Abstract

In the era of modern technology, tribo coupling components require efficient lubrication to ensure optimal performance, and to avoid significant material loss throughout the entire duty cycle. Solid lubricants, when reinforced with optimal contents, have shown the ability to improve the tribological performance and sustain the lubricious behavior over extended periods. The goal of this study is to improve the reliability and lifetime of tribo components used in a variety of industrial applications. The investigation explores the lubrication mechanisms, and optimizes the tribological behavior of the Ni-based alloy coating impregnated with molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) and varying contents of silver (Ag). Specifically, four compositions containing 7 wt.% MoS2 with different contents of Ag, i.e., 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt.%, were developed via the HVOF route and tested from room temperature (RT) to 800 °C. The optimal composition was determined using a parametric experimental optimization approach based on friction and wear minimization. In particular, the coating with 15 wt.% Ag showed the least friction and wear across all tested temperatures. The coating material having 15 wt.% Ag along with 7 wt.% MoS2 attained a COF of 0.22 and wear rate of 5.3 × 10−6 mm3/Nm at 800 °C. The optimal content of Ag (15 wt.%) in the coating (NC15) decreased the wear rate by approximately 27% compared to the 20 wt.% Ag variant (NC20) at 800 °C. Overall friction and wear of the derived coatings decreased at 800 °C, with a minor increase at 400 °C. The apparent behavior demonstrated the complex interplay between coating ingredients and testing temperatures. The favorable tribo-chemical reactions and efficient boundary lubrication mechanisms worked together to reduce friction and wear.

1. Introduction

In the era of advanced technology, industrial tribo parts such as gas and steam turbines, aerospace engine hot-section parts, automotive turbochargers, and oil- and gas-drilling tools, where components operate between 700 and 900 °C are subjected to harsh operating conditions, would require a self-lubricant [1]. There is always a possibility that the underlying material will oxidize at that temperature rise, which could result in wear and an unfavorable friction coefficient. In real practical applications, Ni-Al coatings indeed play a crucial role in modern industry, especially in tribo elements where extreme conditions like high temperatures, mechanical stresses, and corrosive environments are encountered. Some specific advantages of Ni–Al alloys that make them highly suitable for such applications include a high melting point, low density, exceptional resistance to corrosion, oxidation, and compatibility with surface treatments [2]. However, brittleness at RT restricts their potential tribological applications [3,4,5]. A self-lubricating coating material over the underlying material with an appropriate content of solid lubricants can be a viable solution for the desired tribological properties, which would reduce wear and the friction coefficient and hence increase the component service life, translating to lower costs and higher system reliability—all crucial for next-generation tribological applications. Solid lubricants are useful in a variety of harsh environmental operating conditions, including dusty and lint-filled ones, without interfering with the binary system. In a temperature range from RT to 800 °C, traditional liquid and semi-solid lubricants face significant challenges, making solid lubricants the preferred choice for effective performance due to their intrinsic properties [6,7]. These lubricants are available in various forms of materials and each material has unique characteristics. These materials can be broadly divided into four categories: soft metals like gold and silver, polymers like teflon, 2D layered materials like h-BN, MoS2, graphite and carbon nano tubes, etc. [7,8,9]. MoS2 is widely recognized for its lubricating properties at room temperature [10]. Unlike MoS2, h-BN excels in high-temperature applications [11]. However, h-BN’s non-wettability and low sinterability limit its anti-wear applications [12]. Silver as a solid lubricant offers unique advantages, particularly in applications where compatibility with metal matrices is crucial. The exceptional thermal conductivity of silver indeed plays an effective role as a solid lubricant, particularly in reducing wear rates by efficiently dissipating excess frictional heat at the interface of sliding surfaces [13,14]. Single-solid lubricants are reported to be incapable of providing sufficient lubrication in a broad range of temperatures [15]. Achieving effective lubrication across a broad temperature range, from RT to as high as 800 °C, often requires a strategic approach that combines the capabilities of different lubricants optimized for specific temperature regimes [16]. In an investigation [17], the wear resistance of HVOF-sprayed NiMoAl-Cr3C2-Ag coatings was compared to plasma-sprayed coatings, and HVOF-sprayed coatings have shown better hardness, adhesion property and superior wear resistance. In a similar vein, Davis et al. [18] compared the wear resistance of NiMoAl-Cr2AlC composite coatings deposited using atmospheric plasma spray (APS) and HVOF methods, and found superior wear resistance of HVOF-deposited coatings. This was credited to the relatively dense microstructure of the coatings produced by HVOF. Yulong et al. [19] also strengthened the investigation by enlightening the salient features of HVOF-sprayed coatings. HVOF offers several advantages over other thermal spraying techniques. These include better binding strength, reduced substrate damage, controlled deposition and improved coating properties [19]. Tribologists are trying to capitalize the synergistic interaction of solid lubricants, which may stimulate the requisite lubricious phases required for reduced friction and wear. Earlier research also indicated that the mix of Ag-Mo solid lubricants has delivered exceptional lubricity in the working regime of different temperatures [20].

After the exhaustive literature review it is apparent that the coatings developed by the HVOF route have widespread industrial applications. Moreover, enhanced wear resistance can be attained by properly tuning the wt.% of solid lubricants in a Ni-based matrix. The selection of the coating material for a particular application depends on the set of operating conditions. It is also evident that only few investigations have reported the behavior of HVOF-sprayed coatings in a broad range of temperatures containing both Ag and MoS2 in a Ni-based matrix under a certain load and speed. The tribological performance of a material depends heavily on specific testing conditions, which include an applied load, sliding speed, counter face material, temperature, deposition method, and the test protocol used. Due to the above mentioned factors, which directly influence the tribo performance of a material, results from one study may not be directly applied to other situations. Moreover, as tribology is a rapidly evolving field, new research continues to enhance the understanding of the coating material (Ni-Al-MoS2-Ag) under the varying thermal exposure conditions. This research assesses the tribo performance of Ni-based alloy coatings containing Ag and MoS2 over a broad temperature range (RT-800 °C). Consequently, four different compositionally tailored Ni-based self-lubricating coatings were developed by the HVOF route, varying the concentration of Ag, i.e., 5, 10, 15 and 20 wt.% while maintaining a fixed concentration of MoS2 (7 wt.%). The fixed concentration of MoS2 (7 wt.%) is selected on the basis of prior experiments [4,15]. The study focuses on determining the optimal amount of solid lubricant (Ag) in conjunction with a fixed concentration of MoS2 (7 wt.%), and investigates the possible synergistic effects between these solid lubricants. The wear mechanisms were also discussed to understand the wear nature at different operating conditions.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Raw Materials and Coating Fabrication

The research work involves the HVOF method for the fabrication of formulated coatings. The feedstock materials such as MoS2, Ni, Al, and Ag (99% pure), were purchased from Loba Chemie, Varanasi, India. The particle size distributions of the feedstock powders were supplied by the manufacturer and confirmed prior to spraying. Ni powder exhibited a particle size range of 35–50 μm, Al powder ranged from 17 to 45 μm, Ag powder from 16 to 50 μm, and MoS2 powder from 20 to 50 μm. Inconel 718 was selected as a substrate material in the current experiment of a square size (45 mm × 45 mm), and a thickness of 6 mm. They were composed of Ni (52.78%), Fe (16.82%), Cr (16.48%), Nb (4.03%), and Mo (4.23%). The proper designation and composition of the coatings are displayed in Table 1. The homogeneous mixing of participating powders is crucial, which promotes interaction between different particles, leading to the formation of a coherent and well-bonded coating. A ball mill jar was used for mixing (4 h), filled with the calculated amounts of powders along with grinding balls and a ball-to-powder weight ratio (10:1) was maintained during the course of the process. During ball milling, zirconia balls were used to facilitate the ball milling (RETSCH, planetary ball mill, Haan, Germany) process. The ball milling was set up at a speed of 220 rpm to accomplish uniform mixing. The substrate material underwent initial cleaning through sand blasting prior to powder spraying. The corundum grits, ranging in size (620–780 µm), used in sand blasting had a surface roughness Ra = 12.12 µm. Additional cleaning was carried out through the ultrasonic cleaner (WENSARWUC-9L, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India) in the acetone. To increase the metallurgical bonding between the substrate and coating, NiCr was chosen owing to its ability to produce better adhesion between the coating and the substrate and also resistant to wear. A layer of NiCr (Metco 43VF-NS, Oerlikon Metco, Pfäffikon (Schwyz), Switzerland) was applied onto the substrate before the actual coating material deposition under the parameters listed in Table 2. After the spraying of NiCr, four distinct coatings of desired compositions, as given in Table 1, were developed over the square substrate plates using a K2 HVOF system (GTV mbH, Luckenbach, Germany), under the restrictions as mentioned in Table 2. The spraying parameters for the HVOF system were determined based on established guidelines in the literature [21,22] and are detailed in Table 2. All spraying parameters were kept constant for all coating compositions to ensure that observed differences in microstructure and tribological behavior were solely attributed to variations in Ag content. The microstructural view of the developed coatings was examined by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, FEI Quanta 200 FEG, Thermo Fisher Scientific (FEI Company), Hillsboro, OR, USA) inbuilt with an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX). The phase compositions of the developed coatings were observed by utilizing X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Philips X’Pert Pro PANalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands, Cu Kα, λ = 0.154 nm) from 2 θ varying 20° to 90° at 40 kV, 40 mA with a 2θ scanning rate of 0.02°/s. The micro-hardness of the derived coatings was estimated by an HX-1000TM Vickers hardness tester(Shanghai Taiming Optical Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Each test was conducted at a load of 300 g with a dwell time of 12 s. Across the polished cross-section of the coating, a minimum of eleven indentations were gauged. The average hardness value from these indentations was calculated and reported in the study. The porosity (area %) of the developed coatings was determined by using Image J software (version 1.54p). To ensure consistency in the results, at least five images were captured from distinct regions of the polished cross-section, and the mean porosity value was calculated.

Table 1.

Designation, composition, and wt.% of powders.

Table 2.

Parameters for bond coat and designated coatings through HVOF spraying.

2.2. Tribo Testing

The tribometer (DUCOM, Bengaluru, India) was used to assess the tribological behavior of coated specimens under a “ball on disc” configuration. An alumina ball (6.2 mm diameter) was used as the counterpart in the current study. The initial surface roughness of the as-deposited coatings ranged from 10 to 12 µm. The coated samples were subjected to mechanical polishing via silicon carbide emery paper (240 to 2000 grits) followed by diamond paste polishing on a velvet cloth to attain a roughness of 0.7 µm. Friction tests were carried out at 5 N under the sliding speed of 0.7 m/s. The wear track diameter was consistently kept at 30 mm for the sliding distance of 1120 m. The tribo tests were carried out using a high-temperature tribometer, which has the facility of an induction heating system.

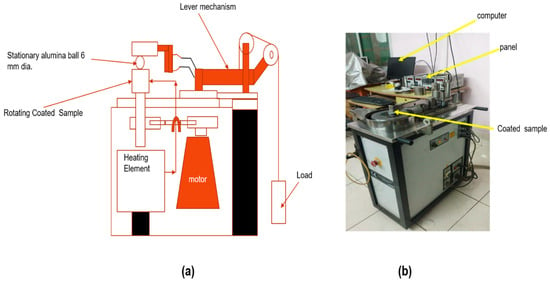

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the high-temperature tribometer and a photo of the high-temperature tribometer. Figure 1a depicts the schematic diagram of the tribometer. Figure 1b shows the coated specimen, which was heated continuously using an induction heater from the bottom at a controlled heating rate of 10 °C min−1 up to the final set temperature in the tribometer panel. After attaining the target temperature, a soak (dwell) time of 15 min was maintained prior to sliding to ensure thermal stabilization and uniform temperature across the coated specimen. All tests were conducted in laboratory air; the ambient relative humidity was maintained at 55 ± 5%, corresponding to an oxygen partial pressure of approximately 0.21 atm. The test temperature was observed using a K-type thermocouple embedded ~1 mm below in the disc; the reported temperature corresponds to the steady-state temperature value recorded immediately before sliding and continuously during the test. Once the set temperature was achieved, rotation was stopped and the temperature was allowed to stabilize. Wear debris was not periodically removed during the test, thus allowing the evolution of tribo-oxide layers under realistic high-temperature sliding conditions. Initially, there was no contact between the coated specimen and counter face ball, which were mounted on the jaw plate and lever arm, respectively. Subsequently, the desired normal load was applied to the lever arm, which brings the alumina ball into contact with the coated surface. During elevated temperature testing, the coated specimen temperature was maintained within ±5 °C. The real-time friction data was collected using a computer interface connected to the tribometer. All coating compositions as listed in Table 1 were produced in independent batches and each composition at each temperature was tested at least three times. The coefficient of friction for each test was calculated by averaging the recorded data over the entire sliding period. The current study has provided average results for each composition under the same testing conditions. Wear track morphology was analyzed using a non-contact optical profiler (Wyko NT 8000, Veeco Instruments Inc., Plainview, NY, USA). The cross-section profiles of the worn tracks were obtained to measure wear track depth. The estimation of the wear rate was carried out by extracting nearly 30 cross-sections from the wear track at different locations. The worn area was evaluated by combining the generated wear profiles above and below a selected reference line from the unworn surface. The volume loss of the participating coatings were calculated by multiplying the cross-sectional area to the circumference generated by counter body. The rate of wear of the formulated coatings were computed by , , and An SEM was used to examine the morphology of the wear tracks. XRD (Smart Lab, Rigaku, Germany) was used to evaluate different phases developed along the wear path via a “2D” D/MAX RAPID II-CMF detector inbuilt in micro area diffraction. Raman spectroscopy (Raman-HR-TEC, StellarNet, Inc., Tampa, FL, USA) was utilized to trace developed phases on both coated specimens and the counter face using a 785 nm laser wavelength. The current investigation used a parametric experimental optimization approach. The silver (Ag) content was selected as the sole design variable (5, 10, 15, and 20 wt.%), while the MoS2 content (7 wt.%), HVOF spray parameters, load (5 N), sliding speed (0.7 m/s), counter face material, and environment were kept constant. The optimization criteria were defined as (i) minimum average coefficient of friction and (ii) minimum wear rate over the entire temperature range from room temperature to 800 °C. The formulated coating composition satisfying both criteria simultaneously was designated as the optimal composition.

Figure 1.

Setup used for the high-temperature tribo testing of coated samples (a) Schematic diagram of high-temperature tribometer and (b) high-temperature tribometer.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Coatings

3.1.1. Hardness of the As-Deposited Coatings

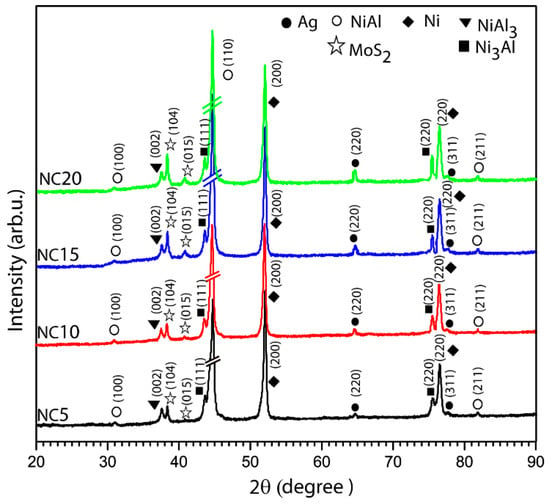

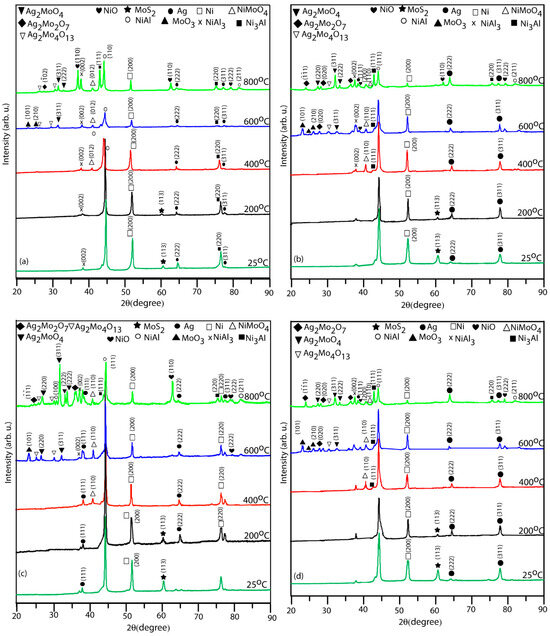

The hardness of the participating coatings has been observed to follow a decreasing trend. The hardness values (mean value) of the participating coatings for NC5, NC10, NC15, and NC20 are observed as 425.67 ± 5 HV0.3, 402.45 ± 5 HV0.3, 369.76 ± 4 HV0.3 and 330.21 ± 4 HV0.3, respectively. There is a declining trend in hardness with an increasing Ag content in the coatings. Silver (Ag) could not react with the participating solid lubricant (MoS2) and other coating constituents (Ni, Al) during the formulation (sprayings) of the coatings, as can be seen in XRD patterns shown in Figure 2. Therefore, Ag could exist in the coatings as a simple substance or as an element. Increasing the Ag content leads to lower overall hardness because Ag is significantly softer and the Vickers hardness of the pure Ag is only 2.7 GPa [23], which led to a significant decrease in the micro-hardness of the fabricated coatings.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of the as-deposited coatings, containing different Ag and MoS2 contents, highlighting the presence of solid lubricants.

3.1.2. Microstructural Study of the As-Deposited Coatings

Figure 2 shows the XRD patterns of fabricated, coated specimens, namely NC5, NC10, NC15 and NC20. The intermetallic phases (NiAl, NiAl3 and Ni3Al) could be seen in the patterns and indexed properly with a suitable JCPDS data file. The possible decomposition or oxidation of MoS2 during the HVOF spraying process was assessed through XRD analysis of the as-deposited coatings. As shown in Figure 2, mixed solid lubricants (Ag and MoS2) in the matrix were evident in the pattern, while no significant peaks related to MoO3 or other molybdenum oxides were observed in the as-sprayed coating samples. The nonappearance of a molybdenum oxide peak indicated that MoS2 largely retained its structural integrity during deposition. The relatively short dwell time of particles in the flame, combined with the high particle velocity and rapid cooling upon impact, limited extensive oxidation of MoS2 during spraying. It can be inferred from Figure 2 that the participating solid lubricants have been successfully incorporated in the matrix, showing no sign of the formation of oxide phases in coated specimens. It can be noticed, as listed in Figure 2, in the participating coatings (NC10, NC15 and NC20) the solid lubricant (MoS2) and formed intermetallic compound (Ni3Al) have more resolved and sharp peaks in comparison to the NC5 coating—an indication of increased crystallinity of these mentioned phases/compounds as the wt.% of Ag increased in the coated samples from 10 to 20 wt.%.

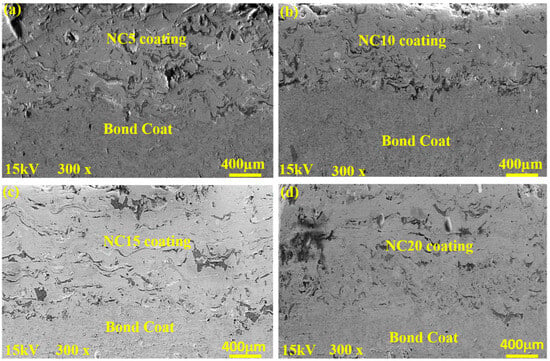

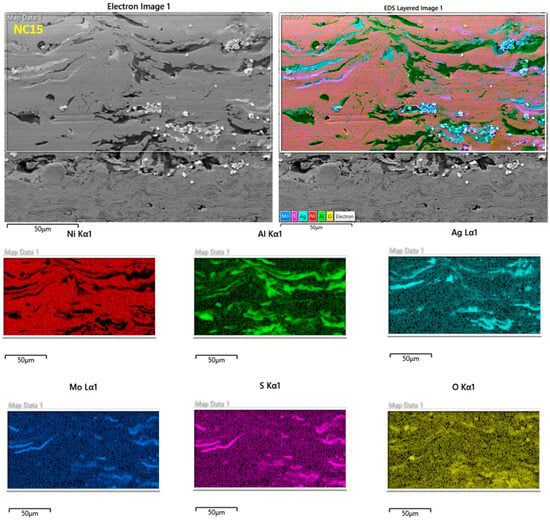

Figure 3 shows the cross-section morphology of the developed coated samples, namely NC5, NC10, NC15 and NC20, respectively. The micrographs clearly delineate the zones: bond coat, and coating. The Ag and MoS2 solid lubricants were distributed in the Ni-based matrix (Figure 3 and Figure 4). A relatively perfect connection could be observed at the interfaces of the solid lubricants. This can be attributed to the good adhesion property of Ni [1] and the appropriate spraying parameters which prevailed in the current study. The formulated coatings NC5, NC10, NC15 and NC20 have an average thickness of approximately 210 μm, 160 μm, 237 μm, and 220 μm, respectively. In the adopted method (HVOF), the high-pressure stream created by burning fuel and oxygen was used to treat the participating mix powder. In HVOF, temperatures during spraying were in the range of 2300–3000 °C and particle velocities up to 1350 m/s. These conditions are sufficient for the development of the desired coatings and their uniform dissemination onto the substrate, resulting in dense and compact coatings. As illustrated in Figure 3, the HVOF technique (i.e., a high-temperature flame and greater particle velocities) generated a dense, compact, and homogenous structure. The porosity of the derived coatings was determined by the Image J analyzer. The estimated porosities for coatings NC5, NC10, NC15, and NC20 were found to be 2.9 ± 0.2%, 2.5 ± 0.1%, 1.9 ± 0.2%, and 1.5 ± 0.3%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Polished SEM cross-section images of the derived coatings (a) NC5, (b) NC10, (c) BSE image of NC15, and (d) NC20.

Figure 4.

Elemental distribution maps of the cross-sections of formulated coating NC15.

3.2. Tribological Behavior

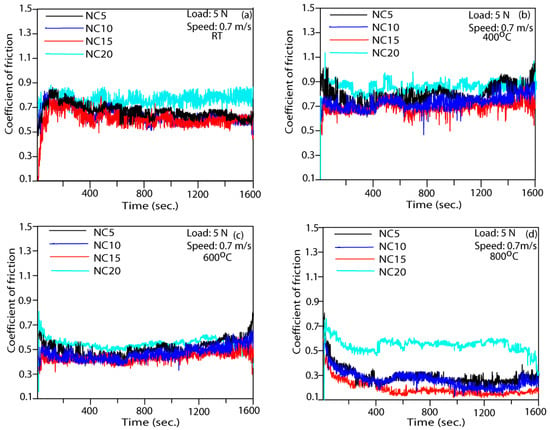

Figure 5 illustrates the amplitude fluctuations in the coefficient of friction (COF) over the period of testing for the different participating coatings (NC5, NC10, NC 15, and NC20) at different temperatures. The participating coatings do not show significant variation in the amplitude of the COF at the testing temperature (RT and 400 °C). At 600 °C and 800 °C, all the participating coatings show smooth variations with a low amplitude throughout the testing period, as evident in Figure 5c,d. It can be inferred from Figure 5a–d that coating NC15 showed the lowest COF throughout the testing period with small fluctuations in the COF. However, the coating NC20 has been detected to have a higher COF at all the testing temperatures with respect to other tested coatings.

Figure 5.

Variations in COF of formulated coatings at (a) RT; (b) 400 °C; (c) 600 °C; and (d) 800 °C.

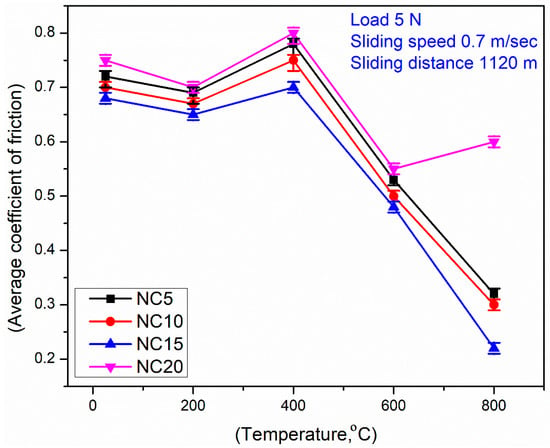

Figure 6 shows the variation in the average COF of the formulated coatings vs. testing temperatures. It is evident that all coatings show a declining trend in the COF in the regime RT to 200 °C as shown in Figure 6. At 400 °C, there is an increase in COF values. At 600 °C and 800 °C, there is a continuous lessening in the COF for all derived coatings except the NC20 coating. The said coating (NC20) steadily attains higher average COF values when compared against other coating formulations. Among the tested coatings, NC15 displayed the lowest average COF as given in Figure 6. The derived coating (NC15) shows favorable lubricity across the entire temperature range (RT-800 °C). This performance is associated with the synergistic effects of Ag and MoS2 and, highlighted NC15 as a promising coating material for applications requiring stable and low-friction performance especially under high-temperature conditions.

Figure 6.

Variations in average COF for coatings at different temperatures.

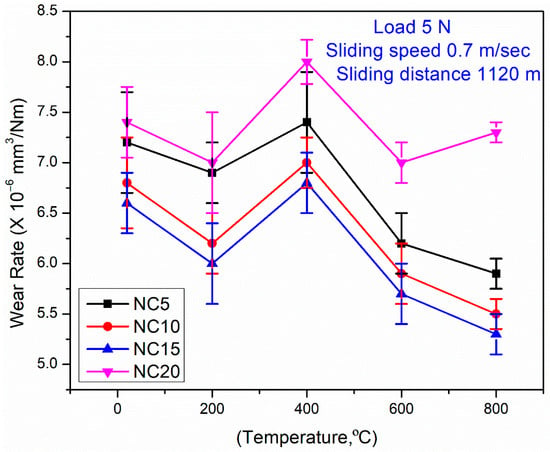

Figure 7 shows the wear rates of the coatings across a range of temperatures (RT-800 °C), and highlights the potential difference between the NC15 and NC20 coatings. All derived coatings have shown the highest coating material wear at 400 °C. The coating (NC20) consistently attained higher wear at all tested temperatures. However, the derived coating (NC15) demonstrated the higher wear resistance at each temperature. The mix of 15 wt.% Ag and 7 wt.% MoS2 in NC15 is noted as adequate to improve the coating’s lubricating properties and increased resistance towards wear. The formulated coating (NC15) shows improved wear resistance as compared to NC20, predominantly at elevated temperatures as shown in Figure 7. The positive synergy between Ag and MoS2 in NC15 played a decisive role in attaining the superior wear resistance. The optimal content of Ag and MoS2 in NC15 efficiently optimized lubrication conditions, and contributed to a greater reduction in wear under high-temperature conditions compared to NC20.

Figure 7.

Variations in wear rate for coatings at different temperatures.

3.3. Worn Surface Morphologies

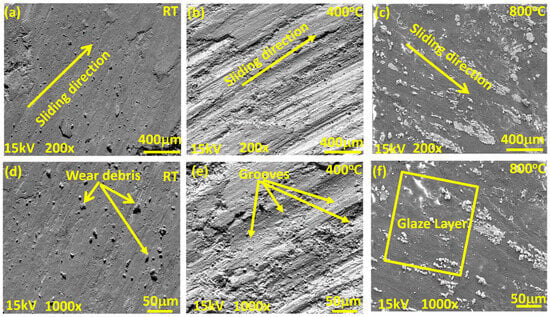

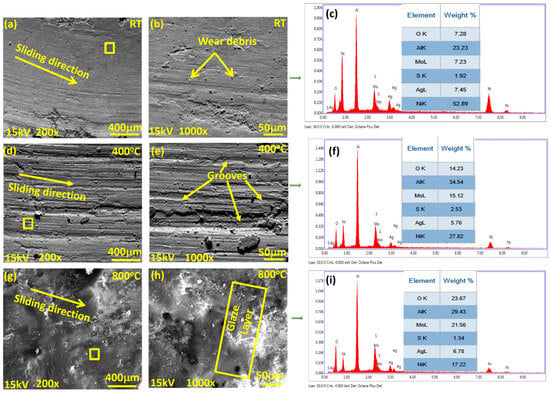

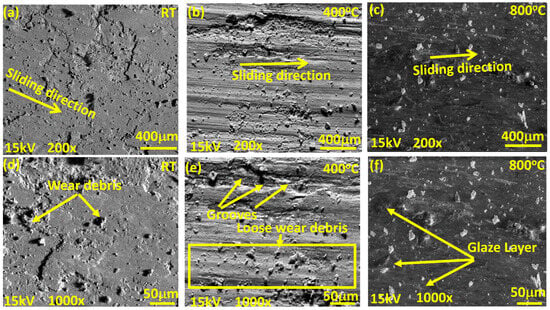

Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the worn surface morphology of the NC5, NC15 and NC20 coatings sliding under the load of 5 N against the alumina ball. The generated wear path at RT shows the creation of wear debris along the sliding direction for all the derived coatings. There is tribo layer formation observed, with varying degrees of coverage and compaction as indicated in Figure 8a,d, Figure 9a,b, and Figure 10a,d. However, at 400 °C, as shown in Figure 8b,e and Figure 9d,e, the wear path exhibits deep and shallow grooves over the wear track, whereas the other tested coating (NC20) shows the grooves, cluster of agglomerated wear debris, and delamination also observed in the direction of sliding for the coating NC20 (Figure 10b,e). The wear path at 800 °C (Figure 8c,f, Figure 9g,h and Figure 10c,f) shows the formation of a glaze layer. In Figure 9g,h, the wear track shows smooth plateaus at various junctions. These smooth plateaus and glaze layer is channelized across the entire worn surface, helped in reducing the COF and wear, as indicated in Figure 6 and Figure 7. The wear debris appears flattened over the surface for the coating NC20 at 800 °C. This glaze layer plus the presence of loose wear debris can potentially increase the COF and wear for the derived coating at 800 °C as shown in Figure 10c,f. Figure 9c,f,i display the EDS spectrum at different temperatures, taken over the wear path for the coating NC15. The square bracket over the worn surface of the coatings shows the area selected for EDS analysis. The EDS spectra at different temperatures show the existence of coating ingredients. Figure 9f,i also confirm the presence of coating materials, possibly with oxides at tested temperatures.

Figure 8.

SEM morphology of wear paths for coating (NC5) at lower and higher magnifications: (a–c) low magnification 200×; (d–f) corresponding high magnification 1000×; (a,d) RT; (b,e) 400 °C; (c,f) 800 °C.

Figure 9.

SEM morphology of wear paths for coating (NC15) at lower and higher magnifications: (a,d,g) low magnification 200×; (b,e,h) corresponding high magnification 1000×; (a,b) RT, (d,e) 400 °C, (g,h) 800 °C and their EDS spectra (c) RT, (f) 400 °C, (i) 800 °C.

Figure 10.

SEM morphology of wear paths for coating (NC20) at lower and higher magnifications: (a–c) low magnification 200×; (d–f) corresponding high magnification) 1000×; (a,d) RT; (b,e) 400 °C; (c,f) 800 °C.

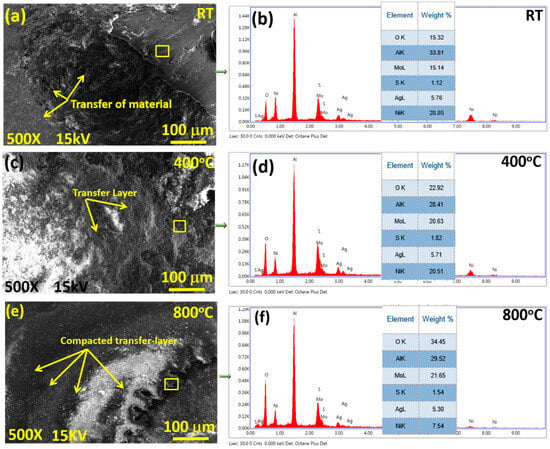

Figure 11 illustrates the morphology of an alumina ball after sliding against the NC15 coating at different temperatures. At RT, Figure 11a, the morphology of the alumina ball shows a transfer of the coating material. At 400 °C, Figure 11c, the morphology of the alumina ball exhibits a transfer layer that is loosely adhered. At 800 °C, Figure 11e, the morphology of the alumina ball shows the existence of smooth zones plus a compacted transfer layer. The existence of said features indicated that the transfer of coating materials is more efficient and results in a more uniform and adherent layer on the counter face. The EDS spectra, Figure 11b,d,f, reveal the presence of coating materials along with oxygen, suggesting some degree of oxidation or interaction with the environment during sliding at this temperature. At 800 °C, the transfer layer formed on the alumina ball is smoother and more compacted compared to lower temperatures (RT and 400 °C).

Figure 11.

SEM morphology of the transfer layer formed onto counter face sliding across NC15 at (a) RT, (c) 400 °C, and (e) 800 °C, and corresponding point EDS spectra acquired from the transfer film formed on the alumina counter face at (b) RT, (d) 400 °C, and (f) 800 °C.

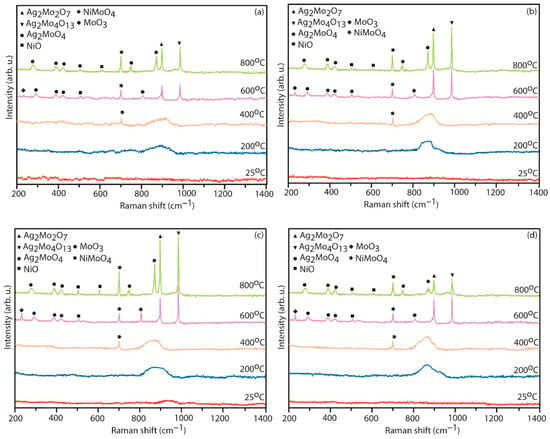

The XRD patterns and Raman spectra of the worn surfaces of various coatings (NC5, NC10, NC15, and NC20) tested at different temperatures against the alumina ball under the load of 5 N are depicted in Figure 12 and Figure 13. The XRD patterns of the worn surfaces, Figure 12a–d, exhibit the existence of coating materials over the wear track in the range of temperatures (RT-400 °C) and primarily exhibit phases such as Ni3Al, NiAl, and NiAl3, which are consistent with their compositions and matched with the JCPDS file. There is not much change in terms of new phase evolution compared to the as-sprayed coatings till 400 °C, except for the presence of NiMoO4 [24,25] at 400 °C, in all tested coatings. At elevated temperatures (600–800 °C), all the formulated coatings exhibit the creation of various oxides (MoO3, NiO, NiMoO4, Ag2Mo4O13, Ag2Mo2O7, and Ag2MoO4) which are clearly evident from the XRD patterns. At 800 °C, the XRD pattern for the formulated coating (NC15) exhibits the intensified peak of silver molybdate (Ag2MoO4). At 800 °C, the XRD patterns reveal the presence of additional new phases, specifically NiO and Ag2Mo2O7. In the Raman spectra, as shown in Figure 13, in the range of temperatures RT to 400 °C, a broad peak linked to the Ag2MoO4 phase is consistently detected over the wear path for all coatings, which is an indication of the amorphous form of silver molybdates. At 600 °C, new phases started to appear, including MoO3 [24,25,26], Ag2MoO4 [24,25] and Ag2Mo4O13 [24,25] as confirmed by Figure 13. At 800 °C, the wear path exhibits intensified peaks of several novel phases: Ag2Mo4O13, Ag2Mo2O7, Ag2MoO4, NiO [24] and NiMoO4 especially in the coating (NC15) as shown in Figure 13c. The intensified peaks of said compounds, along with NiO, indicated a significant extent of lubricious oxides over the worn surface. The formation of oxides at elevated temperatures suggests extensive tribo-chemical reactions, which triggered due to the constant sliding motion and thermal exposure. The existence of silver molybdates at elevated temperatures (600–800 °C) indicated a potential enhancement of lubricating conditions and thermal stability [27]. These phases may contribute to improved tribo performance by prevailing lubricating layers or reducing surface interaction.

Figure 12.

XRD patterns of worn track of derived coatings (a) NC5, (b) NC10, (c) NC15, and (d) NC20 at different temperatures.

Figure 13.

Raman spectrums of worn surface of derived coatings (a) NC5, (b) NC10, (c) NC15, and (d) NC20 at tested temperatures.

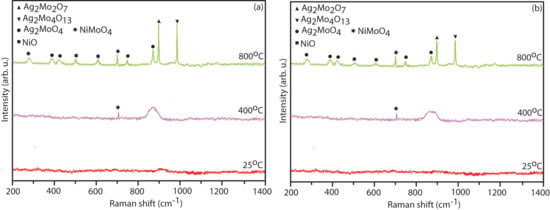

In the micro-Raman spectrum shown in Figure 14, which analyzes the transfer layer developed onto the counter face after sliding against the NC15 and NC20 coating, several key phases are observed at different temperatures. In Figure 14a, in the regime RT to 400 °C, the transfer layer on the counter face body primarily contains a broad peak corresponding to the Ag2MoO4 phase. At 800 °C, the transfer layer shows the presence of several phases: NiO, Ag2MoO4, Ag2Mo2O7, Ag2Mo4O13, and NiMoO4. The development of a transfer layer enriched with these intensified phases indicates that material transfer and chemical interactions played a substantial role in the tribological behavior of the coating NC15. Figure 14b shows relatively low intensified peaks, which give a hint of lubricious phases being transferred in a lower extent in the counter face slid against the said coating (NC20).

Figure 14.

Raman spectrum of the developed transfer layer onto counter face after wear test for (a) NC15, and (b) NC20 coating at different temperatures.

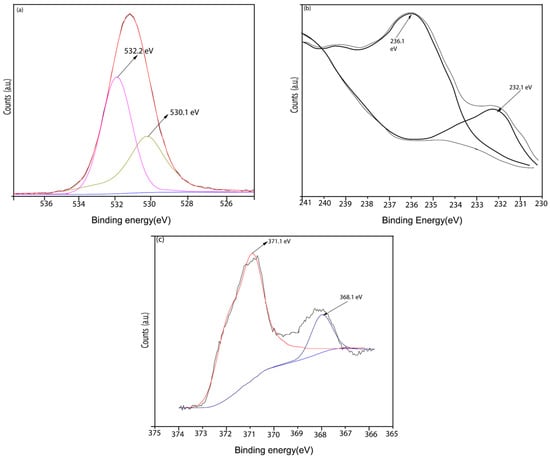

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) as shown in Figure 15 was employed to identify the chemical states of silver (Ag), molybdenum (Mo), and oxygen (O) on the worn surface of the NC15 composite coating after sliding at 800 °C. Figure 15a corresponds to the O1s spectrum and shows two distinct peaks at binding energies of approximately 530.1 eV and 532.2 eV, which can be attributed to different oxygen environments O1s (1) and O1s (2) within the Ag2MoO4 structure. These peaks likely correspond to lattice oxygen and surface-adsorbed oxygen, respectively, which can yield two Ag2MoO4 Gaussian peaks. Figure 15b depicts the Mo 3d spectrum in which the Mo 3d region exhibits two prominent peaks at 232.1 eV and 236.1 eV, corresponding to Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/2, respectively. These binding energies are consistent with the presence of Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/2 chemical states in the Ag2MoO4 phase, indicating Mo exists in a high oxidation state. Figure 15c shows the Ag 3d spectrum in which peaks located at 368.1 eV and 371.1 eV are assigned to Ag 3d5/2 and Ag 3d3/2, respectively. These values confirm the presence of Ag+ ions, which is also indicative of Ag2MoO4 formation. The XPS findings align with previously reported results [28] and are further supported by micro-Raman spectroscopy. The combination of XPS data with micro-Raman spectroscopy confirms that a silver molybdate (Ag2MoO4) tribo layer forms on the contact surface during sliding at elevated temperatures. Since Ag2MoO4 has a relatively low melting point (~528 °C) [29], it softens under high-temperature conditions, aiding in the formation of a lubricious and protective layer. The formed tribo layer plays a dual role: it reduces friction and wear by acting as a solid lubricant and protects the underlying material by minimizing direct contact between the sliding surfaces. The improved tribological performance at 800 °C by the NC15 coating could be attributed to the formation and transfer of this Ag2MoO4-based tribo layer to the wear path and counter face, respectively.

Figure 15.

XPS spectra and deconvoluted Gaussian peaks of the (a) O1s, (b) Mo3d and (c) Ag3d on the worn surface of NC15 composite coating sliding at 800 °C.

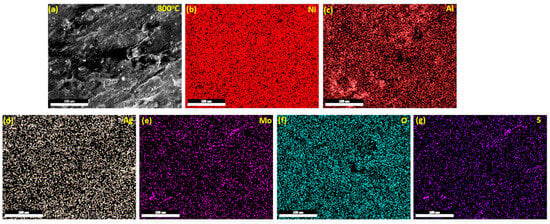

To identify the composition of the glaze film on the worn surface of the NC15 composite coating after sliding, elemental maps of the wear track were acquired at 800 °C. Figure 16a displays the worn surface morphology, while Figure 16b–g illustrate the elemental distributions of Ni, Al, Ag, Mo, O and S, respectively. These maps reveal a continuous oxide layer that blankets the wear track, coexisting with coating elements. The detected presence of Ni and O indicated the formation of a stable oxide (NiO)—a part of the protective glaze. Meanwhile, the simultaneous detection of Ag, Mo, and O strongly suggests the emergence of silver molybdate compounds. Silver molybdates (e.g., Ag2MoO4) are well-known, high-temperature solid lubricants, formed via in situ tribo-chemical reactions between Ag and Mo oxides. Under elevated temperatures (600–800 °C), silver molybdate phases develop readily and impart low shear strength, leading to reduced friction [27].

Figure 16.

Element mapping of the worn surface of composite coating (NC15) after sliding at 800 °C, showing the distribution of major coating and solid lubricant elements. (a) worn coating (b) Ni elemnet distribution over the worn path (c) Al element distribution over the worn path (d) Ag element distribution over the worn path (e) Mo element distribution over the worn path (f) O element distribution over the worn path (g) S element distribution ovre the worn path.

The continuous decline in micro-hardness of the formulated coatings (NC5, NC10, NC15, and NC20) as the Ag content increases can be attributed to the inherent softness of Ag that contributed to lower micro-hardness values in coatings. These findings align with research carried out by other investigators [30]. The average COF behavior of the derived coatings in the range of temperatures (RT to 200 °C) shows a decreasing trend, as indicated in Figure 6. This trend can be attributed to the following factors: Silver is known for its smooth and soft nature, which can facilitate easier shearing and sliding between mating bodies. This property contributes to reduced friction and thus a lower COF in the tested coatings. The average COF of the coatings increases notably at 400 °C. At 400 °C, the ability of silver to maintain its lubricating properties diminishes, leading to higher friction between the mating surfaces. This increase can be explained by the limitations of silver as a solid lubricant at the tested temperature (400 °C). In atmospheric air, the lamellar lubricating structure of MoS2 becomes unstable as the temperature increased to 400 °C due to the generation of oxides like MoO3. These oxides are hard, brittle, and not easy to shear, leading to increased friction. Even if at the prevailing temperature (400 °C), MoS2 does not fully decompose, some oxidation products can produce mixed Mo–O–S phases that alter shear characteristics in such a way that an increased friction coefficient is attained, effectively contributing to a “peak” in friction around intermediate temperatures. Earlier research findings also validate the point and suggest that silver may not effectively create optimal lubricating conditions at 400 °C [19,30]. At 400 °C, the worn surfaces showed the development of the NiMoO4 phase. This suggests that NiMoO4 begins to form on the surfaces of the materials being tested at this temperature. Despite the formation of NiMoO4 at 400 °C, it has been noted that NiMoO4 does not effectively lubricate the mating surfaces in the lower temperature range (RT-400 °C). Earlier findings also strengthen the point; the ineffectiveness of the NiMoO4 phase as a solid lubricant in delivering sufficient lubrication caused the uplift in the COF [31]. In Figure 8b,e, the worn surface of the NC5 coating, at 400 °C, shows the generation of shallow channels, abrasion, and minute-size free loose wear debris. Mechanically, the tribo layer over the worn surface at ~400 °C exhibits evidence of instability, including spallation, delamination, and abrasive wear modes. As tribo-oxides accumulate over the worn surface and the original low-shear tribofilm is consumed or replaced, frictional contacts tend to produce abrasive debris, cracks and flaking rather than a smooth shear-friendly interface. The existence of these features for the NC5 coating can lead to increased contact between mating surfaces. This increased contact can contribute to higher values of average COFs and wear. The catalytic action of sulfur over the worn surface promotes the creation of molybdates of silver. The XRD pattern, Figure 12a, shows the creation of several novel phases at elevated temperatures (600–800 °C). These phases include Ag2MoO4, Ag2Mo2O7, Ag2Mo4O13, MoO3, NiO, and NiMoO4. The declining trend of average COFs observed for the coatings can be attributed to the formation of these novel phases.

The coating (NC15) shows a decreasing trend in the COF across the temperature range RT to 200 °C. This decrease is owing to the soft nature of silver and ability to develop easily shearable junctions that are easier to shear off, thereby reducing friction. Interestingly, at 400 °C, as listed in Figure 6, the said coating (NC15) shows the highest average COF in comparison to other testing temperatures. It could be due to insufficient lubrication prevailed by the silver particles. In Figure 9d,e, the worn surface of the coating, at 400 °C, shows grooves and abrasion. The rise in the average COF at the said temperature is attributed to a lack of effective lubrication between the coating and the counter face. The counter face morphology, Figure 11c, shows loosely bound, uneven coating material on the counter face at 400 °C. This loosely adhered transfer layer and coating material could contribute to a higher COF and wear due to incomplete or ineffective lubrication between the counter face and the NC15 coating. At 800 °C, the worn surface shows a glaze layer, as depicted in Figure 9g,h. The manifestation of this smooth glaze layer avoids the paired bodies’ direct contact. As a result, a reduced COF and wear is observed at 800 °C compared to lower temperatures. At higher temperatures, such as 800 °C, the counter face morphology, Figure 11e, exhibits smooth regions and well-compacted transfer layers. This suggests that effective lubricants have been formed on the worn surface. The XRD patterns, Figure 12c, show the presence of phases, i.e., Ag2MoO4, Ag2Mo2O7, Ag2Mo4O13, MoO3, NiO, and NiMoO4. These phases act as effective lubricants that deliver efficient lubrication, particularly at elevated temperatures [19]. The Raman spectra, Figure 13c, also provide the signals of these lubricating phases, which enhance the tribo performance as the temperature increases. The Raman spectrum, as given in Figure 14a, indicated the signals of novel lubricating phases in the transfer layer onto the counter face. The mutual interaction of the lubricious phases present onto the counter face and those developed on the worn surface minimized the contact between mating bodies. These phases enabled the easily shearable junctions, and allows the mating bodies to slide over each other without making direct contact. This mechanism leads to a continuously decreasing trend in the average COF and wear for the derived coating. At elevated temperatures (600–800 °C), the more crystalline lubricating oxides (such as NiO, Ag2MoO4) increase significantly as depicted in Figure 12c and Figure 13c. The inter-diffusion of the elements over the whole volume beneath the track, oxidation by frictional heating plus testing temperature and the ideal content of Ag (15 wt.% Ag) and its synergistic interaction with MoS2 contributed to the reduced friction and wear as observed in the optimized NC15 coating. This synergy enhanced the effectiveness of the lubricating phases and promoted a smoother sliding interface, thus lowering friction and wear. During sliding under high-contact pressure, MoS2 sheets align along their basal plane on the traced wear path. This alignment occurs due to the shearing forces that promote the orientation of MoS2 layers. As per the calculation of the density function theory, MoS2 is a 2D material with weak Van der Waals forces between its layers [32]. This makes it susceptible to exfoliation, especially under mechanical stress like rubbing. The stress-induced shear forces can cause these layers to separate, which is beneficial for forming uniform tribo layers. The existence of a sharp band at 820 cm−1 in the Raman spectrum, as indicated in Figure 13c, corresponds to MoO3. This band is associated with the symmetric stretching of Mo–O–Mo bonds, which is a characteristic of MoO3. Due to environmental conditions (the existence of oxygen and moisture), along with a sufficient temperature increase, MoS2 undergoes oxidation. This oxidation process converts MoS2 into MoO3. The tribo-chemical reaction for this process is: MoS2 + 3.5 O2 → MoO3 + 2 SO2. The development of the MoO3 band at 820 cm−1 is a clear indication of the oxidation process. It indicates that MoS2 has been converted to MoO3, and the band reflects the symmetric stretching of terminal oxygen atoms in the MoO3 structure [33]. At the same time silver also oxidizes, leading to the creation of AgO, a thermodynamically unstable compound [34]. In the temperature range 83 to 134 °C, the formed AgO can decompose to Ag2O and oxygen as per the following chemical equation: 4 AgO → 2 Ag2O + O2 [35,36]. Although Ag2O is expected to develop, it could not be found in the Raman spectra owing to the continuous conversion of Ag2O into Ag2MoO4 as per the chemical route: Ag2O + MoO3 → Ag2MoO4 [37]. Silver (Ag) and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) work together to provide reliable lubrication across a broad temperature range: at lower temperatures, MoS2’s layered structure enables ultra-low friction, while Ag, due to its low shear strength, forms a soft, load-bearing tribofilm and dissipates heat due to high thermal conductivity. As temperatures exceed ~350 °C, Ag reacts with oxidized MoS2 products to form layered silver molybdate phases (e.g., Ag2MoO4, Ag2Mo2O7, and Ag2Mo4O13), which shear easily and sustain low friction, and at higher temperatures MoS2 oxidizes into MoO3 (lubricious oxide) and reacts with Ag2O to create a stable, adaptive tribo-chemical layer maintaining low wear and friction, even up to 800 °C. The optimal content of Ag (15 wt.%) with MoS2 produces more synergy and so stimulates the optimal content of lubricating oxides which is clearly evident in the XRD patterns and Raman spectra as shown in Figure 12c and Figure 13c, respectively. The formation of various oxides by the process discussed above causes the development of a dense layer over the worn surface which protects from further wear and also helps in the reduction in the COF. The designated coating NC15, which contains 15 wt.% of Ag, shows superior lubricious phases compared to NC10 at 800 °C. The reason behind the perceived behavior shown by the coating NC15 can be explained on the basis of the XRD and Raman spectra of the wear path. There is evidence of the intense peaks of NiO and Ag2MoO4 in the XRD and Raman spectra of the wear path of coating NC15 as shown in Figure 12c and Figure 13c, respectively. The formulated coating NC15 with 15 wt.% of Ag significantly reduces the COF and wear compared to NC10, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. At temperatures beyond 400 °C, the continuous lessening in the COF and wear is attributed to the existence of lubricious oxides such as MoO3 and NiO, as well as silver molybdates. The transformation sequence involves MoO3 oxidizing into Ag2Mo4O13 at 600 °C through the following chemical reaction: 2Ag + 4MoO3 + 1/2 O2 → Ag2Mo4O13. Due to the available silver (Ag) combining with Ag2Mo4O13 and O2 to form Ag2Mo2O7 via the chemical reaction 2Ag + Ag2Mo4O13 + 1/2 O2 → 2Ag2Mo2O7, further transformation of Ag2Mo2O7 to Ag2MoO4 at 800 °C occurs through the chemical reaction 2Ag + Ag2Mo2O7 + 1/2O2 → 2Ag2MoO4, as indicated earlier by other researchers [38]. The silver molybdate phases, Ag2MoO4 and Ag2Mo2O7, formed within the coating system are known for their layered crystal structures, which contribute to effective lubrication [27]. The silver molybdate (Ag2MoO4) exhibits weak O–Ag–O bonding, which makes it particularly beneficial for continuous lessening of the friction coefficient and wear [27]. The incorporation of 15 wt.% Ag in the NC15 coating composition facilitates the in situ formation of these lubricious molybdate phases, enhancing its high-temperature tribological performance. At increased temperatures (RT to 800 °C), there is an observable increase in crystallinity. This is supported by XRD patterns shown in Figure 12c, where more intense and sharper diffraction peaks appear at elevated temperatures. These changes suggest a temperature-induced recrystallization process, where higher thermal energy allows atoms to reorganize into more ordered crystalline structures. The presence of an optimal content of Ag plays a pivotal role in this transformation. The inclusion of an optimal content of Ag (15 wt.%) not only aids in the nucleation of silver molybdates but also stabilizes the growing crystals by lowering the activation energy for phase formation. This is evident from Figure 12c and Figure 13c, where the heightened intensity of specific peaks indicates an excess precipitation of crystalline silver molybdates. These precipitates contribute to the formation of a stable, compact crystalline layer at the contact surface. The interplay between increased temperature, an optimal content of Ag, and intense formation of molybdates fosters an ideal surface condition that resists wear and maintains low friction. Additionally, prior studies have linked this behavior to the emergence of a glaze layer—a smooth, crystalline tribofilm formed during sliding which serves as a protective interface and further reduces the COF and wear [39]. The solid lubricants, formed via in situ tribo-chemical reactions, provide a low-shear-strength tribofilm on the friction pair’s interface [40], especially at elevated temperatures. The tribo-chemically generated glaze layers can provide effective, wear-reducing protection only when the contact conditions support oxide sintering and stimulate the optimal content of lubricious oxides as indicated in Figure 12c and Figure 13c. Debris formation and compaction should proceed continuously, which will help in the generation of a uniform tribo layer over the wear path. The glaze remains crack-free and properly bonded under stress and temperature cycling, which further supports the minimization of the friction coefficient and wear. In summary, the synergistic interaction between temperature, the optimal Ag content, and silver molybdates formation governs the high-temperature performance of the NC15 coating. The enhanced crystallinity, driven by recrystallization and Ag-induced molybdates precipitation, results in a durable lubricating layer that effectively protects against friction and wear under thermal stress.

The formulated coating NC20 at RT, Figure 10a,d, has shown the cluster of wear debris and broken tribo layers over the formed wear path. At 400 °C, Figure 10b,e, it possesses deep parallel grooves and loose, channelized, scattered wear debris are observed in the wear track. These features increase the average COF and wear of the NC20 coating at the said temperature. High-temperature tribology is governed more by tribofilm chemistry and dynamic stability rather than by bulk hardness. Too much Ag dilutes the active contact chemistry and weakens the matrix, leading to unstable tribofilms, and higher wear/COF despite softer phases. Excess Ag simply dilutes the chemistry of the produced phases via tribo-chemical reactions that participate actively in creating the shear plane of low shear strength. The derived coating NC20 produced discontinuous re-deposition of loose debris, early delamination/spallation or overly soft tribofilms that are not shear-friendly. A soft matrix and high Ag content led to Ag-rich smearing instead of coherent tribofilm. Essentially, the contact zone becomes too soft and unstable, akin to a “grease” that cannot sustain shear loads. At 600 °C, the formation of Ag2MoO4 and NiO takes place. These phases reduced the average COF and wear of the derived coating at 600 °C. At 800 °C, Figure 10c,f, the evolution of a glaze layer due to high temperatures, presence of a loosely adhered transfer layer, and wear debris are evident over the worn surface. During wear, exfoliated MoO3 and hard Ni3Al fragments entered the contact interface, acting as abrasive third-body particles, significantly accelerating wear and raising the wear of the formulated coating. These factors lead to three-body abrasion, which raises the average COF and wear significantly at the testing temperature for NC20. The evidence of less intensified peaks, Figure 13d, indicated a lower extent of lubricious compounds over the wear path at 800 °C. The low intensified peaks of lubricious phases over the counter face transfer layer at elevated temperatures, shown in Figure 14b, are somehow not able to separate the mating bodies and cause local touching of the mating surface and leads to a higher COF and wear. The other point of view is that the softening of the derived coating and reduced hardness due to the incorporation of an excessive Ag content (20 wt.%) in the current investigation are identified as causes for this behavior. The formation of a glaze lubricating layer at only some specific spots plus loose wear debris further contributed to the three-body abrasion and increased values of the friction coefficient and wear attained for the derived coating at this temperature. Compared to its closest competitors, NC10 and NC20, the formulated coating NC15 exhibited a consistently lower coefficient of friction and wear rate at all tested temperatures. However, the derived coating NC10 suffered from insufficient formation of high-temperature lubricious oxides and NC20 showed excessive softening and three-body abrasion due to surplus Ag; NC15 provided an optimal balance between mechanical integrity and tribo-chemical lubrication.

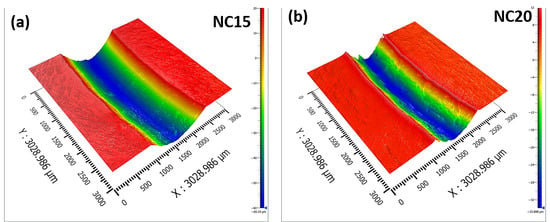

Figure 17 shows the 3D surface scanning profiles of the wear tracks for the NC15 and NC20 coatings at 5 N load and 0.3 m/s sliding speed. The 3D profile data clearly shows the differences in the widths and depths of the wear tracks for different participating coatings. The NC15 coating as shown in Figure 17a shows the shallowest and smoothest wear track: the groove is broad with gentle slopes, minimal depth variation, and the surface appears more uniform, with reduced asperity height. These observed features suggest the formation of a stable, load-bearing tribofilm or glaze layer. The wear mechanism changes from abrasive wear to oxidation-assisted mild wear. However, the NC20 coating, as shown in Figure 17b, exhibits a deep and narrow central groove and steep groove walls indicating severe plowing. The wear mechanism changes from abrasive wear to a limited formation of a protective tribofilm, and detached debris likely acted as third-body abrasives. With an increased content 20 wt.% of Ag in the formulated coating NC20, the hardness of the coating decreases due to over-softening, which causes tribofilm rupture and debris delamination. This mechanism leads to discontinuous glaze patches, higher roughness, persistent abrasive grooves, and friction coefficient instability. Thus, although Ag promotes lubrication, its excessive content in NC20 disrupts tribofilm integrity at high temperatures. At 800 °C, NC15 exhibits a pronounced reduction in wear track roughness (Ra ≈ 0.45–0.55 µm) and mean groove depth (dg≈ 0.6–0.9 µm) compared with NC20 (Ra ≈ 1.2–1.5 µm; dg ≈ 1.3–1.8 µm), indicating a transition from severe plowing to a smoothed, load-bearing tribofilm. The reduced COF fluctuation observed for NC15 at 800 °C, Figure 5d, correlates with the formation of a smooth tribological interface, indicating a stable shear plane within the glaze layer. In contrast, NC20 exhibits higher COF oscillations, consistent with the intermittent rupture and re-formation of an unstable tribofilm due to excessive Ag-rich debris.

Figure 17.

3D surface scanning profiles of the wear track for the coatings (a) NC15, (b) NC20 at 5 N load and 0.3 m/s sliding speed at 800 °C.

When the various formulated coatings are worn as the temperature increases (RT-800 °C), their surface morphologies change and exhibit different worn morphologies due to evolving dominant wear mechanisms and chemical transformations of the participating solid lubricants (Ag and MoS2), depending on the testing temperatures. At RT, the wear mechanisms in NC5 coatings involve a combination of abrasion with the existence of coating material debris as shown in Figure 8a,d; however, at 400 °C, abrasion, adhesion and plowing, as clearly evident in Figure 8b,e, are the dominating wear mechanisms. The SEM morphology at 400 °C suggests the inadequate lubrication and indication of abrasion due to the oxidation of MoS2 and Ag are not able to produce the favorable lubricants and hence different morphologies could be perceived at 400 °C. At higher temperatures, the formation of a glaze layer becomes predominant, forming silver molybdates-rich tribofilms that create smooth, continuous oxide glaze layers with minimal furrowing, markedly reducing direct abrasive contact and micro-cracking. For the NC15 coating, the wear mechanisms transition from a mix of abrasion and adhesion in the low-temperature range (RT-400 °C), as shown in Figure 9a,b,d,e, to tribo oxidation, and formation of glaze layers at higher temperatures. In contrast, the NC20 coating consistently shows delamination, a cluster of loose wear debris, and discontinuous tribo layer creation in low-temperature regimes, as shown in Figure 10a,b,d,e. At elevated temperatures, glaze layer formation with a loosely adhered transfer layer and wear debris formation are evident.

4. Conclusions

The current research work provides a comprehensive and in-depth evaluation of the tribological performance of HVOF-sprayed coatings impregnated with Ag and MoS2, considering the coefficient of friction, wear rate, wear mechanism evolution, and transfer film formation under the tested conditions. The salient points from the research are listed below with improved clarity.

- The in-depth evaluation refers to the combined assessment of friction behavior, wear performance, surface damage mechanisms, and tribo-chemical interactions. SEM and EDS investigations reveal the role of Ag and MoS2 in promoting the formation of a stable lubricious tribofilm, which effectively reduces direct asperity contact and suppresses severe adhesive and abrasive wear.

- Among the investigated Ag–MoS2 impregnation levels in the formulated coatings, the optimal combination in the NC15 coating, containing 15 wt.% Ag and 7 wt.% MoS2, exhibited the lowest coefficient of friction (0.22) and wear rate (5.3 × 10−6 mm3/Nm) at 800 °C. The term “optimal” is used here to denote the best-performing composition within the experimentally studied range, rather than the outcome of a formal optimization algorithm.

- Among the investigated compositions, the coating composition NC15 was identified as the optimal composition based on a parametric optimization criterion, i.e., simultaneous minimization of friction and wear over the temperature range RT–800 °C. In comparison to other coating formulations, NC15 delivered the best compromise between lubricious oxide formation and coating mechanical stability.

- At 800 °C, the NC15 coating demonstrated favorable lubricity, and outperformed other coating formulations with lower Ag contents (NC5, NC10) and other coatings which had 20 wt.% Ag (NC20). The optimal content (15 wt.%) of Ag and 7 wt.% MoS2 act synergistically in the NC15 coating, promoting the formation of a greater amount of lubricous oxides. The existence of lubricious oxides on coupling bodies contributed to a reduced friction coefficient and wear by preventing direct contact between mating bodies. The NC15 coating maintained its superior lubricity due to a greater extent of lubricious oxides, sustained tribo layer formation and transfer of novel lubricious phases even at 800 °C.

- The investigated Ni-based composite coatings containing Ag and MoS2 are intended for high-temperature sliding components operating under boundary or mixed lubrication conditions, such as hot-forming dies, high-temperature valves and seals, sliding bearings in furnaces, and gas turbine auxiliary components. The selected test temperature of 800 °C corresponds to the upper operating range encountered in hot-working and furnace-related components, where severe oxidation and adhesive wear dominate. The applied normal load (5 N) and sliding speed (0.7 m/s) were chosen to represent moderate contact stresses typical of these components during steady-state operation, enabling comparative evaluation of tribological performance and lubrication mechanisms. Accordingly, the present study aims to assess the suitability of Ag–MoS2-impregnated, Ni-based coatings for high-temperature, self-lubricating applications.

Author Contributions

Methodology, R.K.S.G., S.M., J.K.G., P.J., W.U.A. and K.H.; Validation, V.M.T. and S.A.; Formal analysis, D. and R.K.S.G.; Resources, M.A., S.M. and K.H.; Writing—original draft, S.A.; Writing—review & editing, J.K.G., P.J., S.A., W.U.A. and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sun, H.; Wan, S.; Yi, G.; Pham, S.T.; Collins, S.M.; Xin, B.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, W. Enhancing tribological performance of NiAl–Bi2O3–Cr2O3 composite coating via in-situ grown NiBi compound. Wear 2024, 538–539, 205189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Shrivastava, S. Brittle-to-ductile transition in NiAl single crystal. Acta Mater. 1998, 46, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Cheng, J.; Qiao, Z.; Yang, J. High temperature solid-lubricating materials: A review. Tribol. Int. 2019, 133, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noebe, R.D.; Bowman, R.R.; Cullers, C.L.; Raj, S.V. Flow and fracture behavior of NiAl in relation to the brittle-to ductile transition temperature. MRS Online Proc. Libr. 1990, 213, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S.S.; Pandey, K.K.; Sharma, S.; Kumari, S.; Mirche, K.K.; Kumar, D.; Pandey, S.M.; Keshri, A.K. Microstructural, mechanical and tribological behavior of nanodiamonds reinforced plasma sprayed nickel-aluminum coating. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 133, 109714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazirisereshk, M.R.; Martini, A.; Strubbe, D.A.; Baykara, M.Z. Solid lubrication with MoS2: A review. Lubricants 2019, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, A.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, L. 2D nano-materials beyond graphene: From synthesis to tribological studies. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 3353–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, T.W.; Prasad, S.V. Solid lubricants: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, M.; Berman, D.; Rota, A.; Jackson, R.L.; Rosenkranz, A. Layered 2D Nanomaterials to Tailor Friction and Wear in Machine Elements-A Review. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2101622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.K.S.; Rao, U.S.; Tyagi, R. Influence of Load on Friction and Wear Behavior of Ni-Based Self-Lubricating Coatings Deposited by Atmospheric Plasma Spray. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 7398–7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, K.P.; Mello, J.D.B.; Klein, A.N. Self-lubricating composites containing MoS2: A review. Tribol. Int. 2018, 120, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Wakabayashi, T.; Okada, K.; Wada, T.; Nishikawa, H. Boron nitride as a lubricant additive. Wear 1999, 205, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Guo, B.; Zhou, H.; Pu, Y.; Chen, J. Preparation and characterization of reactively sintered Ni3Al–hBN–Ag composite coating on Ni-based super alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 473, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Han, M.; Chen, W.; Lu, C.; Li, B.; Wang, W.; Jia, J. Microstructure and properties of VN/Ag composite films with various silver content. Vacuum 2017, 137, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.K.S.; Mishra, I.P.; Tripathi, V.M.; Mishra, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Jha, P.; Nautiyal, H. Synthesis and tribological characterization of cold-sprayed Ni-based composite coatings containing Ag, MoS2 and h-BN. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 325, 129652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.K.S.; Tripathi, V.M.; Singhania, S.; Mishra, S.; Jha, P.; Singh, A.K.; Gariya, N.; Shahab, S.; Nautiyal, H. Evaluation of Tribological Characteristics of Atmospheric Plasma Spray Deposited Ni- Based Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2024, 33, 1544–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J.; An, Y.; Yan, F. Microstructure and tribological property of HVOF-sprayed adaptive NiMoAl–Cr3C2–Ag composite coating from 20 °C to 800 °C. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 258, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Singh, S.; Chakradhar, R.P.S.; Srivastava, M. Tribo-mechanical properties of HVOF-sprayed NiMoAl-Cr2AlC composite coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2020, 29, 1763–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Chen, J.; Hou, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J.; Yan, F. Effect of silver content on tribological property and thermal stability of HVOF-sprayed nickel-based solid lubrication coatings. Tribol. Lett. 2015, 58, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; An, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhao, X.; Yan, F.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. Tribological properties of adaptive NiCrAlY-Ag-Mo coatings prepared by atmospheric plasma spraying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 235, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, K.; Niu, S.; Liu, M.; Dai, H.; Deng, C. Microstructure of HVOF-sprayed Ag-BaF2⋅CaF2-Cr3C2-NiCr coating and its tribological behavior in a wide temperature range (25 °C to 800 °C). Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.K.S.; Tripathi, V.M.; Gautam, J.K.; Mishra, S.; Nautiyal, H.; Jha, P. Tribological Behavior of High-velocity Oxygen Fuel-Sprayed Ni-Based Self-Lubricating Composite Coatings. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 7991–8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, J.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y. Effect of Ag Content on the Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Mo-12Si-8.5B Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 2961–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gao, Y.; Han, M.; Guo, H.; Wang, W.; Jia, J. Microstructure and tribological properties of NiCrAlY-Mo-Ag composite by vacuum hot-press sintering. Vacuum 2017, 143, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Jia, J. Tribological properties of adaptive Ni-based composites with addition of lubricious Ag2MoO4 at elevated temperatures. Tribol. Lett. 2012, 47, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Singh, S.; Srivastava, M. Influence of solid lubricants addition on the tribological properties of HVOF sprayed NiMoAl coating from 30 °C to 400 °C. Mater. Lett. 2020, 266, 127494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Jia, J.; Han, M.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, C. Microstructure, mechanical and tribological properties of plasma-sprayed NiCrAlY-Mo-Ag coatings from conventional and nanostructured powders. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 324 , 552–559. [Google Scholar]

- Suthanthiraraj, S.A.; Premchand, Y.D. Molecular Structural Analysis of 55 mol% CuI–45 mol% Ag2MoO4 Solid Electrolyte using XPS and Laser Raman Techniques. Ionics 2004, 10, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lan, H.; Huang, C.; Du, L.; Zhang, W. Formation mechanism of the lubrication film on the plasma sprayed NiCoCrAlY-Cr2O3-AgMo coating at high temperatures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 319, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J.; An, Y.; Yan, F. HVOF-sprayed adaptive low friction NiMoAl–Ag coating for tribological application from 20 °C to 800 °C. Tribol. Lett. 2014, 56, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petterson, M.; Calabrese, S.J.; Stupp, B.C. Lubrication with Naturally Occurring Double Oxide Films; Wear Sciences Inc.: Kerrville, TX, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mera, D.F.Z.; Broens, M.I.; Villarroel, R.; Gonzalez, R.E.; Hurtado, J.Y.A.; Wang, B.; Suarez, S.; Mücklich, F.; Valenzuela, P.; Gacitúa, W.; et al. Solid lubrication performance of sandwich Ti3C2Tx-MoS2 composite coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 640, 158295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windom, B.C.; Sawyer, W.G.; Hahn, D.W. A Raman spectroscopic study of MoS2 and MoO3: Applications to tribological systems. Tribol. Lett. 2011, 42, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallek, S.; West, W.A.; Larrick, B.F. Decomposition Kinetics of AgO Cathode Material by Thermogravimetry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1986, 133, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, G.; Tummavuori, J.; Lindström, B.; Enzell, C.R.; Swahn, C.-G. ESCA Studies of Ag, Ag2O and AgO. Acta Chem. Scand. 1973, 27, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissot, P.; Perrenot, B. Thermal decomposition of AgO to Ag2O. Thermochim. Acta 1985, 85, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Chen, M.; Yu, C.; Yang, Z.; Qi, Y.; Wang, F. High temperature self-lubricating Ti-Mo-Ag composites with exceptional high mechanical strength and wear resistance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 180, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenda, E. High temperature reactions in the MoO3–Ag2O system. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1998, 53, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.J. Elevated-temperature tribology of metallic materials. Tribol. Int. 2010, 43, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Ge, X.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J. In-situ formation of tribofilm with Ti3C2Tx MXene nanoflakes triggers macroscale superlubricity. Tribol. Int. 2021, 154, 106695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.