Abstract

The classic four-ball test was developed in the 1930s and has remained unchanged to this day. This versatile and widely used methodology would benefit from further development with modern tools and techniques. The classic four-ball test is traditionally performed with load steps, which makes it slow, and determining the exact last non-seizure load is quite challenging. To overcome this situation, a new methodology for testing the high-pressure properties (EP) of greases and oils is presented, using a continuous, constant-load ramp rate. The peak in the evolution of the coefficient of friction represents the occurrence of the last non-seizure sliding. The load at which the final non-seizure sliding occurs is defined as the last non-seizure load (LNSL). The obtained results are consistent with historical experience with “classic” four-ball EP tests, and the test procedure is fast and highly repeatable.

Keywords:

four-ball; extreme pressure; EP; oil; grease; constant load ramp rate; last non-seizure load; scuffing; seizure 1. Introduction

Mechanical equipment is made by systematically arranging different components. To support moving components, different types of bearings are used. Different design considerations, effective lubrication methods, and the development of lubricants are important for the smooth and efficient operation of the mechanical system [1,2,3]. In the process of lubricant development, assessing lubrication properties is essential to selecting the most suitable lubricant for different applications.

The four-ball test is an important standardized test method for the identification of extreme pressure and anti-wear properties of the lubricants [4] and plays a crucial role in the development of the advanced lubricants for modern, evolving demands. Methodologies for determining extreme pressure (EP) properties of the lubricants and with a global reach in research and industry were initially developed many decades before, for example, the four-ball (1934), TIMKEN (1932), FZG (1934) and SRV (1965) methods.

ASTM D2596 [5] and ASTM D2783 [6] provide well-recognized performance parameters, i.e., last non-seizure load (LNSL) and weld load, for lubricating greases and oils, respectively. They used dead weights, which triggered load-step tests; even SRV applies load via a servomotor and still uses load steps. The standardization working groups of ASTM D02 and DIN-FAM have identified unconsidered, systematic “errors/issues/concerns” with four-ball testing in recent years, which need to be addressed [4,7]. Some of these issues have persisted since 1943 [8]. The observations/concerns about the current four-ball test methods were [4,7,9]:

- Last non-seizure load identified by step loading; detection of the exact last non-seizure load is challenging [4].

- No definition, measurement and control of the acceleration rate of the spindle (motor) [7,9].

- Need to implement an electronic speed controller [9].

- The steel metallurgy of the balls is imprecise, including the finishing (topography).

- The range of microhardness is too wide [4].

- Uniform specification of cleaning solvent and its usage [4].

Espinoux et al. [7] highlighted that different rates of spindle acceleration to attain the final test speed can yield false extreme-pressure properties for the lubricants. Later, Joysula et al. [9] discovered the misleading extreme pressure property with different rate spindle acceleration, which validated the findings of Espinoux et al. [7]. Irrespective of the above-mentioned challenges, four-ball tests developed in the 1930s are used widely on a global scale; this suggests a strong need to revise the method with a new impetus, especially in terms of including sensors, actuation systems, and load control and drive technologies of today.

In the four-ball tests, the “last non-seizure load” and “weld point” can be determined for oils and greases. The last “last non-seizure load” is of importance because the incipient loss of EP protection is accompanied by an increase in wear and is visualized by plotting the wear scar diameter versus load. In the FZG test, the transition from low wear to high wear is visualized by plotting the mass loss versus transmitted work (load stage). This article presents a new extreme-pressure test methodology using a continuous, constant load ramp rate, suitable for standardization. It is faster and aligns with the historical horizons of the current ASTM, DIN, ISO, and SAC tests for the four-ball method.

2. Methodology of Constant Load Ramp Rate

For determining the wear resistance of the lubricants for non-scuffing during the anti-wear test, the initial load should not be less than 40 kgf (392 N), as per ASTM D2266 (grease) [10] and ASTM D4172 (oil, method B) [11]. The homologue test loads in DIN 51350-3 (oil, method B) [12] are 300 N and also in DIN 51350-5 (grease, method D) [13], and DIN 51350-5 (grease) enables as method E [14] under 1000 N.

The first test load in ASTM D2596 (grease) [5] and D2783 (oil) [6] is 80 kgf (784 N). The next incremental load stages are higher or lower depending on the wear scar diameter results at 80 kgf. Starting at 80 kgf (784 N) will limit testing time and temperature changes caused by the generated frictional heat.

The EP test using a constant load ramp rate may start with an applied load of 392 N or 784 N. The variable load may be applied by a controllable loading device with a servomotor.

If the evolution in load steps is linearized for the four-ball test and SRV based on the existing procedures, the following load increase rates are calculated:

- 6.36 N/s as in D5706 and D7421 [Ø = 10 mm ball, oscillating tests],

- 10.18 N/s to 40.74 N/s in 4-ball EP testing (ASTM D2596 and D2783) and/or

- 0.705 MPa/s as a constant Hertzian contact stress increase (as per FZG).

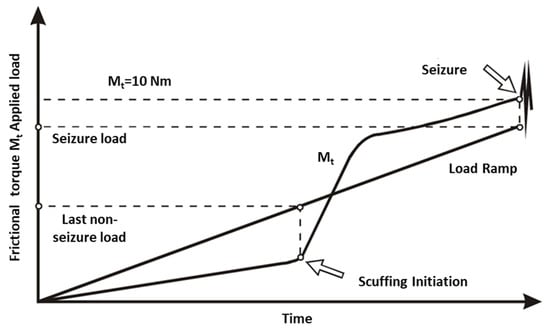

Szczerek et al. [15] modified the four-ball EP test by using a constant load ramp rate of 406 N/s (RT, 500 rpm, initial load: 0 N). This new test methodology was highly repeatable. Figure 1 illuminates the schematic evolution of torque. In this single test, the “last non-seizure load” and “weld point” can be determined.

Figure 1.

Schematic evolution of friction torque curve (Mt) versus test time under a constant load ramp rate in a four-ball test [9].

In the present work, a PAO polyurea thickened, NLGI Batch-4 grease, and an e-axle fluid (KV40 = 25.5 mm2/s) are used to evaluate extreme pressure properties using the new 4-ball EP test method. The following section describes the complete test methodology.

The 4-ball tests were performed on the MFT-5000 platform using the 4-ball module from Rtec Instruments, San José, CA, USA. This platform is capable of controlling the acceleration rate of the spindle. We have used a normal load sensor with a maximum load capacity of 10,000 N and a torque sensor with a maximum torque capacity of 20 N-m. A servo-controlled motorized system is used for normal loading and rotating the upper ball. We have chosen four 12.7 mm diameter steel balls as per ASTM D2596 (grease) and D2783 (oil) standards. The balls were cleaned ultrasonically with single-boiling-point spirit, and the samples were mounted as per the ASTM standard. In our proposed methodology, we first applied a normal load of 400 N without rotation. After application of the normal load, a running-in of 60 s was performed at 400 N load and 1770 rpm. For the loading rate of 78.448 N/s experiments, running-in was performed at 1760 rpm. Without running-in, experiments were also performed for the assessment of the effect of running-in. The desired rotational speed was attained in one second. A constant loading rate of 78.448 N/s, 60 N/s for NLGI grade 2 grease, 30 N/s for the e-axle fluid, and 60 N/s for NLGI Batch-4 grease was chosen for the assessment of the extreme pressure properties of the selected lubricants. Coefficient of friction is chosen as a parameter for the termination of the test, as we have noticed that the coefficient of friction data depicts a larger peak, roughly a magnitude of ~0.6 at the last non-seizure load (LNSL), and magnitude > 1 at the weld load. Therefore, the selection of the coefficient of friction provides good control over the experiment. We can exactly stop the test at the LNSL load. Tests were stopped at different normal load values, also for the assessment of the evolution of wear diameter with increasing load. The load-carrying capacity until scuffing, as the geometric contact stress in MPa, can be determined by dividing the load right before the increase in friction by the contact area of the wear scars. After the experiment, samples were cleaned ultrasonically, and the worn surfaces were examined under an optical microscope.

3. Results and Discussion

Load ramp rates of 30 N/s for oils and 60 N/s for greases represent an optimal balance between dissipation of frictional heat and safe tribofilm formation. In the following sections, different plots and figures will illustrate the last non-seizure loads at 78.5 N/s, 60 N/s, and 30 N/s. The rotational speed was 1770 rpm and 1760 rpm, respectively.

With a radius of 3.66 mm in the contact zone from the rotating axis, when using 12.7 mm balls, results in a sliding speed of 0.678 m/s at 1770 rpm. By using a load of 392 N (392 N/√6 on each ball), an initial Hertzian contact pressure P0mean of 2246 MPa calculates and transduces to a P·V value [16] or “mechanical power density” of 228 W/mm2 times the Hertzian contact area of three balls of 0.213 mm2 with an assumed coefficient of friction of 0.15 generate a frictional heat work of 48.7 W at test begin.

Assuming a “last non-seizure load” of 1880 N (767 N on each ball) with a scar diameter of 0.51 mm (or 0.60 mm2 for three balls) in the further load evolution of this test, a frictional heat power of 231 W is calculated at this point with a friction coefficient of 0.15. This represents a substantial increase compared to the start of the test. Since the geometric contact pressure at this point is Pmean = 3797 MPa, as shown e.g., in Figure 3b, we have not only a high load-bearing capacity of the tribofilm at the “last non-seizure load,” but also resist to a high heat flow density (or thermal carrying capacity) in terms of a P·V value of 2.567 W/mm2 expressed as “mechanical power density”, a quantity that design engineers can easily determine. Thus, for lubricants with pronounced extreme pressure capabilities, this continuous load increase test determines tribological functional gains.

The initially proposed range of load ramp rates, from 10 N/s to 400 N/s, is too wide for the new four-ball EP test methodology. 10 N/s will allow sufficient reaction time for the complete formation of protective tribofilms, if the case, but will result in long testing times with heat generation and increased sample temperatures. 100 N/s or 400 N/s on one side limits temperature increase by frictional heat, but weakens the tribofilm formation, because the tribofilms cannot build up fast enough.

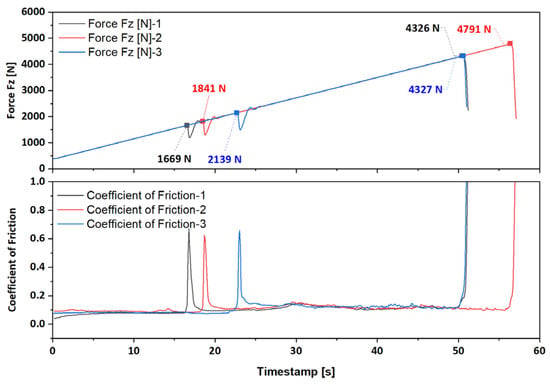

3.1. Evolution of Coefficient of Friction of Lithium Complex Grease, NLGI 2

The 4-ball tests were executed in the MFT-5000 platform with a four-ball module from Rtec Instruments, San José, CA, USA. Starting from 400 N, the initial Hertzian contact pressure is P0max = 3393 MPa (P0mean = 2262 MPa) and P0max = 4274 MPa (P0mean = 2850 MPa) for 800 N, while 392 N is the initial load in D2266 & D4172 and 784 N in D2596 & D2783. The plots in Figure 2 were executed without running-in. Without considering a reduction in Hertzian contact stress by fast and unavoidable running-in wear, the initial Hertzian contact stress would correspond literally to a FZG load stage of far greater than 14 (or P0max = 2170 MPa). Figure 2 plots the coefficient of friction versus test time and illuminates the points of “last non-seizure load” and “weld point” as disclosed by Szczerek et al. [15]. The load right before the jump in the coefficient of friction (high peak) is considered as “last non-seizure load”, because the loss of wear protection is initiated from that point.

Figure 2.

Evolution of normal load and coefficient of friction at a constant load ramp rate of 78.448 N/s with 60 s running-in at 1760 rpm in lithium complex grease, NLGI 2.

Figure 2 shows triplicate test results for the evolution of normal load and coefficient of friction during a 60 s running-in at 392 N normal load and 1760 rpm at ambient temperature (T ~ 28 °C). The load was ramped from 392 N with a loading rate of 78.448 N/s. The magnitude of the normal load is marked at the onset of the last non-seizure load and the onset of the weld load. We have found the %RSD (relative standard deviation) for the previous non-seizure load of 10% and the weld load of 5%, which demonstrates the capability of the proposed test conditions. Overheating concerns may arise at a 78.448 N/s loading rate, and heat dissipation can be improved or minimized by using a cup with high thermal conductivity or by reducing speed. In the following, the ramp rate was reduced to 60 N/s to allow the formation of effective tribofilms, which need some reaction time, depending on the type of additive package.

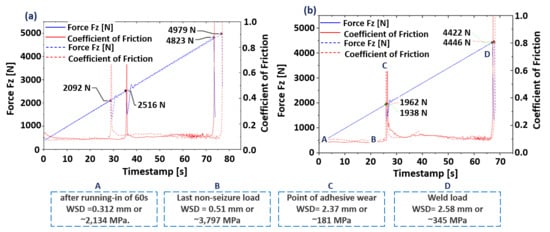

Similar to the above tests, several more tests were performed using the lithium complex grease, NLGI 2. Figure 3a shows the 4-ball EP test results for lithium complex grease, NLGI 2, at a constant loading rate of 60 N/s from 400 N to the weld point at 1770 rpm. Tests were repeated twice, and we found the %RSD (percentage relative standard deviation) for the last non-seizure load is 9% and for the weld load is 2%, which is well within 10% of variation.

Figure 3.

Evolution of normal load and coefficient of friction at a constant load ramp rate of 60 N/s at 1770 rpm in lithium complex grease, NLGI 2 (a) without running-in and (b) with a running-in of 60 s at normal load 400 N, 70 °C. The text in the dashed boxes corresponds to the marked points in Figure 3b.

However, we have performed the same test with 60 s of running-in at 400 N. Figure 3b shows the evolution of the normal load and the coefficient of friction after completion of the running-in. It has been observed that the %RSD for the last non-seizure load and weld load is within 1%, which shows excellent repeatability of the results.

At the end of the running-in, contact stress was ~2134 MPa, i.e., the initial geometric contact stress. Wear scar diameter at this instant is 0.312 mm. For the assessment of the evolution of the wear scar diameter, the test was stopped when the normal load reached 1800 N. We found the wear scar diameter to be 0.51 mm, corresponding to a load-carrying capacity of Pmean ~ 3797 MPa. A steep rise in the coefficient of friction data (a magnitude of more than 0.4) represents the last non-seizure point. Therefore, to identify the wear scar diameter at the point of last non-seizure load, the test was stopped at the first peak in the coefficient of friction, using an automatic stop criterion for the coefficient of friction. At the point of last non-seizure load, we have found the diameter of the wear scar to be 2.37 mm, with an associated drop in geometric contact stress to Pmean ~ 181 MPa. As a consequence of this loss in protection against scuffing, the wear scar diameter enlarges very fast and lowers the contact stress, so that the tribological system may “recover”, whereby the coefficient of friction will not decrease to values before this event, because the surfaces are heavily pre-damaged.

Furthermore, the test was stopped at 3800 N normal load, and the wear scar diameter increased slightly to 2.58 mm, corresponding to Pmean ~ 345 MPa. As the protections against wear and scuffing were lost, it is not practical to continue the test after the last non-seizure load until scuffing occurs. As the wear scars became at last non-seizure load, the wear scars became so large that it is questionable if grease can enter sufficiently into the tribo-contact, and the test continues under geometric contact stresses of <200 MPa. After attaining the last non-seizure load, a significant increase in the wear scar diameter is evident, indicating a severe wear regime over a short time interval and a very high wear rate. As a result of high wear in this short time interval, the upper loading drive has to come down to accommodate the load at that magnitude. This phenomenon can be seen as the drop in the loading curve. Load relaxation due to the sudden linear wear rate at this point is attributed to a drop in the load. The loss of function expressed by a loss in extreme pressure and wear protection is characterized by the low wear/high wear transition, which is indicated by both

- a steep rise in the coefficient of friction and

- in a spontaneous drop in load due to a spontaneous increase in linear wear.

3.2. Evolution of Coefficient of Friction of NLGI Batch 4 Grease

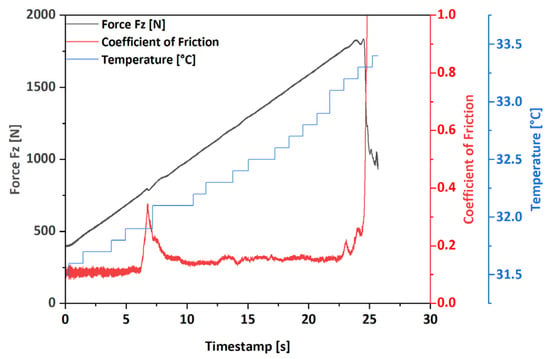

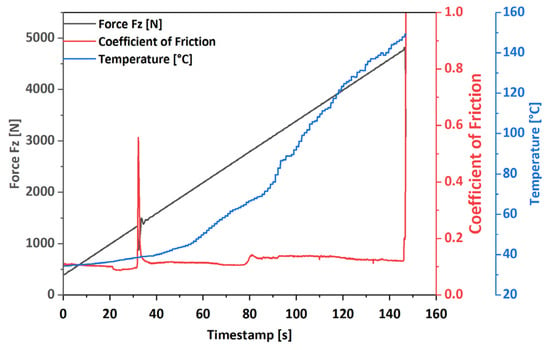

Figure 4 shows the evolution of temperature in the four-ball extreme pressure test of NLGI batch 4 grease. The test was started at room temperature (~30 °C). After attaining the last non-seizure load, the temperature increased from 31.5 °C to 33.5 °C. Hence, it can be inferred that frictional heating contributes to a roughly 2 °C increase in temperature throughout the test. This increase in temperature is not sufficient to alter the metallurgy of the AISI 52100 balls through annealing. The sample temperature remained relatively stable until LNSL. Therefore, maintaining the temperature inside the cup is not required. A similar sudden increase in the coefficient of friction (Figure 4) indicates the occurrence of LNSL load. At the time of occurrence of LNSL, the load magnitude of the drop in the normal load is quite small as compared to the lithium complex grease (Figure 3), NLGI 2 and e-axle oil (Figure 5). This slight drop in normal load indicates a lower level of wear during LNSL. A small step increase in the wear scar diameter for NLGI batch 4 grease (see Figure 7) again supports this fact.

Figure 4.

Evolution of temperature at a constant load ramp rate of 60 N/s with a running-in period of 60 s at normal load 400 N, 70 °C and a rotational speed of 1770 rpm in lithium complex grease, NLGI 2.

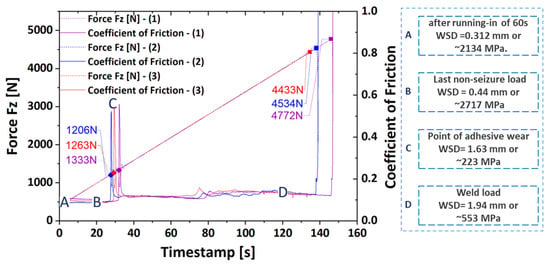

Figure 5.

Evolution of normal load and coefficient of friction at a constant load ramp rate of 30 N/s with a running-in period of 60 s at normal load 400 N, and a rotational speed of 1770 rpm in e-axle Oil.

3.3. Evolution of Coefficient of Friction of an e-Axle Oil

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the coefficient of friction and the normal load with time during running-in. Average last non-seizure load was found to be at 1267 N with a %RSD value of 4%, and average weld load was 4579 N with a %RSD value of 3%. Again, the triplicate test output shows a very good repeatability of the test procedure. The geometric contact stress LNSL load at the peak was Pmean ~ 247 MPa, and the weld load was ~623 MPa.

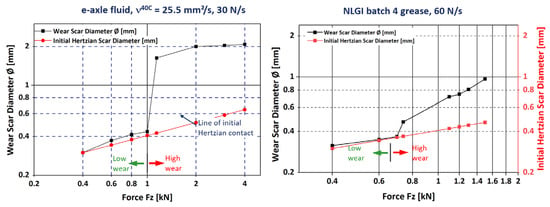

The oil sample temperature remained stable until scuffing (see Figure 6). Figure 7 shows the evolution of the wear scar diameters with increasing load from interrupted tests on the left side for the axle oil and on the right for lithium complex grease, NLGI batch 4. The plots have almost similar evolutions as per a low-wear to high-wear transition, as displayed in the ISO20623 test standard [17]. Therefore, it can be concluded that the new test protocol for the four-ball extreme pressure test with a constant load ramp rate is fast and accurate and closely resembles the existing classic standard test method.

Figure 6.

Evolution of temperature at a constant load ramp rate of 30 N/s with a running-in period of 60 s at normal load 400 N, RT and a rotational speed of 1770 rpm of e-axle fluid.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the evolution of the wear scar diameter and the initial Hertzian contact diameter, similar to ISO20623.

From Figure 7, it can be inferred that before reaching the peak value of LNSL load, the measured average scar diameter is very close to the initial Hertzian scar diameter and underlines a good wear protection. Therefore, the Hertzian scar diameter just before attaining the LNSL can be used to calculate the load-carrying capacity of the particular grease. Table 1 shows the properties of the grease obtained using the proposed new test methodology. The load-carrying capacity presented in Table 1 is obtained by considering the scar area measured just before attaining the LNSL peak. NLGI batch 4 grease shows a 730 N on LNSL load (see Table 1), which is very close to the reference value of 720 N ± 181 N reported in ASTM D2596. The output of the new test methodology is very close, and it validates this methodology for future assessment of the lubrication property.

Table 1.

4-ball extreme pressure lubrication properties of the different types of grease.

Even the steep/step peak with the associated drop in load indicates adhesive wear (scuffing), the exact point of this last non-seizure load to be reported needs to be defined. In a software-based evaluation, the half-width of the peak on the rising side can be defined. Another approach, either using software or manually, is to determine a point of increase in the friction coefficient of, for example, 5% or 10% above baseline evolution of CoF before the peak.

4. Conclusions

The classic four-ball test was developed many decades earlier; it is a simple and widely used test methodology (ASTM D2596 and ASTM D2783) for obtaining the extreme pressure properties of the lubricants today. Despite its simplicity, there are some shortcomings highlighted in Section 1. To address those issues, an advanced four-ball test methodology is adapted. Extensive experimentation and comparisons with standard data reveal that the new four-ball method for evaluating the extreme-pressure properties of lubricants provides repeatable, reliable results. The last non-seizure load and weld load are obtained very easily, and those are in good correlation with the classic four-ball test results. Evolution of the wear scar diameter is similar to the evolution described in the ISO20623 standard. Therefore, it can be concluded that it is a rapid tribological methodology for both greases and oils. The constant load ramp rate EP test presents a time-efficient methodology and makes the four-ball tribometry a good fit for the future. Executing the tests in interrupted stages, it enables the determination of a maximum contact stress (load-carrying capacity) until scuffing occurs. In the frame of this approach, all other “issues/concerns” related to the current four-ball test methods need to be clarified in the standardized method.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was covered using a discount coupon available to the corresponding author.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Krishnamurti Singh was employed by Rtec Instruments India Pvt. Ltd. Author Tushar Khosla was employed by Rtec Instruments, Inc. Author Mathias Woydt was employed by MATRILUB. Authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.Z. Influence of the cage on the migration and distribution of lubricating oil inside a ball bearing. Friction 2022, 10, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ni, H.; Xu, Z.; Pan, G. A simulation analysis for lubricating characteristics of an oil-jet lubricated ball bearing. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2021, 113, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Yu, C.; Sun, Y. Multi-objective analysis design of spiral groove conical bearing considering cavitation effects. Results Eng. 2022, 15, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikin, A.R. Lubricating grease testing—Challenges have been identified with ASTM D2596 test method’s repeatability and reproducibility. Tribol. Lubr. Technol. 2025, 81, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D2596-20; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Extreme-Pressure Properties of Lubricating Grease (Four-Ball Method). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D2783-21; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Extreme-Pressure Properties of Lubricating Fluids (Four-Ball Method). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Espinoux, F.; Bourdin, F.; Genet, N. When a lively Four-Ball Crescendo takes on a Weld! ELGI Eurogrease 2020, Q3, 21–28. Available online: https://www.elgi.org/members-area-download/eurogrease (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Krienke, C.F. Versuche an einem Vierkugel-Ölprüfgerät, DVL-Mitteilungen Nr. 715, 25. March 1943, Berlin. Translated by “Combined Intelligence Objectives Sub-Committee”, Krienke, C., Tests on a Four-Ball Oil Test Machine, 1943, Report No. 715, German Institute for Aeronautical Research. Available online: https://www.fischer-tropsch.org/Tom%20Reels/Linked/TOM%20248/TOM-248-0419-0424%20FD2869-46-Lt15.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Joysula, S.K.; Dube, A.; Patro, D.; Veeregowda, D.H. On the Fictitious Grease Lubrication Performance in a Four-Ball Tester. Lubricants 2021, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2266-23; Standard Test Method for Wear Preventive Characteristics of Lubricating Grease (Four-Ball Method). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d2266-23.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- ASTM D4172-21; Standard Test Method for Wear Preventive Characteristics of Lubricating Fluid (Four-Ball Method). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d4172-21.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- DIN 51350-3; Testing of Lubricants—Testing in the Four-Ball Apparatus—Part 3: Determination of Extreme-Pressure Properties of Lubricating Oils (Method B). Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [CrossRef]

- DIN 51350-5; Testing of Lubricants—Testing in the Four-Ball Apparatus—Part 5: Determination of Extreme-Pressure Properties of Lubricating Greases (Method D). Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [CrossRef]

- DIN 51350-5; Testing of Lubricants—Testing in the Four-Ball Apparatus—Part 5: Determination of Wear Characteristics of Lubricating Greases under Load (Method E). Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kalbarczyk, M.; Michalczewski, R.; Piekoszewski, W.; Szczerek, M. The influence of oils on the scuffing of concentrated friction joints with low friction coated elements. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. (Maint. Reliab.) 2013, 15, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kloß, H.; Woydt, M. Prediction of tribological limits in sliding contacts: Flash temperatures calculations in sliding contacts and materials behaviour. J. Tribol. 2016, 138, 031403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 20623:2017; Petroleum and Related Products—Determination of the Extreme-Pressure and Anti-Wear Properties of Lubricants—Four-Ball Method (European Conditions). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/70737.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.