Abstract

Background/Objectives: Advance care planning is essential in a community; however, intervention studies by care managers remain scarce. This study aims to determine the relationship between frailty and post-traumatic stress disorder among long-term care service users (hereinafter referred to as “users”) following advance care planning conversations with their care managers. Methods: We conducted a secondary analysis using raw data from the Japanese University Hospital Medical Information Network Study No. 000048573, published on 23 September 2024. In this previous study, trained care managers provided advance care planning conversation interventions to 30 users. Care managers conducted a convenience sample of 30 mentally and physically stable users who were 65 years old or older, had a family member or healthcare provider assigned, and had never used ACP. Our analysis in the present study focuses on the Clinical Frailty Scale and Impact of Events Scale-Revised, both of which measure post-traumatic stress disorder. Results: The Impact of Events Scale-Revised score was significantly higher in users with a clinical frailty score ≥ 5 compared to those with a clinical frailty score < 5. Logistic regression analysis, using the Impact of Events Scale-Revised as the objective variable, also revealed an association between a clinical frailty score ≥ 5 and a higher Impact of Events Scale-Revised. The four groups, selected through hierarchical cluster analysis for sensitivity analysis, demonstrated results consistent with the above analysis. Conclusions: The degree of post-traumatic stress disorder among users is associated with their degree of frailty following an advance care planning conversation with their care manager. Frailty in users may be a valuable predictor of stress related to advance care planning conversations. Users with a clinical frailty scale score ≥ 5 can be provided with more personalized care through more careful communication. University Hospital Medical Information Network Trial ID: 000048573.

1. Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is necessary for older adults in a community [1,2]. However, although the concept of ACP is ideal, its implementation is complex, resulting in a significant gap between the ideal and actual practice [3]. Furthermore, ACP is strongly influenced by cultural differences, and replicating ACP practices from Europe and the United States is challenging. This has led to difficulties in ACP progress [4].

In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare guidelines were significantly revised in 2018 to bridge the gap between the ideal and actual ACP. The guidelines previously positioned doctors, nurses, and social workers as the primary professionals promoting ACP; however, the revised version now includes care managers. Previously, the primary role of a care manager was to coordinate home care services under long-term care insurance. With this revision, ACP has been incorporated into the care manager’s responsibilities [5].

Following the revision of these guidelines, we developed an ACP training program—the ACPiece program—that is both appropriate and culturally relevant for care managers in Japan [6,7]. This program was developed owing to a lack of research on the role of care managers. Although reports on care managers in ACP are limited globally, previous studies have the potential for sharing ACP tasks with care managers [8]. These studies suggest that care managers can practice and improve their engagement with ACP, albeit imperfectly [9,10]. A Japanese study suggested the possibility of involving care managers in ACP within the context of multidisciplinary collaboration [11].

Subsequently, we published two papers on ACPiece. First, we reported an improvement in care managers’ positive attitudes toward dying patients before and after participating in the ACPiece program [12]. Second, we reported that ACP engagement improved, and that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was not a significant factor before and after the engagement of care managers in ACP conversations with long-term care service users [13]. Notably, the representative values (mean and median) of PTSD scores for all cases were below the cutoff values, although some cases exceeded the cutoff values [13]. This study was called the CMACP-PPP study [13,14].

The protocol [14] for this study [13] excluded cases where PTSD was expected following the ACP intervention. The ACPiece used in this study was designed to minimize the invasiveness of ACP communication using communication skills such as repetition and silence [6,7]. However, some long-term care service users still exhibited high PTSD scores [13]. We explored the factors contributing to high PTSD scores. Subsequently, we conducted a narrative review of the PubMed database using ACP- and PTSD-related search terms. We focused on frailty-related terms as emerging keywords during the search process. PTSD is a post-traumatic stress state, while frailty is a state in which the body and mind function poorly and become less resilient to stress with age [15].

After searching PubMed for frailty- and PTSD-related terms, we focused on two articles. These studies reported an interrelationship between frailty and PTSD [15], with frail patients being more likely to experience PTSD when evaluated 1 year after recovering from hospitalization due to COVID-19 [16]. Nevertheless, the number of studies is limited, highlighting the research gap in this field.

Furthermore, when ACP- and PTSD-related terms were used as search terms in the PubMed database, we focused on five articles. All five articles discussed the stress of the surrogate decision-maker rather than the long-term care service user. Specifically, some studies reported that ACP implementation improved PTSD in the surrogate [17,18,19], whereas others reported no relationship between ACP implementation and PTSD [20]. Additionally, some reports suggest that the tendency for PTSD among surrogate decision-makers in ACP is linked to personality traits [21]. This highlights a research gap regarding the PTSD of the user, rather than the surrogate decision-maker, following ACP implementation.

When searching PubMed using ACP and frailty as search terms, 11 articles were identified. Some studies did not thoroughly discuss the relationship between frailty and ACP, but highlighted that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) predicts life expectancy [22,23], is a good indicator of ACP initiation [24,25], that higher CFS scores are associated with higher rates of ACP initiation [26], and that conservative treatment of ACP is more often chosen in the CFS-measured group [27].

Previous studies have reported that a mild degree of frailty is more likely to be associated with ACP implementation [28]; however, frailty evaluation alone does not necessarily lead to ACP implementation [29]. Among the studies that evaluated individuals’ wishes, one study [30] stated that the high-CFS group was more likely to focus on how to live rather than on how to die during ACP conversations compared with the low-CFS group. In contrast, another study [31] found no association between the degree of CFS and congruence between the wishes of the individual and those of the family. Another study [32] stated that frail older people must consider their present and future wishes on a continuum, as they seek to live well in the present. Although studies relating ACP to frailty are relatively abundant, their findings vary. We were motivated by new insights into the extent of frailty and PTSD: (1) after ACP communication, (2) by care managers, and (3) by the users themselves, rather than their surrogates.

Therefore, this study aims to clarify the relationship between frailty and PTSD in long-term care service users when care managers, who are responsible for coordinating home care services in the community, engage in ACP conversations with long-term care service users, in collaboration with multiple professionals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of ACP

As stated by the Japan Geriatrics Society, ACP is a process that supports people in making decisions and accords respect to each individual as a human being, regarding their future medical and long-term care needs [33].

2.2. Ethical Consideration

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (approval number: 1619). It adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in Brazil in 2013. Care managers verbally explained the study to the participants, providing a written description, and obtained their written consent.

2.3. Study Design

This study conducted a secondary analysis of a comparative pre- and post-intervention study conducted by trained care managers. An approximately 1 h ACP communication intervention was conducted, adhering to the content of the developed ACPiece program. The ACPiece program is described in detail in previous reports [6,7,12,13]. This initiative includes a short lecture, hands-on training, scenario analysis, role-playing, and collaborative activities. It was created to assist Japanese long-term care service users in expressing their hidden emotions and viewing care managers as empathetic partners. This is especially important in Japan, where genuine emotions are frequently unexpressed. In ACPiece, these emotions are termed “pieces”. The program enhances communication among care managers who excel at recognizing the emotions of long-term care service users but often find it challenging to address future healthcare decisions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Contents of the ACPiece program.

2.4. Survey Procedure

A total of 30 participants engaged in ACP conversations with care managers and completed questionnaires on ACP engagement and PTSD in the original study. The study protocol was finalized by August 2022, and study information was obtained from the University Hospital Medical Information Network in Japan (study ID: 000048573) [14]. The research commenced on 15 September 2022. The final participant was recruited on 8 December 2022, with follow-ups concluding on 26 January 2023; the findings were published on 23 September 2024 [13]. In the present study, we conduct a secondary analysis using the raw data from this published paper, focusing specifically on frailty and PTSD.

2.5. Participants

Participant details are included in the previous report [13]. To summarize, nine care managers participated in ACP discussions with 30 users receiving long-term care services after completing the ACPiece program. Each of the nine care managers selected three to four users through convenience sampling. The criteria for including long-term care service users were as follows: users assigned to a care manager, those over 65 years of age, individuals capable of communicating about ACP, users with family members available to discuss ACP, and those with a healthcare provider who could engage in ACP discussions. The exclusion criteria included users with a previous history of ACP, those considered mentally unstable by their care managers and unsuitable for ACP intervention or surveys, users whose physical conditions made ACP undesirable, and those whose care managers’ interventions had lasted less than 12 weeks. Care managers were careful not to select users under a lot of stress based on this criterion. Users with prior ACP experience were excluded to prevent adjustments based on their past ACP involvement. Despite efforts to exclude mentally unstable users, participants with high PTSD scores were included, as their inclusion could not be avoided.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of long-term care service users and care managers. Further details can be found in a previous study [13]. In summary, 15 (50%) long-term care service users exhibited a CFS score of 1–4, whereas 15 (50%) exhibited a CFS score of 5–9. All 30 long-term care service users completed an approximately 60 min ACP conversation with their care managers. Although a second ACP conversation was not prohibited, only one ACP conversation was conducted. Care managers consistently took great care to ensure that communication remained stress-free for users during the conversation regarding advocate selection, life-prolonging treatment choices, user values, matters related to their lives, and relationships with their family members.

Table 2.

Characteristics of long-term care service users and care managers.

2.6. Questionnaires and Measurement

The questionnaire and measurements are detailed in a previous study [13]. The primary endpoint, the ACP engagement score [35,36], was measured both before and after the ACP discussion, while the secondary endpoint, the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) score [37,38], which assesses PTSD, was evaluated following the ACP discussion. The IES-R is a 22-item questionnaire tested for reliability and validity in Japanese; it includes eight items for intrusion, eight for avoidance, and six for hyperarousal. For internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha must range from 0.92 to 0.95 for the upper scale and from 0.80 to 0.91 for the lower scale [38]. Given that this was a pilot study, the sample size was determined to be 30 participants to ensure statistical validity [39,40].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed for participants who agreed to participate in the study and who completed questionnaires before and after the ACP discussion with the care manager. There were no missing data. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages.

In the previous study [13], data from the IES-R of 30 participants, measured as secondary endpoints, were analyzed as follows. First, the relationship among the CFS [34], a representative rating scale for frailty, and the IES-R, a representative rating scale for PTSD, was examined. The participants were classified into two groups based on the CFS score, inferring from past literature that CFS scores above or below a certain threshold have different clinical relevance [13,25,26,30]. For effect sizes, an effect size, r, that could be adapted to nonparametric data was measured, with an effect size of ≥0.1 considered small, ≥0.3 medium, and ≥0.5 large [41]. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. In addition, the median, minimum, maximum, first and third quartiles, and 95% confidence intervals are presented. For the sensitivity analysis, the Mann–Whitney U and Brunner–Munzel tests were conducted. Second, logistic regression analysis was performed to determine whether the IES-R was affected by confounding factors other than CFS. The IES-R scores were dichotomized using the median score as the reference. Lastly, a hierarchical cluster analysis was used for the sensitivity analysis. Participants were divided into statistically significant groups, the clinical significance of each group was examined, and multiple comparisons between the groups were made. For multiple comparisons, the Tukey method was used for parametric data and the Kruskal–Wallis method was used for nonparametric data.

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 MSO (version 2022) provided by Microsoft Corporation, USA and EZR version 1.55 [42]. The reporting for this study conformed to the guidelines of the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) [43]. The checklists developed according to these guidelines are presented as the Supplementary File S1.

3. Results

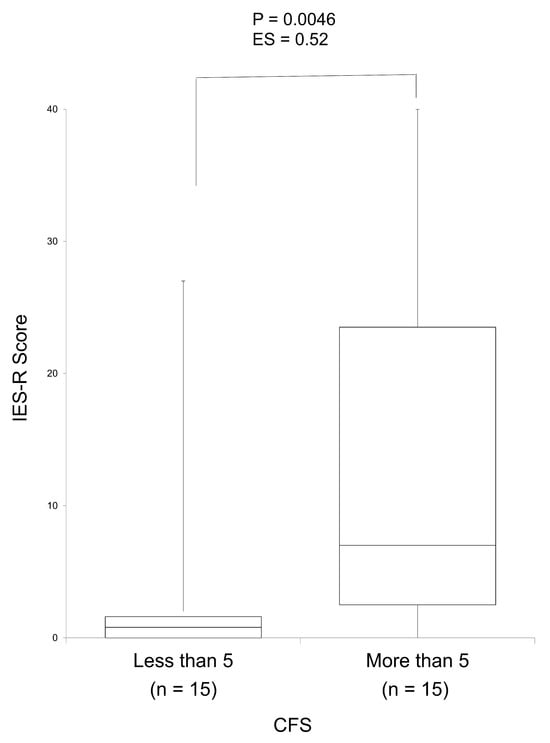

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the CFS and the IES-R as a measure of PTSD. Notably, the IES-R score was significantly higher in the group with a CFS of ≥5 than in the group with a CFS of <5. The effect size was large. IES-R scores were not measured before ACP communication between users and care managers but only after.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the CFS and IES-R as a measure of post-traumatic stress disorder using a box-and-whisker plot. The group with a CFS of greater than 5 had a statistically significantly higher IES-R score than the group with a CFS lower than 5 (p = 0.0046). The effect size was also large (ES = 0.52). The maximum, third quartile, median, first quartile, minimum, mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals for the group with a CFS lower than 5 were 27.0, 2.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 4.1, 8.5, and −6.3–8.8, respectively, while they were estimated at 40.0, 23.5, 7.0, 2.5, 0.0, 13.4, 13.2, and 6.1–20.7, respectively, for the group with a CFS greater than 5. ES, effect size; SD, standard deviation; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; IES-R, Impact of Event Scale-Revised; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale.

Table 3 presents the logistic regression analysis results with a dichotomized IES-R score of <3 or ≥3 as the objective variable. A CFS score of ≥5 was associated with a higher IES-R score. The other explanatory variables were assumed to have no apparent effect on the IES-R scores.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis using Impact of Events Scale-Revised as the objective variable (n = 30).

Four groups were selected from the hierarchical cluster analysis based on users with increasing mean IES-R scores and the percentage of users with a CFS of ≥5. Multiple comparisons among these groups revealed the following characteristics. Group 1 consisted of younger users with longer relationships with care managers. Group 2 showed no obvious characteristics. Group 3 comprised older care managers. Group 4 consisted of care managers with fewer years of experience (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multiple comparisons among the four clusters identified through hierarchical cluster analysis (n = 30).

4. Discussion

This is the first study to reveal an association between the degree of PTSD in long-term care service users and their degree of frailty, based on an ACP conversation between users and their care managers. The IES-R score, which determines the level of PTSD, was not measured before ACP communication between users and care managers, but only after.

The most important finding of this study is the possibility of predicting high PTSD scores in users, who could not be excluded from ACP conversations in advance or terminated mid-conversation, based on their degree of frailty, which can be assessed relatively quickly. Specifically, care managers find it difficult to exclude such users in advance or terminate ongoing ACP conversations due to the characteristics of Japanese people, who value their relationships with others and may not express their feelings clearly [4]. In Japan, culture is a complex context, and users want care managers to understand their true emotions without having to express them. Thus, even when users perceive that they are under stress and do not want to communicate with their care manager, they may want the care manager to understand their true emotions without reporting them to the care manager [44]. This trend is uncommon in Western countries [44]. Although previous studies have discussed the relationship between frailty and PTSD [15,16], no studies have examined their relationship during ACP conversations with a care manager. In this study, we found a relationship between frailty and PTSD during ACP conversations between users and their care managers. Notably, PTSD scores are high among relatively young users with advanced frailty.

The second important finding is the addition of evidence on the PTSD scores of long-term care service users themselves, rather than those of the surrogate decision-makers. Although previous studies have focused on the PTSD scores of surrogate decision-makers after ACP [17,18,19,20], none have examined the PTSD scores of care service users themselves. Our study found an association between the PTSD scores of care service users after ACP and their degree of frailty. This finding is more important in Japan than in Western countries. This is because, in Japanese culture, understanding the true emotions of long-term care service users is challenging [44].

Interestingly, our study revealed that the CFS can serve as an indicator of both the benefits and disadvantages of ACP. Although previous research has reported that a CFS score of ≥5 promotes ACP engagement [13], the present study suggests that a CFS score of ≥5 may result in a high IES-R score, which may be a disincentive to engage in ACP. Studies have also reported CFS as a good indicator of ACP initiation [24,25], and that higher CFS scores are associated with higher rates of ACP initiation [26]. Additionally, conservative treatment with ACP is more frequently chosen in the CFS group [27]. Our results indicate that a CFS score of ≥5 is a good indicator for ACP initiation and that care managers should be mindful of not stressing care service users during these conversations. Therefore, a high CFS score can be a factor that both promotes and inhibits ACP. This finding aligns with the conclusions of previous studies [28,29], which indicate that the presence or absence of a CFS assessment, as well as a CFS score, does not necessarily lead to ACP implementation. Therefore, we must continue daily stress-free communication training for long-term care service users, using the CFS as a communication guide during ACP discussions.

One of the key strengths of this study is that it fills a research gap in community-based ACP intervention studies led by care managers. Our findings demonstrate that ACP conversations can be effectively initiated using CFS, a relatively easy-to-assess indicator, as a guidepost. Establishing procedures to use CFS assessments in ACP communication to reduce psychological stress is essential. The implications of the main findings for practical use are as follows: users with a CFS of ≥5 can receive more personalized care through more careful communication. However, it is necessary to clarify the type of communication that is careful.

Future research should first include a qualitative study exploring the stress associated with ACP conversations between long-term care service users and care managers based on the degree of users’ frailty. In addition, a randomized controlled trial should be conducted with respect to ACP conversations with care managers trained in the ACPiece program as the intervention group, stratified by CFS values of <5 and ≥5, as both the existing literature [13] and our study indicate that adjustments for confounding factors are needed.

A small sample size could be a limitation of this study. Furthermore, as this intervention study did not include a control group, it may have introduced a selection bias among the long-term care service users who participated. Additionally, we did not measure stress levels before the ACP intervention.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights that the degree of PTSD in long-term care service users is associated with their degree of frailty, as revealed through ACP conversations between the users and their care manager. The main finding of this study is that the degree of frailty among long-term care service users may predict stress due to ACP conversations. The implications of the main findings for practical use are as follows: users with a Clinical Frailty Scale score of ≥5 can receive more personalized care through more careful communication. We should conduct a qualitative study on what constitutes more careful ACP communication and then conduct comparative research stratified by CFS values of ≥5 vs. <5.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jpm15040159/s1, File S1: Reporting checklist for quality improvement in health care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., K.O., S.O., T.K., H.K., and M.N.; methodology, M.M., K.O., S.O., T.K., H.K. and M.N.; investigation, M.M., K.O., S.O., N.T., T.N., T.M., M.O., Y.K., T.I. and M.N.; formal analysis, M.N.; founding acquisition, H.K. and M.N.; resources, M.M., K.O., S.O., N.T., T.N., T.M., M.O., Y.K., T.I. and M.N.; software, M.N.; project administration, M.M., K.O., S.O. and M.N.; data curation, M.M., K.O., S.O., N.T., T.N., T.M., M.O., Y.K., T.I. and M.N.; validation, M.N.; visualization, M.M., K.O., S.O. and M.N.; supervision, T.K. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, M.M., K.O., S.O., N.T., T.N., T.M., M.O., Y.K., T.I., T.K., H.K. and M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology’s Longevity Sciences program (22-20, 22-28).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (approval number: 1619, approved date: 2 August 2022). It adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in Brazil in 2013.

Informed Consent Statement

Care managers verbally explained the study to the participants, providing a written description, and obtained their written consent. All participants agreed to the publication of this study.

Data Availability Statement

Upon reasonable request, the datasets that were created and/or examined in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Mariko Miyamichi is affiliated with Yorozu Soudanjyo Co., Ltd., the position of Mariko Miyamichi in the company is manager. Yorozu Soudanjyo Co., Ltd. has no role in the manuscript, and there are no potential conflicts. All the other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACP | Advance care planning |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| CFS | Clinical Frailty Scale |

| IES-R | Impact of Events Scale-Revised |

References

- Gao, F.; Chui, P.L.; Che, C.C.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, Q. Advance care planning readiness among community-dwelling older adults and the influencing factors: A scoping review. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietjens, J.A.C.; Sudore, R.L.; Connolly, M.; van Delden, J.J.; Drickamer, M.A.; Droger, M.; van der Heide, A.; Heyland, D.K.; Houttekier, D.; Janssen, D.J.A.; et al. Definitions and recommendations for advance care planning: An international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e543–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, R.S.; Meier, D.E.; Arnold, R.M. What’s wrong with advance care planning? JAMA 2021, 326, 1575–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; Chan, H.Y.; Lin, C.P.; Kim, S.H.; Ng, H.; Lip, R.; Martina, D.; Yuen, K.K.; Cheng, S.Y.; Takenouchi, S.; et al. Definition and recommendations of advance care planning: A Delphi study in five Asian sectors. Palliat. Med. 2024, 10, 02692163241284088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. A Guideline on the Decision-Making Process in End-Of-Life Care. 2018. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/04-Houdouhappyou-10802000-Iseikyoku-Shidouka/0000197701.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Oshiro, K. Advance Care Planning—Piece. 2018. Available online: http://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~acp-piece/piece.html (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Nishikawa, M.; Oshiro, K. Introduction to ACP-A Guide on How to Get Started With ACP-Piece (Freely Translated From Japanese to English); Nikkei BP Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tilburgs, B.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Koopmans, R.; Weidema, M.; Perry, M.; Engels, Y. The importance of trust-based relations and a holistic approach in advance care planning with people with dementia in primary care: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detering, K.M.; Carter, R.Z.; Sellars, M.W.; Lewis, V.; Sutton, E.A. Prospective comparative effectiveness cohort study comparing two models of advance care planning provision for Australian community aged care clients. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2017, 7, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, S.S.; Ritchie, C.; Volow, A.; Li, B.; McSpadden, S.; Dearman, K.; Kotwal, A.; Rebecca, L. Sudore A toolkit for community-based, Medicaid-funded case managers to introduce advance care planning to frail, older adults: A pilot Study. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki, T.; Yamashita, D.; Miura, C.; Nakamura, M.; Izumi, S.S. Feasibility and acceptability of advance care planning facilitated by nonphysician clinicians in Japanese primary care: Implementation pilot study. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2023, 24, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, K.; Okochi, S.; Nakashima, J.; Hirano, T.; Ohe, S.; Kojima, H.; Nishikawa, M. Changes in care managers’ positive attitudes toward dying patients compared to that of nurses by one-day online advance care planning communication training. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2024, 18, 26323524231222497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okochi, S.; Oshiro, K.; Takeuchi, N.; Miyamichi, M.; Nakamura, T.; Matsushima, T.; Okada, M.; Kudo, Y.; Ishiyama, T.; Kinoshita, T.; et al. Effects of intervention by trained care managers on advance care planning engagement among long-term care service users in Japan: A pre- and post-pilot comparative study across multiple institutions. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2024, 18, 26323524241281065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umin, C.T.R. Clinical Trial Registration Information. 2022. Available online: https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000055290 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Zhou, Y.; Duan, J.; Zhu, J.; Huang, Y.; Tu, T.; Wu, K.; Lin, Q.; Ma, Y. Qiming Liu Casual associations between frailty and nine mental disorders: Bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. BJPsych Open 2025, 11, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braude, P.; McCarthy, K.; Strawbridge, R.; Short, R.; Verduri, A.; Vilches-Moraga, A.; Hewitt, J. Ben Carter Frailty is associated with poor mental health 1 year after hospitalization with COVID-19. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 310, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, T.R. Giving up on the objective of providing goal-concordant care: Advance care planning for improving caregiver outcomes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 3006–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.K.; Ward, S.E.; Fine, J.P.; Hanson, L.C.; Lin, F.C.; Hladik, G.A.; Hamilton, J.B.; Bridgman, J.C. Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: A randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 66, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detering, K.M.; Hancock, A.D.; Reade, M.C. William Silvester The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2010, 340, c1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.-K.; Manatunga, A.; Plantinga, L.; Metzger, M.; Kshirsagar, A.V.; Lea, J.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Jhamb, M.; Wu, E.; Englert, J.; et al. Effectiveness of an advance care planning intervention in adults receiving dialysis and their families: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2351511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, B.; Foy, A.; Van Scoy, L. Relationships between personality traits and perceived stress in surrogate decision-makers of Intensive Care Unit patients. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2024, 41, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittang, B.R.; Øien, A.T.; Engtrø, E.; Skjellanger, M.; Krüger, K. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes for elderly patients in a dedicated Covid-19 ward at a primary health care facility in western Norway: A retrospective observational study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, F.I.; Turcotte, L.; Strum, R.P.; de Wit, K.; Griffith, L.E.; Worster, A.; Foroutan, F.; Heckman, G.; Hebert, P.; Schumacher, C.; et al. Prognostic association between frailty and post-arrest health outcomes in patients receiving home care: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Resuscitation 2023, 187, 109766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamatani, Y.; Teramoto, K.; Ikeyama-Hideshima, Y.; Ogata, S.; Kunugida, A.; Ishigami, K.; Minami, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Takamoto, M.; Nakashima, J.; et al. Validation of a supportive and palliative care indicator tool among patients hospitalized due to heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 2025, 31, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Itabashi, M.; Taito, K.; Izawa, A.; Ota, Y.; Tsuchiya, T.; Matsuno, S.; Arai, M.; Yamanaka, N.; Saito, T.; et al. Usefulness of assessment of the Clinical Frailty Scale and the Dementia Assessment Sheet for Community-based Integrated Care System 21-items at the time of initiation of maintenance hemodialysis in older patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welford, J.; Rafferty, R.; Short, D.; Dewhurst, F.; Greystoke, A. Personalised assessment and rapid intervention in frail patients with lung cancer: The impact of an outpatient occupational therapy service. Clin. Lung Cancer 2023, 24, e164–e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasinghe, A.P.; Chakera, A.; Chan, K.; Dogra, S.; Broers, S.; Maher, S.; Inderjeeth, C.; Jacques, A. Incorporating the Clinical Frailty Scale into routine outpatient nephrology practice: An observational study of feasibility and associations. Intern Med. J. 2021, 51, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukue, N.; Naito, E.; Kimura, M.; Ono, K.; Sato, S.; Takaki, A.; Ikeda, Y. Readiness of advance care planning among patients with cardiovascular disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 838240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, S. Exploring whether a diagnosis of severe frailty prompts advance care planning and end of life care conversations. Nurs. Older People 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iki, H.; Nakamura, A.; Watanabe, K.; Harada, H.; Oshiro, K.; Hiramatsu, A.; Nishikawa, M. End-of-life preference lists as an advance care planning tool for Japanese people. Home Healthc. Now 2024, 42, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Jin, G.; Chen, M.; Xie, X.; Shen, S.; Qiao, S. Prevalence and factors of discordance attitudes toward advance care planning between older patients and their family members in the primary medical and healthcare institution. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1013719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, S.; Gillett, K.; Norton, C.; Nicholson, C.J. The importance of living well now and relationships: A qualitative study of the barriers and enablers to engaging frail elders with advance care planning. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Geriatrics Society Subcommittee on End-of-Life Issues; Kuzuya, M.; Aita, K.; Katayama, Y.; Katsuya, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Hirahara, S.; Miura, H.; Rakugi, H.; Akishita, M. Japan Geriatrics Society “recommendations for the promotion of advance care planning”: End-of-life issues subcommittee consensus statement. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitnitski, A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudore, R.L.; Heyland, D.K.; Barnes, D.E.; Howard, M.; Fassbender, K.; Robinson, C.A.; Boscardin, J.; You, J.J. Measuring advance care planning: Optimizing the advance care planning engagement survey. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 669–681.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, H.; Takenouchi, S.; Okuhara, T.; Ueno, H.; Kiuchi, T. Development of a Japanese version of the advance care planning engagement survey: Examination of its reliability and validity. Palliat. Support Care 2021, 19, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.S. The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In Cross-Cultural Assessment of Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Tang, C.S., Eds.; International and Cultural Psychology Series; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asukai, N.; Kato, H.; Kawamura, N.; Kim, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Kishimoto, J.; Miyake, Y.; Nishizono-Maher, A. Reliability and validity of the Japanese-language version of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R-J): Four studies of different traumatic events. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2002, 190, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, R.H. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat. Med. 1995, 14, 1933–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujang, M.A.; Omar, E.D.; Foo, D.H.P.; Hon, Y.K. Sample size determination for conducting a pilot study to assess reliability of a questionnaire. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2024, 49, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrinc, G.; Davies, L.; Goodman, D.; Batalden, P.; Davidoff, F.; Stevens, D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, J.; Shimizu, S.; Shiraishi, R.; Mori, M.; Okawa, K.; Aita, K.; Mitsuoka, S.; Nishikawa, M.; Kizawa, Y.; Morita, T.; et al. Culturally Adapted Consensus Definition and Action Guideline: Japan’s Advance Care Planning. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 64, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).