Effect of Electron Beam Irradiation on Friction and Wear Properties of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PEEK at Different Injection Temperatures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials and Specimen Preparation

2.2. Testing and Characterization

3. Analysis of Experimental Results

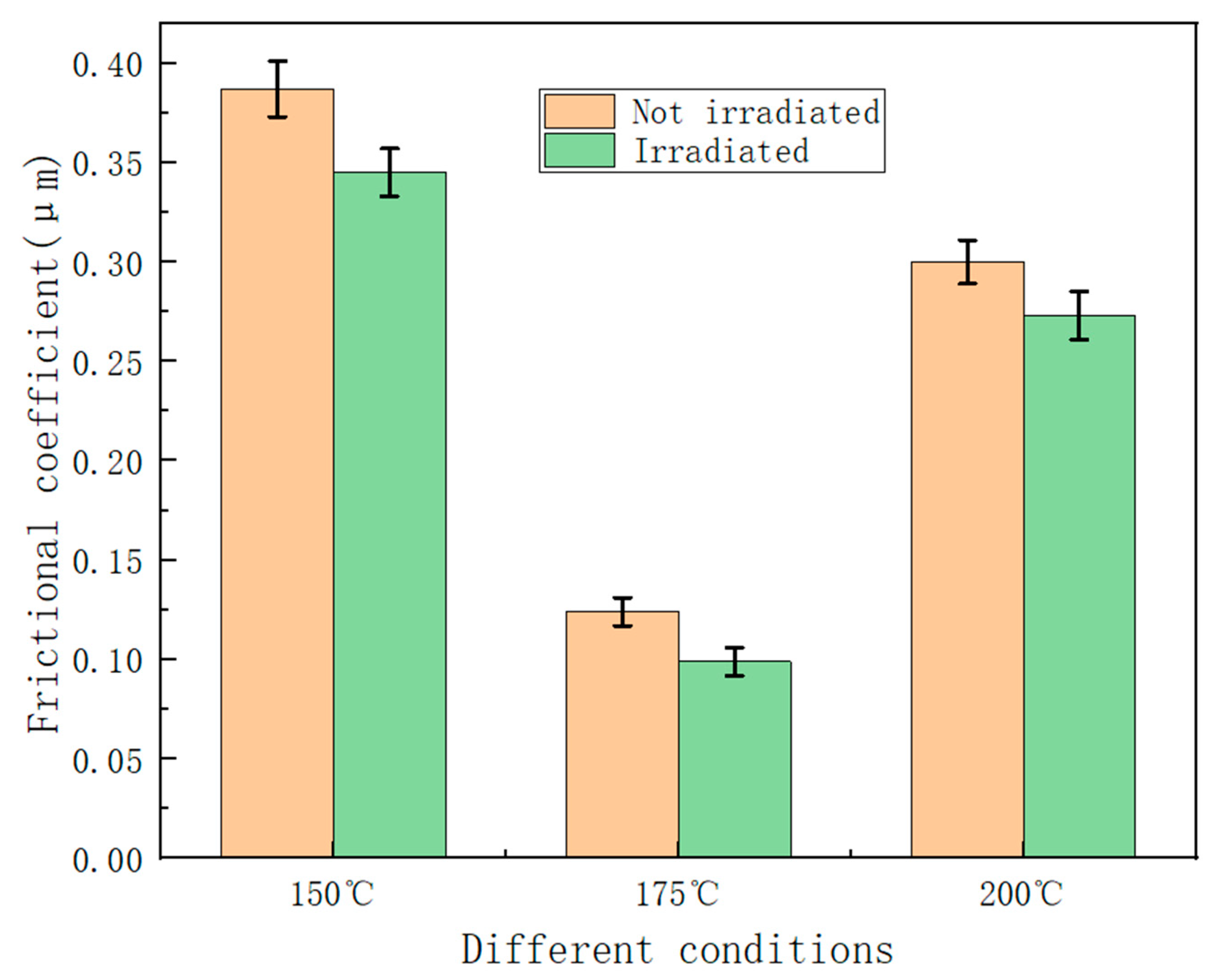

3.1. Analysis of the Friction Coefficient of PEEK Composites

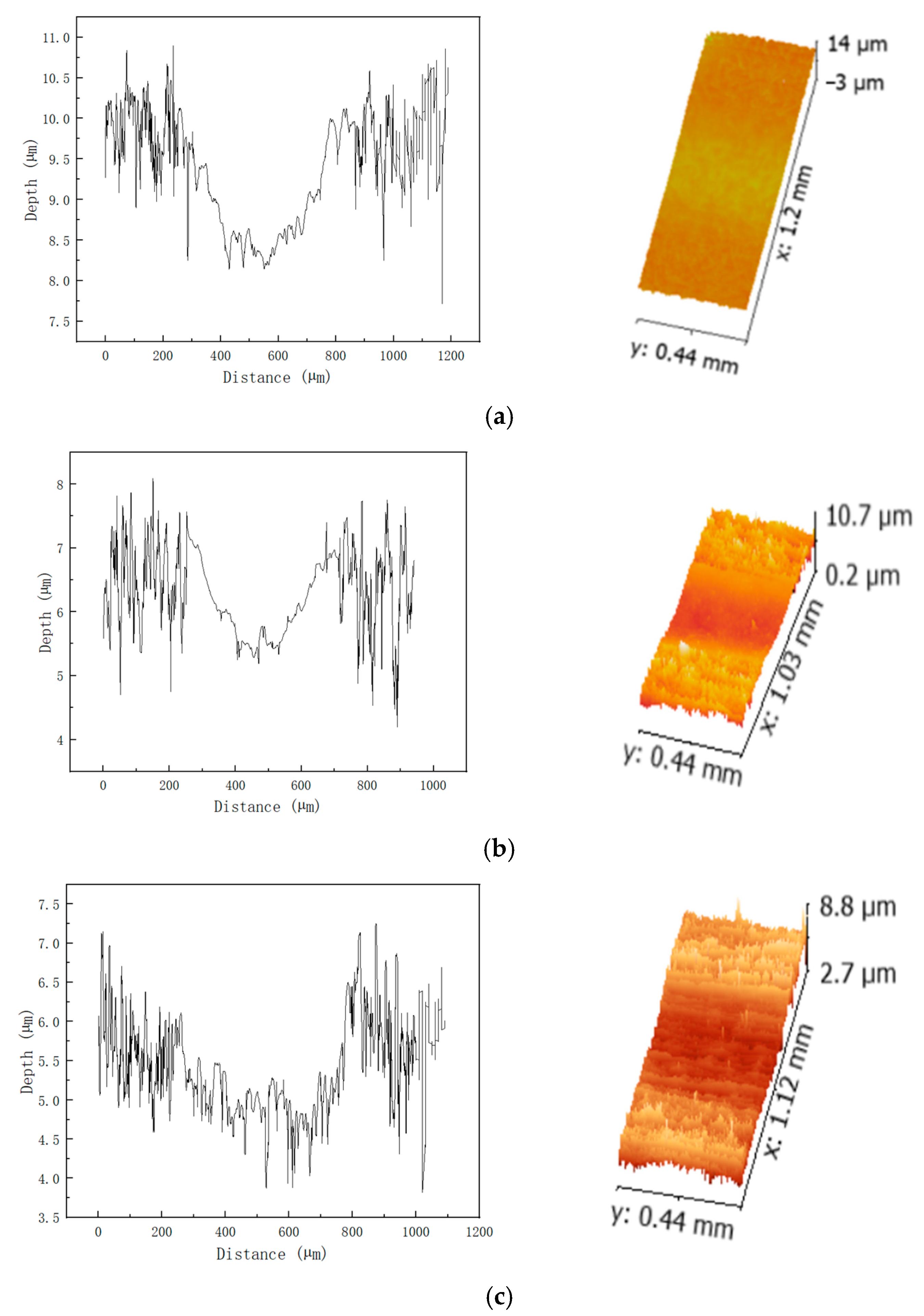

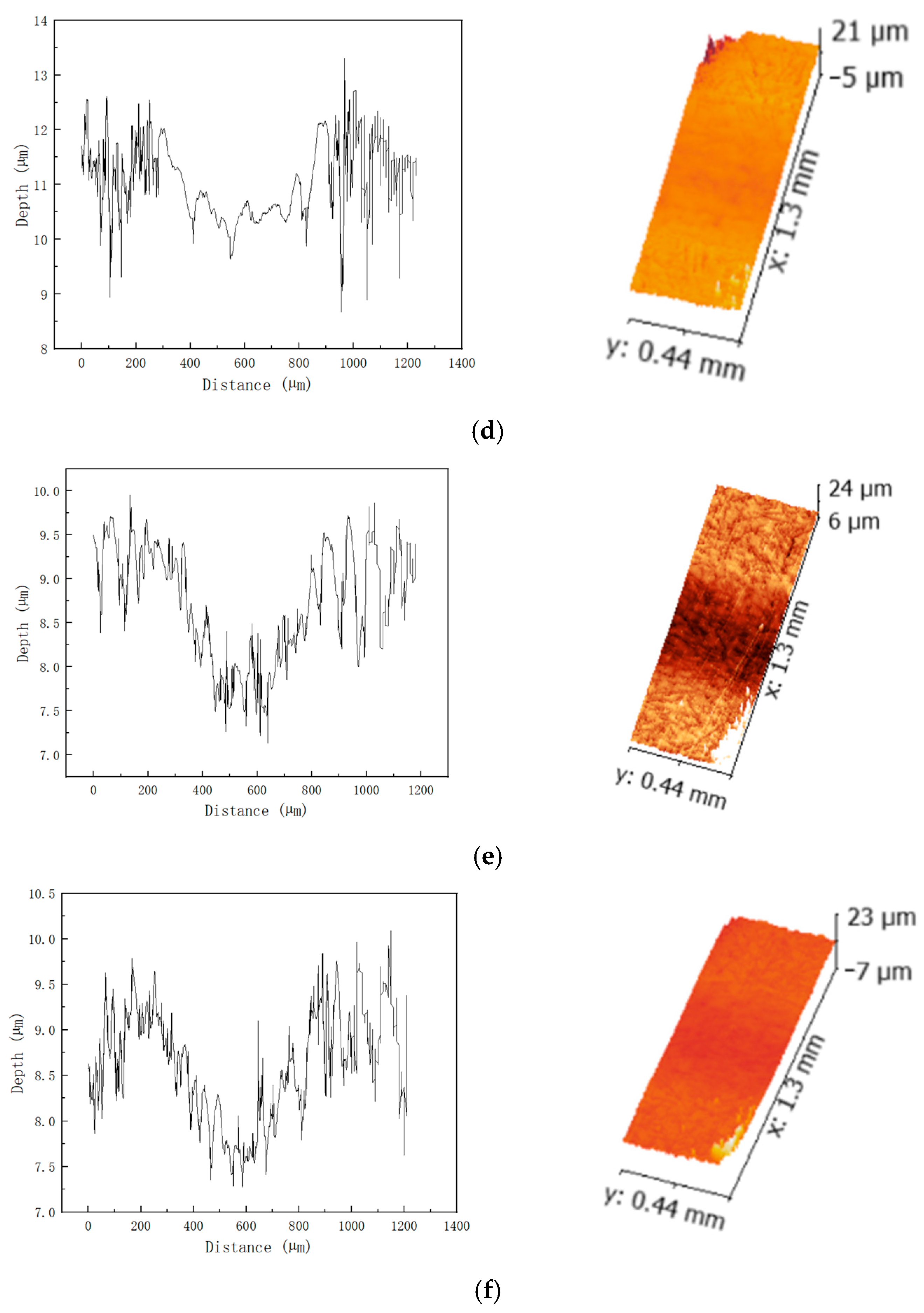

3.2. Analysis of the Wear Resistance of PEEK Composites

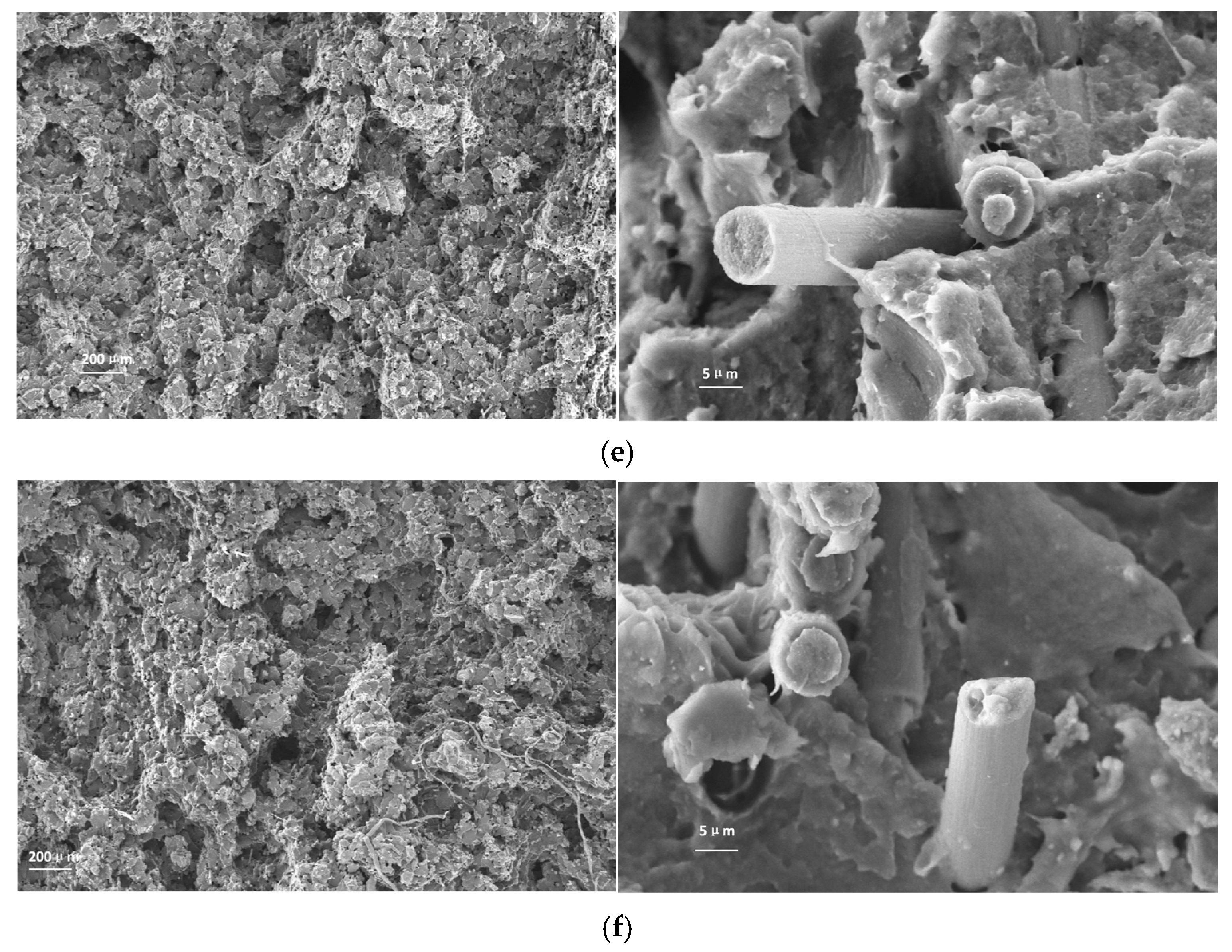

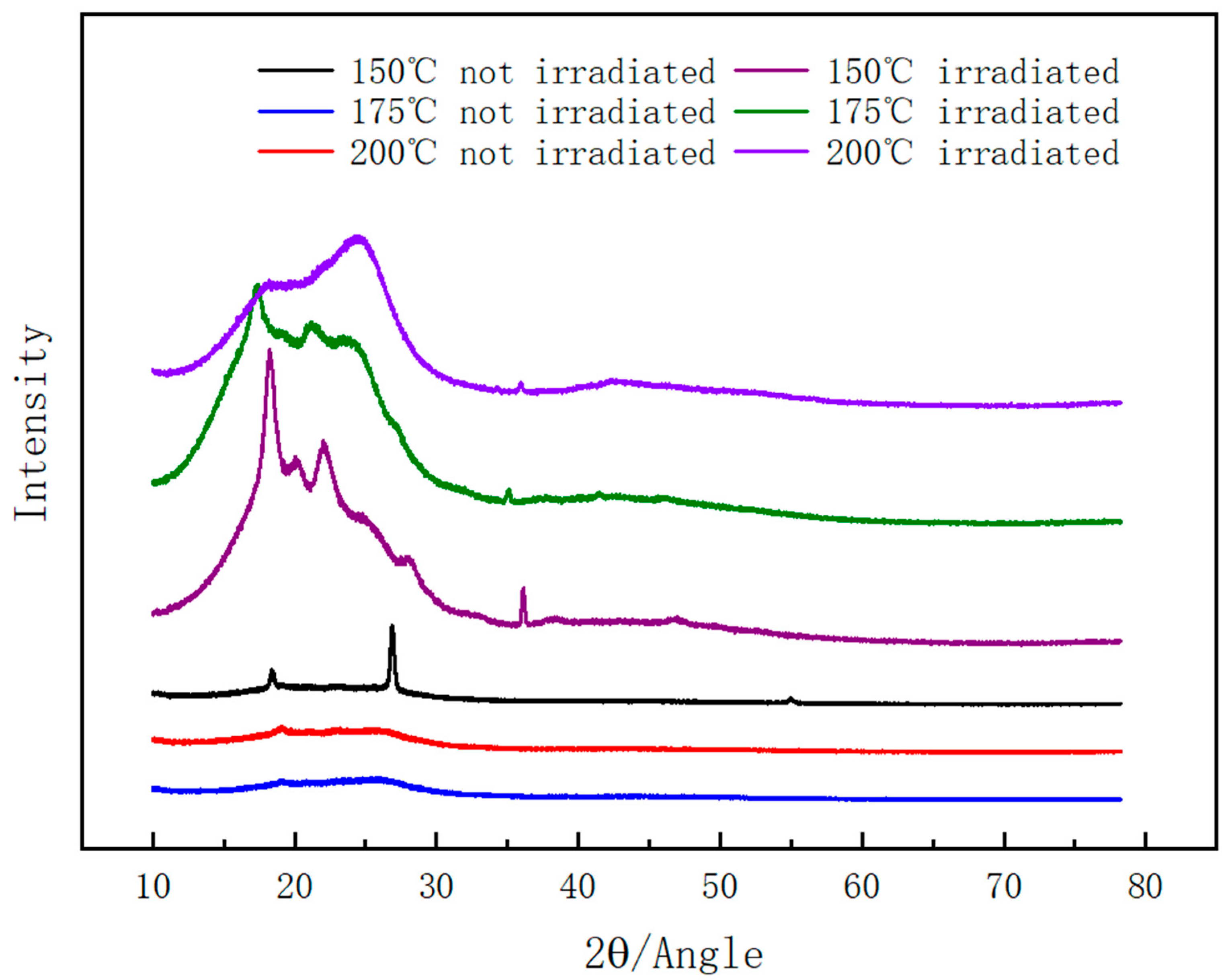

3.3. SEM Analysis of Composite Worn Surfaces

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedrich, K. Polymer composites for tribological applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2018, 1, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Schlarb, A.K. Morphologies of the wear debris of polyetheretherketone produced under dry sliding conditions: Correlation with wear mechanisms. Wear 2009, 266, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panin, S.V.; Nguyen, D.A.; Buslovich, D.G.; Alexenko, V.O.; Pervikov, A.V.; Kornienko, L.A.; Berto, F. Effect of Various Type of Nanoparticles on Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Wear-Resistant PEEK + PTFE-Based Composites. Materials 2021, 14, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.M. PEEK Biomaterials Handbook, 2nd ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Guo, Y.; Yu, Z.; Chen, K.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D. Tribological properties of PEEK composites reinforced by MoS2 modified carbon fiber and nano SiO2. Tribol. Int. 2023, 181, 108315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.F.; Alhashmi, H.; Varadarajan, K.M.; Koo, J.H.; Hart, A.J.; Kumar, S. Multifunctional performance of carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets reinforced PEEK composites enabled via FFF additive manufacturing. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 184, 107625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Schlarb, A.K. The roles of rigid particles on the friction and wear behavior of short carbon fiber reinforced PBT hybrid materials in the absence of solid lubricants. Tribol. Int. 2018, 119, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Jiang, B.; Yang, B.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, H. Synergistically improving the thermal conductivity and mechanical strength of PEEK/MWCNT nanocomposites by functionalizing the matrix with fluorene groups. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2202508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xie, J.; Ji, K.; Wang, X.; Jiao, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, P. Microcellular injection molding of polyether-ether-ketone. Polymer 2022, 251, 124866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xie, J.; Yang, J.; Fu, J.; Zhao, P. Rapid mold temperature rising method for PEEK microcellular injection molding based on induction heating. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 3285–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Shen, W.; Yi, J.; Hou, Y.; Li, F. Significant tribological enhancement and mechanical property maintenance in polyether ether ketone (PEEK) matrix composites with minimal ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) incorporation. Tribol. Trans. 2024, 67, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajuste, E.; Reinholds, I.; Vaivars, G.; Antuzevičs, A.; Avotiņa, L.; Sprūģis, E.; Mikko, R.; Heikki, K.; Meri, R.M.; Kaparkalējs, R. Evaluation of radiation stability of electron beam irradiated Nafion® and sulfonated poly (ether ether ketone) membranes. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 200, 109970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Ji, C.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, B. Process parameter–mechanical property relationships and influence mechanism of advanced CFF/PEEK thermoplastic composites. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 5119–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Shen, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Pei, X. Effects of FDM parameters and annealing on the mechanical and tribological properties of PEEK. Compos. Struct. 2023, 313, 116901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Xu, N.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, X.; Lv, H.; Lu, X.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, D. The optimization of process parameters and characterization of high-performance CF/PEEK composites prepared by flexible CF/PEEK plain weave fabrics. Polymers 2018, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.S.; Jin, F.L.; Rhee, K.Y.; Hui, D.; Park, S.J. Recent advances in carbon-fiber-reinforced thermoplastic composites: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 142, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbanova, B.; Aimaganbetov, K.; Ospanov, K.; Abdrakhmanov, K.; Zhakiyev, N.; Rakhadilov, B.; Sagdoldina, Z.; Almas, N. Effects of electron beam irradiation on mechanical and tribological properties of PEEK. Polymers 2023, 15, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, S.R. Gamma Radiation Effects in Amorphous and Crystalline Polyaryletherketones. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2025, 1, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Zhang, B.; Qiao, L.; Wang, P.; Weng, L. Influence of gamma irradiation-induced surface oxidation on tribological property of polyetheretherketone (PEEK). Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 6513–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiv, J.K.; Kumar, K.; Jayapalan, S. Recent advances in tribological properties of silicon based nanofillers incorporated polymer nanocomposites. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 92, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rival, G.; Paulmier, T.; Dantras, E. Influence of electronic irradiations on the chemical and structural properties of PEEK for space applications. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 168, 108943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorayani Bafqi, M.S.; Birgun, N.; Saner Okan, B. Design and manufacturing of high-performance and high-temperature thermoplastic composite for aerospace applications. In Handbook of Nanofillers; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 2931–2978. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, L.; Ning, K.; Qiao, L.; Wang, P.; Weng, L. Comparative study on microstructure, mechanical, and tribological property of gamma-irradiated polytetrafluoroethylene, polyetheretherketone, and polyimide polymers. Surf. Interface Anal. 2022, 54, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, S.; Jawahar, P.; Chakraborti, P. Influence of carbonaceous reinforcements on mechanical and tribological properties of PEEK composites–a review. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2022, 61, 1367–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 527-2:2012; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 2: Test Conditions for Moulding and Extrusion Plastics. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Puhan, D.; Wong, J.S. Properties of Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) transferred materials in a PEEK-steel contact. Tribol. Int. 2019, 135, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zheng, F.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Liang, Y. Effect of proton irradiation on the friction and wear properties of polyimide. Wear 2014, 316, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Friedrich, K. Enhancement effect of nanoparticles on the sliding wear of short fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A critical discussion of wear mechanisms. Tribol. Int. 2010, 43, 2355–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.N.; Kou, S.Q.; Yang, H.Y.; Xu, Z.B.; Shu, S.L.; Qiu, F.; Jiang, Q.C.; Zhang, L.C. High-content continuous carbon fibers reinforced PEEK matrix composite with ultra-high mechanical and wear performance at elevated temperature. Compos. Struct. 2022, 295, 115837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, K.; Ma, S.; Liu, G.; Yao, J.; Liu, H. Friction and wear behaviour of friction-induced crystallinity of polyaryl ether ketone (PAEK). Wear 2025, 576–577, 206134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Yao, Z.; Sun, Y.; Shen, H. Loading capacity of PEEK blends in terms of wear rate and temperature. Wear 2022, 496, 204306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almas, N.; Kurbanova, B.; Zhakiyev, N.; Rakhadilov, B.; Sagdoldina, Z.; Andybayeva, G.; Serik, N.; Alsar, Z.; Utegulov, Z.; Insepov, Z. Mechano-chemical properties of electron beam irradiated polyetheretherketone. Polymers 2022, 14, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Xu, Q.; Cheng, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, S.; Peng, C.; Joy, A.; Wang, S.Q. Effects of Molecular Weight Reduction on Brittle–Ductile Transition and Elastic Yielding Due to Noninvasive γ Irradiation on Polymer Glasses. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 2447–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumeng, M.; Ferry, F.; Delbé, K.; Mérian, T.; Chabert, F.; Berthet, F.; Marsan, O.; Nassiet, V.; Denape, J. Evolution of crystallinity of PEEK and glass-fibre reinforced PEEK under tribological conditions using Raman spectroscopy. Wear 2019, 426, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyev, B.; Amrin, A.; Mergenbay, A.; Rao, H.J.; Khabdulayeva, A.; Spitas, C.; Golman, B. Thermal, hardness, and tribological assessment of PEEK/CoCr composites. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lümkemann, N.; Eichberger, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Different PEEK qualities irradiated with light of different wavelengths: Impact on Martens hardness. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Nie, S.; Zhang, A. Tribological behavior of PEEK filled with CF/PTFE/graphite sliding against stainless steel surface under water lubrication. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2013, 227, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Lo, K.H.; Wang, S.S. Effect of transfer films on friction of PTFE/PEEK composite. J. Tribol. 2021, 143, 041401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.K.; Lin, G.B.; Shukur, Z.M.; Kukureka, S.N.; Dearn, K.D. Wear and Friction Behaviour of Additive Manufactured PEEK under Non-conformal Contact. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2692, 012046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarges, J.C.; Sälzer, P.; Heim, H.P. Correlation of fiber orientation and fiber-matrix-interaction of injection-molded polypropylene cellulose fiber composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 139, 106112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Muránsky, O.; Zhu, H.; Wei, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ionescu, M.; Yang, C.; Davis, J.; Hu, G.; Munroe, P.; et al. Impact of pre-existing crystal lattice defects on the accumulation of irradiation-induced damage in a C/C composite. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 564, 153684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Yang, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, P.; Zhao, P.; Yang, M.; Li, Y. Tribological behaviors of oxygen-doped carbon coatings deposited by ion-irradiation-assisted growth. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 425, 127689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhadilov, B.; Ormanbekov, K.; Zhassulan, A.; Andybayeva, G.; Shynarbek, A.; Mukhametov, Y.M.Y. Influence of irradiation doses on the mechanical and tribological properties of polyetheretherketone exposed to electron beam treatment. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieille, B.; Coppalle, A. Influence of temperature degradation on the low velocity impact behavior of hybrid thermoplastic PEEK laminates. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2024, 37, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Bian, D.; Zhao, Y. Effect of Electron Beam Irradiation on Friction and Wear Properties of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PEEK at Different Injection Temperatures. Lubricants 2025, 13, 546. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120546

Chen Y, Li J, Bian D, Zhao Y. Effect of Electron Beam Irradiation on Friction and Wear Properties of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PEEK at Different Injection Temperatures. Lubricants. 2025; 13(12):546. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120546

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yi, Jiahong Li, Da Bian, and Yongwu Zhao. 2025. "Effect of Electron Beam Irradiation on Friction and Wear Properties of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PEEK at Different Injection Temperatures" Lubricants 13, no. 12: 546. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120546

APA StyleChen, Y., Li, J., Bian, D., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Effect of Electron Beam Irradiation on Friction and Wear Properties of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PEEK at Different Injection Temperatures. Lubricants, 13(12), 546. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120546