Abstract

Continuous advancements in application technology aimed at higher efficiency and power density place ever-increasing demands on mechanical components and construction elements—and, consequently, on the lubricating greases employed. This is particularly true for rolling bearings, where greases are exposed to high mechanical loads and wide temperature ranges. A current example can be found in the bearings of hybrid vehicle powertrains, which are subjected to extreme thermal and mechanical stress due to engine downsizing, high rotational speeds, and radiant heat from the combustion engine. A collaborative project between the Competence Center for Tribology (KTM) at Mannheim University of Applied Sciences and the OWI Science for Fuels gGmbH (OWI), affiliated with RWTH Aachen University, demonstrated that the loss of lubricating performance—which ultimately leads to bearing failure—is directly linked to changes in the thickener structure. Various degradation processes reduce yield stress and viscosity, thereby eliminating the typical grease characteristics. Mechanical, thermal, oxidative, and catalytic processes all play decisive roles. This paper presents analytical methods that enable these individual influencing factors to be investigated and evaluated independently. These approaches can significantly reduce the need for time-consuming and costly laboratory tests in grease development and qualification.

1. Introduction

Continuous progress in application technology, driven by demands for higher efficiency and power density, imposes increasingly stringent requirements on lubricating greases. This is particularly evident in rolling bearings, where greases must operate under high rotational speeds and wide temperature ranges. Examples include bearings used in hybrid vehicle powertrains, which are subjected to severe thermal and mechanical stress due to engine downsizing, high speeds, and radiant heat from the combustion engine.

For components that are generally lubricated for life in the field of e-mobility, grease service life is a critical factor. However, grease service life is not a clearly definable parameter but rather the result of numerous influencing factors, many of which are not yet fully understood. With the growing focus on different electric drive concepts, issues of compatibility and catalytic effects (particularly in the presence of copper-containing materials) have become central topics in grease development and testing.

Failure of rolling bearings can result in catastrophic damage to the overall system or extended downtime. Bearing failures can have multiple causes: in addition to overloading, material fatigue, assembly errors, and contamination, approximately 50% of all failures are estimated to be attributed to inadequate lubrication [1]. In many cases, the root cause is an inappropriate selection of grease for the specific application [2,3]. Since about 90% of all rolling bearings are grease-lubricated, the topic carries substantial economic relevance.

The service life calculation of grease-lubricated rolling bearings is based on ISO 281 and the fatigue strength of bearing materials [4]. Under critical operating conditions—such as elevated temperatures or high centrifugal forces—bearings may fail due to lubrication breakdown before reaching their theoretical fatigue limit. As mentioned, grease service life is not a standardized property that can be determined by a single test. For this reason, various laboratory aging procedures and endurance tests on bearing test rigs are employed to estimate component life expectancy. These tests are both time-consuming and costly, creating strong industrial demand for innovative and meaningful screening tools [5].

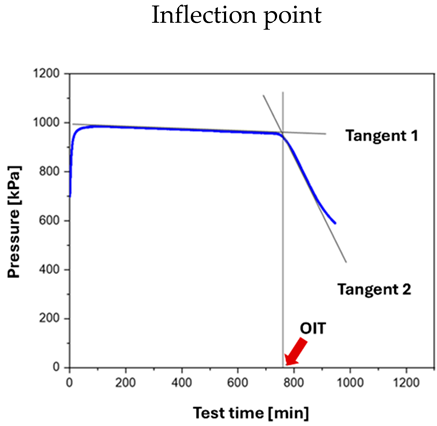

In technical applications, lubricants may suffer irreversible damage due to a wide range of causes (Figure 1). Thermo-oxidative degradation is highly dependent on the surrounding conditions. In non-encapsulated systems, oxidation of the lubricant results in the formation of acids, polymerization products, condensates, and deposits. This process is governed by factors such as temperature, the presence of catalysts (e.g., metal surfaces or wear particles), oxygen availability, and the accumulation of degradation products. In addition, grease aging—and thus degradation and polymerization—along with insufficient lubrication, particularly at elevated temperatures and high rotational speeds, or even electrical current passage, can lead to coking effects [3,6].

Figure 1.

Processes that affect the lubricating grease in practice.

Beyond thermo-oxidative aging, lubricating greases in service are also subjected to severe mechanical and dynamic stresses. In the present study, the individual influencing factors were assessed as independently as possible by means of a carefully designed test selection and matrix [7].

The characterization of lubricating greases with respect to their load-carrying capacity and changes in chemo-physical properties prior to actual technical application is a key element of grease development. For instance, determination of the upper operating temperature limit is an essential part of the FE9 test in accordance with DIN 51821-1 [8]. However, as the FE9 test is both time-consuming and cost-intensive, lubricant developers rely on simpler and faster screening methods in the preliminary stages. It is therefore crucial to understand the relevance, reliability, and limitations of the individual laboratory methods and to employ them strategically within a coherent testing framework.

2. State of Research

In the preceding project DGMK 788 “Screening Test Method for Lubricating Greases” [9], it was demonstrated that the loss of lubricating performance in greases is strongly influenced by thickener degradation. This hypothesis has also been confirmed by other researchers (e.g., [5,10,11,12]). The effect can be clearly observed in soap-thickened greases well before the onset of base oil aging and is therefore a life-limiting factor.

The mechanical behavior of lubricating greases at lubricated surfaces, as well as the release of base oil into the tribological contact, is still not fully understood, which highlights the significant ongoing research demand [13]. The difficulty in providing a straightforward description lies in the complex rheological behavior of greases compared with rheologically simple fluids like oils. A deeper understanding of the rheological properties of greases is thus essential to explain their actual performance under real operating conditions.

In general, lubricating greases are highly structured suspensions consisting of a thickener dispersed in a base oil [14]. Among the various thickener types, fatty acid soaps of lithium, calcium, sodium, aluminum, and barium are the most commonly used, since they are cost-efficient and exhibit favorable properties for a wide range of applications [15]. The thickener is required to increase grease consistency, prevent lubricant loss under operating conditions, and protect against the ingress of contaminants such as solid particles and water, without impairing the lubricating properties that are primarily provided by the base oil and additives. The soap thickener forms a 3-dimensional network that entraps the oil and imparts the desired rheological and tribological performance.

The performance of lubricating greases therefore depends on the nature of their components and the microstructure formed during processing. Suitable structural and physical properties can be achieved not only through the careful selection of ingredients but also through process optimization [16]. Consequently, it is of great importance to understand how the development of and change in the grease microstructure influence the functional and rheological properties of lubricating greases.

It is well established that the flowability of lubricating greases increases with temperature, which in turn enhances lubricity. However, the risk of oxidative and thermal degradation also rises with increasing temperature and residence time [17].

As early as 1998, Kuhn investigated the structural degradation of lubricating greases and observed that variations in rheological properties correlate with structural breakdown [18]. Kuhn later introduced the term “grease wear” as an indicator of changes induced by tribological stress [11].

Based on rolling bearing tests conducted on the R0F rig, Cann et al. demonstrated that grease degradation within bearings is primarily governed by bearing temperature [19,20]. Yu and Yang further confirmed that the deterioration of grease lubrication in electric motor bearings results from elevated temperatures and the associated grease degradation [21].

Adhvaryu et al. examined changes in grease fiber structure as a function of antioxidants and defined structural degradation as a loss of lubricating properties [22]. Couronne and Vergne found that thermal aging shortens fiber length [23]. Similarly, Gonçalves et al. showed that thermal aging alters the thickener matrix [24]. Shen et al. studied the thickener structure of a lithium–calcium grease and demonstrated that prolonged thermal aging gradually disrupts the network structure, thereby significantly reducing grease stability [25,26].

Pan et al. investigated the structural changes in a lithium soap grease during static storage at 120 °C and 150 °C [27]. Their analyses of grease microstructure and infrared spectra were conducted using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), respectively.

The influence of the type, size, and distribution of soap fibers was analyzed by Delgado et al. [28]. Scanning electron microscopy and rheological analyses performed during the manufacturing process of lithium soap grease revealed that the characteristic network structure and grease-specific rheology only fully develop at the final stages of the production process. In a subsequent study, the researchers also examined the rheological behavior and microstructure of lithium greases as a function of soap concentration and base oil viscosity [29]. In this context, they investigated both the complex viscosity and the loss factor tan(δ) as functions of angular frequency (ω).

An interesting contribution to this research area was published by Zhou et al. [12]. The team investigated the shear degradation of a lithium soap grease under shear loading in a rheometer at room temperature. Their results showed that the grease gradually loses its original consistency during testing and exhibits a two-phase aging behavior. In the first phase, reorientation and rupture of the thickener network dominate, leading to a progressive decline in the rheological properties of the grease. In the second phase, aging is primarily governed by the fracture of smaller fiber fragments, resulting in a slower rate of degradation. Based on these findings, an aging equation was formulated using the entropy-based approach of Rezasoltani and Khonsari [30] to describe the degradation behavior of lithium-thickened greases. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of fresh and aged greases further confirmed that changes in the thickener microstructure provide a consistent explanation for the underlying mechanism of lithium grease degradation.

In summary, numerous researchers have reported on the degradation of the thickener network as a result of mechanical–dynamic loading. However, to the best of our knowledge, no specific publications address the complex interplay between mechanical–dynamic stress and thermo-oxidative as well as catalytic processes as they occur under real operating conditions in a roller bearing.

3. Materials and Methods

The focus of this project was on changes in the thickener structure resulting from mechanical, thermal, oxidative, and catalytic stresses. For the first time, an attempt was made to investigate and evaluate the individual contributions of these influences separately by means of a carefully designed experimental selection and planning strategy (Table 1). Chemical and structural changes were identified using state-of-the-art analytical techniques and microscopy.

Table 1.

Systematic investigation of the individual factors influencing grease degradation. (X/-) means that a test without a catalytic element (i.e., with a glass substrate) was also performed as a comparative test in this test.

To examine and characterize the grease structure and its evolution, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), including cryo-SEM in selected cases, atomic force microscopy (AFM), and rheological measurements were employed. Aging and chemical changes were analyzed using FTIR, refractometry, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC).

The project followed an empirical approach: numerous laboratory tests on grease aging were conducted and evaluated as a function of temperature, surrounding medium, and catalytic elements. The chemical analyses carried out at OWI focused particularly on the so-called RapidOxy test, which is gaining increasing importance in industrial practice, since it also accounts for interactions with catalytic elements that almost invariably occur in real-world applications (ASTM D8206 [31], DIN 51808-2 [32], DIN 51830-2 [33]).

The core of the tribological experiments consisted of rolling bearing tests performed on the multi-station rolling bearing test rig (MPWP), conducted in accordance with the FE9 procedure as specified in DIN 51821-1 [8]. In addition, at KTM, quasi purely mechanical shear loading was applied using small-scale shear tests, alongside oven-aging tests and rheological characterization performed with various methods.

For the analysis of the extensive datasets, methods and representation techniques from Design of Experiments (DOE) were employed. The following table outlines the general approach adopted in this collaborative project (Table 1).

3.1. Model Greases

Model greases were used in the investigations to ensure that all constituents were precisely known, and their effects could be examined systematically from a scientific perspective. As base oils, a mineral oil (mixture ratio naphthenic to paraffinic: 30/70) and a polyalphaolefin (PAO, 100 cSt @ 40 °C) were used. For the thickener system, focus was placed on a lithium soap (lithium 12-hydroxystearate—pre-formed soap) and a diurea thickener.

By combining the respective base oils and thickeners, four base greases were available during the project, which were further additivated with various antioxidants and anti-wear agents. In total, 16 model greases were produced and investigated. In supplementary tests, the influence of catalytically active iron and copper ions was also studied by blending Fe- and Cu-naphthenates into the greases.

3.2. Thermal, Oxidative, and Catalytic Stress

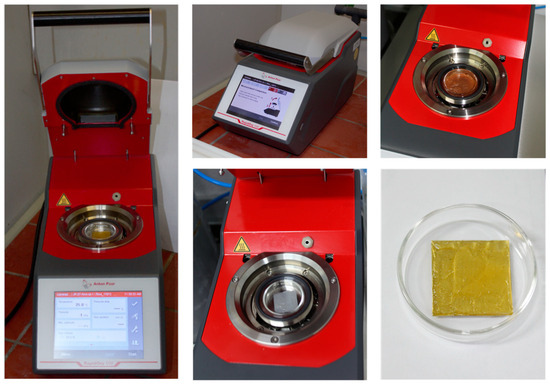

Two procedures were employed to impose thermal–oxidative stress with and without catalytic loading: conventional oven-aging and tests using the RapidOxy device (Anton Paar Germany GmbH, Ostfildern, Germany).

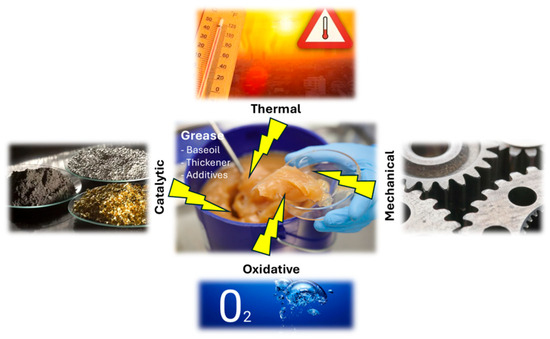

3.2.1. Isothermal Aging on Catalyst Plates

In this thermal/catalytic aging or screening test, lubricating greases (Greases 1–16) were stored isothermally for several days in a temperature-controlled oven on catalyst plates made of steel (S235JR), high-purity copper (99.8%), or inert glass. Prior to grease application, all steel and copper plates were cleaned of oxides and thus “activated” by glass bead blasting (Figure 2). Residual contaminants on all substrates were subsequently removed using boiling-range benzine in an ultrasonic bath. The precise application of the required grease quantity and layer thickness was ensured using a grease gauge. Two application methods were employed:

Figure 2.

Methods used in “oven aging”.

Open system: A grease layer thickness of 1 mm was applied to the substrate. This method, which is also successfully used by Robert Bosch GmbH [5,10], is referred to as the “open system” in the following report.

Covered system: A grease layer thickness of 2 mm was applied and then covered with a second plate to protect the grease from oxidation. This is referred to as the “covered/capped system.”

Subsequent oven aging was carried out at 140 °C for 24 or 72 h. During this period, the oven remained closed to maintain a constant oxidative atmosphere, and no air circulation was applied. Furthermore, greases with different base oils, thickeners, or additive packages were not aged simultaneously, in order to prevent cross-contamination caused by evaporation or transfer effects. After oven aging, the greases were removed and cooled to room temperature.

Samples with a grease layer thickness of 1 mm (open system) were influenced by oxidative effects, which corresponds to real-world applications. In contrast, the covered system (2 mm layer thickness) primarily reflected thermal and catalytic effects in isolation.

The thermally aged greases were subsequently subjected to rheological analysis to determine the extent of structural degradation.

3.2.2. Aging in the RapidOxy Test Device

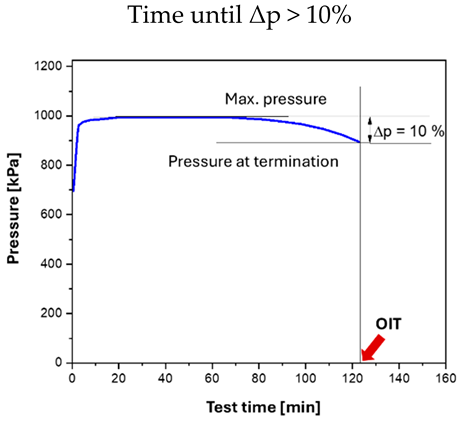

Oven aging represents a pragmatic method and provides larger quantities of aged lubricant for subsequent investigations. However, it is associated with numerous boundary conditions that are difficult to define precisely, making standardization challenging. In recent years, work has therefore been undertaken to develop a DIN standard describing a rapid-aging method for greases, allowing the oxidation behavior under catalytic influence to be measured and compared. The standard DIN 51830 “Testing of lubricants—Determination of the oxidation stability of lubricating greases” [34] has been extended by “Part 2: Accelerated determination of the Arrhenius activation energy of thermo-oxidative degradation” [33]. The test conditions defined in Part 2 are more closely aligned with practical requirements (see Table 2). Furthermore, the inflection point determined in this method (see figures in Table 2), unlike predefined pressure-drop percentages, directly indicates the point at which the antioxidants are depleted, and the grease base structure (mainly the thickener) begins to degrade. Figure 3 shows the device, the sample chamber, and a prepared grease specimen.

Table 2.

Comparison of the two parts of DIN 51830-1 [34] and -2 [33] in terms of sample quantity, termination criteria, and catalysis. The temperature can be adjusted to suit the respective grease.

Figure 3.

RapidOxy with open reaction chamber and grease samples placed in a glass dish (top right) as well as on glass and brass plate (bottom center and right).

The test method monitors the pressure drop within the reaction chamber to quantify oxygen consumption during the formation of oxidation products. For this purpose, the grease is weighed and placed inside the reaction chamber, which is then pressurized with oxygen to an initial pressure of 7 bar. During heating to the holding temperature, the pressure increases further. The subsequent reaction of oxygen with the grease is typically observed as a continuous pressure decrease in the reactor. Additives in the grease suppress the formation of oxidation products, while contact with metallic surfaces exerts a catalytic effect and accelerates oxidation.

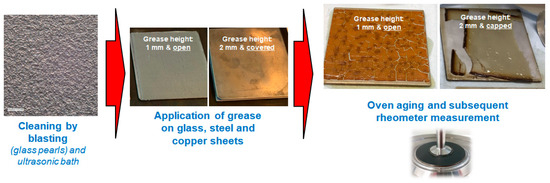

Parts 1 and 2 of DIN 51830 differ in sample amount and application method. In Part 1, 4 g of grease are deposited in a glass dish, whereas in Part 2, 0.5 g of grease is spread onto metallic plates (brass or unalloyed steel S235JR) or inert glass plates. Table 2 compares the test conditions of both standard parts.

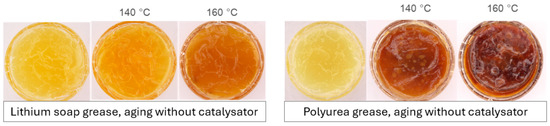

For the tests according to Part 1 of the standard, small glass dishes (Øi = 37.5 mm) are used, which are filled bubble-free with grease and whose surface is subsequently smoothed as evenly as possible. Figure 4 shows the sample holders before and after testing in the RapidOxy.

Figure 4.

Grease samples for DIN 51830-1; left: freshly filled grease, center and right: after aging at different temperatures.

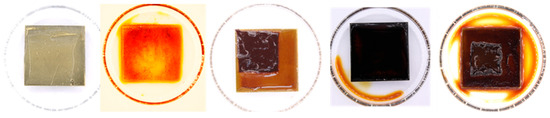

In the tests according to Part 2 of the standard, square plates (26 mm × 26 mm × 1 mm) made of brass (CW508L), steel (1.0330), or glass are used, onto which 0.5 g of grease is applied. The plate is then placed in a glass dish (Øi = 43 mm) that collects any oil released during testing and is exposed in the pressure chamber (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Grease samples for DIN 51830-2, left: steel plate with fresh grease; all other images show different greases after aging at different temperatures on different plates made of glass, brass, and steel.

Within the project, all greases were tested at 140 °C and 160 °C according to Parts 1 and 2 of the standard. For the third temperature required for Arrhenius evaluation (Part 2), 150 °C was selected for the lithium greases. The urea greases exhibited high thermo-oxidative stability and therefore long test durations; to accelerate the measurements, the third test for these greases was conducted at 170 °C.

A test according to Part 1 of the standard is automatically terminated by the device once a pressure drop of 10%—relative to the maximum chamber pressure—is reached. The corresponding duration represents the Oxidation Induction Time (OIT), which is typically reported in minutes.

For testing according to Part 2 of the standard, the experiment must be run sufficiently long to observe the inflection point of the curve. For unknown greases, termination criteria well above 30% are advisable. In this case, the runtime is not used to determine the OIT; instead, the time at the inflection point, determined by the tangent intersection method, is taken as the OIT (Table 2, right picture). This value is then combined with the results obtained at additional temperatures for the calculation of the Arrhenius activation energy.

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Investigations

SEM analysis is typically conducted under high vacuum (<10−7 mbar or <10−5 Pa). When applied to lubricating greases, complete removal of the oil bound in the thickener structure is required, as residual oil would condense in the chamber and on detectors. Depending on the thickener type, various procedures have been reported to extract the oil phase while minimizing structural alteration.

SEM and AFM have been widely used to visualize grease microstructures. The most frequently cited images are those of lithium soap greases (lithium 12-hydroxystearate with mineral oil), showing twisted and entangled fibers [29,35,36,37,38,39]. Delgado demonstrated that such structures form only above 14% thickener concentration and that entanglements increase with concentration [29]. At lower concentrations, platelets rather than fibers were observed. Increasing base oil viscosity resulted in longer fibers, larger voids, and reduced entanglement. Fiber diameters of 0.1–0.5 µm were reported from SEM and AFM images of lithium greases [35,36,37]. Differences between SEM and AFM values were attributed to oil extraction during SEM preparation [37]. Base oil chemistry appeared to have little effect on fiber diameter [35]. Greases thickened with calcium soaps or polyureas exhibited spherical particles or platelets instead [38,39]. As emphasized by Hodapp et al., understanding the rheology of such complex systems remains a major challenge [13]. The influence of base oil chemistry and viscosity on soap structure and grease rheology is still not fully resolved.

Several extraction methods have been described in the literature. Delgado et al. documented grease microstructure during manufacturing by sampling at different process stages [28]. Samples were extracted with hexane, dried at room temperature, and gold-coated prior to SEM. Roman et al. studied six metal soap greases (lithium, calcium, lithium/calcium) and two biopolymer-thickened greases, using mineral and synthetic base oils [40]. Oil extraction was carried out with n-hexane over one week, with solvent replacement 3–4 times. Samples were then dried for several days and gold-coated.

Rawat et al. investigated paraffin greases doped with graphene oxide [41]. Oil was extracted with n-hexane by rinsing for 15 min, followed by drying at 60 °C. Samples were then gold-coated to enhance secondary electron signals to obtain a good contrast. Lin et al. analyzed greases recovered from spherical roller bearings. Preparation involved rinsing with n-hexane, immersion for 15 min, drying in a vacuum desiccator, further drying at 35 °C, plasma cleaning, and iridium coating [42].

Ackermann focused on identifying interfering factors in pasty media [43]. Extraction was performed with n-hexane for lithium greases and acetone for urea greases, followed by drying at 30 °C and carbon coating. Cyriac et al. investigated film thickness in elastohydrodynamic contacts [36]. For SEM preparation, oil was removed using distilled petroleum ether; samples were dried and gold-coated.

Muller et al. employed SEM, cryo-SEM, and TEM for grease characterization [44]. Oil was extracted with petroleum ether 40–60, applied to thin films on holders. After evaporation, samples were coated with gold and tungsten.

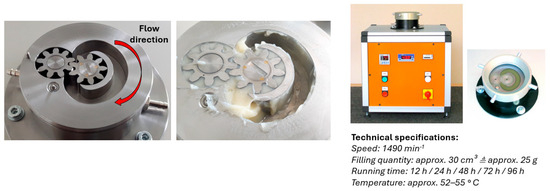

3.4. Mechanical Stress

Purely mechanical loading of the grease structure was applied using the Klein shear apparatus by Albert Engineering (Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany). This device subjects greases to controlled shear under defined conditions. The grease is circulated in a closed loop, operating similarly to a gear pump at constant rotational speed (n = 1490 min−1) (Figure 6). Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine the torque or the force between the tooth flanks with this device. Therefore, it is also not possible to determine the lubricating film height and thus the shear rate.

Figure 6.

Klein shear apparatus.

Frictional heat generated during shearing resulted in grease temperatures of 52–55 °C during the tests. This temperature range is not expected to induce significant aging effects; thus, the test conditions can be regarded as representing purely mechanical stress. All 16 model greases were subjected to shearing in the Klein apparatus for 12 h, 24 h, and 72 h, corresponding to 1.07 million, 2.14 million, and 6.44 million load cycles, respectively.

3.5. Application-Oriented Loading by Rolling Bearing Testing (FE9)

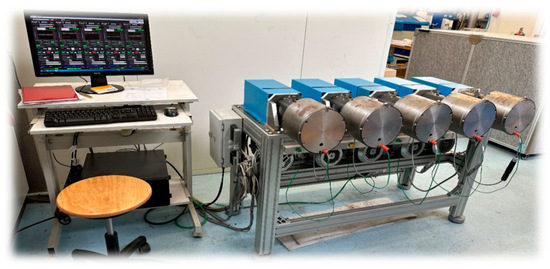

Application-relevant testing of the greases was conducted on the MPWP test rig (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Multi-stage roller bearing test bench (MPWP) of the KTM.

In the so-called FE9 test, the test bearings are loaded by means of axially preloaded disk springs and driven by a frequency-controlled three-phase asynchronous motor. In addition, the test heads can be heated to temperatures of up to 200 °C via heating elements (Figure 8). Each test head is individually monitored for temperature and friction torque development and can be controlled separately.

Figure 8.

Test head in FE9 configuration.

Experiments were performed in accordance with DIN 51821-2 (“FE9 test”) [8]. In this test, rolling bearings (designation 7206-B-XL-JP) filled with the respective grease are subjected to a normal load of 1500 N and operated at a rotational speed of 6000 min−1. The bearings are capped but not sealed, allowing oil and degraded grease to escape from the raceways.

At the start of testing, lithium soap-thickened greases were conditioned at 140 °C. For diurea-thickened greases, no failure could be induced within the maximum acceptable test duration of 1000 h; therefore, the starting temperature for these greases was increased to 160 °C. According to the standard, bearing failure is defined when either the temperature rises above 220 °C or the frictional torque exceeds 1.44 Nm [8].

These component-level tests thus expose greases not only to severe mechanical stresses within the bearing but also to pronounced thermal, catalytic, and oxidative effects.

4. Results

4.1. Rolling Bearing Testing (FE9)

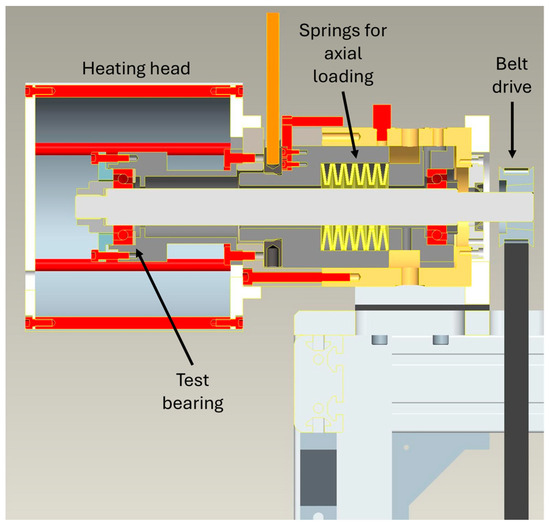

The lifetime obtained in the FE9 test according to DIN 51821-1 [8] represents the primary target parameter in grease development. All other investigations aim to predict the service life in this demanding test by means of simpler chemo-physical laboratory methods.

All 16 model greases were tested in FE9 at least in duplicate. Additional runs were performed if deviations occurred. Tests were carried out in full compliance with DIN 51821-1. Figure 9 summarizes the results of all experiments. Additives used are listed at the top of the diagram. Greases formulated with mineral oil as base oil are shown in blue, PAO-based greases in red. Lithium soap-thickened greases are highlighted in gray, while diurea-thickened greases are shown with a white background.

Figure 9.

Overview of the results of all FE9 tests (mean lifetimes in hours with error bars).

All diurea-thickened greases (white background) exhibited substantially longer running times, despite the 20 °C higher test temperature of 160 °C compared with lithium soap greases. Mineral oil combined with diurea thickener, even without additives, achieved the third-longest average lifetime. Interestingly, the use of AO additives often reduced lifetime. Zinc dialkyldithiophosphate (ZnDTP) was effective only in diurea-based greases, whereas the effect in lithium-thickened greases was relatively minor. The amine additive increased the lifetime of lithium soap greases but tended to reduce it in diurea greases. The phenolic additive slightly extended the life of lithium soap greases but again reduced it in diurea greases compared with unadditivated references.

These findings highlight that additive performance is strongly dependent on the grease formulation and is often case-specific, making generalized conclusions difficult. To better illustrate and analyze the extensive results, various visualization and statistical evaluation methods were applied at the end of the project. The only consistent observation is the significantly higher performance of PAO-based greases compared with mineral oil-based ones. In all other respects, performance was highly dependent on composition and operating conditions.

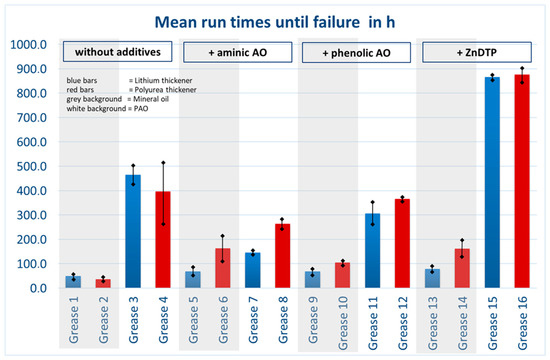

To examine the transferability of results from catalyst-assisted oven aging to FE9 application testing, several greases were blended with copper(II) naphthenate (3049 ppm, determined by XRF). In parallel, the same base greases (without Cu addition) were tested in bearings equipped with electroplated copper cages. The plating thickness was approximately 20 µm, corresponding to ~2.396 g of copper. All tests were conducted under the same standard conditions.

Comparison with grease 3 in the standard bearing (Figure 9; mean lifetime ~470 h) clearly showed that copper as a catalytic element strongly reduced lifetime, in some cases by up to a factor of four (Figure 10). Notably, both approaches—copper ion addition to the grease and electroplated copper cages—yielded nearly identical results.

Figure 10.

Influence of copper on service life.

The positive effects of brass cages observed in DGMK project 788 [9] can therefore be attributed to the lower mechanical stress on the grease associated with the machined solid cage and potentially to improved lubricant supply in the tribological contact, rather than to the copper content itself.

4.2. Chemical Characterization

A major work package of the project involved the investigation of grease samples and their base oils in both the fresh state and various aged states using chemical-analytical methods.

4.2.1. RapidOxy According to DIN 51830—Part 2

Thermo-oxidative testing of thin grease films in contact with catalytically active plates was used to determine the Oxidation Induction Time (OIT). This sample preparation method ensures that the entire grease mass is exposed to oxygen in the test chamber and to the metallic plates. The OIT was determined graphically from the inflection point of the pressure–time curve recorded in the RapidOxy measurement. In round robin tests with fully formulated greases, evaluation proved to be highly repeatable. For the model greases used in this study, the inflection points were less distinct, requiring both software-based and manual evaluation.

Lithium soap model greases showed a pronounced extension of OIT by ZnDTP at the lower test temperature (140 °C), regardless of plate material. Compared with unadditivated greases, AO additives exhibited only limited effectiveness. It is known from laboratory studies that fully formulated urea greases often do not display a distinct inflection point [45]. In the present tests, urea model greases frequently exhibited only minor slope changes in the pressure–time curves, which were interpreted as inflection points. In several cases, however, no inflection-based OIT could be identified even after a pressure drop of 40%.

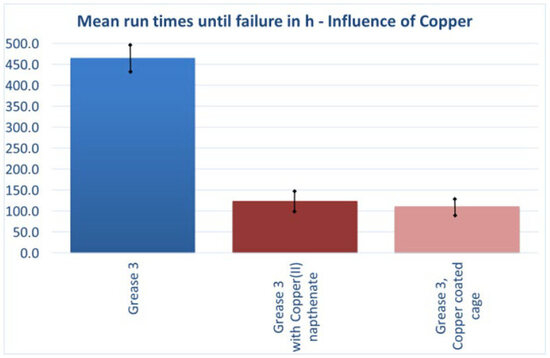

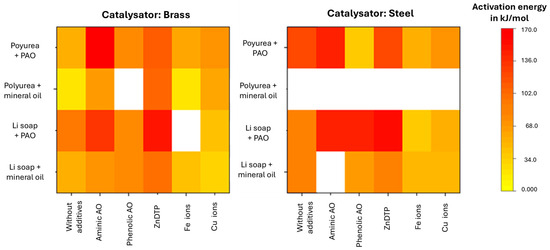

As required by the standard, OIT values determined for greases on steel and brass plates at three temperatures were transferred into an Arrhenius plot. The heatmap of activation energies (Figure 11) indicates that, for the model greases, especially the amine antioxidant and the secondary antioxidant ZnDTP acted to retard aging. If insufficient OIT inflection points were available up to 40% pressure drop, the corresponding heatmap fields were left blank.

Figure 11.

Heat map of activation energies according to Arrhenius for the Li soap fats and urea fats used here on steel and brass plates.

The aging process of urea greases has not yet been sufficiently researched to explain why, despite the consumption of oxygen from the surrounding atmosphere, there is no clear catastrophic aging with a dip in the pressure curve. One theory is that volatile reaction products form, which compensate for the pressure drop caused by oxygen consumption.

4.2.2. FTIR Measurements of Fresh Greases

Spectroscopic investigations were carried out using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy with attenuated total reflection (FTIR-ATR). In this method, a small sample quantity is applied to an optically dense crystal, and the evanescent wave of the interfering beam penetrates into the sample at the crystal interface. This excites molecular groups, whose vibrations are characteristic of specific bonds, allowing functional groups to be identified from the absorption bands in the spectrum.

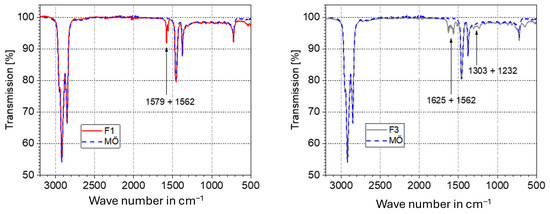

Comparison of spectra of fresh greases and their corresponding base oils revealed the typical thickener peaks: lithium soap thickener at 1579 and 1562 cm−1 and urea thickener at 1625 and 1562 cm−1 (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Comparison of spectra of fresh grease and mineral oil (MÖ) showing the thickener bands of Li soap grease (F1) and urea grease (F3).

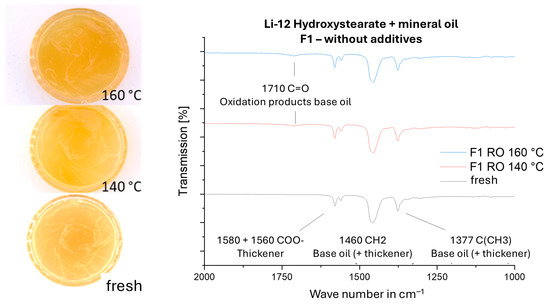

4.2.3. FTIR Measurements After RapidOxy Testing (DIN 51830-1)

After aging in the RapidOxy according to Part 1 of the standard, samples were analyzed by FTIR-ATR. Figures present waterfall diagrams comparing the spectra of fresh greases with those aged at 140 °C and 160 °C, focusing on the region of aging products (Figure 13 and Figure 14). Photographs of the grease dishes before and after thermo-oxidative testing in the RapidOxy are also included.

Figure 13.

FTIR spectra of fresh and aged grease F1 (lithium soap + mineral oil).

Figure 14.

Structures of fresh grease (left) and lithium soap grease aged on glass for 72 h (right).

The unadditivated lithium soap greases F1 and F2 reached the RapidOxy termination criterion after a short OIT. Consequently, only minor color changes were visible. FTIR-ATR spectra revealed weak newly formed peaks corresponding to the carbonyl group (C=O), characteristic of ketones, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids—typical oxidation products of base oils [46].

For urea greases, the 10% pressure drop termination criterion was reached only after approximately four times the runtime compared with lithium soap greases. The stronger aging was already evident from the visible discoloration of the samples in the dishes.

In the spectra of urea greases, progressive aging was associated with decreasing intensity of the NHR (alkylamino group) and CNH (nitrile group) peaks at 1632 cm−1 and 1585 cm−1, characteristic of the urea thickener. Layer-resolved analysis using the more sensitive FTIR transmission method with cuvette revealed superficial changes in the urea grease samples that did not extend into deeper layers. Oxygen diffusion appeared to be limited by surface varnish formation, likely due to polymerized oil. This effect also explained the reduction in thickener-related bands, since sampling was performed at the surface. In contrast, depth-resolved analysis of a lithium grease sample showed aging products throughout the entire layer, down to the bottom of the dish, indicating that oxygen penetrated into the bulk material.

4.3. Structural Characterization

A key project objective was to characterize in greater detail the influence of different stress conditions on the thickener structure. In addition to the chemical analyses described earlier (FTIR and TGA), two approaches were pursued: imaging techniques (3D digital microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), cryo-SEM, and atomic force microscopy (AFM)) and rheological characterization using various methods.

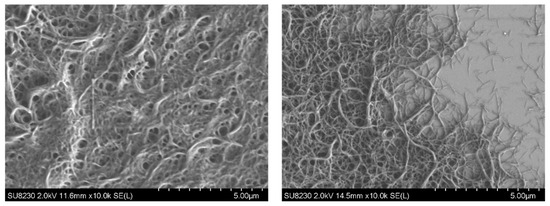

4.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Sample preparation at KTM followed procedures similar to those reported in previous studies. Base oil was extracted using the non-polar solvent n-hexane for lithium soap greases and acetone for urea greases. After drying, samples were gold-coated to ensure conductivity. SEM investigations proved difficult to interpret due to the required oil-extraction step. Oil removal appeared to cause agglomeration of the thickener into more compact structures in some greases, limiting the ability to resolve their native morphology. Stang et al. referred to this phenomenon as an “irreversible collapse of the thickener network” [47].

The SEM analysis was associated with high preparation effort and time consumption, yet differentiation between greases and their degradation states remained challenging. Some samples, such as lithium soap-thickened mineral oils, displayed a typical and well-defined fibrillar structure (Figure 14). In contrast, no characteristic structure could be identified in urea greases, making changes during aging nearly impossible to visualize. Even in lithium soap greases with clearly visible fibrils, only major structural changes—such as near-complete breakdown after shearing in the Klein apparatus—were readily apparent. Moderate aging or early degeneration was often manifested only as slight swelling of the fibers. A pronounced reduction in fiber length, as reported by Delgado or Zhou [12,28], could not be confirmed in the present samples by SEM. In cases of early polymerization, changes were instead reflected in the formation of agglomerates and new structural features.

The SEM images of lithium soap greases with PAO as base oil were unfortunately not informative. Despite numerous attempts, the base oil could not be cleanly extracted from the thickener. Similarly, no structural information or changes could be derived from the SEM images of the diurea greases.

Overall, it must be concluded that rheological investigations provided far greater insight into structural changes than the highly labor-intensive imaging techniques. Clear and interpretable structural images were primarily achievable for lithium soap greases based on mineral oil with thickener concentrations above 14% [13,29]. Consequently, the method cannot be considered suitable for all grease formulations.

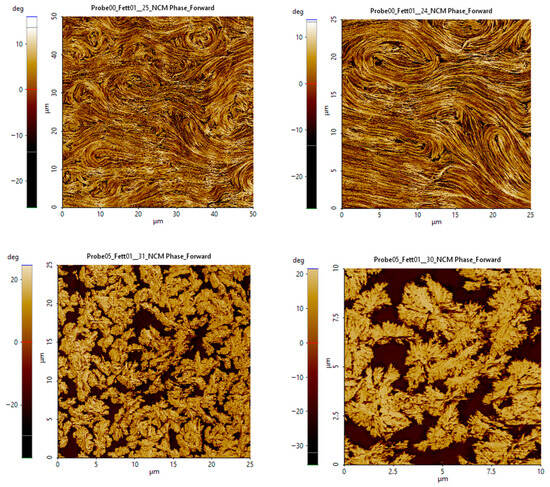

4.3.2. AFM Measurements

Cryo-SEM investigations at the Natural and Medical Science Institute (NMI) in Reutlingen, Germany, were originally planned in the project, with the aim of visualizing grease structures without the need for oil extraction. However, due to the very similar densities of oil and thickener, the method proved unsuitable. As an alternative, AFM measurements were performed by nanoAnalytics GmbH (Münster, Germany) for structural visualization. Based on the method of Roman et al. [40], the structure was exposed by carefully melting the sample surface.

Measurements were conducted in tapping mode (dynamic AFM). Two main signals were obtained: a topography signal (z-height) and a phase signal. The latter is particularly sensitive to differences in material hardness, allowing thickener and oil to be distinguished. In cases of pronounced degradation, the formation of new structures became visible (Figure 15). However, relatively minor changes—although clearly detectable by rheological methods—were not visually discernible or quantifiable.

Figure 15.

AFM images of degraded grease structure.

These investigations demonstrate that the significant time and cost of AFM are disproportionate to the insights gained. Therefore, AFM cannot be recommended for industrial or practical applications.

4.3.3. Rheological Structural Characterization

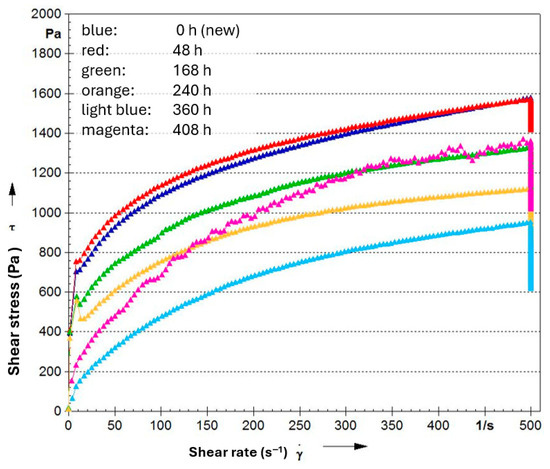

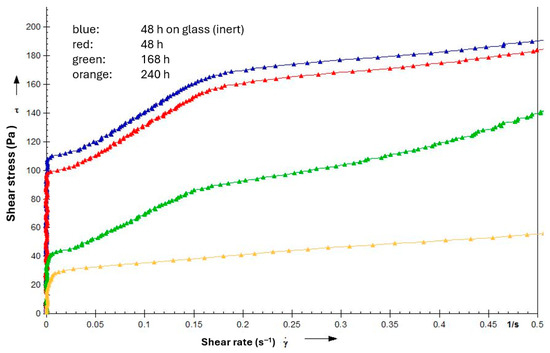

Rheological measurements were performed using an Anton Paar UDS200 rheometer. Flow curves were obtained in accordance with DIN 51810-1 [48]. Amplitude sweep tests were conducted according to DIN 51810-4 [49] to determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVE), loss and storage moduli, and yield stress.

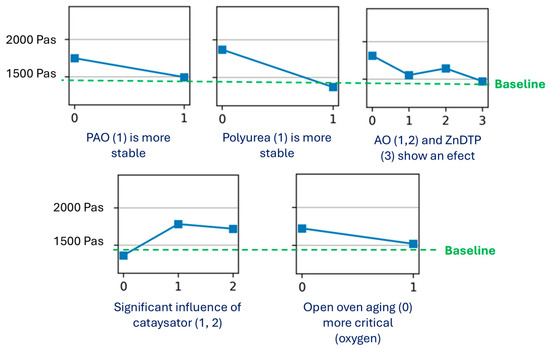

From project DGMK 788 it was already known that both the apparent viscosity in the plateau region and the yield stress change significantly during degradation [9]. The influence of degradation and aging is illustrated here using a representative model grease (lithium soap, NLGI grade 2, PAO base oil 100 cSt @ 40 °C, with 0.5% amine antioxidant, 0.5% phenolic antioxidant, and 1% ZnDTP). In principle, this behavior was observed for all tested model greases.

At the onset of degradation, the yield stress decreased markedly and in some cases disappeared entirely, such that the grease behaved almost like a Newtonian fluid. The typical rheological characteristics of grease were therefore completely lost. Figure 16 shows the shear stress versus shear rate (flow curve). Figure 17 provides a detailed view of yield stress evolution at very low shear rates at the beginning of the flow.

Figure 16.

Flow curves (shear stress over shear rate) for an NLGI 2 lithium soap grease based on PAO (100 cSt @ 40 °C) with 0.5% amine and phenolic antioxidants + 1% ZnDTP after different times at 140 °C on copper sheets in the oven.

Figure 17.

Flow curves at start for an NLGI 2 lithium soap grease based on PAO (100 cSt @ 40 °C) with 0.5% amine and phenolic antioxidants + 1% ZnDTP at 140 °C after different times on copper sheets in the oven.

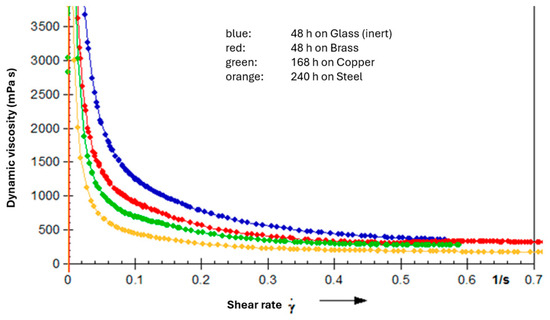

The apparent viscosity also decreased initially (Figure 18). After reaching a minimum, viscosity increased sharply again due to polymerization effects. Under these conditions, the grease may undergo complete varnishing, acquiring quasi-solid properties. In rheological measurements, this was evident from highly irregular curves (magenta-colored curve in Figure 15), caused by hard particles obstructing the measurement gap.

Figure 18.

Flow curves (viscosity vs. shear rate) for an NLGI 2 lithium soap grease based on PAO (100 cSt @ 40 °C) with 0.5% amine antioxidant, 0.5% phenolic antioxidant, and 1% ZnDTP on different catalyst plates in the oven (140 °C).

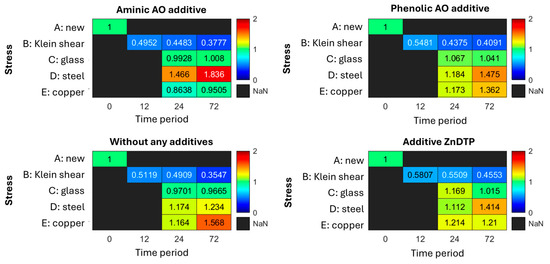

The diagrams in Figure 19 present the results as heatmaps. This visualization approach facilitates clear representation of the large dataset. Changes in the mean shear stress of aged greases are expressed as relative deviations compared with the fresh grease. Relative values below 1.0 indicate a decrease in viscosity, whereas values above 1.0 reflect an increase.

Figure 19.

Influence of additive addition on mechanical, thermal, and catalytic aging.

As expected, the addition of antioxidants and anti-wear additives had no effect on the mechanical load-bearing capacity under loading type B (Klein shear). It was observed that the amine antioxidant lost its ability to neutralize oxidation products on steel (row D) after a relatively short time, with this effect increasing markedly over time. A similar, though weaker and more gradual, behavior was observed for the phenolic antioxidant on steel. Interestingly, in several cases, the catalytic effect of steel appeared to be more critical than that of copper—a phenomenon already noted in the preceding project DGMK 788 [9].

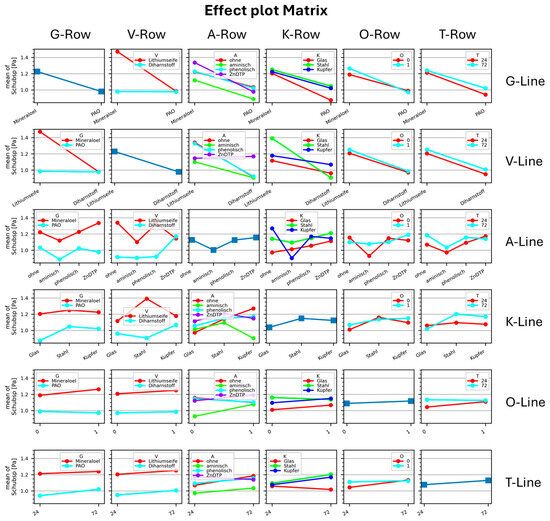

Due to the complex and multidimensional nature of the data, clear presentation of the results proved challenging. Therefore, in a subsequent work package, effect plots were employed to visualize the large number of experiments and to identify main effects and interactions. In addition, the factors base oil, thickener, additive, oxygen, and catalyst were evaluated for statistical significance.

5. Discussion

5.1. Statistical Analysis for Finding Correlations (Design-of-Experiments—DOE)

Within this research project, the results of Klein shear and oven-aging tests were analyzed using various DOE methods. Python PyCharm CE (Vers. 2022.2) was employed as the development environment.

Figure 20 illustrates, along the main diagonal, the effects of six factors—base oil, thickener, additive, catalyst, oxygen presence, and time—on the shear stress of the model greases. For clarity, this main diagonal is presented in detail in Figure 21. The off-diagonal plots depict the interactions between pairs of factors.

Figure 20.

Effect plot matrix for oven-aging experiments. Coding: G—base oil: 0 mineral oil, 1 PAO; V—thickener: 0 Li12OH, 1 diurea; A—additives: 0 none, 1 amine, 2 phenolic, 3 ZnDTP; K—catalyst: 0 none (glas), 1 iron, 2 copper; O—oxygen: 0 absent, 1 present; T—time: 24 h, 72 h.

Figure 21.

Analysis of the main effects after 72 h of oven aging.

A limitation of this purely statistical evaluation is that shear stress decreases during phase 1 (“dilution”) and increases during phase 2 (“polymerization”). When only the final state is analyzed, this temporal evolution is lost, potentially leading to misinterpretation. Another limitation is that all values for a given factor are averaged, which may result in positive and negative changes canceling each other out. This can mislead the observer into assuming that the investigated factor has no effect.

Comparing the findings from oven aging with the running times in the FE9 test (Figure 8), these findings can be clearly confirmed. The PAO-based greases tested always achieve a similar or longer service life than the mineral oil-based greases. Despite the higher test temperature in the FE9, the diurea greases tested always show a significantly longer service life than lithium soap greases. The antioxidants and ZnDTP used in this project are effective. The ZnDTP effect as a secondary antioxidant delivers better results than the primary antioxidants. The clear catalyst effect on the FE9 running time was clearly demonstrated using copper as an example [9].

5.2. Chemical Interpretation

The effects observed during oven aging can be explained chemically, as outlined by König, who represented Lanxess in the project advisory committee [46,50]. According to his description, lubricant aging begins with the formation of radicals. Radicals may be generated by heat (∆), light (hν), catalytic surfaces, or radical initiators. Since lubricants are rarely exposed to UV light, this factor can be neglected except for products used outdoors, such as chainsaw oils. In most cases, radical formation is triggered by thermal stress in combination with catalytically active elements. Catalytic surfaces include corroded metals capable of electron transfer, e.g.,

Fe(II)–Fe(III), Cu(0)–Cu(I)–Cu(II), Co(II)–Co(III), or Ag(0)–Ag(I).

The tests conducted on steel and copper plates provoked catalytic reactions both in oven-aging and in the RapidOxy test (DIN 51830 Part 2). Comparison with inert glass surfaces enabled separation of catalytic from purely thermo-oxidative effects, providing an important basis for potential mathematical modeling.

The second step of aging involves chain propagation and reaction with ambient oxygen, forming peroxide radicals. Oxygen is consumed, reducing the (partial) oxygen pressure—a key parameter measured in the RapidOxy test. Peroxide radicals can further react with hydrocarbons to form peroxides and new hydrocarbon radicals. Covered oven-aging tests were used to assess the influence of oxygen separately from thermal and catalytic effects.

The third step is the decomposition of peroxides into two radical species, which can initiate further cycles. Hydroxyhydrocarbons formed during this stage may be oxidized into ketones, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids by peroxides or oxygen. These transformations cause an increase in IR absorption at ~1760–1700 cm−1 (carbonyl region), an increase in acid number, and enhanced corrosion.

Without inhibition by additives, radical-induced aging in the presence of oxygen is a self-accelerating process. Decomposition of hydrocarbon radicals can yield smaller, volatile molecules, reducing viscosity. Alongside thickener network degradation during oven aging, this effect likely contributed to the viscosity decrease observed in the early stages of degradation. Conversely, recombination of radicals can produce larger, insoluble molecules, leading to sludge or deposits—consistent with the pronounced viscosity increase seen in the second degradation phase.

So-called radical scavengers, i.e., primary antioxidants, interrupt the chain reaction by converting radicals into stable, non-reactive species. In the case of sterically hindered phenols, the radical is delocalized over the aromatic system. After trapping a radical, the phenolic antioxidant can attach a hydrocarbon radical or hydroperoxide radical at the para-position, forming a typically well-soluble molecule. Intermediates and end products are generally yellow to brown in color, explaining why greases often show little visible discoloration (see Figure 4 and Figure 5).

In aromatic secondary amines, the radical is also delocalized over the aromatic system. After capturing a radical, the amine antioxidant may undergo different follow-up reactions depending on the environment:

Reaction with a peroxide species to form an N-oxide, where the radical is delocalized over the aromatic system. Further reaction with another peroxide species produces a quinonoid N-oxide. These intermediates and products are typically orange to red, occasionally causing slight grease discoloration.

Recombination of two aromatic amine radicals to form larger polycyclic aromatic amines, which can scavenge additional radicals. Due to their molecular weight, these polycyclic species may be insoluble in lubricants, promoting sludge or deposit formation.

Secondary antioxidants, such as zinc dialkyldithiophosphate (ZnDTP) used here as an EP additive, decompose peroxides before they split into radicals. In dithiophosphates, the anion undergoes oxidative coupling, and the resulting hydroxide ions can react with zinc to form salts that remain dispersed in the lubricant. Non-ionic dithiophosphate derivatives have also been shown to be effective peroxide decomposers. An additional benefit of ZnDTP is its ability to oxidize sulfur atoms (present in lower oxidation states than S(VI), e.g., in sulfur carriers used as EP additives) while reducing peroxides to hydroxyhydrocarbons.

Finally, corrosion inhibitors should be mentioned classified as tertiary antioxidants—even if they were not used in this project. They prevent corrosion of metal surfaces into catalytically active sites. For iron and steel, all corrosion inhibitors function as tertiary antioxidants. For cobalt, copper, and their alloys (brass, bronze), two inhibition mechanisms are relevant:

Triazoles and derivatives form protective films that prevent contact of corrosive agents (acids, air, amines, sulfur species, water) with the metal surface.

Thiadiazoles and derivatives do not form dense films on cobalt or copper but can scavenge free, aggressive sulfur from nonpolar lubricants, preventing corrosion.

Additionally, thiadiazoles, triazoles, and their derivatives can form insoluble, sticky complexes with cobalt or copper ions, thereby immobilizing them and removing them from the lubricant.

6. Conclusions

This collaborative project investigated the influence of mechanical, thermal, oxidative, and catalytic stresses on lubricating grease and its performance in rolling bearings. Through targeted provocation tests and a carefully designed experimental plan, the aim was to isolate the contributions of individual factors to grease degradation and to describe their interactions. Various Design-of-Experiment (DOE) and statistical evaluation methods were applied to visualize the complex results.

The model greases studied represent formulations of high industrial relevance: they were based on Li-12-hydroxystearate and diurea thickeners, each combined with mineral oil or PAO as base oils. In addition to unadditivated base greases, model greases were prepared with a specific amine or phenolic antioxidant as well as an anti-wear/EP additive.

The planned analytical methods were evaluated for their suitability in characterizing grease aging. Numerous tests were carried out on both fresh greases and aged samples. Particular attention was paid to the catalytic effects of metals encountered in grease–bearing contact. The introduction of metallic ions was simulated by conditioning selected model greases with Fe and Cu ions. Catalytic aging was further investigated by oven-aging on metal plates and by RapidOxy testing on metallic substrates (DIN 51830-2), thereby assessing the impact of direct grease–metal contact under thermal stress.

A broad range of measurements and analyses were conducted. However, almost every grease sample exhibited unique properties and performance, making it difficult to derive universally valid conclusions. TGA and DSC analyses revealed differences among the greases, but no single quantitative parameter emerged as sufficiently meaningful for extended evaluation. FTIR and visual analyses provided limited additional insight. SEM imaging showed interpretable thickener structures only for lithium soap greases, and even there, moderate degradation effects were barely detectable or objectively assessable. AFM, which avoids oil extraction, provided intriguing images but again yielded limited interpretability and correlation with aging state. In contrast, rheological measurements proved to be far simpler, faster, and more informative. In combination with the newly developed RapidOxy test standard (DIN 51830-2) and oven-aging, these methods provided initial practical approaches to predicting grease lifetime and potentially remaining useful life. Promising laboratory studies are currently ongoing with industry and academic partners within the DIN standards committee NA 652 [45]. It may also be worth exploring whether mechanical loading, represented by Klein shear, can be incorporated into such lifetime calculations.

The project set out to obtain reliable insights into how grease thickener structures change during aging and mechanical loading, how these changes can be detected, and how they influence lubrication, performance, and bearing life. This objective was achieved, although many questions remain, and only a small fraction of commercially available grease formulations could be examined. Importantly, a test strategy has now been established that enables lubricant developers to conduct targeted investigations tailored to their specific products and their application.

The present results are a first step toward gaining a better understanding of the changes in grease during operation. However, it should be noted that only a few model greases were examined here. In addition, for reasons of time and cost, only minimal statistics could be obtained. FE9 tests are usually performed with at least 5-fold statistics in order to calculate a Weibull distribution. For these reasons, it would be premature to make final recommendations. Another DGMK project (DGMK 871—Use of machine learning in lubricating grease evaluation [51]) is currently underway, which builds on the approaches presented here. The sample greases were selected and produced specifically for the purpose of this study. Since the focus is on the use of machine learning, the statistics will also be significantly increased. We hope to be able to make more detailed and well-founded statements after this project.

A deeper understanding of the mechanisms, influencing factors, and their impact on lubrication will help especially SMEs with specialized products to reduce development costs and lead times while enabling the creation of high-performance greases even for niche markets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.G.; methodology: M.G.; investigation: M.R., D.K. and N.E.; data curation: M.R., D.K. and N.E.; writing—original draft preparation: M.G. and D.K.; writing—review and editing: M.G. and D.K.; visualization: M.G. and D.K.; supervision: M.G.; project administration: M.G. and D.K.; funding acquisition: M.G. and D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The IGF project (21251 N) of the Research Association Deutsche Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft für nachhaltige Energieträger, Mobilität und Kohlenstoffkreisläufe e.V., Große Elbstraße 131, 22767 Hamburg, was funded via the AiF within the framework of the Industrial Collective Research Program (IGF) by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) on the basis of a resolution of the German Bundestag.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| AO | Antioxidant |

| DGMK | German Scientific Society for Sustainable Energy Sources, Mobility, and Carbon Cycles e.V. in German: “Deutsche Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft für nachhaltige Energieträger, Mobilität und Kohlenstoffkreisläufe e.V.”, Hamburg, Germany, |

| DOE | Design of Experiments |

| FE9 | Roller Bearing Test Rig “FE9” acc. DIN 51821 |

| FTIR | Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GfT | German Scientific Society for Tribology, in German: Gesellschaft für Tribologie, Jülich |

| KTM | Mannheim Competence Center for Tribology at Mannheim Technical University of Applied Sciences; in German: Kompetenzzentrum Tribologie Mannheim |

| MPWP | Multi station roller bearing test right (in German: “MehrPlatzWälzlagerPrüfstand”) |

| NLGI | National Lubricating Grease Institute |

| OIT | Oxidation Induction Time |

| OWI | OWI Science for Fuels gGmbH—non-profit research institute affiliated with RWTH Aachen University |

| PAO | Poly-Alpha-Olefine |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| RWTH | in German: Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule (Aachen University) |

| XRF | X-Ray Fluorescence Measurement |

| ZnDTP | Zinc dialkyldithiophosphate |

References

- Beck, J. In Zeiten von Industrie 4.0 erst recht: Gute Schmierung will gelernt sein. Tribol. Schmier. 2019, 66, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- HCP-Sense. Bearing Damage: Identify Causes Early & Avoid Bearing Failure. Available online: https://www.hcp-sense.com/en/tech-corner/bearing-damage-identify-causes-early-avoid-bearing-failure/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Kleinlein, E. (Ed.) Einsatz von Wälzlagern bei Extremen Betriebs- und Umgebungsbedingungen: Optimierung Durch Geeignete Konstruktion und Entwicklung von Wälzlagern, Schmierung und Abdichtung; Expert-Verlag: Renningen–Malmsheim, Germany, 1998; Volume 574. [Google Scholar]

- DIN ISO 281; Wälzlager—Dynamische Tragzahlen und Nominelle Lebensdauer. DIN-Media: Berlin, Germany, 2010.

- Matzke, M.; Dornhöfer, G.; Schöfer, J. Quantitatively-Accelerated Testing of Grease Oxidation—A Parameter Study with the RapidOxy. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Gesellschaft für Tribologie (GfT), Göttingen, Germany, 23–25 September 2019; Gesellschaft für Tribologie: Jülich, Germany, 2019; p. 428, ISBN 978-3-9817451-4-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, V.; Krewer, M.; Poll, G. Effects of parasitic currents and electrical discharges on rolling bearings and their service life in electrified environment. Lubricants 2024, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebe, M.; Ruland, M. Influence of Mechanical, Thermal, Oxidative, and Catalytic Processes on Thickener Structure and Thus on the Service Life of Rolling Bearings. Lubricants 2022, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 51821; Prüfung von Schmierstoffen—Prüfung von Schmierfetten auf dem FAG-Wälzlagerfett-Prüfgerät FE9, 51821. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2016.

- Grebe, M.; Müller, C.; Eiden, S.; Hiesinger, S. Entwicklung einer Screening-Prüfmethode für Schmierfette durch Kopplung von Thermo-Oxidativen Prüfverfahren mit einem Mechanisc-Dynamischen Mehrplatz-Wälzlagerprüfstand; DGMK: Hamburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dornhöfer, G. Ermittlung der Schmierfettgebrauchsdauer mit Zeitraffender Prüfmethode und Übertragbarkeit auf Reales Temperaturkollektiv. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of GfT, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 13–14 November 2016; Gesellschaft für Tribologie: Jülich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, E. Modellierung zum Schmierfettverschleiß im Stationären Reibungsprozess. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Gesellschaft für Tribologie (GfT), Göttingen, Germany, 25–27 September 2017; Gesellschaft für Tribologie: Jülich, Germany, 2017. ISBN 978-3-9817451-2-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Bosman, R.; Lugt, P.M. A Model for Shear Degradation of Lithium Soap Grease at Ambient Temperature. Tribol. Trans. 2018, 61, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodapp, A.; Conrad, A.; Hochstein, B.; Jacob, K.-H.; Willenbacher, N. Effect of Base Oil and Thickener on Texture and Flow of Lubricating Greases: Insights from Bulk Rheometry, Optical Microrheology and Electron Microscopy. Lubricants 2022, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugt, P.M. Grease Lubrication in Rolling Bearings, 1st ed.; Tribology in Practice Series; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aikin, A.A. The art of manufacturing grease—Research is ongoing to develop improved products. Tribol. Lubr. Technol. (TLT) 2020, 76, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.M. Mixing rheometry for studying the manufacture of lubricating greases. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 2409–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, S.; Cann, P.M.; Spikes, H.A. Lubrication and Reflow Properties of Thermally Aged Greases. Tribol. Trans. 2000, 43, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E. Investigations into the Degradation of the Structure of Lubricating Greases. Tribol. Trans. 1998, 41, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, P.M. Grease Degradation in a Bearing Simulation Device. Tribol. Int. 2006, 39, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, P.M.; Webster, M.N.; Doner, J.P.; Wikstrom, V.; Lugt, P.M. Grease degradation in R0F bearing tests. Tribol. Trans. 2007, 50, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.Q.; Yang, Z.G. Fatigue Failure Analysis of a Grease-Lubricated Roller Bearing from an Electric Motor. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2011, 11, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhvaryu, A.; Sung, C.; Erhan, Z. Fatty Acids and Antioxidant Effects on Grease Microstructures. Ind. Crops Prod. 2005, 21, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couronne, I.; Vergne, P. Rheological Behavior of Greases: Part II—Effect of Thermal Aging, Correlation with Physico-Chemical Changes. Tribol. Trans. 2000, 43, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, D.; Graça, B.; Campos, V.; Saebra, J.; Leckner, J.; Westbroek, R. Formulation, Rheology and Thermal Ageing of Polymer Greases—Part I: Influence of the Thickener Content. Tribol. Int. 2015, 87, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Hu, M.H.; Liu, R.G.; Liu, Q.L. The Influence of Static Thermal Degradation on Microstructure and Rheological Properties of Lithium–Calcium Base Grease. Tribology 2011, 31, 581–586. [Google Scholar]

- Dokter, J.; Osara, J.A. On the Thermal Degradation of Lubricant Grease: Degradation Analysis. J. Tribol. 2025, 148, 024603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, J. Structural Degradation of a Lithium Lubricating Grease after Thermal Ageing. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2016, 49, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.A.; Sánchez, M.C.; Valencia, C.; Franco, J.M.; Gallegos, C. Relationship Among Microstructure, Rheology and Processing of a Lithium Lubricating Grease. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2005, 83, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.A.; Valencia, C.; Sánchez, M.C.; Franco, J.M.; Gallegos, C. Influence of Soap Concentration and Oil Viscosity on the Rheology and Microstructure of Lubricating Greases. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezasoltani, A.; Khonsari, M. On the Correlation between Mechanical Degradation of Lubricating Grease and Entropy. Tribol. Lett. 2014, 56, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D8206-18; Oxidation Stability of Lubricating Greases—Rapid Small Scale Oxidation Test (RSSOT), D8206. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Höger, O. Protokoll NAK “Alterungsbeständigkeit von Schmierfetten”—DIN 51808/DIN 51830. Fachausschuss Mineralöl- und Brennstoffnormung—FAM Within Normenausschuss Materialprüfung (NMP) of DIN, Berlin, Protokoll with Attachments, April 2025. Available online: https://docs.din.de/din-documents/ui/#!/browse/din/54764014 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- DIN 51830-2:2025-02; Prüfung von Schmierstoffen—Bestimmung der Oxidationsbeständigkeit von Schmierfetten—Teil_2: Ermittlung der Temperaturabhängigen Oxidation Induction Time zur Berechnung der Aktivierungsenergie der Thermo-oxidativen Degradation. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [CrossRef]

- DIN 51830-1:2022-10; Prüfung von Schmierstoffen—Bestimmung der Oxidationsbeständigkeit von Schmierfetten—Teil_1: Beschleunigtes Verfahren. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Baart, P.; Van Der Vorst, B.; Lugt, P.M.; Van Ostayen, R.A.J. Oil-Bleeding Model for Lubricating Grease Based on Viscous Flow Through a Porous Microstructure. Tribol. Trans. 2010, 53, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyriac, F.; Lugt, P.M.; Bosman, R.; Padberg, C.J.; Venner, C.H. Effect of Thickener Particle Geometry and Concentration on the Grease EHL Film Thickness at Medium Speeds. Tribol. Lett. 2016, 61, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, S.; Cann, P.M. Examination of grease structure by SEM and AFM techniques. NLGI Spokesm. 2001, 65, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Magnin, A.; Piau, J.M. Application of freeze-fracture technique for analyzing the structure of lubricant greases. J. Mater. Res. 1989, 4, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.C.; Franco, J.M.; Valencia, C.; Gallegos, C.; Urquiola, F.; Urchequi, R. Atomic Force Microscopy and Thermo-Rheological Characterisation of Lubricating Greases. Tribol. Lett. 2011, 41, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, C.; Valencia, C.; Franco, J.M. AFM and SEM Assessment of Lubricating Grease Microstructures: Influence of Sample Preparation Protocol, Frictional Working Conditions and Composition. Tribol. Lett. 2016, 63, 20–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.S.; Harsha, A.P.; Chouhan, A. Effect of Graphene-Based Nanoadditives on the Tribological and Rheological Performance of Paraffin Grease. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 2235–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Meehan, P.A. Microstructure Characterization of Degraded Grease in Axle Roller Bearings. Tribol. Trans. 2019, 62, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, H. Abschlussbericht zum DGMK-Vorhaben 809: Untersuchungen zur Bestimmung der Verteilung von Stoffbestandteilen in Schmierfetten; DGMK: Hamburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, D.; Matta, C.; Thijssen, R.; Yusof, M.N.; van Eijk, M.C.P.; Chatra, S. Novel polymer grease microstructure and its proposed lubrication mechanism in rolling/sliding contacts. Tribol. Int. 2017, 110, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.; Bayer-Faiß, S.; Höger, O.; Grebe, M. Thermo-oxidative grease service life evaluation—laboratory study with the catalytically accelerated method using the RapidOxy. Tribol. Schmier. 2022, 69, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, M.; UNITI, Dortmund, Germany. Grundlagen der Tribologie, training material within the course „Technischer Mineralölkaufmann/Technische Mineralölkauffrau“, module 2. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Salomonsson, L.; Stang, G.; Zhmud, B. Oil/Thickener Interactions and Rheology of Lubricating Greases. Tribol. Trans. 2007, 50, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 51810-1; Prüfung von Schmierstoffen—Prüfung der Rheologischen Eigenschaften von Schmierfetten—Teil 1: Bestimmung der Scherviskosität mit dem Rotationsviskosimeter und dem Messsystem Kegel/Platte, 51810–1. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- DIN 51810-4:2021-04; Prüfung von Schmierstoffen_-Bestimmung der Konsistenz von metallverseiften Schmierfetten mit dem Oszillationsrheometer und dem Messsystem Kegel/Platte. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [CrossRef]

- König, M.; DiNicala, K.; Lanxess, Mannheim, Germany. Introduction into mechanisms, testing and products, internal training materials. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tidona, G.; Grebe, M. Einsatz von maschinellem Lernen in der Schmierfettentwicklung (DGMK 871). In Proceedings of the Status Report at the “DGMK Lubricant Day”, Virtual, 11 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).