Comparison of Transvaginal and Transperineal Ultrasonographic Uterocervical Angle Measurements in Low-Risk Pregnancies at 24–34 Weeks’ Gestation

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

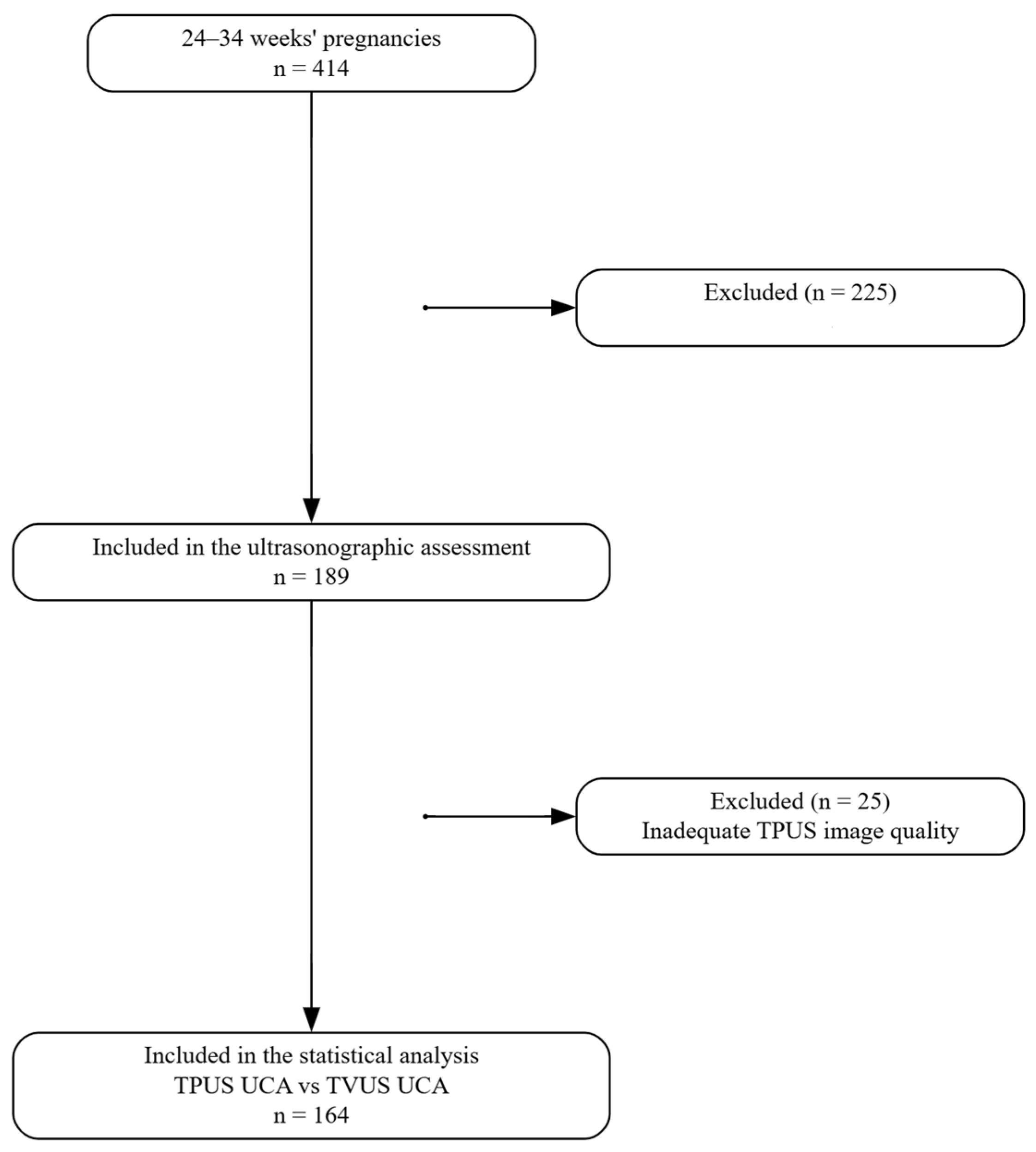

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

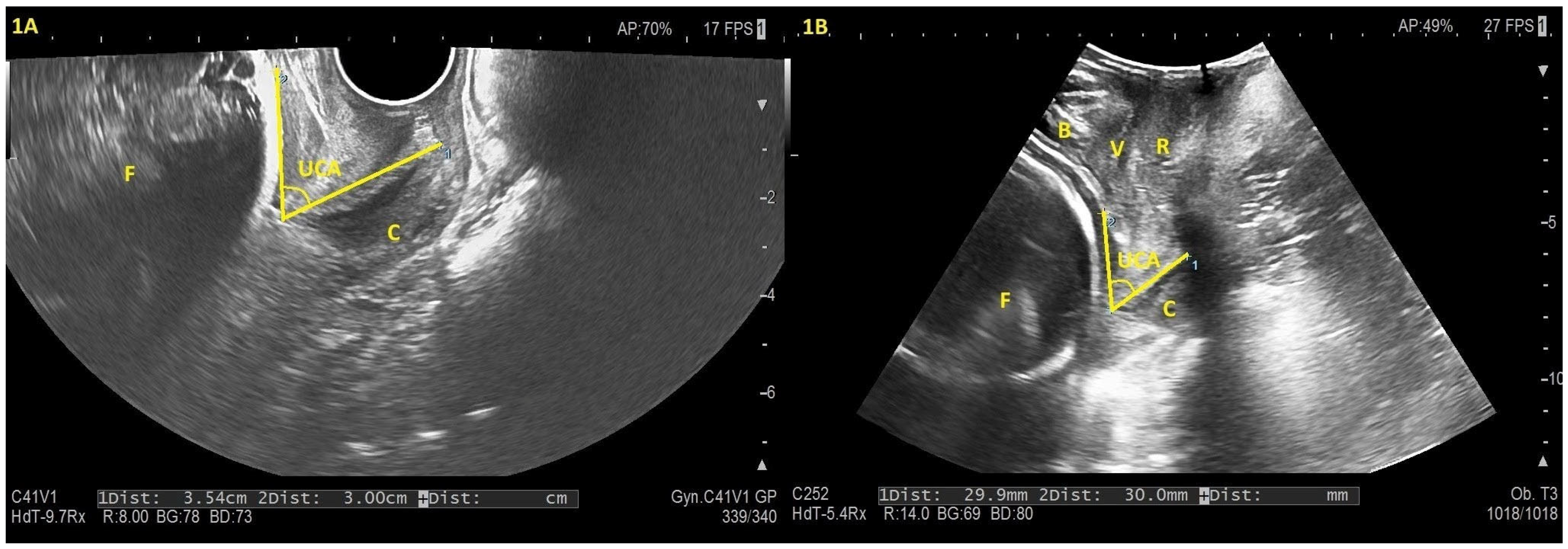

2.3. Data Sources/Measurement

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

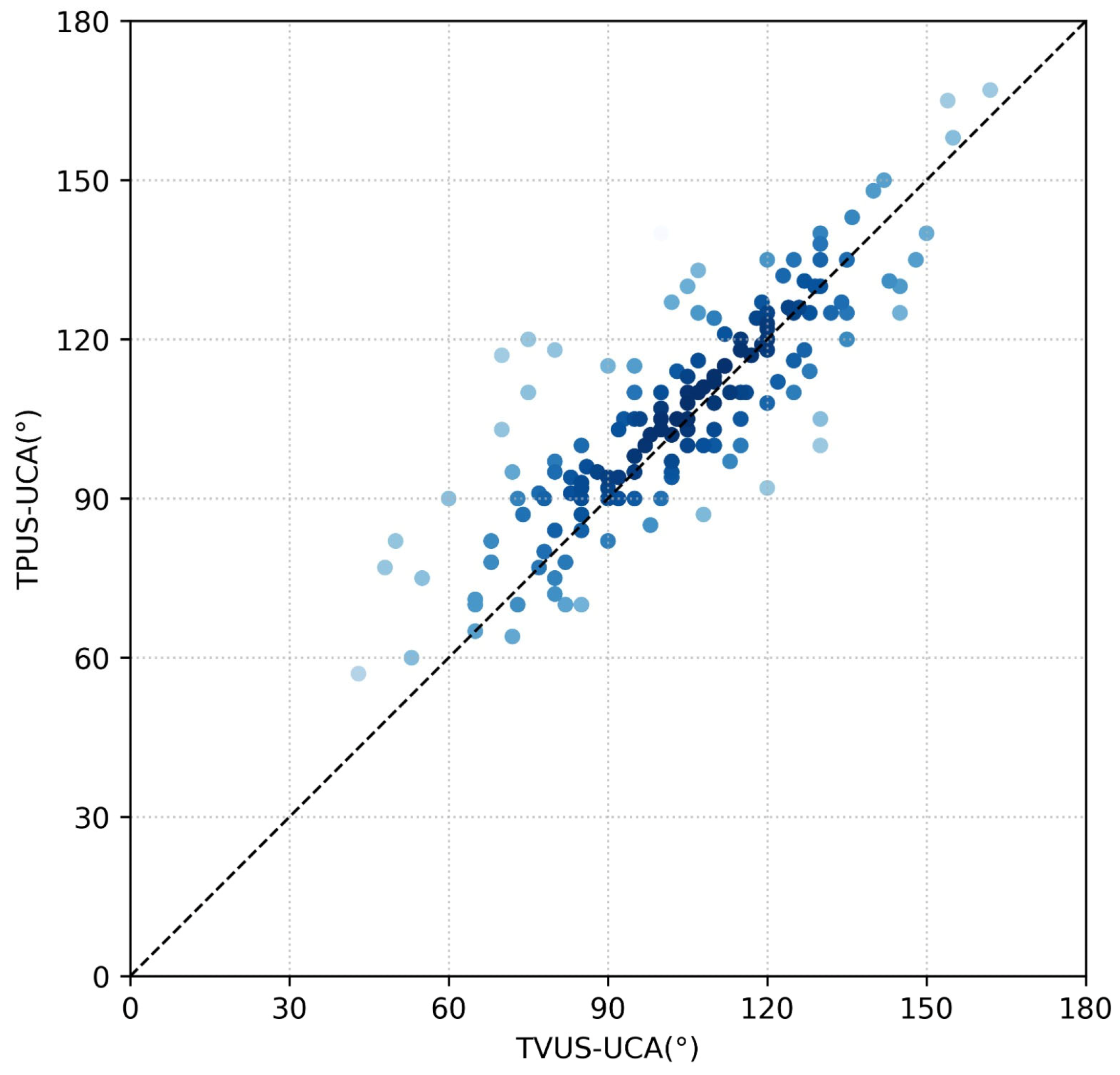

3.2. Outcome Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Principle Findings

4.2. Interpretation

4.3. Strengths and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | American College of Radiology |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CCC | Concordance correlation coefficient |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CL | Cervical length |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| ISUOG | International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology |

| LEEP | Loop electrosurgical excision procedure |

| TAUS | Transabdominal ultrasound |

| TPUS | Transperineal ultrasound |

| TVUS | Transvaginal ultrasound |

| UCA | Uterocervical angle |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. In WHO Recommendations on Interventions to Improve Preterm Birth Outcomes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Preterm Labour and Birth; NICE Guideline 25; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Di Tommaso, M.; Seravalli, V.; Vellucci, F.; Cozzolino, M.; Spitaleri, M.; Susini, T. Relationship between cervical dilation and time to delivery in women with preterm labor. J. Res. Med. Sci. Off. J. Isfahan Univ. Med. Sci. 2015, 20, 925–929. [Google Scholar]

- Van Baaren, G.J.; Vis, J.Y.; Wilms, F.F.; Oudijk, M.A.; Kwee, A.; Porath, M.M.; Oei, G.; Scheepers, H.C.J.; Spaanderman, M.E.A.; Bloemenkamp, K.W.M.; et al. Predictive value of cervical length measurement and fibronectin testing in threatened preterm labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ness, A.; Visintine, J.; Ricci, E.; Berghella, V. Does knowledge of cervical length and fetal fibronectin affect management of women with threatened preterm labor? A randomized trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 197, 426.e1–426.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, J.; Feltovich, H.; Berghella, V.; Manuck, T. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, B2–B7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahedi, M.; Goharian, M.; Rasti, S.; Zarean, E.; Tarrahi, M.; Shahshahan, Z. The uterocervical angle-cervical length ratio: A promising predictor of preterm birth? Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 165, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercan, C.; Dagdeviren, E.; Yeniocak, A.S.; Can, S. The role of uterine anteversion and flexion angles in predicting pain severity during diagnostic hysteroscopy: A prospective cohort study. Ginekol. Pol. 2025, 96, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlodawski, J.; Mlodawska, M.; Plusajska, J.; Detka, K.; Bialek, K.; Swiercz, G. Repeatability and Reproducibility of Potential Ultrasonographic Bishop Score Parameters. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güner, G.; Barut, A.; Okcu, N.T. Transperineal sonographic assessment of the angle of progression before the onset of labour: How well does it predict the mode of delivery in late-term pregnancy. J. Perinat. Med. 2024, 52, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Hwang, H.S.; Kim, H.S.; Sohn, I.S.; Kwon, H.S. The Uterocervical Angle Combined with Bishop Score as a Predictor for Successful Induction of Labor in Term Vaginal Delivery. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.T.; Vu, V.T.; Nguyen, V.Q.H. Distribution of uterocervical angles of pregnant women at 16(+0) to 23(+6) weeks gestation with low risk for preterm birth: First vietnamese cohort of women with singleton pregnancies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziadosz, M.; Bennett, T.A.; Dolin, C.; West Honart, A.; Pham, A.; Lee, S.S.; Pivo, S.; Roman, A.S. Uterocervical angle: A novel ultrasound screening tool to predict spontaneous preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 376.e1–376.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, N.; Kiyak, H.; Bolluk, G.; Bafali, O.; Ince, O.; Gedikbasi, A. Assessment of utero-cervical angle and cervical length as predictors for threatened preterm delivery in singleton pregnancies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2024, 50, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakub, M.; Marta, M.; Jagoda, G.; Kamila, G.; Stanislaw, G. Is Unfavourable Cervix Prior to Labor Induction Risk for Adverse Obstetrical Outcome in Time of Universal Ripening Agents Usage? Single Center Retrospective Observational Study. J. Pregnancy 2020, 2020, 4985693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.M.; Srinivas, S.K.; Parry, S.; Elovitz, M.A.; Wang, E.; Schwartz, N. Can transabdominal ultrasound be used as a screening test for short cervical length? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 208, 190.e1–190.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.; Butt, K.; Crane, J.M. No. 257-Ultrasonographic Cervical Length Assessment in Predicting Preterm Birth in Singleton Pregnancies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. JOGC 2018, 40, e151–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, E.; Maturen, K.; Feldstein, V.; Poder, L.; Shipp, T.; Strachowski, L.; Sussman, B.; Weber, T.; Winter, T.; Glanc, P. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Assessment of Gravid Cervix. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2020, 17, S26–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, T.; Marin, B.; Garuchet-Bigot, A.; Kanoun, D.; Catalan, C.; Caly, H.; Eyraud, J.L.; Aubard, Y. Transperineal versus transvaginal ultrasound cervical length measurement and preterm labor. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 290, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridis, I.; Dagklis, T.; Mamopoulos, A.; Gerede, A.; Athanasiadis, A. Cervical length at 31–34 weeks of gestation: Transvaginal vs. transperineal ultrasonographic approach. J. Perinat. Med. 2019, 47, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdeviren, E.; Tercan, C.; Yeniocak, A.S.; Cigdem, B.; Ataseven, E.; Varlik, A.; Kilic, M.F.; Kaya, Y. Comparative Assessment of Uterocervical Angle Using Transvaginal, Transabdominal, and Transperineal Ultrasonography Between 16 and 24 Weeks of Gestation. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, C.M.; Sotiriadis, A.; Odibo, A.; Khalil, A.; D’Antonio, F.; Feltovich, H.; Salomon, L.J.; Sheehan, P.; Napolitano, R.; Berghella, V.; et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: Role of ultrasound in the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 60, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.O.; Sonek, J. How to measure cervical length. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 45, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retzke, J.D.; Sonek, J.D.; Lehmann, J.; Yazdi, B.; Kagan, K.O. Comparison of three methods of cervical measurement in the first trimester: Single-line, two-line, and tracing. Prenat. Diagn. 2013, 33, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seracchioli, R.; Raimondo, D.; Del Forno, S.; Leonardi, D.; De Meis, L.; Martelli, V.; Arena, A.; Paradisi, R.; Mabrouk, M. Transvaginal and transperineal ultrasound follow-up after laparoscopic correction of uterine retrodisplacement in women with posterior deep infiltrating endometriosis. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 59, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, H.P. Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor. Part I: Two-dimensional aspects. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 23, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaka, M.M. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. J. Med. Assoc. Malawi 2012, 24, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, G.B. A Proposal for Strength-of-Agreement Criteria for Lin’s Concordance Correlation Coefficient; NIWA Client Report HAM2005-062; NIWA: Hamilton, New Zealand, 2005; Volume 45, pp. 307–310. [Google Scholar]

- Gerke, O. Nonparametric Limits of Agreement in Method Comparison Studies: A Simulation Study on Extreme Quantile Estimation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkanha, L.; Sudjai, D.; Puttanavijarn, L. Correlation of transabdominal and transvaginal sonography for the assessment of uterocervical angle at 16–24 weeks’ gestation. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. J. Inst. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimassi, K.; Hammami, A.; Bennani, S.; Halouani, A.; Triki, A.; Gara, M.F. Use of transperineal sonography during preterm labor. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. J. Inst. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 36, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Data | n = 164 |

|---|---|

| Maternal age b (year) | 27 (18–40) |

| BMI a (kg/m2) | 28.91 ± 5.08 |

| Gestational age b (days) | 208 (168–238) |

| Nulliparity c | 83 (50.60) |

| Previous cesarean section c n (%) | 36 (21.95) |

| Primigravidas c n (%) | 68 (41.46) |

| Turkish ethnicity c n (%) | 144 (87.80) |

| TVUS | TPUS | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CL a (mm) | 33.03 ± 5.51 | 31.78 ± 5.07 | <0.001 |

| UCA a (°) | 103.85 ± 23.32 | 107.16 ± 20.71 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dagdeviren, E.; Kaya, Y. Comparison of Transvaginal and Transperineal Ultrasonographic Uterocervical Angle Measurements in Low-Risk Pregnancies at 24–34 Weeks’ Gestation. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243232

Dagdeviren E, Kaya Y. Comparison of Transvaginal and Transperineal Ultrasonographic Uterocervical Angle Measurements in Low-Risk Pregnancies at 24–34 Weeks’ Gestation. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243232

Chicago/Turabian StyleDagdeviren, Emrah, and Yucel Kaya. 2025. "Comparison of Transvaginal and Transperineal Ultrasonographic Uterocervical Angle Measurements in Low-Risk Pregnancies at 24–34 Weeks’ Gestation" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243232

APA StyleDagdeviren, E., & Kaya, Y. (2025). Comparison of Transvaginal and Transperineal Ultrasonographic Uterocervical Angle Measurements in Low-Risk Pregnancies at 24–34 Weeks’ Gestation. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243232