Abstract

The study systematizes the current state of knowledge on the morphological diversity of dispersed-phase particles in the most widely used lubricating greases, encompassing their shape, size, surface structure, and overall geometry. The extensive discussion of the diversity of grease thickener particles is supplemented with their microscopic images. Particular emphasis is placed on the influence of thickener particle morphology, the degree of their aggregation, and interparticle interactions on the rheological, mechanical, and tribological properties of grease formulations. The paper reviews recent advances in investigations of grease microstructure, with special emphasis on imaging techniques—ranging from dark-field imaging, through scanning electron microscopy, to atomic force microscopy—together with a discussion of their advantages and limitations in the assessment of particle morphology. A significant part of the work is devoted to rheological studies, which enable an indirect evaluation of the structural state of grease by analyzing its response to shear and deformation, thereby allowing inferences to be drawn about the micro- and mesostructure of lubricating greases. The historical development of rheological research on lubricating greases is also presented—from simple flow models, through the introduction of the concepts of viscoelasticity and structural rheology, to modern experimental and modeling approaches—highlighting the close relationships between rheological properties and thickener structure, manufacturing processes, composition, and in-service behavior of lubricating greases, particularly in tribological applications. It is indicated that contemporary studies confirm the feasibility of tailoring the microstructure of grease thickeners to specific lubrication conditions, as their characteristics fundamentally determine the rheological and tribological properties of the entire system.

1. Phase Characteristics and Dispersed Structure of Lubricating Greases

Lubricating grease is a polydisperse system in which one phase (the dispersed phase) is distributed within another (the dispersing medium). It is a chemically and physically heterogeneous system. The dispersion medium consists of the base oil (mineral, synthetic, or vegetable), which is regarded as the actual lubricating medium. The dispersed phase in lubricating greases comprises thickeners and, optionally, functional additives in the form of solid lubricants. A key requirement in grease production is that thickener particles exhibit good compatibility with the base oil and relatively small particle sizes. According to Boner [1], individual thickener particles should be smaller than one micrometer in one or two dimensions, with particle asymmetry facilitating the attainment of the desired grease consistency. Thickeners used in lubricating grease production may be of chemical or natural origin. Considering their interaction with the dispersing medium and the thickening mechanism, Velykovsky distinguished three basic groups of thickeners [2]:

- Polymorphic thickeners, whose interaction with the dispersing medium increases as they undergo transformation into high-temperature mesomorphic phases. These are thickeners that do not react with the base oil at room temperature and form systems with a high degree of dispersion at elevated temperatures. This group includes, among others, metal soaps.

- Thickeners that do not exhibit polymorphism but melt at relatively low temperatures. Above their melting point, they form homogeneous solutions with the dispersing medium. This group includes solid hydrocarbons.

- High-temperature-resistant organic and inorganic thickeners that are insoluble in the dispersing medium and do not undergo phase transformations with increasing temperature that would enable their interaction with the dispersing medium. These include highly dispersed silica gels, carbon black, pigments, etc.

According to the classifications proposed by Ostwald [3], most lubricating greases can be treated—depending on the size of the dispersed-phase particles—as heterogeneous, macroscopically dispersed mixtures (suspension systems) or as colloids with a clearly defined interfacial boundary. In cases of varying degrees of particle dispersion, a lubricating grease may exhibit features of both systems (Table 1). It is rare for lubricating greases to contain dispersed thickener particles smaller than 1 nm; among the most common greases with such characteristics are silica gels. The shape of thickener particles, their anisometry (with respect to length and transverse dimensions), as well as their degree of dispersion and volume fraction in the total grease volume have a significant impact on the physical properties of the final grease formulation [4,5,6]. The latter two factors, in particular, determine the ease of formation of various types of energetic bonds between elements of the microstructure.

Table 1.

Characteristic features of colloidal systems, mechanically dispersed systems, and molecular (or limiting) systems (after W. Ostwald) [3].

From a chemical standpoint, most thickener particles are associates [7], i.e., assemblies of identical molecules formed as a result of dipole–dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding [8]. The stability of the resulting microstructure depends on numerous physicochemical factors, including, among others [7,9], the potential energy accumulated within the structure, the mutual attractive forces between individual particles at phase boundaries, the contact time of individual particles per unit volume, electrostatic properties (including surface free energy), and the critical intensity of the association. Thickener aggregates should be characterized by an appropriate size. Aggregates composed of particles smaller than required are unable to form pores sufficiently large to entrap the base oil. Conversely, aggregates built from particles larger than desired may fail to form a sufficient number of interparticle connections to ensure a stable structure. Particle dimensions affect such grease properties as dynamic viscosity and syneresis. Therefore, a key issue is the determination of parameters governing in situ particle nucleation and the rate of their growth during lubricating grease production.

2. Morphology and Particle Size of Selected Soap Thickeners

The microstructure of lubricating greases thickened with lithium, calcium, and sodium soaps can be compared to a sponge impregnated with lubricating oil. It constitutes a three-dimensional, elastic, and coherent network of interconnected particles (flow units), referred to in the literature as flocs, fibers, floccules, ribbons, or filaments [1,10,11]. These particles are characterized by strong mutual interactions. As a result, a relatively small increase in thickener content leads to a significant increase in the structural viscosity of the grease. The highly cross-linked structure ensures, in most cases, very good mechanical stability [12] and excellent thixotropic properties [13,14,15]. The microstructure of aluminum-based greases differs in morphology from that of other soap thickeners. Aluminum soap aggregates often form spherical structures resembling yarn, with more or less distinctly defined edges. Microscopic images reveal that these are strongly twisted fibers. The literature also reports that the structure of aluminum soap thickeners may be formed by catenated particles occurring as loosely cross-linked, short fibers [16]. Fine associates of aluminum soap impart characteristic mechanical properties to aluminum greases, such as low resistance to shear stress and, consequently, higher pumpability.

Soap thickener particles may vary in size. In fresh soap greases that have not been subjected to intensive service in frictional contacts, thickener particles typically do not exceed 100 μm in length, with diameters ranging from 0.1 μm to 1 μm [10,17,18,19]. Sodium soap particles are characterized by the greatest length. The average size of individual aluminum stearate associates is approximately 0.1 μm. During shear of soap greases in tribological contacts, the length of individual particles may be reduced by more than an order of magnitude [1]. In the case of the most common soap greases, i.e., lithium greases operated in rolling bearings, the length of individual particles is usually reduced by about 30%. Under the action of intense shear forces, these particles may also undergo thinning, as confirmed by imaging studies [20]. Shortened nanoparticles may form larger agglomerates or clusters as a result of mutual adhesion. Table 2 summarizes the average dimensions of soap thickener particles together with descriptions of their microscopic images.

Table 2.

Microstructure of soap-based greases as a function of thickener type [18].

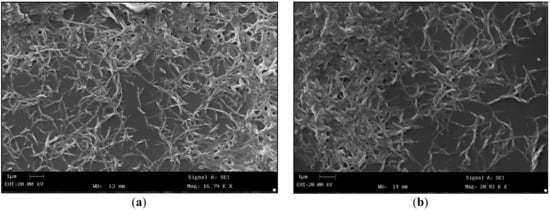

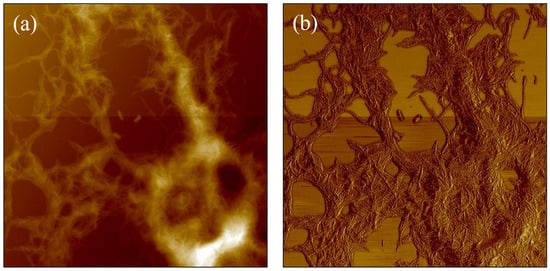

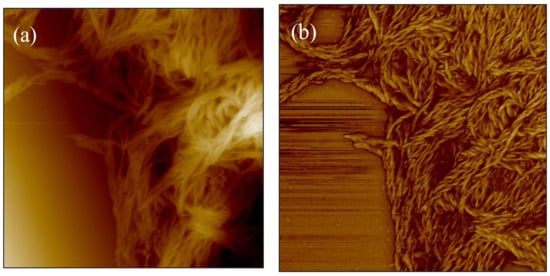

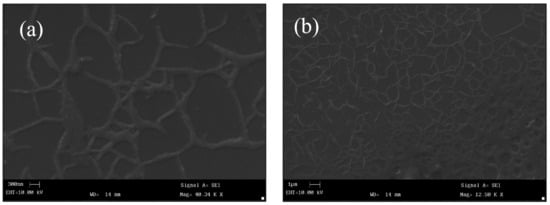

As mentioned earlier, the final skeleton of the microstructure of soap thickeners—formed within the dispersing medium—develops in situ during the crystallization of soap particles and/or through nucleation, i.e., the formation of crystallite nuclei and their subsequent growth [1]. The shape of thickener particles and the topography of their surfaces may vary depending on the type of soap used and the size of the aggregates. The microstructural morphology may also be influenced by the base oil employed in grease production [21]. The use of mineral, paraffinic, or naphthenic oils does not significantly affect fiber length, width, or morphology. In contrast, the application of synthetic polyalphaolefin oils results in a markedly less compact structure characterized by higher porosity. The use of polyglycol oils, in turn, leads to the formation of a hard, very dense structure with a small number of pores. In this case, the weakly cross-linked structure hinders the retention of the base oil within the soap thickener matrix, simultaneously causing increased penetration and reduced mechanical stability of the grease. Thickener particle morphology is also affected by particle size. Particles exceeding 1 μm in size exhibit a rough structure and resemble twisted ropes, whereas crystallites of colloidal dimensions are distinctly smoother and less twisted [17]. Analysis of microscopic images of lithium, sodium, and calcium thickeners also reveals clear differences in the surface structure of flocs [7,22]. Lithium soap fibers resemble braided hair in shape. It is rare for lithium thickener particles to occur as single, thin fibers; more commonly, they appear in the form of double or triple helices. Calcium soap particles are more rugged than lithium and sodium soap particles, regardless of their length [1]. These particles are often formed into small rings. Aluminum soap associates consist largely of very short, thin, smooth, and velvety, entangled fibers. Aluminum greases pose significant production challenges due to the loss of benzoic acid as a result of sublimation during the grease manufacturing process. Consequently, the microstructural shape and structural stability of aluminum greases may vary considerably, even under similar production conditions. Some researchers have observed that associated aluminum soap molecules, when viewed under a microscope, exhibit a distinctly lighter color than other soap thickeners and may be partially transparent [23]. The microstructure of aluminum greases produced with naphthenic oils is soft, whereas that obtained with paraffinic oils is more compact, harder, and more homogeneous [23]. Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 present representative micrographs of the microstructure of the most commonly used soap thickeners, recorded using SEM and AFM.

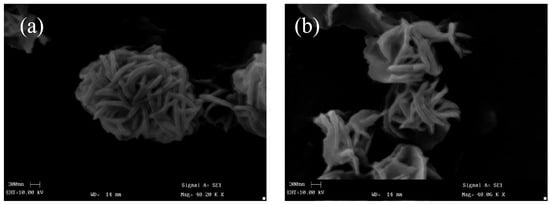

Figure 1.

SEM images of the microstructure of a lithium grease thickener at magnifications of (a) 16,790× and (b) 20,030× (from the author’s own collection, M. Paszkowski).

Figure 2.

AFM images of the microstructure of a lithium grease thickener over a 10 × 10 μm2 area. AFM operating modes: (a) topographic, (b) phase (from the author’s own collection, M. Paszkowski).

Figure 3.

AFM images of the microstructure of a lithium grease thickener over a 2 × 2 μm2 area. AFM operating modes: (a) topographic, (b) phase (from the author’s own collection, M. Paszkowski).

Figure 4.

SEM images of the microstructure of a calcium grease thickener at magnifications of (a) 40,340× and (b) 12,500× (from the author’s own collection, M. Paszkowski).

Figure 5.

SEM images of the microstructure of an aluminum grease thickener at magnifications of (a) 40,200× and (b) 40,060× (from the author’s own collection, M. Paszkowski).

At present, there is a growing tendency to produce grease formulations containing thickener particles of different sizes. Lubricating greases exhibiting a relatively high degree of homogenization and a diversified thickener particle size distribution—at the boundary between mechanical and colloidal dispersion—are characterized by improved tribological and rheological properties. This is particularly true for lithium greases [1]. Excessive fragmentation of particles, however, may adversely affect the lubricating performance of grease formulations. In greases with a very high degree of dispersion, soap thickeners do not possess sufficient ability to form spatial, three-dimensional structures through physical interactions and therefore exhibit reduced thickening efficiency. In such structures, the occurrence of mechanical occlusion of the base oil within the free spaces between crystallites is hindered [1,24]. Conversely, excessively long thickener particles lead to an excessive increase in grease consistency and a marked deterioration of its ability to dissipate heat via convection. They also promote easier phase separation of the grease in lubrication systems and tribological contacts. In fresh grease formulations, the degree of thickener particle dispersion is closely related to the manufacturing process, in particular to the thickener crystallization temperature, cooling rate, mixing speed, homogenization time, the distance between homogenizer plates, the presence and concentration of surfactants, and other process parameters [25]. Literature data [1] indicate that the lower the temperature during soap grease production, the smaller the average particle dimensions. Both nucleation and the growth of associates become increasingly intense with rising process temperature up to a critical point. Above this critical temperature, associate growth accelerates, while nucleation decreases. By appropriate control of the process temperature, it is therefore possible to regulate both the number of particles and their dimensions, and consequently to obtain the desired physicochemical properties of the final grease formulation. The size of thickener particles is also determined by their mass fraction in the grease composition. As saturation increases, the intensity of particle growth also increases, particularly at the initial stage of grease production. This is attributable to diffusion phenomena. The dimensions of microstructural particles may also change during grease service, as mentioned earlier. It should be emphasized, however, that the degree of particle dispersion is strongly dependent on the conditions and mode of shear to which the grease is subjected.

3. Morphology and Particle Size of Selected Non-Soap Thickeners

Non-soap thickener particles are significantly smaller in size compared to soap thickeners. Isometric aggregates of bentonite clay and mica have widths of approximately 0.5 μm and thicknesses of about 0.1 μm [10,18]. In the case of silica gel aggregates, the average particle diameter ranges from 7 to 40 nm [10]. For inorganic thickeners, the grease microstructure is typically formed by numerous individual aggregates, referred to in the literature as open card-house structures [26], such as bentonite, mica, or vermiculite. These particles exhibit a skeletal structure resembling irregular, torn-edged, twisted flakes or flat plates stacked one on top of another [27]. A SEM image of bentonite thickener structure is shown in Figure 6. The aggregates in this image exhibit significantly weaker mutual interactions than those observed in soap-based greases. Consequently, under light loading, the structural viscosity of bentonite greases decreases relatively quickly [28]. The ability of anisometric bentonite particles in the form of plate-like crystals to form three-dimensional structures, according to Sonntag [29], is attributed to the asymmetry of the force field around them. The surface charge density varies between small edges and larger surfaces; in some cases, these regions may even carry opposite charges. This generates a dipole within the particle, and the presence of such dipoles facilitates the formation of complex spatial structures. According to Boner [1], the most optimal configuration of bentonite thickener particles in a grease formulation is a stack of plates arranged such that the base oil can contact the maximum surface area of the plates, thereby achieving the highest thickening efficiency. In some highly dispersed inorganic thickeners, such as silica gels, particles may have a spherical shape. Individual particles, primarily composed of polymerized SiO2 molecules, form shapeless chains mainly through intermolecular interactions. These particles contain nonpolar siloxane groups as well as polar silanol groups. The silanol groups enable the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds and determine the geometry of the three-dimensional structure. Base oil is entrapped within the voids of the porous silica structure primarily through capillary forces, similar to the mechanism observed with soap thickeners, and to a lesser extent through adsorption.

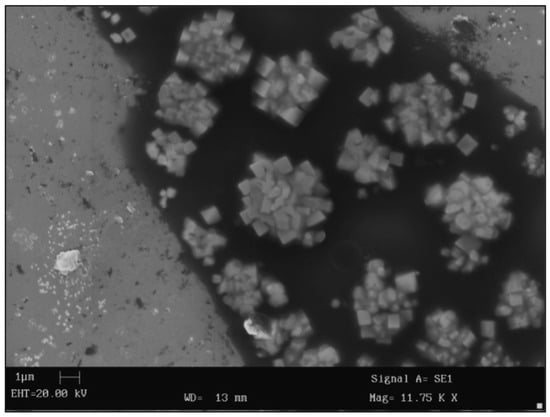

Figure 6.

SEM images of the microstructure of bentonite clay, serving as a thickening agent in bentonite grease at magnifications of 11,750× (from the author’s own collection, M. Paszkowski).

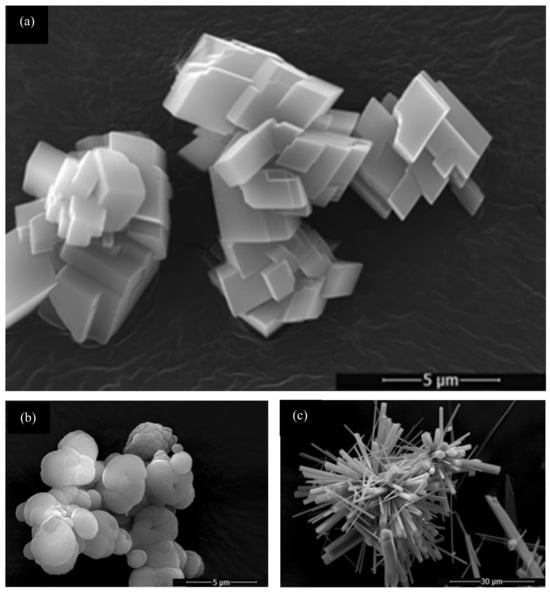

An interesting structural example of a grease is that thickened with calcium sulfonate. Calcium sulfonate greases are not classified as conventional soap-based greases; they belong to the category of complex (non-soap) greases, despite containing calcium. The dispersed phase in this case consists of particles of overbased calcium sulfonate, comprising a core of amorphous calcium carbonate surrounded by polar surfactant molecules. The hydrophobic chains of the surfactant stabilize the colloidal particle within the base oil [30]. Overbased calcium sulfonates act as surface-active agents (detergents), which, through their polar sulfonate groups and hydrophobic alkyl tails, stabilize the micellar system. The micellar structure itself forms due to interactions between the sulfonate group and the base oil, resulting in a stable dispersion of calcium carbonate particles. Calcium carbonate particles are typically spherical or nearly spherical when in the amorphous form. After thermal or chemical treatment, these particles may transform into crystalline forms, such as calcite, vaterite, or aragonite, which exhibit more defined shapes, such as rhombohedral or rhombic geometries (Figure 7). The size of overbased calcium sulfonate particles in greases ranges from 1.5 to 10 nm [31], although some studies report sizes up to 500 nm [32]. Accordingly, sulfonate grease constitutes a colloidal system according to the Ostwald classification. Fine particles provide a more homogeneous matrix and enhance grease stability. However, they do not possess thickening properties as effective as those of soaps, which necessitates a higher mass fraction of thickener in the grease compared to traditional soap-based greases. A notable feature of the sulfonate thickener is its capacity to incorporate large amounts of water. The hydrophilic groups within the calcium sulfonate capture and retain water molecules, resulting in excellent water washout resistance and outstanding anti-corrosion properties. Interestingly, water incorporation also increases the structural viscosity and mechanical stability of the grease. Calcium carbonate within micellar systems can occur in different forms: amorphous or crystalline (calcite, vaterite, aragonite). Depending on the conditions of calcium carbonate conversion, it adopts different crystallographic forms, which in turn affect the grease’s behavior under shear stress. In calcium sulfonate-thickened greases, polymorphism is observed—the calcium carbonate exists in multiple forms, each characterized by a distinct crystallographic arrangement and specific properties. The crystallographic form of calcium carbonate determines the grease’s stability, load-carrying capacity, and thermal properties. Amorphous forms, commonly present at early stages of grease formulation, are more soluble and reactive than crystalline forms. They are also thermodynamically less stable and can transform into crystalline forms under specific conditions, such as heat or pressure. As temperature rises and reactions progress, the crystalline form of the constituents decomposes, leaving primarily solid sulfonates, which transform from amorphous calcium carbonate into aragonite or calcite, significantly influencing grease longevity [33]. Characterization of crystalline forms in calcium sulfonate-based greases involves identifying the type, morphology, size, and stability of calcium carbonate particles, which markedly impact grease performance. Identification also includes analyzing structural, spectral, and physical characteristics using appropriate analytical methods. Calcium carbonate in this context occurs in polymorphic forms: mainly calcite and aragonite, and occasionally vaterite, each with unique properties. The most stable crystalline form is trigonal calcite, which provides excellent load and wear resistance due to its crystal structure. Less stable than calcite, yet commonly present in greases produced under higher pressures and temperatures, is rhombohedral aragonite; its needle-like structure can enhance the grease film’s resistance. Hexagonal vaterite is the least stable form and adversely affects grease properties. It may temporarily improve grease performance but usually transforms into calcite or aragonite over time. This transformation generally occurs due to instability under standard conditions and can take minutes to hours, depending on the environment. Factors such as temperature, mixing rate, supersaturation, ionic strength, pH, and additives influence the conversion rate [34]. Crystalline calcite consists of thin layers or sheets of calcium carbonate with a high surface-to-volume ratio. It exhibits a large covering surface, forming ferrous-layer structures [35].

Figure 7.

SEM images of the structures of (a) calcite, (b) aragonite, and (c) vaterite [36].

Polymorphic structures of calcium carbonate can be analyzed using XRD [37], IR spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy [37,38]. The literature reports characteristic absorption bands assigned to each polymorphic form [39]. FTIR spectroscopy allows the distinction of vaterite from other polymorphic forms based on its unique vibrational modes. Literature also indicates that in the IR spectra of calcium sulfonate greases—depending on their method of preparation—absorption bands corresponding to vaterite (1460, 1410, 1045, 876, and 720 cm−1) and calcite (1410, 883, and 714 cm−1) can be observed. The spectrum of amorphous calcium carbonate is characterized by absorption bands at 1494, 1460, 1045, 863, and 863 cm−1 [40].

4. Physicochemical Interactions Responsible for Microstructure Formation and Wall Effects

The mechanical and structural properties of the thickener determine the elastic component of lubricating greases. Under normal conditions, the base oil is gradually released from the microstructure in small amounts over the service life of the lubricated tribological component. It is estimated that approximately 70% of the base oil is occluded within the free spaces of the thickener network through capillary and van der Waals forces [41,42]. The bonds retaining the oil reservoirs within the microstructure are weak, leading to partial oil release under the influence of temperature and pressure present in the bearing. As the pores containing occluded oil decrease in size, increasingly higher pressure is required for oil expulsion. A portion of the base oil occluded in the free spaces of the network is also released during the syneresis of greases, which mainly occurs during storage. This process involves the shrinkage of the microstructure and the formation of a denser packing of thickener particles. The remaining 30% of the base oil in the grease is associated with the thickener particles via intermolecular attractive forces. These bonds are strong enough that the release of this portion of oil from the grease is practically impossible without solvent extraction [42]. In cases where the thickener does not sufficiently bind with the base oil, special additives are used to enhance the mechanical strength of the microstructure and to modify the free energy at the thickener–base oil interface [42].

The microstructure of lubricating greases is formed by thickener particles linked through dipole–dipole interactions, London van der Waals forces, electrostatic repulsion (particularly important when the dispersed-phase particles are anisometric), steric interactions, and ionic bonds [43]. However, hydrogen bonding plays a predominant role in the formation of the microstructure for most thickeners [13,15,44], particularly in soap-based greases. Chemically, soap thickener particles are associates [7], i.e., assemblies of identical molecules formed through physicochemical interactions. Individual thickener particles behave similarly to the molecules that constitute them. The process of microstructure formation is also influenced by surface energy. Atoms and molecules at the phase boundary of thickener aggregates are energetically richer than identical atoms and molecules in the interior of the phase. In macroscopic aggregates, the contribution of these surface atoms and molecules to the total system energy is negligible. This is different for small particles, where the number of surface atoms and molecules is comparable to that in the interior of the particle [45]. Interfacial energy can be modified through the use of surfactants. Some lubricating greases exhibit structural stability only in the presence of surface-active substances.

A typical soap has a structure composed of a long, nonpolar hydrocarbon chain bearing a hydroxyl group and a polar carbonyl group containing a metal. The cations and anions in soaps significantly influence the tribological and rheological properties of soap-based greases [46]. Metal cations (Me) determine the thickening ability of the soap and the water resistance of the grease, as well as affecting the dropping point. The chain length of the fatty acid residue anion (R-COO−), usually consisting of 18 carbon atoms, governs the solubility of the soap in the base oil and the oxidation resistance of the grease. Thickener particles in soap-based greases are not easily fragmented. Intensive microstructure breakdown occurs only under very high shear stresses, with elevated temperature acting as a catalyst for this process. As mentioned earlier, in most cases, the microstructure of soap-based greases exhibits characteristics of a mechanically fragmented system, rather than a colloidal one. Individual soap flocs do not exhibit Brownian motion, i.e., intense, random vibrational movements that could further disturb particle orientation during grease flow.

Interesting changes in the microstructure of grease thickeners can be observed during shear, as well as in the stress-relaxation phase following the cessation of shearing. These changes are particularly evident in greases thickened with soaps. Analysis of differential ATR-FTIR spectra of fresh and used lithium greases revealed the disruption of hydrogen bonds connecting the hydroxyl groups of adjacent soap fibers [13]. This is accompanied by a pronounced decrease in the intensity of bands corresponding to the vibrations of CH2 and CH3 groups from lithium 12-hydroxystearate molecules, indicating the association of hydrocarbon chains of individual fibers. Conformational changes and the accompanying orientation of particle aggregates in the flow direction cause a very slow decrease in the structural viscosity of lithium grease during its operation. As a result, lithium greases exhibit relatively high mechanical stability. The shear stresses decrease gradually as both the intensity and duration of shearing increase. During stress relaxation, the number of hydrogen bonds broken during shearing increases again [13,15,44]. Additionally, a reduction in the number of COOH groups was observed, indicating changes in the chain structure of flocs. By analyzing the absorbance of selected vibrational bands of lithium 12-hydroxystearate molecules as a function of stress-relaxation time, it can be seen that the most significant microstructural changes occur within the first four hours after shear cessation. Rapid strengthening of the microstructure during stress relaxation (the grease resolidification process) is also confirmed by measurements of changes in cohesive energy density recorded using a rotational rheometer. Rheological studies show a clear, gradual return to the elastic properties of the grease prior to shearing [15]. The phenomenon of microstructure strengthening during stress relaxation has substantial practical significance. Resolidification of the grease significantly slows down its leakage, for example from an unsealed tribological assembly, and provides better protection of lubricated friction surfaces from contaminants present in the operating environment. The isothermal decrease in structural viscosity during shearing, followed by an increase in structural viscosity and resolidification under the same pressure and temperature conditions after shearing, is referred to as thixotropy [47]. The term originates from the Greek words thíxis (stirring, shaking) and trépo (turning, changing), and was proposed by Peterfi [48] (originally as thixotropy [49]). Thixotropy of lubricating greases has been the subject of numerous studies [14,24,50,51,52]. The course of changes within the microstructure of the thickener during shearing and stress relaxation is somewhat different in the case of non-soap thickeners, such as greases thickened with bentonite clay. As mentioned earlier, bentonite greases have a structure composed of platelet aggregates with significantly weaker mutual interactions compared to lithium grease. The physicochemical bonds between individual particles are much weaker, and therefore even a small applied shear force causes the structural viscosity of bentonite grease to decrease very rapidly. Bentonite greases exhibit a somewhat lower ability to rebuild their microstructure compared to lithium greases [53,54]. Kozdrach in study [55] demonstrated that bentonite grease subjected to intense mechanical and thermal loads undergoes pronounced microstructural disintegration. Raman spectral analysis showed that the observed changes primarily affect montmorillonite. After intensive shearing of the grease, the appearance of additional peaks in the 2080–2090 cm−1 range, attributed to modified Si–O stretching vibrations, indicates a disturbance in the ordering of the clay’s layered structure. These changes are structural in nature rather than unequivocally chemical degradation. Kozdrach also notes that intensive shearing may promote interactions between the base oil and montmorillonite, which may influence the character of the observed Si–O vibrations.

The microstructure of soap-based greases, resulting from the anisometric shape of thickener particles (with respect to their length and transverse dimensions) and the presence of reactive centers at the ends of their associates, leads to specific interactions with material surfaces, such as structural elements of tribological assemblies or components of centralized lubrication systems. Near a solid surface, distinct near-wall regions can be identified within the grease. First, an adsorbed thickener layer is formed directly at the surface as a result of aggregation and adhesion of thickener particles to the material wall. Adjacent to this layer, a thickener-depleted layer develops, characterized by a significantly reduced concentration of thickener and, consequently, much lower structural viscosity. The rheological behavior of this depleted region approaches that of a Newtonian liquid, i.e., the base oil. The formation of the thickener-depleted layer is associated with the diffusion and migration of thickener particles along the surface, accompanied by partial extraction of associates from the bulk grease. As a result, the structure in this near-wall region becomes diluted and less cross-linked, which promotes slip of the grease at the wall and leads to a reduction in flow resistance. The occurrence of such a thickener-depleted near-wall region during suspension flow is commonly referred to in the literature as the wall effect or wall slip effect. In axisymmetric conduits, this phenomenon is also frequently described as the Segré–Silberberg effect or sigma effect, first reported in detail in 1962. The earliest references to near-wall layer formation in lubricating greases can be found in the works of Bramhal and Hutton [56]. The phenomenon was subsequently investigated by Vinogradov and co-workers [57,58], who experimentally analyzed wall slip in lithium and calcium greases. Czarny [59] attempted to explain the formation of the near-wall layers in the contact zone between grease and the walls of lubrication systems as well as the working surfaces of tribological assemblies, demonstrating that their development depends primarily on the material of the contacting surface. Barnes [60] identified the conditions under which the formation of the thickener-depleted layer in lubricating greases is most pronounced, emphasizing the role of large dispersed-phase particles, smooth wall surfaces, and small conduit cross-sections. Balan and Franco [61] reported results on the influence of surface geometry on near-wall layer formation, observing material-dependent differences for smooth surfaces at grease shear rates below 10−3 s−1. Biernacki [62] investigated the thickness of thickener-depleted layers in complex lithium and bentonite greases between two parallel approaching plates made of metals and plastics. These experiments showed that lithium grease formed a depleted layer approximately 65 µm thick near a copper plate, whereas no such layer was observed for bentonite grease. The formation of adsorbed and depleted near-wall layers is also influenced by the surface free energy of the contacting material. Metallic surfaces, which typically exhibit higher surface free energy than polymers, more readily promote the development of thickener-depleted layers [63]. Temperature plays an additional role, acting as a catalyst for the process [63]. The wall slip effect may also occur in non-contacting seals, such as those used in structural components of mining conveyor pulleys. During prolonged operation, grease separation and leakage from seal gaps can arise due to centrifugal forces combined with wall slip phenomena. Studies [64,65] indicate that this behavior may be associated with energetic interactions between thickener particles and the seal surface, facilitating base oil flow. Wall slip has also been observed during grease shearing in axial and radial labyrinth seal gaps, investigated using µPIV [66]. Recent studies employing optical interferometry have confirmed that wall slip plays a significant role in the lubrication of tribological assemblies. In particular, this phenomenon may occur under EHL conditions, leading to pressure and flow heterogeneities within the lubrication gap. Accounting for wall slip effects in EHL models is therefore essential for obtaining more accurate predictions of lubrication performance and for understanding mechanisms that may lead to failure [67].

5. Methods for Imaging the Microstructure of Lubricating Greases

For many decades, direct observation of the microstructure of thickeners in lubricating greases was technically impossible due to the lack of analytical imaging instruments with sufficiently high resolution. It was not until 1936 that images of thickener microstructure were obtained for the first time, using an optical observation technique known as dark-field microscopy, which relies on lateral illumination of the specimen with scattered light emerging from a condenser [17]. This imaging technique made it possible to observe the shape and size of sodium soap thickener fibers in lubricating greases used in automotive gear transmissions. At that time, it was observed for the first time that shear stresses in lubricating greases can cause fragmentation, thinning, and changes in the texture of thickener particles [23]. In later years, similar observations were also carried out using polarized light microscopy [68]. The advent of electron microscopy significantly expanded knowledge of thickener microstructure. Farrington and Birdsall, in their work [69], published the first images of soap particles in commercial greases obtained using an electron microscope. In subsequent years, the application of SEM for this type of research became something of a standard [4,10,70,71,72,73]. Numerous SEM images of the microstructure of lubricating grease thickeners (including solid lubricant additives used in greases) can be found in references [28,74]. With the introduction of this new imaging method, sample preparation for SEM analysis required considerably more time and specialized knowledge in specimen preparation. The most common method of preparing grease samples for SEM involves preliminary treatment consisting, among other steps, of washing out the base oil from the thickener network using solvents (mainly n-hexane). This is necessary because the base oil is volatile, which prevents the use of imaging techniques requiring high vacuum conditions. Unfortunately, this stage causes significant disturbance of the grease microstructure [72,75,76]. The sample prepared on a microscope slide is then placed in a vacuum extractor for at least 2 h to ensure complete removal of the solvent and base oil. The specimen is subsequently mounted on an SEM stub, usually using carbon tape. The prepared sample is then subjected to a temperature of 35 °C for several hours in a vacuum oven. After completion of this procedure, the specimen is analyzed by SEM. In later years, other, significantly less invasive imaging techniques were employed, contributing to improved classification of dispersed-phase particles in both soap-based and non-soap greases, taking into account their size, shape, and texture. These techniques included TEM [20,77,78], cryo-TEM [73], and AFM [70,71,72,73,74], which do not require coating the analyzed specimen with a metal layer (gold or carbon). In ref. [13], numerous images of lithium greases obtained using atomic force microscopy operating in tapping mode were presented. The resulting topographical and phase images of the lithium thickener microstructure exhibited much higher detail than those obtained using previously described methods. In ref. [79], degradation of lubricating grease structure under internal friction induced by shear stresses was analyzed using optical microscopy, SEM, and AFM techniques. It was emphasized that the method of sample preparation is of key importance, as it strongly influences the observed grease structure. Optical microscopy proved useful for assessing macrostructural changes, whereas SEM and AFM enabled detailed analysis of grease microstructure. It was highlighted that during SEM sample preparation, due to the necessary extraction of the base oil, the structural skeleton may become more agglomerated and collapsed. In contrast, AFM sample preparation does not cause such changes, and the resulting images contain significantly more relevant details. To obtain high-quality AFM images, grease samples require appropriate preliminary preparation, as also emphasized by Roman et al. [76]. Sample preparation for detailed AFM observations is one of the most difficult and critical stages in microstructural analysis. This process differs substantially from SEM sample preparation. The best results are obtained by heating the sample to a temperature not exceeding the grease dropping point in order to achieve a smooth surface that ensures good resolution. Depending on the grease under investigation, various time–temperature combinations are applied (100–240 °C for 5–30 s). The samples are then cooled to room temperature for several minutes and subsequently examined.

6. Application of Rheometric Measurements to the Evaluation of Lubricating Grease Structure

The first publications on rheological studies of lubricating greases appeared in the 1940s. However, some of the most important works were published several years later. In 1958, Sisco [80] proposed a simple formula to describe the flow behavior of greases. The results obtained by Sisco contributed to the development of more advanced analyses of grease flow in structural components of dispensing systems and also served as a reference for later models and studies. To this day, the Sisco model is used to analyze flow resistance of greases in pipelines, as it accounts for structural changes occurring in grease during flow. By the mid-20th century, the concept of structural rheology had already emerged, which proved to be particularly important in the study of lubricating greases. In 1959, Forster and Kolfenbach [81] presented one of the first attempts to formally measure and describe the viscoelastic properties of lubricating greases. Their studies employed oscillatory rheological tests. Earlier research on lubricating greases had focused largely on flow properties, consistency, and frictional resistance. For the first time, the concepts of the elastic (storage) modulus, describing the elastic properties of grease arising from the structure of the thickener, and the viscous (loss) modulus, describing viscous behavior, were introduced. Seven years later, Criddle [82] demonstrated that at low stress levels, lubricating greases behave as linear viscoelastic materials, while above the yield stress they exhibit nonlinear behavior. Both the elastic and viscous moduli decreased with increasing strain amplitude. Toward the end of the 1960s, comprehensive works by Hutton [83] and Barnett [84] appeared, summarizing postwar achievements in the rheology of lubricants. At the beginning of the 1970s, models of grease structure existed only in a broad, descriptive form. It was known that the thickener structure consisted of solid particles that could exhibit elongated shapes (soap-based greases) or more spherical shapes (silica-based greases). These particles aggregated into structures and superstructures, as confirmed by optical microscopy images, which were relatively detailed for that period. The development of rotational rheometers in the early 1970s, together with the introduction of air bearing systems (the first such rheometer being designed by Davis, Deer, and Warburton from the London School of Pharmacy), contributed significantly to progress in the evaluation of mechanical properties and interparticle interactions within the internal structure of lubricating greases. This period also marked a gradual shift away from capillary rheometers, which were burdened with numerous limitations. In 1976, one of the most important publications on lubricating greases appeared [1]. In this work, Boner presented a comprehensive set of information on the structure and rheological properties of lubricating greases. He skillfully combined theoretical aspects (grease composition and thickener structure) with practical considerations related to application and operation. Boner repeatedly emphasized the crucial role of the dispersed phase—namely particle shape, size, size distribution, and the ability to aggregate and agglomerate—in determining the performance properties of lubricating greases. The 1980s saw extensive research by Froĭshteter and his research group, including a monograph (later published in English) [7], which effectively summarized their experimental work on the rheological and thermophysical properties of lubricating greases. The authors discussed the most reasonable and commonly used experimental procedures for evaluating the rheological and structural properties of widely used lubricating greases. The importance of proper selection of measurement geometry and testing procedures in rheological characterization of lubricating greases was also emphasized by Mas and Magnin [24]. They drew attention to measurement errors arising from wall slip at the measuring spindle and phase separation of greases within the measurement gap during rheological tests. In ref. [85], Czarny investigated the phenomenon of thixotropy in lubricating greases, highlighting the importance of microstructural recovery during pauses between grease dosing cycles in lubrication systems. His studies employed a rheometer operating in a coaxial cylinder (Couette) configuration. Czarny analyzed the increase in dynamic viscosity of lubricating greases resulting from structural rebuilding and reorganization between successive shear cycles in the rheometer head. He observed that soap-based grease particles exhibit high reactivity and a strong tendency to form larger structures and aggregates. In 1996, Mas and Magnin published a study [86] demonstrating how the operation of lithium and calcium complex greases in rolling bearings affects changes in thickener structure. This work was among the most important studies correlating the rheological properties of grease formulations and structural transformations with the lubrication mechanisms of rolling bearings. The late 1990s brought notable contributions by Kuhn, who investigated the energetic aspects of lubricating grease flow, taking into account structural changes induced by shear forces [87,88]. Shear energy and the associated entropy became the foundation of engineering and thermodynamic models used to assess thickener structure degradation during grease operation in friction nodes. The 21st century has witnessed further advances in rheometric studies of lubricating grease thickener structures. Rheometers capable of operating in controlled-strain and controlled-stress modes have become increasingly widespread, enabling a broader range of testing options, particularly for evaluating grease structure. Numerous studies have addressed the influence of thickener concentration on the rheological properties of grease formulations. In ref. [6], Yeong et al. presented results of studies on lithium 12-hydroxystearate–thickened greases formulated with mineral base oils. They observed that at thickener concentrations exceeding 5 vol%, the storage modulus (G′) was greater than the loss modulus (G″), with both moduli increasing as thickener concentration increased. Below this critical concentration, G″ exceeded G′. The authors also conducted creep tests under controlled stress and applied scaling theory to describe structural changes, treating the gel network as an assembly of flocs regarded as densely packed fractal objects. Yeong et al. concluded that grease gel structure formation may proceed via a chemically limited aggregation mechanism. Once again, the importance of appropriate testing procedures, measurement geometry, and the surface characteristics of the measuring spindle was emphasized. In these studies, sandblasted plates were used to reduce grease wall slip during rheological measurements. Conrad et al. [89] also investigated the influence of thickener concentration, focusing on the processes of crystallization, melting, and vitrification of lubricating greases formulated with three different types of base oils (Groups I–III) using rheological and thermoanalytical measurements. Their results highlighted the critical importance of rheological considerations in the manufacturing technology of lubricating greases. The same authors, in ref. [90], correlated rheological measurements of greases with varying thickener concentrations with imaging studies (SEM, MPT), successfully applying theoretical models primarily used in the rheology of molten polymers. Using these models, they determined geometrical characteristics of the network structure, such as the spatial organization of interconnected particles. Delgado et al. [4] emphasized that the rheological and structural properties of lubricating greases can be controlled by adjusting their formulation components. The greases were characterized rheologically using SAOS tests. They found that the microstructural framework—including particle size and shape of the dispersed phase—depends not only on thickener concentration but also on the viscosity of the base oil. The strong influence of base oil type on the morphology of lithium thickener particles in lubricating greases was also observed by Salomonsson et al. [73]. Xu et al., based on extensive experimental studies, concluded that using base oils containing ester linkages and aromatic rings in lithium grease production enhances the strength of the thickener microstructure, particularly in greases with a low degree of fiber entanglement [91]. The manufacturing process of lubricating greases plays a crucial role in determining the three-dimensional structure of the thickener network and particle morphology, as reported by Delgado et al. [92]. Soap-based greases, especially lithium soaps, form a highly ordered system, based on the formation of a three-dimensional network during production, resulting from the presence of metallic soap crystallites. The particle nucleation process is highly dependent on production parameters, particularly the cooling rate. The use of oscillatory rheological tests within the linear viscoelastic range for characterizing the thickener microstructure has contributed to a better understanding of rolling bearing lubrication using lubricating greases. Xu et al. [93] highlighted the correlation between thickener fiber structure and final tribological properties. They concluded that greases with a high degree of fiber entanglement exhibit high structural strength but slower response times, whereas greases with low fiber entanglement display the opposite behavior. Structural strength is critical under mixed or boundary lubrication, while response speed becomes more important under hydrodynamic lubrication. They emphasized that grease microstructure must be designed according to the intended lubrication conditions. Wang et al. [94] noted that rheological parameters such as plateau modulus and yield stress, which depend on the degree of entanglement of the thickener microstructure, can be useful in evaluating the tribological performance of lubricating greases. Ren et al. [95] pointed out the different rates of structural change occurring within the thickener during intensive grease use, using rheological tests conducted at variable strain and constant oscillation frequency. Drabik et al. [96] employed DWS micro-rheology combined with Raman spectroscopy to monitor temperature-induced changes in the microstructure of a plant-based grease thickened with nanosilica. In ref. [97], the potential of coarse-grained molecular dynamics (mesoscale modeling) to describe the microstructure of lubricating greases was demonstrated. Benois et al. showed how the fibrous microstructure of thickeners affects the rheological properties of greases (e.g., viscosity, plasticity, and shear behavior), demonstrating that fiber length, stiffness, and concentration significantly influence overall behavior. They combined molecular modeling with rheological testing to achieve these insights.

7. Summary

The dispersed phase plays a crucial role in determining the performance properties of lubricating greases. The morphology of the particles forming the thickening phase—including their shape, size, and three-dimensional arrangement, as well as the interparticle forces, are key factors influencing, among other aspects, the mechanical stability of grease formulations. Greases with high structural stability retain their consistency longer under various operating conditions, better withstand vibrations, and exhibit lower degradation. Particles forming a three-dimensional, coherent network retain the base oil within the grease mass and determine the thickness of the lubricating film, the grease’s resistance to high loads, and the transition between friction regimes. They therefore have a direct impact on the most important functional properties of lubricating greases. Differences in particle geometry (fibrous, plate-like, spherical) and the forces binding them to the base oil dictate the conditions under which a lubricating grease can be effectively used and how its structure evolves during operation. The dispersed-phase particles, their interactions, agglomeration, formation of superstructures, and behavior under shear have long been the focus of numerous scientific studies, with the importance of this topic already recognized in the 1940s. The application of advanced imaging techniques (SEM, AFM, STM), combined with the parallel development of rheological, spectroscopic, and scattering methods (SAXS, DLS), has fundamentally changed our understanding of the structure and function of lubricating greases. This has allowed the field to move from an empirical description toward a structural–mechanistic understanding. Today, the complementary integration of multiple investigative techniques is essential both for the design of improved lubricating greases and for reliable assessment of their behavior in friction nodes. This integrated approach has become a standard practice in modern tribology and lubrication engineering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., E.K., A.S.; writing—reviewand editing, M.P., E.K.; visualization, M.P.; supervisoion, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to sincerely thank Grzegorz Trykowski, Zofia Czarny and Krystyna Heller for their assistance in the preparation and imaging of lubricating greases using microscopic techniques. The images (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6) presented in this work were acquired at the Electron Microscopy Laboratory of the University of Life Sciences in Wrocław and at the Instrumental Analysis Laboratory of Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| µPIV | Micro-Particle Image Velocimetry |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| ATR-FTIR | Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| cryo-TEM | Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DWS | Diffusing-Wave Spectroscopy |

| EHL | Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| IR | Infrared |

| MPT | Multiple Particle Tracking |

| SAOS | Small-Amplitude Oscillatory Shear |

| SAXS | Small-Angle X-ray Scattering |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| STM | Scanning Tunneling Microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

References

- Boner, C.J. Modern Lubricating Greases; Scientific Publications (G.B.) Ltd.: Broseley, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Velikovsky, D.S.; Poddubny, V.N.; Vainshtok, V.V.; Gotovkin, B.D. Consistent Greases; Khimiya: Moscow, Russia, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Bańkowski, K.; Bańkowski, Z; Basiński, A.; Biernacka, T.; Bochwic, B.; Böhm, J.; Całus, H.; Ciecierska-Stokłosa, D.; Dorabialska, A.; Dybczyński, R.; et al. Poradnik Fizyko-Chemiczny [Physicochemical Handbook], 2nd ed.; Scientific and Technical Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M.A.; Valencia, C.; Sánchez, M.C.; Franco, J.M.; Gallegos, C. Influence of soap concentration and oil viscosity on the rheology and microstructure of lubricating greases. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.J.; Cravath, A.M. Mechanical breakdown of soap-base greases. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1951, 43, 2892–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, S.K.; Luckham, P.F.; Tadros, T.F. Steady flow and viscoelastic properties of lubricating grease containing various thickener concentrations. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 274, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froishteter, G.B.; Trilsky, K.K.; Ishchuk, Y.L.; Stupak, P.M. Rheological and Thermophysical Properties of Greases; Gordon & Breach: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Varius Authors. Słownik Polskiej Terminologii Chemicznej [Dictionary of Polish Chemical Terminology]; Scientific and Technical Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, E. Description of the energy level of tribologically stressed greases. Wear 1995, 138–139, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarny, R. Smary Plastyczne [Greases]; Scientific and Technical Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bartz, W.J. (Ed.) Schmierfette: Zusammensetzung, Eigenschaften, Prüfung and Anwendung [Lubricating Greases: Composition, Properties, Testing, and Applications]; Expert: Renningen, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Paszkowski, M.; Kowalewski, P.; Leśniewski, T. Badania właściwości reologicznych smarów plastycznych zagęszczanych 12-hydroksystearynianem litu [Study of the Rheological Properties of Lubricating Greases Thickened with Lithium 12-Hydroxystearate in the Linear and Nonlinear Viscoelastic Regime]. Tribologia 2012, 4, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Paszkowski, M.; Olsztyńska-Janus, S. Grease thixotropy: Evaluation of grease microstructure change due to shear and relaxation. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2014, 66, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkowski, M. Assessment of the effect of temperature, shear rate and thickener content on the thixotropy of lithium lubricating greases. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. J 2013, 227, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkowski, M.; Olsztyńska-Janus, S.; Wilk, I. Studies of the kinetics of lithium grease microstructure regeneration by means of dynamic oscillatory rheological tests and FTIR–ATR spectroscopy. Tribol. Lett. 2014, 56, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samman, N. Chemistry of aluminum complex grease revisited. NLGI Spokesm. 1992, 7, 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, B.B.; Davis, W.N. Structure of lubricating greases. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1936, 28, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.Q.A. A Comprehensive Review of Lubricant Chemistry, Technology, Selection, and Design; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vold, J.M. Colloidal structure in lithium stearate greases. J. Phys. Chem. 1956, 60, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irina, R.; Radulescu, A.V.; Florin, V. The structure of lubricating greases by electron microscopy. Tribol. Ind. 2004, 26, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, E.; Li, W.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Z. A study on microstructure, friction and rheology of four lithium greases formulated with different base oils. Tribol. Lett. 2021, 69, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarny, R. Badanie zjawisk związanych z przepływem smarów plastycznych w układach smarowniczych [Investigation of Phenomena Related to the Flow of Lubricating Greases in Lubrication Systems]. In Scientific Papers of the Institute of Machine Design and Operation, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Series: Monographs; Wrocław University of Science and Technology Publishing House: Wrocław, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, B.B. The fine structure of lubricating greases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1951, 53, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, R.; Magnin, A. Rheology of colloidal suspensions: Case of lubricating greases. J. Rheol. 1994, 38, 889–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.M.; Delgado, M.A.; Valencia, C.; Sanchez, M.C.; Gallegos, C. Mixing rheometry for studying manufacture of lubricating greases. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 2409–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewis, J. Thixotropy—A general review. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 1979, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckham, P.F.; Rossi, S. The colloidal and rheological properties of bentonite suspensions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999, 82, 43–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarny, R.; Paszkowski, M. The influence of graphite solid additives, MoS2 and PTFE on changes in shear stress values in lubricating greases. J. Synth. Lubric. 2007, 24, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, H. Lehrbuch der Kolloidwissenschaft; VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften: Berlin, Germany, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mackwood, W.; Muir, R. Calcium sulfonate grease… one decade later. NLGI Spokesm. 1999, 63, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hone, D.C.; Robinson, B.H.; Steytler, D.C.; Glyde, R.W.; Galsworthy, J.R. Mechanism of acid neutralization by overbased colloidal additives in hydrocarbon media. Langmuir 2000, 16, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, R.J. High performance calcium sulfonate complex lubricating grease. NLGI Spokesm. 1988, 52, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.; Ren, G.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Xing, M. Investigating the effect of overbased sulfonates on calcium sulfonate complex grease. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 32992–33006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopacka-Łyskawa, D. Synthesis methods and favorable conditions for spherical vaterite precipitation: A review. Crystals 2019, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makedonsky, O.; Kobylyansky, E.; Ishchuk, Y. Structure and physico-chemical properties of overbased calcium sulfonate complex greases. Eurogrease 2003, 1, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ševčík, R.; Šašek, P.; Viani, A. Physical and nanomechanical properties of the synthetic anhydrous crystalline CaCO3 polymorphs. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 4022–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Ratner, B.D. Surface and interface analysis of calcium carbonate polymorphs. Surf. Interface Anal. 2008, 40, 1356–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagenas, N.V.; Gatsouli, A.; Kontoyannis, C.G. Quantitative analysis of synthetic calcium carbonate polymorphs using FT-IR spectroscopy. Talanta 2003, 59, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakunin, V.N.; Aleksanyan, D.R.; Bakunina, Y.N. Calcium carbonate polymorphs in overbased oil additives and greases. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2022, 95, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, G.; Wang, X. Tribological behavior of amorphous and crystalline overbased calcium sulfonate as additives in lithium complex grease. Tribol. Lett. 2012, 45, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, W.H.; Finkelstein, A.P.; Wiberley, S.E. Flow properties of lithium stearate-oil model greases as a function of soap concentration and temperature. ASLE Trans. 1960, 3, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajezierska, A. Stabilność koloidalna smarów plastycznych [Colloidal Stability of Lubricating Greases]. Nafta Gaz 2011, 8, 572–576. [Google Scholar]

- Lugt, P.M. Grease Lubrication in Rolling Bearings; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Olsztyńska-Janus, S.; Paszkowski, M. Behavior of hydrogen bonds in lithium grease during shearing and stress relaxation. In Proceedings of the The 21st International Conference on “Horizons In Hydrogen Bond Research” (HBOND 2015), Wrocław, Poland, 13–18 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Czarny, R. Wpływ struktury smaru plastycznego na jego własności reologiczne [Influence of Grease Structure on Its Rheological Properties]. In Scientific Papers of the Institute of Machine Design and Operation; Wrocław University of Science and Technology Publishing House: Wrocław, Poland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, C.J. Lubricating grease: A chemical primer. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Thixotropie; Hermann: Paris, France, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Péterfi, T. Die Abhebung der Befruchtungsmembran bei Seeigeleiern: Eine kolloidchemische Analyse. Wilhelm Roux’ Arch. Dev. Mech. Organ. 1927, 112, 660–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagaly, G.; Beneke, K.; Kutatádok, H.K.; Anyagtudományi, M.K. Eighty Years of Colloid Science in Hungary and Germany; University Kiel: Kiel, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Czarny, R. Effects of changes in grease structure on sliding friction. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 1995, 47, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonggang, M.; Jie, Z. A rheological model for lithium lubricating grease. Tribol. Int. 1998, 31, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E. Some considerations to the energy dissipation of frictionally stressed lubricating greases. Lubricants 2025, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarny, R. A study of Thixotropy Phenomen in Lubricating Greases. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on Tribology (Eurotrib 89), Helsinki, Finland, 12–15 June 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Czarny, R. Effect of Temperature on the Thixotropy Phenomenon in Lubricating Greases. In Proceedings of the Japan International Tribology Conference, Nagoya, Japan, 29 October–1 November 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kozdrach, R. Application of Raman Spectroscopy to Evaluate the Structure Changes of Lubricating Grease Modified with Montmorillonite after Tribological Tests. Processes 2024, 12, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramhall, A.D.; Hutton, J.F. Wall effect in the flow of lubricating greases in plunger viscometers. Br. J. Appl. Phys. 1960, 11, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, G.V.; Froishteter, G.B.; Trilisky, K.K.; Smorodinsky, E.L. The flow of plastic disperse systems in the presence of the wall effect. Rheol. Acta 1975, 14, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, G.V.; Froishteter, G.B.; Trilisky, K.K. Generalized theory of flow of plastic disperse systems with wall effect. Rheol. Acta 1978, 17, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarny, R. Influence of surface material and topography on the wall effect of grease. Lubr. Sci. 2002, 14, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.A. A review of the slip (wall depletion) of polymer solutions, emulsions and particle suspensions in viscometers: Its cause, character, and cure. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 1995, 56, 221–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, C.; Franco, J.M. Influence of geometry on the transient and steady flow of lubricating greases. Tribol. Trans. 2001, 44, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, K. Analiza zjawisk zachodzących w warstwie przyściennej smaru plastycznego [Analysis of Phenomena Occurring in the Wall Layer of Lubricating Grease]. Tribologia 2006, 5, 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Paszkowski, M.; Wróblewski, R.; Walaszczyk, A. Influence of temperature and surface energy state on wall effects in soap-based greases. Tribol. Lett. 2017, 65, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duenas-Dobrowolski, J. Metody wizualizacji ruchu smaru w uszczelnieniach labiryntowych [Methods for Visualization of Grease Flow in Labyrinth Seals]. Zesz. Energetyczne 2014, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Duenas-Dobrowolski, J. Określenie profili prędkości smaru w szczelinie uszczelnienia bezstykowego za pomocą mikroanemometrii obrazowej (μPIV) [Determination of Grease Velocity Profiles in a Non-Contact Seal Gap Using Microparticle Image Velocimetry (μPIV)]. Zesz. Energetyczne 2015, 2, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Duenas-Dobrowolski, J.; Gawliński, M.; Paszkowski, M.; Westerberg, L.G.; Höglund, E. Experimental study of lubricating grease flow inside the gap of a labyrinth seal. Tribol. Trans. 2018, 61, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Wong, P.L.; Geng, M.; Kaneta, M. Occurrence of wall slip in EHL contacts. Tribol. Lett. 2009, 34, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallay, W.; Puddington, I.E.; Tapp, J.S. Fibre structure in dispersions of soap in mineral oil. Can. J. Res. 1944, 22, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, B.B.; Birdsall, D.H. Study of lubricating greases by electron microscope. Oil Gas J. 1947, 45, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Baart, P.; van der Vorst, B.; Lugt, P.M.; van Ostayen, R.A. Oil-bleeding model for lubricating grease based on viscous flow through a porous microstructure. Tribol. Trans. 2010, 53, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyriac, F.; Lugt, P.M.; Bosman, R.; Padberg, C.J.; Venner, C.H. Effect of thickener particle geometry and concentration on grease EHL film thickness. Tribol. Lett. 2016, 61, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, A.; Cann, P. Examination of grease structure by SEM and AFM techniques. NLGI Spokesm. 2001, 65, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Salomonsson, L.; Stang, G.; Zhmud, B. Oil/thickener interactions and rheology of lubricating greases. Tribol. Trans. 2007, 50, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.C.; Franco, J.M.; Valencia, C.; Gallegos, C.; Urquiola, F.; Urchegui, R. Atomic force microscopy and thermo-rheological characterization of lubricating greases. Tribol. Lett. 2011, 41, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Meehan, P.A. Microstructure characterization of degraded grease in axle roller bearings. Tribol. Trans. 2019, 62, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, C.; Valencia, C.; Franco, J.M. AFM and SEM assessment of lubricating grease microstructures. Tribol. Lett. 2016, 63, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Kumar, D.; Tandon, N. Development of eco-friendly nano-greases based on vegetable oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 172, 114033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Zhu, M.; Xia, Y.; Wang, J. Probing the effect of thickener on tribological properties of lubricating greases. Tribol. Int. 2018, 118, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahme, L.; Kuhn, E.; Canto, M.Á.D. Optical assessment of structural degradation of rheologically stressed lubricating greases. Tribol. Int. 2023, 187, 108771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisko, A.W. The flow of lubricating greases. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1958, 50, 1789–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, E.O.; Kolfenbach, J.J. Viscoelastic behavior of greases. ASLE Trans. 1959, 2, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criddle, D.W. Typical lubricating greases as linear viscoelastic materials. Trans. Soc. Rheol. 1965, 9, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J.F. Grease rheology. In Principles of Lubrication; Cameron, A., Ed.; Longman: London, UK, 1966; Chapter 23. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R.S. Review of recent USA publications on lubricating grease. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Conf. Proc. 1969, 184, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Czarny, R. Einfluss der Thixotropie auf die rheologischen Eigenschaften der Schmierfette [Influence of Thixotropy on the Rheological Properties of Lubricating Greases]. Tribol. Schmierungstech. 1989, 36, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Mas, R.; Magnin, A. Rheological and physical studies of lubricating greases before and after use in bearings. J. Tribol. 1996, 118, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E. Energetics of the time-dependent flow behaviour of greases. Appl. Rheol. 1997, 7, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E. Experimental grease investigations from an energy point of view. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 1999, 51, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, A.; Hodapp, A.; Hochstein, B.; Willenbacher, N.; Jacob, K.H. Low-Temperature Rheology and Thermoanalytical Investigation of Lubricating Greases: Influence of Thickener Type and Concentration on Melting, Crystallization and Glass Transition. Lubricants 2021, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodapp, A.; Conrad, A.; Hochstein, B.; Jacob, K.H.; Willenbacher, N. Effect of base oil and thickener on texture and flow of lubricating greases: Insights from bulk rheometry, optical microrheology and electron microscopy. Lubricants 2022, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wang, X.; Ma, R.; Li, W.; Zhang, M. Insights into the rheological behaviors and tribological performances of lubricating grease: Entangled structure of a fiber thickener and functional groups of a base oil. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.A.; Sánchez, M.C.; Valencia, C.; Franco, J.M.; Gallegos, C. Relationship among microstructure, rheology and processing of lithium lubricating grease. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2005, 83, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, G.; Wang, X. New insight into tribology–structure interrelationship of lubricating grease. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 54202–54210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Lin, J.; Gao, X. Rheological and tribological properties of lithium and polyurea greases. Coatings 2022, 12, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Cai, H.; Zhao, G.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X. Study of the changes in the microstructures and properties of grease using ball milling to simulate a bearing shear zone on grease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drabik, J.; Kozdrach, R.; Szczerek, M. Characterization of nano-silica vegetable grease using DWS and Raman spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benois, A.; Echeverri Restrepo, S.; De Laurentis, N.; Hogenberk, F.; Giuntoli, A.; Lugt, P.M. A coarse grained molecular dynamics model for the simulation of lubricating greases. Tribol. Lett. 2024, 72, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.