Abstract

Background: Fibromyalgia (FM) is a condition characterised by chronic pain, which may or may not be associated with muscular stiffness. Sarcopenia is the progressive loss of muscle mass and strength. The loss of muscle mass is a key factor in the progression of both fibromyalgia and sarcopenia and therefore warrants thorough evaluation. It has been demonstrated that obesity directly influences factors that increase pain perception and disease severity and reduce quality of life. The primary objective of this study was to examine the association between fibromyalgia and the increased risk of developing sarcopenia. Methods: The sample consisted of 84 patients diagnosed with FM. We assessed sociodemographic characteristics, anthropometric variables (circumferential and ultrasound) pain with a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and algometry, risk of developing sarcopenia with SARC-F, quality of sleep, anxiety, and depression using validated questionnaires. Results: A total of 96.3% of the participants were women. Overall, 56.3% of the sample presented a high risk of sarcopenia according to SARC-F, VAS scores showed significant negative correlations with anxiety (p < 0.01) and with almost all algometric measures (p < 0.05). The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) demonstrated a positive and significant correlation with sleep quality (p < 0.01) and depression (p < 0.01). Furthermore, presence of a high risk of sarcopenia according to SARC-F was significantly associated with FIQ scores (p = 0.002) and depression (p < 0.001). Conclusions: There is a significant association between the impact of FM and a high risk of developing sarcopenia according to SARC-F. This population exhibits a high degree of pain, which are significantly associated with elevated levels of anxiety and depression.

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a condition characterised by chronic pain, which may or may not be associated with muscular stiffness, and is commonly accompanied by fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depression. Its aetiopathogenesis cannot be attributed to any specific cause [1]. Prevalence estimates are highly variable (0.4–11%), with a predominance of over 90% in females [2].

Because FM leads to fatigue and a reduction in quality of life, patients often adopt a sedentary lifestyle. One of the main consequences of this lack of physical activity is the loss of muscle mass and strength, corresponding to the definition of sarcopenia [3].

The prevalence of sarcopenia increases proportionally with age. According to various studies, it has been diagnosed in 9.9–40.4% of older adults living in the community [4,5], 2–34% of outpatients [6], and up to 56% of hospitalised patients [7]. These individuals experience greater difficulty in performing activities of daily living, an increased risk of falls and fractures [8], and longer hospital stays [9].

Patients diagnosed with FM often present with muscle weakness; however, this is not always associated with a loss of muscle mass [5]. Such weakness may be due to low levels of physical activity, which are directly related to the widespread pain characteristic of the condition [10].

Regarding body composition, it has been demonstrated that obesity directly influences factors that increase pain perception and disease severity and reduce quality of life [11]. Anthropometric measurements commonly assessed in studies involving FM include height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and circumferences of the waist, trochanter, and dominant thigh [12].

Another variable of importance in patients with FM or sarcopenia is the cross-sectional area (CSA) and thickness of the vastus lateralis of the quadriceps, as this muscle head has the greatest capacity for force generation [13]. These two variables are typically assessed via ultrasound. In a study conducted on older adults, the mean thickness of the vastus lateralis in healthy subjects was reported to be 1.9 cm [14].

The primary objective of this study was to examine the association between FM and the elevated risk of developing sarcopenia according to SARC-F. A secondary objective was to analyse the relationship between these conditions and various aspects of quality of life, as well as with body composition variables.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This was a descriptive observational study. The sample consisted of 84 volunteer patients diagnosed with FM who were members of the AFINSYFACRO Association in Móstoles, Spain, and had received a medical diagnosis of FM from qualified healthcare professionals. Both men and women aged between 18 and 75 years were eligible.

The sample size was calculated using QuestionPro, applying a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error.

Inclusion criteria were (I) confirmed diagnosis of FM; (II) age between 18 and 75 years; (III) voluntary participation with signed informed consent; (IV) no recent surgeries; and (V) adequate cognitive capacity to complete the questionnaires administered during the study.

2.2. Variables

Sociodemographic characteristics include age, BMI, marital status, employment status, and presence of comorbidities.

Pain was assessed using the VAS, a validated 0–10 scale for FM patients that measures pain intensity, where 0 represents no pain, and 10 indicates the worst imaginable pain. Test–retest reliability has been shown to be high, particularly among literate patients (r = 0.94; p < 0.001) [15].

2.3. Anthropometric and Clinical Measurements

Algometry: Pressure pain thresholds were measured using a Fischer analogue algometer (FNP100) at tender points located on the upper limbs (right and left epicondyles) and lower limbs (greater trochanter and medial knee bilaterally) [16].

Circumference measurements: Waist, trochanter, and dominant thigh circumferences were measured using a flexible tape measure.

Muscle architecture measurements: To take the measurements, patients were placed in a supine position with their limbs relaxed and in anatomical position. The anatomical point for measuring muscle architecture variables related to VL was 50% of the distance from the greater trochanter to the knee joint line. The points were marked with a marker pen for probe placement with a neutral inclination and perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the limb. Conductive gel was applied prior to probe contact. Three images were taken of each measurement, and the mean value of these was used for analysis [17,18,19].

2.4. Questionnaires

Sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which evaluates both qualitative and quantitative aspects of sleep. The questionnaire comprises 24 items (19 self-rated and 5 rated by a bed partner or roommate, if applicable). It yields seven component scores—subjective sleep quality, latency, duration, habitual efficiency, disturbances, use of hypnotics, and daytime dysfunction—each scored from 0 to 3, where 0 indicates no difficulty and 3 indicates severe difficulty. The global score (0–21) classifies respondents as good sleepers (≤5) or poor sleepers (>5) [20].

Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) Fibroi is a multidimensional instrument assessing functional capacity and quality of life in FM patients, using the validated Spanish version. Scores between 0 and <39 indicate that the impact is slight, between 39 and <59 moderate, and ≥59 severe [21,22,23].

Risk of developing sarcopenia: We used SARC-F which is a self-administered questionnaire that includes five items assessing strength, walking ability, stair climbing, chair rise, and history of falls, with scores from 0 to 10. A score ≥ 4 is predictive of sarcopenia [24,25].

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) consists of 14 items divided into two subscales—HADS-A (anxiety) and HADS-D (depression)—each containing seven items. Scores are classified as normal (0–7), borderline (8–10), or clinical case (11–21) [26].

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study complies with Spanish Organic Law 7/2021, of 26 May, concerning the protection of personal data for the purposes of prevention, detection, investigation, and prosecution of criminal offences. The research adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2014) regarding medical research involving human subjects.

All participants were informed of their rights to privacy and confidentiality. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and is held by the corresponding author.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Spain) (approval code: 24/745-EC_X) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT06253273).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS Statistics, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as percentages, while quantitative variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (X ± SD) or median and range, as required.

The normality of quantitative variables was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Correlations were explored using Spearman’s rho for non-parametric variables and Pearson’s correlation coefficient for parametric variables.

To compare the values of quantitative variables between the categories of qualitative variables, we used either Student’s t or analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Mann–Whitney’s U or Kruskal–Wallis tests according to normality. Associations between qualitative variables were examined using the chi-squared test.

To test whether the associations found in the univariate analysis were independent and to measure their impact, we performed a logistic regression model. As usual, p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

A total of 96.3% of the participants were women, with a mean age of 54.06 ± 9.67 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 31.06 ± 3.50 kg/m2. Overall, 56.3% of the sample presented a high risk of developing sarcopenia according to SARC-F.

The results indicate a high prevalence of symptoms related to FM, such as pain, sleep quality, anxiety, and depression. The scores obtained from the scales assessing these parameters are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and descriptive variables of the participants.

Table 2 summarises the mean and standard deviation values for algometry, circumferential measurements, and ultrasound variables obtained from the participants.

Table 2.

Values of algometry, circumferential, and ultrasound.

As shown in Table 3, a positive and significant correlation was observed between BMI and thigh circumference (ThCirc) (r = 0.599; p < 0.01), indicating that a higher BMI is associated with greater limb girth. Conversely, VAS scores showed significant negative correlations with anxiety (r = −0.458; p < 0.01) and with nearly all algometric measures (p < 0.05–0.01). This suggests that higher pain perception is associated with lower pressure pain thresholds and greater emotional distress.

Table 3.

Correlation between BMI and VAS with anxiety, algometry, and circumferential.

As shown in Table 4, FIQ demonstrated a positive and significant correlation with sleep quality (PSQ)I (r = 0.362; p < 0.01) and depression (HADS-D) (r = 0.552; p < 0.01), indicating that poorer sleep and higher depressive symptoms are linked to a greater perceived disease impact.

Table 4.

Correlation between FIQ, sarcopenia risk, and variables related to age, sleep, depression, circumference, and ultrasound measurements.

Furthermore, the presence of a high risk for developing sarcopenia according to SARC-F was significantly associated with FIQ scores (p = 0.002), depression (p < 0.001), and body circumference measurements (waist: p = 0.025; thigh: p = 0.047).

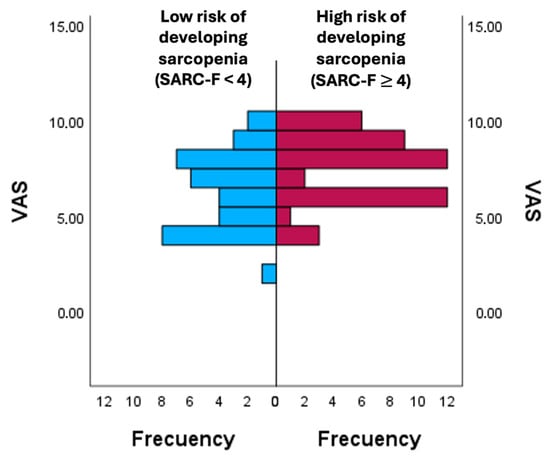

Figure 1 shows the comparison of pain scores (VAS) between groups stratified according to sarcopenia, the risk of developing sarcopenia according SARC-F. The analysis revealed differences in mean ranks (group with a score < 4 on the SARC-F: 32.86 ± 6.52; group with a score ≥ 4 on the SARC-F: 46.37 ± 7.27), showing higher VAS values in the high-risk group.

Figure 1.

Comparison of pain perception according to the risk of developing sarcopenia. VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

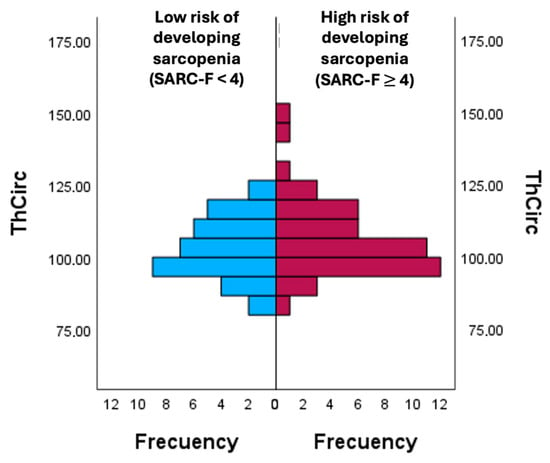

In Figure 2, thigh circumference (ThCirc) was compared between participants with the risk of patients developing sarcopenia according to the SARC-F. The group with a score ≥ 4 points on the SARC-F showed a higher mean ThCirc (106.89 ± 13.63) compared to the group with a score < 4 points on the SARC-F (103.06 ± 8.75), reflecting greater ThCirc values among individuals at the higher risk of developing sarcopenia according to the SARC-F.

Figure 2.

Comparison of ThCirc according to the risk of developing sarcopenia. ThCirc: Trochanter circumference.

To show whether the observed effects were independent, we adjusted a logistic regression model for women, as the number of men in our series was too small to allow modelling. The R2 value for the model was 0.51. Results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Logistic regression model.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between FM and the risk of developing sarcopenia, as screened by the SARC-F questionnaire, and to examine its associations with pain perception, psychological status, and body composition. Our findings provide evidence supporting an association between FM and a higher risk of developing sarcopenia according to SARC-F, and they are consistent with the notion of a vicious cycle in which chronic pain, reduced physical capacity, and psychosocial burden reinforce each other.

Participants obtained an average score on the FIQ of 65.28 ± 16.08, and 56.3% of the sample presented SARC-F scores ≥ 4. This prevalence is higher than that reported in community-dwelling adults without chronic pain syndromes, suggesting that individuals with FM are more vulnerable to a higher risk of developing sarcopenia [27]. Similar studies have previously reported significant reductions in muscle strength and functional performance in FM patients, contributing to lower health-related quality of life and greater perceived disability [28,29]. The significant correlation observed between the FIQ scores and sarcopenia risk (p = 0.002) indicates that the functional and psychosocial burden of FM may be partly mediated by muscle deterioration.

The strong association found between pain intensity and anxiety (r = −0.485; p < 0.01) aligns with the well-established interplay between chronic pain, emotional distress, and pain pathways [30]. Evidence suggests that decreased muscle mass and strength are independently associated with higher pain intensity and reduced muscle mass and strength [31]. Moreover, psychological distress can exacerbate muscle catabolism, reinforcing the vicious cycle of pain, weakness, and fatigue.

We observed a reduction in pressure pain thresholds among participants with a high risk of developing sarcopenia, as SARC-F supports the hypothesis that impaired muscle integrity contributes to heightened pain sensitivity. In addition, the current study also confirmed a high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms, consistent with previous reports describing frequent mood disturbances among FM patients and those with sarcopenia [32,33].

Although ultrasound was employed to assess the thickness and CSA of the vastus lateralis—both recognised indicators of muscle mass and quality [34,35,36]—no statistically significant correlation was detected with risk of developing sarcopenia according to SARC-F. This may be attributed to the multifactorial nature of sarcopenia in FM, in which functional impairments can occur even in the absence of measurable muscle atrophy. Inactivity, neuromuscular inefficiency, and altered proprioceptive feedback have all been implicated in the deterioration of motor function in FM, potentially masking the relationship between muscle architecture and clinical risk scores. A study evaluated VL thickness to identify low muscle mass and determined cut-off points of 1.7 cm for men and 1.5 cm for women [37]. Considering that our sample consisted mainly of women and that the average VL thickness was 1.65 cm, this indicates that there was no low muscle mass in these subjects. Anthropometric analyses revealed that waist and thigh circumferences were significantly associated with sarcopenia risk according to SARC-F (p = 0.025 and p = 0.047, respectively). This finding is consistent with prior research linking central adiposity and unfavourable fat distribution to impaired muscle performance in FM [38,39]. The coexistence of sarcopenic obesity—a phenotype characterised by low muscle mass and high fat accumulation—has been increasingly recognised in FM populations and may exacerbate pain perception, systemic inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction [40,41]. Therefore, the evaluation of body composition parameters should be systematically incorporated into FM management to identify high-risk individuals and guide targeted interventions [42].

Taken together, these multivariate findings complement the bivariate associations previously described, reinforcing the multidimensional nature of risk of developing sarcopenia in fibromyalgia and providing a framework for interpreting the clinical and pathophysiological implications discussed below. To determine the independence of the observed effects, a logistic regression model was fitted for women, given the limited number of men in the sample. The model demonstrated a good fit (R2 = 0.51), indicating that the included variables explained more than half of the variability in sarcopenia risk. Among the variables that remained significantly associated were trochanteric algometry (ALGTI and ALGRI) and hormonal status, suggesting that pain sensitivity and hormonal conditions independently contribute to sarcopenia risk prediction. Specifically, lower pressure pain thresholds at trochanteric points were associated with a higher likelihood of sarcopenia, while certain occupational conditions and menopausal status exerted relevant effects within the model. These findings are consistent with previous evidence linking chronic pain and reduced muscle function to neuroendocrine dysregulation and psychosocial stressors in fibromyalgia populations [20,27]. The interplay between hormonal changes, physical inactivity, and heightened pain sensitivity may accelerate muscle deterioration, reinforcing the concept of sarcopenia as a multifactorial condition in fibromyalgia. Clinically, these results underscore the need for comprehensive screening strategies that integrate musculoskeletal assessment with psychosocial and hormonal profiling. Multimodal interventions combining resistance and aerobic exercise, nutritional optimisation, and psychological support have demonstrated efficacy in improving muscle strength, reducing pain sensitivity, and enhancing quality of life in this population [29,30].

The limitations inherent to this study include the omission of the variable of regular physical exercise from the analysis. Neither was it considered whether the patients were taking any pharmacological treatments that could have influenced their physical condition. Furthermore, the sample size was relatively small and exclusively consisted of women, recruitment was limited to one association, and this is a condition that predominantly affects females.

Future longitudinal studies employing objective imaging and biochemical markers are warranted to clarify causal pathways and evaluate the efficacy of multimodal interventions in mitigating sarcopenic progression in FM. Furthermore, a control group of individuals with chronic pain but without FM, or who are healthy, should be included. Understanding these interactions is essential for designing personalised therapeutic strategies aimed at improving functional capacity, psychological well-being, and overall quality of life in affected individuals.

5. Conclusions

This study provides evidence of a significant correlation between the impact of FM and an increased risk of developing sarcopenia according to SARC-F. Participants showed high levels of pain, anxiety, and depression along with elevated BMI and circumference measurements, suggesting the coexistence of muscle dysfunction and metabolic imbalance in this population.

The interplay between chronic pain, physical inactivity, and emotional distress appears to promote muscle loss and reduced functional capacity, reinforcing the need to approach FM as a systemic and multidimensional condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.P.H.-P. and E.Ú.-D.; methodology, E.Ú.-D. and B.P.-R.; software, M.J.F.-A.; validation, J.P.H.-P.; formal analysis, C.O.-M. and M.J.F.-A.; investigation, E.C.F.-P., C.O.-M., N.M.-G., H.H. and J.P.H.-P.; resources, E.C.F.-P., H.H., J.H.-L. and N.M.-G.; data curation, E.Ú.-D. and M.J.F.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P.-R. and E.Ú.-D.; writing—review and editing, E.C.F.-P., J.P.H.-P., N.M.-G. and C.O.-M.; visualisation, B.P.-R. and J.H.-L.; supervision, E.Ú.-D.; project administration, E.Ú.-D.; funding acquisition, E.Ú.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the FIBYSAR project of Camilo Jose Cela University, grant number X Convocatoria de Investigación Interna.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain (approval number: 24/745-EC_X, data: 5 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data present in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank AFINSYFACRO for their participation in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CSA | Cross-Sectional Area |

| FIQ | Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire |

| FM | Fibromyalgia |

| GRTAlg/FLTAlg | Greater Left Trochanter Algometry/Greater Right Trochanter Algometry |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale |

| LEA/REA | Left Epicondyle Algometry/Right Epicondyle Algometry |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| RKAlg/LKAlg | Right Knee Algometry/Left Knee Algometry |

| TCirc | Tight Circumference |

| ThCirc | Trochanter Circumference |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| WCirc | Waist Circumference |

| GLTAlg | Greater Left Trochanter Algometry |

| RKAlg | Right Knee Algometry |

| LKAlg | Left Knee Algometry |

| VL | Vastus Lateralis |

References

- Felipe, D.; Rodríguez, G.; Mendoza, C.A. Fisiopatología de La Fibromialgia Physiopathology of Fibromyalgia. Reumatol. Clin. 2020, 16, 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, F.; Walitt, B.; Perrot, S.; Rasker, J.J.; Häuser, W. Fibromyalgia Diagnosis and Biased Assessment: Sex, Prevalence and Bias. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.R.; Lee, S.; Song, S.K. A Review of Sarcopenia Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Treatment and Future Direction. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2022, 37, e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makizako, H.; Nakai, Y.; Tomioka, K.; Taniguchi, Y. Prevalence of Sarcopenia Defined Using the Asia Working Group for Sarcopenia Criteria in Japanese Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. Res. 2019, 22, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, A.J.; Amog, K.; Phillips, S.; Parise, G.; McNicholas, P.D.; De Souza, R.J.; Thabane, L.; Raina, P. The Prevalence of Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults, an Exploration of Differences between Studies and within Definitions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnierse, E.M.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Leter, M.J.; Blauw, G.J.; Sipilä, S.; Sillanpää, E.; Narici, M.V.; Hogrel, J.Y.; Butler-Browne, G.; McPhee, J.S.; et al. The Impact of Different Diagnostic Criteria on the Prevalence of Sarcopenia in Healthy Elderly Participants and Geriatric Outpatients. Gerontology 2015, 61, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churilov, I.; Churilov, L.; MacIsaac, R.J.; Ekinci, E.I. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence of Sarcopenia in Post Acute Inpatient Rehabilitation. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Hayes, A.; Sanders, K.M.; Aitken, D.; Ebeling, P.R.; Jones, G. Operational Definitions of Sarcopenia and Their Associations with 5-Year Changes in Falls Risk in Community-Dwelling Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAndrade, J.; Pedersen, M.; Garcia, L.; Nau, P. Sarcopenia Is a Risk Factor for Complications and an Independent Predictor of Hospital Length of Stay in Trauma Patients. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 221, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeda, M.; Kim, Y.; Jaén, C.R.; Okifuji, A.; Corbin, L.W.; Maluf, K.S. Mediating Role of Physical Activity in the Relationship between Exercise-Induced Muscle Pain and Symptom Severity in Women with Fibromyalgia. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2024, 40, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakit, M.O.; Çakit, B.D.; Genç, H.; Pervane Vural, S.; Erdem, H.R.; Saraçoğlu, M.; Karagöz, A. The Association of Skinfold Anthropometric Measures, Body Composition and Disease Severity in Obese and Non-Obese Fibromyalgia Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Rheumatol. 2018, 33, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavilán-Carrera, B.; Acosta-Manzano, P.; Soriano-Maldonado, A.; Borges-Cosic, M.; Aparicio, V.A.; Delgado-Fernández, M.; Segura-Jiménez, V. Sedentary Time, Physical Activity, and Sleep Duration: Associations with Body Composition in Fibromyalgia. The al-Andalus Project. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ticinesi, A.; Narici, M.V.; Lauretani, F.; Nouvenne, A.; Colizzi, E.; Mantovani, M.; Corsonello, A.; Landi, F.; Meschi, T.; Maggio, M. Assessing Sarcopenia with Vastus Lateralis Muscle Ultrasound: An Operative Protocol. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ansary, D.; Marshall, C.J.; Farragher, J.; Annoni, R.; Schwank, A.; McFarlane, J.; Bryant, A.; Han, J.; Webster, M.; Zito, G.; et al. Architectural Anatomy of the Quadriceps and the Relationship with Muscle Strength: An Observational Study Utilising Real-Time Ultrasound in Healthy Adults. J. Anat. 2021, 239, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.P.; Assumpção, A.; Matsutani, L.A.; Bragança Pereira, C.A.; Lage, L. Pain in Fibromyalgia and Discriminativen Power of the Instruments: Visual Analog Scale. Dolorimetry and the McGill Pain Questionnaire. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2008, 33, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Úbeda-D’Ocasar, E.; Valera-Calero, J.A.; Hervás-Pérez, J.P.; Caballero-Corella, M.; Ojedo-Martín, C.; Gallego-Sendarrubias, G.M. Pain Intensity and Sensory Perception of Tender Points in Female with Fibromyalgia: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazevich, A.J.; Gill, N.D.; Zhou, S. Intra- and Intermuscular Variation in Human Quadriceps Femoris Architecture Assessed in Vivo. J. Anat. 2006, 209, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagae, M.; Umegaki, H.; Yoshiko, A.; Fujita, K. Muscle Ultrasound and Its Application to Point-of-Care Ultrasonography: A Narrative Review. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Calero, J.A.; Laguna-Rastrojo, L.; De-Jesús-Franco, F.; Cimadevilla-Fernández-Pola, E.; Cleland, J.A.; Fernández-De-las-Peñas, C.; Arias-Buría, J.L. Prediction Model of Soleus Muscle Depth Based on Anthropometric Features: Potential Applications for Dry Needling. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larche, C.L.; Plante, I.; Roy, M.; Ingelmo, P.M.; Ferland, C.E. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: Reliability, Factor Structure, and Related Clinical Factors among Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults with Chronic Pain. Sleep Disord. 2021, 2021, 5546484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauffin, J.; Hankama, T.; Kautiainen, H.; Arkela-Kautiainen, M.; Hannonen, P.; Haanpää, M. Validation of a Finnish Version of the Fibromyalgia Impact (Finn-FIQ). Scand. J. Pain 2017, 3, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ): A Review of Its Development, Current Version, Operating Characteristics and Uses. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2005, 23, S154. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Redondo, J.; González Hernández, T. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire: A Validated Spanish Version to Assess the Health Status in Women with Fibromyalgia. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2004, 22, 554–560. [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Morley, J.E. SARC-F: A Symptom Score to Predict Persons with Sarcopenia at Risk for Poor Functional Outcomes. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.W.; Chou, M.Y.; Iijima, K.; Jang, H.C.; Kang, L.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 300–307.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, M.; Sugden, N.; Thomas, M.; McGrath, A.; Skilbeck, C. The Structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: Theoretical and Methodological Considerations. Br. J. Psychol. 2023, 114, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valença, M.M.; Medeiros, F.L.; Martins, H.A.; Massaud, R.M.; Peres, M.F.P. Neuroendocrine Dysfunction in Fibromyalgia and Migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2009, 13, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, C.M.; Ingles, M.; Cominetti, M.R.; Viña, J. Free Radical Biology and Medicine Sarcopenia, Frailty and Their Prevention by Exercise. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 132, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, B.R.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.J. Associations Between Obesity with Low Muscle Mass and Physical Function in Patients with End-Stage Knee Osteoarthritis. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2021, 12, 21514593211020700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffal, S.M. Neuroplasticity in Chronic Pain: Insights into Diagnosis and Treatment. Korean J. Pain 2025, 38, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Vega, E.; Ruiz-Muñoz, M.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.; Romero-Galisteo, R.P.; González-Sánchez, M. Individuals with Fibromyalgia Have a Different Gait Pattern and a Reduced Walk Functional Capacity: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, J.; El Assar, M.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Physical Activity and Exercise: Strategies to Manage Frailty. Redox Biol. 2020, 35, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W.; Wolfe, F.; Tölle, T.; Üçeyler, N.; Sommer, C. The Role of Antidepressants in the Management of Fibromyalgia Syndrome. CNS Drugs 2012, 26, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European Consensus on Definition and Diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Calero, J.A.; Ojedo-Martín, C.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Cleland, J.A.; Arias-Buría, J.L.; Hervás-Pérez, J.P. Reliability and Validity of Panoramic Ultrasound Imaging for Evaluating Muscular Quality and Morphology: A Systematic Review. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2021, 47, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, D.; Rodrigues, R.; Geremia, J.M.; Brenol, C.V.; Vaz, M.A.; Xavier, R.M. Quadriceps Muscle Properties in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Insights about Muscle Morphology, Activation and Functional Capacity. Adv. Rheumatol. 2020, 60, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minetto, M.A.; Caresio, C.; Menapace, T.; Hajdarevic, A.; Marchini, A.; Molinari, F.; Maffiuletti, N.A. Ultrasound-Based Detection of Low Muscle Mass for Diagnosis of Sarcopenia in Older Adults. Pm R 2016, 8, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, L.P.; Santo, R.C.D.E.; Pena, É.; Dória, L.D.; Hax, V.; Brenol, C.V.; Monticielo, O.A.; Chakr, R.M.D.S.; Xavier, R.M. Morphological Parameters in Quadriceps Muscle Were Associated with Clinical Features and Muscle Strength of Women with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri, B.; Edman, E.; Löf, M.; Lund, E.; Leinhard, O.D.; Lundberg, P.; Forsgren, M.F.; Gerdle, B.; Dong, H.J. Fibromyalgia in Women: Association of Inflammatory Plasma Proteins, Muscle Blood Flow, and Metabolism with Body Mass Index and Pain Characteristics. Pain Rep. 2022, 7, E1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinkovich, A.; Livshits, G. Sarcopenic Obesity or Obese Sarcopenia: A Cross Talk between Age-Associated Adipose Tissue and Skeletal Muscle Inflammation as a Main Mechanism of the Pathogenesis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 35, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Lumbreras, L.; Ruiz-Cárdenas, J.D.; Murcia-González, M.A. Risk of Secondary Sarcopenia in Europeans with Fibromyalgia According to the EWGSOP2 Guidelines: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 60, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, M.C.; El Mansouri-Yachou, J.; Casas-Barrag, A.; Molina, F.; Rueda-Medina, B. Composition with Pain, Disease Sctivity, Fatigue, Dleep and Snxiety in Women with Fibromyalgia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 13. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.