Comparative Analysis of CNN and LSTM for Bearing Fault Mode Classification and Causality Through Representation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To compare the performance of STFT-based CNN models and handcrafted-feature-based LSTM models in fault classification of rotating machinery using a simplified, interpretable framework.

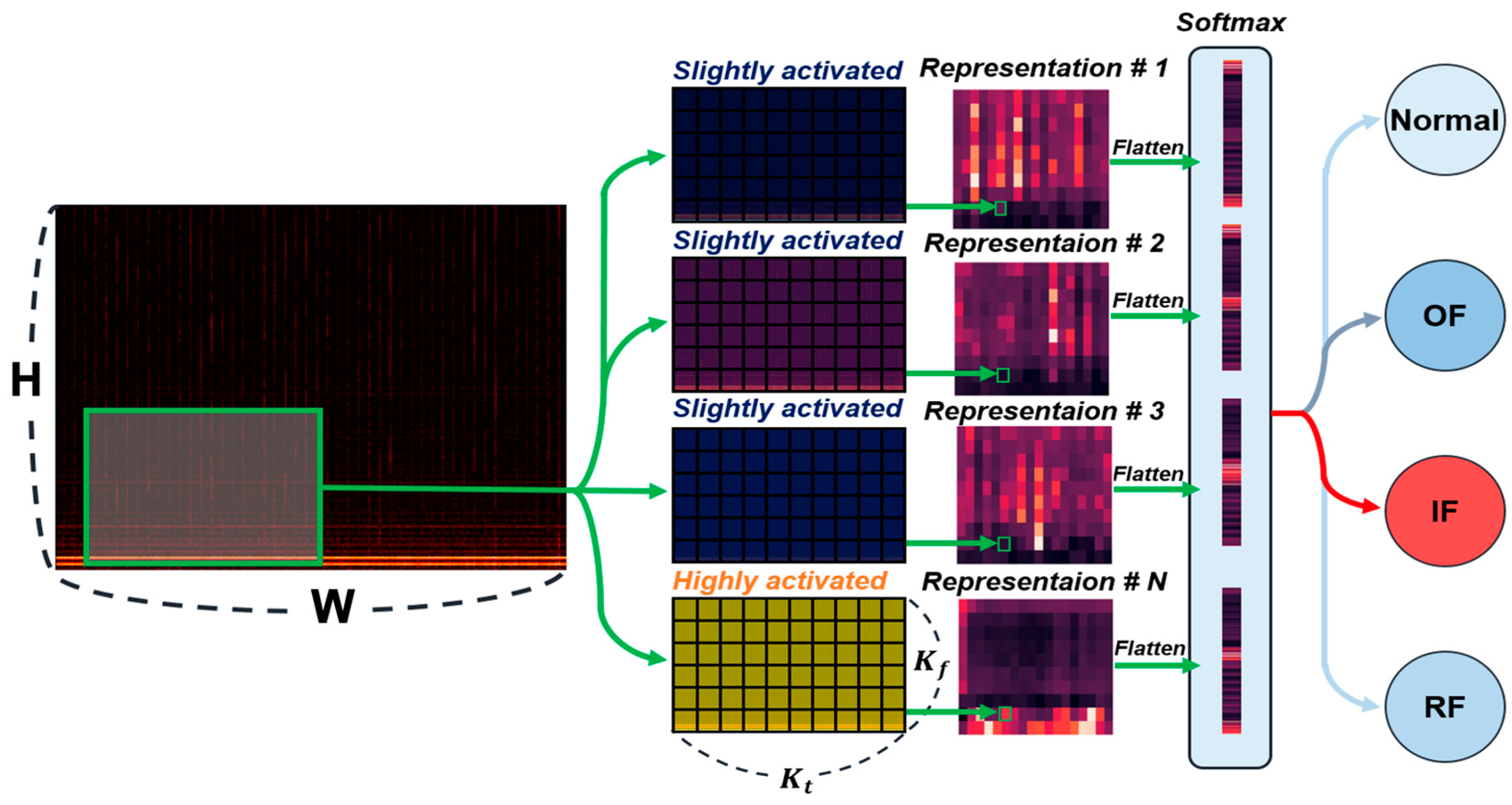

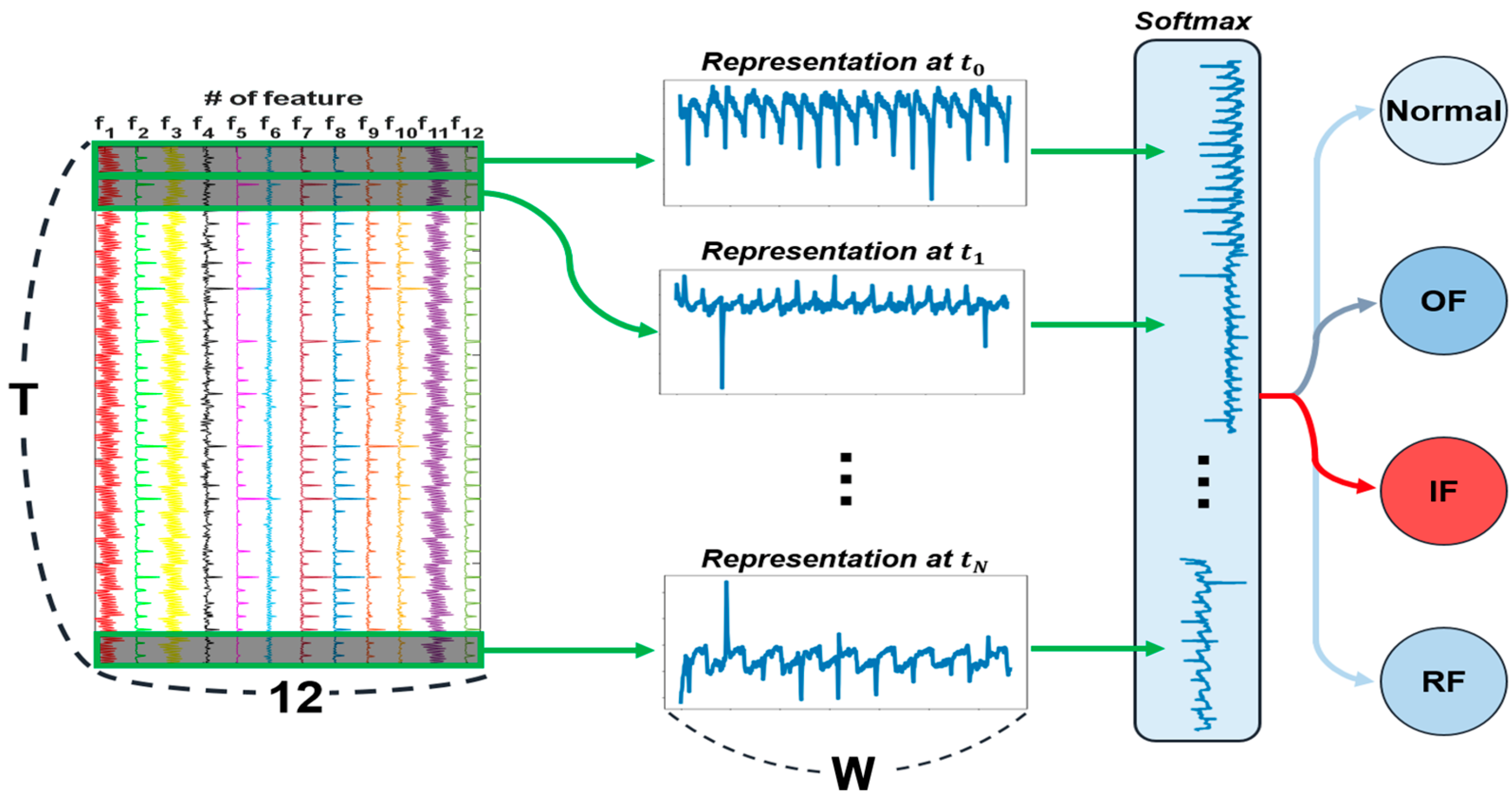

- To analyze the reasons behind performance differences from the perspective of representation learning and fundamental network architecture.

- To correlate learned representations with physically interpretable features for deeper insight into fault characteristics and provide practical model selection guidelines.

2. Theoretical Backgrounds

2.1. Convolutional Neural Network

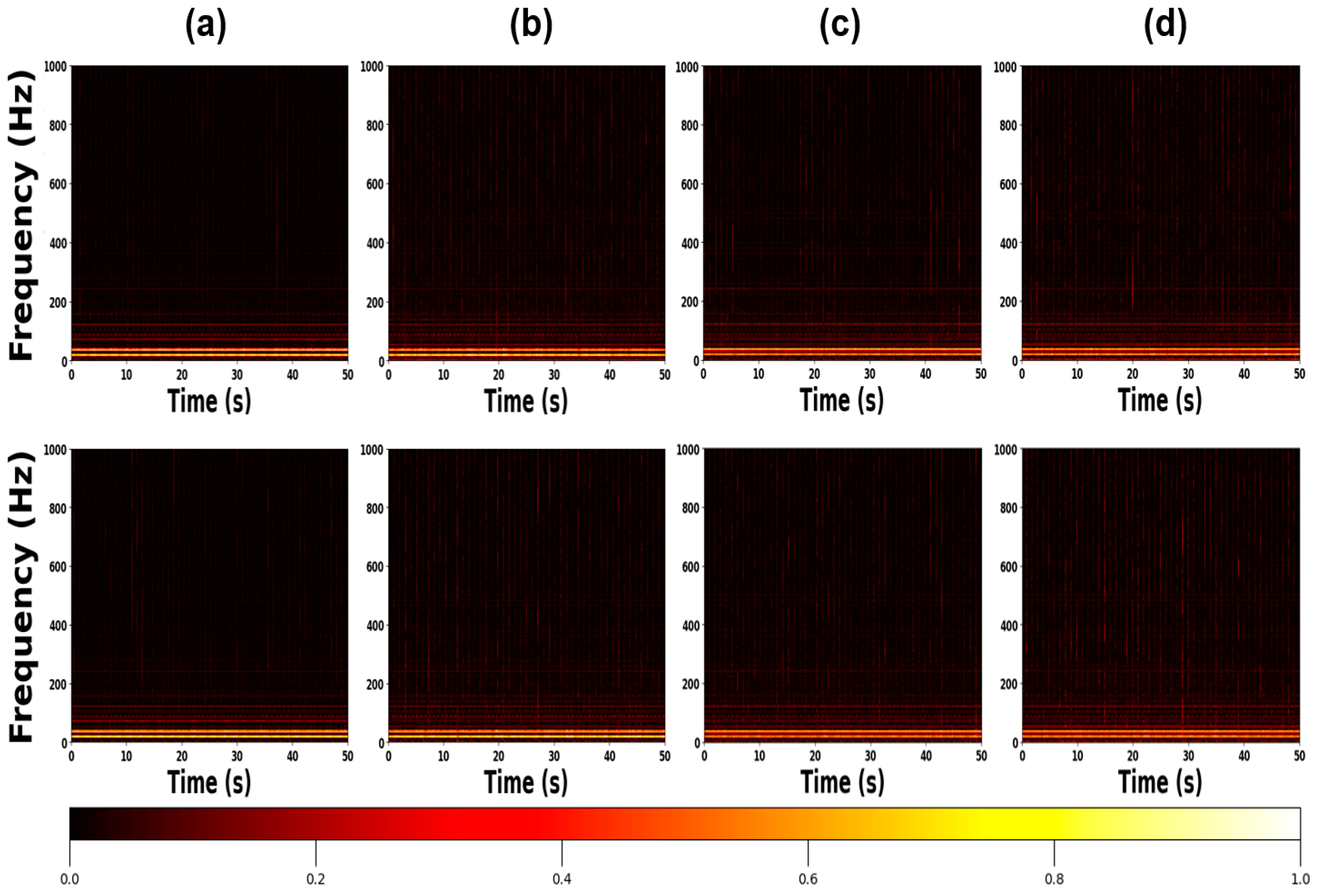

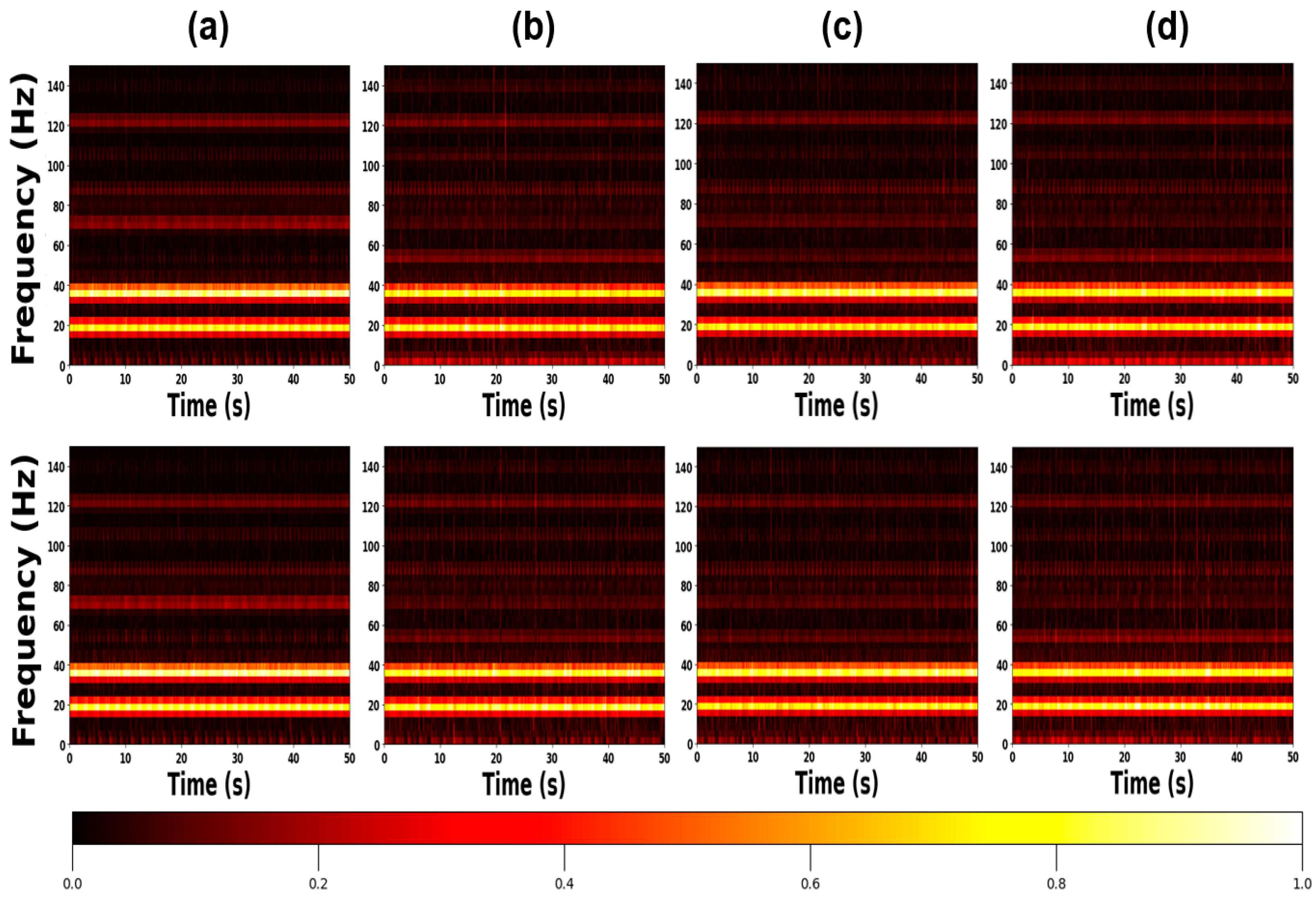

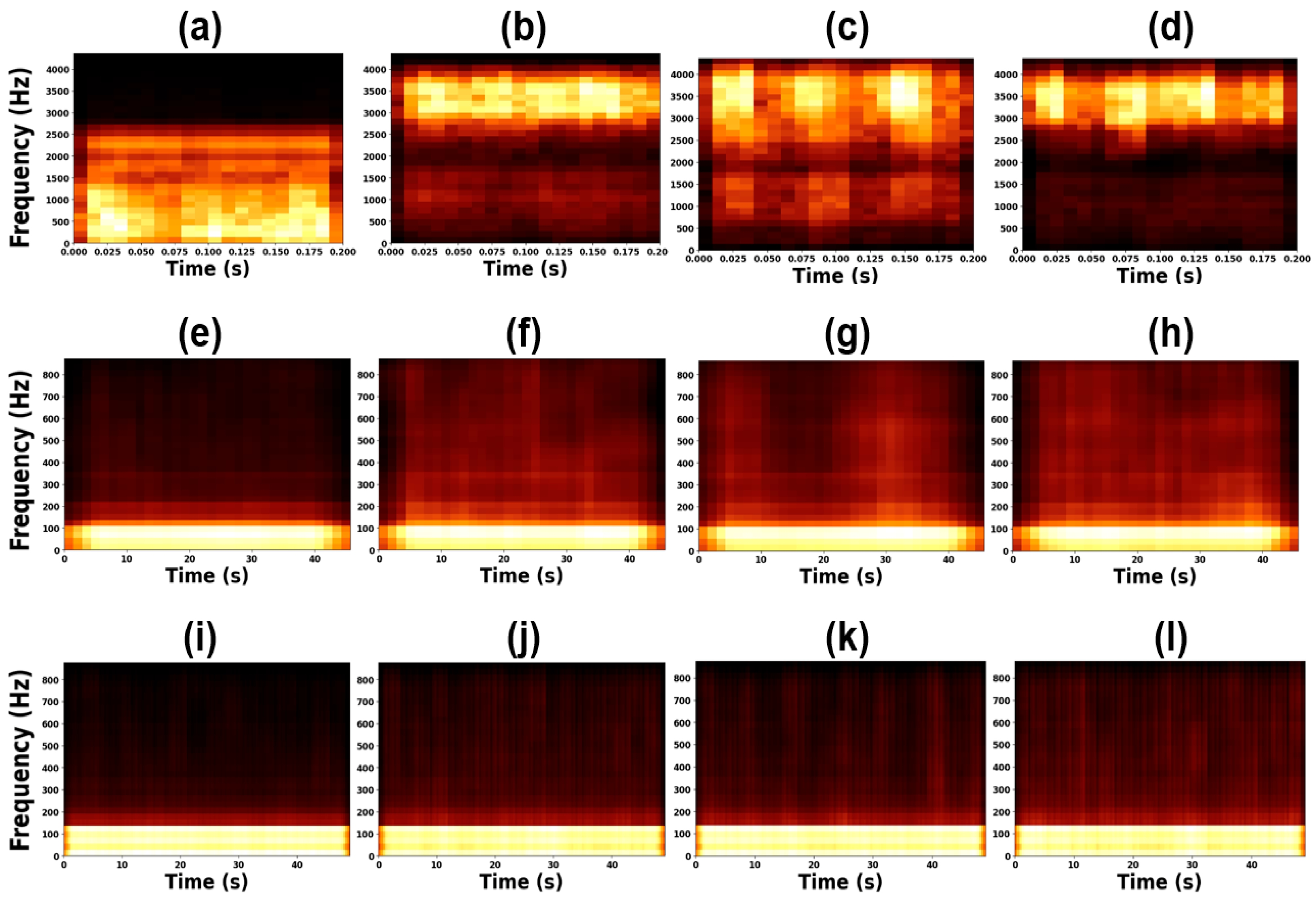

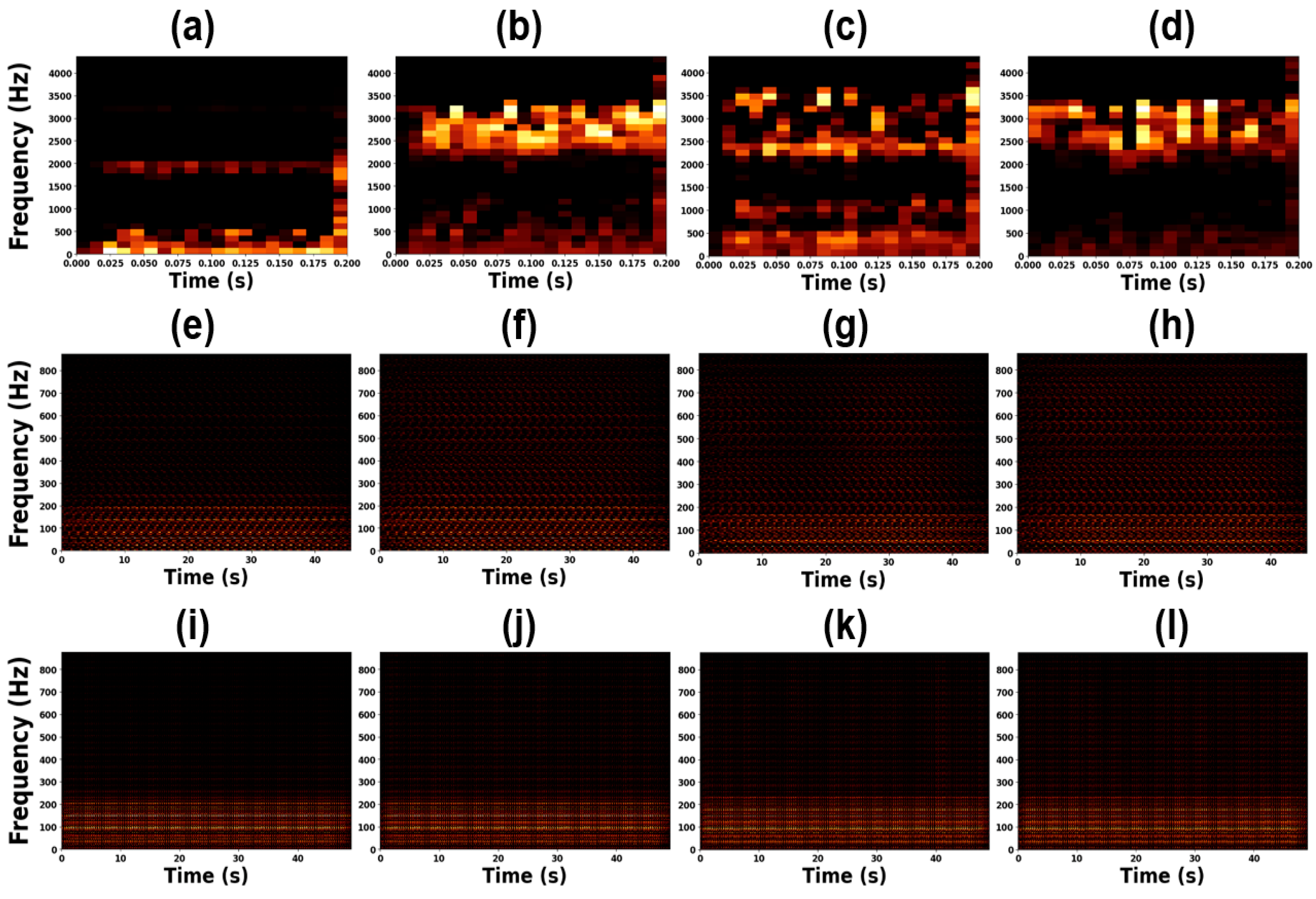

2.2. Short-Time Fourier Transform

2.3. Long Short-Term Memories

2.4. Handcrafted Features

3. Datasets

3.1. Benchmark Dataset

3.2. Experimental Setup

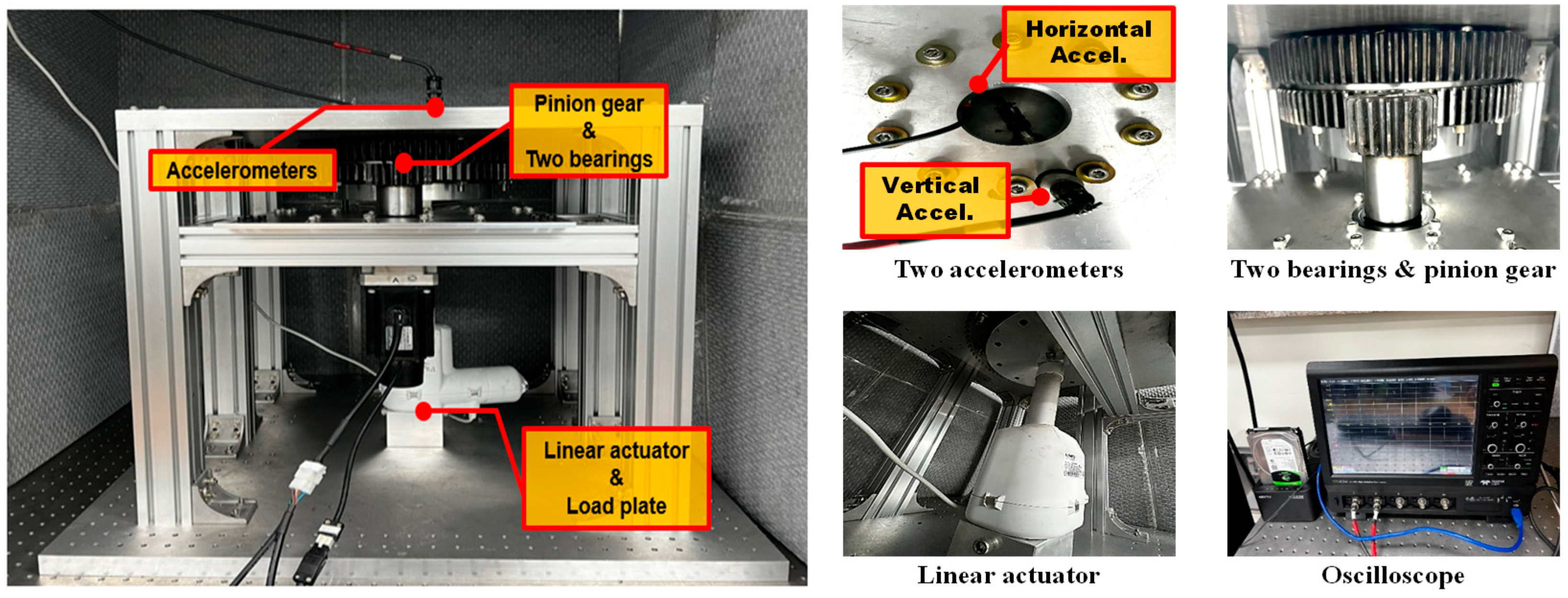

3.2.1. Test Setup Configuration

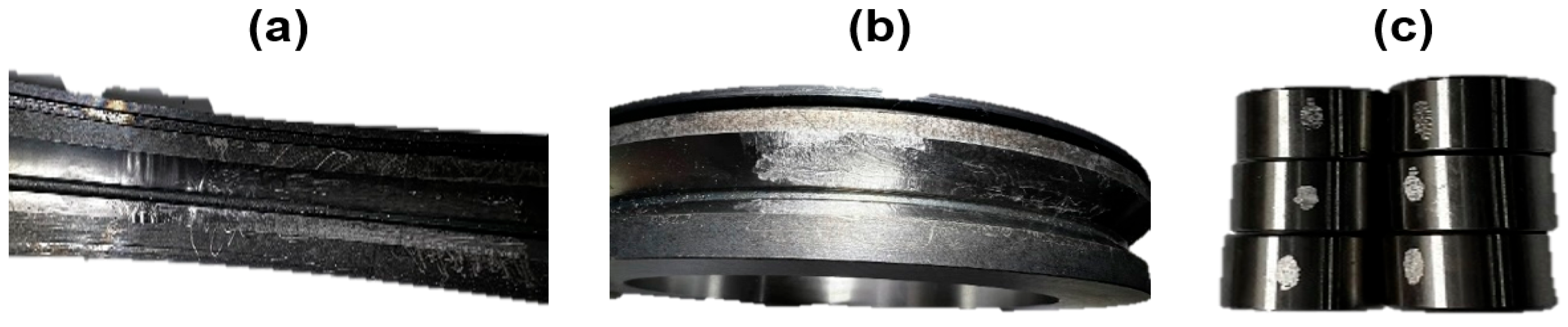

3.2.2. Slightly Defected Bearings

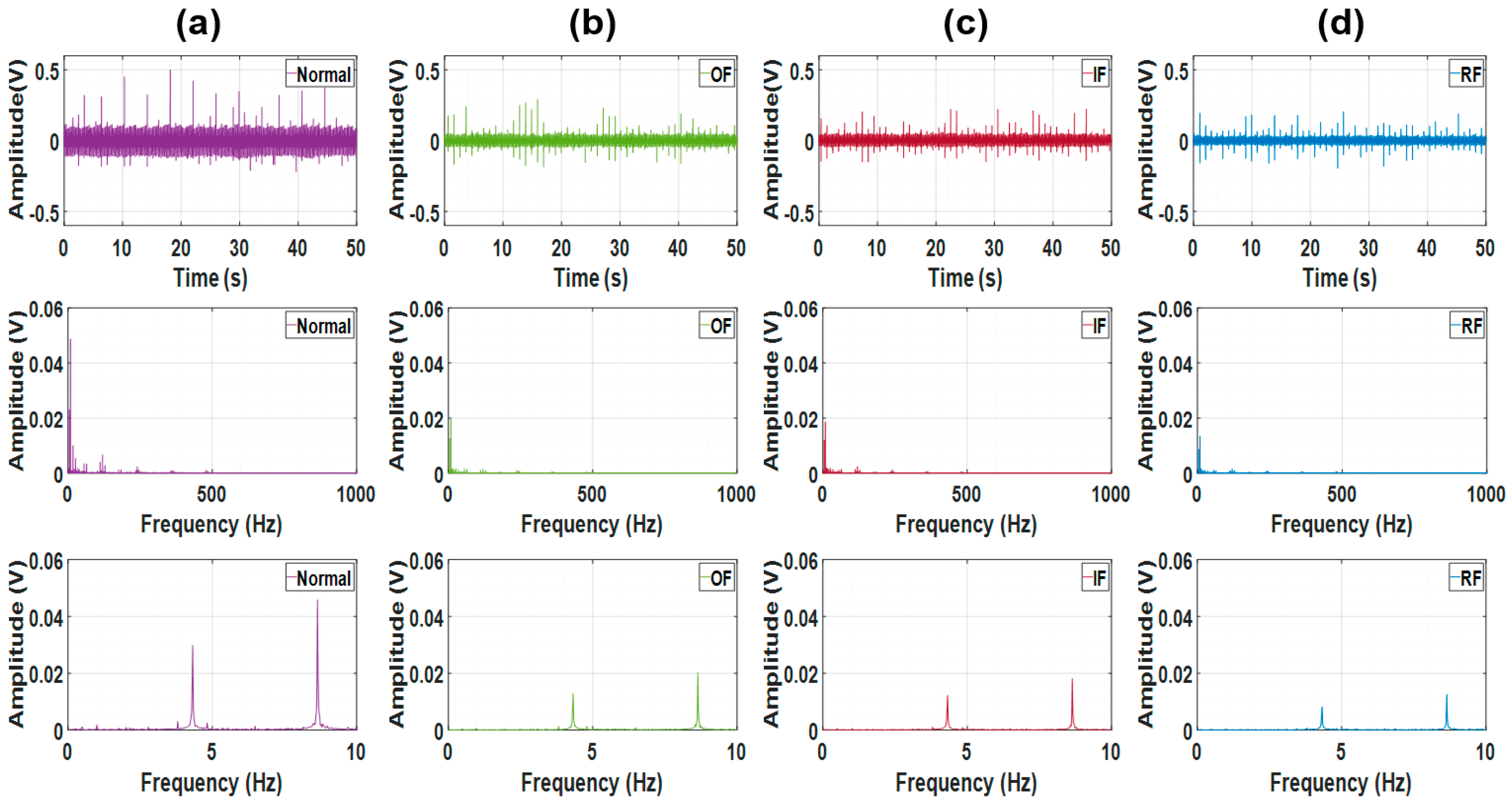

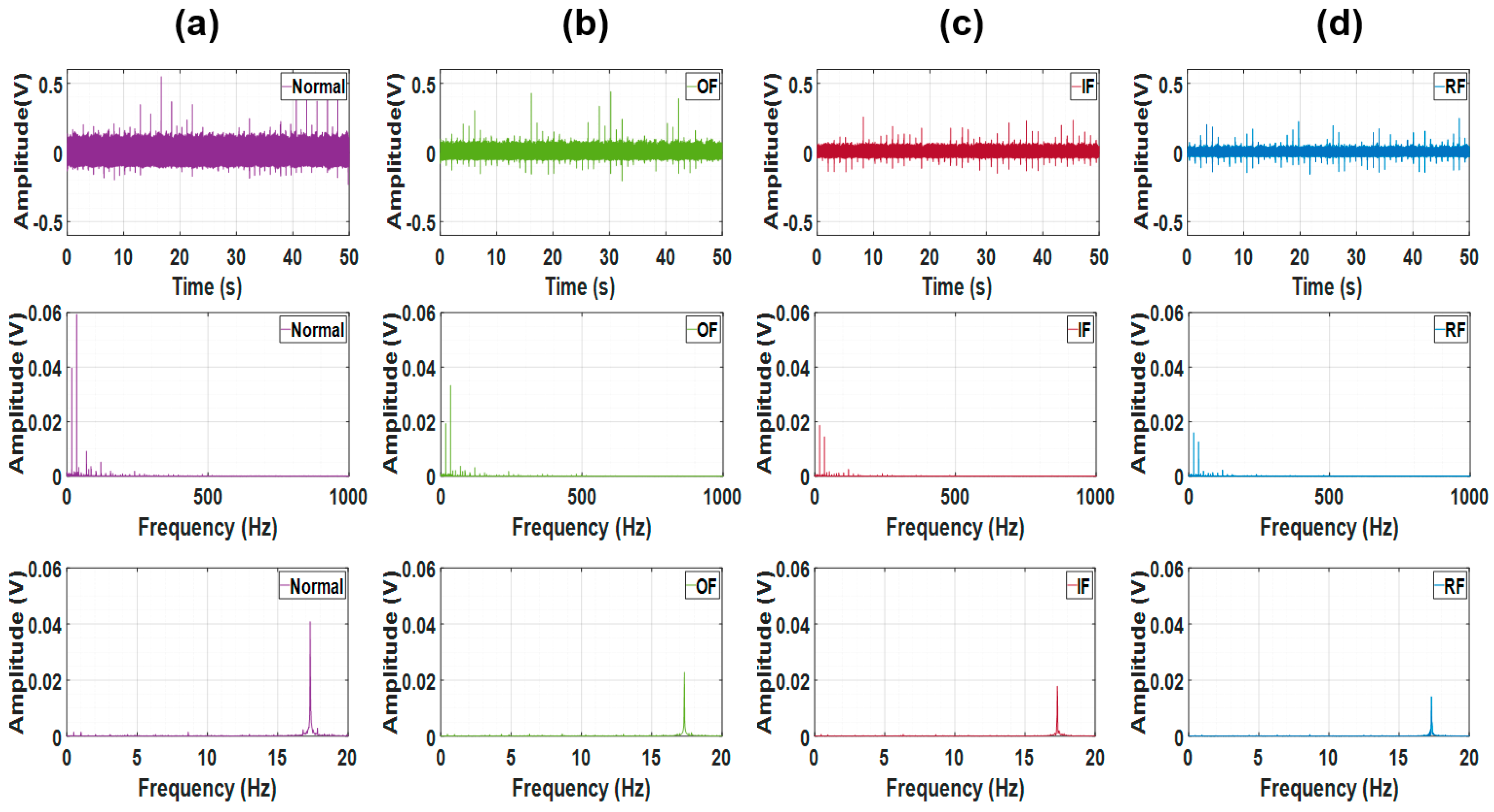

3.2.3. Data Acquisition

| Dataset | RPM | Failure Mode | Training Size | Validation Size | Test Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. A | 5 | Normal, OF, IF and RF | 240 | 3080 | 3080 |

| Exp. B | 20 | Normal, OF, IF and RF | 240 | 3080 | 3080 |

| Dataset 1 | Dataset 2 | Dataset 3 | Dataset 4 | Exp. A | Exp. B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rolling element frequency | 135 Hz | 138 Hz | 139 Hz | 141 Hz | 1.6 Hz | 6.5 Hz |

| Outer pass frequency | 103 Hz | 105 Hz | 106 Hz | 107 Hz | 2.5 Hz | 9.8 Hz |

| Inner pass frequency | 155 Hz | 158 Hz | 160 Hz | 162 Hz | 2.6 Hz | 10.4 Hz |

| 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 688 | 190 | |

| 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 2344 | 586 | |

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 1656 | 396 |

4. Validation

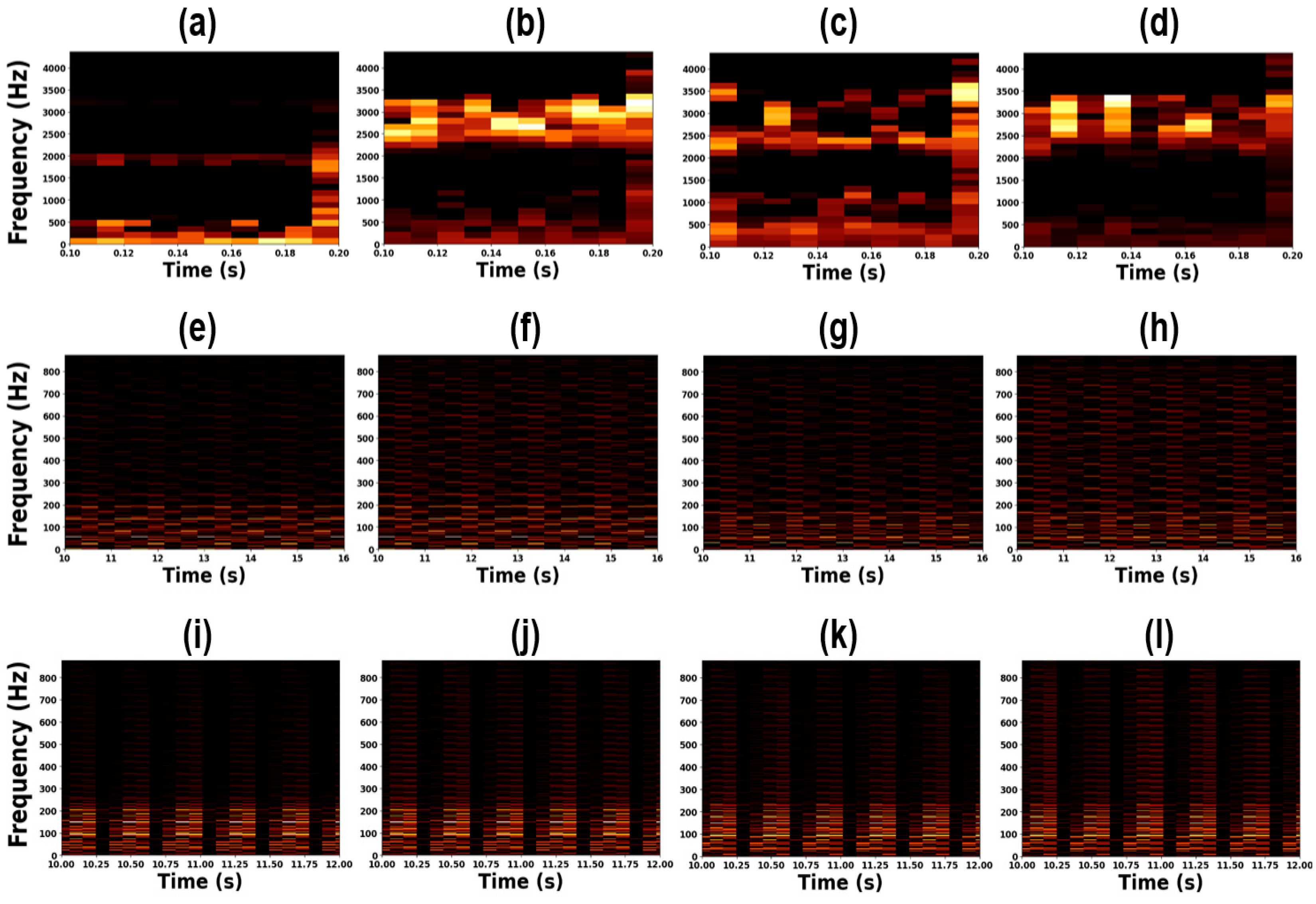

4.1. Preprocessing

4.2. Interpretable Model Design for Comparative Analysis

4.2.1. CNN–STFT

4.2.2. LSTM–Handcrafted

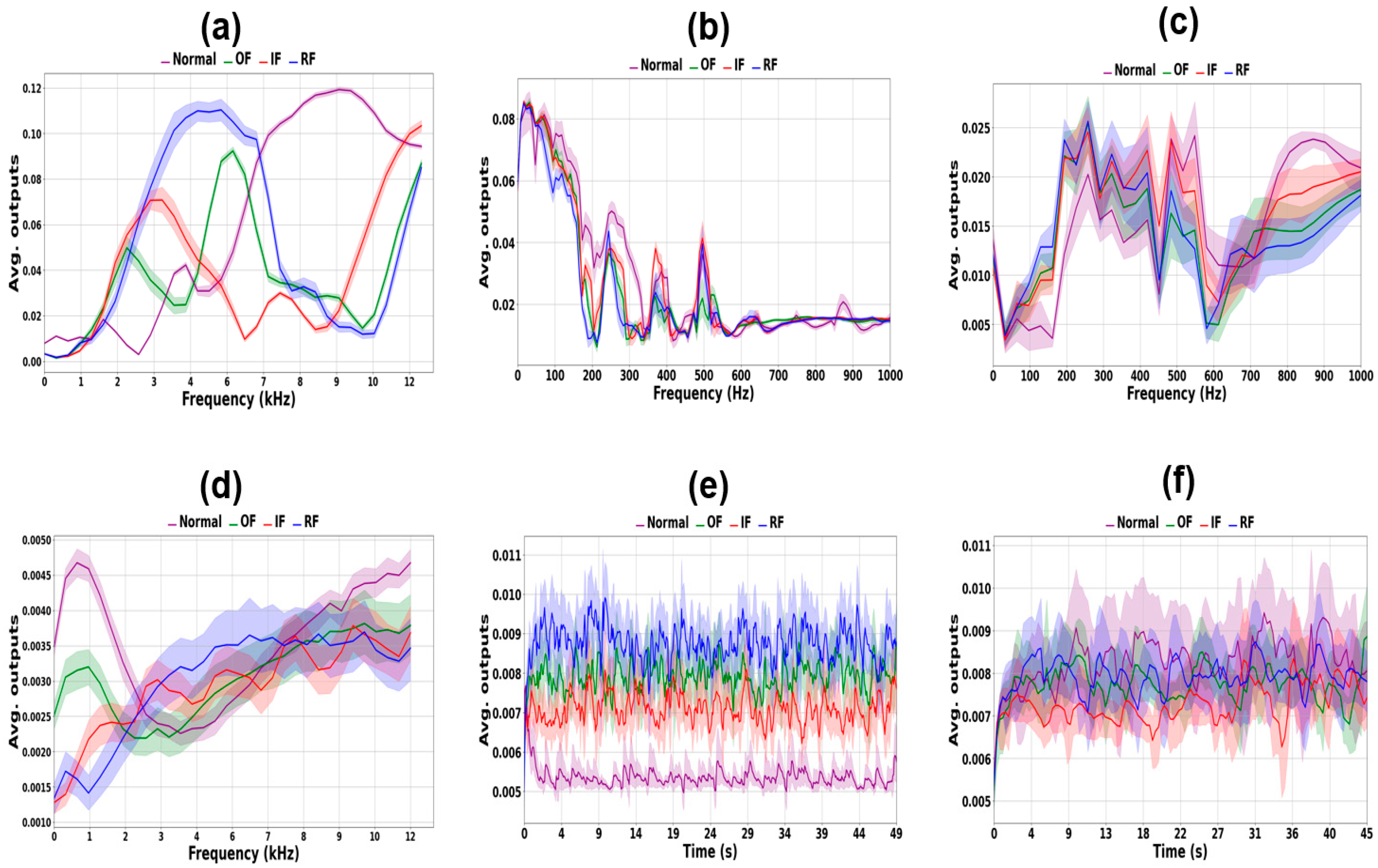

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SKF. Slewing Bearings. Available online: https://cdn.skfmediahub.skf.com/api/public/0901d196809590fe/pdf_preview_medium/0901d196809590fe_pdf_preview_medium.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2005).

- NSK. Technical Report. Available online: https://www.nsk.com/tools-resources/technical-report/ (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Peng, B.; Bi, Y.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M.; Wan, S. A survey on fault diagnosis of rolling bearings. Algorithms 2022, 15, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, L.; Zong, Z.; Gao, H.; Qian, M.; Chen, Z. Dynamic modeling and analysis of rolling bearings with rolling element defect considering time-varying impact force. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 526, 117820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Han, H.; Chen, P. Failure prediction, monitoring and diagnosis methods for slewing bearings of large-scale wind turbine: A review. Measurement 2021, 172, 108855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Bhosle, S. Analysis of vibration signals caused by ball bearing defects using time-domain statistical indicators. Int. J. Adv. Technol. Eng. Explor. 2022, 9, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebold, M.; Mcclintic, K.; Campbell, R.; Byington, C.; Maynard, K. Review of vibration analysis methods for gearbox diagnostics and prognostics. In Proceedings of the 54th Meeting of the Society for Machinery Failure Prevention Technology, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 1–4 May 2000; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Mclnerny, S.A.; Dai, Y. Basic vibration signal processing for bearing fault detection. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2003, 46, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiral, Z.; Karagulle, H. Vibration analysis of rolling element bearings with various defects under the action of an unbalanced force. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2006, 20, 1967–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocak, H.; Loparo, K. Estimation of the running speed and bearing defect frequencies of an induction motor from vibration data. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2004, 18, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Mathew, J.; Ma, L. Vibration feature extraction techniques for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery: A literature survey. In Proceedings of the 10th Asia-Pacific Vibration Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 12–14 November 2003; pp. 801–807. [Google Scholar]

- Saruhan, H.; Saridemir, S.; Qicek, A.; Uygur, I. Vibration analysis of rolling element bearings defects. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2014, 12, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapangowda, N.; Krishna, H.; Vasanth, S.; Thammaiah, A. Internal combustion engine gearbox bearing fault prediction using J48 and random forest classifier. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2023, 13, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, A.; Bertani, S. Mechanical fault detection in a medium-sized induction motor using stator current monitoring. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers 2005, 20, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesarendra, W. Vibration and Acoustic Emission-Based Condition Monitoring and Prognostic Methods for Very Low Speed Slew Bearing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Caesarendra, W.; Kosasih, P.; Tieu, A.; Moodie, C.; Choi, B. Condition monitoring of naturally damaged slow speed slewing bearing based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2013, 27, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesarendra, W.; Park, J.; Kosasih, P.; Choi, B. Condition monitoring of low speed slewing bearings based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition method. Trans. Korean Soc. Noise Vib. Eng. 2013, 23, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žvokelj, M.; Zupan, S.; Prebil, I. Multivariate and multiscale monitoring of large-size low-speed bearings using ensemble empirical mode decomposition method combined with principal component analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2010, 24, 1049–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Tan, A. Fault feature extraction of low speed roller bearing based on teager energy operator and CEEMD. Measurement 2019, 138, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesarendra, W.; Kosasih, B.; Tieu, A.; Moodie, C. Circular domain features based condition monitoring for low speed slewing bearing. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2014, 45, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesarendra, W.; Kosasih, B.; Tieu, A.; Moodie, C. Application of the largest Lyapunov exponent algorithm for feature extraction in low speed slew bearing condition monitoring. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2015, 50, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zheng, S. Fault Diagnosis method of rolling bearing based on MSCNN-LSTM. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 79, 4395–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, W.; Guo, J. Research on a bearing fault diagnosis method based on a CNN-LSTM-GRU model. Machines 2024, 12, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yu, Q.; Chen, S.; Lin, J. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on CNN-LSTM with FFT and SVD. Information 2024, 15, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Q.; Chai, Y.; Huang, X. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis method base on periodic sparse attention and LSTM. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 12044–12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Ren, M. DWT-LSTM-based fault diagnosis of rolling bearings with multi-sensors. Electronics 2021, 10, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, K.; He, Q.; Wang, X.; Xie, Z. Research on fault diagnosis of highway Bi-LSTM based on attention mechanism. Eksploat. I Niezawodn.-Maint. Reliab. 2023, 25, 162937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, J.; Xing, J. A frequency feature extraction method based on convolutional neural network for recognition of incipient fault. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 24, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Deng, L. An intelligent fault diagnosis method of rolling bearings based on short-time Fourier transform and convolutional neural network. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2023, 23, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yang, P.; Yu, H.; Bai, J.; Feng, W.; Su, Y.; Si, Y. A 2DCNN-RF model for offshore wind turbine high-speed bearing-fault diagnosis under noisy environment. Energies 2022, 15, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ai, Q.; Lou, P.; Hu, J.; Yan, J. A novel method for rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on Gramian angular field and CNN-ViT. Sensors 2024, 24, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzawi, S.; Mohammed, T.; Albawi, S. Understanding of a convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Engineering Technology (ICET), Antalya, Turkey, 21–23 August 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Q.; Yang, Y. Bearing fault diagnosis with parallel CNN and LSTM. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2024, 21, 2385–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.-X.; Wei, S.-L.; Xie, C.-L.; Zeng, T.; Sun, J.-W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Fan, F.-L. Bearing PGA-Net: A Lightweight and deployable bearing fault diagnosis network via decoupled knowledge distillation and FPGA Acceleration. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 73, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaria, J.; Fadhel, M.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, F.; Tan, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, G.; Luo, S.; Zeng, A. Multi-scale quaternion CNN and BiGRU with cross self-attention feature fusion for fault diagnosis of bearing. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 086138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulevome, D.K.B.; Qiu, M.; Cao, F.; Opoku-Mensah, E. Evaluation of time-frequency representations for deep learning-based rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Innov. 2025, 15, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protas, E.; Bratti, J.; Gaya, J.; Drews, P.; Botelho, S. Visualization methods for image transformation convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 30, 2231–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S. Mechanical Vibrations; Pearson/Prentice Hall: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, D. The Discrete Fourier Transform: Theory, Algorithms and Applications; World Scientific: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.; Rabiner, L. A unified approach to short-time Fourier analysis and synthesis. Proc. IEEE 1977, 65, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Wei, Y. A deep learning-based method for bearing fault diagnosis with few-shot learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 7516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudemeyer, R.; Morris, E. Understanding LSTM—A tutorial into long short-term memory recurrent neural networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.09586. [Google Scholar]

- Zargar, S. Introduction to Sequence Learning Models: RNN, LSTM, GRU. Preprint, 2021; 37988518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Error accumulation in recurrent neural networks: Analysis and mitigation for time-series prediction. Neural Netw. 2023, 165, 505–519. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Tan, Z.; Chen, H. Limitations of recurrent architectures for long-horizon sequence modeling: An empirical study. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, C.; Tao, Y.; Zhu, T.; Deng, Z. Short-term load forecasting based on deep learning bidirectional LSTM neural network. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, K. A pre-trained model selection for transfer learning of remaining useful life prediction of grinding wheel. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 35, 2295–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesarendra, W.; Tjahjowidodo, T. A review of feature extraction methods in vibration-based condition monitoring and its application for degradation trend estimation of low-speed slew bearing. Machines 2017, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case Western Reserve University Bearing Dataset. Available online: https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Pietrzak, P.; Wolkiesicz, M. Stator winding fault detection of permanent magnet synchronous motors based on the short-time Fourier transform. Power Electron. Drives 2022, 7, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Rosero, J.; Espinosa, A.; Romeral, L. Detection of demagnetization faults in permanent-magnet synchronous motors under nonstationary conditions. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, J.; Ortega, J.; Urresty, J.; Cárdenas, J.; Romeral, L. Stator short circuits detection in PMSM by means of higher order spectral analysis (HOSA). In Proceedings of the 2009 Twenty-Fourth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, Washington, DC, USA, 15–19 February 2009; pp. 964–969. [Google Scholar]

- Belbali, A.; Makhloufi, S.; Kadri, A.; Abdallah, L.; Seddik, Z. Mathematical Modelling of a 3-Phase Induction Motor; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.; Randall, R. Rolling element bearing diagnostics using the Case Western Reserve University data: A benchmark study. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2015, 64, 100–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iunusova, E.; Gonzalez, M.K.; Szipka, K.; Archenti, A. Early fault diagnosis in rolling element bearings: Comparative analysis of a knowledge-based and a data-driven approach. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 35, 2327–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhan, D.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Vincent, P. Visualizing higher-layer features of a deep network. Univ. Montr. 2009, 1341, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, T.A.; Kotzalas, M.N. Rolling Bearing Analysis: Essential Concepts of Bearing Technology, 5th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

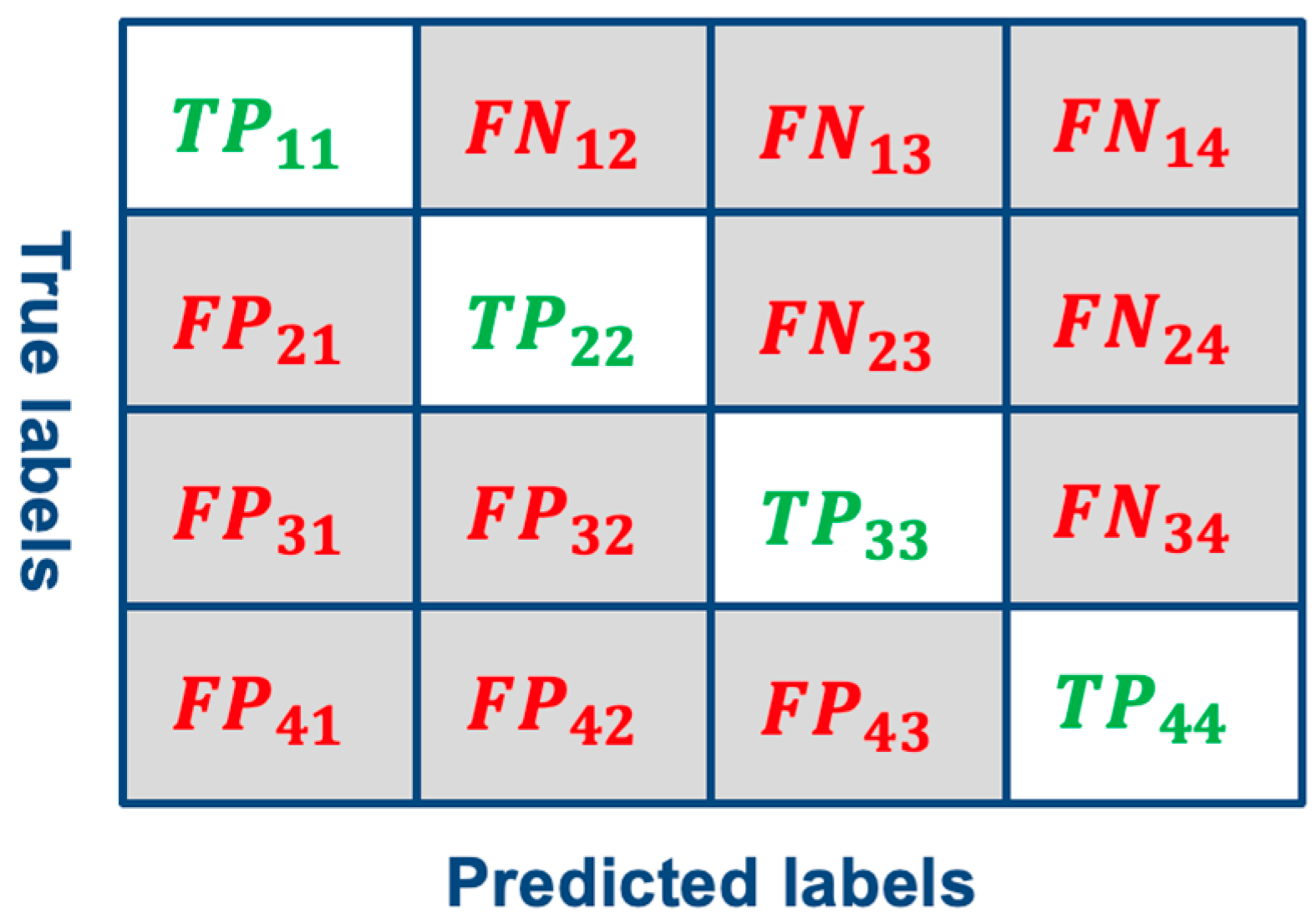

- Grandini, M.; Bagli, E.; Visani, G. Metrics for multi-class classification: An overview. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.05756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Jo, H.; Ban, S. Lite and efficient deep learning model for bearing fault diagnosis using the CWRU dataset. Sensors 2023, 23, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Liang, B.; Cheng, Y.; Meng, D.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T. Deep model based domain adaptation for fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 2296–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yang, B.; Zio, E.; Chen, X. Artificial intelligence for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery: A review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 165, 108376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Zhou, N.; Shi, C. Surrogate modeling of pantograph–catenary system interactions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhou, N.; Wang, Z. CFFsBD: A Candidate Fault Frequencies-based Blind Deconvolution. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3506412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Mei, G.; Zhang, W.; Peng, H.; Tian, G. An improved envelope spectrum via candidate fault frequency optimization-gram. J. Sound Vib. 2022, 523, 116746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature Name | Formula |

|---|---|

| Mean: | |

| Mean amplitude: | |

| Root mean square: | |

| Square root amplitude: | |

| Peak to peak: | |

| Standard deviation: | |

| Kurtosis: | |

| Skewness: | |

| Crest factor: | |

| Shape factor: | |

| Clearance factor: | |

| Entropy: |

| Dataset | RPM | Failure Mode | Training Size | Validation Size | Test Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1 | 1730 | Normal, OF, IF and RF | 40 | 281 | 281 |

| Dataset 2 | 1750 | Normal, OF, IF and RF | 40 | 281 | 281 |

| Dataset 3 | 1773 | Normal, OF, IF and RF | 40 | 281 | 281 |

| Dataset 4 | 1797 | Normal, OF, IF and RF | 40 | 231 | 231 |

| Exp. A STFT | Exp. A Handcrafted | Exp. B STFT | Exp. B Handcrafted | CWRU STFT | CWRU Hand- crafted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input size | (1024, 128) | (128, 12) | (256, 512) | (512, 12) | (32, 32) | (32, 12) |

| Exp. A | Exp. B | CWRU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel size (, , ) | (256, 16, 64) | (64, 31, 64) | (8, 5, 64) |

| Striding interval (, ) | (32, 4) | (8, 4) | (1, 1) |

| Number of parameters | 262,208 | 127,040 | 2624 |

| Exp. A | Exp. B | CWRU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of hidden units | 250 | 172 | 20 |

| Number of parameters | 263,000 | 127,008 | 2640 |

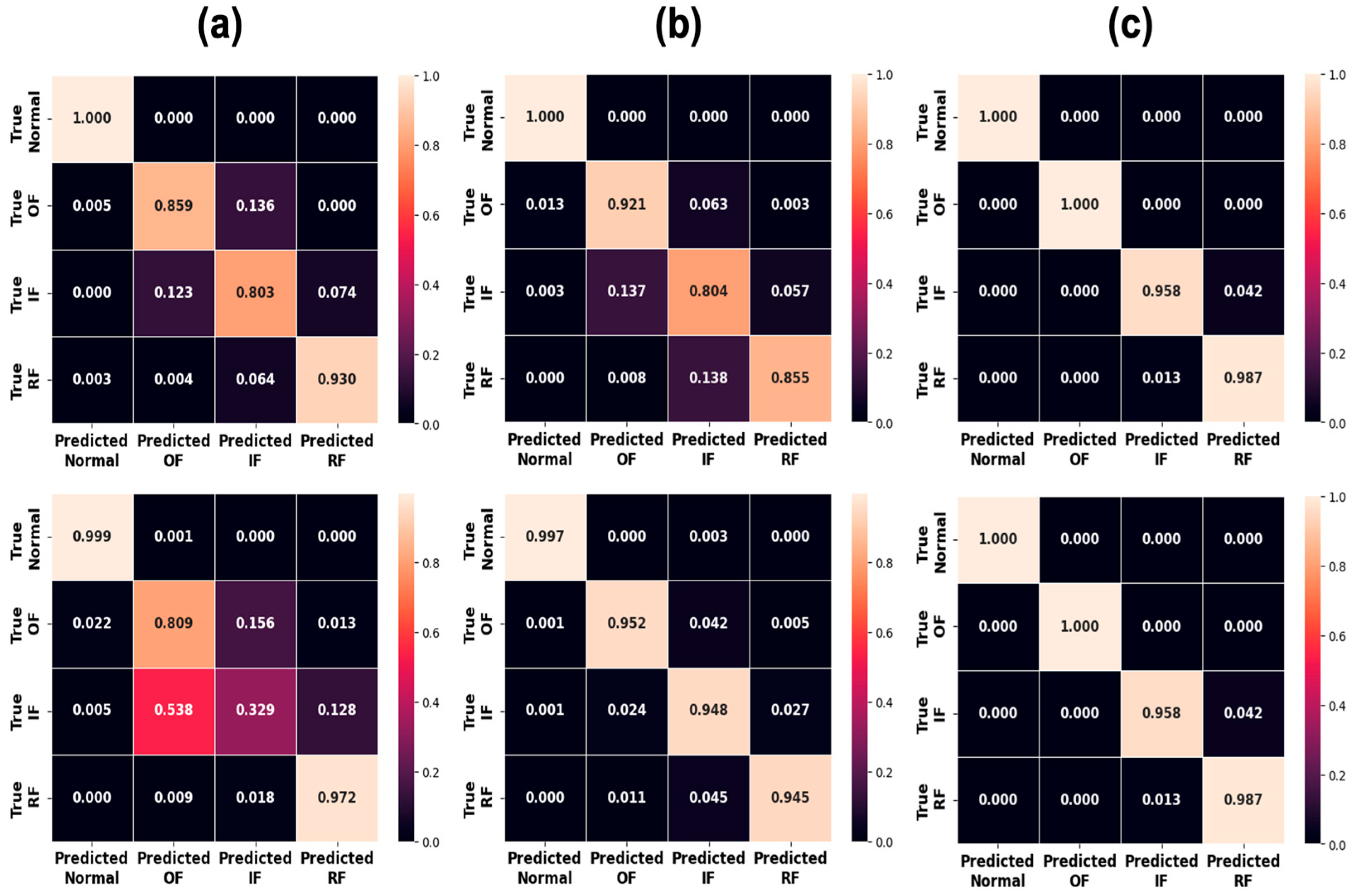

| Dataset 1 (Acc./F1) | Dataset 2 (Acc./F1) | Dataset 3 (Acc./F1) | Dataset 4 (Acc./F1) | Exp. A (Acc./F1) | Exp. B (Acc./F1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 0.92/0.92 | 0.91/0.91 | 0.91/0.90 | 0.92/0.92 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.99/0.99 |

| LSTM-T | 0.80/0.79 | 0.80/0.80 | 0.81/0.81 | 0.80/0.80 | 0.90/0.90 | 0.78/0.76 |

| LSTM-F | 0.99/0.99 | 0.99/0.99 | 0.99/0.99 | 1.0/1.0 | 0.90/0.90 | 0.96/0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, J.-W.; Lee, J.-H.; Son, D.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; Park, K.-S. Comparative Analysis of CNN and LSTM for Bearing Fault Mode Classification and Causality Through Representation Analysis. Lubricants 2026, 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010012

Kim J-W, Lee J-H, Son D-H, Choi S-H, Park K-S. Comparative Analysis of CNN and LSTM for Bearing Fault Mode Classification and Causality Through Representation Analysis. Lubricants. 2026; 14(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jung-Woo, Jong-Hak Lee, Dong-Hun Son, Sung-Hyun Choi, and Kyoung-Su Park. 2026. "Comparative Analysis of CNN and LSTM for Bearing Fault Mode Classification and Causality Through Representation Analysis" Lubricants 14, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010012

APA StyleKim, J.-W., Lee, J.-H., Son, D.-H., Choi, S.-H., & Park, K.-S. (2026). Comparative Analysis of CNN and LSTM for Bearing Fault Mode Classification and Causality Through Representation Analysis. Lubricants, 14(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14010012