Abstract

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and porous organic frameworks (POFs) have been extensively explored in recent years as lubricant additives for various systems due to their structural designability, pore storage capacity, and tunable surface chemistry. These materials are utilized to construct low-friction, low-wear interfaces and investigate the potential for superlubricity. This paper systematically reviews the tribological behavior and key mechanisms of MOFs/POFs in oil-based, water-based, and solid coating systems. In oil-based systems, MOFs/POFs primarily achieve friction reduction and wear resistance through third-body particles, layer slip, and synergistic friction-induced chemical/physical transfer films. However, limitations in achieving superlubricity stem from the multi-component heterogeneity of boundary films and the dynamic evolution of shear planes. In water-based systems, MOFs/POFs leverage hydrophilic functional groups to induce hydration layers, promote polymer thickening, and soften gels through interfacial anchoring. Under specific conditions, a few cases exhibit superlubricity with coefficients of friction entering the 10−3 range. In solid coating systems, two-dimensional MOFs/COFs with controllable orientation leverage interlayer weak interactions and incommensurate interfaces to reduce potential barriers, achieving structural superlubricity at the 10−3–10−4 level on the micro- and nano-scales. However, at the engineering scale, factors such as roughness, contamination, and discontinuities in the lubricating film still constrain performance, leading to amplified energy dissipation and degradation. Finally, this paper discusses key challenges in achieving superlubricity with MOFs/POFs and proposes future research directions, including the design of shear-plane structures.

1. Introduction

Friction and wear are ubiquitous in various types of engineering equipment and household appliances, serving as primary causes of energy loss and equipment failure [1]. Data indicates that friction consumes one-third of the world’s primary energy, wear causes approximately 60% of mechanical component failures, and over 50% of mechanical equipment accidents stem from lubrication failure and excessive wear [2]. Therefore, effectively controlling and reducing friction and wear to enhance the efficiency and service life of mechanical components holds immense potential benefits for energy conservation, emission reduction, and improving equipment reliability.

With advancements in surface science and nanotechnology, tribological research has progressively transcended traditional boundaries. The focus has gradually shifted from low friction to the exploration of ultralow friction, or superlubricity. It is generally accepted that when the coefficient of friction drops to the 10−2 or even 10−3 range, the system enters a superlubricity state, exhibiting friction forces far below those achievable through conventional boundary lubrication or fluid lubrication [3,4]. Currently, relatively mature superlubricity systems include graphite/graphene [5], MoS2 [6], h-BN [7], and other layered micro- and nano-materials. These can be employed as solid-coating lubrication systems or as oil-based, ionic-liquid [8], water-based [9], or multi-phase composite lubrication systems [10]. However, these materials often exhibit significant sensitivity to environmental conditions, load, speed, and other factors, which pose notable limitations for long-term, stable lubrication and engineering applications [1].

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and porous organic frameworks (POFs, including covalent organic frameworks COFs, etc.) constitute a class of crystalline porous framework materials self-assembled from metal or organic nodes and organic ligands via coordinate or covalent bonds [11,12]. Owing to their highly tunable crystal structures, ultra-high specific surface areas, regular and controllable pore channels, and abundant organic/inorganic functional sites, MOFs/POFs have garnered extensive attention in gas storage and separation, catalysis, sensing, biology, and other fields [11,12,13,14,15]. Compared to traditional micro/nano materials, the cost of using MOFs/POFs remains essentially unchanged. However, a significant advantage of MOFs/POFs lies in their ability to design and control features such as metal nodes and ligands at the crystalline structural level, enabling flexible, tunable interfaces and chemical response behaviors at the macroscopic scale [16,17,18].

In recent years, numerous scholars have begun exploring the potential of incorporating MOFs/POFs into lubrication systems for friction reduction, wear resistance, and even superlubricity [19,20]. The tunable structures of MOFs/POFs offer diverse approaches for constructing ideal low-shear interfaces. Metal nodes and ligands can modulate framework stiffness, charge distribution, and chemical stability [11,20]; dimensionality and topological structures influence distinct friction mechanisms such as rolling, sliding, and film formation [21,22]; surface functionalization enables precise control over interfacial energy and wetting behavior, further affecting interfacial shear strength [23,24]. Previous work demonstrates that MOFs/POFs can participate in lubrication through multiple approaches: as nanoadditives in oil- or water-based lubricants to enhance stick-slip characteristics and lubricating film structure [25]; as additives in polymer or metal-based composites, exhibiting unique advantages over traditional additives in load-bearing capacity, wear resistance, and interface regulation [26]; or as porous scaffolds and “smart containers” for constructing porous self-lubricating surfaces or controlled release of friction-active molecules [27]. Across these diverse systems, leveraging the porous architecture, functionalizable surfaces, and structural evolution during shear of MOFs/POFs, most studies have achieved significant anti-friction and anti-wear effects [28,29,30].

However, existing research on MOFs/POFs lubrication systems that genuinely achieve friction coefficients at the 10−2 or even 10−3 level remains extremely limited. Most studies involving ZIF-8, Cu-BTC, Ni-MOFs, and similar materials as oil-based or water-based lubricant additives have not entered the strict realm of superlubricity. Only a small number of studies have demonstrated friction behavior approaching or reaching the superlubricity threshold under specific load and environmental conditions [31]. In particular, solid lubricant additives and interlayer sliding systems based on highly ordered two-dimensional MOFs have been developed. By controlling crystal orientation and interfacial states, these systems can achieve interlayer superlubricity at the 10−3 level, and even reach 10−4 [32,33]. These studies indicate that the potential of MOFs/POFs remains largely untapped, particularly in the design of superlubricity systems.

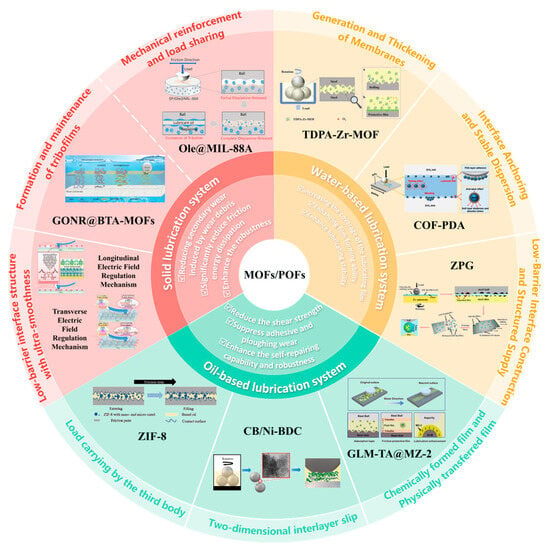

This paper outlines the structural characteristics and design variables of MOFs/POFs as lubricating materials, focusing on dimensionality and tunable parameters, including dimensional morphology, pore structure, surface chemistry, and defects, and guest-controlled properties. It then systematically reviews typical design strategies and the anti-friction/anti-wear performance of MOFs/POFs in oil-based, water-based, and solid-coating systems, summarizing their advantages and limitations across different media and operating conditions, as shown in Figure 1. The analysis focuses on a few MOFs/POFs systems that achieve superlubricity, comparing their structural features, interfacial evolution, and anti-friction mechanisms with those of conventional anti-friction systems. Finally, integrating existing experimental and theoretical research, this work discusses the primary challenges and potential opportunities for MOFs/POFs lubrication systems at both the engineering application and mechanistic levels. It provides a clear framework and direction for future material design of MOFs/POFs targeting superlubricity performance.

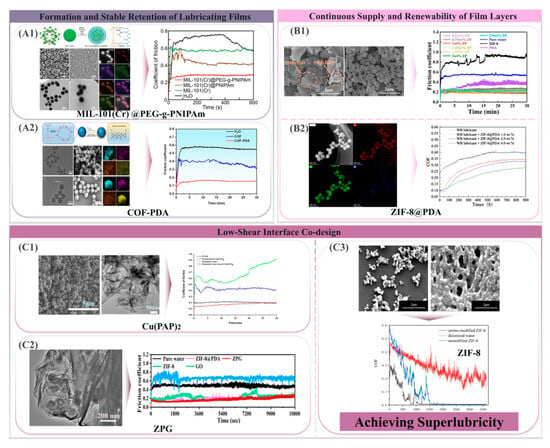

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the mechanism of MOFs/POFs with low friction and wear performance. Reproduced with permission from Refs. [21,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

2. Structural Basis of MOFs/POFs and Their Potential Advantages for Lubrication

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and porous organic frameworks (POFs, including covalent organic frameworks, COFs) represent a rapidly emerging class of porous framework materials in recent years. Their common feature is the construction of periodic frameworks at the molecular scale via a “node-linker” approach, forming regular channels or cages within the framework [11,12]. Compared to traditional inorganic porous materials (such as oxides [42] and zeolites [43]), MOFs/POFs exhibit greater design flexibility in framework composition, topological structure, and surface chemistry. This property contributes to their potential in superlubricity.

2.1. Fundamental Structural Characteristics of MOFs

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are self-assembled crystal network structures formed by metal ions or metal clusters (e.g., Cu2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Zr6O4(OH)4) acting as nodes, coordinated to polydentate organic ligands (carboxylic acids, imidazoles, pyridines, etc.) to create one-dimensional, two-dimensional, or three-dimensional networks [11,12]. Typical three-dimensional MOFs, such as the MIL-101 and UiO series, feature polyfunctional carboxylate ligands distributed around metal clusters, forming a “multi-chambered structure” with macroporous cages and interconnected channels. Their specific surface areas can reach several thousand m2g−1 [24,25,44]. This architecture provides excellent conditions for molecular adsorption, guest loading, and regulation of the lubrication interface. Beyond this, another representative class of MOFs tends to form layered or two-dimensional frameworks, such as Cu-MOFs, Ni-MOFs, and ZnBDC linked by aromatic dicarboxylic acids or heterocyclic ligands [45,46]. These structures typically feature rigid ligands periodically connected to metal nodes within a two-dimensional plane, with layers stacked via weak van der Waals forces or π-π interactions. Consequently, they exhibit potential low-shear slip planes in specific shear directions [19], laying the foundation for the design of super-sliding systems.

In their structural design, the metal nodes, ligand types, and their connection methods determine the framework’s topology and stiffness. Zr-based UiO frameworks exhibit high thermal and chemical stability due to the use of highly connected Zr6 clusters as nodes [44,47]; Certain transition metals combined with aromatic ligands exhibit both flexibility and structural rearrangement capabilities, enabling interlayer slip or localized structural reconfiguration under external forces [48,49]. During shear deformation, these characteristics enable some frameworks to maintain overall rigidity and bear loads, while others dissipate interfacial energy through localized structural adjustments or interlayer slip, thereby influencing friction and wear behavior [20]. Moreover, the organic ligands and metal nodes in MOFs inherently possess significant chemical reactivity. On the one hand, selecting ligands containing heteroatoms such as N, O, or S, or introducing elements such as P or S into the framework, can provide precursors for subsequent interfacial chemical reactions and the formation of tribochemical films [50,51]. On the other hand, polar groups, aromatic rings, or long-chain alkyl groups on organic ligands provide favorable conditions for grafting functional groups, regulating surface energy, and surface modification [50,52]. Therefore, as a material that can be precisely controlled in both structure and chemical reactivity, MOFs possess inherent advantages over other materials in lubrication and even superlubricity research.

2.2. Fundamental Structural Characteristics of POFs

Unlike MOFs, POFs are typically formed by multifunctional organic units connected by covalent bonds, such as C-C, C-N, C-O, or B-O, resulting in ordered or partially ordered two- or three-dimensional networks [37,53]. Because POFs lack metallic nodes, they differ significantly from MOFs in density, chemical stability, electronic structure, and interfacial interactions.

Two-dimensional COFs represent one of the most representative classes, characterized by frameworks composed of planar aromatic units periodically assembled via covalent bonds in the two-dimensional plane. This arrangement forms layered structures with well-defined pore sizes and highly π-conjugated systems. Layer-to-layer interactions are mediated by π-π stacking and van der Waals forces, resulting in the formation of two-dimensional crystals. This “strong covalent, weak interlayer” structure is exceptionally suited for bearing shear loads. It exhibits high in-plane stiffness and dimensional stability, while interlayer slip occurs relatively easily. Under suitable conditions, it can exhibit low shear strength, similar to that of graphene [54], or even superlubricity [37,53]. Within the lubrication field, the potential of POFs manifests in two primary aspects. First, through framework design, they can achieve flat, slip-permissive interlayer structures, providing a structural foundation for the formation of low-shear interfaces. Second, by introducing polar groups or dissociable groups into the framework, interactions with friction pair surfaces or synergistic effects with lubricant molecules can be enhanced, thereby enabling synergistic regulation of lubricants.

2.3. Common Structural Characteristics and Potential Advantages in the Lubrication Field

In summary, although MOFs and POFs exhibit significant differences in framework composition and bonding mechanisms, they share numerous common characteristics as structurally and functionally tunable porous materials for lubrication and superlubricity research. These very characteristics are precisely why they are regarded as a new generation of lubrication materials.

Whether MOFs or POFs, multiple-dimensional morphologies—ranging from micron- and nanoparticle-like structures and nanosheets to continuous films—can be achieved within the same structure by altering node types, ligand structures, and connection methods. From the “rolling bearing” effect of micro/nanoparticles, to the slip and delamination of nanosheets, and finally to the load-bearing capacity and interfacial shear forces of the entire coating, this enables systematic investigation within the same material system of how different dimensions influence the mechanisms governing lubrication optimization.

The frameworks of MOFs/POFs typically feature modifiable functional groups (hydroxyl, amino, halogen, etc.) or introduce long-chain organic segments and specific functional groups onto their surfaces through modification. This characteristic enables researchers to design lubrication additives with enhanced compatibility and targeted functionality for diverse lubrication environments, friction pair materials, and specific operating conditions. Such additives can both strengthen interfacial bonding to form stable physical adsorption or chemical reaction films and reduce interlayer interactions to facilitate interfacial sliding. The presence of flexible deformation and defects to some extent [26] also contributes to lowering the interlayer slip barrier or serves as functional sites for further structural regulation.

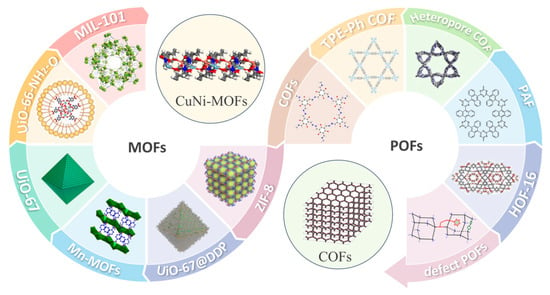

In recent studies, the porous framework and its internal pore structure have also positioned it as a “smart container,” offering abundant opportunities for loading small molecules, organic polymers, or inorganic nano-scale objects [44,49,55]. In lubrication systems, this capability can be leveraged to store lubricant or additive molecules, providing self-lubricating properties at interfaces. Additionally, by controlling pore size and specific surface area, the local structure of the lubricating film at interfaces can be influenced. This approach provides a material foundation for achieving low-friction lubrication. The typical structures of MOFs and POFs are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the structure of MOFs/POFs. Reproduced with permission from Refs. [20,24,25,35,44,46,53,56,57,58,59,60].

3. MOFs/POFs in Oil-Based Lubrication Systems

Oil-based lubrication systems represent the most widely applied and formulaically mature category in engineering friction pairs. Consequently, they constitute the earliest validated and most systematically researched primary direction for MOFs/POFs entering the field of tribology. Recent research has gradually shifted focus from treating porous framework materials as solid particles to exploring how, under low-polarity oil phases and complex additives, these materials can stably enter contact zones and induce the formation of load-bearing, slip-capable, and self-renewing boundary lubrication films. In this process, the material’s dimensional morphology, surface chemical modification, and composite methods collectively determine the upper limit of its anti-friction and anti-wear performance, as well as the key gap that still exists between it and the superlubricity threshold.

3.1. Lubricating Properties of MOFs/POFs in Oil-Based Lubrication Systems

Early explorations of oil-based lubrication systems predominantly treated MOFs as morphologically controllable solid particles, with research methodologies largely following the classical nanoparticle-additive approach. This stems from the particle-dominated third-body-bearing and pit-filling repair mechanisms being among the more readily achievable pathways to favorable tribological performance in oil phases. Particulate MOFs, exemplified by ZIF-8, can synergistically leverage both nano-scale and micron-scale particles in base oils. Specifically, nanoparticles preferentially fill roughness peaks and valleys while sharing localized loads, while micron-sized particles provide rolling and support functions. This approach reduces the friction coefficient by approximately 63.33% compared to the base oil alone [21]. Similarly, MOFs coupled with clay minerals or surfactant shells can jointly exert third-body load-carrying effects, often enhancing load-carrying and wear suppression at lower addition levels [28,29]. Hongxiang Yu et al. compared the influence of different metal nodes and framework structures on friction coefficients and wear volumes, concluding that MOFs contributions depend not only on solid particle morphology but also closely correlate with surface chemistry and structural stability [61]. Relying solely on third-body particle effects typically favors wear resistance rather than effectively reducing the friction coefficient.

As research deepens, scholars have begun focusing on dimensional and morphological control, advancing particle systems toward layered and structured interfaces. The core objective is to shift the shear plane from direct metal contact to low-barrier interfaces. Fei-Fei Wang et al. obtained Zn-BDC nanosheets via surfactant-assisted ultrasonication, discovering that two-dimensional layers exhibit distinct interfacial behavior compared to zero-dimensional particles in terms of load-bearing capacity and interfacial adsorption lubrication [22]. This prompted research to target the formation of continuous, low-shear slip films as an optimization goal. However, agglomeration and sedimentation of layered materials in oil directly impede their contact with the contact zones and film formation, causing fluctuations in friction curves and limiting further friction reduction [62]. Subsequent work often addressed this by introducing heterostructures or spacers to suppress stacking and stabilize low-shear interfaces. Huawen Zhu et al. constructed CB/Ni-BDC nanocomposite sheets using calcium borate particles as spacers to inhibit layer stacking and prevent direct contact between friction pairs, achieving more stable friction coefficient reduction and improved wear scar diameter in 150SN base oil [34]. The authors further proposed a ZIF-7/2D Ni-BDC heterostructure. By leveraging nanoparticle pit-filling load-bearing and slip between nanosheets, they achieved more pronounced anti-friction and anti-wear effects in liquid paraffin [63]. Correspondingly, ultrathin layered structures were found to more effectively reduce shear resistance in the contact zone and improve wear scar morphology in liquid paraffin, demonstrating a direct correlation between structural morphology and interfacial shear strength [64]. Fan Xue et al. compared that “sheet-sheet” structures exhibited superior anti-friction effects, while “sphere-sheet” structures showed better anti-wear performance [30]. Furthermore, designs targeting oil-based dispersibility of 2D Cu(2,6-NDC) nanosheets revealed that adjusting ligand structures and layering characteristics alter their dispersibility and lubrication performance in castor oil [65]. Incorporating nanocomponents, such as carbon dots, into two-dimensional Ni-BDC systems can also synergistically reduce friction and improve wear scar morphology via interfacial lubrication/dispersion effects [45]. The aforementioned studies on layered structures and structuralization have shifted subsequent research toward forming continuous, load-bearing, low-shear lubricating films in friction contact zones using lubricating additives.

In research aiming to achieve good oil-phase dispersibility and interfacial lubrication film formation, surface functionalization and composite modification of MOFs/POFs have emerged as viable approaches. Wenxing Niu et al. proposed using MOFs channels as a carrier and controlled-release platform for friction-active molecules, combining the extreme-pressure behavior of SIB guests with the properties of ZIF-8 to yield more stable, lower-friction curves under high loads [23]. Jianxi Liu et al. functionalized UiO-67 with phosphate ester molecules, revealing that the modified repair effect is crucial for the formation and stability of boundary lubrication films [24]. Lubrication systems using DDP-functionalized UiO series materials also demonstrate that functionalized MOFs can simultaneously serve as friction-reducing additives and lubricant antioxidants in lubricant formulations [66]. Furthermore, synergistic use of ionic liquids with UiO materials enhances boundary adsorption layers and composite film formation, achieving a minimum friction coefficient of approximately 0.055 in PAO and reducing wear volume by about 95% [67,68,69,70]. Regarding composite development, Heng Zhang et al. constructed the OA-ZIF-8/GO composite additive. The oleic acid segments enhance lipophilicity and dispersion, while wrinkled GO nanosheets provide loading capacity and slip behavior. ZIF-8 reinforces material stiffness and film-forming ability, yielding excellent friction and wear behavior in white oil systems [71]. In the UiO-66-NH2@fluorinated graphene composite system, fluorinated graphene provides low-shear layered slip and a wear-resistant framework. MOFs enhance adsorption and film-forming properties through their pore networks and surface chemistry, improving interfacial compatibility and significantly optimizing tribological characteristics [46]. By adjusting MOFs’ size and composite methods, more stable reductions in oil friction coefficient were achieved, with wear volume reductions reaching up to 97.2% [33]. Furthermore, Ag@Co-BDC can achieve a friction coefficient of 0.085 and reduce the wear scar diameter by approximately 61.5% in PAO10 by being added at a 0.1 wt% concentration [72]. While UiO-67@PLMA enhances system stability through polymer grafting, yielding a friction coefficient of approximately 0.111 and a 75.5% reduction in scuff diameter when added to base oil [73]. Even in higher-viscosity synthetic oils, the composite materials maintain effective friction reduction [46,51]. These studies demonstrate that achieving both low friction and long-term anti-wear performance in oil-based lubrication systems requires integrated material regulation and synergistic optimization of key characteristics: stable dispersion, optimized interfacial modification, and friction-induced chemical film formation.

As research increasingly focuses on extended service life and demanding operating conditions (high loads, elevated temperatures, etc.), the advantages of MOFs’ functionalization, composite structures, and POFs’ ability to form stable transfer films become increasingly evident. Yi Wang et al. prepared N-doped porous carbon nanosheets (DTD-N@PCNs) from Cu-MOFs precursors, which maintained excellent tribological properties under a load of 400 N [48]. Zhang et al. introduced thiazole groups onto COFs-F via ball-milling mechanochemistry (Thdz@COFs-F), achieving a 39.6% reduction in average coefficient of friction, an 87.0% decrease in wear volume, and a load-carrying capacity enhanced to 650 N [74]. Shenghua Xue et al. further introduced functional components such as MBT to obtain MBT-N@PCNs, achieving an almost sevenfold increase in extreme pressure capability and significantly enhanced thermal stability. This demonstrates that the synergistic interaction between carbon-based transfer films and active components involved in film formation is crucial for anti-friction and anti-wear performance under high-pressure conditions [55]. Simultaneously, multi-element doping can enhance both adsorption onto metal surfaces and the stability of film formation. For instance, co-doping carbon nanosheets with B and N elements (B,N@PCNS) reduced wear volume by over 90% [49]. B, N, P-doped porous carbon nanosheets (B,N,P@PCNs) similarly exhibited significant anti-friction and anti-wear effects [75]. Regarding POFs systems, Haoyuan Yang et al. enhanced oil dispersibility and interfacial film-forming capability by introducing structural units like γ-CNQDs into COFs frameworks [53]. COFs are also employed to construct supramolecular oil gels, thereby enhancing lubricant retention and sustained delivery, maintaining more stable lubrication states, and reducing wear [44,50]. Hongyang Wang et al. utilized CONs as additives, proposing a friction-induced built-in electric field to drive ion migration and generate a “pinning effect,” thereby achieving excellent friction reduction and wear resistance [13].

Overall, the research trajectory of oil-based systems has evolved from focusing on morphology-controlled solid particles to emphasizing the structured design and optimization of boundary lubrication films, with typical structures illustrated in Figure 3. Through two-dimensionalization, heterostructures, functionalization, and composites, the film-forming efficiency and low shear strength in friction contact zones are enhanced. Concurrently, the robustness and tribological performance of physically transferred films and friction-chemical films are improved, enabling stable, low-friction, and high-wear resistance under more complex, variable operating conditions. Table 1 summarizes the typical tribological properties and test conditions of MOFs/POFs when used as oil-based lubricant additives, enabling rapid comparison of the friction-reducing/anti-wear effects of different materials under identical friction pairs and conditions. Performance is uniformly denoted as “CoF: x (↓y%)”, where x represents the coefficient of friction after incorporating the porous framework material, and y indicates the reduction in friction coefficient relative to the baseline lubricant without the material under identical conditions. The addition levels listed correspond to actual formulation concentrations used in the referenced literature; the “optimal addition level” is valid only within the specific test ranges and conditions documented in the corresponding literature.

Table 1.

Different types of porous framework materials as oil-based lubricant additives.

Table 1.

Different types of porous framework materials as oil-based lubricant additives.

| Additives | Basic Medium | Additive Content (Best*) | Tribometer | Tribological Performance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONs | PEG 400 | 0.5 wt% | Reciprocation tribometer (SRV-V) | CoF: ~0.08 | [13] |

| ZIF-8 | 150SN | 1.0 wt% | Four-ball friction tester | CoF: 0.033 (↓63.33%); AWSD: 18.18% | [21] |

| Zn-BDC | liquid paraffin | 0.05 wt% | MFT-5000 | CoF: ~0.2; AWV: 63.54% | [22] |

| SIB@ZIF-8 | PAO8 | 0.7 wt% | Optimol SRV-V oscillating reciprocating friction and wear tester | CoF: 0.1–0.2; | [23] |

| UiO-67@DDP | 500SN | 0.2 wt% | High-frequency linear friction and wear tester (SRV-V) | CoF: 0.099 (↓>50%); AWV: 50–70% | [24] |

| Ni-BTC MOFs@HNTs | 150SN | 0.04 wt% | Four-ball friction machine | CoF: 0.043 (↓39.7%); AWSD: 29.4% | [28] |

| CS@Cu(BDC) | GL-5 | 0.5 wt% | Reciprocating ball-on-disk tribometer | CoF: 0.074 (↓62.2%); AWSD: 33.9% | [29] |

| Ni-MOFs/g-C3N4 | 150SN | 0.2 wt% | Four-ball friction tester (MMW-1) | CoF: 0.073 (↓37.07%); AWSD: 42.15% | [30] |

| CB/Ni-BDC | 150SN | 0.15 wt% | Four-ball friction machine (MMW-1) | CoF: ~0.1 (↓37.42%); AWSD: 28.13% | [34] |

| GLM-TA@MZ | PAO10 | 2.0 wt% | SRV-5 tribometer | CoF: 0.091 (↓52.36%); AWSD: 97.2% | [35] |

| TDPA-Zr-MOFs | soybean oil | 0.1 wt% | Four-ball test machine (MS-10A) | CoF: ~0.06 (↓>35%); AWSD: >35% | [36] |

| UiO-66-NH2-O | PAO6 + 12-HSA gel | 0.2 wt% | Four-ball machine | CoF: ~0.065 (↓30.84%); AWSD: 50.07% | [44] |

| N-CDs/2D Ni-BDC | castor oil | 0.04 wt% | Four-ball friction machine | CoF: ~0.05 (↓66.67%); AWSD: 30.64% | [45] |

| Zr-MOFs@FG | PAO4 | 0.5 wt% | Ball-on-disk tribometer (MST-3000) | CoF: ~0.04 (↓70.2%); AWSD: 62.7% | [47] |

| DTD-N@PCNs | 500SN | 1.0 wt% | SRV-V tribometer | CoF: 0.110 (↓43.6%); AWSD: 69.3% | [48] |

| B,N@PCNS | PAO10 | 2.0 wt% | Optimal SRV-5 tribometer | CoF: 0.088; AWSD: 91.3% | [49] |

| TC18@DT-COF | PAO40 oil gel | 0.5 wt% | SRV-V tester | CoF: 0.093; AWV: 9.0 × 104 μm3 | [50] |

| FeOCl/Zn-MOFs | PEG200 | 0.4 wt% | MM-W1A (four-ball mode) | CoF: 0.042 (↓48%); AWSD: 88% | [51] |

| g-CNQDs/CCOF | PAO10 | 3.0 wt% | SRV-5 tribometer | CoF: 0.095 (↓44.8%); AWSD: 82.0% | [53] |

| MBT-N@PCNs | 500SN | 0.10 wt% | SRV-V tribometer | CoF: 0.103 (↓41.1%); AWSD: 85.4% | [55] |

| Ni-MOFs | 500N | 0.1 wt% | Reciprocating tribometer | CoF: 0.042 (↓33.2 ± 12.4%); AWSD: 98.7 ± 0.14% | [61] |

| Zn(Bim)(OAc) | liquid paraffin | 0.06 wt% | Slider reciprocating tester (MFT-5000) and four-ball friction machine (MMW-1) | CoF: 0.131 (↓17.0%); AWSD: 22.6% | [62] |

| ZIF-7/2D Ni-BDC | liquid paraffin | 0.08 wt% | Four-ball friction machine (MMW-1) | CoF: ~0.08 (↓39.7%); AWSD: 18.03% | [63] |

| Mn-MOFs (U) | liquid paraffin | 0.15 wt% | Four-Ball Lubricant Tester | CoF: 0.043 (↓45.57% | [64] |

| 2D Cu(2,6-NDC) | castor oil | 0.08 wt% | Four-ball friction tester (MMW-1) | CoF: ~0.06 (↓42.7%); AWSD: 58.9% | [65] |

| UiO-66@DDP | 500SN | 0.4 wt% | SRV-5 tribomachine | CoF: 0.113 (↓47.39%); AWSD: ~50% | [66] |

| Mo-MOFs | PAO10 + N/P | 0.15 wt% | Four-ball tribometer | CoF: 0.055 (↓31.25%); AWSD: 95% | [67] |

| PIL-PF6@DT-COFs | PAO10 | 3.0 wt% | SRV-V tribometer | CoF: 0.094 (↓44.38%); AWSD: 82.9% | [70] |

| OA-ZIF-8/GO | white oil | 1.0 wt% | Four-ball friction machine | CoF: 0.082 (↓31.4%); AWSD: 35.2% | [71] |

| Ag@Co-BDC | PAO10 | 0.1 wt% | Ball on disk friction testing machine (CFT-I) | CoF: 0.085 (↓16.7%); AWSD: 61.5% | [72] |

| UiO-67@PLMA | 500SN | 0.6 wt% | High-frequency linear friction and Wear testing machine (SRV-V) | CoF: 0.111 (↓45.3%); AWSD: 75.5% | [73] |

| Thdz@COFs-F | PAO10 | 3.0 wt% | SRV-V tribometer | CoF: 0.102 (↓39.6%); AWSD: 87.0% | [74] |

| B,N,P@PCNs-2 | 500SN | 3.0 wt% | Optimal SRV-5 tribometer | CoF: 0.104 (↓42.22%); AWSD: 77.5% | [75] |

| CD@CuCo-MOFs | PETE | 0.1 wt% | Rtec MFT5000 multifunctional friction tester | CoF: 0.035 (↓61.1%) | [76] |

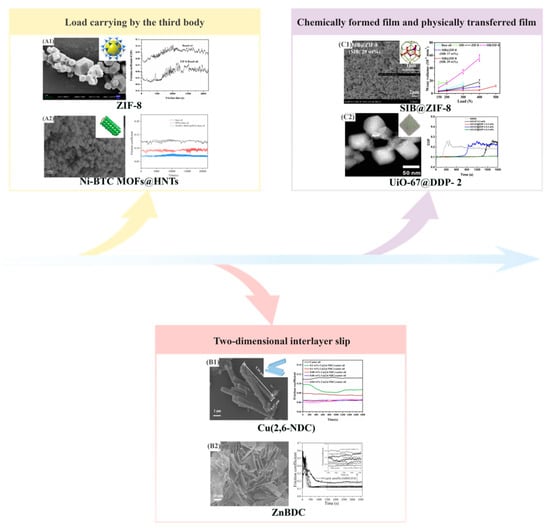

Figure 3.

(A1) Friction-reducing properties of ZIF-8 in base oils and its nano-scale and micrometer-scale morphological characteristics. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [21]; (A2) SEM images of Ni-BTC MOFs@HNTs and its friction curve. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [28]; (B1) SEM images of Cu(2,6-NDC) microbars and its friction curve. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [65]; (B2) SEM images of ZnBDC and its friction curve. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [22]; (C1) SEM images of SIB@ZIF-8 and its wear volume curve. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [23]; (C2) STEM images of UiO-67@DDP and its friction curve. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [24].

3.2. Lubrication Mechanisms and Performance Bottlenecks

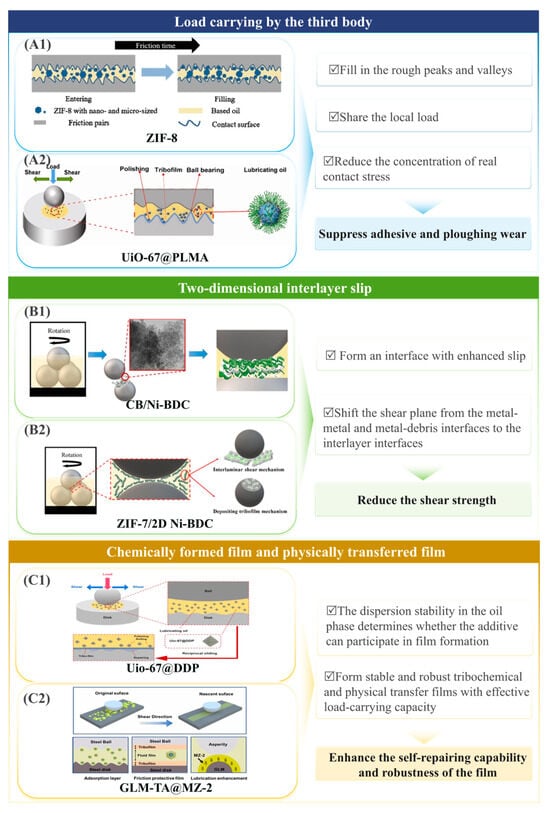

The anti-friction and anti-wear mechanisms of MOFs/POFs in oil-based systems exhibit significant superposition. The same system often simultaneously involves processes such as third-body load-bearing, interlayer sliding, friction chemical films, and physical transfer films. Its tribological properties vary with operating conditions, base oil type, load, speed, friction pair materials, and additive structure. Therefore, the lubrication mechanism in oil-based systems can be more clearly summarized into three points: Third-body particle systems emphasize load-carrying capacity, repair, and interfacial penetration; Two-dimensional and heterogeneous structures focus on shear interface transfer and low-barrier sliding; Functionalized and structured systems prioritize the formation and robustness of physical adsorption films and friction chemical films. These factors collectively determine whether a sustainable, low-friction boundary lubrication film can form.

As a prerequisite for these processes, the dispersion stability in the oil phase determines whether additives can continuously enter the friction contact zone and participate in film formation. For non-polar or weakly polar base oils, agglomeration and sedimentation of MOFs/POFs particles or flakes will lead to insufficient additive supply in the friction contact zone and hinder continuous lubricating film formation. Consequently, friction curves will fluctuate or deteriorate over time. Therefore, enhancing the additive’s ability to enter the friction contact zone directly determines whether the subsequent mechanisms—load-carrying repair, shear transfer, and sustained film formation—can genuinely occur and be sustained long-term within the contact zone. The interactions between MOFs/POFs and lubricants can be categorized into dispersion, adsorption, and tribochemical reactions. First, surface functional groups or composite structures of porous framework materials can alter particle oil-phase compatibility and dispersion stability, thereby determining whether additives can continuously enter the contact zone and participate in lubricating film formation. Second, the physical adsorption of framework materials on metal surfaces and interactions at polar sites can promote the enrichment of lubricant molecules and active components at the interface, forming a more stable boundary adsorption layer. Third, under shear and friction-induced conditions, active sites on additive surfaces and released active molecules can participate in friction chemical reactions. This generates a denser friction chemical film that interacts with the physically transferred film, causing shear to preferentially occur within low-barrier interfaces. Consequently, this enhances the robustness of low-friction performance.

First, for oil-based lubrication systems primarily composed of MOFs/POFs particles, the most stable and common contributions remain third-body load-bearing and pit-filling repair. Once particles enter the contact zone, they can fill roughness peaks and valleys, share local loads, and reduce the accuracy of contact stress concentration, thereby suppressing adhesion and plowing wear. Simultaneously, particle rolling and sliding, along with surface adsorption, can promote the formation of a physical adsorption film and a mixed boundary layer, significantly lowering the friction coefficient relative to the base oil [21,28,29]. However, this pathway exhibits a noticeably lower limit for friction reduction. The boundary film is often a multi-phase hybrid film composed of lubricant molecules, wear debris, and reaction products. The shear plane readily migrates between interfaces, stabilizing the friction coefficient at the 10−2 order of magnitude and making it difficult to achieve further long-term reductions. Therefore, particle systems more reliably enhance anti-wear and friction stability within the oil phase. To further reduce the friction coefficient, the shear plane must be transferred from within the mixed film to a more readily slidable interface with a lower potential barrier.

Therefore, two-dimensional layered structures and heterostructures provide a structural basis for reducing shear barriers, with the key being to transfer the shear plane and maintain it at low-barrier interfaces as much as possible. Two-dimensional MOFs/POFs or layered composite structures may form more slip-prone interfaces in the shear direction, thereby shifting the shear plane from metal-metal or metal-abrasive particle interfaces to low-barrier interfaces such as layer-layer or heterostructure interfaces [52,69]. This is also the fundamental reason why layered systems have a greater opportunity to achieve superior tribological performance under certain operating conditions. However, factors such as flake material agglomeration and sedimentation in the oil phase, along with shear-induced fragmentation, can directly disrupt the lubrication film’s continuity [62]. Consequently, this approach often requires optimization through heterogeneous structures, spacer layers, and composite dispersion methods to sustain the low-barrier sliding effect [30,65].

Furthermore, the core value of functionalizing and compositing MOFs/POFs lies in enhancing the formation efficiency, continuity, and robustness of boundary films, thereby transforming low friction from a transient phenomenon into a sustainable steady-state behavior. Functionalized MOFs provide well-defined active sites and film-forming precursors (e.g., P/S/N/O-containing components), promoting the formation of denser friction chemical films. Pore encapsulation, controlled release, and interfacial modification facilitate the enrichment of active components in contact zones and their participation in sustained film formation. Concurrently, composites of MOFs with 2D materials, carbon-based materials, or polymers achieve a better balance between loading, dispersion, and interfacial adhesion. This results in more continuous, shear-resistant physical transfer films and frictional chemical films [77]. Under severe operating conditions, MOFs-derived carbons with multi-element doping or multi-system composites further enhance film density and thermal/shear stability, thereby better sustaining long-term, low-friction, anti-wear performance [26,27,44]. Overall, functionalization and composites are key to addressing the challenge of sustained, long-term lubricating film formation in oil-based lubrication systems using porous framework materials.

Finally, the challenge of achieving and maintaining superlubricity in oil-based lubrication systems remains centered on the long-term preservation of continuous, low-shear interfaces. Oil-based boundary lubrication films typically consist of lubricant molecules, additives, wear debris, and reaction products, exhibiting highly heterogeneous structures that dynamically evolve. Even when localized low-barrier sliding interfaces form, they are easily disrupted by particle embedding, reaction product accumulation, lamellar disturbance, and contact with roughness peaks, leading to shear forces reverting to the multi-phase interface. The lubrication mechanism diagram is shown in Figure 4. In recent years, systematic designs such as oil-ionic liquid composites and oil gels with Pickering emulsions [67,78,79] have partially addressed issues of insufficient supply in contact zones and film rupture. Further functionalization and the use of composites promote continuous film renewal, resulting in more stable, lower friction coefficients. However, to truly achieve and sustain superlubricity over the long term, targeted synergistic regulation remains essential across three key areas: constructing low-barrier interfaces in materials, enabling self-healing of the film layer, and achieving robust film formation.

Figure 4.

(A1) The friction-reducing mechanism of ZIF-8 with nano-and micro-sized morphologies. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [21]; (A2) Lubrication mechanism of the UiO-67@PLMA as an additive. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [73]; (B1) Schematic lubrication mechanism of the CB/Ni-BDC nanomaterials in base oil. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [34]; (B2) Schematic lubrication mechanism of the ZIF-7/2D Ni-BDC heterostructure in liquid paraffin. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [63]; (C1) The anti-friction and anti-wear mechanism of UiO-67 @DDP nanoparticles additives in lubricating oil. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [24]; (C2) Lubrication Mechanism of GLM-TA@MZ-2 as Nanolubrication Additive. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [35].

4. MOFs/POFs in Water-Based Lubrication Systems

Water-based lubrication systems are regarded as key systems for achieving green and biolubrication due to their advantages of low viscosity, strong heat dissipation, and environmental friendliness. Compared to oil-based systems, aqueous systems are more prone to lubricant film extrusion and insufficient lubrication in the contact zone under high loads. It is also more difficult for the boundary film to form a continuous, load-bearing, and long-lasting low-shear interface. Simultaneously, the influence of cations, anions, pH, and solution components on interfacial hydration structures and surface chemical reactions within the friction pair is significantly magnified, leading to greater fluctuations in lubrication performance. Against this backdrop, MOFs/POFs, leveraging their designable channels, surface functional groups, and structural morphologies, have increasingly been employed in systematic designs for water-phase systems. These approaches first stabilize the lubricating film and subsequently reduce shear barriers. On one hand, methods such as hydrated soft layers and polymer layers thicken the lubricating film while reducing shear strength. On the other hand, interfacial anchoring and synergistic film formation enhance film continuity and erosion resistance. Under specific ceramic-water lubrication conditions, superlubricity cases with friction coefficients approaching 10−3 have been observed, providing more explicit material and interfacial design insights for water-based superlubricity.

4.1. Lubricating Properties of MOFs/POFs in Water-Based Lubrication Systems

The most immediate challenge in water-based lubrication systems is the thinness of the lubricating film and its susceptibility to being squeezed out of the friction contact zone. Consequently, representative approaches in related research often prioritize thickening and stabilizing the lubricating film structure rather than simply treating porous framework materials as solid particle additives. A typical example is the MIL-101(Cr)@microgel core–shell system. Researchers, including Wei Wa [25], Wei Wu [80], and Lejie Tian [81], constructed hydratable, reconfigurable soft layers on the MOF surface. This allows the lubricating film to maintain more stable, continuous coverage during shear processes. The MOFs themselves also provide essential mechanical support, preventing the interface from collapsing completely into direct contact between the friction pairs. This approach yields lower, smoother friction curves in pure water, with all three studies achieving average friction reductions exceeding 80%. Similarly, constructing strongly hydrated interfaces using polyelectrolyte brushes (e.g., UiO-66-NH2@PSPMK [82] and TD-COF-PSPMA [83]) significantly reduces wear volume and improves friction stability in pure water. Collectively, these studies point to a unique conclusion for water-based systems: material design must first prioritize the formation and maintenance of stable lubricating films in the aqueous phase before further reducing shear barriers and friction coefficients through structural details, as illustrated by the typical structure shown in Figure 5(A1).

Within the aforementioned design framework centered on lubricating films, research has further extended to the regulation of interfacial environments. As an example of interfacial anchoring, Peiwei Gong et al. constructed a ZIF-8-PDA-HA system in which PDA provides adhesion and fixation, while HA provides intense hydration and a water-retaining layer. This prevents the lubricating film from being squeezed out during reciprocating conditions, significantly reducing friction and wear [84]. Shudan Wang et al. coupled COFs with a PDA soft layer to construct a COFs-PDA system that maintained low friction and wear even during prolonged operation under aqueous conditions [37]. Correspondingly, when the medium composition expanded from deionized water to buffered systems such as PBS, research by Gang Huang et al. on Cu-MOFs in PBS and PVA environments indicated that the solution’s ionic environment and interfacial hydration stability more directly determine macroscopic friction behavior. Lubricating films in aqueous systems must not only form but also resist solution erosion and ionic disturbance to maintain effective coverage [85]. Therefore, the ability of the film layer to persist and undergo steady-state renewal in water-based lubrication systems is more critical for long-term lubrication performance, as illustrated by its typical structure in Figure 5(A2).

Addressing the critical issue of retention, both structural stability and dispersion stability of MOFs/POFs in water-based lubrication systems are equally vital. Qiao Tian et al. enhanced ZIF-8′s dispersion and interfacial adhesion in water by coating with PDA, enabling ZIF-8@PDA to exhibit lower friction and significantly reduced wear volume in deionized water [86]. Furthermore, to mitigate membrane disruption caused by insufficient lubrication in aqueous lubrication, oil-water multi-phase Pickering emulsions offer an alternative approach to structured supply. By stabilizing oil droplet interfaces with N-CDs/2D Ni-BDC, carbon dots form protective layers preferentially during the early friction stages. Subsequently, shear forces induce dynamic emulsion breakdown, releasing platelets to participate in the formation of the lubrication film. This mechanism maintains friction within a low range while reducing wear rates [87,88,89]. This result demonstrates that, in water-based lubrication systems, enhancing continuous replenishment and film regenerability in the contact zone through structured delivery can mitigate film squeezing to some extent. This approach complements the previously discussed interfacial anchoring method, with typical structures shown in Figure 5(B1,B2).

After achieving stable lubrication film formation, research shifted to the construction of structures for lower-friction interfaces. Lei Li et al. discovered the potential low-shear slip advantage of layered structures in aqueous phases [90]; however, translating this advantage into steady-state low friction in aqueous media still generally relies on dispersion stabilization and composite film formation to lock the shear interface. For instance, ZIF-8@PDA/GO composite films in water enhance interfacial coverage and shear disturbance resistance, resulting in lower friction and significant wear reduction [38]. Regulating 2D Cu(2,6-NDC) with phytic acid (PA) improves dispersion and film-forming capabilities, further lowering the coefficient of friction in pure water [91]. Overall, tribological performance optimization in aqueous systems stems from the synergistic interactions among multiple mechanisms. This requires not only low-shear interface design but also the presence of relevant hydration films or composite film structures that can stably maintain this interface within the contact zone. Typical structures are shown in Figure 5(C1,C2).

Figure 5.

(A1) SEM and TEM images of MIL-101(Cr)@PEG-g-PNIPAm, along with its synthesis method and friction curve. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [80]; (A2) Construction of COFs-PDA lubricating system and its friction curve. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [37]; (B1) SEM and XRD pattern of ZIF-8@PDA and its friction coefficient curves. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [86]; (B2) A HAADF-STEM photography of ZIF-8@PDA crystal and elemental mapping and CoF vs. time at various lubrication scenarios. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [92]; (C1) SEM images of Cu(PAP)2 and its coefficient of friction curves. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [90]; (C2) TEM images of ZIF-8 @PDA/GO and its long-term lubrication performance. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [38]; (C3) SEM images of Unmodified ZIF-8 nanoparticles and Amino-modified ZIF-8 nanoparticles and their coefficient of friction curves. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [31].

Currently, ceramic water lubrication is the only water-based system that has truly achieved superlubricity. Tianyi Sui et al. reported that NH2-ZIF-8 can achieve superlubricity, with a friction coefficient of approximately 0.0049, under a 30 N load and specific conditions in Si3N4 ceramic water lubrication [31]. The synergistic hydration and adsorption behavior induced by NH2-ZIF-8 form a continuous, dense, and low-shear composite lubricating film with the silica gel film generated during shearing. This allows the shear interface to remain more stable between low-barrier film layers and exhibits a certain degree of regenerative characteristics. Therefore, water-based superlubricity relies more on factors such as the friction environment, the medium’s chemical composition, and synergistic film stabilization than on the material’s intrinsic properties. Its typical structure is shown in Figure 5(C3). Table 2 summarizes the tribological performance and key conditions of MOFs/POFs in water-based lubrication systems, facilitating comparison of performance differences under various dispersion/modification strategies.

Table 2.

Different types of porous framework materials as water-based lubricant additives.

Table 2.

Different types of porous framework materials as water-based lubricant additives.

| Additives | Basic Medium | Additive Content (Best*) | Tribometer | Tribological Performance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIL-101(Cr)@PNIPAm | deionized water | 20 mg mL−1 | UMT turbomachine | CoF: 0.29 (↓60.81%); AWSD: 73.6% | [25] |

| NH2-ZIF-8 | deionized water | 1.0 wt% | MMW-1 friction test machine | CoF: 0.0049 | [31] |

| COFs-PDA | deionized water | 7 mg mL−1 | CFT-I surface comprehensive tester | CoF: 0.13 (↓77.59%); AWSD: 96.31% | [37] |

| ZIF-8@PDA/GO | deionized water | 1.0 wt% | Ball-on-disk tribometer (MST-3000) | CoF: 0.13 (↓82%); AWSD: 83% | [38] |

| MIL-101(Cr)@PEG-g-PNIPAm | deionized water | 15 mg mL1 | UMT turbomachine | CoF: 0.28 (↓64.2%); AWSD: 86.5% | [80] |

| MIL-101(Cr)@P(NIPAm-g-PEGMa3) | deionized water | 5 mg mL−1 | UMT turbomachine | CoF: 0.26 (↓58.06%); AWSD: 95.75% | [81] |

| UiO-66-NH2@PSPMK | deionized water | 20 mg mL−1 | UMT turbomachine | CoF: 0.2 (↓64.91%); AWSD: 99.1% | [82] |

| TD-COF-PSPMA | deionized water | 0.5 wt% | Universal material tester (UMT- Tribo) | CoF: 0.17 (↓71%) | [83] |

| ZIF-8-PDA-HA | deionized water | 3.5 mg mL−1 | Precision friction and wear testing machine (TRB3) | CoF: 0.13 (↓75%) | [84] |

| P/H-Res@Cu MOFs | PBS/PVA | 1 mg mL−1 | Digital actor | CoF: (37.36%); | [85] |

| ZIF-8@PDA | deionized water | 1.0 wt% | Rotary friction and wear testing | CoF: 0.1853 (↓65%); AWSD: 66% | [86] |

| 2D ZIF-11 | oil-in-water emulsion | 0.25 wt% | MFT 5000 type multi-function friction and wear tester | CoF: 0.10 | [87] |

| 2D Ni-BDC | oil-in-water emulsion | 2.8 wt% | Reciprocating friction testing machine (MFT-5000) | CoF: 0.12–0.13 (↓61.1%); AWSD: 67% | [88] |

| N-CDs/2D Ni-BDC | oil-in-water emulsion | 2.8 wt% | Reciprocating friction tester (MFT-5000) | CoF: ~0.1 (↓66%); AWSD: 69% | [89] |

| PA-W-Cu(2,6-NDC) | deionized water | 0.1 wt% | - | CoF: ~0.2 (↓34.9%); AWSD: 24.8% | [91] |

| ZIF-8@PDA | WB | 4.0 wt% | Reciprocating tribometer | CoF: 0.228 (↓33.9%); AWSD: 34.4% | [92] |

4.2. Mechanism of Lubricating Film Formation and Superlubricity Mechanism

Overall, the tribological behavior of water-based MOFs/POFs additive systems is more strongly influenced by the interfacial lubricating film. Unlike the film-forming-shearing-refilming process commonly observed in oil-based lubrication systems, the film layer in water-based systems is more prone to being squeezed out of the friction contact zone under load and shear. This leads to frequent migration of the shear plane between the lubricating film and rough peaks, resulting in fluctuating friction curves and elevated steady-state friction coefficients. Therefore, the mechanism of MOFs/POFs in water-based lubrication systems centers on the lubricating film. The mechanism diagram for water-based lubrication systems, as shown in Figure 6, illustrates the progression from lubricating film formation and thickening, through interfacial anchoring and stabilization, to the construction and maintenance of low-shear interfaces within the film. This ultimately leads to the realization of synergistic superlubricity under specific conditions. The chemical interactions between MOFs/POFs and the aqueous phase are primarily manifested as interfacial hydration and anchoring coupling. Hydrophilic groups on the porous framework material surface, polymer coating layers, or multipoint interaction sites can enhance their fixation and continuity on the friction pair surface through mechanisms such as hydrogen bonding or electrostatic adsorption. Simultaneously, by trapping water molecules to form a stable hydration layer and improving the membrane’s extrusion resistance, they enhance the stability of the friction curve.

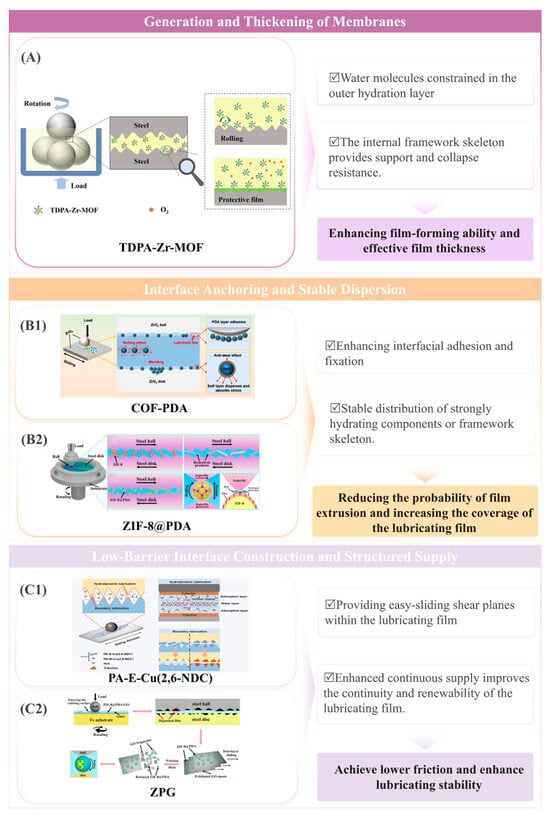

Figure 6.

(A) Schematic lubrication mechanism of the TDPA-Zr-MOFs in base oil. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [36]; (B1) Schematic diagram of the friction mechanism of COFs-PDA. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [37]; (B2) Schematic of the Tribological tests; The schematic of lubrication mechanisms under water-based lubrication of ZIF-8@PDA. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [86]; (C1) Cooperative lubrication mechanisms of PA-E-Cu(2,6-NDC) and PA-E-Cu(2,6-NDC) in water. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [91]; (C2) Schematic diagram of the lubrication mechanism of using ZPG as a water-based lubricant additive. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [38].

First, the formation and thickening of the lubricating film determine whether a water-based lubrication system can enter a sustainable boundary lubrication state. Microgels and polymer-coated MOFs with core–shell structures provide a clear structural-functional correlation. The outer hydration layer maintains a specific film thickness under shear by trapping water molecules, while the internal framework skeleton provides essential support and collapse resistance, preventing the soft layer from being completely squeezed out. This enhances friction stability and anti-wear performance. Within this mechanism, MOFs/POFs function more as structural units and supporting scaffolds for the lubricating film. Their primary contribution lies in enhancing film-forming capability and effective film thickness, laying the groundwork for further reductions in shear barriers.

Secondly, maintaining the lubricating film is crucial for achieving stable tribological performance in water-based lubrication systems. By enhancing interfacial adhesion and fixation, strongly hydrated components or framework structures are stably distributed across the friction pair surfaces. This reduces the probability of film extrusion and improves lubricating film coverage. When operating in more complex media or environments, changes in ion concentration and interfacial electrical properties can alter the structure of the hydration layer and its wetting/adsorption behavior. This makes the control of macroscopic tribological properties by interfacial anchoring and stable hydration even more critical [93]. Therefore, the low-friction stability of water-based lubrication systems fundamentally depends on the strength of the interface coupling between the lubricating film and the friction pair, as well as its resistance to disturbances.

Once a lubricating film can form and maintain continuity, further friction reduction in water-based lubrication systems depends on whether more stable, low-shear interfaces exist within the lubricating film and whether these interfaces can maintain continuity during shear. The integration of porous framework materials with other layered materials can provide more readily slippable shear planes within the lubricating film. This partially shifts shear forces from complex multi-phase interfaces to the lower-barrier composite lubricating film, thereby achieving lower friction and enhanced lubrication stability. Achieving lower, more stable tribological performance in water-based lubrication systems does not depend solely on the base material’s low-shear properties. It relies more on the synergistic effects of low-shear interface design and continuously regenerative supply. MOFs/POFs enhance lubrication film continuity, shear resistance, and regenerative capacity through hydration, adsorption, and structural reinforcement, enabling shear interfaces to remain more stable under low-barrier lubrication.

In summary, the transition of water-based MOFs/POFs systems from effective friction reduction and wear resistance to engineered water-based superlubricity hinges on a systematic design centered on the lubricating film. Film thickness and formation efficiency are enhanced through hydration layers and framework support; continuous coverage and erosion resistance are improved via interfacial anchoring and stable dispersion; and continuous, renewable shear interfaces are maintained through low-barrier interface construction and structured supply. Therefore, multiple conditions—rapid generation, stable anchoring, continuous coverage, low-barrier shear, and sustainable renewal—are indispensable. Failure in any single aspect may lead to shear-plane migration and compromise the maintenance of a stable, low-friction state.

5. MOFs/POFs in Solid Coating Lubrication Systems

Solid coatings lack a continuously replenished liquid lubricating film during friction, making the friction interface more susceptible to adhesion, plowing, and fatigue spalling. The coupling of factors such as coating structure, tribological properties, and friction conditions predominantly determines lubrication failure. Enhancing the anti-friction, wear resistance, and service stability of coatings and composites through porous frameworks and engineered surface chemistry can achieve structural superlubricity on solid coating interfaces using a limited number of highly ordered two-dimensional porous framework materials.

5.1. Engineering-Scale Friction Reduction and Wear Resistance Laws and Mechanisms

In engineering applications, MOFs/POFs are more commonly incorporated as structured functional units within polymer-based coatings or self-lubricating composite systems such as epoxy resin (EP), polyimide (PI), and polyurethane. They enhance tribological behavior by improving load-bearing capacity, suppressing abrasive wear, and promoting transfer film coverage. Their typical structure and lubrication mechanism are illustrated in Figure 7. Although the coefficient of friction typically remains in the 10−1 range, the reduction in wear, enhanced load-bearing stability, and improved service durability are significantly more pronounced. This represents one of the most clearly defined application areas for MOFs/POFs within solid coating systems.

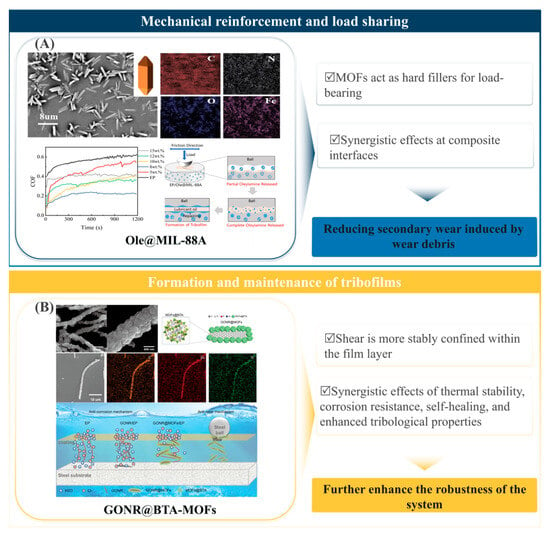

Figure 7.

(A) SEM and EDS images of Ole@MIL-88A and its CoF curves. And the tribological mechanism of EP/Ole@MIL-88A under CSM tribological experiments. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [39]; (B) SEM and EDS images of GONR@BTA-MOFs nanomaterials. Schematic diagram of anti-corrosion and anti-wear mechanism of the EP composite coating. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [40].

MOFs/POFs, as fillers and coating performance-regulating materials, can simultaneously improve friction stability and scratch morphology. In epoxy-based systems, Ole@MIL-88A, as a structured filler, can achieve a minimum friction coefficient of approximately 0.137 and significantly reduce the depth of wear marks and the degree of wear [39]; MOFs incorporated into basalt fiber/epoxy composites reduced the coefficient of friction by approximately 58.82% and the wear rate by about 56.50% [94]; ZIF-8 further demonstrates significant anti-friction and anti-wear improvements when incorporated into EP [95,96]; while synergistic coating systems combining copper-based MOFs with carbon fibers and SiO2 achieve wear rates as low as 10−7 mm3/(N·m) [97]. In these systems, interfacial regulation enables porous framework materials to function not only as hard fillers for load-bearing but also to exert more systematic influence on friction and wear evolution through interfacial synergistic effects within the composite [98].

As research progressed, numerous studies began exploring the use of MOFs/POFs to participate in lubricating film formation and to regulate service stability. This approach aims to drive further friction reduction and enhance long-term stability under more complex operating conditions. When Cu-BTCO is employed in EP systems, the friction coefficient can be reduced to approximately 0.03, attributed to the synergistic effect of active component release during friction in 33.2-nanometer pore gaps and the friction-induced chemical reactions involved in lubricating film formation [99]. Oil@CuBTC demonstrated certain anti-friction and anti-wear effects in PTFE/Basalt composite systems [100]. Concurrently, to address practical service challenges such as corrosion, high temperatures, or cumulative film damage, MOFs/POFs are often synergistically designed with corrosion-resistant, self-healing, or temperature-tolerant structures to achieve greater overall robustness. Corrosion inhibitor-loaded GONR@BTA-MOFs achieve friction reduction while maintaining corrosion resistance in epoxy coatings [40]; the ZIF-67@MXene/PI composite system maintains low friction and significantly reduces wear from room temperature to 300 °C [101]; In higher-load solid friction pairs, the PTFE/PEEK system filled with CuBTCO forms a macroscopic porous structure through the interlocking and bonding of numerous nanoparticles, with pore sizes ranging from 30 to 100 nanometers. At a pressure of 500 N, it exhibits a coefficient of friction of approximately 0.017 and demonstrates extremely low wear rates, indicating the synergistic composite system’s capability to withstand extreme operating conditions [102]. Self-healing polyurethane films synergize with MOF-induced lubrication behavior to reduce friction while mitigating damage accumulation and extending coating lifespan [103]. Additionally, some studies directly employ MOF powders as solid lubricants, demonstrating their ability to reduce friction and suppress wear under certain conditions, though overall friction levels generally remain in the 10−1 range [104,105]. Therefore, low-friction performance at the engineering scale is not a direct output of a single material property but rather the result of the combined effects of coating structure, interfacial chemistry, and environmental conditions. Among these factors, enabling MOFs/POFs to participate in film formation and maintain low-shear interfaces continuously is key to elevating wear resistance into superior, more stable tribological performance.

From a mechanistic perspective, the anti-friction and anti-wear properties of MOFs/POFs in engineering-scale solid coatings primarily depend on three factors. First, mechanical reinforcement and load sharing: the granular and lamellar morphology of porous framework materials enhances the composite’s load-bearing capacity and fatigue resistance against spalling. This reduces localized stress concentration, delays crack initiation and propagation, thereby suppressing coating fragmentation and spalling. It also mitigates plowing and secondary wear, ultimately resulting in smoother wear patterns and significantly reduced wear rates. Second, the formation and maintenance of friction films. Within polymer matrix systems, MOFs/POFs promote the formation of more continuous polymer transfer films or composite transfer films, enabling shear to occur more stably within the film layer. In functionalized, object-loaded systems, friction-induced release of organic components or active agents further contributes to the formation of lower-shear, denser friction-induced chemical films. This shifts the research focus from primarily anti-wear properties toward achieving lower friction and more stable low-friction performance. Under high-temperature or corrosive conditions, these mechanisms are further influenced by thermal stability, interfacial chemical reactions, and film oxidation. Consequently, synergistic improvements in temperature resistance, corrosion resistance, self-healing, and enhanced tribological properties essentially enhance system robustness by ensuring sustained film stability.

Overall, the advantages of MOFs/POFs in engineering-scale solid coating systems primarily manifest as enhanced wear resistance and extended service life. Their lubricating performance is affected by operating conditions involving multiple rough peaks in contact and the continuous generation of wear debris. Shear surfaces tend to migrate between the transfer film and rough peaks, making it difficult for friction to stabilize within the 10−2 or even 10−3 range. Additionally, the lack of liquid self-supply in solid systems limits the film’s ability for continuous coverage and self-repair.

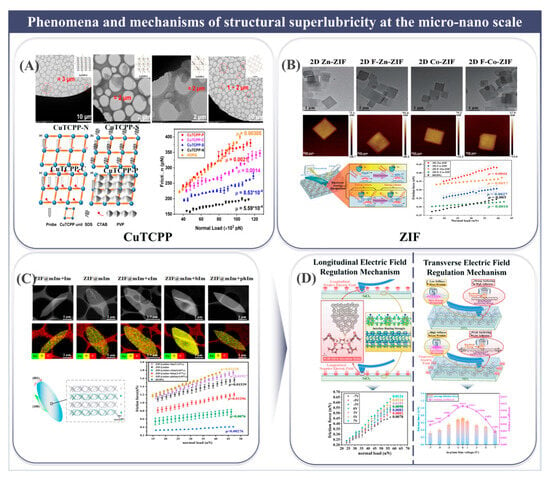

5.2. Superlubricity Phenomena and Mechanisms in Micro-Nano Scale Structures

Unlike engineering-scale approaches focused primarily on enhancing wear resistance and service life, research on two-dimensional MOFs/POFs at the micro- and nano-scale more directly targets structural superlubricity. Multiple reproducible studies have demonstrated that on highly planar, orientation-controlled 2D MOF surfaces or at homogeneous/heterogeneous interfacial junctions, the coefficient of friction can reach the 10−3 range, or even 10−4, exhibiting typical structural superlubricity characteristics. Their representative structures and lubrication mechanisms are illustrated in Figure 8. Lei Liu et al. conducted AFM friction tests on 2D MOFs such as CuTCPP, reporting ultra-low friction at the 10−3 level under micro- and nano-scale contacts [106]. They further achieved stable interlayer superlubricity in homogeneous and heterogeneous junctions of MOFs constructed from highly oriented crystalline films [33]. In two-dimensional lattice-structured MOF systems, friction results of approximately 5.3 × 10−4 have also been observed [19]. When comparing POFs with MOFs under similar testing methods, POFs predominantly exhibit low friction at the 10−3 level. This indicates that different framework structures and interfacial coupling strengths directly influence the undulations of the potential energy surface and shear energy dissipation, thereby determining the lower limit of ultra-low friction [26].

Figure 8.

(A) TEM images of CuTCPP-N, CuTCPP-S, CuTCPP-C, and CuTCPP-P, the sources of resistance generated by the probe on them, and the friction coefficients under different loads. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [106]; (B) AFM images of 2D Zn-ZIFs, F-Zn-ZIFs, Co-ZIFs, and F-Co-ZIFs; schematic diagram of the electronic energy dissipation mechanism during friction, and the variation in the friction force between the probe and 2D ZIFs with the normal load. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [107]; (C) ZIFs dark-field scanning transmission electron microscope images, as well as elemental distribution images, schematic diagrams of the surface and layered structure of ZIFs@mim crystals, and the friction force between the probe and ZIFs. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [32]; (D) The mechanism of two-dimensional ZIFs-8 surface ultra-lubrication under longitudinal and transverse electric fields and the friction curve. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [41].

The key reason superlubricity at the micro- and nano-scale is more readily achievable on two-dimensional MOFs/POFs is their interface conditions, which more closely align with the ideal assumptions for structural superlubricity. These conditions include single- or few-peak contact, atomic-level flatness at the interface, controllable orientation and lattice periodicity, and effective suppression of contamination and wear debris. Under these conditions, shear is more likely to occur at low-barrier interfaces with lattice mismatch or weak coupling, rather than at direct contact points between multi-phase hybrid films or rough peaks. Consequently, friction dissipation can be significantly reduced. The unique advantage of two-dimensional MOFs/POFs lies in the flexible regulation of their lattice period and surface chemistry through metal node and ligand design, providing designable space for interface coupling strength and potential energy surface morphology. When the interface forms weak interactions and effective non-commensurate contacts, the undulations of the potential energy surface are significantly reduced, making the system more likely to enter a low-dissipation state and thereby exhibit structural superlubricity [33,107].

Regarding the repeatability and controllability of ultra-low friction, micro- and nano-scale studies also emphasize the sensitivity of friction to interfacial states. Humidity and molecular adsorption may alter interfacial coupling strength and shear patterns, leading to fluctuations in ultra-low-friction phenomena. Concurrently, factors such as orientation, grain boundaries, and localized defects introduce additional dissipation pathways, thereby raising the friction coefficient from ultralow levels. This explains why many two-dimensional MOF systems exhibit more stable ultralow friction under specific orientations or conditions, while friction increases rapidly upon interface contamination or elevated defect density. External field control provides additional operational means to modulate interfacial coupling or friction dissipation. Following their work on achieving superlubricity in ZIF materials [32], Yuhong Liu’s team further demonstrated that the friction response of two-dimensional ZIF-8 systems can be significantly modulated by controlling electric fields. This indicates that alterations in interfacial electrical properties and adsorption states can directly influence shear barriers and dissipation pathways [41]. Thus, superlubricity at the micro- and nano-scales is an inevitable outcome when the interfacial state is locked into low-barrier pathways. Table 3 summarizes the tribological properties and test conditions of MOFs/POFs after solid coating application, enabling comparison of their performance gains in load-bearing and friction reduction.

Table 3.

Different types of porous framework materials as solid coating lubricant additives.

Table 3.

Different types of porous framework materials as solid coating lubricant additives.

| Additives | Basic Medium | Additive Content (Best*) | Tribometer | Tribological Performance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(2,6-NDC)(DMF) | / | / | Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | CoF: 5.3 × 10−4 | [19] |

| COFs/MOFs | / | / | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | CoF: 0.0034 (COFs); CoF: 5.5 × 10−4 (MOFs) | [26] |

| ZIF@mIm + eIm | / | / | Dimension Icon AFM(Bruker) | CoF: 0.0076 | [32] |

| CuTCPP | / | / | Atomic force microscopy (AFM) | CoF: 0.0013 | [33] |

| Ole@MIL-88A | EP | 10 wt% | Antonpa CSM tribological tester | CoF: 0.137 (↓65.9%); AWSD: 68.4% | [39] |

| GONR@BTA-MOFs | EP | 1.0 wt% | Universal friction tester (UMT) | CoF: 0.08 (↓86.67%); AWSD: 85.51% | [40] |

| 2D ZIF-8 | / | / | Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | CoF: 0.0037–0.0113 (transverse electric field); CoF: 0.0078–0.0124 (longitudinal electric field) | [41] |

| Ni-MOFs | EP | / | Ring blocktester(MM-2HL) | CoF: 0.33 (↓58.82%); AWSD: 56.50% | [94] |

| ZnMOFs | EP/PTFE/PDA | / | Ring blocktester(MM-2HL) | CoF: 0.22 (↓71%); AWSD: 91% | [95] |

| ZIF-8 | Ep | 3.0 wt% | UMT-TriboLab tribometer (UMT-3) | CoF: 0.12 (↓82.1%); AWSD: 93.5% | [96] |

| Cu-BDC | EP/SCF | 6.0 wt% | MRH-1A tribometer | CoF: 0.16 | [97] |

| UiO-66 | PI | 3.0 wt% | Multi-function tribometer (MFT-5000) | AWSD: 83.0% | [98] |

| Cu-BTCO | EP | 5.0 wt% | CETR ultra-functional attrition testing machine | CoF: 0.03; | [99] |

| Oil@CuBTC | PTFE/Basalt | / | Ball-on-disk tribometer (MS-T3001) | CoF: 0.151 (↓20.1%); AWSD: 38.2% | [100] |

| ZIF-67@MXene | PI | / | Tribotester (THT07–135) | CoF: 0.10 | [101] |

| CuBTCO | PTFE/PEEK | 6.0 wt% | Pin-on-disk tester. | CoF: 0.017 (500 N); AWR: 1.1 × 10−9 g/(N·m) | [102] |

| NH2-Ti3C2-ZIF-8 | ZNTSP | 1.0 wt% | Rotating ball-on-disk friction | CoF: 0.101 (↓80.4%); AWSD: 99.4% | [103] |

| COK-47 | / | / | Ball-on-disk linear reciprocating machine (Rtec) | CoF: 0.10; AWR: 2.4 × 10−5 mm3/(N·m) | [104] |

| CuBDC | / | / | Reciprocating tribometer | CoF: 0.20 | [105] |

| CuTCPP-N | / | / | Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | CoF: 5.59 × 10−4 | [106] |

| F-Zn-ZIFs | / | / | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | CoF: 0.001 | [107] |

| FG/BN@UiO-66 | EP | 37.52 wt% | Precision friction and wear testing machine. | CoF: 0.04 (↓69.23%) | [108] |

| C6-C11@Cu-BTC | / | 0.02 g | CSM friction and wear tester | / | [109] |

| Ole@MIL-88D | EP | 15 wt% | Antonpa CSM friction and wear tester | CoF: 0.605 (↓19.1%) | [110] |

6. Outlook

For engineering-applicable superlubricity, MOFs/POFs are better suited as flexible design materials for interface and film formation processes rather than as single additives. Oil-based lubrication systems are constrained by the multi-component heterogeneity of boundary films and dynamic migration at shear surfaces; water-based systems are limited by the thinness and extrusion susceptibility of lubricating films along with environmental sensitivity; while solid coating systems face challenges in maintaining low-barrier interfaces under macroscopically multi-peak contact conditions. Based on this review of oil-, water-, and solid-based lubrication systems, future research should synergistically advance in four directions: constructing superlubricity interfaces, enabling service-induced self-healing, implementing intelligent delivery and regulation, and developing green lubrication solutions.

In the realm of superlubricity, future research must prioritize maintaining the dominance of low-barrier shear interfaces across oil-based, water-based, and solid coating systems. In oil-based lubrication systems, the bottleneck lies in the continuous evolution of boundary lubrication films, which cause shear planes to migrate across multi-phase interfaces; thus, controlled, structured film formation and its sustained renewal require further investigation. For water-based lubrication systems, future efforts should focus on developing continuous, regenerative, and erosion-resistant composite lubricating films that are compatible with diverse friction pairs and environmental conditions. For solid coating systems, achieving superlubricity hinges on maintaining stable low-barrier shear interfaces under real-world operating conditions characterized by macroscopically multi-peak contacts, inevitable contamination, and continuous generation of wear debris. Future efforts should focus on the controlled preparation of large-area, highly oriented two-dimensional coatings at the engineering scale. Through interface designs that resist contamination, prevent debris embedding, and enable sustainable renewal during service, structural superlubricity can be advanced from micro- and nano-scale experimentation to macroscopically applicable solutions.

In self-healing applications, the concurrent failure modes observed in oil-based, water-based, and solid coating systems—namely, lubricant film rupture and shear plane migration—provide clear research directions for future studies on MOFs/POFs. Utilizing pore channels and functionalizable surfaces enables the construction of film precursors or the controlled storage and release of low-shear components. By coupling with the formation processes of physically transferred films and tribochemical films, a dynamic equilibrium can be achieved in which replenishment occurs during friction and repair occurs concurrently with damage. For oil-based and water-based lubrication systems, self-healing extends the coverage time of shearable films and suppresses interfacial drift. For solid coating systems, self-healing becomes the key condition for transforming short-term low friction into long-term stable behavior.

In the field of smart lubrication, a more feasible short-term approach involves encapsulating small amounts of highly efficient film-forming and friction-reducing components within MOFs/POFs as smart containers. These components are released on demand upon load or shear activation, while structured delivery enhances continuous replenishment in contact zones. This stabilizes the lubricating film state and reduces shear plane migration. Future research may explore externally controlled coupling strength and adsorption states at interfaces to achieve flexible regulation of shear barriers and dissipation pathways. Crucially, smart lubrication does not equate to complex lubricants; instead, it aims to achieve more stable low-friction interfaces using fewer materials and greater controllability. The designable channels and surface chemistry offered by MOFs/POFs position them as potentially optimal materials for this direction.