Abstract

Background: Cardiotoxicity is a major limitation of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for thoracic and systemic cancers, contributing significantly to morbidity and mortality among survivors. Early prediction and prevention are critical to balance oncologic efficacy with cardiovascular safety. Artificial intelligence (AI) offers powerful tools to improve risk stratification, enable earlier detection of subclinical injury, and guide treatment planning in cardio-oncology. Methods: We performed a comprehensive review of the literature on AI applications for cancer therapy-related cardiotoxicity. Evidence was identified from PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, focusing on electrocardiography, biomarkers, proteomics, extracellular vesicles, genomics, advanced imaging (echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance, computed tomography, nuclear imaging), and radiotherapy dose modeling (dosiomics). Translational insights from animal models and in vitro systems were also included. Methodological quality was appraised with reference to TRIPOD-AI, PROBAST-AI, and CLAIM standards. Results: AI applications span multiple domains. Machine learning models integrating biomarkers, exosomes, and extracellular vesicles show promise for noninvasive early detection. Deep learning enables automated analysis of echocardiographic strain and cardiac MRI mapping, while radiomics and dosiomics approaches combine imaging with cardiac substructure dose maps to predict and prevent late radiation-induced injury. Preclinical studies demonstrate AI-driven advances in small-animal imaging, histopathology quantification, and multi-omics data integration, supporting the discovery of translational biomarkers. Despite encouraging performance, most models remain limited by small cohorts, methodological heterogeneity, and scarce external validation. Conclusions: AI has the potential to transform cardio-oncology by shifting from reactive detection to proactive prevention of cardiotoxicity. Future research should prioritize multimodal integration, harmonized multicenter datasets, prospective validation, and guideline-based clinical trials. As emerging data are incorporated, the field is expanding rapidly—dynamic, complex, and evolving.

1. Introduction

Cancer and cardiovascular diseases are among the most important causes of death worldwide. The World Cancer Research Fund International reported 18.7 million cancer cases in the year 2022, with breast and lung cancer being the most frequent [1].

Moreover, cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death in cancer survivors, among the ~17 million cancer survivors in the United States [2]. Evidence indicates that individuals with cancer face a two- to six-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality compared with the general population. As advances in oncology continue to reduce cancer-related deaths, the importance of comprehensive cardiovascular assessment and management becomes even more pronounced. Effectively addressing cardiovascular risk is now a critical component of optimizing long-term outcomes for cancer patients and survivors [3].

Cardiovascular toxicity—often referred to as cardiotoxicity—is defined by the 2022 European Society of Cardiology Cardio-Oncology guidelines as injury to the heart muscle or broader cardiovascular system resulting from cancer therapies. Although treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation are integral to effective cancer management, they can inadvertently impact cardiac health. These effects span a wide spectrum, from subtle, asymptomatic changes in cardiac performance to severe and potentially life-threatening complications, including heart failure. While most cardiotoxic complications arise during or shortly after treatment, some cancer therapies can lead to cardiac events that emerge many years—even decades—after therapy has ended [4].

Conventional chemotherapies, as well as endocrine therapies, targeted or immunotherapies, and radiation therapy can all cause cardiovascular toxicities [4]. Among individuals undergoing cancer therapies—including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted agents—approximately 20% may develop some degree of myocardial dysfunction, with an estimated 7–10% progressing to cardiomyopathy or heart failure [5]. Remarkable advances in cancer therapy have significantly improved long-term survival. However, these gains are increasingly tempered by cardiovascular complications associated with treatment, which can lead to therapy interruptions, reduced tolerance of cancer regimens, and ultimately worse oncologic and cardiovascular outcomes [6]. Before starting any cancer treatment, a comprehensive baseline evaluation should be made and optimization of the treatment and pre-existing cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and/or CV disease is recommended [4]. There is a pressing need to develop non-invasive, accesible and low-cost tools for the early identification of survivors at risk for cardiovascular disease, to facilitate optimal screening, timely diagnosis, and early intervention.

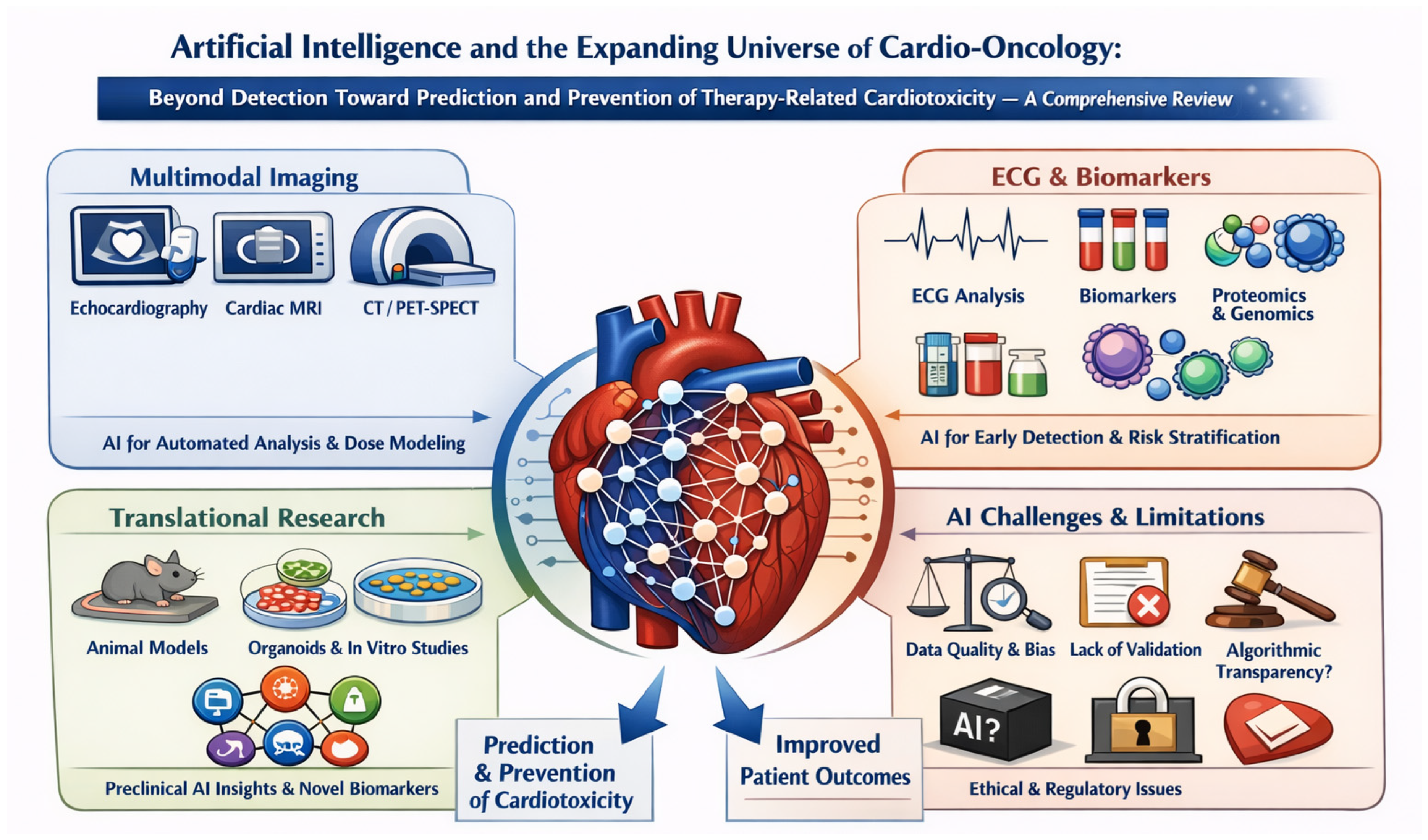

As many patients with cancer undergo frequent surveillance imaging and other diagnostic testing, a substantial amount of clinical data is generated that could be leveraged to assess an individual’s risk for cardiovascular complications of therapy. Over time, this growing volume of structured and unstructured information—spanning imaging, laboratory values, ECGs, clinical notes, genomics and proteomics—offers an underused opportunity to develop more accurate and dynamic risk prediction tools, particularly when integrated with advanced analytical methods such as machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of current and emerging applications of artificial intelligence in cardio-oncology for the prediction and prevention of therapy-related cardiotoxicity.

Several risk-assessment and prediction tools are currently in use or under development to help identify patients at heightened risk for cardiotoxicity and guide clinical management. Incorporating the vast amount of clinical, imaging, and molecular data that can be leveraged by AI could further accelerate the development of more refined, dynamic, and easily applicable cardiotoxicity prediction scores, ultimately enhancing their utility in real-world practice. Consequently, the field of AI-assisted precision cardio-oncology is rapidly advancing toward greater personalization and precision, with a strong focus on early prevention and individualized treatment before, during, and after cancer therapy [7].

2. Cancer Therapy-Related Cardiotoxicity: An Overview

Anthracyclines are among the most widely used and effective chemotherapeutic agents for a broad spectrum of malignancies—including breast cancer, sarcomas, leukemias, and lymphomas—where they play a central role in achieving high response rates and improving survival. However, their clinical utility is constrained by a well-recognized risk of cardiotoxicity, which can manifest acutely during treatment or years later, potentially leading to irreversible cardiac dysfunction. Cardiac dysfunction in this setting refers to a spectrum of structural and functional changes in the heart, most notably a reduction in its ability to pump blood efficiently. This often appears as a decline in left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) or abnormalities in myocardial strain, changes that may progress to symptomatic heart failure if not promptly identified [8].

Another very commonly used chemotherapeutic agent, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and its metabolic precursor, capecitabine, are fluoropyrimidines used in various cancer treatments, with cardiotoxicity typically manifesting during the first chemotherapy cycle. This cardiotoxicity, most often presenting as chest pain due to coronary vasospasm, can also lead to more severe complications such as myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and sudden cardiac death. The phenomenon appears infrequent but genuine, independent of dose, and may be related to continuous infusion schedules. To date, classic cardiac risk factors do not reliably predict its occurrence. Therefore, patients receiving 5-FU should be closely monitored, and treatment should be discontinued if cardiac symptoms develop [9].

Paclitaxel and docetaxel, microtubule-targeting agents commonly used to treat breast, head and neck, and gastrointestinal cancers, have been associated with cardiotoxic effects, including abnormal cardiac conduction. Cardiotoxicity related to these taxanes occurs in approximately 2.3% to 8% of patients and may manifest as bradycardia, atrioventricular block, hypotension, arrhythmias, and ventricular dysfunction [10,11].

Cyclophosphamide-induced cardiotoxicity is a significant concern, particularly when administered at high doses, and is primarily linked to its toxic metabolite acrolein. This metabolite promotes pathological changes such as myocyte necrosis, inflammation, and cardiac hypertrophy, contributing to cardiomyopathy and heart failure [12].

Cisplatin and other platinum derivatives are widely used chemotherapeutic agents effective against multiple malignancies, but their clinical utility is limited by renal and cardiac toxicities. Cardiotoxicity manifests as electrocardiographic changes and various arrhythmias, including ventricular arrhythmias, supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation (AF), occasional sinus bradycardia, and complete atrioventricular block. Additionally, cisplatin-induced endothelial damage, inflammation, and apoptotic pathways contribute to myocardial injury, with downstream cardiac remodeling and degeneration [13].

Trastuzumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting HER2, commonly used in HER2-positive breast cancer. While effective, it can cause reversible cardiotoxicity, primarily manifesting as heart failure and decreased left ventricular function. This cardiotoxicity results from HER2 inhibition, which disrupts cardiac cell survival pathways, leading to oxidative stress and myocyte dysfunction. Unlike anthracycline-induced damage, trastuzumab-related effects are often reversible with treatment cessation and can be managed with cardiac monitoring and protective therapies [14].

Angiogenesis inhibitors can cause adverse effects such as hypertension, thrombosis, QT interval prolongation, and left ventricular dysfunction. The latter may result partly from direct cardiomyocyte toxicity worsened by hypertension [15].

Ibrutinib, a potent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor for B-cell lymphomas, is associated with an increased incidence of AF, ranging from 4% to 16%, with a median onset around 2.8 months after starting therapy. New-onset AF in cancer patients elevates the risk of heart failure and thromboembolism. Management is challenging due to drug interactions with common AF therapies. Clinicians should be vigilant for AF development and consider tailored algorithms for management in patients receiving ibrutinib [16].

Proteasome inhibitors like carfilzomib have significantly advanced multiple myeloma treatment but are associated with notable cardiovascular adverse events. These include heart failure, systemic and pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmias, and acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovascular risks are heightened, with heart failure and hypertension being common, and events often occur early during treatment, typically within the first three months [17].

There is evidence that estrogen deprivation caused by aromatase inhibitors (such as anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane) and selective estrogen receptor modulators like tamoxifen, used to treat early and advanced breast cancers, may increase the risk of ischemic heart disease. Long-term use of aromatase inhibitors for four years or more has been associated with a higher risk of ischemic heart disease and arrhythmias compared to shorter exposure or no treatment. However, the overall risk of fatal cardiovascular events appears low, and findings emphasize the importance of cardiovascular risk assessment and monitoring during endocrine therapy [18,19].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) activate T cells to enhance the immune response against cancer cells, but can cause myocarditis, a rare yet potentially fatal immune-related adverse event. ICI-associated myocarditis often occurs within weeks of treatment initiation and may present with cardiac symptoms, arrhythmias, or be asymptomatic. It involves autoimmune infiltration and inflammation of the myocardium [20].

Cardiotoxicity from radiation therapy (RT) can present as nearly all forms of cardiovascular disease, with atherosclerosis being the most common. RT causes endothelial damage, oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis, promoting accelerated atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. Other complications include pericarditis, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathies, conduction abnormalities, and heart failure. These effects may appear months to years after treatment, depending on the specific cardiac pathology, RT dose, and patient risk factors. Advanced RT techniques aim to minimize heart exposure to reduce these risks, but the results in the long term are still to be determined [21,22].

3. Why Artificial Intelligence in Cardio-Oncology?

AI applications in cardio-oncology span a wide range of domains and are rapidly transforming both research and clinical practice. Machine learning (ML) models are being developed to integrate diverse sources of data—including circulating biomarkers, advanced imaging modalities and radiomics, electrocardiograms (ECGs), as well as genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles. By combining these multidimensional datasets, AI enables a more comprehensive understanding of cardiovascular risk and treatment response in cancer patients. In addition, preclinical studies using animal models are increasingly incorporating AI-driven analytics to uncover novel mechanisms of cardiotoxicity and to accelerate the development of preventive or therapeutic strategies.

Moreover, an important advantage of AI lies in its ability to minimize subjectivity in data interpretation. By providing consistent, automated analyses, AI reduces both intra- and inter-observer variability, leading to more objective, reproducible, and reliable results. This consistency is particularly valuable in cardio-oncology, where subtle changes in imaging, biomarkers, or physiological signals can have critical implications for early diagnosis and treatment decisions.

AI in cardio-oncology requires understanding its different forms. ML encompasses algorithms that identify patterns in data to make predictions or classifications without explicit rule-based programming. Model performance largely depends on the quality and relevance of manually selected features informed by domain expertise. Classical ML methods—such as logistic regression, random forests, support vector machines, and gradient boosting—have been extensively applied in cardiovascular and oncologic research to predict treatment-related cardiotoxicity. These models can integrate clinical, laboratory, and imaging data to estimate, for example, the risk of anthracycline-induced ventricular dysfunction or ICI–related myocarditis. ML approaches perform best with structured datasets of moderate size and remain relatively interpretable, allowing clinicians to discern key predictive factors [23]. In ML, the input dataset is typically divided into three subsets: a training set, a validation set, and a test set. The training set, usually the largest portion, is used to develop and fit the model. The validation set is then applied to monitor performance during development and to optimize the model’s parameters. Finally, the test set—composed of previously unseen data—is used to provide an unbiased evaluation of the model’s overall performance and its ability to generalize to new samples [24].

On the other hand, Deep learning (DL), a subset of ML, employs artificial neural networks with multiple interconnected layers, enabling automatic learning of complex hierarchical features—hence the term “deep.” Architectures such as convolutional, recurrent, and transformer networks can process unstructured data, including medical images, ECG waveforms, and genomic sequences, without manual feature engineering. In cardio-oncology, DL has advanced automation in echocardiographic segmentation, strain analysis, and cardiac MRI mapping, facilitating earlier detection of subclinical myocardial injury [25].

Quer et al. pointed out different approaches in using AI for the interpretation of different investigations and event prediction. Traditional rules-based algorithms rely on explicitly programmed rules to interpret data, such as computerized ECG interpretation, where the decision-making process is fully understood. In contrast, ML algorithms learn patterns from data. Supervised learning uses labeled examples (e.g., ECGs with known diagnoses) to automatically identify features that predict outcomes, though it is limited by the provided labels. Unsupervised learning finds patterns in unlabeled data, clustering examples based on inherent similarities, similar to a medical student classifying ECGs without prior instruction. Reinforcement learning involves iterative feedback from the environment to improve predictions over time [26]. The most frequently used techniques in ML and DL generally fall within the two primary categories of ‘supervised learning’ and ‘unsupervised learning’. One example of this approach is the unsupervised development of models that identify key patient characteristics using electronic health record data [27].

After development, an algorithm must be validated on a separate dataset that it has not seen before. Common validation metrics include: (1) discrimination, which measures the model’s ability to distinguish between different outcomes (typically reported as the area under the curve [AUC] or c-statistic), and (2) calibration, which assesses how closely the model’s predicted risks match the observed outcomes. This step is crucial to ensure the algorithm provides reliable, high-quality data applicable to real-world clinical practice [28,29].

TRIPOD-AI, PROBAST-AI, and CLAIM are emerging standards designed to improve the transparency, quality, and reliability of artificial intelligence research in healthcare. TRIPOD-AI extends the original TRIPOD reporting guideline to address the specific challenges of developing and validating AI-based prediction models, ensuring that studies provide enough detail for reproducibility, critical appraisal, and clinical translation [30]. PROBAST-AI complements this by offering a structured framework to assess the risk of bias and applicability of AI-driven prediction tools, accounting for issues such as data handling, algorithmic transparency, and validation methods [31]. Meanwhile, the CLAIM (Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging) guideline provides standardized reporting requirements for AI studies in medical imaging, promoting rigor in data curation, model development, evaluation, and clinical integration [32]. Together, these frameworks help align AI research with robust methodological and reporting standards, facilitating safer and more trustworthy implementation of AI tools in clinical practice.

Precision medicine moves beyond a one-size-fits-all approach by tailoring healthcare to patient subgroups based on genetic, environmental, and experiential variability, aiming to optimize outcomes, reduce adverse effects, and enable personalized monitoring and interventions. Increasingly, AI is amplifying this paradigm by integrating vast and heterogeneous datasets.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Review Design

This manuscript was designed as a comprehensive narrative review aimed at providing a clinically oriented overview of current and emerging applications of artificial intelligence in cardio-oncology, with a focus on cancer therapy–related cardiotoxicity. Given the marked heterogeneity of study designs, populations, AI methodologies, data modalities, and outcome definitions in this rapidly evolving field, a formal systematic review or meta-analysis was not considered methodologically appropriate. Instead, a structured narrative approach was adopted to ensure broad coverage, clinical interpretability, and translational relevance.

4.2. Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in the following electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science.

The search strategy incorporated relevant keywords and combinations thereof, including: cardio-oncology; cancer therapy–related cardiotoxicity; artificial intelligence; machine learning; deep learning; echocardiography; cardiac magnetic resonance; computed tomography; nuclear imaging; electrocardiography; radiomics; dosiomics; biomarkers; proteomics; genomics; extracellular vesicles.

Evidence was identified focusing on applications in electrocardiography, biomarkers, proteomics, extracellular vesicles, genomics, advanced imaging (echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance, computed tomography, and nuclear imaging), and radiotherapy dose modeling (dosiomics). Translational insights from animal models and in vitro systems were also included. In addition, the reference lists of relevant reviews and key original articles were manually screened to identify further pertinent studies.

4.3. Inclusion Criteria

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

- Investigated applications of artificial intelligence, machine learning, or deep learning in the prediction, detection, monitoring, or prevention of cancer therapy–related cardiotoxicity or cardiovascular complications in oncology.

- Included any study type, including clinical, translational, preclinical, in silico, or in vitro studies.

- Addressed at least one of the following domains: cardiovascular imaging, electrocardiography, biomarkers, multi-omics, extracellular vesicles, or radiotherapy dose modeling.

- Presented original research or methodologically relevant translational studies.

- Used artificial intelligence for prediction, classification, segmentation, risk stratification, data integration, or decision support in a cardio-oncology–relevant context.

- Were published in peer-reviewed journals.

- No strict restrictions were applied regarding publication date in order to ensure a broad and comprehensive overview of the field.

4.4. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria:

- Duplicate publications or overlapping reports from the same study population, in which case the most complete or most recent version was retained.

- Articles whose title and abstract did not indicate a clear focus on artificial intelligence applications in cardio-oncology or cancer therapy–related cardiovascular toxicity.

- Papers discussing artificial intelligence in oncology or cardiology without relevance to cardiotoxicity or cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy.

- Studies unrelated to medical or biomedical applications.

- Patents, book chapters, editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces, and non–peer-reviewed literature.

4.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

From each selected study, we extracted information on the clinical context, data modality, artificial intelligence methodology, clinical task, validation strategy, reported performance metrics, and main limitations. The evidence was synthesized thematically and by modality, emphasizing clinical relevance, translational potential, and methodological trends rather than quantitative pooling of results.

4.6. Methodological Quality Considerations

Given the variable methodological quality and reporting standards in the artificial intelligence literature, studies were critically appraised with reference to TRIPOD-AI, PROBAST-AI, and CLAIM guidelines. These frameworks were used to contextualize common limitations, including small cohort sizes, risk of bias, lack of external validation, incomplete reporting, and limited assessment of calibration and clinical utility, rather than to formally exclude studies.

4.7. Rationale for Narrative Approach

This field is characterized by rapid technological evolution, heterogeneous methodologies, and a predominance of exploratory and proof-of-concept studies. Under these circumstances, a narrative synthesis was considered more appropriate than a systematic review or meta-analysis, allowing a broader, clinically meaningful, and integrative perspective while explicitly highlighting both opportunities and current limitations.

For clarity and synthesis, the main studies discussed in this review are summarized in modality-specific comparative tables covering echocardiography (Table 1), cardiac magnetic resonance (Table 2), computed tomography and radiomics/dosiomics (Table 3), nuclear medicine imaging (Table 4), electrocardiography (Table 5), and multimodal/translational approaches including biomarkers, genomics, proteomics, and extracellular vesicles (Table 6), highlighting for each domain the clinical task, AI methodology, study population, validation strategy, and reported performance.

5. AI in Cardiovascular Imaging

AI is being explored to enhance the precision, speed, and accuracy of LVEF and global longitudinal strain (GLS) assessment, assist in point-of-care image acquisition, and integrate imaging with clinical data to improve prediction and early detection of cardiac dysfunction. Additionally, AI applications in cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR), computed tomography (CT)—particularly coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring—as well as nuclear medicine. Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging are emerging as promising tools for evaluating cardiac tumors and cardiovascular complications in both pediatric and adult cancer survivors [7].

5.1. Echocardiography

In cardio-oncology, AI has significant potential in echocardiography, supporting image classification, reconstruction, automated segmentation and quantification, and risk prediction through integration of clinical data [33].

Before cancer treatment: AI can play a critical role in the baseline cardiac assessment of patients prior to initiating potentially cardiotoxic therapies. Through automated analysis of echocardiographic parameters such as LVEF and GLS, AI can establish accurate and reproducible reference values. Moreover, AI algorithms can detect subtle structural or functional cardiac abnormalities that may not be readily apparent to the human eye, thereby enhancing diagnostic precision and improving the identification of patients at higher risk for future cardiotoxicity. Early identification of these risks can support more informed treatment planning and the implementation of preventive strategies [34]. During cancer treatment: throughout therapy, AI enables continuous or periodic cardiac monitoring by automating the measurement of LVEF and GLS, ensuring timely detection of even minimal changes in cardiac function. By integrating imaging findings with other clinical and biochemical data, AI can help predict cardiovascular outcomes and flag early signs of cardiotoxicity, allowing clinicians to intervene before irreversible damage occurs. Additionally, AI-assisted point-of-care imaging can standardize acquisition quality across institutions and operators, improving consistency in serial follow-up studies [34]. And finally, after cancer treatment, in the survivorship phase, AI continues to be valuable for long-term cardiac follow-up. Automated assessment tools can track functional recovery or progression of cardiac dysfunction over time and identify late-onset cardiotoxic effects that may emerge months or years after treatment completion. By integrating longitudinal imaging data with clinical and omic profiles, AI can help stratify survivors according to cardiovascular risk and guide personalized surveillance and prevention strategies [34].

By training convolutional neural networks (CNNs), Zhang was able to carry out image segmentation to pinpoint cardiac chambers and derive measurements of heart structure and function for constructing disease-classification algorithms. Zhang’s method is designed to unlock data mining and knowledge extraction from the massive repository of stored echocardiograms, promising substantial clinical value by integrating relatively inexpensive quantitative indicators into everyday medical workflows and enabling causal understanding that relies on consistent, long-term patient follow-up [35]. The study is considered foundational for applying automated interpretation to monitor patients over time, though its short analysis window and potential biases limit its strength. It also omits information on the gender distribution of participants, which could influence the findings.

After imaging registration and correct segmentation, automated measurements can be made [36]. Guidelines from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging recommend averaging five consecutive cardiac cycles to calculate LVEF. In clinical practice, however, the process is often time-consuming, so a single representative beat is typically used to estimate LVEF [37]. Therefore, the use of AI may have a definite impact on time-saving when calculating LVEF and other essential measurements. Another important challenge that AI has the potential to address is inter- and intra-observer variability, which affects all imaging modalities. For instance, studies have shown that LVEF measurements can differ between readers by as much as 10%. Notably, a 10% decline in ejection fraction is the same threshold used to define clinically significant cardiotoxicity, which may necessitate interruption of chemotherapy. This degree of variability poses a considerable challenge in cardio-oncology, as small reductions in LVEF are often attributed to measurement noise rather than true cardiac injury, potentially delaying detection of cardiotoxicity. Automation offers a solution to these issues by standardizing measurements and reducing variability [38,39]. Nonetheless, the role of the specialist remains indispensable for interpreting AI-generated results, applying clinical context, and ensuring the accuracy and reliability of automated assessments.

It is important to note that transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has a more complex role than just appreciating GLS and LVEF, being an essential tool in cardio-oncology to assess ventricular, atrial, valvular, and pericardial structure and function in patients with current or past cancer [4,40].

In a large recent study, investigators assessed the use of AI for echocardiographic quantification. Using 877,983 measurements from 155,215 studies at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC), they developed EchoNet-Measurements, an open-source DL model for automated annotation of 9 B-mode and 9 Doppler parameters. The model showed high agreement with sonographer measurements on internal CSMC and external Stanford Health Care (SHC) datasets (mean coverage probability 0.796–0.839; mean relative difference 0.096–0.120), with consistent performance across 2103 temporally distinct studies and various patient subgroups. These findings highlight AI’s potential to improve efficiency, accuracy, and workflow in cardiovascular imaging [41].

Another critical potential advantage and emerging role of AI in cardio-oncology lies in its potential to identify novel markers and predictive parameters of subclinical cardiotoxicity—well before traditional measures, such as LVEF and GLS, show any detectable changes [42,43].

A key application of AI in cardio-oncology imaging is automated LVEF measurement using AI-assisted point-of-care echocardiography, which can streamline workflow, enhance accuracy, and enable efficient real-time cardiac monitoring during oncology visits [33]. This approach enhances efficiency by eliminating the need for a cardiologist to be physically present at each visit, allowing reliable cardiac assessments to be performed seamlessly within oncology care settings. For example, recent studies have explored the use of AI-guided echocardiography performed by nurses with no prior ultrasound training. In one such study, each patient underwent paired limited echocardiograms—one acquired by a nurse guided by a DL algorithm and the other by an experienced sonographer without AI assistance. Five expert echocardiographers independently and blindly evaluated all studies. The results demonstrated that the DL algorithm enabled non-expert operators to obtain diagnostic-quality transthoracic echocardiograms suitable for assessing left and right ventricular size and function, as well as detecting nontrivial pericardial effusions [44].

One notable example of how AI may increase efficacy in cardio-oncology is the FAST-EFs multicenter study involving 255 patients, which demonstrated that automated LV measurements are feasible, rapid, and highly reproducible compared with traditional visual assessment and the manual Simpson’s biplane method. The average analysis time was only 8 ± 1 s per patient, with no inter- or intra-observer variability, highlighting the efficiency and reliability of AI-assisted echocardiographic analysis [33]. However, a limitation of the study lies in the relatively small cohort of patients.

GLS has been suggested as a more responsive indicator for the early identification of myocardial dysfunction before a measurable decline in LVEF occurs. However, some time ago, research by Farsalinos and colleagues highlighted considerable inconsistency across different echocardiography system manufacturers when assessing GLS [45]. To address this issue, Kwan and colleagues showed that an automated deep-learning strain (DLS) workflow can help harmonize measurements across different vendors, improving inter-vendor consistency irrespective of subjective image quality [46]. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that, in a controlled setting, GLS measurements obtained from contemporary semi-automated clinical software are more consistent than they were a decade ago. Mid- and full-wall strain analyses were available in all but one software package. Endocardial as well as mid- and full-wall GLS measurements showed minimal inter-vendor variability, with an average maximum bias of only 0.6% strain units [47].

In a study by Kuwahara et al., a model utilizing a dedicated software application for echocardiographic analysis was used to evaluate left ventricular function in patients undergoing chemotherapy. The primary parameter analyzed was GLS, with additional assessment of LVEF, left ventricular dimensions, mass index, left atrial volume index, and diastolic function parameters such as septal and lateral e′ velocities. The AI-assisted model achieved an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.64–0.90) between novice and experienced clinicians, compared to 0.62 (95% CI: 0.34–0.80) with conventional methods. These results highlight the ability of AI-derived tools to provide more consistent and reliable evaluations across clinicians with varying experience levels, reducing variability in the assessment of cardiac function and enhancing reproducibility of advanced echocardiographic measurements in the cardio-oncology setting [48].

In another study of 152 patients with HER2-positive breast cancer treated with anti-HER2 therapy and anthracyclines, AI-assisted analysis was used to obtain automated ejection fraction and GLS. These AI-derived values showed strong concordance with those obtained using standard software, with a median standard deviation of strain values of only 1.2% during serial echocardiographic monitoring, underscoring the accuracy and reliability of AI-based measurements [49].

Moreover, recently, Salte et al. evaluated another AI method for fully automated AI-based measurement of LV GLS in echocardiography. The AI successfully identified all three standard apical views and performed cardiac event timing in 89% of patients. It also automated segmentation, motion estimation, and GLS measurement across diverse cardiac pathologies and LV function ranges. GLS measured by AI was −12.0 ± 4.1% versus −13.5 ± 5.3% by the reference method, with a bias of −1.4 ± 0.3% (95% limits of agreement: 2.3 to −5.1), comparable to intervendor variability. The fully automated analysis eliminated measurement variability and was completed within 15 s [50]. AI-enabled, standardized GLS measurements across vendors could facilitate the detection of subtle, early signs of cancer therapy–related cardiotoxicity that may not yet produce measurable changes in LVEF.

A notable example of DL in echocardiography is EchoNet, a model trained on over 2.6 million echocardiogram images from 2850 patients. EchoNet demonstrated the ability to identify cardiac structures, assess function, and even predict systemic risk factors such as age and weight. The model accurately detected the presence of pacemaker leads (AUC = 0.89), left atrial enlargement (AUC = 0.86), and left ventricular hypertrophy (AUC = 0.75). It also provided reliable estimates of left ventricular end-systolic and diastolic volumes (R2 = 0.74 and 0.70, respectively) and ejection fraction (R2 = 0.50), while predicting age (R2 = 0.46), sex (AUC = 0.88), weight (R2 = 0.56), and height (R2 = 0.33). Interpretability analyses confirmed that EchoNet appropriately focused on key cardiac structures during explainable diagnostic tasks and highlighted novel regions of interest when predicting complex systemic phenotypes—suggesting that such AI models may uncover new, clinically relevant imaging biomarkers beyond human perception [42].

Another study presented EchoNet-Dynamic, a video-based AI model that analyzes full echocardiogram videos across multiple cardiac cycles. The model was trained on 10,030 annotated echocardiogram videos and demonstrated the ability to segment the left ventricle (Dice Similarity Coefficient 0.92), estimate ejection fraction (mean absolute error 4.1%), and classify heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (AUC 0.97). In an external dataset, performance remained strong, with a mean absolute error of 6.0% for ejection fraction and an AUC of 0.96 for heart failure classification. Prospective evaluation indicated variability comparable to or lower than that of human experts. By incorporating information across multiple cardiac cycles, EchoNet-Dynamic can assess subtle changes in ejection fraction with high reproducibility. The study also released the largest publicly available annotated echocardiogram video dataset to facilitate further research in AI-assisted echocardiography [51].

Cai et al. developed MMnet, a hybrid DL and ML model designed to automate the grading of diastolic function using echocardiographic data. The model analyzes key parameters, including mitral E and A wave velocities, septal and lateral e’ velocities, tricuspid regurgitation velocity, LVEF, and left atrial end-systolic volume, extracted from 2D grey-scale, pulse-wave, and tissue Doppler images. By integrating these features, MMnet delivers accurate and efficient diastolic function grading, demonstrating the potential of AI to enhance echocardiographic diagnostics with high precision and strong clinical applicability [52].

In a longitudinal prospective cohort study of 248 breast cancer patients receiving 240 mg/m2 of doxorubicin, supervised machine learning algorithms were applied to identify echocardiographic strain patterns most strongly associated with subsequent cardiotoxicity. Participants underwent 2D echocardiography at baseline, 4 months, and annually thereafter, with strain and strain rate analyses performed using TomTec Cardiac Performance Analysis software. The application of ML enabled the discovery of specific strain-based features predictive of cardiotoxicity, offering a promising approach for early detection of subclinical cardiac dysfunction in patients undergoing anthracycline therapy [53].

Chang et al. developed an AI-based predictive model using clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic data from patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, preparing for anthracycline therapy (2014–2018). The model incorporated 15 variables spanning clinical characteristics, chemotherapy regimens, and echocardiographic measurements, with the most influential predictors being trastuzumab use, hypertension, and cumulative anthracycline dose. The algorithm analyzed patterns in these data to identify patients at higher risk of CTRCD and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. The study found that the model performed well in risk stratification, highlighting its potential to support early identification and management of patients susceptible to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity [54].

In a longitudinal retrospective study of 4309 cancer patients, echocardiographic data effectively predicted cardiac dysfunction, whereas laboratory data added little additional predictive value [55]. Echocardiographic data alone achieved an AUC of 0.85, compared with 0.74 for laboratory data alone. The combined model incorporating both data types performed best, with an AUC of 0.91 for diagnosing cardiac dysfunction [55]. The authors planned for the algorithm to be made available in an online risk stratification tool.

In a recent follow-up study, the research group applied ML to large-scale institutional electronic medical records to predict adverse cardiac outcomes in cancer survivors. They identified four clinically significant subgroups with distinct incidences of cardiac events and mortality, demonstrating that machine learning algorithms analyzing patient similarities over time can help identify survivors at increased risk of cardiac dysfunction [56].

Another promising application involves AI-driven re-analysis of stored imaging data within Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS). Advances in AI image interpretation now allow automated review of previously acquired studies, improving diagnostic consistency and accuracy while reducing inter- and intra-observer variability [57].

Several vendors now provide AI-assisted tools for measuring LVEF. Evidence from a randomized clinical trial suggests that AI-based LVEF assessment may improve accuracy, efficiency, and reproducibility compared with conventional echocardiographic interpretation. Such tools have the potential to streamline clinical workflows, reduce inter-observer variability, and facilitate earlier detection of subclinical cardiac dysfunction [58].

Table 1.

Key studies of AI applied to echocardiography.

Table 1.

Key studies of AI applied to echocardiography.

| Study | Task | AI Method | Cohort | Validation | Performance | Explainability | Main Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knackstedt et al. [33] | Automated LVEF & GLS | ML/DL | 255 patients, multicenter | Internal | ICC > 0.9, time 8 ± 1 s | No | Fast, reproducible EF/GLS |

| Zhang et al. [35] | Full echo interpretation | CNN | ~2850 patients | Internal | EF R2 ≈ 0.50, volume R2 ≈ 0.70 | Partial | Foundational automated echo |

| Sahashi et al. [41] | 18 echo parameters | DL | 155,215 studies | External | Mean rel. diff 0.096–0.120 | No | Large-scale automation |

| Salte et al. [50] | Automated GLS | DL | ~200 patients | Internal | Bias −1.4 ± 0.3%, LoA −5.1 to 2.3 | No | Eliminates variability |

| Kuwahara et al. [48] | GLS in chemo pts | DL | 243 patients | Internal | ICC 0.81 vs. 0.62 manual | No | Improves reproducibility |

| Ouyang et al. [51] | Beat-to-beat EF | DL video | 10,030 videos | External | MAE 4.1–6.0%, AUC 0.96 | Partial | Video-based EF |

| Ghorbani et al. [42] | Structure + phenotype | DL | 2.6 M images | Internal | Pacemaker AUC 0.89, LAE AUC 0.86 | Yes | Shows biological attention |

| Cai et al. [52] | Diastolic grading | DL + ML | ~1000 patients | Internal | Accuracy ~90% (reported) | No | Automated grading |

| Narang et al. [44] | AI-guided acquisition | DL | 240 patients | External | Diagnostic quality in >90% | No | Enables non-experts |

| He et al. [58] | AI vs sonographers | DL | 3769 studies | Prospective | Lower variability vs. humans | No | Workflow improvement |

| Cheng et al. [53] | Strain → CTRCD | ML | 248 patients | Internal | AUC ~0.80 | Partial | Early risk detection |

| Chang et al. [54] | CTRCD risk | ML | NA | Internal | AUC ~0.85 | Partial | Multivariable risk |

| Zhou et al. [55] | CTRCD prediction | ML | 4309 patients | Internal | AUC 0.91 (combined model) | No | Echo dominates prediction |

| Hou et al. [56] | Survivor phenotypes | ML | 4632 patients | Internal | Distinct event curves | No | Risk stratification |

AI = artificial intelligence; AUC = area under the curve; CNN = convolutional neural network; CTRCD = cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction; DL = deep learning; EF = ejection fraction; GLS = global longitudinal strain; HF = heart failure; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; LAE = left atrial enlargement; LoA = limits of agreement; LV = left ventricle; LVSD = left ventricular systolic dysfunction; MAE = mean absolute error; ML = machine learning; NA = not available; NPV = negative predictive value; R2 = coefficient of determination; ROC = receiver operating characteristic.

5.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

CMR is widely recognized as the gold standard for assessing ejection fraction and providing non-invasive tissue characterization, offering critical information to guide treatment decisions, particularly in patients receiving potentially cardiotoxic cancer therapy [59]. CMR can also give information/hints about the underlying mechanisms of cardiotoxicity.

A valuable study showed that DL-based fully automated analysis of left ventricular volumes and function is feasible, extremely fast and shows respectable performance without any manual corrections. Even with manual corrections—which are required for precise results in most patients—this approach remains time-efficient compared to manual analysis [60].

Fully automated cardiac localization and image plane acquisition are now commercially available, significantly reducing scan and analysis time while accurately detecting artifacts and enabling corrective actions or repeat acquisitions. AI-driven methods in parallel and real-time imaging, as well as compressed sensing, support faster image capture without loss of diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, the use of AI in CMR tissue characterization—including radiomics and texture analysis—has enhanced the assessment of scar imaging, wall thickening, and inflammation [61].

A neural network has been developed to reconstruct cMRF T1 and T2 maps directly from undersampled spiral images in under 400 ms. The method is robust to varying cardiac rhythms, enabling rapid, real-time display of cMRF maps [62].

Edalati et al. evaluated two AI-based DL approaches for automated slice alignment (EasyScan) and cardiac shimming (AI shim) in cardiac MRI. The models were trained and validated on datasets from over 500 subjects. In subsequent prospective studies, AI-guided slice planning reduced operator dependence and shortened scan times by approximately 2 min (∼13% faster) compared to manual planning, while improving plane accuracy. AI shim enhanced B0 magnetic field homogeneity compared with conventional volume shimming. Overall, these AI tools demonstrated more efficient, standardized, and higher-quality cardiac MRI acquisition [63]. Despite not being built on dedicated oncologic patient populations, these studies underscore how their methodologies and insights could be meaningfully adapted to advance cardio-oncology practice.

The activity of some ICI displays cross-reactivity with cardiac proteins such as titin, which can determine myocarditis [64]. Of note, myocardial changes associated with ICI therapy are frequently initially subclinical and asymptomatic, which makes establishing a definitive diagnosis challenging. In addition, it may be difficult to ascertain whether early cardiotoxic changes reflect new toxicity or pre-existing myocardial damage [65]. Therefore, it is essential to use the most sensible methods in uncovering these subtle changes. CMR is most specific for tracking myocardial changes during or after myocarditis [66]. In some studies, artificial intelligence has been employed to detect early imaging changes suggestive of subclinical myocarditis. In one such study, early gadolinium enhancement (EGE) was assessed alongside left ventricular functional parameters using AI-based algorithms applied to CMR images from patients with acute myocarditis, highlighting a significant role for EGE, according to the Lake Louise criteria, in the evaluation of patients with a clinical suspicion of acute myocarditis [67].

Novel approaches, such as feature tracking, tagging and fast-strain-encoded CMR techniques are emerging means to assess myocardial strain using CMR [68].

Kar et al. investigated whether AI-derived GLS from left ventricular MRI could serve as an early, independent predictor of Cancer Therapy–Related Cardiac Dysfunction (CTRCD) in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Using DENSE MRI in 32 patients at baseline and 3- and 6-month follow-ups, two DeepLabV3+ fully convolutional networks automated LV segmentation and 3D strain computation. Cox proportional hazards models incorporating clinical and contractile factors demonstrated that GLS predicted CTRCD risk independently of LVEF. This AI-guided GLS approach may enable earlier identification of at-risk patients and guide cardioprotective strategies, though the study was limited by its single-center design and lack of external validation [69].

The StrainNet study investigated a convolutional neural network designed to perform myocardial strain analysis on cine CMR images from 161 healthy participants. The model demonstrated markedly improved accuracy in both global and segmental strain measurements compared with conventional post-processing techniques, highlighting its potential to enhance the precision and efficiency of CMR-based functional assessment [70].

Measurements of left atrial remodeling and vascular stiffness are increasingly accessible tools for assessing long-term cardiovascular risk following cancer therapy. For instance, in two studies of patients with hematologic malignancies treated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib, abnormal left atrial strain and size on echocardiography, as well as elevated native T1/T2 values on cardiac MRI, were strongly predictive of future major adverse cardiac events and other complications [71,72]. Using AI to automate the calculation of these parameters could greatly accelerate the process and warrants evaluation in future studies.

In radiotherapy, cardiac substructure dose metrics are more predictive of late cardiac complications than whole-heart measures. Magnetic resonance-guided radiation therapy (MRgRT) allows visualization of substructures during daily localization, offering opportunities for improved cardiac sparing. One study extended the nnU-Net deep learning framework with self-distillation (nnU-Net.wSD) for substructure segmentation in MRgRT. Across 12 substructures, the model achieved a mean Dice similarity coefficient of 0.65 ± 0.25, outperforming a standard 3D U-Net (0.583 ± 0.28; p < 0.01), with better performance when leveraging fractionated data. Predicted contours generated dose-volume histograms closely matching clinical plans, with mean and maximum dose deviations of 0.32 ± 0.5 Gy and 1.42 ± 2.6 Gy, respectively. Volumes were largely consistent across institutions, with minor variability in coronary arteries. These results represent an important advance toward rapid and reliable cardiac substructure segmentation to enhance cardiac sparing in low-field MRgRT [73].

Table 2.

Key studies of AI applied to cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 2.

Key studies of AI applied to cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

| Study | Task | AI Method | Cohort | Validation | Performance | Explainability | Main Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Böttcher et al. [60] | LV volumes & EF | DL | 50 patients | Internal | Dice ~0.94, small bias vs. manual | No | Fully automated LV |

| Hamilton et al. [62] | T1/T2 mapping | DL | Technical | Internal | Map error < 5% | No | Real-time mapping |

| Edalati et al. [63] | Planning & shimming | DL | >500 subjects | Prospective | ~13% scan time reduction | No | Faster acquisition |

| Yuan et al. [67] | Myocarditis detection | ML/DL | 21 patients | Internal | AUC ~0.90 (reported) | No | Detects EGE |

| Kar et al. [69] | GLS → CTRCD | DL | 32 patients | Internal | HR significant; GLS predictive | No | Early CTRCD signal |

| Wang et al. [70] | Myocardial strain | DL | 161 patients | Internal | Lower error vs. conventional | No | Better strain accuracy |

| Summerfield et al. [73] | MRgRT substructures | DL | 18 patients | Internal | Dice 0.65 ± 0.25 | No | Enables substructure sparing |

AI = artificial intelligence; AUC = area under the curve; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; CTRCD = cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction; DL = deep learning; DENSE = displacement encoding with stimulated echoes; EF = ejection fraction; EGE = early gadolinium enhancement; GAN = generative adversarial network; GLS = global longitudinal strain; LoA = limits of agreement; LV = left ventricle; MAE = mean absolute error; ML = machine learning; MRgRT = magnetic resonance-guided radiotherapy; R2 = coefficient of determination.

5.3. Computed Tomography

Cardiac CT enables promising AI applications, such as automated CAC scoring on ECG-gated non-contrast chest CT, with multiple validated methods demonstrating high accuracy [74].

Detailed plaque characterization and quantification using CT offer valuable insights into various stages of coronary artery disease (CAD) [75]. The same technology, combined with AI applications, may play a pivotal role in uncovering cancer-related complications, like accelerated CAD.

Staging CT scans have typically been considered inadequate for assessing CAD risk, largely because they are not cardiac-gated. However, recent work demonstrates that AI applied to non-gated CT imaging can reliably estimate CAC scores. This development suggests that CAD detection and risk stratification may be incorporated into routine oncologic imaging without the need for additional scans, radiation exposure, or cost [76]. Shen et al. found that automated CAC derived from pre-treatment chest CT helped identify diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients at higher risk for anthracycline-related cardiac dysfunction and MACE. However, the study was limited by a small sample size and inclusion of only Chinese patients, highlighting the need for broader validation [77].

On the other hand, deep learning-based calcium scoring methods classify individual voxels rather than candidate lesions. Because most voxels in CT images are background rather than CAC, Wolterink et al. proposed a two-stage approach using two convolutional neural networks: the first CNN identified candidate voxels in coronary CT angiography, and the second CNN further discriminated true CAC from other candidates [78].

An observational study of 315 non-contrast CT scans demonstrated that AI-based semi-automatic and automatic software produced Agatston, volume, and mass calcium scores, as well as the number of calcified lesions, with excellent correlation and agreement [79].

A recent study demonstrated that a DL–based algorithm for CAC scoring after chest radiotherapy could predict future acute coronary events (ACE). The study evaluated breast cancer patients who received adjuvant radiotherapy (n = 511) or did not (n = 600) between 2005 and 2013. CAC Agatston scores were analyzed using the AI algorithm, and the individual mean heart dose (MHD) was calculated, with no radiotherapy scored as 0 Gy. The primary endpoint was ACE following breast surgery. CAC scores were significant predictors of ACE, suggesting that AI-based CAC assessment on simulation CT could help identify high-risk patients, though further studies are needed to confirm these findings [80].

Interestingly, AI can generate a highly reliable and clinically useful cardiovascular disease risk profile from existing non-contrast chest CT scans in patients undergoing cancer treatment planning or follow-up. A DL model trained on 30,286 low-dose CT scans from the National Lung Cancer Trial successfully identified individuals at elevated risk of cardiovascular mortality (AUC 0.768), effectively transforming a lung cancer screening scan into a dual-purpose tool for cardiovascular risk assessment [81]. Larger studies evaluating the accuracy of AI-driven CAC and atherosclerotic disease assessment from already available CT scans in breast cancer patients are currently underway. The findings may also be applicable to individuals with other malignancies who undergo non-gated chest CT [7].

Coronary CTA radiomics identified invasive and radionuclide imaging markers of plaque vulnerability with good to excellent diagnostic accuracy, significantly outperforming conventional quantitative and qualitative high-risk plaque features. Coronary CTA radiomics may provide a more accurate tool to identify vulnerable plaques compared with conventional methods. Further larger population studies are warranted [82].

Gernaat et al. evaluated a CNN algorithm for the automated assessment of CAC and thoracic aorta calcification (TAC) in breast cancer patients undergoing CT scans for radiotherapy planning. The study reported high reliability of the CNN algorithm in quantifying both CAC and TAC, highlighting the potential of AI to facilitate cardiovascular risk assessment in oncology patients using imaging acquired for non-cardiac purposes [83].

Moreover, Gal et al. applied a DL algorithm for automatic quantification of CAC from CT scans in over 15,000 breast cancer patients scheduled for radiotherapy. The study demonstrated a strong correlation between the AI-derived CAC scores and cardiovascular risk, underscoring the potential of automated imaging analysis to enhance cardiovascular risk stratification in oncology populations [84].

Importantly, yet another emerging application of AI in cardio-oncology imaging lies in the optimisation of the detection of masses. AI can improve the evaluation of cardiac masses across detection, characterization, and monitoring. Because assessment of these masses relies on analyzing tumor size, shape, and textural patterns, AI’s ability to recognize complex—and sometimes imperceptible—image features is especially valuable. Through deep learning–based differentiation of healthy and cancerous tissue, AI can precisely measure tumor dimensions, define morphology, and accurately delineate mass margins, further expanding its role in cardio-oncology [85]. Additionally, algorithms can be incorporated, helping to determine the prognosis of the mass and to optimize its treatment [86]. Finally, AI can assist in monitoring treatment response by tracking changes in tumor size, texture, and the emergence of any new lesions [87].

Maffei et al. evaluated a radiomics-based AI classifier to assess the quality of automated segmentation of cardiac substructures for radiotherapy planning. Using 36 CT scans with 25 manually contoured substructures, radiomic features were extracted from both manual and automatic contours. A supervised-learning model was trained to distinguish correct from incorrect contours, achieving 82.6% accuracy and an AUC of 0.91. Key features showed strong correlation with standard quantitative metrics such as Dice index and Hausdorff distance. This approach demonstrates the potential for automated assessment of segmentation quality, which could support the expansion of autocontouring atlases and improve analysis of large radiotherapy datasets [88].

Another study developed and evaluated a DL approach for automatic segmentation of cardiac chambers, large arteries, and localization of the three main coronary arteries in CT scans used for radiation therapy planning. The method employed an ensemble of CNNs with two output branches, one for segmentation and one for coronary artery localization, trained on reference annotations and virtual noncontrast cardiac scans. Performance was assessed using Dice score (DSC) and average symmetric surface distance (ASSD), with 2D slice DSC ranging from 0.76 to 0.88 and ASSD from 0.17 to 0.27 cm, and 3D DSC from 0.87 to 0.93 and ASSD from 0.07 to 0.10 cm. Coronary artery localization achieved DSC values of 0.80 to 0.91. Predicted dosimetric parameters showed strong correlation with planned doses (R2 = 0.77–1.00 for chambers and large vessels; 0.76–0.95 for coronary arteries). The developed and evaluated method can automatically obtain accurate estimates of planned radiation dose and dosimetric parameters for the cardiac chambers, large arteries, and coronary arteries [89].

Lassen-Schmidt et al. evaluated an iterative training approach to improve AI-based segmentation of the heart and mediastinum using 132 thoracic CT scans annotated by 13 radiologists. In three training iterations, initial manual segmentations of 5–25 CTs were used to train a nnU-Net, with subsequent iterations incorporating AI-generated pre-segmentations corrected by humans. Model performance improved consistently across iterations, achieving Dice similarity coefficients of 0.91 for the heart and 0.95 for the mediastinum. The approach reduced human annotation time by 50% for the heart and 70% for the mediastinum, and even a model trained on just five datasets achieved DCS above 0.90. This iterative workflow demonstrates an efficient method for developing accurate AI segmentation models while progressively minimizing human effort, with future work focusing on optimizing initial dataset size and pre-processing strategies [90].

Jiad et al. implemented and evaluated an AI-based deformable image registration and organ segmentation method, termed AI dose mapping (AIDA), for estimating radiation dose to the esophagus and heart. The workflow required approximately 2 min per patient. Segmentations achieved mean Dice similarity coefficients of 0.80 ± 0.15 for the esophagus and 0.94 ± 0.05 for the heart, with Hausdorff distances at the 95th percentile of 3.9 ± 3.4 mm and 14.1 ± 8.3 mm, respectively. AIDA-derived heart doses were significantly lower than planned doses (p = 0.04), and larger dose deviations (≥1 Gy) occurred more frequently with AIDA (N = 26) than with manual dose accumulation (N = 6). The study demonstrates that rapid estimation of radiation dose to thoracic tissues using AIDA is feasible, with metrics and segmentations comparable to manual approaches, supporting its potential application in radiotherapy planning [91].

More recently, Borges et al. evaluated radiation dose distribution in auto-segmented cardiac substructures for left breast radiotherapy, emphasizing the importance of minimizing cardiac exposure as highlighted in the RTOG 1005 protocol. Anatomical structures were segmented using TotalSegmentator and Limbus AI, and the relationship between the cardiac area and other organs at risk was analyzed using log-linear regressions. The study found that dose-volume assessment protocols often overlook cardiac substructures, but automated tools can address these limitations. The authors correlated doses in the overall cardiac region with specific substructures, proposed planning limits, and suggested that statistical models could estimate doses for substructures lacking segmentation tools. Their findings also support the use of absolute dose-volume thresholds for future cause-effect evaluations [92].

Table 3.

Key studies of AI applied to CT and radiotherapy planning.

Table 3.

Key studies of AI applied to CT and radiotherapy planning.

| Study | Task | AI Method | Cohort | Validation | Performance | Explainability | Main Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shen et al. [77] | CAC → CTRCD | DL | 1468 patients | Multicenter | AUC ~0.75–0.80 | No | Risk stratification |

| Gernaat et al. [83] | CAC/TAC scoring | CNN | ~2300 patients | Internal | ICC > 0.90 | No | Opportunistic screening |

| Gal et al. [84] | CAC → CV risk | CNN | 15,915 patients | External | Strong HR gradients | No | Large-scale validation |

| Kim et al. [80] | CAC → ACE | DL | ~1100 patients | Internal | CAC significant predictor | No | Post-RT risk |

| Chao et al. [81] | CV mortality | DL | 30,286 patients | External | AUC 0.768 | No | Dual-use CT |

| Kolossváry et al. [82] | Plaque vulnerability | Radiomics | 25 patients | Internal | AUC 0.84–0.90 | Partial | Radiomics > standard |

| van Velzen et al. [89] | Dose mapping | DL | 18 patients | Internal | R2 0.77–1.00 | No | Accurate dosimetry |

| Maffei et al. [88] | Segmentation QC | ML | 36 scans | Internal | AUC 0.91 | Partial | Automated QC |

| Lassen-Schmidt et al. [90] | Heart segmentation | DL | 132 scans | External | Dice 0.91–0.95 | No | Robust segmentation |

| Jiang et al. [91] | Dose accumulation | DL | 72 patients | Internal | Dice heart 0.94 | No | Fast mapping |

ACE = acute coronary event; AI = artificial intelligence; ASSD = average symmetric surface distance; AUC = area under the curve; CAC = coronary artery calcium; CAD = coronary artery disease; CNN = convolutional neural network; CT = computed tomography; CTA = computed tomography angiography; DL = deep learning; DSC = Dice similarity coefficient; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; ML = machine learning; MHD = mean heart dose; QC = quality control; RT = radiotherapy; TAC = thoracic aorta calcification.

5.4. Nuclear Medicine Imaging

Automatic CAC scoring methods have also been validated in other CT scan types that routinely visualize the heart, including attenuation correction images from PET-CT [93] and CT images used in radiotherapy treatment planning [94]. These findings suggest that cardiac PET may detect radiation-induced coronary artery damage. Consequently, applying AI to already available cardiac PET imaging to assess myocardial perfusion in cardio-oncology patients represents a promising emerging direction. ML-based risk prediction applied to PET scans outperformed logistic regression in identifying patients at high risk for myocardial ischemia and/or major adverse cardiovascular events, compared with the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) risk model derived from European Society of Cardiology guidelines [95].

It was proposed that AI could be used to monitor changes in the distribution of tagged 18F-FDG over time. If these changes can be characterized and linked to specific chemotherapy regimens and cardiovascular outcomes, targeted preventive strategies could be developed to mitigate such effects in future patients [96].

AI frameworks—including convolutional neural networks, U-Nets, and generative adversarial networks—have exhibited substantial promise in refining and augmenting PET and SPECT image quality. Most AI-driven enhancement techniques employ deep-learning models that accept a compromised or degraded image as input and reconstruct a cleaner, more diagnostically valuable output. In denoising applications, the input is marred by pronounced noise, whereas in deblurring or super-resolution tasks, the image is limited by diminished spatial resolution. Collectively, these approaches strive to restore sharper, more interpretable images and thereby strengthen the diagnostic utility and overall workflow efficiency within nuclear medicine [97].

Fluorodeoxyglucose F-18 (18F-FDG) PET imaging is commonly employed to detect cardiovascular complications related to ICI, which can activate cytotoxic T cells, aggravate underlying atherosclerotic processes, and elevate the likelihood of major cardiovascular events. AI-based approaches can facilitate the tracking of temporal shifts in 18F-FDG distribution in cancer patients, offering a more nuanced and sensitive means of identifying and monitoring ICI-associated cardiotoxicity [98].

Table 4.

Key studies of AI applied to nuclear cardiac imaging.

Table 4.

Key studies of AI applied to nuclear cardiac imaging.

| Study | Task | AI Method | Cohort | Validation | Performance | Explainability | Main Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Išgum et al. [93] | CAC from PET-CT | ML | 133 patients | Internal | κ 0.85–0.89 | No | CV risk from PET-CT |

| van Velzen et al. [89] | CAC from PET-CT | ML/DL | 955 patients | External | High agreement vs. manual | No | Large-scale validation |

| Juarez-Orozco et al. [95] | Ischemia prediction | ML | 1234 patients | Clinical | Internal | AUC ~0.80 | Partial |

| Betancur et al. [96] | Obstructive CAD | DL | 1638 patients | External | AUC ~0.80–0.85 | No | Automated perfusion |

| Alves et al. [97] | Image quality | DL | 13,844 records | Internal | SNR ↑, RMSE ↓ | No | Better image quality |

| Calabretta et al. [98] | Vascular inflammation | ML/DL | 12 patients | Internal | Higher sensitivity vs. visual | No | Tracks ICI toxicity |

AI = artificial intelligence; AUC = area under the curve; CAD = coronary artery disease; CNN = convolutional neural network; DL = deep learning; FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose; ML = machine learning; MPI = myocardial perfusion imaging; PET = positron emission tomography; RMSE = root mean square error; SPECT = single-photon emission computed tomography; SNR = signal-to-noise ratio; ↑ = increase; ↓ = decrease.

6. AI Applied to Electrocardiography

Advances in computing power, machine learning techniques, and access to large-scale data may greatly enhance the clinical insights derived from the ECG while maintaining interpretability critical for medical decision-making in cardio-oncology [99]. Of note, ML algorithms demonstrate variability in sensitivity and specificity depending on the phenotype they target, with performance differing when identifying rarer, more severe cardiac conditions compared to more common, less severe ones [99].

In general, DL algorithms—especially those using CNN—demonstrated markedly better performance than rules-based methods and traditional ML approaches. These models show strong potential for analyzing resting ECG signals to detect structural heart disease, including left ventricular dysfunction. Such capabilities may support both population-level screening in asymptomatic individuals and earlier diagnosis in symptomatic patients, enhancing opportunities for timely intervention [99].

A landmark 2019 study from the Mayo Clinic trained a CNN using paired 12-lead ECG and echocardiogram data—LVEF as a measure of contractile function—from 44,959 patients to identify ventricular dysfunction defined as LVEF ≤ 35% using ECG data alone. When validated on an independent cohort of 52,870 patients, the model achieved an area under the curve of 0.93, with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 86.3%, 85.7%, and 85.7%, respectively. Among patients without ventricular dysfunction, those with a positive AI screen had a fourfold increased risk (hazard ratio 4.1; 95% CI, 3.3–5.0) of developing future ventricular dysfunction versus those with a negative screen. This study highlights how AI applied to the ECG—an inexpensive and widely accessible test—can provide a powerful screening tool to identify asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction [100,101,102,103].

In another study, AI-ECG-based predictions were combined with clinical risk factors, which further improved diagnostic accuracy (AUC 0.82), reinforcing the incremental value of ECG data in cardiovascular risk stratification. Among 14,613 participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, 803 (5.5%) developed heart failure within 10 years. The deep-learning model using only 12-lead ECG data achieved an AUC of 0.756 (95% CI 0.717–0.795). Traditional risk calculators (ARIC, Framingham) achieved AUCs of 0.802 and 0.780, respectively. The best performance (AUC 0.818, 95% CI 0.778–0.859) was obtained when the ECG–AI output was combined with age, gender, race, body mass index (BMI), smoking, coronary disease, diabetes, blood pressure and heart rate in a light gradient boosting machine model—where the ECG-AI output emerged as the most important individual predictor. Together, these findings show that integrating AI-derived ECG signals with established clinical risk factors not only increases predictive accuracy but may outperform some traditional risk models [104].

Another research team evaluated whether AI-ECG could be integrated into a clinical decision-support tool for the early detection of cardiac dysfunction. In the study, 120 primary care teams from 45 clinics were assigned to either an AI intervention arm (181 clinicians) or control (usual care, 177 clinicians). ECGs from 22,641 adults without prior heart failure were analyzed. The primary outcome was new diagnosis of low ejection fraction (EF ≤ 50%) within 90 days. The intervention increased low EF diagnosis (2.1% vs. 1.6%; OR 1.32, p = 0.007) overall and among those with positive AI-ECGs (19.5% vs. 14.5%; OR 1.43, p = 0.01). Echocardiogram use was similar overall but higher in AI-positive patients in the intervention group (49.6% vs. 38.1%; p < 0.001). Results demonstrate that AI-enabled ECG screening improves early detection of low EF in routine primary care [105,106]. Similar models may be developed for cardio-oncology purposes.

Recent studies have evaluated the usefulness of AI-ECG for predicting incident atrial fibrillation in more than 1900 participants, using the Cohorts for Aging and Research in Genomic Epidemiology–AF (CHARGE-AF) score as a comparator. In this analysis, both the AI-ECG model output and the CHARGE-AF score independently predicted future AF. These findings suggest that AI-ECG may provide a convenient method for risk assessment using a single ECG, without the need for manual or automated extraction of clinical data [107].

AI can also extract subtle patterns from ECG images to detect conditions such as anemia, which may help in identifying higher-risk patient cohorts [108].

Although the studies described above were not conducted specifically in patients with a history of cancer, their findings suggest potential applicability to cancer survivors. To date, no studies have evaluated the use of AI-ECG to predict atrial fibrillation or other arrhythmias in cancer patients or survivors. Nevertheless, atrial fibrillation is increasingly recognized as a cardiovascular complication of antineoplastic therapy, occurring, for example, during ibrutinib or following chest radiotherapy [109].

In a recent retrospective study involving 459 patients, AI-ECG proved to be a strong screening tool for evaluating the risk of LVSD in individuals treated with anthracyclines or trastuzumab. Using a multivariable Cox regression analysis, the study found that a positive AI-ECG result independently predicted the development of LVD at 5 years [HR: 2.12 (95% CI, 0.66–0.72); p < 0.0001] [110]. Of note, it was proven that the AI-ECG algorithms have good results in detection of low ejection fraction, irrespective of ethnic and racial subgroups [111].

Over time, several studies have examined whether specific ECG patterns can predict cardiotoxicity following cancer treatment. One early study from 2001 evaluated children who developed cardiac dysfunction after receiving anthracycline therapy (198–737 mg/m2 cumulative doxorubicin equivalents). The investigators observed that a reduction in QRS duration occurred more frequently in children with cardiomyopathy than in both anthracycline-naïve cancer patients and healthy controls [112].

In 2019, a study of 589 children treated with anthracyclines found that a 0.6 mV reduction in the sum of absolute QRS amplitudes in the six limb leads (ΣQRS) and a 10 ms increase in QTc were associated with a 17% (HR 1.174; p = 0.003) and 10% (HR 1.098; p < 0.006) higher risk of developing cardiomyopathy—defined as LVEF < 50%, fractional shortening < 26%, or LV end-diastolic diameter z-score > 2.5—compared to children who did not develop cardiomyopathy. These ECG changes were more pronounced in patients receiving higher anthracycline doses [113]. Beyond flagging individuals at elevated risk for atrial fibrillation, deep learning applied to ECG data can also help identify patients susceptible to drug-induced QT prolongation. This capability may enable earlier recognition of patients who require closer monitoring or tailored therapy, particularly in settings where QT-prolonging oncologic or supportive medications are routinely used [114].

Bos et al. reported that AI-ECG surpasses the standard corrected QT interval in identifying LQTS, even among individuals with ECG-concealed forms of the syndrome, offering reliable insights into their underlying genotypic status [115].

A relatively recent study demonstrated that AI trained on electrocardiograms from 1217 childhood cancer survivors—mostly with lymphoma/leukemia and 77% having received anthracycline therapy (median dose 169 mg/m2, range 35–734 mg/m2)—can predict late-onset cardiomyopathy. In a test group of 244 high-risk individuals, the model achieved a sensitivity of 76%, specificity of 79%, and an AUC of 0.87 (95% CI 0.83–0.90), using the 2014 American Society for Echocardiography guidelines for cardiomyopathy definition. Results demonstrate that AI-enabled ECG screening improves early detection of low EF in routine primary care [116].

Jacobs et al. evaluated a CNN–based AI-ECG model to detect LVSD in breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines, analyzing 1877 ECGs from 703 women with paired echocardiograms. The AI-ECG demonstrated strong diagnostic performance, achieving AUC values of 0.93 for LVEF < 50% and 0.94 for LVEF ≤ 35%, and showed excellent negative predictive value, making it particularly useful as an initial screening tool to determine which patients may require additional imaging. The model also tracked changes in cardiac function over time, suggesting usefulness for longitudinal monitoring. Importantly, the algorithm—originally developed in a general population—performed effectively in a cancer cohort, indicating good transportability [117].

Yagi et al. developed an AI-ECG model, “AI-CTRCD,” to predict chemotherapy-induced cardiac dysfunction in 1011 cancer patients receiving anthracyclines. About 8.7% developed cardiotoxicity, and a high AI-CTRCD score was associated with significantly increased risk (HR ~2.66), independent of clinical risk factors. The model improved predictive performance over conventional approaches, achieving a time-dependent AUC of 0.78 at 2 years, and consistently stratified risk across cancer types, sexes, baseline LVEF, and anthracycline doses, highlighting AI-ECG as a non-invasive tool for identifying patients at elevated cardiotoxicity risk [118].