Abstract

Wear, a critical factor governing the performance and durability of mechanical systems, is typically characterized using point-contact and line-contact test configurations. However, it remains unclear whether the wear trends observed in one test configuration would be observed in the other configuration under the same nominal conditions. In this study, ball-on-disk (ASTM G99) and block-on-ring (ASTM G77) tests were conducted under an identical maximum Hertzian contact stress and sliding speed, using the same material pair and lubricating oil, to clarify which contact configuration exhibits more wear and why. The results show that, under the same Hertzian contact stress, the line-contact configuration exhibits a specific wear rate two orders of magnitude higher than the point-contact configuration, despite exhibiting a lower and more stable coefficient of friction. The disk wear is negligible and the ball shows only mild material loss, whereas the line-contact system displays wear rates several orders of magnitude higher, with the rotating ring contributing the dominant share of the total wear. White-light interferometry and scanning electron microscopy observations reveal directional, groove-dominated surface morphologies on the ball and disk, while wear on the block is confined to edge-localized regions and the worn ring surface has smooth, polished morphology. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy confirms that a Zn- and P-rich tribofilm forms exclusively on the ring surface. Finite element analysis shows stress amplification at the finite line-contact edges, explaining the observed wear severity. These results demonstrate that matching Hertzian contact stress alone is insufficient to ensure comparable wear behavior between point and line contacts.

1. Introduction

Wear is one of the most prevalent and unavoidable degradation mechanisms in mechanical systems [1,2,3], and it plays a decisive role in determining the long-term reliability and operational stability of engineering components. Failures induced by wear are commonly observed in bearings, gears, shafts, pump components, and a wide range of sliding interfaces, where repeated contact and relative motion progressively remove material from the interacting surfaces. The cumulative effect of wear not only reduces performance and efficiency but also increases maintenance costs and may lead to operational interruptions or catastrophic failures. As modern engineering systems continue to evolve toward higher loads, lighter designs, and more compact structures, understanding how materials respond to wear has become increasingly critical [4,5]. Consequently, the study of wear behavior under different contact and lubrication conditions remains a central topic in tribology.

Despite extensive research, accurately predicting or evaluating wear behavior continues to be challenging due to its multi-factorial and highly nonlinear nature. Wear is simultaneously influenced by material properties, surface topography, contact geometry, normal load, sliding speed, lubrication state, and temperature. The interactions between these variables are complex, making it difficult to isolate the contribution of any single factor [4,6]. To control such complexities and improve repeatability and comparability across studies, ball-on-disk and block-on-ring configurations have been widely adopted in tribological experiments since the 1970s, and standardized test methods have gradually been established. Among these, ASTM G99 [7] (ball-on-disk), representing a point-contact configuration, and ASTM G77 [8] (block-on-ring), representing a line-contact configuration, are two of the most established and frequently applied standards for laboratory-scale assessment of wear resistance. These standardized configurations provide consistent protocols that allow researchers to evaluate materials under controlled and well-defined conditions.

Due to their inherent geometric differences, point and line contacts display distinct characteristics in terms of normal pressure distribution, contact-area shape, and load transmission. A nominal point contact typically forms a relatively small, nearly circular or elliptical contact patch with a strongly peaked pressure field around the center point. In contrast, a nominal line contact develops an elongated, strip-like contact area whose length is much larger than its width, and the normal load is distributed predominantly along this direction [9,10,11]. These geometric distinctions lead to different subsurface stress fields, deformation modes, and wear patterns during sliding. Yet, despite the widespread use of these methods, most studies have focused on materials or lubrication effects rather than on contact geometry itself [12,13,14,15]. As a result, the fundamental differences between point and line contacts under equivalent mechanical conditions remain insufficiently understood.

Few studies have studied the effect of contact geometry (point vs. line) on friction and wear under well-matched operating conditions. For dry metal–metal sliding, a comparison between ball-on-disk and block-on-ring tests reported lower friction but higher wear rate for the line-contact configuration, but the contact stress was not matched in the two tests [16]. Recent studies on dry film lubricants (DFLs), including MoS2, tungsten-doped hydrogenated diamond-like carbon, thin dense chrome, and polytetrafluoroethylene coatings, have directly compared point- and line-contact configurations under matched Hertzian contact pressure and sliding velocity [17,18]. These studies consistently reported lower friction coefficients but higher wear rates in line-contact configurations, with the observed behavior primarily attributed to differences in transfer film formation and evolution on the surfaces. However, such transfer-film-based mechanisms are specific to solid-lubricated systems and are not directly applicable to oil-lubricated contacts. A comparison between point and line contact was reported for metal–polymer systems under dry and water-lubricated conditions which showed that the block-on-ring test configuration exhibited a higher wear rate and a lower friction coefficient than the pin-on-disk test [19]. Another study compared point and line contact in dry and oil-lubricated conditions and found that, in the line-contact configuration, the higher temperature rise caused polymer softening, which led to increased wear rate [20]. But, in these two studies the contact stress was not the same in line and point contact tests, precluding direct comparison. Only one study investigated point- and line-contact configurations under oil-lubricated conditions at matched Hertzian contact stress, and this study primarily focused on film thickness and thermal effects rather than wear [21]. Therefore, the fundamental question of how line and point contact geometries differ under liquid-lubricated conditions when operating at identical Hertzian contact stress remains unanswered.

To answer this question, this study presents a direct and tightly controlled comparison between point contact (ASTM G99) and line contact (ASTM G77) test configurations, with the applied normal loads selected to achieve the same nominal Hertzian contact stress and the sliding speed held constant to ensure comparable lubrication conditions. The two configurations were tested using the same material pair and lubricant conditions so that any differences observed were solely from contact geometry rather than external variables. This approach enabled a quantitative assessment of how geometry influences frictional response, total wear, and the spatial distribution of wear under boundary lubrication. The results clarified the geometric origins of wear behavior and helped improve how standardized tribological tests are interpreted when comparing different types of engineering contacts.

2. Experimental and Numerical Methods

2.1. Materials and Experimental Setup

The material of the samples used in this study was AISI 52100 alloy steel. AISI 52100 alloy steel is a high-carbon chromium steel widely used in rolling bearings and tribological components due to its high hardness, wear resistance, and fatigue strength. Because of its well-established mechanical and tribological properties, it is commonly adopted as a benchmark material in standardized tribological tests, including ball-on-disk and block-on-ring configurations. The steel balls were commercially purchased with a nominal hardness of HRC 60. The ring and disk specimens were machined from AISI 52100 steel bars with an initial hardness of approximately HRC 30. To maintain consistency in the hardness of the contacting bodies between the ball-on-disk and block-on-ring configurations, the block specimens used in the block-on-ring tests were subjected to commercial heat treatment at Garner Heat Treat, Inc. (Oakland, CA, USA), increasing their hardness to HRC 60 to match that of the ball. In the ball-on-disk configuration, the steel ball served as the stationary component while the disk was the moving component. In the block-on-ring configuration, the block was stationary and the ring was the moving component. The mechanical and physical properties of the samples are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mechanical and physical properties of AISI 52100 alloy steel.

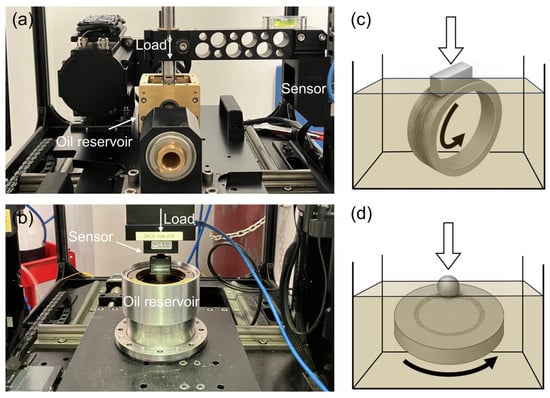

In accordance with the ASTM G99 (ball-on-disk) and ASTM G77 (block-on-ring) testing standards, the corresponding test assemblies were mounted on a tribometer (RTEC MFT-5000, San Jose, CA, USA). An overview of the experimental configurations, including both the test assemblies and schematic representations, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental setups and corresponding schematics: (a) block-on-ring test assembly, (b) ball-on-disk test assembly, (c) schematic of the block-on-ring configuration, and (d) schematic of the ball-on-disk configuration. The directions of normal load and rotational motion are indicated with arrows in the schematics.

To enable a direct comparison of wear rate between the ball-on-disk and block-on-ring tests, all controllable experimental parameters were matched as closely as possible between the two configurations, including sliding radius, surface roughness, and lubrication conditions.

In the ball-on-disk tests, the ball diameter was 9.525 mm, with the ball fixed and the disk rotating. The sliding radius, defined as the distance between the ball and the disk center, was 17.5 mm. In the block-on-ring tests, the ring had an outer diameter of 35 mm and a width of 8.75 mm. The block specimen had dimensions of 15.75 × 6.35 × 10.15 mm3, where the nominal contact length was defined by the block width of 6.35 mm.

To maintain consistency in surface roughness between the two test configurations, the surface roughness of the block was matched to that of the ball (stationary component), while the surface roughness of the disk was matched to that of the ring (rotating component). In this way, the surface topographies of the stationary and moving counterparts were kept consistent between the ball-on-disk and block-on-ring tests. The roughness parameters (Ra) of all specimens are listed in Table 2. All values in Table 2 are presented as mean ± standard deviation based on three independent line scans measured at different locations on each specimen surface.

Table 2.

Surface roughness of the ball, disk, ring, and block specimens used in this study.

All experiments were conducted under oil-lubricated conditions using a commercial automotive engine oil of the same brand and SAE 30 viscosity grade. Prior to testing, 150 mL of lubricant was added to the oil reservoir for both the ball-on-disk and block-on-ring tests, which was sufficient to ensure adequate lubrication throughout the experiments.

To avoid undesired wear caused by dry contact at the initial stage of testing, a running-in procedure without load was performed before applying the normal load. Specifically, the specimens were rotated at the prescribed speed for 10 revolutions without contact but in the presence of lubricant, ensuring that a sufficient oil film was established on the contact surfaces prior to loading.

2.2. Tribological Test

Based on the dimensions of the test components, the normal loads for the ball-on-disk and block-on-ring configurations were determined by matching the maximum Hertzian contact stress, which was set to 690 MPa for both contact types. The normal load was 3.3 N for the point-contact configuration and 1500 N for the line-contact configuration. The rotational speed was fixed at 100 rpm for both contact geometries. In the block-on-ring configuration, the ring radius was 17.5 mm, while in the ball-on-disk configuration the wear track on the disk was located at the same radius. Accordingly, the linear sliding speed was identical in both cases (0.18 m s−1).

Different force sensors were used for the two test configurations. For the ball-on-disk tests, the normal force sensor had a range of 0.1–10 N with a resolution of 0.1 N, and the friction force sensor had the same range and resolution. For the block-on-ring tests, the normal force sensor had a range of 50–5000 N with a resolution of 0.25 N, while the friction force sensor had a range of 10–1000 N with a resolution of 0.1 N. The data acquisition sampling frequency was 100 Hz. The coefficient of friction (COF) was calculated from the ratio of friction force to normal force.

All experiments were conducted under laboratory ambient conditions with an initial temperature of 25 °C. No external cooling was applied, and the test components were allowed to undergo natural temperature rise during sliding. During the experiments, lubricant temperature was measured using a combination of infrared thermography and a thermocouple thermometer. Lubricant temperature in the point-contact configuration remained close to room temperature (25 °C). In contrast, in the line-contact configuration, frictional heating caused the oil temperature to rise rapidly and reach a steady-state value within the first 16 min of sliding, stabilized in the range of 86–88 °C for all test durations.

Based on the test conditions and material properties, lubricant film thickness was estimated using classical elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) theory. At the start of the tests, when the temperature was the same for both contact geometries, the film thickness was 0.106 μm for ball-on-disk and 0.219 μm for block-on-ring. The block-on-ring film thickness was then recalculated with the lubricant viscosity at the measured steady-state temperature of 86 °C to be 0.034 μm. All three estimated film thickness values are lower than the composite average roughness of the surfaces of 0.5 μm. This indicates that both configurations operated predominantly under boundary lubrication conditions.

Ball-on-disk and block-on-ring tests were performed for durations of 1, 2, 4, and 8 h to investigate the time-dependent evolution of wear. Each test was repeated three times to ensure the reproducibility of the results.

2.3. Wear Characterization Methods

After tribological testing, the worn surfaces were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to characterize the wear morphology and identify dominant wear features. A Zeiss Gemini SEM 500(Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany) was used for surface morphology observation, and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was employed to analyze the elemental composition of the worn surfaces.

While SEM and EDS provided qualitative insights into wear morphology and material transfer, quantitative evaluation of wear required determination of wear volume. To obtain the wear volume as accurately as possible, at least two independent measurement methods were employed for each component to cross-validate the experimental results. The wear measurement methods used for each specimen are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of wear measurement methods used for the ball, disk, ring, and block specimens.

Wear characterization was conducted using a Leica DM2500 M optical microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), an RTEC white-light interferometer (Rtec Instruments, San Jose, CA, USA), and a Bruker Dektak XT 3D profilometer (Bruker Nano Surfaces, Tucson, AZ, USA), along with mass loss measurements, where the ring mass was measured with a scale before and after testing and the mass reduction was used to quantify wear.

The results obtained from different measurement techniques were cross validated to ensure the reliability of the wear data. When consistent results were obtained from different methods, the method providing the highest spatial resolution and direct three-dimensional surface information was selected for wear rate calculation. In cases where discrepancies were observed, priority was given to the method that directly captured the wear geometry and was least affected by surface roughness or geometric assumptions.

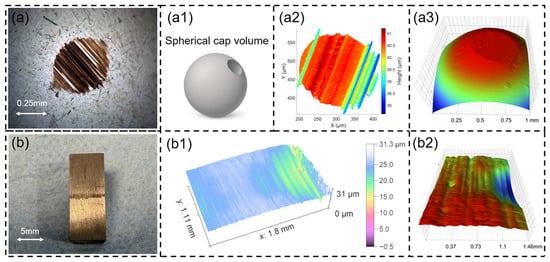

Figure 2 illustrates the wear measurement procedures for the stationary components (the ball and the block) in the ball-on-disk and block-on-ring tests. Because of the small initial mass and extremely low wear of both specimens, the mass loss method was not applicable for accurate wear quantification.

Figure 2.

Wear volume measurement methods for the stationary components (ball and block). (a) Optical image of the ball wear scar; (a1) spherical cap model used for ball wear volume calculation; three-dimensional topography and reconstruction of the ball wear scar obtained from (a2) white-light interferometry and (a3) contact profilometry. (b) Optical image of the worn block surface; three-dimensional surface topography of the block wear scar obtained by (b1) white-light interferometry and (b2) contact profilometry.

For the ball, three different measurement methods were employed. In Figure 2(a1), the conventional spherical cap method based on the wear scar diameter was applied; however, this method was found to be inaccurate due to the rough and non-ideal geometry of the wear scar surface. In Figure 2(a2), the surface topography of the wear scar was acquired using a white-light interferometer, and the wear volume was calculated using a MATLAB-based three-dimensional integration algorithm, which accounts for the actual surface roughness and provides improved accuracy. In Figure 2(a3), the wear scar was further measured using a contact profilometer, and the three-dimensional data were processed using the same MATLAB algorithm (MATLAB R2022a, The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Across all experiments, the maximum deviation between wear volumes measured by contact profilometry and white-light interferometry was less than 3%. However, due to its relatively slow scanning speed, the contact profilometer was not selected as the primary method for ball wear quantification. Based on these considerations, the wear volume of the ball reported in this study was determined from the three-dimensional surface topography obtained by white-light interferometry.

For the block, the wear morphology was highly irregular and could not be evaluated using simple geometric assumptions. Therefore, as shown in Figure 2(b1,b2), only the white-light interferometer and the contact profilometer were used to acquire the three-dimensional surface topography, and the wear volume was calculated through numerical integration using MATLAB. The wear volumes obtained from the two topography-based methods differed by less than 3% across all tested conditions. Based on these considerations, the wear volume of the block reported in this study was determined from three-dimensional surface topography obtained by white-light interferometry, due to its higher measurement efficiency and larger areal coverage.

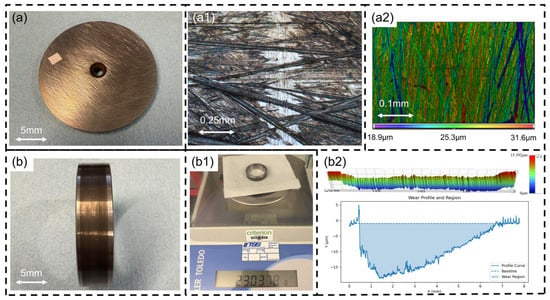

Figure 3 illustrates the wear measurement procedures for the moving components (the disk and the ring) in the ball-on-disk and block-on-ring tests. Figure 3a shows the wear characterization of the disk. Because the wear track on the disk surface was extremely shallow, it could only be faintly observed by naked eye through light reflection. In Figure 3(a1), optical microscopy reveals that the wear track did not significantly alter the surface profile, and the original machining marks remained clearly visible, indicating that the surface experienced only slight polishing rather than severe material removal. In Figure 3(a2), white-light interferometry also shows only weak indications of wear. As a result, although disk wear could be visually detected, its wear volume could not be quantified reliably. Therefore, the wear rate of the disk was not calculated or analyzed.

Figure 3.

Wear measurement methods for the moving components: (a) optical image of the worn disk; disk wear characterized by (a1) optical microscopy and (a2) white-light interferometry; (b) optical image of the worn ring; ring wear measured by the (b1) mass loss method and (b2) contact profilometry.

By contrast, wear of the ring was pronounced and could be accurately quantified using both the mass loss method and the contact profilometry method, as shown in Figure 3(b1,b2). In the contact profilometry method, the cross-sectional wear profile of the ring was obtained from three-dimensional height data, and the wear area was determined by integrating the depth profile relative to the unworn reference surface. The total wear volume of the ring was then calculated by multiplying the cross-sectional wear area by the circumferential length of the wear track along the ring. Across all measurements, the difference between wear volumes obtained from mass loss measurements and surface profile integration was less than 2%. Based on these considerations, the wear volume of the ring reported in this study was determined primarily using the mass loss method, as it captures the wear over the entire circumferential sliding track, whereas surface topography measurements were limited to discrete locations.

Using the wear volumes measured on the ball, ring, and block, the specific wear rate k was calculated as

where V is the wear volume, N is the applied normal load, and L is the cumulative sliding distance. All wear comparisons presented in this work are based on the specific wear rate, ensuring that differences in wear behavior reflect intrinsic material and contact effects rather than differences in loading conditions.

k = V/(N·L),

2.4. Numerical Simulation of Wear (FEM Analysis)

To better understand the mechanisms underlying the observed wear behavior, finite element simulations (FEM) were performed. While tribological experiments provide the final wear outcomes, the stress distribution and contact behavior during sliding cannot be directly observed. Therefore, FEM was employed to analyze the stress field and contact characteristics within the contact region, providing mechanistic insights into how mechanical loading influences the wear results.

The finite element analyses were performed using Abaqus 2025. The geometry and assembly were constructed based on the actual specimen dimensions. The material was modeled as AISI 52100 bearing steel, with a Young’s modulus of 210 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3. The loading conditions and prescribed motions were defined to match the experimental settings. An eight-node linear brick element (C3D8R) was used for meshing. Mesh independence was verified by comparing results obtained using coarse and refined meshes, and the maximum contact stress showed a difference of less than 2%, confirming mesh-independent behavior.

To capture the time-dependent evolution of the coupled stress–wear response, FEM simulations were performed using the built-in wear module in Abaqus 2025. The dynamic evolution of stress and wear is shown in Supplementary Videos S1–S4.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Coefficient of Friction and Wear Rate

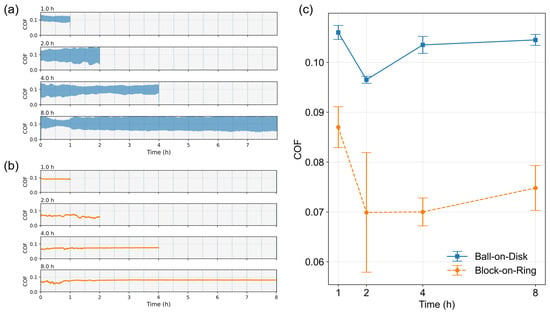

Under oil-lubricated conditions, Figure 4a shows that the ball-on-disk tests exhibit markedly larger COF fluctuations and a higher average COF throughout the sliding process. By contrast, Figure 4b demonstrates that the block-on-ring tests exhibit only minor COF fluctuations. Although some instability appears at the initial stage, the COF gradually stabilizes as steady-state sliding is reached.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the coefficient of friction (COF) under oil-lubricated conditions at different sliding durations. (a) COF–time curves of the ball-on-disk tests at sliding durations of 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 8 h. (b) COF–time curves of the block-on-ring tests at the same sliding durations. (c) Average COF values calculated from tests run to different durations for both contact configurations. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the duration-averaged COF obtained from three repeated tests.

The average COF values over different sliding durations are summarized in Figure 4c. Each test condition was repeated three times, yielding a total of 12 datasets for both configurations. Accordingly, the average COF at 1 h was calculated from 12 datasets, that at 2 h from 9 datasets, and so on. The duration-averaged results indicate that, for both ball-on-disk and block-on-ring, the COF during the first hour is higher than that during the second hour, after which it gradually approaches a steady value. It is noted that the scatter in the average COF for the 2 h block-on-ring test is larger than that at longer durations, likely due to the greater variation in the contact condition as it evolves during the early stages of sliding.

These results demonstrate that, under identical maximum Hertzian contact stress, the line-contact configuration exhibits an average COF that is 28% lower than the average COF in the point-contact configuration. This behavior agrees with previous findings reported for both dry systems and oil-lubricated contacts [16,17,21]. In solid-coated or dry-contact systems, the lower friction in line contact has been attributed to the formation and stabilization of transfer films. In contrast, under oil-lubricated conditions, the reduced friction observed in the line-contact configuration was primarily associated with higher lubricant temperatures, which reduce lubricant viscosity and consequently lower friction.

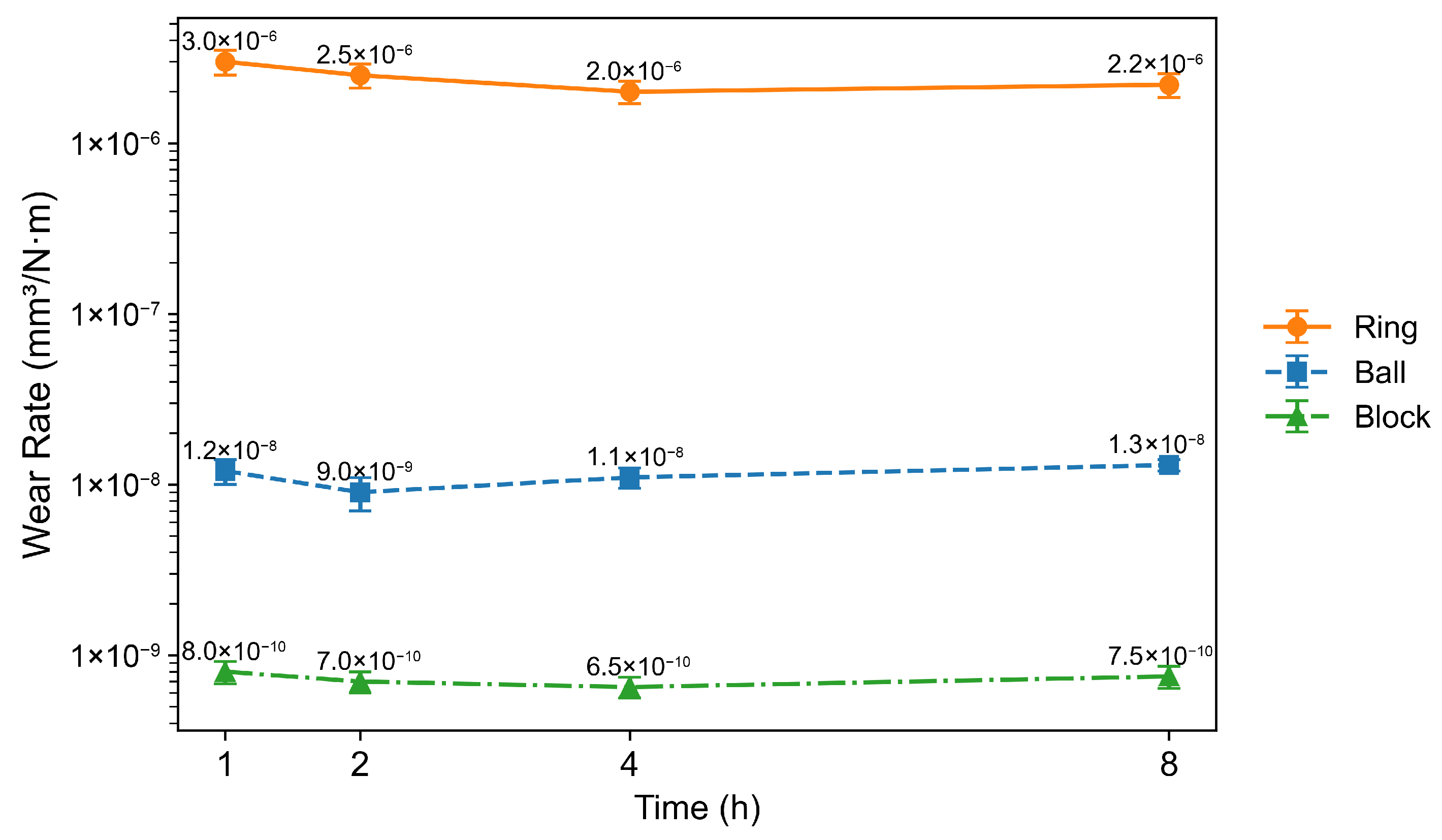

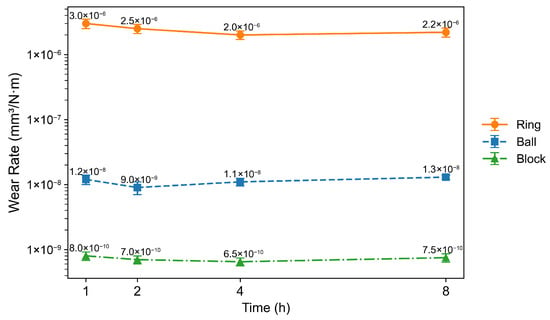

The wear results are reported in Figure 5 which shows that the block-on-ring (line-contact) configuration exhibits a specific wear rate approximately two orders of magnitude higher than that of the ball-on-disk (point-contact) configuration. This trend is consistent with a previous study comparing wear behavior of DFLs under point- and line-contact configurations [17]. In that study, the lower wear in line contact was attributed to enhanced transfer film formation associated with the larger nominal contact area under solid-film-lubricated conditions. Under liquid-lubricated conditions, however, although differences in friction behavior between point and line contacts have been discussed, direct experimental comparisons of wear rates between the two contact geometries have not been reported.

Figure 5.

Stage-wise specific wear rates of the ring, ball, and block under oil-lubricated conditions at different sliding durations. Error bars represent the standard deviation obtained from three repeated tests.

Although the line-contact configuration exhibits a lower coefficient of friction, it simultaneously shows a significantly higher wear rate. This behavior can be rationalized by the coupled effects of frictional heating, lubricant viscosity, and film thickness. From an energetic perspective, frictional heating is governed by the total frictional energy dissipation rather than by the friction coefficient alone. Based on the fundamental definition of mechanical work in sliding contact, the frictional work input is defined as

where μ is the friction coefficient, N is the normal load, L is the sliding distance [22]. In the line-contact configuration, although the friction coefficient is lower, the substantially higher applied normal load results in increased frictional energy input, leading to more severe local thermo-mechanical conditions at the interface. The temperature increase reduces lubricant viscosity, which decreases shear resistance and leads to a lower friction coefficient. However, the reduced viscosity also results in a thinner lubricant film, increasing the likelihood of local metal-to-metal contact and thereby accelerating wear. Consequently, friction and wear respond differently to changes in temperature and viscosity, and a lower friction coefficient does not necessarily imply lower wear.

W = μ N L

An additional noteworthy observation is that, in the block-on-ring system, the rotating ring exhibits a substantially higher wear rate than the stationary block. This behavior is contrary to the conventional expectation [23,24,25] that stationary components should accumulate more wear due to continuous contact, whereas any given point on a rotating component only experiences intermittent contact. The lower hardness of the ring relative to the block is expected to contribute to the higher wear of the ring to some extent. However, the wear rate of the ring exceeds that of the block by approximately four orders of magnitude, whereas the hardness difference between the two materials is only about a factor of two. According to the Archard wear equation, in which the wear volume scales linearly with the applied load and inversely with material hardness, such a large disparity in wear rate cannot be explained by hardness alone. However, our results are consistent with several previous block-on-ring studies [26,27] that also reported higher wear of the rotating ring than the stationary block. The underlying mechanisms responsible for this behavior were not discussed in those studies, suggesting future work is needed to understand the observations.

3.2. Surface Morphology of the Specimens

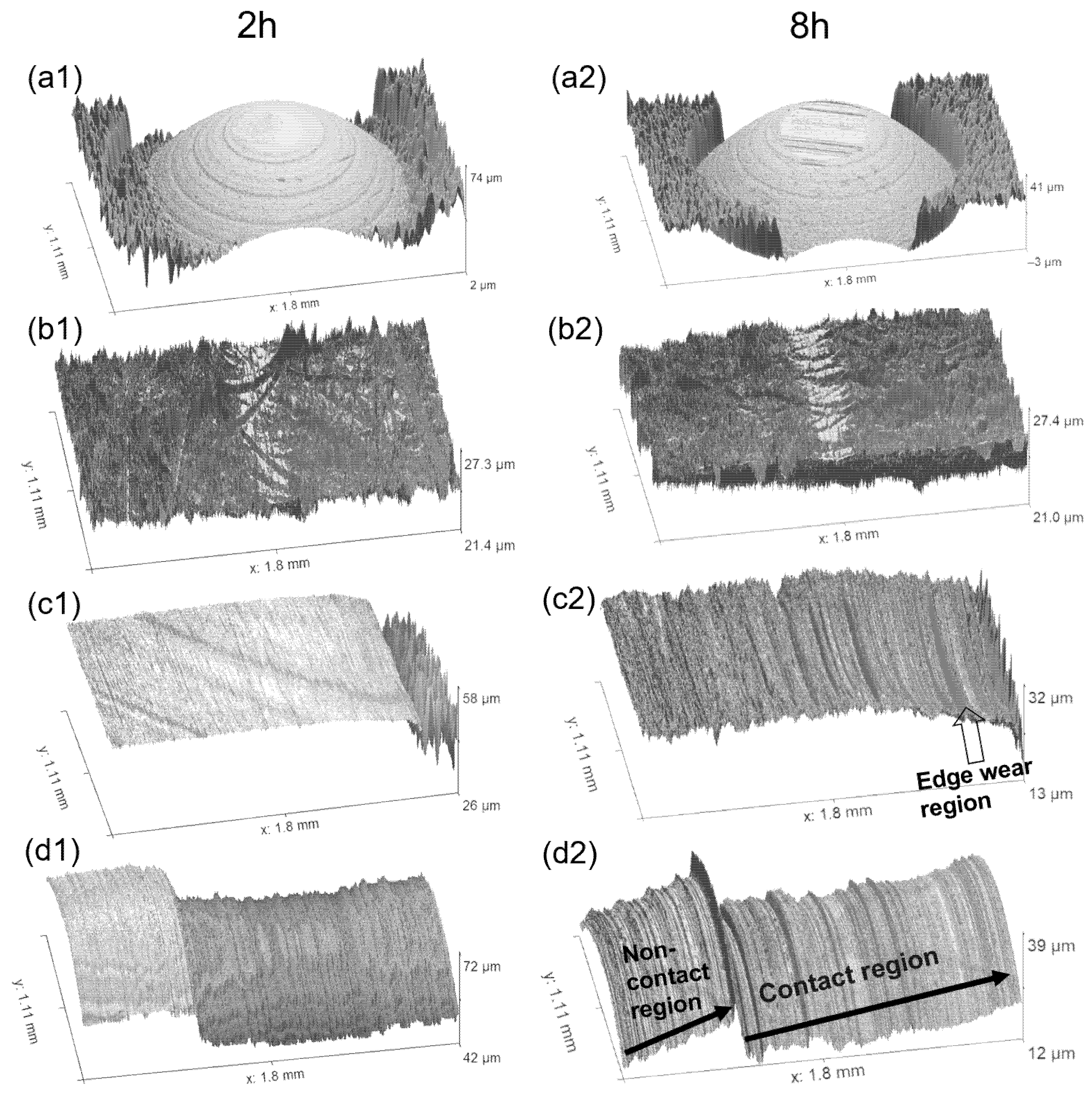

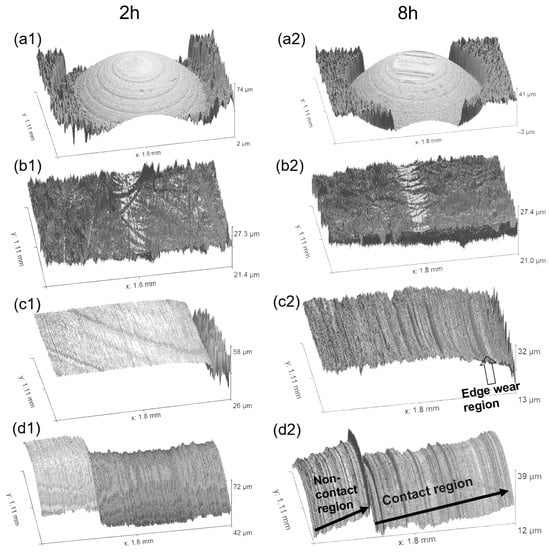

Figure 6 presents the post-test surface morphologies of the specimens after 2 h and 8 h of sliding, characterized by white-light interferometry. The worn surface of the ball is shown in Figure 6(a1,a2). Pronounced sliding-induced grooves are clearly observed within the wear scar, indicating a rough and non-uniform surface morphology. Compared with the 2 h test, the wear of the ball after 8 h is noticeably more severe.

Figure 6.

Post-test surface morphologies of the specimens after 2 h and 8 h of sliding, measured by white-light interferometry: (a1,a2) ball surface, (b1,b2) disk surface, (c1,c2) block surface, and (d1,d2) ring surface. The left and right columns correspond to the results after 2 h and 8 h, respectively. The vertical height scale is independently adjusted for each image. Note that the center of the contact is towards the left in the block images and towards the right in the ring images.

For the disk, as shown in Figure 6(b1,b2), the overall wear remains relatively mild, and only a faint wear track can be identified. Nevertheless, the wear after 8 h is slightly more pronounced than that observed after 2 h.

Figure 6(c1,c2) shows the worn surface of the block, captured at the edge of the contact region with the ring. Although the contact in a block-on-ring configuration is often idealized as a line or rectangular contact area, mechanical analyses of finite-length line contacts have shown that the free edges induce strong stress concentration at the contact ends due to the absence of lateral constraint [28]. As a result, material removal is preferentially localized near the two ends of the finite line contact, where elevated local stresses arise due to edge effects. In contrast, the central region of the contact exhibits substantially lower surface modification, with no pronounced wear grooves or measurable material loss observed in the white-light interferometry measurements. As shown in Figure 6(c2), material removal is predominantly confined to the edge regions, while the central area retains surface features comparable to the unworn state.

The wear morphology of the ring further supports this observation. As shown in Figure 6(d1,d2), the maximum wear depth is localized near the edges of the contact region, while the contact region exhibits pronounced surface height variations compared with the adjacent non-contact region along the sliding direction (x-axis). This feature is particularly evident in the 2 h test. In addition, under the high normal load of 1500 N and during the 8 h test, severe stress concentration at the contact edges leads to pronounced plastic deformation of the ring surface.

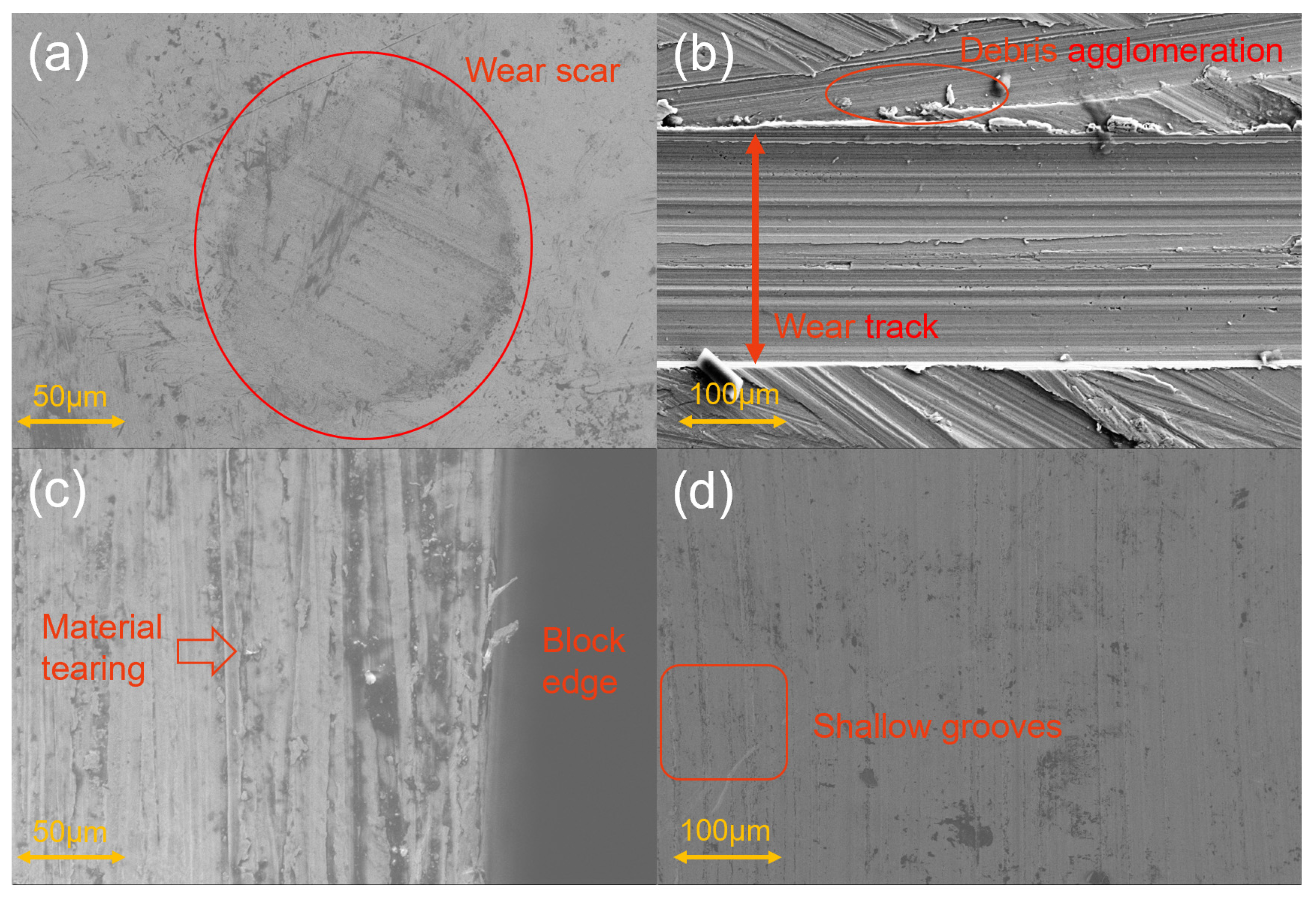

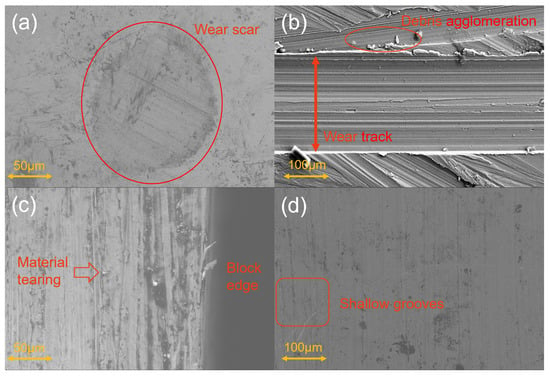

Figure 7 shows SEM micrographs of the worn surfaces of the ball, disk, block, and ring after testing. As shown in Figure 7a, the wear scar on the ball is shallow and weakly defined at the examined magnification. Only faint and discontinuous sliding marks are visible within the contact region, and no pronounced surface damage or debris accumulation is observed.

Figure 7.

SEM micrographs of the worn surfaces: (a) ball, (b) disk, (c) block, and (d) ring. Specific wear scar features are identified and labeled in red.

The disk surface (Figure 7b) exhibits well-defined and continuous grooves aligned with the sliding direction across the wear track. The grooves extend over the contact region with relatively uniform width and spacing. At this scale, no large cracks, delamination features, or surface spalling are observed.

In contrast, Figure 7c reveals a non-uniform wear morphology on the block surface near the wear track edge. Pronounced material removal and localized surface damage are observed near the sliding track edge, whereas the area farther from the edge within the field of view exhibits comparatively milder wear, characterized by shallow grooves aligned with the sliding direction.

The ring surface (Figure 7d) appears comparatively smooth after testing, with shallow grooves oriented along the sliding direction. Compared with the block surface, no pronounced debris agglomeration, surface tearing, or large-scale surface damage is observed. The overall surface morphology of the ring remains relatively uniform along the wear track.

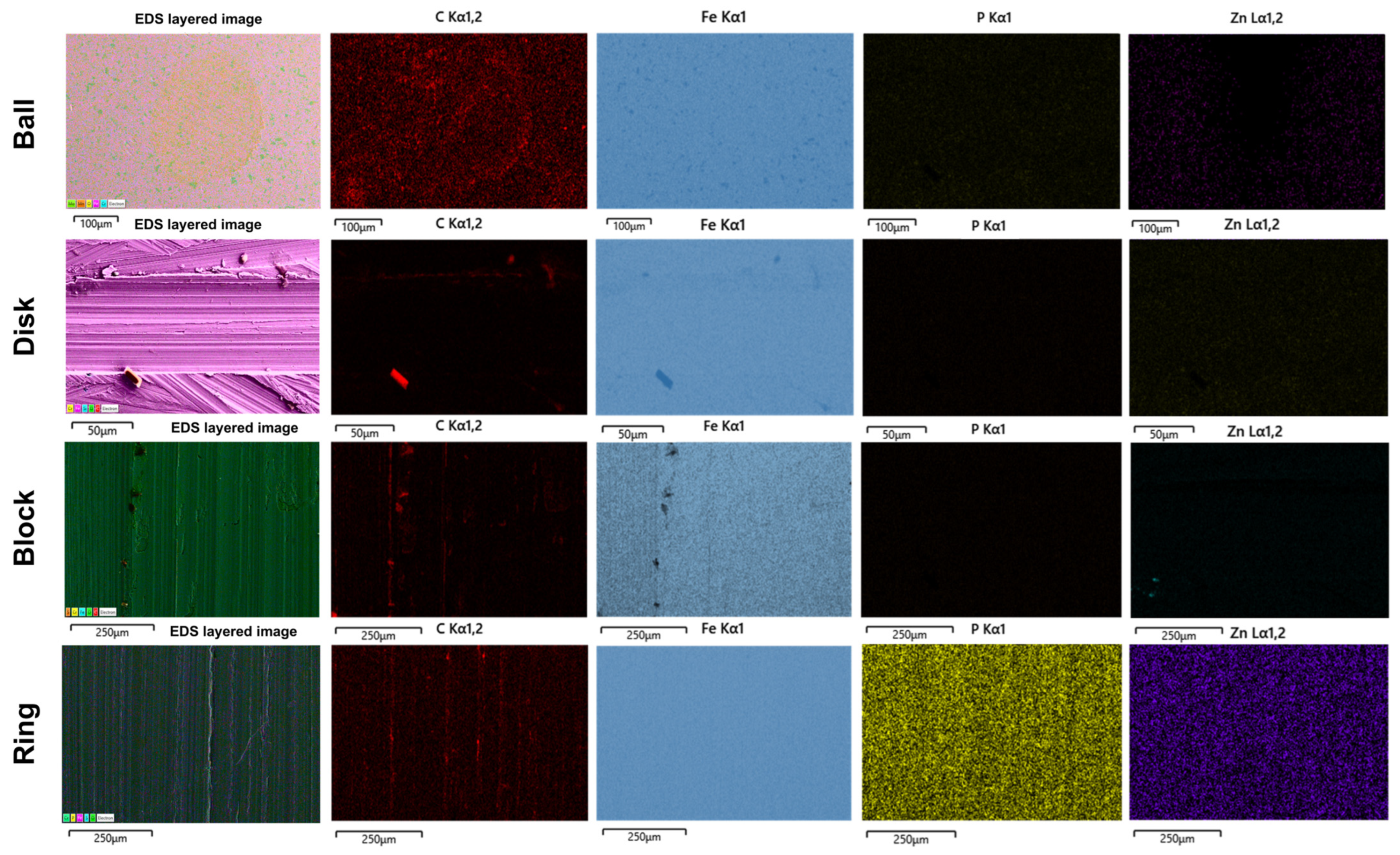

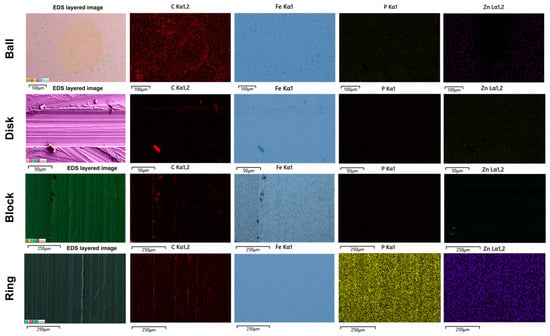

EDS elemental mapping was performed on all four contacting components to examine the distribution of anti-wear additive elements, and the result is shown in Figure 8. Because a commercial engine oil was used as the lubricant, the presence of Zn and P originating from ZDDP-type anti-wear additives is expected [29,30]. The ring surface exhibits a pronounced and nearly continuous enrichment of Zn and P along the wear track, together with a uniform Fe background. The spatial co-localization of Zn and P on the ring surface is consistent with the formation of a ZDDP-derived tribofilm on this component.

Figure 8.

EDS elemental mapping of the worn surfaces of the ball, disk, block, and ring, showing the distributions of C, Fe, P, and Zn.

The preferential enrichment of Zn and P observed on the ring surface is likely associated with the local contact conditions in the ring–block configuration. Although the maximum Hertzian contact stress was matched between the point- and line-contact tests, the lubricant temperature in the ring–block configuration was substantially higher than that in the ball–disk configuration under otherwise comparable conditions. Elevated temperature, combined with sustained sliding and shear, is known to promote shear-assisted tribochemical reactions of ZDDP-type additives and may therefore contribute to the formation and retention of an additive-derived tribofilm on the ring surface [29,30]. In addition, the continuous rotation of the ring results in repeated exposure of fresh metallic surface and more uniform sliding conditions, which can facilitate ongoing additive activation and stabilize tribofilm growth, whereas the stationary block experiences localized contact and pronounced edge effects that may hinder the development or retention of a continuous tribofilm.

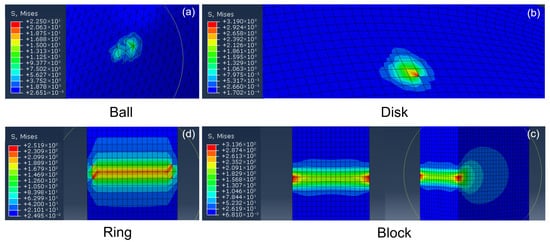

3.3. FEM

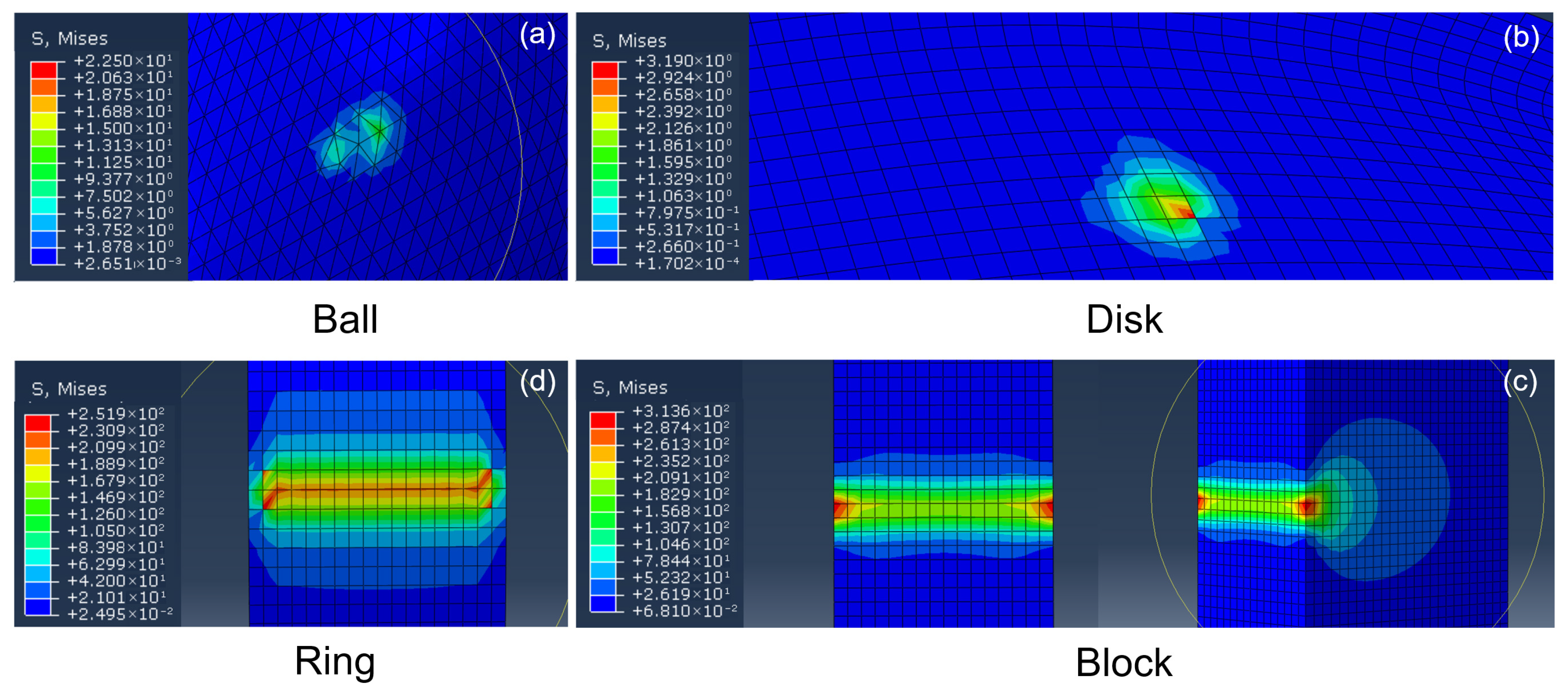

Figure 9 shows the von Mises stress distributions on the surfaces of the ball, disk, ring, and block obtained from the FEM analysis under the corresponding experimental loading conditions.

Figure 9.

von Mises stress (MPa) distributions on the surfaces of the ball, disk, ring, and block obtained from FEM simulations under the experimental loading conditions: (a) ball surface, (b) disk surface, (c) block surface, and (d) block surface and subsurface stress distributions. For the block, stress distributions are shown from two viewing orientations to highlight the anisotropy and non-uniformity of the stress field along the contact length and sliding directions under finite line-contact conditions.

For the point-contact configuration, the stress fields on the ball and disk surfaces (Figure 9a,b) are highly localized but not perfectly axisymmetric due to the presence of sliding. The maximum von Mises stress is shifted from the geometric center of the contact zone toward the leading edge along the sliding direction, where the ball first engages the disk. The stress decays rapidly away from the contact region. This stress distribution is consistent with the experimentally observed uniform and mild wear morphology on the disk surface.

For the line-contact configuration, the block surface (Figure 9c) exhibits a clear stress amplification near the free edge of the finite line contact. Compared with the central contact region, the von Mises stress increases sharply at the edge, indicating a pronounced free-edge effect induced by the geometric discontinuity and asymmetric boundary constraint [26]. This localized stress amplification corresponds to the severe edge-localized wear, surface tearing, and debris accumulation observed on the block surface in the experiments.

In contrast, the ring surface (Figure 9d) exhibits a continuous band-shaped high-stress region extending along the contact length. The stress level along the central portion of the contact is relatively uniform, indicating a stable load transmission condition. This stress distribution is consistent with the smooth and homogeneous wear morphology and the continuous Zn/P-rich tribofilm observed on the ring surface.

Although the maximum Hertzian contact stress was strictly matched between the point- and line-contact configurations, the FEM reveals that the resulting stress distributions in the surface and shallow subsurface regions of the contact differ substantially due to contact geometry. In particular, the line-contact configuration exhibits pronounced stress concentrations near the free edges of the contact, which are not captured by the nominal Hertzian contact stress alone. While the overall difference in stress distribution between point and line contacts is well known, the finite element analysis in this study serves to visualize these differences and to relate the local stress fields to the experimentally observed wear locations and morphologies. These results provide a mechanistic framework for interpreting why identical Hertzian contact stress does not lead to equivalent wear behavior for different contact geometries.

While the FEM results reveal pronounced stress concentrations on the block surface due to free-edge effects, localized peak stress alone may not fully account for the observed differences in overall wear severity. Wear is influenced by multiple interacting factors, including stress distribution, sliding history, temperature, and shear, and is therefore a cumulative and path-dependent process. However, the relative contributions of these factors cannot be determined based on the present results and will be the focus of future investigations.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that matching the maximum Hertzian contact stress alone is insufficient to ensure comparable wear behavior between point- and line-contact tribological test configurations. Under identical maximum Hertzian stress, material pairing, and oil-lubricated conditions, the line-contact (block-on-ring) configuration exhibited a lower coefficient of friction (approximately 28% lower) but a wear rate approximately two orders of magnitude higher than the point-contact (ball-on-disk) configuration.

These differences primarily originated from contact-geometry-dependent frictional energy dissipation and wear localization, which cannot be captured by a single nominal stress parameter. In the line-contact configuration, the higher normal load required to achieve the same Hertzian stress leads to a greater local temperature rise, while the concurrent enrichment of Zn–P-containing tribofilms reflects stress- and temperature-activated tribochemical responses under severe contact conditions rather than improved wear protection.

Overall, the results highlight the critical role of contact geometry in governing friction, wear, temperature evolution, and tribofilm behavior, and underscore the limitations of directly comparing wear data obtained from different standardized test methods, such as ASTM G99 and ASTM G77, based solely on nominal contact stress.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/lubricants14020074/s1, Video S1: ball-on-disk wear simulation; Video S2: block-on-ring wear simulation; Video S3: ball and disk FEM simulation; Video S4: block and ring FEM simulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and A.M.; methodology, J.C.; software, J.C.; validation, J.C. and A.M.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, J.C.; resources, A.M.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and A.M.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data used for this manuscript is shared in the text and figures. The raw data files generated from the study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Imaging and Microscopy Facility (IMF) and the Stem Cell Instrumentation Foundry (SCIF) at UC Merced for providing instrumentation support. The authors also thank Samuel Leventini for helpful discussions and insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stachowiak, G.W. Wear: Materials, Mechanisms and Practice; Wiley: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, K. Classification of wear mechanisms/models. In Wear–Materials, Mechanisms and Practice; Wiley: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Anand, K.A.; Kumar, V. Wear prevention & control as a preventive maintenance strategy. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 66, 3949–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullayev, H.; Huseynzade, E.; Sable, H. A Comprehensive Review of Wear Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies for Tribological Systems. Tribol. Ind. 2025, 47, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Xu, J.; Ma, L.; Jin, Z.; Prakash, B.; Ma, T.; Wang, W. A review of advances in tribology in 2020–2021. Friction 2022, 10, 1443–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Z. Tribology and development of wear theory: Review and discussion. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev. 2011, 3, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM G99-17; Standard Test Method for Wear Testing with a Pin-on-Disk Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM G77-17; Standard Test Method for Ranking Resistance of Materials to Sliding Wear Using Block-on-Ring Wear Test. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Williams, J.A. Engineering Tribology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.L. Contact Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, A. Introduction to Tribology for Engineers. 2024. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Tribology-Engineers-Ashlie-Martini/dp/B0B92HRMYV/# (accessed on 2 February 2026).

- Saikko, V.; Ahlroos, T. Wear simulation of UHMWPE for total hip replacement with a multidirectional motion pin-on-disk device: Effects of counterface material, contact area, and lubricant. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Off. J. Soc. Biomater. Jpn. Soc. Biomater. 2000, 49, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baş, H.; Özen, O.; Beşirbeyoğlu, M.A. Tribological properties of MoS2 and CaF2 particles as grease additives on the performance of block-on-ring surface contact. Tribol. Int. 2022, 168, 107433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, D.E.; Allmaier, H.; Priebsch, H.; Reich, F.; Witt, M.; Skiadas, A.; Knaus, O. Edge loading and running-in wear in dynamically loaded journal bearings. Tribol. Int. 2015, 92, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlus, P.; Galda, L.; Dzierwa, A.; Koszela, W. Abrasive wear resistance of textured steel rings. Wear 2009, 267, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczewski, R.; Piekoszewski, W.; Szczerek, M.; Wiśniewski, M. The influence of contact geometry on friction and wear characteristics. Tribotest 2000, 6, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventini, S.; Martini, A. Effect of Contact Geometry on MoS2-based Dry Film Lubricants. Res. Sq. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinedo, B.; Mendoza, G.; López-Ortega, A.; Zubizarreta, C.; Mendizabal, L.; Fraile, S.; Ionescu, L. Tribological investigation on WC/C coatings applied on bearings subjected to fretting wear. Tribol. Lett. 2024, 72, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, B.F.; El-Tayeb, N.S. On tribo-test machine integrating pin-on-disc and block-on-ring. Tribol. Online 2007, 2, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Buslovich, D.G.; Panin, S.V.; Kornienko, L.A.; Dobretsov, P.V.; Kolobov, Y.M. Tribological characteristics of fibrous polyphthalamide-based composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; Bader, N.; Venner, C.H.; Poll, G. Scale and contact geometry effects on friction in thermal EHL: Twin-disc versus ball-on-disc. Tribol. Int. 2021, 154, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Khonsari, M.M. On the thermodynamics of friction and wear―A review. Entropy 2010, 12, 1021–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveevsky, R. The critical temperature of oil with point and line contact machines. J. Basic Eng. 1965, 87, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plint, M.; Alliston-Greiner, A. The energy pulse: A new wear criterion and its relevance to wear in gear teeth and automotive engine valve trains. Lubr. Sci. 1996, 8, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigney, D. Comments on the sliding wear of metals. Tribol. Int. 1997, 30, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risdon, T.J.; Barnhurst, R.J.; Mihaichuk, W.M. Comparative wear rate evaluation of zinc aluminum (ZA) and bronze alloys through block on ring testing and field applications. SAE Trans. 1986, 95, 400–405. [Google Scholar]

- Extreme Coatings. Adhesive Wear Test (ASTM G77): Test Results. Available online: https://extremecoatings.net/technical-resources/test-results/adhesive-wear-test-astm-g77/ (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Johns-Rahnejat, P.M.; Dolatabadi, N.; Rahnejat, H. Elastic and Elastoplastic Contact Mechanics of Concentrated Coated Contacts. Lubricants 2024, 12, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spikes, H. The history and mechanisms of ZDDP. Tribol. Lett. 2004, 17, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spikes, H. Mechanisms of ZDDP—An update. Tribol. Lett. 2025, 73, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.