Abstract

This study employs molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the frictional behavior of fullerene nano-additives on Fe-C alloy surfaces under varying loads and temperatures, focusing on boundary lubrication conditions. The results show that the x-direction friction force exhibits minimal sensitivity to normal pressure due to the high rigidity of fullerene molecules, which limits variations in real contact area and atomic interactions. In contrast, temperature has a significant effect: as it rises, enhanced atomic vibrations and thermal activation lower energy barriers for sliding. The coefficient of friction (COF) consistently decreases with both increasing load and temperature, driven by the mechanism of thermally activated motion. Although partial rotational motion from sliding to rolling friction was not explicitly observed in the simulations, the study remains within the sliding-dominated regime, highlighting the importance of temperature over load in controlling friction. A linear relationship between and

yields an average activation energy of ~0.03 eV, supporting a thermally activated friction mechanism. By introducing a composite parameter that combines load and temperature effects, the study provides a predictive framework for modeling friction behavior under thermo-mechanical coupling. These findings enhance the understanding of the friction-reducing capabilities of fullerene additives and offer a foundation for designing advanced nano-lubricants in boundary lubrication systems.

1. Introduction

With the advancement of industrial equipment toward higher loads, higher rotational speeds, and extreme operating temperatures, traditional lubrication systems often become inadequate under boundary or near-dry friction conditions. Owing to their size/surface effects, ability to form localized lubrication films, and participation in interfacial physical or chemical processes, nanoscale lubricant additives have been extensively studied and demonstrated significant friction-reducing and anti-wear performance across various lubrication systems. As a result, they have emerged as a prominent focus in tribology and lubrication engineering research [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Among these, carbon-based nanomaterials—such as graphene, carbon nanotubes, and fullerenes—exhibit unique advantages in improving interfacial lubrication and have been widely explored in base oils, solid lubricants, and composite systems [7,8].

Fullerene C60, a typical “zero-dimensional” carbon nanomaterial [9] features a perfectly spherical molecular geometry, strong intramolecular cohesion, and relatively weak intermolecular interactions. These characteristics make it a promising candidate for acting as a “molecular rolling element” or forming low-shear interfacial films. Its chemical and thermal stability allows C60 molecules to maintain structural integrity within a certain temperature range, enabling lubrication under harsh conditions. Experimental studies have shown that C60 can significantly reduce the COF and wear under high loads. For instance, Ku et al. [10] reported that C60 additives in mineral oil reduced COF by approximately 20% under near-extreme pressure. Similarly, Lee et al. [11] observed a notable increase in extreme pressure welding load upon the addition of C60. However, Zheng et al. [12] found that elevated temperatures may reduce adsorption stability, potentially increasing COF under certain conditions. Ruan et al. [13] observed an exponential decrease in COF with increasing load in boundary lubrication, attributed to a transition from sliding to rolling behavior of C60 at the interface. This rolling mechanism can effectively reduce contact area and shear resistance.

In recent years, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become a powerful tool to study interfacial interactions and friction evolution at the atomic scale, offering deep insights into the behavior of nano-lubricants [14]. Extensive MD work has been conducted on materials such as graphene layers, diamond-like carbon (DLC), and metallic surfaces. Existing MD studies on metallic/alloy contacts primarily focus on mechanical response, adhesion-shear processes, and lubricant molecular adsorption behavior. Ewen et al. [15] reviewed the role of nano-additives such as C60 and carbon nanotubes in sliding, rolling, and thermal/load coupling scenarios. Dmitriev et al. [16] investigated the lubrication behavior and wear mechanisms of C60-reinforced amorphous Fe-C friction films and graphene-modified SiO2 nanocomposites, and demonstrated that the tribological properties of these two materials under extreme pressure and transient thermal shock conditions were comparable to those of nano-lubricated Fe-C alloys. Liang et al. [17] discussed lubrication film instability, molecular deformation, and structural disruption under extreme conditions observed in MD studies. Bhuiyan et al. [18] employed reactive MD to analyze thermally and shear-induced chemical changes in molecular chains or additives, suggesting potential reactivity under high temperature and pressure. Ku et al. [10] also analyzed rolling and sliding of nanoparticles under various loads using MD, while Seo et al. [19] studied the nanomechanical behavior and crystallinity of individual C60 molecules.

Although these studies provide a solid theoretical foundation, systematic atomic-scale investigations on the friction behavior of fullerenes under combined pressure–temperature conditions, especially on high-hardness metal surfaces such as Fe-C carburized layers or carburized steels, remain limited. Quantitative models that accurately describe these mechanisms are still lacking.

To address this gap, the present study employs molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the frictional behavior of fullerene C60 molecules confined between two Fe-C carburized layers under coupled pressure and temperature conditions. The objective is to elucidate the frictional response mechanism and quantify the relationship between COF and external load/temperature. By systematically varying simulation parameters, the study evaluates the frictional behavior of C60 under boundary lubrication. The results demonstrate strong agreement between the observed frictional trends and thermally activated friction theory. Furthermore, a coupled load–temperature friction model is proposed, revealing the excellent lubrication performance and tunability of fullerene additives under extreme conditions. Importantly, this study addresses the gap through three interrelated dimensions: (i) we establish a load–temperature coupled friction model for C60-lubricated interfaces by collapsing MD datasets onto an Arrhenius-type unified variable that integrates temperature and normal load, extending classical thermally activated frameworks to incorporate dual thermo-mechanical control; (ii) we quantitatively determine an approximately constant effective activation energy and corresponding load-dependent activation parameters for C60/Fe-C contacts, thereby yielding a quantitatively rigorous, physically interpretable set of thermo-mechanical descriptors—rather than merely qualitative trends—for predictive engineering applications; and (iii) we demonstrate the utility of this framework for engineering-relevant Fe-C substrates under dry/boundary-contact conditions, defining the operational window in which C60 retains structural integrity and serves as an effective solid lubricant while elucidating the attendant atomic-scale lubrication mechanisms. These elements collectively set apart the current study from prior investigations into fullerene-based lubrication and bridge a key knowledge gap in the thermo-mechanical coupling of such nano-lubricated systems.

2. Simulation Methods

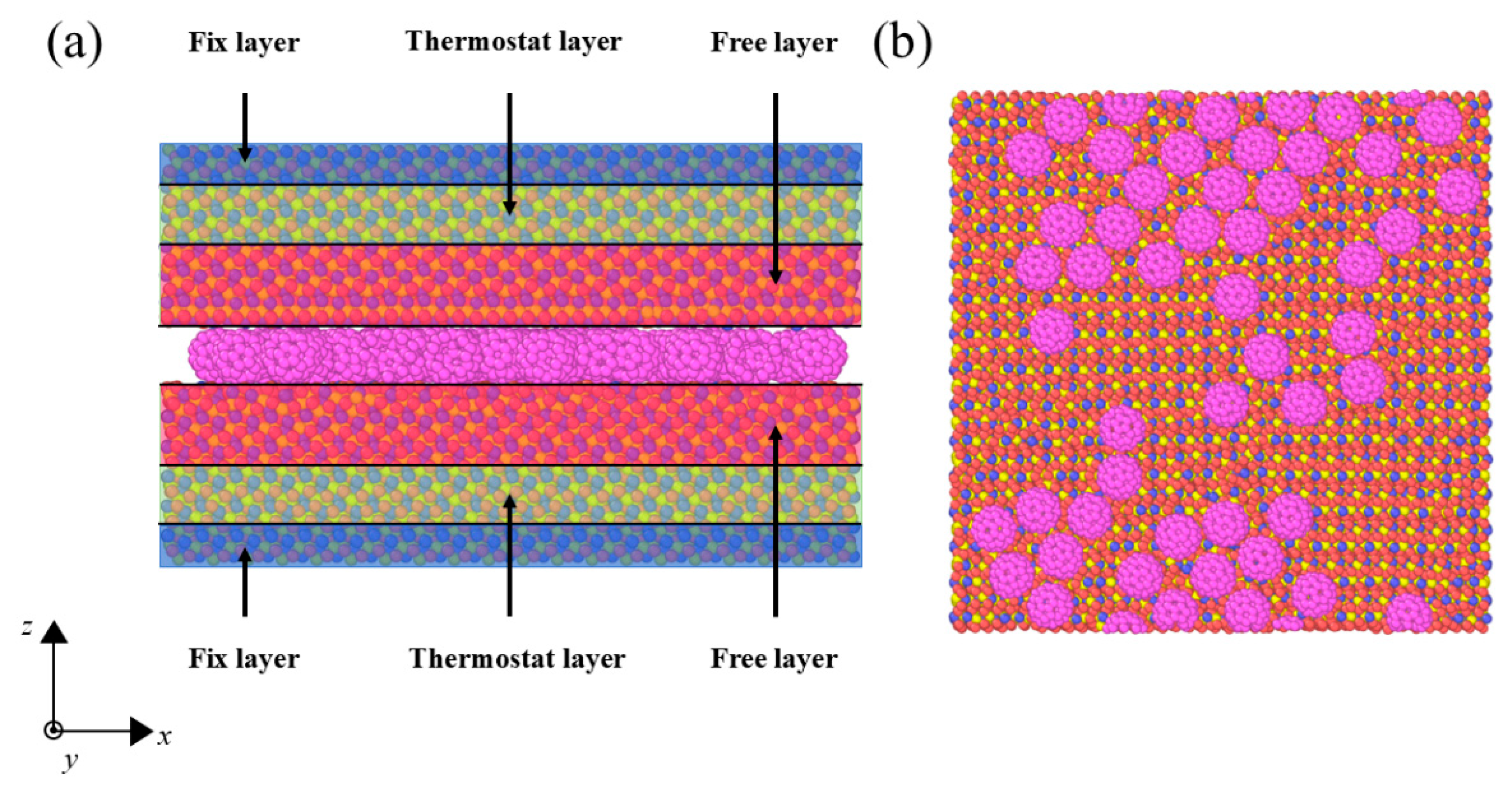

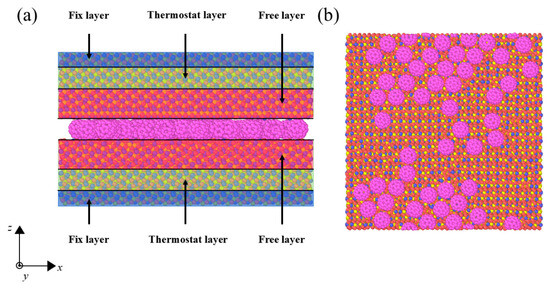

As illustrated in Figure 1, the nanoscale friction model developed in this study consists of two Fe-C carburized substrates, with 50 C60 molecules randomly inserted in the interfacial gap to simulate the distribution behavior of nano-additives within a confined structure. The random packing of C60 molecules was generated using the Packmol algorithm, ensuring a physically reasonable initial configuration. Atomic-scale visualization and structural evolution analyses were conducted using the OVITO software (OVITO 3.14.1) [20]. All simulations are conducted under dry friction conditions; no base oil or liquid lubricant is included, and the C60 molecules act as solid particles in direct contact with the solid substrates.

Figure 1.

The simulation configuration. (a) front view; (b) top view without upper wall.

Classical MD simulations were employed to analyze the frictional interactions between fullerene molecules and the carburized substrate surfaces [21,22,23,24,25,26]. All simulations were performed using the Verlet integration algorithm [27] with a time step of 2 fs [28]. Temperature regulation was implemented using the NVT ensemble (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) [29], with thermostats applied only to regions far from the sliding interface to avoid direct interference with interfacial friction behavior. The interfacial region was left non-thermostatted to ensure that both heat dissipation and temperature rise resulted exclusively from intrinsic frictional processes, without external thermal interference. Specifically, each solid substrate is divided along the surface-normal direction into three functional regions: a fixed layer at the outer side of the block, an intermediate thermostat layer, and a near-surface free layer in direct contact with the C60 molecules (Figure 1a). Atoms in the fixed layer are held rigid to impose mechanical boundary conditions: for the upper substrate, this layer applies the prescribed normal load and drives shear motion at the set sliding velocity, while for the lower substrate, it anchors the block in space to prevent overall system drift. The thermostat layer integrates a Nosé–Hoover thermostat within the NVT ensemble at the target temperature, functioning as a heat sink to dissipate frictional heat generated at the interface. The free layer, un-constrained and not directly coupled to the thermostat, enables realistic atomic behavior: atoms here exchange momentum and energy solely through interactions with neighboring atoms and C60 molecules, allowing natural local deformation at the contact interface without artificial damping. Practically, atoms are assigned to these three regions based on their initial surface-normal positions and retain this grouping throughout the simulation—no additional artificial potentials are employed to enforce the layered structure, as integrity is inherently maintained by interatomic interactions within the substrate. For the Fe-C system visualized in Figure 1b, carbon atoms with distinct local environments or interaction characteristics are designated different atom types, differentiated by three distinct colors. This color-coding scheme facilitates the interpretation of local physical states and interfacial interaction mechanisms [30]. The structural details of the substrate have been clarified: each solid block is divided into a fixed layer, a thermostat layer, and a free layer. For each substrate, the fixed layer contains 2400 atoms (~3 Å), the thermostat layer 12,000 (~10 Å) atoms, and the free layer 14,700 atoms (12 Å).

Periodic boundary conditions are applied in the x (sliding) and y (transverse) directions, whereas the z direction is confined by the two opposing substrates and the C60 layer, as illustrated in Figure 1a. The sliding motion is generated by translating the fixed layer of the upper substrate at a constant velocity of 10 m/s along the x direction. Although this velocity is higher than typical experimental sliding speeds, it is within the standard range for non-equilibrium MD simulations and represents a compromise between achieving a quasi-steady-state sliding interface and maintaining feasible simulation times. Therefore, we primarily focus on the relative dependence of the friction coefficient on temperature and normal load at this sliding rate, rather than on reproducing a specific experimental velocity. In addition, for the units used in our work, it has the following relations with SI units: 1 eV/Å ≈ 1.6 × 10−9 N. 1 eV/Å3 ≈ 1.6 × 1011 Pa ≈ 160 GPa.

During loading, a constant normal force was applied along the negative z-direction on the upper substrate. The system underwent a 200 ps thermal relaxation to reach equilibrium, followed by shear loading with a constant sliding velocity in the positive x-direction for a duration of 2 ns, simulating typical nanoscale frictional behavior.

The interatomic interactions were modeled as follows: the Fe-C interactions were described by the Tersoff/ZBL hybrid potential [31], suitable for capturing bond formation and breaking in Fe-C systems; intramolecular C-C interactions within the fullerene spheres were modeled using the AIREBO potential [32]. and non-bonded van der Waals interactions (including Fe-C in the substrates and C-C between fullerenes and the substrate) were described using the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential [33]. The LJ parameters used in the simulations are as follows: for the Fe-C interaction, the energy parameter ε is 48.955 meV and the distance parameter σ is 3.086 Å; for the C-C interaction, the energy parameter ε is 4.553 meV and the distance parameter σ is 3.851 Å [13].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Verification of Simulation Methods

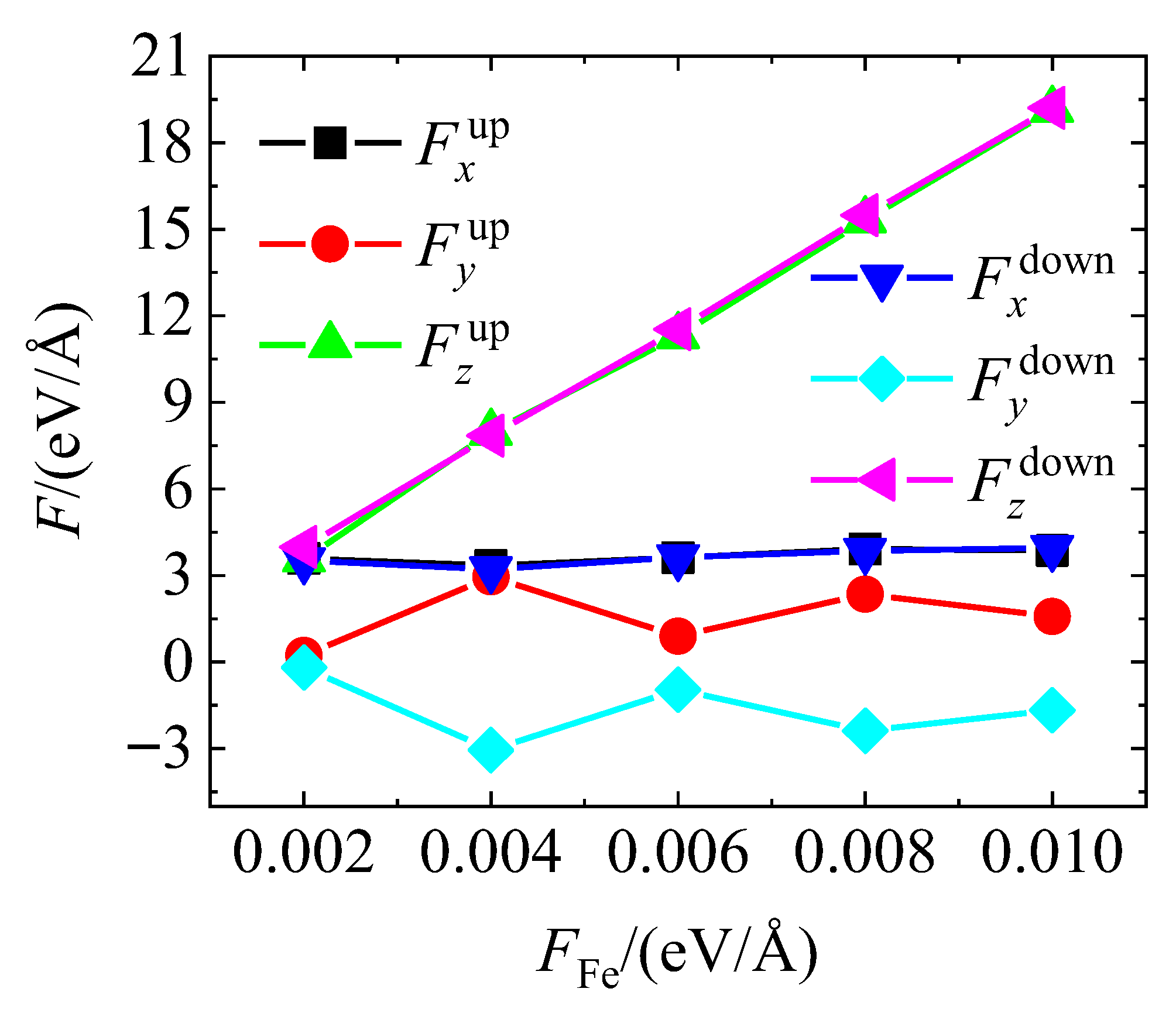

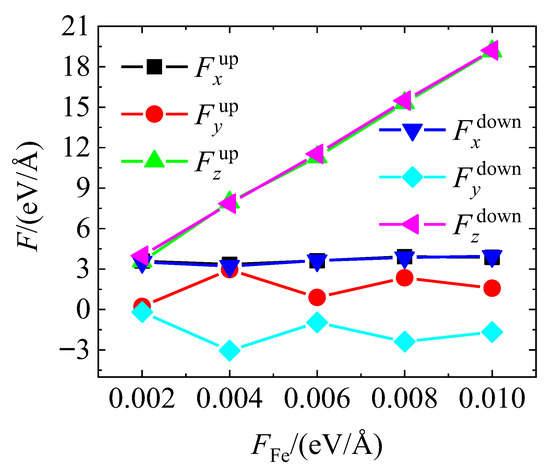

Firstly, interfacial forces acting on the fullerene molecules along the x, y, and z directions were calculated at 300 K, comparing the top and bottom wall interactions, as shown in Figure 2. When a normal load was applied by fixing the upper Fe-C substrate, the force component along the z-direction (Fz) exhibited a nearly linear increase with FFe ranging from approximately 6 eV/Å to over 18 eV/Å. The forces on both the top and bottom substrates were nearly identical, indicating a highly symmetric and pronounced normal force response in the loading direction.

Figure 2.

Force comparison on fullerene balls from top/bottom walls in x-, y- and z-direction at temperature of 300 K.

In contrast, the force components in the sliding direction ( for the upper substrate and for the lower substrate) remained relatively stable at around 3 eV/Å, suggesting consistent and balanced frictional forces during shear. The transverse force on the upper substrate () fluctuated slightly within a narrow range (0–3 eV/Å), while the force on the lower substrate () exhibited slightly negative values, indicating the presence of minor reverse friction or perturbations in the y-direction. However, these disturbances appear to be phase-cancelled overall.

Thus, under 300 K conditions, the calculated forces along the x, y, and z axes demonstrate good consistency and physical plausibility.

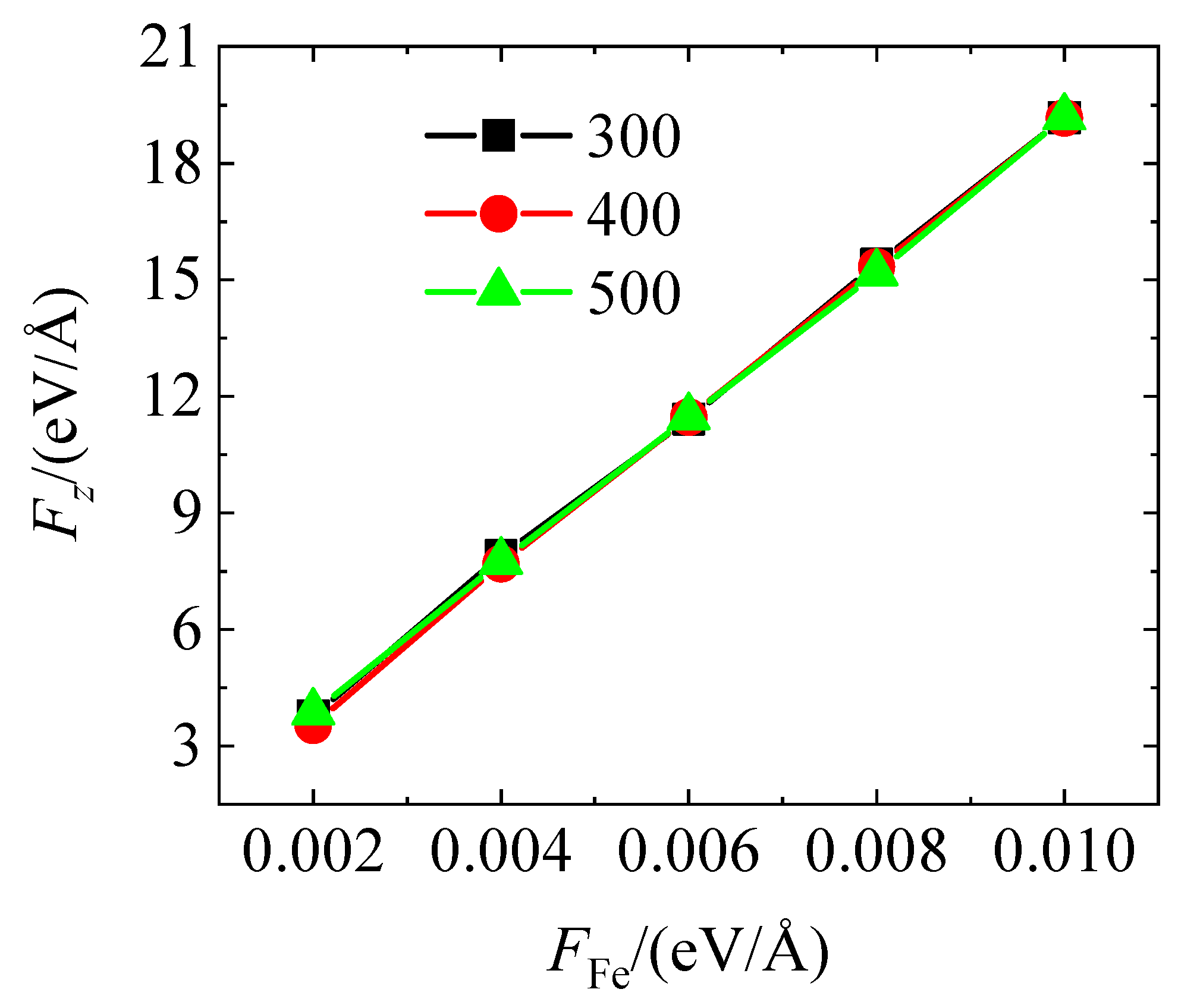

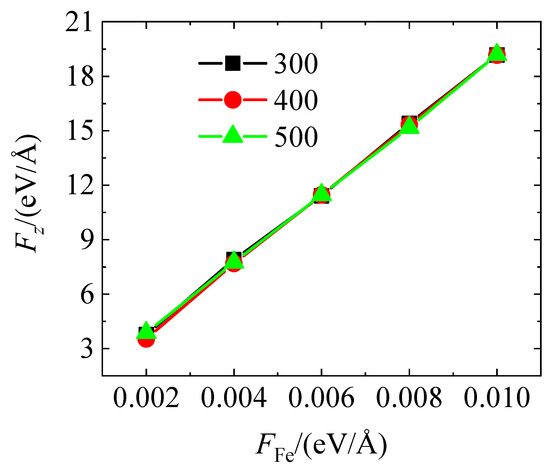

Figure 3 illustrates the correlation between the externally applied force on Fe atoms and the total calculated interaction force between the fullerene molecules and the wall surfaces. The results reveal that under all three temperature conditions, Fez increases linearly and nearly identically with FFe, ranging from approximately 3 eV/Å to 19 eV/Å. This indicates a stable and proportional mechanical response of the system under normal loading.

Figure 3.

The correlation between applied force on Fe atoms and calculated total force between fullerene balls and wall.

The force-load curves at 300 K, 400 K, and 500 K almost completely overlap, suggesting that within this temperature range, the total force in the z-direction is largely insensitive to temperature variations. Therefore, the system’s mechanical behavior in the loading direction is primarily governed by the magnitude of the external load, rather than thermal effects.

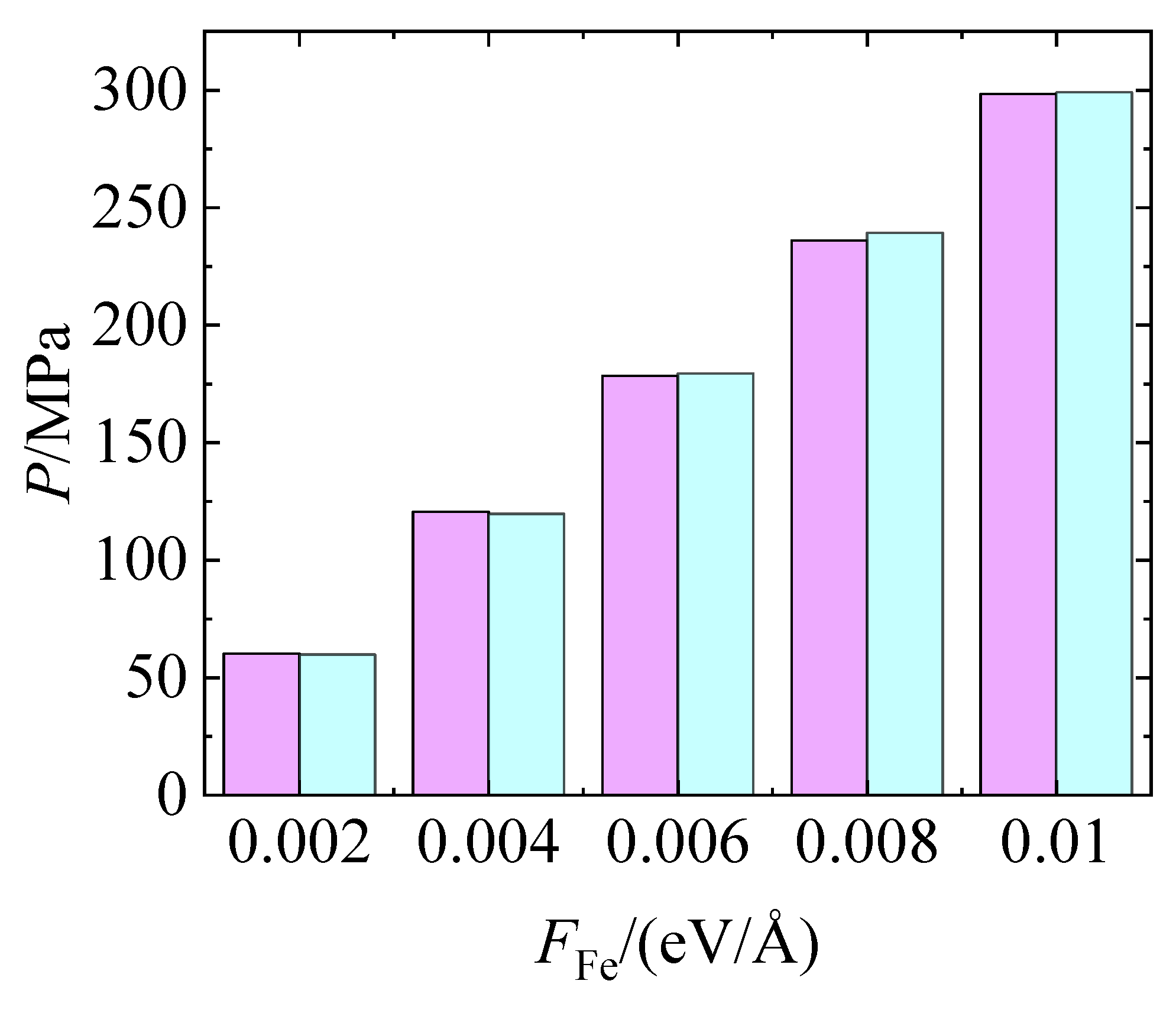

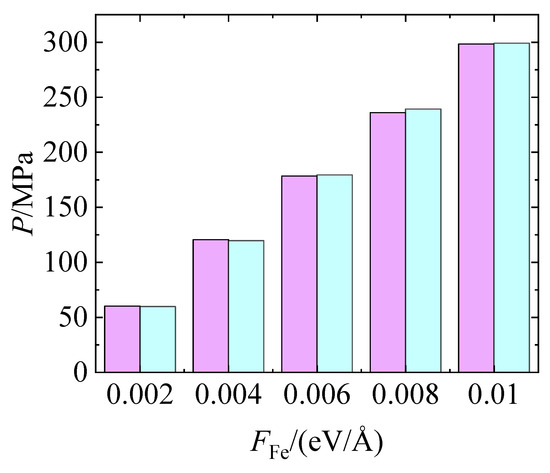

Figure 4 presents a comparison between the FFe obtained from MD simulations and the theoretical stress values calculated from the applied normal load. The heights of the two sets of bars remain remarkably close across all loading levels, indicating that the simulated pressure response accurately reflects the effect of the external load. This strong agreement confirms the physical validity and consistency of the simulation parameter settings.

Figure 4.

The pressure calculated (Cyan) from simulation results and applied (pink).

As FFe increases, both the simulated and theoretical stress values exhibit a linear growth trend, rising from approximately 59.82 MPa to 299.08 MPa, consistent with the behavior expected in the linear elastic regime of the material system.

By calculating the applied loads exerted by the carburized substrates in all spatial directions and the corresponding contact pressure acting on the embedded fullerene molecules, the results demonstrate a high degree of numerical consistency between the two. This agreement indicates that the molecular dynamics simulation method employed in this study offers high feasibility and reliability in modeling the mechanical response of the system.

3.2. Friction Force and Coefficient of Friction at Different Applied Loads and Temperatures

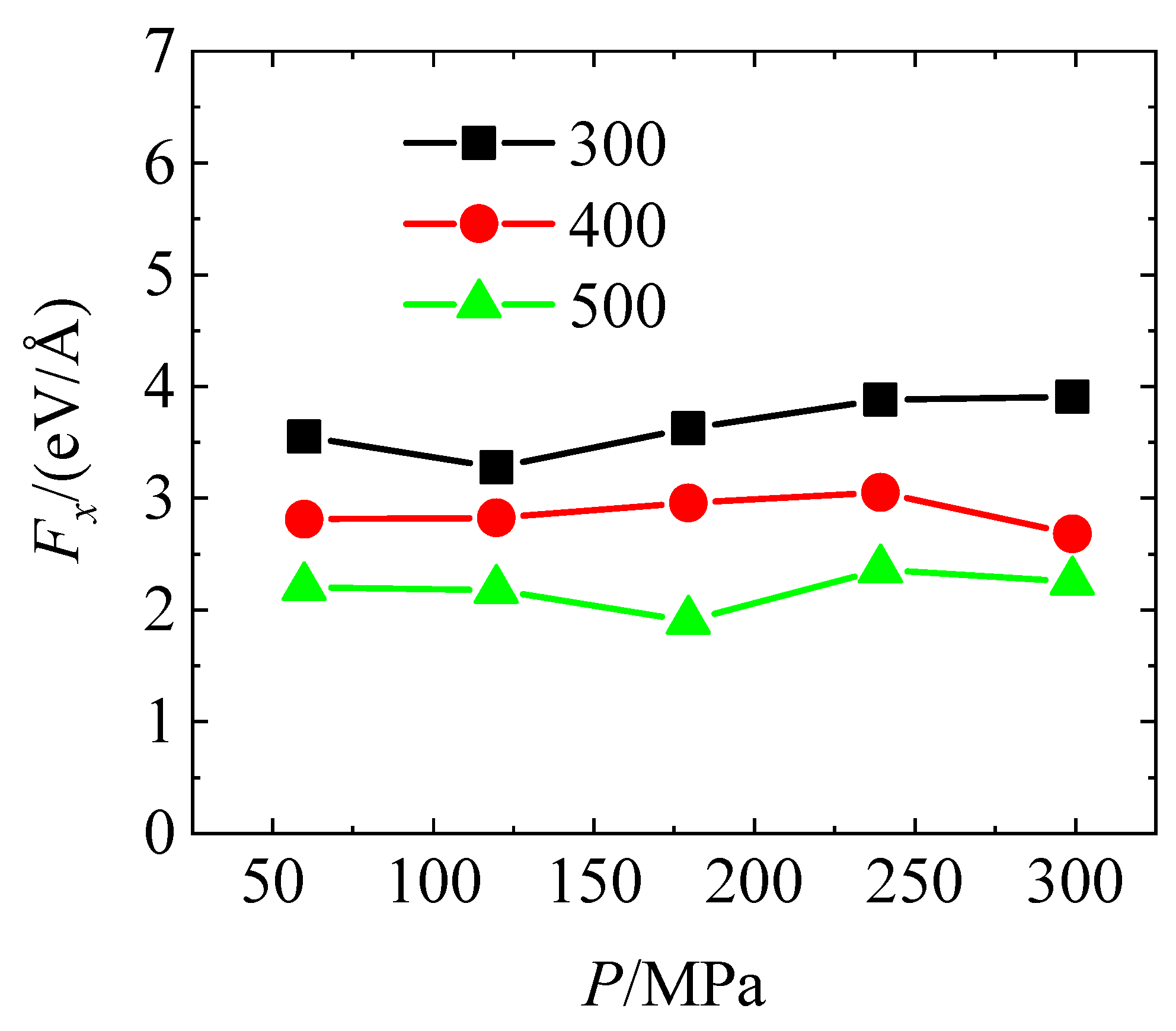

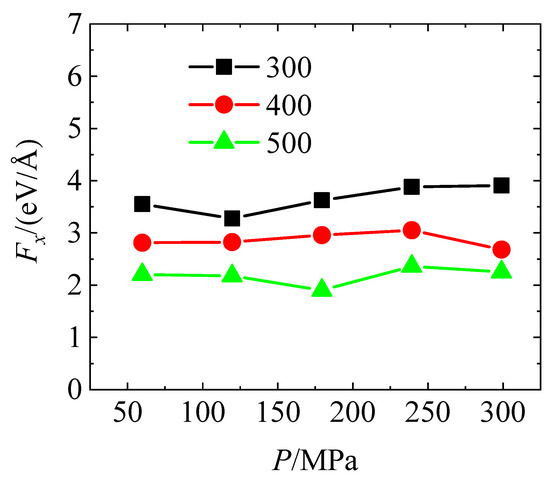

As shown in Figure 5, the variation trend of Fx under different P was calculated at three temperatures: 300 K, 400 K, and 500 K. At 300 K, Fx remains at a relatively high level (approximately 3.5–4.5 eV/Å), representing the highest among all temperature conditions. At 400 K, Fx slightly decreases with reduced fluctuation, while at 500 K, it reaches the lowest level, concentrated in the range of 2–3 eV/Å.

Figure 5.

The friction force at different applied loads and temperatures.

At all temperatures, Fx exhibits no significant monotonic trend with increasing P, but instead shows slight oscillations, indicating that the influence of normal load on sliding friction in the x-direction is relatively weak. This is primarily due to the high rigidity of fullerene molecules, which undergo negligible deformation under pressure. As a result, increasing the normal load does not substantially alter the interfacial contact area or the number of atomic contacts, leading to an insensitive response of Fx to P.

Under high load conditions, partial rotational motion of some fullerene molecules may occur, causing a local transition from sliding to rolling friction [13]. This alters the energy dissipation pathway and leads to more complex frictional behavior, reflected in the non-monotonic, oscillatory pattern of Fx with respect to P.

The simulation results further show that Fx varies more significantly across different temperatures, suggesting that the system’s sliding behavior is primarily driven by thermal effects rather than pressure. As the temperature increases, interfacial atoms gain more thermal energy, which lowers sliding energy barriers and enhances atomic movement, facilitating interfacial slip. This confirms that the frictional behavior is predominantly governed by thermally activated processes rather than direct load control. The enhanced atomic vibrations at elevated temperatures weaken atomic interlocking at the sliding interface, resulting in a notable decrease in Fx, thereby indicating that higher temperatures facilitate reduced sliding resistance and improved lubrication performance.

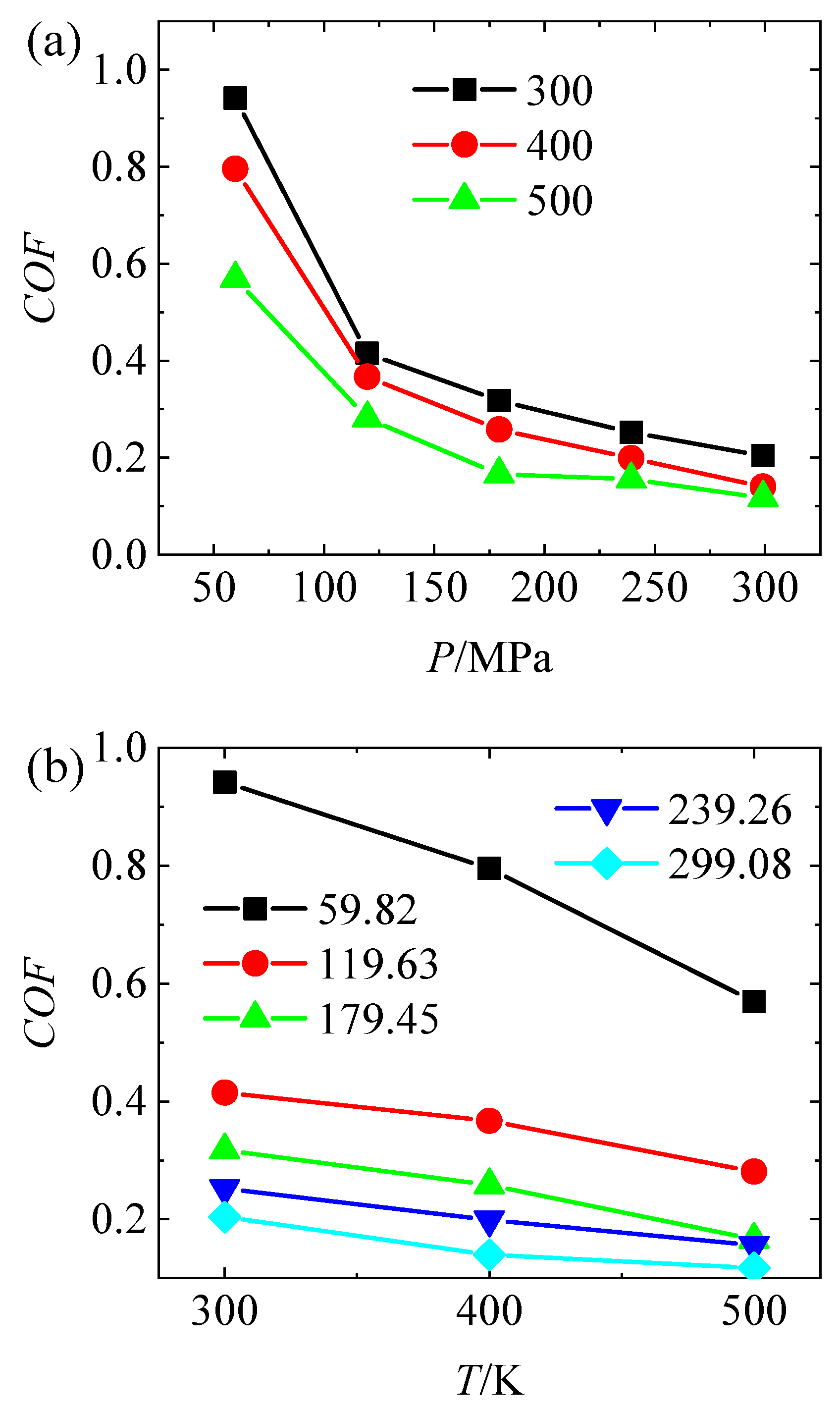

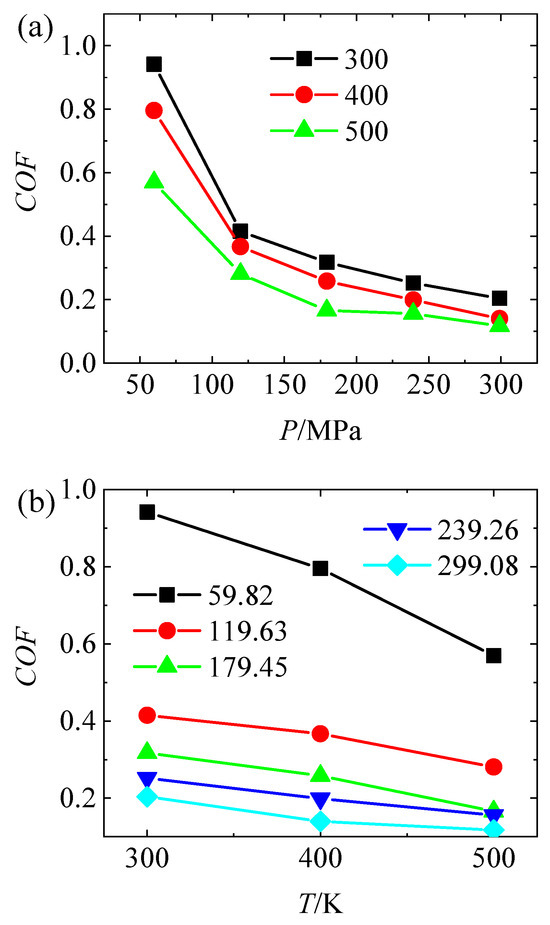

Figure 6a presents the variation in the COF with P at different temperatures (300 K, 400 K, and 500 K). At all three temperatures, the COF exhibits a pronounced decreasing trend with increasing normal pressure. At 300 K, the initial COF is relatively high (approximately 0.9), while at 500 K, it reaches its lowest value (~0.2–0.3), indicating that higher temperatures lead to lower friction coefficients. This result demonstrates that, at a fixed temperature, increasing the normal load effectively reduces interfacial sliding friction.

Figure 6.

Variation in coefficient of friction with (a) applied load at different temperatures and (b) temperature under different applied loads.

Figure 6b shows how the COF varies with T under different normal pressure levels. In all cases, the COF decreases with rising temperature, confirming the dominant role of thermal activation in reducing interfacial resistance. The largest drop in COF occurs under low pressure (59.82 MPa), where thermal effects significantly reduce sliding resistance. Under higher pressure conditions, where the COF is already low, the temperature-induced reduction becomes less pronounced, and the COF trend tends to flatten.

These results collectively reveal that both normal pressure and temperature contribute to friction reduction, but thermal effects become more dominant at lower pressures, while mechanical loading governs frictional behavior more strongly under high-pressure conditions.

From a microscopic perspective, the variation in the COF with respect to normal load and temperature reflects a coupled effect between interfacial contact morphology and atomic-scale energy transfer mechanisms.

At low loads, the actual contact area between fullerene molecules and the carburized substrate is small. The interface is dominated by sliding friction, and frictional energy is primarily dissipated through shear interactions between interfacial atoms. However, due to insufficient atomic vibrational energy at low loads, atoms are unable to overcome local potential energy barriers, leading to enhanced adhesion and hindered interfacial slip—resulting in higher friction resistance.

As the load increases, the potential energy landscape at the interface is modified, stabilizing the interaction between fullerenes and the substrate surface. Atomic interactions at the interface reduce energy dissipation and result in a more uniform shear stress distribution. This promotes smoother interfacial slip and leads to a significant reduction and eventual stabilization of the COF under high-load conditions [8].

Temperature influences friction mainly through thermal activation and potential barrier reduction. As temperature rises, atomic thermal vibrations intensify, and atoms acquire sufficient kinetic energy to overcome local energy barriers more easily. Thermal agitation weakens atomic adhesion and interlocking, thereby reducing sliding friction [34]. Simultaneously, the interfacial potential energy surface becomes partially smoothed, and the energy barrier for atomic motion is lowered, making slip events more frequent and energetically favorable.

Additionally, stronger interfacial thermal motion further facilitates rapid energy migration and redistribution, converting frictional energy more efficiently into internal thermal energy rather than mechanical dissipation [35]. On the microscopic scale, a rise in temperature promotes coordinated sliding between the fullerenes and the substrate, facilitated by thermal activation. This leads to a reduction in energy barriers for sliding. This not only reduces the atomic adhesion barrier but also enhances interfacial lubrication, leading to a notable decrease in COF.

In summary, the system’s frictional behavior is jointly modulated by normal load and temperature, exhibiting multi-scale coupling characteristics. On the other hand, rising temperature alters friction mechanisms via thermal activation—increasing atomic kinetic energy, reducing slip barriers, and facilitating structural reconfiguration and energy dissipation. The synergistic action of both effects leads to a continuous decrease in COF with increasing load and temperature.

3.3. Quantitatively Correlation of Coefficient of Friction with Applied Loads and Temperatures

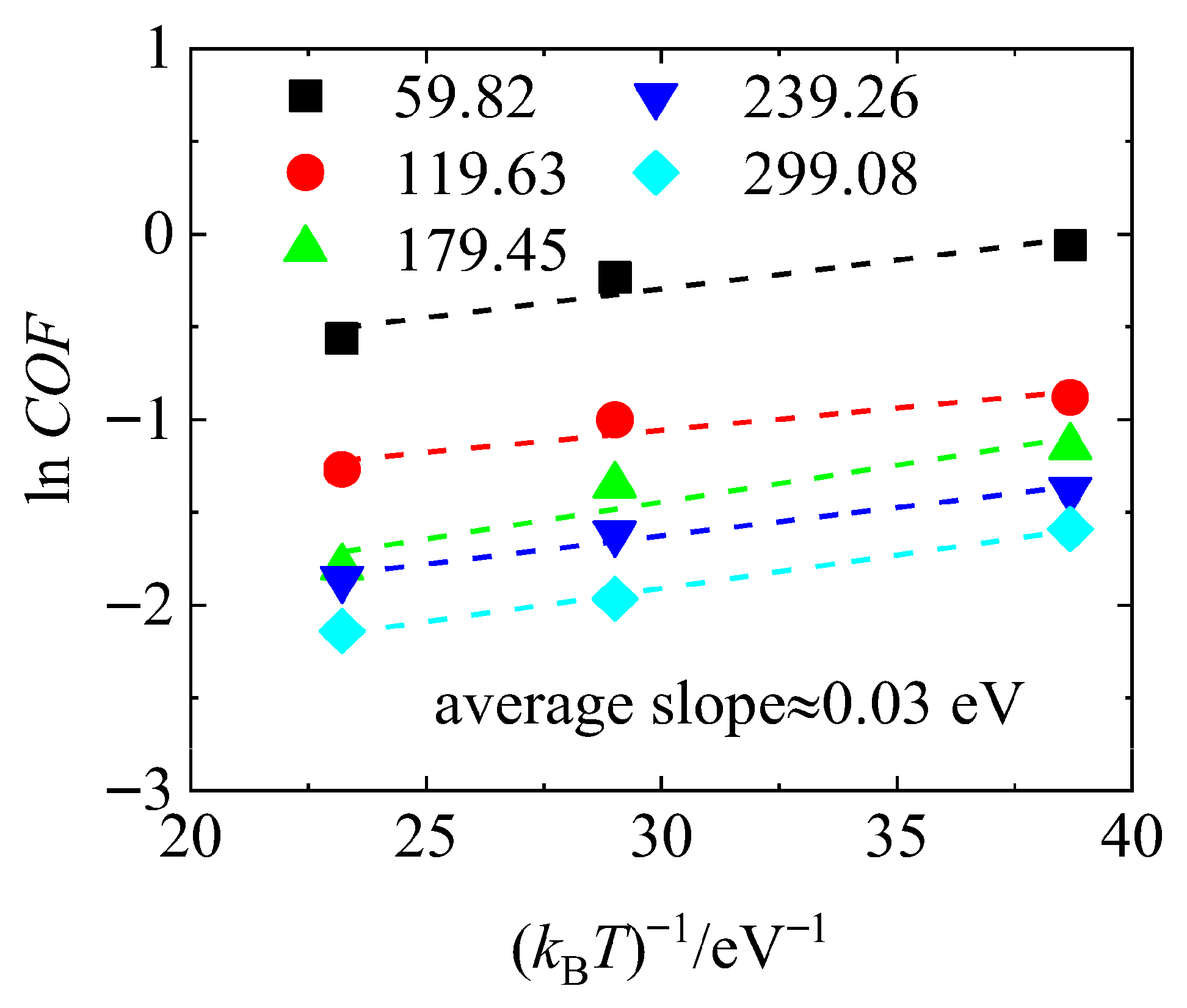

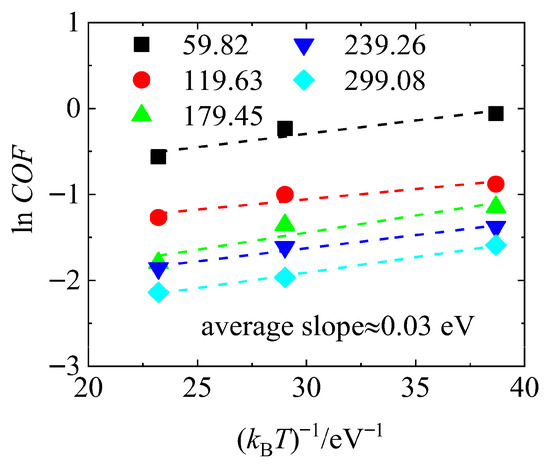

To further elucidate the intrinsic relationship between the COF and both temperature and normal load in the fullerene-based lubrication system, and to validate the applicability of the thermally activated friction theory [36], quantitative calculations and linear fitting analyses of COF were performed under various loading and temperature conditions. The results are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The coefficient of friction results (marked) at different applied loads and temperatures compared to the thermally activated friction theory (dashed line).

For all applied loads, the plots of versus exhibit a clear linear positive correlation, where T is the temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The slopes of these linear fits are nearly identical across all load levels, with an average value of approximately 0.03 eV, indicating a consistent activation energy for thermally activated friction processes under different pressures. This suggests that the interfacial energy barrier and frictional mechanisms remain similar despite changes in normal load.

Additionally, as the normal pressure increases, all fitting lines shift downward, reflecting an overall decrease in COF, which aligns with the trend observed previously in Figure 6a.

These fitting results provide further confirmation that the frictional behavior of the simulation system adheres to classical thermally activated friction theory. The low activation energy indicates that the system’s interfacial atoms can more easily overcome local energy barriers as temperature increases, which is beneficial for friction reduction at elevated temperatures. Moreover, the consistent thermal response under varying loads reflects the structural stability of the interfacial atomic configuration, reinforcing the reliability of fullerene additives under coupled thermo-mechanical conditions.

In nanoscale lubrication studies, the COF is generally influenced by both normal load and temperature. However, their effects are not simply additive, but rather interact through multi-scale coupling mechanisms, including changes in interfacial contact morphology, atomic potential energy distribution, and thermally activated atomic transitions. Therefore, establishing a quantitative model that simultaneously characterizes the synergistic effects of load and temperature is essential for understanding the friction mechanisms under thermo-mechanical coupling.

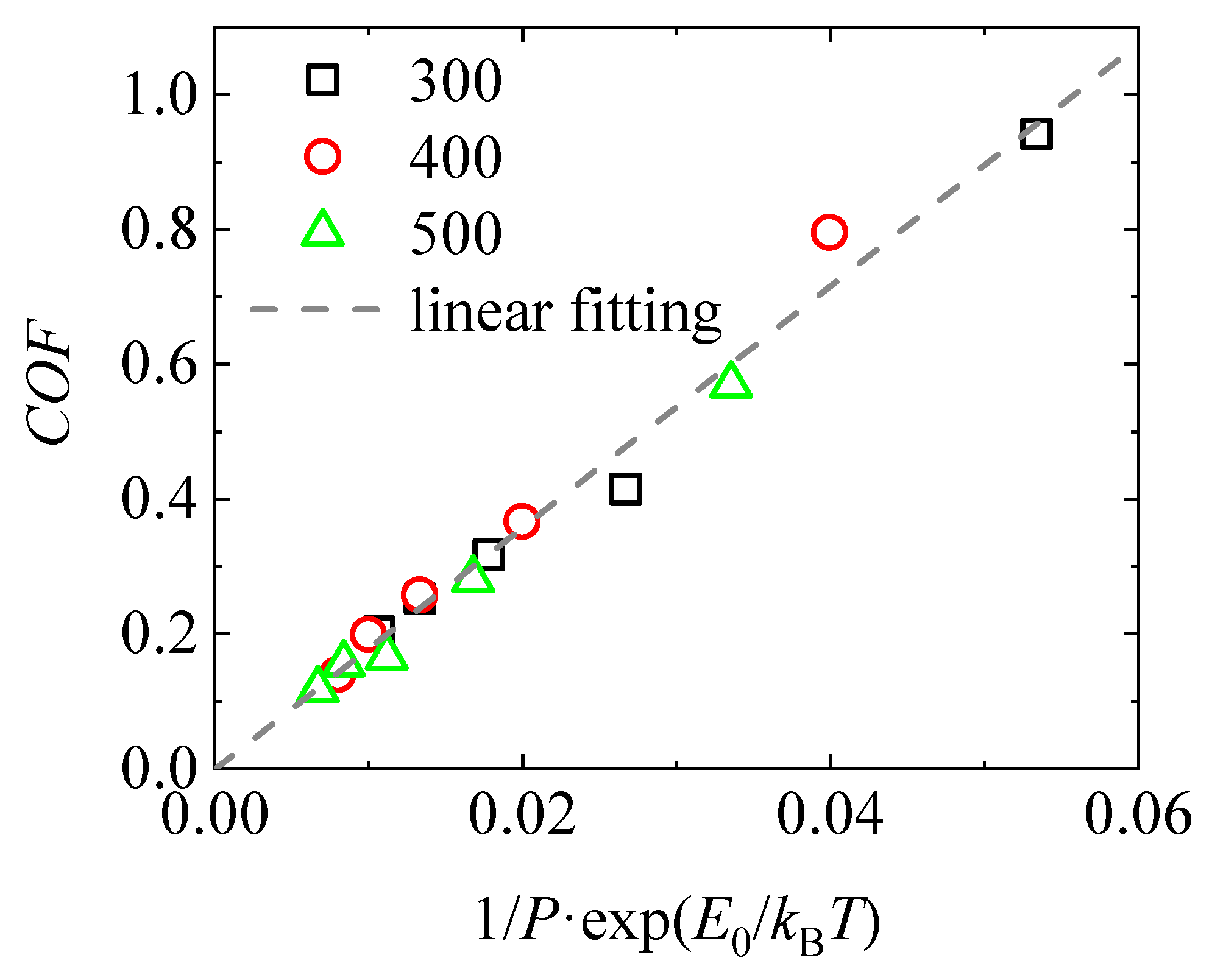

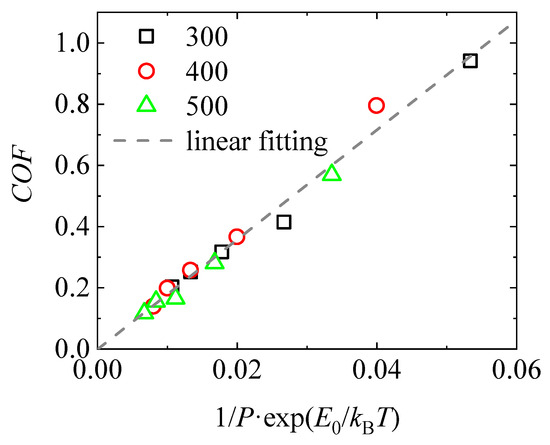

In this work, based on thermally activated friction theory, a composite variable is introduced to express COF as a unified function of P and T. The construction of this variable is inspired by the Kramers reaction-rate theory [37], where friction is dominated by thermally activated transitions of atoms over a potential energy surface, with the transition rate given by: [38], where P is the normal pressure, T is the temperature, kB is the Boltzmann constant, α is the pressure coupling coefficient and E0 is the activation energy. This formulation reveals that load modulates the shape of the potential energy landscape (thus affecting activation energy), while temperature alters the transition probability, both of which contribute to frictional behavior. As such, coupling load and temperature into a composite variable allows effective characterization of their interdependent regulation in nanoscale friction.

Figure 8 presents the quantitative relationship between COF and the composite variable . Data points at different temperatures (300 K, 400 K, and 500 K) are denoted by different symbols. All simulation results align well along a linear trend line (dashed), demonstrating a clear linear correlation between COF and the composite variable. This confirms that friction behavior under varying pressure and temperature conditions can be unified as: , The results validate that the frictional behavior in this system conforms to a thermally activated friction model. By introducing this composite variable, COF data under different pressure–temperature coupling conditions can be normalized, thereby enabling the construction of a predictive friction model with potential applicability in practical engineering design.

Figure 8.

Quantitatively correlation of coefficient of friction with applied loads and temperatures. Values of temperatures are tabulated in the legend.

Moreover, the similar slope of the fitted lines indicates a nearly constant activation energy across various conditions, reflecting a stable interfacial structure and consistent friction mechanism. This linear relationship also implies that frictional performance can be effectively tuned by adjusting either temperature or normal pressure, providing a theoretical basis for the design of controllable interfacial lubrication systems.

The Arrhenius-like linear correlations illustrated in Figure 7 and Figure 8 align with experimental investigations into thermally activated friction. Atomic Force Microscopy measurements conducted on graphite substrates have documented a systematic reduction in frictional forces with elevated temperatures, a phenomenon that is well-reproduced by thermally activated Prandtl–Tomlinson models [34,36]. In boundary-lubricated configurations, the nanoscale frictional behavior of tribofilms generated by engine oils has been theoretically rationalized within an Eyring-type theoretical framework, wherein the activation energy barrier is jointly regulated by the combined effects of normal pressure and temperature [39]. Briefly, the proposed thermally activated framework and the quantitative relationships established here are explicitly restricted to the C60-lubricated interface under the current geometric configuration and ranges of load and temperature. Furthermore, a condition-consistent MD comparison between C60 lubrication systems, bare solid–solid contact interfaces, and alternative nanocarbon lubricants (e.g., graphene or carbon nanotubes) is an important avenue for subsequent investigations, which will strengthen the generalizability of our current findings on nanocarbon lubrication.

It should be emphasized that the present analysis is restricted to the range of normal loads and operating temperatures explored in our simulations, for which the contact remains essentially in a sliding-dominated regime. Ruan et al. [13] noted the regime transition under mixed rolling-sliding conditions that coincided with a marked friction coefficient decrease, yet this research finding lies outside the current predictive boundaries of our modeling framework. The applicability of our theory is confined to sliding contacts devoid of a pronounced rolling component.

Though this study did not conduct direct one-to-one validation of MD results against experimental measurements under identical operating conditions, the key discoveries are highly congruent with well-established frameworks in the nanocarbon lubrication domain, offering strong indirect corroboration for the credibility of simulation-based conclusions [12,40,41,42]. Future work will integrate liquid base oils and dispersants, and systematically compare C60 with other nanocarbon lubricants to bridge the simulation-practice gap.

4. Conclusions

In this study, MD simulations were conducted to systematically investigate the frictional behavior of C60 nanostructured additives between Fe-C alloy substrates under varying temperature and normal load conditions. A predictive friction model was established by quantifying the relationship between the COF and the composite variable integrating temperature and load, and this model holds potential applicability for practical engineering design scenarios. The main conclusions are as follows:

Frictional behavior is primarily dominated by temperature rather than normal load. Owing to the high rigidity of fullerene molecules, variations in load exert a marginal effect on the real interfacial contact area. Conversely, elevated temperatures intensify atomic thermal vibrations, lower potential energy barriers, and facilitate interfacial slip. As a result, the COF decreases significantly, manifesting characteristics of thermally activated friction reduction.

The COF is significantly influenced by the coupled effect of normal load and temperature. With increasing load, interfacial activity intensifies, which induces a more uniform shear stress distribution and a progressive reduction and stabilization of COF, and in parallel, elevated temperature boosts thermal activation, reduces energy barriers, and facilitates interfacial slip and energy redistribution. Overall, the frictional behavior is mainly controlled by temperature-driven thermal activation, resulting in a continuous friction-reducing trend with increasing load and temperature.

The thermally activated friction mechanism is corroborated. Specifically, a linear relationship between and yields an average activation energy of ~0.03 eV, confirming the validity of the thermally activated model in this system.

A unified predictive model for friction is established. Based on the composite variable a quantitative model was developed that accurately fits COF under various load and temperature conditions, exhibiting robust predictive performance and physical consistency. Normalized data from different simulations collapse onto a single linear trend, unveiling the intrinsic coupling relationship between pressure, temperature, and frictional behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and W.L.; Methodology, Y.R. and X.G.; Formal analysis, H.H. and Z.C.; Investigation, Y.R.; Writing—original draft, Y.R.; Writing—review and editing, X.G. and C.S.; Visualization, C.S., H.H. and S.L.; Resources, Z.C.; Supervision X.G. and W.L.; Funding acquisition, W.L.; Project administration W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors grateful for acknowledge financial support from the Service Research Project for the Key Research and Development Program in Shandong Province (No. SYS202203), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2020 ME017).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, J.; Huang, Y.; He, Y.; Shi, Y. Nanolubricant Additives: A Review. Friction 2021, 9, 891–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Li, J.; Duan, H. Nanomaterials for Lubricating Oil Application: A Review. Friction 2023, 11, 647–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Srikanth, N.; Kong, L.B.; Zhou, K. Carbon Nanomaterials in Tribology. Carbon 2017, 119, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnazar, S.; Bagheri, S.; Abd Hamid, S.B. Enhancing Lubricant Properties by Nanoparticle Additives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 3153–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J. Superlubricity of Carbon Nanostructures. Carbon 2020, 158, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Yu, L.; Tong, Y.; Yan, M.; Yang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Shangguan, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Research Progresses of Nanomaterials as Lubricant Additives. Friction 2024, 12, 1347–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha Ray, S.; Okamoto, M. Polymer/Layered Silicate Nanocomposites: A Review from Preparation to Processing. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003, 28, 1539–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, Q.; Martini, A. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Atomic Friction: A Review and Guide. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2013, 31, 30801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, L.K.; Ji, Q.; Mori, T.; Miyazawa, K.; Yamauchi, Y.; Hill, J.P.; Ariga, K. Fullerene Nanoarchitectonics: From Zero to Higher Dimensions. Chem. Asian J. 2013, 8, 1662–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, B.C.; Han, Y.C.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.K.; Park, S.H.; Hwang, Y.J. Tribological Effects of Fullerene (C60) Nanoparticles Added in Mineral Lubricants According to Its Viscosity. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2010, 11, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, S.; Hwang, Y.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, C.; Choi, Y.; Ku, B.C.; Lee, H.; Lee, B.; Kim, D.; et al. Application of Fullerene-Added Nano-Oil for Lubrication Enhancement in Friction Surfaces. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Su, L.; Deng, G. Influence of Nanoparticles in Lubricant on Sliding Contact of Atomic Rough Surfaces—A Molecular Dynamics Study. Lubricants 2024, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Wang, X.; Bao, L.; Zhou, F. Mechanism of Non-Amontons Boundary Friction of Fullerene Ball Nano-Additives. Tribol. Lett. 2025, 73, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Jiang, J.; Liu, G.; Li, C. Tribological Mechanism of Carbon Group Nanofluids on Grinding Interface under Minimum Quantity Lubrication Based on Molecular Dynamic Simulation. Front. Mech. Eng. 2023, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewen, J.P.; Spikes, H.A.; Dini, D. Contributions of Molecular Dynamics Simulations to Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication. Tribol. Lett. 2021, 69, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, A.; Nikonov, A.; Österle, W. MD Sliding Simulations of Amorphous Tribofilms Consisting of Either SiO2 or Carbon. Lubricants 2016, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, J.; Bu, Y. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Nanoparticles as Lubricant Additives: A Review. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 259, 114174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, F.H.; Kim, S.H.; Martini, A. Reactive Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Thermal and Shear-Driven Oligomerization. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 591, 153209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.J.; Kim, D.E. Molecular Dynamics Investigation on the Nano-Mechanical Behaviour of C60 Fullerene and Its Crystallized Structure. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 9849–9858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukowski, A. Visualization and Analysis of Atomistic Simulation Data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010, 18, 15012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; Wei, J.; Chen, F. Dynamical Behavior of Lubricant Molecules under Boundary Lubrication Explored via Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 83101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Cian, H.J.; Yu, C.H.; Huang, C.W. Friction Coefficient Calculation and Mechanism Analysis for MoS2 Nanoparticle from Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Procedia Eng. 2014, 79, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhao, H.; Luo, X. Effect of Diamond Nanoparticle on the Friction Property of Sliding Friction Pair with Molecular Dynamics Simulation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 51790–51798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmandfard, A.; Toghraie, D.; Mehmandoust, B.; Hashemian, M.; Karimipour, A. Study the Time Evolution of Nanofluid Flow in a Microchannel with Various Sizes of Fe Nanoparticle Using Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 118, 104874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tang, H.; Wang, C. Advances of Molecular Dynamics Simulation in Tribochemistry and Lubrication Investigations: A Review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 126, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Hu, K.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhang, W.; Chen, G.; Kapyelata, C. Analysis of the Storage Stability Property of Carbon Nanotube/Recycled Polyethylene-Modified Asphalt Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Polymers 2021, 13, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; In ’T Veld, P.J.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D.; et al. LAMMPS—A Flexible Simulation Tool for Particle-Based Materials Modeling at the Atomic, Meso, and Continuum Scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlet, L. Computer “Experiments” on Classical Fluids. I. Thermodynamical Properties of Lennard-Jones Molecules. Phys. Rev. 1967, 159, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; Gong, X.; Liao, S.; Duan, C.; Li, L. Effects of Thermostats/Barostats on Physical Properties of Liquids by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 365, 120116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, L.S.I.; Kim, S.G.; Houze, J.; Kim, S.; Tschopp, M.A.; Baskes, M.I.; Horstemeyer, M.F. Structural, Elastic, and Thermal Properties of Cementite (Fe3C) Calculated Using a Modified Embedded Atom Method. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 94102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.D.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Terai, T.; Shibutani, Y.; Sugiyama, M.; Sato, K. Segregation of Carbon in α-Fe Symmetrical Tilt Grain Boundaries Studied by First-Principles Based Interatomic Potential. Mater. Trans. 2021, 62, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, G.I. Carbon Nanotuballs: Can They Drive the Future of Nanofibers? Carbon Trends 2024, 16, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jin, J.; Yang, P.; Zong, Y.; Peng, Q. Graphene Adhesion Mechanics on Iron Substrates: Insight from Molecular Dynamic Simulations. Crystals 2019, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, L.; Hölscher, H.; Fuchs, H.; Schirmeisen, A. Temperature Dependence of Atomic-Scale Stick-Slip Friction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 256101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamtögl, A.; Chadwick, H.; Lechner, B.A.J.; Sacchi, M. Editorial: Dynamics at Surfaces: Understanding Energy Dissipation and Physicochemical Processes at the Atomic and Molecular Level. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1411748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Hamilton, M.; Sawyer, W.G.; Perry, S.S. Thermally Activated Friction. Tribol. Lett. 2007, 27, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramers, H.A. Brownian Motion in a Field of Force and the Diffusion Model of Chemical Reactions. Physica 1940, 7, 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, S.Y.; Jinesh, K.B.; Valk, H.; Dienwiebel, M.; Frenken, J.W.M. Thermally Induced Suppression of Friction at the Atomic Scale. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 71, 65101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, J.; Morris, N.; Rahmani, R.; Balakrishnan, S.; Rahnejat, H. Nanoscale Frictional Characterisation of Base and Fully Formulated Lubricants Based on Activation Energy Components. Tribol. Int. 2020, 144, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, W.H.; Gao, H.; Müser, M.H.; Baykara, M.Z. Persistence of Structural Lubricity on Contaminated Graphite: Rejuvenation, Aging, and Friction Switches. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 12118–12124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewing, J.J. The Influence of Temperature on Boundary Lubrication. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1942, 181, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cusano, C.; Conry, T.F. Thermal Analysis of Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication of Line Contacts Using the Ree-Eyring Fluid Model. J. Tribol. 1991, 113, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).