Abstract

Background: Cervical cancer remains a major global health challenge, ranking fourth among malignancies in women, with an estimated 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths in 2022. Despite advances in vaccination and screening, incidence and mortality remain disproportionately high in low- and middle-income countries. The disease is strongly linked to persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types, predominantly HPV 16 and 18, whose E6 and E7 oncoproteins drive cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and invasive cancer. This review summarizes current evidence on clinically relevant biomarkers in HPV-associated CIN and cervical cancer, emphasizing their role in screening, risk stratification, and disease management. Methods: We analyzed the recent literature focusing on validated and emerging biomarkers with potential clinical applications in HPV-related cervical disease. Results: Biomarkers are essential tools for improving early detection, assessment of progression risk, and personalized management. Established markers such as p16 immunostaining, p16/Ki-67 dual staining, and HPV E6/E7 mRNA assays increase diagnostic accuracy and reduce overtreatment. Prognostic indicators, including squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC-Ag) and telomerase activity, provide information on tumor burden and recurrence risk. Novel approaches—such as DNA methylation panels, HPV viral load quantification, ncRNAs, and cervico-vaginal microbiota profiling—show promise in refining risk assessment and supporting non-invasive follow-up strategies. Conclusions: The integration of validated biomarkers into clinical practice facilitates more effective triage, individualized treatment decisions, and optimal use of healthcare resources. Emerging biomarkers, once validated, could further improve precision in predicting lesion outcomes, ultimately reducing the global burden of cervical cancer and improving survival.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer ranks fourth among neoplasia affecting women, accounting for approximately 8% of total cancer cases and deaths. The incidence in low- and middle-income countries is disproportionately high, with rates significantly higher than in high-income countries [1]. According to data from GLOBOCAN on cervical cancer, there were approximately 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths in 2022, with over 19.3 per 100,000 of these cases occurring in low- and middle-income countries. Most of the cases are found in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe. In Romania, the incidence rate is approximately three times the European Union average, being one of the highest in this region. In Romania, it is the third most frequently diagnosed type of cancer, with a prevalence of 11,278 (115.3 per 100,000). A total of 3368 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2022, reaching almost 1793 deaths each year. While mortality is slowly decreasing, incidence remains high and constant, although it is already at an elevated level. Improvements have been observed in younger women, though significant disparities compared to the European average persist [2,3].

Cervical cancer remains preventable—its prolonged pre-clinical phase (spanning 1 to 2 decades) makes it particularly amenable to screening programs. Vaccination and screening are the primary and secondary prevention measures, respectively. Risk stratification for the progression of cervical dysplastic lesions is essential in current practice to manage high-risk cases identified through screening [4,5]. Furthermore, its pre-cancerous lesions can often be treated conservatively, without the need for hysterectomy, offering elevated cure rates [6,7].

Various combined techniques, including immunocytochemistry/immunohistochemistry, molecular biomarkers, microbiome testing methods, and artificial intelligence programs, support clinical decision-making [8,9]. To understand the mechanism of action of these risk stratification markers, it is necessary to understand the basic data on the pathophysiology of cervical cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, cervical carcinogenesis, and the natural progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [10,11,12].

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection was identified as the primary cause of cervical cancer development [2,11,13,14]. As epidemiological studies reflect, HPV DNA is detected in nearly all cervical cancer samples (99,7%), compared to the significantly lower detection rates in controls [15,16]. While HPV is a key factor in the majority of cervical cancer cases, only a small proportion of the infected women will develop invasive cervical cancer [14,16]. This indicates the involvement of additional genetic or environmental factors in cervical carcinogenesis, which can be divided into three categories, as follows:

- The cervical immature transformation zone (a vulnerable area that facilitates HPV infection and its persistence).

- External risk factors, such as infectious agents, with HPV being the main cause, and the others acting as co-carcinogens (Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Herpes Simplex 2 Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr Virus, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas), as well as hormonal factors/anti-estrogens, nutritional factors, tobacco smoke exposure, and radiation (ionizing or ultraviolet).

- Impaired host immunity. The oncogenic potential of HPV, viral load (quantified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, qPCR), and infection persistence are key predictors of progression from HPV infection to CIN [14,16,17].

Recent advancements in understanding the molecular mechanism behind HPV-related cervical carcinogenesis have led to the identification of potential new biomarkers that could aid in risk assessment of cervical cancer. These biomarkers might help reduce the need for biopsies. However, the real challenge for gynecologists lies in integrating these biomarkers into routine clinical practice to better assess the likelihood of cervical lesions progressing to cancer [18,19].

There are over 100 different HPV genotypes [20], with at least 42 types infecting the genital tract [21]. These types vary in their ability to cause malignant transformation, leading to the classification of HPV into low-risk (LR) and high-risk (HR) categories. The most prevalent HR types associated with cervical cancer are HPV types 16 and 18, found in more than 80% of cases. Other HR types include HPV 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59. LR types (6, 11, 26, 53, 66, 67, 68, 70, 73, and 82), which can lead to dysplasia or genital warts, are rarely associated with cancer. With the development of HPV testing, it is now possible to determine whether a patient carries HR or LR types, which has proven to be a valuable tool in managing patients with low-grade Pap smear abnormalities [14,22,23].

HPV infects basal layer cells, entering through microtrauma areas created during sexual friction. The viral genome penetrates the cell membrane after shedding its capsid and is transported to the cell’s nucleus, where it establishes an episomal-type infection. At this point, the virus is present in the host’s basal cells in a small number of copies, detectable only through viral testing, and does not cause clinical or subclinical manifestations (as determined by colposcopic, cytological, and histological examinations). This phase, known as latency, is characterized by the virus’s persistence for extended periods. The subsequent steps of viral infection depend on three factors: the viral type, the infected site, and the host’s local epithelial immunity. The mechanism by which HPV infection initiates CIN lesions and cervical cancer begins with viral penetration of basal cells, followed by integration into the host genome near fragile sites and proto-oncogenes, leading to oncogene activation. When the viral DNA integrates, the circular DNA chain is cleaved, and only the fragment containing the E6, E7, and URR genes integrates. The absence of the E2 gene, which normally inhibits the expression of E6 and E7, results in their overexpression. The following steps are represented by the inhibition of the cell growth control mechanisms (E6 and E7 block tumor suppressors p53, which protects the cell from the accumulation of secondary mutations caused by DNA damage by either repairing the damage or inducing apoptosis, and retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (PRB), which regulates the entry into DNA synthesis at an appropriate stage of the cell cycle), resulting in cellular immortalization and malignant transformation (involving cyclins and telomerase hTERT) [24,25,26,27,28,29].

The Richard Classification of CIN, the classic histopathological classification, introduces the concept of gradual lesion progression from CIN 1 to CIN 3/in situ carcinoma to invasive carcinoma, based on the depth of the epithelial involvement and nuclear atypia [30]. Ostor’s article is a cornerstone study because it analyzed the potential evolutionary outcomes of CIN lesions according to their histological grade [31].

There are three possible outcomes for preneoplastic lesions: regression, persistence (stationary), or progression. In a study that synthetized the results of all publications from the last 40 years regarding the natural history of CIN, the following rates were recorded at 5 years: CIN 1 regresses in 80% of cases, progressing to CIN 3 in 10% and invasion in 1% of cases, while CIN 3 regresses in around 32% of cases but can progress to invasive cancer in 12%. In order to avoid overdiagnosis and overtreatment, these numbers force us to be cautious and to correctly stratify the risk of progression to CIN 3 and invasive cancer in cervical HPV infections [30,31,32,33].

Over the past several years, significant advances in understanding the molecular pathways of HPV-associated cervical carcinogenesis have revealed a growing number of potential biomarkers. Some of these may reduce the need for invasive biopsies. A rational taxonomy of these biomarkers should reflect the stage at which they emerge within the HPV-induced oncogenic cascade [34,35,36]. Accordingly, these biomarkers may be categorized as follows:

- Cell cycle regulation markers;

- Proliferation markers;

- Markers of epithelial organization and differentiation;

- Transcription factors and signaling pathway components;

- Apoptotic markers;

- Markers of chromosomal stability;

- Immune recognition markers [34,35].

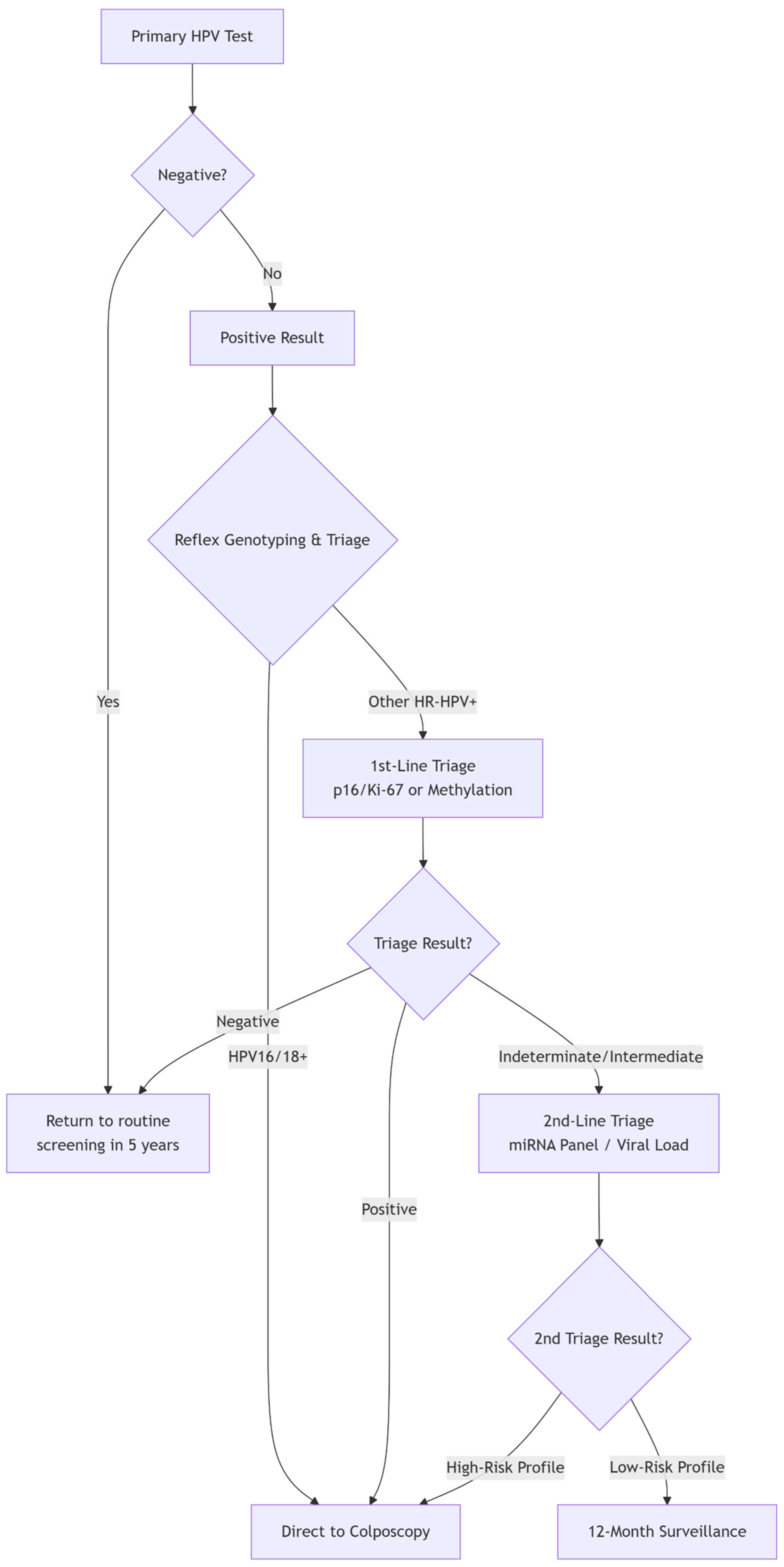

The paradigm of cervical cancer prevention has fundamentally shifted from cytology-based to molecular-based screening, with high-risk HPV (hrHPV) DNA testing established as the cornerstone. Major guidelines, including those from the World Health Organization (WHO), now endorse primary hrHPV testing as the preferred method for cervical screening in women aged 30 and above [37].

HPV DNA testing demonstrated higher sensitivity (97.5%) but lower specificity (85.1%) for detecting CIN3+ compared to cytology and VIA. While sensitivity was consistent across ages, specificity was highest in women under 35 (89.4%). Raising the HPV positivity cutoff from 1 pg/mL to 2 pg/mL reduced overall positivity (16.3% to 13.9%) with minimal loss in sensitivity (97.5% to 95.2%). In women under 35, a 10 pg/mL cutoff maintained high sensitivity (97.7%) while significantly improving specificity to 93.5% [38].

This high sensitivity provides a greater safety margin, allowing longer screening intervals (e.g., every 5 years) and greater reassurance against missed pre-cancerous lesions. Furthermore, as a molecular test, it is more objective than the morphological interpretation required for Pap smears.

The primary strength of hrHPV testing is also the source of its main clinical challenge: low specificity. The test detects the presence of oncogenic HPV types but cannot distinguish between transient, clinically inconsequential infections and persistent infections that will progress to pre-cancer. In most populations, the vast majority of HPV-positive women, especially younger ones, will not have CIN2+. This low positive predictive value leads to significant overtreatment, patient anxiety, and an unsustainable burden on colposcopy services.

It is precisely this limitation—the high sensitivity but low specificity of primary HPV testing—that defines the central mission of contemporary biomarker research: to develop effective triage strategies. The biomarkers discussed in the following sections (e.g., partial genotyping, p16/Ki-67 dual stain, and methylation) are all evaluated based on their ability to effectively stratify HPV-positive women, identifying those at the highest risk who require immediate colposcopy from those who can be safely returned to surveillance.

Biomarkers have multiple applications in the evaluation and management of pre-cancerous cervical lesions. They can increase the sensitivity of cervical screening programs, allowing extended screening intervals without compromising safety and ensuring efficient triage and resource allocation. Biomarker-based stratification can help differentiate between intermediate lesions with a high probability of regression and those with a high potential for progression, allowing for surveillance and reducing the need for unnecessary invasive procedures. They also enable the monitoring of disease progression and the detection of recurrences after therapeutic interventions. The resulting risk stratification enables a more individualized clinical approach, avoiding unnecessary, invasive, and costly interventions while still allowing for early detection of silent or occult cancers. Given this expanding array of candidates, establishing a biobank containing cervical lavages, histology specimens, and blood and plasma samples has become essential to support molecular investigations. However, as the number of biomarker candidates grows, it becomes paramount to map their developmental trajectories from discovery to clinical validation. Most biomarkers will ultimately not demonstrate clinical utility and may encounter numerous pitfalls; thus, extensive testing, validation, and refinement are required before any candidate can enter clinical practice [35,39,40,41,42].

This study aims to consolidate and critically evaluate the most relevant biomarkers currently available for HPV-associated CIN lesions and cervical cancer, focusing on their clinical utility in lesion progression, screening, and risk stratification. Given the growing number of proposed biomarkers, the study seeks to provide a structured framework to guide clinicians in selecting validated, stage-specific biomarkers within the HPV-induced oncogenic pathway. Special attention is given to the clinical challenge of managing CIN2-3 lesions in young women of reproductive age, where excisional treatment may compromise future obstetric outcomes. Ultimately, the study aims to support personalized, non-invasive approaches to cervical disease management, particularly given the disease’s increasing prevalence.

2. Methodology

To ensure a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of cervical cancer biomarkers, a systematic literature search was conducted. The electronic databases PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched for relevant articles published between 2020 and 2024. The search strategy combined key terms and Medical Subject Headings (MeSHs) related to cervical cancer and biomarkers. Core search terms included the following: (“cervical cancer” OR “cervical intraepithelial neoplasia” OR “CIN” OR “squamous intraepithelial lesion” OR “LSIL” OR “HSIL”) AND (“biomarker” OR “methylation” OR “DNA methylation” OR “S5 classifier” OR “p16” OR “Ki-67” OR “dual stain” OR “microbiome” OR “vaginal microbiota” OR “telomerase” OR “hTERT” OR “SCC-Ag” OR “viral load” OR “HPV genotyping”) AND (“screening” OR “triage” OR “diagnosis” OR “prognosis”).

The reference lists of retrieved review articles and key primary studies were also manually screened to identify additional relevant publications.

3. Classification of Cervical Cancer Biomarkers by Clinical Uses

The current screening already uses viral indicators, such as genotype-specific hrHPV detection. Cellular biomarkers such as p16INK4a reflect the underlying transformation process regardless of HPV type, making them attractive as single-marker strategies. In histopathology, p16INK4a staining significantly improves the reproducibility of pre-cancerous lesion classification, while in cytology, it enhances the accuracy of triaging equivocal findings. Nevertheless, more molecular biomarkers are partially implemented or under evaluation.

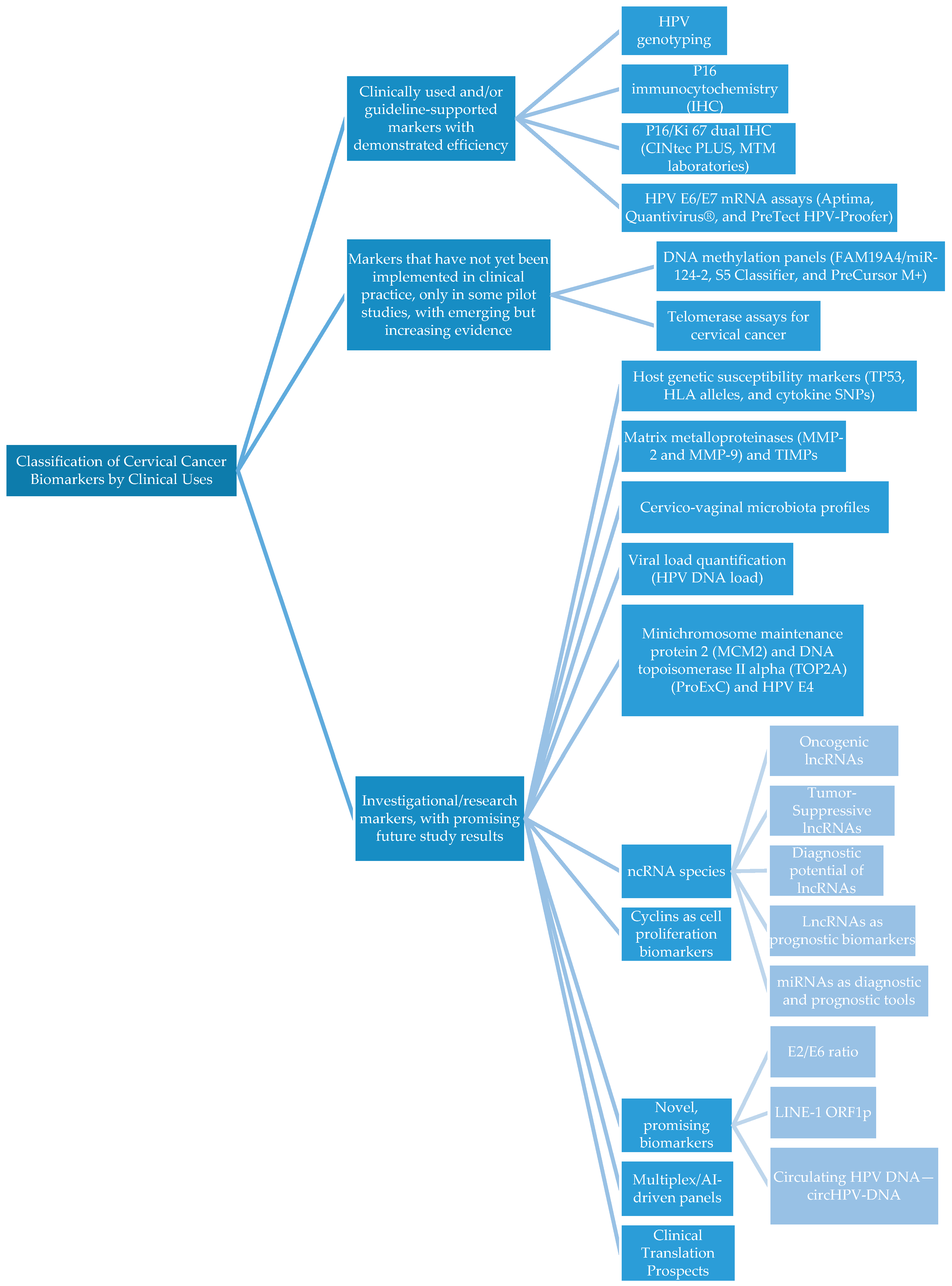

According to the literature search, the biomarkers were classified into three main categories based on guideline implementation, development status, and IVD certification (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Biomarker types, detection methods, and clinical uses.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of cervical cancer biomarkers.

3.1. Clinically Used and/or Guideline-Supported Markers with Demonstrated Efficiency

3.1.1. HPV Genotyping

Identifying the specific HPV genotype has become a critical test for cervical cancer screening and patient management due to its strong correlation with oncogenic potential and lesion progression [43]. HPV genotyping enables stratification of patients by viral oncogenic risk [34]. Detection of the main oncogenic type, such as HPV16 and HPV18, identifies women at the highest risk for developing high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2/3) or invasive carcinoma, supporting referral to colposcopy or enhanced surveillance. Genotype information also aids in triaging hrHPV-positive women when cytology results are ambiguous, reducing unnecessary interventions and improving resource allocation [44].

Persistent hrHPV infection can predict the progression of CIN lesions. HPV detection enables clinicians to monitor viral clearance or persistence over time, guiding follow-up intervals. Several studies demonstrated that women with persistent hrHPV infections are more likely to experience lesion progression, whereas clearance is associated with regression and lower long-term cancer risk [45].

HPV genotyping, as an implemented technique, improved triage, reduced overtreatment, and allowed personalized follow-up. Identifying high-risk infections early informs decisions on colposcopic evaluation, excisional procedures, and the frequency of surveillance. Additionally, genotype-specific data can contribute to patient counseling, vaccination strategies, and population-level screening policies. Linking specific viral types to the risk of lesion progression and persistence guides clinical management and facilitates personalized patient care.

3.1.2. P16 Immunocytochemistry (IHC)

P16 IHC is a surrogate marker of transforming (oncogenic) hrHPV infection. Overexpression of p16 in cervical tissue is associated with CIN 2 + lesions and helps distinguish between lesions likely to progress versus those likely to regress [46].

Studies show that using p16 with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) histology improves diagnostic reproducibility, reducing the number of misgraded or overtreated cases [47]. The Dutch study by Ebisch et al. in 2022 [48] underscores the use of p16 IHC as an adjuvant to morphology to improve triage efficiency. The authors analyzed 326 samples and concluded that adding p16 IHC led to more accurate stratification of CIN lesions, with fewer CIN 1/2 cases and more “no CIN” or CIN 3 cases, thereby avoiding overtreatment [48]. However, the literature is controversial about the use of p16 IHC alone, with the results of other studies underlining a lower specificity and more false-positive results; this supports a lack of sufficiency in triaging cases that should be referred for colposcopy or immediate treatment, with the staining being strong but not always specific enough, especially in low-grade lesion samples from younger women [47,48,49,50].

P16 immunohistochemistry (IHC) has garnered significant interest as a diagnostic and triage tool for its potential to improve cytology sensitivity and HPV genotyping specificity. The results of a study performed by Cuzick et al. on 1091 women, which included cytologic evaluation, HPV genotyping, p16 IHC analysis, and cervical biopsy, detected a significantly higher positivity rate in high-grade CIN 2+ lesions, when compared to normal or low-grade cervical ones (89.2% versus 10.2%, p < 0.01), with similar sensitivity and higher specificity compared to genotyping [51]. Thus, p16 appears to correlate strongly with lesion severity, reflecting both viral and host-related carcinogenic processes [52], especially in HPV 16- and 18-positive cases [53]. These observations are reinforced by Mastutik et al., who underline the diffuse p16 expression in cases with hrHPV infections and sporadic/focal or negative p16 expression in cases with hrHPV infections, thus making it a reliable surrogate marker for hrHPV activity in cervical lesions, helping to distinguish lesions with high malignant potential [54].

Khamseh et al.’s (2025) [55] study reinforces the idea that p16 can be a valuable biomarker of HPV lesion progression and oncogenic activity, reflecting viral load and genomic integration and providing a direct biological signal of transformation risk, justifying its use in diagnosis and further triage. IHC p16 expression was absent in normal cervical epithelium, had a low expression in CIN I cases (12.5%), and increased expression in CIN II (72.7%), CIN III (88.9%), and cervical carcinoma patients (90%) [55]. These differences were statistically significant (p < 0.01), and the expression also correlated with higher HPV-16 viral loads (p < 0.05) [55].

The post hoc analysis of the PROHTECT-3B trial revealed that p16 alone had higher sensitivity for CIN3+ than cytology, but lower specificity. Its adjuvant uses decrease overtreatment by reducing false-positive CIN2 diagnoses, with confidence improved in about 50% of cases [48]. Similar results were obtained in 2025 by Usta et al., who analyzed 192 cytological specimens and found that p16 positivity increased significantly with lesion severity [56].

The study by Damgaard et al. (2022) [57] on the predictive value of p16 for CIN2 regression found that low or absent p16 expression, combined with a positive HPV E4 result, indicates a cervical lesion more likely to regress. The authors underline that p16 overexpression often indicates a loss of cell cycle control under the influence of an oncogenic HPV effect, suggesting that these markers can be used to further classify CIN2 cervical lesions [57].

Song et al. (2020) [58] assessed p16 expression both as a primary screening tool and a secondary triage tool for 1197 cytology specimen slides, obtaining the same results: p16 IHC expression increased with the severity of dysplasia. The test’s sensitivity was similar to that of HPV genotyping, with twofold higher specificity. Compared with cytology, sensitivity was higher for CIN2+ lesions, with comparable specificity as a primary screening tool. As a secondary triage tool, p16 proved higher specificity after both cytology and HPV genotyping primary screening, with lower colposcopy referrals, representing a promising alternative or adjunct to both cytology and HPV testing [58].

He et al. published a flow cytometry-based study of p16 detection that included 24,100 screened women. The flow cytometry test used a monoclonal antibody clone to quantify marker expression in exfoliated cervical samples, demonstrating that the method outperforms cytology and HPV co-testing. The results consolidate p16′s position as a powerful quantitative biomarker, with improved accuracy and predictive power, reducing unnecessary colposcopies and stratifying women with low-grade lesions into high- and low-risk progression groups [59]. Another large-scale study involving 73,624 women in China, including 2557 hrHPV-positive cases, introduced p16 testing. The study demonstrated improved sensitivity and specificity, particularly among women over 50 years old, while also helping to minimize overtreatment [60].

Despite many promising findings regarding p16 use in HPV-induced cervical lesions, Miranda-Fanconi et al. (2024) reported only modest predictive value in a relatively small cohort, suggesting that p16 testing may be more suitable as part of a biomarker panel rather than as a stand-alone test [61]. The discrepancies across studies may stem from differences in sample size, which could introduce bias, or from variations in detection techniques. For instance, Usta et al., Hou et al., and Song et al. employed p16 immunocytochemistry [56,58,60], whereas Ebisch et al., Damgaard et al., and Miranda-Fanconi et al. utilized immunohistochemistry [48,57,61].

3.1.3. P16/Ki 67 Dual IHC (CINtec PLUS, MTM Laboratories)

The immunocytochemistry dual staining assay for p16/ki-67 plays a central role in cervical cancer screening and triage [62].

The inactivation of p53 and the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (pRb) by the E6 and E7 hrHPV oncoproteins alters several cellular pathways relevant to cell transformation and cancer development. E7 oncoprotein expression leads to pRb inactivation, the overexpression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 (p16INK4a), and aberrant proliferation, as evidenced by increased Ki-67 expression. While p16 functions as a tumor suppressor by blocking G1–S phase progression, its overexpression in HPV-infected cells signals oncogenic transformation [62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. On the other hand, Ki-67 protein is a reliable marker of proliferation, and its co-expression with p16 within the same cell provides a direct indication of abnormal cell growth as a result of HPV oncogenic activity. The positive test for both biomarkers allows the triage of CIN2/3 cases [62,69].

A positive test requires dual positivity in the same cell, whereas the absence of co-expression is considered negative. The dual staining approach offers higher sensitivity than Pap cytology and provides an objective criterion for identifying patients at increased risk of developing high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs), who should be referred for colposcopy. Unlike p16, which may stain normal metaplastic cells, Ki-67 is restricted to proliferating cells, thereby enhancing diagnostic specificity. The method, first promoted by Christine Bergeron’s group in France, has been widely studied as a triage tool for women with ASC-US or LSIL cytology, as an alternative to HPV genotyping [63,64,65,66,70].

In Thailand, Srisuttayasathien et al. (2024) conducted a cross-sectional study, comparing p16/ki-67 dual staining with liquid-based cytology (LBC) in HPV-positive women, and found a comparable performance, with higher sensitivity but somewhat lower specificity than that reported in ATHENA, confirming the reproducibility of dual staining even in low-resource settings [71]. El-Zein et al. (2020) retrospectively analyzed 492 cervical specimens and showed that dual staining was more specific than HPV testing, particularly among younger women [72]. Similarly, Magkana et al. (2020) emphasized its specificity advantage over HPV genotyping, helping reduce unnecessary procedures [73]. The FRIDA Mexico study by White et al. found fewer unnecessary colposcopy referrals when dual staining was used in HPV16/18-positive women [74]. Additional studies reinforce these findings: Gothwal et al. (2021) showed that dual staining shows high sensitivity and specificity, especially for ASCUS and LSIL patients [75], while Luo et al. (2024) suggested its role in personalized CIN management through risk stratification [76]. Large-scale trials, including IMPACT and ATHENA, as well as real-world evidence from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) cohort, have validated dual staining as a robust triage tool, consistently outperforming cytology in sensitivity while providing greater specificity than HPV testing. By analyzing data from the New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening 2 (NTCC2) trial, Benevolo et al. (2024) combined dual staining with extended genotyping, achieving refined risk stratification that could reduce colposcopy referrals and optimize long-term surveillance intervals [77]. Thrall et al. provided a comprehensive review of the dual staining technique, highlighting technical, interpretative, and cost-related challenges [78]. Despite these limitations, multiple international studies support the use of this technique as a viable triage option, as revealed by Olivas et al. (2022), who summarized the findings from the ATHENA and IMPACT trials [79]. Dual staining seems to be superior in the screening process, especially in women under 30 years old. Secosan et al. reported higher specificity than HPV or colposcopy alone, supporting its use as a triage tool in the younger population [80]. The prospective longitudinal study by White et al. demonstrated that smoking significantly increases the risk of both p16/Ki-67 positivity and progression to CIN2+/CIN3+, underscoring the importance of lifestyle factors in risk stratification and biomarker interpretation [74]. Although CINtec PLUS has been FDA-approved in the United States since 2020, interesting findings published by Ying Li et al. (2022) [81] warrant further investigation. In their comparison of the CINtec PLUS and Dalton assays, the authors concluded that Dalton may offer a superior performance, with lower false-positive rates for identifying high-grade CIN [81]. A limitation of dual staining, highlighted by Stoler et al. in the Onclarity trial, is that although dual staining and HPV genotyping show comparable performance in detecting CIN3+ lesions, genotyping offers broader applicability, particularly because it is compatible with self-sampling [82]. Moreover, Macios and Nowakowski emphasized that false-negative results in dual staining are often linked to interpretative challenges, insufficient reader training, and methodological inconsistencies [83].

However, a real-life study showed that incorporating p16/Ki67 dual staining as a triage method for women who test positive for hrHPV—using limited genotyping—provides superior diagnostic accuracy for identifying cervical pre-cancer compared to cytology-based triage within primary HPV screening programs. The markedly higher specificity of the dual stain approach suggests a substantial potential to reduce the number of unnecessary colposcopies, both among HPV16/18-positive women and those infected with other high-risk HPV genotypes. Therefore, implementing p16/Ki67 dual staining into cervical screening algorithms could significantly enhance secondary prevention strategies for cervical cancer [84].

Harper et al. (2025) showed that numerous studies across various geographic regions demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity of p16/Ki67 dual staining when used for the triage of HPV-positive women [85]. The p16/Ki67 dual staining method was validated in the large prospective PALMS study (27,349 women), showing significantly higher sensitivity than cytology for detecting CIN2+ (86.7% versus 68.5%, p < 0.001), as well as comparable specificity (95.2% versus 95.4%, p = 0.15) [86]. In McMenamin’s study, the kappa values for agreement between p16/Ki-67 dual stain reviewers fell within the “very good” range [87]. In contrast, the summary kappa values reported in other studies indicated “good” inter-reader agreement, ranging from 0.61 to 0.71 [88,89,90]. Agreement improves when more dual-stained cells are present, while slides with only a single positive cell introduce greater uncertainty. Variability also increases with weak p16 staining, poor cell morphology, or background artifacts. Although basic training ensures reasonable consistency, additional expert-led training and reviewing of ambiguous cases are essential to enhance accuracy and minimize inter-laboratory differences [91].

3.1.4. HPV E6/E7 mRNA Assays (Aptima, Quantivirus®, and PreTect HPV-Proofer)

Detection of E6/E7 messenger RNA indicates viral integration into the host genome and the initiation of oncogenic transformation, allowing for the identification of both hrHPV strains and the resulting cervical lesions. The literature highlights its strong correlation with CIN2/3 lesions. In some countries, the HPV E6/E7 mRNA test is used alongside cytology to complement primary screening based on HPV DNA detection [92,93].

Derbie et al. (2020) [94] conducted a systematic review of 29 studies including 23,576 women aged 15–85 years with varying cervical pathologies. All participants underwent HPV E6/E7 mRNA testing following positive cytology or HPV DNA results. Among the available assays, the Aptima test has been the most extensively investigated. Seven of the included studies evaluated the role of E6/E7 mRNA testing in triaging women with abnormal Pap smears or HPV-positive results, while eight studies compared its diagnostic accuracy with HPV DNA testing. E6/E7 mRNA-based assays differ as follows: the PreTect HPV-Proofer targets only five high-risk genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, and 47), yielding higher specificity, whereas Aptima and Quantivirus cover a broader range of genotypes, offering greater sensitivity but lower specificity. This type of test provides more clinically meaningful information, as it reflects viral oncogenic activity and correlates more strongly with lesion severity. It helps identify women at higher risk of cervical cancer while allowing longer follow-up intervals for those testing negative, with a negative predictive value ranging from 77% to 99.8% [92,93,94,95].

Downham et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 22 studies, revealing that E6/7 oncoprotein testing has high specificity across populations (>82%) but moderate sensitivity (46.9–75.5%) depending on HPV risk groups. Specificity was notably lower in HPV 16/18-positive women compared with other groups. Testing E6/E7 oncoprotein seems promising for triaging HPV-positive women, although it demonstrated a lower sensitivity, likely due to limited viral integration in non-progressing pre-cancerous lesions. Further longitudinal studies are needed to validate its predictive role [96]. Singini et al. found that HPV 16/18 E6/E7 antibodies showed high specificity but low sensitivity for detecting CIN2+ lesions, suggesting limited applicability as a primary diagnostic tool but possibility as a surrogate marker of immune response in advanced disease [97]. A 2024 meta-analysis by Xu et al., which included 2224 women, confirmed the test’s high sensitivity for CIN2+ detection and its ability to reduce missed diagnoses, while its specificity was relatively low. This low specificity raises concern about potential overdiagnosis and unnecessary interventions. An important limitation of this meta-analysis is that it did not directly compare this test with other screening modalities, thereby perhaps limiting essential comparative aspects [98]. Observational studies have provided additional insights into clinical application. Jin et al. (2023) demonstrated its value for triaging colposcopy referrals in women with ASC-US cytology and in postmenopausal women positive for E6/E7 mRNA [99]. Zhang J et al. (2024) confirmed an age-dependent performance, with higher efficiency in women aged between 35 and 44 years old and those between 55 and 64 years old, but less reliable in peri-menopausal women [100]. Moreover, Liu Y et al. (2023) and Gupta et al. (2022) reported superior specificity of E6/E7 mRNA testing compared to DNA HPV assays for CIN2+ detection, suggesting its potential use in primary screening and immediate colposcopy referral for HPV-positive patients with negative cytology [101,102]. Moreover, Liu et al. (2020) and Ren et al. (2019) [103,104] proposed a quantitative assay of the E6/E7 copy number to better differentiate low-grade from high-grade lesions, although the optimal cutoff value remains to be established. E6/E7 mRNA testing achieves high sensitivity and a low rate of missed CIN2+ lesions, but its moderate specificity increases the risk of overdiagnosis and unnecessary colposcopy referrals, limiting its role [103,104]. Its prognostic utility, however, seems promising, as its negative expression correlates with higher rates of lesion regression.

3.2. Markers That Have Not Yet Been Implemented in Clinical Practice, Only in Some Pilot Studies, with Emerging but Increasing Evidence

3.2.1. DNA Methylation Panels (FAM19A4/miR-124-2, S5 Classifier, and PreCursor M+)

hrHPV detection, recommended by the WHO for cervical cancer screening, has proven more sensitive than cytology in detecting CIN lesions. However, its specificity remains limited, as the majority of infections are transient, with around 80% clearing the virus within one year of acquisition. Thus, this underlies the need for more specific assays for the triage of HPV-positive women who need further colposcopy referral, as only about 20% of hrHPV-related lesions actually progress. The process of aberrant DNA methylation occurs during pre-cancerous progression, thus permitting the identification of cases with HPV infection that will progress to cancer. DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification that inactivates host tumor suppressor genes and serves as an early signal of malignant transformation. Methylation levels rise with increasing CIN severity, providing a molecular signal of malignant potential. Unlike Pap cytology or dual staining, methylation assays can be performed on either clinician-collected or self-collected samples, simplifying logistics and reducing reliance on observer interpretation. However, costs limit their availability in low-resource settings. Methylation assays have higher specificity but somewhat lower sensitivity than HPV DNA screening, making them particularly valuable for triage rather than primary screening. Candidate genes frequently evaluated for hypermethylation include CADM1, MAL, miR-124, FAM19A4, PAX1, and SOX1 [105,106,107]. A meta-analysis of 43 studies by Chan KKl et al. reported pooled sensitivity and specificity of 63.2% and 75.9%, respectively, for methylation testing, though the optimal gene panel is still debated. Several commercial assays are currently under development or already in clinical use: the QIAsure Methylation test (targeting FAM19A4 and miR124-2), S5-classifier (including EPB41L3 and HPV16-L1, HPV16-L2, HPV18-L2, HPV31-L1, and HPV33-L2), and GynTect® (including ASTN1, DLX1, ITGA4, RXFP3, SOX17, and ZNF671). Clinical studies suggest potential prognostic applications as well. For example, women who test negative for PAX1 methylation exhibit a significantly lower risk of subsequently developing high-grade lesions than those with negative cytology or even HPV16/18 positivity. This supports the notion that HPV-positive but PAX1-negative women could safely undergo extended surveillance intervals [106,108].

Accumulating evidence supports the role of DNA methylation assays as complementary tools to hrHPV testing in cervical cancer screening. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Salta et al., including 23 studies, reported pooled sensitivity ranging from 0.68 to 0.78 for CIN2+ and CIN3+ detection, with specificities of 0.75 and 0.74, respectively. The most frequently evaluated methylation markers were CADM1, FAM19A4, MAL, and miR124-2. Despite these encouraging results, significant heterogeneity in study design, populations, and cutoff definitions remains an obstacle to translation into routine implementation [108]. A larger review and meta-analysis of over 16,000 women across 43 studies, conducted by Kelly et al., noted that DNA methylation detection achieves a higher specificity than cytology for ASC-US + lesions, and a higher sensitivity than HPV 16/18 genotyping, with a reported positive predictive value (PPV) of 53% for CIN2+ and 35% for CIN3+. The assay offers notable advantages, including automation, reduced subjectivity, and compatibility with self-sampling approaches [105]. Several host-gene markers and panels have been validated in both prospective and retrospective settings. PAX1 and ZNF582 methylation are strongly correlated with lesion severity and p16/ki-67 expression and may act as triggers in the progression from HPV infection to CIN3+ [76]. The GynTect® assay has shown high specificity and strong negative predictive value, thereby reducing unnecessary colposcopies [109,110,111,112]. FAM19A4/miR124-2 has been validated extensively, including in the POBASCAM 14-year follow-up, where a negative result was associated with a low long-term cervical cancer risk among HPV-positive women, outperforming cytology [113]. Other gene panels have also demonstrated clinical feasibility. ASCL1/LHX8 methylation panel was validated in the Dutch IMPROVE trial, yielding 76.9% sensitivity and 74.5% specificity for CIN3+, comparable to HPV16/18 genotyping [114]. The S5 methylation classifier, combining both viral and host genes, showed superior sensitivity compared to cytology and genotyping, with the advantage of being suitable for self-sampling and reflex testing [115]. Fackler et al. (2024) proposed a five-gene panel comprising FMN2, EDNRB, ZFN671, TBXT, and MOS, showing robust sensitivity and specificity across cohorts from Vietnam, South Africa, and the United States [109]. The same year, Vieira-Baptista et al. confirmed the feasibility of GynTect® in organized screening, detecting 78% of CIN3+ cases while reducing colposcopy referrals by 75% [110]. Ren et al. supported the single ZFN671 methylation marker performance, suggesting its cost-efficiency for triage [111], while Chen et al. optimized a three-gene methylation panel, including JAM3, PCDHGB7, and SORCS1, that outperformed cytology and HPV 16/18 genotyping in CIN3+ detection [112]. Importantly, Louvanto et al. (2024) [107] investigated methylation patterns in HPV-vaccinated women. The study showed lower methylation levels in HSIL associated with non-HPV16/18 genotypes, suggesting limited progression potential. This observation underscores the need for tailored management strategies in vaccinated cohorts, as the predictive value of methylation testing may be lower than in unvaccinated populations [107].

3.2.2. SCC Antigen (SCC-Ag) in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Cervical Cancer

Squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC-Ag, also called SCCA, with isoforms SCCA1/SERPINB3 and SCCA2/SERPINB4) is a glycoprotein first isolated from squamous carcinomas and is widely studied as a serum tumor marker in cervical squamous cell carcinoma [116]. SCC-Ag is not disease-specific, as its expression can be raised in other squamous malignancies and some benign conditions; however, in cervical cancer, it correlates with tumor burden and biologic aggressiveness and has practical clinical applications in pretreatment risk stratification, monitoring treatment response, and surveillance for recurrence [117].

Serum SCC-Ag levels increase with FIGO stage, primary tumor size, nodal involvement, and other adverse pathologic features [118]. Several studies have shown that higher pretherapy SCC-Ag levels are associated with more advanced disease and a greater likelihood of lymph node metastasis; therefore, SCC-Ag can complement imaging and clinical staging by identifying patients at higher risk who may benefit from intensified staging or tailored treatment planning [119,120,121]. However, sensitivity is stage-dependent (lower in early FIGO I disease, and higher in advanced stages), so SCC-Ag should not be used as a sole screening tool [117].

Elevated SCC-Ag pretreatment is repeatedly associated with worse outcomes (lower disease-free and overall survival) across cohorts treated with surgery or definitive chemoradiotherapy [122]. The magnitude of SCC-Ag and its failure to normalize after therapy have been incorporated into prognostics, predicting distant recurrence and survival; patients with high pre- or persistently elevated post-treatment SCC-Ag have higher rates of local, regional, and distant failure. These properties make SCC-Ag a useful biomarker for risk stratification and for informing decisions such as the extent of surgery, need for adjuvant therapy, or more intensive surveillance [121].

Serial SCC-Ag measurements during and after treatment reflect tumor response: most responsive tumors show marked declines in SCC-Ag during chemoradiation, while persistently high or rising levels predict residual disease or early recurrence—often preceding clinical or radiological detection by months [121,123]. Recent findings support SCC-Ag as a cost-effective adjunct to follow-up algorithms for selecting patients for imaging or earlier intervention, using predefined cutoffs to trigger further evaluation [122,124]. Nonetheless, non-cancer causes of SCC-Ag elevation and transient post-treatment fluctuations require cautious interpretation [117]; this implies some limitations, along with variability in assay cutoffs between laboratories and lower sensitivity in early disease [125]. However, a newly published study refines optimal cutoffs, measurement timing, and the combination of SCC-Ag with molecular markers (HPV metrics, methylation, ctDNA) to improve early detection of recurrence and personalize follow-up [126].

3.2.3. Telomerase Assays for Cervical Cancer (The TRAPeze® Assay, Particularly with Versions Such as the TRAPeze® RT Kit, and the Telomeric Repeat Amplification Protocol (TRAP))

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme essential for telomere maintenance and cellular immortalization. While its RNA component (hTR/TERC) is constitutively expressed, the transcription of the catalytic subunit hTERT is tightly regulated and normally repressed in differentiated cells. The activation of telomerase through hTERT expression is a hallmark of malignant transformation. It has been consistently detected in exfoliated cervical cells, CIN3 lesions, and more than 90% of cervical carcinomas [127,128].

The cloning of the hTERT promoter enabled detailed analyses of its regulation. Oncogenic transcription factors such as c-Myc activate hTERT expression, whereas repressors, including WT1, Mad1, Mxi1, BRCA1, and p53, can suppress its transcription [129,130,131,132,133,134]. Epigenetic regulation also plays a critical role: the hTERT promoter is CpG-rich and subject to methylation, which correlates with transcriptional activity in tumor cells [129,135,136].

HPV oncoproteins further influence telomerase regulation. HPV16/18 E6 upregulates hTERT transcription via interactions with E6TP1 and E6AP, contributing to the immortalization of keratinocytes. Conversely, the viral E2 protein can repress hTERT by binding directly to its promoter, though this repression is frequently lost during viral genome integration in cervical cancer [137,138].

Recent work has expanded our understanding of telomerase biology. hTERT is now known to exert non-canonical functions in DNA repair, chromatin remodeling, and regulation of oxidative stress, further supporting tumor cell survival [139]. Importantly, hTERT promoter mutations (C228T and C250T), among the most frequent non-coding mutations in human cancer, have been described as strong prognostic biomarkers in glioblastoma, melanoma, and urothelial carcinoma [140], though they occur less frequently.

Elevated hTERT expression and telomerase activity correlate with HPV status, invasive potential, and poor prognosis in cervical cancer [29]. At the same time, novel therapeutic approaches—including CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of hTERT and small-molecule telomerase inhibitors—are being actively investigated as strategies to target the immortalization machinery of cancer cells [141].

Taken together, hTERT serves not only as a marker of immortalization but also as a key molecular hub integrating oncogenic signaling, viral infection, and epigenetic control in cervical carcinogenesis. Its dual role as a biomarker and therapeutic target continues to attract significant research interest.

Despite the compelling mechanistic rationale for telomerase reactivation in cervical carcinogenesis, it is important to note that all current telomerase assays, including TRAP-based methods and hTERT detection, are strictly in the research and development phase. There are currently no FDA-approved or CE-IVD-certified telomerase-based tests for cervical cancer screening in routine clinical use. Thus, while its translational potential is significant, the clinical utility of telomerase for cervical screening triage remains investigational.

3.3. Investigational/Research Markers with Promising Future Study Results

3.3.1. Host Genetic Susceptibility Markers (TP53, HLA Alleles, and Cytokine SNPs)

Although persistent HPV infection is the main driver of cervical carcinogenesis, genetic predisposition may influence progression to HSIL and invasive disease. This disparity suggests that host genetic background plays an important role in determining susceptibility, influencing immune responses, viral clearance, and genomic stability. Several germline polymorphisms in immunity, DNA repair, detoxification, and folate metabolism genes have been studied in relation to cervical cancer risk.

Candidate gene studies have explored variants in tumor suppressor and DNA repair genes, including TP53 [142], MDM2 [143], ATM [144], BRIP1 [145], CDKN1A [146], CDKN2A [147], FANCA, FANCC, FANCL [148], XRCC1 [149], and XRCC3 [150]. Immune-related genes have also been implicated, such as CD83 [151], CTLA4 [152], and CARD8 [153], as well as cytokine genes encoding TNF-α [154], ILs [155], TGFB1 [156], and IFNG [157] (Table 2). Despite numerous reports, most associations failed replication in large case–control or meta-analysis datasets, with the exception of certain HLA alleles [158]. The TP53 Arg72Pro variant remains debated [118].

Table 2.

Gene variants associated with cervical cancer risk.

Genome-wide association study (GWASs)-type approaches have provided stronger evidence for genetic susceptibility. The first GWAS in a Swedish cohort confirmed known HLA associations (e.g., HLA-B07:02, HLA-DRB113:01-DQA101:03-DQB106:03, HLA-DRB115:01-DQB106:02) and identified novel MHC loci: rs9272143 (between HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQA1), rs2516448 (near MICA), and rs3117027 (at HLA-DPB2) [163,164].

An East Asian GWAS discovered rs59661306 on 5q within ARRDC3, a tumor suppressor gene, though this finding has not been replicated in Europeans [165]. A large trans-ethnic meta-analysis (Estonian, UK, Finnish, and Japanese cohorts) identified five loci linked to invasive cervical cancer, including a novel association at LINC00339/CDC42 (rs2268177) on 1p36. Additional signals were found at DAPL1 (rs12611652) on 2q24 for cervical dysplasia and CD70 (rs425787) on 19p13 in joint analyses [166].

Rare variant sequencing has also revealed high-impact risk alleles. An Icelandic study associated PTPN14 loss-of-function variants with a markedly increased risk of cervical cancer (OR 12.7, p = 1.6 × 10−4) and earlier age at onset [132]. Since PTPN14 encodes a phosphatase targeted by HPV E7 and regulates the Hippo–YAP pathway, germline mutations may enhance oncogenic potential [167].

3.3.2. Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) and TIMPs

Research on HPV-associated cervical lesions and neoplasia has increasingly focused on the role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). These zinc-dependent endopeptidases catalyze the degradation of extracellular matrix components, a process fundamental to tumor invasion. Their proteolytic activity is endogenously regulated by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), with the broad-spectrum inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 capable of suppressing all known members of the approximately 23 MMP isoforms. In the pathogenesis of HPV-related cervical lesions, MMPs facilitate invasion and metastasis by mediating the dissolution of the basement membrane [168,169,170,171].

Increased levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 correlate with progression from CIN to invasive carcinoma, reduced overall survival, and shorter recurrence-free survival [172]. MMP-2, in particular, serves as a strong biomarker, with > 90% accuracy for identifying invasive lesions, showing progressive upregulation with lesion severity, while TIMP-2 expression remains stable. Consequently, an altered MMP-2/TIMP-2 ratio reflects a highly aggressive tumor microenvironment [168].

MMP-7 has been associated with cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, acting in an oncogenic-like manner. Zhu et al. (2018) proposed its potential clinical utility as a biomarker for HPV-induced cervical carcinoma [173].

In contrast, some studies have linked MMP-9 expression to recurrence risk, indicating its potential as a prognostic marker; however, these findings remain inconsistent and lack broad validation in the literature [174]. Overall, MMP/TIMP profiling, when combined with molecular and epigenetic biomarkers, may enhance risk stratification and guide personalized management of cervical dysplasia. Their integration into predictive algorithms could be particularly valuable in cases with equivocal biopsy findings or in monitoring patients with persistent HPV infection. However, the role of metalloproteinases as reliable biomarkers in HPV-induced lesions remains controversial and warrants further investigation [168,169,170,171,175].

3.3.3. Cervico-Vaginal Microbiota Profiles (Community State Types, and Lactobacillus Dominance Versus Dysbiosis)

Microbiome diversity is considerably greater than genomic variation: while human genomes are 99.9% identical, microbiota composition can differ by 80–90% in regions such as the palmar region or the intestine [176]. This significant variation highlights the potential of microbiome-based approaches in personalized medicine, shifting the focus from the relatively static human genome to the dynamic genetic profiles of colonizing microorganisms [176,177,178,179]. In the female reproductive tract, Lactobacillus species offer key protection through “competitive exclusion,” preventing pathogen adhesion to the vaginal epithelium. Although over 120 species have been identified, vaginal communities are typically dominated by 1 or 2 species [180]. A lactobacillus-dominated vaginal microbiota supports health by producing lactic acid, bactericidal substances, and hydrogen peroxide and by blocking pathogen adhesion [181]. This protective role is critical given that cervical cancer, primarily caused by persistent infection with hrHPV types (e.g., HPV-16 and HPV-18), remains a major health burden. While most infections are cleared, persistent HPV evades immune responses by altering Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and producing E6/E7 proteins that suppress antiviral cytokines, including IFN-α and IFN-β [182,183,184].

Dysbiosis, characterized by reduced Lactobacillus and increased anaerobes such as Gardnerella and Prevotella, is linked to persistent HPV infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Lactobacillus species modulate immunity by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10) and enhancing anti-inflammatory ones (IL-2 and IL-7), creating conditions that hinder viral persistence [185,186]. Certain strains, especially L. gasseri, can modulate epithelial immune responses and suppress HPV-positive cervical cancer cell growth without triggering inflammation [187,188,189]. The shift from a Lactobacillus-dominant community to dysbiosis alters cytokine profiles, reduces lactic acid production, and increases inflammation, contributing to HPV persistence and progression to intracervical neoplasia (CIN) and cervical cancer [184,189,190]. Vaginal flora can be classified into five community state types (CSTs): CST I—L. crispatus-dominant: most stable and protective (pH 3.8–4.4); CST II—L. gasseri-dominant: protective but less stable than CST I; CST III—L. iners-dominant: transitional and less protective; CST IV—Low Lactobacillus, high anaerobes (e.g., Gardnerella, Atopobium, and Prevotella): associated with BV; high pH: subdivided into IV-A and IV-B; and CST V—L. jensenii-dominant: protective but less common [184,185,187].

The cervico-vaginal microbiome represents a source of potential biomarkers, with specific taxa showing consistent associations with cervical oncogenesis and HPV persistence. Notably, a decreased abundance of the protective L. crispatus, an increased abundance of the more transient L. iners, and the enrichment of anaerobe species such as Gardnerella or Prevotella are consistently associated with a higher risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [191,192,193].

The profound implications of these findings for future diagnostics underscore the importance of continued research to move these promising markers from association to clinical application.

3.3.4. Viral Load Quantification (HPV DNA Load)—The Seegene Anyplex System and Roche Cobas

The correlation between HPV viral load and cervical lesion severity remains insufficiently understood, and the clinical significance of viral load in both detection and treatment continues to be debated. Considerable controversy persists over the utility of viral load as a biomarker for assessing and diagnosing cervical disease. Current methodologies for quantifying HPV viral load include quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), Hybrid capture 2 (HC2), and in situ hybridization (ISH). However, heterogeneity in reporting metrics poses challenges for cross-study comparison: qPCR results are often expressed as copies per cell, per volume, or per host genome, whereas HC2 typically reports values as relative light units per cutoff (RLU/CO). In some cases, integrated optical density has also been employed. Importantly, there is no consensus regarding a standardized cutoff threshold to define “low”, “medium”, or “high” viral loads [194,195,196,197,198,199,200].

A systematic review by Fobian et al. (2024) [194] demonstrated that elevated HPV viral load is generally associated with increased disease severity and poorer clinical outcomes. Current evidence is most consistent for overall HPV viral load and HPV 16-specific viral load, with both showing a positive correlation with lesion grade. In efforts to improve the diagnostic accuracy of second-line cervical screening, there is growing interest in integrating viral load quantification with other molecular markers, such as co-infection status. HPV viral load assessment may also provide insight into infection persistence, as higher viral loads are more frequently associated with chronic infections that are more likely to progress. Longitudinal studies further suggest that dynamic changes in viral load correlated significantly with the risk of developing CIN 2+ lesions, particularly when considered in relation to specific genotypes [194,195,196].

The implications of the HPV genotype are critical, as viral load patterns differ across subtypes. For example, viral loads of genotypes related to HPV 16, comprising 52 and 58, tend to increase with disease progression, whereas viral loads of subtypes 45 and 59, related to HPV 18, show relatively stable patterns. Viral integration into the host genome further complicates interpretation, as integrated viral DNA may drive oncogenic transformation even when measurable viral load appears low, potentially leading to an underestimation of disease severity and delayed clinical intervention. Moreover, age-related differences have been reported: the correlation between viral load and lesion grade is stronger in women over 30 years old compared with younger women. The impact of multiple HPV infections and co-infection remains controversial. Some studies suggest that co-infection may potentiate the risk of progression to high-grade lesions, whereas others report no significant difference in cervical cancer risk between women with single versus multiple infections. Collectively, these findings indicate that high-risk HPV viral load influences cervical disease development to varying extents, depending on genotype, infection dynamics, and host factors [195,196,199].

Efforts have been made to establish clinically relevant cutoff values for viral load. Liu et al. proposed that colposcopy should be performed when a patient has a viral load exceeding 10 RLU/CO, while Pap smear cytology should be prioritized for intermediate values (>1 to <10 RLU/CO) to optimize sensitivity, specificity, and referral rates [195,200,201]. Similarly, Lorincz et al. classified hrHPV DNA viral load into three categories: low (1–99.99 RLU/CO), moderate (100–999 RLU/CO), and high (>1000 RLU/CO). Despite variability, most studies employing HC2 have adopted similar groupings, defining a “low” viral load as 1–10 RLU/CO, “medium” as 11–100 RLU/CO, and “high” as 101–1000 RLU/CO [195,197,200].

3.3.5. Minichromosome Maintenance Protein 2 (MCM2) and DNA Topoisomerase II Alpha (TOP2A) (ProExC) and HPV E4

Recent research has shown that MCM2 and TOP2A are upregulated in cells exhibiting aberrant S-phase activity, including those transformed by HPV. Their expression is strongly correlated with increased levels of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 [202,203,204,205,206]. MCM proteins (consisting of MCM2, MCM5, MCM6, and MCM7) are highly conserved DNA-binding factors essential for replication licensing. MCM2 is expressed only in the normal basal proliferating cervical epithelium, and its dysregulation disrupts DNA replication processes [44,206,207].

The ProExCTTM (BD Diagnostics-Tripath, Burlington, NC, USA) assay utilizes a monoclonal antibody combination targeting both MCM2 and TOP2A to detect abnormal proliferative activity [203,205,206]. This nuclear staining technique highlights dysplastic cells; however, false-positive results may occur in certain contexts, including normal basal and parabasal cells in atrophic epithelium, or in metaplastic glandular and tubal epithelium [203]. Compared with p16 immunostaining, ProExCTM demonstrates greater sensitivity for identifying women with LSIL. Nevertheless, its specificity for accurately distinguishing LSIL is comparatively lower [63,202,204,207].

3.3.6. ncRNA Species

While infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) is a necessary precondition for cervical cancer, it alone is insufficient to drive carcinogenesis. The progression to malignancy is critically influenced by host factors, including individual genetic variations and epigenetic modifications. Epigenetic mechanisms—such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and the action of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are functionally versatile RNA molecules that regulate gene expression without being translated into proteins. In the context of cervical cancer, research has primarily focused on three key categories: long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and circular RNAs (circRNAs).

Among these, ncRNAs, which are abundant in the genome, are categorized by size into small ncRNAs and lncRNAs exceeding 200 nucleotides [208]. LncRNAs are further classified based on their genomic context relative to protein-coding genes and function through both cis- and trans-regulatory mechanisms. Advances in high-throughput sequencing have unveiled the critical roles of ncRNAs in diverse biological processes, including development, proliferation, and DNA damage repair [209,210]. Consequently, the dysregulation of lncRNAs has been strongly linked to the pathogenesis of various cancers and other diseases, highlighting their immense potential as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets [211].

Oncogenic lncRNAs in Cervical Cancer

Numerous lncRNAs function as oncogenes in cervical cancer, driving tumor progression through diverse mechanisms (Table 3). Key players include H19, which promotes proliferation by sponging miR-143-3p to upregulate SIRT1, and MALAT1, which facilitates invasion by epigenetically silencing miR-124 and thereby disinhibiting GRB2 [212,213]. HOTAIR enhances metastasis by co-activating SRF, activating STAT3-mediated transcription, and sponging miR-148a to upregulate HLA-G [214]. CCAT1 stimulates proliferation and invasion by sponging miR-181a-5p and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling, while XIST stabilizes the Fus oncoprotein by sequestering miR-200a [215,216]. Additionally, SNHG family members (SNHG14, SNHG12, SNHG16, and SNHG20) contribute to oncogenesis by regulating distinct pathways including the miR-206/YWHAZ, miR-125b/STAT3, miR-216-5p/ZEB1, and miR-140-5p/ADAM10-MEK/ERK axes [217].

Table 3.

lncRNA molecular function and regulatory pathway.

Tumor-Suppressive lncRNAs in Cervical Cancer

In contrast to oncogenic lncRNAs, only a limited number function as tumor suppressors in cervical cancer. MEG3 induces apoptosis by binding to phospho-STAT3 and promoting its ubiquitination, while GAS5 is frequently silenced epigenetically and functions by sponging miR-196a and miR-205 to upregulate FOXO1 and PTEN [218,219]. Similarly, STXBP5-AS1 and TUSC8 also inhibit proliferation and invasion by targeting PTEN [220,221].

The lncRNA XLOC_010588 is a significant prognostic marker, negatively correlating with FIGO stage and serving as an independent predictor of overall and progression-free survival. It suppresses tumor growth by directly interacting with c-Myc and reducing its expression [222].

Diagnostic Potential of lncRNAs in Cervical Cancer

With rising incidence in younger populations and poor overall survival for advanced/recurrent disease, there is a pressing need for more specific and sensitive biomarkers. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) represent promising non-invasive diagnostic tools for cervical cancer. Notably, serum levels of lncRNA GIHCG are significantly elevated in cervical cancer patients. ROC curve analysis demonstrates its strong diagnostic capability, with 88.75% sensitivity and 87.50% specificity in distinguishing patients from healthy controls [223]. Similarly, PVT1 shows markedly higher serum expression in cervical cancer groups compared to healthy individuals, indicating its utility as both a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker [224]. Despite these promising findings, several challenges must be addressed before clinical implementation. Further research is essential to identify lncRNAs with optimal specificity and sensitivity for cervical cancer diagnosis.

LncRNAs as Prognostic Biomarkers in Cervical Cancer

Numerous long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) demonstrate significant prognostic value in cervical cancer, with their expression levels or methylation status strongly correlating with clinical outcomes. The aberrant expression of lncRNAs such as LINC00511, CERNA2, GHET1, and SOX21-AS1 has been consistently associated with advanced disease stage, lymph node metastasis, and poorer overall survival [225,226,227,228]. Furthermore, the methylation status of specific lncRNAs, including MEG3, serves as a valuable prognostic indicator, with elevated methylation levels predicting aggressive tumor behavior and disease progression [229]. Additional lncRNAs, such as AC126474 and C5orf66-AS1, show promise in predicting metastatic potential [230]. The stability and detectability of these molecules in clinical samples underscore their potential utility as non-invasive prognostic tools for cervical cancer management.

miRNAs as Diagnostic and Prognostic Tools in Cervical Cancer

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as promising biomarkers for cervical cancer (CC) diagnosis and prognosis due to their stable presence in bodily fluids (cervical swabs, serum, plasma, and urine) and distinct expression patterns in cancerous versus healthy tissues. Their dysregulation reflects key aspects of disease progression, offering clinical potential for non-invasive detection and risk stratification [231].

The discovery that circulating miRNAs are protected within exosomes and vesicles has established their potential as stable, non-invasive biomarkers for cervical cancer. Diagnostic panels can leverage both the increased expression of specific miRNAs—such as miR-21, miR-27a, miR-34a, and miR-196a, which are highly expressed in cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—and the aberrant hypermethylation of others. For instance, the hypermethylation of miR-124, detectable via methylation-specific PCR (MSP), serves as a diagnostic indicator [232,233]. Furthermore, hypermethylation of miR-203 and miR-375 is associated with HPV-positive high-grade dysplasia, making them potential indicators of pre-cancerous lesions [234]. Analyzing a combination of miRNA expression and methylation patterns provides a powerful approach for diagnosing cervical cancer across its various stages.

Cervical swabs are a promising biosource for prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers in cervical cancer (CC), particularly given the presence of differentially expressed microRNAs (miRNAs). Investigations into these fluid-derived miRNAs reveal distinct expression patterns associated with disease progression. For instance, miR-432 shows significant downregulation in cervical mucus from CINII/III lesions compared to normal samples [235]. Conversely, a panel of miRNAs—including miR-26b-5p, miR-142-3p, miR-143-3p, miR-191-5p, miR-223-3p, and miR-338-3p—demonstrates marked upregulation in CIN3, highlighting their potential as sensitive indicators of pre-malignant transformation [236].

Analysis of microarray data has revealed significant miRNA dysregulation in the serum of cervical cancer (CC) patients. Notably, the upregulation of miR-483-5p, miR-1246, miR-1275, and miR-1290 was initially identified through array screening and subsequently validated by qPCR [237]. This finding is reinforced by independent confirmations of elevated serum levels for several other miRNAs in CC patients compared to healthy controls, including miR-150, miR-221, miR-15b, and the well-characterized miR-21. These consistently deregulated circulating miRNAs represent promising candidates for non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers [238,239,240,241].

A defined panel of six urinary miRNAs—comprising miR-21-5p, miR-155-5p, miR-199a-5p, miR-145-5p, miR-218-5p, and miR-34a-5p—has been identified as a promising diagnostic and prognostic tool for cervical pre-cancer and cancer. This signature, which includes molecules with recognized oncogenic and tumor-suppressive functions, demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing disease states. However, further validation through large-scale prospective studies comparing this miRNA panel against conventional cytology and HPV testing is essential before urinary miRNA analysis can be established as a reliable, non-invasive biomarker for cervical cancer screening [242].

Beyond their diagnostic utility, miRNAs demonstrate significant prognostic value in cervical cancer (CC), exhibiting strong correlations with critical clinical parameters including tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and overall survival. Elevated expression of oncogenic miRNAs, such as miR-224 and miR-182, is associated with advanced disease and unfavorable outcomes, while reduced levels of tumor-suppressive miRNAs, including miR-150, miR-200b, miR-636, miR-205, and miR-187, correlate with aggressive tumor behavior and diminished survival rates [243]. These associations position miRNA expression profiles as reliable prognostic indicators that can inform clinical decision-making.

The therapeutic potential of miRNAs is supported by pre-clinical evidence demonstrating that modulating miRNA expression—through approaches such as miRNA mimics—can suppress tumor growth, inhibit metastasis, and enhance chemosensitivity in CC models [244]. Bioinformatic and clinical studies further highlight specific miRNAs with dual diagnostic and prognostic significance. For instance, miR-21 functions as a sensitive diagnostic marker and an oncogenic driver, with upregulation predicting poorer prognosis [245]. Similarly, downregulation of miR-885-5p has been linked to disease progression, suggesting its utility as an independent prognostic predictor and therapeutic target [246].

The HPV E4 protein, expressed as an E1-E4 fusion, is predominantly detected in differentiated epithelial cells during the late stage of the viral replication cycle, where it undergoes phosphorylation and cleavage to regulate keratin binding, multimerization, and cytoskeletal disruption. These activities suggest that E4 plays a critical role in viral release and cell cycle regulation, particularly through G2 arrest, thereby facilitating viral propagation while modulating host cellular processes. The PapilloCheck® test and other molecular assays targeting E6 and E7 HPV proteins’ DNA or mRNA offer valuable diagnostic insights, but are limited by high costs and the risk of false-positive results, particularly in transient infections. The assays seem to have the potential to improve screening accuracy and reduce reliance on repeated cytology and invasive procedures [247,248].

3.3.7. Cyclins as Cell Proliferation Biomarkers

Cyclins are key regulators of the cell cycle, controlling transitions between phases by activating cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) [249]. The deregulation of cyclin expression, especially cyclin D1, cyclin E, and cyclin A, has been frequently observed in cervical cancer and high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2/3) [250] and contributes to uncontrolled cell proliferation.

It was shown that cyclin E and cyclin A overexpression can distinguish high-grade lesions (CIN2+) from low-grade or normal cervical epithelium [251]. Cyclin A and cyclin E overexpression may predict increased recurrence risk after surgical or chemoradiation therapy [252]. High cyclin D1 expression has been correlated with advanced tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and poorer overall survival in cervical cancer patients. Cyclin expression can also assist in triaging HPV-positive women by identifying those with active cell cycle dysregulation indicative of imminent progression.

The combined assessment of cyclins (e.g., cyclin E and cyclin A) may improve diagnostic accuracy for high-grade lesions. Some studies suggest that cyclin expression profiles, when combined with other molecular markers such as Ki-67 or p16INK4a, provide a stronger prognostic signature than single markers alone [251].

3.3.8. Novel, Promising Biomarkers

E2/E6 Ratio

Analysis of the E2/E6 ratio can serve as an indicator of viral integration, distinguishing high-grade from low-grade lesions, though its limited accuracy in advanced disease suggests it is best applied alongside complementary biomarkers such as HPV L1 protein expression [55], with Choi et al.’s 2018 study revealing the association between a decrease in E2/E6 ratio and the lack of HPV L1 expression with CIN2+ lesions [253].

LINE-1 ORF1p as Novel Potential Biomarker

ORF1p shows strong potential as a novel biomarker for cervical cancer screening, as it accurately distinguishes dysplastic epithelium from normal cervical epithelium. Its expression was absent or weak in the majority of normal specimens (79.2%), as revealed by Karkas et al. in their 2024 research, and progressively increased with CIN grade, being detectable in 87.5% of CIN1 cases, 63% in CIN 2 cases, 92.8% of CIN 3 cases, and 93.8% of invasive cancers. Its statistically significant capability of differentiating normal tissue from CIN 1 lesions highlights its diagnostic value at the earliest stage in cervical carcinogenesis, complementing or more likely surpassing other markers such as dual staining 9p16/ki-67) [254]. These findings, although in need of further validation, underscore ORF1p as a promising tool for cervical cancer screening algorithms.

Circulating HPV DNA—circHPV-DNA

circHPV-DNA, particularly HPV-16, shows a modest but significant association with cervical cancer, although the performance of HPV-18 DNA is weaker. MicroRNAs such as miR-20a, miR-205, and miR-1246 have been linked to cervical cancer, but their expression profiles are inconsistent across studies. Among blood-based biomarkers, HPV-16 E antibodies and circulating HPV DNA exhibit the strongest association with HPV-related cancers, whereas other markers, such as folate, IGF-1, IGFBP-3, and IFN-γ, lack specificity. Epigenetic alterations, especially DNA methylation of host genes such as CADM1, MAL, and FAM19A4, show high diagnostic accuracy for CIN3 and cervical cancer, with assays like GynTect® demonstrating greater specificity than cytology or HPV genotyping. Furthermore, transcriptomic biomarkers, such as AGK protein and mRNA, are significantly upregulated in cervical cancer, suggesting additional potential for prognostic and screening applications [42,55,255,256,257].

3.3.9. AI and Cervical Cancer Screening

The literature reflects the need for structuring all these new markers for cervical HPV-induced lesions to obtain the best possible sensitivity and specificity. Evidence suggests that this will be facilitated by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI). By integrating AI into cervical cancer screening, as many studies now describe, we will achieve substantial improvements in diagnostic accuracy. Machine learning models have already been tested, and the results have been very promising. The models already tested incorporate hrHPV genotyping, cytology, and gynecological examination. Compared with classical triage methods, AI testing software shows a distinct improvement in predictive performance for detecting CIN2+ lesions [258].

The growing availability of large, high-quality datasets of cervical clinical data has created a strong foundation for training and validating AI-based models. Several datasets are public, well-curated, and accessible (e.g., the Cx22 dataset [259], the ISBI Challenge Database for cytology image segmentation [260,261], the SIPaKMeD dataset [262], and the Harlev datasets [263]) for cytology cell classification based on morphology. In contrast, colposcopy image datasets available remain limited. The Intel & MobileODT Cervical Cancer Screening dataset [264] represents the largest open-access resource, although it is derived from mobile-level colposcopy devices. High-magnification colposcopy datasets remain largely unavailable to the public. The IARC Cervical Cancer Image Bank ARC—International Agency for Research on Cancer [265] is a notable database collected by collaborating specialists using standardized formats, but its scale is relatively modest.

AI in Cervical Cytology