Cultivars. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfekih, S.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hsu, J.-C.; Belcaid, M.; Haymer, D. Identification and preliminary characterization of chemosensory perception-associated proteins in the melon fly Bactrocera cucurbitae using RNA-seq. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parimai, S.; Meinke, L.J.; Nowatzki, T.M.; Chandler, L.D.; French, B.W.; Siegfried, B.D. Toxicity of insecticide-bait mixtures to insecticide resistant and susceptible western corn rootworms (Coleoptera:: Chrysomelidae). Crop Prot. 2003, 22, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masler, E.; Rogers, S.; Chitwood, D. Developmental responses of heterodera glycines and meloidogyne incognita to fundamental environmental cues. J. Nematol. 2013, 45, 303. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, T.E.; Pham, H.M.; Barbour, J.; Tran, P.; Van Nguyen, B.; Hogan, S.P.; Homo, R.L.; Coskun, V.; Schriner, S.E.; Jafari, M. The impact of green tea polyphenols on development and reproduction in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 20, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitwood, D.J. Phytochemical based strategies for nematode control. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2002, 40, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsankar, A.; Sahayaraj, K.; Senthil-Nathan, S.; Vasantha-Srinivasan, P.; Karthi, S.; Thanigaivel, A.; Petchidurai, G.; Madasamy, M.; Hunter, W.B. Toxicity and developmental effect of cucurbitacin E from Citrullus colocynthis L. (Cucurbitales: Cucurbitaceae) against Spodoptera litura Fab. and a non-target earthworm Eisenia fetida Savigny. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 27, 23390–23401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithofer, A.; Boland, W. Plant defense against herbivores: Chemical aspects. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-D.; Xu, T.-T.; Lei, H.-X. Refuges and host shift pathways of host-specialized aphids Aphis gossypii. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanetti, R.; Zanuncio, J.; Santos, J.C.; Da Silva, W.L.P.; Ribeiro, G.; Tamara, G.; Lemes, P.G. An Overview of Integrated Management of Leaf-Cutting Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Brazilian Forest Plantations. Forests 2014, 5, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, J.; Field, L.; Vontas, J. An Overview of Insecticide Resistance. Science 2002, 298, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil-Nathan, S. Physiological and biochemical effect of neem and other Meliaceae plants secondary metabolites against Lepidopteran insects. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyereisen, R. Insect P450 enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1999, 44, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.D.; Flanagan, J.U.; Jowsey, I.R. Glutathione transferases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranson, H.; Rossiter, L.; Ortelli, F.; Jensen, B.; Wang, X.; Roth, C.W.; Collins, F.H.; Hemingway, J. Identification of a novel class of insect glutathione S-transferases involved in resistance to DDT in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Biochem. J. 2001, 359, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Ma, J.; Qin, X.; Tu, X.; Cao, G.; Wang, G.; Nong, X.; Zhang, Z. Biology, physiology and gene expression of grasshopper Oedaleus asiaticus exposed to diet stress from plant secondary compounds. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, M.; Sato, F. Unusual P450 reactions in plant secondary metabolism. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 507, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zeng, J.; Duan, L.; Xue, X.; Wang, H.; Lin, T.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, K.; Zhong, Y.; et al. Convergence and divergence of bitterness biosynthesis and regulation in Cucurbitaceae. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).